Abstract

Purpose:

To examine the support from different sources of Chinese families of patients with moderate-to-severe dementia that most heavily influences the family adaptation and the influence pathway.

Method:

Two hundred and three families participated in this study. Chinese versions of instruments were used. Structural equation modeling was applied to confirm the effect pathway.

Results:

More family support, kin support, community support, and social support (narrow sense) were related to greater levels of family adaptation. Family support was the most heavy influence factor (total effect = 0.374), followed by kin support (0.334), social support (0.137), and community support (0.121). Family support and kin support were direct influence factors, while the other 2 were not.

Conclusion:

All support will promote family adaptation, especially family support and kin support. Interventions improving support from different sources, especially family support and kin support, will promote adaptation in Chinese families of patients with moderate-to-severe dementia.

Keywords: caregivers, dementia, China, family, adaptation, social support

Introduction

Dementia is a progressive disorder that causes irreversible changes in the brain, resulting in memory impairments, confusion, difficulties with problem-solving as well as mood and personality changes. 1 It is estimated that there are 47 million people with dementia worldwide currently and 150 million in 2050. 2 This figure in China is 95 million nowadays. 3

Due to diseases’ effect on the cognitive, emotional, and behavioral functioning, individuals with dementia require increasing amounts of assistance with activities of daily living (ADLs), and management of memory and behavior problems. 4 Most of the assistance and management is provided by family. 5 Dementia affects the family as well as the individual. 4 Because of the encouragement of filial piety and collectivism under Chinese culture, the proportion of patients with dementia taken care by their children and children-in-law is from 52.6% to 67.4%, which is much higher than Western counties (28.7%). 6 –8 Average age of adult children caregivers of patients with dementia is from 50.5 to 56.6. 9 –11 As research shows, they are losing health, social support, and quality of life gradually. 12 As a result, adult children caregivers always experience heavier burden than spouse caregivers. 8 If they cannot adapt to this situation, it will lead to depression, 13,14 sleep disturbance, even thoughts of suicide, 15 family conflicts 16 –19 , and economic vulnerability. 18 –20 These outcomes of family maladaptation threaten life quality of patients with dementia and even have the possibility to start up a vicious circle. 18,19

Social support (broad sense) is not only family coping resource, but coping result during family adaptation process as well. It always has more stable effect on family adaptation than coping 21,22 because it determines the rebalance between stressor and resource finally. A numbers of studies have confirmed the significant role of social support (broad sense) in family adaptation among families of patients with chronic disease. 23 –25 According to The Resiliency Model of Family Adjustment and Adaptation (FAAR) developed by McCubbin and colleagues, broad-sense social support (B-social support) included family support (FA), kin support, community support, and social support (narrow sense of social support, N-social support). 26 In previous studies, the phenomena that support from different sources had different effect on family adaptation have been reported. 27,28 The positive effects of FA and kin support on family adaptation were confirmed. 27,29 –34 But the results were variant when it comes to community support and N-social support. 27,30,31 In Deist’s qualitative studies on family of patient with dementia, FA had been mentioned by around 90% caregivers as promoting factor of family adaptation. 32,33 Brody’s qualitative research reported that kin support was most helpful when the family was busy enough with caring the patients. 27 Yeh’s quantitative research also confirmed the effect of kin support. 30 When it comes to community support, many qualitative studies have mentioned its positive effect. 27,31 But in quantitative studies, the results were different. 30,31 For N-social support, the results of its effects were not consistent among different participants or different specific source of support. 27,31 Even in Brody’s research, the caregiver team support was argued as negative effector by some participants. 27 And in Choi’s 31 research, the health-care team support was rare, let alone the effect. In quantitative research, the N-social support from health-care team had not shown any effect. 30 In China, the phenomenon was the same as that of the above studies: supports from different sources have different effects. Chinese people distinctively interact with other people according to their relationships, which is called hierarchical order (cha xu ge ju). 35 As a result, the support from different sources (family member, kin, community, and society) was accumulated, perceived, and used differently, which leads to different amount and different effects on family adaptation. Even though there were few studies that reported the relationship between support and family-level adaptation in China, one case study has described the significance of FA, kin support, and N-social support to a family in crisis. 36 And one quantitative study has reported that the correlationship between FA and family adaptation was stronger than kin support and community (friend) support. 37 But most of previous research were qualitative studies. 27,28 Quantitative research and analysis is needed to quantify the difference and to detail their pathway.

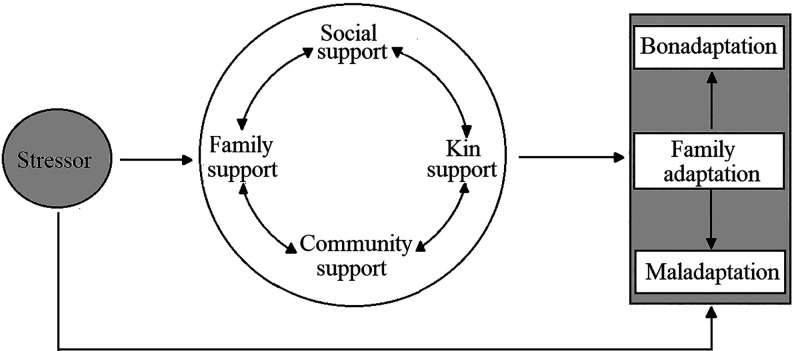

Aiming to examine the support from different sources of Chinese families of patients with moderate-to-severe dementia that most heavily influences the family adaptation and the influence pathway, one series of hypotheses derived directly from FAAR (Figure 1) were applied as framework of our research. The hypotheses included (a) different sources of support (eg, FA, kin support, community support, and N-social support) would directly influence adaptation and families with more support would have better adaptation; (b) the different sources of support were correlated with each other; (c) stressor influenced different sources of support directly; and (d) stressor influenced family adaptation directly. 26 Before this research, 8 experts with more than 10 years of research experience in cultural psychology, family sociology, geriatric sociology, and community nursing (geriatric nursing) were invited for experts argumentation. The definitions of FA, kin support, community support, and N-social support under Chinese culture were clarified and guided this research. Among them, the translation and definitions of community support and N-social support were clarified and revised based on the original definition and research, and fit to Chinese culture. 26,35,38 Community support was translated into She qun zhi chi. It is help or joint force provided by the people who are considered as a unit member with the family because of common interests, social group, hometown, or living place when the family are confronting with crisis or difficulties. It includes support from friends, neighbors, colleges, classmates, employers, and partners in organizations or teams. N-social support was translated to She hui zhi chi. It is a public, open, emerging support provided by unrelated people or institutions. Comparing with community support, N-social support is the support provided in a wider field outside the community. This support often occurs and functions when the family is confronted with a specific situation or crisis. It includes the support provided by formal institutions or organizations (such as community health services, hospitals, state welfare institutions, etc) or informal organizations (such as social public welfare organizations, volunteer groups, caregiver mutual assistance, or support groups, etc).

Figure 1.

Hypothesis model derived from “the resiliency model of family adjustment and adaptation.”

Method

Participants

The sample was comprised of 203 families of patients with dementia from China. Convenient sampling method was adopted in this study. Families were recruited through referral (self, physician) from Memory specialist clinic and Geriatric psychiatric clinic of Peking Union Medical College Hospital, Xuanwu Hospital Capital Medical University, China-Japan Friendship Hospital, Beijing Anding Hospital from October 2017 to March 2018. They were eligible to participate in this study if the family fulfilled the following criterion: (a) a family member (≥60 years old) diagnosed with dementia, (b) dementia symptoms were moderate to severe, (c) the child or child-in-law of the person diagnosed with dementia acted as primary caregiver, and (d) the person diagnosed with dementia had been living with the family for at least 6 months. There were 223 families who met the inclusion criteria and participated in the study. After consent, one family member, who was chosen by the family unit to act as the family representative, took part in the data collection process. Finally, 203 questionnaires of families were found to be valid.

