Purpose and appropriate samples

This 26-parameter flow cytometry panel has been developed and optimized to analyze NK cell phenotype, using cryopreserved peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from people living with and without human immunodeficiency virus (PLWH, PWOH). Our panel is designed for the analysis of several parameters of total NK cells and memory NK cell subsets including markers of maturation, activation, and proliferation, as well as activating and inhibitory receptors. Other tissues have not been tested (Table 1).

Background

Natural killer (NK) cells are components of the innate immune system. They are comparable to T cells, in particular CD8 T cells[1], serving both as cytotoxic effector cells and playing a crucial role in anti-viral and anti-tumor immune responses. However, they differ in recognition, specificity, and memory mechanisms. CD8 T cells use their T cell antigen receptor to recognize the peptide-major histocompatibility complex on the surface of the antigen presenting cells, and subsequently trigger their activation, differentiation, and function. NK cells on the other hand can perform rapid cytolytic and immunomodulatory functions in the absence of prior sensitization. Once activated, NK cells can help clear virus-infected or tumor cells through multiple mechanisms including direct cytotoxicity by releasing perforin, granzyme, immunoregulatory cytokines, and chemokines, or indirectly by influencing adaptive immune responses through their crosstalk with T and dendritic cells[2–6].

NK cell functional activity is tightly regulated by an array of germline encoded activating and inhibitory receptors. A balance between these receptors determines NK cell activation and responses to alterations due to stress, infections, and cancer. After viral infections, individuals exhibit a reconfiguration of the NK cell receptor repertoire, in particular, an up-regulation of the activating receptor NKG2C and a down-regulation of the inhibitory receptor Siglec-7[7].

We have designed a 24-color high-dimensional flow cytometry panel (Table 2) that allows us to perform a deep phenotypic analysis of human NK cells. These are defined by the expression of the adhesion molecule CD56 (NCAM-1) and the Fc receptor CD16 (FcγRIIIa), which mediates antibody dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC). Peripheral blood NK cells are mostly mature and cytotoxic and are identified from the lineage-negative cells (CD3− CD19− CD33−) as CD56dim. A smaller proportion of NK cells known as immature or early CD56bright (Figure 1A) produces more cytokines and chemokines than mature CD56dim NK cells and are considered their precursors[8]. A third subset is the dysfunctional CD56neg NK cell, a cell subtype that lack the expression of CD56 (Figure 1A), have a reduced cytotoxicity, and expand in chronic HIV, Cytomegalovirus (CMV) and Epstein-Barr virus infections[9, 10].

Table 2.

Reagents used for OMIP

| MARKER | FLUOROCHROME | ANTIBODY CLONE | PURPOSE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Live/dead | Aqua | Viability Marker | |

