Abstract

Background

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) is the leading cause of pediatric lower respiratory illness (LRI) and a vaccine for immunization of children is needed. RSV/6120/ΔNS2/1030s is a cDNA-derived live-vaccine candidate attenuated by deletion of the interferon antagonist NS2 gene and the genetically stabilized 1030s missense polymerase mutation in the polymerase, conferring temperature sensitivity.

Methods

A single intranasal dose of RSV/6120/ΔNS2/1030s was evaluated in a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial (vaccine to placebo ratio, 2:1) at 105.7 plaque-forming units (PFU) in 15 RSV-seropositive 12- to 59-month-old children, and at 105 PFU in 30 RSV-seronegative 6- to 24-month-old children.

Results

RSV/6120/ΔNS2/1030s infected 100% of RSV-seronegative vaccinees and was immunogenic (geometric mean RSV plaque-reduction neutralizing antibody titer [RSV-PRNT], 1:91) and genetically stable. Mild rhinorrhea was detected more frequently in vaccinees (18/20 vaccinees vs 4/10 placebo recipients, P = .007), and LRI occurred in 1 vaccinee during a period when only vaccine virus was detected. Following the RSV season, 5 of 16 vaccinees had ≥4-fold rises in RSV-PRNT with significantly higher titers than 4 of 10 placebo recipients with rises (1:1992 vs 1:274, P = .02). Thus, RSV/6120/ΔNS2/1030s primed for substantial anamnestic neutralizing antibody responses following naturally acquired RSV infection.

Conclusions

RSV/6120/ΔNS2/1030s is immunogenic and genetically stable in RSV-seronegative children, but the frequency of rhinorrhea in vaccinees exceeded that in placebo recipients.

Clinical Trials Registration

Keywords: RSV, intranasal vaccine, live-attenuated, pediatric, vaccine

A live-attenuated intranasal RSV vaccine candidate containing a deletion of the NS2 gene and a genetically stabilized mutation in the polymerase gene induced primary and memory serum neutralizing serum antibody responses in 6- to 24-month-old RSV-seronegative children, but may be associated with rhinorrhea.

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) is the leading cause of severe acute lower respiratory illness (LRI) in infants and young children worldwide [1, 2] and a safe and effective pediatric RSV vaccine would have a profound global impact on child health [3]. RSV was estimated to have caused approximately 33 million cases of LRI and over 100 000 deaths per year in children younger than 5 years globally in 2019 [2]. In addition, RSV is a leading cause of hospitalization in this age group [4]. More than 80% of all RSV-LRI and more than half of the RSV deaths in low- and middle-income countries were estimated to occur in infants and children ≥6 months, underscoring the importance of developing RSV vaccines for active immunization of infants and children [5].

Live-attenuated intranasal (LAIN) RSV vaccines are attractive candidates for immunization of young children because they mimic mild natural infection and contain a broad array of viral proteins to induce a full spectrum of local and systemic, innate and adaptive immune responses. Over the past 25 years, LAIN RSV vaccine candidates have been evaluated in >500 RSV-seronegative infants and children [6–17]. Studies have included careful follow-up (surveillance) during the RSV season after enrollment to compare illness and antibody responses among vaccine and placebo recipients following naturally occurring RSV infection. These studies have not shown evidence of the vaccine-associated enhanced RSV disease that was observed in children who received formalin-inactivated RSV [18]. Based on these data, it is generally accepted that LAIN RSV vaccines are not associated with a risk of priming for enhanced RSV. Moreover, a recent post hoc analysis of clinical trials of several LAIN RSV vaccines provided preliminary evidence of efficacy against RSV-associated medically attended acute respiratory illness (MAARI) and medically attended acute lower respiratory illness (MAALRI) [19].

The ideal LAIN RSV vaccine would replicate at a level sufficient to induce protective immunity with minimal vaccine-associated adverse events. The use of reverse genetics [20] and understanding of RSV gene function [21] has led to the development of promising LAIN RSV vaccine candidates, rationally designed through introduction of well-characterized attenuating mutations such as (1) stabilized temperature-sensitivity point mutations that preferentially restrict replication in the lower respiratory tract and (2) deletion of nonessential viral genes such as NS2, a type I/III interferon antagonist that interferes with induction and signaling [22–24] and also promotes epithelial cell shedding, potentially contributing to small airway obstruction [25].

In previous studies, a candidate LAIN RSV vaccine containing the NS2 deletion and a stabilized attenuating codon deletion in the viral polymerase (L) gene, RSV/ΔNS2/Δ1313/I1314L [26], was highly attenuated and immunogenic in RSV-seronegative children [14, 27] and is continuing in clinical development (NCT03916185). RSV/ΔNS2/Δ1313/I1314L contains a deletion of codon 1313 in the L gene. Compensatory mutations to overcome the Δ1313 attenuation phenotype were blocked by the addition of a I1314L mutation. Δ1313/I1314L is attenuating and confers mild temperature sensitivity, resulting in a shutoff temperature of virus replication of 38°C to 39°C (the shutoff temperature is the lowest restrictive temperature at which the reduction compared to 32°C is 100-fold or greater than that observed for wild-type RSV at the 2 temperatures).

Because the highly attenuated RSV/ΔNS2/Δ1313/I1314L might prove to be over-attenuated when evaluated in larger clinical trials, a vaccine candidate containing the NS2 deletion but slightly less restricted in replication may be needed. For this reason, we developed RSV/6120/ΔNS2/1030s, which is identical to RSV/ΔNS2/Δ1313/I1314L except that the Δ1313/I1314L mutations in the L polymerase were replaced by the 1030s missense mutations S1313(TCA) and Y1321K(AAA) [28], in close proximity to the Δ1313 codon deletion. Compared to RSV/ΔNS2/Δ1313/I1314L, RSV/6120/ΔNS2/1030s is slightly less temperature-sensitive (shutoff temperature of 39°C to 40°C) and less restricted in replication in nonhuman primates and in primary human airway epithelial cells [26]. It therefore was expected to be less restricted in replication and more immunogenic than RSV/ΔNS2/Δ1313/I1314L in young children. To test this hypothesis, we conducted a stepwise phase 1 evaluation of RSV/6120/ΔNS2/1030s in RSV-seropositive and -seronegative children.

