Significance

Radicals play active roles in biological membranes and advanced oxidation for pollutant degradation. It is scientifically interesting and practically important to develop bio-mimetic radical-containing membranes that can perform simultaneous water filtration and organics removal. In this study, we have revealed the mechanisms of enduring stable radicals in an emerging radical polymer (RP) in initiating and facilitating the oxidative degradation of organic pollutants. Furthermore, we have successfully developed an interpenetrating polymer network membrane with RP and demonstrated its effectiveness in simultaneous organic pollutant degradation and wastewater filtration within the context of wastewater treatment. Our work offers insights into the mechanism of RP-triggered advanced oxidation process and opens a new avenue for energy-efficient solution for wastewater treatment.

Keywords: membrane, advanced oxidation process, radical polymer, wastewater treatment

Abstract

Integrating reactive radicals into membranes that resemble biological membranes has always been a pursuit for simultaneous organics degradation and water filtration. In this research, we discovered that a radical polymer (RP) that can directly trigger the oxidative degradation of sulfamethozaxole (SMX). Mechanistic studies by experiment and density functional theory simulations revealed that peroxyl radicals are the reactive species, and the radicals could be regenerated in the presence of O2. Furthermore, an interpenetrating RP network membrane consisting of polyvinyl alcohol and the RP was fabricated to demonstrate the simultaneous filtration of large molecules in the model wastewater stream and the degradation of ~ 85% of SMX with a steady permeation flux. This study offers valuable insights into the mechanism of RP-triggered advanced oxidation processes and provides an energy-efficient solution for the degradation of organic compounds and water filtration in wastewater treatment.

Honed over millions of years of evolution, biological membranes are highly efficient separation systems that are crucial to all living functions (1). Free radicals are found to be an essential component in bio-membranes (2). For example, free radicals can crosslink unsaturated low-viscosity fatty acid oils by chain-growth polymerization into more viscous liquids and even solids to increase membrane molecular organization and reduce oxygen diffusion (3–5). The significant role of radicals in biological membranes inspires an interest on the potential integration of radicals into synthetic membranes for separation applications.

In wastewater and potable water treatment, membranes have been increasingly applied over the past decades as an energy-efficient solution (6). Membrane bioreactor (MBR) and ultrafiltration (UF) are most commonly used, which remove the suspended solids, microorganisms, and large contaminant molecules. However, a variety of small organic molecules, such as pharmaceuticals, personal care products, pesticides, hormones, surfactants, flame retardants, and plasticizers, are released in wastewater streams and found in different water bodies, raising substantial environmental concerns (7, 8). These pollutants are biorefractory in nature and cannot be degraded effectively by biological processes. Meanwhile, due to their low molecular weight, the small organic pollutants are not well rejected by MBR or UF membranes.

In the 1980s, advanced oxidation process (AOP) was proposed to destruct the organic pollutants in drinking water treatment (9), and since then has been widely applied in various wastewater treatment (10–12). In a typical AOP process, hydroxyl or sulfate radicals are the reactive species that attack the organics through addition to the C=C bond, hydrogen abstraction from the C–C bond or removing electrons from the molecules, eventually leading to chemical degradation or even mineralization of the organic pollutants (12).

Due to the short lifetime of the reactive radicals in AOPs (e.g., 10−9 s for OH•), they are only in situ produced via a combination of oxidizing agents (H2O2, O3 or persulfate), irradiation (ultra-violet sound or ultrasound) and catalyst. Heating or changing of pH may also be involved. Typically, nanoscale transition metal oxides are used as the catalysts, which pose potential limitations on reaction conditions such as pH. Meanwhile, metals are usually costly and may be one additional source pollutants for the environment (13). In recent years, carbon materials made from biochar and hydrochar that contain persistent free radicals (PFR) (14, 15) have also been employed as the catalysts. The PFRs are stable in ambient environment for hours and even days. Nonetheless, the PFRs in carbon-based materials are prone to being depleted during oxidative processes, necessitating frequent high-temperature thermal treatment for regeneration.

Now, if the reactive radicals are integrated into membranes that resembles biological membranes, simultaneous organics degradation and water filtration can be achieved. However, the oxidative agents may damage polymeric membranes, light sources cannot be easily applied to membrane modules, and catalysts may leach out from the membranes during the rigorous use over the long term. As a result, studies on such membranes are limited (16–19).

