Abstract

Real-time in situ monitoring of plant physiology is essential for establishing a phenotyping platform for precision agriculture. A key enabler for this monitoring is a device that can be noninvasively attached to plants and transduce their physiological status into digital data. Here, we report an all-organic transparent plant e-skin by micropatterning poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) polystyrene sulfonate (PEDOT:PSS) on polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) substrate. This plant e-skin is optically and mechanically invisible to plants with no observable adverse effects to plant health. We demonstrate the capabilities of our plant e-skins as strain and temperature sensors, with the application to Brassica rapa leaves for collecting corresponding parameters under normal and abiotic stress conditions. Strains imposed on the leaf surface during growth as well as diurnal fluctuation of surface temperature were captured. We further present a digital-twin interface to visualize real-time plant surface environment, providing an intuitive and vivid platform for plant phenotyping.

Optically and mechanically invisible all-organic plant e-skin enables noninvasive monitoring of plant physiological signals.

INTRODUCTION

Crop production remains a salient global issue with 828 million people worldwide experiencing hunger (1, 2). Advanced high-throughput phenotyping techniques have revolutionized breeding efforts by swiftly collecting comprehensive phenotypic data from plant populations (3, 4). It allows for more effective and informed plant breeding decisions, thereby facilitating the rapid development of improved plant varieties (5–7). Existing methods for capturing phenotypic traits predominantly rely on imaging technologies (8), robotics (9), and drones (10). However, these approaches have substantial limitations in terms of providing customized, continuous, and high spatiotemporal resolution monitoring (11). In addition, the currently used devices that are mounted on plants are often rigid, heavy, and opaque, exhibiting mechanical and optical mismatch with plants (12–14). This discordance can lead to inaccuracies in measurement and potential harm to plants. Therefore, nondestructive, continuous, and long-term acquisition of phenotypic data are urgently needed for monitoring multiple traits for crop breeding.

The recent efforts toward plant sensor development have aimed to meet this need and to address the mechanical mismatch issues. Advances in human wearable electronics (15–23) have prompted botanical applications (24, 25), enabling the monitoring of plant conditions through the capture of physical signals like growth, surface temperature, and humidity (26–30), chemical signals like volatile organic compounds and hormones (31, 32), as well as biopotential signals (33–35). The mechanical adhesion is achieved progressively, from using an adhesive tape on leaves (36), conformal wrapping of flexible sensors around stems (37), direct inkjet writing/printing (38, 39), and vapor polymer printing (40, 41) on leaves, to the recent employment of epidermal electronics that can be seamlessly and directly attached to leaves (42, 43). Despite these advancements, the existing plant epidermal electronics still present limitations in effective monitoring of dynamic plant growth over time due to limited stretchability and softness. Furthermore, an aspect that has often been overlooked is the consideration of optical transparency, which is a critical factor for developing sensors for plants with photosynthetic activities. Organic materials that can be made flexible and transparent are promising candidates for developing plant sensors. Meanwhile, organic materials also stand out for their low-cost, biodegradability, and biocompatibility, which are essential for not only plants but also sustainable world. The commercially available poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) polystyrene sulfonate (PEDOT:PSS) is one intrinsically flexible and transparent organic material, thus can serve the flexibility and optical transparency purpose with their good electrical conductance. However, it has been challenging to develop all-organic epidermal sensors due to the difficulties in micropatterning the flexible, conductive organic material on another thin soft polymer substrate (44–47).

Here, we report an all-organic plant epidermal sensor, namely, plant e-skin, that is both mechanically and optically invisible for non-invasive plant physiology monitoring. The plant e-skin is realized by developing a scalable microfabrication process to enable the micropatterning of transparent PEDOT:PSS on a stretchable, transparent polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) substrate (Fig. 1A). The successful development of this process marks a minimum feature size of 2-μm PEDOT:PSS pattern on a stretchable elastomer, paving the way for the development of high-density transparent epidermal sensors, displays, and other functional devices. With the transparent, ultrathin, and stretchable nature, the plant e-skin can be configured into strain and temperature sensors with tailored micropatterns, allowing continuous and real-time monitoring of plant growth and surface temperature when attached to leaf epidermis. Experimental tests of the strain sensors attached on the juvenile leaves of live Brassica rapa revealed distinct diurnal growth patterns with minimal growth during the day and predominant growth at night, as well as varying growth rates under different abiotic stress conditions. Application of the temperature sensor also captured surface temperature dynamics of the corresponding conditions, which would facilitate the timely intervention of heat stress. Toward broader practical impact, a virtual digital-twin plant is developed, allowing real-time visualization and analysis of leaf surface temperature (Fig. 1B). We envision that construction of the virtual digital-twin plant interface, aided by the plant e-skin, paves the way for efficient monitoring of plants and expedited decision-making in crop breeding as well as precision farming.

Fig. 1. Fabrication and characteristics of the plant e-skin.

(A) Schematic illustration of the fabrication process to develop the plant e-skin with PEDOT:PSS micropatterns on the PDMS substrate. (B) Conceptual drawing showcasing projecting the plants in real space to the digital-twin counterpart in virtual space based on the sensory information generated by the plant e-skin. (C) Optical images of the feature size of the PEDOT:PSS patterns on the PDMS substrate. (D) Optical image of a PEDOT:PSS-based lion pattern on the PDMS substrate. Scale bar, 100 μm. (E) Optical image of PEDOT:PSS-based character patterns on the PDMS substrate. Scale bar, 50 μm. (F) Transmission spectrum of the PEDOT:PSS patterns on the PDMS film. (G) Photographs of the plant e-skin attached on leaves with varying surface roughness. (H) Photograph of the plant e-skin attached on leaves through different wilting stages. (I) A comparison diagram of the developed plant e-skin with the reported plant sensors from five aspects, including transparent, epidermal, stretchable, micropatterned, and biocompatible characteristics.

