Abstract

Irradiation (IR) is a highly effective cancer therapy, however, IR damage to tumor-adjacent healthy tissues can result in significant co-morbidities and potentially limit the course of therapy. We have previously shown that protein kinase C delta (PKCδ) is required for IR-induced apoptosis and that inhibition of PKCδ activity provides radioprotection in vivo. Here we show that PKCδ regulates histone modification, chromatin accessibility, and double stranded break (DSB) repair through a mechanism that requires SIRT6. Overexpression of PKCδ promotes genomic instability and increases DNA damage and apoptosis. Conversely, depletion of PKCδ increases DNA repair via non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) and homologous recombination (HR) as evidenced by increased formation of DNA damage foci, increased expression of DNA repair proteins, and increased repair of NHEJ and HR fluorescent reporter constructs. Nuclease sensitivity indicates that PKCδ depletion is associated with more open chromatin, while overexpression of PKCδ reduces chromatin accessibility. Epiproteome analysis reveals increased chromatin associated H3K36me2 in PKCδ-depleted cells which is accompanied by chromatin disassociation of KDM2A. We identify SIRT6 as a downstream mediator of PKCδ. PKCδ-depleted cells have increased SIRT6 expression, and depletion of SIRT6 reverses changes in chromatin accessibility, histone modification and DSB repair in PKCδ-depleted cells. Furthermore, depletion of SIRT6 reverses radioprotection in PKCδ-depleted cells. Our studies describe a novel pathway whereby PKCδ orchestrates SIRT6-dependent changes in chromatin accessibility to regulate DNA repair, and define a mechanism for regulation of radiation-induced apoptosis by PKCδ.

Keywords: PKCδ, DNA repair, radioprotection, SIRT6, cell death

INTRODUCTION

Irradiation (IR) is a widely used and highly effective cancer therapy, however, IR damage to tumor-adjacent healthy tissues, particularly in the gut, bone marrow and oral cavity can result in significant co-morbidities (1,2). For example, the vast majority of patients treated with IR for head and neck cancer will suffer from oral mucositis, and many will have permanent damage to their salivary glands resulting in decreased saliva production, chronic oral infections, and xerostomia (3). Therapeutic strategies to prevent or mitigate IR damage to tumor-adjacent tissues are very limited, hence there is a need to develop therapeutic interventions that can help reduce the side effects from IR without impacting treatment.

Of the DNA lesions induced by IR, double stranded breaks (DSB) are the most abundant, and can result in loss of genetic information, chromosomal abnormalities, or cell death if left unrepaired (4). DSBs are repaired by non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) throughout the cell cycle and by homologous recombination (HR) during S and G2 phases (5). Our lab has previously reported that protein kinase C delta (PKCδ) is essential for apoptosis in response to DNA-damaging agents, and that depletion or inhibition of PKCδ provides radioprotection in vivo (6–11). We have identified that nuclear localization of PKCδ is necessary and sufficient for its ability to regulate apoptosis (7), implying a critical role for this kinase in the nucleus. Here we have addressed the mechanism(s) that underly regulation of DNA damage-induced cell death by PKCδ.

Dynamic changes in chromatin structure accompany DNA repair and are mediated by post-translational modifications (PTMs) on histones, including acetylation and methylation (5). In particular, chromatin relaxation is thought to facilitate DNA repair by increasing accessibility to factors that sense, bind, and repair DSBs. Sirtuin 6 (SIRT6) is a chromatin-bound protein from the NAD+-dependent deacetylases and ADP-ribosylases family which is rapidly recruited to DNA damage sites where it increases chromatin accessibility to enable recruitment of downstream DNA damage response (DDR) factors and efficient DNA repair (12). While SIRT6 is widely known for its histone deacetylase activity, it was first identified as a mono-ADP ribosyltransferase enzyme (13). Recently, KDM2A has been identified as a substrate of SIRT6 relevant to DNA repair (14). Here we define a novel pathway whereby PKCδ, via SIRT6, orchestrates changes in chromatin accessibility to regulate DNA repair (bioRxiv 2023.05.24.541991). Our studies identify a mechanism for regulation of DNA damage-induced cell death by PKCδ and suggest novel targets for radioprotection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture and generation of expression plasmids.

The ParC5 rat salivary acinar cell line has been previously described (15). HEK293 cells were obtained from the University of Colorado Cancer Center (UCCC) Cell Technologies Shared Resource, and the human retinal pigmented epithelial (RPE) cell line has been previously described (16). The human cell lines were cultured in DMEM/High glucose medium (Cat # SH30243.02, Thermo Fisher Scientific) supplemented with 10% FBS (Cat # F2442, Sigma). Cell line profiling for authentication was done through the UCCC Cell Technologies Shared Resource. Cells were used within 10 passages of authentication and routinely monitored for mycoplasma. All plasmids used in this study are listed in Supplementary Table S1.

For IR experiments, subconfluent cells were irradiated using a Cesium-137 source. For transient expression, subconfluent ParC5 cells were transfected using a 2μg:3μL DNA:jetPRIME transfection reagent ratio (Polyplus). For HEK293 and RPE cells, subconfluent cells were transfected using a 1μg:2μL and 1μg:1.5μL ratio respectively. For inhibitor experiments, cells were treated with 100 nM trichostatin A (TSA, CAS # 58880-19-6, Cayman Chemical), 5 mM nicotinamide (NAM, CAS # 98-92-0, Cayman Chemical), or 5 mM dimethyl succinate (SUC, CAS # 150731000, Thermo Fisher Scientific) for the indicated times.

Generation of stable cell lines.

Lentiviruses encoding the appropriate shRNAs were generated as previously described (17). ParC5 cells were transformed with lentiviruses encoding unique “non-targeting” shRNAs (Cat # VSC11722, Dharmacon) to generate the shNT control cell line, or two unique species-specific rat shRNAs that target PKCδ (Cat # V3SR11242–243761456, or Cat # V3SR11242–242319029, Dharmacon) to generate the shδ110 and shδ680 cell lines, respectively. HEK293 cells were transformed with lentiviruses that express a non-targeting “scrambled” shRNA (shSCR) as previously described (18), or three unique shRNAs targeting human PKCδ (Cat # TRCN0000010193, Cat # TRCN0000010203 or Cat # TRCN0000284800, Open Biosystems), to generate the shδ193, shδ203 and shδ800 cell lines, respectively. Cells were selected with 2 μg/ml puromycin (Cat # A1113803, Life Technologies) media and maintained in 1 μg/mL puromycin.

The NHEJ and HR reporter plasmids were kindly provided by Dr. Vera Gorbunova (University of Rochester, NY) (19,20). To generate reporter cell lines, the linearized NHEJ or HR reporter cassettes (0.5 μg) were transfected into parental ParC5 cells, ParC5 shδ cell lines (shNT, shδ110, and sh680), or HEK293 shδ cell lines (shSCR, shδ193, shδ203, and sh800) using Amaxa Nucleofector 2B (Basic Nucleofector Kit Primary Mammalian Epithelial Cells, Cat # VPI-1005, Program T-020 for ParC5 cells, and Cell Line Nucleofector Kit V, Cat # VCA-1003, Program Q-001 for HEK293 cells, Lonza). Post 24 hr transfection, cells were selected with 100 μg/mL G418 (Cat # P-600–100, Gold Biotechnology) for 7–10 days and maintained in 100 μg/mL G418 ParC5 media.

To make the rat shSIRT6 cell lines, ParC5 shNT and shδ110 cells containing a stably integrated NHEJ reporter were transformed with a lentivirus that expresses shSCR control (Cat # SHHCTR001, Creative Biogene) or three unique shRNAs targeting rat SIRT6 (Cat # SHH407796–1, SHH407796–2 or SHH407796–3), to generate the stable cell lines referred as shNT-/shδ110-shSCR/shSIRT6–1/shSIRT6–2/shSIRT6–3. For stable expression cells were selected in ParC5 media containing 1 μg/ml puromycin, 100 μg/mL G418 and 500 μg/mL hygromycin B (Cat # H-270–1, Gold Biotechnology), and maintained with 1 μg/ml puromycin, 100 μg/mL G418 and 400 μg/mL hygromycin B.

Neutral comet assay.

Subconfluent cells were exposed to 5 Gy IR and harvested at the indicated times and a neutral comet assay was preformed according to the Trevigen Comet Assay protocol (Trevigen). Images were analyzed by Trevigen Comet Analysis Software (Version 1.3d). Mean tail moment was used to quantify DNA damage. At least 150 comets were counted for each treatment and each cell line.

Micronuclei assay.

RPE cells were transfected with pEGFP-N1 or pEGFP-PKCδ using jetPRIME for 24 hr, selected and maintained in 1.2 mg/mL G418. Cells were plated on coverslips at passage 3. When cells reached 70–80% confluency they were fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 10 min at room temperature, followed by cell permeabilization with 0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS for 10 min. Cells were washed with PBS twice prior to mounting on slides using Vectashield Vibrance mounting media containing DAPI stain (Cat # H-1800, Vector Laboratories). Images were acquired on an Olympus BX51 fluorescent microscope with a 40x objective. JQuantPlus software (provided by Pavel Lobachevsky, Peter MacCallum Institute, Melbourne, AU) (21) was used to identify objects and count micronuclei in each field using the DAPI images. Data is expressed as the average % micronuclei from 20 fields (number of micronuclei / GFP+ cells).

NHEJ and HR repair assays.

DNA repair assays were performed as previously described (22). ParC5 or HEK293 reporter cells were co-transfected with 5 μg pCBASceI (pI-SceI) and 0.1 μg pDsRed2-N1 (pDsRed) (kindly provided by Dr. Vera Gorbunova) using Amaxa Nucleofector 2b. Cells were allowed to repair for 72–96 hrs and were analyzed for GFP and DsRed fluorescence by FACS (Gallios 561). The repair efficiency was calculated as the ratio of GFP+ cells to pDsRed+ cells. For pPKCδFLAG reconstitution, cells were transfected with three plasmids, 5 μg pI-SceI, 0.1 μg pDsRed, and 0.1–1 μg pPKCδFLAG or pEV. For DNA repair assays with inhibitors, cells were pretreated with 100 nM TSA, 5 mM NAM, or 5 mM SUC for 24 hr prior to electroporation and plated in media with the corresponding inhibitors for an additional 72 hr.

Analysis and quantification of DNA damage foci.

Experiments were done as previously described with the following modifications (23). ParC5 cells were grown on coverslips and exposed to 1 Gy IR. For quantification of KDM2A foci, cells were grown to approximately 80% confluency and foci were detected by immunostaining at a dilution of 1:1000 with anti-γH2AX (Cat # 05–636, RRID:AB_309864, Millipore), 1:200 anti-DNA-PK pSer2056 (Cat # ab18192, RRID:AB_869495, Abcam), 1:500 anti-Rad51 (Cat # ABE257, RRID:AB_10850319, Millipore), or 1:1000 anti-KDM2A (Cat # ab191387, RRID:AB_2928955) followed by staining with 1:1000 secondary antibody Alexafluor 488 anti-Rabbit or Alexafluor 568 anti-Mouse (Cat # A11008 RRID:AB_143165 or A11005 RRID:AB_2534073, respectively) from Thermo Fisher Scientific. Coverslips were mounted on slides using Vectashield Vibrance mounting media. A minimum of five fields per condition were obtained on an Olympus BX51 fluorescent microscope with a 40x objective. JQuantPlus software (21) was used to identify objects using the DAPI images, and to count foci. Data is expressed as the average number of foci per cell.

Immunoblot Analysis.

