Abstract

In the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe, centromeres remain clustered at the spindle-pole body (SPB) during mitotic interphase. In contrast, during meiotic prophase centromeres dissociate from the SPB. Here we examined the behavior of centromere proteins in living meiotic cells of S. pombe. We show that the Nuf2-Ndc80 complex proteins (Nuf2, Ndc80, Spc24, and Spc25) disappear from the centromere in meiotic prophase when the centromeres are separated from the SPB. The centromere protein Mis12 also dissociates during meiotic prophase; however, Mis6 remains throughout meiosis. When cells are induced to meiosis by inactivation of Pat1 kinase (a key negative regulator of meiosis), centromeres remain associated with the SPB during meiotic prophase. However, inactivation of Nuf2 by a mutation causes the release of centromeres from the SPB in pat1 mutant cells, suggesting that the Nuf2-Ndc80 complex connects centromeres to the SPB. We further found that removal of the Nuf2-Ndc80 complex from the centromere and centromere-SPB dissociation are caused by mating pheromone signaling. Because pat1 mutant cells also show aberrant chromosome segregation in the first meiotic division and this aberration is compensated by mating pheromone signaling, dissociation of the Nuf2-Ndc80 complex may be associated with remodeling of the kinetochore for meiotic chromosome segregation.

INTRODUCTION

Eukaryotic chromosomes are spatially organized within the nucleus. Such a nuclear architecture provides a physical framework for activities of the chromosomes, yet this framework is dynamic, being able to change its functional organization. The fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe exhibits a striking example of the dynamic repositioning of centromeres and telomeres upon entering meiosis. In this organism, centromeres cluster near the spindle pole body (SPB; a centrosome-equivalent structure in fungi) throughout mitotic interphase; however, during meiotic prophase centromeres detach from the SPB, and instead telomeres cluster to the SPB. In S. pombe, such a reorganized nucleus elongates and oscillates between the cell poles in meiotic prophase, with telomeres clustered at the SPB located at the leading edge of the moving nucleus (Chikashige et al., 1994). The elongated nucleus is often called the “horsetail” nucleus. It is known that telomere clustering and nuclear movement facilitate homologous chromosome pairing by aligning the chromosomes from the telomere and promoting contact of homologous loci (Ding et al., 2004). However, the mechanisms of centromere-telomere repositioning during meiosis remain largely unknown. Analysis of centromere proteins in meiotic prophase would lead us to understanding of the mechanisms of centromere detachment from the SPB.

The regulation of centromere proteins during repositioning of centromeres may affect the fundamental function of the kinetochore in meiosis as well as in mitosis. Centromere proteins play important roles in attachment of spindle microtubules, have checkpoint functions to monitor the proper attachment of spindle microtubules, and are involved in force generation during chromosome segregation. During mitosis, pairs of sister chromatids produced by DNA replication segregate equally to dividing cells. In contrast, during meiosis, sister chromatids segregate to the same pole (reductional segregation) at the first meiotic division (meiosis I), whereas they segregate to the opposite poles (equational segregation) at the second meiotic division (meiosis II) as in mitosis. Reductional segregation is achieved by monopolar attachment of the spindle to the kinetochore that is established uniquely during meiosis. These kinetochore functions are conserved from yeasts to humans.

A multilayered structure of the S. pombe centromere-SPB complex has been proposed: in mitotic interphase, centromeres cluster at the SPB via layers of centromere proteins together with heterochromatin, γ-tubulin, and other proteins that form an “anchor” between the heterochromatin and SPB (Kniola et al., 2001; also see Figure 8). Furthermore, subcomplex structures of the S. pombe centromere, similar to that of Saccharomyces cerevisiae and human, were reported (Hayashi et al., 2004; Obuse et al., 2004). Mutations in the centromere proteins Mis6 and Nuf2 cause detachment of centromeres in mitotic interphase cells (Saitoh et al., 1997; Appelgren et al., 2003) so these centromere proteins may provide the molecular basis for centromere clustering in mitotic interphase.

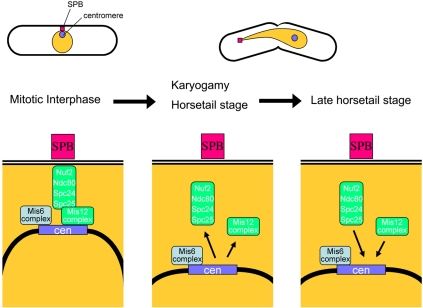

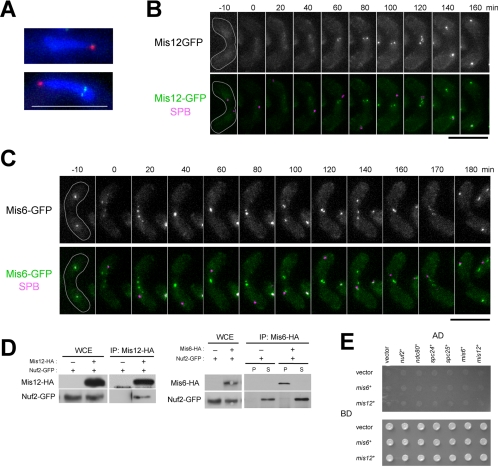

Figure 8.

The S. pombe kinetochore structure. In mitotic interphase, centromeres locate near the SPB along with kinetochore complexes, including Nuf2-Ndc80 complex, Mis12 complex and Mis6 complex. During karyogamy and the horsetail stage, Nuf2-Ndc80 complex and Mis12 disappear from the centromere leading to the centromere-SPB dissociation. At the late horsetail stage, Mis12 complex and Nuf2-Ndc80 complex reappear at the centromere.

It remains unknown, however, how clustered centromeres detach from the SPB in meiotic prophase. Because the S. pombe Nuf2 disappears from the centromere-SPB complex during karyogamy (fusion of haploid nuclei) and meiotic prophase when centromeres detach from the SPB (Nabetani et al., 2001), we have speculated that S. pombe Nuf2 protein might be involved in centromere detachment in meiotic prophase. Nuf2 is an evolutionally conserved centromere protein belonging to the Ndc80 complex which is comprised of other conserved proteins, Ndc80/Hec1, Nuf2, Spc24, and Spc25 (Howe et al., 2001; Janke et al., 2001; Nabetani et al., 2001; Wigge and Kilmartin, 2001; DeLuca et al., 2002; De Wulf et al., 2003; Hori et al., 2003; McCleland et al., 2003, 2004; Bharadwaj et al., 2004). In this article, we observed the behavior of centromere proteins during meiosis in living cells of S. pombe and found that the Nuf2-Ndc80 complex proteins and Mis12 disappear during meiotic prophase. In addition, we found that Nuf2 remained at the centromere in pat1 mutant cells, which enter meiosis with centromeres clustered to the SPB. We then monitored the position of centromeres in the pat1 mutant cells with inactivated Nuf2 and found that centromeres dissociated from the SPB when Nuf2 was inactivated. These analyses reveal the likely roles of the Nuf2-Ndc80 complex proteins in centromere detachment from the SPB.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

S. pombe Strains and Media

Strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. YES and EMM2 were used as growth media, and ME was used as sporulation medium (Moreno et al., 1991).

Table 1.

Strain list

| Strains | Genotypes |

|---|---|

| S. pombe | |

| HA252-4A | h90 ade6-216 ura4-D18 leu1-32 nuf2+::GFP-ura4+ sad1+::DsRed-LEU2 |

| HA525 | h90 leu1-32 ade6-210 ura4 sad1+::DsRed-LEU2 his7+::LacI-GFP lys1+::LacOp nuf2+::CFP-ura4+ |

| HA205-2A | h90 ade6-216 ura4-D18 leu1-32 ndc80+::GFP-ura4+ sad1+::DsRed-LEU2 |

| HA229-11A | h90 ade6-216 ura4-D18 leu1-32 spc24+::GFP-ura4+ sad1+::DsRed-LEU2 |

| HA485-10D | h90 ade6-216 ura4-D18 leu1-32 spc25+::GFP-ura4+ sad1+::DsRed-LEU2 |

| HA259-1D | h90 ade6-216 leu1-32 lys1+::mis12+-GFP sad1+::DsRed-LEU2 |

| HA260-7D | h90 ade6-216 ura4-D18 leu1-32 mis6+::GFP-LEU2 sad1+::DsRed-LEU2 |

| HA309-11C | h- ura4-D18 nuf2+::GFP-ura4+ pat1-114 |

| HA495-9B | h- ura4-D18 leu1-32 sad1+::DsRed-LEU2 cen2(D107)::kanr-ura4+-lacOp his7::lacI-GFP pat1-114 lys1+::mat-Pc |

| HA499-1C | h- ura4-D18 leu1-32 sad1+::DsRed-LEU2 cen2(D107)::kanr-ura4+-lacOp his7::lacI-GFP pat1-114 |

