Introduction

The actin cytoskeleton is an integral tool kit used by cells to assemble a wide range of structures with optimal biophysical properties to drive cell migration, maintain complex cell morphology, support vesicular trafficking and complete cytokinesis (Blanchoin et al., 2014; Jeruzalska and Mazur, 2023; Mavrakis and Juanes, 2023; Nirschl et al., 2017). The formation of these versatile actin networks relies on the ability of actin monomers to assemble into long, flexible polymers that, in turn, can be used by a myriad of actin-binding proteins (ABPs) to build complex networks and specialized structures. Much of what we know about these dynamic processes stems from using purified actin monomers in conjunction with in vitro reconstitution assays, such as bulk F-actin (co)sedimentation and pyrene fluorescence (or light scattering) assays as well as imaging-based approaches such as (microfluidics-assisted) total internal reflection (TIRF) microscopy and bead motility assays. The common theme for these techniques is that they all report on actin filament nucleation, turnover and remodeling in the presence or absence of ABPs; but they do so using different read-outs and providing various levels of mechanistic detail, as described in these excellent reviews (Bernheim-Groswasser et al., 2005; Hansen et al., 2013; Heier et al., 2017; Shekhar, 2017; Sykes and Plastino, 2022; Wioland et al., 2022).

Whereas remodeling of the actin cytoskeleton by ABPs has been studied for many decades, less attention has been paid to how the nature of the actin molecules themselves contributes to actin network dynamics. This is in part because most studies on the regulation of actin filaments by ABPs used yeast, which expresses only one actin isoform. On the other hand, actin is abundantly present in skeletal muscle, which to date is still the most used source to obtain purified mammalian actin for in vitro experiments. The latter is not only due to muscle being a convenient and cheap way to obtain large quantities of actin, but also avoids some of the challenges associated with obtaining pure populations of recombinantly expressed actin. As a result, much of our understanding of actin is derived from in vitro studies using either yeast or skeletal muscle α-actin. However, mammals can express up to six canonical actin isoforms, comprising 2 non-muscle or cytoplasmic actins and 4 muscle actins, each of which can undergo a myriad of post-translational modifications (PTMs), thereby creating a diversity in actin filament composition that can rival the diversity in ABPs (Balta et al., 2021; Rouyère et al., 2022; Terman and Kashina, 2013; Varland et al., 2019). How these different isoforms and actin modifications influence the ability of actin to polymerize, as well as how these differences affect the actin-remodeling activities of ABPs remains poorly understood. This is mainly due to 2 reasons: (1) natively folded mammalian actins require the unique eukaryotic chaperonin containing TCP-1 or TCP-1 ring complex (CCT/TriC), precluding expression in bacterial systems, and (2) the promiscuity of recombinant actin to copolymerize with endogenous actin isoforms, even in lower vertebrate systems. Thus, to investigate how amino acid composition and PTMs influence intrinsic actin filament dynamics as well as interaction of actin filaments with ABPs, there is a need for novel approaches to produce pure populations of specific mammalian actin isoforms as well as actins carrying a specific mutation or posttranslational modification.

In this review, we will first describe the different actin isoforms and novel insights into their unique requirements for correct N-terminal processing and posttranslational modification, with specific emphasis on those PTMs that have influenced and guided the strategies developed for recombinant expression and purification of natively folded mammalian actin. Next, we will give an overview of the methods used to purify actin isoforms from tissue as well as to produce recombinant actin isoforms that carry obligate N-terminal and internal modifications. For each of these strategies, we will address the criteria that need to be fulfilled to obtain a pure population of correctly folded actin as well as discuss their mechanism, advantages and limitations. Finally, we will describe how these methods can be employed to study novel actin-like proteins that are likely to form dynamic polymers, but due to low tissue expression cannot be purified endogenously and thus will have to rely on these novel recombinant tools to be characterized in the future.

Mammalian cells express multiple actin isoforms with unique N-terminal signatures

Actin is one of the most highly conserved proteins across all eukaryotes. Despite the high selective pressure to maintain the amino acid composition of actin, extensive sequencing of a wide range of tissues demonstrated early on that mammalian cells evolved to express multiple actin isoforms (Vandekerckhove and Weber, 1978). These actins are encoded by different genes that arose from at least two gene duplication events, one that has been hypothesized to give rise to the cytoplasmic actins, and a second one that introduced the more divergent muscle actins (Erba et al., 1988, 1986; Miwa et al., 1991). This group of actin genes enable the expression of different isoforms by the same cell, while at the same time also provide a way to tune the expression level of each actin isoform in a specific tissue or organ. As a result, non-muscle cells mainly produce β-actin (ACTB) and γ-actin (ACTG1), whereas α-actin is the predominant isoform in skeletal (ACTA1) and cardiac (ACTC1) muscle. As their names imply, smooth muscle α-actin (ACTA2) and γ-actin (ACTG2) are enriched in vascular and enteric smooth muscle tissues, respectively.

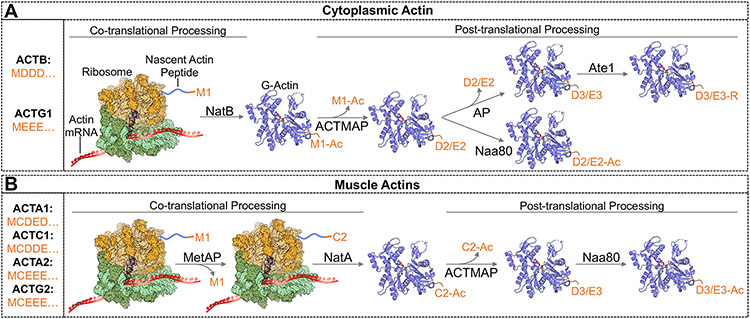

Actin isoforms are 93-99% identical in protein sequence and are distinguished mainly by their unique N-termini, which differ in amino acid sequence and undergo different co-and posttranslational processing (Fig. 1). In case of ACTB and ACTG1, the N-terminal initiator methionine becomes acetylated during translation, presumably by N-acetyltransferase B (NatB) (Van Damme et al., 2012). Upon folding, the acetylated methionine is removed by a novel cysteine protease C19orf54, which was renamed Actin Maturation Protease or ACTMAP (Haarer et al., 2023). This exposes the following acidic residue (D2 in ACTB, E2 in ACTG1) that is then acetylated by the actin-specific N-acetyltransferase NatH/NAA80 (Drazic et al., 2018; Goris et al., 2018; Rebowski et al., 2020) (Fig 1A). Alternatively, albeit infrequently, the N-terminal acidic residue of either ACTB or ACTG1 can be removed by an unknown aminopeptidase (AP) and the third acidic residue in the sequence is arginylated by the enzyme Ate1 (Karakozova et al., 2006). The function of arginylated cytoplasmic actins is not fully resolved (Saha et al., 2010). Arginylated β-actin has been shown to preferentially localize to the leading edge of the cell upon induction of cell migration (Pavlyk et al., 2018), whereas arginylation of γ-actin promotes it’s immediate proteasomal degradation (Zhang et al., 2010). Unlike cytoplasmic actins, maturation of muscle actins is initiated by cotranslational removal of the initiator methionine, which results in an N-terminal cysteine residue that becomes co-translationally acetylated, presumably by N-acetyltransferase A (NatA) (Van Damme et al., 2011). This newly acetylated cysteine is then removed by ACTMAP (Haahr et al., 2022), leaving behind an acidic residue (3rd residue in the amino acid sequence) that is subsequently N-terminally acetylated by Naa80 (Fig 1B). Interestingly, besides being selective for actin, both ACTMAP and Naa80 were shown to also bind profilin-actin complexes, which stimulates the activity of either enzyme compared to their activity on actin by itself (Haahr et al., 2022; Rebowski et al., 2020; Ree et al., 2020). This is important given that profilin-actin constitutes the largest fraction of G-actin in cells.

Figure 1: N-terminal maturation of different actin isoforms.