RESULTS

Fabrication and characteristics of the plant e-skin

To monitor plant physiological status in a noninvasive manner, biocompatibility, transparency, stretchability, and conformability are desired simultaneously. A scalable microfabrication process is developed to manufacture all-organic plant e-skins that meets all these requirements based on simple lithography and lift-off process (Fig. 1A). Detailed fabrication process can be found in fig. S1 and Materials and Methods. Table S1 is provided to illustrate the scalability of PEDOT:PSS-based transparent e-skin in previous literatures. The all-organic plant e-skin is essentially a micropatterned PEDOT:PSS conductive component on one PDMS layer and encapsulated by another layer of PDMS. PEDOT:PSS was chosen as the conductive component because of its exceptional transparency and conductivity. Its biocompatibility further extends its applications to biomedical engineering field. Specifically in relation to plants, the transparency and biocompatibility of PEDOT:PSS align well with the requirements of developing plant e-skins that can be attached to the plants without any observable adverse effects to plant health. While achieving a well-defined pattern of PEDOT:PSS on the stretchable elastomeric substrate poses a considerable technological challenge, we have succeeded to demonstrate the ability to create PEDOT:PSS patterns on PDMS substrate with the feature sizes ranging from 100 μm all the way down to 2 μm, as illustrated in Fig. 1C. Besides, the versatility of the proposed fabrication process is demonstrated by creating intricate patterns of PEDOT:PSS, such as the university logo with a lion (Fig. 1D) and alphabets (Fig. 1E), despite their complicated structures and varying resolutions. Figure 1F demonstrates the remarkable transparency of the as-fabricated e-skin, exhibiting transmittance exceeding 85% within the wavelength range of 400 to 700 nm, which aligns perfectly with that required for plant photosynthesis. The inserted image exemplifies the plant e-skin’s outstanding transparency, allowing for a clear view of the outside scene when affixed to a clean glass. The plant e-skin has a thickness of only 4.5 μm (fig. S5), consisting of a layer of PEDOT:PSS sandwiched between the PDMS substrate and encapsulation layer where the thickness of PEDOT:PSS thin film is 120 nm (fig. S6A). The dependence of transparency and conductivity on different PEDOT:PSS thickness are presented in fig. S6 (B and C, respectively). Owing to the high transparency together with the ultrathin thickness, our plant e-skin offers a superior advantage by enabling seamless attachment to a wide range of plant leaves. As shown in fig. S7, we successfully attached the plant e-skin to a B. rapa leaf. The midrib and vein of this leaf remain clearly visible through the attached sensor, affirming its excellent transparency and conformability. Moreover, the plant e-skin can be applied to different kinds of leaves with varying surface roughness, including (i) sweet potato, (ii) Zamioculcas zamiifolia, (iii) Peperomia argyreia, and (iv) Coleus scutellarioides (Fig. 1G). The plant e-skins demonstrate durability, where secure attachment is maintained even when the leaves undergo wilting (Fig. 1H and fig. S8). The shear adhesion forces between our e-skin and leaves are characterized in fig. S9, which all exceed 0.2 N with varying leaves, or under various scenarios including wilting, fast water flow, and immersion in water. A detailed discussion on adhesion force is provided in the Supplementary Materials. Therefore, our all-organic plant e-skin has superior characteristics in transparency, stretchability, biocompatibility, and conformability. Furthermore, micropatterning PEDOT:PSS on the PDMS provides great insights to the plant e-skin for applications with denser integrations. Figure 1I compares our plant e-skin with the state-of-the-art plant electronics, showing that our plant e-skin is the first of its kind to fulfill all the necessary requirements for effective and noninvasive monitoring of plants.

Figure 2 shows the morphology and performance characterization of our plant e-skin patterned into strain sensor and temperature sensor. Regarding the strain sensor, we mixed the base sensing material PEDOT:PSS with 5% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and 5% d-sorbitol as they are the commonly used additives to improve conductivity and stretchability of PEDOT:PSS. As shown in fig. S10, the sheet resistance is improved by two orders of magnitude after the addition of DMSO and d-sorbitol. The additive-processed PEDOT:PSS is defined as p-PEDOT:PSS. The p-PEDOT:PSS film is then sandwiched by a top and bottom PDMS thin film to further enhance its stretchability and stability. Figure 2A exhibits the schematic drawing of the strain sensor. The sensing part is formed by a zig-zag structure where four narrow PEDOT:PSS line resistors are connected in series. It is designed according to the common design guideline of strain gauges (48–51). Three images in Fig. 2B display the zoomed-in structure of the strain sensor, showing the accurate definition of PEDOT:PSS pattern. A typical relative resistance change-strain response of the strain sensor is shown in Fig. 2C. We have characterized the performance of the strain sensor from initial length to a strain of 100%. The resistance change is calculated as

| (1) |

where R0 is the initial resistance of the strain sensor and R is the real-time resistance under strain. It is observed that the values of resistance change increased with increasing strain level. Sensitivity of the strain sensor can be defined as

| (2) |

where ε is the applied strain. When the strain is lower than 60%, GF = 1.15 and it reaches 4.13 when the applied strain is higher than 60%. The observed increase in resistance under tensile strain is predominantly attributed to geometric alterations at small strain levels and the development of cracks in the PEDOT:PSS film at higher strain levels (52–54). A comprehensive elucidation of the strain sensing mechanism, accompanied by scanning electron microscopy images showcasing the phenomenon of crack propagation, is presented in text S1, along with fig. S2. When the e-skin strain sensor was held at specific strains for a period of time, the relative resistance changes remained stable without distinct drifts, affirming the stability of the sensing signals (Fig. 2D). To further verify the long-term stability of the e-skin strain sensor, we recorded its resistance for approximately 6 days as shown in Fig. 2E. The results demonstrate minimal fluctuations in resistance throughout the entire duration, confirming its effectiveness for prolonged monitoring of plant leaves.

Fig. 2. Electrical performance of the plant e-skin functioning as strain sensor and temperature sensor.

(A) Schematic illustration of the strain sensor. (B) Zoomed-in structure of the sensing region of the strain sensor. Inset: Morphology of the processed PEDOT:PSS (p-PEDOT:PSS) patterns on the PDMS substrate. Scale bar, 500 μm. (C) Relative resistance change of the e-skin strain sensor under different applied strains. (D) Stability test of the relative resistance change under varying strain levels. (E) Long-term stability test of the strain sensor. (F) Schematic illustration of the temperature sensor. (G) Morphology of the PEDOT:PSS patterns on the PDMS substrate. Scale bar, 500 μm. (H) Relative resistance change and temperature response of the temperature sensor.

In addition to functioning as a strain sensor, our plant e-skin offers the convenience of easily transforming into a temperature sensor by modifying the device morphology and leveraging the thermoresistive effect in PEDOT:PSS. Prior investigations have affirmed that the conductivity characteristics of PEDOT:PSS thin films align with the variable range hopping model, demonstrating a discernible decrease in resistivity as temperature increases (55–57). A comprehensive elucidation of its temperature-dependent conductivity is provided in text S2. This e-skin temperature sensor is developed based on the pure PEDOT:PSS as the sensing layer and PDMS as the substrate and encapsulation layers as well. As shown in Fig. 2 (F and G), the sensing part of the temperature sensor is patterned into a meander shape to minimize the fluctuations caused by strain (15, 58). The performance of our temperature sensor is characterized by measuring the relative resistance change across a temperature range of 24° to 39°C. A negative linear relationship between relative resistance change and temperature is observed (Fig. 2H). This is attributed to the enhanced charge transport within the PEDOT:PSS percolation network at higher temperature, and the insulting PSS chains being more extended and aligned to facilitate stronger intermolecular interactions between conductive PEDOT particles. Temperature coefficient of resistance (TCR) is used to quantify the performance of our temperature sensor, which is defined as

| (3) |

where R is the resistance under temperature T, and R0 is the resistance under temperature T0.

As revealed from the slope in Fig. 2H, the TCR of our temperature sensor is approximately 0.5%/°C.

