Abstract

Ferredoxins comprise a large family of iron-sulfur (Fe/S) proteins that shuttle electrons in diverse biological processes. Human mitochondria contain two isoforms of [2Fe-2S] ferredoxins, FDX1 (aka adrenodoxin) and FDX2, with known functions in cytochrome P450-dependent steroid transformations and Fe/S protein biogenesis. Here, we show that only FDX2, but not FDX1, is involved in Fe/S protein maturation. Vice versa, FDX1 is specific not only for steroidogenesis, but also for heme a and lipoyl cofactor biosyntheses. In the latter pathway, FDX1 provides electrons to kickstart the radical chain reaction catalyzed by lipoyl synthase. We also identified lipoylation as a target of the toxic anti-tumor copper ionophore elesclomol. Finally, the striking target specificity of each ferredoxin was assigned to small conserved sequence motifs. Swapping these motifs changed the target specificity of these electron donors. Together, our findings identify new biochemical tasks of mitochondrial ferredoxins and provide structural insights into their striking functional specificity.

Keywords: Iron-sulfur proteins, lipoyl synthase, biogenesis, heme, coenzyme Q, mitochondria, cellular respiration, elesclomol

Introduction

Ferredoxins (FDXs) comprise a large family of redox proteins found in all kingdoms of life1,2. Their iron-sulfur (Fe/S) cofactors allow electron transfer to numerous targets in diverse biological pathways. FDXs from pathogens may serve as drug targets3,4. Mitochondria harbor the [2Fe-2S] cluster-containing FDXs that are evolutionarily derived from bacteria, and receive their electrons from NADPH via ferredoxin reductase (FDXR)1. The long-known mammalian mitochondrial FDX1 (aka adrenodoxin) functions in the metabolism of steroid hormones, bile acids, and vitamins A and D transferring electrons to all seven class I mitochondrial cytochrome P450 enzymes5. Mammals, including humans, possess the additional [2Fe-2S] FDX2 which, however, cannot take over the function of FDX1 in cortisol formation6. Instead, FDX2 and its fungal counterparts including S. cerevisiae Yah1 are central components of the core iron-sulfur cluster assembly (ISC) machinery, and hence are present in virtually all mitochondria or in mitochondria-related, ISC-containing mitosomes and hydrogenosomes4,6–11. FDX2 is required twice in mitochondrial Fe/S protein maturation. Initially, it interacts with the cysteine desulfurase complex NFS1-ISD11-ACP112–14 and reduces a persulfide (-SSH) bound to the scaffold protein ISCU2 to sulfide, thereby inducing de novo [2Fe-2S] cluster synthesis9,15–17. Later in mitochondrial [4Fe-4S] cluster assembly, FDX2 facilitates reductive fusion of two [2Fe-2S] to a [4Fe-4S] cluster on the ISCA proteins18. The importance of human FDX2 and FDXR is reflected by severe genetic diseases including mitochondrial myopathy and sensory neuropathies19–22. Moreover, FDXR is a p53-dependent tumor suppressor, and its deficiency leads to tumor formation and liver disease in a mouse model23.

Beyond steroidogenesis and Fe/S protein biogenesis, mitochondrial FDXs were reported to be involved in other metabolic reactions. For instance, yeast mitochondrial Yah1, together with its reductase Arh1, provides electrons to the hydroxylase Cox15, thereby yielding heme a/a3 of cytochrome c oxidase (COX)24–26. Since FDX2 knockdown in human cells is associated with a partial COX defect, the protein was suggested to perform a similar function as Yah16. Additionally, Yah1-Arh1 are required for coenzyme Q (ubiquinone or yeast CoQ6) biosynthesis, supposedly to reduce the Coq6 protein that catalyzes C5-hydroxylation of a CoQ6 intermediate27,28. Neither human FDX1 nor FDX2 can replace Yah1 in yeast CoQ6 synthesis, leaving open whether these electron donors might support CoQ10 biosynthesis in humans. Conflicting results have been reported for the involvement of human FDX1 in cellular Fe/S protein biogenesis. Earlier studies, using in vivo complementation in yeast and RNA interference (RNAi) experiments in human cell culture, identified FDX2 as the sole Fe/S protein biogenesis-related FDX6. Accordingly, FDX2 but not FDX1 was crucial for in vitro reconstitution of both [2Fe-2S] and [4Fe-4S] cluster formation9,16,18,29. In principle, the specialized functions of human FDX1 and FDX2 fit their strikingly different tissue distribution identified by immunostaining6 (Suppl. Fig. 1a; see legend for details). However, systematic transcript analyses indicate significant expression of FDX1 mRNA in a variety of tissues despite undetectable protein levels, raising the question of a broader function of FDX1 (Suppl. Fig. 1b). Accordingly, two reports proposed FDX1 to function also in Fe/S protein biogenesis, based on RNAi depletion experiments and in vitro [2Fe-2S] cluster synthesis on ISCU2 using FDXs chemically reduced by dithionite (DT)8,30. It remained unexplained, however, why the two FDXs would not functionally complement each other in vivo in Fe/S protein biogenesis.

Here, we aimed to clarify these important issues and identified so far unknown functions of the human FDXs in mitochondrial metabolism, most prominently the essential role of FDX1 to kickstart the radical chain reaction of lipoyl synthase (LIAS). Knowledge of the functional capacity of the two FDXs is crucial for understanding their impact on both mitochondrial metabolism and mitochondria-cytoplasm interaction, particularly in (tumorigenic) cells that shutdown their dependence on mitochondrial respiration31–33. We also report a striking target specificity of the two FDXs, and hence examined the structural basis of target recognition by site-directed mutagenesis, leading to the identification of small structural segments that functionally discriminate the two FDXs. Our work defining the functional spectrum of the human FDXs may have possible implications for better understanding disease phenotypes and for biotechnological applications of these unique electron donors34.

Results

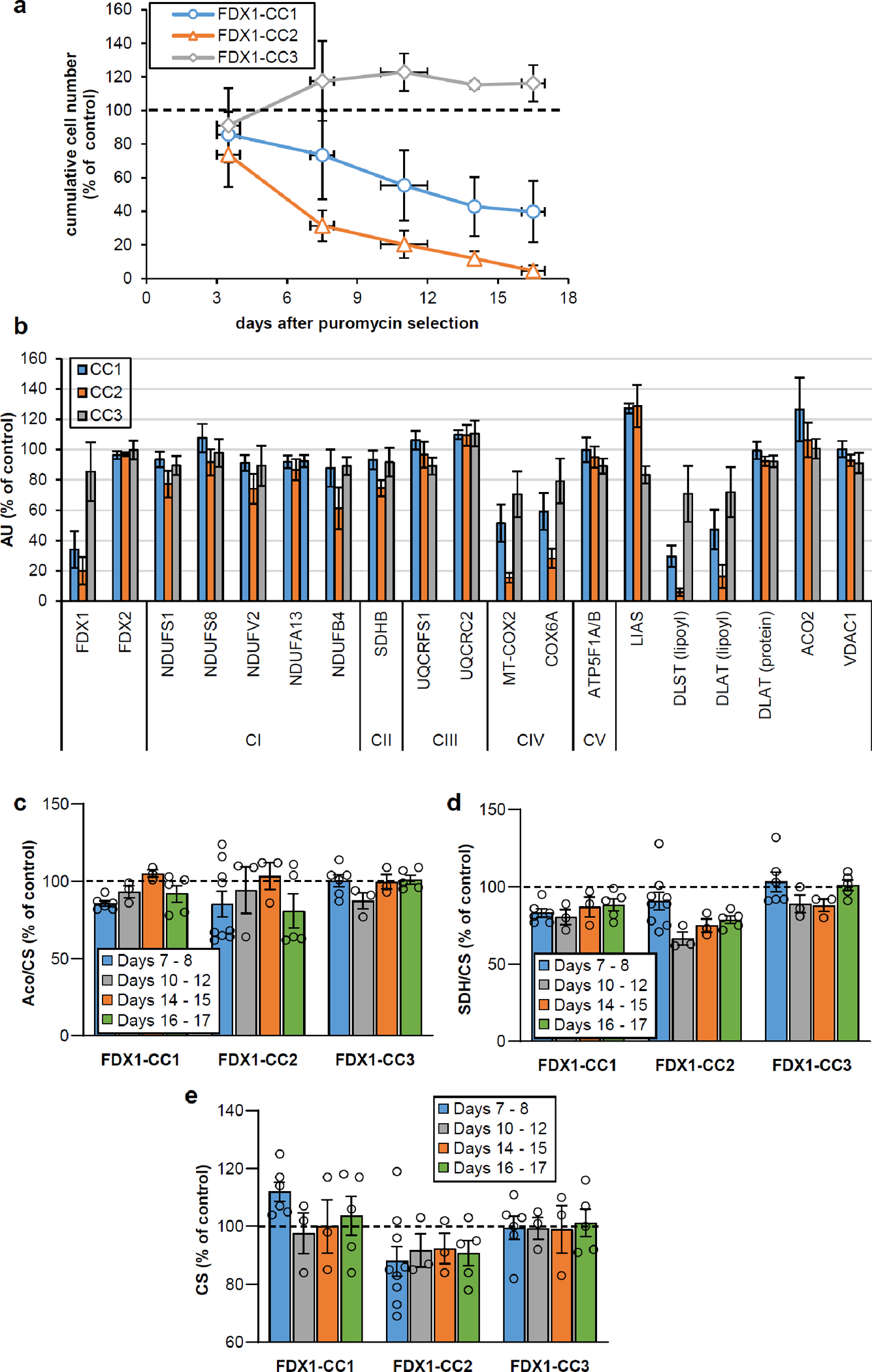

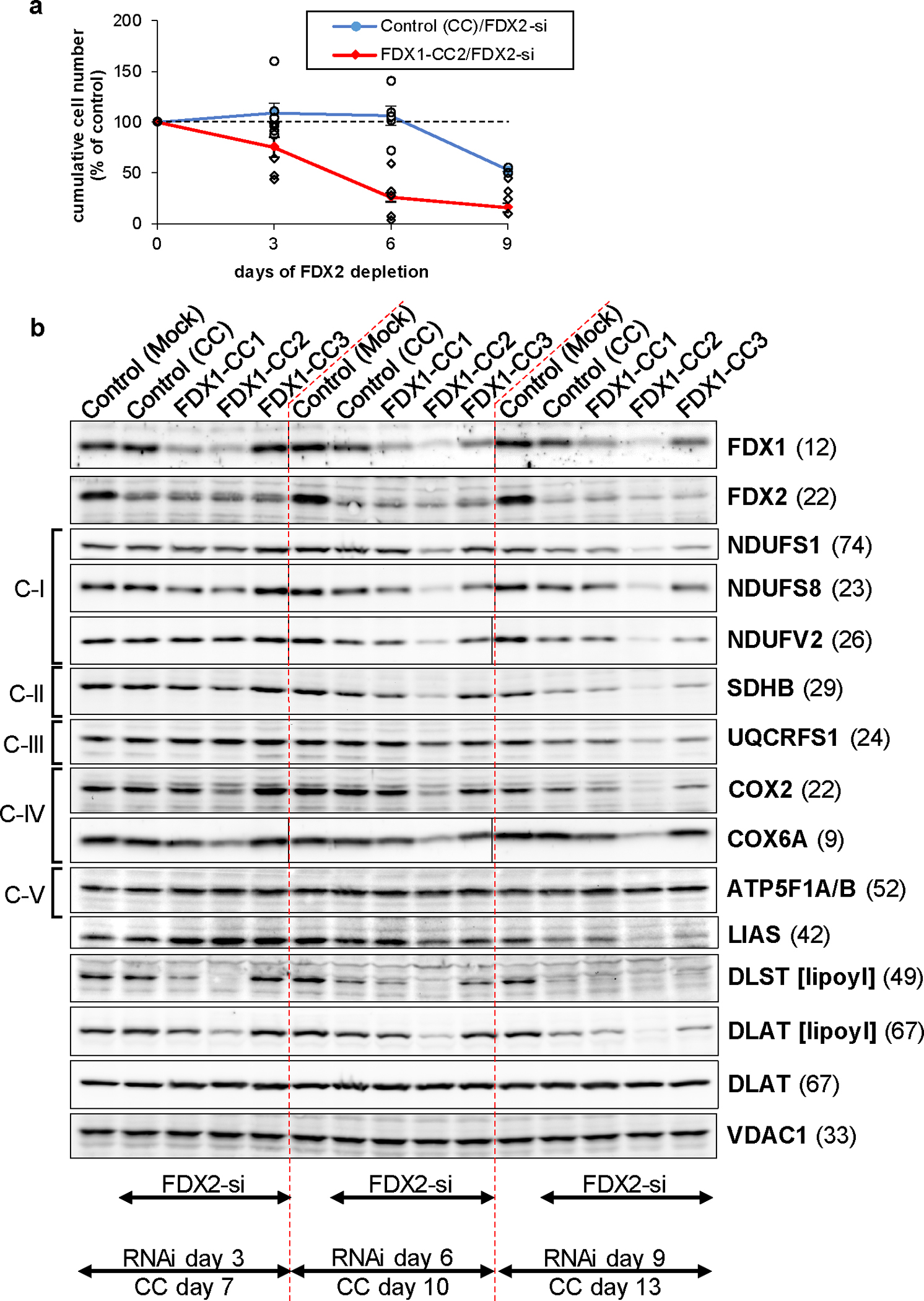

FDX2 but not FDX1 is required for cellular Fe/S protein biogenesis

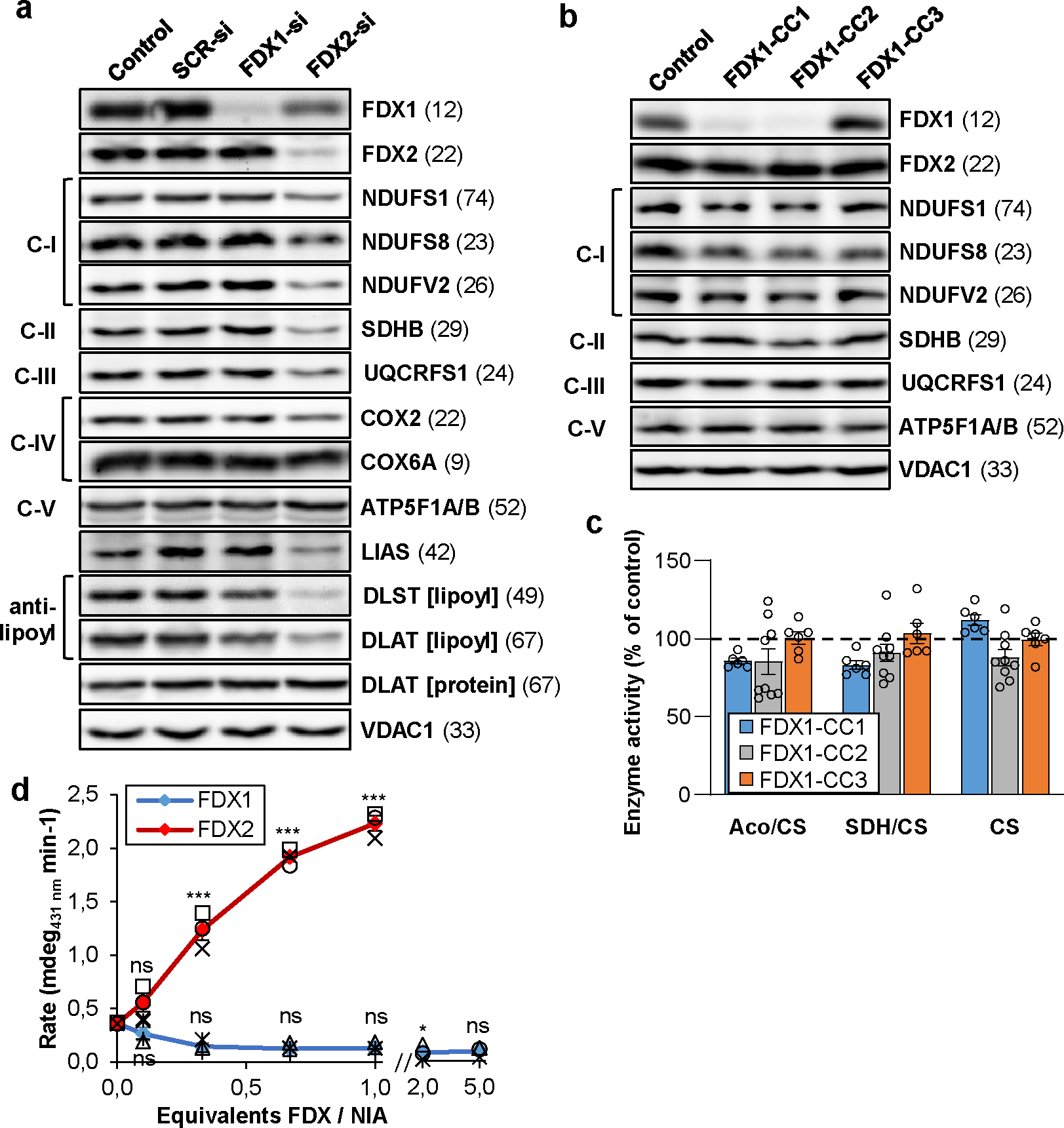

In vivo and in vitro studies have provided conflicting results on the function of human FDX1 in Fe/S protein biogenesis, while the involvement of FDX2 in this process is undisputed6,8,9,30. Re-evaluation of these experiments confirmed that substantial depletion of FDX1 by RNAi did not induce any significant growth defect or reduction in the levels of various mitochondrial and cytosolic-nuclear Fe/S proteins, in contrast to depletion of FDX2, which is essential for the biogenesis of cellular Fe/S proteins including FDX1 (Fig. 1a; Suppl. Fig. 2a,b)6. To exclude that our RNAi knockdown of FDX1 was too weak to elicit a detectable phenotype, we knocked out FDX1 (or FDX2 as a control) by CRISPR-Cas9 technology. Application of three different FDX2-directed guide RNAs (gRNAs) did not yield viable FDX2-depleted cells after puromycin selection, consistent with the indispensable function of FDX2 in Fe/S protein assembly6,8. Two of three FDX1-directed gRNAs (CC1 and CC2; Suppl. Table 1) efficiently depleted FDX1, and, in contrast to the RNAi findings, profoundly decreased cell growth over time, while gRNA CC3 was ineffective (Fig. 1b; Extended data Fig. 1a,b). The results suggested a critical in vivo role of FDX1 disclosed only upon strong depletion. CC1- or CC2-mediated FDX1 knockout hardly affected the levels of the mitochondrial Fe/S-cluster-containing respiratory chain subunits NDUFS1, NDUFS8, NDUFV2, SDHB, and UQCRFS1, in contrast to the RNAi-mediated FDX2 knockdown (Fig. 1a,b; Extended data Fig. 1b; Suppl. Fig. 2b). Consistently, the enzyme activities of key mitochondrial Fe/S proteins, i.e. aconitase and succinate dehydrogenase (SDH), were not altered upon FDX1 knockout (Fig. 1c; Extended data Fig. 1c–e), unlike upon FDX2 RNAi depletion6,8. Together, these findings strongly argue against a critical in vivo role of FDX1 in cellular Fe/S protein biogenesis.