| HAR3021-1 | h- ura4-D18 nuf2+::GFP-ura4+ lys1+::mat-Pc pat1-114 |

| HAR3041-1 | h- ura4-D18 ndc80+::GFP-ura4+ lys1+::mat-Pc pat1-114 |

| HAR3031-1 | h- ura4-D18 spc24+::GFP-ura4+ lys1+::mat-Pc pat1-114 |

| HA3505C-1 | h- ura4-D18 cen2(D107)::mat-Pc-URA3 lys1+::mis12+::GFP pat1-114 |

| CRLa59-1 | h- ura4-D18 leu1-32 lys1+::mat-Pc mis6+::GFP-LEU2 pat1-114 |

| HA529 | h-/h- ade6-210/ade6-216 ura4/ura4 pat1-114/pat1-114 leu1-32/leu1+ his7+::lacI-GFP/his7+ cen2(D107)::kanr-ura4+-lacOp/cen2 sad1+:: DsRed-LEU2/sad1+ nuf2+::CFP-ura4+/nuf2+ |

| HA530 | h-/h- ade6-210/ade6-216 ura4/ura4 pat1-114/pat1-114 leu1-32/leu1+ his7+::lacI-GFP/his7+ cen2(D107)::kanr-ura4+-lacOp/cen2 sad1+:: DsRed-LEU2/sad1+ nuf2-1::CFP-ura4+/nuf2-1::ura4+ |

| HA478-1C | h90 ade6-216 ura4 leu1 nuf2-d2::ura4+lys1+::nmt1-nuf2+::GFP sid4+::mRFP-KanR |

| HA252-12B | h90 ade6-216 ura4-D18 leu1 nuf2+::GFP-ura4+ |

| HA374-2C | h90 ade6-216 ura4-D18 leu1 nuf2+::GFP-ura4+ ndc80+::HA-LEU2 |

| HA229-1C | h90 ade6-216 ura4-D18 leu1 spc24+::GFP-ura4+ |

| HA329-3A | h90 ade6-216 ura4-D18 leu1 spc24+::GFP-ura4+ ndc80+::HA-LEU2 |

| HA484-1A | h90 ade6-216 ura4-D18 leu1 spc25+::GFP-ura4+ |

| HA484-2C | h90 ade6-216 ura4-D18 leu12 spc25+::GFP-ura4+ ndc80+::HA-LEU |

| HA282-3D | h90 ade6-216 ura4-D18 leu1-32 nuf2+::GFP-ura4+ mis12+::HA-LEU2 |

| HA380-11C | h90 ade6-216 ura4-D18 leu1-32 nuf2+::GFP-ura4+ mis6+::HA-LEU2 |

| HA626-4D | h- leu1-32 pat1-114 nuf2+::HA-LEU2 lys1+::mat-Pc |

| S. cerevisiae | |

| NKY278 | MATa/MATα, ho::LYS2/ho::LYS2, ura3/ura3, lys2/lys2 |

| AH109 | MATα, trp1-901, leu2-3, 112, ura3-52, his3-200, gal4Δ, gal80Δ, LYS2::GAL1UAS-GAL1TATA-HIS3, GAL2UAS-GAL2TATA-ADE2, URA3::MEL1UA S-MELTATA-lacZ |

Microscopy

Living cells were observed as described in Ding et al. (1998). When necessary (see Figures 1, 3, 4, 5, and 7), a series of 10–14 focal images were taken with 0.4-μm intervals at each time point. For immunofluorescence microscopy, cells were treated as described (Hagan and Hyams, 1988). A rat monoclonal antibody 3F10 (Roche, Indianapolis, IN) was used as an anti-HA antibody, and Alexa488-conjugated goat anti-rat antibody (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) was used as a secondary antibody. Images were acquired using a Delta-Vision microscope system (Applied Precision, Seattle, WA) and data analysis was carried out using SoftWoRx software. The microscope system setup is described in Haraguchi et al. (1999).

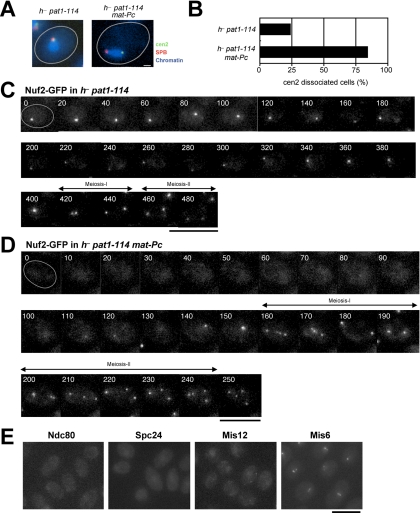

Figure 1.

Behavior of Nuf2 during meiosis. (A) Nuf2-GFP (green) and Sad1-DsRed (red) in mitotically growing cells of S. pombe strain (HA252–4A). The nucleus was stained with Hoechst33342 (blue). Bar, 1 μm. (B) Live cell observation of S. pombe Nuf2-GFP during karyogamy and meiotic prophase. HA252–4A strain was incubated on sporulation medium, and time-lapse images of living zygote cell were acquired. Nuf2-GFP (green) and Sad1-DsRed (magenta) are shown. Time 0 indicates when the Sad1-DsRed spots are fused. Although Nuf2-GFP disappears from centromeres, weak GFP signals are sometime observed in cytoplasm (e.g., frames at 31 and 42 min); such cytoplasmic signals can be distinguished from centromeric signals because they do not follow horsetail nuclear movements. Bar, 10 μm. (C) Localization of Nuf2 at the centromere. The HA525 strain was incubated on sporulation medium. Nuf2-CFP (blue), cen1-GFP (green), and Sad1-DsRed (red). Bar, 10 μm. (D) Observation of the S. cerevisiae Nuf2 protein during meiotic prophase. S. cerevisiae NKY278 strain was taken at 0 and 5 h after induction of meiosis and then prepared for immunostaining. Ndc10 protein was stained as a centromere marker. Bar, 15 μm.

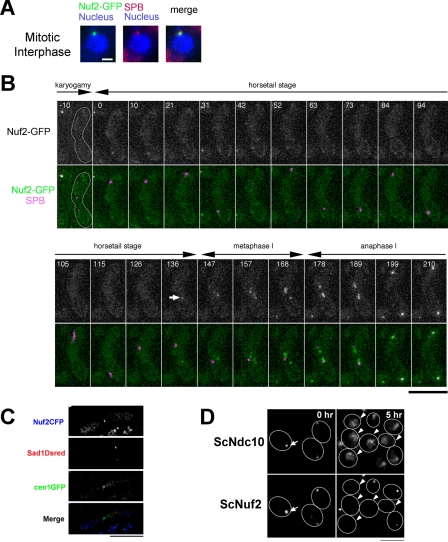

Figure 3.

Behaviors of Nuf2-Ndc80 complex proteins during karyogamy and meiotic prophase. (A) Observation of the S. pombe Ndc80, Spc24, and Spc25 proteins. Nuf2-interactors (green) and Sad1-DsRed (red) were observed in mitotically growing cells (HA205–2A, HA229–11C, and HA485–1D strains). The nucleus was stained with Hoechst33342 (blue). Bar, 1 μm. (B) Live cell observation of Ndc80, Spc24, and Spc25 during karyogamy and meiotic prophase. HA205–2A, HA229–11A, or HA485–1D strain was incubated on sporulation medium, and time-lapse observations of living zygote cells were performed as described in Figure 1. Ndc80-GFP, Spc24-GFP, or Spc25-GFP (green), and Sad1-DsRed (magenta) are shown in merged images. Bar, 10 μm. (C) Kinetics of the behavior of Nuf2-Ndc80 complex proteins. Time-lapse images of cells expressing Nuf2-GFP, Ndc80-GFP, Spc24-GFP, or Spc25-GFP were recorded at 5-min intervals. The horsetail stage was divided equally into five substages. In each substage, the number of time points when a spot signal of GFP was observed was counted and divided by the total number of time points to calculate the frequency of positive GFP signals. The percentages were plotted as a time course of the substages. Numbers of living cells examined: 22 for Nuf2-GFP, 14 for Ndc80-GFP, 12 for Spc24-GFP, and 11 for Spc25-GFP.

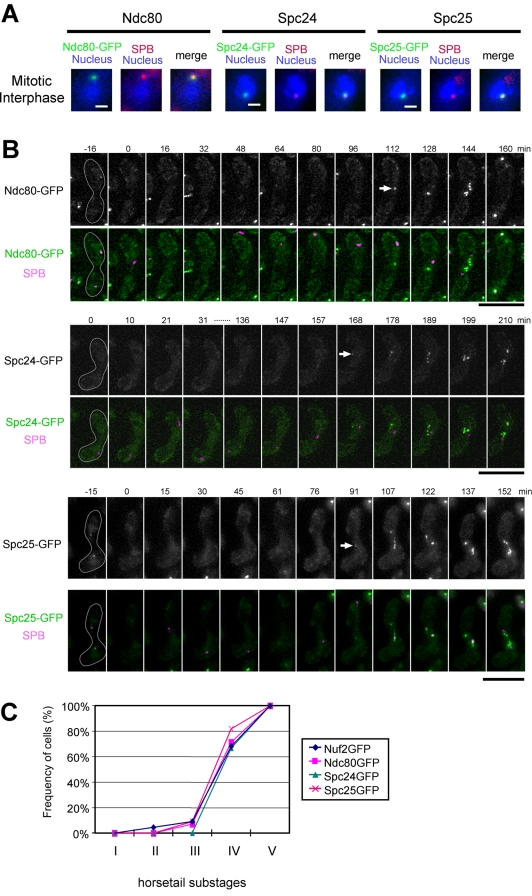

Figure 4.