METHODS

Vaccine

RSV/6120/ΔNS2/1030s was derived from a recombinant version of wild-type RSV strain A2 (rD46 [20]; GenBank accession number KT992094) by the following modification: (1) 5 silent nucleotide changes and a 112-nt phenotypically silent deletion in the SH 3′ noncoding sequence that stabilizes the cDNA during propagation in bacteria [28], and (2) 2 independent attenuating elements consisting of a 522-nt deletion of the NS2 gene and the 1030s mutation in the L polymerase [29]. The virus was generated from cDNA on World Health Organization Vero cells by reverse genetics [20] and clinical trial material (CTM) was prepared at Charles River Laboratories (Malvern, PA). Sequence analysis confirmed that the seed virus and CTM were free of detectable adventitious mutations. The CTM had a mean infectivity titer of 106.0 plaque-forming units (PFU)/mL. CTM was stored at −70°C and diluted to dose on site using Lactated Ringer's solution for Injection (USP). Lactated Ringer's was used as placebo.

Study Population, Study Design, and Clinical Trial Oversight

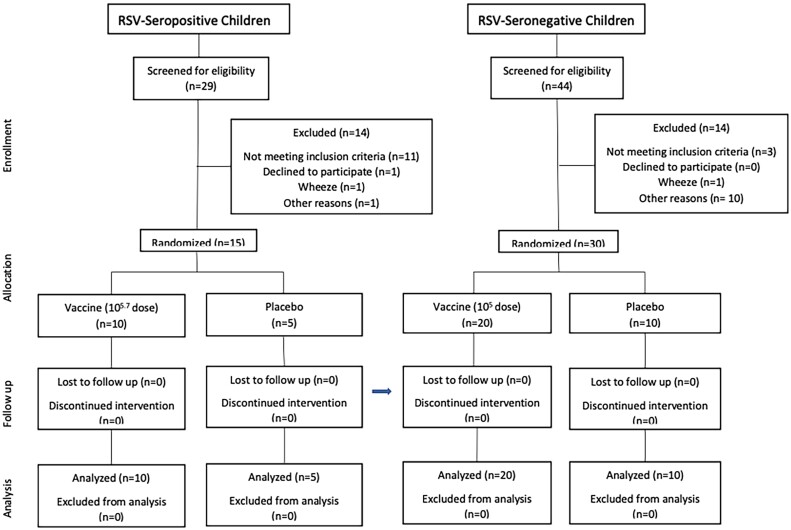

This phase 1 trial was conducted at the Center for Immunization Research (CIR), Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, between October 2017 and September 2020 (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT03387137). A single dose of RSV/6120/ΔNS2/1030s was evaluated sequentially in randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies at a 105.7 PFU dose in RSV-seropositive children aged 12–59 months and at a 105 PFU dose in RSV-seronegative children aged 6–24 months (Figure 1). RSV seropositivity was defined as a serum antibody titer of ≥1:40 in a complement-enhanced 60% plaque reduction neutralization assay [30]. Subjects were randomized 2:1 to receive vaccine or placebo, administered as nose drops (0.5 mL; approximately 0.25 mL per nostril). Randomization, blinding, and unblinding were performed as previously described [11].

Figure 1.

Screening, enrollment, and follow-up of respiratory syncytial virus (RSV)-seropositive children and RSV-seronegative children in the phase 1 clinical trial of the RSV/6120/ΔNS2/1030s vaccine. As described in the “Methods” section, enrollment of RSV-seronegative children occurred following a satisfactory review of safety data from RSV-seropositive children.

Written informed consent was obtained from parents of study participants prior to enrollment. The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and the Standards of Good Clinical Practice (as defined by the International Conference on Harmonization) under National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID)-held Investigational New Drug application (IND17681), reviewed by the US Food and Drug Administration. The clinical protocol, consent forms, and investigators’ brochure were developed by CIR and NIAID investigators and approved by the Western Institutional Review Board (now WCG) and the NIAID Office of Clinical Research Policy and Regulatory Operations. Clinical data were reviewed by CIR and NIAID investigators, and by the Data Safety Monitoring Board of the NIAID Division of Clinical Research.

Clinical Assessment: Acute Phase (Days 0 Through 28)

Children were enrolled between 1 April and 31 October each year, outside of the RSV season. Clinical assessments and nasal wash (NW) were performed as previously described (RSV-seropositive children, study days 0, 3–7, and 10; RSV-seronegative children, study days 0, 3, 5, 7, 10, 12, 14, 17, and 28; ± 1 day at each time point) [11]. Adverse events were collected through day 28 and included fever, upper respiratory tract illness (URI; including rhinorrhea, pharyngitis, hoarseness), cough, LRI (including croup, wheezing, bronchiolitis, pneumonia), and otitis media, as previously described [31]. When illnesses occurred, NWs were obtained and tested for other viruses or mycoplasma by reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR; Respiratory Pathogens 21 kit, Fast Track Diagnostics). Serious adverse events were collected through day 56 for RSV-seronegative children.

Clinical Assessment: Surveillance

RSV-seronegative participants were monitored for MAARI, which included MAALRI, during the first RSV season following inoculation [7]. During this RSV surveillance period (1 November through 31 March), families were contacted weekly to determine whether MAARI had occurred [7, 11]. For each illness, a clinical assessment was performed, and a NW obtained for adventitious agent testing by multiplex RT-PCR. RSV-positive specimens were typed as RSV A or B by RT-PCR assays [11].

