Abstract

Lipid A is the active center of bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS), which exhibits diverse biological activities via the production of various mediators. We investigated the production of nitric oxide (NO), one of the mediators, by a murine macrophage cell line, RAW264.7, upon stimulation with a series of monosaccharide lipid A analogues to elucidate the relationship of structure and activity in NO production. The production of other representative mediators, such as tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) and interleukin-6 (IL-6), was also investigated to compare the structural requirements for the production of these cytokines with those for the production of NO. Structure-activity relationships in NO production correlated well with those in the production of TNF-α and IL-6. Among the lipid A analogues possessing different numbers of acyl groups on a 4-O-phosphono-d-glucosamine backbone, compounds like GLA-60 that possess three tetradecanoyl (C14) groups exhibited stronger activities in the production of the mediators than compounds possessing four or two C14 groups. Time course study of the production of these mediators showed that production of NO started and peaked later than those of TNF-α and IL-6. Neither neutralization of TNF-α activity by antibody nor suppression of TNF-α production by pentoxifylline showed a significant suppressive effect on production of NO and IL-6 upon stimulation with LPS or lipid A analogues. Neutralization of IL-6 activity by antibody showed no significant suppressive effect on production of NO and TNF-α. A monosaccharide lipid A analogue (GLA-58) which exhibited no detectable agonistic activity showed a suppressive effect on the production of all three mediators upon stimulation with LPS or lipid A analogues. These results indicate that signals for NO production by LPS agonists in murine macrophages are transduced in good correlation with those for production of TNF-α and IL-6, although they are not transduced via production of those cytokines.

Bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS) in the outer membranes of gram-negative bacteria is the principal component of endotoxin, which activates the host immune system and has a variety of pathophysiological effects (18). Many of these activities are mediated by various substances (mediators) that are produced by macrophages and other cells after stimulation with LPS. Cytokines and arachidonic acid metabolites are involved in such mediators (13). In addition to these mediators, nitric oxide (NO) has recently received considerable attention as a new type of mediator (17).

The active center of LPS was revealed to be its lipid part, called lipid A, by the use of chemically synthesized lipid A, which expressed full endotoxic activities (4, 7, 11). In addition to the compound with the complete lipid A structure, which was named 506, a wide variety of structurally modified compounds were synthesized and studied intensively for structure-activity relationships. We have shown that the monosaccharide type of lipid A analogue, whose molecules are about half the size of those of the complete lipid A with a disaccharide structure, can exhibit various LPS activities but not pyrogenicity (8, 16). Using a series of monosaccharide lipid A analogues, we showed that the acylation patterns of the analogues as well as the phosphorylation patterns play an important role in biological activities (12), as is the case for disaccharide analogues (3). The relationships of the structures and activities of monosaccharide lipid A analogues in the production of cytokines from murine macrophages have been studied in vitro and in vivo, (8), but the ability of the analogues to induce NO production was not studied in detail. Detailed studies of structure-activity relationships in NO production with a series of lipid A analogues are necessary to characterize the structural requirements for NO production, especially with regard to whether they are separable from those for production of the other LPS-induced mediators. The results obtained from such studies will also provide information for a better understanding of the characteristic features of LPS-derived NO production.

In the present study, we aimed to clarify the structure-activity relationship of monosaccharide lipid A analogues with different acylation patterns in the production of NO from murine macrophages, and we compared it with those in the production of cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) and interleukin-6 (IL-6). The activities of the analogues in NO production varied from strongly positive to negative, depending on their structure, and the intensity of activity correlated well with the production of cytokine, suggesting the existence of closely related regulatory mechanisms between signaling pathways for the production of NO and the production of TNF-α and IL-6.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents.

The LPS, which was isolated and purified from Salmonella abortus equi (5), was a kind gift from C. Galanos, Max-Planck-Institut für Immunbiologie, Freiburg, Germany. Synthetic lipid A, 506, was obtained from Daiichi Pure Chemical Co. Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan). Monosaccharide lipid A analogues were synthesized chemically as described elsewhere (9, 10). The structures of these compounds are shown in Fig. 1, 2, and 3. These compounds were solubilized in triethylamine salt form, stabilized with bovine serum albumin in pyrogen-free distilled water as described previously (14), and stored at 4°C until use. Anti-mouse TNF-α antibody was kindly donated by Suntory Co. Ltd., Osaka, Japan. Anti-mouse IL-6 was purchased from Genzyme, Inc. (Cambridge, Mass.), and pentoxifylline (PTX) was purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, Mo.).

