Abstract

Exacerbated inflammatory responses can be detrimental and pose fatal threats to the host, as exemplified by the global impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, resulting in millions of fatalities. Developing novel drugs to combat the damaging effects of inflammation is essential for both preventive measures and therapeutic interventions. Accumulating evidence suggests that Angiotensin Converting Enzyme 2 (ACE2) possesses the ability to optimize inflammatory responses. However, the clinical applicability of this potential is limited due to the lack of dependable ACE2 activators. In this study, we conducted a screening of an FDA-approved drug library and successfully identified a novel ACE2 activator, termed H4. The activator demonstrated the capability to mitigate lung inflammation caused by bacterial lung infections, effectively modulating neutrophil infiltration. Importantly, to improve the clinical applicability of the poorly water-soluble H4, we developed a prodrug variant with significantly enhanced water solubility while maintaining a similar level of efficacy as H4 in attenuating inflammatory responses in the lungs of mice exposed to bacterial infections. This finding highlights the potential of formulated H4 as a promising candidate for the treatment and prevention of inflammatory diseases, including lung-related conditions.

1. Introduction

The Renin-Angiotensin System (RAS) serves a critical role in regulating various physiological functions within tissues and organs, such as the cardiovascular system and lungs. Its responsibilities encompass maintaining blood pressure, managing electrolyte balance, and orchestrating host defense mechanisms [1]. Under normal conditions, the RAS is constitutively active and regulated by an array of physiological and pathophysiological agents to maintain homeostasis [2–8]. In the context of viral and bacterial infections, the RAS can experience heightened activation within the lungs [9–16]. However, excessive activation of the RAS, often linked to the progression of various pathological conditions like inflammatory lung diseases (ILDs), can be detrimental, leading to prolonged and intensified inflammatory responses. Thus, curtailing the excessive activation of the RAS stands as a potential therapeutic approach for multiple diseases, including ILDs. Notably, ILDs caused by exaggerated inflammatory responses of the host to infectious and/or non-infectious stimuli can inflict more adverse effects on the lungs than the inciting insults, which is evidenced by the COVID-19 pandemic in recent years [17–20].

Angiotensin Converting Enzyme 2 (ACE2) functions as a carboxypeptidase and plays a pivotal role within the ACE2/Ang-(1–7)/Mas receptor compensatory axis of the RAS [21–27]. Since its initial discovery, numerous research investigations have indicated the enzyme’s significant involvement in hypertension and other cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) [28–31]. ACE2 regulates the inflammatory response in the lungs by blocking Ang-II/AT1R signaling and activating Ang-(1–7)/Mas1 axis, making ACE2 an ideal therapeutic target in treating and preventing ILDs. While ACE2 can effectively degrade Ang-II and activate an anti-inflammatory pathway, it affects blood pressure only in a hypertensive state and has little to no effect on regulating blood pressure in normal conditions, nor does it cause hypotension [30,32].

While RAS overactivity is a common feature of inflammatory lung diseases, the existing range of therapeutic interventions shows significant variability and has yet to fully capitalize on the compensatory potential of the RAS. This shortfall may be attributed to the absence of potent ACE2 activators, thereby impeding the clinical utilization of ACE2 as a means to effectively address and alleviate inflammatory lung diseases along with their associated complications. Two distinct strategies have emerged to augment ACE2 activity [27,33]. The first involves administering recombinant active human ACE2 protein, which is currently undergoing clinical trials for treating acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). Various clinical trials are exploring the use of ACE2 as a decoy to intercept SARS-CoV2 while retaining its enzymatic activity, with several trials progressing into phases I and II [27,33]. There also have been studies of using hACE2 to treat SARS-CoV2 while silencing its enzymatic activities [34]. The other approach focuses on the discovery of ACE2 activators to upregulate the enzymatic activity of ACE2. Two compounds, DIZE (diminazene aceturate) and XNT (xanthenone), have been reported to be effective and beneficial in various animal disease models [35,36]. However, all these agents have significant shortcomings. Countering the effects of recombinant hACE2, the short-lived in vivo enzymatic activity limits this moiety’s clinical usage, and endogenous inhibitory antibodies have been reported [37–44]. As for the small molecule ACE2 activators, DIZE and XNT are well known for their high toxicity [35,36,45]. Furthermore, debates have arisen regarding the perceived advantages of “ACE2 activators,” as similar effects were observed in their absence [45]. Therefore, finding a new class of ACE2 activator with high efficacy, specificity, and low toxicity remains a compelling quest to fully exploit the therapeutic potential of ACE2 in ILDs.

In this study, we identified a novel ACE2 enzymatic enhancer termed H4 by screening an FDA-approved drug library. Our findings demonstrate that H4 augments ACE2 activity exclusively in wild-type mice, with no effect observed in ACE2-deficient mice, establishing its ACE2-specific activation property. Furthermore, we have developed an H4 prodrug that enhances H4’s solubility while preserving its ability to activate ACE2. This prodrug formulation paves the way for the future development of H4 as a potential therapeutic agent for ILDs and other inflammatory diseases.

2. Methods

2.1. Cell culture

Calu-3 human airway epithelial cells (HTB-55™) and NIH/3T3 mouse fibroblast cells (CRL-1658) were obtained from ATCC, and both cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum, 40μg per mL insulin (Gibco), 100units per mL penicillin, and 100μg per mL streptomycin. All experiments were performed using cells no later than passage 10.

2.2. Screening FDA-approved drug library for discovery of ACE2 activator

Calu-3 cells were treated serially with individual compounds contained within the Johns Hopkins Drug Library (JHDL), which includes a series of FDA-approved drugs [46] (kindly provided by Dr. Jun O. Liu, Johns Hopkins University) at 10μM for 18h, and the ACE2 activity in cell culture medium was determined by measuring the fluorescence intensity of ACE2 substrate Mca-YVADAPK(Dnp)-OH (Catalog no. ES007; R&D Systems) [15]. In brief, samples were diluted in assay buffer (50 mM MES, 300 mM NaCl, 10 nM ZnCl2, and 0.01% Brij-35 [pH 6.5]) and incubated with ACE2 substrate, with or without the ACE2 inhibitor MLN4760 (1 nM, catalog no. 62337; AnaSpec), at 37 °C for 45 min. The fluorescence intensity was determined using a multiplate fluorescence reader at excitation 330 nm and emission 405 nm. Hits that enhance ACE2 activity in the culture medium >4 folds than that of the control vehicle are selected to determine the dose and time-dependent responses further. Our lead compound from these studies is herein labeled “H4”.

2.3. Determining the dose and time responses of H4 on ACE2 activity

The H4 stock solution was prepared by resolving H4 into DMSO at a 5 mg/ml concentration, which was subsequently diluted with saline to the specified concentration for each study. Calu-3 cells were treated with variable doses of H4 (0–500 μg/ml) at 37 °C. After 18 h of incubation, the culture medium was collected for ACE2 activity measurement. To evaluate the kinetics of H4 on ACE2 activity, Calu-3 cells were stimulated with 25 μg/mL H4 and evaluated at various times after stimulation. The cell culture medium was collected for the ACE2 activity assay, and the cells were collected for quantitative real-time PCR assay.

2.4. Flow cytometry for neutrophils

The cells from mouse BAL were washed in 10 ml 1% BSA in PBS (FACS buffer) and then incubated with anti-CD16/CD32 (BD Biosciences) to block Fc receptor binding (20 min at 4 °C). The cells were stained for surface molecules using fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies in ice-cold FACS buffer, and the dead cells were stained using Fixable Viability Violet Dye (Thermo Fisher) in PBS. After washing, the samples were analyzed on a Northern light flow cytometer, with the SpectrFlow software, for CD45+CD11b+Ly6G+ cells. The data was analyzed using the Flowjo software. The fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies used in this study include rat anti-mouse CD45 PerCP-Cyanine5.5, rat anti-mouse CD11b FITC, and rat anti-mouse Ly6G PerCP-eFluor 710 (BioLegend).

2.5. Materials and chemicals for H4 prodrug synthesis

The 9-Fluorenylmethoxycarnonyl (Fmoc) protected amino acids used in this study (Fmoc-Val-OH and Fmoc-Glu(OtBu)-OH) and o-benzotriazole-N,N,N′,N′-tetramethyl-uronium-hexafluorophosphate (HBTU) were obtained from Advanced Automated Peptide Protein Technologies (AAPPTEC, Louisville, KY, USA). Rink amide 4-methylbenzhydrylamine (MBHA) resin LL (100–200 mesh, 0.65 mmol/g) was sourced from Novabiochem (San Diego, CA, USA). H4 (>98% purity) was purchased from AK Scientific, Inc. (Union City, CA, USA). 4-Dimethylaminopyridine (DMAP, >99.0% purity) was obtained from TCI America (Portland, OR, USA). All other solvents and chemical reagents used in this study were obtained from Fisher Scientific (Fairfield, NJ, USA) without further purification, unless otherwise stated.