Our sample comprised of 203 patients aged between 60 and 95 (median = 82), with most of them being women (65.5%). Alzheimer disease was the most common cause of dementia in patients in this research. The second most common one was vascular dementia (30.1%). One hundred and eleven (54.7%) and 92 (45.3%) patients were assessed with moderate dementia and severe dementia, respectively. The average length of time from the person diagnosed with dementia was 18 months. Only 48.3% spouses of patients were alive and aged from 60 to 98 (median = 79). Most of living spouses (66.0%) cannot do anything, and 28.6% spouses can only accompany the patients. Eighty-two (40.4%) patients were taken care by one adult child nuclear families, 51 (25.1%) taken care by 2 adult children nuclear families, 39 (19.2%) by 3, and 15.3% by more than 3. The median age of the adult children taking care of patients was 53 (P25 = 45, P75 = 58), with 4.9%, 34.0%, 52.7%, and 8.4% of the sample reporting to have educational background of junior middle school, high school, college, and graduate degree, respectively. Minority (27.6%) of families hired assistants to help taking care of patients. The details were shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic and Disease-Related Characteristics of Patients and Families.

| Demographic and Disease-Related Characteristics | M (P25 , P75 ) | N | Proportion (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 82 (76, 87) | |||

| Gender, % female | 133 | 65.5 | ||

| Types of dementia | Alzheimer disease | 116 | 57.1 | |

| Vascular dementia | 61 | 30.1 | ||

| Others or unknown | 26 | 12.8 | ||

| Dementia severity | Moderate | 111 | 54.7 | |

| Severe | 92 | 45.3 | ||

| Length of time diagnosed (month) | 18 (5, 41) | |||

| Spouses, % alive | 98 | 48.3 | ||

| Age of spouses, years | 79 (74, 82) | |||

| Care capability of spouses | None | 134 | 66.0 | |

| Only accompany | 58 | 28.6 | ||

| Do everything | 11 | 5.4 | ||

| N of adult children nuclear families involved in caring | 1 | 82 | 40.4 | |

| 2 | 51 | 25.1 | ||

| 3 | 39 | 19.2 | ||

| ≥4 | 31 | 15.3 | ||

| Average age of adult children | 53 (45, 58) | |||

| Educational background of adult children | Junior middle school | 10 | 4.9 | |

| High school | 69 | 34.0 | ||

| College degree | 107 | 52.7 | ||

| Graduate degree | 17 | 8.4 | ||

| Hired assistance, % | 56 | 27.6 |

Measures

A researcher-created questionnaire was used to gather demographic and disease-related information of patients and families. Three measures were used to assess different sources of support. They were Family Inventory of Resources for Management (FIRM), Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS), self-designed Social Support Scale (SSS). Family Adaptation Scale (FAS) was used to measure family adaptation. In an effort to control the confounding effect produced by family stressors, they were measured too. According to the characteristic of stressors in family of patients with dementia, 16,39,40 the stressors were measured by The Revised Memory and Behavior Problems Checklist (RMBPC), Activity of Daily Living (ADL), and Family Inventory of Life Events and Changes (FILE).

The Chinese versions of RMBPC, ADL, and MSPSS were readily available; however, FILE, FIRM, FAD did not have accessible measurements of Chinese versions. And there was no appropriate measure of N-social support. Before this research, FILE, FIRM, and FAD were translated by 2 bilingual and bicultural researchers into Chinese and then back-translated into English by 2 separate bilingual and bicultural researchers. Any discrepancies between the original English and back-translated English versions were mutually resolved. And measure of N-social support (SSS) was researcher-created according to the definition of N-social support.

Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support

It was developed by Zimet to measure the extent to which an individual perceives B-social support from three sources: significant others (SO), family, and friends. The MSPSS is a brief, easy to administer self-report questionnaire containing 12 items, each rated on a 7-point Likert-type scale with scores ranging from “very strongly disagree” (1) to “very strongly agree” (7). 41 It was translated into Chinese version by Jiang through a standard process. 42 In Chinese version, there are only 2 dimensions: FA and SO (included original friends support dimension and original significant other support dimension). For this research, FA was used to measure FA, and Chinese-version SO was used to measure community support since the definition of community support is the support from friends, neighbors, colleges, classmates, employers, and partners in organizations or teams. When we measured the community support, we reserved the original friend support dimension to measure support from friends and revised the original SO dimension to measure the supports from community except friends. In original SO dimension, we listed the SO, including the neighbors, colleges, classmates, employers, and partners in organizations or teams of any family member and asked the participants about to what extent you agree that these persons help your family. The combination of original friend support dimension and revised SO dimension was used to cover whole community support. Besides that, in an effort to measure the support whole family possessed, not individual, the Chinese MSPSS involved an adaptation of the instructions with the change from “you” to “your family.” The revised scale for this study was found to have good internal consistency; the Cronbach α of FA was 0.874 and the Cronbach α of SO was 0.908. The subscale of FA yielded an acceptable model: adjusted Goodness-of-Fit Index (AGFI) = 0.898; Goodness of Fit Index (GFI) = 0.990; and Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) = 0.126. The subscale of SO which measures community support yielded an acceptable model: GFI = 0.959, AGFI = 0.912, RMSEA = 0.064. The values of reliability and validity reported above were achieved using the whole sample of our study (203 families).

Family Inventory of Resources for Management

It is a self-report questionnaire consisting of 4 subscales including (a) family strengths-I: esteem and communication; (b) family strengths-II: mastery and health; (c) extended family social support; and (d) financial well-being. In this study, the subscale of extended family social support with 4 items which measures support from relatives was used to measure kin support of family. Participants responded to each item from 1 (not at all) to 4 (very well) on a 4-point Likert-type scale. For this study, FIRM was translated into Chinese. Item-level Content Validity Index (I-CVIs) of extended family social support subscale were all 1.000 and scale-level Content Validity Index (S-CVI) was 1.000. This subscale yielded an acceptable model: AGFI = 0.995, GFI = 0.999, and RMSEA < 0.001. Cronbach α was 0.661. The values of reliability and validity reported above were achieved using the whole sample of our study (203 families).

Social Support Scale

In this study, a self-designed SSS was used to measure the level of N-social support the “family of patients with dementia” has. The construction of SSS is based on the concept of “N-social support” determined by expert argumentation. N-social support is a public, open, emerging support provided by unrelated people or institutions. It includes the support provided by formal institutions or organizations (such as community health services, hospitals, state welfare institutions, etc) or informal organizations (such as social public welfare organizations, volunteer groups, caregiver mutual assistance or support groups, etc). The SSS is a brief, and easy-to-administer self-report questionnaire containing 6 items, each rated on a 7-point Likert-type scale with scores like “very strongly disagree” (1), “strongly disagree” (2), “mildly disagree” (3), “neutral” (4), “mildly agree” (5), “strongly agree” (6) and “very strongly agree” (7). For this study, the validity and reliability of SSS were evaluated. The I-CVI and S-CVI of this scale were both 1.000, and this scale yielded an acceptable model: GFI = 0.976, AGFI = 0.943, and RMSEA = 0.055. Cronbach α was 0.831. They proved that the scale had good validity and reliability. The values of reliability and validity reported above were achieved using the whole sample of our study (203 families).

Family Adaptation Scale (FAS)

FAS which was developed by Antonovsky in 1988 consists of 11 semantic differential items. 43 In each case, the extreme anchor phrases were 1 (completely satisfied) and 7 (dissatisfied). Due to the development of definition of family adaptation by McCubbin in 2001, FAS was modified with additional 4 items in this research. The modified scale included 14 items referred to satisfaction with 4 domains of family systems functioning: (a) family’s interpersonal relationships; (b) family’s structure and function; (c) development, well-being, and spirituality of the family unit and its members; and (d) family’s relationship to the community and the natural environment, and one item measures the overall adaptation. In order to avoid confusion or trouble to respondents, all items of FAS in this research were positive scoring items. For this research, the I-CVI and S-CVI of this scale were both 1.000 and this scale yielded an acceptable model: GFI = 0.932, AGFI = 0.884, and RMSEA = 0.058. Cronbach α was 0.951. They proved that the scale had good validity and reliability. The values of reliability and validity reported above were achieved using the whole sample of our study (203 families).

Revised Memory and Behavior Problems Checklist

Revised Memory and Behavior Problems Checklist was used in this study to measure the first kind of stressor: memory and behavior problems of patients. Items of RMBPC used in this research consisted of the same 24 items retained by Teri et al. 44 These items inquire about problem behaviors displayed by patients in 3 domains: memory-related problems, depression, and disruptive behaviors. The RMBPC has two response subscales: occurrence (frequency of problems) and reaction (the impact that these problems have on the caregiver). A modification was made to the response format used in occurrence subscale by National Institutes of Health multisite initiative, Resources for Enhancing Alzheimer’s Caregiver Health (REACH). 45 Instead of asking the respondents to rate the frequency of each problem on a 0 (never) to 4 (daily or more often) 5-point scale, modified RMBPC simply asked the caregivers to indicate whether the problem had occurred during the past week (ie, “yes” or “no”). In this study, only the modified subscale of occurrence was used. The number of problems that occurred during the past week was added as the total scores. The modified subscale of occurrence in RMBPC yielded an acceptable model: AGFI = 0.91; GFI = 0.92; RMSEA = 0.07. 45 For this study, Cronbach α was 0.869 for the whole sample (203 families).

