Abstract

Objective:

The objective of this review was to critically appraise and synthesize qualitative evidence of older persons’ perceptions and experiences of community palliative care.

Introduction:

Palliative care focuses on the relief of symptoms and suffering at the end of life and is needed by approximately 56.8 million people globally each year. An increase in aging populations coupled with the desire to die at home highlights the growing demand for community palliative care. This review provides an understanding of the unique experiences and perceptions of older adults receiving community palliative care.

Inclusion criteria:

This review appraised qualitative studies examining the perceptions and experiences of older adults (65 years or older) receiving community palliative care. Eligible research designs included, but were not limited to, ethnography, grounded theory, and phenomenology.

Methods:

A search of the literature across CINAHL (EBSCOhost), MEDLINE (Ovid), Embase (Ovid SP), Web of Science Core Collection, and Scopus databases was undertaken in July 2021 and updated November 1, 2022. Included studies were published in English between 2000 and 2022. The search for unpublished studies included ProQuest Dissertations and Theses. Study selection, quality appraisal, and data extraction were performed by 2 independent reviewers. Findings from the included studies were pooled using the JBI meta-aggregation method.

Results:

Nine qualitative studies involving 98 participants were included in this review. A total of 100 findings were extracted and grouped into 14 categories. Four synthesized findings evolved from these categories: i) Older persons receiving palliative care in the community recognize that their life is changed and come to terms with their situation, redefining what is normal, appreciating life lived, and celebrating the life they still have by living one day at a time; ii) Older persons receiving palliative care in the community experience isolation and loneliness exacerbated by their detachment and withdrawal from and by others; iii) Older persons receiving palliative care in the community face major challenges managing prevailing symptoms, medication management difficulties, and costs of medical care and equipment; and iv) Older persons want to receive palliative care and to die at home; however, this requires both informal and formal supports, including continuity of care, good communication, and positive relationships with health care providers.

Conclusions:

Experiences and perceptions of community palliative care vary among older adults. These are influenced by the individual’s expectations and needs, available services, and cost. Older adults’ input into decision-making about their care is fundamental to their needs being met and is contingent on effective communication between the patient, family, and staff across services. Policy that advocates for trained palliative care staff to provide care is necessary to optimize care outcomes, while collaboration between staff and services is critical to enabling holistic care, managing symptoms, and providing compassionate care and support.

Keywords: community, older adults, palliative care, perceptions, qualitative review

ConQual Summary of Findings

| Older persons’ perceptions and experiences of community palliative care | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bibliography: Cotton A, Sayers J, Green H, Magann L, Paulik O, Sikhosana N, et al. Older persons’ perceptions and experiences of community palliative care: a systematic review of qualitative evidence. JBI Evid Synth. 2024;22(2):234-72. | |||||

| Synthesized findings | Type of research | Dependability | Credibility | ConQual score | Comments |

| Older persons receiving palliative care in the community recognize that their life is changed and come to terms with their situation, redefining what is normal, appreciating life lived, and celebrating the life they still have by living one day at a time | Qualitative | High | High | High | Dependability: 4 studies scored 5/5. Therefore, rating remains high. Credibility: 28 findings ranked unequivocal. Therefore, rating remains high, and ConQual score high. |

| Older persons receiving palliative care in the community experience isolation and loneliness exacerbated by their detachment and withdrawal from and by others | Qualitative | High | High | High | Dependability: 3 studies scored 5/5. Therefore, rating remains high. Credibility: 11 findings ranked unequivocal. Therefore, rating remains high, and ConQual score high. |

| Older persons receiving palliative care in the community face major challenges managing prevailing symptoms of breathlessness and fatigue, medication management difficulties, and costs of medical care and equipment | Qualitative | High | High | High | Dependability: 3 studies scored 5/5. Therefore, rating remains high. Credibility: 11 findings ranked unequivocal. Therefore, rating remains high, and ConQual score high. |

| Older persons want to receive palliative care and to die at home; however, this requires both informal and formal supports, including continuity of care, good communication, and positive relationships with health care providers | Qualitative | High | High | High | Dependability: 8 studies scored 5/5. Therefore, rating remains high. Credibility: 50 findings ranked unequivocal. Therefore, rating remains high, and ConQual score high. |

Introduction

Palliative care focuses on the relief of symptoms and suffering at the end of life. Although widely advocated in policy and acknowledged as a basic human right,1 the adequacy and reach of palliative care services is a universal failing.2 Global estimates suggest that approximately 56.8 million people need palliative care each year, although only 14% receive these services.3 Given that aging populations are a growing global phenomenon and people prefer to die at home, the capacity to provide community palliative care is a significant health dilemma.3

In 2020, approximately 728 million people across the world were aged 65 years or older. By 2050, this group will double to 1.5 billion, or 1 in 6 people.4 People aged 65 years or older are commonly defined as older people or older adults. Although people are generally living longer, their health status is not necessarily better than that of previous generations because of chronic conditions and associated disability.5 Chronic conditions are non-communicable diseases that, once diagnosed, continue across the life span and require ongoing management. These conditions include cardiovascular disease, cancer, diabetes, musculoskeletal conditions, and mental health conditions.6 In Australia, for example, 3 in 5 older adults (60%) have more than 1 chronic disease.6 As populations continue to age, not only does the burden of chronic disease increase, but also the complexity of care required. This is further compounded when older persons require palliative care. Evidence demonstrates that older persons have poorer access to palliative care services than younger age groups or patients with cancer.5,7,8

The World Health Organization defines palliative care as “an approach that improves the quality of life of patients (adults and children) and their families who are facing problems associated with life-threatening illness. It prevents and relieves suffering through the early identification, correct assessment and treatment of pain and other problems, whether physical, psychosocial or spiritual.”3(para.1)

As people age, their lives are influenced by broader socioeconomic changes in society, including declining birth rates and a decreased likelihood of young people living with older generations. The cumulative effects of changing sociodemographics make it challenging for national economies and health services to provide support for aging populations.5,8 At the individual level, as people age, their physical, psychosocial, and spiritual needs differ from other age groups, and these in turn may influence their palliative care needs.9 They are not merely coping with change associated with chronic disease, but are also more likely to be impacted by social isolation, diminished mobility, and changes to their socioeconomic status. These factors influence the preference of many older people to die at home and to be supported through this trajectory by community-based palliative care.7,8

Quality of life (QoL) is an important consideration for recipients of palliative care and is inextricably linked to the quality of care received. Patients receiving palliative care have identified 8 important QoL domains of importance to them: cognitive, emotional, health care, personal autonomy, physical, preparatory, social, and spiritual.10 Enabling older persons to receive palliative care in their home and to address their diverse and complex needs necessitates collaboration across palliative, geriatric, and primary care specialties.8 Fundamental to the provision of this care are primary health care professionals with effective care coordination and communication skills, and the capacity to incorporate advance care planning in supporting patient goals.11 Where coordinated care is provided, hospitalization is less likely, health care costs are lower, and, importantly, it is less likely that death occurs in hospital.12 Additionally, patient and family satisfaction with care is increased; patients feel less isolated; and families are more supported to continue care at home.12,13 These factors reinforce the need for community palliative care services to be available and accessible to older persons dying at home.8 For the purposes of this review, we have defined community palliative care as care provided by health care workers to older persons living in their home, a community living environment, or a retirement village.