Organic polymers bearing stable free radicals that can sustain over months and even years have emerged in recent years (20, 21) and have found use in many applications such as storage (22, 23), plastic magnetics (20, 21), and photothermal therapy (24, 25). It remains unexplored and yet scientifically interesting to understand the role of stable radicals in oxidation process. Furthermore, polymers typically can be readily processed into membranes.

Here, we investigated the potential and mechanism of radical polymers (RPs) for AOPs and demonstrated a RP-based membrane for oxidative filtration of model wastewater streams. RPs were found to directly trigger and facilitate the degradation of organic pollutant, represented by the antibiotic, sulfamethoxazole (SMX), in the presence of O2. Mechanistic studies by experiment and density functional theory (DFT) simulations revealed that peroxyl radicals are the reactive species. An interpenetrating RP network (IRPN) membrane, comprising polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) and the RP, was also fabricated, which demonstrated simultaneous filtration of large molecules in the model wastewater stream and degradation of ~85% of SMX. This study may offer valuable insights into the mechanism of RP-triggered AOPs and provide an energy-efficient solution for organic degradation and water filtration in wastewater treatment.

Results and Discussion

RPs for Oxidative Degradation of Organic Pollutants.

As illustrated in Fig. 1A, the RP was synthesized via a thermosetting process where 7,7,8,8-tetracyanoquinodimethane (TCNQ) self-polymerized in the presence of a Brønsted superacid, trifluoromethanesulfonic acid (TFMSA). A cross-linked π-conjugated polymeric membrane scaffold was formed, instead of insoluble powder or bulk morphology for other triazine-based polymers, which is attributed to the strong interaction between the basic triazine rings of as-synthesized polymer and the superacidic TFMSA (20, 26, 27). The polymer shows similar X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) and electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectra compared to previous studies (20) (SI Appendix, Fig. S1 and Fig. 1B), confirming the formation of a RP with carbon-centered radicals. Notably, the radical signal remains after exposure in the ambient environment for 1 y.

Fig. 1.

Synthesis of RP powders and degradation of organic pollutants by RPs: (A) An illustration of the synthesis of the RP and application of RP powders for organic pollutants degradation in water. The RP was synthesized by TCNQ self-polymerization at 165 °C, and the resulting polymer scaffold was then grounded into powders. (B) EPR spectrum of dry RPs (as-prepared and stored for 1 y). (C) Degradation of SMX by RP powders. (D) The degradation products monitored by UPLC-Q-TOF MS at 0, 5, and 120 min. (E) (Upper) The degradation of SMX with reused RPs, without and with O2 purging; (Lower) the N2 and O2 uptake of RPs at 35 °C. The concentration of SMX and RPs were 20 ppm and 500 ppm, respectively. “Blank” refers to the sample without RPs.

The RPs were then grounded into powders with the size of ~50 μm for the study of oxidative degradation of organic pollutants. SMX, one of the most prevalent antimicrobial contaminants detected in the nationwide groundwater in the United States (28), was used as the model organic molecule. As shown in Fig. 1C, the SMX concentration in the aqueous solution decreases to ~40% of its original value in the presence of RP powders for 2 h, in comparison to the constant concentration of the polymer-free blank sample. It suggests that RPs can initiate and facilitate the degradation of organic molecules. Interestingly, when the original SMX solution was purged with N2 for 120 min, the degradation rate is substantially reduced. On the contrary, O2 purging accelerates the degradation process, with a total of 71% of SMX degraded after 2 h. This result indicates that the dissolved O2 might participate in the reaction.

Notably, the AOP process here is directly induced by RPs. This is different from prior studies on polymers and carbon materials bearing persistent radicals (14, 15), where such materials merely play the roles of catalyst in the presence of oxidative substances. SI Appendix, Fig. S2A shows that under simulated sunlight, the polymer-triggered SMX degradation rate is slightly enhanced comparing to Fig. 1C. A similar phenomenon is observed for H2O2 (SI Appendix, Fig. S2B and Supporting Information Text I), suggesting that RPs can not only act as catalyst similar to traditional materials but also predominantly serve as the oxidants in the degradation of organic pollutants.

Then, we used UPLC-q-ToF-MS to analyze the degradation products. Fig. 1D shows that fragments with molecular weight of 478, 379, 285, 197, 156, 130, 114, and 98 Dalton were detected, while the portion of smaller fragments gradually increased as a function of time. These are likely the degradation intermediates of SMX, and a degradation pathway is thus proposed in SI Appendix, Fig. S4, similar to what has been reported (29). Such small intermediate molecules were reported to exhibit significantly less toxicity than SMX (29).

