Abstract

Papillary thyroid cancer (PTC) is a prevalent kind of thyroid cancer (TC), with the risk of metastasis increasing faster than any other malignancy. So, understanding the role of PTC in pathogenesis requires studying the various gene expressions to find out which particular molecular biomarkers will be helpful. The authors conducted a comprehensive search on the PubMed microarray database and a meta-analysis approach on the remaining ones to determine the differentially expressed genes between PTC and normal tissues, along with the analyses of overall survival (OS) and recurrence-free survival (RFS) rates in patients with PTC. We considered the associated genes with MAPK, Wnt, and Notch signaling pathways. Two GEO datasets have been included in this research, considering inclusion and exclusion criteria. Nineteen genes were found to have higher differences through the meta-analysis procedure. Among them, ten genes were upregulated, and nine genes were downregulated. The expression of 19 genes was examined using the GEPIA2 database, and the Kaplan-Meier plot statistics were used to analyze RFS and the OS rates. We discovered seven significant genes with the validation: PRICKLE1, KIT, RPS6KA5, GADD45B, FGFR2, FGF7, and DTX4. To further explain these findings, it was discovered that the mRNA expression levels of these seven genes and the remaining 12 genes were shown to be substantially linked with the results of the experimental literature investigations on the PTC. Our research found nineteen panels of genes that could be involved in the PTC progression and metastasis and the immune system infiltration of these cancers.

Keywords: Signaling pathway, Papillary thyroid cancer (PTC), Gene biomarker, MAPK, NOTCH, Wnt, Systems biology, Bioinformatics, Meta-analysis

Highlights

-

•

The associated genes with MAPK, Wnt, and Notch signaling pathways were considered.

-

•

Nineteen genes were found to have higher differences through the meta-analysis procedure.

-

•

Seven significant genes were PRICKLE1, KIT, RPS6KA5, GADD45B, FGFR2, FGF7, and DTX4.

-

•

Nineteen panels of genes could be involved in the PTC progression and metastasis and the immune system infiltration of these cancers based on corresponding analyses.

Abbreviations:

