Abstract

Purpose:

The interaction between 129Xe atoms and pulmonary capillary red blood cells provides cardiogenic signal oscillations that display sensitivity to precapillary and postcapillary pulmonary hypertension. Recently, such oscillations have been spatially mapped, but little is known about optimal reconstruction or sensitivity to artifacts. In this study, we use digital phantom simulations to specifically optimize keyhole reconstruction for oscillation imaging. We then use this optimized method to re-establish healthy reference values and quantitatively evaluate microvascular flow changes in patients with chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH) before and after pulmonary thromboendarterectomy (PTE).

Methods:

A six-zone digital lung phantom was designed to investigate the effects of radial views, key radius, and SNR. One-point Dixon 129Xe gas exchange MRI images were acquired in a healthy cohort (n = 17) to generate a reference distribution and thresholds for mapping red blood cell oscillations. These thresholds were applied to 10 CTEPH participants, with 6 rescanned following PTE.

Results:

For undersampled acquisitions, a key radius of was found to optimally resolve oscillation defects while minimizing excessive heterogeneity. CTEPH participants at baseline showed higher oscillation defect+low (32 ± 14%) compared with healthy volunteers (18 ± 12%, p<0.001). For those scanned both before and after PTE, oscillation defect+low decreased from 37 ± 13% to 23 ± 14% (p = 0.03).

Conclusions:

Digital phantom simulations have informed an optimized keyhole reconstruction technique for gas exchange images acquired with standard 1-point Dixon parameters. Our proposed methodology enables more robust quantitative mapping of cardiogenic oscillations, potentially facilitating effective regional quantification of microvascular flow impairment in patients with pulmonary vascular diseases such as CTEPH.

Keywords: hyperpolarized 129Xe, keyhole imaging, pulmonary microvasculature, radial MRI

1 |. INTRODUCTION

Hyperpolarized 129Xe MRI/MRS has emerged as a rapid and noninvasive tool with significant potential to simultaneously evaluate the multifactorial causes of dyspnea.1 This modality can probe not only the ventilated airspaces but also the uptake of 129Xe in the interstitial membrane tissues and transfer to the capillary red blood cells (RBCs). Although this technique provides a unique window into the membrane and capillary blood volume contributions to gas exchange, it cannot identify reduced microvascular flow originating from dysfunction in the larger pulmonary vessels.2,3 However, this microvascular flow can be characterized via cardiogenic signal oscillations arising from 129Xe atoms interacting with the pulmonary capillary RBCs.4,5 This phenomenon has been probed using whole-lung spectra, acquired every 15ms,5 that reveal the underlying temporal RBC signal dynamics. These oscillations provide a unique biomarker with the potential to detect pulmonary hypertension (PH) and whether it is precapillary or postcapillary in nature.6 Such noninvasive markers may provide utility in identifying patients who should be referred for right heart catheterization (RHC), which is the gold-standard diagnostic test for PH, but is also invasive, with nonzero associated morbidity and mortality.7 Assessment of 129Xe-derived cardiogenic oscillations is applicable, particularly in instances where current diagnostic tools8 might benefit from further corroboration or where additional pathophysiological insight is desired. Moreover, the potential to detect, characterize, and monitor PH noninvasively could also serve as a useful biomarker in clinical trials of PH therapies.

Despite their noninvasive nature, standard spectroscopic techniques for measuring whole-lung oscillations have several shortcomings. The technique requires a separate scan from gas exchange MRI, and its inability to discern spatial heterogeneity limits its diagnostic potential in differentiating certain disease conditions. For example, while patients with pure precapillary PH reliably exhibit weak RBC oscillations, and those with isolated postcapillary PH (IpcPH) show enhanced RBC oscillations,9 the situation is more complex in patients with other lung diseases. In conditions such as interstitial lung disease (ILD), in which fibrosis has destroyed significant portions of the pulmonary capillary bed, the RBC oscillation amplitudes can be enhanced, as a preserved cardiac output is being forced through a smaller vascular bed. In ILD patients who also exhibit precapillary PH, the enhanced oscillations that would normally result from vascular loss may be offset by the PH mechanisms that act to weaken RBC oscillations, resulting in whole-lung values that appear to be in the normal range.10 Similar challenges arise in patients who exhibit combined precapillary and postcapillary pulmonary hypertension (CpcPH).11

It is, therefore, necessary to move beyond simple global metrics to accurately characterize these more complex, spatially heterogeneous hemodynamics. To this end, recent studies have demonstrated that cardiogenic RBC oscillations are also detectable at the center of k-space (k0) of gas-exchange MRI scans acquired using spectroscopic imaging techniques. This observation was exploited by Niedbalski et al., who demonstrated keyhole reconstruction methods that enabled cardiogenic oscillations to be mapped regionally.12 This approach subdivides k-space views into two keys that include only projections from the peaks and troughs of the cardiac cycle. These high-key and low-key data are then inserted into the center of k-space, reconstructed into images reflecting the peak and trough of the cardiogenic oscillations, and then subtracted and normalized to construct a map of RBC oscillations.

Although keyhole image reconstruction and mapping of RBC oscillations represent an important technical development, significant work remains to make the approach robust and understand how the various preprocessing and postprocessing steps affect the resulting maps. Here, we address these questions by introducing a digital phantom to simulate regional cardiopulmonary oscillations and use it to elucidate the sensitivity of the oscillation imaging algorithm to noise, number of radial views, and key radius. We subsequently use these optimized reconstruction and quantification techniques in a well-curated cohort of healthy participants to establish an updated reference distribution and thresholds for quantitative mapping. We then evaluate the refined method in a disease in which regional microvascular flow impairment can be reversed13 by imaging patients with chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH), before and after pulmonary thromboendarterectomy (PTE) surgery.

2 |. METHODS

2.1 |. Digital phantom construction

To simulate the cardiogenic RBC oscillations in different regions of the lung, we used the MATLAB-based (Math-Works, Natick, MA, USA) Michigan Image Reconstruction Toolbox14 to create a 3D six-zone digital phantom. Each zone was modeled as a cylinder and stacked in the apical-basal direction, forming simulated left and right lungs. The cylindrical structures have analytically defined Fourier transformations, enabling rapid reconstruction with k-space data that perfectly represents the object in image space. Each zone in this digital structure had an intensity that evolved in time according to different predefined maps of oscillation amplitudes. The oscillating function was kept general to allow investigation of both sinusoidal and square-wave patterns.The oscillating phantom was radially sampled with up to 5000 radial spokes (64 points/spoke) using a 3D randomized Halton spiral pattern.15 The peak-to-peak oscillation amplitude percentage, given by

| (1) |

Was regionally varied between 0% and 20% in different lung zones. This choice of amplitude range was based on prior 129Xe dynamic spectroscopy studies that reported oscillations of 10% in healthy individuals to as high as 20% in IPF patients, and as low as 1% in pulmonary arterial hypertension patients.9 The simulation ignored longitudinal relaxation and RF-induced depolarization effects, and assumed oscillations had a spatially uniform phase.