Interestingly, when the RP powders were filtered out of the solution, washed and directly reused in a second SMX solution, the degradation rate is largely reduced (Fig. 1E). On the other hand, by exposing the polymers to O2 and annealing at 60 °C prior to reuse, the efficiency is almost fully recovered (Fig. 1E and SI Appendix, Figs. S5 and S6 and Supporting Information Text II). Earlier findings reveal the participation of O2 in the reaction. O2 may come from three sources: First, dissolved oxygen in water. The dissolved oxygen concentration is ~9 mg L−1 at 25 °C. During the oxidation reaction, the oxygen diffuses freely in water and takes part in the reaction. The extent of involvement in both the initial and reuse tests are similar. Second, the absorbed O2 in the polymer. Gas sorption test results in Fig. 1E suggest that at 35 °C and 1 bar, the O2 uptake reaches 3.6 cm3 (STP) per cm3 of polymers, which corresponds to a concentration of 5.1 g L−1. This is much higher than dissolved oxygen concentration. Though the diffusivity of O2 within the polymer is limited, it is reasonable to postulate from the high O2 concentration and the low efficiency in polymer reuse that O2 in polymers contribute substantially to the oxidation reaction. The third source of O2 is purged gas, which provides new O2 supply and recovers the reaction rate.

Mechanistic Investigations Revealing Peroxyl Radicals as the Active Species.

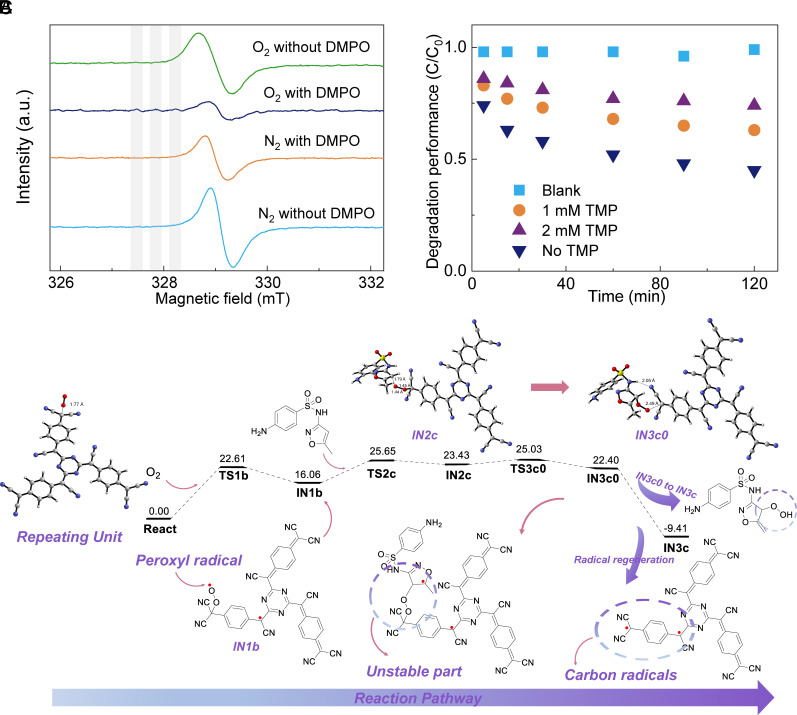

To probe the reactive radicals in the degradation of organic molecules, EPR spectra of the RP in water after different treatments were recorded (Fig. 2A). When no free radical probe was added, only one peak could be detected after the purging of either N2 or O2. This result gives little information on the reactive radical species, considering carbon-centered radical and peroxyl radical share the same shape and position in EPR spectrum (30). Then, a radical probe, 5,5-dimethyl-1-pyrroline N-oxide (DMPO), was added. Interestingly, for the O2-purged RP dispersion, additional fine peaks emerge (highlighted by the gray shades in the figure), which is attributed to the hyperfine interactions between DMPO and oxy radicals (31), while such fine peaks are absent in N2-purged RPs. This result again confirms the participation of O2 in the functional radical generation. The functional radical is most likely peroxyl radical, as it can be readily generated by the interaction of carbon-centered radicals with O2 (32). Upon the addition of SMX, more radical peaks are generated as illustrated in SI Appendix, Fig. S7, suggesting the generation of new radicals. Based on these results, we may propose that R reacts with O2 to form ROO, and the peroxyl radical is the key functional radical in the degradation of SMX.

