Abstract

Objective:

This study was designed to examine 1) whether ovarian cancer (OC) survivors would have greater well-being vs. elevated distress compared to community members during a universal health stressor (COVID-19) and 2) how resources and risk factors at diagnosis predicted vulnerability to a subsequent health-related stressor.

Methods:

117 OC survivors were recruited from two academic medical centers and compared to a community-based sample on COVID-related distress and disruption. Latent class analysis identified differentially impacted groups of survivors.

Results:

Survivors reported lower distress than community members. Predictors of higher distress included shorter-term survivorship, greater disruption, and poorer emotional well-being (EWB) at diagnosis. Survivors were divided into high- and low-COVID-19-impact subgroups; high-impact individuals endorsed higher perceived stress and lower EWB at diagnosis.

Conclusion:

Survivors reported lower COVID-related distress than community participants. While depression at diagnosis did not predict later distress, EWB was a strong predictor of response to a novel health-related stressor.

Keywords: stress, ovarian cancer, COVID-19, distress, well-being

1.0. Introduction

Ovarian cancer (OC) is the fifth-leading cause of cancer-related death among women with a 49% overall five-year survival rate and a 31% five-year survival rate for advanced stages1. Before treatment, patients have reported high levels of distress, with approximately one in four reporting anxiety and depression at clinically diagnostic levels2 and a subset of patients identifying cancer as a traumatic event that generated lasting stress response over time3. However, even within this high-risk population, positive well-being and strong coping skills following diagnosis have been observed in some patients4,5. Enhanced coping in cancer survivors has been associated with better quality of life and treatment outcomes, and lower distress6. However, there is limited understanding regarding what factors promote healthier coping and well-being in survivors during the course of cancer diagnosis, treatment, and survivorship.

While distress and emotional well-being are often conceptualized as opposite ends of a single continuum, they have also been described as distinct aspects of mental functioning that operate independently7,8. Recent research supports treating distress and well-being independently in predicting longitudinal psychosocial and health outcomes, rather than assuming that a lack of distress represents presence of well-being9,10. Positive psychological factors such as optimism, hopefulness, and mastery have been associated with better long-term health trajectories in older adults11, and resilient coping in adolescents has demonstrated potential protective effects against deleterious health outcomes associated with adverse childhood events12. While substantial research has described predictors of distress and longitudinal patterns of distress in OC survivors13–15, it is unclear whether the experience of cancer may engender more effective coping skills in survivors or, alternately, induce greater vulnerability to future stressors.

Many long-term OC survivors have described positive psychological factors (e.g., life purpose, religious or spiritual resources, and positive reinterpretation of events) as key to their well-being and survival16,17. Although adversity can be associated with negative psychological outcomes, exposure to some adversity may produce subsequent resilient psychological functioning 18–21. The contribution of a cancer patient’s positive well-being to their responses to stressors over time and the role it may play in their response to new stressors has not been well characterized. As the stress response has been shown to be closely linked to multiple pathways of ovarian tumor progression22, an individual’s propensity to respond to stress in particular ways may have biological as well as psychological sequelae.

The COVID-19 pandemic presented a unique opportunity to examine responses by OC survivors to a universal health-related stressor. The pandemic has been associated with high levels of psychological distress in the general population, with one in three adults reporting COVID-19-related distress23. The likelihood of distress was increased for participants considered high risk due to pre-existing physical conditions, such as OC24. Recent research among OC patients has reported utilization of both adaptive and dysfunctional coping mechanisms for COVID-19, highlighting heterogeneity in functioning and well-being25. Cross-sectional studies have reported high levels of health-related quality of life (HRQOL) and benefit-finding with little COVID-19-related disruption among cancer patients26,27. The conflicting results of these studies suggest that there may be both survivors who are at increased risk of distress compared to the general population following stressors, as well as survivors who are less vulnerable. However, no research has elucidated what predictors may determine whether a survivor will be high- or low-risk for future psychological suffering.

Our primary objective was to examine the extent to which the previous experience of having OC would enhance survivor outcomes in the face of a universal health stressor (threat of COVID-19) as compared to the general population and how resources and risk factors at diagnosis predicted the subsequent response to COVID-19 among OC survivors. To this end we compared psychological responses of OC survivors to the COVID-19 pandemic to the response in a female non-cancer community population. Our second objective was to examine how survivor responses to COVID-19 varied in accordance with their initial response to diagnosis. Although we considered the possibility that cancer survivors might experience heightened distress in response to a universal health-related stressor28, as noted above, prior cross-sectional research suggested otherwise—reporting high levels of resilience in OC patients during the pandemic26. Accordingly, we hypothesized that OC survivors, having negotiated a previous health stressor, would demonstrate less distress as compared to females in the general population. Further, we hypothesized that healthier emotional responses to the pandemic would be predicted by higher levels of emotional well-being resources and lower distress at diagnosis. Given conflicting prior literature about levels of distress in this population, we also conducted an exploratory analysis to identify subclasses of survivors with varying degrees of COVID-related impact and determine how they differed at diagnosis.