2.6. Synthesis of H4-succinic acid conjugate

The synthetic route of the H4 prodrug is outlined in Scheme S1. Protection of the 16′ and 17′ hydroxyl groups on H4 (2.0 g, 6.94 mmol) was initiated with 2,2-dimethoxypropane (7.24 g, 69.5 mmol) and a catalytic amount of p-toluenesulfonic acid (360 mg, 1.89 mmol) in anhydrous N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF, 25 mL). After stirring overnight at room temperature, the solution was concentrated in vacuo to give protected-H4 as a white solid (1.67 g, 73.4%). The formation of the crude protected-H4 product was confirmed by the absence of H4’s 16′ and 17′ hydroxyl groups with 1H NMR (Figs. S1–S2), using a Bruker Avance 400 MHz FT-NMR spectrometer and MestReNova NMR software (School of Chemistry, University of Bristol, Bristol, UK). Additionally, an LDQ Deca ion-trap mass spectrometer (Thermo-Finnigan, San Jose, CA) was used to determine ESI-MS mass spectrometric data (Fig. S3).

The protected-H4 product (1.55 g, 4.72 mmol) reacted with succinic anhydride (945 mg, 9.44 mmol), N,N-diisopropylethylamine (DIEA, 924 μL, 9.44 mmol), and a catalytic amount of 4-dimethylaminopyridine (DMAP, 30 mg, 0.25 mmol) in dichloromethane (DCM, 30 mL) at 0 °C for 30 min. After reacting at room temperature for 24 h, extractions were performed with 1 M hydrochloric acid (3 times), water (3 times), and brine (3 times). The organic layer was concentrated in vacou, forming a light brown solid (935 mg, 51.0%). Fig. S4 contains the 1H NMR for synthesized crude H4-succinic acid product, and Fig. S5 contains the ESI spectra.

2.7. Synthesis of peptide amphiphile

Fmoc-Val-Val-Glu(OtBu)-Glu(OtBu)-Rink was synthesized using standard Fmoc solid-phase peptide synthesis (SPPS), using a Rink amide MBHA resin support (0.5 mmol). All Fmoc deprotection steps were performed with 20% v/v 4-methylpiperidine in DMF for 15 min, repeated once. A ninhydrin test from Anaspec Inc. (Fremont, Ca, USA) was used to determine the presence of a free amine group after each deprotection step. Subsequent amino acid couplings were performed with a 2.0: 2.0: 5.0 M ratio of N-Fmoc protected amino acid, HBTU, and N, N-diisopropylethylamine (DIEA) to the resin dissolved in a DMF solvent, for two hours. Excess reagent was removed by washing 3 times with DMF and 3 times with DCM between each amino acid coupling and Fmoc-deprotection steps.

2.8. Conjugating H4-succinic acid to peptide amphiphile

The crude H4-succinic acid conjugate (1.0 mmol) was coupled to the Fmoc-deprotected Val-Val-Glu(OtBu)-Glu(OtBu)-Rink peptide using HBTU and DIEA (2.0 mmol and 10.0 mmol respectively) in a DMF solvent, for 24 h at room temperature. Trifluoroacetic acid, water, and trisopropylsilane (95.2: 2.5: 5.0 (v/v/v)) was used to cleave the resin from the peptide derivative for 2.5 h with agitation. Excess cleavage solution was removed through evaporation, followed by three precipitation steps with liquid nitrogen-cooled diethyl ether. The precipitate was centrifuged at 5000 rpm for 10 min to obtain the crude H4-Succinic Acid-Val-Val-Glu-Glu-NH2 (“H4 prodrug”) product.

2.9. Purification and identification of H4 prodrug

Purification was performed with a Varian ProStar model 325 HPLC (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA), a Varian PLRP-S column (100 Å, 10 μm, 150 × 25 mm), and Thermo Xcaliber software. A UV detector at 220 nm monitored peptide absorbance. The crude H4-prodrug was purified at 25 °C using a water/acetonitrile gradient containing 0.1 vol% NH4OH, with a flow rate of 25 mL/min. To determine the purity of the eluted solution, an Agilent Zorbax-C18 column (100 Å, 10 μm, 150 × 25 mm), 0.1% v/v NH3OH-containing 10–90% water: acetonitrile gradient, and flow rate of 1 mL/min was used. The primary elution peak was at 8.77 min (Fig. S6a).

Matrix-assisted laser desorption-ionization (MALDI-ToF) spectroscopy using a BrukerAutoflex III MALDI-ToF instrument (Billerica, MA) determined the mass spectrometric characerization data for the H4 prodrug. The MALDI-ToF sample was prepared with 2 μL sinapinic acid matrix (10 mg/mL in 0.05% TFA in H2O/MeCn (1:1), Sigma-Aldrich, PA) was deposited and dried onto the MALDI plate, followed by a mixture of 2 μL of the aqueous conjugate solution with 2 μL of the sinapinic acid matrix. The dried sample was irradiated with a 355 nm UV laser and analyzed in reflectron mode to characterize the prodrug-peptide molecular weight (Fig. S6b). The purified product was lyophilized with a FreeZone freeze dryer (Labconco, Kansas City, MO) and stored in a − 30 °C freezer.

2.10. H4 prodrug self-assembly

The molecular self-assembly of purified H4 prodrug was directed by dissolving the aliquoted powder sample with purified water to a final concentration of 5 mM. The samples were tuned to pH 7.2 with 0.1 M HCl or 0.1 M NaOH, heated to 80 °C for 30 min, and cooled to room temperature. All solutions were aged at least 24 h at room temperature before further characterization measurements.

2.11. Cell cytotoxicity study

NIH/3T3 mouse fibroblast cells (CRL-1658, ATCC) were seeded into 96-well plates at a density of 5000 cells/well for 24 h. 1 mM self-assembled H4 prodrug was UV-sterilized for 1 h before being diluted with culture medium to have a final well concentration between 0.1 nM to 10 μM. After 48 h of incubating the cells with variable H4 prodrug concentrations, the culture medium was replaced with 20 μL of 0.45 mg/mL MTT solution (In Vitro Toxicology Assay Kit, MTT Assay; Cat No. TOX1, Sigma Aldrich) and incubated at 37 °C for 4 h. The supernatant was carefully removed, and 150 μL sterile dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO; Millipore Sigma, Oakville, ON, Canada) was added to dissolve the formazan crystals. A SpectraMax M5 plate reader (Molecular Devices, CA, USA) measured the absorbance at 570 nm. For the in vivo cytotoxicity study, wild-type C57/Bl6 mice were exposed to 30 μl of a 2.5 mg/ml solution containing either the prodrug or saline via nasal inhalation for 48 h. Lung tissues were collected and either stored in frozen for subsequent ELISA and qRT-PCR assays or fixed in PFA for histological analysis and immunofluorescent detection.

2.12. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM)

TEM samples were prepared by adding 6 μL of 1 mM self-assembled H4 prodrug solution on a carbon-coated copper grid (Electron Microscopy Services, Hatfield, PA) for 1 min, and carefully removing excess solution with filter paper. Then, 6 μL of 2 wt% aqueous uranyl acetate was used to stain the samples for 1 min, and dried with filter paper. The sample grid was thoroughly dried at room temperature prior to imaging on a FEI Tecnai 12 TWIN Transmission Electron Microscope with an acceleration voltage of 100 kV, and images were obtained with a SIS Megaview III wide-angle CCD camera.

2.13. Chelation of Zn+

The human recombinant ACE2 was treated with or without 25 μg/mL H4 at 37 °C, and the free Zn in the reaction was depleted by using 25 mM Zn chelator diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid (DTPA) [47]. The ACE2 activity was determined as described previously.

2.14. Statistical analysis

Where indicated, data were analyzed for statistical significance by two-tailed Student t-test or ANOVA (ordinary one-way ANOVA multiple comparisons) using Prism software (GraphPad). Statistical significance was determined as having a value <0.05, and data are represented as mean ± SEM as indicated. All experiments were repeated twice, with at least three mice per group for each assessment.