Fig. 2.

The mechanistic studies of active radical species in the degradation of organic pollutants by RPs: (A) The EPR spectra of RPs with and without the presence of N2 or O2 using DMPO as the radical scavenger. The RP powders were dispersed in water and purged with N2 or O2 for 30 min before EPR test. The shaded areas highlight the specific peaks of DMPO/·OOH induced by hyperfine interaction. (B) The degradation of SMX by RPs with and without peroxyl radical trapper, TMP. “Blank” refers to the sample without RPs. The concentration of RPs in all other samples was 500 ppm. (C) The reaction pathway of RPs with SMX revealed by DFT simulation.

To further understand the role of peroxyl radicals, a peroxyl radical trapper, 2,4,6-trimethylphenol (TMP) was added (33), which significantly decreases the degradation efficiency of SMX in solution (Fig. 2B). This phenomenon supports our hypothesis that the original carbon-centered radical forms peroxyl radical by reacting with molecular oxygen, which then plays a main role in the degradation of organic molecules. Phenol, another organic molecule that shows high affinity to peroxyl radical, was also used (SI Appendix, Fig. S8). With the addition of phenol, the degradation rate of SMX is slowed down while the concentration of phenol remains unchanged. This is due to the inhibition effect (34) of phenolic group to peroxyl radical, which further supports the key role of peroxyl radicals.

Next, we performed DFT simulations to investigate the reaction mechanism between SMX and RPs. As shown in Fig. 2C, the RP has two potential reaction sites. One is at the center of the polymer repeating unit. The reaction pathway around this site is illustrated in SI Appendix, Fig. S9A, presenting an energy barrier from 1N2c to TS3c of 30.80 kcal mol−1 which is too high for spontaneous reactions. Another reaction site is at the edge of the polymer (SI Appendix, Fig. S9B). The corresponding reaction pathway starts from the reaction of RP with oxygen which generates peroxyl radicals, followed by the reaction between the radical intermediate IN1b and SMX, resulting in the formation of IN2c. Next, since the energy required to break the C-O bond (25.03 kcal mol−1) is lower than that required to break the O–O bond (31.84 kcal mol−1), the oxidation of SMX primarily occurs via the pathway (TS3c0) in Fig. 2C, rather than that in SI Appendix, Fig. S9B. IN3c0 serves as an intermediate in transition state during this reaction, which is unstable and spontaneously transforms into IN3c. The energy barrier from 1N2c to TS3c0 is 1.60 kcal mol−1, suggesting the reaction here can occur spontaneously likely due to the lower steric hinderance compared to the first site. During this process, the intermediate splits into two components: a RP with a carbon-centered radical and degraded SMX. The RP with a carbon-centered radical can further react with O2, initiating another reaction cycle. The results confirm the crucial roles of peroxyl radicals and O2 in the degradation reaction. In addition, SMX is also part of the cycle to allow regeneration of radicals in the RP.

RP Interpenetrating Membrane for Oxidative Filtration of Water Streams Containing Organic Pollutants.

Having demonstrated the ability of RPs for oxidative degradation of organic pollutants, we then developed radical-containing membranes for the simultaneous water filtration and pollutant degradation (Fig. 3A). The bare RP scaffold was first evaluated. The membrane looks dense due to strong interchain interactions during freeze drying prior to SEM imaging (Fig. 3B). However, its internal structure, if maintained in the wet state, is in fact porous, as is evidenced by the initial flux of 66.2 L m−2 h−1 at the applied pressure of 1 bar (SI Appendix, Fig. S10). The SMX is degraded by 76% during this filtration process. Nonetheless, both the permeation flux and degradation performance decrease significantly during the test, with flux decreased to 17.2 L m−2 h−1 and degradation efficiency dropped to 0.46 after 2 h (SI Appendix, Fig. S10). A possible explanation is that, under pressure, the strong inter-chain interactions of the RP lead to pore collapse, resulting in lower flux and less area exposed to SMX.

Fig. 3.

Fabrication and characterization of RP and PVA-IRPN membranes: (A) A schematic illustration of PVA-IRPN membrane and its application for oxidative filtration of water streams containing organic pollutant; (B) SEM images of the membrane surfaces; (C) FTIR spectra; (D) XPS spectra; and (E) (Upper) water contact angle and (Lower) maximum tensile strength.