2.0. Materials and Methods

Institutional Review Boards from each participating site approved all study procedures (IRB Approval University of Iowa #201507805, 200308061, 201911073, and 20190790, Washington University at St. Louis #201511102 and 201104242). Written informed consent was obtained from all study participants.

2.1. Participants

2.1.1. OC Survivors

Participants were drawn from three ongoing studies based at a large midwestern tertiary cancer center. The first (Cohort 1) was a long-term survivor study conducted at two midwestern academic tertiary cancer centers following OC survivors who were at least four years post-diagnosis (N = 46). The second (Cohort 2) was a longitudinal study at the same sites that followed OC survivors from diagnosis over the first 5 years post diagnosis (N = 47). The third (Cohort 3) was a multisite intervention study that recruited OC survivors less than 3 years post treatment, with no more than one recurrence, not currently receiving chemotherapy, and willing to participate in a randomized trial (N = 24). Eligibility for all studies was restricted to survivors over 18 years of age with a primary diagnosis of epithelial ovarian, peritoneal, or fallopian tube carcinoma. Survivors were excluded from the study if they were pregnant, diagnosed with benign disease, nonepithelial malignancies, tumors of low malignant potential, or had a previous cancer diagnosis within the last 5 years.

Participants in the first two cohorts completed baseline psychosocial questionnaires between recruitment and surgery or neoadjuvant treatment initiation and completed COVID surveys by mail between May and December 2020. Participants in Cohort 3 completed online surveys including the COVID survey at study entry, prior to randomization for the intervention study and between October 2020 and May 2021. In total, 86% of surveys were returned by December 31st, 2020. The final sample included 117 survivors who had at least 75% of data available. Because survivors in the intervention study completed baseline psychosocial surveys at the same time as their COVID-19 questionnaire and not at diagnosis, these survivors were not included in prospective analyses, leaving 93 survivors in prospective analyses.

2.1.2. Community sample

The comparison group was recruited from the general Iowa population between August and December of 2020. Full details are available in Greteman et al., 202229 and a brief summary is available in supplemental methods. Briefly, female respondents without cancer between 18 and 93 years of age were selected for comparison to OC survivors, leaving a final community sample of 1110 women. Rurality for both OC survivors and community participants was assessed using Rural-Urban Continuum Codes, with 1–3 considered “urban” and 4–9 considered “non-urban.”

2.2. Psychosocial Measures

2.2.1. Emotional Well-Being

The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy – General (FACT-G) is a 27-item validated questionnaire which assesses four domains of health-related quality of life in cancer survivors: emotional, social, physical, and functional30. This analysis focused on the emotional well-being subscale which assesses cancer-related hope, coping, and worries. It consists of six questions scored from 0 (not at all) to 4 (very much) summed, where higher scores indicate greater levels of well-being.

2.2.2. Perceived Stress

The Perceived Stress Scale is a widely-used instrument for measuring perception of stress over the past month31. The scale consists of 14 items scored from 0 (never) to 4 (very often), where a higher score indicates greater levels of perceived stress.

2.2.3. Depression

The Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression (CES-D) Scale is a validated 20-item self-report scale assessing frequency of depressive symptoms during the previous week32. Items are scored from 0 (rarely or none of the time) to 4 (most or all of the time); higher scores indicate greater depressive symptoms.

2.2.4. COVID-19 Response

The COVID-19 Impact of the Pandemic and HRQOL in Cancer Patients and Survivors questionnaire, a 43-item survey developed to assess pandemic impact and HRQOL33 consists of three sections: COVID-19 experiences, COVID-19 psychosocial and practical experiences, and HRQOL. The first section assesses virus exposure by both survivor and family, risk factors, COVID-related safety behaviors, and impact on financial stability and medical appointments. The second section consists of 43 Likert-style questions answered from 0 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). These questions assess COVID-19 Specific Distress (Emotional and Physical Reactions), Disruption to Daily Activities and Social Interactions, Financial Hardship, Perceived Benefits, Functional Social Support, and Perceived Ability to Manage Stress. The final section consists of seven questions scored 0 (not at all) to 4 (very much) assessing HRQOL. The subscales used here include the COVID-19 Specific Distress (α=.90), COVID-19 Disruption Composite Score (α=0.85), and Depression Subscale (α = 0.79). Psychometrics have been examined in a validation sample of 11,120 cancer survivors with acceptable internal consistency (α’s=0.609–0.894)34.

