Abstract

Background:

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) following traumatic childbirth may undermine maternal and infant health, but screening for maternal childbirth-related PTSD (CB-PTSD) remains lacking. Acute emotional distress in response to a traumatic experience strongly associates with PTSD. The Peritraumatic Distress Inventory (PDI) assesses acute distress in non-postpartum individuals, but its use to classify women likely to endorse CB-PTSD is unknown.

Methods:

3,039 women provided information about their mental health and childbirth experience. They completed the PDI regarding their recent childbirth event, and a PTSD symptom screen to determine CB-PTSD. We employed Exploratory Graph Analysis and bootstrapping to reveal the PDI’s factorial structure and optimal cutoff value for CB-PTSD classification.

Results:

Factor analysis revealed two strongly correlated stable factors based on a modified version of the PDI: (1) negative emotions and (2) bodily arousal and threat appraisal. A score of 15+ on the modified PDI produced high sensitivity and specificity: 88% with a positive CB-PTSD screen in the first postpartum months and 93% with a negative screen.

Limitations:

In this cross-sectional study, the PDI was administered at different timepoints postpartum. Future work should examine the PDI’s predictive utility for screening women as closely as possible to the time of childbirth, and establish clinical cutoffs in populations after complicated deliveries.

Conclusions:

Brief self-report screening concerning a woman’s emotional reactions to childbirth using our modified PDI tool can detect those likely to endorse CB-PTSD in the early postpartum. This may serve as the initial step of managing symptoms to ultimately prevent chronic manifestations.

Keywords: Childbirth-related PTSD (CB-PTSD), Factorial Analysis, Maternal Mental Health Assessment, PTSD Following Childbirth (PTSD-FC), Postpartum, Birth Trauma

Introduction

Each year, ~4 million American women give birth. While most have healthy deliveries, 20%−30% undergo a highly stressful childbirth experience (Mayopoulos et al., 2021a; Soet et al., 2003). A significant minority experience potentially life-threatening events and even maternal “near-miss” (nearly escaping death) in relation to childbirth, with rising rates in the U.S. (Firoz et al., 2022).

Increasing evidence reveals that women can develop post-traumatic stress disorder in response to childbirth (CB-PTSD) (Chan et al., 2022). Maternal CB-PTSD is estimated to occur in 3%–6% of the postpartum population (Ayers et al., 2018; Dekel et al., 2017) and in nearly 20% of those who experience complicated deliveries (Heyne et al., 2022; Yildiz et al., 2017). In the U.S., CB-PTSD affects ~120,000–240,000 American women annually (Dekel et al., 2017).

CB-PTSD can become a debilitating condition of the postpartum period and consequently impair the health of both the mother and her infant (Van Sieleghem et al., 2022). Women with CB-PTSD suffer from a range of symptoms that often include intrusive psychological phenomena such as nightmares about the trauma or recurrent involuntary memories; negative alterations in mood and cognition; and avoidance of reminders of the trauma (Dekel et al., 2020; Dekel et al., 2023a; Thiel et al., 2018; Van Sieleghem et al., 2022). Additionally, a core feature of CB-PTSD is heightened physiological reactivity to childbirth reminders (Chan et al., 2022). This suggests that the child themselves can become a cue of the trauma and can trigger maternal distress, to his or her own detriment. Problems in the early formation of maternal-infant attachment are strongly associated with CB-PTSD (Dekel et al., 2019a; Mayopoulos et al., 2021a), and interruption in attachment relations increases risk for behavior problems in children (Dagan et al., 2021) and mental illness in the adult offspring (Spruit et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2022). CB-PTSD can further result in avoidance of future pregnancies (Gottvall and Waldenström, 2002).

Currently, CB-PTSD is regarded as an underdiagnosed and, consequently, undertreated maternal psychiatric morbidity (Canfield and Silver, 2020). Because the symptoms of CB-PTSD are triggered in response to the childbirth event, the disorder has a clear onset. This offers a unique window of opportunities to identify postpartum women with traumatic stress reactions before a formal diagnosis can be confirmed, to increase the odds of potentially preventing CB-PTSD.

In non-postpartum samples, initial distress reactions to trauma exposure are well established to contribute to PTSD development (Thomas et al., 2012), which is understood as a failure to extinguish acute stress responses (Almeida et al., 2021; Horowitz, 1974). Peritraumatic (acute) subjective distress is an even stronger risk factor for PTSD than objective (stressor) elements of trauma (Ozer et al., 2003). Similarly, reactions of acute distress in response to childbirth, e.g., fear and perceived loss of control, are associated with CB-PTSD (Dekel et al., 2017; Mayopoulos et al., 2021a; Schobinger et al., 2020). These reactions appear to strongly predict CB-PTSD more than obstetrical interventions and/or complications (Chan et al., 2020; Dekel et al., 2017), and hence, constitute important information to identify women who are likely to develop CB-PTSD.

One of the most widely used measures to assess for acute stress reactions that may detect early signs of PTSD is the Peritraumatic Distress Inventory (PDI) (Brunet et al., 2001), a brief 13-item patient self-report questionnaire measuring emotional and physiological responses experienced during and shortly after a specified potentially traumatic event. The PDI has good psychometric properties in studies of individuals exposed to various forms of trauma (Bahari et al., 2017; Brunet et al., 2001; Bui et al., 2011; Bunnell et al., 2018; Jehel et al., 2005; Kianpoor et al., 2016; Rybojad and Aftyka, 2019; Rybojad et al., 2018). In non-postpartum samples, responses on the PDI predict subsequent PTSD symptoms severity and may be promising in informing subsequent PTSD diagnosis (Dell’oste et al., 2021; Ennis et al., 2021; Thomas et al., 2012). This suggests that responses on the PDI may offer important information in support of screening for CB-PTSD that is not captured using other screening tools.

At present, evidence supporting the PDI’s clinical potential to screen for CB-PTSD is lacking. Although several studies reveal that maternal CB-PTSD symptom severity is strongly and positively associated with a woman’s PDI score related to recent childbirth (Chan et al., 2020; Mayopoulos et al., 2021a), no study has established a clinical cutoff value to inform the detection and prediction of women with CB-PTSD.

To this end, we studied a sample of 3,039 women who recently gave birth. First, we investigated the factorial structure of the PDI to reveal its underlying constructs. Second, we determined the optimal cutoff value for identifying CB-PTSD in postpartum women.

Methods

Sample

This study is part of an investigation of the impact of childbirth experience on maternal mental health (Chan et al., 2020; Dekel et al., 2020; Mayopoulos et al., 2021a; Mayopoulos et al., 2021b). Women age 18+ years who gave birth to a live baby in the last six months were enrolled and provided information about their mental health and childbirth experience via an anonymous web survey that was created and administered via the REDCap platform (Harris et al., 2009). International recruitment was conducted over the periods of November 2016 to July 2018 and April 2020 to December 2020, using hospital announcements, social media, and professional organizations. The sample in this study consists of 3,039 participants who provided responses on the PDI and PCL-5. The project received exemption from the Partners HealthCare (Mass General Brigham) Human Research Committee.

Measures

The Peritraumatic Distress Inventory (PDI) (Brunet et al., 2001) is a 13-item self-report questionnaire measuring the degree of emotional and physiological distress endorsed during and shortly after a specified traumatic event. Items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale: 0: Not at All True; 1: Slightly True; 2: Somewhat True; 3: Very True; and 4: Extremely True. The items are summed to achieve total scores in the range 0–52. The PDI shows strong reliability and validity in non-postpartum samples (Bunnell et al., 2018; Carmassi et al., 2021; Rybojad and Aftyka, 2018).

The PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5) (Weathers et al., 2013) is a 20-item self-report questionnaire measuring the presence of the PTSD DSM-5 symptoms (American Psychiatric Association, 2013) and their severity. It is the standard measure recommended by the Veterans Affairs (VA) Medical Center for provisional diagnosis of PTSD (Bovin et al., 2016). Items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale: 0: Not At All; 1: A Little Bit; 2: Moderately; 3: Quite A Bit; and 4: Extremely. The items are summed to obtained total scores ranging from 0–80. The PCL-5 demonstrates excellent psychometric properties and strong correspondence with diagnostic clinician interview (Bovin et al., 2016; Wortmann et al., 2016). In accord with DSM-5 PTSD classification (American Psychiatric Association, 2013), participants were also asked to report the degree to which their symptoms caused impairment in functioning on a 5-point Likert scale. We classified individuals with high probability of CB-PTSD diagnosis, i.e., “positive PTSD screen”, based on (1) the suggested cutoff of 33 (Bovin et al., 2016), and (2) significant impairment in functioning (i.e., score of 2+ per DSM-5 classification). A negative PTSD screen indicating individuals as having a low probability of CB-PTSD diagnosis was determined if PCL-5 ≤ 5 and impairment in functioning < 2.

Data Analysis

Exploratory Graph Analysis

To examine the factorial structure of the PDI when used to assess childbirth trauma, we employed Exploratory Graph Analysis (EGA) (Golino et al., 2020) using the EGAnet R package (Golino and Christensen, 2020), a network psychometrics method that uses undirected network models to assess the psychometric properties of questionnaires. EGA was used to verify the number of factors, and the items associated with each factor, via a graphical lasso (Friedman et al., 2008). Network loadings, roughly equivalent to factor loadings, are reported using the net.loads function, with suggested general effect size guidelines for network loadings of 0.15 for small, 0.25 for moderate, and 0.35 for large (Christensen and Golino, 2021). Next, to examine the stability of the EGA, we followed the analysis with Bootstrap Exploratory Graph Analysis with 5,000 resampling cycles. Finally, we used the itemStability function to detect unstable items that hindered the factorial structure stability; unstable items switch factors in more than 25% of the iterations. We re-conducted the EGA without such items. The quality of fit of the final PDI version was estimated using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) via the lavaan Structural Equations Modeling (SEM) package (Rosseel, 2012).

Utility of the PDI as a screening test for CB-PTSD

Next, we examined the effectiveness of the revised 12-item PDI (Item 4 removed; see Results section for details) in differentiating between participants with high probability of having CB-PTSD (a score of 33+ for symptom severity on the PCL-5, and a score of 2+ in impairment in functioning) and those with a low probability of having CB-PTSD (PCL-5 ≤ 5, and a score < 2 in impairment in functioning). To do so, we calculated the optimal clinical cut-point by bootstrapping the optimal cut-point while maximizing the sensitivity and specificity (i.e., highest Youden’s index (Fluss et al., 2005): sensitivity + specificity – 1). We also reported the suggested indexes of the “number needed to diagnose” (NND) (Linn and Grunau, 2006), the number of patients who need to be examined to correctly detect one person with the disorder of interest in a study population of persons with and without the known disorder; “number needed to misdiagnose” (NNM) (Habibzadeh and Yadollahie, 2013), the number of patients who need to be tested in order for one to be misdiagnosed by the test; and the “likelihood to be diagnosed or misdiagnosed” (LDM) (Citrome and Ketter, 2013), with higher values of LDM (>1) suggesting that a test is more likely to diagnose than misdiagnose.

Results

Sample

In this sample (n=3,039), mean maternal age was 31.9 years (SD=4.6). The majority were married (92.8%), employed (73.9%), and completed a bachelor’s degree or higher (77.0%). Around half (54.9%) were primiparous. The majority (92.5%) gave birth full-term and delivered vaginally (70%), and engaged in skin-to-skin contact (86.9%) and roomed in with their infant (90.9%). A significant portion of women had complications: 29% reported obstetrical complications (Appendix Table 1); 6.1% had vaginal assisted deliveries, and 16.8% underwent emergency or unplanned Cesarean section; 7.5% had preterm deliveries (< 37 gestational weeks), and 12.7% had infant medical complications resulting in Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU) admission.

Measures

The PDI shows strong reliability in the current study (Cronbach’s α = 0.873). Average score was 11.25 (0–52). For the PCL-5, reliability is also high (Cronbach’s α = 0.934).