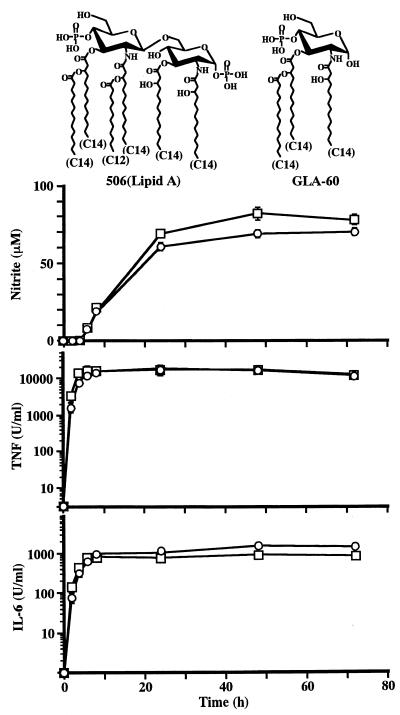

FIG. 1.

Production of NO, TNF-α, and IL-6 by RAW264.7 cells after stimulation with lipid A (506) and a monosaccharide lipid A analogue (GLA-60). RAW264.7 cells were cultured in the presence of 506 (□) at 100 ng/ml or GLA-60 (○) at 10 μg/ml. Culture supernatants were obtained at the indicated times for measurement of NO, TNF-α, and IL-6. The data are the means ± SEM of triplicate samples. Similar results were obtained in another independent experiment.

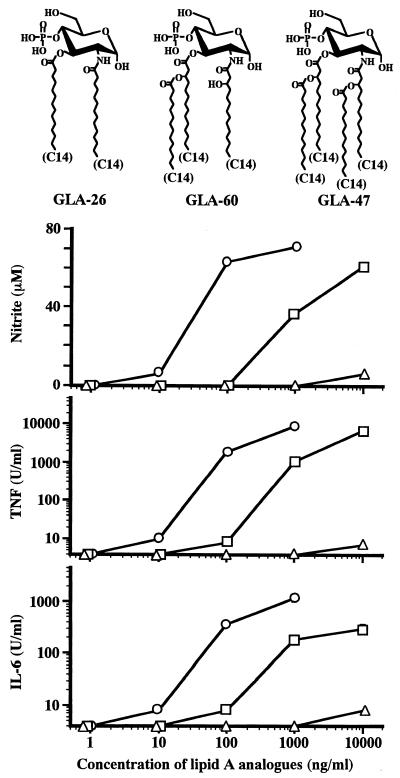

FIG. 2.

Stimulation of RAW264.7 cells for production of NO, TNF-α, and IL-6 by monosaccharide lipid A analogues possessing different numbers of acyl groups. RAW264.7 cells were cultured in the presence of the indicated doses of lipid A analogues. As shown, GLA-26 (▵), GLA-60 (○), and GLA-47 (□) possess 2, 3, and 4 acyl groups, respectively. The amounts of NO, TNF-α, and IL-6 in the culture supernatants at 48 h were determined. The data are the means ± SEM of triplicate samples. A representative result of three independent experiments is shown.

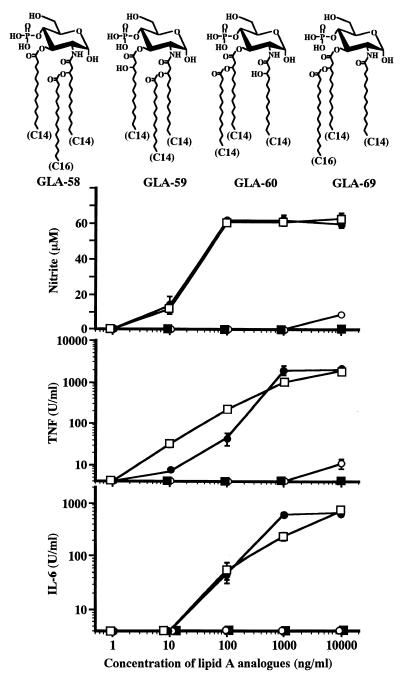

FIG. 3.

Effect of difference in acylation patterns of triacyl monosaccharide lipid A analogues on stimulation of RAW264.7 cells to produce mediators. The experimental procedures were basically the same as those described in the legend to Fig. 2, except for the analogues used. As shown, GLA-58 (■), GLA-59 (□), GLA-60 (•), and GLA-69 (○) are all triacyl monosaccharide analogues, but their acylation patterns are different. The data are the means ± SEM of triplicate samples. Similar results were obtained in two other independent experiments.

Cells and cell culture.