Behavior of Mis12 and Mis6. (A) Localization of Mis12 or Mis6 in meiotic prophase. The Mis12-GFP (HA259–1D, top) and Mis6-GFP strains (HA260–7D, bottom) were incubated on sporulation media, and zygotic cells were observed. Typical horsetail nuclei are shown. The Mis12-GFP and Mis6-GFP were shown in green. The SPB was visualized by Sad1-DsRed (red), and the nuclei were stained with Hoechst33342 (blue). (B and C) Behavior of Mis12 and Mis6 during karyogamy and meiotic prophase. Living zygotes of the Mis12-GFP (HA259–1D) or Mis6-GFP strains (HA260–7D) were observed every 10 min in sporulation medium. Mis12-GFP or Mis6-GFP (green) and Sad1-DsRed (magenta) are also shown in merged images. Bars, 10 μm. (D) Immunoprecipitation assay between Mis12 and Nuf2 (left) and between Mis6 and Nuf2 (right). Extracts of Mis12 and Mis12-HA cells expressing Nuf2-GFP (HA282–3D and HA252–12B) and Mis6 and Mis6-HA cells expressing Nuf2-GFP (HA380-11C and HA252–12B) were incubated with anti-HA beads, and precipitates (IP) were subjected to immunoblot analysis using anti-GFP antibody. Whole-cell extracts were also analyzed (WCE). The extracts were prepared from growing cultures. In the right panel, P, precipitate; S, supernatant. (E) Yeast two-hybrid assay between Mis6 or Mis12 and Nuf2-Ndc80 complex proteins. Yeast strains were transformed with the combinations of plasmids as indicated, spotted onto selective (top) and nonselective media (bottom), and incubated for 3 d.

Figure 5.

Behavior of Nuf2 in pat1 mutant cells upon mating pheromone signaling. (A) Location of centromeres and SPB in living pat1 mutant cells in the absence or presence of the c-type mat gene. The strains HA499-1C (h− pat1-114) or HA495–9B (h− pat1-114 plus mat-Pc) were arrested in G1 by nitrogen starvation at 26°C. In these strains the centromere region of chromosome II was visualized using GFP-LacI (which recognizes the lacO sequence) and the SPB was visualized using Sad1-DsRed. The nuclei were stained with Hoechst33342 (blue). Bar, 10 μm. (B) Statistical analysis of the detachment of a centromere (cen2) from the SPB in A. n = 100 in each strain. (C) Behavior of Nuf2 in pat1-induced meiosis. h− pat1-114 cells expressing Nuf2-GFP (HA309–11C) were arrested in G1 by nitrogen starvation at a permissive temperature of 26°C, and the Nuf2-GFP was then observed after transfer to 34°C. Numbers in each frame indicate the time in minutes after the temperature shift. Bar, 10 μm. (D) Behavior of Nuf2 in pat1 mutant cells in the presence of the c-type mat gene. A strain HAR3021-1 (h− pat1-114 nuf2+-GFP strain harboring mat-Pc) was observed as described in C. Bar, 10 μm. (E) Behavior of Ndc80, Spc24, Mis12, and Mis6 in pat1 mutant cells in the presence of the c-type mat gene. Ndc80-GFP, Spc24-GFP, Mis12-GFP, and Mis6-GFP were observed in h− pat1-114 strains harboring the mat-Pc gene (HAR3041-1, HAR3031-1, HA3505C-1, and CRLa59-1) after the induction of G1 arrest by nitrogen starvation at 26°C. Bar, 10 μm.

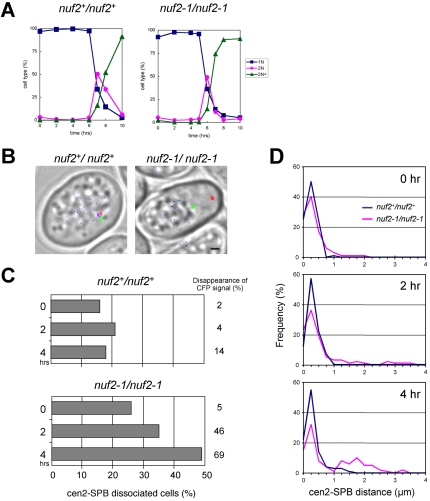

Figure 7.

Dissociation of centromeres by nuf2-1 mutation in pat1-induced meiotic prophase. (A) Progression of meiosis in nuf2+/nuf2+ and nuf2-1/nuf2-1 strains in the background of pat1ts mutation (HA529 and HA530, respectively). Both strains were arrested in G1 by nitrogen starvation at 26°C and then transferred to 34°C. Nuclear division was monitored by staining the nuclei with DAPI. (B) Localization of centromeres, SPB and Nuf2. Both strains were observed 4 h after the temperature shift in A. The peri-centromeric region of chromosome II (cen2) visualized by lacO/GFP-LacI method (Yamamoto and Hiraoka, 2003; green), SPB visualized by Sad1-DsRed (red), and Nuf2-CFP (blue) are shown as merged images with bright-field micrographs. Bar, 1 μm. (C) Frequency of the centromere-SPB separation. The distance between the centromere (cen2) and SPB was measured in cells of each strain at indicated time points after the temperature shift (0 h) in A. At least 100 cells were observed at each time point. The cell in which the cen2-SPB distance was >0.55 μm is shown as a cen2-SPB dissociated cell. Distances between cen2 and SPB for two strains were further compared by the Mann-Whitney U test. p values, 0.79 at 0 h, 0.69 at 2 h, and <0.0001 at 4 h. The number at the right of each graph indicates the percentage of cells with no detectable CFP signals of Nuf2 or Nuf2–1 protein. (D) Distribution of the centromere-SPB distance. Histogram of the cen2-SPB distance measured in C was made with 0.25-μm intervals and plotted for nuf2+ (blue) and nuf2-1 (red) at 0, 2, and 4 h.

S. cerevisiae Strain and Cytology

S. cerevisiae NKY278 strain (a derivative of SK1) was used (Table 1). Media, meiotic synchronization, and immunofluorescence staining of S. cerevisiae cells are described in Hayashi et al., (1998). Anti-Nuf2 and anti-Ndc10 antibodies were provided by Dr. P. Silver (Dana-farber, Cambridge, MA) and Dr. J. Kilmartin (MRC Laboratory, Cambridge, United Kingdom), respectively.

Protein Analysis

For immunoprecipitation, cells grown in YES medium to a density of 0.5–1 × 107 cells/ml were washed three times with extraction buffer (50 mM HEPESKOH [pH 7.5] containing 140 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, and 0.1% Na-deoxycholate). Cells were then resuspended in 500 μl of extraction buffer containing protease inhibitors and lysed using glass beads in a Fast-Prep machine (Bio101, Carlsbad, CA). After spinning the extracts, protein concentrations were determined using a BCA protein assay kit (Bio-Rad, Richmond, CA). Four milligrams of total protein extracts were subjected to immunoprecipitation by incubation with 0.5 mg of the anti-HA antibody 3F10 (Roche) for 1 h and with protein G-Sepharose (Amersham Biotech, Piscataway, NJ) for 1 h. Immunoprecipitates were washed with extraction buffer and subjected to SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis. GFP-tagged proteins were detected by mouse polyclonal anti-GFP antibodies (Clontech, Palo Alto, CA). Boiled extracts were prepared according to Masai et al. (1995). Proteins extracted from 107 cells were fractionated by SDS-PAGE and then transferred to PVDF membranes. HA-tagged proteins were detected with the rat monoclonal anti-HA antibody 3F10. The blots were also probed with a mouse anti-Cdc2 antibody (a gift of Dr. M. Yamashita, Hokkaido University, Japan) as a loading control.

Yeast Two-hybrid Assay

The MATCHMAKER GAL4 Two-Hybrid System (Clontech) was used for yeast two-hybrid assays. cDNAs of S. pombe nuf2+, ndc80+, spc24+, spc25+, mis6+, and mis12+ genes were synthesized by RT-PCR or amplified by PCR using a S. pombe cDNA library with appropriate oligonucleotide primers and ligated in-frame into pGBT9 or pGAD424. The S. cerevisiae strain (AH109) carrying these plasmids was tested for expression of the two reporter genes (HIS3 and ADE2) according to the Clontech MATCHMAKER system manual.