On-leaf biocompatibility test and monitoring

Biocompatibility is a critical prerequisite for plant sensors, particularly those designed to establish intimate contact with biological tissues. To assess the application potential of our plant e-skin for nondisruptive plant monitoring, we conducted extended on-plant monitoring tests. First, we examined their biocompatibility by attaching them to the leaves of Epipremnum aureum as shown in Fig. 3A. Throughout the 65-day experiment, no signs of leaf yellowing or withering were observed. Notably, not only did the three original small roots exhibit elongation but also new roots and leaves emerged (indicated by the yellow arrows). In addition, we conducted similar investigation in two other pots, each initially containing one or two leaves, as photographed in fig. S11. Both pots exhibited the development of new roots and leaves during the monitoring period. The observed growth of plants in all the pots strongly suggests that the plant e-skin used in the experiment displayed biocompatibility, with no adverse effects on plant rooting, sprouting, or overall growth. Photosynthesis is crucial for plants as it is the process through which they convert sunlight, water, and carbon dioxide into energy-rich sugars, providing the foundation for their growth, metabolism, and overall physiological functions. Despite the extensive efforts devoted to plant sensors with various functions, the potential long-term effects of on-leaf attachments on photosynthesis have received limited attention. Carbon-based flexible materials, though commonly used in flexible electronics and wearable sensors, may not be ideal candidates for plant sensors because of their inadequate optical transmittance in the visible light range. To demonstrate the necessity of visible optical transmittance for nondisruptive on-leaf monitoring, we attached the plant e-skin and a carbon-based black film on one leaf of B. rapa (oilseed sarson) for 14 days. After removing the two films, the region covered by the plant e-skin showed no obvious change, while the one underneath the black film exhibited discoloration, indicating the reduction of chlorophyll content in the applied area (fig. S12). This suggests that device blocking light transmission can significantly affect the biological composition of the monitored leaves, potentially causing damage to the overall plant health over extended monitoring periods. On top of light absorption, carbon dioxide absorption and oxygen release are also important aspects in photosynthesis. Stomata, which are the pores for gas exchange, are primarily distributed on the abaxial (bottom) side of leaves in dicotyledonous plant species (59). Optical images of stomatal distribution on both adaxial (top) and abaxial (bottom) surfaces of different kinds of leaves verify this phenomenon in fig. S13. Because our e-skin is attached on the top side of the leaves with few stomata, it would not impede normal gas exchange in photosynthesis. Meanwhile, both PEDOT:PSS film and PDMS are reported to be gas and vapor permeable (60–66). Thus, our e-skin shows negligible impact during photosynthesis. Besides, we also attached the plant e-skin and two adhesive tapes on the B. rapa leaf. The adhesive tapes are often used in many plant sensors to help adhesion on the leaves. We observed that the plant e-skin could be removed successfully without destroying the leaf. In contrast, the removal of the two adhesive tapes resulted in the detrimental rupture of the leaves (fig. S14). Thus, our plant e-skin exhibits mechanical invisibility to plants with noninvasive monitoring capability both during and after tests. Considering the need for frequent watering in plants, we conducted additional investigations to assess the waterproof capability of the plant e-skin, as shown in fig. S15 and movie S1. The results demonstrate that the plant e-skin maintains strong adhesion to the leaf surface even when substantial amount of water was poured over it.

Fig. 3. On-leaf biocompatibility test and monitoring.

(A) Biocompatibility test of the plant e-skin with plants. (B) Photograph of the plant e-skin as strain sensor attached on the B. rapa leaf. (C) Performance of the strain sensor to monitor the growth pattern of B. rapa leaf during a 3-day period. (D) Photograph of the plant e-skin as temperature sensor attached on the B. rapa leaf. (E) Performance of the temperature sensor to monitor the surface temperature of the B. rapa leaf during a 3-day period (first day: light on; the following 2 days: light on/off, 16 hours/8 hours).

After confirming the biocompatibility and operation in a noninvasive manner, the strain sensor and temperature sensor were applied to monitor the growth and temperature of the leaves. Monitoring the growth of leaves, especially in leafy vegetables like Brassica, poses distinct challenges compared to tracking the expansion of fruits or detecting elongation in larger crop stems. The fragility and small size of leaves make it difficult to monitor their growth. Although nondestructive imaging has been widely used, tracking the growth of a single leaf typically requires mechanical fixation to keep it within the camera’s focal plane. However, this fixation method unavoidably restricts the plant’s regular physiological processes, potentially affecting its overall development. Our plant e-skin strain sensor that is specifically designed to cater to the unique demands of monitoring the growth of delicate and petite leaves should be able to record the elongation of the leaves while ensuring minimal disruption to the plant natural processes. As photographed in Fig. 3B, the strain sensor was uniformly attached to the juvenile leaf of a B. rapa to monitor its growth. The experimental growth chamber was maintained at a photoperiod of 16 hours of light and 8 hours of darkness. Figure 3C depicts the recorded relative resistance change of the strain sensor during a 3-day period, where the increase of the relative resistance change reveals the extension of the monitored leaves, i.e., growth. Leaf growth exhibited noncontinuous patterns, aligning with known growth behaviors where plants use stored energy to grow and elongate during nighttime while absorbing light for photosynthesis during the day (67–69). The growth condition of the leaf was estimated by quantifying the total relative resistance change. It indicated that the region of the leaf covered by the plant e-skin grew to 1.5 times its original length over the course of 3 days. Notably, because the stretching of strain sensor will exert a reactive force on the plant, we further investigated the influence of this force on plant growth and it turns out that such force does not hinder overall plant growth (fig. S16). The successful monitoring of this growth pattern of the leaf again reflects the secure attachment of the e-skin sensor to the leaf and the reliable performance of the strain sensor.

Simultaneously, the e-skin temperature sensor was also attached to the leaf surface to monitor its temperature, as displayed in Fig. 3D. The B. rapa was cultivated within a temperature-controlled growth chamber, which was maintained at a constant temperature of 26°C. On the first day, the light was continuously switched on, while during the following 2 days, the light was set in a photoperiod regimen consisting of 16 hours of light and 8 hours of darkness. The measured temperature data, as depicted in Fig. 3E, show that the temperature remained at stable 26°C when the light was constantly on. However, the temperature dropped significantly to a lower temperature of 19°C when light was switched off. Despite the chamber being regulated to a constant temperature, there were temperature variations on the surface of the plants. This phenomenon can be attributed to the heat emitted by the light when it is turned on, while no heat emission occurs during darkness. The temperature recording capability of the sensor, attached to the leaf surface, is thus confirmed. The distinctive role that this epidermal temperature sensor can fulfill is not achievable by commercially available temperature sensors, which lack the capability to monitor surface temperatures at a local scale. Consequently, this temperature sensor holds immense potential for acquiring the temperature on the leaf surface, thereby mitigating heat stress in leaves caused by excessive exposure to heat. It should be highly beneficial for precise cultivation of crops with high economic values.