For cell culture, RPMI 1640 medium (Flow Laboratories Co. Ltd., Rockville, Md.) supplemented with 10 mM HEPES, 2 mM l-glutamine, 100 U of penicillin per ml, 100 μg of streptomycin per ml, and 0.2% NaHCO3 (culture medium) was used. Cells from the murine macrophage cell line RAW264.7 (originally from the American Type Culture Collection, Rockville, Md.) were maintained in culture medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (Flow Laboratories) in a humidified chamber at 37°C with 5% CO2. For stimulation experiments with macrophages, culture medium supplemented with 1% fetal calf serum was used. The cells were plated at 5 × 105/0.5 ml/well of 48-well tissue culture plates (Sumitomo Bakelite Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) and incubated for at least 2 h in a cell culture chamber to allow them to adhere to the plates. After being washed three times with 0.5 ml of Hanks’ balanced salt solution (Flow Laboratories)/well, the cells were cultured in culture medium containing stimulants and/or inhibitors (final volume, 0.5 ml/well).

Measurement of NO production.

NO production by the macrophages was measured as nitrite, a stable end product of NO, in the culture supernatant. For the measurement of nitrite, 50 μl of Griess reagent (0.1% N-1-naphthylenediamine dihydrochloride and 1% sulfanilamide in 2.5% phosphoric acid) (6) was added to the same volume of culture supernatant in each well of 96-well plates, mixed, and left at room temperature for 10 min. Absorbance was measured at 540 nm with a Biomek 1000 spectrophotometer (Beckman Instruments, Palo Alto, Calif.), and nitrite concentrations were quantified from the standard curve with NaNO3.

Cytokine assays.

The amounts of TNF-α in the culture supernatants of macrophages were quantified by a cytotoxic assay against L-929 cells (21). Briefly, L-929 cells were precultured in 96-well tissue culture plates (Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark) for 2 to 3 h and then actinomycin D (Sigma Chemicals Co.) at a final concentration of 1 μg/ml and serially diluted test samples were added to the cultures. The viability of the cells after overnight culture was determined by crystal violet staining and by measuring absorbance at 540 nm with the Biomek 1000 spectrophotometer. TNF-α activity (in units per milliliter) was calculated from the dilution factor of test samples necessary for 50% cell lysis, with correction by a recombinant human TNF-α internal standard in each assay.

The production of IL-6 by the macrophages was measured by determining IL-6 activity in the culture supernatants with a proliferation assay of an IL-6-dependent mouse hybridoma cell line, B13.29 (1). Briefly, B13.29 cells in 96-well tissue culture plates (Nunc) were incubated with serial dilutions of test samples in a humidified chamber at 37°C with 5% CO2. After 3 days of incubation, MTT (3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide; Sigma Chemicals), a tetrazolium salt that is converted to formazan blue crystals by metabolically active cells, was added for a further 4 h (19). The supernatant was removed from the wells, and the formazan blue crystals produced by viable cells were dissolved with isopropanol solution containing 5% formic acid. Absorbance was measured at 540 nm with the Biomek 1000 spectrophotometer. IL-6 activity (in units per milliliter) was calculated as the dilution factor required to induce 50% cell growth, with correction by an internal standard of recombinant human IL-6.

Statistical analysis.

Data are expressed as means ± standard errors of the means (SEM) of triplicate samples. All experiments were performed two or three times. The results were analyzed by Student’s t test, and a P value of <0.05 was regarded as statistically significant.

RESULTS

Time course of NO, TNF-α, and IL-6 production by RAW264.7 cells upon stimulation with a synthetic lipid A, 506, and a monosaccharide lipid A analogue, GLA-60.

It was reported that murine macrophage cell lines were useful models to study macrophage synthesis of NO and that a macrophage cell line, RAW264.7, responded well to LPS-induced NO synthesis (24). In the present study, RAW264.7 cells were used to study the abilities of lipid A analogues to induce NO synthesis in relation to their structures. The ability of the analogues to produce cytokines, such as TNF-α and IL-6, was also examined. RAW264.7 cells were stimulated with 506 at 100 ng/ml or GLA-60 at 10 μg/ml, and production of NO, TNF-α, and IL-6 in the culture supernatant was measured at various times thereafter. As shown in Fig. 1, GLA-60 stimulated the cells to produce these three mediators in a manner similar to that of 506. The production of NO was induced by 6 h, peaked at 24 h, and was sustained over 72 h. Production of TNF-α and IL-6 had started by 2 h and peaked at 6 h for TNF-α and at 8 h for IL-6, and both peaks were sustained over 72 h. Based on these results, culture supernatants at 48 h were used for assays of all three mediators in subsequent experiments. When thioglycollate-elicited murine peritoneal macrophages were used instead of RAW264.7 cells, similar results were obtained, although the maximum amounts of NO produced upon stimulation with either 506 or GLA-60 were smaller (about 20 μM) than those produced by RAW264.7 cells (over 60 μM). This weak production of NO by thioglycollate-elicited murine peritoneal macrophages upon stimulation with these compounds was enhanced in the presence of gamma interferon (data not shown), as was reported in the case of LPS stimulation (24).