Additional methods can be found in the supporting file

3. Results

3.1. Identification of a novel ACE2 activator H4

We have previously reported that ACE2 activity is a critical component of host defense mechanisms through modulation of the innate immune response to bacterial lung infections by regulating neutrophil influx [15]. Thus, we screened a clinical compound library containing FDA-approved drugs [46] for ACE2 activators that could be used to prevent or treat P. aeruginosa infection-induced bacterial pneumonia. The preliminary screening consisted of using 10 mM of each compound in the library to stimulate cultured Calu-3 cells and assessing the ACE2 activity in the cell culture medium. The screening results revealed 6 existing drugs that can cause more than a 4-fold increase in ACE2 activity compared to the control reagent. One lead compound, depicted in Fig. 1A, bears a molecular weight of 288 Da and possesses the chemical formula C18H24O3, designated as “H4” in our study. Subsequently, we conducted a sequence of validation assays utilizing cultured Calu-3 cells as a model system. In the initial series of experiments, our aim was to determine the dose-response relationship of ACE2 activity enhancement by H4. As demonstrated in Fig. 1B, H4 notably augments ACE2 activity in a concentration range of 5–50 μg/mL. Moreover, the elicited ACE2 activity reaches its saturation point between 50 and 250 μg/mL, implying a dosage-dependent elevation of ACE2 activity mediated by H4. It is important to note that increasing the H4 concentration beyond this range does not lead to a further enhancement of ACE2 activity. This reduced effect can likely be attributed to H4’s solubility challenges or the potential toxic effects from the used organic solvent, DMSO, especially when present at a lower dilution ratio with saline. In a subsequent series of tests, we measured ACE2 activity in the culture medium at various time points following H4 stimulation using the mid-most effective dose of 25 μg/mL. Notably, a pronounced peak induction of ACE2 activity was observed at the 12-h post-stimulation time point (Fig. 1C), indicating a time dependent induction of ACE2 activity by H4.

Fig. 1.

Identification of ACE2 activator H4 and its ability to boost ACE2 activity in lung epithelial cells. (A) ACE2 activity in the conditional medium of cultured Calu-3 cells treated with different drugs. The lead drug is a 288Da molecule with the formula C18H24O3, herein named “H4” with its chemical structure illustrated to the right. (B) A dose-response curve of H4 for ACE2 activity in Calu-3 cells. (C) The ACE2 activity in the conditional medium of cultured Calu-3 cells treated with 25 μg/mL H4 and harvested at different time points. ****p < 0.0001, pvalues obtained either from two-sided t-tests. Each dot in the graphs represents data from an individual well of Calu-3 cells.

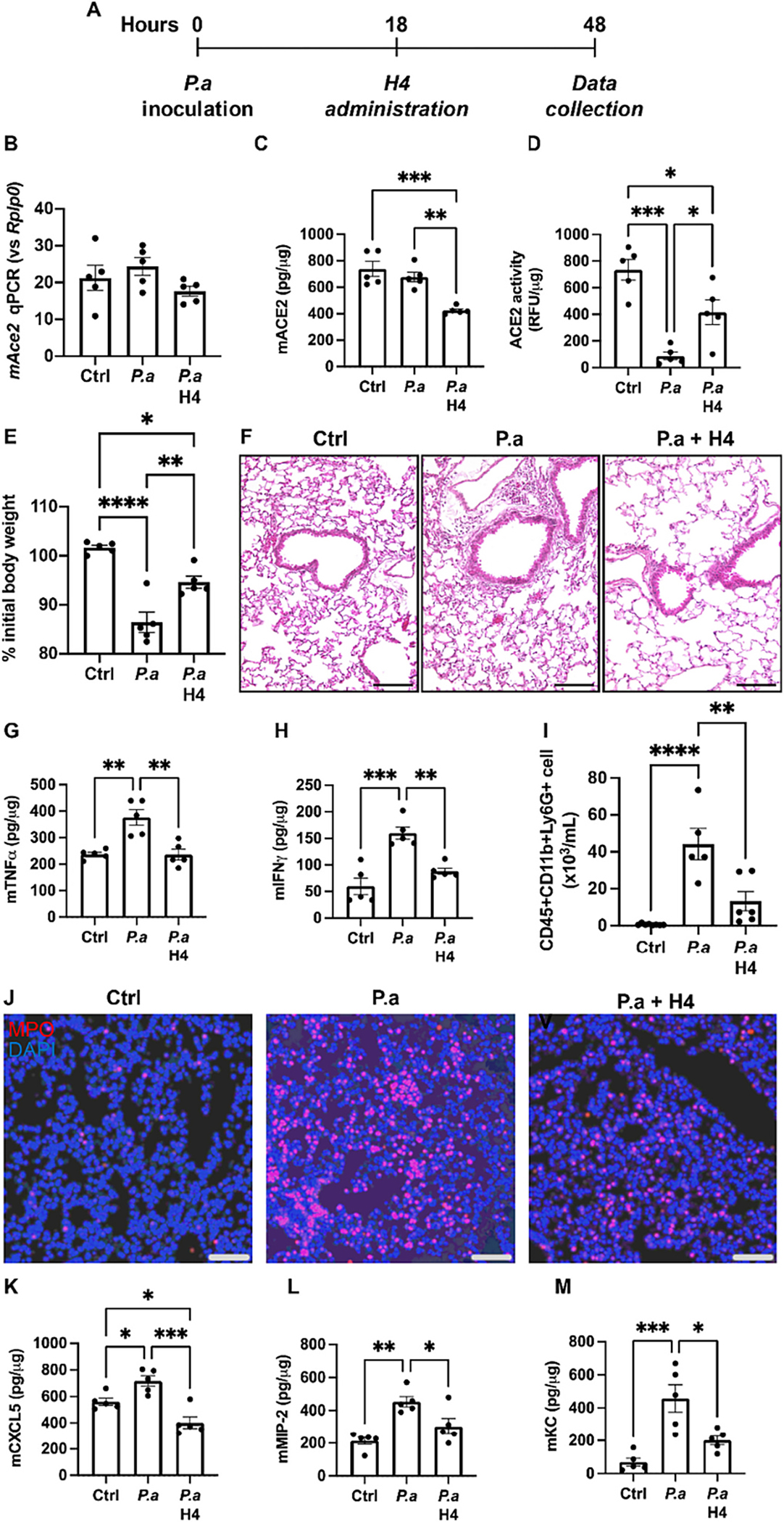

3.2. H4 reduces lung injury and neutrophil infiltration in a bacterial pneumonia mouse model

Having established the augmentation of ACE2 activity by H4 within an in vitro model, our focus shifted to investigating whether the in vivo administration of H4 could similarly activate ACE2 activity. To address this, we employed a well-established mouse model involving the intratracheal instillation of P. aeruginosa through tracheal intubation [15]. To be consistent with previous findings where the advantageous effects of bolstering ACE2 activity were observed only after bacterial inoculation and the initial proinflammatory cell infiltration had commenced [15], we administered H4 18 h after bacterial inoculation and collected samples 30 h following H4 administration (Fig. 2A). As illustrated in Figs. 2B–F, the introduction of P. aeruginosa bacteria to the lungs of mice resulted in bacterial pneumonia, as demonstrated from diminished ACE2 activity (Fig. 2D), substantial weight loss (Fig. 2E), exacerbated histopathological alterations (Fig. 2F), and heightened expression of proinflammatory cytokines TNFα (Fig. 2G) and IFNγ (Fig. 2H). Treatment with H4 reinstated the suppressed ACE2 activity caused by bacterial infection (Fig. 2D), mitigated weight loss (Fig. 2E), alleviated histopathology (Fig. 2F), reduced proinflammatory cytokine levels in the lung (Fig. 2G, H), diminished neutrophil infiltration (Fig. 2I, J), and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) (Fig. K-M) in mice challenged with P. aeruginosa. This confirmation demonstrates the capacity of H4 to enhance ACE2 activity in vivo. Such outcomes highlight the advantageous effects of H4 in mitigating inflammation and ameliorating associated lung injuries in our disease model.

Fig. 2.

Administration of H4 reduces lung injury and impacts neutrophil infiltration in bacterial pneumonia model. (A) Experimental procedure of H4 administration following bacterial injection. (B—D) The Ace2 mRNA expression (B), ACE2 protein expression (C) and ACE2 activity (D) in the lung tissues of control mice (Ctrl, n = 5), mice infected with P. aeruginosa (P.a, n = 5), and mice infected with P. aeruginosa and then treated with H4 (P.a H4, n = 5). (E) Body weight changes at the time of sacrifice for indicated experimental groups. (F) H&E-stained representative images of indicated experimental groups. Scale bars, 100 μm. (G-H) The expression of proinflammatory cytokines TNFγ (G) and IFNγ (H) in the lung tissues of indicated experimental groups. (I) Neutrophil numbers in BAL as determined by flow cytometry, gated as CD45+CD11b+Ly6G+ in live cells. (J) Representative immunofluorescence images for neutrophil marker MPO in the lung tissue of indicated experimental groups. Scale bars, 100 μm. (K-M), The expression of neutrophil recruitment chemokines KC (K) CXCL5 (L) and MIP-2 (M). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001, p values obtained from one-way ANOVA followed by multiple comparisons. Each dot in the graphs represents data from an individual mouse.

