Abstract

Background:

Accurate prognostication of oncological outcomes is crucial for the optimal management of patients with renal cell carcinoma (RCC) after surgery. Previous prediction models were developed mainly based on retrospective data in the Western populations, and their predicting accuracy remains limited in contemporary, prospective validation. We aimed to develop contemporary RCC prognostic models for recurrence and overall survival (OS) using prospective population-based patient cohorts and compare their performance with existing, mostly utilized ones.

Methods:

In this prospective analysis and external validation study, the development set included 11 128 consecutive patients with non-metastatic RCC treated at a tertiary urology center in China between 2006 and 2022, and the validation set included 853 patients treated at 13 medical centers in the USA between 1996 and 2013. The primary outcome was progression-free survival (PFS), and the secondary outcome was OS. Multivariable Cox regression was used for variable selection and model development. Model performance was assessed by discrimination [Harrell’s C-index and time-dependent areas under the curve (AUC)] and calibration (calibration plots). Models were validated internally by bootstrapping and externally by examining their performance in the validation set. The predictive accuracy of the models was compared with validated models commonly used in clinical trial designs and with recently developed models without extensive validation.

Results:

Of the 11 128 patients included in the development set, 633 PFS and 588 OS events occurred over a median follow-up of 4.3 years [interquartile range (IQR) 1.7–7.8]. Six common clinicopathologic variables (tumor necrosis, size, grade, thrombus, nodal involvement, and perinephric or renal sinus fat invasion) were included in each model. The models demonstrated similar C-indices in the development set (0.790 [95% CI 0.773–0.806] for PFS and 0.793 [95% CI 0.773–0.811] for OS) and in the external validation set (0.773 [0.731–0.816] and 0.723 [0.731–0.816]). A relatively stable predictive ability of the models was observed in the development set (PFS: time-dependent AUC 0.832 at 1 year to 0.760 at 9 years; OS: 0.828 at 1 year to 0.794 at 9 years). The models were well calibrated and their predictions correlated with the observed outcome at 3, 5, and 7 years in both development and validation sets. In comparison to existing prognostic models, the present models showed superior performance, as indicated by C-indices ranging from 0.722 to 0.755 (all P<0.0001) for PFS and from 0.680 to 0.744 (all P<0.0001) for OS. The predictive accuracy of the current models was robust in patients with clear-cell and non-clear-cell RCC.

Conclusions:

Based on a prospective population-based patient cohort, the newly developed prognostic models were externally validated and outperformed the currently available models for predicting recurrence and survival in patients with non-metastatic RCC after surgery. The current models have the potential to aid in clinical trial design and facilitate clinical decision-making for both clear-cell and non-clear-cell RCC patients at varying risk of recurrence and survival.

Keywords: long-term survival, nephrectomy, prognostic model, recurrence, renal cell carcinoma

Introduction

Highlights

- Based on the currently largest prospective patient cohort including 11 000 patients with non-metastatic renal cell carcinoma (RCC) after surgery, the externally validated models incorporating routinely available clinicopathological factors:

- Showed a stable and significantly improved discriminatory ability compared with currently available models, including the recently published, yet to be widely externally validated, 2018 Leibovich and ASSURE models.

- Showed consistently good calibration in the development and external validation sets for both progression-free and overall survival.

- Maintain performance in both clear-cell and non-clear-cell RCC histologies, allowing for more flexible and generalizable clinical applications.

- They are not TNM staging dependent but include its components and other validated prognostic factors recommended by the current guideline, supporting their routine use in clinical practice.

- Are developed based on a large number of patients treated in real life outside of a clinical trial setting, which outperforms the trial-based models (e.g. ASSURE including only high-risk RCC) with limited generalizability to the general population with a higher proportion of patients with negligible risk of recurrence (e.g. pT1G1-2).

Globally, renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is the 12th most common cancer, with ~430 000 cases and 179 000 deaths per year1. The standard of care for patients with non-metastatic RCC is partial or radical nephrectomy2,3; however, over a third of patients with high-grade or locally advanced disease will relapse after surgery4. Therefore, predicting oncological outcomes such as recurrence and survival after nephrectomy is crucial for patient counseling, surveillance, determining adjuvant treatment strategies, and clinical trial design.

The commonly used prognostic models for risk stratification incorporating clinical and histological features with TNM staging were largely developed from retrospective data with small sample sizes over the last three decades and have been demonstrated to have limited ability to predict RCC outcomes when validated using contemporary prospective trial data (e.g. ASSURE)5,6. In addition, these models7–11 are restricted to a single oncological outcome and tend to be histology-focused and TNM edition dependent, limiting their long-term applicability and generalizability. External validations of available models, including those developed using the ASSURE data12, showed poor calibration, and the predictive abilities were largely overestimated and decreased over time5,13,14. These limitations of the primary prediction models used to guide the design of adjuvant RCC trials may lead to inappropriate patient selection. In addition, models will need to be recalibrated to the specific population of interest when used to determine eligibility for adjuvant therapy or surveillance protocols13. However, currently available models were developed and validated in populations of predominantly European ancestry, with no well-calibrated prognostic models existing for the non-European population with different genetic, social, and cultural backgrounds.

Therefore, we developed prognostic models to predict the risk of recurrence and survival after nephrectomy for non-metastatic RCC, accounting for all major histologies and two distinct oncologic outcomes, using a large prospective patient cohort including more than 11 000 cases of clear-cell and non-clear-cell RCC followed for 15 years. We then validated the reproducibility of the predictors and the predictive accuracy of current models in an external multicentric dataset. We also compared their predictive accuracy with other commonly used prognostic models to validate their implementation in the contemporary prospective dataset.

Methods

Participants

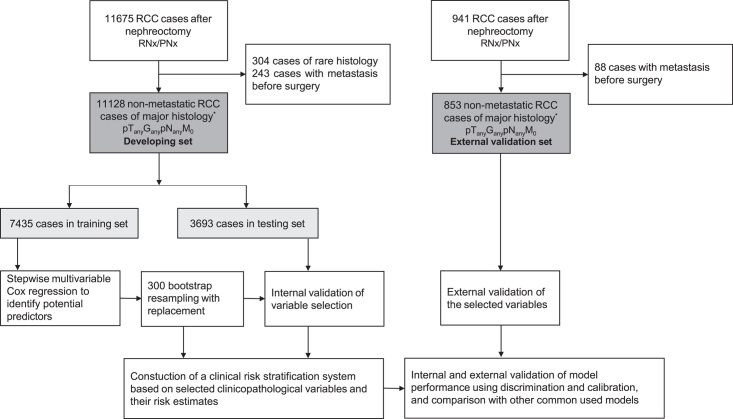

For the development set, 11 128 consecutive, prospectively identified patients treated with radical or partial nephrectomy for histologically confirmed non-metastatic RCC (clear cell, papillary, and chromophobe histology; pT(any) G(any) pN(any) M0) at a tertiary urology center in China between 2006 and 2022 were included. Baseline demographic and clinical data collected for each patient included age at surgery, sex, time of admission, surgery, and discharge, presence of symptoms at diagnosis (e.g. flank pain, abdominal mass, and hematuria), comorbidity (e.g. diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, and hypertension), smoking and drinking status, and surgical details. Histopathological features, as reviewed by a panel of genitourinary pathologists, included histologic subtype, tumor size and location, tumor staging (tumor stage, regional lymph node status, and distant metastasis) based on the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) Cancer Staging Manual, 7th Edition (2010)15, Fuhrman nuclear grade, perinephric or renal sinus fat invasion, presence of tumor necrosis, cystic change, and hemorrhage, surgical margin status, extension beyond Gerota’s fascia, and presence of tumor thrombus. Tumor staging was determined preoperatively by imaging (CT scan with contrast enhancement of the chest, abdominal cavity and pelvis, or MRI) and by histopathologic examination of a surgical specimen. Patients were followed up annually after surgery by telephone to detect early progression (confirmed by CT and MRI scans, or other imaging tests) and deliver salvage care. Death was identified by the date of death reported by the patient’s family during the telephone follow-up and was confirmed by a review of the death certificate. The current study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the tertiary urology center in China and all patients gave informed consent (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Study design.