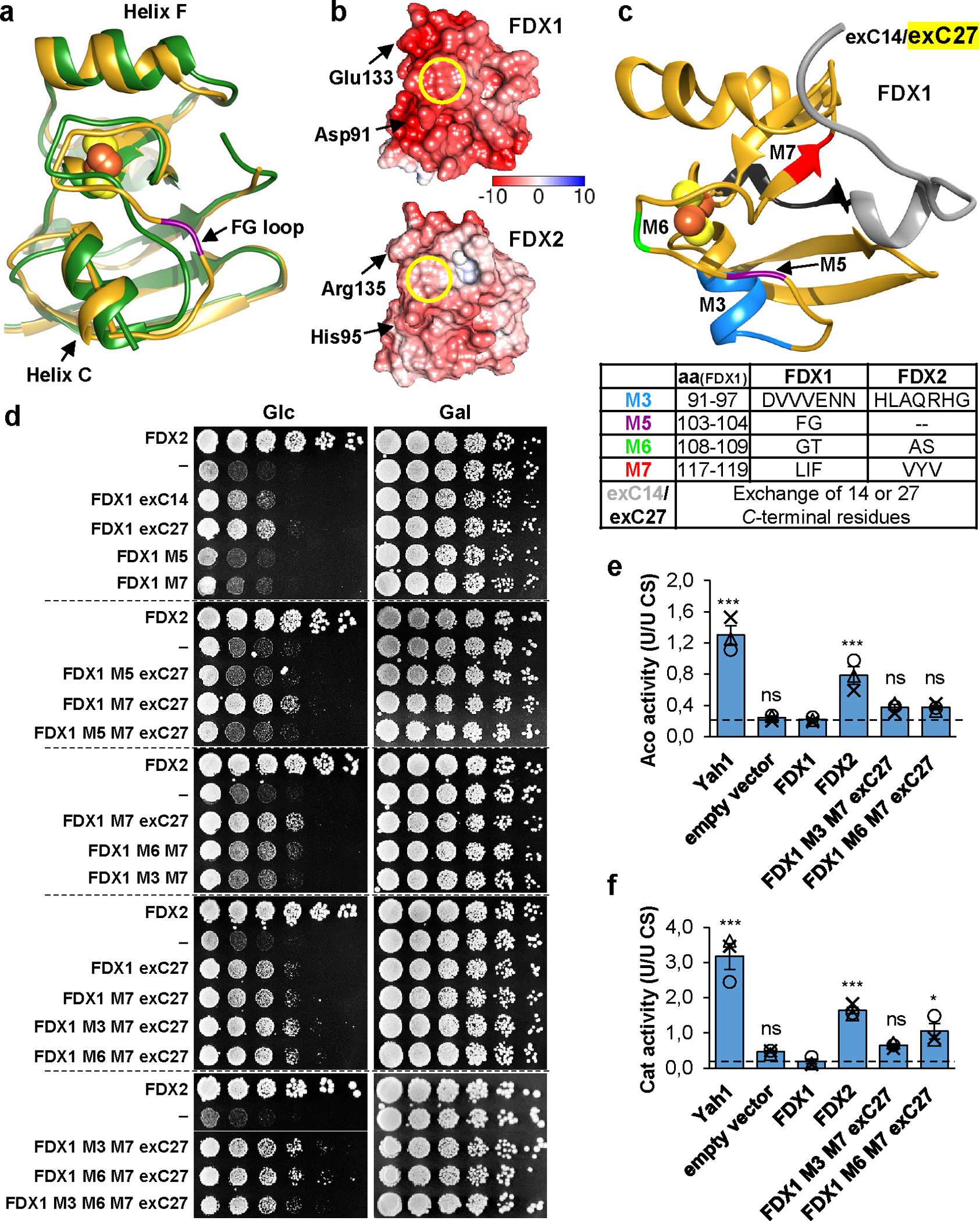

Fig. 1. FDX1 is not involved in mitochondrial Fe/S protein assembly.

a HEK293 cells were transfected without (control) or with scrambled (SCR) non-targeting siRNA, or with pools of FDX1- or FDX2-directed siRNAs (si) at a three-day interval6. Cells were harvested 9 days after the first transfection. Cell extracts were analyzed by immunostaining for the indicated mitochondrial proteins. Observed molecular masses (kDa) for proteins are given in parentheses. C-I, C-II, C-III, respiratory complexes I, II, and III; C-V, F1Fo ATP synthase. b HEK293 cells were chemically transfected with the empty plasmid PX459 (control) or with plasmids containing three different FDX1-directed gRNAs (CC1 to CC3). Transfected cells were selected by puromycin for 3 days. Samples harvested 8 days after antibiotic removal were subjected to immunostaining of the indicated mitochondrial proteins. For quantitation see Extended data Fig. 1b. c Total aconitase (Aco) and succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) enzyme activities were determined in extracts from cells described in (b). Results were expressed as a ratio to citrate synthase (CS) activity, and presented relative to the respective values of control cells (set to 100%, dashed line; n ≥ 6). d Enzymatic reconstitution of [2Fe-2S] cluster formation on ISCU2 in the presence of indicated amounts of FDX1 or FDX2 was measured by CD spectroscopy. Initial rates were determined by linear fitting of the kinetic traces (Extended data Fig. 2; n = 3; one-way ANOVA for control without versus with FDX reactions, *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001). Error bars indicate the SEM. Representative blots are shown.

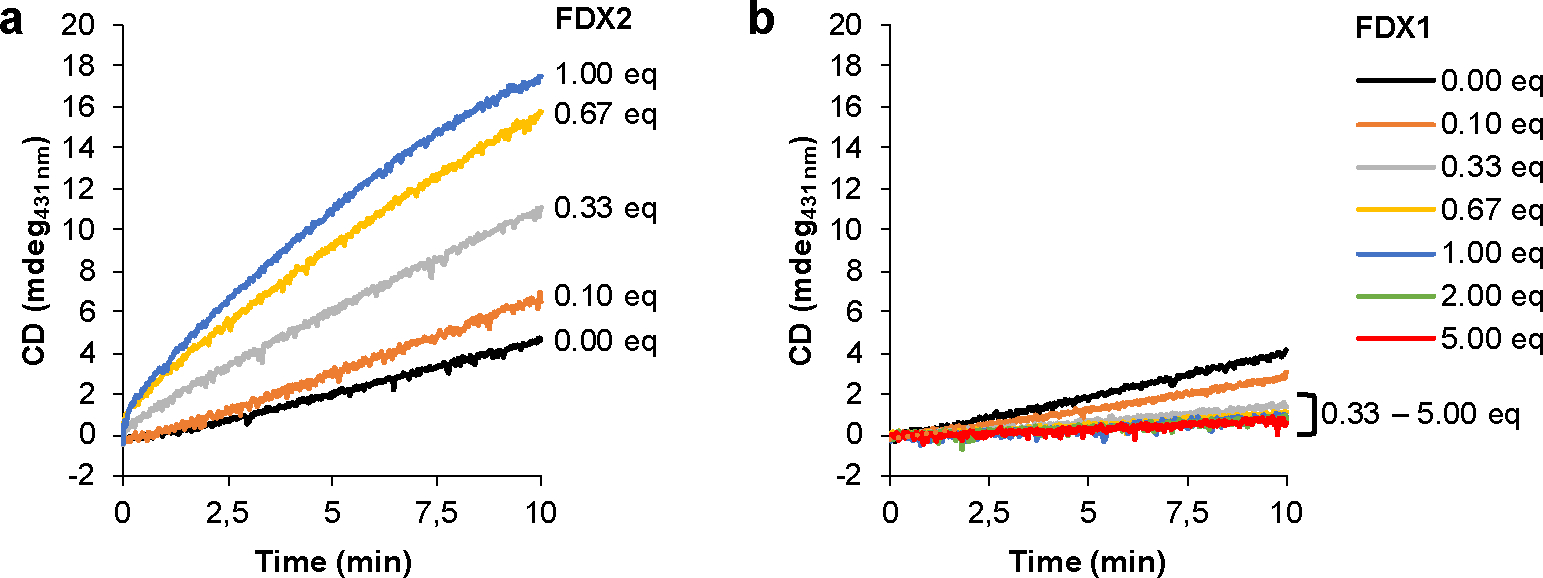

We next compared the capacities of FDX1 and FDX2 to in vitro donate electrons to the initial step of Fe/S protein biogenesis, i.e. the de novo [2Fe-2S] cluster synthesis on the scaffold protein ISCU2 by enzymatic function of the cysteine desulfurase complex NFS1-ISD11-ACP1 (NIA) and frataxin (FXN)9,15,30. [2Fe-2S] cluster formation was measured by circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy, and strictly depended on FDX2 addition up to equimolar amounts to NIA (Fig. 1d; Extended data Fig. 2). In contrast, even a fivefold excess of FDX1 over NIA did not support any [2Fe-2S] cluster synthesis above control reactions performed without any FDX. In summary, our in vivo and in vitro results do not indicate a direct role of FDX1 in human Fe/S protein biogenesis, in contrast to previous suggestions8,30. Rather, the data support and extend earlier findings indicating a vital role of FDX2 as the exclusive physiological electron donor in mitochondrial Fe/S protein biogenesis6,9,18.