- ANOVA

One-way analysis of variance

- AP-1

Activator protein 1

- ATC

Anaplastic thyroid carcinoma

- BLBC

Basal-like breast cancer

- CCND1

Cyclin D1

- CTNNB1

Catenin beta 1

- DTX4

Deltex E3 ubiquitin ligase 4

- DUSP

Dual specificity phosphatase

- EGFR

Epidermal growth factor receptor

- ERBB3

Erb-b2 receptor tyrosine kinase 3

- ERK

Extracellular signal-regulated kinase

- FDR

False discovery rate

- FGF7

Fibroblast growth factor 7

- FGFR2

Fibroblast growth factor receptor 2

- FTC

Follicular thyroid carcinoma

- GADD45B

Growth arrest and DNA damage-inducible beta

- GEO

Gene expression omnibus

- GEPIA2

Gene expression profiling interactive analysis v.2

- IGF2

Insulin-like growth factor 2

- IL1RAP

Interleukin 1 receptor accessory protein

- Jag

Jagged

- JNK

c-Jun N-terminal kinases

- HSPA1B

Heat shock protein family A (Hsp70) member 1B

- KEGG

Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes

- KIT

c-KIT

- KM

Kaplan-Meier

- LEF/TCF

Lymphoid enhancer factor/T cell factor

- MAPK

Mitogen-activated protein kinase

- MTC

Medullary thyroid carcinoma

- NCBI

National center for biotechnology information

- OS

Overall survival

- PDGF

Platelet-derived growth factor

- PTC

Papillary thyroid cancer

- qRT-PCR

Quantitative reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction

- RFS

Recurrence/disease/relapse-free survival

- RPS6KA5

Ribosomal protein S6 kinase A5

- RT-PCR

Real time polymerase chain reaction

- MAPK13

Mitogen-activated protein kinase 13

- RAC2

Ras-related C3 botulinum toxin substrate 2

- PRICKLE1

Prickle homolog 1

- TC

Thyroid cancer

- TCF7L1

Transcription Factor 7-Like 1

- TCGA

The cancer genome atlas

- TNF

Tumor necrosis factor

- HEY2

Hairy/enhancer-of-split related with YRPW motif protein 2

1. Background

Thyroid cancer (TC) is the most common endocrine malignancy, ranking 9th with 586,000 cases globally; it has received increased attention in recent decades due to its rising incidence rate in many countries [[1], [2], [3]]. TC is usually associated with several significant risk factors, including age, specific genetic abnormalities, gender, environmental conditions, and lifestyle [4,5]. Medullary thyroid carcinoma (MTC), follicular thyroid carcinoma (FTC), anaplastic thyroid carcinoma (ATC), and papillary thyroid carcinoma (PTC) are some of the histological forms of TC [6]. PTC has the highest rate of occurrence among these groups, contributing to more than 80 % of all TC cases, with incidence and mortality of 3.1 % and 0.4 %, respectively. Eastern Asia, Australia/New Zealand, Northern America, and Micronesia/Polynesia have the highest national incidence rates, according to the GLOBOCAN 2020 statistics [3].

Because most patients of PTC have a better condition following multiple therapies such as chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and surgical resection, lymph node metastasis and local relapse are still common in PTC patients, causing increased mortality [[7], [8], [9]]. Despite enormous achievements in the PTC prognosis, a discrepancy exists in the knowledge of the disease's molecular and functional processes and the involved signaling pathways [10]. The development of the PTC has recently demonstrated the involvement of corresponding genes of the mTOR and PI3K signaling pathways [11,12]. According to the findings, Three gene biomarkers were downregulated in this disorder. So, the low levels of expression of these genes may be helpful in drug development and delivery systems in PTC patients. In the present study, the authors have been encouraged to research the role of other critical signaling pathways, including Wnt, MAPK, and Notch, in PTC development. The Wnt/β-catenin is a well-known pathway linked to some essential cell functions [13,14]. This pathway is involved in initiating and progressing some different malignant tumors.

Moreover, it is activated in several human cancers, and this activation contributes to tumor growth and recurrence by regulating cancer cell proliferation, apoptosis, and the epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) processes [[15], [16], [17]]. This pathway's activation promotes tumor cell migration and invasion [18]. Mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) is another pathway that the genetic changes in its signaling components such as RET/PTC, RAS, and BRAF have been well explored in the PTC and lead to constitutive MAPK signaling pathway activation [[19], [20], [21], [22]]. Targeted expression of the RET/PTC or BRAFT1799A oncogenes in transgenic mice showed that they are involved in the TC, indicating mutations in MAPK signaling components contribute to PTC development [23,24]. The notch signaling pathway is needed for tissue homeostasis development and maintenance [25]. The Notch signaling pathway currently consists of four mammalian receptors and at least five ligands. A large-scale gene expression study in the PTC revealed many Notch signaling components [26].

Since cancers are categorized as complex diseases, and the PTC is not an exception, we have studied three signaling pathways (Notch, Wnt, and MAPK) and their corresponding genes to expound further on the critical roles of significant genes between the PTC and normal tissues. To satisfy the research aim, we have systematically searched the National Center for Biotechnology Information-Gene Expression Omnibus (NCBI-GEO) database to extract the potential GEO microarray datasets by excluding non-relevant datasets from further analysis. Finally, as mentioned above, the selected datasets were the target for the meta-analysis approach to determine the essential biomarkers affecting the signaling pathways. The determined differentially expressed genes will also be analyzed for different survival rates and validity through the literature's experiments.

2. Methods

2.1. Data sources and search strategies

The publicly available microarray database (i.e., NCBI-GEO) was selected for the thorough search using a Boolean query to satisfy the research aim. General terms employed in the query included either "papillary thyroid cancer" or PTC. Several inclusion and exclusion criteria were considered to filter out the search results obtained from the NCBI-GEO database. The remained GEO datasets, in terms of the webpage contents and their corresponding published articles, should provide those extracted from tumor tissue of Homo sapiens organism and with experiment type of "Expression profiling by array" by including both normal and cancer mRNA samples. Additionally, all platform types were included for not losing any potential datasets. Finally, the GEO datasets considering the inclusion criteria were used to study the Wnt, MAPK, and Notch signaling pathways through meta-analysis.