For the external validation set, 853 retrospectively identified patients treated with radical or partial nephrectomy for histologically confirmed non-metastatic RCC (clear cell, papillary, and chromophobe histology; pT(any) G(any) pN(any) M0) between 1996 and 2013 from 13 medical centers in the USA were included. Clinicopathological data and follow-up data were downloaded from the Genomic Data Commons Data Portal based on The Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/).

Outcomes

The primary endpoint was progression-free survival (PFS), defined as the time from nephrectomy to the first documented local recurrence or distant metastases, whichever occurred first. Consistent with previous studies of RCC prediction model9,16, deaths preceding presumed progression were censored. The secondary endpoint was overall survival (OS), defined as the time from nephrectomy to death from any cause.

Statistical methods

Model development and validation were performed and reported according to the Transparent Reporting of a multivariable prediction model for Individual Prognosis or Diagnosis (TRIPOD) and Strengthening The Reporting Of Cohort Studies in Surgery (STROCSS) guidelines (Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/JS9/B392)17,18. Eligible participants in the development set were randomly split into training and internal testing sets with a 2:1 ratio. In the training set, multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression model using forward and backward selection with a significance level of 0.05 for entry and 0.01 for exit was used to identify potential predictors and estimate the hazard ratios (HRs) and their 95% CIs or P values. The case-wise deletion method was used to handle missing values in the explanatory variables. A two-step bootstrap resampling approach was used to further validate variable selection19. This approach enhances the reliability and generalizability of the model, helps identify stable predictors, and provides bias-corrected estimates to protect against overfitting during stepwise regression20. First, 300 bootstrap samples were generated randomly with replacement from the original training set (N=7435), and stepwise Cox regression was then applied to each sample using the same selection criteria. Variables that were included in more than 70% of the resulting models from the 300 bootstrap samples were considered significant and included in the final prediction models. To test the reproducibility and validity of the selected variables, the risk estimates in the training set were compared with the mean risk estimates calculated from the bootstrap samples and with those in the internal testing set (N=3693) and the external validation set (N=853). As a nonlinear association was observed with tumor size (P=0.02), tumor size was divided into four groups (≤4, 4–7, 7–10, and >10 cm) according to the 2010 AJCC pT classification.

Finally, a clinical risk stratification system was developed in the development set based on the included variables and their risk estimates in the multivariable models. All models were specifically adjusted for histology and the year of surgery to account for potential differences in clinicopathological characteristics among histologic subtypes of RCC and changes in survival over time, although these two variables were not retained in the variable selection process with bootstrap resampling. For each oncologic outcome, points were assigned to each selected variable based on the multivariable regression coefficient and were then summed to calculate the total risk score for each patient. For example, the variable with the largest estimate in the PFS model was tumor size >10 cm, estimates for the remaining variables were divided by the estimate for tumor size >10.0 cm (HR, 4.8) multiplied by five and rounded to the nearest integer. Three risk groups (low, intermediate, and high) were defined based on the degree of natural separation in the survival curves and the HRs of the risk scores. The Kaplan–Meier method was used to calculate survival rates from the date of surgery to outcomes or last follow-up, and survival curves between groups were compared using the log-rank test.

The performance of progression-free survival and OS models was evaluated by discrimination (the ability to distinguish between patients who have and have not experienced an event) and calibration (the agreement between predicted and observed outcomes)21. Discrimination was measured by the Harrell’s concordance index (C-index). As the prognostic accuracy may decrease over time, time-dependent receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves and areas under the curves (AUCs) at different years of follow-up were also generated. Calibration was assessed by calibration plots predicting the probability of progression and death at 3, 5, and 7 years versus observed probability. The clinical utility of models was evaluated by HRs between risk groups and by using the log-rank test. To assess external validity, the prediction models were applied to an independent validation set to stratify patients into low-risk, intermediate-risk, and high-risk groups with the same cutoff as that used in the development set. Model performance was then determined on the validation set by calculating global C-indices, time-dependent AUCs, and calibration plots.

To evaluate the comparative performance of RCC prediction models, the discrimination and calibration of seven commonly used and validated models [ASSURE12, GRade, Age, Nodes and Tumor (GRANT)22, Kattan et al.11, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC)10, University of California at Los Angeles Integrated Staging System [UISS]7, 2003 Leibovich9, and 2018 Leibovich (submodel for ccRCC)16] were assessed in the development and validation sets using their respective prediction outcome and then compared with the performance of the current models. For models using other editions of the TNM staging system, the 5th and 6th editions were compiled based on the detailed annotation of pathologic variables in the development set. For models that did not report cutoff points for risk groups (MSKCC and Kattan), four arbitrary groups (quartile) were generated based on the total risk scores from the nomogram and used to assess their performance.

To evaluate the performance of the current model in patients with clear-cell and non-clear-cell RCC, secondary analyses were conducted in histologic subpopulations from the development and validation sets, including clear-cell, non-clear-cell, papillary, and chromophobe histology.

All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute) and R version 4.2.2 (R Foundation), and all statistical tests were two-sided, with P<0.05 considered significant.

Results

Of 11 128 patients [median (interquartile range, IQR) age, 54 (46–62); 8054 (72%) male] with resected non-metastatic RCC included in the development set, 10 135 (91%) were diagnosed with clear-cell RCC (ccRCC), 466 (4%) had papillary RCC (papRCC), and 527 (5%) had chromophobe RCC (chrRCC). Of the 853 U.S.-based patients [median (IQR) age, 60 (51–70); 558 (65%) male] identified in the external validation set, 459 (54%) had ccRCC, 283 (33%) had papRCC, and 111 (13%) had chrRCC. Median follow-up after surgery was 4.3 years (IQR 1.7–7.8) and 2.4 years (IQR 0.9–4.9) for the development and validation sets, respectively. Median PFS and OS were not reached within the duration of follow-up in either set. Demographic and clinicopathologic characteristics of patients in the development set (including training and internal testing sets) and external validation set are summarized in Table 1. A summary of previous predictive models for PFS and OS is shown in Table S1 (Supplemental Digital Content 2, http://links.lww.com/JS9/B393) and Table S2 (Supplemental Digital Content 2, http://links.lww.com/JS9/B393).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients by the assessment set.

