Abstract

The plasma membrane is crucial to the survival of animal cells, and damage to it can be lethal, often resulting in necrosis. However, cells possess multiple mechanisms for repairing the membrane, which allows them to maintain their integrity to some extent, and sometimes even survive. Interestingly, cells that survive a near-necrosis experience can recognize sub-lethal membrane damage and use it as a signal to secrete chemokines and cytokines, which activate the immune response. This review will present evidence of necrotic cell survival in both in vitro and in vivo systems, including in C. elegans, mouse models, and humans. We will also summarize the various membrane repair mechanisms cells use to maintain membrane integrity. Finally, we will propose a mathematical model to illustrate how near-death experiences can transform dying cells into innate immune modulators for their microenvironment. By utilizing their membrane repair activity, the biological effects of cell death can extend beyond the mere elimination of the cells.

Keywords: Plasma membrane damage, membrane damage repair, programmed necrosis, innate immunity, ESCRT, tetraspanin, chemokines

Introduction

Since the first cells on Earth about 4 billion years ago, the cell plasma membrane (PM) has served as the essential barrier to segregate the outside and create a safe internal environment for biochemical reactions. Meanwhile, the cell PM is also the first defender and sensor against external and internal perturbations. In theory, any perturbation that may severely disrupt the function of cell membranes should be recognized as a “challenge” and activate a multifactorial stress response, including innate immune responses.

However, at first sight, the loss of PM integrity may seem to be “lethal”, which irreversibly compromises the viability of cells. It may seem once an animal cell loses its PM integrity (e.g., due to membrane pore-forming), many critical cellular components, such as ions, proteins, and ATP, are all gone. Thus, due to lack of these key components, the dying/dead cells may be unable to make any reactions to “alert” the surroundings upon such PM damage, especially considering animal cells don’t have a rigid cell wall to support the cellular structures. Therefore, although PM damage is dangerous, it is not universally regarded as a dangerous signal (Danger-associated molecular pattern, DAMP) by the damaged cells.

The recent discovery of many PM repair machineries that can hold PM integrity after damage suggests that PM damage can be “sub-lethal” (1). This means cells can tolerate certain membrane damage without lysis and sometimes come back to life and revive. During this “surviving” time, PM-damaged cells may recognize the sub-lethal PM integrity loss as an innate immune activation pattern, thus turning it into cellular responses, which may affect the immune microenvironment.

Recently, there have been comprehensive reviews of membrane repair mechanisms and their potential implications for health and disease (2–5). In this review, we will systematically summarize the evidence that cells can survive “sub-lethal” membrane damage, including from programmed cell death and non-specific PM perturbations; we will introduce the repair mechanisms of programmed cell death-elicited membrane damage, followed by the sections describing how non-specific PM disruption, such as from plaques and wound damage, can be repaired; last, we will propose a model to discuss how dying cells can sense sub-lethal PM integrity loss and change the landscape of the local immune-environments, in the pathological contexts.

1. Cells can come back from “sub-lethal” plasma membrane damage

1.1. Cells on the edge of programmed cell death

Cell death can be broadly classified into two forms: accidental cell death (ACD) and regulated cell death (RCD). We will describe a basic framework of cell death classifications, while for comprehensive definitions of cell death terms, we suggest this review (6). ACD is an instantaneous and uncontrollable form of cell death that results from extreme physical, chemical, or mechanical cues that lead to PM disassembly. In contrast, RCD occurs through the activation of one or more signal transduction modules and can be modulated pharmacologically or genetically. Most programmed cell death (PCD) forms belong to RCD, occurring in strictly physiological scenarios. PCD includes several forms, such as apoptosis, necroptosis, pyroptosis, and ferroptosis. Apoptosis can happen by two pathways: the intrinsic and extrinsic pathways. The intrinsic pathway is initiated by mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization (MOMP), resulting in Cytochrome C release and apoptosome activation, including Apaf-1 and caspase-9, followed by the activation of executioner caspases, mainly caspase-3. The extrinsic pathway is initiated by PM receptors, such as death receptors, propagated by caspase-8, followed by executioner caspase activation, including caspase-3. In some cases, cells may switch to necroptosis instead of extrinsic apoptosis if caspase-8 (or sometimes receptor-interacting protein kinase 1 (RIPK1)) is inactivated. Necroptosis involves the activation of receptor-interacting protein kinase 3 (RIPK3) and mixed lineage kinase domain-like (MLKL), leading to PM damage (for details, see below). Pyroptosis is mediated by cleaved gasdermin family proteins, which are the substrates of inflammatory caspases, such as caspase-1, 4, 5, and 11. Other proteases like granzymes may also activate gasdermins to execute cell death. Ferroptosis occurs due to severe lipid peroxidation that relies on ROS generation and iron availability. It is important to note that only apoptosis is a non-lytic form of cell death, meaning that the PM still holds its integrity during apoptosis. In contrast, necroptosis, pyroptosis, and ferroptosis involve PM rupture and are lytic forms of cell death, thus considered necrosis. It is also worth noting that not all forms of necrosis are RCD or programmed. ACD can also (most likely “always”) result in necrosis. This manuscript mainly focuses on the cells that can survive necrosis, programmed and accidental (non-specific).

In the Merriam-Webster dictionary, one definition for “death” is “a permanent cessation of all vital functions.” The underlying assumption is that dead cells must have passed the “point of no return” of a “death” process, moving monotonously toward the “permanent cessation.” However, this “point of no return” is hard to define, considering the complexity of the cell death process.

It is well documented that apoptotic cells can return to life even after caspases are activated, or mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization (MOMP) has occurred. The apoptosis “come-back” is termed “anastasis” (the Greek word meaning ‘resurrection,’ Figure 1) (7–9). It is worth noting that neither caspase activation nor MOMP represents the “point of no return” of apoptosis. Anastasis has been widely observed in various organisms, from worms and fruit flies to mammals. The first report of anastasis could be traced back to 2001. In several C. elegans engulfment mutants, some cells that typically die in WT worms could first display apoptotic features but eventually survive and ultimately differentiate (10). Multiple mechanisms can facilitate anastasis. One such mechanism is known as “incomplete MOMP (iMOMP),” observed in in vitro mammalian cell culture systems (9). Possibly, not every mitochondrion in an apoptotic cell needs to undergo MOMP to initiate cell death. The remaining intact mitochondria can provide the key “seeds” for mitochondrial outgrowth and repopulation and ultimately permit cell recovery. Additionally, RNAseq data generated from HeLa cells also revealed the transcription factor Snail is crucial for anastasis (11). Akt1 and dCIZ1 are also shown to be required for cell survival from apoptotic caspase activation in Drosophila (12).

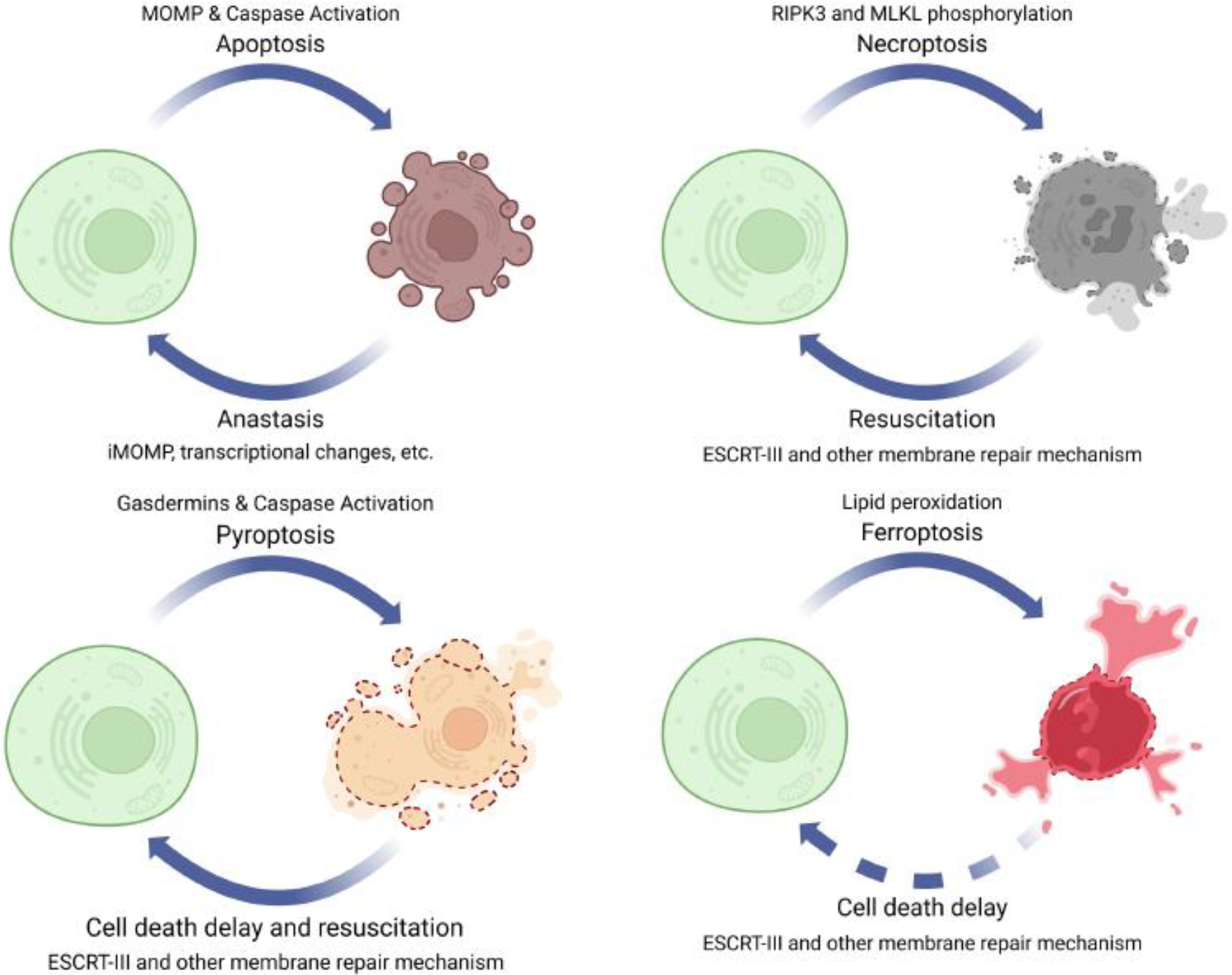

Figure 1. Cells can come back from programmed cell death.

Cell death is not a “one-way” street. Many mechanisms can halt cell death. Apoptosis, necroptosis, and pyroptosis can even be rescued from the edge of death.

It is feasible that apoptotic cells may recover from the brink of death since their intact PM structure allows for the maintenance of a buffered system where necessary biochemical reactions can occur. However, for necrosis involving PM pore-formation and damage, in most cases, cells can only make a U-turn and return to “life” until PM repair actions overwhelm pore-formation (13). In addition, some PM pores can self-close and will be discussed below.