2.3. Clinical and Demographic Information

Demographic information was collected by self-report following the pre-surgical/treatment clinic appointment for survivors in observational studies, and study entry for survivors in the intervention study. Clinical information was extracted from medical records in the observational studies and by self-report in the intervention study.

2.4. Statistical Analyses

Analysis of Variance was used to compare OC survivors to the community population and to compare survivors by stage and time since diagnosis. Missing data less than 15% (most categories fell below 5% of the total) were imputed using the Multivariate Imputation by Chained Equations (MICE) package in RStudio version 1.4.1103 based on random forests. Within OC survivors, hierarchical regressions were used to examine effects of baseline psychosocial variables on COVID-19 distress, adjusting for a priori covariates (age, cancer stage, total COVID-related disruption ([healthcare and daily-life disruptions and financial hardship] and time since diagnosis). Among all survivors, higher levels of COVID-related disruption were associated with significantly higher COVID-related distress (r =.632, p<.001); thus, total COVID-related disruption was controlled for in all primary analyses to ensure we were targeting subjective response and not objective hardship. To address the exploratory hypothesis regarding risk groups, latent class analyses to evaluate subgroups of COVID-19 impact were performed using Mplus version 8.335. These analyses included all factors assessed in the COVID impact scale, including reported distress, lack of benefit-finding, and COVID-19-related disruption. Latent class models were computed on an item-level basis, including all items from the COVID-19 survey assessing survivor-reported COVID-19 psychosocial and practical experiences; class membership was then used for comparison on baseline psychosocial status and disease characteristics. The sample size was small but acceptable for a latent class analysis with a relatively high number of quality indicators and the model showed good differentiation between classes, justifying the exploratory analysis for this size of sample36.

3.0. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

3.1.1. OC Survivor Demographics

As seen in Table 1, average age at baseline was 63.4 years (SD=11.3, range=37–93). Slightly more than half of survivors (54.7%) had advanced stage disease. For Cohort 1 (long-term survivors), average time since diagnosis was around ten years (M=10.66±2.76 years, range=6.42–15.92). Average time since diagnosis did not differ significantly (p=.84) between survivors in Cohort 2 (1.74±1.06 years) and Cohort 3 (M=1.68±0.96 years); these were categorized together as shorter-term survivors (overall M=1.72±1.02 years, range=0–3.75) for comparison with long-term survivors. While 32.5% (N=38) of survivors reported being tested for COVID-19, only two patients reported a positive test. The population had large minority of rural patients, with 32.5% (N=38) living in non-urban communities.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of OC survivors and community participants

| Measure | Survivors N = 117 | Community Participants N = 1110 |

|---|---|---|

| Age in years | ||

| Mean (SD; Range) | 63.52 (11.11; 37 – 93) | 60.82 (12.88; 37 – 93) |

|

| ||

| Race | ||

| White | 113 (96.6%) | 1056 (95.1%) |

| Native American | 1 (0.9%) | 5 (0.5%) |

| Asian | 2 (1.7%) | 11 (1.0%) |

| Black | 0 | 11 (1.0%) |

| Nat. Hawaiian/Pacific | 0 | 1 (0.1%) |

| Islander | ||

| Other | 0 | 8 (0.7%) |

| Unknown | 1 (0.9%) | 18 (1.6%) |

|

| ||

| Ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic | 4 (3.4%) | 14 (1.3%) |

| Non-Hispanic | 88 (75.2%) | 991 (1.3%) |

| Unknown | 25 (21.4%) | 105 (9.5%) |

|

| ||

| Stage | ||

| Stage I | 35 (29.9%) | |

| Stage II | 17 (13.7%) | |

| Stage III | 49(41.9%) | |

| Stage IV | 16 (13.7%) | |

|

| ||

| CESD | ||

| Mean (SD; Range) | 15.59 (8.58; 0 – 40) | |

|

| ||

| Perceived Stress Scale | ||

| Mean (SD; Range) | 22.02 (7.01; 8 – 37) | |

|

| ||

| Emotional Well-Being | ||

| Mean (SD; Range) | 16.61 (4.38; 4 – 24) | |

3.1.2. Demographics of Community Participants

The average age of community participants at the time of survey completion was 60.8 years (SD=12.9, range=37–93). COVID-19 diagnosis was rare with only 1.6% (N=18) reporting a positive test, although 20.6% (N=229) had been tested for the virus. The population was highly rural, with 56.7% of participants living in a rural area (N=629). The sample was largely white and non-Hispanic (86%, N=955).