Immunoblot analysis was done as previously described (23). The following antibodies were used: anti-PKCδ (Cat # 14188–1-AP, RRID:AB_10638614) and anti-NBS1 (Cat # 55025–1-AP, RRID:AB_10858928) from Proteintech; anti-DNA Ligase IV (Cat # sc-271299, RRID:AB_10610371), anti-XRCC4 (Cat # sc-271087, RRID:AB_10612396), anti-XLF (Cat # sc-166488, RRID:AB_2152940), anti-SIRT6 (Cat # sc-517556, RRID:AB_2915920), and anti-Mre11 (Cat # sc-135992, RRID:AB_2145244) from Santa Cruz Biotechnology; anti-Artemis (Cat # NBP2–44276, RRID:AB_2915919), anti-β-tubulin (Cat # NB600–936H, RRID:AB_1878245), and anti-H3 (Cat # NBP2–36468, RRID:AB_2925191) from Novus Biologicals; anti-Rad51 (Cat # ABE257, RRID:AB_10850319) from Millipore; anti-Rad50 (Cat # MA5–35412, RRID:AB_2849313) and anti-H3K36me2 (Cat # MA5–14867, RRID:AB_10983670) from Thermo Fisher Scientific; anti-FLAG-tag (Cat # F3165, RRID:AB_259529) from Sigma-Aldrich; anti-KDM2A (Cat # ab191387, RRID:AB_2928955), anti-Lamin B1 (Cat # ab194109, RRID:AB_2933958), and anti-β-actin (Cat # ab49900, RRID:AB_867494) from Abcam; anti-HDAC3 (Cat # 85057, RRID:AB_2800047) from Cell Signaling Technology. Chemiluminescent images were captured digitally using the KwikQuant Image Analyzer (Kindle Biosciences) and densitometry performed using the KwikQuant analysis software. Immunoblots of total protein lysates were normalized to β-actin control, unless otherwise indicated.

qRT-PCR.

Experiments were done as previously described (23). Briefly, ParC5 shδ cells were collected at 60–80% confluency. For overexpression, subconfluent ParC5 cells were transfected with 2 μg pEV or pPKCδFLAG using jetPRIME and let grow for the indicated time. Total RNA was purified (Quick-RNA miniprep kit; Zymo Research) and cDNA was synthesized using a Verso cDNA synthesis kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). All qRT-PCR PrimeTime primers were purchased directly from Integrated DNA Technologies and are listed in Supplementary Table S2. qRT-PCR measurements were done in StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR Systems (Applied Biosystems) using SYBR Select Master Mix. The CT was determined automatically by the instrument. Relative expression fold change was calculated using the 2−ΔΔCT method. The geometric mean (geNorm) normalizations were performed as previously described (23). Gapdh was determined to be a good reference gene for the ParC5 shδ cells, while geNorm of Tbp and B2m genes was used for the ParC5 overexpressing pPKCδFLAG cells. All samples were analyzed in biological triplicates.

Micrococcal nuclease assay.

For PKCδ reconstitution, ParC5 shNT and shδ110 cells were transfected with the indicated plasmids using jetPRIME for 24hr. For inhibitor experiments, ParC5 shNT and shδ110 cells were treated with 5 mM NAM or 5 mM SUC for 48 hrs before collection. Chromatin preparation and salt fractionation are adapted from previously described methods (24) using 2 × 106 cells per reaction with the following modifications. Briefly, cells were harvested at 600 x g for 10 min at room temperature and washed once with PBS. Cells were resuspended in 1 mL NE1 buffer (20 mM HEPES pH 7.8, 10 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM CaCl2, 0.1% Triton X-100, 20% glycerol) and incubated on ice for 10 min. Nuclei were collected and resuspended in 200 μL NE1 buffer with 10 U micrococcal nuclease (MNase) (CAS # 9013-53-0, Worthington Biochemical Corporation). Reactions were incubated at 37°C for 8 min and stopped by adding 2 mM EGTA. Supernatants labeled as “S1” were collected. Pellets were resuspended in 200 μL 80 mM Triton buffer (10 mM Tris pH 7.4, 2 mM MgCl2, 2 mM EGTA, 0.1% Triton X-100, 70 mM NaCl) and incubated at 4°C with gentle shaking for 2 hr. Supernatants were collected and combined with S1 for the “80 mM” fraction. Pellets were resuspended in 200 μL 350 mM Triton buffer (same as 80 mM Triton but containing 340 mM NaCl) and incubated at 4°C overnight. Supernatants were collected for the “350 mM” fraction, and remaining pellets were resuspended in 200 μL 350 mM Triton buffer for the “pellet” fraction.

DNA was extracted from each fraction using phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (PCI) (Cat # AC327115000, Acros Organics). SDS (final concentration 1%) and 20 μg of Proteinase K (Cat # AM2546, Ambion) were added and samples were incubated at 55°C for 15 min, followed by the addition of one volume of PCI. Samples were vortexed and centrifuged at 10 krpm for 10 min and the aqueous phase was collected. RNase A (Cat # EN0531, Thermo Fisher Scientific) was added to a final concentration of 50 μg/mL. The solution was then incubated at 37°C for 30 min, followed by a second PCI extraction. The aqueous phase was collected and the DNA was precipitated by adding 2 volumes of 70% isopropanol, 30 mM sodium acetate, and 0.05 μg/μL glycogen (Cat # R0561, Thermo Fisher Scientific), followed by centrifugation at 16,000 x g for 30 min at 4°C. DNA pellets were washed with cold 75% ethanol, dried completely, and resuspended in TE buffer (10 mM Tris pH 8, 1 mM EDTA). The DNA concentration was assayed using a Nanodrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer (Nanodrop Technologies), and the % DNA in each fraction was calculated. Data is expressed as percent of the control.

Epiproteomic Histone Modification Panel (EHMP).

Profiling of histone modification in ParC5 shδ cells was performed by the Northwestern University Proteomics Core. Briefly, frozen pellets of 3 × 106 ParC5 shNT, shδ110, and shδ680 cells were acid-extracted and samples were derivatized via a propionylation reaction and digested with trypsin (25). Samples were analyzed by liquid chromatography coupled to TSQ Quantum Ultra mass spectrometry.

Acid extraction of histones.

Acid extraction was performed as previously described (26) with a minor modification. In the trichloroacetic acid (TCA)-precipitation step, TCA was added to the histone fraction drop by drop to a final volume of 25%, with mixing in between drops.

Cell fractionation.

Cell fractionation was adapted from previously described method (27). ParC5 cells were resuspended in hypotonic buffer (10 mM Tris pH 7.9, 10 mM KCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM EGTA, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM PMSF and 1X HALT PPI) and incubated on ice for 15 min. After addition of NP-40 to final concentration of 0.625%, the cell lysate was vortexed at high speed for 10 sec, and centrifuged at 16,000 x g for 30 sec to collect supernatant as “cytoplasmic” fraction. The nuclear pellet was resuspended in high salt buffer (20 mM HEPES pH 7.9, 400 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 5 mM EGTA, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM PMSF, and 1X HALT PPI), rotated at 4°C for 15 min, and centrifuged at 16,000 x g for 5 min to collect the supernatant as “nuclear” fraction. The pellet was resuspended in MNase buffer (20 mM Tris pH 7.5, 100 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 1 mM CaCl2, 300 mM sucrose, 0.1% Triton X-100, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM PMSF, and 1X HALT PPI), and sonicated using a Bioruptor Pico (Diagenode) for 10 min (30 sec ON and 30 sec OFF). Then, MNase (5 U/2 million cells) was added for 30 min at room temperature followed by addition of 5 mM EDTA to stop the reaction. Samples were centrifuged at 2000 x g for 5 min at 4°C and the supernatant was collected as the “chromatin” fraction.

Caspase-3 activity assay.

ParC5-NHEJ were transfected with pEV or pPKCδFLAG using jetPRIME for 72 hrs before harvesting cells. For ParC5 shNT/shδ110-shSCR/shSIRT6–2/shSIRT6–3 cells, cells were irradiated with 10 Gy IR and harvested post 24 hr. Cells were lysed and assayed for caspase-3 activity with the Caspase-3 Cellular Activity Assay Kit PLUS (Biomol), which uses N-acetyl-DEVD-p-nitroaniline as a substrate, according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Statistical Analysis.

Graphical data are presented as mean ± standard error of mean (SEM) unless otherwise stated. Statistics were determined using GraphPad Prism 9 (version 9.4.1, RRID:SCR_002798) software. Equal variance and normality were tested to decide which kind of test was run. Specific statistical tests were stated in corresponding figure legends.

Data and materials availability.

All data are available in the main text or the supplementary materials.

RESULTS

PKCδ induces DNA damage and genomic instability.

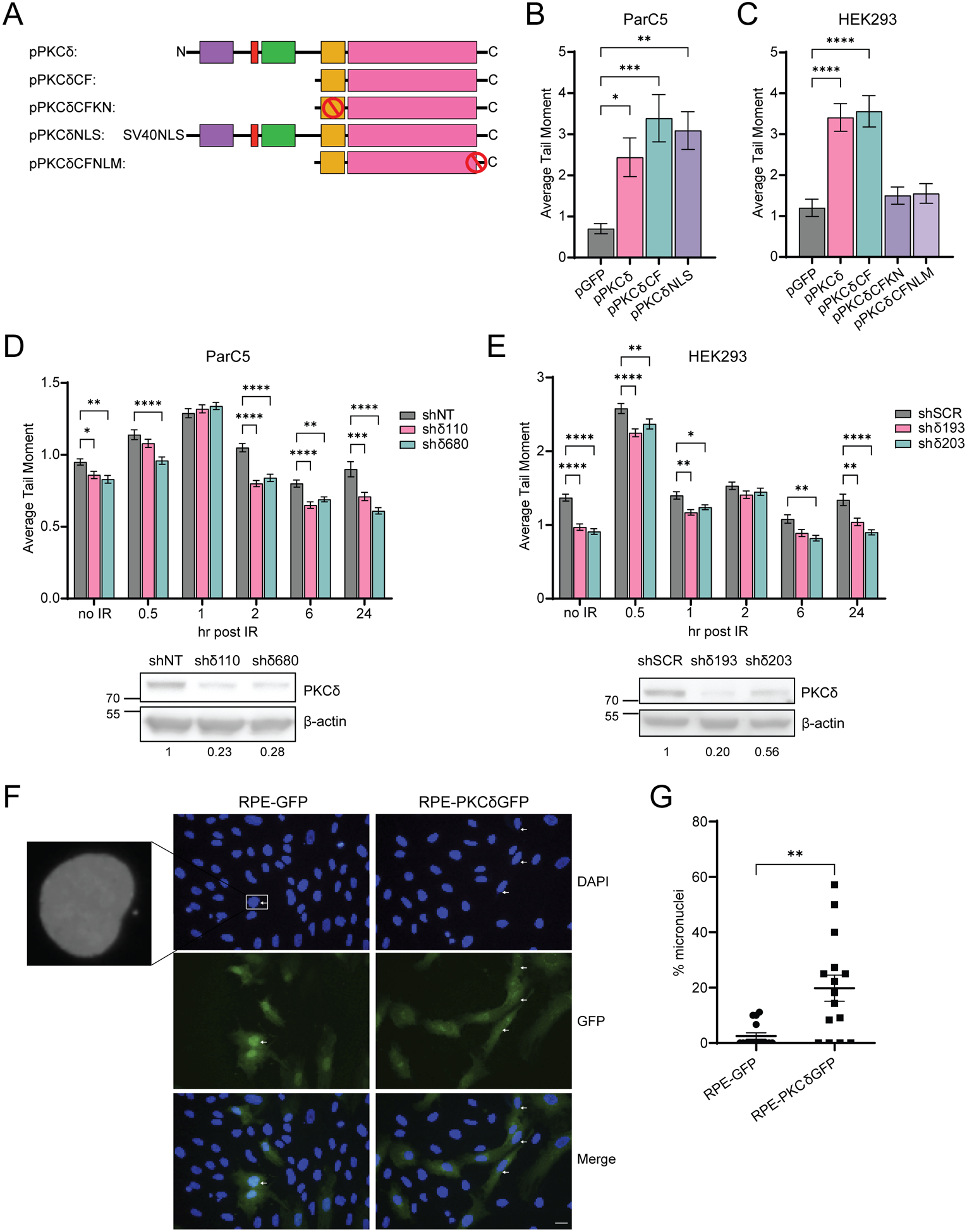

Genomic instability is a characteristic of most cancers, and can include gene mutations as well as alternations in chromosome structure and number (28). We have previously shown that increased expression of PKCδ induces apoptosis, while depletion or inhibition of PKCδ provides radioprotection (6,10,18,29–32). To determine if PKCδ promotes DNA damage and genomic instability, we overexpressed PKCδ in ParC5 cells and quantified DNA damage using a neutral comet assay. ParC5 cells were transiently transfected with plasmids that express wild type PKCδ (pPKCδ), the catalytic fragment of PKCδ (pPKCδCF), or nuclear-targeted full length PKCδ (pPKCδNLS) (33) (Fig. 1A). The catalytic fragment of PKCδ is generated by caspase cleavage in response to DNA damage and localizes to the nucleus due to exposure of a NLS which is cryptic in the full-length protein (7,33). While caspase cleavage of PKCδ amplifies the apoptotic response, it is not required per se (33). All three PKCδ constructs increased DNA damage 3–4-fold compared to control cells (Fig. 1B). Similar results were seen using human embryonic kidney (HEK293) cells (Fig. 1C). In this experiment we also transiently expressed a kinase negative mutant of the catalytic fragment of PKCδ (pPKCδCFKN) and a PKCδ catalytic fragment in which the nuclear localization sequence was mutated to exclude it from the nucleus (pPKCδCFNLM). Both mutations completely abolished the ability of the PKCδ catalytic fragment to induce DNA damage (Fig. 1C) indicating that kinase activity and nuclear localization of PKCδ are both required (32,33).