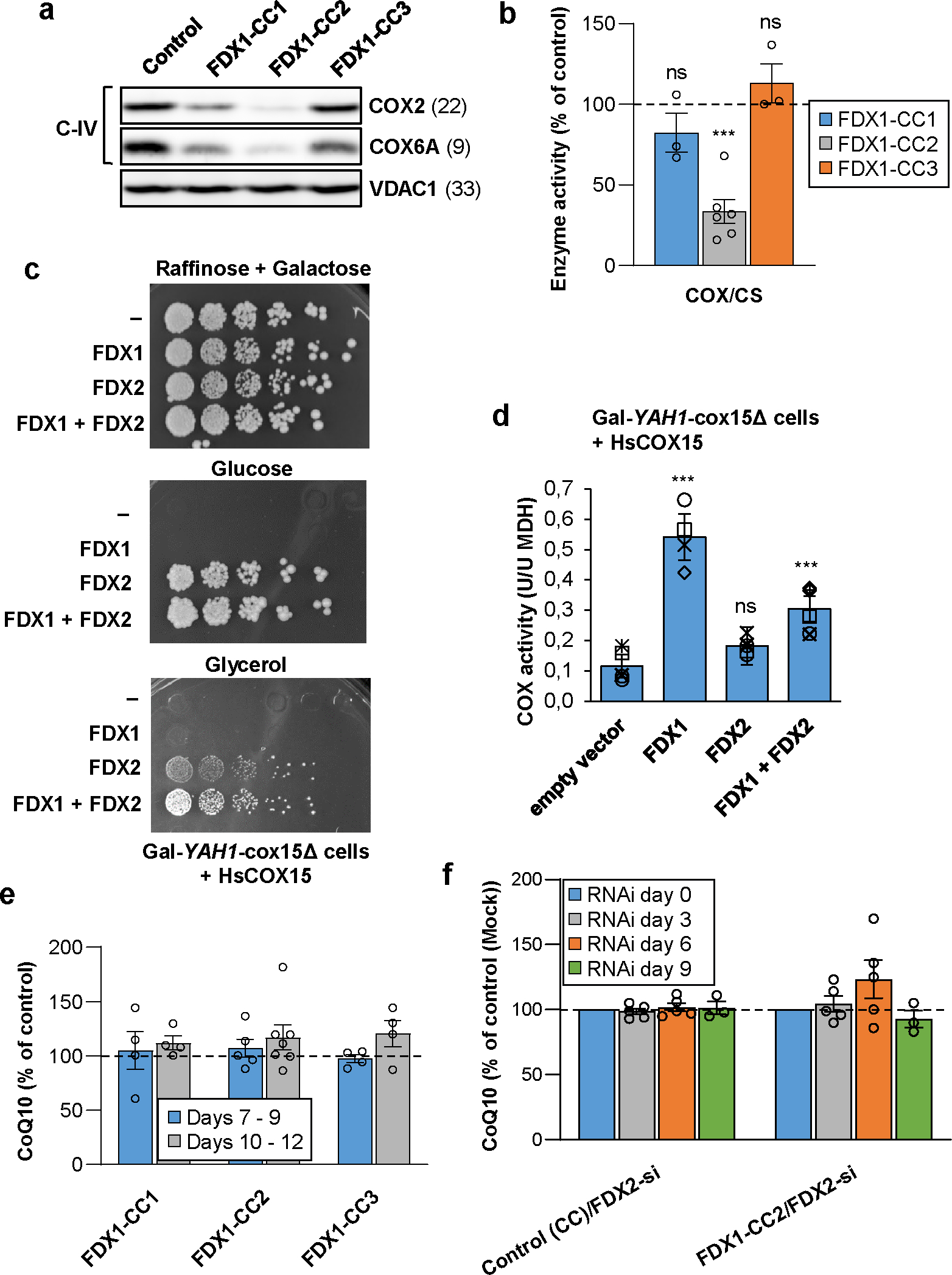

A crucial role of FDX1 in heme a-dependent cytochrome c oxidase activity

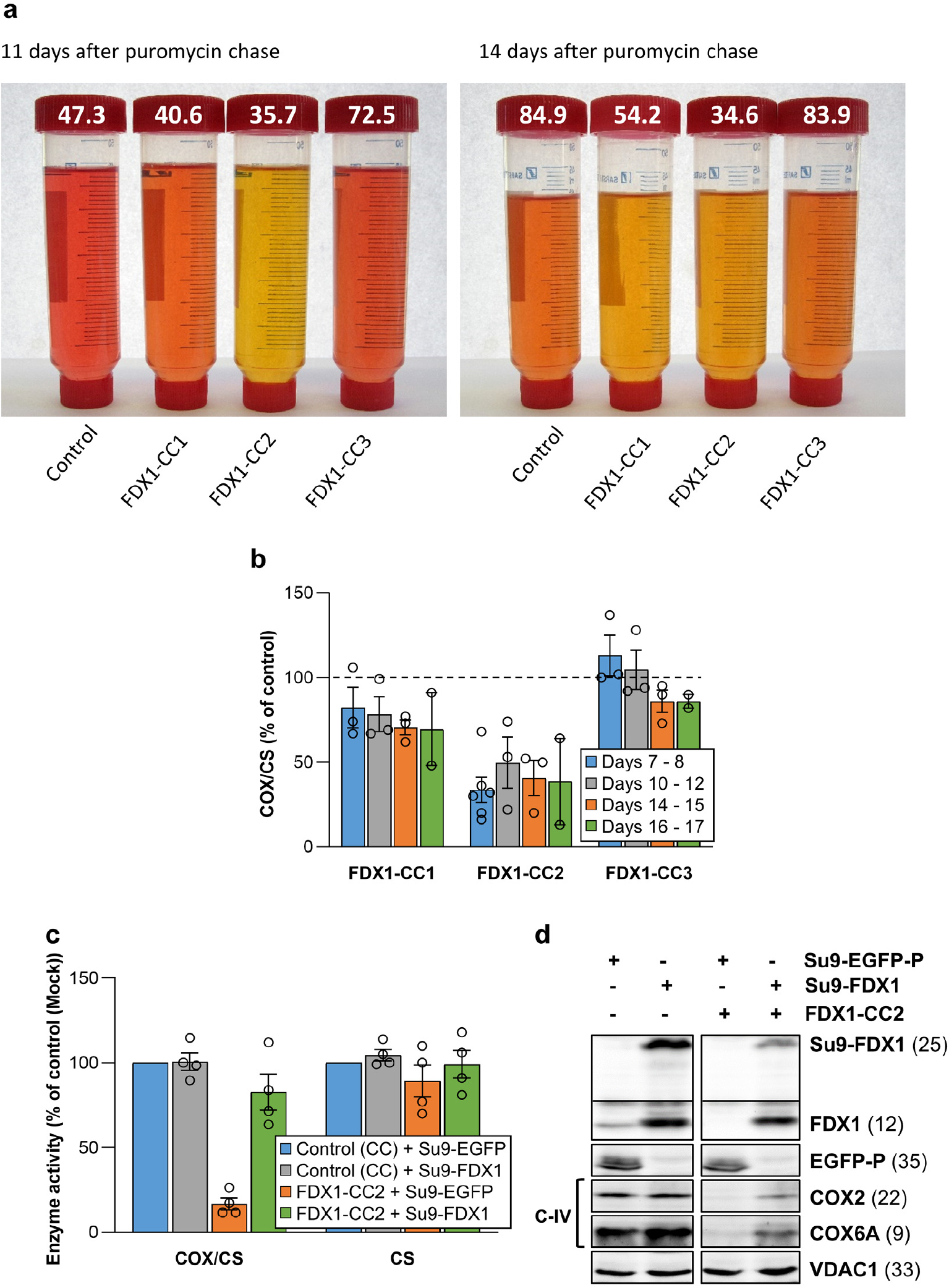

We next sought to find an explanation for the substantial growth retardation upon FDX1 gene knockout. The culture medium of FDX1-deficient cells showed a profound acidification (Extended data Fig. 3a), indicating a metabolic switch from mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation to glycolysis. Since respiratory complexes I-III and aconitase were unaffected in these cells (cf. Fig. 1b,c), we analyzed the activity of respiratory complex IV (cytochrome c oxidase, COX). We found a diminution in the levels of COX2 and COX6A subunits and a substantial decrease in COX enzyme activity (Fig. 2a,b; Extended data Fig. 3b). These effects were specific because complementation of FDX1-deficient cells by mitochondria-targeted FDX1 recovered both COX subunit levels and activity (Extended data Fig. 3c,d).

Fig. 2. The role of human ferredoxins in heme a and CoQ10 biosynthesis.

a HEK293 cell extracts from Fig. 1b were subjected to immunostaining of indicated cytochrome c oxidase (complex IV, C-IV) subunits. VDAC1 served as loading control (see Fig. 1b). Observed molecular masses (kDa) for proteins are given in parentheses. Representative blots are shown. b COX activity (relative to CS activity) was analyzed in total membrane fractions derived from cells treated as in Fig. 1c (n ≥ 3; one-way ANOVA for control versus FDX1-CC1–3, ***p < 0.001). c Gal-YAH1-cox15Δ yeast cells were transformed with plasmids encoding human COX15 and additionally FDX1, FDX2 or no FDX (−) as indicated. Subsequently, cells initially grown in liquid SC glucose medium were plated as a 1:5 dilution series, and grown for 3 days at 30°C on the indicated minimal media. d COX activities (relative to malate dehydrogenase, MDH) were determined in extracts from cells of part (c) grown for 3 days in liquid SD medium (n ≥ 4; one-way ANOVA for empty vector control versus FDX-complemented cells, ***p < 0.001). e HEK293 cells transfected as in Fig. 1b were harvested within the indicated time intervals after puromycin selection. Total cellular coenzyme Q10 (CoQ10) content per total cellular protein was determined and presented relative to the value of control cells (n ≥ 4). f HEK293 cells were chemically transfected with the FDX1-directed gRNA-encoding plasmid CC2 or with the PX459 control plasmid. Six to seven days after puromycin selection cells were repeatedly transfected by electroporation at a three-day interval with a pool of FDX2-directed siRNAs, and harvested up to 9 days after the first transfection similar to Fig. 1a. At each transfection round cell samples were removed for the analysis of total cellular CoQ10 content as in (e) (n ≥ 3). CoQ10 levels were normalized to amounts before starting RNAi depletion. Error bars show the SEM.

COX lacks Fe/S clusters, and consistently RNAi-mediated depletion of FDX2 only weakly affected COX2 or COX6A subunit levels, in contrast to the severe decrease upon FDX1 gene knockout (Fig. 2a; Suppl. Fig. 2b). COX contains two Cu centers and heme a/a3 cofactors that are derived from heme b by COX10-dependent farnesylation (yielding the intermediate heme o) and COX15-catalyzed formylation24,26,35–37. A role of FDX1 in heme b synthesis as an explanation for the COX defect was excluded, because heme b-containing complexes II and III were not altered in FDX1 knockout cells (Fig. 1b,c; Extended data Fig. 1b–d). In S. cerevisiae, Cox15-dependent heme a formation requires the function of ferredoxin Yah1, suggesting that the impaired COX function in FDX1 knockout cells may be caused by a heme a synthesis defect. A direct measurement of heme a levels by HPLC24 or mass spectrometry failed due to detection limits. Notably, FDX1-deficient cells (CC2-based knockout) retained 33% of wild-type COX activity, likely due to the presence of FDX2 (Fig. 2b; Extended data Fig. 3b). Consistently, RNAi depletion of FDX2 was associated with some decrease in COX subunit levels and activity (Suppl. Fig. 2b)6. Since this effect is also seen upon depletion of other ISC factors including the ISCA-IBA57 proteins38, it may be an indirect consequence of FDX2 depletion on COX. Collectively, FDX1 performs a critical role for COX activity, presumably by its function in heme a synthesis, yet FDX2 may partially replace FDX1 in this process.

Our previous FDX1 and FDX2 complementation studies in Yah1-depleted Gal-YAH1 yeast cells had indicated a (weak) requirement of FDX2 but not FDX1 for yeast COX activity6, challenging our results with human cells. We reasoned that this discrepancy may be due to a failure of human FDX1 to properly interact with yeast Cox15 during heme o to heme a conversion. We therefore expressed human COX15 in the regulatable yeast strain Gal-YAH1-cox15Δ in which yeast COX15 was deleted. When Yah1 was depleted by growth in the presence of glucose (Glc) or glycerol (Gly)7, cells showed a growth defect that could be rescued only by expression of FDX2 but not by FDX1, consistent with the vital function of FDX2 in Fe/S protein biogenesis (Fig. 2c). However, under respiratory growth conditions (Gly-containing medium) only the combined expression of FDX1 and FDX2 resulted in full growth complementation, indicating independent, complementary functions of the two human FDXs. Measurement of COX activity in extracts of Yah1-depleted Gal-YAH1-cox15Δ cells still showed low residual COX activity, due to the leaky GAL promoter (Fig. 2d). Upon FDX1 complementation, COX activity increased ca. 3-fold, despite the severe growth defect under this condition. In contrast, FDX2 complementation did not recover COX activity, despite normal cell growth on glucose-containing medium due to restored Fe/S protein biogenesis. These results for COX15-humanized yeast perfectly support our observations with human cells, implying that FDX1 is the predominant human ferredoxin supporting COX15-dependent heme a formation.

Both human ferredoxins are dispensable for ubiquinone biosynthesis

In S. cerevisiae, both Yah1 and Arh1 are essential for the biosynthesis of ubiquinone (coenzyme Q6; CoQ6) by supporting Coq6-catalyzed hydroxylation of precursor compounds27,28. The electron donor for the biosynthesis of human ubiquinone (CoQ10) is unknown, and we therefore tested the potential function of the two human FDXs in this process. Determination of cellular CoQ10 levels in FDX1 knockout cells did not diminish CoQ10 levels, not even upon prolonged tissue culture following puromycin selection (Fig. 2e). Likewise, FDX2-deficient cells contained wild-type levels of CoQ10 even after 9 days of RNAi-mediated depletion (Fig. 2f, left) when cells showed a growth defect (Extended data Fig. 4a). We analyzed CoQ10 levels in FDX2-depleted FDX1 knockout cells to test a potential redundant function of the FDXs. The FDX double-deficient cells showed a more profound growth retardation compared to single depletions (Extended data Fig. 4a), yet no significant changes in CoQ10 levels (Fig. 2f, right), despite severe diminution of mitochondrial Fe/S protein levels (Extended data Fig. 4b). This result indicates that CoQ10 synthesis in human cells is FDX-independent, and, unlike in yeast, may involve another, still unknown oxidoreductase.

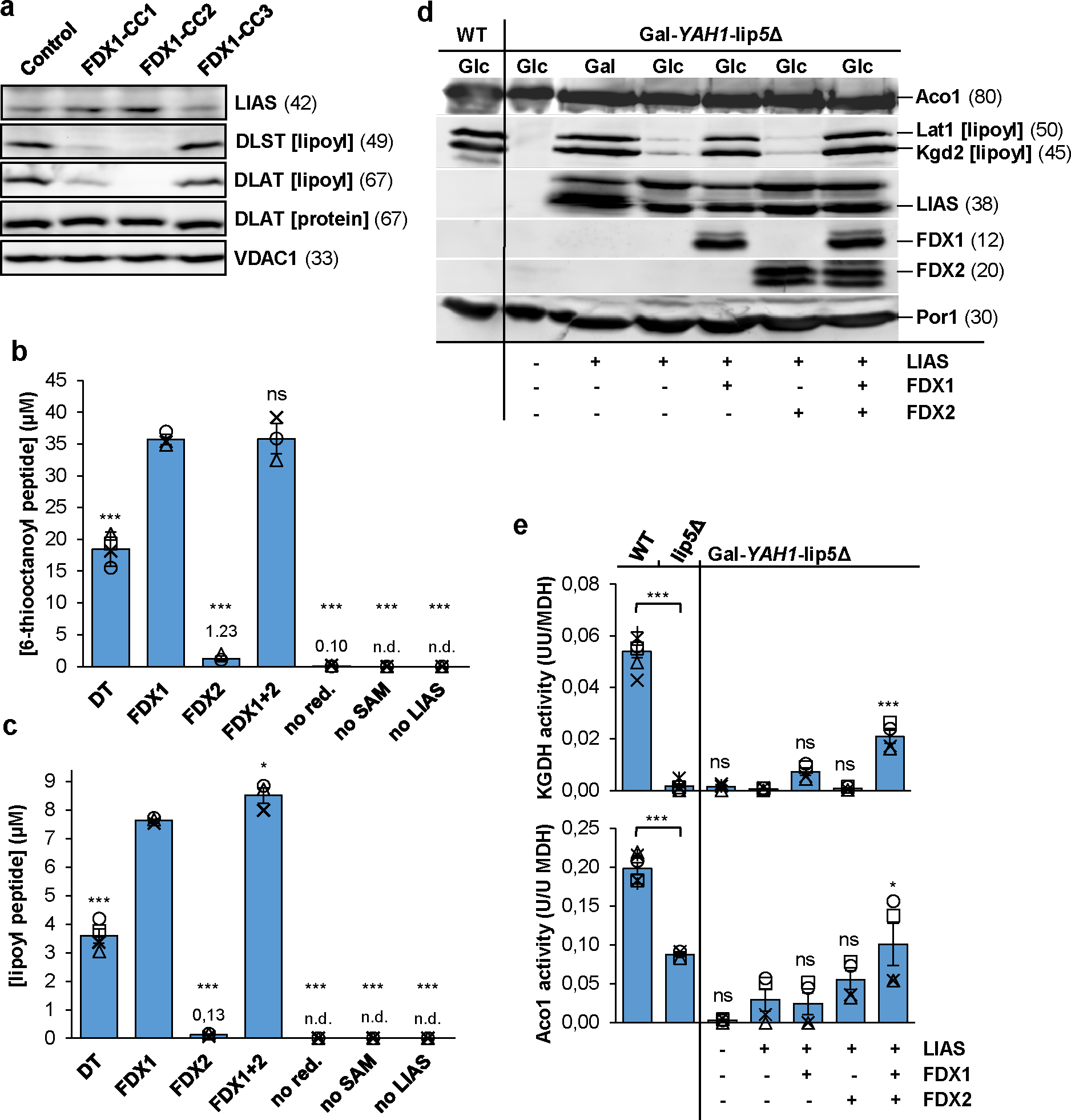

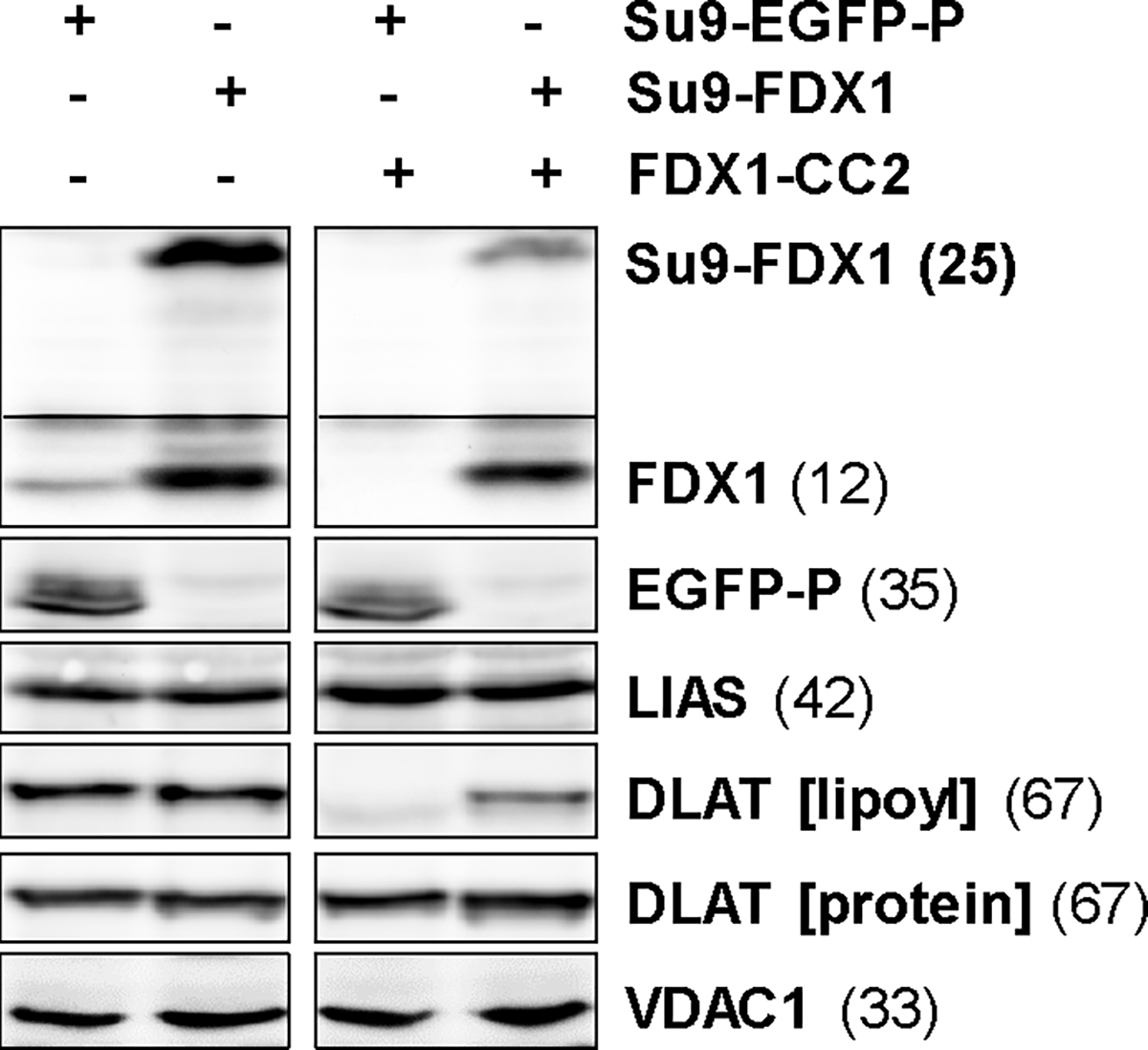

FDX1 functions as a radical chain starter for LIAS-dependent lipoyl synthesis

To search for reasons of the growth defect and metabolic switch of FDX1 knockout cells, we next performed anti-lipoyl immunostaining, and thereby identified a strong lipoylation defect of the E2 subunits dihydrolipoyl transacetylase (DLAT) and dihydrolipoyl succinyl transferase (DLST) of pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) and α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase (KGDH), respectively (Fig. 3a)39. The steady-state levels of the DLAT protein and of the radical S-adenosyl methionine (SAM) Fe/S enzyme lipoyl synthase (LIAS) remained unchanged. Complementation of FDX1-deficient cells by expression of mitochondria-targeted Su9-FDX1 recovered DLAT lipoylation (Extended data Fig. 5). This finding suggests a crucial function of FDX1 in lipoylation, an observation not revealed by the less severe RNAi depletion of FDX1 (cf. Suppl. Fig. 2b).