A. In the cytoplasmic actins, the N-terminal methionine becomes acetylated during translation, presumably by N-acetyltransferase B (NatB). Upon folding, Ac-M1 is removed by the protease ACTMAP, which exposes an acidic residue (D2 in β-actin, E2 in γ-actin) that is then acetylated by the actin-specific N-acetyltransferase NAA80. For a small fraction of the cytoplasmic actins, the N-terminal acidic residue can also be removed, exposing the second acidic residue, which then becomes arginylated by Ate1. Of note, arginylation of γ-actin destines it for degradation by the proteasome, whereas arginylated β-actin can be found in cells. B. Maturation of muscle actin is initiated by co-translational removal of the initiator methionine by a methionine amino peptidase (MetAP) and the subsequent acetylation of the N-terminal cysteine residue, likely by N-acetyltransferase A (NatA). Ac-C2 is then removed posttranslationally by ACTMAP, leaving behind an acidic residue (D3 or E3) that is subsequently acetylated by Naa80. Models of the 70S ribosome and G-actin were adapted from PDB ID 7K00 (Watson et al., 2020) and 6NAS (Arora et al., 2023), respectively, using Pymol version 2.5.

In addition to a unique N-terminus, muscle and non-muscle actins can be further discerned by 22 other residues throughout the rest of the molecule (Fig. 2A), although only 18 of these distinguish β-actin and γ-actin from muscle actin, and the remaining 4 residues are unique to a specific isoform of muscle actin. Among these 18 residues, 4 are conserved substitutions (i.e. valine swapped for isoleucine or glutamine swapped for asparagine), and only 6 of the remaining 14 residues have side chains that are exposed either on the surface of the actin monomer or within the nucleotide binding pocket (Fig. 2A and 2B). In F-actin, only one of these residues, S365 in cytoplasmic actins and A367/366 in muscle actins, remains completely exposed to the solvent, whereas 3 of these residues (L176, C272, and F279 in cytoplasmic actin and M178/177, A274/273, and Y281/281 in muscle actin, respectively) form a cluster on subdomain 1 at the interface between neighboring actin monomers in the actin filament and thus are exposed on the very barbed end of F-actin (Fig 2A). Of note, many of these divergent residues can be modified by either oxidation or phosphorylation, which could further add to differences in intrinsic actin polymerization or interaction of actin with ABPs. This holds true for M178, which when oxidized in conjunction with M190 and M269, causes inhibition of muscle actin polymerization and destabilizes actin filaments (Dalle-Donne et al., 2002), whereas oxidation of β-actin-specific residue C272 in conjunction with C374 by H2O2 results in actin monomers that are unable to polymerize and have impaired profilin binding (Lassing et al., 2007). Additionally, S365 in β-actin and γ-actin and Y281 in muscle actins have been reported to be phosphorylated in high-throughput studies curated by PhosphoSitePlus® (Hornbeck et al., 2015), however the kinases that phosphorylate these sites as well as the functional impact of phosphorylation of these sites on actin dynamics remains to be identified.

Figure 2:

Differences between cytoplasmic and muscle actins in G- and F-actin. A-C. Model of filamentous β-actin (A) and a close-up of a single actin monomer (B) indicated by the dashed box in A, were adapted from PDB ID 8DNH (Arora et al., 2023), and individual actin monomers are indicated in in white, light blue, and slate. Residues that differ between cytoplasmic and muscle actin (C) are color-coded and shown on the filamentous and monomeric actin structures. Conserved substitutions are shown in yellow, divergent residues that are accessible on the surface of the actin monomer are shown in orange, divergent residues that are accessible in the nucleotide binding pocket are indicated in green and divergent residues that are buried in the actin fold are shown in magenta. All models were generated using Pymol version 2.5.

Tissue-specific purification of actin monomers enriched in specific isoforms

For many years, the tissue-specific expression of different mammalian actins has been exploited to purify actin monomers that are enriched in a specific isoform. The high abundance of actin in skeletal muscle provides an easy way to produce preparative quantities of α-actin and has contributed to the predominant use of this isoform to study actin dynamics in reconstitution assays. By contrast, the ubiquitous expression of the cytoplasmic actins makes that these isoforms are difficult to isolate individually, since these actins copolymerize and consequently co-purify from many different tissues (Schafer et al., 1998). Exception to this rule, are erythrocytes and platelets, which were shown to mainly express ACTB (100% in erythrocytes and 85% of total actin in platelets) (Landon et al., 1977; Pinder and Gratzer, 1983), and thus, platelet actin has become the standard to study this actin isoform. Given that most tissues were shown to produce more β-actin than γ-actin, the field has resorted to using smooth muscle γ-actin derived from chicken gizzard (Saborio et al., 1979), which after N-terminal processing shares the same 3 N-terminal residues as cytoplasmic γ-actin (Fig. 1). However, aside from the N-terminus, it should be emphasized that smooth muscle γ-actin is more similar to the muscle actin isoforms than to cytoplasmic γ-actin (Fig. 2C), thus these results might have to be interpreted with caution. For example, it was shown that DIAPH3 (mDia2) is required to specifically polymerize the β-actin filaments that form the cytokinetic ring during cytokinesis (Chen et al., 2017), whereas γ-actin at the cell poles is decreased by inhibition of DIAPH1 (mDia1) (A. Chen et al., 2021), suggesting that formins can distinguish between cytoplasmic actin isoforms. In line with this, in vitro analysis showed that mDia2 preferentially stimulated the polymerization of platelet actin, which mainly consists of β-actin; compared to chicken gizzard actin, which is mainly comprised of smooth muscle γ-actin (Chen et al., 2017). However, a recent study using human β-actin and γ-actin purified from S. cerevisiae demonstrated that mDia1 shows similar nucleation and elongation rates for both cytoplasmic actins, raising the question whether the proposed specificity of formins for different actin isoforms is rather due to a difference between muscle and non-muscle γ-actin or to the skewed ratio of β-actin versus γ-actin in platelet actin preparations (Haarer et al., 2023). Additionally, it should not be excluded that this formin specificity depends on a specific PTM or a set of PTMs that might be absent in yeast.

Methods developed to obtain endogenous non-muscle actin from tissues and cells

Non-muscle actins have historically been purified directly from non-muscle tissues or eukaryotic cells because actin expressed in and purified from bacterial systems is not fully folded and thus functionally compromised. Early attempts to purify cytoplasmic actins from non-muscle tissues exploited the insolubility of actin filaments in Triton X-100 to precipitate F-actin from platelet lysates. Bound ABPs were removed by increasing the salt concentration to 0.6M KCl and repeated rounds of polymerization-depolymerization of the pelleted actin (Rosenberg et al., 1981) (Fig. 3A). This purification strategy was further refined by the observation that initial extraction of G-actin from non-muscle tissues could be greatly improved using a lysis buffer that contained both Triton-X100 and high salt (Schafer et al., 1998). In addition to retrieving actin from the insoluble fraction, the high affinity of actin for DNase I has been exploited to isolate actin monomers using DNase I affinity chromatography (Lazarides and Lindberg, 1974) (Fig. 3B). This purification was further streamlined by prior removal of major contaminants by anion-chromatography using DE53-cellulose, MonoQ or DEAE cellulose (Schafer et al., 1998). Various adaptations of this method were later adopted to purify recombinant actin from insect cells (Bai et al., 2014; Bookwalter and Trybus, 2006; Debold et al., 2010). While the yield can vary slightly depending upon the tissue or cell type used, on average about 1 mg actin can be obtained per 100 g of tissue, 1.5 L of insect cells or 3L of blood (Bai et al., 2014; Schafer et al., 1998). Unfortunately, elution of actin from DNaseI requires high concentrations of formamide, which has been shown to inactivate a substantial amount of the purified actin monomers (Aspenstrom et al., 1992; Aspenstrom and Karlsson, 1991; Haarer et al., 2023; Schafer et al., 1998). This will ultimately lower the final protein yield and potentially affect the longevity of the remaining actin for use after purification.

Figure 3. Methods to isolate endogenous and recombinant actin from tissues and cells.