Fig. 1. PKCδ leads to genomic instability and induces DNA damage.

(A) A schematic of the GFP-tagged PKCδ plasmids used, with red circles indicating mutations. (B) ParC5 and (C) HEK293 cells were transiently transfected with the indicated plasmids for 72 hrs, harvested and assessed for DNA damage using a neutral comet assay. (D) ParC5 shNT, shδ110, and shδ680 cells, and (E) HEK293 shSCR, shδ193, and shδ203 cells were exposed to 5 Gy IR, harvested at the indicated times and assessed for DNA damage using a neutral comet assay. For B-E, data is the mean ± SEM from a representative experiment that was repeated three or more times. Western blots under each figure show the level of PKCδ depletion with the corresponding densitometry of PKCδ normalized to β-actin. (F) Representative images of RPE cells stably expressing pGFP or pPKCδGFP. The white arrows indicate micronuclei. Scale bar = 20 μm. (G) The percent micronuclei was determined by normalizing the number of micronuclei (N = 20 fields/cell line) to the total number of nuclei identified by DAPI staining. Statistics represent one-way ANOVA in (B) and (C) followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparisons to the pGFP controls, two-way ANOVA in (D) and (E) followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparisons within each time point to the corresponding shNT or shSCR control and unpaired t-test in (G). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001.

As depletion of PKCδ suppresses DNA damage-induced apoptosis, we asked if IR-induced DNA damage resolves faster in PKCδ-depleted cells. Surprisingly, the amount of DNA damage in non-irradiated PKCδ-depleted cells (shδ110 and shδ680) was significantly less than that observed in ParC5 shNT cells (Fig. 1D, no IR). A similar trend was seen in PKCδ-depleted HEK293 cells, in which two PKCδ-targeting shRNAs, shδ193 and shδ203, had significantly less DNA damage than the shSCR control under basal conditions (Fig 1E, no IR). Following IR, the induction of DNA damage was similar in ParC5 shNT and PKCδ-depleted shδ110 and shδ680 cells (Fig. 1D, 1hr), however, at 2, 6, and 24 hrs, resolution of IR-induced DNA damage in the two PKCδ-depleted cell lines was faster compared to control shNT cells (Fig. 1D). PKCδ-depleted HEK293 cells (shδ193 and shδ203), also show more rapid resolution of IR-induced DNA damage as compared to the control shSCR cells (Fig. 1E).

Genomic instability can arise due to impaired DNA DSB repair (34). As micronuclei are a biomarker for DNA damage and chromosomal instability (35), we quantified micronuclei formation in human retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) cells stably integrated with pGFP or pGFP-tagged PKCδ (RPE-GFP or RPE-PKCδGFP cell lines, respectively). We observed a 10-fold increase in micronuclei formation in RPE-PKCδGFP cells compared to control RPE-GFP cells (Fig. 1F–G), indicating that increased expression of PKCδ is sufficient to cause genomic instability in immortalized, but non-transformed normal epithelial cells. We next interrogated the TCGA database to determine if differences in expression of PKCδ correlate with copy number variants (CNV) in cancer patients with Lung Adenocarcinoma (LUAD) or Head-Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma (HNSCC). Surprisingly, high PKCδ expression correlated with low CNV in both LUAD and HNSCC cancers (Supplementary Fig. S1A–B). Thus, it is likely that in these tumors, increased DNA instability is coupled with increased apoptosis, suggesting a tumor suppressive role for PKCδ.

PKCδ regulates NHEJ and HR mediated DNA DSB repair.

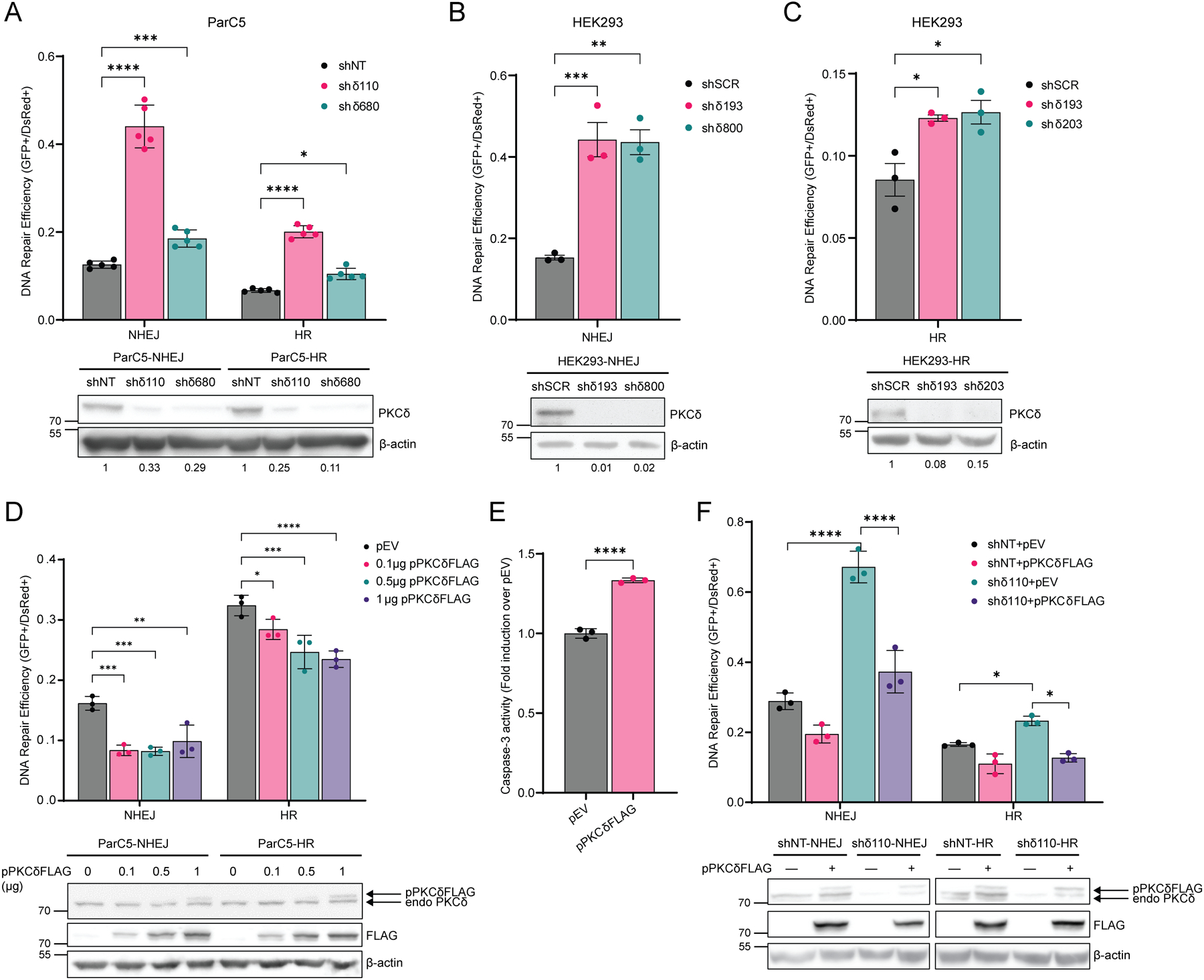

To determine if PKCδ regulates NHEJ and HR repair pathways we generated ParC5 reporter cell lines (shNT, shδ110 and shδ680) and HEK293 reporter cell lines (shSCR, shδ193, shδ203 and shδ800) containing either chromosomally integrated GFP-based NHEJ or HR reporter constructs (19,20). In this assay, successful NHEJ or HR repair results in GFP fluorescence. Each reporter line was co-transfected with pI-SceI to induce DSB and pDsRed to normalize for the differences in transfection efficiency between cell lines. All PKCδ-depleted cell lines showed an increase in both NHEJ and HR mediated DNA repair (Fig. 2A–C). In ParC5 NHEJ reporter cells, repair increased 3.5- and 1.5-fold in shδ110 and shδ680, respectively, compared to the shNT control (Fig. 2A). Similarly, in two PKCδ-depleted HEK293 NHEJ reporter cell lines (shδ193, shδ800), repair increased over 3-fold compared to the shSCR control (Fig. 2B). Depletion of PKCδ also increased HR repair in all four PKCδ-depleted cell lines, although in general the increase in HR mediated repair was of a lower magnitude than the increase in NHEJ mediated DNA repair for both ParC5 and HEK293 cells (Fig. 2A–C).

Fig. 2. PKCδ regulates NHEJ and HR mediated DSB repair.

(A to C) DNA repair was analyzed in (A) ParC5 shNT, shδ110, and shδ680 cells containing stably integrated NHEJ or HR reporters, (B) HEK293 shSCR, shδ193, and shδ800 cells containing NHEJ reporters, or (C) HEK293 shSCR, shδ193, and shδ203 cells containing HR reporters. Cells were co-transfected with plasmids expressing pI-SceI to induce DSBs and pDsRed to normalize transfection efficiency. Reporter cells were allowed to grow for 72 hrs post-electroporation and repair was quantified by flow cytometry. Western blots under each figure show the level of PKCδ depletion with the corresponding densitometry of PKCδ normalized to β-actin. (D) ParC5 NHEJ or HR reporter cells were transfected with 1 μg pEV (black bars) or increasing amount of pPKCδFLAG, and DNA repair was assayed. (E) ParC5-NHEJ cells transfected with 0.1 ug of PKCδFLAG for 72 hrs were collected, lysed, and assayed for caspase-3 activities. (F) ParC5 shNT and shδ110 reporter cells were co-transfected with plasmids expressing pI-SceI, pDsRed, and pEV or pPKCδFLAG and DNA repair was analyzed. Western blots below D and F show the level of FLAG-PKCδ expression. Each data point represents an average from three independent biological replicates. Data is shown as mean ± SEM. Statistics represent two-way ANOVA or one-way ANOVA for (B) and (C), followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparisons within NHEJ or HR reporter cell lines to their corresponding shNT, shSCR, or pEV control, and unpaired t-test for (E). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001.

We show that in the absence of PKCδ, NHEJ and HR mediated DNA repair is increased, indicating that PKCδ is a negative regulator of DSB repair. To explore this further, we expressed increasing amounts of FLAG-tagged PKCδ (pPKCδFLAG) in ParC5-NHEJ and ParC5-HR reporter cells. Expression of pPKCδFLAG decreased both NHEJ and HR mediated DNA repair, albeit NHEJ reporter cells appeared to be more sensitive (Fig. 2D). Decreased repair correlates with an increase in apoptosis in NHEJ reporter cells (Fig. 2E). Similarly, transfection of pPKCδFLAG reversed the increase in NHEJ and HR repair seen in shδ110 reporter cells (Fig. 2F). Together our data indicates that PKCδ regulates DNA damage-induced apoptosis at least in part through regulation of DNA repair.

Loss of PKCδ “primes” cells for DSB repair.