Construction of the Fusion Genes

Construction of the GFP-tagged S. pombe nuf2+ gene was described previously (Nabetani et al., 2001). PCR primers are listed in Table 2. To construct the HA-tagged nuf2+ gene, the nuf2+ genomic DNA was amplified by PCR using primers nuf2-1 and nuf2-21. The resulting fragment was digested with EcoT22I, which digests within the nuf2+ coding region, and NotI, and was cloned into the PstI-NotI site of pTN218, harboring an HA tag (Nakamura et al., 2001), to create pHA124. To construct the CFP-tagged nuf2+ gene vector, the CFP fragment and nmt1 terminator were ligated into pYC6 (Chikashige et al., 2004); the resulting vector is designated pCST62. The nuf2+ gene was then amplified from genomic DNA by PCR using primers nuf2-1 and nuf2-20 to generate BamHI restriction site at the 3′ terminus of the coding region. The resulting fragment was digested with EcoT14I and BamHI, and ligated into the PstI-BamHI site of pCST62 yielding pHA135. The nuf2-1 mutant gene was amplified by PCR using the same primer set with the nuf2-1::GFP construct (Nabetani et al., 2001) as a template. The resulting nuf2-1 mutant gene fragment was treated as described above to construct pHA136. Appropriate S. pombe strains were transformed with pHA124, pHA135 and pHA136 and were used for further manipulations. Integration of these constructs into the endogenous nuf2+ locus was confirmed by PCR. A plasmid for overexpression of the nuf2+-GFP fusion gene was constructed as follows. The nuf2+coding region was amplified by PCR using primers nuf2-1 and nuf2-2. The resulting fragment was digested with PstI and BamHI and cloned into the same site of pEGFP-N1 (Clontech) yielding Sp(nuf2-gfp+). Next, to obtain the nuf2+-GFP fusion gene fragment, the Sp(nuf2-gfp+) was digested with NotI, blunt-ended, digested again with BglII, and subsequently cloned into the BamHI-SmaI site of pREP1, which contains the thiamine-repressible nmt1 promoter (Maundrell, 1993). The resulting plasmid, pnmt-nuf2EGFP, was further digested with PstI and SacI and cloned into the same site of pYC36 (Chikashige et al., 2004), yielding pnmt-nuf2EGFP/36. pnmt-nuf2EGFP/36 was then transformed into an S. pombe strain and integrated at the lys1 locus. After confirmation of integration by PCR, the endogenous nuf2+ gene was disrupted with nuf2-d2 null mutant allele (Nabetani et al., 2001). Construction of the GFP-tagged S. pombe ndc80+, spc24+, and spc25+ genes was performed as follows. A portion of the S. pombe ndc80+ coding region was amplified by PCR using primers ndc80-1 and ndc80-2. The resulting fragment was digested with EcoRI, which digests within the ndc80+ coding region, and BamHI and ligated with EcoRI-BamHI fragment of pCT54 (Nabetani et al., 2001). The S. pombe spc24+ coding region was amplified by PCR using primers spc24-1 and spc24-2. The resulting fragment was digested with EcoT22I, which digests within the spc24+ coding region, and BamHI, and ligated with the PstI-BamHI fragment of pCT54. A portion of the S. pombe spc25+ coding region was amplified by PCR using primers spc25-4 and spc25-6. The resulting fragment was cloned into pCST53, which carries the GFP and ura4+ genes (provided by Y. Chikashige). To construct the HA-tagged ndc80+ gene, a portion of the ndc80+ coding region was amplified by PCR using primers ndc80-7 and ndc80-13. The resulting fragment was digested with SalI and NotI and cloned into the same site of the pTN218. These constructs were transformed into S. pombe strains to facilitate integration at each endogenous locus. Confirmation that the integrations occurred in the correct loci was achieved by PCR or genomic Southern analyses. A mis12+-GFP fusion construct (provided by Y. Chikashige) was made as follows: a DNA fragment containing a promoter region and the ORF of mis12+ gene (between −621 and 1795) was amplified by PCR and the fragment was cloned into pYC36 (Chikashige et al., 2004) with the GFP gene and terminator sequence of nmt1+ gene, yielding pYC767. pYC767 was then transformed into S. pombe strains for integration at the lys1+gene locus. The integration at the lys1+ locus was confirmed by PCR.

Table 2.

Oligonucleotide sequences used in this study

| Oligonucleotide names | Sequences |

|---|---|

| nuf2-1 | 5′AGCGCTGCAGATGGCACGAAAACACAC3′ |

| nuf2-2 | 5′CCGGATCC(BamHI)GAGTTAGAAGACCTTAAG3′ |

| nuf2-20 | 5′AAGGGATCC(BamHI)AGAGTTAGAAGACCTTAAG3′ |

| nuf2-21 | 5′ATGGCGGCCGC(NotI)CAGAGTTAGAAGACCTTAA3′ |

| ndc80-1 | 5′CCAGATCTTGATGCAAGATTCTTCCTCTTACG3′ |

| ndc80-2 | 5′CGGGATCC(BamHI)AGTTCCGAACGAGATAGGTC3′ |

| ndc80-7 | 5′CAAGTCGAC(SalI)TGCGCTACGCAAGTCGTCAAC3′ |

| ndc80-13 | 5′GAAGCGGCCGC(NotI)CCAGTTCCGAACGAGATAG3′ |

| spc24-1 | 5′CCAGATCTTGATGTCAGACAGTCCAATTGAAC3′ |

| spc24-2 | 5′CGGGATCC(BamHI)TTTTTGTCCTTACTATCATCAAG3′ |

| spc25-4 | 5′AGAGGATCC(BamHI)AATCAATTGAGACAGATCC3′ |

| spc25-6 | 5′ACTGTCGAC(SalI)TTACCGCGCAATCAT3′ |

Underscores indicate artificially added restriction sites.

RESULTS

Nuf2 Disappears from the Centromere during Meiotic Prophase

S. pombe centromeres cluster at the SPB in mitotic interphase, but detach from the SPB in karyogamy and the horsetail stage. The behavior of centromeres correlates with Nuf2 localization in S. pombe: Nuf2 is located at the centromere in the nucleus throughout the mitotic cell cycle, but is not observed during karyogamy and the horsetail stage (Nabetani et al., 2001). To follow the disappearance and reappearance of Nuf2 over time, we observed Nuf2-GFP fusion protein in individual living cells of S. pombe. The SPB was also visualized using Sad1 tagged with DsRed (Chikashige and Hiraoka, 2001; Chikashige et al., 2004). As shown in Figure 1, Nuf2-GFP, which was located at the centromere-SPB cluster in mitotic interphase (Figure 1A), disappeared from the centromere during karyogamy (Figure 1B; −10–0 min, when two Sad1-DsRed spots fuse to one spot) and during the horsetail stage (when the fused Sad1-DsRed oscillates in the cell). In late horsetail stage, before metaphase I, Nuf2-GFP reappeared as a single spot in the nucleus (136 min; indicated by the arrow). This change in Nuf2 localization was observed in all of the 22 cells that were examined in the living state. To confirm that Nuf2 reappears at the centromere, we observed Nuf2-CFP fusion protein and centromeres simultaneously in the same cells. In these experiments, the peri-centromeric region of chromosome I (cen1) was visualized using the lacO/GFP-LacI recognition system (Nabeshima et al., 1998). When Nuf2-CFP reappeared, it was colocalized with the GFP-labeled cen1 region (Figure 1C). These results indicate that Nuf2 dissociates from the centromere before karyogamy and reassociates with the centromere before the first meiotic division. The period of disappearance of Nuf2 from the centromere coincides with separation of the centromeres from the SPB.

Disappearance of Nuf2 in meiosis was also observed in the budding yeast S. cerevisiae. In S. cerevisiae, as in S. pombe, centromeres form a cluster near the SPB in the mitotic cell cycle and become scattered upon entering meiosis (Hayashi et al., 1998; Jin et al., 1998). When meiosis is induced synchronously, S. cerevisiae cells enter meiotic prophase from 2 to 5 h, followed by the first and second meiotic divisions. During meiotic prophase, the cluster of centromeres first extends along a line and then become scattered in the nucleus (Hayashi et al., 1998). Immunofluorescence staining revealed that S. cerevisiae Nuf2 (ScNuf2) disappeared during meiotic prophase. Before induction of meiosis, ScNuf2 was colocalized with Ndc10, a centromere marker protein (indicated by the arrow; Figure 1D, 0 h). At 5 h after the induction of meiosis, some cells showed a line pattern of centromeres and ScNuf2 signal was detected at one end of the line of centromeres (as can be seen in two cells at top right corner in Figure 1D, 5 h), but most cells showed a scattered pattern of centromeres and ScNuf2 signal was not detected in those cells, whereas Ndc10 was observed at the centromere as a scattered pattern of localization (indicated by the arrowheads; Figure 1D, 5 h). These results indicate that the observed disappearance of Nuf2 during meiotic prophase in S. pombe is conserved in S. cerevisiae.