Systematic and integrative reviews to date have focused on health professionals’ perspectives on community palliative care for patients with dementia14; older persons’ perceptions of their health, ill health, and community care needs15; and exploring an integrated palliative care model for older persons.16 Other systematic reviews have focused on the carer’s role in palliative care,17 experiences of caregivers of older adults with advanced cancers,18 family caregivers’ pain management in end-of-life care,19 burnout syndrome in informal caregivers of older adults with dementia,20 and nursing interventions to support family caregivers in end-of-life care at home.21

As noted in the study protocol22 and supported by current searches of CINAHL, MEDLINE, the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, and JBI Evidence Synthesis, no systematic reviews of older persons’ perceptions and experiences of community palliative care were identified. Indeed, there is a dearth of research on community-based palliative care for older persons in general, and on the experiences and perceptions of older persons receiving community palliative care in particular.

Hence, there is an urgent need to address the gap in the research literature through a systematic review to enhance understanding of the unique experiences of older adults and their perceptions of receiving palliative care in the community, including the challenges, benefits, barriers, and facilitators encountered while receiving community palliative care. This systematic review aimed to critically appraise and synthesize qualitative evidence of older persons’ perceptions and experiences of community palliative care. The findings of this review may contribute to an evidence base to inform providers of community-based palliative care, policymakers, and health professionals regarding the provision of high-quality, community palliative care for older persons. It also identified opportunities for future research.

Review question

What are older persons’ perceptions and experiences of community palliative care?

Inclusion criteria

Participants

This review included studies of participants who had received community palliative care services. Studies were eligible if the mean age of participants was 65 years or older. If a study provided information regarding an individual participant’s age, only participants who were 65 years or older and their data were included in this review. Studies were also eligible for inclusion if the researchers identified participants as older persons.

Phenomena of interest

The phenomena of interest were the experiences and perceptions of older persons who had received community palliative care.

Context

The review considered studies undertaken in older persons’ homes, a community living environment, or a retirement village. Studies conducted in nursing homes and residential aged care facilities were excluded.

Types of studies

The review included qualitative studies that explored older persons’ perceptions and experiences of community palliative care. Research designs included, but were not limited to, ethnography, grounded theory, and phenomenology.

Methods

This systematic review followed the JBI methodology for systematic reviews of qualitative evidence and used a mega-aggregative approach to the synthesis of evidence.23,24 This review was conducted in accordance with an a priori protocol.22

Modifications to the a priori protocol

This review was conducted with the following modifications to the a priori protocol22:

MEDLINE (Ovid) was searched instead of PubMed due to accessibility.

The JBI System for the Unified Management, Assessment and Review of Information (JBI SUMARI; JBI, Adelaide, Australia) standardized data extraction tool23 was used in this review, updated from the JBI QARI data extraction tool cited in the protocol.22

The review extended the inclusion criteria from studies with adults who were 65 years or older to studies where the mean age of participants who experienced palliative care in the community was 65 years or older, and where the authors of the studies identified the participants as older persons or older adults who experienced community-based palliative care.

Only ProQuest Dissertations and Theses was searched for unpublished studies, as this database was deemed sufficient to identify the available gray literature.

Search strategy

A 3-step search strategy was used in this review. The initial search for published and unpublished studies was conducted in July 2021 and updated November 1, 2022. First, a preliminary search of the CINAHL and MEDLINE databases was undertaken, followed by an analysis of the text words contained in the title and abstract and the index terms used to describe the studies. A second search including all identified keywords and index terms was completed across the specified databases. The full search strategies are provided in Appendix I. Given the recent emergence of palliative care as specialist practice, only studies published from 2000 onward and in English were considered for inclusion.

The databases searched included CINAHL via EBSCOhost, MEDLINE via Ovid, Embase via Ovid SP, Web of Science Core Collection, and Scopus. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses was used to search for unpublished studies. The reference lists of studies included in the full-text review were also screened for additional studies.

Study selection

Following the search, all identified citations were collated and uploaded into EndNote v.18 (Clarivate Analytics, PA, USA). Duplicates were then removed. Following a pilot test, 2 independent reviewers screened the titles and abstracts to identify records eligible for inclusion in the review. Potentially relevant studies were retrieved in full, and their citation details were imported into JBI SUMARI. Full-text studies were excluded if they did not meet the inclusion criteria, and a list of studies with reasons for their exclusion is provided in Appendix II. Any disagreements between the reviewers were resolved through discussion or with a third reviewer.

Assessment of methodological quality

Using the JBI critical appraisal tool,23 a methodological quality assessment for each study was conducted by 2 independent authors (AC and JS) and checked by a third reviewer (JF). Each criterion was given a score (yes = 2, unclear = 1, no = 0), giving a possible maximum score of 20 for each study. Disagreements that arose between the reviewers were resolved through discussion and consultation with all reviewers involved in the study. All papers, irrespective of the quality, were included.

Data extraction

Data were extracted from the papers in the review by 2 independent reviewers using standardized data extraction tool in JBI SUMARI.23 The data extracted included specific details about the phenomena of interest, populations, study methods, and outcomes of significance to the review question and objectives. The relevant findings from the included papers were extracted verbatim with the inclusion of a participant quote to support and demonstrate the meaning of the results. As the focus was solely on older persons, only data that represented older persons’ voices were included. The findings were rated according to JBI levels of credibility,23 as unequivocal, credible, or not supported.

Data synthesis

Qualitative research findings were pooled using methods outlined in the JBI approach for qualitative systematic reviews.24 This involved the aggregation and synthesis of findings to generate a set of statements that represent that aggregation by assembling the findings (level 1 findings), rating findings according to their quality, and categorizing these findings on the basis of similarity in meaning (level 2 findings). These categories were then subjected to a meta-synthesis to produce a comprehensive set of synthesized findings (level 3 findings) that could be used as a basis for evidence-based practice.24

Assessing confidence in the findings

Each synthesized finding was rated on dependability and credibility using the ConQual approach.25 The ConQual approach for qualitative systematic reviews allows synthesized findings to be downgraded based on their dependability and credibility. Qualitative studies are initially ranked as high, and from this starting point, each study is then graded for dependability and credibility. The Summary of Findings compiles the ConQual score for each synthesized finding, and from this, a rating of confidence in the synthesized findings can be considered. Therefore, it serves as a practical tool to assist in decision-making.25

Results

Study inclusion

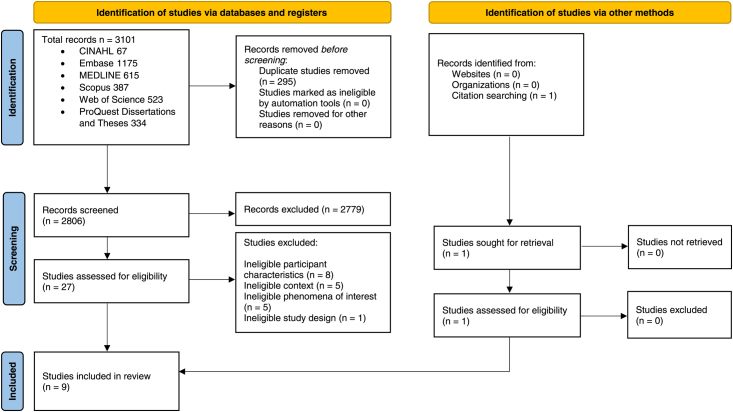

The literature search identified 3101 papers. These were imported into EndNote v.X9 bibliographic software and 295 duplicates were removed. The titles and abstracts of the remaining 2806 papers were screened and 2779 were excluded, as they failed to meet the eligibility criteria. Twenty-seven full-text studies were retrieved. One additional study was identified from citation searching and retrieved. Following the assessment of the 28 studies, 19 of these were excluded as they failed to meet the inclusion criteria. The 9 remaining studies were critically appraised. See the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram26 (Figure 1) depicting the search results and study selection and inclusion process.