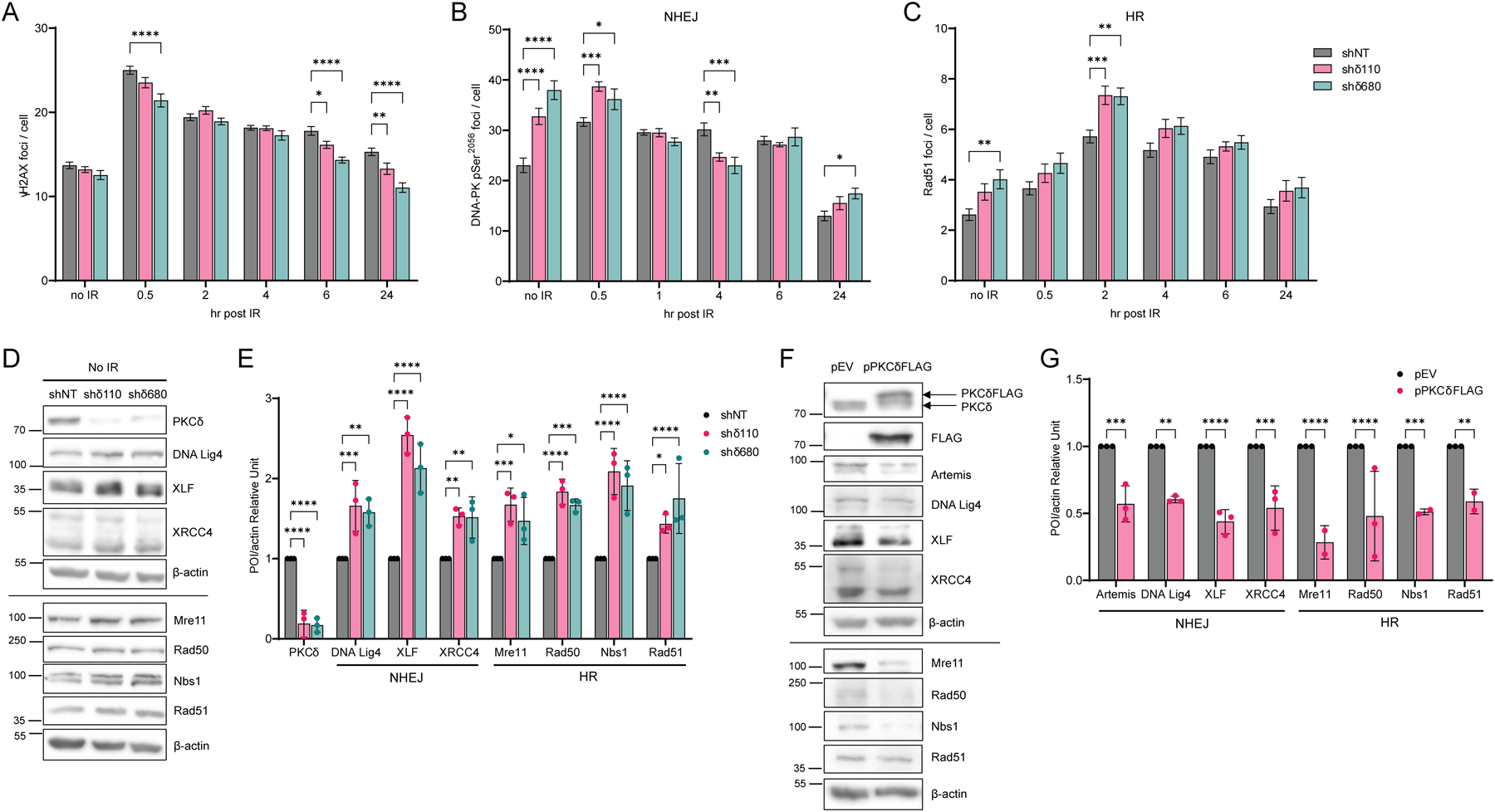

A crucial mechanism for cells to maintain genomic integrity in the face of endogenous insults and exogenous damaging agents is through activation of DDR, which senses DNA damage and promotes repair (34). One of the earliest events in the cellular response to DSBs is the phosphorylation of the histone protein H2AX at Ser139 (γH2AX), which accumulates at sites of DSBs to recruit and localize DNA repair proteins (36). To examine the kinetics of γH2AX foci formation, foci were quantified in ParC5 shNT, shδ110 and shδ680 cells following exposure to IR. γH2AX foci increased in all cell lines at 0.5 hr, however PKCδ-depleted shδ110 and shδ680 cells had significantly fewer foci compared to shNT cells (Fig. 3A). Moreover, γH2AX foci resolved sooner in shδ110 and shδ680 cells (Fig. 3A, 6 hr and 24 hr), indicating faster DNA repair. To investigate the kinetics of NHEJ and HR repair directly, we assayed DNA repair foci using antibodies to specific repair complex proteins. Surprisingly, in PKCδ-depleted cells, both NHEJ (DNA-PK pSer2056) and HR (Rad51) foci (Fig. 3B–C) are increased basally, which correlates with the reduction in DNA damage previously observed (Fig. 1D). Following IR, PKCδ-depleted cells have more DNA-PK pSer2056 foci at 0.5 hr, but these resolve faster than in shNT cells (Fig. 3B, 0.5 hr versus 4 hr). Similarly, there were more Rad51 foci at 2 hr in PKCδ-depleted cells compared to shNT cells (Fig. 3C). These data suggest that in the absence of PKCδ, cells are primed to repair DSBs.

Fig. 3. Loss of PKCδ enhances formation of DNA repair foci and alters expression of NHEJ and HR repair proteins.

(A to C) ParC5 shNT, shδ110, and shδ680 cells were plated on coverslips and exposed to 1 Gy IR. Cells were harvested at indicated times post IR by permeabilization, fixation, and stained for foci, (A) γH2AX, (B) DNA-PK pSer2056, and (C) Rad51 foci (legend in C is for A to C). An average of three independent experiments is shown. Error bars show ± SEM. (D) Western blots of ParC5 shNT, shδ110, and shδ680 cells immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. (E) Densitometry of Western blots shown in D; expression of each protein of interest (POI) was normalized to the actin control. (F) ParC5 cells were transiently transfected with empty vector (pEV) or pPKCδFLAG for 48 hrs. Cells were then collected and immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies (first and second blots were probed with antibodies against PKCδ and FLAG-tag respectively). Note that panels D and F show two different experiments separated by lines, each normalized to their own β-actin loading control. (G) Densitometry of Western blots shown in F; expression of each POI was normalized to the actin control. Data are from three independent biological replicates and shown as mean ± SEM. Statistics represent two-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons and Sidak’s multiple comparisons for (G) to the corresponding control (black bars). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001.

To investigate the mechanism(s) underlying priming of DSB repair, we looked at expression of a subset of NHEJ and HR repair proteins. All NHEJ and HR repair proteins assayed increased in shδ110 and shδ680 cells compared to shNT cells, ranging from a 1.4-fold (Rad51) to a 2.5-fold increase (DNA Lig4) (Fig. 3D–E). Similar results were seen when mRNA abundance was quantified by qRT-PCR (Supplementary Fig. S2A). On the contrary, when pPKCδFLAG was overexpressed in ParC5 cells, we observed a dramatic decrease in expression of NHEJ and HR repair proteins (Fig. 3F–G). The mRNA levels of these proteins were similarly decreased (Supplementary Fig. S2B). Thus, changes in the expression of NHEJ and HR repair proteins likely contribute to priming of DSB repair pathways by PKCδ.

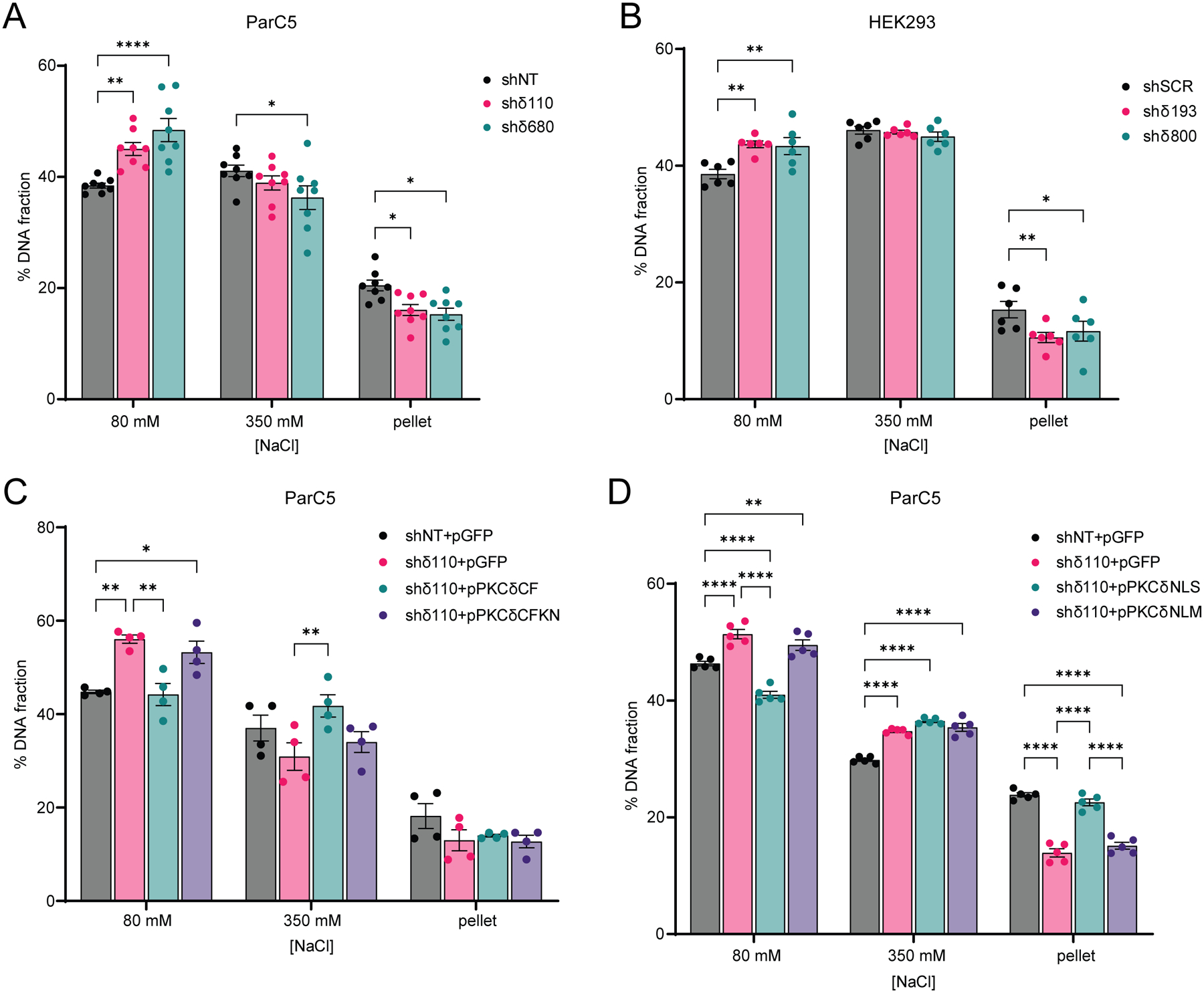

PKCδ regulates global chromatin structure.

Both NHEJ and HR repair require a dynamic switch from condensed to relaxed chromatin to provide accessibility of DNA repair proteins to the site of DSBs. To determine if PKCδ affects global chromatin structure, we utilized a micrococcal nuclease (MNase)-digested chromatin assay (24,37). PKCδ-depleted ParC5 and HEK293 cells showed increased elution of DNA at a lower molarity of NaCl compared to their respective control shRNA cell lines (Fig. 4A–B). The relative percent of DNA eluted at 80 mM NaCl increased by 1.2 and 1.3-fold in shδ110 and shδ680 cells, respectively, compared to shNT control cells (Fig. 4A), suggesting more accessible chromatin in the absence of PKCδ. Similar results were seen in PKCδ-depleted HEK293 cells (Fig. 4B). To verify that PKCδ kinase activity and nuclear localization are required for changes in chromatin structure, ParC5 shδ110 cells were transiently transfected with pPKCδCF or pPKCδCFKN (Fig. 4C), or pPKCδNLS or pPKCδNLM (Fig. 4D) and MNase sensitivity was compared to shNT or shδ110 cells transfected with pGFP alone. As expected, in shδ110+pGFP transfected cells more DNA was eluted in the 80 mM NaCl fraction compared to the shNT+pGFP (Fig. 4C–D), consistent with what we observed in Fig. 4A and 4B. However, expression of pPKCδCF in shδ110 cells significantly reduced the percent of DNA eluted in the 80 mM NaCl fraction when compared to the shδ110+GFP (Fig. 4C), while no change in MNase sensitivity was seen with expression of the catalytically negative pPKCδCFKN (Fig. 4C), verifying that the kinase activity of PKCδ is required to induce chromatin condensation. Similarly, expression of pPKCδNLS, but not pPKCδNLM, reduced elution of DNA at 80 mM compared to shδ110+pGFP transfected cells (Fig. 4D), verifying that the nuclear localization of PKCδ is required to induce chromatin condensation. These data implicate PKCδ as a regulator of global chromatin structure, consistent with its ability to regulate DNA repair pathways. Furthermore, they suggest that depletion of PKCδ likely primes cells for DNA repair by increasing the accessibility of repair proteins to sites of DSBs.