More formally, for each zone , the signal at the time step is given by

| (2) |

where is a constant DC bias; is the oscillation amplitude; is the oscillating function; and is the oscillation frequency (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Schematic representation of a six-zone cylindrical phantom designed for simulating signal intensity oscillations. Each zone is assigned an oscillation amplitude . For each pulse TR, a single radial projection is acquired as the signal evolves according to the function . The pseudocode outlining the simulation algorithm is provided for reference.

This study sought to address the ability to spatially localize oscillation features by simulating a phantom with a single zone of oscillation amplitude “defect,” a situation that mimics lobar perfusion deficits that could be encountered in CTEPH. The code is available on GitHub.16

2.2 |. In vivo oscillation mapping methods

Guided by the digital phantom simulations, we implemented several modifications of the previously published oscillation mapping methods.12 Specifically, we introduced the following changes: First, we used a noise-tolerant peak-finding algorithm to assign the radial projections into “high” and “low” keys instead of using data normalization and thresholding; second, we replaced the keyhole radius calculation criteria of 50% sampling at the edge of the keyhole with one optimized by simulations; and third, we normalized the oscillation amplitude at a given voxel on a voxel-by-voxel basis.

Each radial view was evaluated for inclusion into the high or low keys using the find_peaks function from the SciPy package17 using the time-dependent one-dimensional RBC signal at . Specifically, peaks were identified within a minimum distance of where the heart rate was determined using the largest Fourier component of and , a parameter determined empirically for best performance. This approach ensured that only peaks separated by a substantial fraction of the cardiac cycle were identified, preventing noise from being misinterpreted as true physiological signals. We refer readers to the exact algorithm in the code released.

The amplitude in a given voxel following voxel-wise normalization was given by

| (3) |

where the variable definitions are the same as those of Niedbalski et al.12 Scaling the oscillation difference map using the voxel-wise image intensity obtained using all the available data is more appropriate than the original method of dividing by the mean image intensity. Further details are provided in Section 4.

To characterize the effect of SNR on recovered oscillation maps,the underlying k-space data were systematically degraded by adding Gaussian noise. Although noise was added in the k-space domain, its effect on image-domain SNR was estimated using reconstructions of our uniform digital phantom consisting of two cylinders. The effect of image-domain SNR on the accuracy of oscillation amplitude recovery was then evaluated by measuring the mean squared error (MSE) between reconstructed oscillation images and the ground truth.

2.3 |. Participant recruitment

The Institutional Review Board of Duke University Medical Center approved this study. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant before recruitment. To build a reference cohort, scans from n = 24 healthy participants (16 males, 8 females between ages 18–30) with no smoking history or known respiratory or cardiac conditions were retrospectively analyzed. These participants were curated by requiring their diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide to exceed at least 80% of the reference value18 and a minimum RBC SNR of 1.5. This led to a final reference cohort of n = 17 (11 males, 6 females) with height 1.7 ± 0.1 m and weight 78.6 ± 13.1kg. An additional cohort of 10 participants (mean age, 52 ± 17years; 4 females) with CTEPH were prospectively recruited to test the value of regional microvascular flow imaging.The CTEPH cohort under went RHC to determine their PH status (no PH, precapillary, IpcPH, or CpcPH) with in 8 months of the 129Xe MRI and MRS exam.This was determined using the mean pulmonary artery pressure (mPAP), pulmonary capillary wedge pressure (PCWP), and pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR). Specifically, PH is now defined as mPAP ≥ 20mmHg, whereas precapillary PH required PCWP ≤ 15mmHg and PVR ≥ 2 wood units (WU), and IpcPH required PCWP >15mmHg and PVR <3 WU.19,20 Patients with PVR>2 WU and PCWP >15mmHg were identified as CpcPH.21

2.4 |. 129Xe gas hyperpolarization and MRI/MRS acquisition

129Xe was hyperpolarized via continuous flow spin-exchange optical pumping and cryogenically accumulated using commercially available systems (Models 9820 and 9810; Polarean, Durham, NC, USA). The dose was then dispensed into a Tedlar bag22 for administration. Twenty participants (10 healthy, 10 CTEPH) received a standard total gas volume of 1 L, and the remaining participants received a gas volume tailored to 20% of their forced vital capacity as per the 129Xe MRI Clinical Trials Consortium–recommended protocol.15 Participants received a small dose for calibration and spectroscopy (dose equivalent = 71 ± 22 mL). Here, the dose equivalent is the theoretical volume of pure, 100% hyperpolarized 129Xe that would produce the same bulk magnetization as the dose being sampled. Participants then received a larger dose for the gas exchange imaging scan (target dose equivalent ≥150mL; actual dose: mean, 158 ± 4 mL).

129Xe spectroscopy and imaging were acquired on a 3T Siemens MAGNETOM Trio or Prisma scanner during two separate breath-holds.15 For each scan, participants were coached to inhale the 129Xe from functional residual capacity in the supine position.