Exploratory Graph Analysis

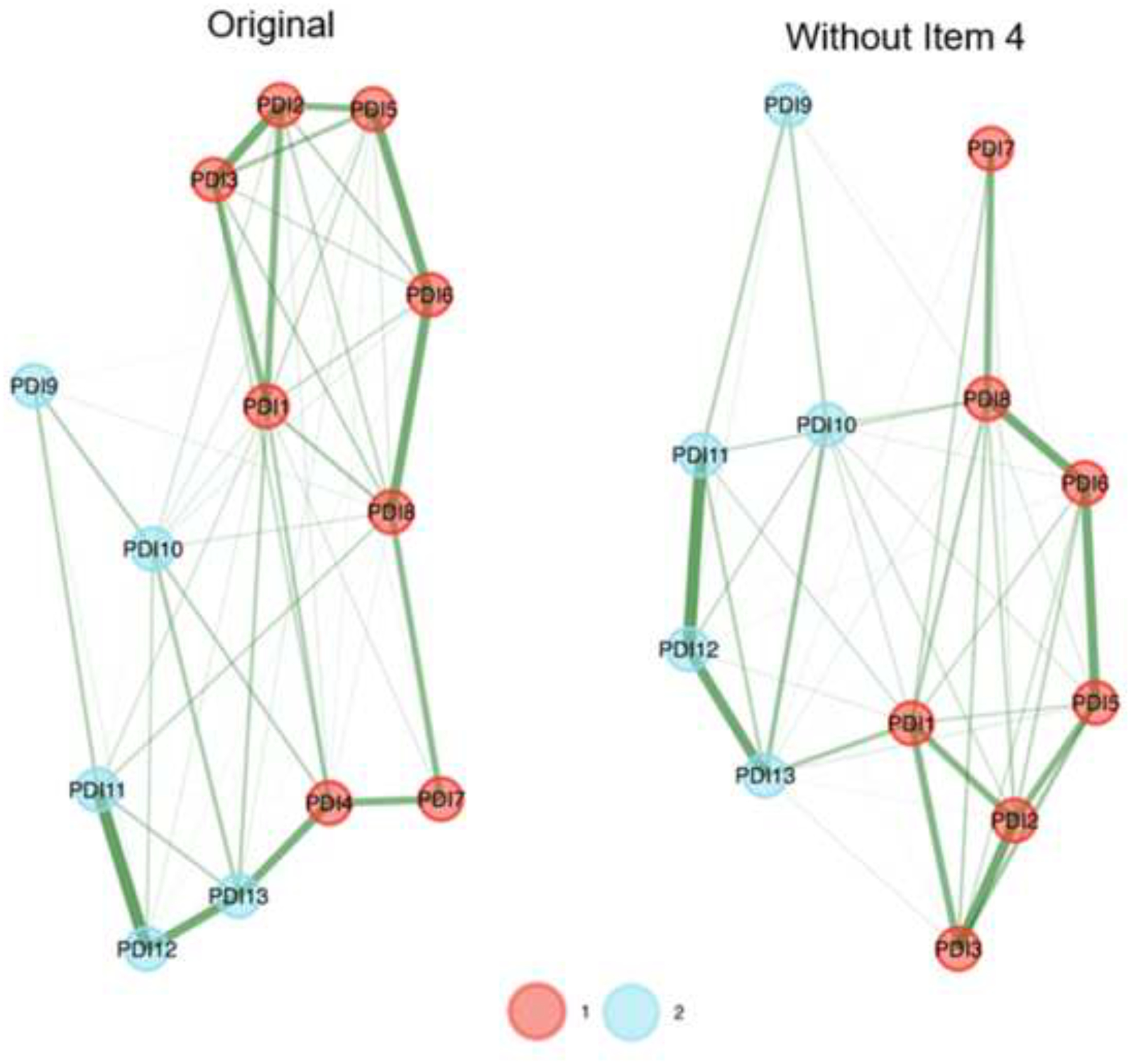

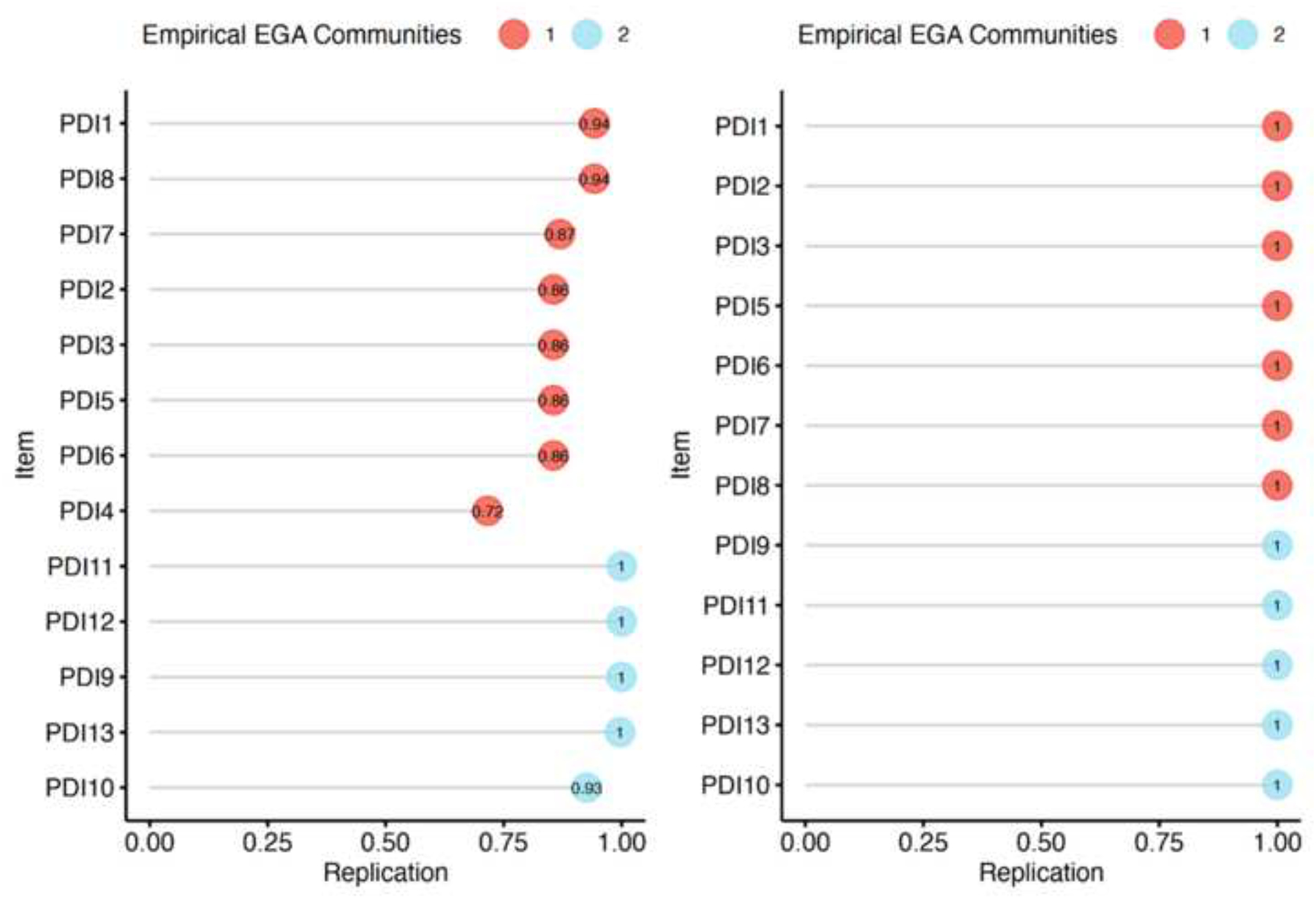

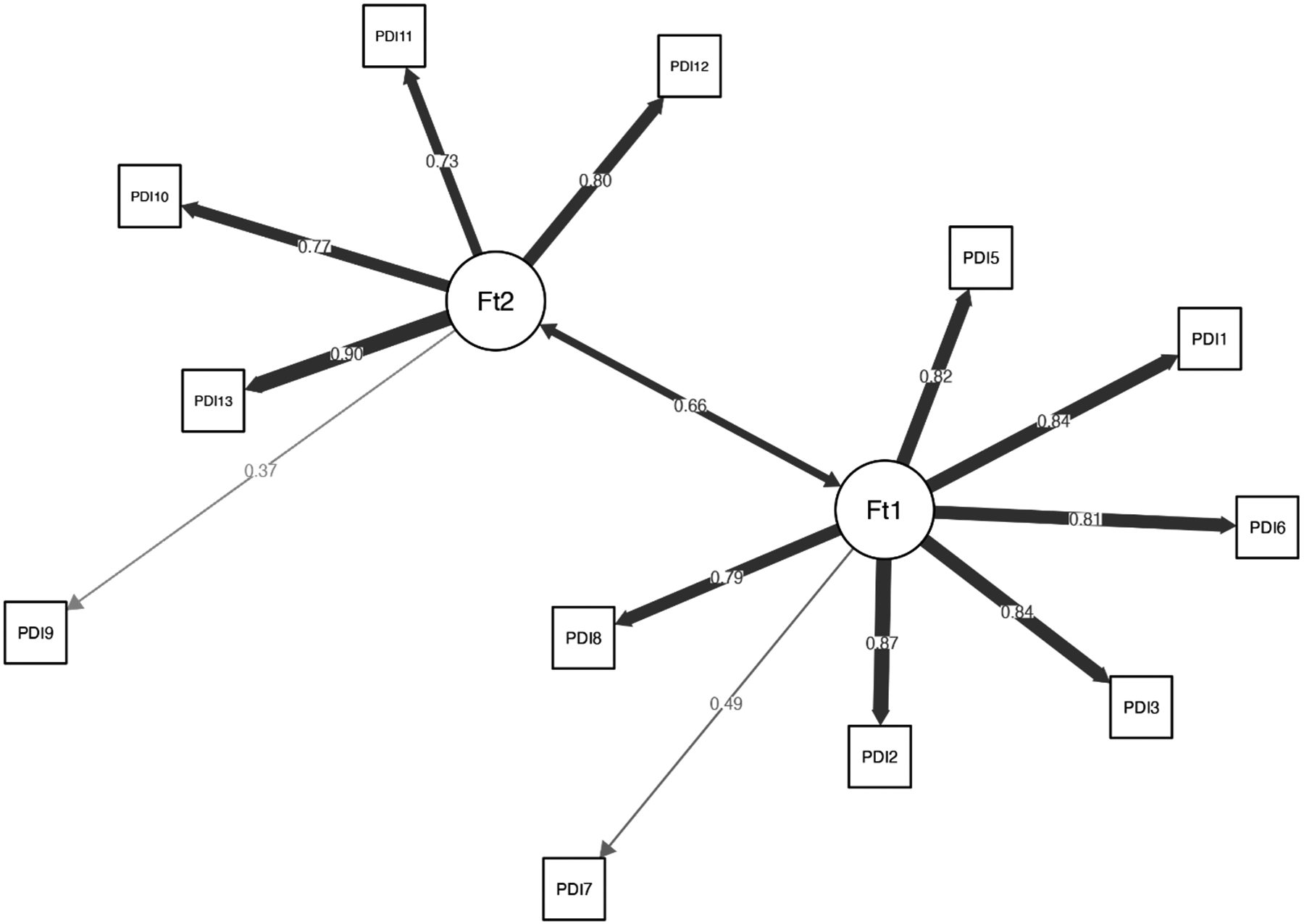

The EGA network results are presented in Figure 1, and network loadings are listed in Tables 1 and 2. Our analysis indicates that the PDI’s factorial structure comprises two factors: “Negative Emotions” (8 items), and “Bodily Arousal and Threat Appraisal” (5 items) (with Item 4, “I felt afraid for my own safety”, showing small-to-moderate cross-loading). When appraising the stability of the EGA by bootstrapping with 5,000 resampling cycles, the analysis indicated moderate-to-high stability: SE = 0.45, with confidence interval (CI) for the number of factors ranging from 1.12 to 2.87. The 2-factor solution was prevalent in 72.5% of the bootstrap samples, with 27.5% producing a 3-factor solution. By examining whether a lack of adequate item stability underlies the less-than-ideal factor solution (i.e., prevalence <75% of the leading solution), we found that Item 4 has poor stability (Figure 2). Hence, we omitted that item and re-conducted the EGA and bootstrap EGA, which revealed perfect factorial and item stability (SE = 0; 100% 2-factor solution). A confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was used to corroborate the EGA solution, and verify the factorial structure, CFI = 0.99, TLI = 0.98, RMSEA = 0.066 (90% confidence interval [CI] of 0.062, 0.069), SRMR = 0.053. The CFA is presented in Figure 3 and shows that the two factors of PDI correlate strongly, r = 0.66.

Figure 1.

Exploratory Graph Analysis (EGA) results of the original (left network) and the final (right network) Peritraumatic Distress Inventory (PDI) version. The factorial structure of the PDI comprises two factors: Factor 1 (red): Negative Emotions, and Factor 2 (blue): Bodily Arousal and Threat Appraisal. Thicknesses of lines (edges) indicate the strength of association.

Table 1.

Network loadings based on the Exploratory Graph Analysis (EGA) of the original Peritraumatic Distress Inventory (PDI)

| PDI Item Number | PDI Item | Negative Emotions | Bodily Arousal and Threat Appraisal |

|---|---|---|---|

| PDI2 | I felt sadness and grief. | 0.36 | – |

| PDI3 | I felt frustrated or angry. | 0.33 | – |

| PDI8 | I had the feeling I was about to lose control of my emotions. | 0.31 | – |

| PDI1 | I felt helpless. | 0.31 | – |

| PDI6 | I felt ashamed of my emotional reactions. | 0.30 | – |

| PDI5 | I felt guilty. | 0.29 | – |

| PDI4 | I felt afraid for my own safety. | 0.19 | 0.20 |

| PDI7 | I felt worried about the safety of others. | 0.19 | |

| PDI12 | I felt I might pass out. | – | 0.41 |

| PDI11 | I had physical reactions like sweating, shaking, and my heart pounding. | – | 0.31 |

| PDI13 | I thought I might die. | – | 0.27 |

| PDI10 | I was horrified by what I saw. | – | 0.17 |

| PDI9 | I had difficulty controlling my bowel and bladder. | – | 0.13 |

Note. General effect size guidelines for network loadings are 0.15 for small, 0.25 for moderate, and 0.35 for large. Item 4 showed small-to-moderate cross-loading.

Table 2.

Network loadings based on the Exploratory Graph Analysis (EGA) of the revised Peritraumatic Distress Inventory (PDI)