The first reported “reversed” necrosis is necroptosis (14). Necroptosis is mediated by a specific signaling pathway that involves several key proteins, such as RIPK1, RIPK3, and MLKL (15). Once RIPK3 phosphorylates MLKL, it undergoes a conformational change that exposes its N-terminal execution domain, leading to the formation of MLKL oligomers. These oligomers then translocate to PM, where they insert into the lipid bilayer and form pores, leading to membrane disruption and necroptotic cell death (16). Since p-MLKL can directly perform pore-forming activity on the PM, MLKL phosphorylation is often considered the executor and the ‘point of no return’ for necroptosis. But this is not always true.

Two major strategies have been successfully used to rescue p-MLKL+ necroptotic cells from the edge of death, a process known as “resuscitations” (Figure 1) (14). First, the MLKL inhibitor necrosulfonamide (NSA) was employed for rescuing human necroptotic cells. NSA covalently links to cysteine 86 of human MLKL, thus blocking MLKL oligomerization and the subsequent membrane damage (17). When NSA is applied to p-MLKL+ necroptotic cells, most dying cells can be resuscitated, as the PM repair activity can overwhelm the NSA-abolished PM damage from p-MLKL. The other approach uses (tandem) FK506 binding protein (FKBP) domain (Fv)/dimerization/washout system. Upon binding to the small molecule A20187 (B/B), the Fv domain rapidly dimerizes/oligomerizes. Thus, when RIPK3 or MLKL are fused with the Fv domains and stimulated by B/B, they can quickly oligomerize and activate, performing PM damage and resulting in necroptosis. The washout ligand is another small molecule compound that competes with B/B and disrupts oligomers induced by B/B-Fv domain binding. Thus, the washout ligand can terminate the B/B-activated RIPK3 or MLKL. Like NSA, washout ligands can also promote cellular resuscitation. Detailed experimental design was originally reported in reference (14).

Another form of programmed necrosis, pyroptosis, can also be halted through regulations of membrane repair mechanisms (Figure 1). Gasdermins are a family of proteins responsible for executing the final steps of pyroptosis by forming membrane pores (18). In response to inflammasome activation, caspase-1/4/11 cleaves and activates Gasdermin D (GSDMD). The N-terminus of GSDMD then translocates to the PM and creates large pores, disrupting membrane integrity and causing pyroptotic cell death. Recent studies have also shown that other gasdermins, including GSDMA/B/C/E, may mediate pyroptosis (19). These gasdermins can be activated by different caspases or proteases, leading to membrane pore-forming and cell lysis (also considered pyroptosis).

Membrane pores made by gasdermins, such as GSDMD, can be repaired (20). Pathways mediating gasdermin damage repair will be detailed in Section 2. Pyroptosis can be induced by cytosolic lipopolysaccharide (LPS) delivery (achieved by Fugene HD reagents), activating caspase-11 and GSDMD (21). A high dose of LPS delivery was effective in inducing pyroptosis, whereas a low dose of LPS delivery only triggered cell death if the cells lacked a mechanism for membrane repair. Membrane repair mechanisms were also found to have a negative regulatory effect on the release of interleukin-1β (IL-1β), which is controlled by GSDND pores (21). Note that this PM repair-tuned regulation of IL-1β release adds another level of modulation on IL-1β signaling, as it didn’t influence on the upstream inflammasome formation (resulting in IL-1β maturation), caspase-1 activation (also resulting in IL-1β maturation), or GSDMD processing (resulting in PM pore-formation). Further, researchers discovered that pyroptotic cells can recover after PM damage in a study utilizing an optogenetic approach to control caspase-1 activation (light-activatable human caspase-1). By adjusting illumination intensity and duration, they could precisely manipulate the protein activation level. Interestingly, when subjected to moderate illumination, which induced “sub-lethal” caspase-1 activation, some cells first exhibited early pyroptosis characteristics. Next, these cells not only managed to survive but also returned to their normal morphology within a timeframe of 30–40 minutes. These observations suggest the possibility of “resuscitating” pyroptotic cells (22). Moreover, independent of the PM repair activity, GSDMD pores can also spontaneously self-close without membrane disruption. This process is regulated by local phosphoinositide circuitry (23).

Ferroptosis is another form of regulated necrosis characterized by lipid peroxide accumulation that leads to oxidative damage and cell death. The accumulation of lipid peroxides in the PM can destabilize lipid bilayer and result in pore formation. Ferroptotic pores can also be repaired with Ca2+ influx (detailed in Section 2) (24, 25). Lack of membrane repair mechanism leads to hypersensitization of dying cells toward ferroptosis (Figure 1) (24, 25).

PM pore-forming can also be generated from outside the cells (13). CD8 T cells and natural killer (NK) cells kill virus-infected and tumor cells by releasing perforin, a member of the membrane attack complex/perforin (MACPF) family. Perforin shares a similar structure with the gasdermin N-terminus, with amphipathic β-strands inserting into the PM to make pores (26). PM damaged by perforin pores can also be efficiently repaired, contributing to the resistance of NK cells and CD8 T cell-mediated killing in anti-tumor immunity (27) and Chromobacterium violaceum and Listeria monocytogenes clearance (28).

In summary, for programmed necrosis, although PM damage repair that can slow down cell death has been well documented in many cases, only necroptotic and pyroptotic cells have been clearly shown to be resuscitated from the edge of cell death and survive (14, 22) (Figure 1). This is possibly due to the fact that the ferroptotic machinery is not easy to turn off. However, we want to emphasize that, many kinds of PM damage, including the generic PM damage that is not associated with programmed cell death, can also be repaired. Generic PM damage may also result in cell death unless properly repaired. For example, laser-induced PM damage can lead to propidium iodide uptake, a marker for necrosis, if the repair activity is deficient (13). We will discuss generic PM damage and repair in 1.2.

1.2. Cell recovery from PM damage in multicellular organisms

PM damage repair is well documented in single cells and in in vitro systems, but it also occurs in multicellular organisms. In vivo, studies have primarily concentrated on multicellular wound repair research due to their efficiency and clinical relevance (29). However, several small animal models have been used to study would responses at the cellular level, including C. elegans, Drosophila, and Xenopus (30–33). Among these, C. elegans has emerged as a powerful model for several reasons (34, 35). Firstly, C. elegans epidermal syncytium hyp7 is a giant multinuclear cell consisting of 139 somatic nuclei enveloping the whole body, thus providing a large target for PM damage. Secondly, C. elegans is light-transparent, allowing live imaging. Thirdly, C. elegans is predominantly hermaphroditic, making it a versatile genetic system with access to diverse genetic techniques. Lastly, hyp7 can initiate a repair response and trigger an innate immune response to membrane damage in both epidermal and neuronal cells (36, 37). The combination of the epidermal anatomy and multinucleated cell biology, and a history of complex observations about C. elegans viability, make this experimental system a fascinating platform for discoveries. Indeed, these properties are the basis of the robust whole-organism functional assays of cellular membrane repair that can be explored in the study of this model. However, it is important to note that the single syncytium hyp7 in C. elegans is distinct from most somatic cells in other species and may possess unique systems to repair membrane damage. For instance, hyp7 has been observed to tolerate significant physical damage exceeding a diameter of 10 μm, which is too large for somatic cells to repair. This leads to a notable response within the intracellular endomembrane material, which supplies the necessary membrane material for efficient repair (38). Following membrane resealing, a scar forms at the damaged site, further exemplifying the unique characteristics of the remodeling process (32).

Although PM damage can be caused by intracellular sources like programmed death pathways and extracellular sources like mechanical force, chemical injury, microbial invasion, and immune attack (2), microinjection needle and laser wounding are the most commonly used methods to damage epidermal PM in C. elegans, resulting in wounds with diameters from 1 μm to 10 μm (32, 39, 40). Normally these PM wounds can be closed in hours in wild-type (WT) animals. Several classic PM damage repair processes, such as Ca2+ influx, cytoskeleton remodeling, and mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, have been observed in C. elegans’ epidermal wounding model (35, 41). Besides, works with C. elegans discovered novel conserved repair protein machineries or new functions of “old” proteins, promoting an understanding of early wound response, repair, and later remodeling (see examples section 2.6).

It is worth noting that PM repair is a complex and dynamic process, and recent studies have identified additional players and mechanisms involved in this process. For example, an influx of Ca2+ ions often accompanies membrane repair. We will discuss the function of Ca2+ influx in Section 2. Additionally, the formation and recruitment of repair proteins and vesicles to the wound site are critical for successful PM repair. Further research in C. elegans and other models is necessary to fully understand the mechanisms involved in PM repair and identify potential therapeutic targets for PM damage-related diseases.

1.3. The counterbalance of pore-formation and repair in human diseases

PM damage and repair frequently occur in physiological conditions throughout the body. PM damage has been observed in various organs, including skeletal muscle, cardiac muscle, skin, gastrointestinal tract, the respiratory system, and the peripheral nervous system (42), and it is more likely to affect cells exposed to mechanical and metabolic stress (3, 43). For example, skeletal and cardiac myocytes can be injured during eccentric muscle contraction (44, 45). 3–20% of skeletal and 25% of cardiac myocytes display membrane damage (46, 47). After eccentric exercise, there was a 6.9-fold increase in the number of PM injured cells in the medial head of rat triceps compared to untrained controls (47). In some cases, PM damage can also serve as the immune system’s tool to remove invaders or damaged cells (48, 49).

PM damage can also occur as a result of pathological conditions. Several diseases and conditions can cause PM damage, including skeletal muscle contraction, brain injury, ischemia-reperfusion and cancer invasion and metastasis (3). Muscular dystrophy (MD) is a group of diseases that cause weakness and degeneration of muscles and is characterized by increased membrane permeability at the early stage (50), caused by mutations in dystrophin, calpain-3, and/or dysferlin (3, 51, 52). Similarly, PM integrity loss following brain injury is a pathomechanism of Alzheimer’s disease (AD), promoting the aggregation of amyloid-β (53). Disease proteins can increase membrane permeability through various mechanisms, including protein-induced membrane rigidity, membrane thinning, a detergent-like effect, and pore formation (3, 54). In the case of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), surfactant dysfunction and inflammatory response activation cause PM damage in the lung (55), while ventilation induces mechanical membrane injury to pneumocytes (56).

In kidney transplantation procedures, healthy human kidney tissue, immediately obtained from living donor biopsies after excision, did not exhibit any positive signal for p-MLKL. In contrast, after the transplantation into the recipient, pronounced p-MLKL was observed in endothelial cells (14). In mouse models, it has been shown that RIPK3 and MLKL contribute to the risk of chronic kidney diseases triggered by acute renal ischemia-reperfusion injury (57). Despite the lack of clarity regarding the precise trigger for MLKL phosphorylation during kidney transplantation, emerging evidence suggests that hypoxia-mimicking conditions can potentially initiate necroptosis (58). Notably, these stressed cells appeared normal without any signs of cell death, suggesting that the PM damage repair pathway successfully counteracted the pore-formation by p-MLKL (14). We will discuss the biological roles of these p-MLKL-containing cells in kidney transplantation in Section 3.