| CD33 | BV786 | WM53 | Non-NK cell lineage exclusion |

| CD19 | BV786 | SJ25C1 | Non-NK cell lineage exclusion |

| CD3 | BV786 | UCHT1 | Non-NK cell lineage exclusion |

| CD16 | BUV496 | 3G8 | NK cell subset |

| CD56 | BUV563 | B159 | NK cell subset |

| FcεRIγ | FITC | NP_004097 | NK Cell subset |

| CD158a/h/g (KIR2DL1/S1/S3/S5) | PerCP-Cy5.5 | HP-MA4 | Inhibitory Receptors |

| CD158e1 (KIR3DL1) | PerCP-Cy5.5 | DX9 | Inhibitory Receptors |

| CD328 (Siglec-7) | APC-Vio770 | REA214 | Inhibitory Receptors |

| KLRG1 | BV421 | SA231A2 | Inhibitory Receptors |

| ILT2 | BUV615 | GHI/75 | Inhibitory Receptors |

| NKG2A (CD159a) | PE-Vio770 | REA110 | Inhibitory Receptors |

| CD94 | BUV805 | HP-3D9 | Activating/inhibitory Receptors |

| NKG2C | PE-Vio615 | REA205 | Activating Receptors |

| NKG2D | BB790-P | 1D11 | Activating Receptors |

| NKp30 | R718 | p30–15 | Activating Receptors |

| NKp80 | BV650 | 5D12 | Activating Receptors |

| NKp46 | BV711 | 9E2/NKp46 | Activating Receptors |

| HLA-DR | BV480 | G46–6 | Activation Marker |

| CD38 | BUV737 | HB7 | Activation Marker |

| α4β7 | Alexa Fluor 647 | Act-1 | Homing Marker |

| Ki67 | BV750 | B56 | Proliferation Marker |

| CD57 | BUV395 | NK-1 | Maturation Marker |

| PD-1 | BUV661 | EH12.1 | Exhaustion Marker |

| EOMES | PE | WD1928 | Transcription Factor |

| T-Bet | PE-Cy5 | 4B10 | Transcription Factor |

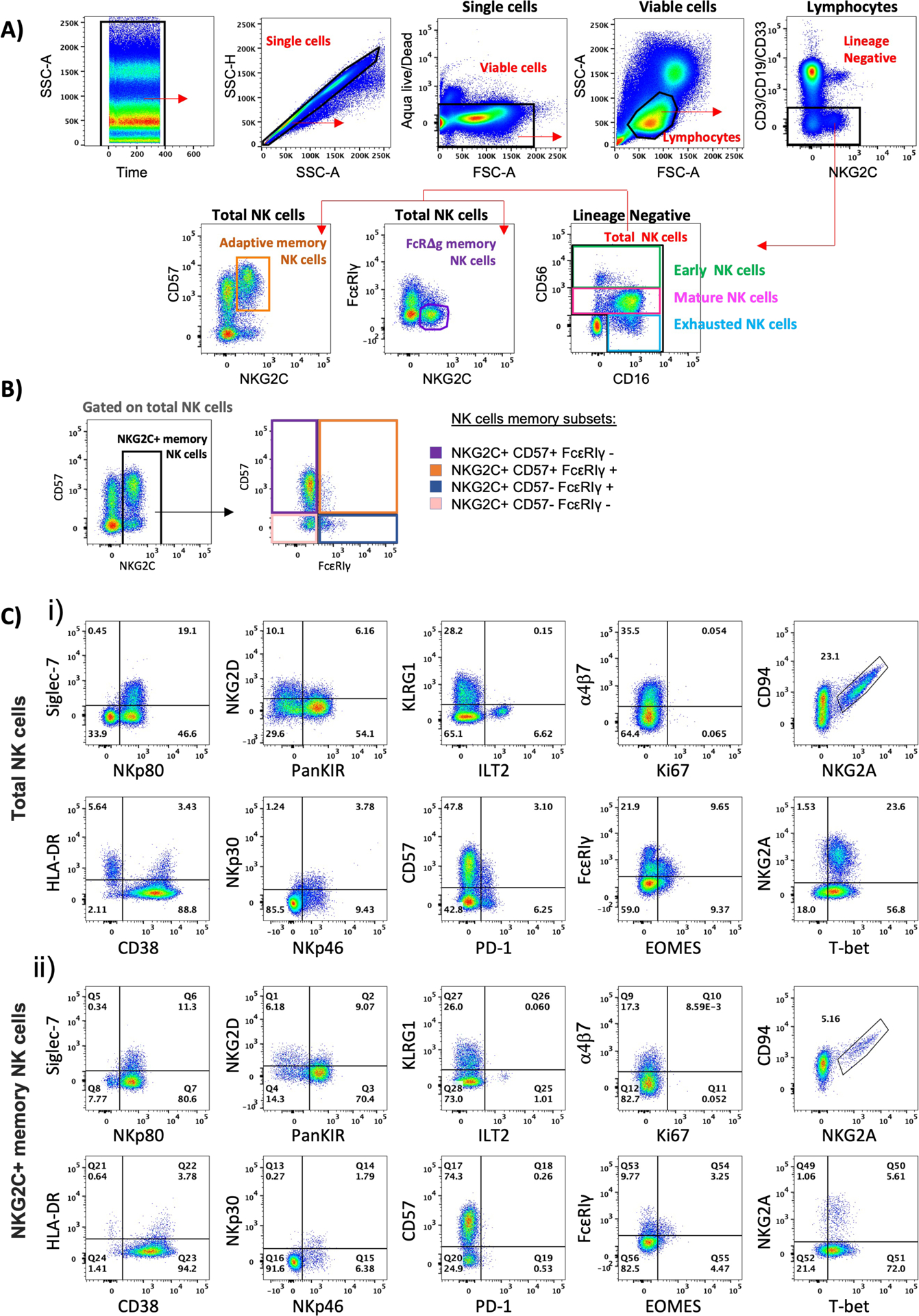

Figure 1:

Example of staining, gating, and phenotypic analysis of memory NK cells.