Isolation, Quantitation, and Characterization of Virus

Vaccine virus in NW fluid was quantified by immunoplaque assay and quantitative RT-PCR (RT-qPCR) as previously described [14]. To verify the presence and genetic stability of the attenuating elements at time of peak vaccine shedding, viral RNA was obtained from a single passage of NW fluid on Vero cells. The presence of the NS2 gene deletion was verified by sequencing of a 1306-bp RT-PCR amplicon spanning the deletion, and the presence of the 1030s mutation was confirmed by sequencing of 711-bp or 1077-bp RT-PCR amplicons of the L gene region containing this mutation.

Immunologic Assays

Serologic Specimens

Sera were obtained before inoculation, approximately 1 month after inoculation of RSV-seropositive participants, and 2 months after inoculation of RSV-seronegative participants. To measure serum antibody responses following natural exposure to wild-type RSV during the surveillance period, sera were obtained from RSV-seronegative participants in October of the calendar year in which the child was enrolled and in April of the following year; for participants enrolled in September or October, postvaccination sera also served as pre-RSV season sera.

Antibody Assays

Sera were tested for RSV neutralizing antibodies against RSV wild-type strain A2 by complement-enhanced 60% RSV plaque-reduction neutralization assay [30] and for IgG antibodies to the RSV F glycoprotein in the postfusion conformation by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) using a purified F from the RSV A2 strain (human respiratory syncytial virus [RSV] [A2] fusion glycoprotein/RSV-F Protein [His Tag]; Sino Biological). The plaque reduction neutralization titer (PRNT) and RSV F immunoglobulin G (IgG) titer are expressed as reciprocal log2. Antibody responses were defined as ≥4-fold increases in titer in paired specimens.

Data Analysis

Infection with vaccine was defined as detection of vaccine virus by culture or RT-qPCR and/or a ≥ 4-fold rise in RSV PRNT or RSV F IgG. The mean peak titer of vaccine virus shed (log10 PFU/mL) was calculated for infected vaccinees only. Mean serum antibody titers were calculated by group. In a post hoc analysis, mean peak titers among infected RSV-seronegative vaccinees in this study were compared to mean peak titers among RSV-seronegative recipients of the lead candidate live-attenuated RSV vaccine, RSV/ΔNS2/Δ1313/I1314L, in 2 prior studies [14, 27] Student t test was used to compare means between groups. Rates of illness and antibody responses were compared by the 2-tailed Fisher exact test. Pearson correlation coefficient was used to assess peak titers of vaccine virus shed and postvaccination antibody titers.

RESULTS

Study Participants

RSV/6120/ΔNS2/1030s was sequentially evaluated in 15 RSV-seropositive children (10 vaccinees, 5 placebo recipients) and 30 RSV-seronegative infants (20 vaccinees and 10 placebo recipients; Figure 1 and Table 1). None were lost to follow-up or excluded from analysis; however, we were unable to obtain postsurveillance serum specimens from 4 RSV-seronegative vaccinees and 3 RSV-seronegative placebo recipients in April 2020 because of restrictions necessitated by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) pandemic. The mean age of RSV-seropositive participants was 31.1 months (range, 14–57 months), and of RSV-seronegative participants, 11.6 months (range, 6–21 months). Of the 45 participants, 53% were female, 71% white, 4% black, 9% Asian, and 16% described as of mixed racial heritage; 4% were Hispanic and 96% were non-Hispanic.

Table 1.

Clinical Responses and Shedding of Vaccine Virus Among Recipients of RSV/6120/ΔNS21030s or Placebo

| Vaccine Detection in NWa | % With Indicated Symptomsb,c | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subjects | Dose, log10 PFU/mL |

No. of Subjects | % Infectedd | % Shedding Vaccine Viruse |

Plaque Assay log10 PFU/mL (SD)f |

RT-qPCR Mean log10 (SD)g |

Fever | URI | LRIc | Cough | OM | Respiratory or Febrile Illness | Other |

| RSV-seropositive children | |||||||||||||

| Vaccinees | 5.7 | 10 | 20 | 20 | 1.2 (0.5) | 3.1 (0.9) | 20 | 40 | 10 | 10 | 0 | 50 | 30 |

| Placebo recipients | Placebo | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0.5 (0.0) | 1.7 (0.0) | 0 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 20 | 20 |

| RSV-seronegative children | |||||||||||||

| Vaccinees | 5.0 | 20 | 100 | 100 | 3.0 (0.8) | 4.5 (0.8) | 30 | 90 | 10 | 30 | 5 | 90 | 45 |

| Placebo recipients | Placebo | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0.5 (0.0) | 1.7 (0.0) | 20 | 40 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 50 | 30 |

Abbreviations: LRI, lower respiratory illness; NW, nasal wash; OM, otitis media; PFU, plaque-forming units; RT-qPCR, reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction; RSV, respiratory syncytial virus; URI, upper respiratory illness.

aFor each child, the individual peak (highest) titer, irrespective of day, was selected from among all titers measured in the NW. Geometric means were calculated for participants that were infected with vaccine (see footnote d).

bIllness definitions are as described in the text. URI was defined as rhinorrhea, pharyngitis, or hoarseness, and LRI was defined as wheezing, rhonchi, or rales, or having been diagnosed with pneumonia or laryngotracheobronchitis (croup). Other illnesses included rashes, conjunctivitis, nasal congestion, diarrhea, and vomiting.

cLRI was diagnosed in 1 seropositive vaccinee with pneumonia and 2 seronegative vaccinees with croup. At the time of illness, the seropositive vaccinee shed rhinovirus but not vaccine virus, 1 seronegative vaccinee shed HPIV-2 but not vaccine virus, and the other seronegative vaccinee shed vaccine virus with no adventitious agents detected. Additional details are provided in the text.

dInfection with vaccine virus was defined as the detection of vaccine virus by culture and/or RT-qPCR and/or a ≥ 4-fold rise in RSV serum neutralizing antibody titer and/or serum anti-RSV F antibody titer.

ePercent shedding vaccine virus as detected by culture and/or rRT-qPCR. The limit of detection of vaccine virus by culture was 0.5 log10 PFU/mL, and by qPCR 1.7 log10 copies/mL.

fTiters measured in NW by RSV immunoplaque assay and expressed as log10 PFU/mL. The lower limit of detection was 0.5 log10 PFU/mL.

gTiters measured in NW by RT-qPCR and expressed as log10 copies/mL. The lower limit of detection was 1.7 log10 copies/mL.