| PDI Item Number | PDI Item | Negative Emotions | Bodily Arousal and Threat Appraisal |

|---|---|---|---|

| PDI2 | I felt sadness and grief. | 0.38 | – |

| PDI8 | I had the feeling I was about to lose control of my emotions. | 0.34 | – |

| PDI3 | I felt frustrated or angry. | 0.33 | – |

| PDI6 | I felt ashamed of my emotional reactions. | 0.32 | – |

| PDI1 | I felt helpless. | 0.32 | – |

| PDI5 | I felt guilty. | 0.31 | – |

| PDI7 | I felt worried about the safety of others. | 0.14 | – |

| PDI12 | I felt I might pass out. | – | 0.42 |

| PDI11 | I had physical reactions like sweating, shaking, and my heart pounding. | – | 0.32 |

| PDI13 | I thought I might die. | – | 0.31 |

| PDI10 | I was horrified by what I saw. | – | 0.19 |

| PDI9 | I had difficulty controlling my bowel and bladder. | – | 0.13 |

Note. General effect size guidelines for network loadings are 0.15 for small, 0.25 for moderate, and 0.35 for large.

Figure 2.

Item stability of the original (left) and revised (right) Peritraumatic Distress Inventory (PDI). Stability below 75% is poor. The factorial structure of the PDI comprises two factors: Factor 1 (red): Negative Emotions, and Factor 2 (blue): Bodily Arousal and Threat Appraisal. EGA, Exploratory Graph Analysis.

Figure 3.

The final confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) for the revised Peritraumatic Distress Inventory (PDI). Ft1 indicates Factor 1: Negative Emotions, and Ft2 indicates Factor 2: Bodily Arousal and Threat Appraisal. Thicknesses of lines (edges) indicate the strength of association.

Utility of the PDI as a screening test for CB-PTSD

In this study, 290 participants (9.54%) were classified as having high probability of CB-PTSD (PCL-5 score ≥ 33 and score of ≥ 2 in impairment), and 209 as having low probability of CB-PTSD (PCL-5 ≤ 5 and impairment score <2). Bootstrapping the optimal cut-point of the revised PDI revealed that a cut-point of 15 produces a maximum Youden’s index (Fluss et al., 2005) of 0.81, with sensitivity of 88.28% and specificity of 92.82% (Figure 4). Using the revised PDI version and cut-point of 15, 1.23 patients are needed to be examined to correctly detect one person with the disorder of interest in a study population of persons with and without the known disorder (i.e., NND value, with 1 as the best possible value). Additionally, 10.18 patients need to be tested for one person to be misdiagnosed by the test (i.e., NNM value). The overall likelihood of being diagnosed compared with being misdiagnosed (i.e., LDM) is 8.26, which indicates high effectiveness in the diagnosis process.

Figure 4.

Results of the cut-point optimization process using bootstrap analysis. Panel A: Density of participants below and above the suggested cut-point of 15 in the revised Peritraumatic Distress Inventory (PDI) among the high (1) and low (0) CB-PTSD probability groups. Panel B: The Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve for the estimation process of the optimal cut-point, with the black dot indicating the highest Youden’s index. Panel C: Density of the optimal cut-point in the estimation process. Panel D: Density of the highest summed sensitivity and specificity scores of the revised PDI.