2.5 |. Quantitative and statistical analysis

All image preprocessing, reconstruction, and analyses were performed in Python except for simulating the phantom data, which used the Michigan Image Reconstruction Toolbox in MATLAB 2022a. Images were reconstructed to a matrix of 128×128×128 voxels using iterative density compensation and nonuniform fast Fourier transform methods.23,24

To visualize the effect of acquisition and keyhole reconstruction parameters, the digital phantom was simulated with both sinusoidal and square wave oscillation functions, varying three specific parameters: (1) radial views between 1000 and 5000, (2) between 1% and 18% points out of a 64-point projection, and (3) image SNR by the addition of Gaussian noise to both real and imaginary channels of the simulated k-space data. Because SNR is more commonly reported for the image domain, it was related to the k-space SNR using a uniform, nonoscillating digital phantom. The image noise was quantified by the SDs across sliding, non-overlapping 8×8×8 windows. Thus, the image SNR was calculated as

| (4) |

where the mean signal was that within the phantom/thoracic cavity mask, and the noise was that outside the phantom/thorax. The phantom mask can be trivially calculated using thresholding, whereas thoracic cavity masks for in vivo images were produced using a V-net-based convolutional neural network.25,26

Oscillation images were rendered into color maps via linear binning based on the healthy cohort distribution as described in applications for conventional gas exchange MRI.27,28 However, regions where the SNR of the non-keyhole RBC images fell below the computed noise level (the denominator in Eq. [4]) were excluded from analysis and depicted as gray voxels. Binning thresholds were determined by applying a Box-Cox transformation to the healthy cohort distribution to calculate its mean and SD; these were used to establish image binning thresholds in intervals of one SD away from the mean. The thresholds were then inverse-transformed and used to map regional cardiogenic oscillation amplitudes.28,29

The RBC oscillation amplitude maps were quantified using the mean oscillation percent, as well as their combined percentage of lung voxels classified as defect or low using the binning scheme. These metrics were compared between the CTEPH and healthy cohorts (Mann–Whitney U-test) as well as for the CTEPH patients before and after surgery (paired two-sided Wilcoxon signed-rank tests). Statistical tests were conducted in R and plotted using the ggstatsplot package.30

3 |. RESULTS

3.1 |. Phantom simulations

Figure 2 illustrates the effects of radial undersampling using reconstructions of a simple two-sided phantom designed with oscillation amplitudes of 0% in Zone 1 and 20% in Zones 2–6, respectively. Reconstructions consisting of 5000, 2000, and 1000 radial views were considered. Compared with the ground-truth image, the histogram of the 5000-radial view reconstructed image shows the oscillations in Zone 1 to be shifted higher than their specified 0%, but those in Zones 2–6 accurately reflect the specified 20%.The applied oscillation pattern is reasonably recapitulated by the reconstruction. As the number of radial views is reduced to 2000, as used in a “fast” Dixon sequence,31 the oscillation histogram broadening becomes more severe, and heterogeneity in the resulting map is increased. These findings become even more severe for the 1000 views used in the current consortium protocol.15 Notably, although two distinct oscillation levels are still readily detected in all three scenarios, the major peaks become substantially shifted toward lower values than those prescribed in the phantom as the number of views is decreased. These effects are readily seen in the coefficient of variation of the oscillation amplitudes, which were [0.27, 0.39, 0.57] for the [5000, 2000, and 1000] radial view reconstructions, respectively.

FIGURE 2.

Effect of the number of radial views illustrated in a digital phantom with prescribed (“ground truth”) oscillation amplitudes of 0% in Zone 1 and 20% in Zones 2–6. As the number of radial views used for reconstruction decreases, the apparent heterogeneity of the oscillations increases. In all but the 5000 radial view case, the peak value in Zones 2–6 identified exhibits a shift toward lower values.

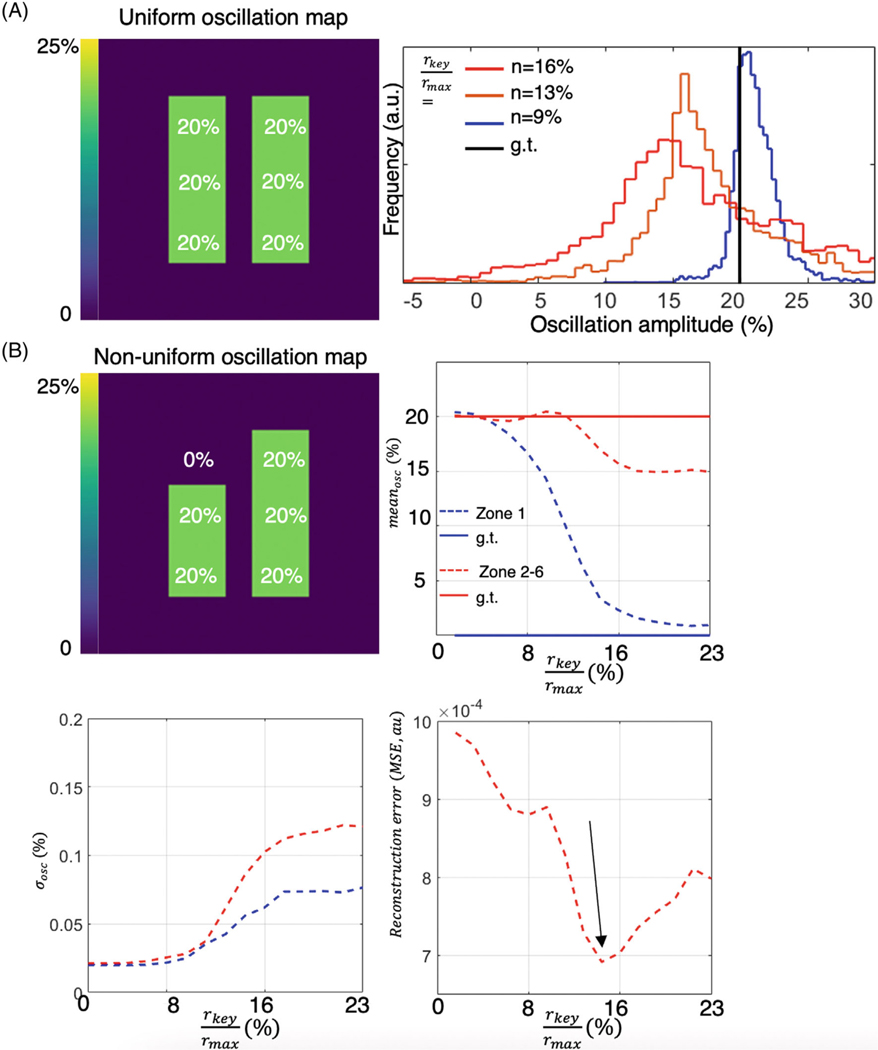

Oscillation amplitude heterogeneity was also strongly affected by the choice of key radius used in reconstruction. This is illustrated in Figure 3A, depicting a phantom with a uniform oscillation amplitude of 20% in all regions, sampled with 2000 radial views. As the ratio of key radius to is reduced from 18% (calculated using a 50% sampling criterion) to 10%, the width of the oscillation map histogram narrows and approaches the prescribed value. However, as shown in Figure 3B, with oscillations set to 0% in Zone 1, the ability to detect a “defect” is also affected by the choice of key radius. At lower key radii, the oscillation defect in Zone 1 is indiscernible, exhibiting a recovered mean oscillation amplitude that essentially matches that of Zones 2–6. However, as the key radius increases, the spatial resolution of the recovered maps improves such that the oscillation amplitude in Zone 1 approaches its true value of 0%. Nevertheless, increasing the key radius simultaneously elevates the SD of the recovered oscillation histogram. This trade-off can be summarized by the overall MSE metric, which reaches a minimum at a key radius percentage that is 14% of .