| Training set (n=7435) | Internal testing set (n=3693) | Developing set (n=11 128) | External validation set (n=853) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median age at surgery, years | 54 (46–62) | 54 (46–62) | 54 (46–62) | 60 (51–70) |

| Age ≥60 | 2343 (32%) | 1172 (32%) | 3515 (32%) | 434 (51%) |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 5393 (73%) | 2661 (72%) | 8054 (72%) | 558 (65%) |

| Female | 2042 (27%) | 1032 (28%) | 3074 (28%) | 295 (35%) |

| Current smoker | 1058 (14%) | 506 (14%) | 1564 (14%) | — |

| Current drinker | 975 (13%) | 465 (13%) | 1440 (13%) | — |

| Diabetes | 825 (11%) | 393 (11%) | 1218 (11%) | — |

| Cardiovascular diseases | 488 (7%) | 236 (6%) | 724 (7%) | — |

| Hypertension | 2008 (27%) | 956 (26%) | 2964 (27%) | — |

| Histology | ||||

| Clear-cell RCC | 6779 (91%) | 3356 (91%) | 10 135 (91%) | 459 (54%) |

| Papillary RCC | 316 (4%) | 150 (4%) | 466 (4%) | 283 (33%) |

| Chromophobe RCC | 340 (5%) | 187 (5%) | 527 (5%) | 111 (13%) |

| Symptoms at presentationa | 927 (12%) | 429 (12%) | 1356 (12%) | — |

| Surgical approach | ||||

| Laparoscopic radical | 3440 (46%) | 1682 (46%) | 5122 (46%) | 158 (19%) |

| Laparoscopic partial | 3649 (49%) | 1863 (50%) | 5512 (50%) | 85 (10%) |

| Open radical | 259 (3%) | 110 (3%) | 369 (3%) | 265 (31%) |

| Open partial | 64 (1%) | 33 (1%) | 97 (1%) | 122 (14%) |

| Missing | — | — | — | 223 (26%) |

| Tumor size, cm | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 3.5 (2.5–5.0) | 3.5 (2.5–5.0) | 3.5 (2.5–5.0) | 5.0 (3.3–7.5) |

| ≤4 | 4609 (62%) | 2293 (62%) | 6902 (62%) | 330 (39%) |

| >4 to ≤7 | 1780 (24%) | 886 (24%) | 2666 (24%) | 289 (34%) |

| >7 to ≤10 | 448 (6%) | 220 (6%) | 668 (6%) | 119 (14%) |

| >10 | 170 (2%) | 70 (2%) | 240 (2%) | 106 (12%) |

| Missing | 428 (6%) | 224 (6%) | 652 (6%) | 9 (1%) |

| Tumor grade | ||||

| 1 | 774 (10%) | 386 (10%) | 1160 (10%) | 14 (2%) |

| 2 | 4835 (65%) | 2343 (63%) | 7178 (65%) | 220 (26%) |

| 3 | 772 (10%) | 391 (11%) | 1163 (10%) | 175 (21%) |

| 4 | 83 (1%) | 35 (1%) | 118 (1%) | 42 (4%) |

| Missing | 971 (13%) | 538 (15%) | 1509 (14%) | 402 (47%) |

| Tumor hemorrhage | 2773 (37%) | 1382 (37%) | 4155 (37%) | — |

| Tumor necrosis | 844 (11%) | 411 (11%) | 1255 (11%) | 310 (36%) |

| Tumor cystic change | 1891 (25%) | 932 (25%) | 2823 (25%) | — |

| Perinephric or renal sinus fat invasion | 593 (8%) | 271 (7%) | 864 (8%) | 133 (16%) |

| Tumor thrombus | 383 (5%) | 198 (5%) | 581 (5%) | 67 (8%) |

| Pathologic tumor stage (pT) | ||||

| pT1 | 5720 (77%) | 2855 (77%) | 8575 (77%) | 523 (61%) |

| pT2 | 270 (4%) | 143 (4%) | 413 (4%) | 124 (15%) |

| pT3 | 660 (9%) | 311 (8%) | 971 (9%) | 200 (23%) |

| pT4 | 400 (5%) | 187 (5%) | 587 (5%) | 6 (1%) |

| Missing | 385 (5%) | 197 (5%) | 582 (5%) | — |

| Regional lymph nodes (pN) | ||||

| No nodal dissection (pNx) | 7101 (96%) | 3509 (95%) | 10 610 (95%) | 656 (77%) |

| No nodal involvement (pN0) | 288 (4%) | 158 (4%) | 446 (4%) | 152 (18%) |

| Nodal involvement (pN1) | 46 (1%) | 26 (1%) | 72 (1%) | 45 (5%) |

Data are median (IQR) or n (%).

Symptoms include flank pain, hematuria, and palpable abdominal mass.

IQR, interquartile range; RCC, renal cell carcinoma.

Progression-free survival

Six hundred thirty-three (5.7%) and 96 (11.3%) patients in the development and validation sets, respectively, experienced progression by the last follow-up. The estimated 3-year PFS was 95% (95% CI 95–96), and the estimated 5-year PFS was 93% (93–94) in the development set, while the corresponding PFS rates were 89% (87–92) at 3 years and 84% (80–87) at 5 years in the validation set.

Following the multivariable analysis and bootstrap validation in the training set, seven factors were included in the final prognostic model for PFS: sex, tumor size, Fuhrman grade, tumor necrosis, perinephric or renal sinus fat invasion, nodal involvement, and tumor thrombus (Table 2 and Table S3, Supplemental Digital Content 2, http://links.lww.com/JS9/B393). The risk estimates of these predictors from the 300 bootstrap samples were similar to those from the original model in the internal testing, development, and external validation sets, indicating good internal and external validation of variable selection (Table 2 and Table S5, Supplemental Digital Content 2, http://links.lww.com/JS9/B393). Based on the PFS model from the development set, patients were segregated into the low-risk [score 0–2; median time to PFS: 2.7 years (IQR 1.2–4.2)], intermediate-risk [3–5; 2.1 years (IQR 0.6–3.8)], and high-risk [≥6; 0.7 years (IQR 0.3–1.8)] groups (Table 4). Patients in the validation set were divided into low-risk [median time to PFS: 3.9 years (IQR 2.2–6.0)], intermediate-risk [1.9 years (IQR 0.8–4.4)], and high-risk [0.7 years (IQR 0.3–1.8)] groups using the same cutoff.

Table 2.

Multivariable association of selected variables with risk of recurrence in the developing and external validation sets.

| Training set (n=7433) | Internal testing set (n=3698) | Developing set (n=11 131) | External validation set (n=853) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P | Points | HR (95% CI) | P | |

| Sex (men vs. women) | 1.44 (1.15–1.81) | 0.0013 | 1.09 (0.83–1.48) | 0.5821 | 1.30 (1.09–1.56) | 0.0037 | 1 | 1.38 (0.87–2.20) | 0.1750 |

| Tumor size, cm | |||||||||

| ≤4 | Reference | Reference | Reference | 0 | Reference | ||||

| 4–7 | 2.48 (1.89–3.26) | <0.0001 | 2.87 (1.94–4.24) | <0.0001 | 2.64 (2.11–3.29) | <0.0001 | 3 | 2.22 (1.09–4.49) | 0.0272 |

| 7–10 | 4.26 (3.08–5.90) | <0.0001 | 3.71 (2.25–6.10) | <0.0001 | 4.11 (3.14–5.40) | <0.0001 | 4 | 1.98 (0.89–4.37) | 0.0929 |

| >10 | 4.29 (2.89–6.35) | <0.0001 | 5.94 (3.35–10.52) | <0.0001 | 4.80 (3.47–6.62) | <0.0001 | 5 | 4.34 (1.99–9.50) | 0.0002 |

| Fuhrman grade | |||||||||

| 1 | Reference | Reference | Reference | 0 | Reference | ||||

| 2 | 1.56 (0.93–2.61) | 0.0891 | 0.91 (0.52–1.62) | 0.7572 | 1.26 (0.86–1.84) | 0.2287 | 0 | 0.86 (0.11–6.60) | 0.8836 |

| 3 | 3.17 (1.84–5.47) | <0.0001 | 1.60 (0.85–3.01) | 0.1471 | 2.37 (1.58–3.56) | <0.0001 | 2 | 1.29 (0.17–9.87) | 0.8073 |