Effect of the number of attached acyl groups in lipid A analogues on production of NO, TNF-α, and IL-6 by RAW264.7 cells.

The stimulatory effects of monosaccharide lipid A analogues on production of the three mediators were compared by using GLA-26, GLA-60, and GLA-47, which possess 2, 3, and 4 acyl groups, respectively. The chemical structures of these analogues and the results of the experiment are shown in Fig. 2. The strongest stimulatory activity for production of the mediators was exhibited by GLA-60, with three acyl groups. In the production of all three mediators, GLA-60 induced weak, high, and higher production at 10, 100, and 1,000 ng/ml, respectively. Next to GLA-60, GLA-47, with four acyl groups, showed moderate activity. At a concentration of 100 ng of GLA-47/ml, undetectable (NO) or weak (TNF-α and IL-6) production was observed, and at 1,000 and 10,000 ng of GLA-47/ml, high and higher production, respectively, of all three mediators was induced. The activity of GLA-26, with two acyl groups, was much weaker than that of GLA-47. Only weak production of the mediators was induced by GLA-26 at the highest concentration tested (10,000 ng/ml). The ability of each analogue to induce NO synthesis correlated very well with its ability to induce TNF-α and IL-6 production.

Effects of different acylation patterns in triacyl monosaccharide lipid A analogues on production of mediators by RAW264.7 cells.

In addition to GLA-60, mentioned above, three other triacyl monosaccharide lipid A analogues were introduced into experiments, and their activities in the production of the three mediators were compared with those of GLA-60. The structures and activities of these analogues are shown in Fig. 3. In GLA-59, a tetradecanoyl (C14) group attached to the hydroxy (OH) group of the 3-O-linked 3-hydroxy-tetradecanoyl (C14-OH) group in GLA-60 is transferred to the 2-N-linked C14-OH group. In GLA-69 and GLA-58, a hexadecanoyl (C16) group is introduced instead of a C14 group attached to the OH group of the 3-O- and 2-N-linked C14-OH group in GLA-60 and GLA-59, respectively, and a free C14 group instead of a free C14-OH group is introduced in both analogues.

Among the analogues, GLA-59 exhibited strong activities comparable to those of GLA-60 in the induction of the three mediators. GLA-69 exhibited only weak activities, i.e., it induced only weak production of all three mediators at the highest concentration tested. No significant activity of GLA-58 in the induction of the mediators was detected up to the highest concentration tested, 10,000 ng/ml. The activity of each analogue to induce NO synthesis again correlated very well with its activities in TNF-α and IL-6 production. These results suggest that signals for the production of NO in response to stimulation with lipid A analogues are transduced in close relation with those for the production of TNF-α and IL-6.

Effect of anti-TNF-α antibody and PTX on production of NO and IL-6 by stimulation with LPS, 506, or GLA-60.

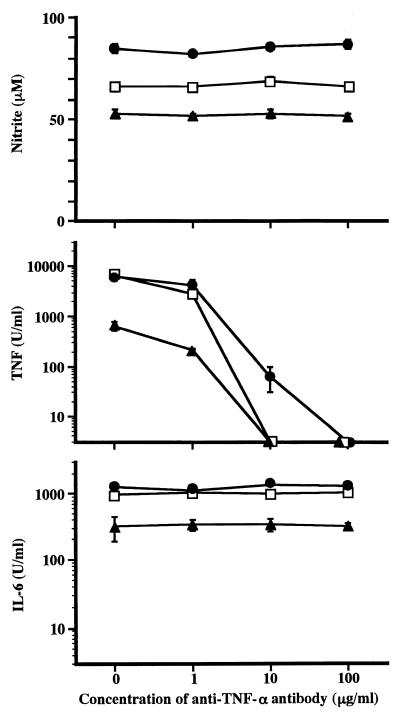

With the three mediators tested in this study, accumulation of TNF-α in the culture supernatant of RAW264.7 cells upon stimulation with 506 and GLA-60 peaked first (6 h), that of IL-6 peaked a little later (8 h), and that of NO peaked much later (24 h) (Fig. 1). To investigate the effect of previously produced TNF-α on the induction of NO synthesis, RAW264.7 cells were stimulated with LPS, 506, or GLA-60 in the presence of anti-mouse TNF-α antibody, and NO in the culture supernatant was measured. The activities of IL-6 and TNF-α in the culture supernatant were also measured. As shown in Fig. 4, anti-mouse TNF-α antibody showed no suppressive effect on the production of NO and IL-6, while it suppressed the TNF-α activity in the culture supernatant in a dose-dependent manner.