A) Identification of NK cells from a representative example of a donor without HIV. First, we verified that there were no irregularities in the acquisition over time (SSC-A vs. Time). From single cells (SSC-H vs. SSC-A) we selected live (Aqua−) small lymphocytes (SSC-A vs FSC-A). After exclusion of the lineage-negative cells expressing either CD3/CD19/CD33, total NK cells were identified by the expression of the markers CD56 and CD16. Within the total NK cells, we identified 3 NK cell subsets based on the expression of CD56: early CD56bright, mature CD56dim, and the dysfunctional CD56neg NK cells. We also characterized within the total NK cells the CD57+ NKG2C+ adaptive memory NK cells and the FcεRIγ− NKG2C+ ΔgNK memory cells. B) As the CD57+ NKG2C+ adaptive memory NK cells and the FcεRIγ− NKG2C+ ΔgNK memory cells are overlapping populations, from the total NK cells we define NKG2C+ cells as memory NK cells and subsequently gate the different memory subsets based on the expression of CD57 and FcεRIγ as the following: NKG2C+ CD57+ FcεRIγ-, NKG2C+ CD57+ FcεRIγ+, NKG2C+ CD57- FcεRIγ+, NKG2C+ CD57- FcεRIγ−. C) Representative dot plots of the expression of the parameters included in our panel on total NK cells (i) and NKG2C+ memory NK cells (ii).

Despite being considered innate cells, NK cells can also display features of adaptive immunity. Initial studies reported NKG2C+ NK cells expansion in CMV infection[11], while later studies identified NKG2C+ memory NK cells with adaptive features in peripheral blood in the context of several other viral infections[12–15]. These cells were characterized by increased responses to target cells expressing the non-classical human leukocyte antigen E (HLA-E)[12, 13]. Moreover, mounting evidence demonstrates that NK cells have the potential to develop into long-lived and antigen-specific memory cells[16–19].

Our panel design allows us to analyze some of these memory NK cell subsets. The adaptive memory NK cells are characterized by the acquisition of phenotypic markers CD57 and NKG2C (Figure 1A), and decreased expression of the inhibitory receptor NKG2A[20]. The FcεRIγ-deficient memory NK cells (ΔgNK) are identifiable by their NKG2C expression, lack of expression of the transmembrane signaling adaptor FcRγ, and downregulation of SYK kinases (Figure 1A). These ΔgNK cells have been shown to exhibit potent antiviral functions against Herpes simplex virus, CMV, HIV, and influenza[21–23], and exhibit characteristics of long-term persistence and unique epigenetic profiles[21, 24]. They are also less responsive to cytokine stimulation compared to adaptive CD57+NKG2C+ memory NK cells[24]. On the other hand, they are associated with enhanced ability to mediate ADCC[21–23], a feature that could be highly beneficial in the context of vaccination. More recently, the transmembrane signaling adaptor FcRγ-deficient memory NK cells were associated with lower parasitemia and resistance to malaria[15].

Our panel design included several inhibitory and activating receptors relevant for NK cell functionality and differentiation. We included markers to analyze the expression of inhibitory receptors such as the heterodimer CD94/NKG2A and CD158 killer immunoglobulin-like receptors (KIR). These are involved in NK cell inhibition and maintenance of self-tolerance through interaction with the non-classical human leukocyte antigen E (HLA-E)[25] and the classical major histocompatibility complex molecules, respectively[3, 26, 27]. We have included the CD158e1 (KIR3DL1) and the CD158a/h/g-specific clone HP-MA4 which recognizes several CD158 proteins knowns as KIR2D, specifically KIR2DL1 (CD158a), KIR2DS1 (CD158h), KIR2DS3, and KIR2DS5 (CD158g). However, it has been shown that a minority of individuals could be negative for these CD158 proteins[28, 29].