Figure 1.

Search results and study selection and inclusion process.26

Methodological quality

Nine studies were critically appraised (Table 1). All studies demonstrated congruity between the research methodology and the stated philosophical perspective, research question, methods used to collect data, representation and analysis of data, and interpretation of results (Q1, Q2, Q3, Q4, and Q5). All studies included a statement locating the researcher culturally or theoretically (Q6) and addressed the influence of the researcher on the research or vice versa (Q7). Participants’ voices were represented in 6 studies (Q8). Additionally, the reviewers found that the research was ethical according to current criteria, or there was evidence of ethical approval (Q9). All studies had conclusions drawn in the research report flow from the analysis, or interpretation, of the data (Q10). There were no disagreements between the reviewers regarding the critical appraisal.

Table 1.

Critical appraisal of eligible qualitative studies

| Study | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | Q7 | Q8 | Q9 | Q10 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Culjis 201335 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 20 |

| Duggelby et al. 201029 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | 18 |

| Fjose et al. 201828 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 20 |

| Jack et al. 201631 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 20 |

| Jo et al. 200727 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 20 |

| Kaasalainen et al. 201133 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | 18 |

| Kokorelias 201634 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 20 |

| Law 200930 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | Y | Y | 19 |

| McWilliam et al. 200832 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 20 |

Y, yes (2 points); N, no (0 points); U, unclear (1 point).

JBI critical appraisal checklist for qualitative research.

Q1 = Is there congruity between the stated philosophical perspective and the research methodology?

Q2 = Is there congruity between the research methodology and the research question or objectives?

Q3 = Is there congruity between the research methodology and the methods used to collect data?

Q4 = Is there congruity between the research methodology and the representation and analysis of data?

Q5 = Is there congruity between the research methodology and the interpretation of results?

Q6 = Is there a statement locating the researcher culturally or theoretically.

Q7 = Is the influence of the researcher on the research, and vice-versa, addressed?

Q8 = Are participants, and their voices, adequately represented?

Q9 = Is the research ethical according to current criteria or, for recent studies, is there evidence of ethical approval by an appropriate body?

Q10 = Do the conclusions drawn in the research report flow from the analysis, or interpretation, of the data?

Characteristics of the included studies

Nine qualitative studies published between 2007 and 2018 were included in the review.27–35 There was a total of 98 older adult participants. The majority of studies focused on community palliative care for older persons diagnosed with cancer.27–32 Two studies focused on community palliative care for older adults with advanced heart failure.33,35 One study researched the experiences of older adults with dementia receiving community-based palliative care.34 Research designs included qualitative descriptive,27,28,31,33 interpretive qualitative,35 ethnographic,32 grounded theory,29,30 and phenomenology.34 Four countries were represented in the review: Canada,27,29,32–34 Norway,28 the United Kingdom,30,31 and the United States.35 Study settings were participants’ homes. Eight of the 9 studies were conducted in cities, while 1 was undertaken in a rural area.29 Characteristics of included studies are presented in Appendix III.

Review findings

The meta-synthesis of included studies for this review generated 4 synthesized findings that were developed from 14 categories and 100 findings (all rated unequivocal), extracted from the 9 included studies. This section presents the synthesized findings and their included categories (see Tables 2 through 5), with a summary of each of the categories supported with key illustrations to allow the voices of the older persons who experienced palliative care in the community to be heard. Appendix IV presents details of the findings and illustrations from each study.

Table 2.

Synthesized finding 1

| Findings | Categories | Synthesized finding |

|---|---|---|

| Transitions disrupted the lives of palliative patients and their families … experienced feeling out of control (U) | Recognizing their life had changed | Older persons receiving palliative care in the community recognize that their life is changed and come to terms with their situation, redefining what is normal, appreciating life lived, and celebrating the life they still have by living one day at a time. |

| Transition or turning point in which men recognize their life was changed at some point, not always immediately by the diagnosis (U) | ||

| Older men more than younger older men found it difficult to recall the exact onset of the illness (U) | ||

| Recognizing but simultaneously resenting their illness … begrudging the passing of their lives (U) | ||

| “Dying while living” was repeatedly emphasized (U) | ||

| Older participants acknowledged that they were dying (U) | ||

| One of the biggest changes … was the experience of becoming home-bound (U) | ||

| Coming to terms with their situation was the first process for palliative patients (U) | Coming to terms with their situation | |

| The meaning of HF during this turning point was primarily focused on their ability to retain independence (U) | ||

| Disease and its treatment continuously notified the senior that his/her “self” was mortified (U) | ||

| Increasingly reminded of … the loss of their mortal self, they reflected (U) | ||

| Once they came to terms with the fact that their conditions were incurable and a palliative care plan was in place, they were able to better accept the care provided to them by health care professionals (U) | ||

| Hoped to be better prepared for the discussions about transitioning to palliative care (U) | ||

| Moved beyond equating their lives to mortal being and spoke positively about their “life after life” (U) | ||

| Palliative patients and their families changed what they considered to be normal (U) | Redefining what is normal | |

| Failure to materialize “normal” everyday life activities … brought the experience of “dying while living” (U) | ||

| They defined new standards of what was “well” (U) | ||

| Within their medicalized in-home palliative care context…they explained their effort to “hold on” to normal physical and social life, despite their sick role (U) | ||

| Focused on retaining one’s physical being as long as possible (U) | ||

| In ‘living while dying,’ the participants … placed high value on interpersonal relationships … normalizing relationships through social reciprocity (U) | ||

| In the process of redefining normal maintaining their personhood—who they were—was very important (U) | ||

| Reflective moments about their life and overall satisfaction about their lives in general (U) | Appreciating life lived and celebrating life they still had by living one day at a time | |

| The sense of time had become less significant (U) | ||

| Conveyed full appreciation … in having the opportunity for more life (U) | ||

| Appreciation of the opportunity to have time to prepare for their death (U) | ||

| Celebrated the life they still had by living one day at a time (U) | ||

| Valuing time for one’s mortal being and enacting that through everyday experiences (U) | ||

| Lived every day as though it might be the last, focusing on making it a positive and purposeful time (U) |

U, unequivocal; HF, heart failure.

Synthesized finding 1: Older persons receiving palliative care in the community recognize that their life is changed and come to terms with their situation, redefining what is normal, appreciating life lived, and celebrating the life they still have by living one day at a time

This first synthesized finding articulates older persons’ feelings and emotions about their life situation, the coping mechanisms they adopt, and their reflections on their life. They expressed their perceptions and experiences of community-based palliative care against the backdrop of the passage of time during their journey through different phases and turning points of community-based palliative care. For most older persons, initial recognition that their life had irrevocably changed occurred after receiving clarification of their diagnosis and the incurable nature of their illness, and the need for palliative care, which could be provided in their own home. Older persons perceived the need to come to terms with their situation as they simultaneously noted that their capacity to be independent and their ability to do the things they had previously done every day with ease was diminishing. As part of this process, they redefined their “new normal” to maintain their personhood. During these transitions, they celebrated the life they still had by living one day at a time and reflecting on their lives thus far. This synthesized finding is underpinned by 4 categories that were generated from 28 findings (see Table 2).