Adverse Events and Vaccine Infectivity

During the 28 days following inoculation, respiratory or febrile illnesses were observed in 5 of 10 RSV-seropositive vaccinees, and community-acquired respiratory viruses were detected concurrent with each illness. One RSV-seropositive vaccinee with fever, cough, rhinorrhea, and pneumonia shed rhinovirus but not vaccine virus; 1 vaccinee with fever shed vaccine virus at low titer (1.5 log10 PFU/mL) for a single day and was coinfected with bocavirus; and the remaining 3 had rhinorrhea and concurrently shed human metapneumovirus, adenovirus, and rhinovirus but not vaccine virus. One other seropositive vaccinee shed vaccine virus for a single day (0.8 log10 PFU/mL) that was not coincident with illness. One of the 5 RSV-seropositive placebo recipients had respiratory illness (rhinorrhea) and concurrently shed rhinovirus (Table 1).

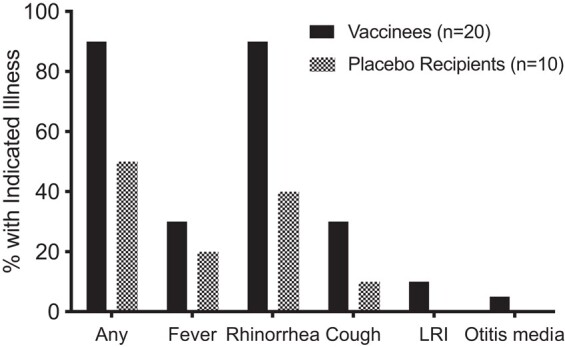

In RSV-seronegative participants, rhinorrhea, cough, and febrile illnesses occurred frequently in vaccine and placebo recipients, as is typical for this age group. Overall, respiratory or febrile illness was observed significantly more often in vaccinees than in placebo recipients (18/20 [90%] vaccinees vs 5/10 [50%] placebo recipients, P = .026; Table 1 and Figure 2); rhinorrhea was particularly frequent (18/20 [90%] vaccinees vs 4/10 [40%] placebo recipients, P = .007; Table 1 and Figure 2). Fever and cough also occurred more frequently in vaccinees than placebo recipients, though not at significant rates (Figure 2). Of particular note, 2 episodes of LRI (croup; severity grade 2) occurred in RSV-seronegative vaccinees (Table 1 and Figure 2). One episode occurred on days 22–24 postimmunization and was associated with parainfluenza virus type 2 and not vaccine virus, and the second episode occurred on day 8, during a period of rhinorrhea from days 2 to 10, with rhinovirus detected on day 3 and vaccine virus detected on days 3, 5, 7, 9, 10, and 12, with a peak titer of 104.1 PFU on day 9. In all, non-RSV respiratory viruses were detected in 13 of 20 and 5 of 10 RSV-seronegative vaccine and placebo recipients, respectively, and included rhinovirus, enterovirus, adenovirus, bocavirus, and parainfluenza virus types 2 and 4.

Figure 2.

Proportions of RSV-seronegative vaccinees and placebo recipients with indicated illnesses during the first 28 days postvaccination. Vaccinees are shown in black; placebo recipients are shown in gray. Abbreviations: LRI, lower respiratory illness; RSV, respiratory syncytial virus.