Sub-lethal level of p-MLKL positivity in late-stage solid tumor cells and leukemia cells (e.g., AML) was also reported (59–61). Inhibiting PM repair mechanisms in cancer cells augments the anti-tumor immune response, mainly because some CD8 T cell-required anti-tumor immunotherapies (such as checkpoint-blockades) rely on perforin or cancer cell gasdermin-pyroptosis (27, 62). Moreover, cancer invasion causes extreme physical stress and increased PM damage. Invasive cancer cells tend to upregulate PM repair systems, such as the annexin family of proteins, to cope with the increased frequency of membrane injuries (63, 64). Thus, blocking membrane repair mechanism has the potential to be developed into a synergistic approach to augment the anti-tumor immune response.

Cell survival after PM pore-formation was also observed in infectious diseases. Candidalysin is a pore-forming peptide toxin secreted by C. albicans (65). To prevent cell death, the infected epithelial cells need to protect themselves from candidalysin-induced damage. Two essential Ca2+-dependent repair mechanisms (see below) have been identified in epithelial cells to resist the candidalysin-producing hyphae. These two repair mechanisms ensure the integrity of epithelial cells and prevent mucosal damage during commensal growth and C. albicans infection.

2. Plasma Membrane repair mechanisms

The mechanism engaged to repair membrane damage depends on wound size. The size of PM damage can vary from the nanoscale to the microscale depending on the source of damage, and cells have evolved various repair mechanisms to cope with such damage (50). Minor membrane wounds can be healed by self-sealing, exocytosis, or endocytosis, such as Endosomal Sorting Complex Required for Protein Transport (ESCRT)-mediated shedding (see 2.1) and the acidic sphingomyelinase (ASM)-dependent endocytosis (see 2.2). Pore-forming toxins (PFTs) may also be exocytosed or endocytosed. The patch model can quickly reseal large wounds, and cytoskeleton remodeling and ring contraction are also required for repair (see 2.3–6). These repair mechanisms are not mutually exclusive and can act in concert to restore PM integrity (Summarized in Figure 2).

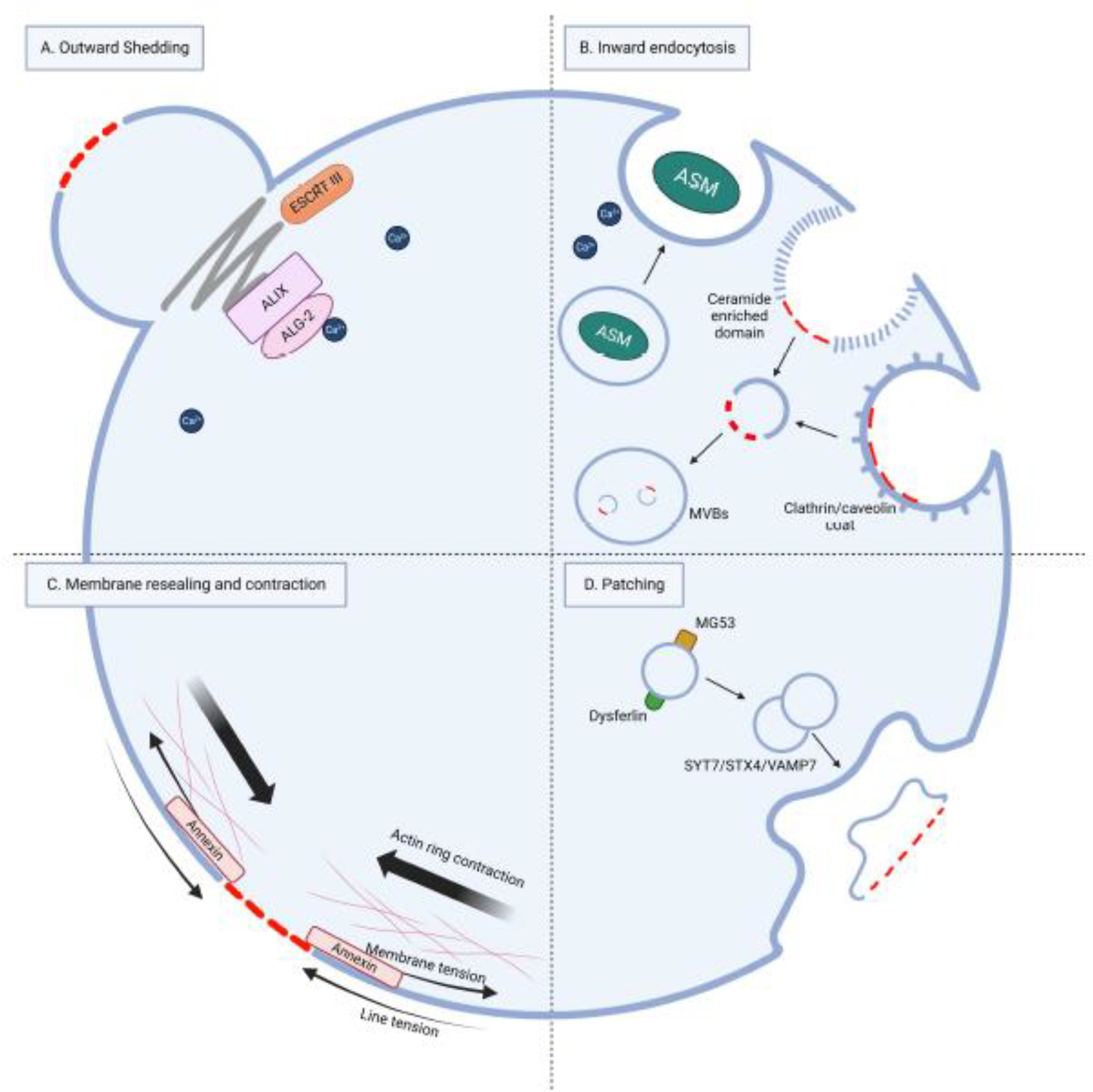

Figure 2. Overview of membrane repair mechanisms.

(A) Outward shedding of the damaged PM can be mediated by the ESCRT complex. Wounding-induced Ca2+ influx sensors ALIX and ALG-2 are necessary to assemble the ESCRT complex. (B) Inward endocytosis mediated by ASM, clathrin, and caveolin can internalize and degrade the damaged membrane in multivesicular bodies (MVB). (C) A damaged membrane can undergo self-resealing under two opposite forces: line and membrane tension. Actin ring contraction beneath the wound and Annexin4/5 activation facilitate wound closure. (D) Patching model, a patch is formed by the fusion of intracellular vesicles or lysosomes and fuses with the damaged PM, mediated by SNARE complexes.

2.1. Outward shedding

The ESCRT machinery is a complex of proteins initially discovered in yeast from genetic screens. It plays a crucial role in regulating protein trafficking and the formation of intraluminal vesicles within multivesicular bodies (MVBs) (66). This machinery consists of several sub-complexes (ESCRT-0, -I, -II, and -III). It is capable of deforming membranes away from (against) the cytosol, leading to the formation of vesicles on the distal side of the membrane. The process is classified as ‘reverse’ or ‘inverse’-topology membrane scission (67, 68). In addition to its involvement in cytokinesis, MVB generation, virus budding, and restoration of the nuclear envelope, the ESCRT machinery has recently been found to be responsible for repairing small generic holes (less than 100 nm in diameter) in the PM of mammalian cells (13). Components of the ESCRT-0, -I, and -II sub-complexes are sometimes dispensable, while the ESCRT-III complex is always essential for membrane repair (13). ESCRT components are recruited to the PM wound sites in response to treatment with mild detergents, bacterial pore-forming toxins, or laser in a Ca2+-dependent manner (13). ALIX and ALG-2 function as Ca2+ influx sensors required for ESCRT complex assembly (69). The activity of ESCRT in sealing membranes is carried out by the α-helical proteins of the CHMP family (such as CHMP4B and CHMP2A), along with the VPS4 AAA ATPase, which drives membrane deformation and scission. The ESCRT’s action can mediate the shedding-off of the damaged PM to the extracellular space and, at the same time, reseal the otherwise intact PM fractions (Figure 2A). The shedding-off-ed broken membrane “bubbles” are usually referred to as “exctosomes” (70).

In addition to general PM wound repair, ESCRT-III protein complex can also repair PM damage caused by p-MLKL during necroptosis in the same manner (14, 58). ESCRT components were found in the membrane-localized MLKL immunoprecipitates and in the p-MLKL-associated extracellular vesicles released from necroptotic cells. This process supports necroptotic cell resuscitation (14). Flotillin-1 and -2 were also found to be associated with p-MLKL. In necroptotic cells, the ESCRT complex, together with flotillins, can facilitate dying necroptotic cells (and also the resting cells with low basal levels of necroptosis) to release “exctosomes” and extracellular vesicles (usually referred to as “exosomes”) that contain p-MLKL. Flotillins can also mediate endocytosis of p-MLKL-containing lipid raft (70). Both mechanisms can remove p-MLKL from the PM, restricting necroptotic activity (70–72) and rescuing cells from death (14). The ESCRT system can also repair gasdermin pores (e.g., N-terminus of GSDMD). Although pyroptotic cells can be resuscitated after they have engaged caspase-1 or -11 to cleave gasdermins, the role of ESCRT in pyroptotic resuscitation has not been tested (20). Similarly, ESCRT can also repair damaged PMs in ferroptosis and perforin-induced cell lysis (24, 25, 27). It is not entirely clear which signals, in addition to Ca2+ influx, regulate the initiation of membrane repair mechanisms during programmed cell death. Whether lipid composition changes at the local pore-forming sites can also serve as a cue for ESCRT-mediated membrane repair is still under investigation.

Besides removing the damaged membrane from small-scale injury or pore formation, ESCRT-III has also been suggested to be necessary for repairing large-scale membrane damage in vivo in C. elegans. In response to wounding, VPS-32.1(CHAM4B ortholog) and VPS-4 (VPS4A/B ortholog) are recruited to the wound site caused by a microinjection needle, typically resulting in an approximately 10 μm diameter wound (73). The accumulation of ESCRT-III components at the wound periphery is crucial, as it enables the further recruitment of tetraspanin protein TSP-15, the membrane fusion protein Syntaxin-2 (SYX-2), and epithelial fusion failure (EFF-1), which are necessary for membrane repair (73, 74). Although polymerized ESCRT-III is essential for membrane shedding, the detailed mechanism by which the recruited ESCRT-III sculpts the membrane structure and regulates membrane repair machinery is mainly unknown.