Category 1.1: Recognizing their life had changed

For some older persons, recognition that their life was irrevocably changed occurred at or after receiving their initial diagnosis, prognosis, and community-based palliative care plan from medical and palliative care providers. The recognition that they were dying and that the treatment available to them would be palliative rather than curative resulted in feelings of being out of control, surprised, angry, resentful, or helpless. One participant railed against being “sentenced to death” after receiving the prognosis from their doctor that they would die in 6 months.32(p.342) For some older persons, subtle changes in their levels of daily function; an event such as sudden hospitalization for another illness; or participation in sport, exercise, or holiday activities before the diagnosis of their illness heralded the awareness that their life had changed.35 One change experienced by some participants receiving palliative care in their own home was being homebound. For others, recognizing that their life had changed was a process of accepting and receiving community-based palliative care, supported by the hope of living many more years receiving palliative care in their own home. This category was supported by 7 findings.

…everything I guess was out of control. 29(p.4)

I was trying to climb (hiking) and I didn’t make it. I sat down and rested, when I got down, I went and saw my doctor and he turned around and sent me to a cardiologist … and he put me in the hospital (received valve replacement, beginning of [heart failure]. 35 (p.61)

we’re both stuck at home. 34(p.56)

Well it means I am dying and there is nothing nobody can do to stop it … And I’m okay with that. So with palliative care I can … I can feel I can stay like this for years … here at home.34 (p.55)

Category 1.2: Coming to terms with their situation

Older community-based, palliative care patients acknowledged that sooner or later they had to come to terms with their situation. They expressed anger and resentment at the diagnosis that they were dying and that palliative care would probably extend the time waiting for death. The necessity of coming to terms with their situation was made apparent by their decreasing capacity to undertake their usual activities and the need for formal supports to manage their illness. Once they accepted that they were dying and they were willing and able to receive palliative care in their own home, patients were able to appreciate and accept the formal support from health care providers. This category was supported by 7 findings.

…you have to come to terms, you know…with the change. 29(p.4)

You know, I need to get out or it is going to kill me…I’m dying slowly. I can feel it, not because of the cancer, but because of not being mobile, you know.” 32 (p.342)

And I like to be in control, but other than that, you know what, the services that I get at my house, I can’t complain. It, it is wonderful. And they seem to go out of their way and they seem to be caring and professional. I know I need them because I am dying and it’s palliative. And they are quite helpful, so to be honest with you. I have no complaints … for this situation because I can’t do it for myself anymore. 34 (p.55)

Category 1.3: Redefining what is normal

There was a gradual or sudden change in the perceptions of what was normal among older persons receiving palliative care. Regardless of whether the change was gradual or sudden, they had to identify what their new normal would look like. Sometimes this meant trying to lead as “normal” a life as possible, doing what they typically did (within the context of receiving palliative care), such as maintaining their usual physical or social activities despite their designated sick role. However, the inability to undertake usual, everyday activities necessitated redefining a new normal for the patient who was dying, while also still living and receiving palliative care. Amidst redefining normal in their world, the older person receiving community palliative care experienced that their personhood had not changed. This category was supported by 7 findings.

… like we said, you know, redefining everything in your world. 29(p.5)

I’m feeling well … normal … Yes, normal for being sick.29(p.5)

… because when you’re sick like everybody says … I’m still me you know … I don’t change. I deal with the changes by being me. 29(p.5)

Category 1.4: Appreciating life lived and celebrating the life they still had by living one day at a time

Older persons receiving community-based palliative care reflected upon and appreciated the life they had lived and had previously taken for granted. They celebrated the life they still had by living each day as though it were their last, living fully in the present, and focusing on making the day purposeful and positive. This category was supported by 7 findings.

[Life at present] means getting up in the morning and realizing I’m not dead! Saying, “Oh boy I’ve got a whole day of interesting stuff to do.” 32 (p.342)

I mean, we are all dying, [I’m] only somebody who is predetermined a little bit earlier … I’m glad I know [that I am dying]. I feel like I can get everything ready. 32 (p.344)

What matters is right now, this moment, this life.32(p.345)

Synthesized finding 2: Older persons receiving palliative care in the community experience isolation and loneliness exacerbated by their detachment and withdrawal from and by others

Older persons receiving palliative care in the community experienced isolation and loneliness as they became homebound and marginalized due to their increasing inability and desire to participate in everyday activities and usual social interactions. Dying was experienced as an intense, existential experience of isolation and loneliness. This was exacerbated by increasing social isolation as the dying person detached from others, and, similarly, others initiated detachment and withdrawal from the person and their dying world. This synthesized finding is underpinned by 2 categories generated from 11 findings (see Table 3). A summary of the categories and examples of supporting illustrations are presented here.

Table 3.

Synthesized finding 2

| Findings | Categories | Synthesized finding |

|---|---|---|

| Feelings of isolation (U) | Isolation and loneliness | Older persons receiving palliative care in the community experience isolation and loneliness exacerbated by their detachment and withdrawal from and by others. |

| Dying patients could experience feelings of isolation (U) | ||

| Falling outside the margins of everyday life meant that dying was experienced as an isolated inhuman experience (U) | ||

| Intense existential intrapersonal isolation and aloneness … to be part of confronting death (U) | ||

| Returning home meant returning to … lonely, dying world (U) | ||

| Social isolation from other individuals as a function of … conflicted feelings (U) | ||

| Being unable to participate in everyday life activities left study participants feeling marginalized (U) | ||

| Handed over their personal roles to those who would outlive them (U) | Detaching and withdrawing | |

| Detaching and withdrawing from others (U) | ||

| Detaching sometimes was extended to extended to their palliative care nurses (U) | ||

| Significant others initiated the detachment, marginalizing the dying individual (U) |

U, unequivocal.

Category 2.1: Isolation and loneliness

Older persons receiving community-based palliative care experienced feelings of isolation and loneliness. They felt increasingly marginalized by their social isolation and physical decline. They experienced dying as an isolated, inhuman experience of being alone and lonely in their dying world. Some expressed an ambivalence about wanting to be alone and yet also not wanting to be alone. This category was supported by 7 findings.

But as you get older you become more lonely … You haven’t as many friends because they’re gone. 27(p.15)

You feel OK while you’re walking around the hospital grounds and suddenly you go in the car to come back and, oh, you feel you’re absolutely on your own. 30 (p.2635)

A lot of things aren’t important to me anymore. I particularly do not want to see a lot of people. I want to be alone, but then, I do not want to be alone. 32 (p.344)

…so I guess, in that way, I suppose you’re isolated a bit. 29(p.3)

Category 2.2: Detaching and withdrawing

Not being able to do as much as they once could and not necessarily wanting to engage with others left some older persons feeling marginalized. They coped with this by detaching and withdrawing from others, including their palliative care nurses. Detachment and withdrawal by others from the older person receiving community-based palliative care were experienced as a hurtful abandonment from those whom they had believed to be their supportive family and friends. This category is supported by 4 findings.