Activity of Daily Living

Activity of daily living was used in this study to measure the second kind of stressor: dependence of ADL of patients. Measurement that used in this study was developed by Lawton and revised by Zhang. 46,47 The revised measurement consisted of 20 items. These items inquire about ADLs displayed by patients with dementia in 2 content areas: basic ADLs and instrumental ADLs. The response of item of ADLs ranged from 1 (completely independent) to 4 (completely dependent). The scores of every item were added as the total score. This measurement had a good concurrent validity (the correlationship with MMSE was 0.45, P < .001), and 1-year test–retest reliability coefficient was 0.42 (P < .001). 47 For this study, Cronbach α was 0.956 for the whole sample (203 families).

Family Inventory of Life Events

Family Inventory of Life Events was used in this study to measure the third kind of stressor: life events and changes of family. The English version of FILE consists of 71 yes/no items, grouped into 9 subscales: intrafamily strains, marital strains, pregnancy and childbearing strains, finance and business strains, work–family transitions and strains, illness and family “care” strains, losses, transitions “in and out,” and legal. The overall scale reliability (Cronbach α) was 0.81, with the subscale scores varying from 0.73 to 0.30. 26 Validity was established by performing discriminant analyses comparing low-conflict and high-conflict families who had a child with myelomeningocele or cerebral palsy; high-conflict families in each of these groups were found to have significantly higher pile-up of life changes compared to low-conflict families. 26 For this research, FILE was translated into Chinese and adapted to Chinese culture. The Chinese version of FILE consisted of 67 yes/no items grouped into the same 9 subscales as English version. For this study, I-CVIs of this version ranged from 0.667 to 1.000, S-CVI was 0.932. And its construct validity through hypothesis testing approach was good (the correlationship with FAS and RMBPC were −0.343 and 0.279, respectively, P < .001) . Cronbach α was 0.856. The values of reliability and validity reported above were achieved using the whole sample of our study (203 families).

Procedure

This study was reviewed and approved by the ethics committee of the Peking Union Medical College (China). All participants received an explanation of the study and signed an informed consent prior to enrollment. After the family agreed, one family member, who was chosen by the family unit to act as the family representative, took part in the data collection process. Subsequently, the participants completed a 15- to 20-minute questionnaire with a nursing researcher, which took place during the family of patients’ routine visit to memory specialist clinic and geriatric psychiatric clinic of Peking Union Medical College Hospital, Xuanwu Hospital Capital Medical University, China-Japan Friendship Hospital, Beijing Anding Hospital. During this time, the participants provided demographic and disease-related information and filled out the paper-and-pencil measures. The participants received a gift worth 20 RMB as compensation for their participation.

Data Analysis

The major analysis was conducted using structural equation modeling (SEM) to better understand how much and how different sources of support influence family adaptation.

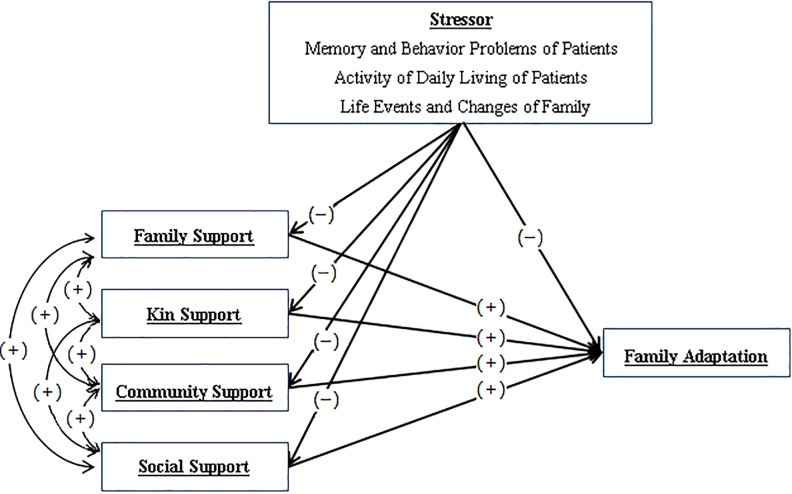

Firstly, hypothesized model was established based on a series of hypotheses derived directly from FAAR (Figure 1), as we have described in the introduction. 26 Besides that, researchers have summarized that stressor in families of patients with dementia included initial stressor (memory and behavior problems of patients, defect of ADL of patients) and pile up (additional hardship above and beyond the initial stressor). 16,26,39,40 Based on the above hypotheses, hypothesis model showing the effect and pathway of different sources of support on family adaptation was formed and shown in detail in Figure 2. It contained one latent variable and 8 observed variables. One latent variable was stressor, which included 3 observed variables: memory and behavior problems of patients, ADL of patients, life events, and changes of family. Except 3 observed variables in stressor, there were 5 observed variables which were FA, kin support, community support, N-social support, and the outcome: family adaptation. The hypotheses of relationships between variables were totally the same as that of FAAR. The main aim of this research is to explore the relationships between supports and family adaptation. But in an effort to control the confounding effect produced by family stressors, which influence both different sources of support (eg, FA, kin support, community support, and N-social support) and family adaptation according to FAAR, they were involved in the hypothesis model.

Figure 2.

Hypothesis model showing the effect and pathway of different sources of support on family adaptation.

Secondly, the distribution of all variables in the model was assessed through analyzing the values of skewness and kurtosis. According to Curran et al, values lower than 2 and 7 for skewness and kurtosis of variables, respectively, indicate the existence of a multivariate normal distribution and the variables could be analyzed by SEM. 48 Then, SEM with latent variables was applied to confirm the hypothesis model using Amos version 21.0.

The following criteria were used to determine whether the model fit the data: a value of 3.00 or lower on χ2 of model fit/df (χ2/df), 49 0.90 or greater on the Goodness-of-fit Index (GFI), Tacker-Lewis Index (TLI), Normed Fit Index (NFI), Adjusted Goodness-of-fit Index (AGFI), and Comparative Fit Index (CFI), 0.50 or greater on Parsimony-adjusted NFI (PNFI) 50 –53 , and a Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA)of 0.08 or lower. 54 When the original model developed according to the original hypotheses did not reach criterion, the model would be modified on the basis of modification indices, significance of regression weights, and literature review. A significance level of 5% (α < 0.05) was used for the analysis.

Results

Descriptive Statistic Results

The total scores of variables were not normal distributed; we presented them with median (M), the 25th percentile (P25 ), the 75th percentile (P75 ), minimum (Mix), and maximum (Max). The item average score was equal to median score of total score divided by the number of items.

The result revealed that the patients with moderate-to-severe dementia in this study had 11 memory and behavior problems in the last week (M = 11). The result also showed that the patients were dependent on ADLs (M = 55, average score of every item was 2.750, nearly dependent). There were 8 kinds of life events and changes (such as intrafamily strain, illness, and family “care” strains) of family that happened in the last year.

The median total score and average item score of FA were 23 and 5.750, respectively. The average item score of FA at the high level represented that family “very agree with that the family supported every family member.” The median total score of kin support was 8 and average item score was 2.000 which represented that “family’s kin always supported the family.” The median total scores of community support and N-social support were 39 and 17, respectively, and the average item scores were 4.875 and 2.833. These represented that the family “mildly agree” with that the community supported the families while “mildly disagree” with that society supported the families.On the contrary, when it comes to family adaptation, the median total score was 75 and average item score was 5.000 which were higher than the middle score (60 and 4).

Absolute values for skewness and kurtosis of variables were 0.187 ∼ 0.960 and 0.175 ∼ 1.008, respectively, which indicated the existence of a multivariate normal distribution and the variables could be analyzed by further SEM according to Curran et al. 48

Structural Equation Modeling Analysis Result

This SEM analysis was applied to examine the effect of different sources of support on family adaptation and the influential pathways. In the SEM analysis, the original model which was established according to hypothesis model was tested first, including all possible pathways between the stressors, support (FA, kin support, community support, N-social support), and family adaptation. The results of SEM partly supported the original hypothesis model, that is, many relationships were not statistically significant (P < .05), which are shown in detail in Table 2.