3.2. Distress and Disruption in OC and Community Participants

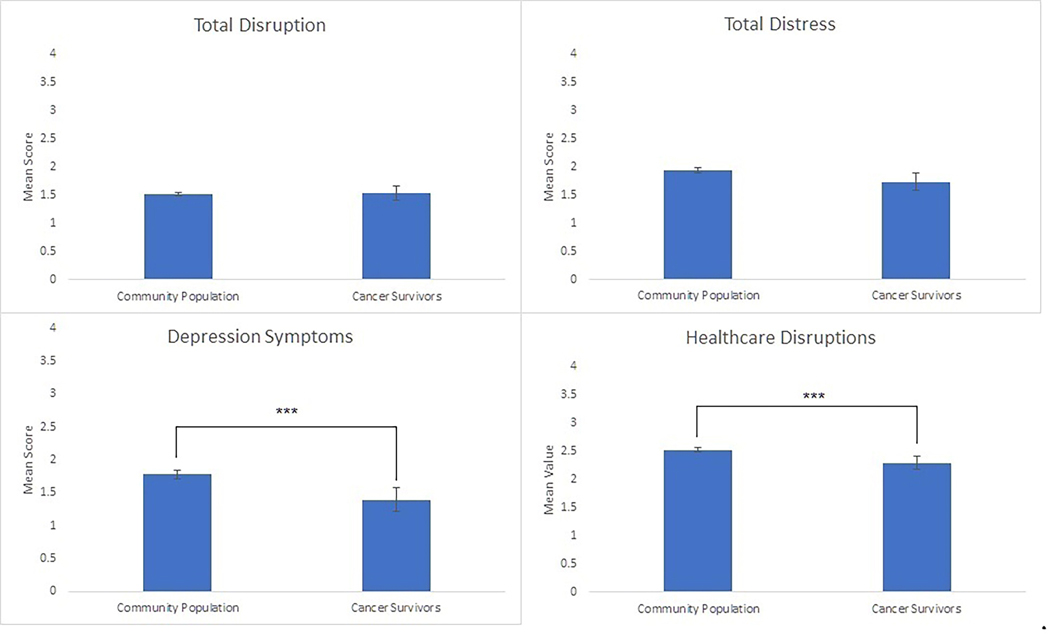

COVID-19-related general disruptions did not differ between OC survivors and community participants (p>.99) (Figure 1). OC survivors reported slightly lower COVID-19 related distress than the community sample (p=.07). Although there were no differences between groups in reported anxiety at the time of the pandemic (p=.90), OC survivors reported significantly lower levels of depressive symptoms (p=.0007) and fewer healthcare disruptions (p=.001) than the community sample, despite similar levels of overall disruption. Sensitivity analyses to evaluate changes in responses secondary to vaccine availability were conducted by removing 13 survivors surveyed after January 1st 2021; results did not substantially differ.

Figure 1.

OC Survivors as compared to a community sample on COVID-related symptoms, distress, and disruptions. Means and 95% CI depicted.

***p<.001

3.3. Distress and Disruption Among OC Survivors

Levels of COVID-related distress did not differ between long-term and shorter-term survivors (p=.17), or between the 3 cohorts of OC survivors (p=.36). Long-term survivors reported lower levels of total COVID-related disruption (M=0.98±0.52) than short-term survivors (M =1.26±0.62, p=.02). Neither COVID-related disruption (p=.32) nor COVID-related distress (p=.11) differed between survivors with early vs advanced-stage disease.

3.4. Association of Baseline psychosocial characteristics with COVID-related distress and disruption.

Table 2 presents linear regressions examining the contribution of perceived stress, depressive symptoms, and emotional well-being at baseline to COVID-related distress. Neither age nor stage was a significant predictor of COVID-19-specific distress. Higher levels of overall COVID-related disruption were associated with significantly higher levels of COVID-19 specific distress in each model. Neither perceived stress (β=.145, p=.186) nor depression (β=.131, p=.240) at baseline significantly predicted COVID-specific distress adjusting for covariates and disruption. Higher baseline EWB predicted lower levels of COVID-19-specific distress (β= −.327, p<.001), adjusting for covariates.

Table 2.