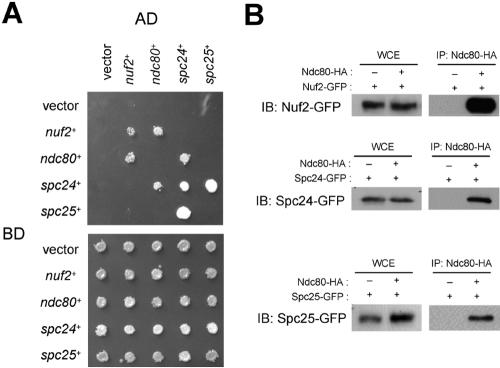

Nuf2-interacting Proteins also Disappear during Meiotic Prophase

It has been shown in many organisms that Nuf2 forms a protein complex with Ndc80, Spc24, and Spc25 as a part of kinetochore complexes (Wigge and Kilmartin, 2001; Janke et al., 2001; McCleland et al., 2003, 2004; Bharadwaj et al., 2004). In S. pombe, homologues of the Nuf2-interacting proteins, Ndc80, Spc24, and Spc25 have been identified by their amino acid sequences (SPBC11C11.03, SPBC336.08, and SPCC188.04c, respectively; Wigge and Kilmartin, 2001; Janke et al., 2001; McCleland et al., 2003, 2004; De Wulf et al., 2003; Bharadwaj et al., 2004). We have confirmed that the GFP-tagged gene products of SPBC11C11.03, SPBC336.08, and SPCC188.04c localize at the centromere in mitosis (Figure 3A). Moreover, yeast two-hybrid and immunoprecipitation assays have demonstrated that Nuf2, SPBC11C11.03, SPBC336.08, and SPCC188.04c interact (Figures 2, A and B). On the basis of these results, we conclude that SPBC11C11.03, SPBC336.08, and SPCC188.04c are S. pombe Ndc80, Spc24, and Spc25, respectively. The results of our two-hybrid assay of the S. pombe Nuf2-Ndc80 complex were similar to those for S. cerevisiae although there were some differences (see Discussion).

Figure 2.

Interactions of Nuf2-Ndc80 complex proteins. (A) Yeast two-hybrid assay of the Nuf2-Ndc80 complex. Yeast cells were transformed with the combinations of plasmids as indicated, spotted onto selective (top) and nonselective media (bottom), and incubated for 3 d. SD/-Leu, -Trp, -His, and -Ade medium, containing 1 mM 3-amino-1,2,4-triazole (3-AT) was used as the selective medium. (B) Immunoprecipitation assay of the Nuf2-Ndc80 complex. Extracts expressing Nuf2-GFP (HA252–12B and HA374–2C, top panel), Spc24-GFP (HA229–1C and HA329–3A, middle panel), or Spc25-GFP (HA484–1A and HA484–2C, bottom panel) were prepared in the absence or presence of Ndc80-HA (Ndc80-HA “−” or “+”, respectively). All extracts were prepared from growing cultures and incubated with anti-HA beads. The precipitates (IP) and whole cell extracts (WCE) were analyzed by Western blotting using anti-GFP antibody.

We then addressed whether Ndc80, Spc24, and Spc25 disappear during karyogamy and the horsetail stage. We constructed strains in which Ndc80-GFP, Spc24-GFP, or Spc25-GFP fusion gene replaced their respective endogenous locus. ndc80+, spc24+, and spc25+ are essential genes, and the respective GFP-fusion constructs were able to carry out the function of their genomic counterparts (unpublished data). As shown in Figure 3B, observations in living cells demonstrated that Ndc80-GFP, Spc24-GFP, and Spc25-GFP disappeared during karyogamy and the horsetail stage, and reappeared before meiotic division (indicated by the arrow), similar to what was found for Nuf2-GFP. For quantitative analysis of the behavior of the Nuf2-Ndc80 complex proteins, we divided the horsetail stage into five equal substages (each substage is 30.1 min on average), as was done in Ding et al. (2004), and counted the number of time points when the GFP signal was detected as a spot (see the legend to Figure 3B). Nuf2 reappeared at substage IV in 15 of the 22 cells examined; Ndc80, Spc24, and Spc25 also reappeared at substage IV in most of the cells (10 of 14 cells, 8 of 12 cells, and 9 of 11 cells examined, respectively; Figure 3C). During substage IV, there is a peak in the association of homologous centromeres (Ding et al., 2004), although it is not clear whether the reappearance of the Nuf2-Ndc80 complex proteins at the centromeres is involved in chromosome pairing. This analysis revealed that Nuf2, Ndc80, Spc24, and Spc25 reappear at similar times during late meiotic prophase. Thus, Nuf2, Ndc80, Spc24, and Spc25 probably behave as a complex during the period of meiosis.

Mis6 Remains at the Centromere during Meiotic Prophase, whereas Mis12 Levels Decrease at the Centromere

Next, we examined the behavior of well-characterized S. pombe centromere proteins, Mis6 and Mis12 (Saitoh et al., 1997; Goshima et al., 1999), which belong to separate subcomplexes (Hayashi et al., 2004; Obuse et al., 2004). Figure 4A shows strains expressing Mis12-GFP (top panel) and Mis6-GFP (bottom panel) during meiotic prophase. Although spots of Mis6-GFP were observed within the nucleus, spots of Mis12-GFP were not detected or were significantly reduced in intensity. Observations in living cells showed that levels of Mis12-GFP were significantly decreased at the centromere during karyogamy and the horsetail stage in a similar way to Nuf2, Ndc80, Spc24, and Spc25 (Figure 4B; 0–60 min). This reduction in signal was observed in 8 of the 9 cells examined. Unlike Nuf2, which showed no trace of staining within the nucleus, Mis12-GFP occasionally produced faint diffuse staining of the nucleus (Figure 4B). These results indicate that Mis12 dissociates from the centromere and diffuses through the whole nucleus. It should also be noted that Mis12 reappeared on the centromere significantly earlier than the Nuf2-Ndc80 complex (Figure 4B; compare with Figures 1B and 3B).

In contrast, Mis6-GFP remained at the centromere throughout the process of meiosis (Figure 4C): it was first localized as a single spot near the SPB in each of the haploid nuclei (−10 min), and upon the fusion of nuclei (indicated by the fusion of SPBs) the spot became scattered into several spots separate from the SPB (0 min), reflecting detachment of centromeres from the SPB; these spots of Mis6-GFP trailed the horsetail nuclear movements (20–160 min), and segregated during the meiotic division (170–180 min). The results were reproduced in all of the 20 cells examined. Thus, Mis6 and Mis12 behave differently in meiosis.

The different behaviors of Mis6 and Mis12 indicate the presence of at least two groups of centromere proteins: one is a group of constitutive centromere proteins including Mis6, and the other group includes the Nuf2-Ndc80 complex and Mis12, which are completely or partially dissociated from the centromere in meiotic prophase. An immunoprecipitation assay also indicated that the Nuf2-Ndc80 complex and Mis12 belong to the same group. In vegetative cells expressing Nuf2-GFP and Mis6-HA or Mis12-HA, an immunoprecipitation assay detected coprecipitation of Nuf2 with Mis12 (Figure 4D), indicating that Nuf2 forms a complex with Mis12. However, the interaction of Nuf2 with Mis12 may be indirect because no interaction was detected in the yeast two-hybrid assay (Figure 4E). In contrast, an interaction between Nuf2 and Mis6 was not detected by either the immunoprecipitation assay (Figure 4D) or the yeast two-hybrid assay (Figure 4E). Therefore the interaction between Nuf2 and Mis6 may be very weak in mitotic asynchronous culture.

Nuf2 Remains at the Centromere in pat1-induced Meiosis and Disappears upon Mating Pheromone Signaling

We examined whether the disappearance of Nuf2 correlates with centromere-SPB separation, using a temperature-sensitive mutant allele of pat1 (pat1-114). Pat1 is a kinase that negatively regulates initiation of meiosis and inactivation of the Pat1 kinase induces meiosis (Beach et al., 1985; Iino and Yamamoto, 1985; Nurse, 1985; Watanabe et al., 1997). Haploid cells of the pat1-114 mutant can be induced to enter meiosis synchronously by shifting to the restrictive temperature. Importantly in pat1-114 mutant cells, unlike in wild-type cells, centromeres remain associated with the SPB during meiotic prophase (Chikashige et al., 2004; Figures 5, A and B). Nuf2-GFP was observed in pat1-114 mutant cells induced to enter meiosis at the restrictive temperature. In these cells, a single spot of Nuf2 was continuously observed during nuclear movements; later, the spot separated into two, and then into four spots, reflecting two rounds of meiotic divisions (Figure 5C). These results indicate that Nuf2 remains at the centromere when centromeres are associated with the SPB in the pat1-114 mutant.

When pat1-114 cells are exposed to the mating pheromone, centromeres detach from the SPB (Y. Chikashige and Y. Hiraoka, unpublished results). Thus, we examined the behavior of Nuf2 in pat1-114 cells after activation of the mating pheromone response. To activate mating pheromone signaling, we constructed pat1 haploid cells that express the c-type of the mat gene of the opposite mating type. The expression of the c-type mat gene has the same effect as the addition of mating pheromone (Yamamoto and Hiraoka, 2003). Indeed, in h− pat1 haploid cells expressing mat-Pc, the c-type mat gene of h+ mating type, centromeres were separated from the SPB (Figures 5, A and B). In these cells, Nuf2-GFP was not detected at the time of meiosis induction (Figure 5D). As meiosis proceeded, Nuf2-GFP reappeared as a single spot within the nucleus that separated into two and then four spots during meiotic divisions (Figure 5D). The same experiments were performed with Ndc80-GFP, Spc24-GFP, Spc25-GFP, and Mis12-GFP. These proteins, like Nuf2, disappeared from centromeres in pat1-114 mutant cells expressing the mat-c gene (Figure 5E). In contrast, Mis6-GFP did not disappear under the same conditions but formed several spots scattered within the nucleus, showing that it associates with centromeres that are separated from the SPB (Figure 5E). Therefore, disappearance of the Nuf2-Ndc80 complex and Mis12 correlates with centromere detachment from the SPB in meiotic prophase. These results also indicate that removal of the Nuf2-Ndc80 complex from the centromere is under the regulation of mating pheromone signaling.