To enhance the membrane stability, we fabricated an interpenetrating membrane consisting of PVA and RP by immersing the polymer scaffold into the aqueous PVA solution, which was then crosslinked by glutaraldehyde, forming a PVA—interpenetrating RP network (IRPN). The presence of PVA is confirmed by FTIR and XPS (Fig. 3 C and D). The new peaks at ~3,450 cm−1 and 1,720 cm−1 correspond to the -OH stretching in the PVA chains and C=O groups of glutaraldehyde. The peak signal at 1,090 cm−1 is substantially increased, which is assigned to the C-O stretching of PVA. In addition, the N1s XPS spectrum of PVA-IRPN membrane shows a new peak at 402.3 eV, representative of the protonation of pyrrolic N (35) induced by PVA and RP. The O1s XPS spectrum (SI Appendix, Fig. S11) of PVA-IRPN displays characteristic peaks for both PVA and RP at 533.3 eV and 531.6 eV, respectively, confirming the successful interpenetration of PVA into RP scaffold. The SEM image in Fig. 3B shows a porous structure with the pore size below 1 μm, confirming the ability of hydrophilic PVA chains in maintaining the pores even during freeze-drying. This is contradictory to intuitive knowledge that rigid polymers are more mechanically stable than soft hydrophilic polymers. It supports our earlier speculation that the strong inter-chain interaction of the RP causes pore collapse during freeze drying and the presence of PVA network helps reduce the interactions. Interestingly, the interpenetration of PVA into RPs improves the mechanical strength of the membrane. As shown in Fig. 3E, the maximum tensile strength is drastically increased from 1.3 MPa to 28.3 MPa. Furthermore, the water contact angle decreases from 105.2° to 71.1°, which is favorable for water transport.

Then, the membrane was loaded into a dead-end cell which was connected to compressed air to maintain the transmembrane pressure. Fig. 4A shows that at 0.5 bar, the water flux is 31.8 L m−2 h−1 and ~82% SMX from the 20 ppm feed solution is degraded. With the gradual elevation of pressure to 4.0 bar, the water permeation across the membranes becomes faster. As a result, the contact time of SMX with RPs is shortened, leading to decreasing degradation rate.

Fig. 4.

The performance of PVA-IRPN membrane for oxidative filtration of water streams containing organic pollutants. (A) The flux and degradation efficiency under different applied pressure; (B) The flux and degradation efficiency versus time at the SMX concentrations of 10, 20, and 40 ppm, and the applied pressure of 0.5 bar. (C) The degradation efficiency. The gas was purged into the beaker containing the feed water for 30 min prior to being transferred to a dead-end cell for testing. The applied pressure was 0.5 bar and SMX concentration was 10 and 20 ppm; (D) demonstration of oxidation-filtration process using simulated wastewater containing 2,000 ppm humic acid and 20 ppm SMX; the applied pressure was 1.0 bar.

Fig. 4B shows that higher degradation efficiency is achieved when SMX concentration is reduced from 40 to 20 ppm. Further lowering the concentration to 10 ppm leads to only marginal gain, possibly due to the limitation of contact with the polymer. It is also observed that the degradation efficiency remains almost constant throughout the 120-min tests, proving the stability of the membrane. In addition, similar to the studies on powders, replacing air by nitrogen drastically decreases the degradation efficiency to <10% (Fig. 4C), further confirming the importance of O2 in the reaction.

Last, we demonstrated the concept of oxidative filtration of wastewater streams by employing a model feed solution containing 2,000 ppm humic acid and 20 ppm SMX. It is seen from Fig. 4D that the flux is maintained at ~70.1 L m−2 h−1 throughout the test for 2 h, with a humic acid rejection rate exceeding 98.5%, suggesting the potential use of the membrane as an UF membrane with mild fouling. The SMX degradation rate remains high, suggesting that the oxidative reaction preferentially occurs on small organic pollutants and is not significantly affected by the presence of humic acid.

In summary, we have discovered a polymer with long-lasting stable radicals that can directly initiate and facilitate the oxidative degradation of organic pollutants. Mechanistic studies revealed the peroxyl radicals as the reactive radical species and the interplay among polymer, O2, and SMX that is critical to the organics degradation and radical regeneration. Furthermore, we have fabricated a PVA-IRPN membrane and demonstrated its application for simultaneous degradation of organic pollutants and filtration for wastewater treatment.

Materials and Methods

Preparation of RP Scaffolds and Powders.