A. After cell lysis, actin filaments (F-actin) can be precipitated with 1% Triton X-100. Actin-binding proteins are dissociated by increasing the salt concentration and are separated from F-actin by centrifugation. Actin monomers are retrieved by depolymerization to G-buffer. B. Actin monomers are directly captured on DNaseI affinity resin from which they can be eluted using formamide and further purified by a round of polymerization-depolymerization and/or gel filtration. Damaged actin monomers are removed through one or more rounds of actin polymerization and depolymerization C. Profilin (PFN)-actin complexes are captured on poly-L-proline resin, eluted by DMSO and passed over hydroxyapatite resin to separate PFN-β-actin and PFN-γ-actin complexes. Actin monomers are stored as paracrystals and retrieved by a round of polymerization-depolymerization and gel filtration before use in in vitro assays. D. Actin monomers are bound by HIS-tagged Gelsolin (G4-6), which can be captured on NiNTA resin. Actin monomers are then retrieved from G4-6 by EGTA.

Another issue with DNaseI affinity chromatography is that these preparations still consist of a mix of isoforms. As a result, human actin recombinantly expressed in insect cells and purified in this fashion was reported to be contaminated with endogenous actin (Müller et al., 2013). To date, only one method has been optimized to separate endogenous β- and γ-actin derived from non-muscle tissue. This approach specifically isolates actin bound to profilin (PFN) using poly-L-proline affinity chromatography, followed by separation of PFN-β-actin and PFN-γ-actin by hydroxyapatite chromatography (Segura and Lindberg, 1984) (Fig. 3C). Actin and PFN are then separated by KPO4 paracrystal formation of actin, a cycle of polymerization/depolymerization, and gel filtration. This approach has also been shown to separate chicken β-actin (100% identical to human β-actin) from endogenous actin expressed in S. cerevisiae, allowing the production of large quantities of pure non-muscle actin (Karlsson, 1988). It should be noted that like DNaseI affinity chromatography, this approach also requires harsh conditions to elute PFN-actin from both the poly-L-proline and hydroxyapatite resins, again raising concerns about the yield and stability of the purified actin. This method was slightly improved upon by showing that β-actin can functionally replace native yeast actin (ACT1) in S. cerevisiae, thereby allowing purification of β-actin from yeast without the need for a hydroxyapatite column purification step (Karlsson et al., 1991). The same genetic trick was used in a recent study to isolate codon-optimized β-actin or γ-actin from S. cerevisiae using DNaseI affinity chromatography (Haarer et al., 2023). Of note, studies using either purification strategy found that yeast-purified cytoplasmic actin had a similar critical concentration for actin polymerization as skeletal muscle α-actin (Aspenstrom and Karlsson, 1991; Haarer et al., 2023). Additionally, modification of the N-terminus of β-actin by mutation of D3 and D4 to lysines had negligible effect on the ability of actin to polymerize, however did impact the ability of a single-headed fragment of myosin II (myosin S1) to decorate actin filaments (Aspenstrom and Karlsson, 1991). Altogether, this suggests that the actin monomers surviving these harsh elution conditions retain both their ability to polymerize and interact with ABPs, and therefore can be used in in vitro studies albeit with caution.

A better understanding of the interaction between actin and the monomer sequestering protein, Gelsolin (GSN), paved the way for a more gentle method to purify actin monomers that omits the need for denaturants and other harsh conditions (Fig. 3D). GSN is an actin severing and capping protein that can bind and sequester actin monomers with its C-terminal calcium-sensitive half, referred to as G4-6 (residues 434-782 of human gelsolin). These characteristics were employed to isolate actin monomers from tissues and cell lysates by binding to HIS-tagged G4-6 and capture of the GSN-actin complexes by NiNTA affinity chromatography, after which actin monomers could be eluted from G4-6 by gentle calcium chelation with EGTA (Ohki et al., 2009). Like previous approaches, this method has been used to obtain recombinantly expressed actin and actin mutants (Ceron et al., 2022; Liu et al., 2018; Ohki et al., 2009; Teng et al., 2019) as well as endogenous cytoplasmic actin from tissues (Funk et al., 2019) and cells (Drazic et al., 2018), although it should be noted that recombinant expression proved to greatly increase the final yield of actin to as much as 200 mg of actin per liter of insect cell culture under optimized conditions (Ohki et al., 2012). This G4-6 method yields preparations of actin that are free of actin-binding contaminants, but still consist of multiple actin isoforms as well as actins that can carry an array of PTMs (Ceron et al., 2022). Thus, to use this approach to its full potential, it should be combined with genetically engineered yeast strains that express a desired human actin isoform in conjunction with actin-modifying enzymes. Alternatively, with the advent and continuous improved efficacy of CRISPR/cas9 knockout and knock-in approaches, G4-6 affinity chromatography might come to age as a prime purification workflow in future custom engineered mammalian cell lines.

Purification of recombinant actin isoforms

Over the years, mouse models and in vitro studies have proven that actin isoforms are non-redundant, which is due to differences in both their nucleotide sequence and protein sequence (Bunnell and Ervasti, 2011; Vedula and Kashina, 2018). However, to date, we have a very limited understanding of how small differences in protein composition lead to altered biological functions of actin isoforms. In addition, the rise of proteomic screening has made it clear that many of the surface-exposed residues on actin can undergo some type of posttranslational modification, although the impact of these modifications on actin dynamics and ABP function remains understudied. Finally, there are a fair number of disease-related mutations in actin of which the pathogenic mechanism remains unclear. Together, this has led to increasing efforts to develop approaches to recombinantly express and obtain pure preparations of specific actin isoforms, actin mutations, and actin with specific PTMs. In the following sections we will describe the major issues in recombinant expression of actin isoforms and how these have been tackled, in terms of 1) obtaining correctly folded actin, 2) introduction of obligate PTMs, including correct N-terminal processing and 3) success in isolating recombinantly expressed actin from endogenous actin in the expression system of choice.

Efficient release from the heterologous CCT/TRiC complex.

One hurdle to recombinant expression of actin is its strict requirement for the CCT/TRiC chaperonin complex, which is absent in prokaryotes, thus precluding purification of natively folded actin in classic bacterial expression systems (Balchin et al., 2018). However, it seems there might be slight differences between heterologous CCT/TRiC complexes of different vertebrate species, limiting their folding capacity to specific actin isoforms. This is exemplified by the fact that mammalian β-actin and γ-actin can be expressed in yeast, whereas skeletal muscle actin becomes misfolded (Altschuler et al., 2009; Haarer et al., 2023). A screen of residues that are unique to skeletal muscle actin elucidated that this is due to residue N299, whose mutation to the yeast residue (N299I) or β-actin/γ-actin residue (N299T) enabled skeletal muscle actin to be produced in yeast (Altschuler et al., 2009). This should be an important consideration when investigating mutant actins and different actin isoforms. Indeed, in a study of 19 different mutant skeletal muscle actins that have been linked to congenital myopathies, two mutations, L94P and E259V, resulted in misfolded actin that failed to be released by the CCT complex (Costa et al., 2004). A similar observation was made for disease-related mutations in smooth muscle α-actin (R149C) and cardiac α-actin (R312H) (J. Chen et al., 2021; Vang et al., 2005). Hydrogen/deuterium exchange mass spectrometry (H/DX-MS) analysis elucidated that each of these conserved residues are located at the interface between the actin molecule and the CCT/TRiC complex (Balchin et al., 2018), however it remains unclear if modification of this interface alone is sufficient to stall the CCT/TRiC complex. To that point, release of the R149C mutant of smooth muscle α-actin (ACTA2) from insect CCT/TRiC was stimulated by introducing the N299T mutation (J. Chen et al., 2021). This suggests that there may be specific differences between the CCT/TRiC complexes from lower and higher eukaryotic cells and more has to be learned about the intricacies of actin folding in order to optimally produce specific native actin isoforms in different lower and higher vertebrate systems.