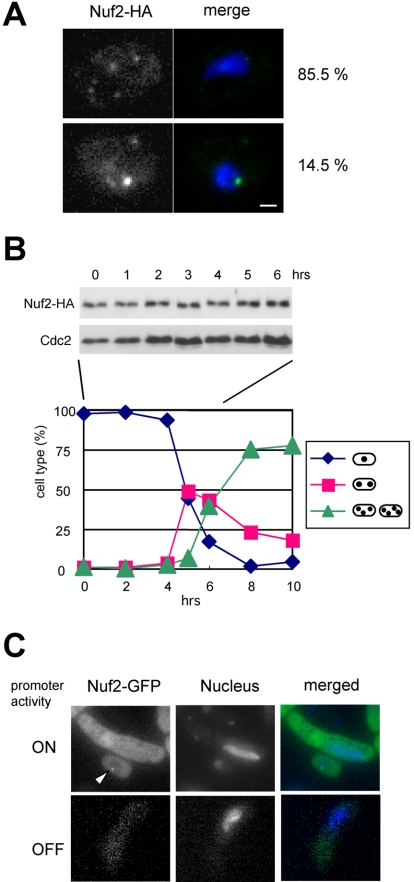

To test the possibility that the observed disappearance of the proteins is due to degradation, we examined the fate of the Nuf2 protein when no Nuf2-GFP fluorescence was detected at the centromere. In these experiments, we analyzed Nuf2-HA fusion protein in pat1-114 cells expressing the mat-Pc gene. We first confirmed by immunofluorescence staining that Nuf2-HA behaved similarly to Nuf2-GFP: Nuf2-HA disappeared from the centromere during meiotic prophase in wild-type meiosis (unpublished data). Also in pat1-114 cells expressing the mat-Pc gene, no centromere localization of Nuf2-HA was observed in most cells showing the horsetail nucleus (Figure 6A, top panel), whereas Nuf2-HA signals were sometime observed in cells that show mitotic interphase-like round nucleus (Figure 6A, bottom panel). Thus, we analyzed expression of Nuf2-HA fusion protein by immunoblot analysis in this strain. Expression of the mat-Pc gene in pat1-114 cells can induce meiosis in a synchronous manner (Figure 6B, bottom panel), and immunoblot analysis found that the amount of Nuf2 protein was basically unchanged throughout meiosis (Figure 6B, top panel). This result indicates that Nuf2 disappearance is not due to protein degradation. Next we examined cells overexpressing Nuf2-GFP. In these experiments, cells expressing Nuf2-GFP under the control of the thiamine repressible nmt1 promoter were incubated on sporulation medium without thiamine to induce expression. The overexpressed Nuf2-GFP did not remain at the centromere in meiotic prophase cells, whereas Nuf2-GFP localized at the centromere in mitotic cells (Figure 6C). These results strongly suggest that Nuf2 is actively removed from the centromere in meiotic prophase.

Figure 6.

(A) Immunofluorescence staining of Nuf2-HA protein in h− pat1-114 with mat-Pc (strain HA626-4D). Cells were fixed after the induction of G1 arrest by nitrogen starvation and subjected to immunofluorescence. More than 200 cells were observed to detect Nuf2-HA. Bar, 1 μm. (B) Expression of Nuf2 during meiosis. Cells of strain HA626–4D were arrested in G1 by nitrogen starvation and were induced to undergo synchronous meiosis by shifting the temperature as described in the legend to Figure 5. Cell extracts were prepared and subjected to immunoblot analysis with anti-HA antibody. As a loading control, Cdc2 was detected by anti-Cdc2 antibody. The kinetics of nuclear division were also monitored by staining nuclei with DAPI. (C) Localization of ectopically expressed Nuf2. Cells of strain HA478–1C, which express Nuf2-GFP under the thiamine repressible nmt1 promoter, were incubated on sporulation medium with (lower) or without thiamine (upper), and meiotic prophase cells were observed. Nuclei were stained with Hoechst-33342. The arrowhead indicates a mitotic interphase cell.

Dissociation of Nuf2 Releases the Centromere from the SPB

The observed correlation between Nuf2-Ndc80 complex dissociation and centromere-SPB separation raised the possibility that dissociation of the Nuf2-Ndc80 complex directly leads to centromere-SPB detachment. To examine this possibility, we used a temperature-sensitive mutant allele of nuf2 (nuf2-1). The temperature-sensitive Nuf2–1 protein does not localize at the centromere at the restrictive temperature (Nabetani et al., 2001). If removal of Nuf2 causes centromere detachment from the SPB, centromeres could be expected to dissociate from the SPB in nuf2-1 mutant cells at the restrictive temperature. We therefore induced meiosis in diploid wild-type (nuf2+) or nuf2-1 mutant cells with a background of pat1-114 (Figure 7A; nuf2+/nuf2+ and nuf2-1/nuf2-1, respectively) and examined the position of the centromere and SPB. In addition, Nuf2 protein (or Nuf2–1 mutant protein in the nuf2-1 mutant cells) was visualized by tagging with CFP. In nuf2+ cells with a background of pat1 mutation, Nuf2-CFP was localized at the centromere and the centromere was associated with the SPB in the majority of cells (Figure 7B, left); frequency of the centromere-SPB separation was 16–21% throughout meiotic prophase (Figure 7C, left), and distribution of the distance between centromeres and the SPB remained basically unchanged (Figure 7D). In contrast, in nuf2-1 cells with the pat1 mutation, the centromere-SPB distance increased as meiotic prophase proceeded (Figure 7D), and the number of cells showing the centromere-SPB dissociation increased from 26% at 0 h to 35% at 2 h and 49% at 4 h (Figure 7B, right; Figure 7C, right), whereas the number of cells with no detectable CFP signals of Nuf2–1 protein increased from 5% at 0h to 46% at 2hand 69% at 4 h. These results demonstrate that Nuf2 inactivation can cause dissociation of centromeres from the SPB as a consequence of loss of the centromere-SPB connection. It should be noted, however, the increase of cells showing the centromere-SPB dissociation was somewhat slower than that of cells with no detectable Nuf2–1 signals. This is probably because undetectable levels of Nuf2–1 protein remaining at the centromere still function to connect the centromere to the SPB or because centromeres gradually separate from the SPB after the loss of centromere-SPB connection.

DISCUSSION

In this report, we have described the behavior of the Nuf2-Ndc80 complex during meiosis in S. pombe. Levels of the Nuf2-Ndc80 complex proteins (Nuf2, Ndc80, Spc24, and Spc25) and Mis12 were significantly reduced at the centromere during a limited period of meiosis whereas another centromere protein Mis6 remained at the centromere throughout meiosis. Disappearance of the Nuf2-Ndc80 complex and Mis12 from the centromere coincides with detachment of the centromeres from the SPB during meiotic prophase (Figure 8). Moreover, the nuf2-1 mutation released the centromere from the SPB in pat1 mutant cells, demonstrating that the Nuf2 plays an important role for connection of centromeres to the SPB. In addition, removal of the Nuf2-Ndc80 complex and Mis12 from the centromere is caused by mating pheromone signaling. Removal of these centromere proteins during meiotic prophase may be necessary for remodeling meiosis-specific structures of the kinetochore. Other centromere proteins such as Mis6, which remain at the centromere during meiotic prophase, probably play a role in maintaining structural and functional integrity of the centromere during the remodeling process.

Nuf2-Ndc80 Complex in Fission Yeast

The Nuf2-Ndc80 complex is a conserved kinetochore complex in many eukaryotes. All of the Nuf2-Ndc80 complex proteins are probably necessary for its function. In S. cerevisiae, a mutation in any one of NUF2, NDC80, SPC24, and SPC25 disrupts the connection between centromeres and the spindle microtubules in mitosis (He et al., 2001; Janke et al., 2001; Wigge and Kilmartin, 2001; De Wulf et al., 2003), suggesting that each of these proteins has an indispensable function in the Nuf2-Ndc80 complex.

Homologues of the Nuf2-Ndc80 complex components (Nuf2, Ndc80, Spc24, and Spc25) have been reported in S. pombe (Janke et al., 2001; Nabetani et al., 2001; Wigge and Kilmartin, 2001; Bharadwaj et al., 2004) but their interactions have not been described. In this article we have demonstrated interactions between these components in yeast two-hybrid assay: Ndc80 interacts with Nuf2 and Spc24, and Spc24 interacts with Spc25; Nuf2 and Spc24 interact with themselves. These results in S. pombe are essentially consistent with two-hybrid interactions previously reported in S. cerevisiae (Cho et al., 1998; Janke et al., 2001), with some exceptions. The interaction between Spc25 and Spc25 reported in S. cerevisiae was not detected in S. pombe. The interaction between Nuf2 and Spc25 that was reported for S. cerevisiae was not detected in the presence of 3-AT (Figure 2A), but was detected in the absence of 3-AT (unpublished data) and is suggestive of a weak interaction between Nuf2 and Spc25 in S. pombe.