| 4 | 4.43 (2.29–8.57) | <0.0001 | 2.26 (0.92–5.53) | 0.0752 | 3.45 (2.06–5.78) | <0.0001 | 3 | 2.37 (0.29–19.60) | 0.4228 |

| Tumor necrosis (present vs. absent) | 1.76 (1.41–2.19) | <0.0001 | 2.09 (1.50–2.91) | <0.0001 | 1.85 (1.54–2.22) | <0.0001 | 2 | 1.94 (1.24–3.02) | 0.0035 |

| Perinephric or renal sinus fat invasion (present vs. absent) | 1.46 (1.13–1.89) | 0.0036 | 2.05 (1.40–3.01) | 0.0002 | 1.60 (1.30–1.98) | <0.0001 | 2 | 1.78 (1.06–2.98) | 0.0290 |

| Nodal involvement | |||||||||

| No nodal dissection | Reference | Reference | Reference | 0 | Reference | ||||

| No | 1.56 (1.16–2.11) | 0.0034 | 1.20 (0.75–1.91) | 0.4579 | 1.39 (1.08–1.78) | 0.0112 | 1 | 0.91 (0.53–1.57) | 0.7435 |

| Yes | 2.35 (1.47–3.74) | 0.0003 | 3.01 (1.55–5.84) | 0.0011 | 2.42 (1.67–3.50) | <0.0001 | 2 | 6.06 (3.30–11.14) | <0.0001 |

| Tumor thrombus (present vs. absent) | 2.41 (1.44–4.02) | 0.0008 | 1.98 (0.81–4.88) | 0.1352 | 2.28 (1.46–3.55) | 0.0003 | 2 | 1.77 (0.94–3.35) | 0.0787 |

HR, hazard ratio.

Table 4.

Concordance index, time-dependent AUC, and survival estimate of prognostic models in the developing set.

| C-index, P a | Time-dependent AUC and survival estimates (%) at different time (years) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Models and scores | N (%) | 1 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 9 |

| Progression-free survival | ||||||

| The current model | 0.790 | 0.832 | 0.804 | 0.785 | 0.770 | 0.760 |

| Low risk (0–2) | 6719 (60.4) | 100 (99–100) | 99 (98–99) | 98 (98–98) | 97 (97–98) | 97 (96–98) |

| Intermediate risk (3–5) | 2880 (25.9) | 97 (97–98) | 95 (94–96) | 93 (92–94) | 91 (90–92) | 90 (89–92) |

| High risk (≥6) | 1532 (13.7) | 87 (85–89) | 78 (76–80) | 73 (71–76) | 71 (68–74) | 71 (68–74) |

| 2003 Leibovich | 0.753, <0.0001 | 0.806 | 0.779 | 0.745 | 0.724 | 0.708 |

| Low risk (0–2) | 8667 (77.9) | 99 (99–99) | 98 (98–98) | 97 (96–97) | 96 (95–96) | 95 (95–96) |

| Intermediate risk (3–5) | 2061 (18.5) | 94 (93–95) | 88 (87–90) | 86 (84–87) | 84 (82–86) | 84 (82–86) |

| High risk (≥6) | 403 (3.6) | 73 (68–78) | 61 (55–67) | 55 (49–62) | 51 (45–59) | 51 (45–59) |

| 2018 Leibovichb | 0.722, <0.0001 | 0.761 | 0.741 | 0.721 | 0.705 | 0.695 |

| Low risk (0–5) | 9288 (83.4) | 99 (99–99) | 98 (97–98) | 96 (96–97) | 96 (95–96) | 95 (94–96) |

| Intermediate risk (6–8) | 1466 (13.2) | 92 (90–93) | 86 (84–88) | 83 (80–85) | 81 (78–83) | 80 (78–83) |

| High risk (≥9) | 377 (3.4) | 77 (73–82) | 65 (59–71) | 56 (49–63) | 51 (44–60) | 51 (44–60) |

| MSKCCc d | 0.729, <0.0001 | 0.755 | 0.734 | 0.724 | 0.716 | 0.713 |

| Low to <56 (Q1) | 2719 (24.4) | 99 (99–99) | 98 (97–98) | 97 (96–98) | 97 (96–97) | 96 (95–97) |

| 56 to <60 (Q2) | 3952 (35.5) | 99 (99–100) | 99 (98–99) | 98 (97–98) | 97 (96–98) | 97 (96–98) |

| 65 to <96 (Q3) | 1285 (11.5) | 96 (95–97) | 93 (91–95) | 91 (89–93) | 91 (89–93) | 90 (88–92) |

| 100 to high (Q4) | 3175 (28.6) | 93 (93–94) | 89 (88–91) | 86 (84–87) | 83 (82–85) | 83 (81–84) |

| Kattanc d | 0.735, <0.0001 | 0.749 | 0.745 | 0.735 | 0.724 | 0.715 |

| Low to <50 (Q1) | 2886 (25.9) | 99 (99–100) | 98 (98–99) | 98 (97–98) | 97 (96–98) | 96 (96–97) |

| 50 to <60 (Q2) | 4196 (37.7) | 99 (99–99) | 98 (98–99) | 97 (97–98) | 97 (96–98) | 96 (96–97) |

| 60 to <70 (Q3) | 1668 (15.0) | 97 (96–98) | 95 (94–96) | 92 (90–94) | 90 (88–92) | 89 (87–91) |

| 80 to high (Q4) | 2381 (21.4) | 92 (91–93) | 86 (84–87) | 82 (80–84) | 81 (79–83) | 80 (78–82) |

| Overall survival | ||||||

| The current model | 0.793 | 0.828 | 0.803 | 0.803 | 0.798 | 0.794 |

| Low risk (0–2) | 6418 (57.7) | 100 (100–100) | 99 (99–99) | 98 (98–99) | 98 (97–98) | 98 (97–98) |

| Intermediate risk (3–5) | 3415 (30.7) | 99 (99–99) | 96 (95–97) | 93 (92–94) | 91 (89–92) | 89 (88–91) |

| High risk (≥6) | 1298 (11.6) | 93 (91–94) | 81 (78–83) | 70 (67–73) | 62 (59–66) | 62 (58–66) |

| ASSURE | 0.724, <0.0001 | 0.787 | 0.732 | 0.723 | 0.725 | 0.719 |

| Low risk (0–4.5) | 4351 (39.1) | 100 (99–100) | 99 (98–99) | 98 (97–98) | 97 (97–98) | 97 (96–98) |

| Intermediate risk I (5–7) | 5927 (53.3) | 99 (99–99) | 97 (96–97) | 94 (93–95) | 92 (91–93) | 91 (90–92) |

| Intermediate risk II (7.5–9.5) | 807 (7.2) | 93 (91–95) | 81 (78–84) | 71 (67–75) | 63 (58–68) | 63 (58–68) |

| High risk (≥10) | 46 (0.4) | 66 (53–82) | 48 (34–69) | 28 (16–51) | 23 (11–47) | 23 (11–47) |

| GRANT | 0.680, <0.0001 | 0.714 | 0.690 | 0.691 | 0.683 | 0.674 |

| Low (≤1) | 9911 (89.0) | 99 (99–100) | 98 (97–98) | 96 (96–97) | 95 (94–95) | 94 (94–95) |

| High (≥2) | 1220 (11.0) | 94 (92–95) | 83 (80–85) | 72 (69–76) | 67 (63–71) | 66 (62–70) |

| UISSe | 0.744, <0.0001 | 0.794 | 0.750 | 0.749 | 0.739 | 0.728 |

| Low (T1G1–2) | 7905 (71.0) | 100 (100–100) | 99 (98–99) | 98 (97–98) | 97 (96–97) | 96 (96–97) |

| Intermediate (T1G3–4 T2Gany T3G1) | 1802 (16.2) | 98 (97–99) | 93 (92–95) | 89 (87–90) | 86 (84–88) | 85 (83–87) |

| High (T3G2–4 T4Gany) | 1424 (12.8) | 95 (94–96) | 87 (85–89) | 80 (77–82) | 75 (73–78) | 75 (72–78) |

P value show the difference between C-index for the PLA model and C-index for other commonly used models.