You know … two of my best friends … I absolutely love them, and when I told her [that I was dying], she said, “I cannot deal with it,” and she never phoned me … It really hurts when you care for people and then they drop you. 32 (p.344)

I … know how other people feel now to come and see me. I don’t want them to come and see me anyway. 32(p.344)

Synthesized finding 3: Older persons receiving palliative care in the community face major challenges managing prevailing symptoms, medication management difficulties, and costs of medical care and equipment

Older persons receiving palliative care in the community faced challenges of identifying and managing prevailing symptoms, such as breathlessness and fatigue, given that these symptoms may also be associated with their chronic illnesses. Due to their inability to identify the frequency and severity of the prevailing symptoms, they found it difficult to judge when they should call for emergency assistance from health providers. Older persons receiving palliative care at home found difficulties in managing medications and dealing with the high costs of medical care and equipment. This synthesized finding is underpinned by 3 categories that were generated from 11 findings (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Synthesized finding 3

| Findings | Categories | Synthesized finding |

|---|---|---|

| Challenge of managing prevailing symptoms (U) | Challenge of managing prevailing symptoms of breathlessness and fatigue | Older persons receiving palliative care in the community face major challenges managing prevailing symptoms, medication management difficulties, and costs of medical care and equipment. |

| Not able to determine the frequency, severity or how much a symptom bothered them (U) | ||

| Breathlessness and fatigue are also associated with other chronic illnesses making differentiation of symptoms difficult if not impossible (U) | ||

| How men manage increasing breathlessness (U) | ||

| Inability to judge when to call the health care providers (U) | ||

| In spite of frequent hospitalizations and a limited quality of life, allowing for a natural death is unthinkable in the presence of breathlessness (U) | ||

| Regardless of the availability of medications and equipment to support management of breathlessness at home, men found it difficult to do what they considered “nothing” (U) | ||

| Medication management is left to the men to order, organize and take at the correct times. Medication difficulties abound (U) | Medication management difficulties | |

| As a man becomes more impaired by fatigue and breathlessness, the caregiver, family member or the nurse from the palliative care team begins to fill medication boxes (U) | ||

| Difficulties in dealing with the high costs of medical equipment (U) | Difficulties with cost of medical care and equipment | |

| Delays in calling 911 … A 911 call resulted in costs which caused them to rethink when to call for assistance (U) |

U, unequivocal.

Category 3.1: Challenge of managing prevailing symptoms of breathlessness and fatigue

Older persons receiving community-based palliative care had multiple chronic illnesses, making it difficult for them to identify the frequency and severity of prevailing symptoms, such as breathlessness, fatigue, and limited physical ability. Management of breathlessness was a major challenge, as it brought into focus that their death may be imminent. This category is supported by 7 findings.

I’ve had everything — you name it. I’ve had lots of angina, lots of bloating— that’s one of the reasons that I’m on dialysis … I’ve been in the hospital at least 10 times … I’ve had 3 heart attacks, I have a pacemaker, defibrillator, and now I have kidney failure. I’m a diabetic … so I’ve had every symptom you can think of … I take [nitro spray] to bed with me because during the night I get so flustered. 33 (p.49)

Bouncing around symptoms between fatigue, breathlessness and limited physical ability. 35(p.65)

I usually come in here and sit down and rest. And when it (breathlessness) quiets down a little bit, I come in here and take a nap. Let my heart rest … happens just about every day.35 (p.71)

When I have difficulty breathing … Yeah that’s really difficult to put up with because you imagine all sorts of things. I am not afraid of dying, I am not afraid of dying, every body’s got to do it, but when it approaches you that close where you can’t catch your breath, no matter what you say about dying, it gives you a creepy feeling. Sometimes I wake her up, I say wake up come on wake up stay out here with me.35 (p.86)

Category 3.2: Medication management difficulties

Older persons receiving community-based palliative care faced major difficulties with managing their medications, which may have been exacerbated by their increasing breathlessness, fatigue, and limited mobility. When they reached a point where they were unable to manage their medications, family or health providers were required to take over the management of their medications. This category was supported by 2 findings.

So I got to get somebody like a nurse to order them for me or I won’t get them and that’s alright too because I’m tired of taking pills anyway. 35 (p.77)

Well, I can’t do things for myself much. Like I can’t even take my pills. My wife has to hand them to me. It’s not because I can’t. It’s just to make sure I don’t forget … Dementia makes it hard for me to know. 34 (p.65)

Well I take them in 3 doses, like 15 in the morning, 5 at noon, then the balance at dinner, then he (son) was pretty abrupt. I missed a couple of days and he (son) came around and said you miss your pills you die, just like that. 35 (p.76)

Category 3.3: Difficulties with cost of medical care and equipment

The cost of receiving and accessing medical care and the use of medical equipment in the community-based palliative care setting was prohibitive. This may lead the older person to delay or avoid accessing medical care even in an emergency. This category was supported by 2 findings.

So what I am thinking about doing the next time when I think I am in trouble. I’m going to pretend I’m not and I’m not going to call them [911]. Because I found that they go to Community Hospital and I can go there by cab. By the condition of what would be anywhere from $14 to $18 cab fare to go to the same place. Or it could be thousands of dollars if you call 911.35(p.74)

the cost of being sick is enough to make you sick, it’s the cost of getting well [that] is almost prohibitive. 27(p.14)

Synthesized finding 4: Older persons want to receive palliative care and to die at home; however, this requires both informal and formal supports, including continuity of care, good communication, and positive relationships with health care providers

Older persons receiving community palliative care wanted to receive it in their own home. They wanted to die at home where they felt they belonged, surrounded by their loved ones in their familiar surroundings, not in a hospital or care facility surrounded by strangers. To enable older persons to receive palliative care and die in their own home, however, requires both informal and formal supports, including continuity of care and good communication and relationships with health care providers. This synthesized finding is underpinned by 5 categories that were generated from 50 findings (see Table 5).

Table 5.

Synthesized finding 4

| Findings | Categories | Synthesized finding |

|---|---|---|

| Home as the place where they “belong” … key goal, in terms of care, was for them to be able to stay in their homes for as long as possible (U) | Home was the preferred place of older persons to receive palliative care and to die | Older persons want to receive palliative care and to die at home; however, this requires both informal and formal supports, including continuity of care, good communication, and positive relationships with health care providers. |

| Fearful that their diagnosis would progress to the point, where the services provided … would not be enough for them to continue to receive all their care at home (U) | ||

| Compared their experiences to that of being in a hospital surrounded by strangers (U) | ||

| Rather die sooner than receive care in a hospital (U) | ||

| Being less fearful of death now that they are receiving palliative care services in their home (U) | ||

| Receiving palliative care services at home allowed them to be surrounded by those they recognize and love … provided them with a greater sense of safety and comfort (U) | ||

| Spending some of their final days at home seemed to prompt familiar and important memories (U) | ||

| The familiar environment of their home also allowed the older adults to be independent (U) | ||

| Being surrounded by their family members was key to defining why the home was the preferred place of the older adults to receive palliative care … and remaining at home was so important (U) | ||

| Negative perspectives regarding the presence of informal supports during the caregiving experience (U) | Informal support | |

| Frustration over lack of face-to-face support from her children (U) | ||

| Too much support (U) | ||

| Informal supports had a positive influence on their lives (U) | ||

| They had friends, family, and neighbours that they could call upon, even if they did not require it (U) | ||

| Wanted their family members to provide the majority of their care (U) | ||

| More dependent on “family” outside the home … increasing reliance on friends and neighbors (U) | ||

| Caregiving experience had brought them closer to their spouses (U) | ||

| Focused effort to “connect” … they gave care to their loved ones (U) | ||

| Communication … an important constituent of the caregiver–care recipient relationship (U) | ||

| Concerned about how the work of caregiving was having a negative toll on their spouses (U) | ||