Fig. 4. PKCδ alters global chromatin structure.

(A and B) MNase assay was performed on (A) ParC5 shNT, shδ110, and shδ680 cells, and on (B) HEK293 shSCR, shδ193, and shδ800 cells. (C and D) ParC5 shNT cells were transfected with pGFP only, while shδ110 cells were transfected with (C) pGFP, pPKCδCF, or pPKCδCFKN, or (D) pGFP, pPKCδNLS, or pPKCδNLM for 24 hrs prior to harvesting. Percentage of DNA in each [NaCl] fraction was assayed as described in Materials and Methods. Shown is data (mean ± SEM) from at least three independent biological replicates. Statistics represent two-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparisons within each fraction to their corresponding shNT or shSCR control for (A) and (B), or two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons within each fraction for (C) and (D). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001.

Depletion of PKCδ is associated with increased H3K36 methylation.

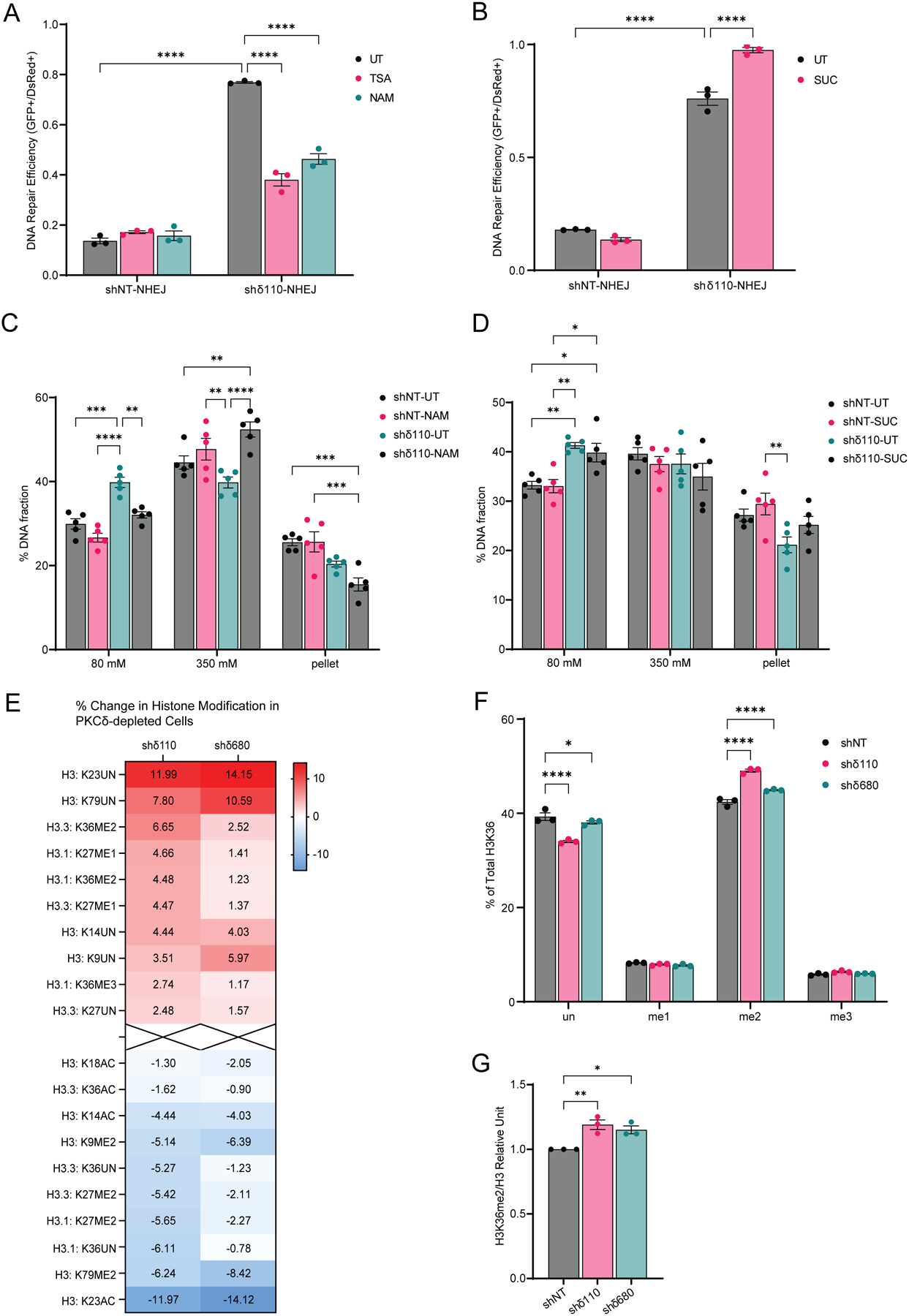

Methylation and acetylation of histones can regulate the efficiency of DNA repair by controlling the accessibility of damaged DNA to repair factors. To investigate the contribution of chromatin regulating enzymes and histone PTMs to changes in chromatin accessibility in PKCδ-depleted cells, we first used general inhibitors that target a subset of these enzymes. These include Trichostatin A (TSA) to inhibit Class I and II histone deacetylases (HDACs), nicotinamide (NAM) to inhibit Class III HDACs (SIRT1–7), and succinate (SUC) to inhibit Jumonji demethylases (KDMs). No changes in NHEJ repair efficiency were observed when shNT cells were treated with either TSA or NAM (Fig. 5A). However, treatment of shδ110 cells with TSA or NAM resulted in a 50% decrease in NHEJ repair compared to the untreated (UT) shδ110 cells (Fig. 5A), implying that Class I, II or III HDACs are involved in promoting DNA repair in PKCδ-depleted cells. Similarly, SUC had no effect on NHEJ repair in shNT cells, but further increased repair in shδ110 cells compared to UT cells (Fig. 5B), implicating KDMs as inhibitors of NHEJ in shδ110 cells. This suggests that increased repair in shδ110 cells may require decreased histone acetylation and increased methylation. We next looked at the effect of these inhibitors on chromatin structure using the MNase assay. NAM reversed the chromatin relaxation seen in shδ110 cells, as evidenced by a reduction in DNA elution at 80 mM NaCl and an increase in DNA elution at 350 mM NaCl (Fig. 5C). However, SUC did not increase DNA elution at 80 mM NaCl beyond that seen in shδ110 cells (Fig. 5D).

Fig. 5. Depletion of PKCδ promotes DNA repair and chromatin relaxation and increases H3K36me2.

(A and B) DNA repair was analyzed in ParC5 shNT-NHEJ and shδ110-NHEJ reporter cells pretreated with (A) 100 nM trichostatin A (TSA) or 5 mM nicotinamide (NAM), or (B) 5 mM succinate (SUC) for 24 hrs and then co-transfected with plasmids expressing pI-SceI to induce DSBs and pDsRed to normalize transfection efficiency. NHEJ and HR reporter cells were allowed to grow for 72 hrs post-transfection and repair was quantified. (C and D) MNase assay was performed on ParC5 shNT and shδ110 cells pretreated with (C) 5 mM NAM or (D) 5 mM SUC for 48 hrs before harvesting. Percentage of DNA in each [NaCl] fraction was assayed. Shown is data (mean ± SEM) from at least three independent biological replicates. (E) Histone modifications of ParC5 shNT, shδ110, and shδ680 were analyzed by mass spectrometry (Northwestern University). Heat map shows the percent change of PTMs on H3 in each modification in shδ110 and shδ680 cells relative to shNT (top and bottom 10 shown). (F) Profile of H3K36 methylation in shNT, shδ110, and shδ680 cells. (G) Densitometry of H3K36me2 normalized to total H3. Shown is data (mean ± SEM) from three independent biological replicates. Statistics represent two-way ANOVA followed by Sidak’s for (A), Tukey’s for (B to D), and Dunnett’s multiple comparisons for (F), and one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparisons for (G). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001.

As PKCδ regulation of chromatin structure and DNA repair could be mediated by epigenetic modifications, we profiled histone modifications in ParC5 shNT and PKCδ-depleted shδ110 and shδ680 cells using the Epiproteomic Histone Modification Panel (EHMP) in collaboration with the Northwestern Proteomics Core Facility. Acid-extracted histones were identified by mass spectrometry, and the percentage change in each histone PTM between the shδ110, shδ680 cells and shNT cells were calculated and plotted in the heatmap (Fig. 5E, top and bottom 10 of PTMs on H3 are shown). Full EHMP results are available in Supplementary Materials (Supplementary data file S1). As predicted by our inhibitor studies (Fig. 5A–D), depletion of PKCδ correlated with a reduction in histone acetylation (Fig. 5E, H3K23, H3K14, H3K36 and H3K18). Changes in histone methylation were more varied and included a decrease in H3K79me2, H3K27me2, and H3K9me2, and an increase in H3K27me1 (Fig. 5E). However, the largest increase in histone methylation observed was at H3K36me2 (Fig. 5E–F). Of the histone marks modified in a PKCδ-dependent manner, H3K36me2, H3K79me2 and H3K14ac are associated with increased DNA repair (38–40). As H3K79me2 and H3K14ac are reduced in PKCδ-depleted cells, they are unlikely to be involved in the phenotypes we have described. Therefore, we focused on the H3K36me2 mark as a mechanism to explain increased DNA repair in PKCδ-depleted cells. We confirmed enrichment of H3K36me2 in PKCδ-depleted cells by immunoblot of acid-extracted histones with an antibody specific to dimethyl H3K36. In agreement with the EHMP results, H3K36me2 were increased up to 15% in shδ110 and shδ680 cells (Fig. 5G).

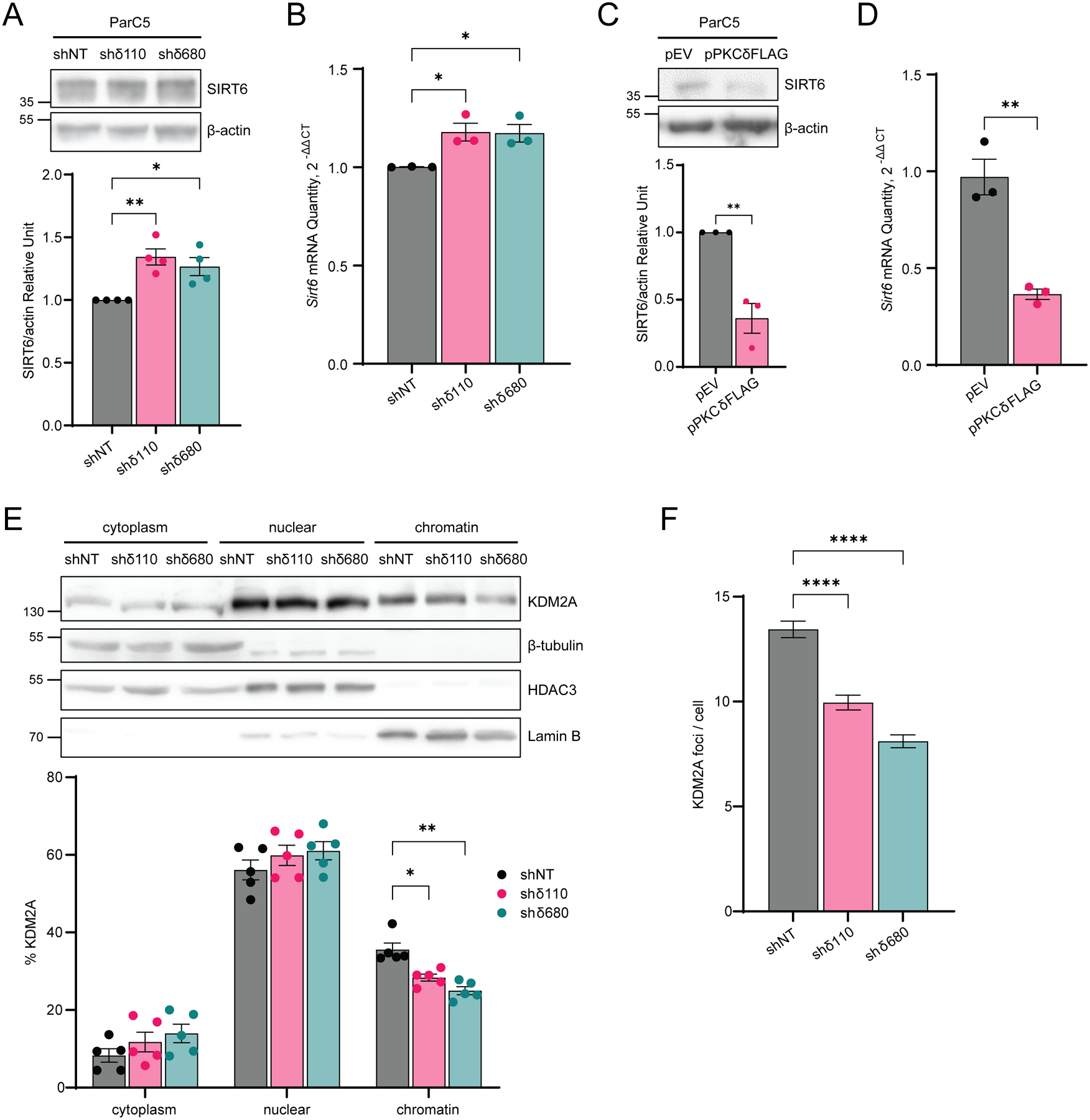

PKCδ regulates chromatin, DSB repair and apoptosis through SIRT6.