Regression for baseline psychosocial characteristics predicting COVID-19-specific distress.

| Predictor | B (SE) | Beta | t | Adj. ΔR2 | p | Adj. p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Total Disruption | .829 (.122) | .598 | 6.772 | .379 | <.001** | <.001** |

| Stage | .049 (.063) | .067 | .776 | .440 | .686 | |

| Time since diagnosis | .000 (.001) | .031 | .359 | .721 | .922 | |

| Age | −.006 (.006) | −.082 | −.942 | .349 | .576 | |

|

| ||||||

| CESD | .011 (.007) | .131 | 1.538 | .389 | .128 | .240 |

| PSS | .017 (.010) | .145 | 1.674 | .392 | .098 | .186 |

| EWB | −.060 (.015) | −.327 | −4.009 | .470 | <.001** | <.001** |

Following covariates are results for three separate hierarchical regressions. The final column shows p-values adjusted for multiple comparisons.

p<.01

3.5. Latent Class Model: Groups Identified

Latent Class models were used to categorize COVID impact. Fit statistics for the three LCA solutions tested for COVID-19 psychosocial and practical experiences are shown in Supplemental Methods. Taken together, fit statistics support a 2-class model solution, described as high and low COVID-19 impact.

More than half the survivors (56%, n=52) were in the high COVID-19 impact group and reported moderate anxiety, concern about infecting others, concern their cancer would increase their risk from COVID-19, and higher levels of social isolation and social disruption. Further detail is available in supplemental results. Generally, this high-impact class of survivors can be conceptualized as having had more psychological distress as a result of the pandemic and having experienced higher levels of practical disruption.

The low COVID-19 impact group consisted of 41 survivors (44%) who reported lower levels of anxiety, less concern about infecting others or concern about their cancer increasing their risk, and low social isolation. These survivors can be observed broadly to have low levels of reported practical concerns and to report low levels of psychological distress in response to the pandemic.

3.6. Latent Class Comparisons at Baseline

To evaluate idiographic person-level factors, latent class members were compared on each predictor at baseline to observe whether baseline differences might vary between highly impacted survivors and those less impacted.

Clinically, the groups showed no difference in cancer stage (p=.151), with early- and advanced-stage survivors equally likely to be members of either the high- or low-impact group. Additionally, the two groups of survivors did not differ in time between diagnosis and the COVID-19 survey administration (p=.278). However, the high-impact group (M=61.2±11.1 years) was significantly younger than the low-impact group (M=68.4±10.4 years; p=.006).

High-impact survivors (M=15.35±10.16) and low-impact survivors (M=13.74±7.79) did not differ on baseline levels of depressive symptoms (p=.79), and both groups reported a mean level of baseline symptoms below the CESD clinical cutoff of 16 for moderate depressive symptomatology. The high-impact group (M=22.79±6.94) reported significantly higher levels of baseline perceived stress (p=0.05) than the low-impact group (M=19.41±6.23), with both groups reporting baseline levels in the moderate range of perceived stress. Additionally, the high-impact group reported significantly lower levels of emotional well-being (M=15.29±4.44) than the low-impact group (M=17.68±3.91; (p=.02) at baseline. Thus, while perceived stress and age did not appear to be predictors of distress at a population-level, comparisons through an idiographic lens show that these factors did impact the likelihood of a survivor being in the high-impact group. Notably, depression remained a poor predictor of emotional status during COVID-19, while emotional well-being at baseline still strongly predicted response to the pandemic overall.

4.0. Discussion

A key finding of this study is that OC survivors reported lower levels of depression and healthcare-related disruptions compared to a community sample without cancer, despite similar levels of pandemic-related overall disruption. Additionally, OC survivors who reported higher levels of emotional well-being at diagnosis subsequently reported better coping and lower levels of COVID-related distress during the pandemic, over and above the impact of COVID-related disruption. While the level of total disruption was a strong predictor of COVID-19 related distress, depression at baseline was not predictive of emotional response to the pandemic. However, across the full sample, emotional well-being at baseline served as a protective factor against later levels of distress in response to COVID-19, adjusting for disruption, suggesting the relative importance of emotional resources and psychological well-being in coping with new stressors. When examined at the individual level, a high impact group emerged that showed greater susceptibility to stressors. This group was characterized by lower levels of emotional well-being at study entry, consistent with the population-level analyses, and additionally showed higher levels of perceived stress at baseline.

It has been previously observed that OC survivors are remarkably resilient in the face of a life-threatening disease4,37. However, this study was one of the first to compare this population to a non-cancer community population in response to a universal health stressor and to evaluate the role of experience with a cancer diagnosis as a potential source of enhanced coping. Previous work has identified the phenomenon of increased resilience associated with moderate levels of lifetime stress exposure in breast cancer survivors38, suggesting that resilient well-being develops through adversity rather than a lack of stress. We see support here for this notion as well, where the presence of a current or previous diagnosis of OC appeared to serve as a protective factor against the distress of COVID-19 as compared to the distress reported by a community population. This suggests that in the OC survivors, the presence of a previous major life stressor potentially served as an exposure requiring psychological adaptation, enabling the further development of resources for future coping18,19.