FIGURE 3.

(A) Effect of key radius on a phantom with uniform 20% oscillations sampled using 2000 radial views (black line represents ground truth). When using a key radius percentage of 5% (7/128 points), the oscillation histogram remains sharp and well-centered near 20%. As the key radius is increased, the histogram broadens and shifts to lower values. (B) Analysis of a nonuniform oscillation map with Zone 1 prescribed to have 0% oscillations versus 20% in Zones 2–6. As the key radius increases, the recovered mean oscillation level in Zone 1 converges to its prescribed value of 0%. However, increasing the key radius also increases the SD of the oscillation histograms in all zones. Thus, the ability to detect small defects through reconstruction with a large key radius must be balanced against the ability to distinguish variations in oscillation with a small key radius.

Figure 4A illustrates the ways in which the reconstructed oscillation maps are affected by SNR. As SNR decreases, it influences the accuracy with which individual k-space rays are sorted into the high and low oscillation keys. These effects were quantified using the MSE between the recovered maps and the ground truth, as seen in Figure 4B. Increasing SNR decreased the MSE reconstruction error. Specifically, as SNR increased from 5 to 10, the MSE decreased 10-fold. A similar trend was also observed in the Zone 1 oscillation amplitude “defect.” In general, it remained possible to observe a qualitative distinction between oscillation amplitudes in Zone 1 versus Zones 2–6 for SNR values greater than 3.

FIGURE 4.

Effect of SNR on recovered red blood cell (RBC) oscillation amplitudes. (A) Visual examples of reconstructed cardiopulmonary oscillation maps with varying levels of SNR. (B) Spatial differences between the oscillation maps derived from images of infinite SNR versus various levels of degradation were quantified using the mean squared error as a function of RBC image SNR. (C) Recovery and visualization of oscillation amplitude heterogeneity (10% in Zones 1–3, 20% in Zones 4–6) using colormap binning. (D) Comparison of RBC oscillation histograms at the high and low SNR levels used in (C) indicates negligible increase in oscillation defects <0% when SNR is decreased.

Finally, Figure 4C depicts a realistic scenario of sinusoidal oscillations of 10% in Zones 1–3 and 20% in Zones 4–6, sampled with 2200 radial projections31 and displayed by binning into colormaps. Here, the binning technique demonstrates that oscillation amplitudes on the right side of the phantom are high, whereas those on the left side remain in the normal range. This can be seen at both an SNR of 3 and infinity. However, in each case, the oscillation patterns exhibit significant heterogeneity and do not capture the uniformly high oscillations specified by the ground truth. This is the result of fewer projections being assigned to the high and low keys, thus contributing to significant undersampling artifacts. Figure 4D displays the histograms of RBC oscillation patterns under this same scenario. Notably, the histogram SD was 5% for SNR = 3 and only marginally increased to 6% for the idealized SNR.

3.2 |. In vivo imaging

The effect of the key radius was also found to be critical to improving the robustness of RBC oscillation amplitude mapping in vivo. This is illustrated by oscillation maps reconstructed from a healthy subject (Figure 5); these maps are displayed using an 8-bin color scale with thresholds set in 1-SD increments based on the previously published healthy reference distribution. When oscillation maps were reconstructed using a key radius of , the apparent oscillation defect percentage was 29.1% (red). In contrast, when reconstructed using the key radius of informed by the simulations, the images had a morehomogeneousappearance,andthedefectpercentage was reducedto0.3%. Moreover,whilebothreconstructions show an anterior–posterior gradient in high amplitude percentage (top 3 pink/purple bins), using a key radius of reduced the percentage of high amplitude oscillations from 23.4% to 5.8%; notably, such high oscillations were confined primarily to the gravitationally dependent posterior lung. Similar effects were seen when these key radii were tested in all subjects in the healthy cohort, as each subject exhibited a more homogeneous pattern with fewer oscillation amplitude defects.

FIGURE 5.

Importance of using an optimal key radius, demonstrated in a healthy subject binned to an 8-bin colormap. The maps at the top of the figure were reconstructed with a key radius (12/64), calculated using the published approach such that the number of binned projections provides 50% sampling at the edge of the keyhole. However, these maps exhibit considerable heterogeneity in this healthy volunteer. Instead, reconstructing with a key radius of (9/64), empirically determined from the described phantom simulations, removes the spurious heterogeneity and reveals a relatively homogeneous pattern more consistent with that expected for a subject without known disease. D-defect; L-low; H-high.

Figure 6 shows a histogram of the RBC oscillation amplitude distribution acquired from the 17 healthy participants reconstructed with a fixed key radius . This cohort had an RBC transfer image SNR of 7.9 ± 5.5. The resulting combined distribution is right-skewed and non-Gaussian; therefore, a Box-Cox transformation was used to calculate appropriate binning thresholds that could be used for mapping. The mean and SD (4.09 ± 3.78%) of the resulting distribution were used to generate binning thresholds that were subsequently inverse-transformed and used for mapping(Table 1). Compared with using the simple Gaussian mean and SD, this approach led to the Bin 1 threshold shifting from −3.5% to −2.0%, whereas Bins 6 and 7 increased from 15.4% to 21.1% and 19.2% to 36.5%, respectively. Application of these bins to generate oscillation amplitude maps is also shown for a healthy subject who exhibits a relatively homogeneous oscillation map (0% binned defect, 1% binned low, 0% binned high). This same reconstruction and binning approach were thus used for all subsequent analyses.

FIGURE 6.

(A) Combined reference distribution and thresholds constructed from 17 healthy, young participants (ages 18–30) with normal pulmonary function tests. (B) Example red blood cell (RBC) oscillation colormaps of a healthy participant using the binning technique.

TABLE 1.