SIRT6 is an early DSB sensor that facilitates opening of chromatin to enable recruitment of DNA repair factors to sites of damage (12). Rezazadeh et al. have shown that SIRT6 can also increase H3K36me2 at DNA damage sites by displacement of KDM2A from chromatin through a mechanism dependent on SIRT6 (14). We examined SIRT6 protein expression and mRNA levels in the context of PKCδ depletion and PKCδ overexpression. SIRT6 protein was increased in both shδ110 and shδ680 cells compared to the shNT (Fig. 6A), with similar changes seen in SIRT6 mRNA abundance (Fig. 6B). Conversely, expression of pPKCδFLAG resulted in a dramatic decrease of both SIRT6 protein and mRNA (Fig. 6C–D). We then asked if the increase in SIRT6 in PKCδ-depleted cells was associated with displacement of KDM2A from chromatin. In the absence of PKCδ, less KDM2A was associated with chromatin in PKCδ-depleted shδ110 and shδ680 cells compared to shNT cells (Fig. 6E). Quantification of KDM2A foci revealed a similar decrease in PKCδ-depleted shδ110 and shδ680 cells compared to shNT cells (Fig. 6F). The demonstration that depletion of PKCδ enriches H3K36me2 and reduces KDM2A on chromatin suggests that PKCδ may prime cells for DSB repair through SIRT6.

Fig. 6. SIRT6 regulates KDM2A ribosylation in PKCδ-depleted cell.

(A) Top: Whole cell lysates of ParC5 shNT, shδ110, and shδ680 cells were immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. Bottom: Densitometry of SIRT6 expression normalized to β-actin. (B) Relative expression of SIRT6 mRNA in ParC5 shNT, shδ110, and shδ680 cells was assayed by qRT-PCR. (C) Top: ParC5 cells transfected with pEV or pPKCδFLAG were analyzed for SIRT6 expression by immunoblot analysis. Bottom: Densitometry of SIRT6 expression normalized to β-actin. Expression of PKCδFLAG can be seen in Figure 3F. (D) Relative expression of SIRT6 mRNA in ParC5 overexpressing either pEV or pPKCδFLAG cells was assayed by qRT-PCR. Shown is data from at least three independent biological replicates. Data is shown as mean ± SEM. (E) Top: ParC5 shNT, shδ110, and shδ680 cells were fractionated into cytoplasm, nuclear and chromatin fractions, and each fraction was immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. Bottom: Percentage of KDM2A in cytoplasm, nuclear, and chromatin were calculated. (F) ParC5 shNT, shδ110, and shδ680 cells were plated on coverslips and grown to 80% confluency. Cells were permeabilized, fixed, and stained for KDM2A foci. The data shown is from a representative experiment that were repeated three times. Error bars show ± SEM. Statistics represent one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparisons for (A), (B) and (F), unpaired t-test for (C) and (D), and two-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparisons for (E). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001.

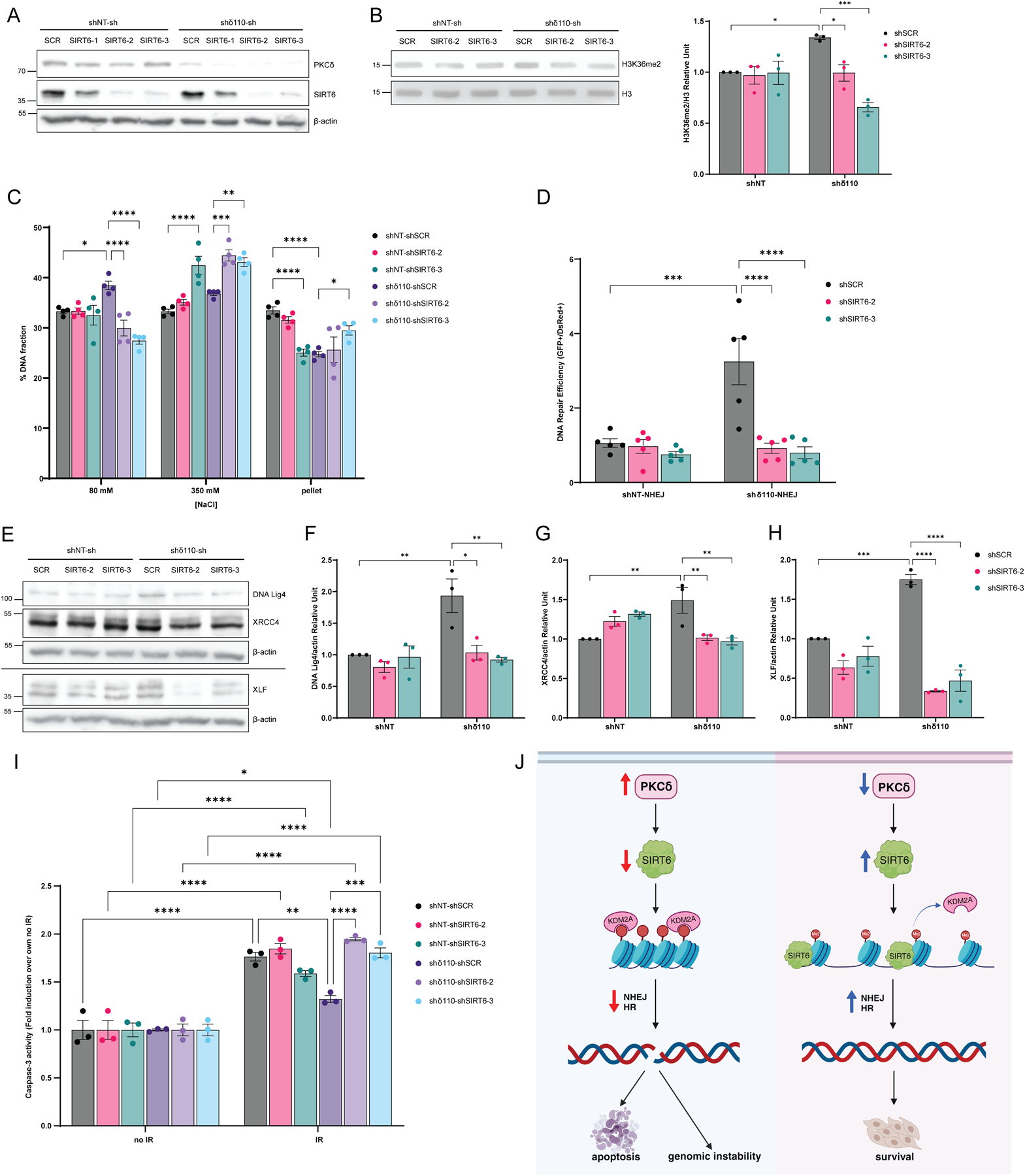

To further investigate the role of SIRT6 in PKCδ-dependent regulation of DNA repair and apoptosis, we depleted SIRT6 in ParC5 shNT and shδ110 NHEJ reporter cells using four unique shRNAs (Fig. 7A). shSIRT6–2 and shSIRT6–3 showed approximately 90% reduction of SIRT6 protein levels, and thus these cell lines were used in the remainder of the experiments. We hypothesized that SIRT6 is required to facilitate displacement of chromatin KDM2A and enrich H3K36me2 in PKCδ-depleted cells. When SIRT6 was depleted in shδ110 cells, the abundance of H3K36me2 on chromatin was reduced compared to the shδ110-shSCR control, while little to no change in H3K36me2 was observed in the shNT cells (Fig. 7B). To determine if the KDM2A/H3K36me2 switch is associated with changes in chromatin structure, we performed an MNase assay. With depletion of SIRT6, the more relaxed chromatin structure seen in the shδ110 cells was reversed, while SIRT6 depletion had no effect on MNase sensitivity in shNT control cells (Fig. 7C). We next examined the ability of SIRT6-depleted cells to repair DNA DSBs. As expected, NHEJ-mediated repair was increased dramatically in shδ110 cells (Fig.7D). Remarkably, both shRNAs targeting SIRT6 completely reversed the increase in NHEJ repair in PKCδ-depleted cells (Fig. 7D). Likewise, depletion of SIRT6 reversed the increased expression of NHEJ repair proteins (Fig. 7E–H) we observed in PKCδ-depleted cells (Fig. 3D–G). DNA Lig4, XLF, and XRCC4 expressions were significantly reduced in the shδ110-shSIRT6–2/3 cells compared to shδ110 cells (Fig. 7E–H).

Fig. 7. SIRT6 functions downstream of PKCδ to regulate DNA repair and apoptosis.

(A) ParC5 shNT and shδ110 NHEJ reporter cells were generated that stably express shSCR, shSIRT6–1, shSIRT6–2, or shSIRT6–3. Lysates were immunoblotted for the indicated proteins. (B) Top: Histone fractions from ParC5 shNT/shδ110-shSCR/shSIRT6–2/shSIRT6–3 cells were acid-extracted and immunoblotted for H3K36me2 and total H3. Bottom: Densitometry of H3K36me2 normalized to total H3. (C) MNase assay was performed on ParC5 shNT/shδ110-shSCR/shSIRT6–2/shSIRT6–3 cells. Percentage of DNA in each [NaCl] fraction was assayed as described in Materials and Methods. (D) DNA repair was analyzed in ParC5 shNT/shδ110-shSCR/shSIRT6–2/shSIRT6–3 NHEJ reporter cells and quantified as described in Materials and Methods. (E to H) Lysates from ParC5 shNT/shδ110-shSCR/shSIRT6–2/shSIRT6–3 cells were immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. Densitometry of DNA Lig4 (F), XRCC4 (G), and XLF (H) normalized to their corresponding β-actin control from the Western blots shown in (E). Note that panel E shows two different experiments separated by a line, each normalized to their own β-actin loading control. (I) ParC5 shNT/shδ110-shSCR/shSIRT6–2/shSIRT6–3 cells were IR at 10 Gy and allowed to recover for 48 hrs. Cells were harvested and caspase-3 activity was assayed. Shown is the fold induction of caspase-3 activities in each cell line over their own corresponding no IR controls. Shown is data from at least three independent biological replicates. Data is shown as mean ± SEM. Statistics represent two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001. (J) Model of PKCδ-dependent apoptosis. Left, under basal conditions PKCδ, through SIRT6, promotes KDM2A demethylation of H3K36me2 on chromatin, resulting in chromatin compaction, suppression of NHEJ and HR repair, and genomic instability and apoptosis (Fig. 7J, left). Contrarily, when PKCδ is depleted, SIRT6 expression is increased, leading to KDM2A disassociation from chromatin, an increase in H3K36me2, chromatin relaxation, and enhanced NHEJ and HR repair and cell survival (Fig. 7J, right). Created with BioRender.com

Finally, to determine if SIRT6 is required for radioprotection in PKCδ-depleted cells, caspase-3 activity was assayed in SIRT6-depleted cells following IR. As expected, PKCδ-depleted shδ110 cells showed protection against IR compared to shNT cells (Fig. 7I, gray bar vs dark purple bar), however, this protection was completely reversed when SIRT6 was depleted (shδ110-shSIRT6–2 and shδ110-shSIRT6–3) indicating that SIRT6 is required for radioprotection (Fig. 7I).