| Recognized the importance of informal supports for their caregivers (U) | ||

| Reached out to their loved ones, reassuring them of their potential to transcend mortality (U) | ||

| Prepared their loved ones for being on their own (U) | ||

| Effectiveness of their caregiver in providing care for them (U) | ||

| Most families found the health services to be fragmented … Lack of continuity … left little room for patients and family members to receive answers to their questions (U) | Continuity of care | |

| The service that they had received was not well coordinated and continuous (U) | ||

| The families did not want HCNs to always send new people to their homes. It was particularly difficult for patients to receive care from strangers, who did not know their needs, and this meant unpredictability concerning how help would be given (U) | ||

| Appreciation for continuity in the relationships with palliative care nurses (U) | ||

| Continuous care by the same individual(s) was acknowledged by care recipients to be a positive aspect of formal supports (U) | ||

| The cancer nurse was the same over time and an important resource for the families. She communicated information and helped families navigate the health care system (U) | ||

| Lack of communication between the care recipients and health providers was … a major problem (U) | Communication and relationships with health care providers | |

| Communication with their health care providers was important (U) | ||

| Health care providers were perceived as providing uncertainty in how to proceed with care (U) | ||

| Some families thus blamed the GP for the patient’s poor prognosis (U) | ||

| Families expressed low confidence in the GP’s competence (U) | ||

| Many patients did not wish to, or were unable to, maintain contact with the health services and handle the information regarding their own health situation (U) | ||

| More or less completely delegated that responsibility to their family members (U) | ||

| It seemed easier for the patient to delegate and for family members to take over when a spouse or family member had health service training (U) | ||

| Experiences of being connected with their nurses were in keeping with their sick role (U) | ||

| The nurses were insensitive (U) | ||

| Patient and caregiver psychological well-being is improved through having a good relationship with nurses (U) | ||

| Nurses can, holistically, understand an individual’s situation which ensures that the patient’s needs and wishes remains central (U) | ||

| Lack of information and poor communication with health care providers (U) | ||

| Service workers were not aware of what other service workers had done (U) | ||

| All care recipients acknowledged how helpful and supportive formal services have been (U) | Formal support | |

| Grateful that community-health palliative care professionals were able to enter their homes and assist their family members with providing care to them (U) | ||

| The hospital doctors and nurses, district nurses could bridge the hospital/treatment dimension of the outside world and the disease/cancer dying world (U) | ||

| Some district nurses focused mainly on patients’ physical conditions, rather than their emotional needs (U) | ||

| District nurse emotionally supportive (U) | ||

| Felt that their end-of-life wishes to receive care at home were being honoured (U) |

U, unequivocal; GP, general practitioner; HCNs, health care nurses.

Category 4.1: Home was the preferred place of older adults to receive palliative care and to die

Older persons preferred to receive palliative care and die in their own home. Their home was where they felt they belonged, where they felt safe and comfortable, in their familiar surroundings with family and friends. They were less fearful of death when they were receiving palliative care at home. Older persons expressed their preference to receive palliative care and die at home rather than in health care facilities where they would be surrounded by strangers in a place where they did not belong, want to be, or return to. By receiving palliative care at home, older persons felt that their wish to die at home was honored. This category was supported by 9 findings.

[Home] is where I belong. I don’t belong in a hospital with the strangers. I belong at home. This is my house. This is where my family is. 34 (p.54)

I would rather die now than spend the time in the hospital…I don’t know those people. They’re strangers. Here my wife is. My pictures are here. My life was here. I just wish we started this early and that I didn’t waste time in the hospital with strangers. 34 (p.54)

Well now people come to my house so I don’t have to go to them. But now my daughter can do everything for me instead of them. Because I am home.” 34 (p.54)

Category 4.2: Informal support

Informal supports were described by older persons as a spouse, family member, friend, or neighbor. Varying expectations of informal supports were held by older persons, and their expectations were met to varying degrees. Sometimes there was too much support; sometimes they felt there was not enough. Older persons receiving palliative care at home wanted their family to provide the majority of their care. They recognized the importance and effectiveness of informal support, not only for themselves, but also for their caregivers. Older persons expressed concern about the burden on their caregivers. They gave care to their loved ones in the form of understanding and emotional support, such as preparing their loved ones for being on their own. This category was supported by 15 findings.

When I went to the hospital, my neighbor never missed a day and he was out there visiting me … If they don’t see one or both of us every day, they are right at the door bell to check. 35 (p.84)

I worry that she’s working too hard. She looks after me like a baby and it’s just a little too much for her. 27(p.13)

They supported me in one way—okay, they phoned—but they never came … I felt that was the hardest part. 27(p.15)

I had about 29 [visitors] in one day and they had to cut the visitors off because it wasn’t doing me any good. 27(p.15)

Category 4.3: Continuity of care

Older persons receiving palliative care in the community expressed their concerns and experiences with the continuity of care they received, which could be fragmented and uncoordinated. They did not want to receive care from strangers who were not aware of their needs or how best to address them. They were concerned about the unpredictability and the lack of continuity of care received from health care providers. They wanted to have the same formal support caregivers to provide continuity of care for them. This category was supported by 6 findings.

I never had the same doctor I’ve been in contact with a whole series of them. In addition, then they would spend the time reading my journal. I learned nothing new about my treatment. In addition, then I just had to leave. I felt I did not really have anything to do there. 28 (p.8)

Nobody knows what anybody’s doing and you don’t work as a team. 27(p.14)

They [nurses] write it down but the report in the end doesn’t go to the hospital, and from the hospital the reports doesn’t go to the VON [community nursing agency].27 (p.15)

The doctors don’t know. They don’t have a clue right now. I went to the cardiologist about 6 weeks ago, and he said “I think I have failed you”… I had 3 cardiologists in my room down there for 3 weeks. They can’t agree with each other. 35 (p.88-89)

Category 4.4: Communication and relationships with health care providers

Older persons receiving community-based palliative care recognized the importance of having good communication and relationships with their health care providers to enable their needs and wishes for their end-of-life care to be met. For some participants, communications with their health care providers were problematic, and they often delegated this to family members or to trusted members of their palliative care team, such as the nurses who provided their care in their homes. The older person’s relationships with their health care providers were complex and varied. Some older persons reported that they were not listened to, were treated insensitively, or were primarily related to in terms of their disease or as a sick and dying patient. Other older persons reported experiencing warm, trusting communications and relationships with their health care providers who related to them holistically, spoke to them honestly about their condition and future, and listened and demonstrated understanding of their feelings and concerns. This category was supported by 14 findings.

They told me that I was a cancer patient and I said well the doctor didn’t tell me that … It was, to tell you the truth, quite upsetting. 27 (p.15)

I guess the doctors were telling me there wasn’t much they could do for me any more. I guess that’s when it really hit me that the old heart could stop any time now … when you’re feeling good and when you don’t have any pain and that kind of stuff, if they sat down and slowly brought the subject to a head. I think that would have been better than just coming right out with it, especially when you weren’t feeling well.” 33 (p.50)

The doctors don’t listen to you. They are more interested in making your body well and it doesn’t matter how sick you feel.27(p.15)

When I’m at the doctors, and he tries to explain something, I hardly listen to what he says. 28(p.6)

Other older persons reported experiencing warm, trusting communications and relationships with their health care providers who related to them holistically, spoke to them honestly about their condition and future, and listened and demonstrated understanding of their feelings and concerns.