We have included the adhesion inhibitory receptor sialic acid-binding immunoglobulin-like lectin 7 (Siglec-7), which is mostly expressed by highly functional mature NK cells[30]. The decreased expression of Siglec-7 has been described as an early marker of dysfunctional NK cells in HIV infection, preceding the down-modulation of CD56[31]. Another inhibitory receptor we added to our panel is ILT-2, also known as LILRB1 and CD85j. ILT-2, binds to MHC-I as well as non-classical MHC-I molecules, such as HLA-F and HLA-G. Its ligation inhibits NK cell activation and proliferation[32–34], and it has been shown that blocking ILT-2 restores NK cells function in chronic lymphocytic leukemia.

Our panel allows the analysis of Natural cytotoxicity receptors (NCRs) such as NKp30, NKp46, and the activating co-receptor NKp80. These receptors play a central role in triggering NK cell activation and are expressed in both resting and activated cells. An increased expression of these NCRs has been associated with a reduced HIV-1 reservoir size[35], while a decreased expression leads to impaired NK cell cytotoxicity[36]. The activating co-receptor NKp80 mediates the activation of NK cells and its expression has been shown to be reduced in people living with HIV (PLWH)[37]. We also included receptors from the NKG2 family, which are predominantly expressed on NK cells and a subset of CD8 T cells[38]. NKG2A and NKG2C form a heterodimer with CD94[38], and NKG2D rather associates with itself and forms a homodimer [39]. CD94/NKG2A is highly expressed by early NK cells, where engagement to its non-classical HLA-E ligand leads to NK cell inhibition. In contrast, the activating receptor NKG2C is expressed on mature CD56dim NK cells and enables the identification of two distinct but overlapping memory subsets. The adaptive CMV-memory NK cells are characterized by co-expression of NKG2C and CD57, while ΔgNK memory cells are also NKG2C+ but lack expression of the transmembrane signaling adaptor FcRγ (Figure 1A). Both of these memory subsets exhibit adaptive immune features such as clonal-like expansion and long-term persistence[40]. As these two memory subsets are overlapping populations (see online Fig 5), we analyzed memory NK cells as a combination of ΔgNK and adaptive memory NK cells phenotypes. We then identify NKG2C+ cells as memory NK cells and subsequently based on the expression of CD57 and FcεRIγ, we describe 4 memory subsets: NKG2C+ CD57+ FcεRIγ-, NKG2C+ CD57+ FcεRIγ+, NKG2C+ CD57- FcεRIγ+, and NKG2C+ CD57- FcεRIγ- (Figure 1B).

We were interested in analyzing the activating receptor NKG2D, having been shown that its ligand engagement co-stimulates CD16 signaling and enhances ADCC mediated killing of HIV-infected cells, but its expression is reduced in chronic HIV infection[41]. Due to our interest in the role of memory NK cells in HIV infection, the inhibitory receptor KLRG1 was also included after being recently shown that its expression is increased on antigen-specific memory NK cells[18].

Viral infections such as HIV can result in chronic immune activation, leading to a persistent increased activation of NK cells despite viral suppression post-antiretroviral treatment [42, 43]. To analyze NK cell activation, markers such as HLA-DR and CD38 were added to our panel. We have also included the checkpoint inhibitory receptor PD-1, as its expression has been reported on NK cells in HIV and CMV infections as well as in several tumor models. Checkpoint receptor blockade of PD-1 has also been shown to reverse NK cell impairment[44, 45].

We also included in our panel the transcription factors T-box expressed in T cells (T-bet) and eomesodermin (Eomes) which play a crucial role in NK cell development and effector potential. Both are modulated during maturation of NK cells, with progressive T-bet upregulation and Eomes downregulation toward terminal differentiation[46].

We added the gut-homing marker α4β7 to our analysis, as NK cells undergo large shifts in trafficking to lymph nodes and gut mucosa in response to viral infections. An expansion of CD56+ α4β7+ cytotoxic NK cells was observed in response to SIV infection [47, 48]. Lastly, we have also included the proliferation marker Ki67, increased expression of which has been observed in the dysfunctional CD56neg NK cells leading to their accumulation in PLWH.

Similarity to published OMIPs

Several previously published OMIPs such as OMIP-007, 027, 029, 039, 058, 064, 070, and 080 include NK cell markers, enabling the characterization of NK cells. However, our panel allows us to perform a thorough and deep analysis of NK cells, including of all 3 subsets based on CD56 expression, and the memory subsets which are expanded in chronic infections such HIV.