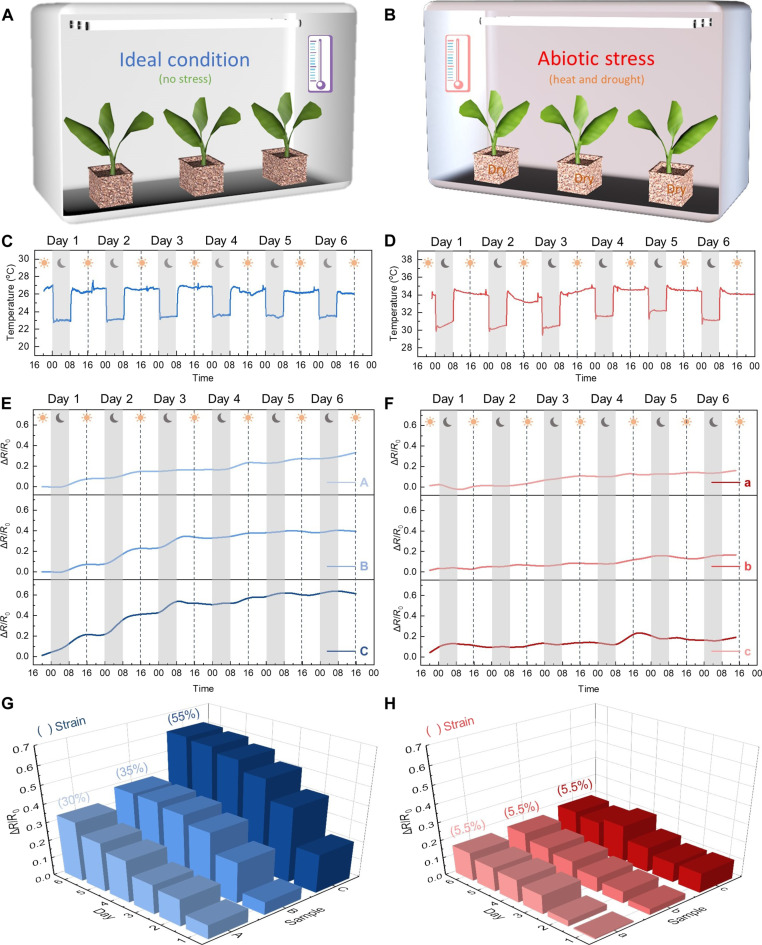

Growth and surface temperature monitoring of B. rapa under abiotic stress

To demonstrate the practicality of our plant e-skin across distinct growing environment, we deployed the e-skin strain and temperature sensors on vegetative leaves of B. rapa, under both optimal environmental condition and abiotic stress condition, and monitored their respective growth metrics. Our investigation was centered on observing the growth patterns of plants in the presence of specific abiotic stressors, like combined heat and drought, which simulate real-world plant stressors typically encountered in farming environments. As schematically delineated in Fig. 4 (A and B), the ideal growth conditions for B. rapa were ensured by providing suitable temperature (26°C light/23°C dark) and sufficient water, whereas a separate group of plants was subjected to combined heat and drought stress by disrupting water supply and raising temperatures to 8°C above control conditions (34°C light/31°C dark). Figure 4C illustrates the diurnal variation in surface temperature of leaves in the control group, which fluctuated between 26° and 22°C. In contrast, the leaf surface temperature for the group under abiotic stress, as illustrated in Fig. 4D, was recorded with fluctuations in higher temperatures of approximately 34°C during the day and 30°C at night. These observed temperature patterns align well with the preset parameters for both scenarios, thereby affirming temperature sensing capabilities of the newly developed epidermal sensors. Notably, the small variations between epidermal sensors and chamber’s temperature setting could be attributed to the uniformity of the temperature in the chambers. Strain sensors were attached to three juvenile leaves in both the control group (labeled as A, B, and C) and the abiotic stress group (labeled as a, b, and c). Figure 4E presents the growth patterns of the leaves in the control group, demonstrating that all three leaves exhibited discernible growth, as indicated by the increasing relative resistance changes. This growth was more pronounced during the night, followed by a plateau phase during the day, sharing a similar growth rhythm as mentioned before. However, the results depicted in Fig. 4F indicate that the group subjected to abiotic stress did not exhibit any significant change in resistance, implying a disruption in growth. Figure 4 (G and H) illustrates the calculated relative resistance change of the applied strain sensors in the control group and the abiotic stress group, respectively. In the control group, the relative resistance change corresponds to approximately 30, 35, and 55% growth strain for the three leaves, while the abiotic stress group recorded mere 5.5% strain across all three leaves. It is anticipated that the growth rates of the leaves exhibit variations across plants and leaves, accounting for different strain levels recorded for the three leaves in the control group. Nonetheless, under the impact of abiotic stress, the detrimental impact pervasively inhibited the growth across all the leaves. These results validate a pragmatic strategy to monitor the leaves if they are under certain abiotic stress in smart farming. The developed temperature sensors can record leaf surface temperatures, and the strain sensors can relay comprehensive information on plant growth status. The integration of both sensor types offers real-time data to agricultural practitioners, enabling prompt intervention to avert suboptimal plant growth. Furthermore, the developed sensors equip plant researchers with a more efficient, noninvasive approach to identify heat-resistant plant varieties and establish optimal growth temperatures. The pragmatic applications underscore considerable potential of our innovative sensors in both plant research and the broader context of smart agriculture.

Fig. 4. Long-term plant monitoring under normal and abiotic stress applied conditions.

(A) Schematic illustration of the plants cultivated in an ideal condition (control group). (B) Schematic illustration of the plants cultivated experiencing abiotic stress including heat and drought (stress group). (C) Surface temperature of the leaf in the control group. (D) Surface temperature of the leaf in stress group. (E) Growth patterns of the B. rapa leaves in the control group. (F) Growth patterns of the B. rapa leaves in stress group. (G) Calculated resistance change and extension of the leaves in the control group. (H) Calculated resistance change and extension of the leaves in stress group.

Digital-twin plant in smart farming

A digital-twin communication system has been developed as a smart farmer-farm interface to enrich the visualization of the plants’ status. Figure 5A depicts the information flow of the sensing signals. The described system, diagrammatically represented in Fig. 5A, uses sensors positioned on plant surfaces to record leaf surface temperatures. The collected data undergo conditioning by an electrical circuit, followed by processing and analog-digital conversion via an Arduino board. The generated digital output governs the behavior of a digital-twin plant in the virtual reality (VR) environment as displayed on the personal computer (PC), thereby allowing the leaf surface temperature in physical space to be mirrored by the color of the digital-twin leaf in the VR space. Figure 5B vividly demonstrates the instantaneous transference of real-space plant surface temperature to the VR counterpart. The objective is to simulate localized overheating scenario in precision agriculture, where the whole farming environment maintains a constant overall temperature. In this demonstration, four transparent e-skin temperature sensors are independently attached to four separate plants and connected to the communication system. The side view provides a clear identification of each plant’s location, denoted as ①, ②, ③, and ④. On the computer monitor, a VR space displays the corresponding leaf temperatures, initially recorded as 297.1, 297.3, 296.7, and 296.8 K under normal conditions. The top view focuses on two specific plants, ① and ②, situated in the upper shelf region where localized heating is mostly expected to occur. Temperature thresholds at 300 and 302 K are set to represent warm and overheating states, respectively, which are visualized by changing the digital-twin leaf color to yellow and red. Notably, the thresholds of 300 and 302 K are only chosen to emulate the warm and overheating state and do not represent the actual warm and overheating state of any specific plant. In practical applications, the threshold temperature can vary significantly from different types of plants and be set accordingly. In Fig. 5C, a mild, localized overheat was simulated by bringing a warm object (327 K) close to plant ①, causing only its temperature to increase, while the other three remain unaffected. This leads to a color shift in the corresponding digital-twin plant, transitioning it from green to yellow once the temperature reached 300 K. In Fig. 5D, as a hot object (338 K) approaches plant ②, heat transmission resulted in a color shift of the digital-twin plant, from green to yellow and eventually to red, denoting the occurrence of an extreme heat stress in that specific area. Upon removal of the hot object, the temperature gradually decreases, as depicted by a color transition in the VR space from red to yellow and finally to green. The dynamic recording of the whole process can be found in movie S2. The digital-twin plant system thus demonstrates its practicality in translating the real-world plants into the VR space, visualizing distinct temperature states through intuitive color changes of the corresponding digital-twin plants. In addition to the proposed localized overheating monitoring, this digital-twin plant system can encompass plant growth surveillance by harnessing a strain sensor to gather leaf growth information. This innovative system potentially provides a visual platform for meticulous and timely monitoring in smart farming.

Fig. 5. Application of the plant e-skin as a digital-twin plant monitoring interface.

(A) Information flow of the sensing signals to project plants in real space to the digital counterpart in virtual space. (B) Photograph and screenshot to exhibit plants in real space and their counterparts in VR space with corresponding temperature information. (C) Photograph and screenshot of the plants with one typical plant contacting with a warm object and the corresponding response in their VR counterparts. (D) Photograph and screenshot of the plants with one typical plant contacting with a hot object and the corresponding response of their VR counterparts.