Discussion

Principal Findings

This study shows that the Peritraumatic Distress Inventory (PDI) used to assess acute distress in response to recent childbirth can inform identification of women who may endorse PTSD after childbirth (CB-PTSD). A score of 15 on our revised PDI (excluding Item 4, “I felt afraid for my own safety”) produced an optimal clinical cutoff associated with high sensitivity and specificity for CB-PTSD endorsement. Our analysis shows that 88% of women who likely meet criteria for CB-PTSD in the first months postpartum will be correctly identified based on their PDI score of 15+. This cutoff results in 8 times greater likelihood of a woman with CB-PTSD being identified rather than being missed based on her PDI screen. Additionally, 93% of women who likely do not meet CB-PTSD criteria will have a score <15.

Our results reveal that the PDI, originally designed to assess emotional and physiological responses experienced during and after a traumatic event, is an effective tool to assess acute distress stemming from the experience of childbirth. Exploratory factor analysis reveals two strongly correlated stable factors consisting of (1) negative emotions and (2) bodily arousal and threat appraisal related to childbirth. Hence, the PDI shows strong construct and convergent validity in postpartum assessment.

Results in the Context of Prior Work

This study is the first investigation of the PDI’s clinical utility to screen for CB-PTSD. Prior studies involving individuals exposed to other forms of trauma suggest that responses on the PDI can identify those likely to endorse PTSD (Bunnell et al., 2018; Ennis et al., 2021; Guardia et al., 2013; Nishi et al., 2010). Our results advance the literature by demonstrating the PDI’s potential use to screen women for childbirth-related traumatic stress reactions. We establish a clinical cutoff value of 15, designed for the postpartum population, derived from 12 items of the PDI. This cutoff falls in the range of reported cutoffs in non-postpartum samples for the 13-item PDI (cutoffs of 14–23) (Bunnell et al., 2018; Ennis et al., 2021; Guardia et al., 2013; Nishi et al., 2010; Rybojad and Aftyka, 2019). Our cutoff value suggests that women with CB-PTSD experience childbirth, commonly viewed as a happy event, with elevated distress levels at an magnitude similar to those of individuals who will develop PTSD following other forms of trauma.

Our findings reveal a two-factor structure consistent with the initial validation of the PDI in a sample of police officers who experienced/witnessed various traumatic events(Brunet et al., 2001) and later studies of trauma-exposed non-postpartum individuals (Bunnell et al., 2018; Jehel et al., 2005). The underlying factors are largely consistent with previous studies in support of an emotional (distress) component, as well as a cognitive (negative appraisal) factor coupled with hyper-physiological reactivity. The accuracy of our PDI specified to childbirth (sensitivity of 88%) accords with prior studies in non-postpartum samples, with sensitivity rates ranging from 70% to 90% (Bunnell et al., 2018; Ennis et al., 2021; Guardia et al., 2013; Nishi et al., 2010; Rybojad and Aftyka, 2019).

Clinical Implications

CB-PTSD is an underrecognized maternal mental health disorder affecting millions of women globally each year (Dekel et al., 2017). Early signs of CB-PTSD may go undetected in postpartum women, as recommendations for mental health screening in hospitals and clinics in the U.S. encompass only peripartum depression. Evidence suggests that screening alone for maternal mental health conditions can have benefits (ACOG Committee on Obstetric Practice, 2018a), and treatment may offer maximum benefit and reduce the duration of illness (Poobalan et al., 2007).

Here, we document that the PDI, a brief and simple patient self-report, when used to assess distress reactions to childbirth, can differentiate between women with and without CB-PTSD. Accordingly, it may serve as an initial feasible and cost-effective assessment screening before a diagnostic assessment is performed by a mental health professional. Adopting a simple screening tool would particularly benefit the needs of women who had medical complications, or their infants, who accordingly may not be able to engage in a more extensive evaluation.

Because the PDI can be administered in the acute post-trauma period, this screening could potentially be completed during maternity hospitalization stay. This, in turn, may direct at-risk women to receive early interventions and services (Dekel et al., 2023), and overcome a major challenge in screening post-discharge, involving the low attendance of follow-up postpartum visits (Attanasio et al., 2022). This potential for early assessment in the postpartum period differentiates the PDI from other available screening tools such as the PCL-5, which must be administered at least 1 month postpartum (Arora et al., 2023). Any new recommendations for CB-PTSD screening should be implemented after careful evaluations of the efficacy of such strategies, and considering recommended guidelines for clinical care.

Our findings are consistent with research on the role of the subjective elements of trauma in influencing how individuals cope psychologically in the aftermath (Ozer et al., 2003). Objective physical morbidity in childbirth and cases of near-miss strongly increase the risk for CB-PTSD (Andersen et al., 2012); nevertheless, how the event is experienced and appraised subjectively may profoundly determine maternal mental health outcome (Ford and Ayers, 2011; Halperin et al., 2015). Maternal appraisal could be influenced by perceived support, or lack thereof, during labor and delivery. Hence, the results of our study underscore the importance of promoting positive appraisals and protecting against negative appraisals of childbirth. This suggests opportunities for refining clinical care standards.

Research Implications

Our study provides proof of concept that the PDI could aid in universal screening of maternal CB-PTSD. We included postpartum women with medically complicated and uncomplicated deliveries, and our recommended clinical cutoff of 15 is derived from this sample. An important factor to consider in future research is the benefit of the PDI in screening targeted, high-risk women. Among this group are those with obstetrical and neonatal complications who may suffer from more severe CB-PTSD symptoms (Andersen et al., 2012; Chan et al., 2020; El Founti Khsim et al., 2022). Because acute stress is higher in these cases (Chan et al., 2020; Thiel and Dekel, 2020), and a significant portion, but not all, will develop PTSD (Bartal et al., 2023; Dekel et al., 2019b; Dekel et al., 2023a), adjusted (higher) clinical values defining these populations could be appropriate. Previous trauma exposure and PTSD increases vulnerability to the effects of subsequent trauma (Breslau et al., 1999; Dekel et al., 2016; Dekel et al., 2017) and may signify neurological sensitization and increased allostatic load; hence, a low degree of acute stress may signal CB-PTSD risk.

Although responses on the PDI are stable over time (Brunet et al., 2001; Bui et al., 2011; Bunnell et al., 2018), future research is warranted to determine the PDI’s utility when administered soon after childbirth to inform clinical recommendations in the immediate postpartum.

Strengths and Limitations

This study reveals for the first time the potential clinical utility of the PDI as a universal screening tool for CB-PTSD. Complementing previous work that has included other, non-childbirth, trauma when assessing the PDI’s properties, our study uses this instrument to measure women’s reactions to their recent childbirth, thus informing our understanding of this measure as applied to a postpartum population. Our sample size of 3,039 women is relatively large, enabling conclusions to be drawn with high confidence for our study population.

Several limitations of this study should be noted. We used a cross-sectional study design using a single time point of data collection, and our sample involved a relatively homogeneous population consisting mainly of middle-class Caucasian women in the U.S. Future work is warranted to examine the predictive utility of the PDI administered as closely as possible to the time of childbirth. Because people of low income and minoritized groups are at increased risk for traumatization (Chan et al., 2020; Iyengar et al., 2022), clinical cutoffs should be established in low socioeconomic and ethnically and racially diverse populations. Although we determined the likelihood for CB-PTSD using the well-validated PCL-5 patient self-report, which strongly accords with the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-5 (CAPS-5) (Lee et al., 2022), we did not perform clinical assessment to confirm diagnosis, or collect information about birth assistance. Our goal was to establish, as a first step, the PDI’s diagnostic utility in identifying women at risk for CB-PTSD, regardless of degree of birth trauma exposure. Future work warrants defining clinical values for high-risk populations exposed to obstetrical or neonatal complications, and those with past PTSD. Such work is likely to promote targeted screening.