Our panel covers over 16 immune parameters that are altered in NK cells during viral infections, and would be particularly useful for analysis of rare and small aliquot specimens from unique human cohorts.

Supplementary Material

Table 1.

Summary table for OMIP

| Purpose | Phenotypic profile analysis of total NK cells and memory subsets |

| Species | Human |

| Cell types | PBMCs |

| Cross-References | OMIP-007, 027, 029, 039, 058, 064, 070 & 080 |

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Hannah Kibuuka, Fred Wabwire-Mangen, and Merlin L. Robb for apheresis samples collected under IRB approved protocols (RV228/ WR#1428). The authors would also like to thank all individuals enrolled in these cohorts who donated PBMC used for optimization and testing of the panel.

Funding

This work was supported by a cooperative agreement (W81XWH-18-2-0040) between the Henry M. Jackson Foundation for the Advancement of Military Medicine, Inc., and the U.S. Department of Defense (DoD). Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R21AI172041.

Footnotes

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Army, the National Institutes of Health, the Department of Health and Human Services, the United States Government, or the Henry M. Jackson Foundation for the Advancement of Military Medicine, Inc. The investigators have adhered to the policies for protection of human subjects as prescribed in AR 70–25. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. This article was prepared while Michael A. Eller was employed at Henry M. Jackson Foundation for the Advancement of Military Medicine for the U.S. Military HIV Research Program.