Fig. 3. FDX1 starts the radical chain reaction of lipoyl biosynthesis.

a HEK293 cell samples from Fig. 1b were immunostained for the indicated proteins or the lipoyl cofactor. VDAC1 served as loading control (see Fig. 1b). Observed molecular masses (kDa) for proteins are given in parentheses. Representative blots are shown. b, c Formation of the (b) 6-thiooctanoyl and (c) lipoyl peptide from a peptide substrate analogue [Glu-Ser-Val-(N6-octanoyl)Lys-Ala-Ala-Ser-Asp] by LIAS. Samples contained 0.5 mM peptide substrate, 35 μM LIAS, 2 mM NADPH, 20 μM FDXR, 140 μM FDX1, and 1 mM SAM, unless indicated otherwise. Dithionite (DT) samples lacked FDX1, FDXR, and NADPH. Reactions were incubated at 23°C, quenched with acid after 2.5 h, and products quantified by HPLC-MS using peptide standards (n ≥ 3; one-way ANOVA for FDX1 reactions versus all other conditions). d Gal-YAH1-lip5Δ yeast cells harboring plasmids encoding human LIAS, FDX1 and/or FDX2 as indicated were grown in minimal medium with glucose (Glc) or galactose (Gal) as indicated for 3 days. Mitochondria were isolated and analyzed for the indicated proteins or lipoyl cofactor in PDH and KGDH by immunostaining. Porin (Por1) was used as loading control. e Mitochondrial extracts were analyzed for aconitase (Aco1) and KGDH activities, and results were normalized to MDH activity. Wild-type (WT) and lip5Δ cells served as controls (n ≥ 4; one-way ANOVA, LIAS-complemented Gal-YAH1-lip5Δ cells versus all other Gal-YAH1-lip5Δ cells). *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001. Error bars indicate the SEM. n.d., not detectable.

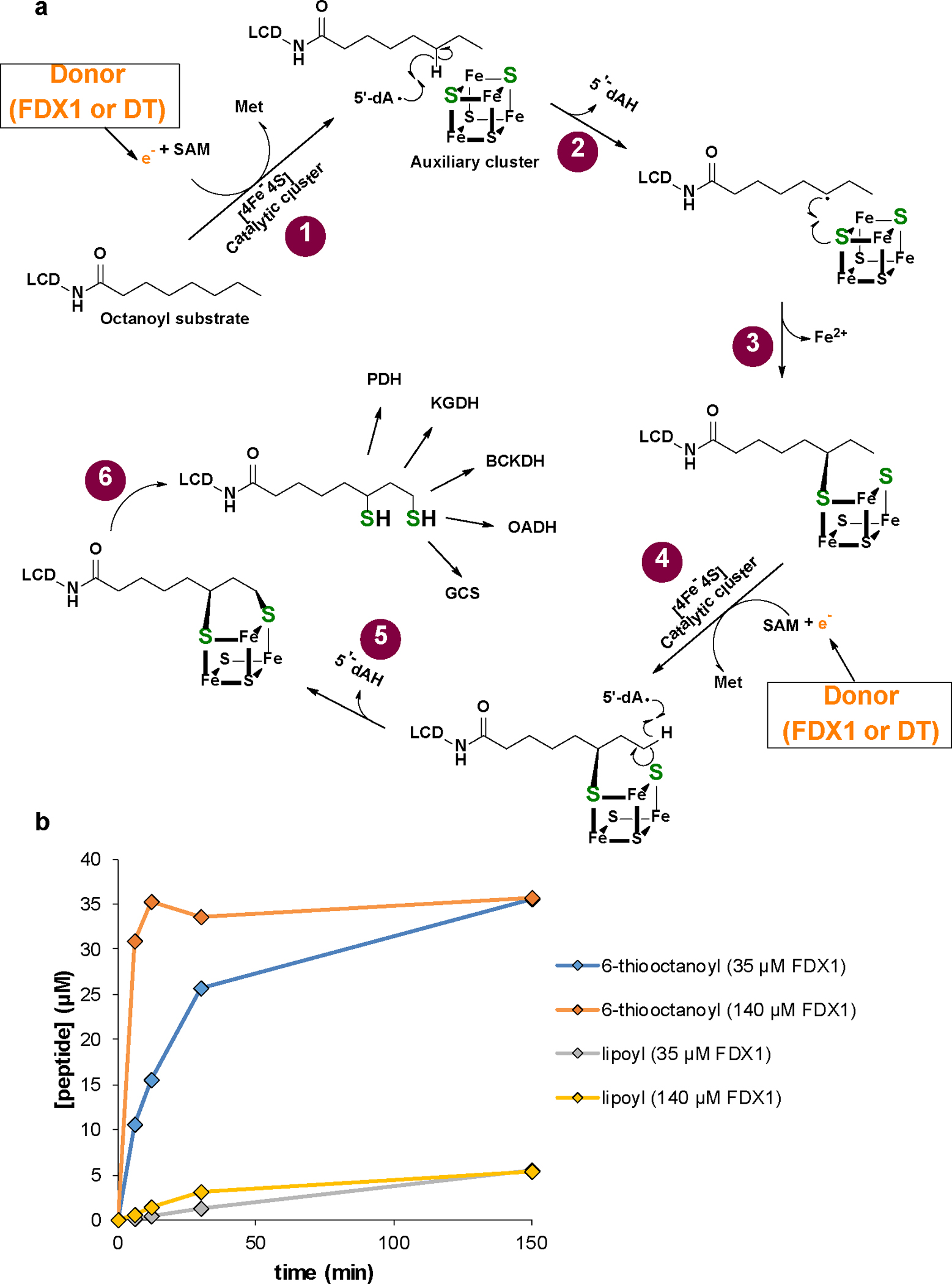

We surmised that FDX1 could act as the so far unknown electron donor starting the radical chain reaction of LIAS (explained in Extended data Fig. 6a)40,41. To test this idea, we adapted an in vitro assay for bacterial lipoyl synthase (LipA) for human LIAS40. An octapeptide containing the octanoyllysyl precursor served as a substrate analogue, and the SAM-dependent formation of both the 6-thiooctanoyl intermediate and lipoyl product under strictly anaerobic conditions was measured and quantified by HPLC-MS. In the presence of the non-physiological reductant DT, normally used to artificially start the radical chain, both the intermediate and product of the LIAS reaction were formed strictly dependent on the presence of DT, SAM, and LIAS (Fig. 3b,c). Strikingly, reduced FDX1 (by action of NADPH and FDXR) could replace DT much more efficiently as an electron source. Both the time courses and final yields for intermediate and product formation differed, comparable to reports for bacterial LipA40, assigning the second sulfur insertion step as being rate-limiting under in vitro conditions (Extended data Fig. 6b). We observed 29- and 61-fold, respectively, lower yields of intermediate and product with reduced FDX2 instead of FDX1 (Fig. 3b,c). This substantial difference suggested FDX1 being the physiological electron donor for LIAS, consistent with our in vivo experiments.

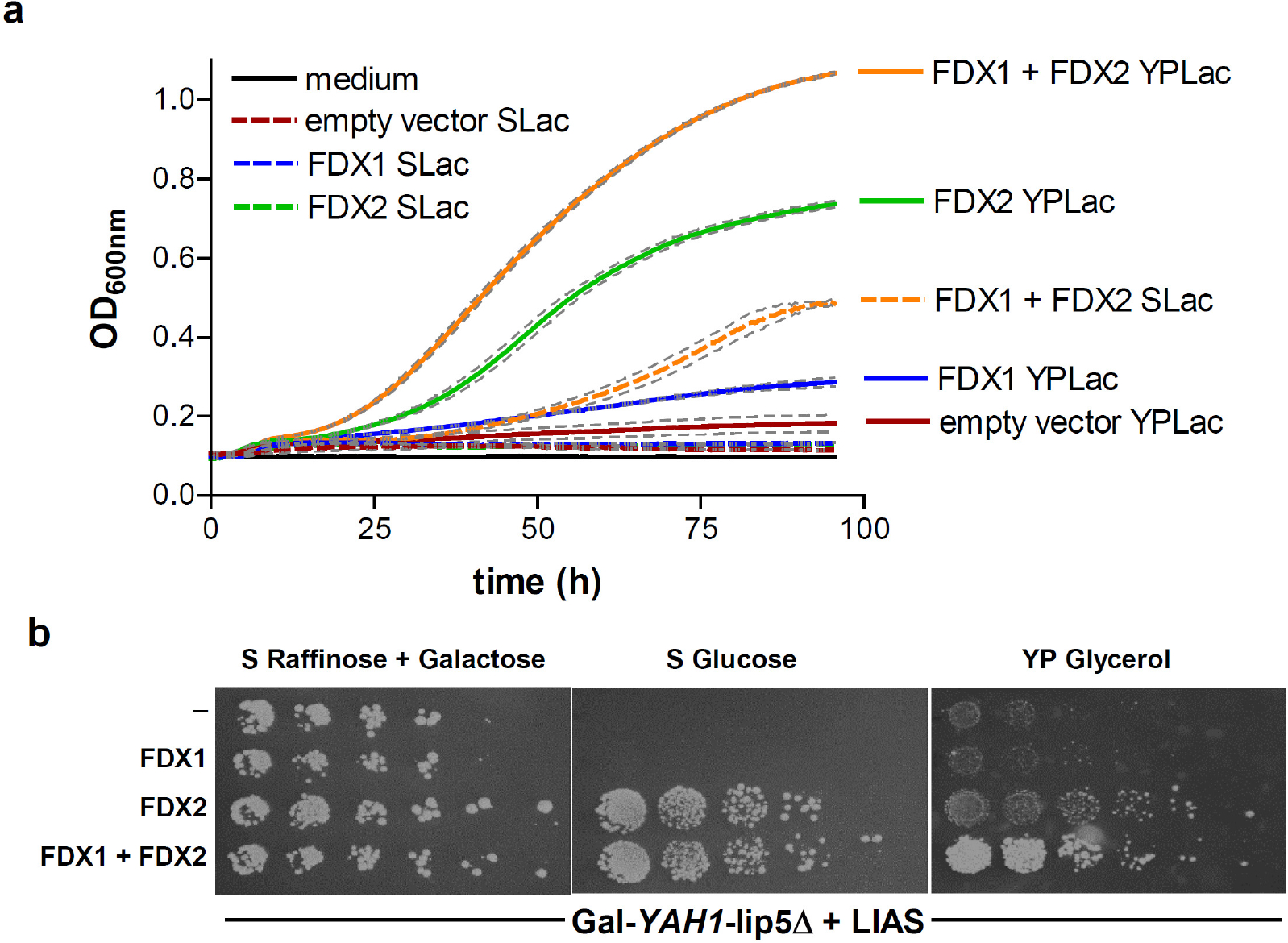

We further took advantage of human LIAS-expressing yeast cells lacking the endogenous LIP5 gene to verify the FDX1 function and specificity in lipoylation. Yeast Gal-YAH1-lip5Δ cells were transformed with plasmids harboring human LIAS, FDX1 and/or FDX2, followed by growth in the presence of either glucose or galactose. As expected, anti-lipoyl staining showed no lipoylation in extracts of Yah1-depleted Gal-YAH1-lip5Δ cells (lacking human LIAS) compared to wild-type cells (Fig. 3d). Lipoylation could be restored to wild-type levels by complementation with LIAS when cells were grown under Yah1-inducing conditions (galactose), but only weakly upon depletion (glucose) of Yah1 that is needed for LIAS Fe/S cluster maturation during ectopic expression. FDX1 but not FDX2 fully complemented the severe lipoylation defect of LIAS-containing, Yah1-depleted Gal-YAH1-lip5Δ cells. Apparently, the low residual levels of Yah1 in this condition (leaky Gal promoter) were adequate to mature enough FDX1 and LIAS for sufficient lipoylation. The humanized yeast model fully supports the dedicated role of human FDX1 in lipoylation.

To confirm this notion, we measured the enzyme activities of the lipoyl-dependent yeast KGDH and the Fe/S enzyme aconitase in this yeast model (Fig. 3e). As expected, lip5Δ deletion cells lacked KGDH activity, and aconitase activity dropped by half, likely as an indirect effect of impaired mitochondrial metabolism. In Yah1-depleted Gal-YAH1-lip5Δ cells, absent KGDH and low aconitase activities were rescued to the lip5Δ levels only by expression of LIAS, FDX1, and FDX2. The findings indicate the specific, non-overlapping functions of FDX1 and FDX2 in LIAS-dependent lipoylation and Fe/S protein biogenesis, respectively. This view perfectly agrees with the growth behavior of the various LIAS-expressing Gal-YAH1-lip5Δ cells in different liquid or solid media (Extended data Fig. 7).

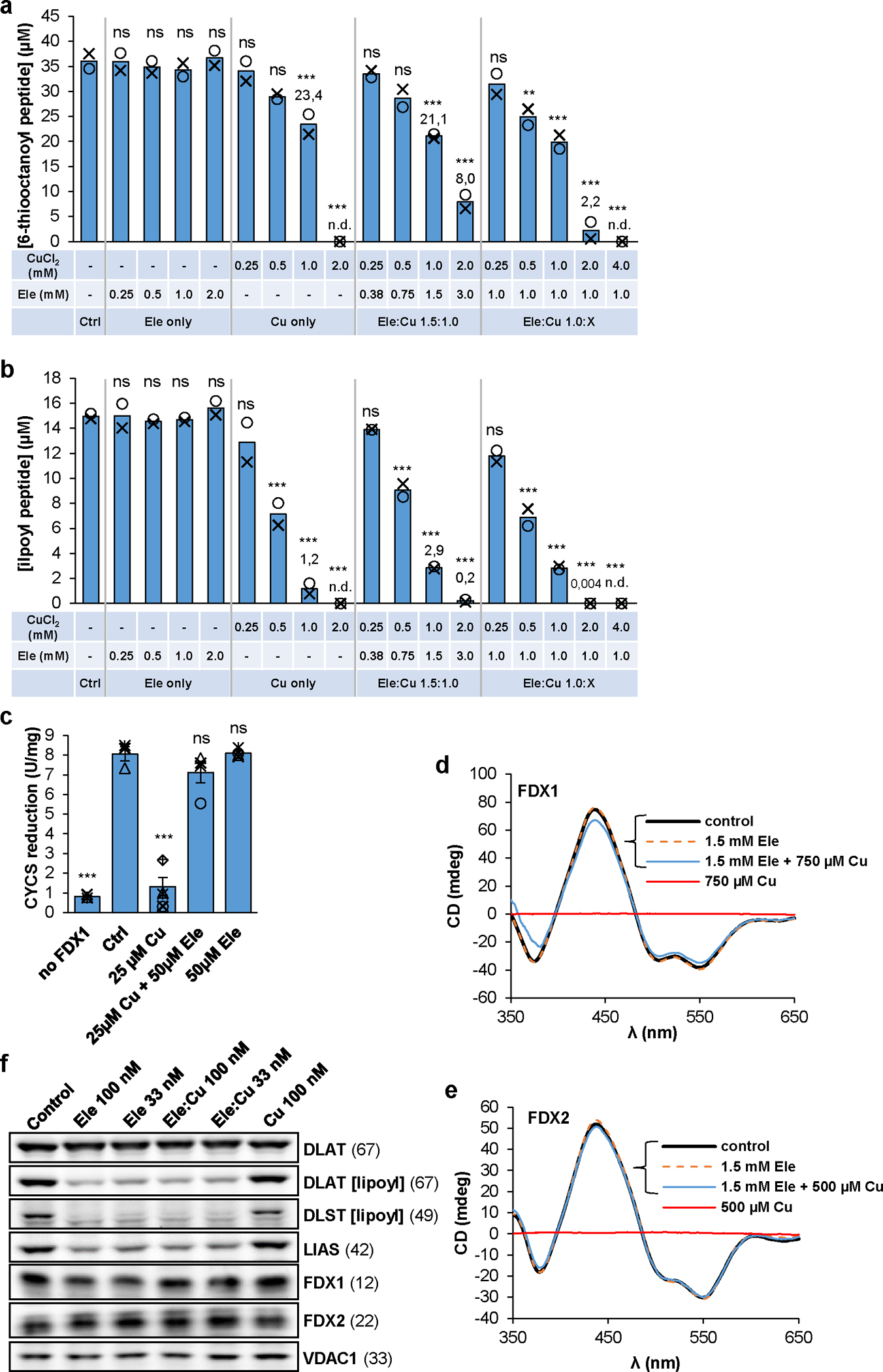

Lipoylation is a primary target of the elesclomol-copper complex

FDX1 has been proposed to the target of the anti-cancer drug elesclomol (Ele) because CRISPR-Cas9 deletion of FDX1 desensitizes these cells against treatment with Ele 32. Ele was shown to be toxic for proteasome inhibitor-resistant cells depending on increased mitochondrial energy metabolism, and it was proposed that Ele imparts a toxic gain of FDX1’s function in Fe/S protein biogenesis. The toxic effect was further shown to be mediated by the complex of Ele with Cu (Ele:Cu) rather than Ele alone32, which is consistent with earlier reports that Ele acts as a Cu ionophore transporting Cu to mitochondria, thereby restoring COX function in Cu deficiency42,43. A study published during review of this work suggested both FDX1 and lipoylation as targets of Ele:Cu toxicity, but no molecular explanations were described33. Our in vivo and in vitro findings refuting FDX1 function in Fe/S protein biogenesis, but showing its role in lipoylation, urged for a biochemical evaluation of the toxic role of Ele:Cu.