Three risk groups were defined based on the degree of separation in the survival curves and HR of the individual 2018 Leibovich scores.

Arbitrary categories (quartile) of scores calculated from given nomogram.

Proportion of patients in each category do not seem to be equal because of the level of precision of scores.

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (ECOG-PS) was not available in the development set.

AUC, area under the curve; GRANT, GRade, Age, Nodes and Tumor; HR, hazard ratio; MSKCC, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center; PLA, People’s Liberation Army; UISS, University of California at Los Angeles Integrated Staging System.

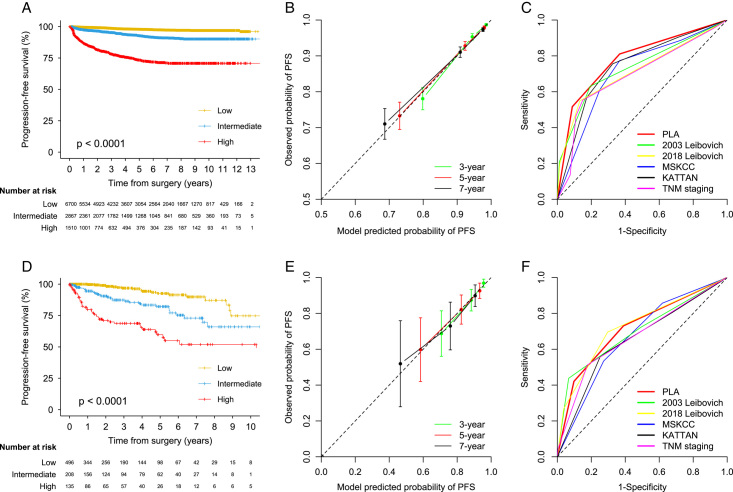

Distinct separation in the Kaplan–Meier (KM) curve by risk group was observed in the development and validation sets (Fig. 2). The global C-index was 0.790 (95% CI 0.773–0.806) in the development set, and a similar C-index was achieved in the validation set [0.773 (0.731–0.816)]. The predictive accuracy of the current model was significantly higher than those other commonly used PFS models such as 2003 Leibovich, 2018 Leibovich, MSKCC, and Kattan in the development set (C-indices ranged from 0.722 to 0.755; all P<0.0001) (Table 4). The predictive accuracy was higher than other models in the validation set (C-indices ranged from 0.722 to 0.769), while the difference was not significant for the Leibovich models (Table S7, Supplemental Digital Content 2, http://links.lww.com/JS9/B393). A stable predictive ability of the PFS model was observed in the development set (time-dependent AUC ranged from 0.832 at 1 year to 0.760 at 9 years), although a degradation of predictive ability for the current and other models was observed in the validation set (Table 4 and Table S7, Supplemental Digital Content 2, http://links.lww.com/JS9/B393). Calibration plots showed good agreement between the predicted and observed probability of PFS at 3, 5, and 7 years in the development and validation sets (Fig. 2). The estimated 1-year, 3-year, 5-year, 7-year, and 9-year survival estimates for the current and other models stratified by risk groups were calculated in the development set (Table 4) and the validation set (Table S7, Supplemental Digital Content 2, http://links.lww.com/JS9/B393). KM curve by individual PFS score is shown in Figure S1 (Supplemental Digital Content 2, http://links.lww.com/JS9/B393). HRs for PFS and P values between risk groups (low vs. intermediate, low vs. high, and intermediate vs. high) are provided in Table S8 (Supplemental Digital Content 2, http://links.lww.com/JS9/B393).

Figure 2.

Calibration, discrimination, and utility of prediction model for progression-free survival in the development and external validation sets.

Overall survival

Five hundred eighty-eight (5.3%) patients died by the last follow-up, including 369 (62.8%) who died of RCC in the development set. One hundred forty-seven (17.2%) patients died by the last follow-up in the validation set. The estimated 3-year OS was 96% (95% CI 96–97) and the estimated 5-year OS was 94% (93–94) in the development set, while the corresponding OS rates were 85% (82–88) at 3 years and 74% (70–78) at 5 years in the validation set.

Following the multivariable analysis and bootstrap validation in the training set, seven factors included in the final prognostic model for OS were age at surgery, tumor size, Fuhrman grade, tumor necrosis, perinephric or renal sinus fat invasion, nodal involvement, and tumor thrombus (Table 3 and Table S4, Supplemental Digital Content 2, http://links.lww.com/JS9/B393). The risk estimates of these predictors, except for tumor size, from the bootstrap samples were similar to those from the original model in the internal testing, development, and external validation sets, indicating good internal and external validation of variable selection (Table 3 and Table S6, Supplemental Digital Content 2, http://links.lww.com/JS9/B393). Based on the OS model from the development set, patients were segregated into the low-risk [score 0–2; median time to OS: 3.2 years (IQR 1.7–5.0)], intermediate-risk [3–5; 3.0 years (IQR 1.8–4.6)], and high-risk (≥6; 2.1 years (IQR 0.9–3.7)] groups. Patients in the validation set were classified into low-risk [median time to PFS: 3.7 years (IQR 3.2–4.6)], intermediate-risk [3.6 years (IQR 1.3–4.4)], and high-risk [2.3 years (IQR 1.2–3.6)] groups using the same cutoff.

Table 3.

Multivariable associations and scoring of selected variables with overall survival in the development and validation sets.

| Training set (n=7433) | Internal testing set (n=3698) | Developing set (n=11 131) | External validation set (n=853) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P | Points | HR (95% CI) | P | |

| Age at surgery (≥60 vs. <60) | 2.56 (2.10–3.12) | <0.0001 | 2.39 (1.80–3.17) | <0.0001 | 2.47 (2.10–2.91) | <0.0001 | 3 | 1.83 (1.27–2.62) | 0.0011 |

| Tumor size, cm | |||||||||

| ≤4 | Reference | Reference | Reference | 0 | Reference | ||||

| 4–7 | 1.80 (1.35–2.40) | <0.0001 | 1.82 (1.21–2.74) | 0.0040 | 1.85 (1.47–2.34) | <0.0001 | 2 | 1.07 (0.67–1.73) | 0.7554 |

| 7–10 | 3.25 (2.33–4.53) | <0.0001 | 3.49 (2.15–5.67) | <0.0001 | 3.37 (2.57–4.44) | <0.0001 | 3 | 0.75 (0.41–1.37) | 0.3468 |

| >10 | 3.72 (2.49–5.57) | <0.0001 | 5.95 (3.46–10.22) | <0.0001 | 4.22 (3.06–5.82) | <0.0001 | 4 | 1.48 (0.83–2.62) | 0.1807 |

| Fuhrman grade | |||||||||

| 1 | Reference | Reference | Reference | 0 | Reference | ||||

| 2 | 1.00 (0.64–1.57) | 0.9854 | 1.11 (0.60–2.05) | 0.7419 | 1.04 (0.73–1.50) | 0.8161 | 0 | 1.80 (1.12–2.92) | 0.0158 |