Given that pulmonary ACE2 activity regulates lung injury induced by LPS [48] or P. aeruginosa [15] by diminishing neutrophil infiltration, we sought to ascertain whether the favorable effects of H4 in the context of bacterial lung infection, similar to recombinant ACE2, stem from its ability to modulate neutrophil infiltration induced by P. aeruginosa. H4 treatment exhibited a substantial reduction in the number of neutrophils (Fig. 2I) in the bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid and mitigated the accumulation of neutrophils in the lungs (Fig. 2J). To delve into the mechanism underlying H4’s mediation of neutrophil recruitment in mouse lung during bacterial infection, we measured expression levels of neutrophil recruitment chemokines KC (Fig. 2K), CXCL5 (Fig. 2L), and MIP-2 (Fig. 2M). The results clearly demonstrate that H4 robustly suppressed the production of these chemokines and cytokines in mouse lungs, suggesting that H4 curtails neutrophil infiltration in bacterial pneumonia by impacting the production of chemokines responsible for neutrophil recruitment.

3.3. H4 reduces lung injury in the bacterial pneumonia model in an ACE2-dependent manner

A notable challenge associated with utilizing existing ACE2 activators as potential therapies pertains to concerns about their lack of specificity and possible adverse off-target effects. To further demonstrate that the advantageous impact of H4 in the context of bacterial pneumonia specifically stems from ACE2 activation, we employed global ACE2 knockout (Ace2−/−) mice. These mice exhibited a complete absence of Ace2 mRNA expression (Fig. 3A), ACE2 protein expression (Fig. 3B), and ACE2 activity in the lung (Fig. 3C) under naïve conditions.

Fig. 3.

H4 reduces lung injury in a bacterial pneumonia model via ACE2. (A-C) The Ace2 mRNA expression (A), ACE2 protein expression (B) and ACE2 activity (C) in the lung tissue of wildtype mice (WT, n = 7) and Ace2−/− mice (Ace2−/−, n = 7). (D) Body weight changes at the time of sacrifice of Ace2−/− mice infected with P. aeruginosa (P.a, n = 3) and Ace2−/− mice infected with P. aeruginosa and treated with H4 (P.a H4, n = 3). (E) H&E-stained representative images of indicated experimental groups. Scale bars, 100 μm. (F) The expression of proinflammatory cytokine IFNγ in the lung tissue of indicated experimental groups. (G) Neutrophil numbers in BAL as determined by flow cytometry, gated as CD45+CD11b+Ly6G+ in live cells. (H) Representative immunofluorescence images for neutrophil marker MPO in the lung tissue of indicated experimental groups. Scale bars, 100 μm. (I) The expression of neutrophil recruitment chemokine MIP-2. ****p < 0.0001, p values obtained from two-sided t-tests. Each dot in graphs represents data from an individual mouse.

Within our P. aeruginosa-induced bacterial pneumonia mouse model, H4 treatment exhibited no discernible effects on body weight recovery (Fig. 3D), histopathology (Fig. 3E), or the generation of proinflammatory cytokine IFNγ (Fig. 3F). Furthermore, H4 treatment did not diminish neutrophil infiltration into the lungs as induced by bacterial lung infection (Fig. 3G, H), nor did it decrease the production of MIP-2 (Fig. 3I). These findings corroborate that ACE2 is essential for the favorable impacts of H4 in ameliorating bacterial pneumonia, further establishing H4 as an ACE2 activator of high specificity.

3.4. H4 prodrug design, synthesis, and self-assembly

Due to its predominantly hydrophobic nature, H4 presents challenges in achieving a satisfactory dissolution profile in water (0.5 mg/mL at 25 °C). Consequently, the concentration of H4 that can be safely administered to the lungs of mice in our bacterial infection model is limited. Higher concentrations lead to H4 aggregation, resulting in the formation of detrimental lumps that could compromise lung health and undermine the clinical viability of H4. To address solubility concerns, we designed and synthesized a self-assembling peptide-drug conjugate (Fig. 4A), employing a molecular design strategy that has been recently used for the development self-assembling prodrugs for cancer [49–57] and infectious diseases [58–61]. This conjugate is comprised of a tetrapeptide (Val-Val-Glu-Glu-NH2; Val = Valine, and Glu = Glutamic Acid) covalently linked to a H4-succinic acid prodrug moiety.

Fig. 4.

Design and assembly of the H4 prodrug with improved water solubility and self-assembly ability under physiological conditions. (A) Chemical structure of the designed H4 drug-peptide conjugate. (B) Photographs of aqueous solutions containing H4 (Left) and the designed H4 prodrug (Right) at a concentration of 1 mg/mL, which clearly reveals the improved water solubility of the prodrug. (C) Schematic illustration of molecular assembly of the H4 project into supramolecular filaments upon dissolution in water. (D) Representative TEM micrograph of supramolecular filaments formed by self-assembly of the designed H4 prodrug in PBS at a concentration of 5 mM.

The H4-succinic acid moiety was prepared through a series of conjugation steps (Scheme S1). Briefly, the vicinal diol of H4’s 16α and 17β hydroxyl groups were protected as a corresponding acetonide, followed by the conjugation of succinic acid onto the remaining 3β hydroxyl group, and the subsequent deprotection of the acetonide group. During each step, 1H NMR and mass spectroscopy confirmed the anticipated chemical product (Figs. S2–S5). An amphiphilic H4 prodrug-peptide conjugate was then formed by attaching the H4-succinic acid compound to a β-sheet-forming tetrapeptide sequence, Fmoc-Val-Val-Glu-Glu-NH2, using SPPS [62]. Purification of the H4 prodrug was conducted by RP-HPLC, and the mass-to-charge ratio (m/z) of the H4 prodrug was 866.9 (Fig. S6), confirming successful synthesis and purification.

In addition to its improved solubility in water (Fig. 4B), the amphiphilic feature of the designed H4 prodrug enables its assembly into supramolecular nanostructures when dissolved in water (Fig. 4C). As shown in Fig. 4D, a representative TEM image of a 5 mM H4 prodrug solution in PBS reveals dominant filamentous structures as a result of combined intermolecular hydrogen bonding with hydrophobic collapse [63]. The nonpolar valine residues are known to have a high propensity to form a β-sheet secondary structure. Stupp Lab has shown that a peptide amphiphile containing a palmitoyl tail and the tetrapeptide VVEE can self-assemble into supramolecular nanofibers of ~9 nm in diameter [64]. In the case here, aromatic-aromatic interactions among the H4 moieties may also contribute to enhance the associative interactions among the H4 prodrugs [65].

3.5. H4 prodrug exhibits minimal cytotoxicity and ACE2 activity induction and lung protection comparable to that of H4

To illustrate the clinical potential of the H4 prodrug, we first performed an in vitro biocompatibility assessment using the MTT assay to evaluate the viability of NIH 3T3 mouse fibroblast cells upon exposure to various concentrations of the prodrug. Given that H4 is an FDA-approved drug utilized in various disease contexts, our studies were primarily concentrated on examining the biocompatibility of the newly formulated prodrug. As depicted in Fig. 5A, the fibroblast cell survival rate remained nearly 100% after 48 h of incubation with the highest tested concentration of 100 μM H4 prodrug, confirming the biocompatibility and minimal toxicity of this self-assembling H4 prodrug. To test in vivo biocompatibility, the prodrug was delivered to mice at a concentration of 2.5 mg/mL (30 μl/mouse) via nasal inhalation. A pathological assessment was conducted on mouse lungs 18 h post-treatment. As delineated in Fig. S7, the H4 prodrug neither instigated histopathological alterations nor heightened apoptotic cell numbers in the lungs. Furthermore, there was no surge in pro-inflammatory cytokine levels in lung tissues, indicating non-detectable toxicity of the prodrug in the lungs.

Fig. 5.