FIG. 4.

Effect of anti-TNF-α antibody on production of mediators by RAW264.7 cells upon stimulation with LPS, 506, and GLA-60. RAW264.7 cells were cultured in the presence of the indicated concentrations of anti-TNF-α antibody. The cultures were stimulated 1 h later with LPS (□) at 1 ng/ml, 506 (•) at 1 ng/ml, and GLA-60 (▴) at 100 ng/ml. The amounts of NO, TNF-α, and IL-6 in the culture supernatants at 48 h after stimulation were determined. The data are the means ± SEM of triplicate samples. A representative result of three independent experiments is shown.

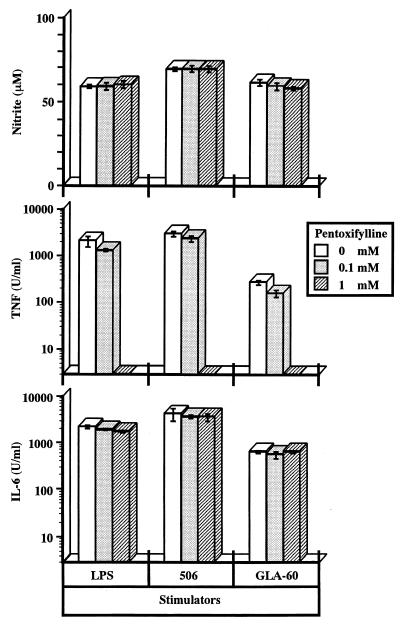

PTX, a methylxanthine compound, has been reported to inhibit TNF-α secretion, but not IL-6 secretion, from LPS-stimulated monocytic cells (22, 23). In the next experiment, RAW264.7 cells were stimulated with LPS, 506, or GLA-60 in the presence of PTX, and the production of NO, TNF-α, and IL-6 in the culture supernatant was measured. Neither the production of NO nor that of IL-6 was suppressed, while a suppressive effect of PTX on TNF-α synthesis was clearly observed (Fig. 5). These results indicate that TNF-α does not participate in the signaling pathways for the production of NO and IL-6.

FIG. 5.

Effect of PTX on production of mediators by RAW264.7 cells upon stimulation with LPS and its agonists. The indicated concentrations of PTX were added to cultures of RAW264.7 cells 1 h before stimulation with LPS at 1 ng/ml, 506 at 1 ng/ml, and GLA-60 at 100 ng/ml. The amounts of NO, TNF-α and IL-6 in the culture supernatants at 48 h after stimulation were determined. The data are the means ± SEM of triplicate samples. A representative result of two independent experiments is shown.

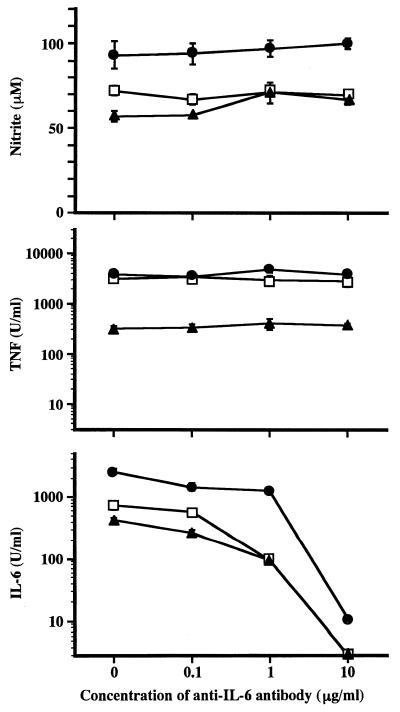

Effect of anti-IL-6 antibody on production of NO and TNF-α by stimulation with LPS, 506, or GLA-60.

To investigate the effect of IL-6 on the production of NO upon stimulation with LPS agonists, RAW264.7 cells were stimulated with LPS, 506, or GLA-60 in the presence of anti-mouse IL-6 antibody, and the amounts of NO in the culture supernatant were measured. In addition, the activities of TNF-α and IL-6 in the culture supernatant were determined. As shown in Fig. 6, the production of NO and TNF-α were not affected by the antibody under the conditions under which the antibody significantly suppressed IL-6 activity in the culture supernatant. These results indicated that IL-6 induced by the stimuli has no effect on the signaling pathways for the production of NO and TNF-α.

FIG. 6.

Effect of anti-IL-6 antibody on production of mediators by RAW264.7 cells upon stimulation with LPS and its agonists. The experimental procedures were the same as those described in the legend to Fig. 4, except for the antibody used (anti-mouse IL-6 antibody) and its concentrations. The data are the means ± SEM of triplicate samples. Similar results were obtained in another independent experiment.