DISCUSSION

We have demonstrated an all-organic plant e-skin that can be conformably attached to and seamlessly integrated with plants to noninvasively monitor their physiological status. By developing a scalable microfabrication process using only organic PEDOT:PSS as conductive components and PDMS as substrates, we achieved biocompatibility, transparency, stretchability, and conformability simultaneously in our plant e-skin. Our reported 4.5-μm-thick plant e-skin with more than 85% transmittance across the visible spectrum are optically and mechanically invisible to plants, thus enabling long-term and real-time monitoring without any observable adverse effects to plant health. Leveraging these characteristics, we configured our plant e-skin into strain sensors and temperature sensors and achieved long-duration real-time plant growth and surface temperature monitoring. The on-plant monitoring results revealed the day/night leaf growth rhythms and the accompanying leaf surface temperature variations, demonstrating the capability of our plant e-skin to measure plant physiological signals for practical applications. It is worth noting that such capability of transducing real-time plant physiological signals is especially crucial for accelerating desirable phenotypes during precision breeding of new plant varieties. Furthermore, we constructed a digital-twin plant monitoring system as a farmer-farm interface to visualize the thermal status of leaf surface in real time. While the minimum feature size we achieved in the present study is 2 μm, it is limited by the resolution of our lithography system. In principle, this minimum feature size can be reduced to submicrometer range for more dense integration. Apart from the demonstrated strain sensor and temperature sensor, other types of sensors can be expected by using the morphology and design flexibility offered by our scalable fabrication technique. We have preliminarily demonstrated the possibility of developing a flexible humidity sensor for monitoring the microenvironment of plants (fig. S17). In the future, the use of embedded conducting coils in the sensors is expected to enable wireless communication between plant e-skin and processors. Beyond plant growth monitoring applications, our demonstrated technology is also broadly applicable to epidermal electronics for human wearable and implantable devices.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

All the materials and chemicals used in this study are commercially available. polyvinyl alcohol (PVA; molecular weight = 89,000 to 98,000), PEDOT:PSS (1.3 wt % dispersion in H2O), d-sorbitol, and DMSO were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. PDMS (SYLGARD 184 Silicone Elastomer Kit) was purchased from Dow Corning.

Fabrication of plant e-skin

The scalable fabrication process is schematically demonstrated in fig. S4. PVA aqueous solution (8 wt % in H2O) was initially spin-coated onto a clean and smooth wafer at 800 rpm for 30 s, acting as a sacrificial layer. Then, PDMS, prepared as a mixture of the elastomer base and a curing agent at a weight ratio of 20:1, was spin-coated at 8000 rpm for 4 min, creating the substrate layer for the epidermal electronics. A plasma treatment was carried out to render the PDMS surface hydrophilic [6 sccm (standard cubic centimeter per minute), 30 W, 30 s], facilitating the subsequent coating of the photoresist AZ-1512 at 800 rpm for 25 s. AZ-1512 was baked overnight at 65°C in the oven with temperature increasing and decreasing slowly to eliminate cracking of the AZ-1512 film caused by the thermal extension and cold contraction of the PDMS film under rapid and high temperature variation. Subsequently, a mask aligner (MA8, Micro Suss) was used to expose the micropatterns on the AZ-1512 film, allowing the desired PDMS pattern exposed without covering AZ-1512 after development in the MF 319 for 40 s. Thereafter, with additional plasma treatment, the sensing material [p-PEDOT:PSS (mixture of PEDOT:PSS, 5 wt % DMSO and 5 wt % d-sorbitol) for strain sensor and PEDOT:PSS for temperature sensor] was spin-coated onto the wafer at 1500 rpm for 30 s. Next, the lift-off process was conducted to remove AZ-1512 in acetone, and the remaining region was the PEDOT:PSS-based pattern on the PDMS substrate. In such case, the sensing film was successfully micropatterned on the PDMS film. Detailed parameters of the feature size of both sensors are illustrated in fig. S18. The subsequent steps included encapsulating the sensing films and connection to the external wire, which are crucial to ensure a good and reliable recording of the sensory output. To partially seal the sensing part while leaving the connection pads exposed for external wire connection, nonadhesive parafilm was used to cover the connection pads before spin-coating of PDMS (8000 rpm for 4 min) as the encapsulation layer on the sensing part. In addition, the parafilm was removed immediately after spin-coating to expose the connection pads again. Once the PDMS encapsulation layer was solidified, ultrathin copper wires were affixed to the two connection pads using Ag paste and liquid metal. Low-Young’s-modulus liquid metal was used to reinforce stability against potential cracks in the Ag paste or disruption to PEDOT:PSS films especially at the PEDOT:PSS-Ag paste junction induced by the Ag paste’s sharpness. Last, the connection pads together with the liquid metal and external wires were encapsulated manually with PDMS to obtain the final sensor. For further application, the epidermal sensors can be gently peeled off from the holding wafer and attached to the target objects such as the plant leaves.

Sensor characterization

The microstructure morphology of the PEDOT:PSS patterns on the PDMS film was characterized via the optical microscope (Nikon, Eclipse L200 L300). The optical transmission of the developed sensor was characterized by a universal measurement spectrophotometer (Agilent, Cary 7000 UV-Vis-NIR). The thickness of the developed sensor was measured by the surface profile (Bruker, DektakXT) and atomic force microscopy (Bruker Dimension Icon). Sheet resistance was measured by a four-probe measurement system (AiT, CMT-SR2000N). Photographs and videos were acquired by an iPhone 14 camera. The force gauge (Mecmesin, MultiTest 2.5-i) was used to conduct stretching deformation for shear adhesion force and strain sensor characterization. The resistance of strain sensor under each strain level was measured by the programmable electrometer (Keithley, 6514), and an oscilloscope (Agilent, InfiniiVision, DSO-X3034A) was connected to the electrometer using a bayonet nut coupling (BNC) cable for real-time data acquisition. The temperature sensor was characterized using a hot plate to control its temperature, and the electrical resistance was recorded by a digital multimeter (Sanwa, CD800a). When connected to Arduino MEGA 2560 for real-time data acquisition, every temperature sensor was calibrated using the hot plate before applying on the plant leaves to obtain the relationship between sensory output and temperature.

Cultivation of the host B. rapa plant and stress application

The oilseed sarson seeds were sown in soil and grown under standard long-day conditions (16-hour light/8-hour dark period), 60% humidity and 26°C light/23°C dark. After about 3 weeks, six plants were selected for sensor attachment with three for the control group and three for the abiotic stress group. Plants in the control group were then placed in the chamber under standard growth conditions (16-hour light/8-hour dark period, 60% humidity, 26°C light/23°C dark), and the other three were placed in another chamber where they were subjected to heat and drought stress (16-hour light/8-hour dark period, 60% humidity, 34°C light/31°C dark). Plants in the control group were watered well throughout the experiment, while the plants in the stress group did not receive water once the sensors were attached, to initiate drought condition.

Demonstration of digital-twin plants in VR space

Four epidermal temperature sensors were connected to the conditional circuit for conversion from the resistance change to voltage change as well as amplifying the voltage signals. The generated data were sent to a microcontroller (Arduino MEGA 2560) for data processing and communication with a laptop computer through a universal serial bus (USB) cable. The real-time signals received by the laptop computer were processed in Python, and the corresponding commands were sent to Unity 3D through Transmission Control Protocol/Internet Protocol (TCP/IP) communication for digital-twin plant control.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by Reimagine Research Scheme projects, National University of Singapore, A-0009037-03-00 and A-0009454-01-00 (to C.L.); RIE Advanced Manufacturing and Engineering (AEM) programmatic grant, A*STAR under the “Nanosystems at the Edge” program, A18A4b0055 (to C.L.); National Research Foundation Singapore grant, CRP28-2022-0038 (to C.L.); and Reimagine Research Scheme projects, National University of Singapore, A-0004772-00-00 and A-0004772-01-00 (to E.C.).