Conclusions

This study provides evidence that the Peritraumatic Distress Inventory (PDI) is a useful tool to address the critical clinical gap in assessing early signs of psychiatric maternal morbidity associated with traumatic childbirth. We report that women who are likely to endorse CB-PTSD can be accurately identified based on their subjective experience of childbirth as assessed with the PDI. This instrument could be feasible to implement in the clinic as a low-cost, low-burden screening method. This may serve as an initial step in complementing the recommended routine screening for peripartum depression (ACOG Committee on Obstetric Practice, 2018a), in alignment with the recommendation of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) to conduct a full mental health assessment as part of a comprehensive postpartum visit (ACOG Committee on Obstetric Practice, 2018b). As maternal morbidity triggered by life-threatening childbirth-related events poses a significant public health concern in the U.S., our findings may inform early CB-PTSD screening in postpartum maternal populations, to advance progress toward the goals of efficient diagnosis and effective treatment for this disorder.

Acknowledgments:

The authors thank Gabriella Dishy (Department of Psychiatry, Massachusetts General Hospital) and Rasvitha Nandru (Department of Psychiatry, Massachusetts General Hospital) for assisting with data collection. Neither person received funding for this work.

Funding Statement:

Dr. Sharon Dekel was supported by grants from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R01HD108619, R21HD109546, and R21HD100817) and an ISF award from the Massachusetts General Hospital Executive Committee on Research. Dr. Kathleen Jagodnik was supported by the Mortimer B. Zuckerman STEM Leadership Postdoctoral Fellowship Program.

Role of the Funding Source:

The sponsors were not involved in study design; in the collection, analysis or interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit this article for publication.

Appendix Table 1. Obstetrical complications of study sample

| Variable | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Obstetric complications/conditions | 881 (28.99%) |

| Hemorrhage/excessive blood loss | 129 (4.24%) |

| Placenta-related | 43 (1.41%) |

| Preeclampsia | 70 (2.30%) |

| Hysterectomy | 3 (0.10%) |

| Hypertension | 45 (1.48%) |

| Hypotension | 20 (0.66%) |

| Cord prolapse | 5 (0.16%) |

| Nuchal cord | 48 (1.58%) |

| Shoulder dystocia | 28 (0.92%) |

| Fetal intolerance | 164 (5.40%) |

| Failed labor progression | 98 (3.22%) |

| Gestational diabetes | 3 (0.10%) |

| Meconium presence/meconium aspiration syndrome | 33 (1.09%) |

| Infection | 29 (0.95%) |

| Laceration/tearing | 39 (1.28%) |

| Arrest of descent | 2 (0.07%) |

| Episiotomy | 15 (0.49%) |

| Abnormal fetal positioning/presentation | 136 (4.48%) |

| Oligohydramnios | 4 (0.13%) |

| Uterine rupture | 6 (0.20%) |

| Preterm premature rupture of membranes (PPROM) | 8 (0.26%) |

| Not reported | 15 (0.49%) |

Note: % for each complication is calculated out of N=3,039 and includes multiple complications reported per participant. Placenta-related complications include placenta abruption, placenta accreta, retained placenta, placenta previa, etc. Abnormal fetal positioning/presentation includes breech, asynclitic presentation, etc. “Not reported” refers to women who responded “yes” to survey item about experiencing obstetric complications but did not specify the complication.

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement of any potential conflict of interest:

All authors report no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Kathleen M. Jagodnik, Department of Psychiatry, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts

Tsachi Ein-Dor, School of Psychology, Reichman University, Herzliya, Israel

Sabrina J. Chan, Department of Psychiatry, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts

Adi Titelman Ashkenazy, Department of Psychiatry, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts

Alon Bartal, School of Business Administration, Bar-Ilan University, Ramat Gan, Israel

Robert L. Barry, Athinoula A. Martinos Center for Biomedical Imaging, Department of Radiology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Charlestown, Massachusetts, USA; Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts; Harvard-Massachusetts Institute of Technology Health Sciences & Technology, Cambridge, Massachusetts

Sharon Dekel, Department of Psychiatry, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts

References

- ACOG Committee on Obstetric Practice, 2018a. Screening for Perinatal Depression. Committee Opinion Number 757, November. [Google Scholar]

- ACOG Committee on Obstetric Practice, 2018b. Presidential task force on redefining the postpartum visit committee on obstetric practice. Obstet. Gynecol.131(5), e140–50.29683911 [Google Scholar]

- Almeida FB, Pinna G, Barros HMT, 2021.The role of HPA axis and allopregnanolone on the neurobiology of major depressive disorders and PTSD. Int. J. Molec. Sci. 22(11), 5495. 10.3390/ijms22115495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association, 2013. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.). 10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen LB, Melvaer LB, Videbech P, Lamont RF, Joergensen JS, 2012. Risk factors for developing post- traumatic stress disorder following childbirth: a systematic review. Acta Obstetr. Gynecolog. Scand. 91(11), 1261–1272. https://obgyn.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/j.1600-0412.2012.01476.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arora IH, Woscoboinik GG, Mokhtar S, Quagliarini B, Bartal A, Jagodnik KM, Barry RL, Edlow AG, Orr SP, Dekel S*. Establishing the validity of a diagnostic questionnaire for childbirth-related post-traumatic stress disorder. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 2023. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2023.11.1229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attanasio LB, Ranchoff BL, Cooper MI, Geissler KH, 2022. Postpartum visit attendance in the United States: a systematic review. Women’s Health Issues 32(4), 369–375. 10.1016/j.whi.2022.02.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayers S, Wright DB, Thornton A, 2018. Development of a measure of postpartum PTSD: the city birth trauma scale. Front. Psychiatry. 9, 409. 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahari FB, Malek MDA, Japil AR, Endalan LM, Mutang JA, Ismail R, Ghani FNA, 2017. Psychometric Evaluation of Malay Version of Peritraumatic Distress Inventory (M-PDI) and Peritraumatic Dissociative Experiences Questionnaire (M-PDEQ) using the sample of flood victims in Kuching, Sarawak, Malaysia. Soc. Sci. 2017;12(6), 907–911. [Google Scholar]