Minimize contamination with heterologous actins –

Both DNaseI and G4-6 affinity chromatography have been widely used to isolate recombinant actin, however these monomer sequestering proteins do not discriminate between actin from different species, resulting in recombinant preparations that are potentially contaminated by endogenous actins (Bergeron et al., 2010). In addition, early studies focused mostly on investigating disease-related actin proteins carrying non-conservative mutations, making it possible to separate mutant and endogenous actins using ion-exchange chromatography (Aspenstrom and Karlsson, 1991; Sutoh et al., 1991). However, to isolate actin mutants that do not alter the charge of the molecule or to separate recombinant and endogenous actin, it is necessary to either attach an affinity tag to the recombinant protein and/or use the single endogenous actin gene expressed in yeast as the basis for mutagenesis. Unfortunately, fusion of Dictyostelium discoideum actin with an N-terminal decahistidine has been observed to induce aggregation of the protein at low concentrations (Abe et al., 2000), and in line with this, expression of hexahistidine tagged-actin in ACT1 deficient yeast slightly impaired cell proliferation (Buzan et al., 1999). This problem was solved by a recent study that genetically engineered S. cerevisiae to solely express a codon-optimized version of either human β- or γ-actin (Haarer et al., 2023). However, as mentioned above, this system may not work well for muscle actin isoforms or for actins that require obligate PTMs that are not supported by budding yeast.

In this case, another approach to obtain pure recombinant actin is to fuse a histidine (His)-tagged Thymosin-β-4 (T4β) molecule to the C-terminus of actin through a flexible cleavable linker (Noguchi et al., 2007). The His-tagged T4β binds to the cleft between subdomains 1 and 3, thereby blocking barbed end growth and thus enabling bound actin monomers to be isolated on an affinity resin (Fig. 4A). The last residue of actin is Phe, providing a natural cleavage site for chymotrypsin, which can be used to release the actin monomers from the resin without leaving additional residues from the linker or T4β. Other contaminating proteins can then be removed from the eluted actin monomers by additional ion-exchange chromatography and/or a round of polymerization/depolymerization. This approach has been successfully used to produce pure intact actin from Pichia pastoris, insect cells and mammalian cells (A et al., 2020, 2019; Chin et al., 2022; Funk et al., 2019; Hatano et al., 2018; Lu et al., 2015). However, some care has to be taken when using chymotrypsin as a few studies have reported that, depending on the concentration and incubation time, chymotrypsin can cleave other sites in actin, thereby generating actin that shows compromised polymerization (Ceron et al., 2022; Collins and Elzinga, 1975; Jacobson and Rosenbusch, 1976). Fortunately, these cleaved actin products can be easily removed by anion chromatography and/or a round of polymerization/depolymerization (A et al., 2020). While this actin-T4β fusion requires some optimization of the chymotrypsin cleavage step and possibly an extra purification step to remove cleaved actin molecules, it has become a convenient and robust approach for the purification of recombinant actin.

Figure 4. Methods to express and purify recombinant actin.

A. Recombinant actin is expressed as a fusion construct consisting of an N-terminal ubiquitin moiety, the actin isoform of interest and a C-terminal Thymosin-β4-His (T4β-His) moiety in a Pichia pastoris strain with stably integrated Naa80 and SETD3 (pick-ya actin). The N-terminal marker is removed co-translationally by endogenous ubiquitin proteases, exposing the acidic residue on actin that needs to be acetylated by Naa80. Meanwhile, H73 is also co-translationally methylated by SETD3. After cell lysis, modified actin monomers are isolated by binding of T4β-His to NiNTA. Actin monomers are retrieved by chymotrypsin cleavage and further purified by polymerization-depolymerization. B. Recombinant actin is expressed with an N-terminal HIS-Flag-TEV tag in mammalian cells. Recombinant actin undergoes methylation of H73 normally during translation. After cell lysis, actin monomers (endogenous and recombinant) are bound to G4-6. Recombinant actin is captured on FLAG-resin and eluted by EGTA. Subsequent TEV cleavage exposes the acidic residue that can be acetylated by incubation with recombinant Naa80. Modified actin monomers are then isolated from unmodified monomers, His-TEV, and His-Naa80 using G4-6 affinity purification over NiNTA. Functional, fully modified monomers can be further purified by a round of polymerization-depolymerization.

To omit the use of chymotrypsin, a recent study instead expressed actin with an N-terminal HIS-Flag dual-affinity tag that can be removed by TEV protease cleavage immediately adjacent to the first residue (D or E) of post-processed actin (Ceron et al., 2022). This is a surprising approach, given that some limited evidence suggests that N-terminally His-tagged actin has a propensity to aggregate during purification (Abe et al., 2000). However, one marked difference is that this approach incubated the lysate containing the recombinant actin with G4-6, which may help to maintain monodispersity of the HIS-Flag-TEV-actin and prevent aggregation (Fig. 4B). Since the N-terminus is occluded from modification during expression, N-terminal processing occurs in vitro by ectopic addition of Naa80 after proteolytic removal of the N-terminal tag (see below). While more laborious than using C-terminally fused T4β, this strategy does have the advantage of avoiding promiscuous cleavage by chymotrypsin while at the same time preserving mammalian PTMs on actin. Additionally, this method was also reported to produce 3 mg of actin per 1 L of mammalian cell culture, which is considerably higher than the 0.5 mg of actin per 1 L of Pichia pastoris (Ceron et al., 2022; Hatano et al., 2020, 2018).

N-terminal processing and obligate PTMs of actin

Maturation of actin molecules requires their N-terminus to undergo extensive processing that consists of several steps, but ultimately results in acetylation of the utmost N-terminal acidic residue of all actin isoforms. For many years, actin N-terminal acetylation was postulated to promote a more negatively charged filament end that could affect actin polymerization or interaction of actin with ABPs. A number of studies indeed demonstrated that the charge of the N-terminus of actin has a profound effect on the interaction between actin and myosins, however also showed that this interaction was rather regulated by the number of acidic residues than by acetylation of the utmost residue, leaving open the question what role this modification plays in the regulation of actin dynamics (Abe et al., 2000; Aspenstrom and Karlsson, 1991; Cook et al., 1992; Sutoh et al., 1991). Recently, the functional impact of N-terminal acetylation of actin was revisited after the discovery of the actin-specific N-acetyltransferase, Naa80 (Drazic et al., 2018; Rebowski et al., 2020). Knockout of Naa80 from cells resulted in a higher F-to G-actin ratio, an increase in filopodia number and faster cell migration (Drazic et al., 2018). This suggests that N-terminal acetylation indeed affects actin dynamics or interaction of actin with ABPs, although the underlying mechanism remains unknown as non-acetylated actin was contradictorily shown to slow mDia1 polymerization (Drazic et al., 2018). In line with a role for N-terminal acetylation of actin, knockout mice of ACTMAP, the protease that frees up the actin N-terminus for acetylation by Naa80, affected skeletal muscle strength and sarcomere organization (Haahr et al., 2022). Whereas these studies emphasize that correct N-terminal processing of actin is a requirement, future work will have to delineate how N-acetylation contributes to actin dynamics and interaction of F-actin with ABPs.