DISCUSSION

PKCδ regulates many cellular functions including growth factor signaling at the plasma membrane and apoptosis in the nucleus (41). We have previously shown that inhibition of PKCδ provides radioprotection in vitro and in vivo (6–11,18,29,33). Our current studies define a novel mechanism for control of apoptosis by PKCδ that is dependent on reciprocal regulation of SIRT6. We propose that PKCδ, through SIRT6, promotes KDM2A demethylation of H3K36me2 on chromatin, resulting in chromatin compaction, suppression of NHEJ and HR repair, and genomic instability and apoptosis (Fig. 7J, left). Contrarily, when PKCδ is depleted, SIRT6 expression is increased, leading to KDM2A disassociation from chromatin, an increase in H3K36me2, and chromatin relaxation, enhanced NHEJ and HR repair and cell survival (Fig. 7J, right).

Previous studies from our lab show that translocation of PKCδ to the nucleus in response to DNA-damaging agents is both necessary and sufficient to induce apoptosis (7). Here we show that chromatin changes mediated by PKCδ require both its nuclear localization and kinase function. Nuclear translocation requires progressive tyrosine phosphorylation at Tyr155 and Tyr64 in the regulatory domain of PKCδ, with the initial phosphorylation event at Tyr155 mediated by the DNA damage-induced tyrosine kinase, c-Abl (8,9). This links nuclear translocation of PKCδ to the DNA damage response, and supports previous studies from our lab that show the steady state level of nuclear PKCδ determines responsiveness to DNA damaging agents in a panel of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cells (42). Thus, the cytoplasmic:nuclear partitioning of PKCδ may underlie radiosensitivity of both tumors and adjacent normal tissues.

We propose that depletion of PKCδ “primes” cells for DNA repair. Depletion of PKCδ increases NHEJ and HR mediated repair. We have previously shown that the tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs), imatinib and dasatinib, which inhibit tyrosine phosphorylation and nuclear translocation of PKCδ, also increase expression of DNA repair proteins and enhance NHEJ and HR repair of DSBs (10,23). Priming in the case of PKCδ depletion is transcriptional or post-transcriptional, as overexpression or depletion of PKCδ decreases or increases mRNA and protein expression of NHEJ and HR repair factors, respectively. With both depletion of PKCδ and TKIs pretreatment, NHEJ and HR foci form more rapidly after IR (10,18,23). Thus, depletion of PKCδ may reset the homeostatic environment to respond more rapidly and robustly to DNA damage. Other studies support a role for PKCδ regulation of cell cycle arrest, specifically in mediating G1 arrest through induction of p21 (43), in S phase arrest (44), and in the maintenance of G2/M DNA damage checkpoint (45). It seems likely that regulation of checkpoint activation is linked to PKCδ via DNA repair, however we have not observed consistent differences in the cell cycle arrest of PKCδ-depleted ParC5 cells basally or after IR (Reyland et al., unpublished data).

Our data indicates a role for PKCδ upstream of DSBs repair pathways. Like transcription and replication, the DNA repair machinery require access to genomic DNA packaged in chromatin. Thus, the ability to dynamically change chromatin structure is essential for the DDR, DNA repair and maintenance of genome integrity. Typically, more open chromatin leads to enhanced DDR and DNA repair, while more compact chromatin inhibits DNA repair (34). Our studies demonstrate that in the absence of PKCδ, chromatin is more sensitive to MNase, indicating a more open conformation. Chromatin remodeling can be achieved by histone PTMs and chromatin remodeling enzymes (34). It is widely known that acetylation and ubiquitylation promote an open chromatin structure, however, the role of methylation in DDR and DNA repair is still debated. While our epiproteomic histone modification analysis identified changes in both acetylation and methylation with PKCδ depletion, most of the changes have not been previously associated with DNA repair, or the change is in the wrong direction. For example, acetylation of H3 on residues Lys23 and Lys14, and dimethylation on Lys79 is decreased. H3K23ac coexists with H3K14ac and is associated with active gene transcription (46), however a role in DDR or DNA repair has not been described. H3K79me2 plays a key role in DDR in yeast, and is linked to active transcription, genomic stability and HR repair (40). Since H3K79me2 is reduced in the PKCδ-depleted cells, this histone modification is unlikely to be involved in the phenotypes we show in PKCδ-depleted cells. Conversely, H3K36me2 is typically associated with active euchromatic regions, is induced upon IR, and accumulates around DSBs (38).

Accumulation of H3K36me2 stimulates DSB repair through increased recruitment of the DNA damage sensing proteins Ku70 and Nbs1 (38). H3K36me2 is mainly demethylated by KDM2A, a Jumonji demethylase that has been shown to regulate DNA repair through its chromatin-binding capacity; when the binding capacity of KDM2A to chromatin is disrupted, DNA repair and cell survival are enhanced (47). Recently, KDM2A has been identified as a substrate of SIRT6, and SIRT6-dependent ribosylation of KDM2A was shown to displace KDM2A from chromatin, increasing H3K36me2 and enhancing NHEJ (14). SIRT6 is a NAD+-dependent chromatin regulating enzyme that belongs to the Sirtuin family. While it is classified as Class III HDAC catalyzing the deacetylation of Lys9, Lys18, and Lys56 of H3, it has a wide range of substrates other than histones, such as Lys and Arg residues of chromatin regulating enzymes and DNA repair proteins, in which SIRT6 catalyzes the mono-ADP ribosylation of these residues (48). We show that PKCδ negatively regulates SIRT6, and that SIRT6 is required for suppression of apoptosis in PKCδ-depleted cells. Mechanistically, SIRT6 is required for all aspects of the radioprotection phenotype we describe in PKCδ-depleted cells, including chromatin relaxation, dissociation of KDM2A from chromatin, increased H3K36me2 and priming of DNA repair. Ongoing studies in our lab are exploring whether the ribosylation of KDM2A by SIRT6 is PKCδ dependent.

While SIRT6 has been identified as one of the earliest DNA damage sensors recruited to DSBs to open chromatin and initiate repair (12), little is known about how SIRT6 is regulated in context of DDR and DNA repair. Proteomic analysis has identified conserved residues on SIRT6 that are phosphorylated (Ser10, Thr294, Ser303, Ser330, and Ser338) (49). There are no PKCδ-specific consensus phosphorylation sites in SIRT6, suggesting that PKCδ regulation of SIRT6 is indirect or not mediated by PKCδ kinase activity. In response to oxidative stress, SIRT6 is phosphorylated by c-jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) on Ser10 to stimulate DNA repair by recruiting PARP1 to DSBs and through mono-ADP ribosylation of PARP1 on Lys521 (50). While PKCδ is an upstream effector JNK (29), it represses SIRT6, thus it is unlikely that the increased abundance of SIRT6 in PKCδ-depleted cells is through the activation of JNK. SIRT6 protein stability is regulated through phosphorylation of SIRT6 on Ser338 by Akt which allows its ubiquitination by MDM2, promoting SIRT6 degradation (51). While we have not examined degradation of SIRT6 protein, in our studies PKCδ reciprocally regulates the abundance of SIRT6 mRNA, suggesting that PKCδ may be a negative regulator of SIRT6 transcription.

We show that the catalytic activity of PKCδ is required and sufficient to induce apoptosis and increase DNA damage, however substrate(s) of PKCδ in response to DNA damage are still unknown. Phosphorylation of histone H3 on Ser10 is dynamically regulated during the cell cycle, and is essential for mitosis where it regulates chromatin condensation (52). Park et al. have reported that PKCδ phosphorylation of H3 on Ser10 in vitro and in HeLa and Jurkat cells is associated with apoptosis and nuclear condensation, however the significance of these findings to DNA repair is not clear as the authors did not examine chromatin associated histones (52). We have previously identified MSK1, a chromatin-modifying kinase, as a downstream effector of PKCδ that is required for apoptosis (31). MSK1/2 phosphorylates H3 histones at multiple sites, including Ser10 and Ser28 (53). This raises the possibility that chromatin modification by MSK1 could be a component of the DNA repair program regulated by PKCδ.

Our studies provide a mechanistic understanding of how PKCδ regulates DNA damage and cell death. These functions may be unique to PKCδ, as similar roles for other PKC isoforms have not been reported. Our studies have implications for other processes associated with altered DNA repair, including cancer and aging. For example, a reduction in H3K36me2, as well as H3K36M mutations which prevent H3K36 methylation, are associated with brain and bone cancers (54). Therefore, the ability of PKCδ to decrease H3K36me2 may explain in part its role as a tumor promoter in mouse models of cancer (11). While little is known regarding PKCδ and aging, PKCδ has been implicated in neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease (11). Many studies link SIRT6, DNA repair and aging. For example, the Gorbunova group has shown that long-lived species have higher SIRT6 activity and more robust DNA repair activity, suggesting that these activities coevolved (55). Further, mice overexpressing Sirt6 have a longer lifespan, while mice lacking Sirt6 display increased genomic instability and a degenerative aging-like phenotype (56). We similarly show that overexpression of PKCδ decreases SIRT6 expression and increases genomic instability. Taken together, our findings support further investigation of SIRT6 as a therapeutic target for radioprotection and of PKCδ as a possible target for aging.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary data file S1. Results of mass spectrometry histone profiling of shNT, shδ110 and shδ680 cells. Spreadsheet includes average percent of each modification, standard deviation, and coefficient of variance (CV).

Supplementary Fig. S1. Correlation of copy number variants (CNV) and PKCδ expression in LUAD and HNSCC.

Supplementary Fig. S2. PKCδ regulates expression of genes required for DNA repair.

TCGA Analysis

Supplementary Table S1. List of plasmids used in this study.

Supplementary Table S2. List of primers used for qRT-PCR.

IMPLICATIONS:

PKCδ controls sensitivity to irradiation by regulating DNA repair.

Acknowledgments

Proteomics services were performed by the Northwestern Proteomics Core Facility, generously supported by NCI CCSG P30 CA060553 awarded to the Robert H Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center, instrumentation award (S10OD025194) from NIH Office of Director, and the National Resource for Translational and Developmental Proteomics supported by P41 GM108569. The TCGA results published here are in whole based upon data generated by the TCGA research Network: https://www.cancer.gov/tcga.

Funding:

NIH/NIDCR DE015648 and DE024309 (MER)

NIH T32CA190216 and F32DE029116 (TA)

NIH/NIGMS 1R35GM128720-01 (JCB)