Subcomplex Structure of the S. pombe Kinetochore

In this study we identified two major groups of centromere proteins: the levels of one group are reduced at the centromere during meiotic prophase; levels of the other group remain unchanged at the centromere. Nuf2-Ndc80 complex proteins and Mis12 belong to the former group, and Mis6 belongs to the latter group. In contrast, during the mitotic cell cycle all of these proteins remain at the centromere. It has been shown recently that Mis6 and Mis12 form distinct subcomplexes on the centromere (Hayashi et al., 2004; Obuse et al., 2004). The fact that the Nuf2-Ndc80 complex and Mis12 disappear from or exhibit reduced levels at centromeres, whereas Mis6 remains at centromeres in meiotic prophase suggests that these subcomplexes are regulated differently in meiosis (Figure 8). Levels of the S. cerevisiae homologue of Nuf2 are also reduced at the centromere in meiosis, suggesting an evolutionally conserved mechanism for dissociation of the Nuf2-Ndc80 complex from the centromere.

In this study we demonstrated the physical interaction between Mis12 and the Nuf2-Ndc80 complex in mitotic cell cycle in S. pombe. Recently it was reported that hMis12 (human Mis12 homolog) interacts with Ndc80/Hec1 (Obuse et al., 2004), indicating similar subcomplex structures of the kinetochore in fission yeast and human. However, Mis12 probably belongs to a separate subcomplex from the Nuf2-Ndc80 complex on the centromere in S. pombe. In mis12 temperature-sensitive mutant cells, Mis12 mutant protein disappears from the centromere at the restrictive temperature (Goshima et al., 2003). During mitotic interphase in these mutant cells, the centromeres scatter from the SPB, whereas Nuf2 remains at the SPB as a single spot (H. Asakawa, unpublished observation). We therefore propose that Nuf2 is located on the SPB side and Mis12 on the centromere side, as shown in Figure 8. This idea is consistent with immunofluorescence and immunoelectron microscopy studies that have indicated that Ndc80 is located between Cnp1 and the SPB (Kniola et al., 2001). Cnp1 is a centromerespecific histone H3 variant protein that is recruited to the centromere by Mis6 (Takahashi et al., 2000). This configuration of kinetochore subcomplexes may reflect the fact that Mis12 reappears at the centromere earlier than the Nuf2 complex in meiotic prophase.

Regulation of Nuf2 Removal from Centromeres in Meiotic Prophase

In this article we have demonstrated that centromere localization of the Nuf2-Ndc80 complex is regulated during meiosis. The Nuf2-Ndc80 complex does not disappear from the centromere in meiosis induced by inactivation of the Pat1 kinase, but disappears upon the mating pheromone response. We have previously shown that Pat1 inactivation alone is not sufficient to detach centromeres from the SPB and requires mating pheromone signaling (this study; Chikashige et al., 2004; Yamamoto et al., 2004). Therefore, removal of the Nuf2-Ndc80 complex from the centromere and centromere detachment from the SPB are not achieved by Pat1 inactivation alone and require mating pheromone signaling. One important target of Pat1 kinase is Mei2, a key inducer of meiosis (Watanabe et al., 1997). It has been shown that during karyogamy in mei2 mutant cells centromeres frequently associate with the SPB and Nuf2 remains at the centromere-SPB cluster (H. Asakawa, unpublished observation). Thus, removal of Nuf2 may in part be regulated by Mei2 activation. Considering that disappearance of Nuf2 at centromeres induces centromere-SPB separation, we expect that removal of Nuf2 is regulated by Pat1-dependent and Pat1-independent regulatory pathways downstream of the mating pheromone signaling, as was demonstrated for the telomere-SPB clustering (Yamamoto et al., 2004). Although the factors downstream of mating pheromone signaling remain unknown, one important factor may be Polo kinase. Polo kinase has roles in meiotic centromere. In S. cerevisiae, Polo kinase is required for the cleavage of Rec8 and for the recruitment of Mam1, an essential factor for the mono-orientation of sister kinetochores in meiosis I (Clyne et al., 2003; Lee and Amon, 2003). Polo kinase may have a role in the kinetochore architecture in meiotic prophase. Another important candidate is Bub1 checkpoint kinase. In meiosis Bub1 is required for maintenance of meiotic cohesin Rec8 and of SgoI (a protector of Rec8) to ensure correct chromosome segregation in S. pombe (Bernard et al., 2001; Kitajima et al., 2004). Checkpoint proteins other than Bub1 may also be involved in Nuf2-Ndc80 complex behavior because it has been reported that these checkpoint proteins interact with the Nuf2-Ndc80 complex during the mitotic cell cycle (Martin-Lluesma et al., 2002; DeLuca et al., 2003; Gillett et al., 2004),

Kinetochore Remodeling and Meiotic Sister Chromatid Segregation

What is the significance of the removal of some centromere proteins during meiosis? There are interesting correlations between the three meiotic chromosomal events: 1) Nuf2 dissociation from the centromere in meiotic prophase, 2) centromere separation from the SPB in meiotic prophase, and 3) reductional segregation of chromosomes at the first meiotic division. When meiosis is induced in cells by Pat1 inactivation, those cells show aberrant behaviors in all of these chromosomal events: Nuf2 remains at the centromere (this study), centromeres remain associated with the SPB (this study; Chikashige et al., 2004), and sister chromatids fail to exhibit reductional segregation at the first meiotic division (Yamamoto and Hiraoka, 2003). By activating mating pheromone signaling it is possible to convert all of those aberrant activities to normal behaviors: Nuf2 dissociates from the centromere (this study), centromeres dissociate from the SPB (this study), and reductional segregation of chromosomes is recovered (Yamamoto and Hiraoka, 2003; Yamamoto et al., 2004).

An interesting question is whether disappearance of the Nuf2-Ndc80 complex and/or dissociation of centromeres from the SPB is a prerequisite for reductional segregation of sister chromatids. During meiotic prophase meiosis-specific centromere proteins are expected to be incorporated into the kinetochore to establish the mono-oriented structure that is required for reductional segregation of sister chromatids in meiosis I. The pat1 mutant show aberrant segregation in meiosis I and this aberrancy is compensated by mating pheromone signaling, but molecular basis for this difference has been unknown. This is the first report of such molecules that behave differently in pat1 mutant cells with and without mating pheromone signaling. The mating pheromone-dependent dissociation of Nuf2-Ndc80 complex proteins and Mis12 may be a part of kinetochore remodeling process required for proper segregation of meiotic chromosomes. One fascinating possibility is that removal of the Nuf2-Ndc80 complex from the centromere is required for this meiotic remodeling of the kinetochore. In the pat1 mutant cells in the absence of the mating pheromone response, the kinetochore may retain the mitotic architecture containing the Nuf2-Ndc80 complex during meiosis, resulting in bipolar segregation of sister chromatids in meiosis I.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mitsuhiro Yanagida, Pamela Silver, John Kilmartin, Masakane Yamashita, Taro Nakamura, Akira Nabetani, and Yuji Chikashige for providing antibodies, plasmids, and fission yeast strains; Kaori Tatsumi, Hiroko Osakada, and Chie Mori for technical assistance; Kohta Takahashi, Shigeaki Saitoh, and Ayumu Yamamoto for critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by grants from the Japan Science and Technology Agency to Y.H. and T.H.

This article was published online ahead of print in MBC in Press (http://www.molbiolcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1091/mbc.E04–11–0996) on February 23, 2005.