2.2. Inward endocytosis

Besides ESCRT-III, which remodels the membrane to the outward direction from the cell cytosol, the ASM pathway acts oppositely moving damaged membranes inward into the cytosols. Inward endocytosis is another process that can remove small damaged membrane sections or transmembrane pores caused by PFTs from the PM in mammalian cells. This process involves the activation of clathrin and caveolin-mediated endocytosis to form endosomes, which are then sorted for degradation (3). In addition, endosome formation can also be triggered by the lysosome ASM axis (Figure 2B) (75). When the PM is damaged by Streptolysin O, S. aureus toxins, Vibrio cholera cytolysin, perforins, or gasdermins, Ca2+ influx at the wound site triggers the exocytosis of secretory lysosomes containing ASM. Upon release from the lysosomes, ASM hydrolyzes sphingomyelin on the outer leaflet of the PM, generating ceramide. Ceramide has a high affinity for cholesterol and other lipids, promoting the formation of lipid rafts around the site of membrane damage. These lipid rafts induce local membrane invagination, which allows for enhanced endocytosis around the sites of injury, thereby removing stable transmembrane pores. Once internalized, the damaged membrane components travel along the endo-lysosomal pathway to be degraded in multivesicular bodies. Moreover, the pore-forming proteins mentioned above are also removed by inward endocytosis (75–78). However, the endocytosis pathway can be hijacked as pathogenic entry to the host cell by parasites, such as adenoviruses and T. cruzi (79, 80). Caspase-7 can also regulate the ASM-mediated repair pathway (81). In bacterial infection models, caspase-7 antagonized gasdermin D-mediated damage and maintained cell integrity by cleaving ASM at D249 and activating it. The D249A mutation in ASM (resistant to caspase-7 cleavage) impaired its membrane repair function (28).

In addition, PM tension decrease caused by cell volume reduction in cancer cells can also trigger clathrin-independent endocytosis, mediated by the GTPase-activating protein GRAF1 (82). However, it is not clear whether GRAF1-mediated endocytosis responds to wound-induced tension reduction.

2.3. Membrane resealing and contraction

Membrane resealing and contraction are two fundamental mechanisms that cells use to repair damage to PM. Spontaneous resealing can occur quickly (in milliseconds) in small wounds, but larger wounds may require the contraction of an actomyosin ring to prevent further expansion and provide a platform for cytoskeleton repair (Figure 2C) (83).

When a continuous lipid bilayer is broken, the hydrophobic tails of the lipids are exposed to water, causing lipid reorientation and curved edge around the wound. The lipids on the edge are now disordered and provides a force for resealing called line tension (42, 84). However, if the bilayer is attached to an underlying cytoskeleton, an opposing force called membrane tension is present, which decreases membrane fluidity and opposes resealing (42, 85). Therefore, reducing membrane tension is essential for membrane self-resealing. Annexins are proteins that are abundant in the cytosol and bind to Ca2+ ions. They tend to accumulate on cell membranes when the concentration of Ca2+ in the cytosol increases after wounding (86, 87). One possible mechanism by which annexins help seal mammalian PM is by reducing membrane tension, self-assembling into a 2D array, which recruits vesicles to promote sealing (86, 88, 89). In addition, annexins may form multimeric structures that physically block holes in the membrane (88).

For larger wounds, cytoskeleton remodeling is necessary to increase contraction and wound tension (30–32). Several results in rat gastric epithelial cells have shown that actin depolymerization promotes resealing and actin cytoskeleton stabilization inhibits resealing (90). In micro-punctured alveolar epithelial type I cells, exocytosis and actin depolymerization are sustained until PM integrity is recovered (91). After the PM is resealed, actin polymerization forms a dense actin fiber network and restores PM integrity (32, 92).

During wound repair, an actomyosin ring undergoes contraction in various cells, including frog oocytes and embryos, Drosophila embryos, mammalian muscle, and plant cells (30, 92–94). The formation of this ring relies on the immediate Ca2+ influx and Rho activation after wounding (26, 28). Similar to cytokinesis and to certain morphogenetic process, an actomyosin ring is formed at the wound by the cortical flow of F-actin, which is powered by myosin and by the local assembling of F-actin and myosin-2 (94). Additionally, in Xenopus oocytes, a highly dynamic zone of actin and myosin-2 polymerization is formed around the wound and functions as a purse string to close the wound (94). F-actin pulls microtubules toward the wound in this zone and facilitates actomyosin recruitment (95). The self-resealing and contraction models are not mutually exclusive. The effect of regulating cytoskeleton dynamics in PM repair discussed above may depend on various factors, including the size of the wounds, the type of cells, and the time points in wound repair.

2.4. Patching

The patch model proposes that a large continuous membrane patch is formed under the wound site through the homotypic fusion of the internal compartment, which then fuses with the PM to replace the damaged region (Figure 2D) (96, 97). This model explains how neurons can survive axonal transection and how sea urchin eggs can reseal large (~40 by 10 μm) wounds in just a few minutes (98–100). The model is supported by several observations, including the presence of abnormally large vesicles beneath the wound, large domains of the resealed membrane being cytoplasm-derived, and the vesicles for forming the patch in sea urchin being able to undergo rapid and extensive fusion in vitro (42, 97). The patch model also suggests that intracellular vesicle translocation and subsequent Ca2+-induced fusion are two separate processes. The oxidation-mediated mistugunin-53 (MG53), a phosphatidylserine-binding protein, is utilized to detect damage and may initiate intracellular vesicle translocation (101). The patch model has been visualized in wounded Xenopus laevis oocytes (96), revealing a process known as “explodosis.” This process describes the subcellular behavior of outward exposure of intracellular compartments to the PM by rupture, resulting in the fusion of the double-membrane patch with the single-membrane PM (96). Large wounds have also been created in C. elegans epidermal cell; where vesicles and the repair machinery have been observed to be recruited to the wound site (40, 73, 74), indicating the wound may be repaired via a membrane patch generated intracellularly.

2.5. Repair process – C. elegans epidermal cell (hyp7) as an example

Traditionally, skin wound healing follows four steps: hemostasis, inflammation, proliferation and migration, and resolution and remodeling. Although the processes for single-cellular membrane repair have not been thoroughly described, they can be roughly divided into three stages: early wound response, repair, and remodeling (Figure 3).

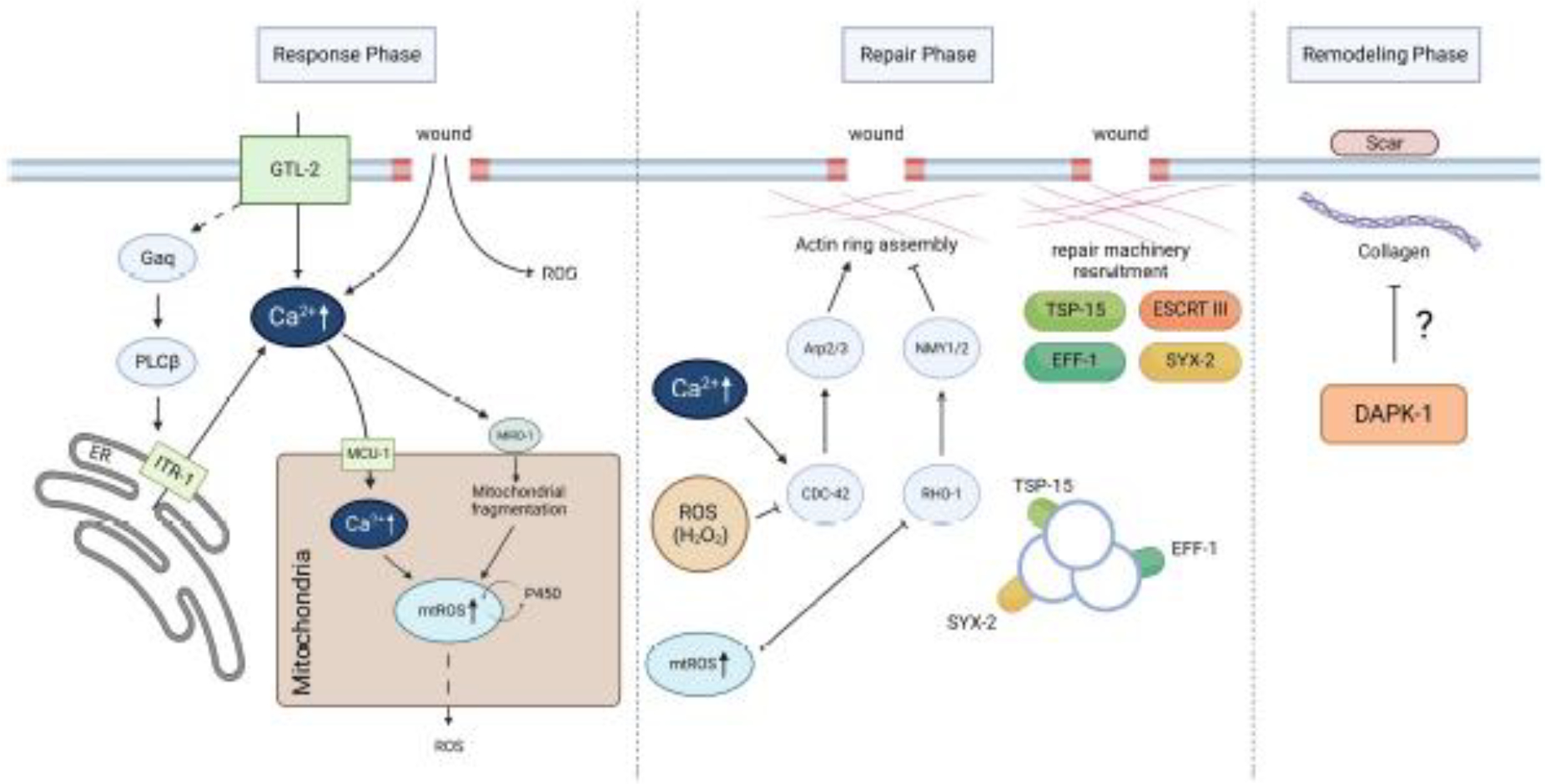

Figure 3. Membrane repair processes in the C. elegans epidermal cell hyp7 after wounding.

The repair process occurs in three stages: early wound response, repair, and remodeling. During the early response phase, signals such as Ca2+ and mitochondrial ROS are produced after PM damage. Later, these signals activate various repair pathways in the repair phase, such as promoting actin ring assembly and recruiting repair machineries, including TSP-15, SYX-2, and EFF-1, to the wound site. Finally, in the remodeling phase, a scar-like structure develops in the cuticle, involving collagen deposition and possibly negatively regulated by DAPK-1.

After a wound occurs, cells can detect various early wound responses that are either directly caused by or secondary to the damage. For example, Ca2+ and ROS are important signals in C. elegans’ epidermal membrane repair. Injury causes an abrupt and prolonged increase in epidermal Ca2+, from extracellular influxes via the TRPM channel GTL-2 on PM and intracellular store release via the IP3 receptor ITR-1 on the endoplasmic reticulum (32). Further genetic analysis reveals that the Gαq (a subtype of G protein) EGL-30 and its effector PLC-EGL-8 function downstream of or concurrently with GTL-2 to facilitate Ca2+ release via ITR-1 after injury. Mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake is also increased through the mitochondrial Ca2+ uniporter (MCU-1), which leads to the subsequent opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP) and mtROS burst. Additionally, cytosolic Ca2+ is essential for triggering Ca2+-sensitive mitochondrial Rho GTPase MIRO-1-dependent mitochondrial fragmentation, which upregulates Cytochrome P450 and mtROS production (102).