| 3 | 1.99 (1.22–3.24) | 0.0060 | 2.46 (1.27–4.77) | 0.0077 | 2.17 (1.47–3.22) | 0.0001 | 2 | 2.07 (1.28–3.35) | 0.0030 |

| 4 | 4.22 (2.37–7.53) | <0.0001 | 6.07 (2.66–13.81) | <0.0001 | 4.73 (2.96–7.56) | <0.0001 | 5 | 4.03 (2.26–7.22) | <0.0001 |

| Tumor necrosis (present vs. absent) | 1.98 (1.57–2.50) | <0.0001 | 1.56 (1.11–2.20) | 0.0104 | 1.86 (1.54–2.25) | <0.0001 | 2 | 1.62 (1.13–2.32) | 0.0082 |

| Perinephric or renal sinus fat invasion (present vs. absent) | 1.69 (1.29–2.21) | 0.0001 | 1.06 (0.70–1.63) | 0.7729 | 1.42 (1.13–1.77) | 0.0023 | 1 | 1.45 (0.92–2.28) | 0.1101 |

| Nodal involvement | |||||||||

| No nodal dissection | Reference | Reference | Reference | 0 | Reference | ||||

| No | 1.54 (1.12–2.12) | 0.0074 | 0.73 (0.44–1.21) | 0.2211 | 1.23 (0.94–1.60) | 0.1320 | 0 | 0.89 (0.57–1.37) | 0.5835 |

| Yes | 3.19 (2.08–4.92) | <0.0001 | 2.80 (1.43–5.47) | 0.0026 | 3.05 (2.16–4.31) | <0.0001 | 3 | 4.52 (2.62–7.79) | <0.0001 |

| Tumor thrombus (present vs. absent) | 2.15 (1.26–3.67) | 0.0048 | 4.64 (1.93–11.14) | 0.0006 | 2.63 (1.67–4.12) | <0.0001 | 3 | 2.24 (1.36–3.69) | 0.0016 |

HR, hazard ratio.

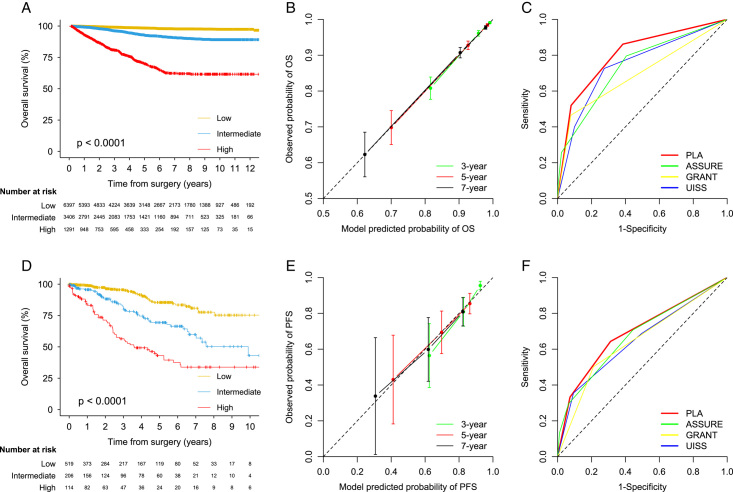

Distinct separation in the KM curve by risk group was observed in the development and validation sets (Fig. 3). The global C-index was 0.793 (95% CI 0.773–0.811) in the development set and the C-index was 0.723 (0.679–0.765) in the validation set. The predictive accuracy of the current model was significantly higher than those of other commonly used OS models, such as ASSURE, UISS, and GRANT in the development set (C-indices ranged from 0.683 to 0.741; all P<0.0001) (Table 4). The predictive accuracy was higher than other models in the validation set (C-indices ranged from 0.670 to 0.706), while the difference was not significant for the ASSURE model (Table S7, Supplemental Digital Content 2, http://links.lww.com/JS9/B393). A stable predictive ability of the OS model was observed in the development set (time-dependent AUC ranged from 0.827 at 1 year to 0.793 at 9 years), although a degradation of predictive ability for the current and other models was observed in the validation set (Table 4 and Table S7, Supplemental Digital Content 2, http://links.lww.com/JS9/B393). Calibration plots showed good agreement between predicted and observed probability of OS at 3, 5, and 7 years in the development and validation sets (Fig. 3). Estimated 1-year, 3-year, 5-year, 7-year, and 9-year survival estimates for the current and other models stratified by risk groups were calculated in the development set (Table 4) and the validation set (Table S7, Supplemental Digital Content 2, http://links.lww.com/JS9/B393). KM curve by individual OS score is shown in Figure S1 (Supplemental Digital Content 2, http://links.lww.com/JS9/B393). HRs for OS and P values between risk groups (low vs. intermediate, low vs. high, and intermediate vs. high) are provided in Table S8 (Supplemental Digital Content 2, http://links.lww.com/JS9/B393).

Figure 3.

Calibration, discrimination, and utility of prediction model for overall survival in the development and external validation sets.

Secondary analyses by RCC histology

The predictive accuracy of the current models was observed in patients with clear-cell and non-clear-cell RCC in the development and validation sets. For the PFS model, the C-indices were 0.787 for ccRCC, 0.773 for non-ccRCC, 0.736 for papRCC, and 0.815 for chrRCC in the development set (C-index 0.790), and were 0.747 for ccRCC, 0.804 for non-ccRCC, 0.834 for papRCC, and 0.723 for chrRCC in the validation set (C-index 0.773). For the OS model, the C-indices were 0.787 for ccRCC, 0.824 for non-ccRCC, 0.776 for papRCC, and 0.874 for chrRCC in the development set (C-index 0.793), and 0.706 for ccRCC, 0.723 for non-ccRCC, 0.706 for papRCC, and 0.763 for chrRCC in the validation set (C-index 0.723). The maintained clear separation between the KM curves by most risk groups of PFS and OS indicated that the discriminative ability of the current model is retained in the histologic subpopulations (Figures S2–S4, Supplemental Digital Content 2, http://links.lww.com/JS9/B393), although some overlap between low-risk and intermediate-risk groups were observed due to limited number of outcomes. On the calibration plots, the model’s predicted probabilities were close to the observed probabilities for clear-cell and any non-clear-cell RCC but deviated slightly for papillary and chromophobe RCC when lower probabilities were predicted (Figures S2 and S3, Supplemental Digital Content 2, http://links.lww.com/JS9/B393).

Discussion

In this prospective cohort and external validation study, we developed contemporary prognostic models to predict the risk of recurrence and OS in patients with non-metastatic clear-cell and non-clear-cell RCC after surgery, which had stable and significantly higher predictive ability compared with published models commonly used in adjuvant trials and excellent calibration in the largest contemporary dataset reported to date. The models demonstrated consistently higher discrimination than previous models and good calibration in an independent validation dataset, supporting their use for risk stratification in adjuvant clinical trials and to better inform patient surveillance and decision-making in clinical practice.