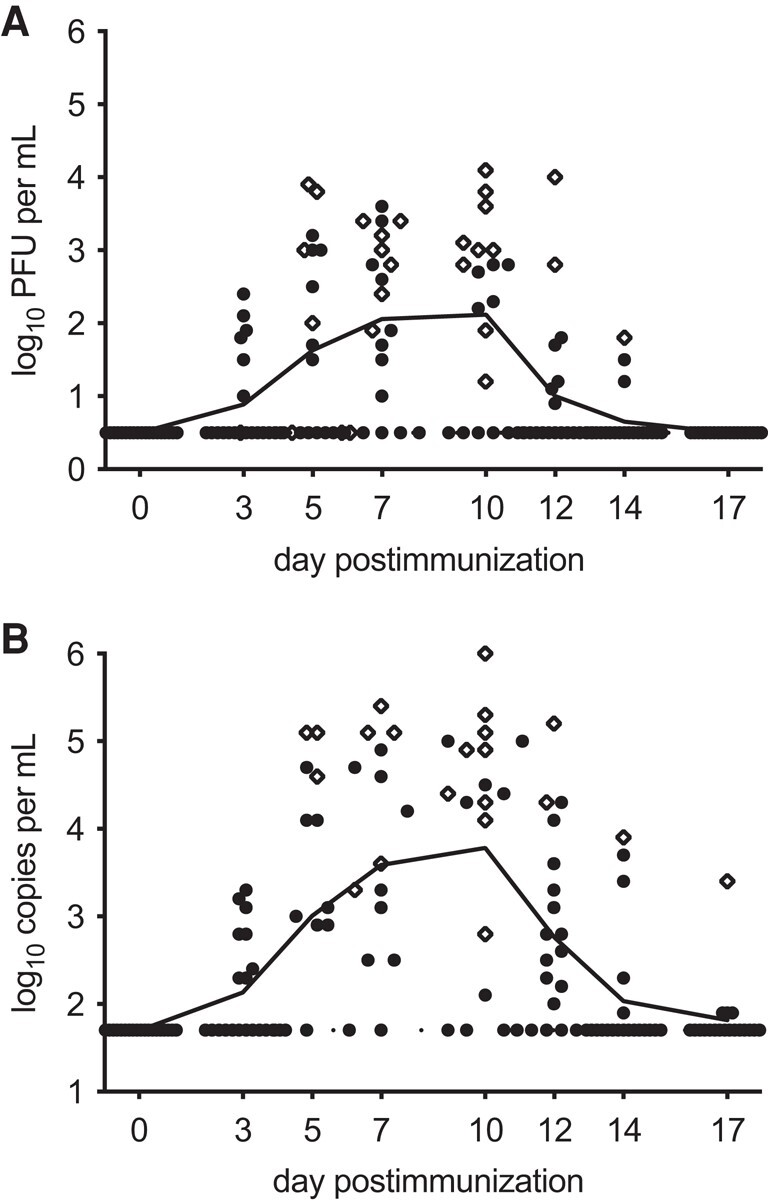

Replication and Genetic Stability of RSV/6120/ΔNS2/1030 in RSV-Seronegative Children

All seronegative vaccinees were infected with vaccine virus. In most vaccinees, vaccine virus shedding occurred over several days (median, 3 days; Figure 3), with peak vaccine shedding occurring between days 5 and 17 (Figure 3). The geometric mean peak titer (GMT) in NW by culture was 103.0 PFU/mL and the geometric mean peak copy number by RT-qPCR was 104.5 copies/mL (Table 1). When vaccine virus titers in recipients of RSV/6120/ΔNS2/1030s were compared to titers in recipients of 106.0 PFU of RSV/ΔNS2/Δ1313/I1314L (a 10-fold higher dose) in 2 previous clinical trials [14, 27], we found that titers in recipients of the current vaccine candidate were significantly higher compared to the first study [14] for the GMT by culture (101.8 PFU/mL; P = .004) and for RNA copies by RT-qPCR (103.5 copies/mL; P = .0079; 1-way ANOVA with Tukey multiple comparison), but were not higher than the second study [27] (GMTs by culture, 102.9 PFU/mL; by RT-qPCR, 104.6 copies/mL). RT-PCR and partial sequence analysis of NW isolates obtained at the peak of vaccine shedding from RSV-seronegative vaccinees confirmed the presence of the NS2 deletion and the presence and genetic stability of the 1030s mutation.

Figure 3.

Individual daily titers of vaccine virus shed by RSV-seronegative recipients of 105.0 PFU of vaccine, with symbols representing titers by culture (A) and by RT-qPCR (B). Peak titers from individual vaccinees are shown as diamonds, and means are indicated by a continuous line. Culture-negative samples were assigned a titer of 0.5 log10 PFU/mL, and RT-qPCR-negative samples were assigned a titer of 1.7 log10 copies/mL, indicated by the dotted line in A and B, Abbreviations: PFU, plaque-forming unit; RSV, respiratory syncytial virus; RT-qPCR, reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction.

Antibody Responses to RSV/ΔNS2/1030s

None of the RSV-seropositive vaccinees had a ≥4-fold rise in RSV F serum IgG titer or RSV PRNT (Table 2). Of 20 RSV-seronegative vaccinees, 18 developed RSV-specific serum antibody responses by day 56 after immunization: of these, 18 of 18 had ≥4-fold rises in RSV PRNT and 17 of 18 developed F-ELISA IgG responses (Table 2). The mean reciprocal postvaccination PRNT was 6.5 log2, or 1:91 (Table 2). Two subjects who shed vaccine virus had no detectable antibody response. There was no correlation between peak vaccine virus shedding as measured by culture or RT-qPCR and neutralizing or RSV F IgG antibody responses (data not shown).

Table 2.

Antibody Responses to RSV Vaccination and Wild-Type RSV Infection Among Recipients of RSV 6120/ΔNS2/1030s or Placebo

| Serum RSV Neutralizing Ab, Mean (SD)a | Serum IgG ELISA RSV F Ab, Mean (SD)a | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subjects | Dose, log10 PFU/mL | No. of Subjects | Preinoculation | Postinoculation | ≥4 Fold Rise, % | Presurveillanceb | Postsurveillanceb | ≥4 Fold Rise, % | Preinoculation | Postinoculation | ≥4 Fold Rise, % |

| RSV-seropositive children | |||||||||||

| Vaccinees | 5.7 | 10 | 7.4 (0.7) | 7.1 (1.0) | 0 | ND | ND | ND | 12.2 (1.5) | 12.1 (1.5) | 0 |

| Placebo recipients | Placebo | 5 | 7.4 (0.6) | 7.2 (0.7) | 0 | ND | ND | ND | 13.1 (0.8) | 12.9 (0.5) | 0 |

| RSV-seronegative children | |||||||||||

| Vaccinees | 5.0 | 20 | 2.8 (0.9) | 6.5 (1.1) | 90 | 6.5 (1.2) | 7.8 (2.7) | 31 | 6.4 (2.0) | 10.9 (1.7) | 85 |

| Placebo recipients | Placebo | 10 | 2.9 (0.9) | 2.6 (0.6) | 0 | 2.6 (0.6) | 5.6 (3.2) | 57 | 6.7 (1.6) | 6.0 (2.0) | 0 |

Abbreviations: Ab, antibody; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; PRNT60, 60% plaque reduction neutralizing titer; RSV, respiratory syncytial virus.

aAb data are expressed as reciprocal mean log2 titers. Postinoculation antibody titers were measured at day 28 in RSV-seropositive children and at day 56 in RSV-seronegative children. Serum RSV PRNT60 were determined by complement-enhanced 60% plaque and reduction neutralization assay; serum IgG titers to RSV F were determined by ELISA. Results are expressed as mean reciprocal log2 (SD). Titers below the limit of detection were assigned values of 2.3 log2 (PRNT60) and 4.6 log2 (ELISA).

bFor RSV-seronegative children, sera were also collected and assayed before (presurveillance) and after (postsurveillance) the surveillance period. Postsurveillance sera were not collected from 4 vaccinees and 3 placebo recipients during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic; therefore, means are presented for 16 vaccinees and 7 placebo recipients.