Comparison of 8-bin thresholds of red blood cell (RBC) oscillation amplitudes assuming a Gaussian distribution versus using a Box-Cox transformation. Values were determined based on increments of 1 SD from the mean and displayed as percentages.

| Method | Bin 1 (%) | Bin 2 | Bin 3 | Bin 4 | Bin 5 | Bin 6 | Bin 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gaussian | −3.5 | 0.3 | 4.1 | 7.9 | 11.7 | 15.4 | 19.2 |

| Box Cox | −2.0 | 0.4 | 3.7 | 7.6 | 13.0 | 21.1 | 36.5 |

Figure 7 shows the RBC transfer and RBC oscillation amplitude maps from a CTEPH patient before and after PTE surgery. This patient had combined CpcPH based on RHC values (mPAP = 43mmHg, PCWP = 17mmHg, PVR = 6.5 WU) and exhibited a mean global RBC oscillation amplitude of 6.7% at baseline from dynamic spectroscopy.32 Viewed in isolation, this “normal” oscillation amplitude would seem to classify the subject as not having PH.6 However, an inspection of the spatial distribution of oscillations revealed a large percentage of voxels with oscillations in both the defect and low bins (30% vs. 7 ± 8% reference) and in the high bins (23% vs. 4 ± 4% reference). After PTE, the combined defect and low percentage decreased to 0.8%, whereas the high percentage decreased only slightly to 19.5%. Notably, however, this participant’s RBC transfer image continued to show impairment as evidenced by RBCdefect+low = 52%. This patient’s surgical report indicated significant segmental disease (San Diego level III)33 in the right middle and lower lobes. Segmental disease was also encountered in the left lower lobe with webs and plugs.

FIGURE 7.

129Xe MRI red blood cell (RBC) transfer and RBC oscillation imaging for a representative chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH) patient with combined precapillary and postcapillary pulmonary hypertension (PH). RBC transfer maps show significant regions of defect at baseline that are relatively unchanged after pulmonary thromboendarterectomy (PTE) surgery. RBC oscillation maps, however, indicate regions of both decreased and increased oscillation (arrows). After PTE surgery, the areas of decreased oscillation are resolved while only high oscillations remain, indicating persistent postcapillary PH. D-defect; L-low; H-high.

In aggregate, participants with CTEPH at baseline (Figure 8) exhibited lower mean RBC oscillation amplitudes (3 ± 2%) than healthy volunteers (5 ± 3%, p <0.001) and a higher percentage of voxels falling in the defect + low bins (32 ± 14% vs. 18 ± 12%, p <0.001). In CTEPH participants who underwent PTE, oscillation defect+low decreased from 37 ± 13% to 23 ± 15% (p = 0.03). However, the difference in mean oscillation amplitude was not statistically significantly different before and after PTE, nor did the the mean RBC transfer appreciably change before and after PTE (0.25 ± 0.07 vs. 0.21 ± 0.05, p >0.05).

FIGURE 8.

Comparison of metrics obtained from red blood cell (RBC) oscillation maps in the healthy cohort versus patients with chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH) mean oscillation amplitudes (A) and percentage of voxels binned as defect + low (B) both differentiate healthy and participants with CTEPH (p<0.001). For CTEPH participants who underwent pulmonary thromboendarterectomy (PTE), mean oscillation amplitude did not exhibit a statistically significant change (C), but percentage of defect+low voxels decreased in all participants (p = 0.03) (D).

4 |. DISCUSSION

4.1 |. Phantom simulations: Radial undersampling

Using a digital phantom to simulate signal intensity oscillations enabled both validating the feasibility of imaging cardiogenic amplitude oscillations in the 129Xe-RBC signal, while also uncovering the limitations of the method. Such simulations provide a better understanding of the technical factors that affect the ability to recover such oscillation images in vivo—a process that is particularly affected by radial undersampling. For acquisitions consisting of only 1000 radial views, the resulting distribution of amplitude oscillations shows about 1% of voxels to reflect negative values (below 0%). Although such “negative” oscillation amplitudes are not physiologically realistic, the simulations show that they are caused by undersampling, which has the effect of broadening the observed distribution relative to ground truth. Furthermore, simulations of 1000 and 2000 radial projections demonstrate that the observed histogram peaks are decreased by about 5 percentage points relative to the prescribed ground-truth values. Despite this, the general pattern of applied oscillation amplitude heterogeneity can still be recovered, albeit with poor spatial fidelity. The fidelity of recovered oscillation maps was improved when the number of radial views was increased to 2000, such as used in “fast” Dixon imaging.31 Nonetheless, the recovered oscillation amplitude values are still broadened and lower than the ground truth. As the number of radial views reaches 5000, the maps and histograms resemble the applied values more closely. However, the 0% mode in the histogram increases by 5 percentage points from the ground truth, whereas the 20% mode in the histogram remains at 20%. These deviations from ground truth result from keyhole reconstruction being unable to capture the complete high-frequency content and necessary contrast required to accurately represent the oscillation dynamics. In other words, the outer k-space region still encodes the image contrast, but these contributions are equally mixed into the “high” and “low” key reconstructions. In the context of a bimodal phantom with distinct oscillation amplitudes, this mixing can result in a shift of the two peaks in the distribution closer to each other. Instead of clearly being separated into high and low oscillation amplitudes, the reconstructed images may exhibit the underly spatial heterogeneity, but represent it with poor spatial fidelity. Importantly, however, for a purely homogeneous phantom, the recovered maps tend to recover that homogeneity faithfully.

4.2 |. Phantom simulations: Key radius

Investigations of how key radius affects the reconstruction of oscillation amplitude maps in a heterogeneous phantom showed that the use of a smaller key radius impairs the detection of oscillation “defects.” For example, when using a small key radius for reconstruction, the oscillation defect in Zone 1 is not apparent, and its recovered mean oscillation amplitude is essentially equal to that from Zones 2–6. Increasing the key radius improves the spatial resolution of the recovered maps, allowing the oscillation amplitude to approach its true value of 0%, and revealing the defect in Zone 1. However, increasing the key radius also introduces greater heterogeneity, indicating a trade-off between spatial resolution and the dispersion of oscillation amplitude values. Here, the simulations suggest the MSE of the recovered versus ground-truth maps is minimized at a key radius percentage of 14%. Therefore, this key radius was chosen for all reconstructions going forward.