Widely used prognostic models for RCC were largely based on retrospective data with small sample sizes over the last three decades (time period: 1970–2003), and were demonstrated to have limited and diminishing discriminatory ability over time when validated using contemporary trial data5,6. In addition, these models7–11 were limited to a single oncologic outcome, tended to be histology-focused and dependent on a particular TNM staging edition, limiting their clinical applicability and generalizability. Current guidelines do not provide a clear preference for any specific model23. Conflicting results and reduced clinical enrichment observed in current adjuvant trials such as PROTECT24 (using the SSIGN algorithm), SORCE25, IMmotion 01026, CheckMate 91427, Keynote 56428 (using the 2003 Leibovich score), S-TRAC29, and ASSURE30 (using the UISS risk stratification system) have called into question the predictive accuracy and generalizability of these prognostic models. The subsequent 2018 Leibovich score provided only marginal improvement in discrimination for PFS in patients with ccRCC (internally validated C-index, 0.83 for 2018 score and 0.82 for 2003 score)16. The latest ASSURE models for risk stratification of patients with high-risk RCC were developed using prospective trial data12, but their performance (C-index, 0.63 for OS) was comparable with, rather than superior to, other previous models in the external validation study14. Limiting the use of ASSURE to patients who are already at high risk also leads to a complex two-stage stratification that is undesirable in real-life clinical practice. To improve survival in patients with RCC, contemporary prognostic models with validated performance are needed to improve risk stratification and the identification of high-risk patients who may benefit from adjuvant treatment such as immune checkpoint inhibitors.

The present models for PFS and OS outperform currently available prognostic models, including the recently published, yet to be widely externally validated, 2018 Leibovich and ASSURE models in several aspects. First, the current models provide stable and significantly improved discriminatory ability for PFS (C-index, 0.790) and OS (0.793) than models currently used in clinical trial design such as 2003 Leibovich (PFS, 0.753) and UISS (OS, 0.744), and recently developed models such as 2018 Leibovich (PFS, 0.722), ASSURE (OS, 0.724), and GRANT (OS, 0.680) in the development set. While 2003 Leibovich and 2018 Leibovich had comparable discriminatory ability in the validation set for PFS, these models were limited to ccRCC only or dependent on 1997 TNM staging. The current TNM stage-agnostic models maintain performance in both clear-cell and non-clear-cell RCC histology, allowing for more flexible and generalizable clinical applications. Second, the current models show consistently good calibration in the development and external validation sets for both PFS and OS outcomes. Miscalibration has been reported in external validation of previous models, such as the 2003 Leibovich31,32 and ASSURE models14, using contemporary prospective data. A well-calibrated model is essential if the derived risk groups are used to determine eligibility for adjuvant treatment or surveillance protocol. Third, the current models developed using contemporary, prospective data could be used in the general population (patients treated in real life outside of a clinical trial setting). The first-generation models were largely based on retrospective data, which are subject to measurement and ascertainment biases due to unstandardized follow-up and differences in data collection and reporting. The latest models based on prospective trial data, such as ASSURE that included patients with high-risk RCC12, are prone to selection bias due to the stringent inclusion criteria and have limited generalizability to the general population with a higher proportion of patients with negligible risk of recurrence (e.g. pT1G1-2).

The current models were based on clinicopathological factors that are routinely available, including tumor necrosis, size, grade, thrombus, nodal involvement, and perinephric or renal sinus fat invasion. These predictors are validated prognostic factors recommended by the current guidelines and consensus33,34 to be reported in routine practice and were found to be associated with the risk of recurrence and survival in previous RCC models5, especially the recent 2018 Leibovich and ASSURE models12,14. Notably, the findings that tumor thrombus and perinephric fat invasion were associated with oncologic outcomes in the current and recent models12,16, supporting components included in TNM staging23 may need to be considered independently to improve risk stratification (pT3a vein thrombus vs. pT3a perinephric/sinus fat invasion). Several other biological risk factors, such as genetic signatures35,36, have been reported to be independent predictors of recurrence after surgery and could potentially improve the predictive accuracy of RCC models36. However, genetic testing is relatively expensive and is not routinely used in clinical practice. The improvement from the inclusion of genetic variants should be offset by a significant increase in the predictive accuracy of prognostic models based on routinely available clinical information. With the evolving landscape of biomarker research, new prognostic markers with reliable and practical applications should be considered to further improve risk prediction in the clinical practice.

Advantages of the current development and validation study include the prospective data collection design that is less biased compared with retrospective urologic cohorts, the use of the currently largest general population to date with long-term follow-up and a broader risk spectrum including pT1N0 and pT2N0 tumors, and the availability of comprehensive clinicopathological data with pathology review. Several limitations of this study should be noted. The current models were developed based on a nationally representative cohort of RCC patients from China and the generalizability may be limited. However, the high performance of the developed models was consistently observed in the external validation sets including patients from 13 medical centers in the U.S. The C-indices of the model for PFS were similar between development and validation sets, which provides evidence against an overfitting of the data. The current models were at least comparable with several recently developed models such as Leibovich 2018 for PFS and ASSURE for OS in the external validation set, and the external superiority should be interpreted with caution given the limited sample size. The better performance of the current models was mainly observed in the internal set, thus the possibility of model overfitting due to variable and threshold selection should not be excluded. Future prospective validations of the current models in diverse populations with larger sample sizes are needed. Additionally, the cutoffs for risk groups were identified based on the results from the Asian population. Predictive accuracy of the model for OS was decreased when applied to the non-Asian population, but it is still higher than all currently available models for OS with validated performance. As with all predictive models, the current models will, therefore, probably need to be recalibrated when applied to the specific population of interest.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the contemporary models to predict progression-free survival and OS in patients with non-metastatic RCC after surgery were developed using a large prospective population-based patient cohort. The current models were externally validated and outperform currently available prognostic models, providing high predictive accuracy in both clear-cell and non-clear RCC. The models were based on routinely available clinicopathologic features that have been validated by previous studies and were not dependent on TNM staging, allowing for more flexible and generalizable clinical applications. Pending further prospective validation, the current models should assist in clinical trial design and clinical decision-making for patients at different risks of recurrence and survival.

Ethical approval

The current study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Chinese PLA General Hospital with registration number and all patients gave informed consent (internal registration number: S2013-065-01).

Consent

The current study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Chinese PLA General Hospital and all patients gave informed consent (internal registration number: S2013-065-01). Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

Sources of funding

Wang is funded through the Clarendon Fund Scholarship. Xie is funded through the Jardine-Oxford Graduate Scholarship and a titular Clarendon Fund Scholarship. The funding organizations had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication. We thank the TCGA for providing data.

Author contribution

Wang and Xie had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analyses. Concept and design: Y.W. and J.X.; acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: Y.W. and J.X.; drafting of the manuscript: Y.W.; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: all authors; statistical analysis: Y.W.; obtained funding: X.M; administrative, technical, or material support: B.S. and X.M; supervision: J.X. and X.M.

Conflicts of interest disclosure

No authors reported disclosures.

Research registration unique identifying number (UIN)

Not applicable (not human study).

Guarantor

Xin Ma, MD; Department of Urology, The Third Medical Centre, Chinese PLA (People’s Liberation Army) General Hospital, Beijing, China; e-mail: mxin301@126.com.

Data availability statement

Any summary data generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Provenance and peer review

Not commissioned, externally peer-reviewed.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The current study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Chinese PLA General Hospital and all patients gave informed consent. Wang is funded through the Clarendon Fund Scholarship. Xie is funded through Jardine-Oxford Graduate Scholarship and a titular Clarendon Fund Scholarship. The funding organizations had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication. We thank the TCGA for providing data.

Footnotes

Yunhe Wang, Yundong Xuan, and Binbin Su are joint first authors.

Sponsorships or competing interests that may be relevant to content are disclosed at the end of this article.

Supplemental Digital Content is available for this article. Direct URL citations are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal’s website, www.lww.com/international-journal-of-surgery.

Published online 24 November 2023

Contributor Information

Yunhe Wang, Email: yunhe.wang@ndph.ox.ac.uk.

Yundong Xuan, Email: xuanydong316@163.com.

Binbin Su, Email: subinbin@sph.pumc.edu.cn.