Besides acetylation of the N-terminus, about half of all conserved surface-exposed residues of actin have been reported to undergo posttranslational modification (see reviews by (Terman and Kashina, 2013; Varland et al., 2019). Typically, these modifications are limited to only on a subset of actin molecules, thus providing cells with a way to connect signaling pathways with tight spatiotemporal control of actin network remodeling. This is different for methylation of H73 in β-actin (H75/74 in muscle actins), which is an obligate modification that has been found in all actin isoforms. Two independent studies identified SETD3 to be the actin-specific histidine methyltransferase that mediates this modification in human cell lines, flies (Kwiatkowski et al., 2018) and in mice (Wilkinson et al., 2019a). What is more, in vitro methylation of H73 was observed for human β-actin that was refolded upon purification from bacterial inclusion bodies (Kwiatkowski et al., 2018). By contrast, human β-actin can be expressed and folded in yeast, however this actin lacks His73 methylation since yeast lack a SETD3 homologue (Kalhor et al., 1999). Interestingly, yeast-purified actin could not be methylated by SETD3 in vitro, unless it was first denatured (Kwiatkowski et al., 2018), suggesting that methylation by SETD3 occurs cotranslationally (Martin-Benito, 2002; Stemp et al., 2005). Biochemical characterization of β/γ-actin isolated from SETD3 knockout Hela cells indicated that methylation of H73 drives polymerization, as shown before (Kwiatkowski et al., 2018; Nyman et al., 2002). In support of this function, SETD3 knockout cells showed decreased migration and reduced phalloidin staining (Kwiatkowski et al., 2018; Wilkinson et al., 2019). This is a surprisingly mild phenotype for a modification that is present on the majority of actin molecules. The absence of this modification in S. cerevisiae actin further suggests that it might contribute to a very specialized function of actin or a dedicated interaction of actin with a specific ABP in higher vertebrates. In addition, SETD3 knockout mice were viable and did not shown any overt phenotype besides decreased smooth muscle contraction during partition, leading to delayed birth (Wilkinson et al., 2019).

Altogether, this suggests that recombinant actin should at the minimum undergo correct N-terminal processing and potentially methylation of H73 in order to be considered native actin. Consequently, this requires extra post-purification steps when expressing N-terminally tagged actin that cannot undergo N-terminal processing or when producing actin from yeast, which cannot methylate H73. For this purpose, the pick-ya-actin system was engineered to express actin in yeast cells that are stably expressing human Naa80 and SETD3 (Hatano et al., 2020) (Fig 4A). In addition, actin isoforms are expressed as N-terminal fusions with a ubiquitin moiety that is readily removed by resident Pichia pastoris ubiquitin proteases, thereby exposing the N-terminal Asp or Glu residue for acetylation by stably integrated human Naa80 (Chin et al., 2022; Hatano et al., 2020, 2018) (Fig 4A). In addition, Ceron and colleagues optimized a strategy to produce HIS-Flag-TEV-actin in mammalian cells, which will preserve methylation of H73 during expression but has to be N-terminally processed after purification in vitro (Ceron et al., 2022) (Fig. 4B).

Application of recombinant actin purification tools in the characterization of novel actin-like proteins

The technologies and approaches highlighted above will be particularly important in the investigation of a growing list of actin-like proteins. Sequencing of the human genome identified genes that are highly related to β-actin, however for many of these genes it remains an open question when and where they are expressed and whether they have the capacity to polymerize into filaments like the canonical actin isoforms. Emerging actin-like proteins include ActBL, ACTL7A and POTE-actin fusion proteins. ActBL (ACTBL2) or κ-actin is 91.5% identical to β-actin and was found by mass spectrometry analysis as a novel interactor of Gelsolin (Mazur et al., 2016). Follow-up studies further showed that overexpressed HA-tagged ActBL colocalizes with β- and γ-actin in different cellular actin structures and that stable knockout as well as overexpression of ActBL affects the migration and invasion of melanoma cells (Malek et al., 2021) and ovarian cancer cells (Topalov et al., 2021). In addition to ActBL, β-actin shares >90% identity with one of the domains found in a number of POTE genes. The primate-specific POTE gene family consists of 14 closely related paralogs that are dispersed over 8 chromosomes. All 14 genes are derived from the ANKRD26 ancestral gene, and share a translated ankyrin repeat domain (Hahn et al., 2006). Four of these (POTEE, POTEF, POTEJ, and POTEI) are also predicted to have a β-actin-like domain that is in frame with the ankyrin repeat domain. These POTE-actin fusion genes are ubiquitously expressed and become acutely upregulated in breast cancers and other cancers (Bera et al., 2006), where they are correlated to poor prognosis and high recurrence (Barger et al., 2018; Lee et al., 2006). Despite this strong link to cancer, the function of POTE genes remains a mystery. However, one study in breast cancer cells did demonstrate that POTEF localizes to the actin cortex (Lee et al., 2006), suggesting that that this POTE-actin can co-assemble with β-actin structures and thereby serve a role in actin dynamics. Finally, several testis-specific actin-like proteins (ACTL7A, ACTRT1/2 and ACTL9) were identified. Knockout or mutation of each of these actin-like proteins has been linked to male infertility in both humans and mice (Dai et al., 2021; Xin et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2022). Each of these actin-like proteins localize to the subacrosomal actin network, however only ACTL7A has been shown to strongly bind to the actin monomer sequestering protein, profilin-4. In addition, its depletion led to a complete loss of subacrosomal actin filaments in ACTL7A knockout spermatids (Ferrer et al., 2023). The observation that ACTBL, POTEF and ACTL7A have been shown to localize to actin networks combined with the fact that the β-actin nucleotide binding pocket is conserved in each of these actin-like proteins, not only suggests that these actin-like proteins might have the capacity to polymerize into filaments, but also raises questions about factors that help to direct their correct actin fold, such as the CCT/TRiC complex. As such, the recombinant expression and purification approaches mentioned above, might prove invaluable to study the biochemical and biophysical properties of these potentially novel actin isoforms.

Summary and future perspectives

In this review, we discussed how the purification of actin has evolved over the years in response to novel insights into its folding requirements, its complex N-terminal maturation, and its interaction with ABPs such as profilin, gelsolin and thymosin-β-4. In addition, we highlighted how the field exploited the tractability of yeast genetics to develop more affordable methods to produce a variety of actin isoforms and actin isoforms that display a given PTM or set of PTMs for use in some common in vitro reconstitution assays. Going forward, genetically engineered cell lines will prove to be invaluable when used in conjunction with these purification strategies, especially in the study of specific actin PTMs or the isolation of specific actin isoforms. This will pave the way to gain novel insights into the role and mechanism of isoform-specific actin modification induced by pathological conditions such as carcinogenesis, actin-rod formation and cardiomyopathies. In addition, several actin-like proteins have been identified whose functions remain mysterious. The methods described above will be instrumental to not only understand how these novel actin-like proteins may influence β- and γ- actin networks, but also to determine if the canonical actin family should be expanded to include these novel isoforms.

Acknowledgments

This review was supported by NIGMS R01 GM136925 to DJK and NIGMS R01 GM138448 to SJ.