4.3 |. Phantom simulations: Effect of SNR

Unsurprisingly, the robustness of keyhole reconstructed RBC oscillation maps is affected by image SNR. Higher SNR led to lower reconstruction errors, resulting in more accurate spatial maps of cardiopulmonary oscillations. In contrast, in low-SNR acquisitions, classifying the radial projections as belonging to either the “high” or “low” keys became increasingly more challenging. This was addressed by modifying the algorithm used to assign radial rays to the high or low keys to detect only peaks and troughs that were consistent with the estimated heart rate obtained from taking the largest frequency component in the spectrum of the RBC k0 data. For future work, this type of projection classification may also become possible by incorporating conventional physiological monitoring.34

By systematically assessing SNR values in simulations, we found that an RBC image SNR of at least 3 is needed to reliably visualize significant defects. At lower SNR values, oscillation amplitude heterogeneity can still be detected, but its spatial distribution becomes less reliable. This is also evident when the maps are displayed using the 8-bin colormap. Even at a modest SNR of 3, the oscillation maps could demonstrate normal oscillations in Zones 1–3 and increased values in Zones 4–6. However, the precision with which the spatial pattern of the ground truth phantom could be recovered was modest. Furthermore, analysis of the corresponding oscillation histograms showed no broadening of the RBC oscillation histogram at lower SNR.

4.4 |. Oscillation amplitude calculation

Notably, this work identified a correction to the voxel-by-voxel calculation of oscillation amplitudes. Although the previously published approach normalized the high-key and low-key images by the mean RBC transfer across the whole lung, we suggest that it should be normalized based on voxel-wise RBC transfer. This accounts for the difference between the high-key and low-key images in each voxel being affected, not only by the associated oscillation amplitude, but also by the level of RBC transfer within it. Thus, by normalizing on a voxel-by-voxel basis, the effects of spatially varying RBC transfer are removed, and the remaining differences between low and high keys are reliably attributable to RBC amplitude oscillations. When normalizing by the mean RBC transfer, regions with low RBC transfer may be underrepresented or masked by the effects of higher RBC transfer areas in the lung. Consequently, this could lead to an underestimation of oscillation amplitudes in these low RBC transfer regions, potentially obscuring meaningful physiological differences.

4.5 |. Cardiogenic oscillation imaging in healthy participants

Effective interpretation of RBC oscillation maps requires establishingappropriate thresholdsbycharacterizing their distribution in a healthy reference population. This work used a more carefully curated reference cohort than previously published. Specifically, subjects were excluded if their diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide was less than 80% of reference or if image SNR did not meet the necessary thresholds. The resulting aggregate oscillation histogram was found to have a distribution with a tail extending more to the right, consistent with expectations that oscillation amplitudes are greater than zero. To accommodate such a non-Gaussian distribution, a Box-Cox transformation was applied that notably increased the lower thresholds for classifying oscillation amplitudes and thus conferred higher sensitivity for voxels to be classified as “defect.” This framework may thus better separate participants with true oscillation defects (such as those with regions of precapillary PH) from those without.

Moreover, these improvements in forming the reference distribution served to substantially decrease its SD (3.8%) compared with the previously reported 9.0%.12 This narrower reference distribution allows for more accurate analysis and comparison, as it confers greater sensitivity to subtle abnormalities presenting as either high or low oscillations. Notably, the use of these oscillation mapping methods continued to reveal a prominent anterior–posterior gradient in healthy participants consistent with that previously reported by Niedbalski et al.12

The mean oscillation amplitudes obtained in our study were found to be lower than those reported in previous studies using dynamic spectroscopy methods. This discrepancy is consistent with the results obtained from our digital phantom simulations, which indicate that radial undersampling shifts the recovered histogram downward.

4.6 |. Cariogenic oscillation imaging in CTEPH participants

The potential of the updated keyhole reconstruction methods in this work is particularly evident when applied to patients with CTEPH. Here, the ability to spatially localize regions of low oscillations combined with conventional RBC transfer imaging could provide a new means to phenotype patients. Although CTEPH is a form of precapillary PH that can, in principle, also be detected using simple whole-lung 129Xe spectroscopy,5 9 spatial mapping potentially permits the identification of specific lobes and segments that are affected by chronic clotting. This was illustrated in the case example where in oscillation imaging findings were largely consistent with the surgical report indications of segmental disease in the right middle and lower lobes. However, we found only minimal evidence of reduced oscillations in the left lower lung, possibly due to the lesser extent of disease also noted in the surgical report.

CTEPH patients exhibited a greater percentage of regions with oscillations in the defect + low category. Such regions of decreased oscillation amplitude are likely caused by thrombi increasing the impedance to flow in the larger vessels and arterioles.35 For CTEPH participants who underwent PTE, the percentage of defect + low voxels decreased in all patients. This suggests that RBC oscillation imaging may provide a view of regional, periodic changes in pressure and flow. In contrast, conventional RBC transfer images (reconstructed from the same data, SNR 2.3 ± 1.0) provide a complementary view of pulmonary microvascular blood volume. This combined capability may offer a means to better predict outcomes for patients considered for PTE. It is also noteworthy that the mean RBC oscillation percentage did not change significantly after surgery. There could be several reasons for this outcome. It is possible that the number of participants included in the study was not large enough to detect a statistically significant difference. Alternatively, it might suggest that there is a redistribution of blood flow after surgery, whereas before PTE, healthy parts of the lung receive excess blood flow (high oscillations) that normalizes after surgery.

The most striking capability of producing regional cardiogenic oscillation maps is being able to identify participants with potential combined precapillary and postcapillary pulmonary hypertension (CpcPH). This was illustrated by a CTEPH patient, in whom whole-lung oscillation amplitudes were in the normal range and thus would be classified as having no PH based on the previously published evaluation algorithm for 129Xe MRI/MRS.10 However, this subject had both precapillary PH due to the thrombi and postcapillary PH from other origins, and these effects competed to produce a global average oscillation amplitude that appeared normal. However, by spatially resolving the oscillations, it becomes possible to reveal the presence of both precapillary and postcapillary PH in different lung regions. Notably, after this patient underwent endarterectomy, global oscillations increased, and only regions of high oscillation remained visible on the spatially resolved maps. Thus, by using RBC oscillation imaging, such cases of CpcPH may be more accurately characterized.