- Bartal A, Jagodnik KM, Chan SJ, Babu MS and Dekel S, 2023. Identifying women with postdelivery posttraumatic stress disorder using natural language processing of personal childbirth narratives. Am. J. Obstetr & Gynecol MFM, 5(3), 100834. 10.1016/j.ajogmf.2022.100834 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bovin MJ, Marx BP, Weathers FW, Gallagher MW, Rodriguez P, Schnurr PP, Keane TM, 2016. Psychometric properties of the PTSD Checklist for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders–Fifth Edition (PCL-5) in veterans. Psycholog. Assess. 28(11), 1379. 10.1037/pas0000254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau N, Chilcoat HD, Kessler RC and Davis GC, 1999. Previous exposure to trauma and PTSD effects of subsequent trauma: results from the Detroit Area Survey of Trauma. Am. J. Psychiatry, 156(6), 902–907. 10.1176/ajp.156.6.902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunet A, Weiss DS, Metzler TJ, Best SR, Neylan TC, Rogers C, Fagan J, Marmar CR, 2001. The Peritraumatic Distress Inventory: a proposed measure of PTSD criterion A2. Am. J. Psychiatry. 158(9), 1480–1485. 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.9.1480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bui E, Brunet A, Olliac B, Very E, Allenou C, Raynaud J-P, Claudet I, Bourdet-Loubere S, Grandjean H, Schmitt L, Birmes P, 2011. Validation of the Peritraumatic Dissociative Experiences Questionnaire and Peritraumatic Distress Inventory in school-aged victims of road traffic accidents. Eur. Psychiatry. 26(2), 108–111. 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2010.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunnell BE, Davidson TM, Ruggiero KJ, 2018. The Peritraumatic Distress Inventory: Factor structure and predictive validity in traumatically injured patients admitted through a Level I trauma center. J. Anx. Disord. 55, 8–13. 10.1016/j.janxdis.2018.03.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canfield D, Silver RM, 2020. Detection and prevention of postpartum posttraumatic stress disorder: a call to action. Obstetr. & Gyn. 136(5), 1030–1035. DOI: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000004093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmassi C, Bui E, Bertelloni CA, Dell’Oste V, Pedrinelli V, Corsi M, Baldanzi S, Cristaudo A, Dell’Osso L, Buselli R, 2021. Validation of the Italian version of the peritraumatic distress inventory: Validity, reliability and factor analysis in a sample of healthcare workers. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol, 12(1), 1879552. 10.1080/20008198.2021.1879552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan SJ, Ein-Dor T, Mayopoulos PA, Mesa MM, Sunda RM, McCarthy BF, Kaimal AJ, Dekel S, 2020. Risk factors for developing posttraumatic stress disorder following childbirth. Psychiatry. Res. 290, 113090. 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan SJ, Thiel F, Kaimal AJ, Pitman RK, Orr SP, Dekel S, 2022. Validation of childbirth-related posttraumatic stress disorder using psychophysiological assessment. Am. J. Obstetr. Gynecol. 227(4), 656–659. 10.1016/j.ajog.2022.05.051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen AP, Golino H, 2021. On the equivalency of factor and network loadings. Behav. Res. Meth. 53(4), 1563–1580. 10.3758/s13428-020-01500-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Citrome L, Ketter T, 2013. When does a difference make a difference? Interpretation of number needed to treat, number needed to harm, and likelihood to be helped or harmed. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 67(5), 407–411. 10.1111/ijcp.12142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dagan O, Schuengel C, Verhage ML, van Ijzendoorn MH, Sagi-Schwartz A, Madigan S, Duschinsky R, Roisman GI, Bernard K, Bakermans-Kranenburg M, Bureau J-F, Volling BL, Wong MS, Colonnesi C, Brown GL, Eiden RD, Pasco Fearon RM, Oosterman M, Aviezer O, Cummings EM, 2021. Collaboration on attachment to multiple parents and outcomes synthesis. Configurations of mother- child and father- child attachment as predictors of internalizing and externalizing behavioral problems: an individual participant data (IPD) meta- analysis. New Dir. Child and Adol. Dev. 180, 67–94. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/cad.20450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dekel S, Chan SJ, Jagodnik KM, 2023a. Book Chapter: Childbirth-Related Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (CB-PTSD). International Handbook of Perinatal Mental Health Disorders, Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group. In press. [Google Scholar]

- Dekel S, Ein-Dor T, Dishy GA, Mayopoulos PA, 2020. Beyond postpartum depression: posttraumatic stress-depressive response following childbirth. Arch. Women’s Mental Health. 23(4), 557–564. 10.1007/s00737-019-01006-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dekel S, Ein-Dor T, Berman Z, Barsoumian IS, Agarwal S and Pitman RK, 2019b. Delivery mode is associated with maternal mental health following childbirth. Arch. Women’s Mental Health, 22, 817–824. 10.1007/s00737-019-00968-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dekel S, Gilberston M, Orr S, Rauch S, Nellie W, Pitman R., 2016. Trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder. In: Stern TA, Fava M, Wilens T, Rosenbaum JF (Eds.): Massachusetts General Hospital Comprehensive Clinical Psychiatry 2/e. Philadelphia, PA, Elsevier, 380–394. [Google Scholar]

- Dekel S, Papadakis JE, Quagliarini B, Pham CT, Pacheco-Barrios K, Jagodnik KM, Nandru R. Preventing post-traumatic stress disorder following childbirth: A systematic review and meta-analysis. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 2023. doi: doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2023.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dekel S, Stuebe C, Dishy G, 2017. Childbirth induced posttraumatic stress syndrome: a systematic review of prevalence and risk factors. Front. Psychol. 8, 560. 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dekel S, Thiel F, Dishy G, Ashenfarb AL, 2019a. Is childbirth-induced PTSD associated with low maternal attachment?. Arch. Women’s Mental Health 22, 119–122. 10.1007/s00737-018-0853-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dell’oste V, Bertelloni CA, Cordone A, Pedrinelli V, Cappelli A, Barberi FM, Amatori G, Gravina D, Bui E, Carmassi C, 2021. Acute peritraumatic distress predicts post-traumatic stress disorder at 6 months in patients with bipolar disorder followed during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacology 53, S582. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2021.10.860 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- El Founti Khsim I, Martínez Rodríguez M, Riquelme Gallego B, Caparros-Gonzalez RA and Amezcua-Prieto C, 2022. Risk factors for post-traumatic stress disorder after Childbirth: a systematic review. Diagnostics. 12(11), 2598. 10.3390/diagnostics12112598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ennis N, Anton M, Bravoco O, Ridings L, Hunt J, deRoon-Cassini TA, Davidson T, Ruggiero K, 2021. Prediction of posttraumatic stress and depression one-month post-injury: A comparison of two screening instruments. Health Psychol. 40(10), 702. 10.1037/hea0001114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Firoz T, Romero CLT, Leung C, Souza JP, Tunçalp Ö, 2022. Global and regional estimates of maternal near miss: a systematic review, meta-analysis and experiences with application. BMJ Global Health. 7(4), e007077. 10.1136/bmjgh-2021-007077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford E, Ayers S, 2011. Support during birth interacts with prior trauma and birth intervention to predict postnatal post-traumatic stress symptoms. Psychol. & Health. 26(12), 1553–1570. 10.1080/08870446.2010.533770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fluss R, Faraggi D, Reiser B, 2005. Estimation of the Youden Index and its associated cutoff point. Biometrical Journal: J. Mathemat. Meth. Biosci. 47(4), 458–472. 10.1002/bimj.200410135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman J, Hastie T, Tibshirani R, 2008. Sparse inverse covariance estimation with the graphical lasso. Biostatistics. 9(3), 432–441. 10.1093/biostatistics/kxm045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golino HF, Christensen AP, 2020. EGAnet: Exploratory graph analysis: A framework for estimating the number of dimensions in multivariate data using network psychometrics. Available at https://cran.r-project.org/package=EGAnet