[Nurse’s] very understanding and when you’re talking about understanding in this day and age, it’s not easy to get people to understand your needs or your way of life … [Nurses] always put your needs first. 31 (p.2167)

But I like it when they [nurses] come. They explain things. And I am less scared because … when I forget they tell me it’s okay and they are like doctors, right so it makes me less scared … I know when she [community health nurse] comes she will check or she will tell my husband or son things are getting bad and when I should expect to go. The nurses make me feel less scared of death. 34 (p.56)

Category 4.5: Formal support

Older persons receiving palliative care in the community acknowledged and expressed appreciation for supportive formal services provided by health care providers, without which they would not be able to receive palliative care in their own home or have their wish to die at home honored. They spoke of the relief and comfort they received from nurses who could anticipate their needs, as well as their knowledge of resources that might be needed and how to procure these. The older persons appreciated the health professionals who came into their home, guided them to appropriate services and care, monitored and managed their symptoms and medications, and supported both themselves and family caregivers with the older person’s treatment and care. Older persons expressed confidence that nurses who were providing their palliative care at home would honor their wishes as to how their end-of-life care was provided. This category was supported by 6 findings.

This [district nurse] provides the intermediary. 30 (p.2635)

I’m so grateful that there are those things in the community that can support us at home. 27(p.14)

He [the doctor] tells you like it is. He doesn’t sugar coat it and that’s good because you know exactly where you stand. 27 (p.14)

I won’t get better or they won’t try to keep me alive with a machine. So then as soon as I found that out, I said “take me home.” But I couldn’t just go home. So they said they’d send someone once a week. And that’s it. This is what I wanted and because of my wife and the people who come I can. This is what I want. My wish is to be here. I got my wish.34 (p.63-4)

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review of qualitative studies exploring older persons’ perceptions and experiences of community palliative care. These were captured within 4 synthesized findings. In the first finding, older people recognized that their life has changed and came to terms with their situation, redefining what is normal, appreciating life lived, and celebrating the life they still have by living one day at a time. The second finding described their experience of isolation and loneliness exacerbated by their detachment and withdrawal from and by others. The third finding articulated major challenges they faced managing prevailing symptoms of breathlessness and fatigue, managing medications, and costs of care and medical equipment. The fourth finding identified their need to receive palliative care and to die at home, which requires both informal and formal supports, including continuity of care, good communication, and positive relationships with health care providers.

Older persons receiving palliative care in the community experience multiple unexpected, unpredictable, uncontrollable changes related to their health, identity, roles, relationships, and environment. For some older persons, significant change may occur when they experience the loss of ability to maintain their usual physical and social activities.32,35 Such limitations on their normal everyday activities brought the experience of “dying while living.”32(p.342)

Older persons largely became aware of their situation when they received their diagnosis, prognosis, and proposed plan for palliative care from medical professionals. The studies included in this review, however, gave little information on how and when the diagnosis was delivered or received, or whether there was any negotiation or active involvement in the older person’s proposed planned palliative care. Older persons reported that their recognition and acknowledgment of their situation was accompanied by feelings such as loss of control, helplessness, resentment, or surprise.27,29,32,35 For some older persons, acknowledgment that they were dying, and their acceptance of palliative care by health professionals, opened up perceived possibilities of their living at home and extending their life expectancy by many years with such care.34 These findings highlight the need for community palliative care services and health workers who can provide compassionate care.

This review adds to the research related to the concept of “living while dying,”32(p.338,341),35(p.101) illuminating the older person’s experience of living in the uncertain context of dying.36 Studies show that persons receiving palliative care are at risk of losing their identity as a social person.36–38 Importantly, in our review, older persons receiving community palliative care challenged the changes imposed by their situation by maintaining their personhood through valuing, continuing, and normalizing their physical activities and social relationships.29,32

We found that some older persons experienced intrapersonal and interpersonal isolation in relation to their diagnosis, as well as geographical and social isolation from home-based, community palliative care.29,30 Some older persons felt marginalized due to their inability to participate in their usual life activities, and were perceived as a sick, dying person and thus a burden to others, with their family and friends initiating detachment and withdrawal from them.32 The ambivalence of wanting to be left alone and yet not wanting to be alone led some older persons receiving palliative care in their home to withdraw and detach from others, including their palliative care nurses.32 This highlights the need for palliative care staff to identify loneliness in patients and to develop strategies they may employ to address this.

The participants in this review found it difficult to determine and manage prevailing symptoms. Breathlessness, and the subsequent anxiety associated with managing it, was connected to fears around the increasing deterioration of their health and the imminent approach of the end of their life.35 Some older persons receiving community-based palliative care had difficulty judging when to call health providers or seek hospital admission for increasing severity of symptoms such as breathlessness. The literature reports that the severity of breathlessness may increase in the last months of life for persons with advanced illness, leading to frequent admissions to emergency and acute wards.39,40 Breathlessness may be difficult to manage clinically, with limited effective, evidence-based interventions available.41–43 To ensure that high-quality, comprehensive, coordinated, person-centered, community-based care is provided, it is important that the palliative care team include the patient and their family and caregivers in negotiations and discussions about how their actual and potential symptoms and palliative care may be best managed.43

As the older person’s breathlessness and fatigue increased, they were no longer able to manage their medications, requiring others to take over medication management.35 The literature reveals that poor medication management is partly caused by fragmented and uncoordinated information-sharing among health care professionals working in the community and hospital settings.44 This review showed that older persons may delay seeking help due to prohibitive costs of medical care and equipment for palliative care at home, as well as for emergency transport and admissions and treatment in hospitals.27,35,42 A coordinated multidisciplinary team involved in transporting the older person between hospital and community may be less burdensome and less distressful.45

The participants in this review wanted to receive palliative care and die in the place they felt they belonged, in their own homes surrounded and supported by their family and friends, rather than in a hospital surrounded by strangers. Being in their own home provided them with feelings of safety and comfort, and lessened the fear of dying.34 In addition, for older persons with dementia receiving palliative care in the community, the home provided a familiar and supportive environment, which allowed them to be more independent.34

Despite the preference of older persons to die at home, the literature indicates that there is low congruence between the preferred and actual place of death.46–50 A recent Australian study50 found that while 80% of older persons receiving end-of-life care at home preferred to die at home, only 22% were able to do so, with the majority of older persons transferred to hospitals at the end of life and subsequently dying in hospital settings. Research shows that the increased physical dependency and medical needs of persons close to death may result in their home environment being changed into a clinical setting, as medical equipment, hospital beds, and oxygen tanks are added, and more regular visits by health care professionals occur.51 Additionally, the literature shows that for end-of-life care, home may not be—or no longer be—the preferred place to die.52 This change of preference may be due to lack of quality after-hours support at home,53 lack of multidisciplinary care coordination and continuity,54 concerns about safety,55 perceived burden to family or carers,56 financial concerns,57 or concerns about pain control and symptom management.58 Changes in preference from home death to hospital death during the final phase of illness may be initiated by older persons or by their family or carers.59

Encouraging older adults to have an advance care plan enables them to make informed decisions about their preferences for where they want die and receive care and treatment. Ideally this should occur before the need arises for palliative care.60 To achieve this, public education is necessary to inform the community of the benefits of advance care planning. Irrespective of whether the patient has an advance care plan, the challenges associated with dying at home (eg, arranging services, symptom management, loneliness and isolation, difficulty coping) highlight the need for the dying person and family to be supported by empathetic and compassionate staff with education and expertise in palliative care.61

Informal supports were of vital importance for the older person in terms of ability to continue to receive palliative care in their own home and have their end-of-life wishes respected. Some older persons reported receiving too little or too much informal support.27 Older persons preferred to have family members as their carers.34 In turn, they became aware of the burdens and negative toll on those who were caring for them, and became caregivers to those who cared for them.27,32 Palliative care practices that include carer education and support are essential to avoid negative impacts on the carer and, importantly, their relationship with the patient.