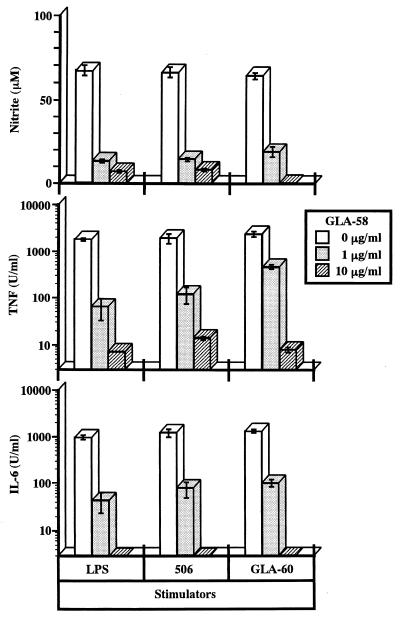

Inhibition of production of the mediators by an inactive lipid A analogue, GLA-58.

A monosaccharide lipid A analogue, GLA-58, showed no activity to induce any of the three mediators examined in this study (Fig. 3). To investigate the antagonistic effect of this compound, RAW264.7 cells were cultured in the presence of the compound and stimulated with LPS, 506, or GLA-60. We observed dose-dependent inhibition by GLA-58 of the production of NO, TNF-α, and IL-6 induced by all three stimulants (Fig. 7). Unlike suppression by cytokine-specific antibodies or PTX, production of all three mediators was simultaneously suppressed by GLA-58. When RAW264.7 cells were stimulated by agents unrelated to LPS, such as zymosan A (Sigma), no inhibitory effect of GLA-58 on the production of NO, TNF-α, or IL-6 was observed (data not shown), indicating that the inhibitory effect of GLA-58 is not the result of its cytotoxic action on RAW264.7 cells.

FIG. 7.

Inhibitory effect of GLA-58 on production of mediators by RAW264.7 cells upon stimulation with LPS and its agonists. RAW264.7 cells were cultured in the presence of the indicated concentrations of GLA-58. Two hours later, LPS at 1 ng/ml, 506 at 1 ng/ml, and GLA-60 at 1 μg/ml were added to the cultures to stimulate the cells. The amounts of NO, TNF-α, and IL-6 in the culture supernatants at 48 h after stimulation were determined. The data are the means ± SEM of triplicate samples. Similar results were obtained in another independent experiment.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we found that the relationships of the structures and activities of monosaccharide lipid A analogues in the induction of NO synthesis by murine macrophage RAW264.7 cells correlates very well with those in the production of proinflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α and IL-6. Among the analogues tested, GLA-60, which possesses three acyl groups and one phosphate group to one saccharide backbone, exhibited the strongest activities to induce NO synthesis as well as TNF-α and IL-6 production. Strong activities similar to those of GLA-60 were exhibited by GLA-59, which is constituted with the same components as GLA-60 but with a different linkage pattern of acyl groups. The ratio of phosphate groups and acyl groups to one saccharide backbone of these analogues (1:3:1) is the same as that of 506 (2:6:2 = 1:3:1), which has the complete disaccharide structure of active lipid A (Escherichia coli type) and the strongest activities among the disaccharide analogues so far synthesized. More-hydrophilic analogues with two acyl groups, like GLA-26, and more-hydrophobic analogues with four acyl groups, like GLA-47, were less active than GLA-60. Even triacylated monosaccharide analogues, GLA-69 and GLA-58, are more hydrophobic than GLA-60 because they have one longer acyl group (C16) and a dehydroxylated acyl group (C14) as components, and their activities were much weaker than those of GLA-60. Dehydroxylation of GLA-60 alone decreased the activities slightly, and lengthening the acyl chain of GLA-60 to C16 alone strongly decreased the activities, although less strongly than when both factors were changed simultaneously, as was the case for GLA-69 (data not shown). These results indicate that such a hydrophobe-hydrophile balance of the molecules plays an important role in the stimulation of the LPS receptor(s) to transduce signals for the production of NO as well as TNF-α and IL-6, and they support the concept that a balanced ratio of hydrophobicity and hydrophilicity is involved in the expression of endotoxic activity (20).