H4 prodrug shows similar beneficial effects in bacterial pneumonia model to H4. (A) Cell viability of cultured NIH/3 T3 cells treated with different doses of H4 and prodrug. (B—D) The Ace2 mRNA expression (B), ACE2 protein expression (C) and ACE2 activity (D) in the lung tissue of mice infected with P. aeruginosa and treated with H4 (P.a H4, n = 5) and mice infected with P. aeruginosa and treated with prodrug (P.a prodrug, n = 5). (E) Body weight changes at the time of sacrifice of indicated experimental groups. (F) H&E-stained representative images of indicated experimental groups. Scale bars, 100 μm. (G-H) The expression of proinflammatory cytokines TNFγ (G) and IFNγ (H) in the lung tissue of indicated experimental groups. (I) Neutrophil numbers in BAL as determined by flow cytometry, gated as CD45+CD11b+Ly6G+ in live cells. (J) Representative immunofluorescence images for neutrophil marker MPO in the lung tissue of indicated experimental groups. Scale bars, 100 μm. (K-M) The expression of neutrophil recruitment chemokines KC (K), CXCL5 (L) and MIP-2 (M). p values obtained from two-sided t-tests. Each dot in graphs represents data from an individual mouse.

To assess the in vivo ACE2 activity-enhancing capability of the H4 prodrug, we inoculated wild type C57 BL/6 mice with P. aeruginosa and subsequently administered either H4 or the H4 prodrug via nasal instillation 18 h after bacterial challenge. Comparing the effects to those of H4, the prodrug exhibited similar impacts on Ace2 mRNA expression (Fig. 5B), ACE2 protein production (Fig. 5C), and ACE2 activity (Fig. 5D) in the lungs of P. aeruginosa-infected mice. The prodrug treatment demonstrated nearly identical beneficial effects in mitigating inflammatory responses as observed with H4 alone. This was evidenced by improved body weight recovery (Fig. 5E), enhanced histology (Fig. 5F), diminished production of proinflammatory cytokines TNFα(Fig. 5G) and IFNγ (Fig. 5H) and reduced neutrophil infiltration in the lung (Fig. 5I, J). Moreover, the prodrug reduced neutrophil recruitment chemokines KC (Fig. 5K), CXCL5 (Fig. 5L), and MIP-2 (Fig. 5M) to a comparable extent as H4. These results strongly indicate that the enhanced solubility of the H4 prodrug does not compromise the beneficial effects of H4 in modulating inflammatory responses during bacterial lung infection.

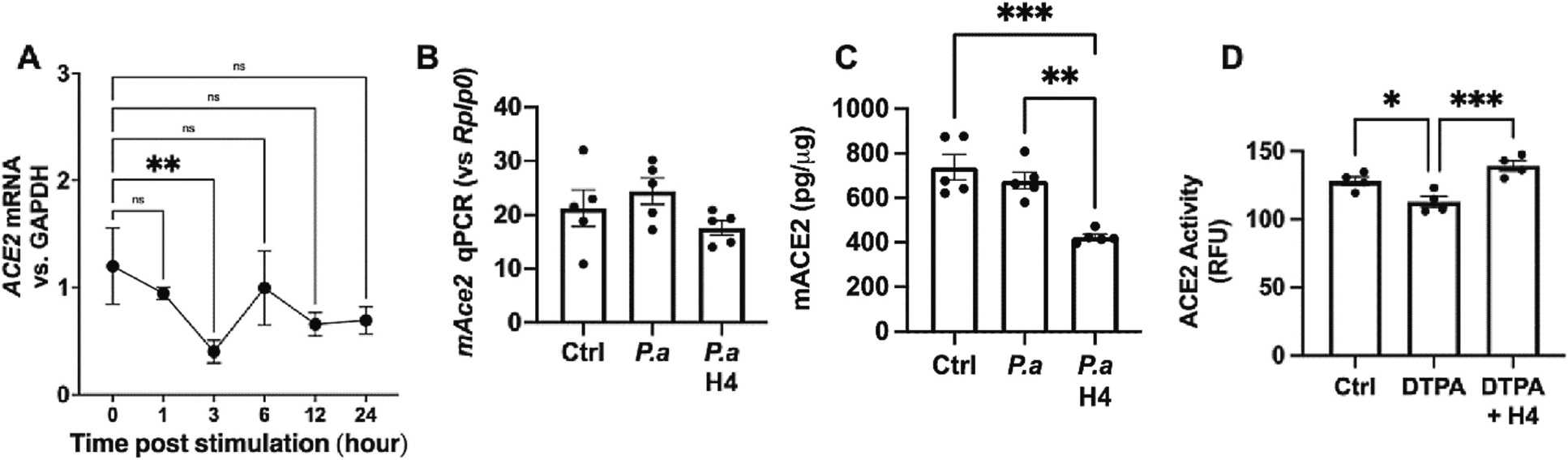

3.6. H4 restores ACE2 activity inhibited by Zn depletion

Finally, we sought to elucidate the underlying mechanism through which H4 enhances ACE2 activity. Given that H4 effectively increases ACE2 activity in Calu-3 cells in a dose- and time-dependent manner (Figs. 1B, C), we examined ACE2 mRNA levels upon stimulation of these cells with 25 μg/mL H4 for varying durations. The results presented in Fig. 6A indicate that H4 did not induce ACE2 gene expression across all time points investigated. Furthermore, as depicted in Fig. 6B, H4 did not induce an increase in Ace2 mRNA expression or ACE2 protein production in the lungs of mice challenged with Pseudomonas bacterial infection (Figs. 6B, C). However, as demonstrated in Fig. 2D, administration of H4 effectively restores the reduced ACE2 activity resulting from P. aeruginosa lung infection. This strongly implies that the enhancement of ACE2 activity by H4 in our experimental model is not mediated through alterations in ACE2 expression at the transcriptional or translational levels.

Fig. 6.

Zn depletion reversed the increases ACE2 activity by H4. (A) The expression of ACE2 mRNA in cultured Calu-3 cells treated with 25 mg/mL H4 and harvested at different times. (B—C) The expression of ACE2 mRNA in the lungs and ACE2 levels in BALF from mice inoculated with P.a for 48 h with or without H4 administration (10mg/kg) 18 h post bacterial inoculation. (D) The ACE2 activity of the recombinant ACE2 treated with 200 ng/mL H4 or/and 25 mM DTPA. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001, p values obtained from one-way ANOVA followed by multiple comparisons. Each dot in graphs represents data from an individual well of treatment. n≥4 in all in vivo studies.

Based on the cumulative evidence thus far, a plausible scenario emerges, suggesting that H4 might directly interact with ACE2 to facilitate its enzymatic activity. Recognizing that ACE2 is known to be a type I transmembrane glycoprotein containing a Zn-binding motif, with Zn playing a pivotal role in ACE2 activity [66], we embarked on exploring whether ACE2 activity could be influenced by its interaction with Zn and its binding motif. In a chemical interaction assay, as illustrated in Fig. 6D, we found that depleting free Zn through its chelator DTPA substantially diminishes ACE2 activity. Strikingly, H4 demonstrated an ability to restore the ACE2 activity that had been inhibited by DTPA, indicating that the enhancement of ACE2 activity by H4 may, in part, arise from its capacity to influence the binding of Zn to the motif situated within the ACE2 enzymatic moiety.

4. Discussion

In this study, we have unveiled a novel ACE2 activator designated as H4, demonstrating its capability to enhance ACE2 activity both in vitro and in vivo, contingent upon the presence of ACE2. Most importantly, we have developed a prodrug for H4 to improve its solubility and facilitate its clinical usability. Despite the recent advancements in various pulmonary drug delivery systems for treating inflammatory lung diseases [67–76], there is still a critical need for the discovery and validation of new drugs.

In addition to its critical role in regulating cardiovascular functions and as a cognate receptor for certain coronaviruses, mounting evidence highlights ACE2’s capacity to influence the host’s innate immune responses against invading pathogens by modulating inflammatory processes. Consequently, ACE2 emerges as a promising target for preventing and treating inflammatory diseases. However, translating this potential into clinical practice has been hindered, in part, by the absence of properly formulated recombinant ACE2 or highly effective, low-toxicity activators. In the current study, by screening an FDA-approved drug library, we identified an ACE2 activator named H4 among other candidates. In an in vitro study using Calu-3 cells as a platform, we observed that H4 enhances ACE2 activity in a dose-dependent manner with a mid-effective at 10–30 μg/mL and reaches a plateau of around 50 μg/mL. Moreover, we determined that H4’s effectiveness at enhancing ACE2 activity peaked around 12 h after H4 stimulation in cultured Calu-3 cells. This distinctive feature positions H4 as a potential ACE2 activator for acute-phase treatment of inflammatory diseases, setting it apart from existing ACE2 activators like DIZA and XNT that typically require prolonged stimulation periods for similar effects.