Footnotes

Declarations of interest

None

References

- A M, Fung TS, Francomacaro LM, Huynh T, Kotila T, Svindrych Z, Higgs HN, 2020. Regulation of INF2-mediated actin polymerization through site-specific lysine acetylation of actin itself. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 117, 439–447. 10.1073/pnas.1914072117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A M, Fung TS, Kettenbach AN, Chakrabarti R, Higgs HN, 2019. A complex containing lysine-acetylated actin inhibits the formin INF2. Nat Cell Biol 21, 592–602. 10.1038/s41556-019-0307-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abe A, Saeki K, Yasunaga T, Wakabayashi T, 2000. Acetylation at the N-Terminus of Actin Strengthens Weak Interaction between Actin and Myosin. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 268, 14–19. 10.1006/bbrc.1999.2069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschuler GM, Dekker C, McCormack EA, Morris EP, Klug DR, Willison KR, 2009. A single amino acid residue is responsible for species-specific incompatibility between CCT and α-actin. FEBS Letters 583, 782–786. 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.01.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aspenstrom P, Engkvist H, Lindberg U, Karlsson R, 1992. Characterization of yeast-expressed beta-actins, site-specifically mutated at the tumor-related residue Gly245. Eur J Biochem 207, 315–320. 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1992.tb17052.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aspenstrom P, Karlsson R, 1991. Interference with myosin subfragment-1 binding by site-directed mutagenesis of actin. Eur J Biochem 200, 35–41. 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1991.tb21045.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai F, Caster HM, Rubenstein PA, Dawson JF, Kawai M, 2014. Using baculovirus/insect cell expressed recombinant actin to study the molecular pathogenesis of HCM caused by actin mutation A331P. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology 74, 64–75. 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2014.04.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balchin D, Miličić G, Strauss M, Hayer-Hartl M, Hartl FU, 2018. Pathway of Actin Folding Directed by the Eukaryotic Chaperonin TRiC. Cell 174, 1507–1521.e16. 10.1016/j.cell.2018.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balta E, Kramer J, Samstag Y, 2021. Redox Regulation of the Actin Cytoskeleton in Cell Migration and Adhesion: On the Way to a Spatiotemporal View. Front. Cell Dev. Biol 8, 618261. 10.3389/fcell.2020.618261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barger CJ, Zhang W, Sharma A, Chee L, James SR, Kufel CN, Miller A, Meza J, Drapkin R, Odunsi K, Klinkebiel D, Karpf AR, 2018. Expression of the POTE gene family in human ovarian cancer. Sci Rep 8, 17136. 10.1038/s41598-018-35567-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bera TK, Fleur AS, Lee Y, Kydd A, Hahn Y, Popescu NC, Zimonjic DB, Lee B, Pastan I, 2006. POTE Paralogs Are Induced and Differentially Expressed in Many Cancers. Cancer Research 66, 52–56. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergeron SE, Zhu M, Thiem SM, Friderici KH, Rubenstein PA, 2010. Ion-dependent polymerization differences between mammalian beta- and gamma-nonmuscle actin isoforms. J. Biol. Chem 285, 16087–16095. 10.1074/jbc.M110.110130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernheim-Groswasser A, Prost J, Sykes C, 2005. Mechanism of Actin-Based Motility: A Dynamic State Diagram. Biophysical Journal 89, 1411–1419. 10.1529/biophysj.104.055822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchoin L, Boujemaa-Paterski R, Sykes C, Plastino J, 2014. Actin Dynamics, Architecture, and Mechanics in Cell Motility. Physiological Reviews 94, 235–263. 10.1152/physrev.00018.2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bookwalter CS, Trybus KM, 2006. Functional Consequences of a Mutation in an Expressed Human α-Cardiac Actin at a Site Implicated in Familial Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. Journal of Biological Chemistry 281, 16777–16784. 10.1074/jbc.M512935200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunnell TM, Ervasti JM, 2011. Structural and Functional Properties of the Actin Gene Family. Crit Rev Eukar Gene Expr 21, 255–266. 10.1615/CritRevEukarGeneExpr.v21.i3.30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buzan J, Du J, Karpova T, Frieden C, 1999. Histidine-tagged wild-type yeast actin: Its properties and use in an approach for obtaining yeast actin mutants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 96, 2823–2827. 10.1073/pnas.96.6.2823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceron RH, Carman PJ, Rebowski G, Boczkowska M, Heuckeroth RO, Dominguez R, 2022. A solution to the long-standing problem of actin expression and purification. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 119, e2209150119. 10.1073/pnas.2209150119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen A, Arora PD, McCulloch CA, Wilde A, 2017. Cytokinesis requires localized β-actin filament production by an actin isoform specific nucleator. Nat Commun 8, 1530. 10.1038/s41467-017-01231-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen A, Ulloa Severino L, Panagiotou TC, Moraes TF, Yuen DA, Lavoie BD, Wilde A, 2021. Inhibition of polar actin assembly by astral microtubules is required for cytokinesis. Nat Commun 12, 2409. 10.1038/s41467-021-22677-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Kaw K, Lu H, Fagnant PM, Chattopadhyay A, Duan XY, Zhou Z, Ma S, Liu Z, Huang J, Kamm K, Stull JT, Kwartler CS, Trybus KM, Milewicz DM, 2021. Resistance of Acta2 mice to aortic disease is associated with defective release of mutant smooth muscle α-actin from the chaperonin-containing TCP1 folding complex. Journal of Biological Chemistry 297, 101228. 10.1016/j.jbc.2021.101228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin SM, Hatano T, Sivashanmugam L, Suchenko A, Kashina AS, Balasubramanian MK, Jansen S, 2022. N-terminal acetylation and arginylation of actin determines the architecture and assembly rate of linear and branched actin networks. Journal of Biological Chemistry 298, 102518. 10.1016/j.jbc.2022.102518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins JH, Elzinga M, 1975. The primary structure of actin from rabbit skeletal muscle. Completion and analysis of the amino acid sequence. J Biol Chem 250, 5915–5920. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook RK, Blake WT, Rubenstein PA, 1992. Removal of the amino-terminal acidic residues of yeast actin. Studies in vitro and in vivo. Journal of Biological Chemistry 267, 9430–9436. 10.1016/S0021-9258(19)50441-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa CF, Rommelaere H, Waterschoot D, Sethi KK, Nowak KJ, Laing NG, Ampe C, Machesky LM, 2004. Myopathy mutations in α-skeletal-muscle actin cause a range of molecular defects. Journal of Cell Science 117, 3367–3377. 10.1242/jcs.01172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai J, Zhang T, Guo J, Zhou Q, Gu Y, Zhang J, Hu L, Zong Y, Song J, Zhang S, Dai C, Gong F, Lu G, Zheng W, Lin G, 2021. Homozygous pathogenic variants in ACTL9 cause fertilization failure and male infertility in humans and mice. The American Journal of Human Genetics 108, 469–481. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2021.02.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalle-Donne I, Rossi R, Giustarini D, Gagliano N, Di Simplicio P, Colombo R, Milzani A, 2002. Methionine oxidation as a major cause of the functional impairment of oxidized actin. Free Radical Biology and Medicine 32, 927–937. 10.1016/S0891-5849(02)00799-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debold EP, Saber W, Cheema Y, Bookwalter CS, Trybus KM, Warshaw DM, VanBuren P, 2010. Human actin mutations associated with hypertrophic and dilated cardiomyopathies demonstrate distinct thin filament regulatory properties in vitro. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology 48, 286–292. 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.09.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drazic A, Aksnes H, Marie M, Boczkowska M, Varland S, Timmerman E, Foyn H, Glomnes N, Rebowski G, Impens F, Gevaert K, Dominguez R, Arnesen T, 2018. NAA80 is actin’s N-terminal acetyltransferase and regulates cytoskeleton assembly and cell motility. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 115, 4399–4404. 10.1073/pnas.1718336115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erba HP, Eddy R, Shows T, Kedes L, Gunning P, 1988. Structure, chromosome location, and expression of the human gamma-actin gene: differential evolution, location, and expression of the cytoskeletal beta- and gamma-actin genes. Mol. Cell. Biol 8, 1775–1789. 10.1128/MCB.8.4.1775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erba HP, Gunning P, Kedes L, 1986. Nucleotide sequence of the human γ cytoskeletal actin mRNA: anomalous evolution of vertebrate non-muscle actin genes. Nucl Acids Res 14, 5275–5294. 