Among OC survivors, the factors identified at the time of diagnosis that predicted response to a later stressor were only partially congruent with our expectations. Emotional distress at baseline, assessed through depressive symptoms, was not predictive of later response to a novel stressor. It has been previously reported that psychological distress following diagnosis can be transient, with most OC survivors having similar emotional quality of life to the general population one year after diagnosis39. While distress is salient in this population and is considered a potential target of intervention40, less work has focused on how psychological resources and emotional well-being might support emotional recovery throughout treatment and subsequently. As previously highlighted, ovarian cancer survivors demonstrate very disparate psychological outcomes. Prior to this, risk factors for those survivors who go on to experience greater suffering have not been identified. While there are likely other factors that should be considered in future work, our results here highlight preliminary risk factors that differentiate high- and low-risk survivors.

When examined for clusters of risk factors within OC survivors, two differently affected groups arose in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. We identified a high-impact and a low-impact group that differed on perception of disruption and emotional response. These two groups showed no differences in depression at baseline (as was observed in the overall population); however, at the time of diagnosis the high-impact group had significantly poorer emotional well-being, was younger, and reported significantly higher perceived levels of stress. These results suggest that within this generally resilient population there exists a high-risk subgroup of survivors who lack resources for coping with stressors and who show worse outcomes in response to a new, unique stressor, supporting the role of emotional well-being in coping with future stressors. The identification of a survivor subgroup lacking in well-being at diagnosis that then shows poor coping and worse outcomes in response to a new, unique stressor suggests the need for including assessment of well-being in primary clinical risk assessment. Future research would benefit from a qualitative or mixed-methods study to assess survivor perspectives on what elements contribute to their current levels of distress or emotional well-being. Incorporating such findings in conjunction with the measures used here would allow for broader and more comprehensive assessment of well-being. Additionally, qualitative methods would allow for more nuanced understanding of potentially counterintuitive findings observed here and in other work such as better psychological functioning in cancer survivors and decreasing rates of depression during COVID-19.

4.1. Limitations

The current study consisted of a sample that was largely homogeneous in terms of race, ethnicity, age, and region. The primary source of diversity in this sample was representation of a group that was largely older and substantially rural, providing a unique insight into the experiences of those demographics. As emotional well-being and resiliency resources can be highly culturally-dependent, relationships observed here should be replicated in more diverse populations.

While disease stage was used as a proxy for severity, symptom severity was not assessed. Associations of somatic symptom severity and well-being measures at baseline could explain some of the disparities seen in response to COVID. Additionally, the emotional well-being measure of the FACT does include a minority of items that address psychological distress in addition to most items concerning well-being. Although construct contamination is common in well-being measures, this may limit ability to fully differentiate between ill-being and well-being.

While every effort was made to address potential confounding factors, there are unmeasured aspects that may have influenced the outcomes of these survivors. Non-cancer related health issues and comorbidities were not assessed in this study and may have had independent associations with well-being and long-term psychological outcomes. Other sociodemographic factors that were not assessed, such as income, employment status, and employment exposure to COVID-19 (e.g. front-line workers) may impact pandemic response. These results are limited by those covariates measured and included and represent only a small fraction of potential factors that may impact emotional well-being and long-term distress.

Community participants were exclusively Iowa residents, who may have not reflected the mental health and COVID-related disruption and distress of the nation at large. In contrast, OC survivors were predominantly from Iowa, but included women from other states. However, the community sample comprises a heterogeneous group of both urban and rural residents, allowing for reasonable comparison to draw conclusions.

4.2. Conclusions and Clinical Implications

OC survivors showed remarkable psychological well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic as compared to a community sample. Poor emotional well-being at the time of diagnosis was a risk factor for later emotional distress. While anxiety and depression remain salient risk factors for cancer survivors, care for these individuals should also include screening for well-being resources at the time of diagnosis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

We express our appreciation Amy Weisguth and study participants for their contributions to this research.

Funding sources:

This project was supported in part by NIH grants CA193249, CA246540 (SL); CA109298 and CA209904 (AKS) and the American Cancer Society (AKS), the University of Iowa Holden Comprehensive Cancer Center 3P30CA086862, the University of Iowa Holden Comprehensive Cancer Center COVID-19 Supplement Grant 3P30CA086862-19S5, and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the NIH, Award number UL1TR002537.

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not represent the official views of the NIH.