The therapeutic potential of H4 in treating acute and chronic inflammation is further supported by in vivo studies. Our results indicate that H4 significantly mitigates the inflammatory reactions provoked by Pseudomonas Aeruginosa bacterial lung infection, targeting a critical time when escalated inflammation and ensuing lung damage could emerge. Furthermore, we established that H4’s anti-inflammatory effects are attributed to its capacity to impede the infiltration of proinflammatory neutrophils into the lung. This is achieved through the downregulation of cytokines and chemokines that play pivotal roles in the recruitment of neutrophils, aligning with our prior research elucidating the mechanisms through which ACE2 orchestrates its anti-inflammatory responses. A key revelation in this study is the validation of H4’s ACE2-dependent influence on inflammatory responses, a characteristic that distinguishes it from DIZE or XNT. The loss of this capacity in ACE2-deficient mice underscores the potential of H4 as a clinical intervention with significantly heightened specificity compared to the approved agents DIZE or XNT, which exhibit considerable off-target effects. This specific mode of action further underscores H4’s potential as a precise and effective therapeutic option for managing inflammation-related conditions.

While the underlying mechanism of how H4 enhances ACE2 activity remains uncertain in this study, we have observed intriguing properties of H4 that merit further investigation. Importantly, our findings suggest that H4’s mode of action does not involve inducing ACE2 gene expression, which could be advantageous in the context of treating COVID-19. H4’s ability to facilitate ACE2 activity without increasing available cognate receptors for the SARS-CoV-2 virus is a potential benefit. Although we have shown that H4 can counteract the reduction in ACE2 activity caused by Zn chelation, the precise mechanism underlying this effect warrants further investigation. This could involve H4’s interaction with the chelator, modulation of Zn binding to the ACE2 moiety, or a combination of these factors, necessitating comprehensive future studies.

Prodrug strategies offer a versatile approach to enhance therapeutic outcomes by addressing various challenges associated with drug delivery and efficacy. These strategies encompass a range of benefits including improved bioavailability, enhanced solubility, augmented passive intestinal absorption, prevention of premature drug degradation, facilitation of cell permeability, and mitigation of systemic toxic side effects [77]. Peptide-based self-assembling drug amphiphiles complement the existing prodrug strategy to produce drug-based well-defined supramolecular nanostructures upon physiological conditions [59]. The use of short peptides in prodrug design is particularly interesting due to their relative stability, tunable physical and chemical characteristics, facile synthesis, biocompatibility, biodegradability, suitable functionality, and ability to release hydrophilic and hydrophobic drugs in a controlled manner [78,79]. The present study has demonstrated that the covalent linkage of a tetrapeptide (VVEE) to the H4 molecule results in a conjugate that exhibits significantly enhanced water solubility while maintaining its in vitro and in vivo effectiveness. Furthermore, this conjugate retains the capacity to self-assemble into micrometer-long supramolecular filaments, a characteristic that could offer many other advantages and hold significant implications for its translation into clinical applications. While there remain numerous experimental parameters to explore in prodrug design to further improve and optimize its efficacy, the work presented here has demonstrated significant promise of this approach.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, our findings have led to the discovery of a novel ACE2 activator, H4, characterized by its remarkable specificity towards ACE2, minimal cytotoxicity, and potential for use in acute-phase treatment of inflammatory disorders. We have also developed a prodrug formulation for H4, enhancing its solubility for potential clinical applications. Notably, the H4 prodrug holds promise as an inhalable therapeutic option for inflammatory lung diseases. This is of significant relevance, especially during ongoing and prospective outbreaks or pandemics involving respiratory viral or bacterial pneumonia.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This project is supported by the NIH 1R2AI14932101, 3R21AI149321-01S1, and 1R01AI148446-01A1 to H.J.