Surveillance During the RSV Season

All 30 RSV-seronegative children participated in RSV surveillance during the RSV (winter) season following inoculation (Supplementary Table 1). All-cause MAARI was frequent, occurring in 9 of 20 vaccinees and 7 of 10 placebo recipients; all-cause MAALRI (a subset of MAARI) occurred in 3 of 20 vaccinees and 2 of 10 placebo recipients.

RSV-associated MAARI occurred in 4 vaccinees (2 RSV A and 2 RSV B) and in 2 placebo recipients (1 RSV A and 1 RSV B); RSV-associated MAALRI (a subset of RSV-MAARI) occurred in 2 vaccinees and no placebo recipients. The instances of RSV-MAALRI in vaccinees involved wheezing and/or a diagnosis of bronchiolitis and were associated with RSV A infections: in 1 instance, RSV A and coronavirus 229 were simultaneously detected; interestingly, this participant was 1 of 2 vaccine recipients that had no RSV serum antibody response detectable by ELISA or PRNT by day 56 after immunization. In the other vaccinee, RSV A alone was detected. Other non-RSV pathogens detected in children with MAALRI included rhinovirus and bocavirus (1 vaccinee) and bocavirus and human metapneumovirus (1 placebo recipient). Serum specimens were obtained at the end of surveillance from 16 of 20 vaccinees and 7 of 10 placebo recipients (see “Methods”). Four-fold or greater increases in RSV PRNT were detected in 5 of 16 vaccinees and 4 of 7 placebo recipients (Table 2). Of the 6 children who experienced RSV-MAARI, 5 had a ≥ 4-fold increase in PRNT; the sixth (a vaccinee) had a 3.7-fold increase.

Evidence of infection with wild-type RSV (based on ≥4-fold rises in RSV PRNT over the RSV surveillance season and/or virus detection) was observed in 6 vaccinees and 5 placebo recipients: of these subjects, RSV PRNT rises accompanied by RSV-MAARI or MAALRI occurred in 3 of 6 vaccinees and 2 of 5 placebo recipients; RSV-MAALRI without RSV PRNT rise over the surveillance season occurred in 1 of 6 vaccinees; antibody rises without RSV-MAARI/MAALRI occurred in 2 of 6 vaccinees and 2 of 5 placebo recipients; and the remaining placebo recipient had RSV-MAARI with RSV detected, but a postseason serology specimen was not obtained. Among the children with ≥4-fold rises in RSV PRNT over the RSV surveillance season, the mean reciprocal PRNT was significantly higher in the 5 vaccinees (11 log2; 1:1992) than in the 4 placebo recipients (8.1 log2; 1:274), P = .02, indicating that prior vaccination primed for strong anamnestic responses.

DISCUSSION

RSV/6120/ΔNS2/1030s was designed to be a genetically stable LAIN vaccine that would be somewhat less restricted in replication than the lead candidate RSV/ΔNS2/Δ1313/I1314L, so as to provide an alternative should RSV/ΔNS2/Δ1313/I1314L prove to be overattenuated in ongoing expanded clinical studies. Preclinical studies showed that RSV/6120/ΔNS2/1030s was less temperature sensitive and less restricted in experimental animals than RSV/ΔNS2/Δ1313/I1314L [26]. In a previous phase 1 study, 105 PFU of RSV/ΔNS2/Δ1313/I1314L infected 80% of RSV-seronegative children with a peak GMT of 0.6 log10 PFU/mL detected in nasal samples [14]. ln contrast, the same dose of RSV/6120/ΔNS2/1030s in the present study infected 100% of RSV-seronegative children with a peak GMT of 3.0 log10 PFU/mL. The substantial magnitude of this increase in replication was unexpected, given the minimal genomic differences between the 2 vaccine candidates, involving codons 1313 and 1314 in RSV/ΔNS2/Δ1313/I1314L and 1313 and 1321 in RSV/6120/ΔNS2/1030s, all within a 9-amino acid segment in the viral polymerase (L) gene. Additional studies in larger numbers of children would be needed to confirm this observation; however, this initial study suggests that RSV/6120/ΔNS2/1030s is substantially less restricted in replication than RSV/ΔNS2/Δ1313/I1314L. Like the Δ1313/I1314L mutation in RSV/ΔNS2/Δ1313/I1314L, the 1030s mutation in RSV/6120/ΔNS2/1030s had been stabilized through reverse genetics [29], and its stability was confirmed in combination with other attenuating mutations in 2 previous clinical studies [12, 15, 29]. In the current study, partial sequencing of vaccine virus isolates further confirmed the stability of the ΔNS2 and 1030s mutations.

RSV-seronegative children that received RSV/6120/ΔNS2/1030s (105 PFU) had higher rates of rhinorrhea than placebo recipients, all of grade 1 severity. In contrast, in the previous study of RSV/ΔNS2/Δ1313/I1314L (106) in RSV-seronegative children, vaccinees did not have an excess of respiratory or febrile illness [14]. While an increase in mild rhinorrhea likely would be acceptable for a live-attenuated RSV vaccine that is administered to infants aged 4 months and above, an increase in cough or LRI coincident with vaccine virus shedding would be concerning. There was a single instance of LRI associated with vaccine virus shedding in a seronegative recipient of RSV/6120/ΔNS2/1030s. While this potential safety signal requires further evaluation, this study was too small to reliably evaluate the occurrence of rarer safety events such as cough and LRIs.