We first tested the effects of Ele and/or Cu on LIAS- and FDX1-dependent lipoyl synthesis in vitro. Addition of Ele alone did not affect 6-thiooctanoyl and lipoyl formation, even at a 14-fold excess over FDX1 (Fig. 4a,b; left). In contrast, both Cu and Ele:Cu imposed severe effects on these reactions in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 4a,b; middle and right), fully consistent with reports indicating toxic effects of Ele only in the presence of Cu or other metals32,33,42,44,45. Notably, an excess of Ele over Cu slightly attenuated the synthesis defect. The high stability constant of KEle:Cu(II)=1024.2 L/mol46 suggests that both Cu and Ele:Cu inhibit lipoylation, with Cu being slightly more potent. Similar relative impacts of Cu and Ele:Cu have been observed for superoxide dismutase enzyme activity44. Collectively, our in vitro results identify lipoylation rather than Fe/S protein biogenesis as a sensitive target of Ele:Cu toxicity. In particular, the second sulfur insertion step appears to be most affected (Fig. 4a,b; Extended data Fig. 6a). Since lipoyl-dependent PDH and KGDH are central components of mitochondrial metabolism, our findings satisfactorily explain why particularly cells dependent on this process are most vulnerable to Ele treatment32.

Fig. 4. Inhibitory effect of elesclomol-copper on lipoyl synthesis in vitro.

a,b Formation and quantitation of the 6-thiooctanoyl- (a) and lipoyl- (b) peptide was as in Fig. 3b,c in the presence of the indicated concentrations of CuCl2 and/or elesclomol (Ele) (n = 2; one-way ANOVA for control versus Ele/Cu titrations, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001). n.d., not detectable. c Reduction of cytochrome c (80 μM) by 1 mM NADPH, 2 nM FDXR, and 0.1 μM FDX1 in samples containing CuCl2 and/or Ele as indicated. Cytochrome c reduction was monitored at 550 nm for 60 s. Error bars indicate the SEM (n ≥ 3; one-way ANOVA, ***p < 0.001). d,e CD spectra of FDX1 (d) and FDX2 (e) recorded after incubation with the indicated amounts of CuCl2 and/or Ele (see also Suppl. Fig. 3). f HEK293 cells were grown in the presence of the indicated amounts of Ele and/or Cu for 72 h before harvesting and immunostaining of the indicated proteins or lipoyl cofactor. Observed molecular masses (kDa) for proteins are given in parentheses. Representative blots are shown.

The in vitro lipoylation assay did not readily allow the discrimination between FDX1 and/or LIAS as potential targets of the Ele:Cu toxicity. To address this issue biochemically, we first studied the impact of Ele and/or Cu on FDX1 during NADPH-FDXR-FDX1-dependent electron transfer to cytochrome c. Reduction of cytochrome c was not affected by addition of Ele or Ele:Cu, yet was fully abolished by Cu (Fig. 4c). The striking difference of this result to the observed inhibition of lipoylation by both Cu and Ele:Cu indicates the LIAS reaction as the preferential target of Ele:Cu and FDX1 as target of Cu only. Consistently, only Cu but not Ele or Ele:Cu destroyed the Fe/S clusters of both FDX1 and FDX2 (Fig. 4d,e; Suppl. Fig. 3), in agreement with the Cu sensitivity of yeast Yah147. Our in vitro findings identifying LIAS function in lipoylation as a target of the toxic effect of Ele:Cu are further supported in vivo. Human cells treated with Ele or Ele:Cu showed a strong impairment of lipoylation and a destabilization of LIAS (not seen upon FDX1 knockout), while DLAT protein and the two FDXs were hardly affected (Fig. 4f). In contrast, Cu alone elicited no detectable effects. Collectively, the biochemical and cell biological results document that the Ele:Cu complex strongly affects LIAS function in lipoylation and may be the target of the toxic effect of Ele (see Suppl. Discussion).

Converting FDX1 into a ferredoxin functional in Fe/S protein biogenesis

To address the structural basis of the functional specificity of the two human FDXs, we solved the crystal structure of mature FDX2 (residues 66–171; PDB ID: 2Y5C; Suppl. Table 2; Suppl. Results) for comparison with the known FDX1 structure (PDB ID: 3P1M). Significant structural differences between FDX1 and FDX2 were observed only for the loop between helix C and the Fe/S cluster binding site, because the Phe-Gly (FG) dipeptide is missing in FDX2 (Fig. 5a; Extended data Fig. 8; Suppl. Fig. 4; Suppl. Results). Comparison of the surface potentials48 revealed a less negatively charged area of FDX2 (Fig. 5b; Suppl. Fig. 5; Suppl. Results; for details see Discussion), mainly due to exchanges of semi-conserved Asp91FDX1 by His95FDX2 and Glu133FDX1 by Arg135FDX2 (Extended data Fig. 8). Overall, the 3D structures of FDX1 and FDX2 display only minor differences in backbone geometry.

Fig. 5. Identification of structural elements crucial for functional specificity of FDX2.

a Superposition of crystal structures of human FDX1 (gold, PDB code: 3P1M, residues 65–170) and FDX2 (green, PDB code: 2Y5C, residues 69–174). The PheGly insertion in FDX1 (FG loop) is shown in magenta, and the orientation of helix C is indicated by rods. The C terminus is not resolved in the FDX2 structure and corresponding FDX1 residues are not shown. b Electrostatic surface potential calculated by the APBS server (https://server.poissonboltzmann.org) mapped to human ferredoxin surfaces (orientation as in a; color bar covers the range from −10 kT/e to +10 kT/e). The Fe/S cluster binding sites are marked by yellow circles. Red, negative charges; blue, positive charges. c Structure of FDX1 (PDB code: 3P1M, residues 65–184) highlighting regions exchanged with the respective FDX2 sequences. The bottom table provides the residues introduced from FDX2 into FDX1 for functional interconversion. d Complementation of Gal-YAH1 yeast with plasmids encoding FDX2, FDX1 variants depicted in c or no FDX (−). Cells were grown for 3 days on minimal medium (S) with glucose (Glc) or galactose (Gal) using a dilution series of resuspended cells initially grown on SGal plates. Dashed lines separate different agar plates. e Aconitase (Aco) and f catalase (Cat) activities were determined in extracts from Gal-YAH1 cells complemented with the indicated constructs. Cells were grown for 40 h in liquid SGlc medium prior to analysis. Error bars indicate the SEM (n = 3; one-way ANOVA for FDX1-complemented yeast versus all other conditions, *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001).

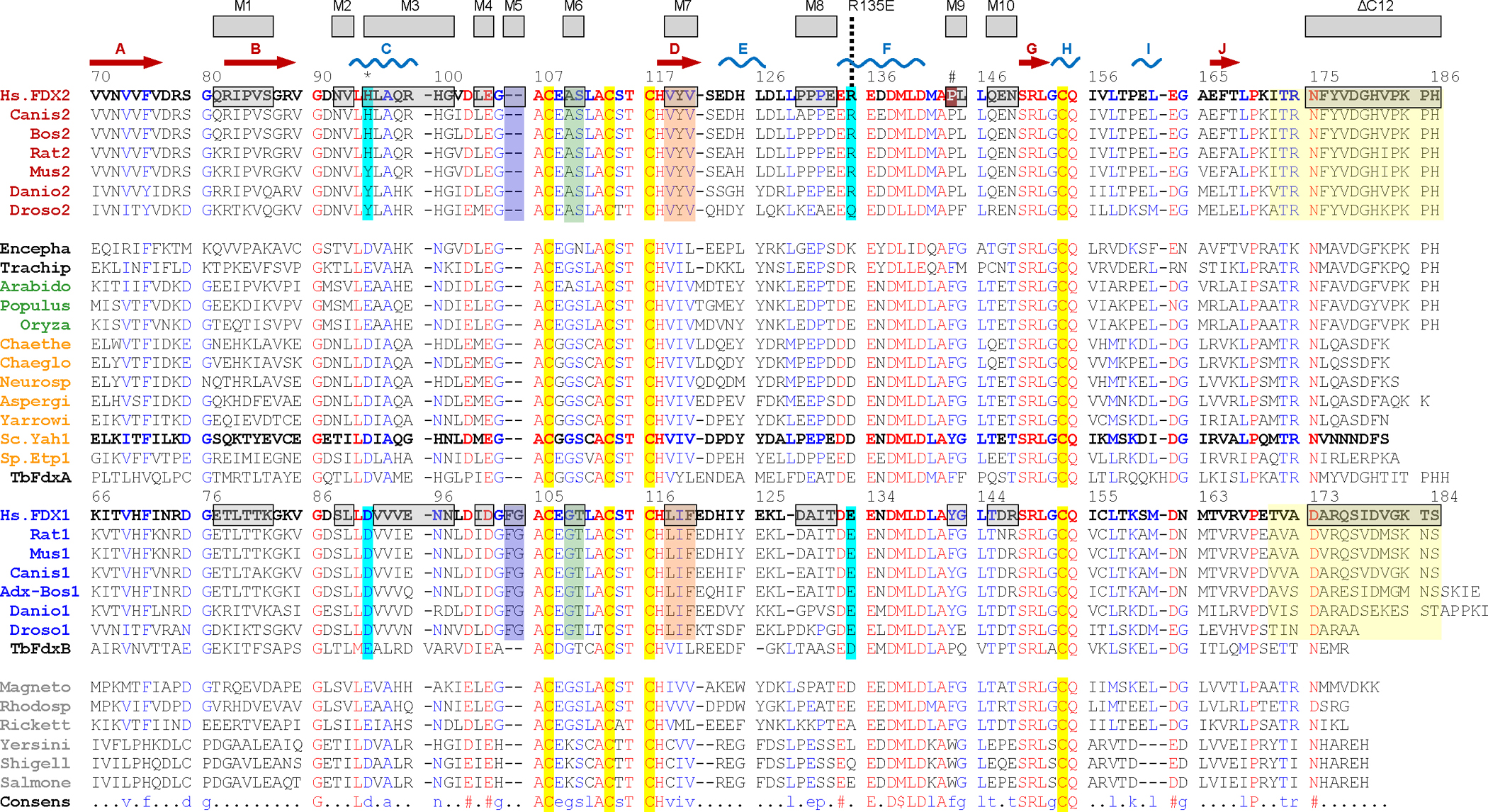

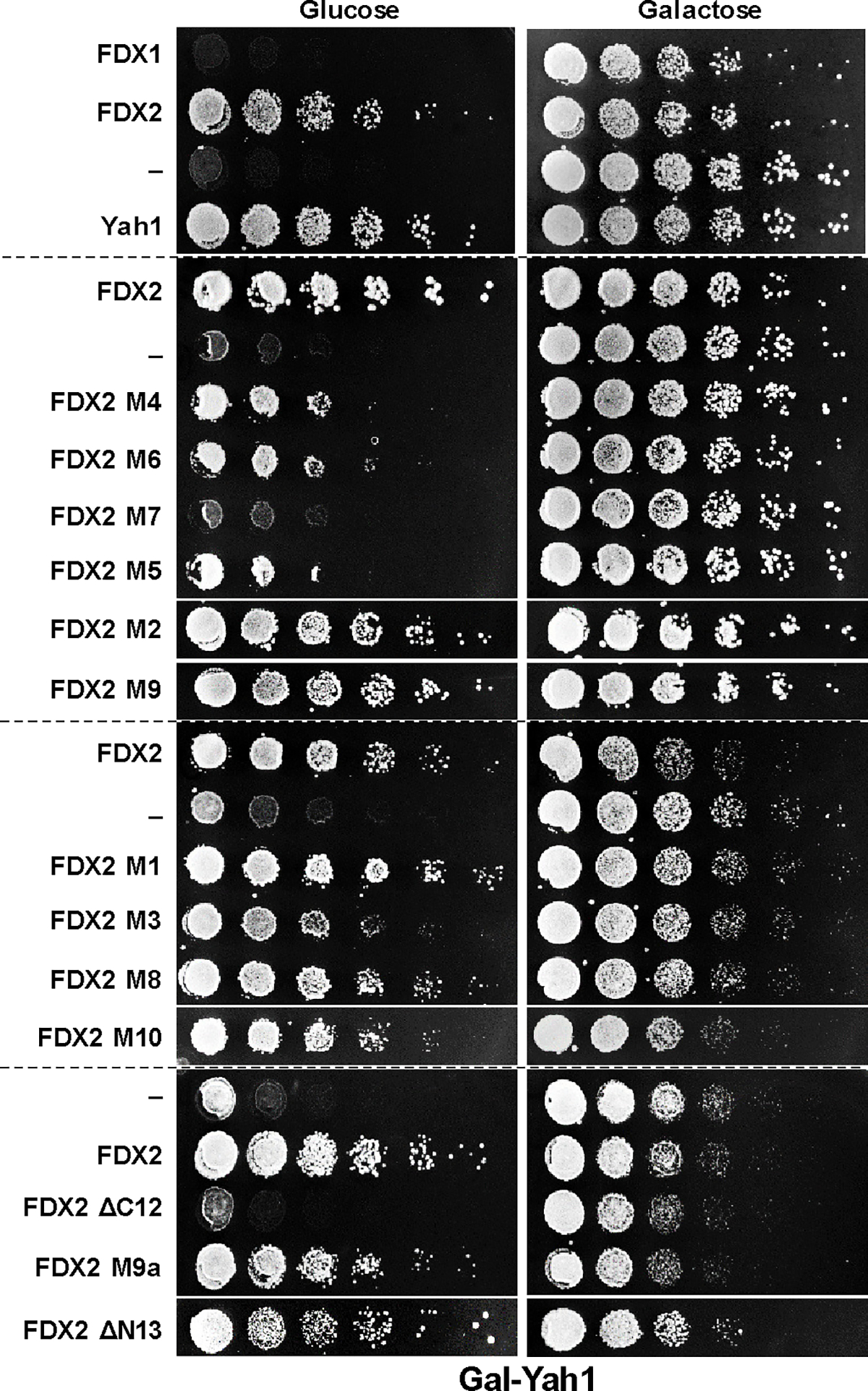

Consequently, we compared multi-sequence alignments of FDX1-, FDX2-, fungal- and bacterial-type FDXs (Extended data Fig. 8). Ten regions (including those structurally pinpointed above) were identified that distinguish FDX1- and FDX2-type proteins (named M1 to M10). We first tested the importance of these regions for FDX2 function by introducing the corresponding FDX1 M1-M10 sequences (Suppl. Table 3), and we examined N- and C-terminal truncations of FDX2 (termed ΔN13 and ΔC12). FDX2 mutant proteins were expressed in Yah1-depleted Gal-YAH1 cells, and growth was analyzed (Extended data Fig. 9). Exchanges of regions M3 to M7 decreased the Yah1-rescuing function of FDX2, with segment M7 showing the most pronounced growth defect. Moreover, the C terminus (ΔC12) but not the N terminus (ΔN13) of mature FDX2 was critical for growth. Hence, region M7 and the FDX2 C terminus are important structural elements for FDX2 function.

Second, we introduced FDX2 segments M1-M10 (either alone or in combination) into FDX1, and we transferred 14 or 27 C-terminal FDX2 residues into FDX1 (exC14 and exC27), in an attempt to generate FDX2 functionality in FDX1 (Fig. 5c,d). Like FDX16, most FDX1 variants did not detectably rescue the growth defect of Yah1-depleted Gal-YAH1 yeast, even though all recombinantly purified proteins contained a [2Fe-2S] cluster, except for FDX1-M5 (deletion of the FG motif), explaining why this mutant is non-functional (Fig. 5d; Suppl. Fig. 6). However, partial growth restoration was observed by introducing the FDX2 C terminus into FDX1. Further growth improvement was obtained by additional exchange of segment M7, particularly in combination with either M3 or M6. Consistent with the findings above (Extended data Fig. 9), region M7 and the C terminus are decisive features of FDX2 functionality, while regions M3 and M6 fulfil a weak auxiliary role. To extend these findings, we measured the enzyme activities of aconitase and catalase (a non-Fe/S protein, yet indirectly affected by Fe/S protein synthesis defects6,49) in Yah1-depleted Gal-YAH1 yeast complemented with FDX1, FDX2, or the growth-restoring FDX1-M3+M7+exC27 or FDX1-M6+M7+exC27 mutant proteins (Fig. 5e,f). While wild-type FDX1 showed no improvement of both enzyme activities in Yah1-depleted cells, both FDX1 mutant proteins restored ca. 30–50% of the activities seen in FDX2-complemented cells. Apparently, small increases in Fe/S protein biogenesis activity by introducing FDX2 functionality into FDX1 can lead to partial growth restoration.