Based on the results of the time course study shown in Fig. 1, the possibility of NO production via TNF-α and/or IL-6 production was considered. However, this was found to be unfeasible, through experiments using antibodies to neutralize the activity of the cytokines (Figs. 4 and 6) and an experiment using PTX to suppress the production of TNF-α (Fig. 5). Considering the well-correlated production of the three mediators, signaling pathways for NO production may share some common parts with those for production of TNF-α and IL-6 in the early stages, and the intensity of signals to produce these three mediators may be determined before the pathways branch to individual ones. In the case of LPS-derived NO production by murine macrophages, inducible NO synthase (iNOS), one of three isoforms of NO synthase, is known to play a role as the catalytic enzyme of NO production from l-arginine (25). Induction of iNOS gene expression and production of iNOS protein are therefore prerequisites for LPS-derived NO production. For the induction of iNOS gene expression, LPS-derived activation of a transcription factor, nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB), which translocates from the cytosol to the nucleus and binds to region 1 in the promoter of the iNOS gene, was reported to play an important role (27). Many LPS-responsive genes, including those of TNF-α and IL-6, are known to share recognition sequences that can be recognized by NF-κB for the activation of gene expression (26). In addition to NF-κB, transcription factors such as NF-IL-6 and activator protein-1 (2) are also known to be activated and to interact with each other in LPS response in macrophages (26). Some common transcription factors activated by LPS and lipid A analogues may play key roles in the expression of all three genes for iNOS, TNF-α, and IL-6. After activation of the expression of these genes, signals for production of each mediator may be transduced independently.

We have previously reported that GLA-58 has the ability to protect mice from LPS lethality under d-galactosamine-sensitized conditions (in vivo protective activity) and that, after pretreatment of murine macrophages with the analogue and washing it out, it also has potency to lead the macrophages into a state that is hyporesponsive to LPS stimulation (in vitro tolerance-inducing activity) (15). In the present study, this analogue showed another ability as an inhibitor (antagonistic activity) to LPS, 506, and GLA-60 for production of NO, TNF-α, and IL-6 when it coexisted with the stimulants (Fig. 7). This was in contrast to the specific suppression of TNF-α by PTX. The broad inhibitory activity of GLA-58 to production of multiple mediators, however, is not due to its cytotoxicity to macrophages, since no such inhibitory activity of GLA-58 was observed when macrophages were stimulated with agents unrelated to LPS, like zymosan A. These results suggest that GLA-58 acts negatively on the signaling pathways of LPS agonists in the early stages before branching into the signals for NO, TNF-α, and IL-6 production.