Footnotes

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Peng Lu: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation. Faith Leslie: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation. Han Wang: Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis. Anjali Sodhi: Investigation. Chang-yong Choi: Investigation. Andrew Pekosz: Writing – review & editing, Resources, Funding acquisition. Honggang Cui: Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Hongpeng Jia: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Conceptualization.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jconrel.2023.10.025.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- [1].Paz Ocaranza M, Riquelme JA, Garcia L, Jalil JE, Chiong M, Santos RAS, Lavandero S, Counter-regulatory renin-angiotensin system in cardiovascular disease, Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 17 (2020) 116–129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Belmin J, Levy BI, Michel JB, Changes in the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone axis in later life, Drugs Aging 5 (1994) 391–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Giestas A, Palma I, Ramos MH, Renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) and its pharmacologic modulation, Acta Medica Port. 23 (2010) 677–688. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Haruna Y, Suzuki Y, Yanagibori R, Kawakubo K, Gunji A, Activated renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system and its effects on cardiovascular system during 20-days horizontal bed rest, J. Gravit. Physiol. 2 (1995) P27–P28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Lumbers ER, Head R, Smith GR, Delforce SJ, Jarrott B, J HM, Pringle KG, The interacting physiology of COVID-19 and the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system: key agents for treatment, Pharmacol. Res. Perspect. 10 (2022) e00917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Remuzzi G, Perico N, Macia M, Ruggenenti P, The role of renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system in the progression of chronic kidney disease, Kidney Int. Suppl. (2005) S57–S65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Sokol SI, Portnay EL, Curtis JP, Nelson MA, Hebert PR, Setaro JF, Foody JM, Modulation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system for the secondary prevention of stroke, Neurology 63 (2004) 208–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Stevens TL, Burnett JC Jr., Kinoshita M, Matsuda Y, Redfield MM, A functional role for endogenous atrial natriuretic peptide in a canine model of early left ventricular dysfunction, J. Clin. Invest. 95 (1995) 1101–1108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Cremer S, Pilgram L, Berkowitsch A, Stecher M, Rieg S, Shumliakivska M, Bojkova D, Wagner JUG, Aslan GS, Spinner C, Luxan G, Hanses F, Dolff S, Piepel C, Ruppert C, Guenther A, Ruthrich MM, Vehreschild JJ, Wille K, Haselberger M, Heuzeroth H, Hansen A, Eschenhagen T, Cinatl J, Ciesek S, Dimmeler S, Borgmann S, Zeiher A, group L.s., Angiotensin II receptor blocker intake associates with reduced markers of inflammatory activation and decreased mortality in patients with cardiovascular comorbidities and COVID-19 disease, PLoS One 16 (2021), e0258684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Gupta D, Kumar A, Mandloi A, Shenoy V, Renin angiotensin aldosterone system in pulmonary fibrosis: pathogenesis to therapeutic possibilities, Pharmacol. Res. 174 (2021), 105924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Iwasaki M, Saito J, Zhao H, Sakamoto A, Hirota K, Ma D, Inflammation triggered by SARS-CoV-2 and ACE2 augment drives multiple organ failure of severe COVID-19: molecular mechanisms and implications, Inflammation 44 (2021) 13–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Jerng JS, Hsu YC, Wu HD, Pan HZ, Wang HC, Shun CT, Yu CJ, Yang PC, Role of the renin-angiotensin system in ventilator-induced lung injury: an in vivo study in a rat model, Thorax 62 (2007) 527–535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Lee C, Choi WJ, Overview of COVID-19 inflammatory pathogenesis from the therapeutic perspective, Arch. Pharm. Res. 44 (2021) 99–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Mascolo A, Scavone C, Rafaniello C, De Angelis A, Urbanek K, di Mauro G, Cappetta D, Berrino L, Rossi F, Capuano A, The role of renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system in the heart and lung: focus on COVID-19, Front. Pharmacol. 12 (2021), 667254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Sodhi CP, Nguyen J, Yamaguchi Y, Werts AD, Lu P, Ladd MR, Fulton WB, Kovler ML, Wang S, Prindle T Jr., Zhang Y, Lazartigues ED, Holtzman MJ, Alcorn JF, Hackam DJ, Jia H, A dynamic variation of pulmonary ACE2 is required to modulate neutrophilic inflammation in response to Pseudomonas aeruginosa lung infection in mice, J. Immunol. 203 (2019) 3000–3012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Ventura D, Carr AL, Davis RD, Silvestry S, Bogar L, Raval N, Gries C, Hayes JE, Oliveira E, Sniffen J, Allison SL, Herrera V, Jennings DL, Page RL 2nd, McDyer JF, Ensor CR, Renin angiotensin aldosterone system antagonism in 2019 novel coronavirus acute lung injury, Open Forum. Infect. Dis. 8 (2021) ofab170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Grabherr S, Waltenspuhl A, Buchler L, Lutge M, Cheng HW, Caviezel-Firner S, Ludewig B, Krebs P, Pikor NB, An innate checkpoint determines immune dysregulation and immunopathology during pulmonary murine coronavirus infection, J. Immunol. 210 (6) (2023) 774–785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Lieberum JN, Kaiser S, Kalbhenn J, Burkle H, Schallner N, Predictive markers related to local and systemic inflammation in severe COVID-19-associated ARDS: a prospective single-center analysis, BMC Infect. Dis. 23 (2023) 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Russell CD, Lone NI, Baillie JK. Comorbidities, multimorbidity and COVID-19. Nat. Med. (2023); 29(2): 334–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Writing Committee for the R-CAPI, Higgins AM, Berry LR, Lorenzi E, Murthy S, McQuilten Z, Mouncey PR, Al-Beidh F, Annane D, Arabi YM, Beane A, van Bentum-Puijk W, Bhimani Z, Bonten MJM, Bradbury CA, Brunkhorst FM, Burrell A, Buzgau A, Buxton M, Charles WN, Cove M, Detry MA, Estcourt LJ, Fagbodun EO, Fitzgerald M, Girard TD, Goligher EC, Goossens H, Haniffa R, Hills T, Horvat CM, Huang DT, Ichihara N, Lamontagne F, Marshall JC, McAuley DF, McGlothlin A, McGuinness SP, McVerry BJ, Neal MD, Nichol AD, Parke RL, Parker JC, Parry-Billings K, Peters SEC, Reyes LF, Rowan KM, Saito H, Santos MS, Saunders CT, Serpa-Neto A, Seymour CW, Shankar-Hari M, Stronach LM, Turgeon AF, Turner AM, van de Veerdonk FL, Zarychanski R, Green C, Lewis RJ, Angus DC, McArthur CJ, Berry S, Derde LPG, Gordon AC, Webb SA, Lawler PR, Long-term (180-Day) outcomes in critically ill patients with COVID-19 in the REMAP-CAP randomized clinical trial, JAMA 329 (2023) 39–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Bader M, ACE2, angiotensin-(1–7), and mas: the other side of the coin, Pflugers Arch. 465 (2013) 79–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Batlle D, Soler MJ, Wysocki J, New aspects of the renin-angiotensin system: angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 - a potential target for treatment of hypertension and diabetic nephropathy, Curr. Opin. Nephrol. Hypertens. 17 (2008) 250–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Danilczyk U, Eriksson U, Oudit GY, Penninger JM, Physiological roles of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2, Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 61 (2004) 2714–2719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Donoghue M, Hsieh F, Baronas E, Godbout K, Gosselin M, Stagliano N, Donovan M, Woolf B, Robison K, Jeyaseelan R, Breitbart RE, Acton S, A novel angiotensin-converting enzyme-related carboxypeptidase (ACE2) converts angiotensin I to angiotensin 1–9, Circ. Res. 87 (2000) E1–E9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Jia H, Pulmonary angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) and inflammatory lung disease, Shock 46 (2016) 239–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Oudit GY, Crackower MA, Backx PH, Penninger JM, The role of ACE2 in cardiovascular physiology, Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 13 (2003) 93–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Jia H, Neptune E, Cui H, Targeting ACE2 for COVID-19 therapy: opportunities and challenges, Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 64 (2021) 416–425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Crackower MA, Sarao R, Oudit GY, Yagil C, Kozieradzki I, Scanga SE, Oliveira-dos-Santos AJ, da Costa J, Zhang L, Pei Y, Scholey J, Ferrario CM, Manoukian AS, Chappell MC, Backx PH, Yagil Y, Penninger JM, Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 is an essential regulator of heart function, Nature 417 (2002) 822–828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Dantas AP, Sandberg K, Regulation of ACE2 and ANG-(1–7) in the aorta: new insights into the renin-angiotensin system in the control of vascular function, Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 289 (2005) H980–H981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Diez-Freire C, Vazquez J, Correa de Adjounian MF, Ferrari MF, Yuan L, Silver X, Torres R, Raizada MK, ACE2 gene transfer attenuates hypertension-linked pathophysiological changes in the SHR, Physiol. Genomics 27 (2006) 12–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Raizada MK, Ferreira AJ, ACE2: a new target for cardiovascular disease therapeutics, J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 50 (2007) 112–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Tikellis C, Pickering R, Tsorotes D, Du XJ, Kiriazis H, Nguyen-Huu TP, Head GA, Cooper ME, Thomas MC, Interaction of diabetes and ACE2 in the pathogenesis of cardiovascular disease in experimental diabetes, Clin. Sci. (Lond.) 123 (2012) 519–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Murakami N, Hayden R, Hills T, Al-Samkari H, Casey J, Del Sorbo L, Lawler PR, Sise ME, Leaf DE, Therapeutic advances in COVID-19, Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 19 (2023) 38–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Anderson CF, Wang Q, Stern D, Leonard EK, Sun B, Fergie KJ, Choi C.