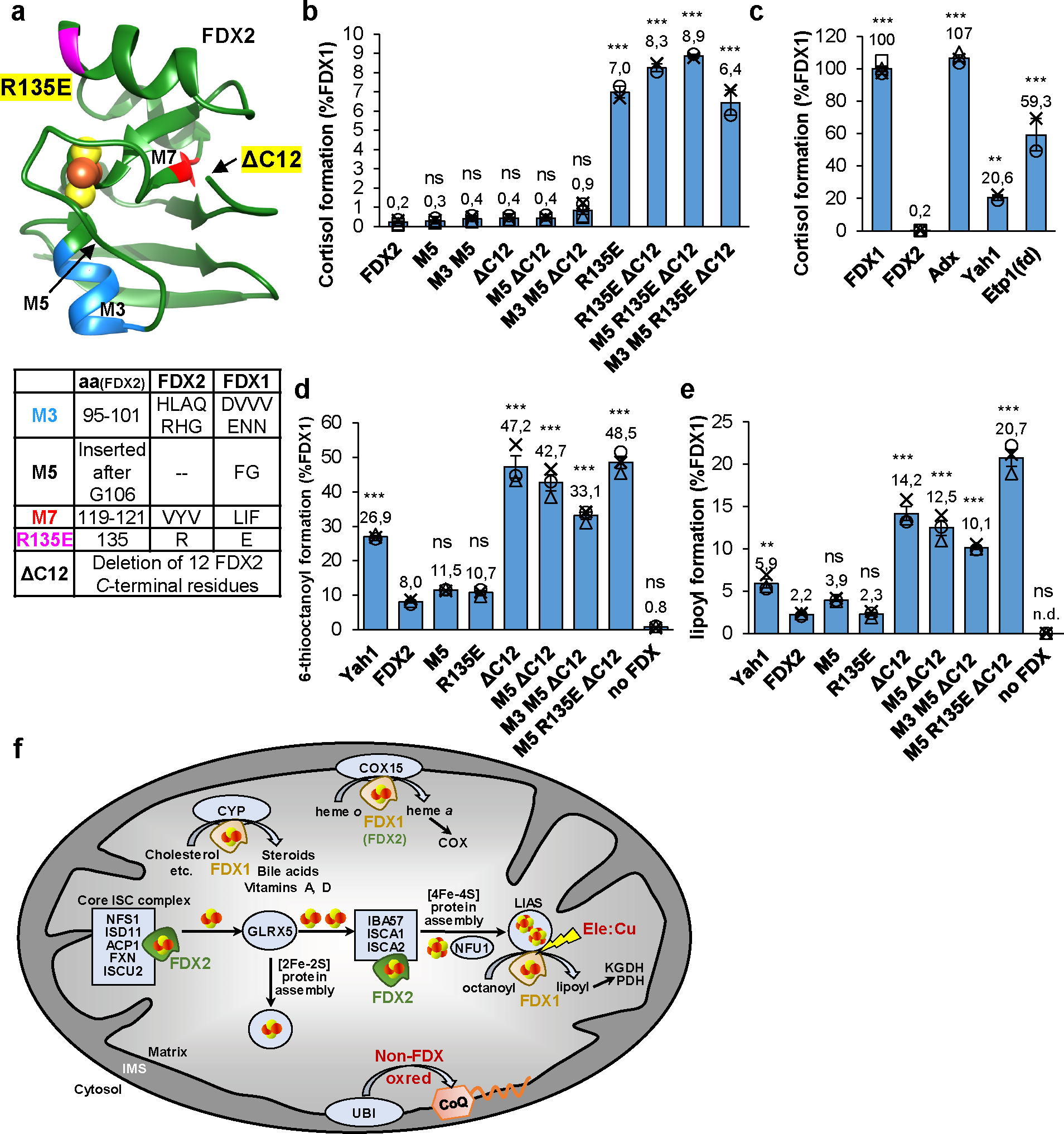

Converting FDX2 into a ferredoxin with FDX1 functionality

In a reversed approach, we sought to identify regions specific for FDX1 functionality. We introduced the FDX-discriminating regions M1-M10 from FDX1 into FDX2, and we deleted the conserved FDX2 C terminus (ΔC12; Fig. 6a; Extended data Fig. 8; Suppl. Table 3). Because simple cell-based in vivo assays were not readily feasible to test restoration of FDX1-specific functions in FDX2, we studied two specifically FDX1-catalyzed reactions in vitro, namely the cytochrome P450-dependent cortisol synthesis from the 11-deoxycortisol precursor5,6 (Suppl. Fig. 7) and lipoylation (cf. Fig. 3b,c). The various FDX2 mutant proteins were recombinantly expressed and purified. They showed close to wild-type UV/Vis spectral properties, except for FDX2-M7 which did not bind any Fe/S cluster, explaining why this segment was essential for FDX2 function (see above; Extended data Fig. 9; Suppl. Fig. 6). Cortisol formation by cytochrome P450 CYP11B1 was efficiently catalyzed by FDX1, but not by FDX26 or several mutant proteins (Fig. 6b,c). In contrast, mutant FDX2-R135E showed a strong (35-fold) increase in cortisol formation compared to wild-type FDX2. Further small improvements were seen by combining this site-specific exchange with the C-terminal deletion (FDX2-R135E+ΔC12) and segment M5 (FDX2-M5+R135E+ΔC12) to yield a 42- and 45-fold stimulation, respectively. Overall, up to 9% of the FDX1-catalyzed cortisol levels were generated, showing that mutated FDX2 is now well, yet not fully capable of steroid production. We conclude that FDX1-specific Glu133 represents a decisive functional element for steroid formation, and the C-terminal truncation provides a further minor contribution. Interestingly, the fungal-type S. cerevisiae Yah1 and S. pombe Etp1fd also supported cortisol synthesis at 20–60% efficiencies compared to FDX1-type human FDX1 and Bos taurus Adx50,51 (Fig. 6c). These fungi contain only one FDX and do not possess mitochondrial cytochrome P450 enzymes52. However, both fungal proteins contain a negatively charged Asp at position Glu133FDX1, re-emphasizing the importance of negative charge at this position for steroid formation.

Fig. 6. Conversion of FDX2 to generate FDX1 functionality.

a Structure of FDX2 (PDB code: 2Y5C, residues: 69–174) highlighting regions exchanged with the respective FDX1 sequences. The bottom table provides the residues introduced from FDX1 into FDX2 for functional interconversion. The site of the C-terminal truncation (ΔC12) is marked by an arrow because the C terminus is not resolved in the crystal structure. b, c Cortisol formation by different FDXs (b) or the indicated FDX2 variants (c) for 10 min at 37°C. Reactions contained 11-deoxycortisol, human CYP11B1, and the electron transfer chain NADPH, FDXR, and ferredoxin. Cortisol content was quantified by HPLC and normalized to FDX1 reactions. (Yah1, Etp1(fd), FDX2 R135E mutants: n = 2, Adx: n = 3, all other reactions: n = 4). d, e Synthesis of 6-thiooctanoyl (d) and lipoyl (e) by LIAS in the presence of different FDXs or indicated FDX2 variants. Formation and quantitation was as in Fig. 3b,c. Values were normalized to FDX1 reactions (n = 3). Error bars indicate the SEM. One-way ANOVA for FDX2 reactions versus all other conditions was conducted in b, c, d, e (**p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001). f Model showing the distinct functions of human FDX1 and FDX2 in mitochondrial metabolism. FDX2 performs a specific function in both de novo [2Fe-2S] cluster assembly by the core ISC complex and the IBA57-ISCA1-ISCA2-dependent reductive fusion of two glutaredoxin GLRX5-derived [2Fe-2S] to [4Fe-4S] clusters18,22. FDX1 cannot replace FDX2 in these functions, yet is shown here to perform two crucial functions in addition to the long-known mitochondrial cytochrome P450 (CYP)-dependent steroid transformation5. First, FDX1 serves as an electron donor to initiate the radical SAM-dependent biosynthesis of the lipoyl cofactor by the [4Fe-4S] protein lipoyl synthase (LIAS). Lipoyl is a cofactor in, e.g., pyruvate and 2-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase (PDH, KGDH) complexes. The LIAS reaction is a sensitive target of the toxic elesclomol-copper (Ele:Cu) anti-cancer drug. Second, FDX1 is involved in cytochrome oxidase (COX) heme a formation by the COX15 enzyme, yet FDX2 can partially replace this FDX1 function. Heme a is exclusively present in cytochrome c oxidase. Different from yeast mitochondria, a non-FDX oxidoreductase (oxred) is required for the biosynthesis of coenzyme Q (CoQ) by the ubiquinone (UBI) complex.

Analogously, the FDX2 mutant proteins were assayed by FDX1-specific lipoylation (cf. Fig. 3b,c). Surprisingly, FDX2-R135E did not significantly improve lipoylation compared to wild-type FDX2 (Fig. 6d,e). Instead, the C-terminally truncated FDX2-ΔC12 variants (without or with additional modifications) showed robust activity increases, enabling up to 49% 6-thiooctanoyl and 21% lipoyl formation compared to FDX1, equivalent to a 6–10-fold increase over FDX2-catalyzed levels. Thus, the C terminus of FDX2 appears to negatively interfere with LIAS interaction, an effect also evident from the ca. 3-fold higher lipoylation (compared to FDX2) by S. cerevisiae Yah1 hosting a shorter C terminus distinct from FDX2 (Fig. 6d,e; Extended data Fig. 8). This result agrees well with the in vivo complementation experiments with LIAS-humanized yeast (cf. Fig. 3d). Collectively, our mutational studies identify different regions of FDX1 (highlighted in Fig. 6a) with importance for either cortisol or lipoyl formation, suggesting that the FDX1 interaction sites with CYP11B1 and LIAS are not identical.

Discussion

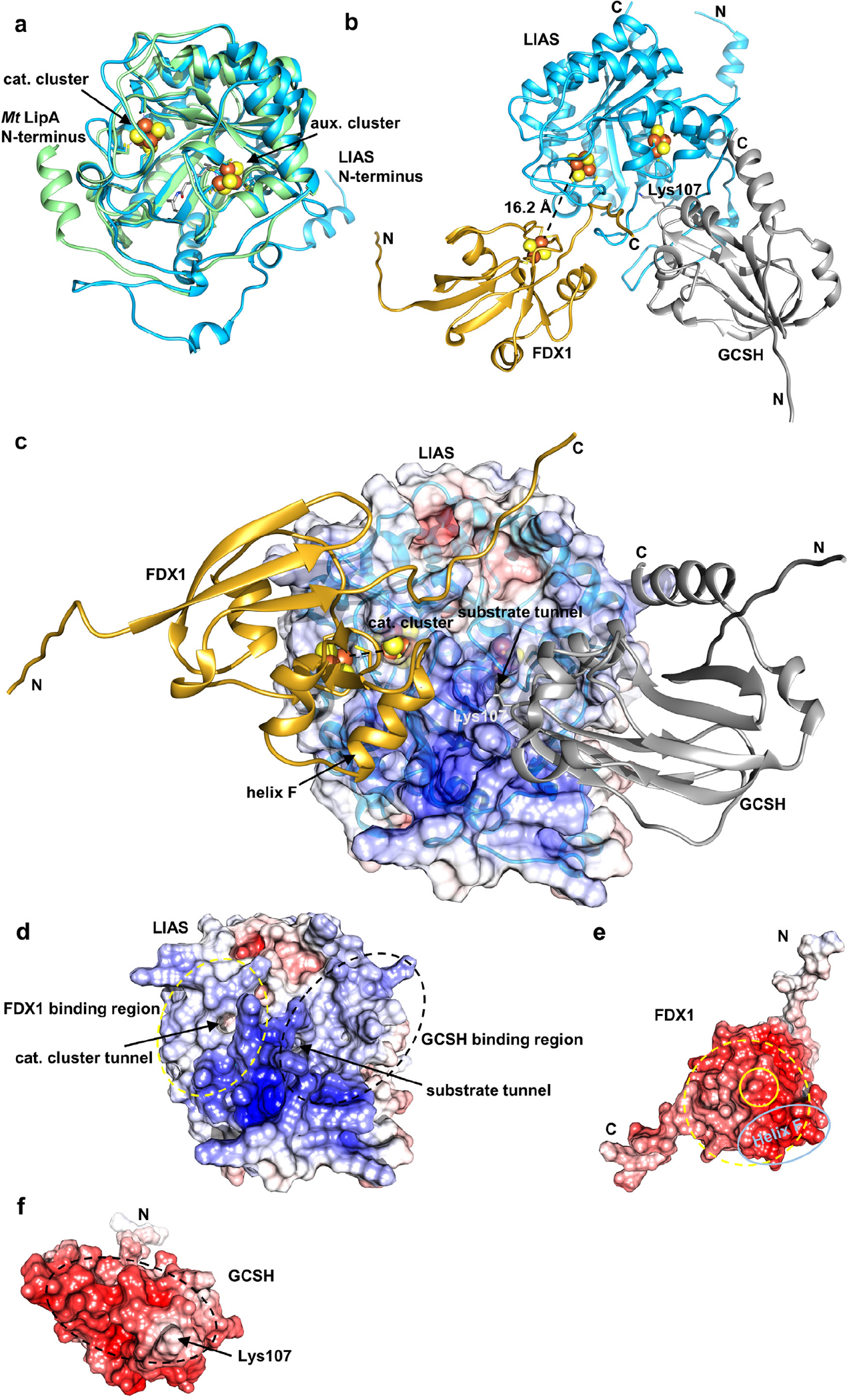

In this work, we have expanded the knowledge on the physiological roles of the mitochondrial ferredoxins FDX1 and FDX2 in human cells by identifying new targets of their electron transfer function and by dissecting the molecular basis of their target specificity (Fig. 6f). A major finding of our study was the identification of the so far unknown molecular function of FDX1 in lipoyl cofactor biosynthesis, half a century after the discovery of its (i.e. adrenodoxin’s) crucial role in steroidogenesis53. Strikingly, both FDX1 and FDX2 are involved in lipoylation, yet perform distinct, non-overlapping roles. While FDX2 as a member of the core mitochondrial ISC machinery assists the assembly of the [4Fe-4S] protein lipoyl synthase (LIAS)22, also FDX1 knockout cells showed a severe lipoylation defect. This was surprising, because FDX1 had no detectable role in Fe/S protein maturation (Fig. 1). To elucidate the molecular basis of this finding, we adapted an in vitro reconstitution system of bacterial lipoyl synthesis for the human pathway40, and show that FDX1 serves as a dedicated electron donor to kickstart the multi-step radical SAM-dependent LIAS reaction (Fig. 3b,c). Frequently, the electron donors of members of the large radical SAM enzyme family are ill-defined41, or the roles of electron donors in either Fe/S cluster assembly or SAM reduction were not dissected 54. Thermotoga maritima [4Fe-4S] FDXs reduce MiaB, and E. coli LipA employs a flavodoxin and its reductase55,56, clearly distinguishing mitochondrial and bacterial lipoylation pathways despite the close evolutionary connection of mitochondria and bacteria10. During in vitro reconstitution of lipoylation, FDX1 was more potent than the artificial reductant DT, yet could not efficiently be replaced by FDX2. The physiological relevance of the FDX specificity was further verified by a human LIAS-expressing yeast model in which endogenous Yah1 was depleted and replaced by FDX1 and/or FDX2. FDX1 but not FDX2 was essential for efficient lipoylation (Fig. 3d,e). Structural modeling using Alphafold showed a trimeric complex between LIAS, GCSH (H-protein of the glycine cleavage system;39) with the octanoyl-carrying loop reaching into the substrate tunnel of LIAS, and FDX1 with its [2Fe-2S] cluster being close to the catalytic cluster of LIAS consistent with direct electron transfer through a tunnel in LIAS (for details see Suppl. Results; Extended data Fig. 10). In contrast, FDX2 could not be modeled in a physiologically relevant position in keeping with its low activity in lipoylation.

FDX1 was further characterized to play a decisive role in COX maturation presumably by facilitating heme a synthesis (Fig. 6f), similar to Yah1 in yeast or FdxA in Trypanosomes4,24. This function became only evident upon FDX1 gene knockout, again suggesting that rather low levels of FDX1 satisfy the cellular needs of heme a production (see Suppl. Discussion). In part, the low FDX1 requirement may be due to a minor activity of FDX2 in this process6, a notion supported by residual COX activity (33%) in human FDX1 knockout cells (Fig. 2b) and our humanized COX15 yeast model expressing FDX1 and/or FDX2 (Fig. 2d). Collectively, FDX1, besides its well-established role in steroidogenesis, shows a functional plasticity to cooperate with multiple target electron acceptors. Even in steroidogenesis, FDX1 is known to interact with multiple mitochondrial cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes5. The array of possible CYP partners of FDX1 might even be extended under certain (sometimes pathological) conditions57,58. We conclude that mammalian FDX1 has evolved to a remarkably versatile enzyme donating electrons to multiple acceptors in different physiological pathways.