Table 2.

Statistical Analysis of Relationship Significance.

| Relationship | Estimate | Standardized Estimates (SE) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stressor → Family support | −0.890 | 0.314 | .005 |

| Stressor → Kin support | −0.437 | 0.162 | .007 |

| Stressor → Community support | −0.392 | 0.535 | .464 |

| Stressor → N-Social support | 0.504 | 0.438 | .250 |

| Stressor → Family adaptation | −2.669 | 1.024 | .009 |

| Family support → Family adaptation | 1.131 | 0.270 | <.001 |

| Kin support → Family adaptation | 1.071 | 0.478 | .025 |

| Community support → Family adaptation | 0.136 | 0.115 | .235 |

| N-Social support → Family adaptation | 0.212 | 0.133 | .110 |

| Stressor → Activity of daily living | 2.689 | 0.966 | .005 |

| Stressor → Memory and behavior problems | 1.000 | – | – |

| Stressor → Life events and changes | 2.843 | 0.953 | .003 |

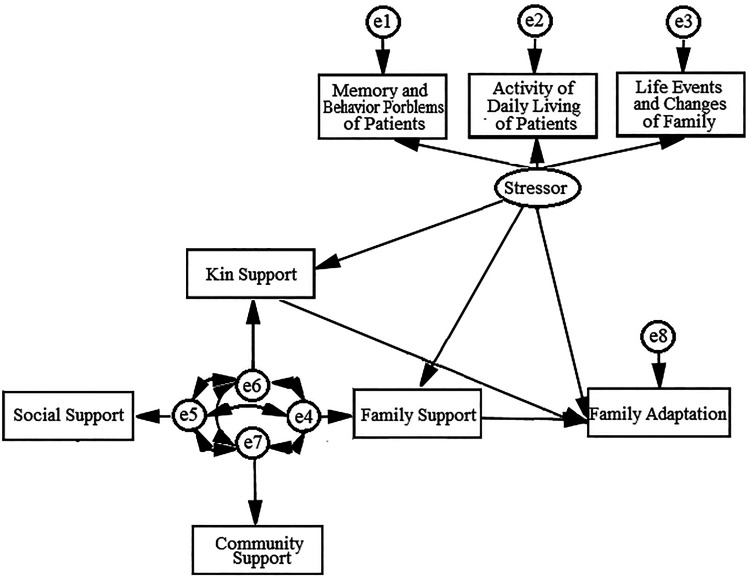

Based on the above results of statistical analysis of relationships, the pathways between stressor and community support, stressor and N-social support, community support and family adaptation, N-social support and family adaptation should be deleted. After taking into consideration the characteristics of Chinese culture and social environment, which will be discussed in detail in the discussion, these pathways were deleted and the modified M1 was formed. Figure 3 shows the M1. The measures of model fit were as follows: χ2 of model fit/df (χ2/df) = 1.463, GFI = 0.977, AGFI = 0.941, NFI = 0.937, TLI = 0.956, CFI = 0.978, PNFI = 0.469, RMSEA = 0.048. All indices suggested that the M1 fit the data well but PNFI, which meant that the model was not brief enough. This was because the theoretical framework of this research FAAR was developed based on a lot of theories and aimed to shed light on complex phenomenon. 26 So, it cautiously encompasses the real or potential pathways suitable to as many situations as possible. When it is used in a specific situation, proper revision, such as the relationship between different variables, is needed.

Figure 3.

Modified M1 after deleting pathways not statistically significant.

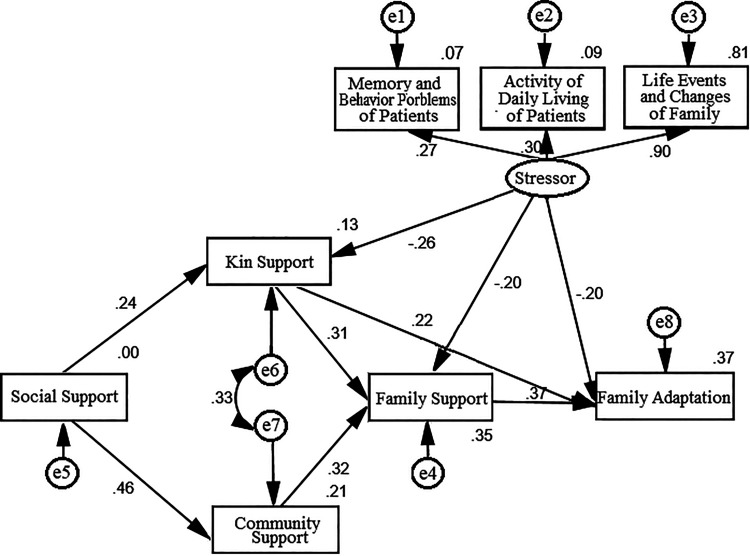

In the original hypothesis, all source of support correlated with each other, which is trouble-free but ambiguous to a specific situation. In our revision, we formed the competition model M2 based on human ecological theory and characteristics of stressors in patients’ families and Chinese culture 55 . It is explained in detail in the discussion. In this M2, N-social support influenced all the other sources of support; community support and kin support both influenced FA. The measures of model fit were as follows: χ2 of model fit/df (χ2/df) = 2.874, GFI = 0.953, AGFI = 0.888, NFI = 0.868, TLI = 0.824, CFI = 0.906, PNFI = 0.485, RMSEA = 0.096. And the relationships of social support and FA were not statistically significant (P = .728), and the modification indices suggested that there was correlationship between community support and kin support. Because these 2 suggestions were reasonable, the M2 was modified slightly and formed the final M3. The M3 fitted to the data much better. The measures of model fit were as follows: χ2 of model fit/df (χ2/df) = 1.376, GFI = 0.977, AGFI = 0.944, NFI = 0.937, TLI = 0.965, CFI = 0.981, PNFI = 0.506, RMSEA = 0.043. All indices suggest that the final model fit the data well. Figure 4 shows significant pathways of the final model.

Figure 4.

Final model (M3) with path analysis showing the direct and indirect effect of support of family on family adaptation. Each of the coefficients in the model is standard regression coefficient and exceeds P ≤ .05 significance.

As shown in the final model in Figure 4, after excluding confounding effects of stressor, FA, and kin support were direct influence factors, while community support indirectly influenced family adaptation via FA, and N-social support indirectly influenced family adaptation via kin support, FA, and community support.

Based on the final model, the path analysis values of standard direct and indirect effect of different support on family adaptation were summarized in Table 3. As shown in the table, more FA, kin support, community support, and N-social support were related to greater family adaptation. Family support was the most heavy influence factor (total effect was 0.374), followed by kin support (0.334), community support (0.250), and N-social support (0.116).

Table 3.

Path Analysis Values of Standard Direct and Indirect Effect of Different Support on Family Adaptation.

| Factors | Standard Direct Effect | Standard Indirect Effect | Standard Total Effect | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mediator variable | Value of Pathway | Total Value | |||

| Family support | 0.374 | – | – | – | 0.374 |

| Kin support | 0.216 | Family support | 0.118 | 0.118 | 0.334 |

| Community support | – | Family support | 0.121 | 0.121 | 0.121 |

| N-social support | – | Community support → family support | 0.056 | 0.137 | 0.137 |

| Kin support | 0.052 | ||||

| Kin support → family support | 0.029 | ||||

Discussion

The present study examined the support from different sources of Chinese families of patients with dementia that most heavily influences the family adaptation and the influence pathway under Chinese culture. The sample enrolled in this study was families of patients with moderate and sever dementia and adult children acting as primary caregiver. The demographic and disease-related characteristics of patients and their families were similar to the same group of family in other research. 33,56 Only the number of nuclear families of adult children involved in caring in our study was less than the number in South Africa. 33 This situation was related to the change of family size after Chinese economic development and Chinese family planning policy.

Model Modification of Pathways Among Stressor, Different Supports, and Family Adaptation

Structural equation modeling which allows for the simultaneous evaluation of all the study variables and possible pathways was used in this study. And in an effort to control the confounding effect produced by family stressors, they were involved in hypothesis model. Our final model was derived by changing pathways based on modification indices, significance of regression weights, and literature review about Chinese culture and social environment. Firstly, we deleted 4 pathways which were not statistically significant (P < .05). They were pathways between stressor and community support, stressor and N-social support, community support and family adaptation, and N-social support and family adaptation. Chinese culture which emphasizes family ethics and familism is an important reason for these results. 57,58 Family members or relatives continuously interact and mutually influence each other and regard each other as insiders while the others are outsiders. According to the definition of community and N-social support, they both are supports from outsider in Chinese culture. Even though emotional support and instrumental support provided by outsiders exist, they are not used adequately. 59,60 So, the community support and N-social support cannot influence family adaptation directly. At the same time, Chinese family has a concept called “Domestic shame should not be published.” 58 Studies have confirmed the discrimination against patients with dementia. 61 –64 Chinese families are reluctant to tell the outsiders about the stressors caused by the patients at home. So the stressor could not influence community support and social support directly.