These early wound signals alert the cells to repair damage and might deliver information about the wound, such as wound size, to activate appropriate repair mechanisms (103). Ca2+ and ROS signaling regulate actin ring assembly and subsequent recruitment of repair machinery. The elevated cytosolic Ca2+ level triggers actin ring formation at wounds. This process relies on the involvement of small GTPase CDC-42 and Arp2/3 dependent actin polymerization and it is inhibited by RHO-1 and non-muscle myosin in C. elegans (32). On the contrary, this mechanism displays notable disparities in Drosophila and Xenopus, where the actin and non-muscle myosin ring, commonly referred to actomyosin purse string, plays a vital role in driving wound closure (34, 94). In addition, within C. elegans epidermis, wound closure is orchestrated by wounding-induced mitochondrial fragmentation (WIMF) and an mtROS burst, which inhibits the local activation of RHO-1 and enhances the closure (102,104). Furthermore, a locally generated H2O2 signal, originating from the dual oxidase activity on the plasma membrane, exerts a negatively regulatory effect on the clustering of CDC-42 and, consequently, on the process of wound closure. This aligns with the observation of the rapid reduction in H2O2 and the subsequent rise in CDC-42 clustering, which facilitates the actin polymerization at the site of epidermal wounds (105).

The actin cytoskeleton is required for ESCRT-III-dependent recruitment of SYX-2-EFF-1 (73). Fusogen EFF-1 and its regulator SYX-2 are transcriptionally upregulated and recruited to the wound site to promote endoplasmic and exoplasmic membrane repair (73). For ideal wound healing, structures specific to wounds should be removed during the final remodeling phase to restore normal membranes. After C. elegans’ epidermal cell is wounded, scar-like structures can be observed in the cuticles for several days (32, 36). It is worth noting that a mutation in human ortholog death-associated protein kinase (DAPK), known as dapk-1, leads to the development of a large scar structure with various collagen depositions at the head (106). This point mutation of dapk-1 also results in faster wound closure after wounding (107). However, it is still unclear how dapk-1 is responsible for regulating scar formation after wounding, or if there are other mechanisms involved.

2.6. Conserved roles of tetraspanin proteins in repairing damaged membranes

Tetraspanins are membrane proteins that generate tetraspanin-enriched microdomains (TEMs) that regulate PM functions (108). TEMs interact with membrane proteins and lipids and organize supramolecular complexes, influencing cell morphology, motility, invasion, and cell-cell fusion (108). Tetraspanins were also found to be actively involved in the regulation of migrasome formation (109). However, their role in repairing PM damage is not well understood. Yu and our group’s recent independent findings have shed light on the necessity of tetraspanins in repairing large wounds on the PM (74, 110). Based on in vitro mammalian cell culture systems, Yu’s group has described the assembly of TEM, which forms a rigid ring around the damaged site to prevent membrane disintegration and facilitate membrane repair through other mechanisms (110). Our group has found that the tetraspanin protein TSP-15 is recruited to large membrane wounds and forms a ring-like structure in C. elegans epidermal cells, promoting membrane repair after injury (74). Specifically, TSP-15 is recruited from the region underneath the PM adjacent to the wound site in a RAB-5-dependent manner upon membrane damage. ESCRT-III is necessary for recruiting TSP-15 from the early endosome to the damaged membrane. Furthermore, TSP-15 interacts with and is required to accumulate the t-SNARE protein SYX-2, which facilitates membrane repair. These findings, in both C. elegans and mammalian cells, provide valuable insights into the mechanisms that cells use to repair large wounds on the PM. Further research is needed to fully understand the role of tetraspanins in the complex processes involved in membrane repair.

It seems that the mechanism of PM repair in C. elegans epidermal cell is better understood than in mammalian cells undergoing programmed necrosis. Whether some of the mechanisms observed in C. elegans can also be employed by necrotic mammalian cells is still unclear. By combining the description of PM repair mechanisms occurring in cell death and the general PM repair mechanisms in C. elegans in a single manuscript, we hope to initiate an active exploration for two open questions: 1) what are the commonalities and distinctions between general PM pore repair and necrotic pore repair? 2) will any form of PM damage, no matter if generic or cell death associated, in any cell type, be lethal, unless repaired?

3. The immunological significance of necrotic survivors

Identifying necrotic survivors, resulting from a balance between pore-forming and repair mechanisms, has revealed novel insights into the “non-lethal functions” of pore-forming mechanisms. It suggests that the cell death machinery may not solely serve to eliminate cells but could also potentially initiate downstream signaling pathways, depending on whether cells can recognize sub-lethal membrane pores.

A recent study demonstrates the molecular details of how necrotic survivors can detect sub-lethal membrane pores as innate immunity cues (111). As some cells are able to survive necrosis (whether it is necroptosis, pyroptosis, detergent-induced, or perforin-triggered cell death), in that case, these cells can generate a complex signal transduction network by sensing the sub-lethal PM pores. This leads to the production of chemokines and cytokines from the “survivor” cells, such as CXC chemokine ligand (CXCL) -1 -10, -8 (IL-8), and Leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF). Mechanistically, conventional PKCs sense and translocate to the membrane pore-formation sites by detecting the Ca2+ influx from the damage using their C2 domain. Once activated locally, PKCs are auto-phosphorylated at Ser660 and trigger the TAK1/IKKs axis and the activation of RelA/Cux1 transcription complex, crucial for chemokine expression. However, Ca2+ influx or PKC activations are insufficient in chemokine/cytokine inductions. Other changes related to the PM pore-formation are still required. Since this signaling is initiated by recognizing the partial loss of PM integrity, it is referred to as the PM Integrity (PMI) pathway (Figure 4). The discovery of PMI signaling pathway implies that the pore-forming proteins, in addition to their roles in cellular killing, may have another function in activating a signaling pathway, which leads to immune modulations (chemokines and cytokines). Therefore, the loss of PM integrity represents a cell-identifiable innate immune activation pattern, with Ser660 p-PKCs acting as pattern recognition receptors.

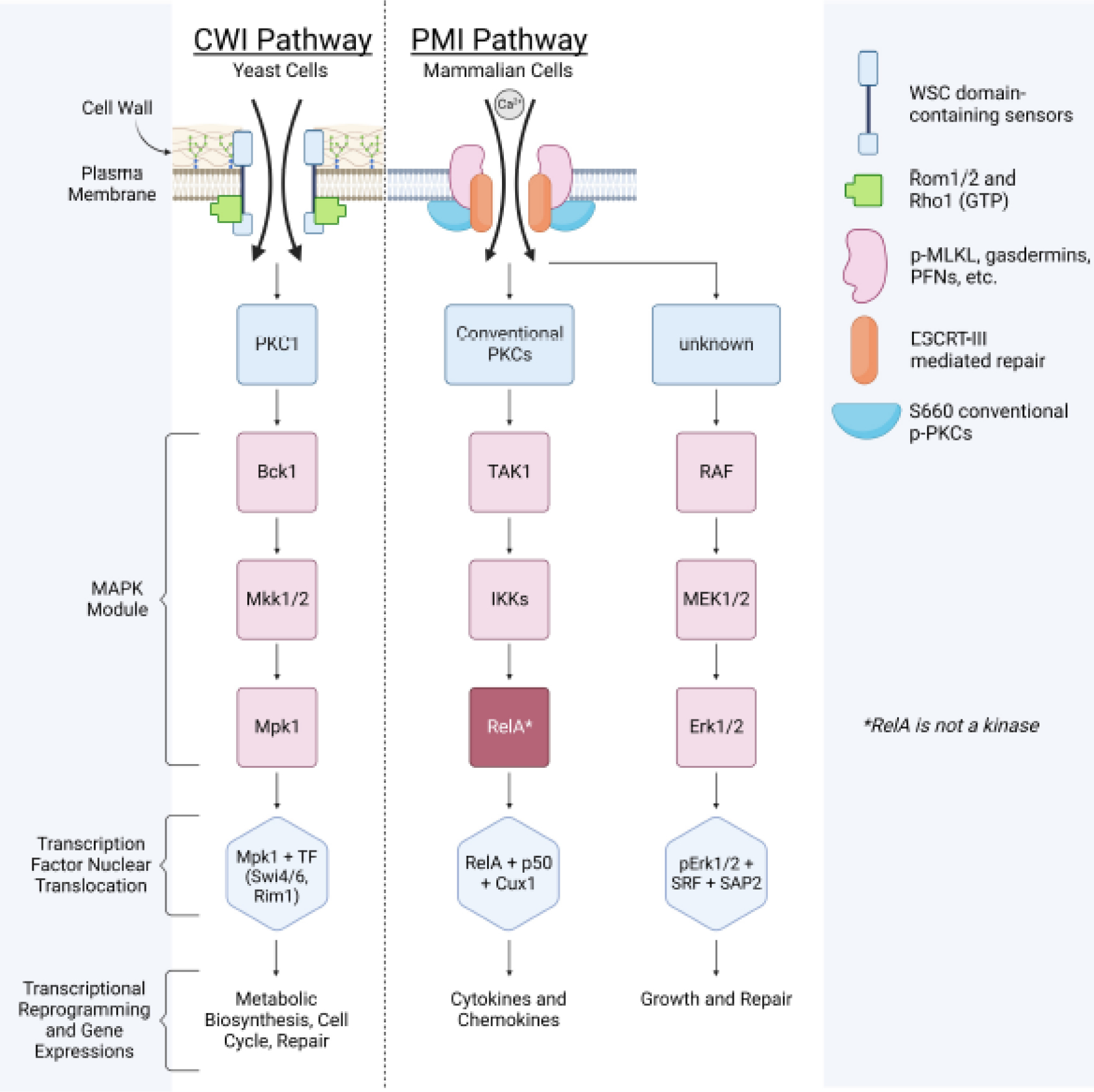

Figure 4. Side-by-side comparison of the yeast CWI pathway and mammalian PMI pathway.

It shows cellular barrier damage sensing and repair is an evolutionarily conserved mechanism.

In addition to chemokine/cytokine productions, the PMI pathway also has another branch (Figure 4), which leads to the expression of several transcription factors, such as Egr1, Fos, and Fosb, functioning in cell growth, proliferation, and PM repair (111). Although the sensor(s) activating this branch has not been identified (Ser660 p-PKCs are only responsible for chemokine/cytokines), it is known to be mediated by MAPK cascades and the transcription factor SRF/SAP2.