RP was synthesized based on the self-polymerization of TCNQ monomer following the method described previously (20). Briefly, the synthesis was conducted in a glove bag filled with nitrogen gas. Then, 0.10 to 0.20 g of TCNQ (TCI, >98%) was put into a small vial, following by the addition of 1.0 to 2.0 mL TFMSA (TCI). The ratio of TFMSA over TCNQ varied from 20: 1 to 4: 1 to prepare different RP scaffolds. The solution was then stirred for 1 min, before it was transferred into a glass petri dish and placed in a 100 mL autoclave. After that, the autoclave was heated at 165 °C for 12 h and cooled down to room temperature. The product was removed from the autoclave and immersed in n-methyl-2-pyrrolidone (NMP) solution for 3 d. The synthesized polymer scaffold was transferred from NMP solution and immersed in ultrapure water for another 2 d to remove the residuals. The RP scaffold was further grounded into ~50 μm powder after drying and stored in glass vials in darkness.

Preparation of Interpenetrating RP Network Membranes.

To fabricate the RP-poly (vinyl alcohol) (PVA) interpenetrating RP network (IRPN) membrane, the as-prepared RP scaffold was immersed in PVA solution comprising 5 wt% PVA and 1% glutaraldehyde overnight, then dried at 120 °C for 2 h, and transferred to DI water.

Degradation of Model Organic Molecules Using RP Powders and Membranes.

SMX was used as a model organic molecule in the study of RPs for AOP. Batch experiment was conducted under the ambient conditions employing RP powders, and for better understanding, simulated sunlight or H2O2 was applied in some batches. RP powders were added at the concentrations of 100 to 500 ppm into the SMX solution with the initial concentration of 10 to 40 ppm. The change of concentration and compositions in the solution along with time was monitored based on the method discussed in the follow-up session.

For the experiment involving sunlight, a 300-W Xenon light system (AULIGHT Xenon Lamp) with an AREF filter (Full reflective 200 to 2,500 nm) was used. Different filters (UVIRCut400, Band Pass 400 to 780 nm, and VisREF, Reflect Visible Light 350 to 780 nm) were used to investigate the influence of light wavelengths on the degradation of SMX. For SMX degradation with RP and H2O2, 10 mM H2O2 was added into the solution immediately after RP was added.

To test the reusability of radicals, the RP was collected and washed 3 times with ultrapure water. Then, the powders were put in a vial and exposed to O2 overnight by connecting the vial to an O2 carrier, and then dried at 60 °C overnight before reuse. In a separate approach, powders were annealing at 165 °C for 5 h prior to reuse.

The oxidation-filtration test was tested using the RP interpenetrated membranes with a dead-end permeation cell at the transmembrane pressure of 0.5 to 4.0 bar. A 200 mL feed solution containing SMX at a concentration of 10 to 40 ppm was added to the permeation cell and stirred at 300 rpm. The permeate was collected at certain time intervals.

Permeation flux was calculated using following equation:

| [1] |

where (L) is the permeate volume collected over the time interval (h) across an active membrane surface area of (m2).

The degradation efficiency was calculated based on the concentration in the feed and permeate solutions using the following equation:

| [2] |

where and are the SMX concentrations in the permeate and feed solution, respectively.

To demonstrate the simultaneous wastewater filtration and degradation, a model solution containing 2,000 ppm humic acid and 20 ppm SMX was applied as the feed, and the pressure was 1.0 bar. The rejection of humic acid was calculated based on the following equation: where Cp and Cf refer to the concentration of humic acid in the permeate and feed, respectively, where was determined based on the total organic carbon concentration by TOC (Shimadzu TOC-V CSH analyzer).

Characterization and Analytical Methods.

The concentration of SMX was measured by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC, Agilent Series 1100) with ZORBAX Original C18 reverse-phase column (4.6 × 250 mm, 5 µm). The mobile phase was 60% methanol and 40% water with 0.1% acetic acid, at a flow rate of 1 mL min−1 and an injection volume of 10 µL. Intermediates of SMX degradation were detected by ultra-performance liquid chromatography to quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry (UPLC-Q-TOF-MS) in negative ionization mode with 20 min elution time. EPR (JEOL FA200 ESR) was tested to identify the functional radials. During the EPR test, DMPO was used as the free-radical probe (SI Appendix, Supporting Information Text III).