4.7 |. Study limitations and opportunities for refinement

Although these advances in examining regional cardiogenic oscillations in the HP 129Xe signal dissolved in RBCs show promise, we must acknowledge some of the limitations of our study. The simulations did not account for the complexity of separating the dissolved-phase signals into RBC and membrane compartments. This simplification may not fully capture the intricate dynamics of gas exchange and transfer, potentially affecting the accuracy of our oscillation amplitude maps. Furthermore, although these simulations provide valuable insights toward achieving more optimal keyhole reconstruction and analysis, it is evident that radial undersampling significantly affects the effectiveness of this approach. This limitation may require revisiting the current Xenon Clinical Trials Consortium–recommended 1-point Dixon acquisition using only 1000 radial-views, which suffers from significant radial undersampling artifacts. Specifically, this approach leads to a small number (~200) of projections being incorporated into the “high” and “low” keys. It is therefore recommended that Dixon images be acquired using an accelerated method31 to provide a maximum number of views for keyhole reconstruction.

For future work, it is possible to explore the use of 3D tiny golden angle trajectory36 to cover k-space more uniformly during each cardiac cycle. It may also be advantageous to explore other reconstruction methods such as compressed sensing37 or deep-learning38 that are well-suited to recovering high-quality images from heavily undersampled data sets. Moreover, using dynamic spectroscopy with multichannel receive coils presents a promising avenue of providing modest localization of oscillations without the types of artifacts that affect the key-hole approach used here.39 Future work would benefit from the incorporation of additional relevant demographic/clinical information, such as fingertip optical hemoglobin measurements,40 age,41 weight, and height, into the reference distribution. Although this work demonstrated that RBC oscillation heterogeneity is prevalent in patients with CTEPH and improved by PTE surgery, the spatial accuracy with which regions of low RBC oscillations can be localized remains unclear. To this end, future work should include comparing our method to more established imaging techniques such as 3D SPECT perfusion imaging,12 ultrasound,42 and other gold-standard hemodynamic measurements. Given the unique advantages of each approach, a combined use might offer more robust insights into the complex pathophysiology of pulmonary hypertension.

It should be noted that the curated healthy cohort used to establish reference distributions was younger than the CTEPH cohort. Although Niedbalski et al. observed no substantial age-dependent alterations in oscillation metrics,12 Mummy et al.43 suggested a mild increase in oscillations with age. Consequently, observing reduced oscillations in older individuals might serve as a more pronounced indicator of underlying abnormalities. Thus, the younger reference cohort used here would potentially have reduced sensitivity to disease-related changes.

5 |. CONCLUSIONS

RBC oscillation imaging using keyhole reconstruction is emerging as a potentially powerful tool to provide a picture of microvascular flow that complements the image of capillary blood volume. This level of regionality is particularly valuable for evaluating the regional effects of pulmonary hypertension. However, oscillation maps are sensitive to many factors, including undersampling, the method of assigning radial projections to high or low keys, keyhole radius, normalization, and overall SNR of the RBC transfer image. This work has addressed these factors and proposes several changes to the oscillation mapping technique that improve robustness. Applying these methods to the curated healthy cohort yielded a narrower healthy reference distribution than previously published, which we expect will improve sensitivity for detecting regional changes in oscillation amplitude. In addition, applying this approach to CTEPH participants permitted visualization of low and absent oscillations. These regions improved after PTE, consistent with a positive change in patient status after endarterectomy. Such improved imaging of RBC oscillations has the potential to address current limitations of PH detection using whole-lung dynamic spectroscopy.10 More specifically, the presence of CpcPH or PH in the setting of ILD confounds current dynamic spectroscopy diagnostic models due to competing effects that suppress and enhance the RBC oscillations.10 Thus, applying robust cardiopulmonary oscillation mapping could significantly enhance the power of 129Xe gas exchange MRI to detect and monitor a wide range of PH.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors acknowledge the contributions of their clinical research coordinators Jennifer Korzekwinski and Cody Blanton (Department of Medicine, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC, USA) and data manager Shuo Zhang (Department of Radiology, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC, USA).

FUNDING INFORMATION

National Institutes of Health/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (R01HL105643, R01HL12677, R01HL153872, NSF GRFP DGE-2139754), American Heart Association Career Development Award 930177, and Scleroderma Foundation New Investigator Award.

Funding information

American Heart Association, Grant/Award Number: 930177; NIH, Grant/Award Numbers: R01HL105643, R01HL12677, R01HL153872; NSF, Grant/Award Number: GRFP, DGE-2139754; Scleroderma Foundation New Investigator Award

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Bastiaan Driehuys holds unsold intellectual property, royalties, and stock/stock options, and serves as a board member for Polarean Imaging. Peter Niedbalski and David Mummy serve as consultants for Polarean.

REFERENCES

- 1.Grist JT, Chen M, Collier GJ, et al. Hyperpolarized (129)Xe MRI abnormalities in dyspneic patients 3 months after COVID-19 pneumonia: Preliminary results. Radiology. 2021;301:E353–E360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barratt S, Millar A. Vascular remodelling in the pathogenesis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. QJM. 2014;107:515–519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mathew Roshin C,Bourque JM, Salerno M, Kramer CM. Cardiovascular imaging techniques to assess microvascular dysfunction. JACC: Cardiovascular Imaging. 2020;13:1577–1590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Freeman MS, Cleveland ZI, Qi Y, Driehuys B. Enabling hyper-polarized 129Xe MR spectroscopy and imaging of pulmonary gas transfer to the red blood cells in transgenic mice expressing human hemoglobin. Magn Reson Med. 2013;70:1192–1199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bier EA, Robertson SH, Schrank GM, et al. A protocol for quantifying cardiogenic oscillations in dynamic (129) Xe gas exchange spectroscopy: The effects of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. NMR Biomed. 2019;32:e4029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bier E. Noninvasive diagnosis of pulmonary hypertension with hyperpolarized 129Xe magnetic resonance imaging and spectroscopy. ERJ Open Res. 2022;8:35–2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoeper MM, Lee SH, Voswinckel R, et al. Complications of right heart catheterization procedures in patients with pulmonary hypertension in experienced centers. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48:2546–2552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rubin L, Hopkins W. Clinical features and diagnosis of pulmonary hypertension of unclear etiology in adults. In: Post TW, ed. UpToDate. UpToDate; 2023.