References

- 1.Rosenberg J, Huang J. CD8(+) T Cells and NK Cells: Parallel and Complementary Soldiers of Immunotherapy. Curr Opin Chem Eng 2018; 19:9–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Caligiuri MA. Human natural killer cells. Blood 2008; 112(3):461–469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jost S, Altfeld M. Control of human viral infections by natural killer cells. Annu Rev Immunol 2013; 31:163–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mavilio D, Lombardo G, Kinter A, Fogli M, La Sala A, Ortolano S, et al. Characterization of the defective interaction between a subset of natural killer cells and dendritic cells in HIV-1 infection. J Exp Med 2006; 203(10):2339–2350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moretta A Natural killer cells and dendritic cells: rendezvous in abused tissues. Nat Rev Immunol 2002; 2(12):957–964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vivier E, Raulet DH, Moretta A, Caligiuri MA, Zitvogel L, Lanier LL, et al. Innate or adaptive immunity? The example of natural killer cells. Science 2011; 331(6013):44–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barrow AD, Martin CJ, Colonna M. The Natural Cytotoxicity Receptors in Health and Disease. Front Immunol 2019; 10:909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bjorkstrom NK, Ljunggren HG, Sandberg JK. CD56 negative NK cells: origin, function, and role in chronic viral disease. Trends Immunol 2010; 31(11):401–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Muller-Durovic B, Grahlert J, Devine OP, Akbar AN, Hess C. CD56-negative NK cells with impaired effector function expand in CMV and EBV co-infected healthy donors with age. Aging (Albany NY) 2019; 11(2):724–740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alter G, Teigen N, Davis BT, Addo MM, Suscovich TJ, Waring MT, et al. Sequential deregulation of NK cell subset distribution and function starting in acute HIV-1 infection. Blood 2005; 106(10):3366–3369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guma M, Angulo A, Vilches C, Gomez-Lozano N, Malats N, Lopez-Botet M. Imprint of human cytomegalovirus infection on the NK cell receptor repertoire. Blood 2004; 104(12):3664–3671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beziat V, Dalgard O, Asselah T, Halfon P, Bedossa P, Boudifa A, et al. CMV drives clonal expansion of NKG2C+ NK cells expressing self-specific KIRs in chronic hepatitis patients. Eur J Immunol 2012; 42(2):447–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bjorkstrom NK, Lindgren T, Stoltz M, Fauriat C, Braun M, Evander M, et al. Rapid expansion and long-term persistence of elevated NK cell numbers in humans infected with hantavirus. J Exp Med 2011; 208(1):13–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saghafian-Hedengren S, Sohlberg E, Theorell J, Carvalho-Queiroz C, Nagy N, Persson JO, et al. Epstein-Barr virus coinfection in children boosts cytomegalovirus-induced differentiation of natural killer cells. J Virol 2013; 87(24):13446–13455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hart GT, Tran TM, Theorell J, Schlums H, Arora G, Rajagopalan S, et al. Adaptive NK cells in people exposed to Plasmodium falciparum correlate with protection from malaria. J Exp Med 2019; 216(6):1280–1290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Paust S, Gill HS, Wang BZ, Flynn MP, Moseman EA, Senman B, et al. Critical role for the chemokine receptor CXCR6 in NK cell-mediated antigen-specific memory of haptens and viruses. Nat Immunol 2010; 11(12):1127–1135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stary V, Pandey RV, Strobl J, Kleissl L, Starlinger P, Pereyra D, et al. A discrete subset of epigenetically primed human NK cells mediates antigen-specific immune responses. Sci Immunol 2020; 5(52). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jost SLO, Yoder T, Kroll K, Sugawara S, Scott Smith, et al. Human antigen-specific memory natural killer cell responses develop against HIV-1 and influenza virus and are dependent on MHC-E restriction. bioRxiv preprint 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wijaya RS, Read SA, Truong NR, Han S, Chen D, Shahidipour H, et al. HBV vaccination and HBV infection induces HBV-specific natural killer cell memory. Gut 2021; 70(2):357–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kared H, Martelli S, Tan SW, Simoni Y, Chong ML, Yap SH, et al. Adaptive NKG2C(+)CD57(+) Natural Killer Cell and Tim-3 Expression During Viral Infections. Front Immunol 2018; 9:686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee J, Zhang T, Hwang I, Kim A, Nitschke L, Kim M, et al. Epigenetic modification and antibody-dependent expansion of memory-like NK cells in human cytomegalovirus-infected individuals. Immunity 2015; 42(3):431–442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhou J, Amran FS, Kramski M, Angelovich TA, Elliott J, Hearps AC, et al. An NK Cell Population Lacking FcRgamma Is Expanded in Chronically Infected HIV Patients. J Immunol 2015; 194(10):4688–4697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang T, Scott JM, Hwang I, Kim S. Cutting edge: antibody-dependent memory-like NK cells distinguished by FcRgamma deficiency. J Immunol 2013; 190(4):1402–1406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schlums H, Cichocki F, Tesi B, Theorell J, Beziat V, Holmes TD, et al. Cytomegalovirus infection drives adaptive epigenetic diversification of NK cells with altered signaling and effector function. Immunity 2015; 42(3):443–456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Braud VM, Allan DS, O’Callaghan CA, Soderstrom K, D’Andrea A, Ogg GS, et al. HLA-E binds to natural killer cell receptors CD94/NKG2A, B and C. Nature 1998; 391(6669):795–799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Naiyer MM, Cassidy SA, Magri A, Cowton V, Chen K, Mansour S, et al. KIR2DS2 recognizes conserved peptides derived from viral helicases in the context of HLA-C. Sci Immunol 2017; 2(15). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chapel A, Garcia-Beltran WF, Holzemer A, Ziegler M, Lunemann S, Martrus G, et al. Peptide-specific engagement of the activating NK cell receptor KIR2DS1. Sci Rep 2017; 7(1):2414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vierra-Green C, Roe D, Jayaraman J, Trowsdale J, Traherne J, Kuang R, et al. Estimating KIR Haplotype Frequencies on a Cohort of 10,000 Individuals: A Comprehensive Study on Population Variations, Typing Resolutions, and Reference Haplotypes. PLoS One 2016; 11(10):e0163973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jiang W, Johnson C, Jayaraman J, Simecek N, Noble J, Moffatt MF, et al. Copy number variation leads to considerable diversity for B but not A haplotypes of the human KIR genes encoding NK cell receptors. Genome Res 2012; 22(10):1845–1854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shao JY, Yin WW, Zhang QF, Liu Q, Peng ML, Hu HD, et al. Siglec-7 Defines a Highly Functional Natural Killer Cell Subset and Inhibits Cell-Mediated Activities. Scand J Immunol 2016; 84(3):182–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brunetta E, Fogli M, Varchetta S, Bozzo L, Hudspeth KL, Marcenaro E, et al. The decreased expression of Siglec-7 represents an early marker of dysfunctional natural killer-cell subsets associated with high levels of HIV-1 viremia. Blood 2009; 114(18):3822–3830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bellon T, Kitzig F, Sayos J, Lopez-Botet M. Mutational analysis of immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibition motifs of the Ig-like transcript 2 (CD85j) leukocyte receptor. J Immunol 2002; 168(7):3351–3359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liang S, Zhang W, Horuzsko A. Human ILT2 receptor associates with murine MHC class I molecules in vivo and impairs T cell function. Eur J Immunol 2006; 36(9):2457–2471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lamar DL, Weyand CM, Goronzy JJ. Promoter choice and translational repression determine cell type-specific cell surface density of the inhibitory receptor CD85j expressed on different hematopoietic lineages. Blood 2010; 115(16):3278–3286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marras F, Casabianca A, Bozzano F, Ascierto ML, Orlandi C, Di Biagio A, et al. Control of the HIV-1 DNA Reservoir Is Associated In Vivo and In Vitro with NKp46/NKp30 (CD335 CD337) Inducibility and Interferon Gamma Production by Transcriptionally Unique NK Cells. J Virol 2017; 91(23). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.De Maria A, Fogli M, Costa P, Murdaca G, Puppo F, Mavilio D, et al. The impaired NK cell cytolytic function in viremic HIV-1 infection is associated with a reduced surface expression of natural cytotoxicity receptors (NKp46, NKp30 and NKp44). Eur J Immunol 2003; 33(9):2410–2418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang Z, Zhou Y, Lu J, Chen YF, Hu HY, Xu XQ, et al. Changes in NK Cell Subsets and Receptor Expressions in HIV-1 Infected Chronic Patients and HIV Controllers. Front Immunol 2021; 12:792775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gunturi A, Berg RE, Forman J. The role of CD94/NKG2 in innate and adaptive immunity. Immunol Res 2004; 30(1):29–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zingoni A, Molfetta R, Fionda C, Soriani A, Paolini R, Cippitelli M, et al. NKG2D and Its Ligands: “One for All, All for One”. Front Immunol 2018; 9:476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu W, Scott JM, Langguth E, Chang H, Park PH, Kim S. FcRgamma Gene Editing Reprograms Conventional NK Cells to Display Key Features of Adaptive Human NK Cells. iScience 2020; 23(11):101709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Parsons MS, Richard J, Lee WS, Vanderven H, Grant MD, Finzi A, et al. NKG2D Acts as a Co-Receptor for Natural Killer Cell-Mediated Anti-HIV-1 Antibody-Dependent Cellular Cytotoxicity. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2016; 32(10–11):1089–1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kuri-Cervantes L, de Oca GS, Avila-Rios S, Hernandez-Juan R, Reyes-Teran G. Activation of NK cells is associated with HIV-1 disease progression. J Leukoc Biol 2014; 96(1):7–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lichtfuss GF, Cheng WJ, Farsakoglu Y, Paukovics G, Rajasuriar R, Velayudham P, et al. Virologically suppressed HIV patients show activation of NK cells and persistent innate immune activation. J Immunol 2012; 189(3):1491–1499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Quatrini L, Mariotti FR, Munari E, Tumino N, Vacca P, Moretta L. The Immune Checkpoint PD-1 in Natural Killer Cells: Expression, Function and Targeting in Tumour Immunotherapy. Cancers (Basel) 2020; 12(11). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pesce S, Greppi M, Tabellini G, Rampinelli F, Parolini S, Olive D, et al. Identification of a subset of human natural killer cells expressing high levels of programmed death 1: A phenotypic and functional characterization. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2017; 139(1):335–346 e333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pradier A, Simonetta F, Waldvogel S, Bosshard C, Tiercy JM, Roosnek E. Modulation of T-bet and Eomes during Maturation of Peripheral Blood NK Cells Does Not Depend on Licensing/Educating KIR. Front Immunol 2016; 7:299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Reeves RK, Evans TI, Gillis J, Johnson RP. Simian immunodeficiency virus infection induces expansion of alpha4beta7+ and cytotoxic CD56+ NK cells. J Virol 2010; 84(17):8959–8963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Reeves RK, Gillis J, Wong FE, Yu Y, Connole M, Johnson RP. CD16- natural killer cells: enrichment in mucosal and secondary lymphoid tissues and altered function during chronic SIV infection. Blood 2010; 115(22):4439–4446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.