The surface elementary compositions and chemical structure of the RP and interpenetrating network membrane were characterized by XPS with a surface analysis spectrometer (AXIS Ultra DLD, Kratos, UK) using monochromatic Al K-α (1486.71 eV) as the X-ray source and Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (VERTEX70, Bruker, Germany). The surface morphology of membranes was characterized using field emission scanning electron microscopy (JSM-7600F, JEOL, Japan). The membrane was immersed in a 6M guanidine hydrochloride solution overnight to preserve the pore structure. After removing the surface solution, it was transferred to liquid nitrogen and subjected to freeze drying.

DFT Calculation.

The computational calculations were performed using Gaussian 09 software 8. The three-dimensional molecular structures were visualized using CYLview 9. The RP was represented by its smallest repeating unit.

All geometrical structures were optimized using the B3LYP (36) method and 6-31G(d) (37) basis set. Frequency analyses were conducted at the same theoretical level, where transition states exhibited only one negative frequency and the rest were without negative values. Intrinsic reaction coordinate (38) computations were performed on each transition state structure to ensure proper connection between the reactant and product. Solvation effects were considered by calculating the single-point energy using the M062x/6-311++G(d, p) method (39) and applying the SMD (40) solvation model to each optimized structure.

Supplementary Material

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the financial support by the Ministry of Education of Singapore via the Tier-1 project A-8000192-01-00.

Author contributions

F.L. and S.Z. designed research; F.L., Y.M., R.Z.N.C., and J.W. performed research; F.L. contributed new reagents/analytic tools; F.L., W.L., D.H., M.Y., and S.Z. analyzed data; and F.L., W.L., and S.Z. wrote the paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interest.

Footnotes

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Contributor Information

Wei Liu, Email: 101012931@seu.edu.cn.

Sui Zhang, Email: chezhangsui@nus.edu.sg.

Data, Materials, and Software Availability

All study data are included in the article and/or SI Appendix.