In contrast, FDX2 mainly functions in Fe/S protein biogenesis. Given the importance of cellular Fe/S protein biogenesis for life, this FDX2 function is essential for virtually all eukaryotic cells and tissues11, and is even required at two stages within the mitochondrial ISC machinery (see Introduction). In contrast to earlier reports8,30, we did not find any activity of FDX1 in mitochondrial Fe/S protein maturation, neither in vivo in cells lacking FDX1 nor in vitro during enzymatic [2Fe-2S] cluster reconstitution on ISCU2 (Fig. 1). This notion was further supported by our yeast complementation experiments and the mutual interconversion of FDX1 and FDX2 functions (see below). The explanation for these contradictory findings remains unclear, yet a possible reason may be the indirect consequences of both lipoylation and heme a synthesis defects in FDX1-deficient cells on mitochondrial metabolism. Collectively, our study shows a high specialization of each FDX for electron transfer to distinct redox partners.

The high target specificity of the two human FDXs raised the question of what structural or other characteristics these enzymes utilize to discriminate their targets. The reduction potentials of FDX1 and FDX2 at −267 and −342 mV, respectively, cannot readily explain why FDX2 cannot cooperate with typical FDX1 substrates, fitting to a study with bacterial FDXs6,59. To explore structural criteria, we performed mutational studies to swap conspicuous regions between the two FDXs, thereby gaining Fe/S protein biogenesis function of FDX1 or lipoyl and cortisol synthesis activity of FDX2. In each case, only few selected regions showed a substantial activity increase over the low residual activity of each FDX, yet full activity was not reached showing the complexity of substrate selection. A prominent, up to 50-fold increased cortisol formation activity was observed by replacing a positive by a negative residue in FDX2 (mutant R135E; Fig. 6b). While specific ion pair interactions might explain the FDX2 activity gain, the charge inversion also changes the electronic surface potential above the [2Fe-2S] cluster binding site to better resemble that of FDX1-type proteins (Suppl. Fig. 5). In a study of bacterial Fdx-CYP interactions, a similar region was found critical for interaction with a large number of CYP partners59. Strongly negative surfaces can also be found for fungal Yah1 and Etp1fd (containing Asp at position 135) which primarily function in Fe/S protein and heme a biogenesis7,24,27, yet in vitro can perform CYP-dependent catalysis despite the absence of endogenous mitochondrial CYPs in fungi (Fig. 6c)50. Overall, negative ionic interactions and surface potentials may contribute to the specificity of FDX1-type proteins in steroidogenesis. Interestingly, a different structural determinant was critical for FDX1 specificity in lipoylation. Deletion of the conserved C terminus (FDX2 mutant ΔC12) created substantially increased (up to tenfold) lipoylation activity, while mutant R135E was not improved (Fig. 6d,e). This indicates different specificity determinants for FDX1 binding to its dedicated targets CYPs and LIAS. Conversely, FDX1 obtained a gain in FDX2 functionality (e.g., partial growth recovery of Yah1-depleted yeast cells) upon transfer of the conserved C terminus of FDX2 (Fig. 5d–f). A minor growth improvement was obtained by (additionally) exchanging various small segments (M7 with M3, M6) discriminating the two FDXs. This shows that a combination of several regions is crucial to define FDX2 specificity in its major function, i.e. Fe/S protein biogenesis.

Here, we have studied known and novel physiological functions of the two human FDXs and have defined the molecular basis of their specificities. The findings may open avenues for engineering FDXs to function with diverse redox partners or as redox gates in synthetic biology approaches60. An interesting open question concerns the existence of additional FDX targets. Prime candidates are other mitochondrial radical SAM enzymes such as CDK5RAP involved in tRNA modification or RSAD1 with a still unclear function41,61. Future studies may therefore further expand the broad spectrum of FDX targets.

Materials and Methods

Small interfering RNAs and guide RNAs

Sets of three Silencer Select small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) directed against the mRNA of FDX1 or FDX26 were purchased from ThermoFisher Scientific (Waltham, USA). FDX1- and FDX2-directed guide RNA sequences for CRISPR-Cas9-mediated gene knockout (Suppl. Table 1) were designed using E-CRISP62 and cloned into plasmid PX459 (Addgene, Watertown, MA, USA) according to Ref. 63.

Tissue culture and cell transfection

Human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293 cells were cultured in high glucose DMEM with standard supplements and transfected with siRNA by electroporation6 as specified in Supplementary Materials and Methods. PX459-based plasmids allowing for simultaneous expression of gRNA, Cas9, and the puromycin resistance marker were chemically transfected into HEK293 cells using the JetPrime transfection reagent (Polyplus, Illkirch, France) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. In order to facilitate chemical transfection, cells were grown in collagenized flasks, and transfectants were selected by puromycin (10 μg/mL) for two to three days. The day of puromycin removal was considered as day zero of gene knockout, and cells were cultured as lines until use for up to 17 days.

Yeast strains, cell growth and plasmids

Yeast strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Suppl. Table 4 and 5. Cells were cultivated either in minimal medium containing all recommended supplements (SC) or in rich medium (YP) plus the following carbon sources: 2% w/v glucose (SD/YPD), 2% w/v galactose (SGal/YPGal), 3% w/v glycerol (SGly/YPGly), 2% w/v lactate plus 0.05% w/v glucose (SLac/YPLac) or 2% w/v raffinose plus 0.2% w/v galactose (SRaff + Gal)64. Yeast cells were transformed using the lithium acetate method65.

Yeast complementation assays with human genes

For FDX1/2 interconversion experiments, Gal-YAH1 cells7 were transformed with plasmids encoding yeast or human FDXs (p426-FDX1, p426-FDX2, p416-Yah1 and corresponding FDX1/2 mutant plasmids). Single colonies were grown on SGal plates and resuspended in water to OD600 0.5. Serial dilutions (1:5) were spotted onto plates containing different growth media and incubated at 30°C for three days. Enzyme activity measurements of isolated yeast mitochondria were performed as described previously66.

For in vivo lipoyl and heme a formation experiments, Gal-YAH1-lip5Δ and Gal-YAH1-cox15Δ cells were transformed with plasmids p416-FDX1, p415-FDX2, p414-LIAS and p414-COX15. Transformants were grown overnight in SD medium, centrifuged, and cell pellets diluted in water to OD600 0.1. Serial dilutions (1:5) were spotted onto plates containing different growth media and incubated at 30°C for three days.

Reconstitution of de novo Fe/S cluster synthesis on ISCU2

In vitro enzymatic reconstitution of [2Fe-2S] cluster formation on ISCU2 was performed as described9,10. Ferredoxin titration reactions were prepared in an anaerobic chamber and contained 0.5 mM NADPH, 0.8 mM sodium-ascorbate, 0.3 mM FeCl2, 0.2 mM MgCl2, 5 mM GSH, 75 μM ISCU2, 7.5 μM NIA, 7.5 μM FXN, 1 μM FDXR and FDX1 or FDX2 as indicated at a final volume of 300 μL in degassed reconstitution buffer (50 mM Tris/HCl pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl). Reactions were transferred to a CD-spectrometer (Jasco J-815) in a tightly sealed cuvette containing a magnetic stirring bar, and the CD-signal at 431 nm was monitored at 20°C. After 30 s, Fe/S cluster synthesis was initiated by injecting 0.5 mM cysteine into the sealed cuvette and a time course recorded for 10 min. Time courses were normalized to the signal intensity before cysteine addition.

Chemical Fe/S cluster reconstitution on LIAS

Chemical reconstitution of LIAS was done under strictly anaerobic conditions. His-affinity chromatography purified LIAS was diluted to 0.1 mM in degassed LIAS buffer (50 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 300 mM KCl and 20% w/v glycerol) on ice. 10 mM DTT was added, and the mixture was incubated for 1 h. Subsequent addition of 0.8 mM ferric ammonium citrate (FAC) and 0.8 mM Li2S, both added slowly whilst mixing gently, led to a deep brown-yellowish color. Spectroscopic analysis at different time points after reconstitution revealed that the cluster content of LIAS reaches its maximum within 30 min. LIAS was re-purified after 30 min reconstitution by size exclusion chromatography using a HiLoad® 16/600 Superdex® 75 pg column. The holoprotein was characterized as described previously67 by UV/Vis-spectroscopy (Jasco V-550), Bradford assay, amino acid analysis, SDS-PAGE, and iron and sulfide determination.

Lipoyl formation assay

Experiments were done under strictly anaerobic conditions40. Degassed reaction buffer (50 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 300 mM KCl, 10% w/v glycerol) was supplied with 10 mM MgCl2, 2 mM NADPH and 0.5 mM octanoyl peptide (Glu-Ser-Val-[N6-octanoyl]Lys-Ala-Ala-Ser-Asp). Optionally, up to 2 mM CuCl2 and/or elesclomol (Ele) were added. Ele:Cu inhibition assays contained 2% v/v DMSO. Control reactions showed LIAS activity not being altered at concentrations of 0–4% v/v DMSO. 20 μM FDXR, 140 μM FDX and 1 mM S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) were added subsequently. The reaction was started by adding 35 μM reconstituted LIAS to a final volume of 25 μL and incubated at 23°C for 2.5 h, if not noted otherwise. Reactions were quenched by adding 100 mM H2SO4, 4 mM TCEP and 40 μM of an internal peptide standard (Pro-Met-Ser-Ala-Pro-Ala-Arg-Ser-Met). The amounts of octanoyl-, 6-thiooctanoyl- and lipoyl-peptide were quantified by HPLC-MS as described previously67.

Miscellaneous methods

Specific rabbit antisera against human FDX1 and FDX2 were raised using recombinant full-length proteins6,68. For other primary antibodies see Suppl. Table 6. Peroxidase- (Biorad, Germany) or biotin- (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, USA) conjugated goat anti-rabbit and anti-mouse antibodies as well as the ABC system (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, USA) were used as secondary reagents. The following published methods were used: Digitonin-based fractionation of HEK293 cells, activity measurements for aconitase, succinate dehydrogenase, cytochrome c reductase; cytochrome c oxidase, citrate synthase, and lactate and malate dehydrogenase69–71; manipulation of DNA and PCR72; gene disruptions and promoter exchanges in yeast73,74; preparation of yeast mitochondria and cell extracts66; determination of enzyme activities in yeast extracts75; immunological techniques68; in vitro cytochrome c reduction by FDXs18. Measurements of replicates were performed using distinct samples. Statistical analyses were performed via ordinary one-way analyses of variance (ANOVA) with multiple comparisons using Prism software.

Extended Data

Extended data Figure 1 |. Growth phenotypes and mitochondrial Fe/S protein status of FDX1 knockout cells.

a HEK293 cell lines were subjected to CRISPR-Cas9 FDX1 gene knockout using CC1-CC3 guide RNAs. Cumulative growth of cells treated as in Fig. 1b was calculated from cell counts at various harvesting time points after puromycin removal. In detail, individual cell lines were sub-cultured by harvesting an entire culture vessel and subsequent re-seeding of a defined cell number into a new culture device. Remaining cells were collected, and the total protein content of this sample was determined. This protein amount was then used as a denominator for the calculation of the specific (i.e. total protein-related) enzymes activities measured in the respective sample. This tissue culture regime involving the re-seeding of aliquots of harvested cells produced sufficient cell material to conduct multiple analyses, even in case of an experimentally elicited growth retardation. Based on the cell counting performed at each harvest, the cumulative growth was calculated for each cell line from the total cell yield as well as the portion of cells needed for re-seeding during sub-culturing. Values are presented relative to those of control cells (set to 100%, dashed line; n ≥ 4; mean ± SEM). b Densitometric quantification of immunostains from cells treated as in Fig. 1b, 2a, and 3a (i.e. harvested 7 or 8 days after puromycin removal) using Image studio lite 5.2. Error bars indicate SEM (n ≥ 4). c-e Total aconitase (Aco), succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) and citrate synthase (CS) activities were determined in cell samples obtained at the indicated time points after puromycin removal as in Fig. 1c. Values were presented relative to those of control cells (set to 100%, dashed line; n ≥ 3; mean ± SEM).

Extended data Figure 2 |. Even high excess of FDX1 does not support enzymatic [2Fe-2S] cluster reconstitution on ISCU2.

Enzymatic synthesis of [2Fe-2S] clusters on ISCU2 in vitro was monitored by the CD signal at 431 nm for 10 min. Reactions included NIA, FXN, FDXR and the indicated equivalent amounts (eq.) of (a) FDX2 or (b) FDX1 relative to NIA. Representative experiments are shown and initial rates are presented in Fig. 1d.

Extended data Figure 3 |. FDX1 knockout cells are deficient in cytochrome oxidase activity.

a Tissue culture media of HEK293 control and FDX1 knockout cells (cf. Figs. 2a and Extended data Fig. 1a) were collected at the indicated time points. Cells were harvested, counted, and processed as required. The color change of the pH indicator phenol red in the culture medium from reddish toward yellowish, particularly for FDX1-CC1 and -CC2 knockout cells, revealed a pH drop despite lower cell numbers in these cultures (given at the top; in millions). b Cytochrome c oxidase (COX) activities were determined in total membrane fractions from cells harvested at the indicated time points after puromycin removal (cf. Fig. 2b). COX activities were expressed relative to citrate synthase (CS) activities (Extended data Fig. 1e), and values are presented relative to those of control cells (set to 100%, dashed line; n ≥ 3; mean ± SEM). c HEK293 cells (see Fig. 2f) were chemically transfected with control plasmid PX459 or the PX459-derived plasmid FDX1-CC2 and selected by puromycin for 3 days as in Fig. 2a. 10 to 15 days after selection cells were transiently transfected by electroporation with plasmids coding for either a PEST-destabilized EGFP or FDX1, each fused to the N-terminal mitochondrial Su9 targeting sequence (from Neurospora crassa subunit 9 of mitochondrial F1Fo ATP synthase). Three days after transfection cells were harvested and analyzed for COX and CS activities. Data are presented relative to the values for Su9-EGFP control cells (n = 4; SEM). d Cell samples from (c) were subjected to immunostaining against the indicated proteins. Observed molecular masses (kDa) for proteins are given in parentheses. Representative blots are shown.

Extended data Figure 4 |. Combined FDX1 deletion and FDX2 depletion elicits severe defects in growth and mitochondrial Fe/S proteins.

a Cumulative growth of HEK293 cells from Fig. 2f was calculated from cell counts at the three harvests on days 3, 6 (n ≥ 4 each), and 9 (n = 2) after the first electroporation. Values were presented relative to those of mock control cells (no CRISPR, no RNAi treatment; set to 100%, dashed line; mean ± SEM). b HEK293 cells were transfected with FDX1-directed gRNA-encoding plasmids (CC1 to CC3) and subsequently with FDX2-dire siRNAs similar to Fig. 2f. Cell samples were obtained at the specified time points and subjected to immunostaining of the indicated mitochondrial proteins or lipoyl cofactor. The observed molecular weights are given in parentheses. C-I, C-II, C-III, respiratory complexes I, II, and III. C-V, F1Fo ATP synthase. The immunoblot signals from cell samples with combined FDX1-CC2 and FDX2-si deficiency are representative for at least three independent experiments, and are here presented conjointly with FDX1-CC1 / FDX2-si and FDX1-CC1 / FDX2-si treated cells, respectively.

Extended data Figure 5 |. The lipoylation defect in FDX1 knockout cells can be complemented by FDX1.

HEK293 cells from Extended data Fig. 3c,d knocked out for FDX1 (by FDX1-CC2 gRNA) and complemented with Su9-EGFP-PEST or Su9-FDX1 plasmids were subjected to immunostaining against the indicated proteins or lipoyl cofactor. Observed molecular masses (kDa) for proteins are given in parentheses. Representative blots are shown.

Extended data Figure 6 |. In vitro synthesis of 6-thiooctanoyl intermediate and lipoyl product by human lipoyl synthase LIAS requires ferredoxin FDX1 as an electron donor.

a Model of the multi-step reaction mechanism of lipoyl formation by human lipoyl synthase (LIAS) based on bacterial LipA1. The LIAS enzyme contains two [4Fe-4S] clusters, the catalytic and auxiliary cluster, needed for reductive cleavage of S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) and as a source for sulfur insertion into the octanoyl precursor, respectively. (1) The reaction starts with the binding of SAM and the octanoyl substrate which is covalently attached to a lysinyl residue of a lipoyl carrier domain (LCD) of the H protein of the glycine cleavage system (GCS)1,2. An electron donor (orange) transfers a single electron to the catalytic cluster which mediates reductive cleavage of SAM to methionine and a 5’-deoxyadenosyl radical (5’-dA·). This work identified human FDX1 as the physiological electron donor, efficiently replacing dithionite that typically is used as an artificial electron donor1. (2) The radical abstracts a hydrogen atom from the octanoyl C6 carbon, forming 5’-deoxyadenosine (5’-dAH). (3) The octanoyl C6 carbon in turn forms a covalent bond with a sulfur atom of the auxiliary cluster, concomitant with partial degradation of the cluster. (4) A second SAM molecule binds to LIAS, and upon electron supply from FDX1 (or DT) again leads to 5’-dA· radical formation by the catalytic cluster and abstraction of a proton from the terminal C8 carbon of the octanoyl moiety. (5) A second sulfur atom is covalently attached to the thiooctanoyl molecule, (6) leading to formation of the mature lipoyl cofactor and further degradation of the Fe/S cluster. To enable multiple reaction cycles, the auxiliary cluster must be regenerated by a still unclear mechanism. In humans, the mature lipoyl cofactor is finally transferred to the target proteins, e.g., the E2 subunits of pyruvate (PDH) and α-ketoglutarate (KGDH) dehydrogenase complexes. BCKDH, branched-chain ketoacid dehydrogenase; OADH, 2-oxoadipate dehydrogenase3. b Time courses of 6-thiooctanoyl intermediate and lipoyl product formation in FDX1-catalyzed reactions (see Fig. 3b,c). Samples included 0.5 mM peptide substrate, 35 μM LIAS, 2 mM NADPH, 20 μM FDXR, FDX1 as indicated and 1 mM SAM. Formation of the 6-thiooctanoyl intermediate proceeded significantly faster than lipoyl formation, indicating the second sulfur insertion step to be rate-limiting under the experimental conditions. The result suggested to record the data of other experiments after 150 min incubation.