- Golino H, Shi D, Christensen AP, Garrido LE, Nieto MD, Sadana R, Thiyagarajan JA, Martinez-Molina A, 2020. Investigating the performance of exploratory graph analysis and traditional techniques to identify the number of latent factors: A simulation and tutorial. Psycholog. Meth. 25(3), 292. 10.1037/met0000255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottvall K, Waldenström U, 2002. Does a traumatic birth experience have an impact on future reproduction?. BJOG: Int. J. Obstetr. & Gyn. 109(3), 254–260. 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2002.01200.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guardia D, Brunet A, Duhamel A, Ducrocq F, Demarty AL, Vaiva G, 2013. Prediction of trauma-related disorders: a proposed cutoff score for the peritraumatic distress inventory. Primary Care Compan. CNS Disord. 15(1), 27121. doi: 10.4088/PCC.12l01406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habibzadeh F, Yadollahie M, 2013. Number needed to misdiagnose: a measure of diagnostic test effectiveness. Epidemiology. 24(1), 170. DOI: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e31827825f2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halperin O, Sarid O, Cwikel J, 2015. The influence of childbirth experiences on women’s postpartum traumatic stress symptoms: A comparison between Israeli Jewish and Arab women. Midwifery. 31(6), 625–632. 10.1016/j.midw.2015.02.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N,Conde JG, 2009. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J. Biomed. Informat. 42(2), 377–381. 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyne CS, Kazmierczak M, Souday R, Horesh D, Lambregste-van den Berg M, Weigl T, Horsch A, Oosterman M, Dikmen-Yildiz P, Garthus-Niegel S, 2022. Prevalence and risk factors of birth-related posttraumatic stress among parents: A comparative systematic review and meta analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 94, 102157. 10.1016/j.cpr.2022.102157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz M, 1974. Stress response syndromes: character style and dynamic psychotherapy. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 31(6), 768–781. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1974.01760180012002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyengar AS, Ein-Dor T, Zhang EX, Chan SJ, Kaimal AJ and Dekel S, 2022. Increased traumatic childbirth and postpartum depression and lack of exclusive breastfeeding in Black and Latinx individuals. Int. J. Gynaecology Obstetrics: The Official Organ of the Int. Federation Gynaecology Obstetrics. 158(3), 759. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.14280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jehel L, Brunet A, Paterniti S, Guelfi JD., 2005. Validation of the Peritraumatic Distress Inventory’s French translation. Can. J. Psychiatry. Revue Canadienne de Psychiatrie. 50(1), 67–71. 10.1177/070674370505000112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kianpoor M, Amouchie R, Raghibi M, Hesam S, Mazidi M, Abasian M, Saffarian Z, Masoumi S, Sadeghkhani A, 2016. Validity and reliability of Persian versions of peritraumatic distress inventory (PDI) and dissociative experiences scale (DES). Acta Medica. 32, 1493. [Google Scholar]

- Lee DJ, Weathers FW, Thompson-Hollands J, Sloan DM, Marx BP, 2022. Concordance in PTSD symptom change between DSM-5 versions of the Clinician Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS-5) and PTSD Checklist (PCL-5). Psycholog. Assessm. 34(6), 604. 10.1037/pas0001130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linn S, Grunau PD, 2006. New patient-oriented summary measure of net total gain in certainty for dichotomous diagnostic tests. Epidemiolog. Perspect. Innov. 3(1), 1–9. 10.1186/1742-5573-3-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayopoulos GA, Ein-Dor T, Dishy GA, Nandru R, Chan SJ, Hanley LE, Kaimal AJ, Dekel S, 2021a. COVID-19 is associated with traumatic childbirth and subsequent mother infant bonding problems. J. Affect. Disord. 282, 122–125. 10.1016/j.jad.2020.12.101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayopoulos GA, Ein-Dor T, Li KG, Chan SJ, Dekel S, 2021b. COVID-19 positivity associated with traumatic stress response to childbirth and no visitors and infant separation in the hospital. Sci. Rep. 11(1), 13535. 10.1038/s41598-021-92985-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishi D, Matsuoka Y, Yonemoto N, Noguchi H, Kim Y, Kanba S, 2010. Peritraumatic Distress Inventory as a predictor of post- traumatic stress disorder after a severe motor vehicle accident. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 64(2), 149–156. 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2010.02065.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozer EJ, Best SR, Lipsey TL, Weiss DS, 2003. Predictors of posttraumatic stress disorder and symptoms in adults: a meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 129(1), 52. 10.1037/0033-2909.129.1.52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poobalan AS, Aucott LS, Ross L, Smith WC, Helms PJ, Williams JH, 2007. Effects of treating postnatal depression on mother-infant interaction and child development: systematic review. Br. J. Psychiatry. 191, 378–386. 10.1192/bjp.bp.106.032789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosseel Y, 2012. lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. J. Statist. Software. 48, 1–36. DOI: 10.18637/jss.v048.i02 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rybojad B, Aftyka A, 2018. Validity, reliability and factor analysis of the Polish version of the Peritraumatic Distress Inventory. Psychiatria. Polska, 52(5), 887–901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rybojad B, Aftyka A, 2019. Peritraumatic distress among emergency medical system employees: A proposed cut-off for the Peritraumatic Distress Inventory. Ann. Agricult. Environm. Med. 26(4). 10.26444/aaem/105436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rybojad B, Aftyka A, Samardakiewicz M, 2018. Factor analysis and validity of the Polish version of the Peritraumatic Distress Inventory in mothers of seriously ill children. J. Clin. Nurs. 27(21–22), 3945–3952. 10.1111/jocn.14597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schobinger E, Stuijfzand S, Horsch A, 2020. Acute and post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms in mothers and fathers following childbirth: a prospective cohort study. Front. Psychiatry. 11, 562054. 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.562054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soet JE, Brack GA, DiIorio C, 2003. Prevalence and predictors of women’s experience of psychological trauma during childbirth. Birth. 30(1), 36–46. 10.1046/j.1523-536X.2003.00215.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spruit A, Goos L, Weenink N, Rodenburg R, Niemeyer H, Stams GJ, Colonnesi C, 2020. The relation between attachment and depression in children and adolescents: A multilevel meta-analysis. Clin. Child Family Psychol. Rev. 23, 54–69. 10.1007/s10567-019-00299-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiel F and Dekel S, 2020. Peritraumatic dissociation in childbirth-evoked posttraumatic stress and postpartum mental health. Arch. Women’s Mental Health, 23: 189–197. 10.1007/s00737-019-00978-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiel F, Ein-Dor T, Dishy G, King A and Dekel S, 2018. Examining symptom clusters of childbirth-related posttraumatic stress disorder. The Primary Care Companion for CNS Disorders, 20(5), 26912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas É, Saumier D, Brunet A, 2012. Peritraumatic distress and the course of posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms: A meta-analysis. Canad. J. Psychiatry 57(2), 122–129. https://doi.org/10.1177/070674371205700209 https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/070674371205700209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Sieleghem S, Danckaerts M, Rieken R, Okkerse JM., de Jonge E, Bramer WM, Lambregtse – van den Berg M, 2022. Childbirth related PTSD and its association with infant outcome: A systematic review. Early Human Dev. 105667. 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2022.105667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weathers FW, Litz BT, Keane TM, Palmieri PA, Marx BP, Schnurr PP, 2013. The PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5). Scale available from the National Center for PTSD. www.ptsd.va.gov. [Google Scholar]

- Wortmann JH, Jordan AH, Weathers FW, Resick PA, Dondanville KA, Hall-Clark B, Foa EB, Young-McCaughan S, Yarvis JS, Hembree EA, Mintz J, Peterson AL, Litz BT, 2016. Psychometric analysis of the PTSD Checklist-5 (PCL-5) among treatment-seeking military service members. Psycholog. Assess. 28(11), 1392. 10.1037/pas0000260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yildiz PD, Ayers S, Phillips L, 2017. The prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder in pregnancy and after birth: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Aff. Disord. 208, 634–645. 10.1016/j.jad.2016.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Li J, Xie F, Chen X, Xu W, Hudson NW, 2022. The relationship between adult attachment and mental health: A meta-analysis. J. Personality Social Psychol. 123(5), 1089. 10.1037/pspp0000437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]