Note that at the molecular level, the PMI-sensing pathway shares similarities with the well-established yeast cell wall integrity (CWI) signaling pathway (Figure 4) (112). While the final gene expression outputs differ between CWI and PMI, both pathways utilize PKC kinase cascades to transmit signals. This suggests that the mechanisms for recognizing cell barrier integrity and transmitting signals are evolutionarily conserved. In yeast, the CWI pathway is initiated by transmembrane proteins Wsc1-3, Mid2, and Mtl1. The Wsc1-3 sensors contain a unique N-terminal domain, the cysteine-rich WSC domain (113). This domain architecture is also present in human polycystin 1 (PKD1), which consists of a voltage-gated ion channel fold and interacts with PKD2 to form a domain-swapped, yet noncanonical, transient receptor potential channel architecture (114, 115). This channel can function as a cation channel, including inward Ca2+ conductance (114, 115). Although it has not yet been tested, the PKD1-2 cation channel may be involved in mammalian PMI initiation or membrane repair.

The discovery of the PMI pathway also fits into the recent ideas Rothlin and colleagues proposed about the “effector responses of cell death” in specific physiological and pathological contexts (116). They noticed that the biological consequences of cell death, referred to as “effector response ,” can range from induction of an immune response to tissue renewal and repair, development, morphogenesis, and homeostasis. It seems that “the number of types of cell death is fewer than the number of unique effector responses.” Hence, they proposed that cell death responses are NOT a “one-to-one relationship” between a “specific type of cell death” and “its corresponding effector response .” Their theory is that “the variety of cell death types (factor 1, )”, plus the multitude of accompanying “microenvironmental signals (factor 2, )” and their integration by “different phagocytes that engulf the dying/dead cells, also known as efferocytes (factor 3, )” together, execute a specific “effector response ().” This is saying the same cell death modality can result in distinct, even opposite, effector functions, depending on the specificity of microenvironments and efferocytosis. This concept can be summarized in equation 1.1 below.

| (1.1) |

where a type of ‘cell death,’ a type of ‘environments of cell death,’ and a type of ‘specific efferocyte’ give rise to a unique type of ‘effector response’ .

This mathematical model for “effector responses” to cell death can potentially fit into several physiological scenarios. For example, apoptotic intestinal epithelial cells (“”) can be engulfed by either dendritic cells or macrophages (“”). The macrophage (“”) increases the expression of genes associated with phagosome maturation, lipid metabolism, and branched-chain amino acid catabolism (“”), while dendritic cells (“”) upregulate genes involved in the recruitment and proliferation of regulatory T (Treg) cells, as well as CC-chemokine receptor 7 (CCR7) (“”) (117). Another example highlights the ability of macrophages (“”) to initiate tissue repair (“”) when exposed to IL-4 (“”) in conjunction with apoptotic cells (“”). Notably, this reparative response does not occur only with IL-4 or apoptotic cells alone (118).

Here, we expand this theory by integrating a time variable to better reflect the reversibility of such cell death response and outcome. A dying necrotic cell, due to the counterbalance work from the various repair mechanisms, can have a chance (time before final cell lysis “”) to produce immune modulators via the membrane pore sensing and the downstream PMI signaling. We simplify this idea in equation (2.1) below.

| (2.1) |

where time of survival (pore-forming ≤ repair),

the immunomodulator production, secretion, and degradation dynamics over time, and a specific immunomodulator

Considering the arrays of all immune modulators a certain cell can make and counting all the cells in microenvironments, the matrix (1.2) below illustrates how dying cells can shape the “microenvironmental signals (factor 2, )”.

| (1.2) |

where individual cell in the microenvironments = a specific immunomodulator (defined by equation 2.1)

Thus, after using the matrix in (1.2) to replace the “” variable from (1.1), the “effector response ” can now be visualized as below (1.3).

| (1.3) |

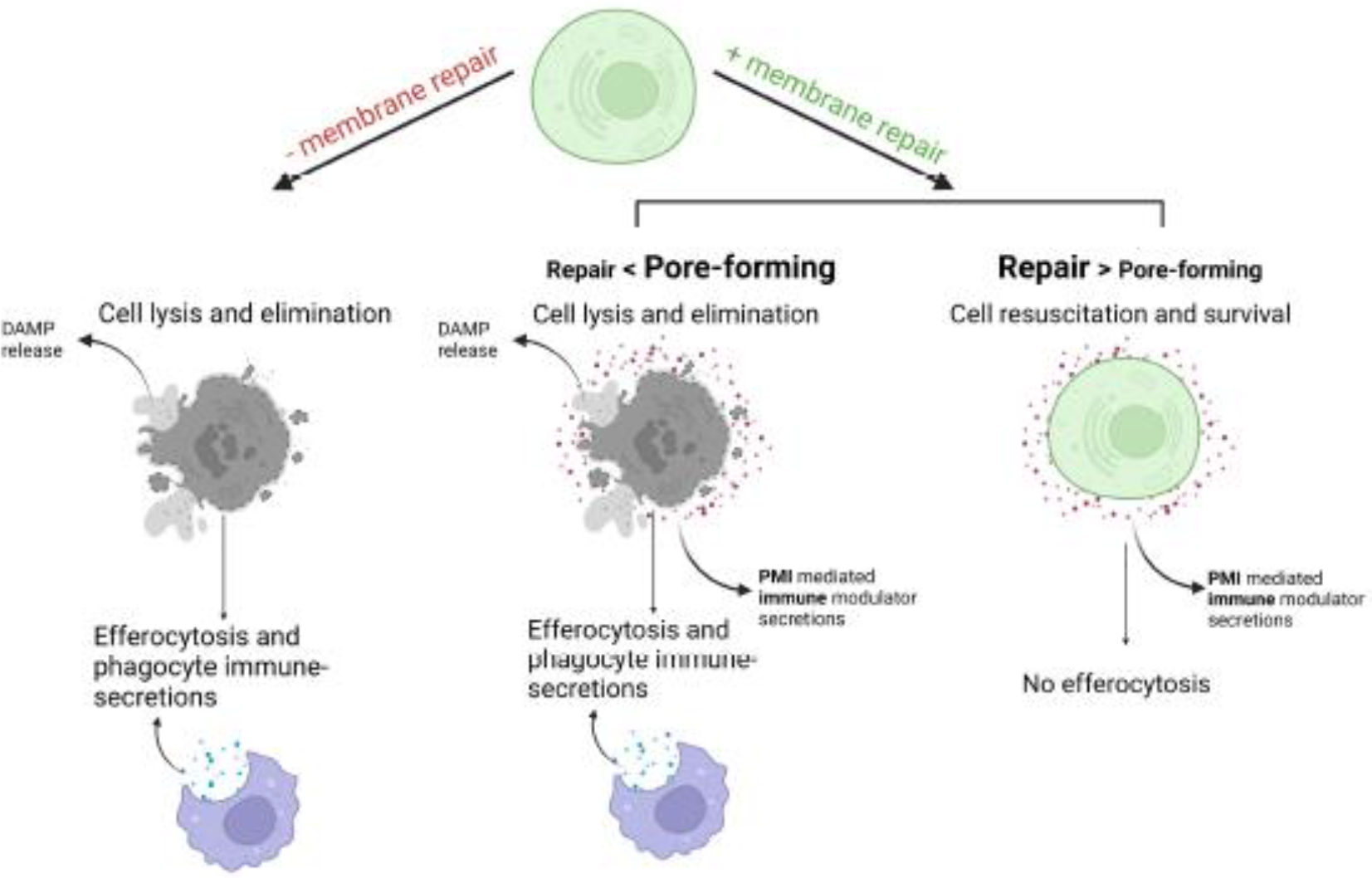

In the absence of repair mechanisms, dying cells are unable to survive (“”), which can limit the production of immune modulators . Thus, if a cell dies (“”) without membrane repair, it can affect the (“”) factor mainly via DAMP release; and the phagocytes can further change the (“”) by phagocytic/efferocytotic secretions (“”). However, equipped with membrane repair, the dying/dead cells (“”) can now make PMI products further to alter the (“”) factor, in addition to the DAMP release and the efferocytosis (“”). If the repair activity can overwhelm the pore-forming activity, in that case, cells may survive and avoid the interactions with phagocytes but could still modulate the (“”) factor by PMI-mediated secretions without cell lysis (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Membrane repair and the PMI pathway influence the effector responses of cell death.

Cells without PM repair mechanisms die rapidly, limiting PMI-mediated immune modulator production, while they can still affect “” with DAMP release and by efferocytosis. On the other hand, membrane repair allows cells time “”, to make PMI products to alter the environment “” in addition to DAMP release and efferocytosis. If repair is successful, cells can survive but still modify “” with PMI-related secretion, bypassing phagocytes’ engulfment.

The mathematical model proposed here is an abstractive way to summarize the biological effects of the PMI pathway — the surviving cells will contribute to changes in the cytokine environment and dynamics, depending on the status of their membrane repair, visualized as (2.1). Given that this model is a reductionistic method to describe the microenvironments surrounding dying cells, several other critical variables that may contribute to the complexity of the effector response of cell death are still missing, such as cell-cell contacts and cytokine diffusion patterns. We expect this formula to be significantly expanded as more information is provided from emerging spatial and single-cell approaches. With continuous incorporations of other biological variables, the hope is that one day we can use a mathematical formula to describe a comprehensive physical process at the molecular level.

We also propose some possible scenarios this formula could be possibly applied to. One such case is in late-stage solid tumors. Some tumors may develop mechanisms evading apoptosis and partially inhibiting caspase-8, allowing necroptotic signaling activation under certain conditions (119). Moreover, in the tumor microenvironment, glucose deprivation can induce mtDNA release into the cytosol, activating DNA-dependent activator of IFN-regulatory factors (DAI, or ZBP-1) to engage RIPK3 and MLKL for necroptosis (120). In addition, there is often a gradual reduction in RIPK3 expression during tumor growth (121, 122). As a result, in late-stage tumors, MLKL may only be partially phosphorylated. In these tumors, cells may tolerate low levels of pMLKL (due to incomplete activation), survive, and produce chemokines/cytokines via PMI signaling. Incomplete MLKL phosphorylation induced by the mtDNA-DAI pathway described above has indeed been observed in several late-stage tumors (61). Moreover, pMLKL+ cells were co-stained with IL-8, a pro-tumor cytokine, in several stage-IV pancreatic and breast cancer patient biopsies (111). Although WT and MLKL KO MVT-1 tumors (an animal model for breast cancer) grew similarly at the primary implantation sites (mammary fat pads), MLKL KO almost abolished lung metastases. It is possible to speculate that pMLKL in dying MVT-1 tumor cells (“”) promotes tumorigenesis by engaging the PMI pathway and the consequent pro-tumor chemokine/cytokine secretions (such as IL-8, “”) to shape a pro-tumor “effector response ().”

As discussed above, another pathological scenario where cells exhibit pMLKL positivity without undergoing cell lysis is in the case of post-kidney transplantation/ischemia-reperfusion injury (IRI) stress (in some cases, exceeding 80%, “”) (14). By re-analyzing microarray, RNA-seq, and snRNA-seq data from both mouse models and human kidney samples undergoing ischemia-reperfusion stress, higher CXCL1, CXCL8, CXCL2, and LIF expressions (“”) in post-procedure samples were identified, suggesting a correlation between sub-lethal PM damage and PMI signaling (111). How the PMI pathway influences the outcomes of the transplant post-IRI stress is still unclear (“”).