References

- Appelgren, H., Kniola, B., and Ekwall, K. (2003). Distinct centromere domain structures with separate functions demonstrated in live fission yeast cells. J. Cell Sci. 116, 4035–4042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beach, D., Rodgers, L., and Gould, J. (1985). RAN1+ controls the transition from mitotic division to meiosis in fission yeast. Curr. Genet. 10, 297–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard, P., Maure, J. F., and Javerzat, J. P. (2001). Fission yeast Bub1 is essential in setting up the meiotic pattern of chromosome segregation. Nat. Cell Biol. 3, 522–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bharadwaj, R., Qi, W., and Yu, H. (2004). Identification of two novel components of the human NDC80 kinetochore complex. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 13076–13085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chikashige, Y., Ding, D. Q., Funabiki, H., Haraguchi, T., Mashiko, S., Yanagida, M., and Hiraoka, Y. (1994). Telomere-led premeiotic chromosome movement in fission yeast. Science 264, 270–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chikashige, Y., and Hiraoka, Y. (2001). Telomere binding of the Rap1 protein is required for meiosis in fission yeast. Curr. Biol. 11, 1618–1623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chikashige, Y., Kurokawa, R., Haraguchi, T., and Hiraoka, Y. (2004). Meiosis induced by inactivation of Pat1 kinase proceeds with aberrant nuclear positioning of centromeres in the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Genes Cells 9, 671–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho, R. J., Fromont-Racine, M., Wodicka, L., Feierbach, B., Stearns, T., Legrain, P., Lockhart, D. J., and Davis, R. W. (1998). Parallel analysis of genetic selections using whole genome oligonucleotide arrays. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95, 3752–3757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clyne, R. K., Katis, V.L., Jessop, L., Benjamin, K. R., Herskowitz, I., Lichten, M., and Nasmyth, K. (2003). Polo-like kinase Cdc5 promotes chiasmata formation and cosegregation of sister centromeres at meiosis I. Nat. Cell Biol. 5, 480–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Wulf, P., McAinsh, A. D., and Sorger, P. K. (2003). Hierarchical assembly of the budding yeast kinetochore from multiple subcomplexes. Genes Dev. 17, 2902–2921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLuca, J. G., Howell, B. J., Canman, J. C., Hickey, J. M., Fang, G., and Salmon, E. D. (2003). Nuf2 and Hec1 are required for retention of the checkpoint proteins Mad1 and Mad2 to kinetochores. Curr. Biol. 13, 2103–2109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLuca, J. G., Moree, B., Hickey, J.M., Kilmartin, J. V., and Salmon, E. D. (2002). hNuf2 inhibition blocks stable kinetochore-microtubule attachment and induces mitotic cell death in HeLa cells. J. Cell Biol. 159, 549–555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding, D. Q., Chikashige, Y., Haraguchi, T., and Hiraoka, Y. (1998). Oscillatory nuclear movement in fission yeast meiotic prophase is driven by astral microtubules, as revealed by continuous observation of chromosomes and microtubules in living cells. J. Cell Sci. 111, 701–712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding, D. Q., Yamamoto, A., Haraguchi, T., and Hiraoka, Y. (2004). Dynamics of homologous chromosome pairing during meiotic prophase in fission yeast. Dev. Cell 6, 329–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillett, E. S., Espelin, C. W., and Sorger, P. K. (2004). Spindle checkpoint proteins and chromosome-microtubule attachment in budding yeast. J. Cell Biol. 164, 535–546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goshima, G., Saitoh, S., and Yanagida, M. (1999). Proper metaphase spindle length is determined by centromere proteins Mis12 and Mis6 required for faithful chromosome segregation. Genes Dev. 13, 1664–1677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goshima, G., Iwasaki, O., Obuse, C., and Yanagida, M. (2003). The role of Ppe1/PP6 phosphatase for equal chromosome segregation in fission yeast kinetochore. EMBO J. 22, 2752–2763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagan, I. M., and Hyams, J. S. (1988). The use of cell division cycle mutants to investigate the control of microtubule distribution in the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. J. Cell Sci. 89(Pt 3), 343–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haraguchi, T., Ding, D. Q., Yamamoto, A., Kaneda, T., Koujin, T., and Hiraoka, Y. (1999). Multiple-color fluorescence imaging of chromosomes and microtubules in living cells. Cell Struct. Funct. 24, 291–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi, A., Ogawa, H., Kohno, K., Gasser, S., and Hiraoka, Y. (1998). Meiotic behaviours of chromosomes and microtubules in budding yeast: relocalization of centromeres and telomeres during meiotic prophase. Genes Cells 3, 587–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi, T., Fujita, Y., Iwasaki, O., Adachi, Y., Takahashi, K., and Yanagida, M. (2004). Mis16 and Mis18 are required for CENP-A loading and histone deacetylation at centromeres. Cell 118, 715–729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He, X., Rines, D. R., Espelin, C. W., and Sorger, P. K. (2001). Molecular analysis of kinetochore-microtubule attachment in budding yeast. Cell 106, 195–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hori, T., Haraguchi, T., Hiraoka, Y., Kimura, H., and Fukagawa, T. (2003). Dynamic behavior of Nuf2-Hec1 complex that localizes to the centrosome and centromere and is essential for mitotic progression in vertebrate cells. J. Cell Sci. 116, 3347–3362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howe, M., McDonald, K. L., Albertson, D.G., and Meyer, B. J. (2001). HIM-10 is required for kinetochore structure and function on Caenorhabditis elegans holocentric chromosomes. J. Cell Biol. 153, 1227–1238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iino, Y., and Yamamoto, M. (1985). Mutants of Schizosaccharomyces pombe which sporulate in the haploid state. Mol. Gen. Genet. 198, 416–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janke, C., Ortiz, J., Lechner, J., Shevchenko, A., Magiera, M. M., Schramm, C., and Schiebel, E. (2001). The budding yeast proteins Spc24p and Spc25p interact with Ndc80p and Nuf2p at the kinetochore and are important for kinetochore clustering and checkpoint control. EMBO J. 20, 777–791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin, Q., Trelles-Sticken, E., Scherthan, H., and Loidl, J. (1998). Yeast nuclei display prominent centromere clustering that is reduced in nondividing cells and in meiotic prophase. J. Cell Biol. 141, 21–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitajima, T. S., Kawashima, S. A., and Watanabe, Y. (2004). The conserved kinetochore protein shugoshin protects centromeric cohesion during meiosis. Nature 427, 510–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kniola, B., O'Toole, E., McIntosh, J. R., Mellone, B., Allshire, R., Mengarelli, S., Hultenby, K., and Ekwall, K. (2001). The domain structure of centromeres is conserved from fission yeast to humans. Mol. Biol. Cell 12, 2767–2775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, B. H., and Amon, A. (2003). Role of Polo-like kinase CDC5 in programming meiosis I chromosome segregation. Science 300, 482–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Lluesma, S., Stucke, V. M., and Nigg, E. A. (2002). Role of Hec1 in spindle checkpoint signaling and kinetochore recruitment of Mad1/Mad2. Science 297, 2267–2270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masai, H., Miyake, T., and Arai, K.-i. (1995). hsk1+, a Schizosaccharomyces pombe gene related to Saccharomyces cerevisiae CDC7, is required for chromosomal replication. EMBO J. 14, 3094–3104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maundrell, K. (1993). Thiamine-repressible expression vectors pREP and pRIP for fission yeast. Gene 123, 127–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCleland, M. L., Gardner, R. D., Kallio, M. J., Daum, J. R., Gorbsky, G. J., Burke, D. J., and Stukenberg, P. T. (2003). The highly conserved Ndc80 complex is required for kinetochore assembly, chromosome congression, and spindle checkpoint activity. Genes Dev. 17, 101–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCleland, M. L., Kallio, M. J., Barrett-Wilt, G. A., Kestner, C. A., Shabanowitz, J., Hunt, D. F., Gorbsky, G. J., and Stukenberg, P. T. (2004). The vertebrate Ndc80 complex contains Spc24 and Spc25 homologs, which are required to establish and maintain kinetochore-microtubule attachment. Curr. Biol. 14, 131–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno, S., Klar, A., and Nurse, P. (1991). Molecular genetic analysis of fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Methods Enzymol. 194, 795–823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nabeshima, K., Nakagawa, T., Straight, A. F., Murray, A., Chikashige, Y., Yamashita, Y. M., Hiraoka, Y., and Yanagida, M. (1998). Dynamics of centromeres during metaphase-anaphase transition in fission yeast: Dis1 is implicated in force balance in metaphase bipolar spindle. Mol. Biol. Cell 9, 3211–3225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nabetani, A., Koujin, T., Tsutsumi, C., Haraguchi, T., and Hiraoka, Y. (2001). A conserved protein, Nuf2, is implicated in connecting the centromere to the spindle during chromosome segregation: a link between the kinetochore function and the spindle checkpoint. Chromosoma 110, 322–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura, T., Nakamura-Kubo, M., Hirata, A., and Shimoda, C. (2001). The Schizosaccharomyces pombe spo3+ gene is required for assembly of the forespore membrane and genetically interacts with psy1+-encoding syntaxin-like protein. Mol. Biol. Cell 12, 3955–3972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nurse, P. (1985). Mutants of the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe which alter the shift between cell proliferation and sporulation. Mol. Gen. Genet. 198, 497–502. [Google Scholar]

- Obuse, C., Iwasaki, O., Kiyomitsu, T., Goshima, G., Toyoda, Y., and Yanagida, M. (2004). A conserved Mis12 centromere complex is linked to heterochromatic HP1 and outer kinetochore protein Zwint-1. Nat. Cell Biol. 6, 1135–1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saitoh, S., Takahashi, K., and Yanagida, M. (1997). Mis6, a fission yeast inner centromere protein, acts during G1/S and forms specialized chromatin required for equal segregation. Cell 90, 131–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi, K., Chen, E. S., and Yanagida, M. (2000). Requirement of Mis6 centromere connector for localizing a CENP-A-like protein in fission yeast. Science 288, 2215–2219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe, Y., Shiozaki-Yabana, S., Chikashige, Y., Hiraoka, Y., and Yamamoto, M. (1997). Phosphorylation of RNA-binding protein controls cell cycle switch from mitotic to meiotic in fission yeast. Nature 386, 187–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wigge, P. A., and Kilmartin, J. V. (2001). The Ndc80p complex from Saccharomyces cerevisiae contains conserved centromere components and has a function in chromosome segregation. J. Cell Biol. 152, 349–360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto, A., and Hiraoka, Y. (2003). Monopolar spindle attachment of sister chromatids is ensured by two distinct mechanisms at the first meiotic division in fission yeast. EMBO J. 22, 2284–2296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto, T. G., Chikashige, Y., Ozoe, F., Kawamukai, M., and Hiraoka, Y. (2004). Activation of the pheromone-responsive MAP kinase drives haploid cells to undergo ectopic meiosis with normal telomere clustering and sister chromatid segregation in fission yeast. J. Cell Sci. 117, 3875–3886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]