Older persons in this review acknowledged that continuity of care was a positive, essential aspect of formal supports; however, formal supports could be fragmented, unpredictable, and lacking continuity and adequate coordination.27,28 Despite the importance of continuity and coordination of care and a collaborative interdisciplinary approach for delivery of palliative care, fragmentation of services and poor coordination are common themes in the literature.28,62,63 Older persons receiving community-based palliative care in this review had complex and varied communications and relationships with their health providers. Some older persons reported experiences of being treated insensitively, not being listened to or included in the decision-making for their own care, or receiving care focused primarily on their physical health care needs.27,30,32 This could lead to the older person withdrawing from participation in their communications with health care providers and delegating communication to family members or to trusted members of the health care team, such the nurses who provided care in their homes.28,31,34 The literature shows that older persons and their carers who have impaired communication, poor negotiation skills, and little confidence communicating with health care providers are at risk of being marginalized from decision-making regarding their own health care.64–66

Other older persons in this review reported empathetic, trusting communications and relationships with their health providers who provided holistic care, delivered honest and informative communications about their conditions and future, and included them in the planning and implementation of care.30–32,34 These findings support the literature demonstrating that older persons’ autonomy and dignity help them to maintain their personhood and encourage their active involvement in decision-making related to their health care.64,66

Limitations of the review

The review was limited to studies published in English. The available studies focused on older persons with cancer and heart failure who experienced community-based palliative care, with only 1 study of older persons with dementia included in the review. There was variation in participants’ illnesses and illness trajectories within and across the studies, in data collection and analysis, and the contexts of the studies. Due in part to the difficulty recruiting and maintaining the participation of older persons receiving palliative care in research studies, there were small numbers of participants in each of the studies reviewed. This may present a limited view of the perceptions and experiences of older adults receiving community palliative care.

Strengths of the review

According to our knowledge, this is the first systematic review of older persons’ experiences and perceptions of community-based palliative care, providing a comprehensive overview of the services and gaps in practice, education, and research. To date, there are few studies that focus on older persons’ experiences and perceptions of receiving palliative care in the community and even fewer that have only older persons as participants. Qualitative studies of older persons receiving palliative care tend to explore the experiences of carers and health care professionals as well as the older person’s perspectives and experiences, and data collection may also involve family and/or carers in the interviews with the older person. This may impede the voices of the older person to be heard above the louder and more dominant voices of health care professionals, carers, or family members. This review, therefore, has included only older persons who were receiving community palliative care as participants, and data collected relating to their own experiences and perceptions of their community-based care. This allows a platform from which the voices of older persons receiving palliative care in the community can be clearly identified and heard. Hence, this adds new and critical knowledge that can contribute to developing and informing policy, as well as implementing and evaluating best-practice, empathetic, respectful, person-centered community-based palliative care models that uphold the older person’s rights, including the right to make decisions related to their own palliative care, and to maintain their personhood.

Conclusions

The role of palliative care varies according to the context of care. Palliative care delivered in the community can have different challenges compared with a palliative care inpatient unit or palliative care undertaken in the acute hospital setting. Nonetheless, research-informed policy is fundamental to identify appropriate resources, including the need for qualified palliative care staff to provide care. Older persons have the right to make choices regarding their care and the right to access good palliative care. Consequently, their input in decision-making about their care is fundamental to meeting their needs and is contingent on effective communication between the patient, family, and staff across services.

Recommendations for policy

Policy is needed that adopts frameworks underpinning community palliative care that enable doctors and community nurses to optimize practice. Framework elements may include guiding principles for care, and promotion of education and collaboration among staff to optimize evidence-based care.

Recommendations for practice

The voices of older persons from the 9 research papers have highlighted that improvement is still needed when palliative care is provided in the community; therefore, a number of recommendations are suggested. Recommendations are rated according to the JBI Grades of Recommendation.67

Palliative care staff, including medical practitioners, nurses, social workers, and other allied health workers in hospital, aged care facility, community, hospice, and home settings, need to work together to provide individualized person-centered care, acknowledging both the patient’s and carer’s needs and strengths, and in accordance with the patient’s acceptance and understanding of their end-of-life prognosis and their experience of palliative care. (Grade A)

Older persons’ active involvement in the planning and implementation of their care, including information about symptom management and palliative care options, is necessary for high-quality care. (Grade A)

Practitioners need to engage in respectful, empathetic, and supportive communication with older persons to enable them to voice their fears and concerns. (Grade A)

Isolation and loneliness often accompany aging and ill health requiring palliative care. Engagement with support networks, including family and relevant community services, may help to alleviate this. (Grade A)

Recommendations for research

This study highlights the need for additional studies relating to older persons’ experiences and perceptions of community-based palliative care. There is also a need for studies to evaluate the implementation of best-practice models and policies, and their impact on the quality of palliative care provided as well as patient satisfaction with care provided. The study also highlights the difficulties in recruiting and retaining older persons receiving palliative care to participate in research studies exploring their experiences of palliative care. Given the small numbers of palliative patients in such studies, it is difficult to explore the experiences of patients with different diagnoses (eg, different cancers) or for different genders, socioeconomic groups, or countries. Hence, further research into developing and using appropriate methodology and methods that will allow for such research is urgently needed to inform the development of person-centered models of community care.

Research is also needed in relation to how community palliative care providers can best promote and facilitate older persons’ autonomy; power; control; and informed, active decision-making relating to their palliative care in the community. Older persons require adequate information, explanation of viable options, and the opportunity to make informed decisions. Further research is required to evaluate current models and to develop new models of community-based palliative care that can provide person-centered, palliative care oriented to the individual patient and the specific community in which the palliative care is delivered.

Appendix I: Search strategy

Searches conducted July 2021 and updated November 1, 2022

CINAHL (EBSCOhost)

| Search ID | Search terms | Records retrieved |

|---|---|---|

| S1 | (MH “Palliative Care”) OR (MH “Terminal Care”) OR (MH “Hospice Care”) OR (MH “Hospice and Palliative Nursing”) | 62,707 |

| S2 | (MH “Home Health Care”) OR (MH “Home Health Aides”) OR (MH “Home Rehabilitation”) | 28,508 |

| S3 | (MH “Primary Health Care”) | 72,503 |

| S4 | (MH “Perception”) | 31,651 |

| S5 | (MH “Attitude”) | 18,334 |

| S6 | (MH “Life Experiences”) | 34,379 |

| S7 | S2 OR S3 | 3474 |

| S8 | S1 AND S7 | 82,772 |

| S9 | S7 AND S8 | 69 |

| S10 | S9 (Limiters -Publication Date:2000- 2022; Language: - English) | 67 |

MEDLINE (Ovid)

| Search ID | Search terms | Records retrieved |

|---|---|---|

| S1 | Palliative Care/ or “Hospice and Palliative Care Nursing”/ or Palliative Medicine/ | 62,593 |

| S2 | Home Care Services/ or ‘home care’.mp. | 54,689 |

| S3 | Primary Health Care/ or ‘primary health care’.mp. | 106,838 |