Extended data Figure 7 |. Differential growth complementation of human LIAS-containing Gal-YAH1-lip5Δ cells by human FDX1 and FDX2 reflects their distinct functions.

Gal-YAH1-lip5Δ yeast cells were transformed with a plasmid encoding human LIAS plus vectors containing no gene (−), FDX1 and/or FDX2 as indicated. a Cells were grown in liquid media for 4 days. Optical density (OD) at 600 nm was measured every 30 min. Growth in minimal lactate medium (SLac) is indicated by dashed lines, in rich yeast peptone lactate (YPLac) medium by solid lines. Grey dashed lines indicate standard errors (n = 4) using a microplate reader. b Serial dilutions of the indicated yeast strains were spotted onto agar plates containing minimal (S) or yeast peptone rich (YP) medium plus the indicated carbon sources. Plates were incubated at 30°C for 3 days. The growth results fit to distinct functions of human FDX1 and FDX2 in lipoylation/heme a synthesis and Fe/S protein biogenesis, respectively. Complementation of the LIAS-expressing Gal-YAH1-lip5Δ cells with FDX2 but not FDX1 supported growth due to Fe/S protein biogenesis restoration. The residual growth on non-fermentable carbon sources (lactate or glycerol) was due to the leaky GAL promoter allowing residual amounts of Yah1, and hence lipoate/heme a, being produced. Growth under these conditions was increased to normal levels by the combined expression of both human FDXs because FDX1 regenerated synthesis of both lipoate and heme a, and FDX2 supported Fe/S protein biogenesis.

Extended data Figure 8 |. Multi-sequence alignment of mitochondrial ferredoxins.

The multi-sequence alignment was generated by Multalin4. Secondary structure elements of the human FDX2 structure are shown above the alignment according to PROMOTIF5. Numbering is according to the full-length sequences of human (Hs) FDX1 and FDX2 retrieved from Uniprot (https://www.uniprot.org). The Fe/S cluster-coordinating cysteine residues are highlighted in yellow. Altered residues/regions of human FDX1 and FDX2 are highlighted in grey (see also Suppl. Table S3). Residues/regions mutated for interconversion of FDX1 and FDX2 functions (mutants M3, M5, M6, M7, R135E and C-terminal deletion/exchange) are additionally highlighted by colored boxes for animal FDX1/2-type sequences. Names of organisms are colored according to FDX-type: animal FDX2 (red), mitosomal (black), plant (green), fungal (orange), animal FDX1 (blue) and bacterial (grey). Two Trypanosoma brucei (Tb) FDXs best align between fungal and FDX1-type (FdxA) proteins or between FDX1-type and bacterial (FdxB) proteins6. FDXs from the following organisms were used (sequence identifiers in brackets): Homo sapiens (NP_001026904.2, NP_004100.1), Canis lupus familiaris (XP_038284595.1, XP_038367022.1), Bos taurus (NP_001073695.1, NP_851354.1), Rattus norvegicus (NP_001101472.1, NP_058822.2), Mus musculus (NP_001034913.1, NP_032022.1), Danio rerio (NP_001070132.1, XP_001922722.2), Drosophila melanogaster (NP_001189075.1, NP_647889.2), Encephalitozoon cuniculi GB-M1 (NP_585988.1), Trachipleistophora hominis OX=72359 GN=THOM_0371 PE=4 SV=1 (L7K0F4_TRAHO), Arabidopsis thaliana (NP_001329852.1), Populus alba (XP_034922198.1), Oryza sativa Japonica Group (XP_015647182.1), Chaetomium thermophilum var. thermophilum DSM 1495 (XP_006692961.1), Chaetomium globosum CBS 148.51 (XP_001225251.1), Neurospora crassa OR74A (XP_958085.1), Aspergillus fumigatus Af293 (XP_747954.1), Yarrowia lipolytica CLIB122 (XP_500417.1), Saccharomyces cerevisiae S288C (NP_015071.1), Schizosaccharomyces pombe Etp1fd (2WLB_A), Trypanosoma brucei brucei (XP_845713.1 and XP_844647.1), Magnetospirillum magnetotacticum (WP_009867486.1), Rhodospirillum rubrum (WP_200292119.1), Rickettsia prowazekii (WP_004595967.1), Yersinia pestis (WP_015683702.1), Shigella flexneri (EHF1065008.1), Salmonella enterica (WP_001124473.1).

Extended data Figure 9 |. Site-directed mutagenesis identifies FDX2 regions that functionally distinguish from FDX1.

Gal-YAH1 yeast cells were transformed with vectors expressing the indicated FDXs and variants (see Supplementary Table 5). Growth of serial cell dilutions on minimal medium (S) agar plates containing glucose or galactose was at 30°C for 3 days. FDX1-FDX2-discriminating regions critical for the in vivo function of human FDX2 were identified using FDX2 variants in which amino acids where exchanged to those of FDX1. A loss of cell growth identified the respective altered region as being important for FDX2 function. The broken lines separate independent plates.

Extended data Figure 10 |. Alphafold2 predicts a functionally meaningful structure for the trimeric LIAS-GCSH-FDX1 complex.

Structures of human LIAS, GCSH, and FDX1, and of complexes were predicted with Google Colab and the top-scoring prediction is displayed (https://colab.research.google.com/github/sokrypton/ColabFold/blob/main/beta/AlphaFold2_advanced.ipynb). a Overlay of the predicted LIAS structure (blue, residues: 29–372) with Mycobacterium tuberculosis LipA (PDB code: 5EXK, green). The Mt LipA catalytic (cat.) and auxiliary (aux.) cluster are displayed as spheres and its bound 6-thiooctanoyllysyl (thiooct) moiety as grey sticks. b-c Modeling of the LIAS-GCSH-FDX1 complex (residues: LIAS, 29–372; GCSH, 41–173; FDX1, 54–184) predicted a functionally meaningful complex, where GCSH inserts its lipoyl-carrying residue Lys107 into the octanoyl substrate entry tunnel of LIAS. The position of the [2Fe-2S] cluster of FDX1 is consistent with electron transfer to the catalytic [4Fe-4S] cluster of LIAS. Fe/S cluster-coordinating residues and GCSH Lys107 are shown as sticks. Positions of Fe/S clusters are modelled based on crystal structures of FDX1 (PDB code: 3P1M) and Mt LipA (PDB code: 5EXK). LIAS, blue; GCSH, grey; FDX1, gold. In (c) the electrostatic surface potential is mapped onto the half transparent surface of LIAS. When we instead modeled a trimeric LIAS-GCSH-FDX2 complex, binding of FDX2 was predicted at the substrate tunnel of LIAS. This would block substrate-product delivery by GCSH. GCSH interacted with FDX2, but hardly with LIAS in this case. Overall, no physiologically relevant complex could be modeled in presence of FDX2. d-f Electrostatic surfaces mapped onto LIAS (d), FDX1 (e) and GCSH (f). LIAS-FDX1 and LIAS-GCSH interacting regions are encircled by yellow and black dashed lines, respectively. The location of the FDX1 [2Fe-2S] cluster and helix F are encircled by yellow and light blue solid lines, respectively. Surface potentials were calculated using the APBS server (https://server.poissonboltzmann.org). Negative charges are colored in red, positive charges in blue. The color bar covers the range from −10 kT/e to +10 kT/e. N and C termini are indicated.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Ralf Rösser and Sahra Hanschke for excellent technical assistance, Dr. Uwe Linne and Jan Bamberger from the Core Facility ‘Mass spectrometry and Elemental analysis’ of Philipps-Universität Marburg for mass spectrometry, and Dr. Frank Hannemann and Rita Bernhardt (Saarbrücken) for help with cortisol formation assays. We acknowledge the contribution of the Core Facility ‘Protein Biochemistry and Spectroscopy’ of the Philipps-Universität Marburg. RL received generous financial support from Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (SPP 1927) and COST Action FeSBioNet (Contract CA15133). SJB acknowledges support from the National Science Foundation (MCB-1716686) and the Eberly Family Distinguished Chair in Science. SJB is an Investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

References

- 1.Campbell IJ, Bennett GN & Silberg JJ Evolutionary Relationships Between Low Potential Ferredoxin and Flavodoxin Electron Carriers. Frontiers in Energy Research 7(2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hanke G & Mulo P Plant type ferredoxins and ferredoxin-dependent metabolism. Plant Cell Environ 36, 1071–84 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miotto O et al. Genetic architecture of artemisinin-resistant Plasmodium falciparum. Nat Genet 47, 226–34 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Changmai P et al. Both human ferredoxins equally efficiently rescue ferredoxin deficiency in Trypanosoma brucei. Mol Microbiol 89, 135–51 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ewen KM, Ringle M & Bernhardt R Adrenodoxin--a versatile ferredoxin. IUBMB Life 64, 506–12 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sheftel AD et al. Humans possess two mitochondrial ferredoxins, Fdx1 and Fdx2, with distinct roles in steroidogenesis, heme, and Fe/S cluster biosynthesis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 107, 11775–80 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lange H, Kaut A, Kispal G & Lill R A mitochondrial ferredoxin is essential for biogenesis of cellular iron-sulfur proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 97, 1050–5 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shi Y, Ghosh M, Kovtunovych G, Crooks DR & Rouault TA Both human ferredoxins 1 and 2 and ferredoxin reductase are important for iron-sulfur cluster biogenesis. Biochimica et biophysica acta 1823, 484–92 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Webert H et al. Functional reconstitution of mitochondrial Fe/S cluster synthesis on Isu1 reveals the involvement of ferredoxin. Nat. Commun. 5, 5013 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Freibert SA et al. Evolutionary conservation and in vitro reconstitution of microsporidian iron-sulfur cluster biosynthesis. Nat Commun 8, 13932 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Braymer JJ, Freibert SA, Rakwalska-Bange M & Lill R Mechanistic concepts of iron-sulfur protein biogenesis in Biology. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Res 1868, 118863 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kispal G, Csere P, Prohl C & Lill R The mitochondrial proteins Atm1p and Nfs1p are essential for biogenesis of cytosolic Fe/S proteins. EMBO J 18, 3981–9 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boniecki MT, Freibert SA, Muhlenhoff U, Lill R & Cygler M Structure and functional dynamics of the mitochondrial Fe/S cluster synthesis complex. Nat Commun 8, 1287 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van Vranken JG et al. The mitochondrial acyl carrier protein (ACP) coordinates mitochondrial fatty acid synthesis with iron sulfur cluster biogenesis. Elife 5, e17828 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim JH, Frederick RO, Reinen NM, Troupis AT & Markley JL [2Fe-2S]-Ferredoxin binds directly to cysteine desulfurase and supplies an electron for iron-sulfur cluster assembly but is displaced by the scaffold protein or bacterial frataxin. Journal of the American Chemical Society 135, 8117–20 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gervason S et al. Physiologically relevant reconstitution of iron-sulfur cluster biosynthesis uncovers persulfide-processing functions of ferredoxin-2 and frataxin. Nat Commun 10, 3566 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Freibert SA et al. N-terminal tyrosine of ISCU2 triggers [2Fe-2S] cluster synthesis by ISCU2 dimerization. Nat Commun 12, 6902 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weiler BD et al. Mitochondrial [4Fe-4S] protein assembly involves reductive [2Fe-2S] cluster fusion on ISCA1-ISCA2 by electron flow from ferredoxin FDX2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 117, 20555–20565 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spiegel R et al. Deleterious mutation in FDX1L gene is associated with a novel mitochondrial muscle myopathy. Eur J Hum Genet 22, 902–6 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Paul A et al. FDXR Mutations Cause Sensorial Neuropathies and Expand the Spectrum of Mitochondrial Fe-S-Synthesis Diseases. Am J Hum Genet 101, 630–637 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gurgel-Giannetti J et al. A novel complex neurological phenotype due to a homozygousmutation in FDX2. Brain 141, 2289–2298 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lill R & Freibert SA Mechanisms of Mitochondrial Iron-Sulfur Protein Biogenesis. Annu Rev Biochem 89, 471–499 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang Y et al. Ferredoxin reductase is critical for p53-dependent tumor suppression via iron regulatory protein 2. Genes Dev 31, 1243–1256 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barros MH, Carlson CG, Glerum DM & Tzagoloff A Involvement of mitochondrial ferredoxin and Cox15p in hydroxylation of heme O. FEBS Lett 492, 133–8 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bareth B et al. The heme a synthase Cox15 associates with cytochrome c oxidase assembly intermediates during Cox1 maturation. Mol Cell Biol 33, 4128–37 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Swenson SA et al. From Synthesis to Utilization: The Ins and Outs of Mitochondrial Heme. Cells 9(2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pierrel F et al. Involvement of mitochondrial ferredoxin and para-aminobenzoic acid in yeast coenzyme Q biosynthesis. Chem Biol 17, 449–59 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ozeir M et al. Coenzyme Q biosynthesis: Coq6 is required for the C5-hydroxylation reaction and substrate analogs rescue Coq6 deficiency. Chemistry & biology 18, 1134–42 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yan R, Adinolfi S & Pastore A Ferredoxin, in conjunction with NADPH and ferredoxin-NADP reductase, transfers electrons to the IscS/IscU complex to promote iron-sulfur cluster assembly. Biochim Biophys Acta 1854, 1113–7 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cai K, Tonelli M, Frederick RO & Markley JL Human Mitochondrial Ferredoxin 1 (FDX1) and Ferredoxin 2 (FDX2) Both Bind Cysteine Desulfurase and Donate Electrons for Iron-Sulfur Cluster Biosynthesis. Biochemistry 56, 487–499 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhu J & Thompson CB Metabolic regulation of cell growth and proliferation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 20, 436–450 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tsvetkov P et al. Mitochondrial metabolism promotes adaptation to proteotoxic stress. Nat Chem Biol 15, 681–689 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tsvetkov P et al. Copper induces cell death by targeting lipoylated TCA cycle proteins. Science 375, 1254–1261 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Campbell IJ et al. Recombination of 2Fe-2S Ferredoxins Reveals Differences in the Inheritance of Thermostability and Midpoint Potential. ACS Synth Biol 9, 3245–3253 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brown KR, Allan BM, Do P & Hegg EL Identification of novel hemes generated by heme A synthase: evidence for two successive monooxygenase reactions. Biochemistry 41, 10906–13 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moraes CT, Diaz F & Barrientos A Defects in the biosynthesis of mitochondrial heme c and heme a in yeast and mammals. Biochim Biophys Acta 1659, 153–9 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Antonicka H et al. Mutations in COX15 produce a defect in the mitochondrial heme biosynthetic pathway, causing early-onset fatal hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Am J Hum Genet 72, 101–14 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sheftel AD et al. The human mitochondrial ISCA1, ISCA2, and IBA57 proteins are required for [4Fe-4S] protein maturation. Mol Biol Cell 23, 1157–66 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cronan JE Assembly of Lipoic Acid on Its Cognate Enzymes: an Extraordinary and Essential Biosynthetic Pathway. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 80, 429–50 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McCarthy EL & Booker SJ Destruction and reformation of an iron-sulfur cluster during catalysis by lipoyl synthase. Science 358, 373–377 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Landgraf BJ, McCarthy EL & Booker SJ Radical S-Adenosylmethionine Enzymes in Human Health and Disease. Annu Rev Biochem 85, 485–514 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nagai M et al. The oncology drug elesclomol selectively transports copper to the mitochondria to induce oxidative stress in cancer cells. Free Radic Biol Med 52, 2142–50 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Soma S et al. Elesclomol restores mitochondrial function in genetic models of copper deficiency. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 115, 8161–8166 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hasinoff BB, Yadav AA, Patel D & Wu X The cytotoxicity of the anticancer drug elesclomol is due to oxidative stress indirectly mediated through its complex with Cu(II). J Inorg Biochem 137, 22–30 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Modica-Napolitano JS, Bharath LP, Hanlon AJ & Hurley LD The Anticancer Agent Elesclomol Has Direct Effects on Mitochondrial Bioenergetic Function in Isolated Mammalian Mitochondria. Biomolecules 9(2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]