Yu Gao, Email: tjgaoyu@163.com.

Yang Fan, Email: kevinvan2000@163.com.

Qingbo Huang, Email: gdhuangqingbo@163.com.

Peng Zhang, Email: alwaysjumper@126.com.

Liangyou Gu, Email: guliangyouyd1@126.com.

Shaoxi Niu, Email: g4niuniu@163.com.

Donglai Shen, Email: dannyshen881015@foxmail.com.

Xiubin Li, Email: klootair@163.com.

Baojun Wang, Email: baojun40009@163.com.

Quan Zhu, Email: rosezq@csu.edu.cn.

Zhengxiao Ouyang, Email: ouyangzhengxiao@csu.edu.cn.

Junqing Xie, Email: junqing.xie@ndorms.ox.ac.uk.

Xin Ma, Email: mxin301@126.com.

References

- 1. Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2021;71:209–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ljungberg B, Albiges L, Abu-Ghanem Y, et al. European association of urology guidelines on renal cell carcinoma: the 2019 update. Eur Urol 2019;75:799–810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Powles T, Albiges L, Bex A, et al. ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline update on the use of immunotherapy in early stage and advanced renal cell carcinoma. Ann Oncol 2021;32:1511–1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Capitanio U, Montorsi F. Renal cancer. Lancet 2016;387:894–906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Correa AF, Jegede O, Haas NB, et al. Predicting renal cancer recurrence: defining limitations of existing prognostic models with prospective trial-based validation. J Clin Oncol 2019;37:2062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Usher-Smith JA, Li L, Roberts L, et al. Risk models for recurrence and survival after kidney cancer: a systematic review. BJU Int 2022;130:562–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zisman A, Pantuck AJ, Wieder J, et al. Risk group assessment and clinical outcome algorithm to predict the natural history of patients with surgically resected renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 2002;20:4559–4566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Frank I, Blute ML, Cheville JC, et al. An outcome prediction model for patients with clear cell renal cell carcinoma treated with radical nephrectomy based on tumor stage, size, grade and necrosis: the SSIGN score. J Urol 2002;168:2395–2400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Leibovich BC, Blute ML, Cheville JC, et al. Prediction of progression after radical nephrectomy for patients with clear cell renal cell carcinoma: a stratification tool for prospective clinical trials. Cancer 2003;97:1663–1671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sorbellini M, Kattan MW, Snyder ME, et al. A postoperative prognostic nomogram predicting recurrence for patients with conventional clear cell renal cell carcinoma. J Urol 2005;173:48–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kattan MW, Reuter V, Motzer RJ, et al. A postoperative prognostic nomogram for renal cell carcinoma. J Urol 2001;166:63–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Correa AF, Jegede OA, Haas NB, et al. Predicting disease recurrence, early progression, and overall survival following surgical resection for high-risk localized and locally advanced renal cell carcinoma. Eur Urol 2021;80:20–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Usher-Smith JA, Stewart GD. Predicting cancer outcomes after resection of high-risk RCC. Nat Rev Urol 2022;19:257–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Khene Z-E, Larcher A, Bernhard J-C, et al. External validation of the ASSURE model for predicting oncological outcomes after resection of high-risk renal cell carcinoma (RESCUE study: UroCCR 88). Eur Urol Open Sci 2021;33:89–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Edge SB, Byrd DR, Carducci MA, et al. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. Springer; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Leibovich BC, Lohse CM, Cheville JC, et al. Predicting oncologic outcomes in renal cell carcinoma after surgery. Eur Urol 2018;73:772–780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Moons KG, Altman DG, Reitsma JB, et al. Transparent Reporting of a multivariable prediction model for Individual Prognosis Or Diagnosis (TRIPOD): explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med 2015;162:W1–W73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mathew G, Agha R, Albrecht J, et al. STROCSS 2021: strengthening the reporting of cohort, cross-sectional and case–control studies in surgery. Int J Surg 2021;96:106165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Heng DY, Xie W, Regan MM, et al. Prognostic factors for overall survival in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma treated with vascular endothelial growth factor-targeted agents: results from a large, multicenter study. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:5794–5799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sauerbrei W, Schumacher M. A bootstrap resampling procedure for model building: application to the Cox regression model. Stat Med 1992;11:2093–2109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Harrell FE, Jr, Lee KL, Mark DB. Multivariable prognostic models: issues in developing models, evaluating assumptions and adequacy, and measuring and reducing errors. Stat Med 1996;15:361–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Buti S, Puligandla M, Bersanelli M, et al. Validation of a new prognostic model to easily predict outcome in renal cell carcinoma: the GRANT score applied to the ASSURE trial population. Ann Oncol 2017;28:2747–2753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Escudier B, Porta C, Schmidinger M, et al. Renal cell carcinoma: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol 2019;30:706–720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Motzer RJ, Haas NB, Donskov F, et al. Randomized phase III trial of adjuvant pazopanib versus placebo after nephrectomy in patients with localized or locally advanced renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 2017;35:3916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Eisen T, Frangou E, Oza B, et al. Adjuvant sorafenib for renal cell carcinoma at intermediate or high risk of relapse: results from the SORCE randomized phase III intergroup trial. J Clin Oncol 2020;38:4064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Pal SK, Uzzo R, Karam JA, et al. Adjuvant atezolizumab versus placebo for patients with renal cell carcinoma at increased risk of recurrence following resection (IMmotion010): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2022;400:1103–1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Motzer R, Russo P, Gruenwald V, et al. LBA4 . Adjuvant nivolumab plus ipilimumab (NIVO+ IPI) vs placebo (PBO) for localized renal cell carcinoma (RCC) at high risk of relapse after nephrectomy: results from the randomized, phase III CheckMate 914 trial. Ann Oncol 2022;33:S1430. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Choueiri TK, Tomczak P, Park SH, et al. Adjuvant pembrolizumab after nephrectomy in renal-cell carcinoma. New Engl J Med 2021;385:683–694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ravaud A, Motzer RJ, Pandha HS, et al. Adjuvant sunitinib in high-risk renal-cell carcinoma after nephrectomy. New Engl J Med 2016;375:2246–2254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Haas NB, Manola J, Uzzo RG, et al. Adjuvant sunitinib or sorafenib for high-risk, non-metastatic renal-cell carcinoma (ECOG-ACRIN E2805): a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2016;387:2008–2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Vasudev NS, Hutchinson M, Trainor S, et al. UK multicenter prospective evaluation of the Leibovich score in localized renal cell carcinoma: performance has altered over time. Urology 2020;136:162–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Oza B, Eisen T, Frangou E, et al. External validation of the 2003 Leibovich prognostic score in patients randomly assigned to SORCE, an international phase III trial of adjuvant sorafenib in renal cell cancer. J Clin Oncol 2022;40:1772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Escudier B, Porta C, Schmidinger M, et al. Renal cell carcinoma: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up†. Ann Oncol 2019;30:706–720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Delahunt B, Cheville JC, Martignoni G, et al. The International Society of Urological Pathology (ISUP) grading system for renal cell carcinoma and other prognostic parameters. Am J Surg Pathol 2013;37:1490–1504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Rini B, Goddard A, Knezevic D, et al. A 16-gene assay to predict recurrence after surgery in localised renal cell carcinoma: development and validation studies. Lancet Oncol 2015;16:676–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Wei J-H, Feng Z-H, Cao Y, et al. Predictive value of single-nucleotide polymorphism signature for recurrence in localised renal cell carcinoma: a retrospective analysis and multicentre validation study. Lancet Oncol 2019;20:591–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Any summary data generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.