Secondly, we revised the correlationships between different sources of supports and formed M2 based on human ecology and characteristics of stressors in patients’ families and Chinese culture. As human ecology researchers Deacon and Firebaugh have emphasized, family system is embedded in bigger ecology system and there is exchange between systems in different levels. 55 So there were influential relationships between the supports from different levels systems when we expended above theory. Then, due to the characteristics of stressors in patients’ families and Chinese culture, the main influential direction between supports from different sources existed from system to lower level system, such as N-support to community support, but cannot be reversed or bidirectional for a limited time. The characteristics of Chinese people are patience and strong will. Chinese people are more likely to rely on their own strength to overcome difficulties rather than to disturb others. 65 No matter how much the FA is, Chinese people will always try their best to rely on themselves and control burden in lower system. So, the lower systems are hard to influence systems and FA which is the nuclear system and lowest level system cannot influence others. Besides that, families of patients with moderate-to-severe dementia are confronted with a great number of stressors, and they are busy caring the patients and no attention to influence other system. The rest can be done in the same manner. The N-social support is a public, open, emerging, unrelated people or institutions provided support, and is the support provided in a wider field outside the groups of community, relatives, and family. So, N-social support was hypothesized to influence all the other sources of support. And as Xiaotong Fei have said, the community and relatives were 2 important groups of people surrounding the nuclear person. 35 There were studies that showed community support and relatives support could increase FA. 27 So, community support and kin support were hypothesized to influence FA.

Finally, because the influential pathway from N-social support to FA was not statistically significant (P = .728), and the modification indices suggested that there was correlationship between community support and kin support, we deleted the influential pathway from social support to FA and added the correlationship between kin support and community support. Firstly, we deleted the influential pathway from N-social support to FA due to the Chinese cultural psychology characteristics called hierarchical order (cha xu ge ju). 35 The sources of N-social support are farthest from family members compared to relatives and community. They have less frequent and long-term interaction with family than others. Except that, it is also because N-social support in China is rare. As shown in Table 4, N-social support possessed by family is at a low level. Furthermore, most of N-social supports are emotional supports like cultural atmosphere and the support of public opinion derived from standards of filial piety. But instrument supports provided by day care centers, respite care services, home care services, caregiver support services, and nursing homes for them are rare and cannot meet the needs of the elderly patients with dementia in China. 66 –70 And there is no family support system for families of elderly patients with dementia. 70 It is another important reason for the disappearance of direct relationship between the N-social support and FA. But the cultural atmosphere and the support of public opinion around the family, their relatives, and their community could encourage the kin support and community support, especially the latter one. Secondly, we added the correlationship between kin support and community support because kin support and community support are always related to sociodemographic characteristics of family members, such as age, educational background, and social status. 71 –73

Table 4.

Descriptive Statistic Result of Stressor, Different Sources of Support, and Family Adaptation.

| Variable | Total Score | Item Score | Skewness | Kurtosis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Min ∼ Max | M (P25, P75 ) | Min ∼ Max | Average (M/Ni) | |||

| Stressor | ||||||

| Memory and behavior problems | 0 ∼ 24 | 11 (8,17) | 0 ∼ 1 | 0.458 | 0.220 | −0.789 |

| Activity of daily living | 20 ∼ 80 | 55 (42,69) | 1 ∼ 4 | 2.750 | −0.187 | −1.008 |

| Life events and changes | 0 ∼ 67 | 8 (4,13) | 0 ∼ 1 | 0.119 | 0.810 | 0.275 |

| Different sources of support | ||||||

| Family support | 4 ∼ 28 | 23 (18, 25) | 1 ∼ 7 | 5.750 | −0.960 | 0.827 |

| Kin support | 0 ∼ 12 | 8 (6, 10) | 0 ∼ 3 | 2.000 | −0.404 | −0.225 |

| Community support | 8 ∼ 56 | 39 (29, 45) | 1 ∼ 7 | 4.875 | −0.532 | −0.484 |

| N-social support | 6 ∼ 42 | 17 (10, 26) | 1 ∼ 7 | 2.833 | 0.386 | −0.834 |

| Family adaptation | 15 ∼ 105 | 75 (61, 84) | 1 ∼ 7 | 5.000 | −0.470 | 0.175 |

The final model which provided the best fit statistically gave the most exact statement of relationships of variables. As shown in the final model of Figure 4, stressors negatively influenced the FA, kin support, and family adaptation. Having excluded the confounding effect of stressor, different sources of support still played indelible role in family adaptation.

Effect of FA and Kin Support

In the final model which was modified according to Chinese culture and social environment, more FA, kin support, community support, and N-social support were related to higher levels of family adaptation. Specifically, as shown in Table 3, FA and kin support had similar total effect on family adaptation and both were the most important influencing factors. These results have been reported in numerous studies. 24,27,29,56,74 This was also related to Chinese culture which emphasizes family ethics and familism. 57,58 The difference between FA and kin support was that the direct effect of kin support on family adaptation was not as much as it of FA. But the kin support could indirectly increase family adaptation via FA which made its total effect approximated to FA. As a great number of studies improved, support of relatives, such as assistance of housework, emotional or information support can release them more time and better capability to support the family members. Kin support is an indispensable, long-term, and more committed support. 27

Effect of Community Support and N-Social Support

When it comes to community support and N-social support, we can find from Table 3 that, they also had positive effect on family adaptation. This is agreed with a great number of studies. 27,75,76 But comparing with FA and kin support, community support and N-social support have less and indirect effect on family adaptation. The similar result was reported before as well. 27,28 This phenomenon is more obvious in China as community support and N-social support are both support from outsider. 57,58

Even though community support and N-social support are both support from outsider and had approximately the same value of standard total effect on family adaptation, the pathways of them were different. N-social was not able to increase FA directly while community support was. The sources of community support are persons (friends, neighbors, colleges, classmates, employers, and partners in organizations or teams) close to family members. They have more frequent and long-term interaction with family than social support providing organizations. 35 In recent years, as family size shrinks and number of one-child families grows, kin support is not as powerful as before 77 while community support is playing an increasing important role as a compensation. 75,76 Research has reported that the support from neighbors and friends of family member will assist to give family members more time on caregiving and support them through sharing their concerns, fears, and emotional upset. 27 Research have also reported that a friendly employer will give caregivers flexible working schedules and opportunities to take time off to be with sick relatives. 27 These supports give family member better emotional situation and more time to support each other. As a result, community support could influence family adaptation indirectly via FA. But N-social support did not have this pathway as we discussed earlier.

The aim of this research is to examine the support from different sources of Chinese families of patients with moderate-to-severe dementia that most heavily influences the family adaptation and the influence pathway. In an effort to control the confounding effect produced by family stressors, stressors which influence both different sources of support and family adaptation according to FAAR were involved in the hypothesis model. So, we also confirmed that FA and kin support were mediators through our research at the same time. As many studies have shown, the heavy burden of stressor in families of patients with dementia led to conflicts among family members and relatives, 16 –19 which reduced the FA and kin support. And the support influenced family adaptation in turn. 27,29 –34 As a result, B-social support (including FA, kin support, community support and N-support) was a mediator of stressor and adaptation. 78 –80 Still other studies have hypothesized that B-social support was a moderator of stressor and adaptation. 81 –85 Among them, there were several studies talking about caregiving process. 83,84 The results of them were mixed. When the stressor was perception, such as discrimination, 82,86 or noncatastrophic, such as taking care of elderly patient or marital adjustment, 81 moderate effect was proven to exist. But when the stressor was catastrophic, like cumulative organ damage in women with systemic lupus erythematosus 85 or taking care of relatives with Alzheimer, 84 the result will show no moderate effect or mixed. As our result shown in Table 4, caregivers of patients with moderate-to-severe dementia were confronted with a great number of stressors. And because of the disease characteristics, which are progressive, irreversible and having mood and personality changes, the stressor was continuously increasing, long lasting, and catastrophic. 1 Their influence to family adaptation is powerful and stable, which is hard to be moderated by B-social support.