Author contributions: Conceptualization: F.W., Y.Y., C.L., P.P.K., E.C., T.H., and P.R. Methodology: F.W., Y.Y., C.L., P.K., and T.H. Investigation: F.W., Z.Z., Y.Y., P.K., T.H., and P.R. Visualization: Z.Z., Y.Y., T.H., P.R., and L.W. Supervision: Z.Z., Y.Y., C.L., P.P.K., E.C., T.H., and P.R. Writing—original draft: Y.Y. and T.H. Writing—review and editing: Y.Y., P.K., P.P.K., E.C., T.H., and P.R.

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials.

Supplementary Materials

This PDF file includes:

Texts S1 and S2

Figs. S1 to S18

Table S1

Legends for movies S1 and S2

References

Other Supplementary Material for this manuscript includes the following:

Movies S1 and S2

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Zurek M., Hebinck A., Selomane O., Climate change and the urgency to transform food systems. Science 376, 1416–1421 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tilman D., Balzer C., Hill J., Befort B. L., Global food demand and the sustainable intensification of agriculture. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 20260–20264 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tester M., Langridge P., Breeding technologies to increase crop production in a changing world. Science 327, 818–822 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Araus J. L., Cairns J. E., Field high-throughput phenotyping: The new crop breeding frontier. Trends Plant Sci. 19, 52–61 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Steinwand M. A., Ronald P. C., Crop biotechnology and the future of food. Nat. Food 1, 273–283 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hickey L. T., Hafeez A. N., Robinson H., Jackson S. A., Leal-Bertioli S. C. M., Tester M., Gao C., Godwin I. D., Hayes B. J., Wulff B. B. H., Breeding crops to feed 10 billion. Nat. Biotechnol. 37, 744–754 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang Q., Ying Y., Ping J., Recent advances in plant nanoscience. Adv. Sci. 9, e2103414 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Volpato L., Pinto F., González-Pérez L., Thompson I. G., Borém A., Reynolds M., Gérard B., Molero G., Rodrigues F. A., High throughput field phenotyping for plant height using UAV-based RGB imagery in wheat breeding lines: Feasibility and validation. Front. Plant Sci. 12, 591587 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Atefi A., Ge Y., Pitla S., Schnable J., Robotic technologies for high-throughput plant phenotyping: Contemporary reviews and future perspectives. Front. Plant Sci. 12, 611940 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Matsuura Y., Heming Z., Nakao K., Qiong C., Firmansyah I., Kawai S., Yamaguchi Y., Maruyama T., Hayashi H., Nobuhara H., High-precision plant height measurement by drone with RTK-GNSS and single camera for real-time processing. Sci. Rep. 13, 6329 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Qu C. C., Sun X. Y., Sun W. X., Cao L. X., Wang X. Q., He Z. Z., Flexible wearables for plants. Small 17, 2104482 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yin H., Cao Y., Marelli B., Zeng X., Mason A. J., Cao C., Soil sensors and plant wearables for smart and precision agriculture. Adv. Mater. 33, e2007764 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nagelmüller S., Kirchgessner N., Yates S., Hiltpold M., Walter A., Leaf length tracker: A novel approach to analyse leaf elongation close to the thermal limit of growth in the field. J. Exp. Bot. 67, 1897–1906 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Atherton J. J., Rosamond M. C., Zeze D. A., A leaf-mounted thermal sensor for the measurement of water content. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 187, 67–72 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim D.-H., Lu N., Ma R., Kim Y.-S., Kim R.-H., Wang S., Wu J., Won S. M., Tao H., Islam A., Yu K. J., Kim T., Chowdhury R., Ying M., Xu L., Li M., Chung H.-J., Keum H., McCormick M., Liu P., Zhang Y.-W., Omenetto F. G., Huang Y., Coleman T., Rogers J. A., Epidermal electronics. Science 333, 838–843 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gao W., Emaminejad S., Nyein H. Y. Y., Challa S., Chen K., Peck A., Fahad H. M., Ota H., Shiraki H., Kiriya D., Lien D.-H., Brooks G. A., Davis R. W., Javey A., Fully integrated wearable sensor arrays for multiplexed in situ perspiration analysis. Nature 529, 509–514 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Luo Y., Abidian M. R., Ahn J.-H., Akinwande D., Andrews A. M., Antonietti M., Bao Z., Berggren M., Berkey C. A., Bettinger C. J., Chen J., Chen P., Cheng W., Cheng X., Choi S.-J., Chortos A., Dagdeviren C., Dauskardt R. H., Di C., Dickey M. D., Duan X., Facchetti A., Fan Z., Fang Y., Feng J., Feng X., Gao H., Gao W., Gong X., Guo C. F., Guo X., Hartel M. C., He Z., Ho J. S., Hu Y., Huang Q., Huang Y., Huo F., Hussain M. M., Javey A., Jeong U., Jiang C., Jiang X., Kang J., Karnaushenko D., Khademhosseini A., Kim D.-H., Kim I.-D., Kireev D., Kong L., Lee C., Lee N.-E., Lee P. S., Lee T.-W., Li F., Li J., Liang C., Lim C. T., Lin Y., Lipomi D. J., Liu J., Liu K., Liu N., Liu R., Liu Y., Liu Y., Liu Z., Liu Z., Loh X. J., Lu N., Lv Z., Magdassi S., Malliaras G. G., Matsuhisa N., Nathan A., Niu S., Pan J., Pang C., Pei Q., Peng H., Qi D., Ren H., Rogers J. A., Rowe A., Schmidt O. G., Sekitani T., Seo D.-G., Shen G., Sheng X., Shi Q., Someya T., Song Y., Stavrinidou E., Su M., Sun X., Takei K., Tao X.-M., Tee B. C. K., Thean A. V.-Y., Trung T. Q., Wan C., Wang H., Wang J., Wang M., Wang S., Wang T., Wang Z. L., Weiss P. S., Wen H., Xu S., Xu T., Yan H., Yan X., Yang H., Yang L., Yang S., Yin L., Yu C., Yu G., Yu J., Yu S.-H., Yu X., Zamburg E., Zhang H., Zhang X., Zhang X., Zhang X., Zhang Y., Zhang Y., Zhao S., Zhao X., Zheng Y., Zheng Y.-Q., Zheng Z., Zhou T., Zhu B., Zhu M., Zhu R., Zhu Y., Zhu Y., Zou G., Chen X., Technology roadmap for flexible sensors. ACS Nano 17, 5211–5295 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Choi D., Lee Y., Lin Z.-H., Cho S., Kim M., Ao C. K., Soh S., Sohn C., Jeong C. K., Lee J., Lee M., Lee S., Ryu J., Parashar P., Cho Y., Ahn J., Kim I.-D., Jiang F., Lee P. S., Khandelwal G., Kim S.-J., Kim H. S., Song H.-C., Kim M., Nah J., Kim W., Menge H. G., Park Y. T., Xu W., Hao J., Park H., Lee J.-H., Lee D.-M., Kim S.-W., Park J. Y., Zhang H., Zi Y., Guo R., Cheng J., Yang Z., Xie Y., Lee S., Chung J., Oh I.-K., Kim J.-S., Cheng T., Gao Q., Cheng G., Gu G., Shim M., Jung J., Yun C., Zhang C., Liu G., Chen Y., Kim S., Chen X., Hu J., Pu X., Guo Z. H., Wang X., Chen J., Xiao X., Xie X., Jarin M., Zhang H., Lai Y.-C., He T., Kim H., Park I., Ahn J., Huynh N. D., Yang Y., Wang Z. L., Baik J. M., Choi D., Recent advances in triboelectric nanogenerators: From technological progress to commercial applications. ACS Nano 17, 11087–11219 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang Y., Guo X., Zhu M., Sun Z., Zhang Z., He T., Lee C., Triboelectric nanogenerator enabled wearable sensors and electronics for sustainable internet of things integrated green earth. Adv. Energy Mater. 