RSV/6120/ΔNS2/1030s (105 PFU) compared well to RSV/ΔNS2/Δ1313/I1314L (106 PFU) with respect to induction of RSV neutralizing antibody: postvaccination mean PRNT60 titers were 6.5 log2 versus 6.0 log2 and 5.0 log2 following administration of RSV/ΔNS2/Δ1313/I1314L, in previous studies [14, 27]. A recent post hoc analysis of several studies of live-attenuated RSV vaccines suggested that the serum antibody response following vaccination may be useful as a predictor of vaccine efficacy [19]. As has been previously observed with several live-attenuated RSV candidate vaccines [11–14], RSV/6120/ΔNS2/1030s primed for a substantial anamnestic antibody response in children who were subsequently infected with wild-type RSV through community exposure.

Previous studies of RSV/ΔNS2/Δ1313/I1314L and the current study of RSV/6120/ΔNS2/1030s were performed using identical study schedules, clinical evaluation procedures and case definitions, and laboratory procedures (with assays performed in the same laboratories). Nevertheless, it is difficult to directly compare these investigational vaccines based on post hoc analyses because of several potentially confounding factors. As examples, it is possible that yearly differences in the overall burden of pediatric respiratory viruses in the community will alter the baseline innate immune status in the respiratory tract, affecting vaccine “take,” and individual studies also differ in baseline RSV serum antibody titers in pediatric participants, possibly reflecting the presence of residual maternal antibodies or RSV exposures under the protection of maternal antibodies. Even when baseline RSV serum antibody titers in eligible RSV-seronegative participants are below the protocol-defined PRNT cutoff of 1:40, there is the potential that immune priming may occur in the absence of a detectable antibody response.

To reliably compare these 2 closely related vaccines, side-by-side evaluations in larger study cohorts under the same clinical protocol are needed. To this end, RSV/ΔNS2/Δ1313/I1314L and RSV/6120/ΔNS2/1030s are currently being compared in a larger multisite phase 1/2 study (NCT03916185) that is powered to directly compare antibody responses to the 2 vaccines, and to compare the safety of each vaccine to placebo. However, this larger study still is underpowered to evaluate rare safety events, and the study design precludes the frequent nasal sampling that is included here. This study provides detailed information regarding magnitude, kinetics, and duration of RSV/6120/ΔNS2/1030s vaccine shedding, which will be essential for further development of this vaccine candidate.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at The Journal of Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Ruth A Karron, Department of International Health, Center for Immunization Research, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, Maryland, USA.

Cindy Luongo, RNA Viruses Section, Laboratory of Infectious Diseases, National Institute of Allergy, Immunology, and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland, USA.

Suzanne Woods, Department of International Health, Center for Immunization Research, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, Maryland, USA.

Jennifer Oliva, Department of International Health, Center for Immunization Research, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, Maryland, USA.

Peter L Collins, RNA Viruses Section, Laboratory of Infectious Diseases, National Institute of Allergy, Immunology, and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland, USA.

Ursula J Buchholz, RNA Viruses Section, Laboratory of Infectious Diseases, National Institute of Allergy, Immunology, and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland, USA.

the RSVPed Team:

Christine Council-Dibitetto, Milena Gatto, Tina Ghasri, Amanda Gormley, Kristi Herbert, Maria Jordan, Karen Loehr, Jason Morsell, Jocelyn San Mateo, Elizabeth Schappell, Khadija Smith, Paula Soro, Kimberli Wanionek, and Cathleen Weadon

Notes

Acknowledgments . We thank the RSVPed Team: Christine Council-Dibitetto, Milena Gatto, Tina Ghasri, Amanda Gormley, Kristi Herbert, Maria Jordan, Karen Loehr, Jason Morsell, Jocelyn San Mateo, Elizabeth Schappell, Khadija Smith, Paula Soro, Kimberli Wanionek, Cathleen Weadon, all at the Center for Immunization Research, Department of International Health, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, MD. We also thank the Office of Clinical Research Policy and Regulatory Operations, DCR, NIAID, NIH, for regulatory sponsorship. We are grateful to The Pediatric Group, Primary Pediatrics, Dundalk Pediatric Associates, Howard County Pediatrics, Pediatric Place, Columbia Medical Practice, Maryland Pediatric Group, and Johns Hopkins Community Physicians for allowing us to approach families, and to the families for participation in this study.

Financial support . This work was supported by National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health (NIAID, NIH; grant number HHS 272200900010C to R. A. K., S. W., J. O., and the RSVPed Team); the Intramural Program of the NIAID (to C. L., P. L. C., and U. J. B.); and a Cooperative Research and Development Agreement between NIAID, NIH, and Sanofi.