Clinical Implications

Implications for clinical practice among families of patient within China emerge from the results of this study. The results suggest that in an effort to improve adaptation to heavy stressors of families of patient with dementia, future interventions should target improving different sources of support, especially FA and kin support. Several studies have shown that in families in which adult children are primary caregivers, adult children will have difficulty balancing the physical and financial needs of multiple roles, 17,19 which affected family relationships and FA. Studies of Zairt and Bangerter have also shown that most of the families have conflicts related to caregiving. 16,50 And conflicts between many adult children are mostly focused on the task of caring for the elderly and economic issues, 17,19 which seriously affect the FA and relatives’ support in the patient’s family. Interventions intended to promote FA and kinship support can be carried out by helping adult children to reasonably resolve role conflicts and promoting effective communication to reasonably distribute tasks between adult children. The above methods have also been proven to be effective in increasing support among family members. 87 –89

At the same time, according to the results of this study, community support and social support can enhance FA and kin support. Future interventions can enhance mutual help between friends, neighbors, co-workers of family members to help share the task of caring for the elderly patients and promote support within the family. It should be emphasized that the definition of community support in this study is support from friends, neighbors, colleges, classmates, employers, and partners in organizations or teams as some other studies, 27,90,91 which is not limited to people living in one particular area. It is also recommended that the State and society can further strengthen social support through making public resources (such as memory clinics, community-based services, peer support projects, etc) available and sharing family care tasks and financial burdens for families of elderly people with dementia. Recently, as online social support developing, it is also a desirable method. 92 –95

Additionally, the results also showed that FA and kin support could be damaged by stressor. Previous research also reported that more mental behavioral problems a patient with, the more disagreements and conflicts in the family. 40 The families with more stressors, which are not limited to caregiving but also come from daily life of family, need more attention and help.

Limitations and Future Directions

The major strength of our research was the use of advanced statistical modeling to examine the support from different sources of Chinese families of patients with dementia that most heavily influenced the family adaptation and the influence pathway under Chinese culture. Further strength included analysis from the view of Chinese culture and taking family as a research object.

Our research has some limitations. First, the cross-sectional nature of the study impedes causal inference to be drawn between supports of different sources and family adaption. FA and kin support could promote family adaptation and in turn family bonadaptation may enhance family functioning which includes good FA and kin support. Second, the families of this study were recruited from outpatient clinics of 4 hospitals in Beijing. The sample did not include families of undiagnosed patients and families of patients who did not take regular medication after diagnosis. Therefore, the sample of this study itself had more health beliefs and behaviors, and it was a group with better family resilience than others among the whole families of patients with moderate-to-severe dementia. At the same time, this study focused on the important advantages of the family adaptation process with certain resilience and did not include families broken down due to low resilience. Some families with extremely low resilience refused to participate in the study because of being in psychological breakdown and physical collapse. Due to the ethical principles of research, none of families was forced to participate. Therefore, the research samples in this study could not represent this kind of family.

As a result, longitudinal data on supports of different sources and family adaption should be collected in future studies in an effort to infer causal relationships between them. Besides that, future research should expand recruit sites, such as Community Health Service. In China, Community Health Services will develop a profile of patients with dementia in the future. Families recruited from Community Health Services will include the families of patients who did not take regular medication after diagnosis. If researchers could entry the families' home of older adults in the community, taking a screen of dementia, making diagnosis and recruiting participants, the sample of research will be more consistent with population of families of patients with dementia.

Conclusion

This study was conducted in families of patient with moderate-to-severe dementia. The findings from this study indicate that FA, kin support, community support, and N-social support significantly influence family adaptation among families of patients with moderate-to-severe dementia in China. It suggests that more FA, kin support, community support, and N-social support are related to greater levels of family adaptation. Specifically, FA and kin support influence family adaptation directly, while community support and N-social support influence family adaptation though FA and kin support. Family support was the most important influence factor, followed by kin support, N-social support, and community support. The results enlighten the significance of improving the FA and kin support in the families of patient with moderate and severe dementia. The interventions aiming at promoting adaptation in Chinese families of patients with moderate-to-severe dementia would likely benefit from programming or techniques focused on improving support from different sources, especially FA and kin support.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Dr Jianping Jia, Dr Xudong Li, Dr Yi Tang, Dr Zeng Wang, Dr Fengqin Gong, Dr Xinqiao Zhang, Dr Peng Li, Dr Jie Yi, Dr Meng Fan, and Lili Hu, Head Nurse Hong Chang, Head Nurse Yuchen Qiao, Head Nurse Zijian Jin, for their support and facilitation in sample recruitment. Our appreciation goes also for the staff, patients, and families from 4 hospitals at Beijing, who participated in this study.

Footnotes

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Peking Union Medical College.

ORCID iD: Qingyan Wang  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8756-3196

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8756-3196

References

- 1. American Psychiatric Association. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM 5. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2. World Health Organization. Dementia. 2018; http://www.who.int/news-room/facts-in-pictures/detail/dementia. Accessed May 8, 2018.

- 3. Wu YT, Ali GC, Guerchet M, et al. Prevalence of dementia in mainland China, Hong Kong and Taiwan: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Epidemiol. 2018. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=pubmed&dopt=Abstract&list_uids=29444280&query_hl=1. Accessed April 24, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4. Alzheimer’s Association. 2017 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2017;13(4):325–373. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1552526017300511 [Google Scholar]

- 5. Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Caregiving for person with Alzheimer’s disease or a related dementia. 2016; https://www.cdc.gov/aging/caregiving/alzheimer.htm. Accessed May 27, 2018.