- 9.Wang Z, Bier EA, Swaminathan A, et al. Diverse cardiopulmonary diseases are associated with distinct xenon magnetic resonance imaging signatures. Eur Respir J. 2019;54:1900831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bier EA, Alenezi F, Lu J, et al. Noninvasive diagnosis of pulmonary hypertension with hyperpolarised (129)Xe magnetic resonance imaging and spectroscopy. ERJ Open Res. 2022;8:35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ibe T, Wada H, Sakakura K, et al. Combined pre- and post-capillary pulmonary hypertension: The clinical implications for patients with heart failure. PloS One. 2021;16: e0247987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Niedbalski PJ, Bier EA, Wang Z, Willmering MM, Driehuys B, Cleveland ZI. Mapping cardiopulmonary dynamics within the microvasculature of the lungs using dissolved (129)Xe MRI. J Appl Physiol. 1985;129:218–229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gerges C, Gerges M, Friewald R, et al. Microvascular disease in chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension: Hemodynamic phenotyping and Histomorphometric assessment. Circulation. 2020;141:376–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fessler JA. Michigan Image Reconstruction Toolbox. Available at: https://github.com/JeffFessler/mirt

- 15.Niedbalski PJ, Hall CS, Castro M, et al. Protocols for multi-site trials using hyperpolarized (129) Xe MRI for imaging of ventilation, alveolar-airspace size, and gas exchange: A position paper from the (129) Xe MRI clinical trials consortium. Magn Reson Med. 2021;86:2966–2986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lu J. 2023. Oscillation imaging MRI demo. Available at: https://github.com/junlanlu/simulation-oscillation-imaging-mridemo.

- 17.Virtanen P, Gommers R, Oliphant TE, et al. SciPy 1.0: fundamental algorithms for scientific computing in python. Nat Method. 2020;17:261–272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Modi P, Cascella M. Diffusing Capacity of the Lungs for Carbon Monoxide. Treasure Island, Florida, USA: StatPearls; 2023. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Simonneau G, Montani D, Celermajer DS, et al. Haemodynamic definitions and updated clinical classification of pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir J. 2019;53:1801913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Humbert M, Kovacs G, Hoeper MM, et al. ESC/ERS guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension: Developed by the task force for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Respiratory Society (ERS). Endorsed by the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT) and the European Reference Network on Rare Respiratory Diseases (ERN-LUNG). Eur Heart J. 2022;43:3618–3731.36017548 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rosenkranz S, Lang IM, Blindt R, et al. Pulmonary hypertension associated with left heart disease: Updated recommendations of the Cologne Consensus Conference 2018. Int J Cardiol. 2018;272S:53–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.He M, Robertson SH, Kaushik SS, et al. Dose and pulse sequence considerations for hyperpolarized (129)Xe ventilation MRI. Magn Reson Imaging. 2015;33:877–885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Robertson SH, Virgincar RS, Freeman MS, Kaushik SS, Driehuys B. Optimizing 3D noncartesian gridding reconstruction for hyperpolarized 129Xe MRI-focus on preclinical applications. Concept Magn Reson A. 2015;44:190–202. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fessler JA, Sutton BP. Nonuniform fast Fourier transforms using min-max interpolation. IEEE Trans Signal Proc. 2003;51:560–574. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leewiwatwong S, Lu J, Zhang J, et al. Ventilation defect synthesis in hyperpolarized 129Xe ventilation MRI to accelerate training of segmentation models. In: Proceedings of the 31st Annual Meeting of ISMRM. London, UK 2022. Abstract #1178. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Astley JR, Biancardi AM, Hughes PJC, et al. Large-scale investigation of deep learning approaches for ventilated lung segmentation using multi-nuclear hyperpolarized gas MRI. SciRep. 2022;12:10566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang Z, He M, Bier E, et al. Hyperpolarized (129) Xe gas transfer MRI: the transition from 1.5T to 3T. Magn Reson Med. 2018;80:2374–2383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang Z, Robertson SH, Wang J, et al. Quantitative analysis of hyperpolarized (129) Xe gas transfer MRI. Med Phys. 2017;44:2415–2428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sakia RM. The box-cox transformation technique: A review. J Royal Statistical Soc Series D (The Statistician). 1992;41:169–178. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Patil I. Visualizations with statistical details: The ‘ggstatsplot’ approach. J Open Sour Software. 2021;6:3167. doi: 10.21105/joss.03167 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Niedbalski PJ, Lu J, Hall CS, et al. Utilizing flip angle/TR equivalence to reduce breath hold duration in hyperpolarized (129) Xe 1-point Dixon gas exchange imaging. Magn Reson Med. 2022;87:1490–1499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bier EA, Alenezi F, Lu J, et al. Extension of a diagnostic model for pulmonary hypertension with hyperpolarized 129Xe magnetic resonance imaging and spectroscopy. In: Proceedings of the 30th Annual Meeting of ISMRM. 2021. Abstract #681. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Madani MM. Surgical treatment of chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension: Pulmonary Thromboendarterectomy. Methodist Debakey Cardiovasc J. 2016;12:213–218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oster J, Clifford GD. Acquisition of electrocardiogram signals during magnetic resonance imaging. Physiol Meas. 2017;38:R119–R142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Simonneau G, Torbicki A, Dorfmüller P, Kim N. The pathophysiology of chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir Rev. 2017;26:160112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Feng L. Golden-angle radial MRI: Basics, advances, and applications. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2022;56:45–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hollingsworth KG. Reducing acquisition time in clinical MRI by data undersampling and compressed sensing reconstruction. Phys Med Biol. 2015;60:R297–R322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zeng G, Guo Y, Zhan J, et al. A review on deep learning MRI reconstruction without fully sampled k-space. BMC Med Imaging. 2021;21:195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kern AL, Gutberlet M, Qing K, et al. Regional investigation of lung function and microstructure parameters by localized 129Xe chemical shift saturation recovery and dissolved-phase imaging:a reproducibility study. Magn Reson Med. 2019;81:13–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bechtel A, Lu J, Mummy D, et al. Establishing a hemoglobin adjustment for (129) Xe gas exchange MRI and MRS. Magn Reson Med. 2023;90:1555–1568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Plummer JW, Willmering MM, Cleveland ZI, Towe C, Woods JC, Walkup LL. Childhood to adulthood: Accounting for age dependence in healthy-reference distributions in (129) Xe gas-exchange MRI. Magn Reson Med. 2023;89: 1117–1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Howard LS, Grapsa J, Dawson D, et al. Echocardiographic assessment of pulmonary hypertension: Standard operating procedure. Eur Respir Rev. 2012;21:239–248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mummy DS, Lu J, Leewiwatwong S, et al. Hyperpolarized 129Xe MRI of healthy subjects reveals age-related changes in gas. In: Proceedings of the International Workshop on Pulmonary Functional Imaging. Hannover, Germany: 2022. [Google Scholar]