The present study indicates that the signaling pathways of LPS agonists for NO production in murine macrophages are regulated in good correlation with those for the production of proinflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α and IL-6, although the cytokines do not participate in the signals for NO production.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported in part by grant 09670295 from the Ministry of Education, Science and Culture of Japan.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aarden L A, de Groot E R, Shaap O L, Lansdorp P M. Production of hybridoma growth factor by human monocytes. Eur J Immunol. 1987;7:1411–1416. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830171004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dendorfer U, Oettgen P, Libermann T A. Multiple regulatory elements in the interleukin-6 gene mediate induction by prostaglandins, cyclic AMP, and lipopolysaccharide. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:4443–4454. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.7.4443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Flad H-D, Loppnow H, Rietschel E T, Ulmer A J. Agonists and antagonists for lipopolysaccharide-induced cytokines. Immunobiology. 1993;187:303–316. doi: 10.1016/S0171-2985(11)80346-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Galanos C, Lüderitz O, Rietschel E T, Westphal O, Brade H, Brade L, Freudenberg M, Shade U, Imoto M, Yoshimura H, Kusumoto S, Shiba T. Synthetic and natural Escherichia coli lipid A express identical endotoxic activities. Eur J Biochem. 1985;148:1–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1985.tb08798.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Galanos C, Lüderitz O, Westphal O. Preparation and properties of a standardized lipopolysaccharide from Salmonella abortus equi. Zentbl Bakteriol Mikrobiol Hyg 1 Abt Orig A. 1979;243:226–244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Green S J, Wagner D A, Glogowski J, Skipper P L, Wishnok J S, Tannenbaum S R. Analysis of nitrite, and [15N]nitrate in biological fluids. Anal Biochem. 1982;126:131–138. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(82)90118-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Homma J Y, Matsuura M, Kanegasaki S, Kawakubo Y, Kojima Y, Shibukawa N, Kumazawa Y, Yamamoto A, Tanamoto K, Yasuda T, Imoto M, Yoshimura H, Kusumoto S, Shiba T. Structural requirements of lipid A responsible for the functions: a study with chemically synthesized lipid A and its analogues. J Biochem. 1985;98:395–406. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a135294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Homma J Y, Matsuura M, Kumazawa Y. Studies on lipid A, the active center of endotoxin—structure-activity relationship. Drugs Future. 1989;14:645–665. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kiso M, Tanaka S, Fujishima M, Ogawa Y, Hasegawa A. Synthesis of nonreducing sugar subunit analogues of bacterial lipid A carrying an amide-bound (3R)-3-acyloxytetradecanoyl group. Carbohydr Res. 1987;162:247–256. doi: 10.1016/0008-6215(87)80207-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kiso M, Tanaka S, Fujita M, Fujishima Y, Ogawa Y, Ishida H, Hasegawa A. Synthesis of the optically active 4-O-phosphono-d-glucosamine derivatives related to the non-reducing sugar subunit of bacterial lipid A. Carbohydr Res. 1987;162:127–140. doi: 10.1016/0008-6215(87)80207-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kotani S, Takada H, Tsujimoto M, Ogawa T, Takahashi I, Ikeda T, Otsuka K, Shimauchi H, Kasai N, Mashimo J, Nagao S, Tanaka A, Tanaka S, Harada K, Nagaki K, Kitamura H, Shiba T, Kusumoto S, Imoto M, Yoshimura H. Synthetic lipid A with endotoxic and related biological activities comparable to those of a natural lipid A from an Escherichia coli Re-mutant. Infect Immun. 1985;49:225–237. doi: 10.1128/iai.49.1.225-237.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kumazawa Y, Nakatsuka M, Takimoto H, Furuya T, Nagumo T, Yamamoto A, Homma J Y, Inada K, Yoshida M, Kiso M, Hasegawa A. Importance of fatty acid substituents of chemically synthesized lipid A-subunit analogues in the expression of immunopharmacological activity. Infect Immun. 1988;56:149–155. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.1.149-155.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Manthey C L, Vogel S N. The role of cytokines in host response to endotoxin. Rev Med Microbiol. 1992;80:146–159. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Matsuura M, Kijima Y, Homma J Y, Kubota Y, Shibukawa N, Shibata M, Inage M, Kusumoto S, Shiba T. Interferon-inducing, pyrogenic and proclotting enzyme of horseshoe crab activation activities of chemically synthesized lipid A analogues. Eur J Biochem. 1983;137:639–642. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1983.tb07873.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matsuura M, Kiso M, Hasegawa A, Nakano M. Multistep regulation mechanisms for tolerance induction to lipopolysaccharide lethality in the tumor-necrosis-factor-α-mediated pathway. Application of non-toxic monosaccharide lipid A analogues for elucidation of mechanisms. Eur J Biochem. 1994;221:335–341. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1994.tb18745.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Matsuura M, Shimada S, Kiso M, Hasegawa A, Nakano M. Expression of endotoxic activities by synthetic monosaccharide lipid A analogs with alkyl-branched acyl substituents. Infect Immun. 1995;63:1446–1451. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.4.1446-1451.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moncada S, Palmer R M, Higgs E A. Nitric oxide: physiology, pathophysiology, and pharmacology. Pharmacol Rev. 1991;43:109–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morrison D C, Ryan J L. Endotoxins and disease mechanisms. Annu Rev Med. 1987;38:417–432. doi: 10.1146/annurev.me.38.020187.002221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mosman T. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: application to proliferation and cytotoxic assays. J Immunol Methods. 1983;65:55–63. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(83)90303-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rietschel E T, Brade H, Brade L, Brandenburg K, Schade U, Seydel U, Zähringer U, Galanos C, Lüderitz O, Westphal O, Labishenski H, Kusumoto S, Shiba T. Lipid A, the endotoxic center of bacterial lipopolysaccharides: relation of chemical structure to biological activity. Prog Clin Biol Res. 1987;231:25–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ruff M R, Gifford G E. Purification and physiological characterization of rabbit tumor necrosis factor. J Immunol. 1980;125:1671–1677. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schandene L, Vabdenbussche P, Crusiaux A, Alègre M-L, Abramowicz D, Dupont E, Content J, Goldman M. Differential effects of pentoxifylline on the production of TNF-alpha and IL-6 by monocytes and T cells. Immunology. 1992;76:30–34. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Strieter R M, Remick D G, Ward P A, Spengler R N, Lynch I, Larrick J, Kunkel S L. Cellular and molecular regulation of tumor necrosis factor-alpha production by pentoxifylline. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1988;30:1230–1236. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(88)81271-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stuehr D J, Marletta M A. Synthesis of nitrite and nitrate in murine macrophage cell lines. Cancer Res. 1987;47:5590–5594. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stuehr D J, Nathan C F. Nitric oxide: a macrophage product responsible for cytostasis and respiratory inhibition in tumor target cells. J Exp Med. 1989;169:1543–1555. doi: 10.1084/jem.169.5.1543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sweet M J, Hume D A. Endotoxin signal transduction in macrophages. J Leukoc Biol. 1996;60:8–26. doi: 10.1002/jlb.60.1.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xie Q-W, Kashiwabara Y, Nathan C. Role of transcription factor NF-κB/Rel in induction of nitric oxide synthase. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:4705–4708. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]