NIH/NCI P30CA046934 University of Colorado Cancer Center support grant

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Kumagai T, Rahman F, Smith AM. The Microbiome and Radiation Induced-Bowel Injury: Evidence for Potential Mechanistic Role in Disease Pathogenesis. Nutrients 2018;10(10) doi 10.3390/nu10101405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Costa S, Reagan MR. Therapeutic Irradiation: Consequences for Bone and Bone Marrow Adipose Tissue. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2019;10:587 doi 10.3389/fendo.2019.00587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J Clin 2022;72(1):7–33 doi 10.3322/caac.21708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Santivasi WL, Xia F. Ionizing radiation-induced DNA damage, response, and repair. Antioxid Redox Signal 2014;21(2):251–9 doi 10.1089/ars.2013.5668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Van HT, Santos MA. Histone modifications and the DNA double-strand break response. Cell Cycle 2018;17(21–22):2399–410 doi 10.1080/15384101.2018.1542899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Humphries MJ, Limesand KH, Schneider JC, Nakayama KI, Anderson SM, Reyland ME. Suppression of apoptosis in the protein kinase Cdelta null mouse in vivo. J Biol Chem 2006;281(14):9728–37 doi 10.1074/jbc.M507851200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.DeVries-Seimon TA, Ohm AM, Humphries MJ, Reyland ME. Induction of apoptosis is driven by nuclear retention of protein kinase C delta. J Biol Chem 2007;282(31):22307–14 doi 10.1074/jbc.M703661200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Humphries MJ, Ohm AM, Schaack J, Adwan TS, Reyland ME. Tyrosine phosphorylation regulates nuclear translocation of PKCdelta. Oncogene 2008;27(21):3045–53 doi 10.1038/sj.onc.1210967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adwan TS, Ohm AM, Jones DN, Humphries MJ, Reyland ME. Regulated binding of importin-alpha to protein kinase Cdelta in response to apoptotic signals facilitates nuclear import. J Biol Chem 2011;286(41):35716–24 doi 10.1074/jbc.M111.255950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wie SM, Adwan TS, DeGregori J, Anderson SM, Reyland ME. Inhibiting tyrosine phosphorylation of protein kinase Cdelta (PKCdelta) protects the salivary gland from radiation damage. J Biol Chem 2014;289(15):10900–8 doi 10.1074/jbc.M114.551366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Black JD, Affandi T, Black AR, Reyland ME. PKCalpha and PKCdelta: Friends and Rivals. J Biol Chem 2022;298(8):102194 doi 10.1016/j.jbc.2022.102194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Onn L, Portillo M, Ilic S, Cleitman G, Stein D, Kaluski S, et al. SIRT6 is a DNA double-strand break sensor. Elife 2020;9 doi 10.7554/eLife.51636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liszt G, Ford E, Kurtev M, Guarente L. Mouse Sir2 homolog SIRT6 is a nuclear ADP-ribosyltransferase. J Biol Chem 2005;280(22):21313–20 doi 10.1074/jbc.M413296200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rezazadeh S, Yang D, Biashad SA, Firsanov D, Takasugi M, Gilbert M, et al. SIRT6 mono-ADP ribosylates KDM2A to locally increase H3K36me2 at DNA damage sites to inhibit transcription and promote repair. Aging (Albany NY) 2020;12(12):11165–84 doi 10.18632/aging.103567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Quissell DO, Barzen KA, Redman RS, Camden JM, Turner JT. Development and characterization of SV40 immortalized rat parotid acinar cell lines. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim 1998;34(1):58–67 doi 10.1007/s11626-998-0054-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Black JC, Manning AL, Van Rechem C, Kim J, Ladd B, Cho J, et al. KDM4A lysine demethylase induces site-specific copy gain and rereplication of regions amplified in tumors. Cell 2013;154(3):541–55 doi 10.1016/j.cell.2013.06.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marek L, Ware KE, Fritzsche A, Hercule P, Helton WR, Smith JE, et al. Fibroblast growth factor (FGF) and FGF receptor-mediated autocrine signaling in non-small-cell lung cancer cells. Mol Pharmacol 2009;75(1):196–207 doi 10.1124/mol.108.049544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wie SM, Wellberg E, Karam SD, Reyland ME. Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors Protect the Salivary Gland from Radiation Damage by Inhibiting Activation of Protein Kinase Cdelta. Mol Cancer Ther 2017;16(9):1989–98 doi 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-17-0267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Seluanov A, Mittelman D, Pereira-Smith OM, Wilson JH, Gorbunova V. DNA end joining becomes less efficient and more error-prone during cellular senescence. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2004;101(20):7624–9 doi 10.1073/pnas.0400726101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mao Z, Seluanov A, Jiang Y, Gorbunova V. TRF2 is required for repair of nontelomeric DNA double-strand breaks by homologous recombination. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2007;104(32):13068–73 doi 10.1073/pnas.0702410104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ivashkevich AN, Martin OA, Smith AJ, Redon CE, Bonner WM, Martin RF, et al. gammaH2AX foci as a measure of DNA damage: a computational approach to automatic analysis. Mutat Res 2011;711(1–2):49–60 doi 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2010.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Seluanov A, Mao Z, Gorbunova V. Analysis of DNA double-strand break (DSB) repair in mammalian cells. J Vis Exp 2010(43) doi 10.3791/2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Affandi T, Ohm AM, Gaillard D, Haas A, Reyland ME. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors protect the salivary gland from radiation damage by increasing DNA double-strand break repair. J Biol Chem 2021;296:100401 doi 10.1016/j.jbc.2021.100401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Teves SS, Henikoff S. Salt fractionation of nucleosomes for genome-wide profiling. Methods Mol Biol 2012;833:421–32 doi 10.1007/978-1-61779-477-3_25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Garcia BA, Mollah S, Ueberheide BM, Busby SA, Muratore TL, Shabanowitz J, et al. Chemical derivatization of histones for facilitated analysis by mass spectrometry. Nat Protoc 2007;2(4):933–8 doi 10.1038/nprot.2007.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shechter D, Dormann HL, Allis CD, Hake SB. Extraction, purification and analysis of histones. Nat Protoc 2007;2(6):1445–57 doi 10.1038/nprot.2007.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schreiber E, Matthias P, Muller MM, Schaffner W. Rapid detection of octamer binding proteins with ‘mini-extracts’, prepared from a small number of cells. Nucleic Acids Res 1989;17(15):6419 doi 10.1093/nar/17.15.6419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Keszenman DJ, Kolodiuk L, Baulch JE. DNA damage in cells exhibiting radiation-induced genomic instability. Mutagenesis 2015;30(3):451–8 doi 10.1093/mutage/gev006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reyland ME, Anderson SM, Matassa AA, Barzen KA, Quissell DO. Protein kinase C delta is essential for etoposide-induced apoptosis in salivary gland acinar cells. J Biol Chem 1999;274(27):19115–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reyland ME, Barzen KA, Anderson SM, Quissell DO, Matassa AA. Activation of PKC is sufficient to induce an apoptotic program in salivary gland acinar cells. Cell Death Differ 2000;7(12):1200–9 doi 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ohm AM, Affandi T, Reyland ME. EGF receptor and PKCdelta kinase activate DNA damage-induced pro-survival and pro-apoptotic signaling via biphasic activation of ERK and MSK1 kinases. J Biol Chem 2019;294(12):4488–97 doi 10.1074/jbc.RA118.006944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Matassa AA, Carpenter L, Biden TJ, Humphries MJ, Reyland ME. PKCdelta is required for mitochondrial-dependent apoptosis in salivary epithelial cells. J Biol Chem 2001;276(32):29719–28 doi 10.1074/jbc.M100273200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.DeVries TA, Neville MC, Reyland ME. Nuclear import of PKCdelta is required for apoptosis: identification of a novel nuclear import sequence. EMBO J 2002;21(22):6050–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nair N, Shoaib M, Sorensen CS. Chromatin Dynamics in Genome Stability: Roles in Suppressing Endogenous DNA Damage and Facilitating DNA Repair. Int J Mol Sci 2017;18(7) doi 10.3390/ijms18071486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fenech M, Knasmueller S, Bolognesi C, Holland N, Bonassi S, Kirsch-Volders M. Micronuclei as biomarkers of DNA damage, aneuploidy, inducers of chromosomal hypermutation and as sources of pro-inflammatory DNA in humans. Mutat Res Rev Mutat Res 2020;786:108342 doi 10.1016/j.mrrev.2020.108342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kuo LJ, Yang LX. Gamma-H2AX - a novel biomarker for DNA double-strand breaks. In Vivo 2008;22(3):305–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sanders MM. Fractionation of nucleosomes by salt elution from micrococcal nuclease-digested nuclei. J Cell Biol 1978;79(1):97–109 doi 10.1083/jcb.79.1.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fnu S, Williamson EA, De Haro LP, Brenneman M, Wray J, Shaheen M, et al. Methylation of histone H3 lysine 36 enhances DNA repair by nonhomologous end-joining. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2011;108(2):540–5 doi 10.1073/pnas.1013571108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Duan MR, Smerdon MJ. Histone H3 lysine 14 (H3K14) acetylation facilitates DNA repair in a positioned nucleosome by stabilizing the binding of the chromatin Remodeler RSC (Remodels Structure of Chromatin). J Biol Chem 2014;289(12):8353–63 doi 10.1074/jbc.M113.540732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ljungman M, Parks L, Hulbatte R, Bedi K. The role of H3K79 methylation in transcription and the DNA damage response. Mutat Res Rev Mutat Res 2019;780:48–54 doi 10.1016/j.mrrev.2017.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wu-Zhang AX, Murphy AN, Bachman M, Newton AC. Isozyme-specific interaction of protein kinase Cdelta with mitochondria dissected using live cell fluorescence imaging. J Biol Chem 2012;287(45):37891–906 doi 10.1074/jbc.M112.412635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ohm AM, Tan AC, Heasley LE, Reyland ME. Co-dependency of PKCdelta and K-Ras: inverse association with cytotoxic drug sensitivity in KRAS mutant lung cancer. Oncogene 2017;36(30):4370–8 doi 10.1038/onc.2017.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nakagawa M, Oliva JL, Kothapalli D, Fournier A, Assoian RK, Kazanietz MG. Phorbol ester-induced G1 phase arrest selectively mediated by protein kinase Cdelta-dependent induction of p21. J Biol Chem 2005;280(40):33926–34 doi 10.1074/jbc.M505748200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Santiago-Walker AE, Fikaris AJ, Kao GD, Brown EJ, Kazanietz MG, Meinkoth JL. Protein kinase C delta stimulates apoptosis by initiating G1 phase cell cycle progression and S phase arrest. J Biol Chem 2005;280(37):32107–14 doi 10.1074/jbc.M504432200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.LaGory EL, Sitailo LA, Denning MF. The protein kinase Cdelta catalytic fragment is critical for maintenance of the G2/M DNA damage checkpoint. J Biol Chem 2010;285(3):1879–87 doi 10.1074/jbc.M109.055392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Klein BJ, Jang SM, Lachance C, Mi W, Lyu J, Sakuraba S, et al. Histone H3K23-specific acetylation by MORF is coupled to H3K14 acylation. Nat Commun 2019;10(1):4724 doi 10.1038/s41467-019-12551-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu L, Liu J, Lin Q. Histone demethylase KDM2A: Biological functions and clinical values (Review). Exp Ther Med 2021;22(1):723 doi 10.3892/etm.2021.10155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fiorentino F, Carafa V, Favale G, Altucci L, Mai A, Rotili D. The Two-Faced Role of SIRT6 in Cancer. Cancers (Basel) 2021;13(5) doi 10.3390/cancers13051156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Miteva YV, Cristea IM. A proteomic perspective of Sirtuin 6 (SIRT6) phosphorylation and interactions and their dependence on its catalytic activity. Mol Cell Proteomics 2014;13(1):168–83 doi 10.1074/mcp.M113.032847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Van Meter M, Simon M, Tombline G, May A, Morello TD, Hubbard BP, et al. JNK Phosphorylates SIRT6 to Stimulate DNA Double-Strand Break Repair in Response to Oxidative Stress by Recruiting PARP1 to DNA Breaks. Cell Rep 2016;16(10):2641–50 doi 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Thirumurthi U, Shen J, Xia W, LaBaff AM, Wei Y, Li CW, et al. MDM2-mediated degradation of SIRT6 phosphorylated by AKT1 promotes tumorigenesis and trastuzumab resistance in breast cancer. Sci Signal 2014;7(336):ra71 doi 10.1126/scisignal.2005076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Park CH, Kim KT. Apoptotic phosphorylation of histone H3 on Ser-10 by protein kinase Cdelta. PLoS One 2012;7(9):e44307 doi 10.1371/journal.pone.0044307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Reyskens KM, Arthur JS. Emerging Roles of the Mitogen and Stress Activated Kinases MSK1 and MSK2. Front Cell Dev Biol 2016;4:56 doi 10.3389/fcell.2016.00056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Klein BJ, Krajewski K, Restrepo S, Lewis PW, Strahl BD, Kutateladze TG. Recognition of cancer mutations in histone H3K36 by epigenetic writers and readers. Epigenetics 2018;13(7):683–92 doi 10.1080/15592294.2018.1503491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tian X, Firsanov D, Zhang Z, Cheng Y, Luo L, Tombline G, et al. SIRT6 Is Responsible for More Efficient DNA Double-Strand Break Repair in Long-Lived Species. Cell 2019;177(3):622–38 e22 doi 10.1016/j.cell.2019.03.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kanfi Y, Naiman S, Amir G, Peshti V, Zinman G, Nahum L, et al. The sirtuin SIRT6 regulates lifespan in male mice. Nature 2012;483(7388):218–21 doi 10.1038/nature10815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary data file S1. Results of mass spectrometry histone profiling of shNT, shδ110 and shδ680 cells. Spreadsheet includes average percent of each modification, standard deviation, and coefficient of variance (CV).

Supplementary Fig. S1. Correlation of copy number variants (CNV) and PKCδ expression in LUAD and HNSCC.

Supplementary Fig. S2. PKCδ regulates expression of genes required for DNA repair.

TCGA Analysis

Supplementary Table S1. List of plasmids used in this study.

Supplementary Table S2. List of primers used for qRT-PCR.