- 6. Chen H, Huang M, Yeh Y, Huang W, Chen C. Effectiveness of coping strategies intervention on caregiver burden among caregivers of elderly patients with dementia. Psychogeriatrics. 2015;15(1):20–25. doi:10.1111/psyg.12071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. D’ Onofrio G, Sancarlo D, Addante F, et al. Caregiver burden characterization in patients with Alzheimer’s disease or vascular dementia. Int J Geriatr Psych. 2015;30(9):891–899. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/269187719_Caregiver_burden_characterization_in_patients_with_Alzheimer’s_disease_or_vascular_dementi. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Xu L, Zhang M, Wen Z. Family caregiver burden and stress and influencing factors in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Chinese Journal of Gerontology. 2016;36(12):3025–3027. http://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTotal-ZLXZ201612097.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chappell NL, Dujela C, Smith A. Caregiver well-being: intersections of relationship and gender. Res Aging. 2015;37(6):623–645. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=pubmed&dopt=Abstract&list_uids=25651586&query_hl=1http://europepmc.org/articles/./PMC4510280?pdf=render. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gaugler JE, Reese M, Mittelman MS. Effects of the minnesota adaptation of the NYU Caregiver Intervention on depressive symptoms and quality of life for adult child caregivers of persons with dementia. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2015;23(11):1179–1192. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=pubmed&dopt=Abstract&list_uids=26238226&query_hl=1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kahn PV, Wishart HA, Randolph JS, Santulli RB. Caregiver stigma and burden in memory disorders: an evaluation of the effects of daregiver type and gender. Curr Gerontol Geriatr Res. 2016;2016:8316045. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=pubmed&dopt=Abstract&list_uids=26941795&query_hl=1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Xian J, Tan J, Wan C, Chen M, Yu Y, Liu W. Analysis on the quality of life and influencing factors in different family life cycle residents. Chin J Behav Med Brain Sci. 2016;25(12):1118–1122. http://www.wanfangdata.com.cn/details/detail.do?_type=perio&id=zgxwyxkx201612020. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Omranifard V, Haghighizadeh E, Akouchekian S. Depression in main caregivers of dementia patients: prevalence and predictors. Adv Biomed Res. 2018;7:34. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=pubmed&dopt=Abstract&list_uids=29531932&query_hl=1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Alfakhri AS, Alshudukhi AW, Alqahtani AA, et al. Depression among caregivers of patients with dementia. Inquiry. 2018;55:1–6. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=pubmed&dopt=Abstract&list_uids=29345180&query_hl=1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Joling KJ, O’Dwyer ST, Hertogh C, van Hout H. The occurrence and persistence of thoughts of suicide, self-harm and death in family caregivers of people with dementia: a longitudinal data analysis over 2 years. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2018;33(2):263–270. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=pubmed&dopt=Abstract&list_uids=28379646&query_hl=1http://europepmc.org/articles/./PMC5811919?pdf=render. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bangerter LR, Liu Y, Zarit SH. Longitudinal trajectories of subjective care stressors: the role of personal, dyadic, and family resources. Aging Ment Health. 2019;23(2):255–262. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=pubmed&dopt=Abstract&list_uids=29171960&query_hl=1https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/13607863.2017.1402292?needAccess=true. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wong OL, Kwong PS, Ho CK, et al. Living with dementia: an exploratory study of caregiving in a Chinese family context. Soc Work Health Care. 2015;54(8):758–776. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=pubmed&dopt=Abstract&list_uids=26399493&query_hl=1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zarit SH, Femia EE, Kim K, Whitlatch CJ. The structure of risk factors and outcomes for family caregivers: implications for assessment and treatment. Aging Ment Health. 2010;14(2):220–231. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=pubmed&dopt=Abstract&list_uids=20336554&query_hl=1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mayston R, Lloyd-Sherlock P, Gallardo S, et al. A journey without maps: Understanding the costs of caring for dependent older people in Nigeria, China, Mexico and Peru. Plos One. 2017;12(8):e0182360. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?%20cmd=Retrieve&db=pubmed&dopt=Abstract&list_uids=28787029&query_hl=1http://journals.plos.org/plosone/article/file?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0182360&type=printable. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Liu S, Liu J, Wang XD, et al. Caregiver burden, sleep quality, depression, and anxiety in dementia caregivers: a comparison of frontotemporal lobar degeneration, dementia with Lewy bodies, and Alzheimer’s disease. Int Psychogeriatr. 2018;30(8):1131–1138. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?%20cmd=Retrieve&db=pubmed&dopt=Abstract&list_uids=29223171&query_hl=1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Renty J, Roeyers H. Individual and marital adaptation in men with autism spectrum disorder and their spouses: the role of social support and coping strategies. J Autism Dev Disord. 2007;37(7):1247–1255. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17080274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bishop M, Greeff AP. Resilience in families in which a member has been diagnosed with schizophrenia. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2015;22(7):463–471. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=pubmed&dopt=Abstract&list_uids=26112032&query_hl=1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gellert P, Hausler A, Suhr R, et al. Testing the stress-buffering hypothesis of social support in couples coping with early-stage dementia. Plos One. 2018;13(1):e0189849.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29300741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chan KL, Chen M, Chen Q, Ip P. Can family structure and social support reduce the impact of child victimization on health-related quality of life? Child Abuse Negl. 2017;72:66–74. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28763701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zhang H, Gao T, Gao J, et al. A comparative study of negative life events and depressive symptoms among healthy older adults and older adults with chronic disease. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2017;63(8):699–707. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29058982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. McCubbin HI, Thompson A, McCubbin MA. Family Measures: Stress, Coping and Resiliency-Inventories for Research and Practice. Honolulu, HI: Kamechamecha Schools; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Brody AC, Simmons LA. Family resiliency during childhood cancer: the father’s perspective. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2007;24(3):152–165. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=pubmed&dopt=Abstract&list_uids=17475981&query_hl=1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Coyne E, Wollin J, Creedy DK. Exploration of the family’s role and strengths after a young woman is diagnosed with breast cancer: views of women and their families. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2012;16(2):124–130. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=pubmed&dopt=Abstract&list_uids=21601525&query_hl=1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mo’Tamedi H, Rezaiemaram P, Aguilar-Vafaie ME, Tavallaie A, Azimian M, Shemshadi H. The relationship between family resiliency factors and caregiver-perceived duration of untreated psychosis in persons with first-episode psychosis. Psychiatry Res. 2014;219(3):497–505. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=pubmed&dopt=Abstract&list_uids=25017617&query_hl=1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Yeh PM, Bull M. Use of the resiliency model of family stress, adjustment and adaptation in the analysis of family caregiver reaction among families of older people with congestive heart failure. Int J Older People Nurs. 2012;7(2):117–126. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=pubmed&dopt=Abstract&list_uids=21631886&query_hl=1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Choi H. Adaptation in families of children with down syndrome: a mixed-methods design. J Korean Acad Nurs. 2015;45(4):501–512. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=pubmed&dopt=Abstract&list_uids=26364525&query_hl=1http://synapse.koreamed.org/DOIx.php?id=10.4040/Synapse/Data/PDFData/0006JKAN/jkan-45-501.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Deist M, Greeff A. Resilience in families caring for a family member diagnosed with dementia. Educ Gerontol. 2015;4(2):93–105. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/271931321_Resilience_in_Families_Caring_for_a_Family_Member_Diagnosed_with_Dementia. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Deist M, Greeff AP. Living with a parent with dementia: a family resilience study. Dementia (London). 2015;16(1):1–16. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=pubmed&dopt=Abstract&list_uids=26659440&query_hl=1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hall HR, Neely-Barnes SL, Graff JC, Krcek TE, Roberts RJ, Hankins JS. Parental stress in families of children with a genetic disorder/disability and the resiliency model of family stress, adjustment, and adaptation. Issues Compr Pediatr Nurs. 2012;35(1):24–44. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=pubmed&dopt=Abstract&list_uids=22250965&query_hl=1http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.3109/01460862.2012.646479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Fei X. From the Soil: The Foundations of Chinese Society. Shanghai, China: Shanghai People’s Publishing House; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Li D, Tian G. Growing in adversity: a case study on the family resilience of a family with an autistic child. J East China Univ Sci Technol. 2018;33(1):42–50. http://www.wanfangdata.com.cn/details/detail.do?_type=perio&id=hdlgdxxb-shkxb201801005. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Gao X. Impact Of Family Caregivers’ Burden And Family Resilience On Family Adaptation In Stroke Patients [Master Degree]. Yanbian, China: Yanbian University; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Tonnies F. Community and Society. Mineola, NY: Dover; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Chappell NL, Reid RC. Burden and well-being among caregivers: examining the distinction. Gerontologist. 2002;42(6):772–780. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=pubmed&dopt=Abstract&list_uids=12451158&query_hl=1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Yu H, Wang X, He R, Liang R, Zhou L. Measuring the caregiver burden of caring for community-residing people with Alzheimer’s disease. Plos One. 2015;10(7):e0132168. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=pubmed&dopt=Abstract&list_uids=26154626&query_hl=1http://journals.plos.org/plosone/article/file?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0132168&type=printable. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Zimet GD, Dahlem NW, Zimet SG, Farley GK. The multidimensional scale of perceived social suppor. J Pers Assess. 1988;52(1):30–41. doi:10.1207/s15327752jpa5201_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. McCubbin HI, McCubbin MA, Thompson AI, Thompson EA. Resiliency in ethnic families: A conceptual model for predicting family adjustment and adaptation. In: McCubbin HI, Thompson EA, Thompson AI, Fromer J, eds. Resiliency in ethnic minority families: native and immigrant american families. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin; 1995;1:3–48. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Antonovsky A, Sourani T. Family sense of coherence and family adaption. J Marriage Fam. 1988;50(1):79–92 https://www.researchgate.net/publication/271217162_Family_Sense_of_Coherence_and_Family_Adaptation. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Teri L, Truax P, Logsdon R, Uomoto J, Zarit S, Vitaliano PP. Assessment of behavioral problems in dementia: the revised memory and behavior problems checklist. Psychol Aging. 1992;7(4):622–631. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=pubmed&dopt=Abstract&list_uids=1466831&query_hl=1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Roth DL, Burgio LD, Gitlin LN, et al. Psychometric analysis of the revised memory and behavior problems checklist: factor structure of occurrence and reaction ratings. Psychol Aging. 2003;18(4):906–915. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?%20cmd=Retrieve&db=pubmed&dopt=Abstract&list_uids=14692875&query_hl=1http://europepmc.org/articles/./PMC2579275?pdf=render. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist. 1969;9(3):179–186. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=pubmed&dopt=Abstract&list_uids=5349366&query_hl=1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Mingyuan ZEY. Measurements for the epidemiological investigation of dementia diseases and their appication. Shanghai Arch Psychiatry. 1995;(A1):1–62 http://www.cqvip.com/qk/97872X/1995A01/1666742.html.