10.1093/nar/14.13.5275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrer P, Upadhyay S, Ikawa M, Clement TM, 2023. Testis-specific actin-like 7A (ACTL7A) is an indispensable protein for subacrosomal-associated F-actin formation, acrosomal anchoring, and male fertility. Molecular Human Reproduction 29, gaad005. 10.1093/molehr/gaad005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funk J, Merino F, Venkova L, Heydenreich L, Kierfeld J, Vargas P, Raunser S, Piel M, Bieling P, 2019. Profilin and formin constitute a pacemaker system for robust actin filament growth. eLife 8, e50963. 10.7554/eLife.50963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goris M, Magin RS, Foyn H, Myklebust LM, Varland S, Ree R, Drazic A, Bhambra P, Støve SI, Baumann M, Haug BE, Marmorstein R, Arnesen T, 2018. Structural determinants and cellular environment define processed actin as the sole substrate of the N-terminal acetyltransferase NAA80. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 115, 4405–4410. 10.1073/pnas.1719251115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haahr P, Galli RA, Van Den Hengel LG, Bleijerveld OB, Kazokaitė-Adomaitienė J, Song J-Y, Kroese LJ, Krimpenfort P, Baltissen MP, Vermeulen M, Ottenheijm CAC, Brummelkamp TR, 2022. Actin maturation requires the ACTMAP/C19orf54 protease. Science 377, 1533–1537. 10.1126/science.abq5082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haarer BK, Pimm ML, De Jong EP, Amberg DC, Henty-Ridilla JL, 2023. Purification of human β- and γ-actin from budding yeast. Journal of Cell Science 136, jcs260540. 10.1242/jcs.260540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn Y, Bera TK, Pastan IH, Lee B, 2006. Duplication and extensive remodeling shaped POTE family genes encoding proteins containing ankyrin repeat and coiled coil domains. Gene 366, 238–245. 10.1016/j.gene.2005.07.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen SD, Zuchero JB, Mullins RD, 2013. Cytoplasmic Actin: Purification and Single Molecule Assembly Assays, in: Coutts AS (Ed.), Adhesion Protein Protocols, Methods in Molecular Biology. Humana Press, Totowa, NJ, pp. 145–170. 10.1007/978-1-62703-538-5_9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatano T, Alioto S, Roscioli E, Palani S, Clarke ST, Kamnev A, Hernandez-Fernaud JR, Sivashanmugam L, Chapa-Y-Lazo B, Jones AME, Robinson RC, Sampath K, Mishima M, McAinsh AD, Goode BL, Balasubramanian MK, 2018. Rapid production of pure recombinant actin isoforms in Pichia pastoris. Journal of Cell Science jcs.213827. 10.1242/jcs.213827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatano T, Sivashanmugam L, Suchenko A, Hussain H, Balasubramanian MK, 2020. Pick-ya actin: a method to purify actin isoforms with bespoke key post-translational modifications. Journal of Cell Science jcs.241406. 10.1242/jcs.241406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heier JA, Dickinson DJ, Kwiatkowski AV, 2017. Measuring Protein Binding to F-actin by Co-sedimentation. JoVE 55613. 10.3791/55613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornbeck PV, Zhang B, Murray B, Kornhauser JM, Latham V, Skrzypek E, 2015. PhosphoSitePlus, 2014: mutations, PTMs and recalibrations. Nucleic Acids Research 43, D512–D520. 10.1093/nar/gku1267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson GR, Rosenbusch JP, 1976. ATP binding to a protease-resistant core of actin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 73, 2742–2746. 10.1073/pnas.73.8.2742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeruzalska E, Mazur AJ, 2023. The Role of non-muscle actin paralogs in cell cycle progression and proliferation. European Journal of Cell Biology 102, 151315. 10.1016/j.ejcb.2023.151315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalhor HR, Niewmierzycka A, Faull KF, Yao X, Grade S, Clarke S, Rubenstein PA, 1999. A Highly Conserved 3-Methylhistidine Modification Is Absent in Yeast Actin. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics 370, 105–111. 10.1006/abbi.1999.1370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karakozova M, Kozak M, Wong CCL, Bailey AO, Yates JR, Mogilner A, Zebroski H, Kashina A, 2006. Arginylation of β-Actin Regulates Actin Cytoskeleton and Cell Motility. Science 313, 192–196. 10.1126/science.1129344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson R, 1988. Expression of chicken beta-actin in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Gene 68, 249–257. 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90027-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson R, Aspenström P, Byström AS, 1991. A Chicken β-Actin Gene Can Complement a Disruption of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae ACT1 Gene. Molecular and Cellular Biology 11, 213–217. 10.1128/mcb.11.1.213-217.1991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwiatkowski S, Seliga AK, Vertommen D, Terreri M, Ishikawa T, Grabowska I, Tiebe M, Teleman AA, Jagielski AK, Veiga-da-Cunha M, Drozak J, 2018. SETD3 protein is the actin-specific histidine N-methyltransferase. eLife 7, e37921. 10.7554/eLife.37921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landon F, Hue C, Thome F, Oriol C, Olomucki A, 1977. Human Platelet Actin. Evidence of beta and gamma Forms and Similarity of Properties with Sarcomeric Actin. Eur J Biochem 81, 571–577. 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1977.tb11984.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lassing I, Schmitzberger F, Björnstedt M, Holmgren A, Nordlund P, Schutt CE, Lindberg U, 2007. Molecular and Structural Basis for Redox Regulation of β-Actin. Journal of Molecular Biology 370, 331–348. 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.04.056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarides E, Lindberg U, 1974. Actin Is the Naturally Occurring Inhibitor of Deoxyribonuclease I. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 71, 4742–4746. 10.1073/pnas.71.12.4742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y, Ise T, Ha D, Saint Fleur A, Hahn Y, Liu X-F, Nagata S, Lee B, Bera TK, Pastan I, 2006. Evolution and expression of chimeric POTE–actin genes in the human genome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 103, 17885–17890. 10.1073/pnas.0608344103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, Henein M, Anillo M, Dawson JF, 2018. Cardiac actin changes in the actomyosin interface have different effects on myosin duty ratio. Biochem. Cell Biol 96, 26–31. 10.1139/bcb-2017-0136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu H, Fagnant PM, Bookwalter CS, Joel P, Trybus KM, 2015. Vascular disease-causing mutation R258C in ACTA2 disrupts actin dynamics and interaction with myosin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 112. 10.1073/pnas.1507587112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malek N, Michrowska A, Mazurkiewicz E, Mrówczyńska E, Mackiewicz P, Mazur AJ, 2021. The origin of the expressed retrotransposed gene ACTBL2 and its influence on human melanoma cells’ motility and focal adhesion formation. Sci Rep 11, 3329. 10.1038/s41598-021-82074-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Benito J, 2002. Structure of eukaryotic prefoldin and of its complexes with unfolded actin and the cytosolic chaperonin CCT. The EMBO Journal 21, 6377–6386. 10.1093/emboj/cdf640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mavrakis M, Juanes MA, 2023. The compass to follow: Focal adhesion turnover. Current Opinion in Cell Biology 80, 102152. 10.1016/j.ceb.2023.102152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazur AJ, Radaszkiewicz T, Makowiecka A, Malicka-Błaszkiewicz M, Mannherz HG, Nowak D, 2016. Gelsolin interacts with LamR, hnRNP U, nestin, Arp3 and β-tubulin in human melanoma cells as revealed by immunoprecipitation and mass spectrometry. European Journal of Cell Biology 95, 26–41. 10.1016/j.ejcb.2015.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miwa T, Manabe Y, Kurokawa K, Kamada S, Kanda N, Bruns G, Ueyama H, Kakunaga T, 1991. Structure, chromosome location, and expression of the human smooth muscle (enteric type) gamma-actin gene: evolution of six human actin genes. Mol. Cell. Biol 11, 3296–3306. 10.1128/MCB.11.6.3296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller M, Diensthuber RP, Chizhov I, Claus P, Heissler SM, Preller M, Taft MH, Manstein DJ, 2013. Distinct Functional Interactions between Actin Isoforms and Nonsarcomeric Myosins. PLoS ONE 8, e70636. 10.1371/journal.pone.0070636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nirschl JJ, Ghiretti AE, Holzbaur ELF, 2017. The impact of cytoskeletal organization on the local regulation of neuronal transport. Nat Rev Neurosci 18, 585–597. 10.1038/nrn.2017.100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noguchi TQP, Kanzaki N, Ueno H, Hirose K, Uyeda TQP, 2007. A Novel System for Expressing Toxic Actin Mutants in Dictyostelium and Purification and Characterization of a Dominant Lethal Yeast Actin Mutant. Journal of Biological Chemistry 282, 27721–27727. 