-y., Spangler JB, Villano J, Pekosz A, Brayton CF, Jia H, Cui H, Supramolecular filaments for concurrent ACE2 docking and enzymatic activity silencing enable coronavirus capture and infection prevention, Matter, 6 (2023) 583–604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Burchill LJ, Velkoska E, Dean RG, Griggs K, Patel SK, Burrell LM, Combination renin-angiotensin system blockade and angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 in experimental myocardial infarction: implications for future therapeutic directions, Clin. Sci. (Lond.) 123 (2012) 649–658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Qi Y, Zhang J, Cole-Jeffrey CT, Shenoy V, Espejo A, Hanna M, Song C, Pepine CJ, Katovich MJ, Raizada MK, Diminazene aceturate enhances angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 activity and attenuates ischemia-induced cardiac pathophysiology, Hypertension 62 (2013) 746–752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Chappell MC, Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 autoantibodies: further evidence for a role of the renin-angiotensin system in inflammation, Arthritis Res. Ther. 12 (2010) 128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Arthur JM, Forrest JC, Boehme KW, Kennedy JL, Owens S, Herzog C, Liu J, Harville TO, Development of ACE2 autoantibodies after SARS-CoV-2 infection, PLoS One 16 (2021), e0257016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Miziolek B, Sienczyk M, Grzywa R, Lupicka-Slowik A, Kucharz E, Kotyla P, Bergler-Czop B, The prevalence and role of functional autoantibodies to angiotensin-converting-enzyme-2 in patients with systemic sclerosis, Autoimmunity 54 (2021) 181–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Casciola-Rosen L, Thiemann DR, Andrade F, Trejo-Zambrano MI, Leonard EK, Spangler JB, Skinner NE, Bailey J, Yegnasubramanian S, Wang R, Vaghasia AM, Gupta A, Cox AL, Ray SC, Linville RM, Guo Z, Searson PC, Machamer CE, Desiderio S, Sauer LM, Laeyendecker O, Garibaldi BT, Gao L, Damarla M, Hassoun PM, Hooper JE, Mecoli CA, Christopher-Stine L, Gutierrez-Alamillo L, Yang Q, Hines D, Clarke WA, Rothman RE, Pekosz A, Fenstermacher KZ, Wang Z, Zeger SL, Rosen A, IgM anti-ACE2 autoantibodies in severe COVID-19 activate complement and perturb vascular endothelial function, JCI Insight 7 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Khajeh Pour S, Scoville C, Tavernier SS, Aghazadeh-Habashi A, Plasma angiotensin peptides as biomarkers of rheumatoid arthritis are correlated with anti-ACE2 auto-antibodies level and disease intensity, Inflammopharmacology 30 (2022) 1295–1302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Labandeira CM, Pedrosa MA, Quijano A, Valenzuela R, Garrido-Gil P, Sanchez-Andrade M, Suarez-Quintanilla JA, Rodriguez-Perez AI, Labandeira-Garcia JL, Angiotensin type-1 receptor and ACE2 autoantibodies in Parkinson s disease, NPJ Parkinsons Dis 8 (2022) 76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Labandeira CM, Pedrosa MA, Suarez-Quintanilla JA, Cortes-Ayaso M, Labandeira-Garcia JL, Rodriguez-Perez AI, Angiotensin system autoantibodies correlate with routine prognostic indicators for COVID-19 severity, Front. Med. (Lausanne) 9 (2022), 840662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Hallmann E, Sikora D, Poniedzialek B, Szymanski K, Kondratiuk K, Zurawski J, Brydak L, Rzymski P, IgG autoantibodies against ACE2 in SARS-CoV-2 infected patients, J. Med. Virol. 95 (2023), e28273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Haber PK, Ye M, Wysocki J, Maier C, Haque SK, Batlle D, Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2-independent action of presumed angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 activators: studies in vivo, ex vivo, and in vitro, Hypertension 63 (2014) 774–782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Chong CR, Chen X, Shi L, Liu JO, Sullivan DJ Jr., A clinical drug library screen identifies astemizole as an antimalarial agent, Nat. Chem. Biol. 2 (2006) 415–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Cho YE, Lomeda RA, Ryu SH, Lee JH, Beattie JH, Kwun IS, Cellular Zn depletion by metal ion chelators (TPEN, DTPA and chelex resin) and its application to osteoblastic MC3T3-E1 cells, Nutr. Res. Pract. 1 (2007) 29–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Sodhi CP, Wohlford-Lenane C, Yamaguchi Y, Prindle T, Fulton WB, Wang S, McCray PB Jr., Chappell M, Hackam DJ, Jia H, Attenuation of pulmonary ACE2 activity impairs inactivation of des-Arg(9) bradykinin/BKB1R axis and facilitates LPS-induced neutrophil infiltration, Am. J. Phys. Lung Cell. Mol. Phys. 314 (2018) L17–L31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Cheetham AG, Chakroun RW, Ma W, Cui H, Self-assembling prodrugs, Chem. Soc. Rev. 46 (2017) 6638–6663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Cheetham AG, Zhang PC, Lin YA, Lock LL, Cui HG, Supramolecular nanostructures formed by anticancer drug assembly, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135 (2013) 2907–2910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Schiapparelli P, Zhang P, Lara-Velazquez M, Guerrero-Cazares H, Lin R, Su H, Chakroun RW, Tusa M, Quiñones-Hinojosa A, Cui H, Self-assembling and self-formulating prodrug hydrogelator extends survival in a glioblastoma resection and recurrence model, J. Control. Release 319 (2020) 311–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Su H, Wang F, Ran W, Zhang W, Dai W, Wang H, Anderson CF, Wang Z, Zheng C, Zhang P, Li Y, Cui H, The role of critical micellization concentration in efficacy and toxicity of supramolecular polymers, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 117 (2020) 4518–4526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Su H, Wang FH, Wang YZ, Cheetham AG, Cui HG, Macrocyclization of a class of Camptothecin analogues into tubular supramolecular polymers, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141 (2019) 17107–17111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Wang F, Huang Q, Su H, Sun M, Wang Z, Chen Z, Zheng M, Chakroun RW, Monroe MK, Chen D, Wang Z, Gorelick N, Serra R, Wang H, Guan Y, Suk JS, Tyler B, Brem H, Hanes J, Cui H, Self-assembling paclitaxel-mediated stimulation of tumor-associated macrophages for postoperative treatment of glioblastoma, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 120 (2023), e2204621120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Wang F, Su H, Lin R, Chakroun RW, Monroe MK, Wang Z, Porter M, Cui H, Supramolecular Tubustecan hydrogel as chemotherapeutic carrier to improve tumor penetration and local treatment efficacy, ACS Nano 14 (2020) 10083–10094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Wang F, Su H, Wang Z, Anderson CF, Sun X, Wang H, Laffont P, Hanes J, Cui H, Supramolecular filament hydrogel as a universal immunomodulator carrier for immunotherapy combinations, ACS Nano 11 (17) (2023) 10651–10664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Wang FH, Su H, Xu DQ, Dai WB, Zhang WJ, Wang ZY, Anderson CF, Zheng MZ, Oh R, Wan FY, Cui HG, Tumour sensitization via the extended intratumoural release of a STING agonist and camptothecin from a self-assembled hydrogel, Nat, Biomed. Eng. 4 (2020) 1090–1101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Monroe M, Flexner C, Cui H, Harnessing nanostructured systems for improved treatment and prevention of HIV disease, Bioeng. Transl. Med. 3 (2018) 102–123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Monroe MK, Wang H, Anderson CF, Jia H, Flexner C, Cui H, Leveraging the therapeutic, biological, and self-assembling potential of peptides for the treatment of viral infections, J. Control. Release 348 (2022) 1028–1049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Wang H, Monroe MK, Wang F, Sun M, Flexner C, Cui H, Constructing antiretroviral supramolecular polymers as Long-acting Injectables through rational Design of Drug Amphiphiles with alternating antiretroviral-based and hydrophobic residues, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 39 (145) (2023) 21293–21302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Monroe MK, Wang H, Anderson CF, Qin M, Thio CL, Flexner C, Cui H, Antiviral supramolecular polymeric hydrogels by self-assembly of tenofovir-bearing peptide amphiphiles, Biomater. Sci. 11 (2023) 489–498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Wang ST, Lin Y, Spencer RK, Thomas MR, Nguyen AI, Amdursky N, Pashuck ET, Skaalure SC, Song CY, Parmar PA, Morgan RM, Ercius P, Aloni S, Zuckermann RN, Stevens MM, Sequence-dependent self-assembly and structural diversity of islet amyloid polypeptide-derived beta-sheet fibrils, ACS Nano 11 (2017) 8579–8589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Cui H, Webber MJ, Stupp SI, Self-assembly of peptide amphiphiles: from molecules to nanostructures to biomaterials, Peptide Sci.: Orig. Res. Biomol. 94 (2010) 1–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Cui H, Cheetham AG, Pashuck ET, Stupp SI, Amino acid sequence in constitutionally isomeric tetrapeptide amphiphiles dictates architecture of one-dimensional nanostructures, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136 (2014) 12461–12468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Li J, Du X, Hashim S, Shy A, Xu B, Aromatic-aromatic interactions enable alpha-Helix to beta-sheet transition of peptides to form supramolecular hydrogels, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139 (2017) 71–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Tipnis SR, Hooper NM, Hyde R, Karran E, Christie G, Turner AJ, A human homolog of angiotensin-converting enzyme. Cloning and functional expression as a captopril-insensitive carboxypeptidase, J. Biol. Chem. 275 (2000) 33238–33243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Anderson CF, Grimmett ME, Domalewski CJ, Cui H, Inhalable nanotherapeutics to improve treatment efficacy for common lung diseases, Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Nanomed. Nanobiotechnol. 12 (2020), e1586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Qiu YS, Man RCH, Liao QY, Kung KLK, Chow MYT, Lam JKW, Effective mRNA pulmonary delivery by dry powder formulation of PEGylated synthetic KL4 peptide, J. Control. Release 314 (2019) 102–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Gao H, Wang SQ, Long Q, Cheng RY, Lian WH, Koivuniemi A, Ma M, Zhang BD, Hirvonen J, Deng XM, Liu ZH, Ye XF, Santos HA, Rational design of a polysaccharide-based viral mimicry nanocomplex for potent gene silencing in inflammatory tissues, J. Control. Release 357 (2023) 120–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Japiassu KB, Fay F, Marengo A, Louaguenouni Y, Cailleau C, Denis S, Chapron D, Tsapis N, Nascimento TL, Lima EM, Fattal E, Interplay between mucus mobility and alveolar macrophage targeting of surface-modified liposomes, J. Control. Release 352 (2022) 15–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Lai SK, McSweeney MD, Pickles RJ, Learning from past failures: challenges with monoclonal antibody therapies for COVID-19, J. Control. Release 329 (2021) 87–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Pei WY, Li XQ, Bi RL, Zhang X, Zhong M, Yang H, Zhang YY, Lv K, Exosome membrane-modified M2 macrophages targeted nanomedicine: treatment for allergic asthma, J. Control. Release 338 (2021) 253–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Raviv SA, Alyan M, Egorov E, Zano A, Harush MY, Pieters C, Korach-Rechtman H, Saadya A, Kaneti G, Nudelman I, Farkash S, Flikshtain OD, Mekies LN, Koren L, Gal Y, Dor E, Shainsky J, Shklover J, Adir Y, Schroeder A, Lung targeted liposomes for treating ARDS, J. Control. Release 346 (2022) 421–433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Wang S, Lai XX, Li C, Chen M, Hu M, Liu XR, Song YZ, Deng YH, Sialic acid-conjugate modified doxorubicin nanoplatform for treating neutrophil-related inflammation, J. Control. Release 337 (2021) 612–627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Yang Y, Ding Y, Fan B, Wang Y, Mao ZW, Wang WL, Wu J, Inflammation-targeting polymeric nanoparticles deliver sparfloxacin and tacrolimus for combating acute lung sepsis, J. Control. Release 321 (2020) 463–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Zhuang CY, Kang MJ, Lee MHY, Delivery systems of therapeutic nucleic acids for the treatment of acute lung injury/acute respiratory distress syndrome, J. Control. Release 360 (2023) 1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Ettmayer P, Amidon GL, Clement B, Testa B, Lessons learned from marketed and investigational prodrugs, J. Med. Chem. 47 (2004) 2393–2404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Wang H, Monroe M, Leslie F, Flexner C, Cui H, Supramolecular nanomedicines through rational design of self-assembling prodrugs, Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 43 (2022) 510–521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Wang Y, Cheetham AG, Angacian G, Su H, Xie L, Cui H, Peptide–drug conjugates as effective prodrug strategies for targeted delivery, Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 110 (2017) 112–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.