- 48. Curran PJ, West SG, Finch JF. The robustness of test statistics to non-normality and specification error in confirmatory factor analysis. Psychol Methods. 1996;1(1):16–29. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/262180261_The_robustness_of_test_statistics_to_non-normality_and_specification_error_in_confirmatory_factor_analysis_Psychological_Methods. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Carmines EG, McIver JP. Analyzing models with observable variables. In: Borgatta EF, Bohrnstedt GW, eds. Social measurement: current issues. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Bentler PM. Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychol Bull. 1990;107(2):238–246. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2320703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Tucker LR, Lewis C. Reliability coefficient for maximum likelihood factor analysis. Psychometrika. 1973;38(1):1–10. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/24062033_Reliability_coefficient_for_maximum_likelihood_factor_analysis. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Joreskog KG, Sorbom D. LISREL 8: User’s Reference Guide. Chicago, IL: Scientific Software International; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Bentler PM, Bonett DG. Significant tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of covariance structure. Psychol Bull. 1980;88:588–606. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/232518840_Significance_Tests_and_Goodness-of-Fit_in_Analysis_of_Covariance_Structures. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Brown MW, Cudeck R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In: Bollen KA, Long JS, eds. Testing structural equation models. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1993:136–162. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Deacon RE, Firebaugh FM. Family Resource Management: Principles and Applications. 2nd ed. Needham Heights, MA: Allyn & Bacon; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Albanese E, Lombardo FL, Prince MJ, Stewart R. Dementia and lower blood pressure in Latin America, India, and China: a 10/66 cross-cohort study. Neurology. 2013;81(3):228–235. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=pubmed&dopt=Abstract&list_uids=23771488&query_hl=1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Liang S. Outline of Chinese Culture. Shanghai, China: Shanghai People’s Publishing House; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 58. Yang G, Huang G, Yang Z. Chinese Indigenous Psychology. Chongqing, China: Chongqing University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 59. Cheng J, Zhang M, Li S, Chen Z, Shao T. Utilization of primary health services in urban and rural elderly and its influencing factors. Chin J Gerontol. 2016;36(5):1173–1175. http://d.wanfangdata.com.cn/Periodical/zglnxzz201605069. [Google Scholar]

- 60. Yeh CJ, Inman AC, Kim AB, Okubo Y. Asian American families’ collectivistic coping strategies in response to 9/11. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2006;12(1):134–148. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=pubmed&dopt=Abstract&list_uids=16594860&query_hl=1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Dai B, Mao Z, Wu B, Mei YJ, Levkoff S, Wang H. Family caregiver’s perception of Alzheimer’s disease and caregiving in Chinese culture. Soc Work Public Hlth. 2015;30(2):185–196. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?%20cmd=Retrieve&db=pubmed&dopt=Abstract&list_uids=25602761&query_hl=1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Li X, Fang W, Su N, Liu Y, Xiao S, Xiao Z. Survey in Shanghai communities: The public awareness of and attitude towards dementia. Psychogeriatrics. 2011;11(2):83–89. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?%20cmd=Retrieve&db=pubmed&dopt=Abstract&list_uids=21707855&query_hl=1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Wang Z, Gao H, Feng C, Lou F. Investigation knowledge, attitudes and practices of undergraduates on dementia. Nurs J Chin People Liberat Army. 2012;29(12):33–35. http://www.cqvip.com/qk/83642x/201212/42583829.html. [Google Scholar]

- 64. Yang H, Yang G, Cheng M, Cong J. Survey on the status and its correlation of knowledge, attitude and behaviors related to Alzheimer’s disease among community residents in Tianjin. Chin J Practical Nurs. 2013;29(32):63–67. http://d.g.wanfangdata.com.cn/Periodical_syhlzz201332027.aspxhttp://f.g.wanfangdata.com.cn/Fulltext.ashx?fileId=Periodical_syhlzz201332027&type=download&transaction=%7b%22ExtraData%22%3a%5b%5d%2c%22IsCache%22%3afalse%2c%22Transaction%22%3a%7b%22DateTime%22%3a%22%5c%2fDate(1496715740897%2b0800)%5c%2f%22%2c%22Id%22%3a%22d0f047f6-8046-4570-a606-a78a00aaeede%22%2c%22Memo%22%3anull%2c%22ProductDetail%22%3a%22Periodical_syhlzz201332027%22%2c%22SessionId%22%3a%22b4f01e7e-4b88-41a8-aa04-08059b8dff1d%22%2c%22Signatu. [Google Scholar]

- 65. Wang X, Shi M. A study of Chinese stress coping: emic and etic approach. Adv Psychol Sci. 2013;21(7):1239–1247. http://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTotal-XLXD201307011.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 66. Hu H, Wang Z. Status of are model and care resources for patients with dementia. Chinese Journal of Nursing. 2013;48(12):1136–1138. http://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTotal-ZHHL201312035.htm [Google Scholar]

- 67. Luo Y, Shi W, Xiao Y. Change trends, existing problems and countermeasures of the modes of endowment for aged urban residents-based on the survey of the modes of the endowment for the aged urban residents in Xi’an. Journal of Xi’an Jiaotong University (Social Sciences). 2013;33(1):78–84. http://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTotal-XAJD201301014.htm [Google Scholar]

- 68. Wang J, Xiao LD, He GP, De Bellis A. Family caregiver challenges in dementia care in a country with undeveloped dementia services. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2014;70(6):1369–1380. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=pubmed&dopt=Abstract&list_uids=24192338&query_hl=1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Wang J, Xiao LD, He GP, Ullah S, De Bellis A. Factors contributing to caregiver burden in dementia in a country without formal caregiver support. Aging Ment Health. 2014;18(8):986–996. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?%20cmd=Retrieve&db=pubmed&dopt=Abstract&list_uids=24679066&query_hl=1http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/13607863.2014.899976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Xu Q. Study on the care of senile dementia patients. Scientific Res Aging. 2015;3(6):40–47, 57. http://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTotal-LLKX201506006.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 71. Melchiorre MG, Chiatti C, Lamura G, et al. Social support, socio-economic status, health and abuse among older people in seven european countries. Plos One. 2013;8(1):e54856. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=pubmed&dopt=Abstract&list_uids=23382989&query_hl=1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Dai Y, Zhang CY, Zhang BQ, Li Z, Jiang C, Huang HL. Social support and the self-rated health of older people: a comparative study in Tainan Taiwan and Fuzhou Fujian province. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95(24):e3881. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=pubmed&dopt=Abstract&list_uids=27310979&query_hl=1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Conte KP, Schure MB, Goins RT. Correlates of social support in older American Indians: the native elder care study. Aging Ment Health. 2015;19(9):835–843. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?%20cmd=Retrieve&db=pubmed&dopt=Abstract&list_uids=25322933&query_hl=1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Xu L, Li Y, Min J, Chi I. Worry about not having a caregiver and depressive symptoms among widowed older adults in China: the role of family support. Aging Ment Health. 2017;21(8):879–888. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27166663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Waverijn G, Heijmans M, Groenewegen PP. Neighbourly support of people with chronic illness; is it related to neighbourhood social capital? Soc Sci Med. 2017;173:110–117. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27951461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Ellwardt L, Aartsen M, van Tilburg T. Types of non-kin networks and their association with survival in late adulthood: a latent class approach. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2017;72(4):694–705. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28329792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Song J. Only child and only child families in China. Popul Res. 2005;29(2):16–24. http://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTOTAL-RKYZ200502002.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 78. Tsai W, Lu Q. Perceived social support mediates the longitudinal relations between qmbivalence over emotional expression and quality of life among Chinese American breast cancer survivors. Int J Behav Med. 2018;25(3):368–373. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29238936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Lagdon S, Ross J, Robinson M, Contractor AA, Charak R, Armour C. Assessing the mediating role of social support in childhood maltreatment and psychopathology among college students in Northern Ireland. J Interpers Violence. 2018:886260518755489. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29448910. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 80. Xie H, Peng W, Yang Y, et al. Social support as a mediator of physical disability and depressive symptoms in Chinese elderly. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2018;32(2):256–262. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29579521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Abbas J, Aqeel M, Abbas J, et al. The moderating role of social support for marital adjustment, depression, anxiety, and stress: evidence from Pakistani working and nonworking women. J Affect Disord. 2019;244:231–238. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30173879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Steers MN, Chen TA, Neisler J, Obasi EM, McNeill LH, Reitzel LR. The buffering effect of social support on the relationship between discrimination and psychological distress among church-going African-American adults. Behav Res Ther. 2019;115:121–128. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30415761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Varona R, Saito T, Takahashi M, Kai I. Caregiving in the philippines: a quantitative survey on adult-child caregivers’ perceptions of burden, stressors, and social support. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2007;45(1):27–41. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16982103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]