10.1074/jbc.M703165200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyman T, Schuler H, Korenbaum E, Schutt CE, Karlsson R, Lindberg U, 2002. The role of MeH73 in actin polymerization and ATP hydrolysis 1 1Edited by Huber R. Journal of Molecular Biology 317, 577–589. 10.1006/jmbi.2002.5436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohki T, Mikhailenko SV, Arai T, Ishii S, Ishiwata S, 2012. Improvement of the yields of recombinant actin and myosin V–HMM in the insect cell/baculovirus system by the addition of nutrients to the high-density cell culture. J Muscle Res Cell Motil 33, 351–358. 10.1007/s10974-012-9323-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohki T, Ohno C, Oyama K, Mikhailenko SV, Ishiwata S, 2009. Purification of cytoplasmic actin by affinity chromatography using the C-terminal half of gelsolin. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 383, 146–150. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.03.144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavlyk I, Leu NA, Vedula P, Kurosaka S, Kashina A, 2018. Rapid and dynamic arginylation of the leading edge β-actin is required for cell migration. Traffic 19, 263–272. 10.1111/tra.12551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinder J, Gratzer W, 1983. Structural and dynamic states of actin in the erythrocyte. Journal of Cell Biology 96, 768–775. 10.1083/jcb.96.3.768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rebowski G, Boczkowska M, Drazic A, Ree R, Goris M, Arnesen T, Dominguez R, 2020. Mechanism of actin N-terminal acetylation. Sci. Adv 6, eaay8793. 10.1126/sciadv.aay8793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ree R, Kind L, Kaziales A, Varland S, Dai M, Richter K, Drazic A, Arnesen T, 2020. PFN2 and NAA80 cooperate to efficiently acetylate the N-terminus of actin. Journal of Biological Chemistry 295, 16713–16731. 10.1074/jbc.RA120.015468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg S, Stracher A, Lucas RC, 1981. Isolation and characterization of actin and actin-binding protein from human platelets. Journal of Cell Biology 91, 201–211. 10.1083/jcb.91.1.201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouyère C, Serrano T, Frémont S, Echard A, 2022. Oxidation and reduction of actin: Origin, impact in vitro and functional consequences in vivo. European Journal of Cell Biology 101, 151249. 10.1016/j.ejcb.2022.151249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saborio JL, Segura M, Flores M, Garcia R, Palmer E, 1979. Differential expression of gizzard actin genes during chick embryogenesis. Journal of Biological Chemistry 254, 11119–11125. 10.1016/S0021-9258(19)86638-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saha S, Mundia MM, Zhang F, Demers RW, Korobova F, Svitkina T, Perieteanu AA, Dawson JF, Kashina A, 2010. Arginylation Regulates Intracellular Actin Polymer Level by Modulating Actin Properties and Binding of Capping and Severing Proteins. MBoC 21, 1350–1361. 10.1091/mbc.e09-09-0829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer DA, Jennings PB, Cooper JA, 1998. Rapid and efficient purification of actin from nonmuscle sources. Cell Motil. Cytoskeleton 39, 166–171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segura M, Lindberg U, 1984. Separation of non-muscle isoactins in the free form or as profilactin complexes. J Biol Chem 259, 3949–3954. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shekhar S, 2017. Microfluidics-Assisted TIRF Imaging to Study Single Actin Filament Dynamics. Current Protocols in Cell Biology 77. 10.1002/cpcb.31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stemp MJ, Guha S, Hartl FU, Barral JM, 2005. Efficient production of native actin upon translation in a bacterial lysate supplemented with the eukaryotic chaperonin TRiC. Biological Chemistry 386, 753–757. 10.1515/BC.2005.088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutoh K, Ando M, Sutoh K, Toyoshima YY, 1991. Site-directed mutations of Dictyostelium actin: disruption of a negative charge cluster at the N terminus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 88, 7711–7714. 10.1073/pnas.88.17.7711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sykes C, Plastino J, 2022. Reconstitution of Actin-Based Motility with Commercially Available Proteins. JoVE 64261. 10.3791/64261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teng GZ, Shaikh Z, Liu H, Dawson JF, 2019. M-class hypertrophic cardiomyopathy cardiac actin mutations increase calcium sensitivity of regulated thin filaments. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 519, 148–152. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2019.08.151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terman JR, Kashina A, 2013. Post-translational modification and regulation of actin. Current Opinion in Cell Biology 25, 30–38. 10.1016/j.ceb.2012.10.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Topalov NE, Mayr D, Scherer C, Chelariu-Raicu A, Beyer S, Hester A, Kraus F, Zheng M, Kaltofen T, Kolben T, Burges A, Mahner S, Trillsch F, Jeschke U, Czogalla B, 2021. Actin Beta-Like 2 as a New Mediator of Proliferation and Migration in Epithelial Ovarian Cancer. Front. Oncol 11, 713026. 10.3389/fonc.2021.713026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Damme P, Evjenth R, Foyn H, Demeyer K, De Bock P-J, Lillehaug JR, Vandekerckhove J, Arnesen T, Gevaert K, 2011. Proteome-derived Peptide Libraries Allow Detailed Analysis of the Substrate Specificities of Nα-acetyltransferases and Point to hNaa10p as the Post-translational Actin Nα-acetyltransferase. Molecular & Cellular Proteomics 10, M110.004580. 10.1074/mcp.M110.004580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Damme P, Lasa M, Polevoda B, Gazquez C, Elosegui-Artola A, Kim DS, De Juan-Pardo E, Demeyer K, Hole K, Larrea E, Timmerman E, Prieto J, Arnesen T, Sherman F, Gevaert K, Aldabe R, 2012. N-terminal acetylome analyses and functional insights of the N-terminal acetyltransferase NatB. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 109, 12449–12454. 10.1073/pnas.1210303109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandekerckhove J, Weber K, 1978. At least six different actins are expressed in a higher mammal: An analysis based on the amino acid sequence of the amino-terminal tryptic peptide. Journal of Molecular Biology 126, 783–802. 10.1016/0022-2836(78)90020-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vang S, Corydon TJ, Børglum AD, Scott MD, Frydman J, Mogensen J, Gregersen N, Bross P, 2005. Actin mutations in hypertrophic and dilated cardiomyopathy cause inefficient protein folding and perturbed filament formation: Misfolding of actin variants in cardiomyopathies. FEBS Journal 272, 2037–2049. 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.04630.X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varland S, Vandekerckhove J, Drazic A, 2019. Actin Post-translational Modifications: The Cinderella of Cytoskeletal Control. Trends in Biochemical Sciences 44, 502–516. 10.1016/j.tibs.2018.11.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vedula P, Kashina A, 2018. The makings of the ‘actin code’: regulation of actin’s biological function at the amino acid and nucleotide level. Journal of Cell Science 131, jcs215509. 10.1242/jcs.215509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson AW, Diep J, Dai S, Liu S, Ooi YS, Song D, Li T-M, Horton JR, Zhang X, Liu C, Trivedi DV, Ruppel KM, Vilches-Moure JG, Casey KM, Mak J, Cowan T, Elias JE, Nagamine CM, Spudich JA, Cheng X, Carette JE, Gozani O, 2019. SETD3 is an actin histidine methyltransferase that prevents primary dystocia. Nature 565, 372–376. 10.1038/S41586-018-0821-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wioland H, Ghasemi F, Chikireddy J, Romet-Lemonne G, Jégou A, 2022. Using Microfluidics and Fluorescence Microscopy to Study the Assembly Dynamics of Single Actin Filaments and Bundles. JoVE 63891. 10.3791/63891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xin A, Qu R, Chen G, Zhang L, Chen J, Tao C, Fu J, Tang J, Ru Y, Chen Y, Peng X, Shi H, Zhang F, Sun X, 2020. Disruption in ACTL7A causes acrosomal ultrastructural defects in human and mouse sperm as a novel male factor inducing early embryonic arrest. Sci. Adv 0036, eaaz4796. 10.1126/sciadv.aaz4796 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F, Saha S, Shabalina SA, Kashina A, 2010. Differential Arginylati on of Actin Isoforms Is Regulated by Coding Sequence–Dependent Degradation. Science 329, 1534–1537. 10.1126/science.1191701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X-Z, Wei L-L, Zhang X-H, Jin H-J, Chen S-R, 2022. Loss of perinuclear theca ACTRT1 causes acrosome detachment and severe male subfertility in mice. Development 149, dev200489. 10.1242/dev.200489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]