References

- 1. Hall CB, Weinberg GA, Iwane MK, et al. . The burden of respiratory syncytial virus infection in young children. N Engl J Med 2009; 360:588–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Li Y, Wang X, Blau DM, et al. . Global, regional, and national disease burden estimates of acute lower respiratory infections due to respiratory syncytial virus in children younger than 5 years in 2019: a systematic analysis. Lancet 2022; 399:2047–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Karron RA. Preventing respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) disease in children. Science 2021; 372:686–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wang X, Li Y, Mei X, Bushe E, Campbell H, Nair H. Global hospital admissions and in-hospital mortality associated with all-cause and virus-specific acute lower respiratory infections in children and adolescents aged 5–19 years between 1995 and 2019: a systematic review and modelling study. BMJ Glob Health 2021; 6:e006014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Karron RA, Black RE. Determining the burden of respiratory syncytial virus disease: the known and the unknown. Lancet 2017; 390:917–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wright PF, Karron RA, Belshe RB, et al. . Evaluation of a live, cold-passaged, temperature-sensitive, respiratory syncytial virus vaccine candidate in infancy. J Infect Dis 2000; 182:1331–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Karron RA, Wright PF, Belshe RB, et al. . Identification of a recombinant live attenuated respiratory syncytial virus vaccine candidate that is highly attenuated in infants. J Infect Dis 2005; 191:1093–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wright PF, Karron RA, Madhi SA, et al. . The interferon antagonist NS2 protein of respiratory syncytial virus is an important virulence determinant for humans. J Infect Dis 2006; 193:573–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wright PF, Karron RA, Belshe RB, et al. . The absence of enhanced disease with wild type respiratory syncytial virus infection occurring after receipt of live, attenuated, respiratory syncytial virus vaccines. Vaccine 2007; 25:7372–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Malkin E, Yogev R, Abughali N, et al. . Safety and immunogenicity of a live attenuated RSV vaccine in healthy RSV-seronegative children 5 to 24 months of age. PLoS One 2013; 8:e77104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Karron RA, Luongo C, Thumar B, et al. . A gene deletion that up-regulates viral gene expression yields an attenuated RSV vaccine with improved antibody responses in children. Sci Transl Med 2015; 7:312ra175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Buchholz UJ, Cunningham CK, Muresan P, et al. . Live respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) vaccine candidate containing stabilized temperature-sensitivity mutations is highly attenuated in RSV-seronegative infants and children. J Infect Dis 2018; 217:1338–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. McFarland EJ, Karron RA, Muresan P, et al. . Live-attenuated respiratory syncytial virus vaccine candidate with deletion of RNA synthesis regulatory protein M2-2 is highly immunogenic in children. J Infect Dis 2018; 217:1347–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Karron RA, Luongo C, Mateo JS, Wanionek K, Collins PL, Buchholz UJ. Safety and immunogenicity of the respiratory syncytial virus vaccine RSV/DeltaNS2/Delta1313/I1314L in RSV-seronegative children. J Infect Dis 2020; 222:82–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. McFarland EJ, Karron RA, Muresan P, et al. . Live respiratory syncytial virus attenuated by M2-2 deletion and stabilized temperature sensitivity mutation 1030s is a promising vaccine candidate in children. J Infect Dis 2020; 221:534–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. McFarland EJ, Karron RA, Muresan P, et al. . Live-attenuated respiratory syncytial virus vaccine with M2-2 deletion and with small hydrophobic noncoding region is highly immunogenic in children. J Infect Dis 2020; 221:2050–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cunningham CK, Karron R, Muresan P, et al. . Live-attenuated respiratory syncytial virus vaccine with deletion of RNA synthesis regulatory protein M2-2 and cold passage mutations is overattenuated. Open Forum Infect Dis 2019; 6:ofz212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kim HW, Canchola JG, Brandt CD, et al. . Respiratory syncytial virus disease in infants despite prior administration of antigenic inactivated vaccine. Am J Epidemiol 1969; 89:422–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Karron RA, Atwell JE, McFarland EJ, et al. . Live-attenuated vaccines prevent respiratory syncytial virus-associated illness in young children. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2021; 203:594–603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Collins PL, Hill MG, Camargo E, Grosfeld H, Chanock RM, Murphy BR. Production of infectious human respiratory syncytial virus from cloned cDNA confirms an essential role for the transcription elongation factor from the 5′ proximal open reading frame of the M2 mRNA in gene expression and provides a capability for vaccine development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1995; 92:11563–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Collins PL, Melero JA. Progress in understanding and controlling respiratory syncytial virus: still crazy after all these years. Virus Res 2011; 162:80–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ramaswamy M, Shi L, Varga SM, Barik S, Behlke MA, Look DC. Respiratory syncytial virus nonstructural protein 2 specifically inhibits type I interferon signal transduction. Virology 2006; 344:328–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lo MS, Brazas RM, Holtzman MJ. Respiratory syncytial virus nonstructural proteins NS1 and NS2 mediate inhibition of stat2 expression and alpha/beta interferon responsiveness. J Virol 2005; 79:9315–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Spann KM, Tran K-C, Chi B, Rabin RL, Collins PL. Suppression of the induction of alpha, beta, and lambda interferons by the NS1 and NS2 proteins of human respiratory syncytial virus in human epithelial cells and macrophages. J Virol 2004; 78:4363–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Liesman RM, Buchholz UJ, Luongo CL, et al. . RSV-encoded NS2 promotes epithelial cell shedding and distal airway obstruction. J Clin Invest 2014; 124:2219–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Luongo C, Winter CC, Collins PL, Buchholz UJ. Respiratory syncytial virus modified by deletions of the NS2 gene and amino acid S1313 of the L polymerase protein is a temperature-sensitive, live-attenuated vaccine candidate that is phenotypically stable at physiological temperature. J Virol 2013; 87:1985–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cunningham CK, Karron RA, Muresan P, et al. . Evaluation of recombinant live-attenuated respiratory syncytial virus vaccines RSV/DeltaNS2/Delta1313/I1314L and RSV/276 in RSV seronegative children. J Infect Dis 2022; 226:2069–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bukreyev A, Belyakov IM, Berzofsky JA, Murphy BR, Collins PL. Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor expressed by recombinant respiratory syncytial virus attenuates viral replication and increases the level of pulmonary antigen-presenting cells. J Virol 2001; 75:12128–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Luongo C, Winter CC, Collins PL, Buchholz UJ. Increased genetic and phenotypic stability of a promising live-attenuated respiratory syncytial virus vaccine candidate by reverse genetics. J Virol 2012; 86:10792–804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Coates HV, Alling DW, Chanock RM. An antigenic analysis of respiratory syncytial virus isolates by a plaque reduction neutralization test. Am J Epidemiol 1966; 83:299–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Karron RA, Wright PF, Crowe JE Jr. Evaluation of two live, cold-passaged, temperature-sensitive respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) vaccines in chimpanzees, adults, infants and children. J Infect Dis 1997; 176:1428–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.