Supporting Information

References

- 1.Park H. B., Kamcev J., Robeson L. M., Elimelech M., Freeman B. D., Maximizing the right stuff: The trade-off between membrane permeability and selectivity. Science 356, eaab0530 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dröge W., Free radicals in the physiological control of cell function. Physiol. Rev. 82, 47–95 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Richard C. P., Free-radicals and advanced chemistries involved in cell membrane organization influence oxygen diffusion and pathology treatment. AIMS Biophys. 4, 240–283 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zeng M., Heine N., Wilson K. R., Evidence that Criegee intermediates drive autoxidation in unsaturated lipids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 117, 4486–4490 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gaibelet G., et al. , Fluorescent probes for detecting cholesterol-rich ordered membrane microdomains: Entangled relationships between structural analogies in the membrane and functional homologies in the cell. AIMS Biophys. 4, 121–151 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van der Bruggen B., Vandecasteele C., Van Gestel T., Doyen W., Leysen R., A review of pressure-driven membrane processes in wastewater treatment and drinking water production. Environ. Prog. 22, 46–56 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 7.García J., et al. , A review of emerging organic contaminants (EOCs), antibiotic resistant bacteria (ARB), and antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) in the environment: Increasing removal with wetlands and reducing environmental impacts. Bioresour. Technol. 307, 123228 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lapworth D., Baran N., Stuart M., Ward R., Emerging organic contaminants in groundwater: A review of sources, fate and occurrence. Environ. Pollut. 163, 287–303 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Glaze W. H., Kang J.-W., Chapin D. H., The chemistry of water treatment processes involving ozone, hydrogen peroxide and ultraviolet radiation. Ozone: Sci. Eng. 9, 335–352 (1987). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pereira V. J., Linden K. G., Weinberg H. S., Evaluation of UV irradiation for photolytic and oxidative degradation of pharmaceutical compounds in water. Water Res. 41, 4413–4423 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Magureanu M., Mandache N. B., Parvulescu V. I., Degradation of pharmaceutical compounds in water by non-thermal plasma treatment. Water Res. 81, 124–136 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deng Y., Zhao R., Advanced oxidation processes (AOPs) in wastewater treatment. Curr. Pollut. Rep. 1, 167–176 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Glaze W. H., Drinking-water treatment with ozone. Environ. Sci. Technol. 21, 224–230 (1987). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Qin Y., et al. , Persistent free radicals in carbon-based materials on transformation of refractory organic contaminants (ROCs) in water: A critical review. Water Res. 137, 130–143 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fang G., et al. , Key role of persistent free radicals in hydrogen peroxide activation by biochar: Implications to organic contaminant degradation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 48, 1902–1910 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bu Y., et al. , Peroxydisulfate activation and singlet oxygen generation by oxygen vacancy for degradation of contaminants. Environ. Sci. Technol. 55, 2110–2120 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xu Q., et al. , Synergistic oxidation-filtration process of electroactive peroxydisulfate with a cathodic composite CNT-PPy/PVDF ultrafiltration membrane. Water Res. 210, 117971 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yu C., et al. , Marriage of membrane filtration and sulfate radical-advanced oxidation processes (SR-AOPs) for water purification: Current developments, challenges and prospects. Chem. Eng. J. 433, 133802 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li N., et al. , Catalytic membrane-based oxidation-filtration systems for organic wastewater purification: A review. J. Hazard. Mater. 414, 125478 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mahmood J., et al. , Organic ferromagnetism: Trapping spins in the glassy state of an organic network structure. Chem 4, 2357–2369 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Phan H., et al. , Room-temperature magnets based on 1, 3, 5-triazine-linked porous organic radical frameworks. Chem 5, 1223–1234 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xu F., et al. , Radical covalent organic frameworks: A general strategy to immobilize open-accessible polyradicals for high-performance capacitive energy storage. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 54, 6814–6818 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Janoschka T., Hager M. D., Schubert U. S., Powering up the future: Radical polymers for battery applications. Adv. Mater. 24, 6397–6409 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mi Z., et al. , Stable radical cation-containing covalent organic frameworks exhibiting remarkable structure-enhanced photothermal conversion. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 14433–14442 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang Y., et al. , Supramolecular radical anions triggered by bacteria in situ for selective photothermal therapy. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 56, 16239–16242 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhou Z., et al. , Dissolution and liquid crystals phase of 2D polymeric carbon nitride. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 2179–2182 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhu X., et al. , A superacid-catalyzed synthesis of porous membranes based on triazine frameworks for CO2 separation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 10478–10484 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barnes K. K., et al. , A national reconnaissance of pharmaceuticals and other organic wastewater contaminants in the United States—I) Groundwater. Sci. Total Environ. 402, 192–200 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang Y., et al. , Degradation of sulfamethoxazole by UV, UV/H2O2 and UV/persulfate (PDS): Formation of oxidation products and effect of bicarbonate. Water Res. 118, 196–207 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chamulitrat W., Takahashi N., Mason R., Peroxyl, alkoxyl, and carbon-centered radical formation from organic hydroperoxides by chloroperoxidase. J. Biol. Chem. 264, 7889–7899 (1989). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sevilla M. D., Yan M., Becker D., Thiol peroxyl radical formation from the reaction of cysteine thiyl radical with molecular oxygen: An ESR investigation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 155, 405–410 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smith L. M., Aitken H. M., Coote M. L., The fate of the peroxyl radical in autoxidation: How does polymer degradation really occur? Acc. Chem. Res. 51, 2006–2013 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Aguer J.-P., Richard C., Humic substances mediated phototransformation of 2, 4, 6-trimethylphenol: A catalytic reaction. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 4, 451–453 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lucarini M., Pedulli G. F., Valgimigli L., Amorati R., Minisci F., Thermochemical and kinetic studies of a bisphenol antioxidant. J. Org. Chem. 66, 5456–5462 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Matanovic I., et al. , Core level shifts of hydrogenated pyridinic and pyrrolic nitrogen in the nitrogen-containing graphene-based electrocatalysts: In-plane vs edge defects. J. Phys. Chem. C 120, 29225–29232 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee C., Yang W., Parr R. G., Development of the Colle-Salvetti correlation-energy formula into a functional of the electron density. Phys. Rev. B 37, 785 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Francl M. M., et al. , Self-consistent molecular orbital methods. XXIII. A polarization-type basis set for second-row elements. J. Chem. Phys. 77, 3654–3665 (1982). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fukui K., The path of chemical reactions-the IRC approach. Acc. Chem. Res. 14, 363–368 (1981). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhao Y., Truhlar D. G., Density functionals with broad applicability in chemistry. Acc. Chem. Res. 41, 157–167 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Marenich A. V., Cramer C. J., Truhlar D. G., Universal solvation model based on solute electron density and on a continuum model of the solvent defined by the bulk dielectric constant and atomic surface tensions. J. Phys. Chem. B 113, 6378–6396 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Data Availability Statement

All study data are included in the article and/or SI Appendix.