13, 2203040 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shi Q., Sun Z., Zhang Z., Lee C., Triboelectric nanogenerators and hybridized systems for enabling next-generation IoT applications. Research 2021, 6849171 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang C., He T., Zhou H., Zhang Z., Lee C., Artificial intelligence enhanced sensors—Enabling technologies to next-generation healthcare and biomedical platform. Bioelectron. Med. 9, 17 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen J., He T., Du Z., Lee C., Review of textile-based wearable electronics: From the structure of the multi-level hierarchy textiles. Nano Energy 117, 108898 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang Z., He T., Zhu M., Sun Z., Shi Q., Zhu J., Dong B., Yuce M. R., Lee C., Deep learning-enabled triboelectric smart socks for IoT-based gait analysis and VR applications. npj Flex. Electron. 4, 29 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Giraldo J. P., Wu H., Newkirk G. M., Kruss S., Nanobiotechnology approaches for engineering smart plant sensors. Nat. Nanotechnol. 14, 541–553 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee G., Wei Q., Zhu Y., Emerging wearable sensors for plant health monitoring. Adv. Funct. Mater. 31, 2106475 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nassar J. M., Khan S. M., Villalva D. R., Nour M. M., Almuslem A. S., Hussain M. M., Compliant plant wearables for localized microclimate and plant growth monitoring. npj Flex. Electron. 2, 24 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tang W., Yan T., Wang F., Yang J., Wu J., Wang J., Yue T., Li Z., Rapid fabrication of wearable carbon nanotube/graphite strain sensor for real-time monitoring of plant growth. Carbon 147, 295–302 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yin S., Ibrahim H., Schnable P. S., Castellano M. J., Dong L., A field-deployable, wearable leaf sensor for continuous monitoring of vapor-pressure deficit. Adv. Mater. Technol. 6, 2001246 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lu Y., Xu K., Zhang L., Deguchi M., Shishido H., Arie T., Pan R., Hayashi A., Shen L., Akita S., Takei K., Multimodal plant healthcare flexible sensor system. ACS Nano 14, 10966–10975 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Im H., Lee S., Naqi M., Lee C., Kim S., Flexible PI-based plant drought stress sensor for real-time monitoring system in smart farm. Electronics 7, 114 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhao F., He J., Li X., Bai Y., Ying Y., Ping J., Smart plant-wearable biosensor for in-situ pesticide analysis. Biosens. Bioelectron. 170, 112636 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li Z., Liu Y., Hossain O., Paul R., Yao S., Wu S., Ristaino J. B., Zhu Y., Wei Q., Real-time monitoring of plant stresses via chemiresistive profiling of leaf volatiles by a wearable sensor. Matter 4, 2553–2570 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Luo Y., Li W., Lin Q., Zhang F., He K., Yang D., Loh X. J., Chen X., A morphable ionic electrode based on thermogel for non-invasive hairy plant electrophysiology. Adv. Mater. 33, e2007848 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li W., Matsuhisa N., Liu Z., Wang M., Luo Y., Cai P., Chen G., Zhang F., Li C., Liu Z., Lv Z., Zhang W., Chen X., An on-demand plant-based actuator created using conformable electrodes. Nat. Electron. 4, 134–142 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Armada-Moreira A., Dar A. M., Zhao Z., Cea C., Gelinas J., Berggren M., Costa A., Khodagholy D., Stavrinidou E., Plant electrophysiology with conformable organic electronics: Deciphering the propagation of Venus flytrap action potentials. Sci. Adv. 9, eadh4443 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee G., Hossain O., Jamalzadegan S., Liu Y., Wang H., Saville A. C., Shymanovich T., Paul R., Rotenberg D., Whitfield A. E., Ristaino J. B., Zhu Y., Wei Q., Abaxial leaf surface-mounted multimodal wearable sensor for continuous plant physiology monitoring. Sci. Adv. 9, eade2232 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang C., Zhang C., Wu X., Ping J., Ying Y., An integrated and robust plant pulse monitoring system based on biomimetic wearable sensor. npj Flex. Electron. 6, 43 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tang W., Yan T., Ping J., Wu J., Ying Y., Rapid fabrication of flexible and stretchable strain sensor by chitosan-based water ink for plants growth monitoring. Adv. Mater. Technol. 2, 1700021 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jiang J., Zhang S., Wang B., Ding H., Wu Z., Hydroprinted liquid-alloy-based morphing electronics for fast-growing/tender plants: From physiology monitoring to habit manipulation. Small 16, e2003833 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kim J. J., Fan R., Allison L. K., Andrew T. L., On-site identification of ozone damage in fruiting plants using vapor-deposited conducting polymer tattoos. Sci. Adv. 6, eabc3296 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kim J. J., Allison L. K., Andrew T. L., Vapor-printed polymer electrodes for long-term, on-demand health monitoring. Sci. Adv. 5, eaaw0463 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chai Y., Chen C., Luo X., Zhan S., Kim J., Luo J., Wang X., Hu Z., Ying Y., Liu X., Cohabiting plant-wearable sensor in situ monitors water transport in plant. Adv. Sci. 8, 2003642 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhao Y., Gao S., Zhu J., Li J., Xu H., Xu K., Cheng H., Huang X., Multifunctional stretchable sensors for continuous monitoring of long-term leaf physiology and microclimate. ACS Omega 4, 9522–9530 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zheng Y.-Q., Liu Y., Zhong D., Nikzad S., Liu S., Yu Z., Liu D., Wu H.-C., Zhu C., Li J., Tran H., Tok J. B. H., Bao Z., Monolithic optical microlithography of high-density elastic circuits. Science 373, 88–94 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang S., Xu J., Wang W., Wang G.-J. N., Rastak R., Molina-Lopez F., Chung J. W., Niu S., Feig V. R., Lopez J., Lei T., Kwon S.-K., Kim Y., Foudeh A. M., Ehrlich A., Gasperini A., Yun Y., Murmann B., Tok J. B. H., Bao Z., Skin electronics from scalable fabrication of an intrinsically stretchable transistor array. Nature 555, 83–88 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liang J., Li L., Chen D., Hajagos T., Ren Z., Chou S.-Y., Hu W., Pei Q., Intrinsically stretchable and transparent thin-film transistors based on printable silver nanowires, carbon nanotubes and an elastomeric dielectric. Nat. Commun. 6, 7647 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhou T., Yuk H., Hu F., Wu J., Tian F., Roh H., Shen Z., Gu G., Xu J., Lu B., Zhao X., 3D printable high-performance conducting polymer hydrogel for all-hydrogel bioelectronic interfaces. Nat. Mater. 22, 895–902 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Huang Y.-T., Huang S.-C., Hsu C.-C., Chao R.-M., Vu T. K., Design and fabrication of single-walled carbon nanonet flexible strain sensors. Sensors 12, 3269–3280 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Agarwala S., Goh G. L., Yeong W. Y., Aerosol jet printed strain sensor: Simulation studies analyzing the effect of dimension and design on performance (September 2018). IEEE Access 6, 63080–63086 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 50.Koivikko A., Lampinen V., Pihlajamäki M., Yiannacou K., Sharma V., Sariola V., Integrated stretchable pneumatic strain gauges for electronics-free soft robots. Commun. Eng. 1, 14 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 51.Araromi O. A., Graule M. A., Dorsey K. L., Castellanos S., Foster J. R., Hsu W.