Since PMI signaling activation leads to the productions of chemokines and cytokines, it can also play vital roles in macrophage migrations toward the dead and/or dying cells (“”) (111). Macrophage migration can be tested in a transwell assay. During this assay, macrophages are placed on the upper layer of a permeable membrane, while the supernatants from the dying cells are placed below the cell permeable membrane. Following an overnight incubation, the macrophages that have migrated through the membrane are stained and counted. Data from this assay showed that supernatants from membrane-damaged cells lacking a PMI pathway could not attract macrophages (“”) migration. CXCL1 supplementation (“”), but not LIF, could largely rescue the phenotype of PMI deficiency. These findings indicated that PMI chemokine productions, including CXCL1, can facilitate macrophage movements toward dying cells. Meanwhile, the components released passively from dead cells (e.g., DAMPs) alone were insufficient to promote this migration.

Furthermore, the role of PMI signaling in triggering peritonitis and inflammation (“”) has been confirmed using a mouse model for sterile peritonitis induced by intraperitoneal injection of dying cells (“”) (111, 123). This model demonstrated that the peritonitis, identified by massive peritoneal cavity infiltration of monocytes, macrophages, dendritic cells, and neutrophils (“”), could only be induced when injected dying cells could produce PMI-related cytokines/chemokines. Furthermore, macrophages and monocytes recruited by PMI-competent dying cells exhibited lower levels of M2 polarity markers (usually anti-inflammatory macrophages), such as CD163 and CD206 (“”), indicating an overall inflammatory environment.

The PMI pathway could also explain why dying necroptotic cells with ESCRT-III deficiency (via CHMP4B silencing) elicited less CD8 T cell cross-priming activity (“”) (14). Given that ESCRT-III deficient cells lacked maximal PMI productions (111), they couldn’t create an optimized niche (“”) for dendritic cells (“”) to cross-prime. However, it is worth noting that although both ESCRT-III and PMI signaling are directly connected to PM pore formation and guided by the Ca2+ influx through the membrane pores, no evidence has been observed to support a direct molecular link between these two pathways.

Altogether, these findings expand our understanding of the impacts of PM integrity loss on the immune system, highlighting how PM pore formation can act as a universal pattern for innate immune modulations.

Conclusion Remarks

Although cell death has been identified for decades, the biological effects of a dying or dead cell on its microenvironments are still not fully understood. The identification of PM repair pathways and the existence of necrotic survivors add another level of complexity. Various models such as budding yeast, C. elegans, in vitro cell culture, mammalian, and human samples have already been heavily employed to answer this question. Nonetheless, we want to emphasize the value of employing small and straightforward in vivo models like C. elegans to study PM repair for several reasons. Firstly, simple models can reveal the most basic and evolutionary conserved players and processes in wound healing. Conserved repair mechanisms have been identified in species from invertebrates to mammals (3). Secondly, these conserved mechanisms are observed across species and between PM repair and other biological processes. For example, the actomyosin rings beneath the damaged membrane are remarkably similar to those involved in cytokinesis (124). Additionally, dorsal closure resembles multicellular wound closure and has been used as a repair model in Drosophila (125). The powerful worm genetics could allow us to identify more repair machinery in PM repair and remodeling. Thirdly, in vivo models are essential for studying cell type-specific adaptations in PM repair. Although the basic mechanism is conserved, cell type-specific adaptations in healing have been observed (4). For instance, microvilli expulsion from the apical side of intestinal epithelial cells is observed in C. elegans after a bacterial PFT attack (126). The difference in environment and damage, as well as the difference in cell structure and gene expression, lead to cell type-specific adaptations. Furthermore, cellular crosstalk may also happen in PM repair process, as in multiple-cellular wound repair context. In vivo models integrate PM repair with the tissue environment and surrounding cells, providing a comprehensive understanding of the process.

The idea of using diverse species on the phylogenetic tree to study PM repair goes back to what we have stated at the beginning — Since the first cells, PM has served as the essential barriers for segregation and the sensors for various perturbations.

Table 1.

Lists of abbreviations in this paper

| Accidental cell death | ACD |

| Apoptosis-linked gene 2 | ALG-2 |

| ALG-2-interacting protein X | ALIX |

| Alzheimer’s disease | AD |

| Acute myeloid leukemia | AML |

| Acute respiratory distress syndrome | ARDS |

| Acid sphingomyelinase | ASM |

| Candida albicans | C. albicans |

| Caenorhabditis elegans | C. elegans |

| Cell division control protein 42 | CDC-42 |

| Charged multivesicular body protein 4b | CHAM4B |

| Cell wall integrity | CWI |

| CXC chemokine ligand | CXCL |

| DNA-dependent activator of interferon-regulatory factors | DAI |

| Danger-associated molecular pattern | DAMP |

| Death-associated protein kinase | DAPK-1 |

| Epithelial fusion failure 1 | EFF-1 |

| Endosomal Sorting Complex Required for Protein Transport | ESCRT |

| FK506 binding protein | FKBP |

| Gtpase Regulator Associated with Focal Adhesion Kinase 1 | GRAF1 |

| Gasdermin D | GSDMD |

| Gon-two like 2 | GTL-2 |

| Inositol trisphosphate | IP3 |

| ischemia-reperfusion injury | IRI |

| Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor 1 | ITR-1 |

| Leukemia inhibitory factor | LIF |

| Lipopolysaccharide | LPS |

| Membrane attack complex/perforin | MACPF |

| Muscular dystrophy | MD |

| Mitsugumin 53 | MG53 |

| Mixed lineage kinase domain-like | MLKL |

| Mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization | MOMP |

| Mitochondrial permeability transition pore | mPTP |

| Multivesicular body | MVB |

| Myc/vegf tumor | MVT |

| Natural killer | NK |

| Necro sulfonamide | NSA |

| Programmed cell death | PCD |

| Pore-forming toxin | PFT |

| Protein kinase C | PKC |

| Polycystin | PKD |

| Plasma membrane | PM |

| Plasma membrane integrity | PMI |

| Ras-associated binding protein 5 | RAB-5 |

| Regulated cell death | RCD |

| Rhodopsin 1 | RHO-1 |

| Receptor-interacting protein kinase 1 | RIPK1 |

| Receptor-interacting protein kinase 3 | RIPK3 |

| Reactive oxygen species | ROS |

| Syntaxin-2 | SYX-2 |

| Tetraspanin-enriched microdomain | TEM |

| Regulatory T | Treg |

| Transient receptor potential | TRP |

| Transient receptor potential melastatin | TRPM |

| Tetraspanin 15 | TSP-15 |

| Voltage-gated ion channel | VGIC |

| Vacuolar protein sorting-associated protein | VPS |

| Cell wall stress-responsive component | WSC |

| Wild-type | WT |

Acknowledgments

This study was generously supported by start-up funding from Hillman Cancer Center (YNG) and in part by award number P30CA047904 and DP2GM146320 from the National Institutes of Health (YNG). This work was also supported in part by the National Key R&D Program of China (2021YFA1300302, 2021YFA1101002), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31972891), and the Zhejiang Province Natural Science Foundation (LR21C120002) to SX. We thank Yuanyuan Song (Univ. of Alabama) for the mathematical inputs.