Footnotes

Statements and Declarations:

Conflict of interest:

Dr. Thaker has done consulting for Merck, Astra Zeneca, Clovis, Glaxo Smith Kline, Eisai, Mersana, Seagen, Agenus, Novocure, Immunogen, Celsion, and Aadi Pharmaceuticals, has research funding from Merck and Glaxo Smith Kline, and is a Celsion shareholder; Dr. Sood has done consulting for Merck, Glaxo Smith Kline, ImmunoGen, Onxeo, and Kiyatec, is a Biopath shareholder, and has received royalties from Top Alliance.

Data availability:

The participants of this study did not give written consent for their data to be shared publicly, so due to the sensitive nature of the research supporting data is not available.

References

- 1.Cancer Survivors in the United States: Prevalence across the Survivorship Trajectory and Implications for Care | Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention | American Association for Cancer Research. Accessed April 20, 2022. https://aacrjournals.org/cebp/article/22/4/561/69861/Cancer-Survivors-in-the-United-States-Prevalence [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Watts S, Prescott P, Mason J, McLeod N, Lewith G. Depression and anxiety in ovarian cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence rates. BMJ Open. 2015;5(11):e007618. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-007618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Deimling GT, Kahana B, Bowman KF, Schaefer ML. Cancer survivorship and psychological distress in later life. Psychooncology. 2002;11(6):479–494. doi: 10.1002/pon.614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Molina Y, Yi JC, Martinez-Gutierrez J, Reding KW, Yi-Frazier JP, Rosenberg AR. Resilience Among Patients Across the Cancer Continuum: Diverse Perspectives. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2014;18(1):93–101. doi: 10.1188/14.CJON.93-101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andrykowski MA, Hunt JW. Positive psychosocial adjustment in potential bone marrow transplant recipients: Cancer as a psychosocial transition. Psychooncology. 1993;2(4):261–276. doi: 10.1002/pon.2960020406 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Seiler A, Jenewein J. Resilience in Cancer Patients. Front Psychiatry. 2019;10. Accessed June 13, 2022. 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ryff CD, Dienberg Love G, Urry HL, et al. Psychological Well-Being and Ill-Being: Do They Have Distinct or Mirrored Biological Correlates? Psychother Psychosom. 2006;75(2):85–95. doi: 10.1159/000090892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boehm JK, Peterson C, Kivimaki M, Kubzansky L. A Prospective Study of Positive Psychological Well-Being and Coronary Heart Disease. Health Psychol Off J Div Health Psychol Am Psychol Assoc. 2011;30(3):259–267. doi: 10.1037/a0023124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tan WH, Sheffield J, Khoo SK, Byrne G, Pachana NA. Influences on Psychological Well-Being and Ill-Being in Older Women. Aust Psychol. 2018;53(3):203–212. doi: 10.1111/ap.12297 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huta V, Hawley L. Psychological Strengths and Cognitive Vulnerabilities: Are They Two Ends of the Same Continuum or Do They Have Independent Relationships with Well-being and Ill-being? J Happiness Stud. 2010;11(1):71–93. doi: 10.1007/s10902-008-9123-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Taylor MG, Carr D. Psychological Resilience and Health Among Older Adults: A Comparison of Personal Resources. J Gerontol Ser B. 2021;76(6):1241–1250. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbaa116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hall A, Perez A, West X, et al. The Association of Adverse Childhood Experiences and Resilience With Health Outcomes in Adolescents: An Observational Study. Glob Pediatr Health. 2021;8:2333794X20982433. doi: 10.1177/2333794X20982433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garvin L, Slavich GM, Schrepf A, et al. Chronic difficulties are associated with poorer psychosocial functioning in the first year post-diagnosis in epithelial ovarian cancer patients. Psychooncology. 2021;30(6):954–961. doi: 10.1002/pon.5682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Armer JS, Clevenger L, Davis LZ, et al. Life Stress as a Risk Factor for Sustained Anxiety and Cortisol Dysregulation During the First Year of Survivorship in Ovarian Cancer. Cancer. 2018;124(16):3401–3408. doi: 10.1002/cncr.31570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mirabeau-Beale KL, Kornblith AB, Penson RT, et al. Comparison of the quality of life of early and advanced stage ovarian cancer survivors. Gynecol Oncol. 2009;114(2):353–359. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2009.05.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ketcher D, Lutgendorf SK, Leighton S, et al. Attributions of survival and methods of coping of long-term ovarian cancer survivors: a qualitative study. BMC Womens Health. 2021;21(1):1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12905-021-01476-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alimujiang A, Khoja L, Wiensch A, et al. “I am not a statistic” ovarian cancer survivors’ views of factors that influenced their long-term survival. Gynecol Oncol. 2019;155(3):461–467. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2019.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Seery MD, Holman EA, Silver RC. Whatever does not kill us: Cumulative lifetime adversity, vulnerability, and resilience. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2010;99(6):1025–1041. doi: 10.1037/a0021344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dienstbier RA. Arousal and physiological toughness: Implications for mental and physical health. Psychol Rev. 1989;96(1):84–100. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.96.1.84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lyons DM, Parker KJ. Stress inoculation-induced indications of resilience in monkeys. J Trauma Stress. 2007;20(4):423–433. doi: 10.1002/jts.20265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.O’Leary VE. Strength in the Face of Adversity: Individual and Social Thriving. J Soc Issues. 1998;54(2):425–446. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4560.1998.tb01228.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chang A, Sloan EK, Antoni MH, Knight JM, Telles R, Lutgendorf SK. Biobehavioral Pathways and Cancer Progression: Insights for Improving Well-Being and Cancer Outcomes. Integr Cancer Ther. 2022;21:15347354221096080. doi: 10.1177/15347354221096081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang Y, Kala MP, Jafar TH. Factors associated with psychological distress during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic on the predominantly general population: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS ONE. 2020;15(12):e0244630. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0244630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Momenimovahed Z, Salehiniya H, Hadavandsiri F, Allahqoli L, Günther V, Alkatout I. Psychological Distress Among Cancer Patients During COVID-19 Pandemic in the World: A Systematic Review. Front Psychol. 2021;12:682154. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.682154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Frey MK, Chapman-Davis E, Glynn SM, et al. Adapting and avoiding coping strategies for women with ovarian cancer during the COVID-19 pandemic. Gynecol Oncol. 2021;160(2):492–498. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2020.11.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Javellana M, Hlubocky FJ, Somasegar S, et al. Resilience in the Face of Pandemic: The Impact of COVID-19 on the Psychologic Morbidity and Health-Related Quality of Life Among Women With Ovarian Cancer. JCO Oncol Pract. 2022;18(6):e948–e957. doi: 10.1200/OP.21.00514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Steel JL, Amin A, Peyser T, et al. The benefits and consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic for patients diagnosed with cancer and their family caregivers. Psychooncology. 2022;31(6):1003–1012. doi: 10.1002/pon.5891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gallagher S, Bennett KM, Roper L. Loneliness and depression in patients with cancer during COVID-19. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2021;39(3):445–451. doi: 10.1080/07347332.2020.1853653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Greteman BB, Garcia-Auguste CJ, Gryzlak BM, et al. Rural and urban differences in perceptions, behaviors, and health care disruptions during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Rural Health. n/a(n/a). doi: 10.1111/jrh.12667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cella DF, Tulsky DS, Gray G, et al. The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy scale: development and validation of the general measure. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 1993;11(3):570–579. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1993.11.3.570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24(4):385–396. doi: 10.2307/2136404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A Self-Report Depression Scale for Research in the General Population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1(3):385–401. doi: 10.1177/014662167700100306 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Penedo FJ, Cohen L, Bower JE, Antoni MH. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in cancer survivors. Published online 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Otto A, Saez-Clarke E, Prinsloo S, et al. Development and Initial Psychometric Evaluation of a COVID-related psychosocial experiences questionnaire for cancer survivors. Rev. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Muthen LK, Muthen BO. Mplus User’s Guide. 8th ed. Muthén & Muthén; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wurpts IC, Geiser C. Is adding more indicators to a latent class analysis beneficial or detrimental? Results of a Monte-Carlo study. Front Psychol. 2014;5. Accessed January 16, 2023. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00920 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ahmed-Lecheheb D, Joly F. Ovarian cancer survivors’ quality of life: a systematic review. J Cancer Surviv. 2016;10(5):789–801. doi: 10.1007/s11764-016-0525-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dooley LN, Slavich GM, Moreno PI, Bower JE. Strength through adversity: Moderate lifetime stress exposure is associated with psychological resilience in breast cancer survivors. Stress Health. 2017;33(5):549–557. doi: 10.1002/smi.2739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhou Y, Irwin ML, Ferrucci LM, et al. Health-related quality of life in ovarian cancer survivors: Results from the American Cancer Society’s Study of Cancer Survivors — I. Gynecol Oncol. 2016;141(3):543–549. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2016.04.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yeh ML, Chung YC, Hsu MYF, Hsu CC. Quantifying Psychological Distress among Cancer Patients in Interventions and Scales: A Systematic Review. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2014;18(3):399. doi: 10.1007/s11916-013-0399-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The participants of this study did not give written consent for their data to be shared publicly, so due to the sensitive nature of the research supporting data is not available.