-H., Passy A. E., Vlassak J. J., Weaver J. C., Walsh C. J., Wood R. J., Ultra-sensitive and resilient compliant strain gauges for soft machines. Nature 587, 219–224 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fan X., Nie W., Tsai H., Wang N., Huang H., Cheng Y., Wen R., Ma L., Yan F., Xia Y., PEDOT:PSS for flexible and stretchable electronics: Modifications, strategies, and applications. Adv. Sci. 6, 1900813 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fan X., Wang N., Wang J., Xu B., Yan F., Highly sensitive, durable and stretchable plastic strain sensors using sandwich structures of PEDOT:PSS and an elastomer. Mater. Chem. Front. 2, 355–361 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sarkar B., Satapathy D. K., Jaiswal M., Wrinkle and crack-dependent charge transport in a uniaxially strained conducting polymer film on a flexible substrate. Soft Matter 13, 5437–5444 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ouyang J., Xu Q., Chu C.-W., Yang Y., Li G., Shinar J., On the mechanism of conductivity enhancement in poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene):poly(styrene sulfonate) film through solvent treatment. Polymer 45, 8443–8450 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nardes A. M., Kemerink M., Janssen R. A. J., Anisotropic hopping conduction in spin-coated PEDOT:PSS thin films. Phys. Rev. B 76, 085208 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kwon I. W., Son H. J., Kim W. Y., Lee Y. S., Lee H. C., Thermistor behavior of PEDOT:PSS thin film. Synth. Met. 159, 1174–1177 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yeo W., Kim Y., Lee J., Ameen A., Shi L., Li M., Wang S., Ma R., Jin S. H., Kang Z., Huang Y., Rogers J. A., Multifunctional epidermal electronics printed directly onto the skin. Adv. Mater. 25, 2773–2778 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wall S., Vialet-Chabrand S., Davey P., Van Rie J., Galle A., Cockram J., Lawson T., Stomata on the abaxial and adaxial leaf surfaces contribute differently to leaf gas exchange and photosynthesis in wheat. New Phytol. 235, 1743–1756 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Xu L., Lee H., Jetta D., Oh K. W., Vacuum-driven power-free microfluidics utilizing the gas solubility or permeability of polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS). Lab Chip 15, 3962–3979 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lamberti A., Marasso S. L., Cocuzza M., PDMS membranes with tunable gas permeability for microfluidic applications. RSC Adv. 4, 61415–61419 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 62.Randall G. C., Doyle P. S., Permeation-driven flow in poly(dimethylsiloxane) microfluidic devices. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 10813–10818 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yoon S., Seok M., Kim M., Cho Y.-H., Wearable porous PDMS layer of high moisture permeability for skin trouble reduction. Sci. Rep. 11, 938 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lee J. H., Jung J. P., Jang E., Lee K. B., Hwang Y. J., Min B. K., Kim J. H., PEDOT-PSS embedded comb copolymer membranes with improved CO2 capture. J. Memb. Sci. 518, 21–30 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 65.Shrestha M., Lu Z., Lau G.-K., High humidity sensing by ‘hygromorphic’ dielectric elastomer actuator. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 329, 129268 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 66.Seemann A., Egelhaaf H.-J., Brabec C. J., Hauch J. A., Influence of oxygen on semi-transparent organic solar cells with gas permeable electrodes. Org. Electron. 10, 1424–1428 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 67.Apelt F., Breuer D., Olas J. J., Annunziata M. G., Flis A., Nikoloski Z., Kragler F., Stitt M., Circadian, carbon, and light control of expansion growth and leaf movement. Plant Physiol. 174, 1949–1968 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Fricke W., Night-time transpiration—Favouring growth? Trends Plant Sci. 24, 311–317 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Michael T. P., Breton G., Hazen S. P., Priest H., Mockler T. C., Kay S. A., Chory J., A morning-specific phytohormone gene expression program underlying rhythmic plant growth. PLOS Biol. 6, e225 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Xu S., Fan Z., Yang S., Zuo X., Guo Y., Chen H., Pan L., Highly flexible, stretchable, and self-powered strain-temperature dual sensor based on free-standing PEDOT:PSS/carbon nanocoils–poly(vinyl) alcohol films. ACS Sensors 6, 1120–1128 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.He H., Zhang L., Guan X., Cheng H., Liu X., Yu S., Wei J., Ouyang J., Biocompatible conductive polymers with high conductivity and high stretchability. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 11, 26185–26193 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zhou J., Anjum D. H., Chen L., Xu X., Ventura I. A., Jiang L., Lubineau G., The temperature-dependent microstructure of PEDOT/PSS films: Insights from morphological, mechanical and electrical analyses. J. Mater. Chem. C 2, 9903–9910 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lo L.-W., Zhao J., Wan H., Wang Y., Chakrabartty S., Wang C., An inkjet-printed PEDOT:PSS-based stretchable conductor for wearable health monitoring device applications. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 13, 21693–21702 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Galliani M., Ferrari L. M., Bouet G., Eglin D., Ismailova E., Tailoring inkjet-printed PEDOT:PSS composition toward green, wearable device fabrication. APL Bioeng. 7, 016101 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Chang J., He J., Lei Q., Li D., Electrohydrodynamic printing of microscale PEDOT:PSS-PEO features with tunable conductive/thermal properties. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 10, 19116–19122 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Dadras-Toussi O., Khorrami M., Titus A. S. C. L. S., Majd S., Mohan C., Abidian M. R., Multiphoton lithography of organic semiconductor devices for 3D printing of flexible electronic circuits, biosensors, and bioelectronics. Adv. Mater. 34, e2200512 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Khodagholy D., Doublet T., Gurfinkel M., Quilichini P., Ismailova E., Leleux P., Herve T., Sanaur S., Bernard C., Malliaras G. G., Highly conformable conducting polymer electrodes for in vivo recordings. Adv. Mater. 23, 268–272 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Pal R. K., Farghaly A. A., Collinson M. M., Kundu S. C., Yadavalli V. K., Photolithographic micropatterning of conducting polymers on flexible silk matrices. Adv. Mater. 28, 1406–1412 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Pradhan S., Yadavalli V. K., Photolithographically printed flexible silk/PEDOT:PSS temperature sensors. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 3, 21–29 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 80.Jiang Y., Zhang Z., Wang Y.-X., Li D., Coen C.-T., Hwaun E., Chen G., Wu H.-C., Zhong D., Niu S., Wang W., Saberi A., Lai J.-C., Wu Y., Wang Y., Trotsyuk A. A., Loh K. Y., Shih C.-C., Xu W., Liang K., Zhang K., Bai Y., Gurusankar G., Hu W., Jia W., Cheng Z., Dauskardt R. H., Gurtner G. C., Tok J. B. H., Deisseroth K., Soltesz I., Bao Z., Topological supramolecular network enabled high-conductivity, stretchable organic bioelectronics. Science 375, 1411–1417 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Texts S1 and S2

Figs. S1 to S18

Table S1

Legends for movies S1 and S2

References

Movies S1 and S2