Footnotes

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain

Reference

- 1.Gong YN, Crawford JC, Heckmann BL, Green DR. To the edge of cell death and back. FEBS J. 2019;286(3):430–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhen Y, Radulovic M, Vietri M, Stenmark H. Sealing holes in cellular membranes. Embo J. 2021;40:e106922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dias C, Nylandsted J. Plasma membrane integrity in health and disease: significance and therapeutic potential. Cell Discovery. 2021;7(1):4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ammendolia DA, Bement WM, Brumell JH. Plasma membrane integrity: implications for health and disease. BMC Biology. 2021;19(1):71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andrews NW, Corrotte M. Plasma membrane repair. Curr Biol. 2018;28(8):R392–R7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Galluzzi L, Vitale I, Aaronson SA, Abrams JM, Adam D, Agostinis P, et al. Molecular mechanisms of cell death: recommendations of the Nomenclature Committee on Cell Death 2018. Cell Death Differ. 2018;25(3):486–541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sun G, Montell DJ. Q&A: Cellular near death experiences-what is anastasis? BMC Biol. 2017;15(1):92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ding AX, Sun G, Argaw YG, Wong JO, Easwaran S, Montell DJ. CasExpress reveals widespread and diverse patterns of cell survival of caspase-3 activation during development in vivo. Elife. 2016;5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tait SW, Parsons MJ, Llambi F, Bouchier-Hayes L, Connell S, Munoz-Pinedo C, et al. Resistance to caspase-independent cell death requires persistence of intact mitochondria. Dev Cell. 2010;18(5):802–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reddien PW, Cameron S, Horvitz HR. Phagocytosis promotes programmed cell death in C. elegans. Nature. 2001;412(6843):198–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sun G, Guzman E, Balasanyan V, Conner CM, Wong K, Zhou HR, et al. A molecular signature for anastasis, recovery from the brink of apoptotic cell death. J Cell Biol. 2017;216(10):3355–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sun G, Ding XA, Argaw Y, Guo X, Montell DJ. Akt1 and dCIZ1 promote cell survival from apoptotic caspase activation during regeneration and oncogenic overgrowth. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):5726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jimenez AJ, Maiuri P, Lafaurie-Janvore J, Divoux S, Piel M, Perez F. ESCRT machinery is required for plasma membrane repair. Science. 2014;343(6174):1247136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gong YN, Guy C, Olauson H, Becker JU, Yang M, Fitzgerald P, et al. ESCRT-III Acts Downstream of MLKL to Regulate Necroptotic Cell Death and Its Consequences. Cell. 2017;169(2):286–300 e16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Linkermann A, Green DR. Necroptosis. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(5):455–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang H, Sun L, Su L, Rizo J, Liu L, Wang LF, et al. Mixed lineage kinase domain-like protein MLKL causes necrotic membrane disruption upon phosphorylation by RIP3. Mol Cell. 2014;54(1):133–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sun L, Wang H, Wang Z, He S, Chen S, Liao D, et al. Mixed lineage kinase domain-like protein mediates necrosis signaling downstream of RIP3 kinase. Cell. 2012;148(1–2):213–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shi J, Gao W, Shao F. Pyroptosis: Gasdermin-Mediated Programmed Necrotic Cell Death. Trends Biochem Sci. 2017;42(4):245–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ruhl S, Broz P. Regulation of Lytic and Non-Lytic Functions of Gasdermin Pores. J Mol Biol. 2022;434(4):167246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ruhl S, Shkarina K, Demarco B, Heilig R, Santos JC, Broz P. ESCRT-dependent membrane repair negatively regulates pyroptosis downstream of GSDMD activation. Science. 2018;362(6417):956–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shi J, Zhao Y, Wang Y, Gao W, Ding J, Li P, et al. Inflammatory caspases are innate immune receptors for intracellular LPS. Nature. 2014;514(7521):187–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shkarina K, Hasel de Carvalho E, Santos JC, Ramos S, Leptin M, Broz P. Optogenetic activators of apoptosis, necroptosis, and pyroptosis. J Cell Biol. 2022;221(6). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Santa Cruz Garcia AB, Schnur KP, Malik AB, Mo GCH. Gasdermin D pores are dynamically regulated by local phosphoinositide circuitry. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1):52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dai E, Meng L, Kang R, Wang X, Tang D. ESCRT-III-dependent membrane repair blocks ferroptosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2020;522(2):415–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pedrera L, Espiritu RA, Ros U, Weber J, Schmitt A, Stroh J, et al. Ferroptotic pores induce Ca(2+) fluxes and ESCRT-III activation to modulate cell death kinetics. Cell Death Differ. 2021;28(5):1644–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ruan J, Xia S, Liu X, Lieberman J, Wu H. Cryo-EM structure of the gasdermin A3 membrane pore. Nature. 2018;557(7703):62–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ritter AT, Shtengel G, Xu CS, Weigel A, Hoffman DP, Freeman M, et al. ESCRT-mediated membrane repair protects tumor-derived cells against T cell attack. Science. 2022;376(6591):377–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nozaki K, Maltez VI, Rayamajhi M, Tubbs AL, Mitchell JE, Lacey CA, et al. Caspase-7 activates ASM to repair gasdermin and perforin pores. Nature. 2022;606(7916):960–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Perez R, Davis SC. Relevance of animal models for wound healing. Wounds. 2008;20(1):3–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bement WM, Mandato CA, Kirsch MN. Wound-induced assembly and closure of an actomyosin purse string in Xenopus oocytes. Current Biology. 1999;9(11):579–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Abreu-Blanco MT, Verboon JM, Parkhurst SM. Cell wound repair in Drosophila occurs through three distinct phases of membrane and cytoskeletal remodeling. Journal of Cell Biology. 2011;193(3):455–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xu S, Chisholm AD. A Gαq-Ca2+ signaling pathway promotes actin-mediated epidermal wound closure in C. elegans. Current biology: CB. 2011;21(23):1960–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Galko MJ, Krasnow MA. Cellular and genetic analysis of wound healing in Drosophila larvae. PLoS biology. 2004;2(8):E239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xu S, Hsiao TI, Chisholm AD. The wounded worm: Using C. elegans to understand the molecular basis of skin wound healing. Worm. 2012;1(2):134–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ma Y, Xie J, Wijaya CS, Xu S. From wound response to repair - lessons from C. elegans. Cell Regeneration. 2021;10(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pujol N, Cypowyj S, Ziegler K, Millet A, Astrain A, Goncharov A, et al. Distinct innate immune responses to infection and wounding in the C. elegans epidermis. Current biology: CB. 2008;18(7):481–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yanik MF, Cinar H, Cinar HN, Chisholm AD, Jin Y, Ben-Yakar A. Neurosurgery: functional regeneration after laser axotomy. Nature. 2004;432(7019):822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Meng X, Wijaya CS, Shao Q, Xu S. Triggered Golgi membrane enrichment promotes PtdIns(4,5)P2 generation for plasma membrane repair. J Cell Biol. 2023;222(8). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wijaya CS, Meng X, Yang Q, Xu S. Protocol to Induce Wounding and Measure Membrane Repair in Caenorhabditis elegans Epidermis. STAR Protocols. 2020;1(3):100175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Taffoni C, Omi S, Huber C, Mailfert S, Fallet M, Rupprecht JF, et al. Microtubule plus-end dynamics link wound repair to the innate immune response. Elife. 2020;9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xu S, Li S, Bjorklund M, Xu S. Mitochondrial fragmentation and ROS signaling in wound response and repair. Cell Regen. 2022;11(1):38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McNeil PL, Steinhardt RA. Plasma Membrane Disruption: Repair, Prevention, Adaptation. Annual Review of Cell and Developmental Biology. 2003;19(1):697–731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jimenez AJ, Perez F. Plasma membrane repair: the adaptable cell life-insurance. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2017;47:99–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lo HP, Nixon SJ, Hall TE, Cowling BS, Ferguson C, Morgan GP, et al. The caveolin-cavin system plays a conserved and critical role in mechanoprotection of skeletal muscle. The Journal of Cell Biology. 2015;210(5):833–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Petrof BJ, Shrager JB, Stedman HH, Kelly AM, Sweeney HL. Dystrophin protects the sarcolemma from stresses developed during muscle contraction. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1993;90(8):3710–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Clarke MSF, Caldwell RW, Chiao H, Miyake K, McNeil PL. Contraction-Induced Cell Wounding and Release of Fibroblast Growth Factor in Heart. Circulation Research. 1995;76(6):927–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McNeil PL, Khakee R. Disruptions of muscle fiber plasma membranes. Role in exercise-induced damage. Am J Pathol. 1992;140(5):1097–109. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dudkina NV, Spicer BA, Reboul CF, Conroy PJ, Lukoyanova N, Elmlund H, et al. Structure of the poly-C9 component of the complement membrane attack complex. Nature Communications. 2016;7:10588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Keefe D, Shi L, Feske S, Massol R, Navarro F, Kirchhausen T, et al. Perforin Triggers a Plasma Membrane-Repair Response that Facilitates CTL Induction of Apoptosis. Immunity. 2005;23(3):249–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cooper ST, McNeil PL. Membrane Repair: Mechanisms and Pathophysiology. Physiol Rev. 2015;95(4):1205–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bansal D, Miyake K, Vogel SS, Groh S, Chen C-C, Williamson R, et al. Defective membrane repair in dysferlin-deficient muscular dystrophy. Nature. 2003;423(6936):168–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Richard I, Broux O, Allamand V, Fougerousse F, Chiannilkulchai N, Bourg N, et al. Mutations in the proteolytic enzyme calpain 3 cause limb-girdle muscular dystrophy type 2A. Cell. 1995;81(1):27–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bharadwaj P, Solomon T, Malajczuk CJ, Mancera RL, Howard M, Arrigan DWM, et al. Role of the cell membrane interface in modulating production and uptake of Alzheimer’s beta amyloid protein. Biochim Biophys Acta Biomembr. 2018;1860(9):1639–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shrivastava AN, Aperia A, Melki R, Triller A. Physico-Pathologic Mechanisms Involved in Neurodegeneration: Misfolded Protein-Plasma Membrane Interactions. Neuron. 2017;95(1):33–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cong X, Hubmayr RD, Li C, Zhao X. Plasma membrane wounding and repair in pulmonary diseases. American Journal of Physiology-Lung Cellular and Molecular Physiology. 2017;312(3):L371–L91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Oeckler RA, Hubmayr RD. Ventilator-associated lung injury: a search for better therapeutic targets. Eur Respir J. 2007;30(6):1216–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chen H, Fang Y, Wu J, Chen H, Zou Z, Zhang X, et al. RIPK3-MLKL-mediated necroinflammation contributes to AKI progression to CKD. Cell Death Dis. 2018;9(9):878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gong YN, Guy C, Crawford JC, Green DR. Biological events and molecular signaling following MLKL activation during necroptosis. Cell Cycle. 2017;16(19):1748–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Montalban-Bravo G, Class CA, Ganan-Gomez I, Kanagal-Shamanna R, Sasaki K, Richard-Carpentier G, et al. Transcriptomic analysis implicates necroptosis in disease progression and prognosis in myelodysplastic syndromes. Leukemia. 2020;34(3):872–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Xin J, You D, Breslin P, Li J, Zhang J, Wei W, et al. Sensitizing acute myeloid leukemia cells to induced differentiation by inhibiting the RIP1/RIP3 pathway. Leukemia. 2017;31(5):1154–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jiao D, Cai Z, Choksi S, Ma D, Choe M, Kwon HJ, et al. Necroptosis of tumor cells leads to tumor necrosis and promotes tumor metastasis. Cell Res. 2018;28(8):868–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Li Z, Mo F, Wang Y, Li W, Chen Y, Liu J, et al. Enhancing Gasdermin-induced tumor pyroptosis through preventing ESCRT-dependent cell membrane repair augments antitumor immune response. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1):6321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wang Y, Serfass L, Roy MO, Wong J, Bonneau AM, Georges E. Annexin-I expression modulates drug resistance in tumor cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;314(2):565–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mussunoor S, Murray GI. The role of annexins in tumour development and progression. J Pathol. 2008;216(2):131–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Westman J, Plumb J, Licht A, Yang M, Allert S, Naglik JR, et al. Calcium-dependent ESCRT recruitment and lysosome exocytosis maintain epithelial integrity during Candida albicans invasion. Cell Rep. 2022;38(1):110187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.McCullough J, Frost A, Sundquist WI. Structures, Functions, and Dynamics of ESCRT-III/Vps4 Membrane Remodeling and Fission Complexes. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2018;34:85–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Schoneberg J, Lee IH, Iwasa JH, Hurley JH. Reverse-topology membrane scission by the ESCRT proteins. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2017;18(1):5–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Vietri M, Radulovic M, Stenmark H. The many functions of ESCRTs. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology. 2020;21(1):25–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Scheffer LL, Sreetama SC, Sharma N, Medikayala S, Brown KJ, Defour A, et al. Mechanism of Ca2+-triggered ESCRT assembly and regulation of cell membrane repair. Nature communications. 2014;5:5646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Vandenabeele P, Riquet F, Cappe B. Necroptosis: (Last) Message in a Bubble. Immunity. 2017;47(1):1–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Fan W, Guo J, Gao B, Zhang W, Ling L, Xu T, et al. Flotillin-mediated endocytosis and ALIX-syntenin-1-mediated exocytosis protect the cell membrane from damage caused by necroptosis. Sci Signal. 2019;12(583). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yoon S, Kovalenko A, Bogdanov K, Wallach D. MLKL, the Protein that Mediates Necroptosis, Also Regulates Endosomal Trafficking and Extracellular Vesicle Generation. Immunity. 2017;47(1):51–65 e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Meng X, Yang Q, Yu X, Zhou J, Ren X, Zhou Y, et al. Actin Polymerization and ESCRT Trigger Recruitment of the Fusogens Syntaxin-2 and EFF-1 to Promote Membrane Repair in C. elegans. Dev Cell. 2020;54(5):624–38.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wang Y, Yang Q, Meng X, Wijaya C, Ren X, Xu S. Recruitment of tetraspanin TSP-15 to epidermal wounds promotes plasma membrane repair in C. elegans. Dev Cell. 2022;57(13):12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tam C, Idone V, Devlin C, Fernandes MC, Flannery A, He X, et al. Exocytosis of acid sphingomyelinase by wounded cells promotes endocytosis and plasma membrane repair. The Journal of Cell Biology. 2010;189(6):1027–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Gutierrez MG, Saka HA, Chinen I, Zoppino FCM, Yoshimori T, Bocco JL, et al. Protective role of autophagy against Vibrio cholerae cytolysin, a pore-forming toxin from V. cholerae. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104(6):1829–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]