2.2. Identification of potential common genes

The list of genes involved in Wnt (hsa04310), MAPK (hsa04010), and Notch (hsa04330) signaling pathways was available online in The Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) database. Then, the associated genes of the three signaling pathways mentioned above were the targets for the input for the meta-analysis procedure.

2.3. Meta-analysis approach

We used the meta-analysis tool for gene expression datasets, ExAtlas (i.e., http://alexei.nfshost.com/exatlas/) for performing multi-platform of GEO datasets [27]. The main characteristics of the ExAtlas used for the GEO datasets, including only the gene expressions of Wnt, MAPK, and Notch signaling pathways complying with the inclusion criteria, were based on random-effects model (because of heterogeneous GEO microarray datasets), z-score as well as Fisher's methodologies. Before performing the meta-analysis approach, all GEO datasets were log2 transformed, quantile normalized and analyzed through t-test one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). The standard deviation values of less than 0.3, the false discovery rate (FDR) of 0.05, and the fold change of 2 were the criteria for inspecting the quality of gene expression datasets and the meta-analysis procedure, respectively.

2.4. Post-processing approaches

Generally, the analysis of the survival rates, through plotting the Kaplan-Meier (KM) estimate, comprised statistical interpretation of clinical or experimental data and the follow-up time of about five years where the health status of the patients is of interest in terms of mortality or recurrence rates. We used the Gene Expression Profiling Interactive Analysis v.2 (GEPIA2) (http://gepia2.cancer-pku.cn/#index) free tool to obtain both overall survival (OS) and relapse-free survival (RFS) rates using The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA)-THCA database where the number of samples for the TC and control were 512 and n = 59, respectively [28,29]. The default values for the p-value and confidence interval of the hazard ratio were 0.05 and 95 %, respectively.

The National Cancer Institute's Clinical Proteomic Tumor Analysis Consortium (CPTAC) and PanCanAtlas (version 20190101) provided molecular and clinical information on 11263 individuals with 33 different kinds of cancer to be utilized in CVCDAP's release 2019 [30]. Using CVCDAP, researchers may easily construct a virtual cohort using samples from a single study or a collection of studies with similar molecular or clinical features. A virtual group may be created using any combination of tissue, clinical, and molecular characteristics. These may include disease type, disease stage, age, somatic mutations, and degree of mRNA or protein expression, to mention a few. It is possible to store cohorts with another saved set to perform operations such as union, intersection, or subtraction. CVCDAP's enhanced characteristics may make it possible to identify molecular processes underlying biological or clinical topics of interest much more quickly than possible. We used the multivariate Cox regression tool from CVCDAP to investigate the possible correlations between significant genes and the union of BRAF-, KRAS-, HRAS-, and NRAS-like mutations based on hazard ratio measurement.

It is customary to create risk categories using the prognostic index (PI), often known as the "risk score." As the Cox model's linear component, the PI is denoted by the equation PI = b1x1+b2x2+ … +bpxp, where xi is the gene expression value and bi, the risk coefficient, is derived via the Cox fitting computational procedure. To calculate the b coefficients, we used the SurvExpress web server tool [31]. The Cox model includes all imported genes in a single model to create risk categories regarding the concordance index.

The TCGA thyroid carcinoma study (TCGA-THCA) data was collected from 507 patients with papillary thyroid cancer (PTC) and 59 controls. Further investigation of significant DEGs in Firebrowse (http://firebrowse.org) was based on identifying associations between the level 3 mRNA sequencing data and clinical information (i.e., extrathyroidal extension(ETE) and tumor TNM stages) [32]. The False Discovery Rate (FDR) counterpart of the P-value is the Q value for multiple hypothesis correction, defined as the lowest FDR at which the test may be considered significant [33]. The website utilized R's 'p.adjust' function using the 'Benjamini and Hochberg' technique to get Q values from P values.

3. Results

3.1. Identified GEO datasets through a systematic review

The workflow of systematically querying GEO datasets and GEO profiles is depicted in Fig. 1, along with the reasons for including and excluding a specific GEO dataset. The search procedure identified 1916 items, of which 323 non-Homo sapiens datasets and 1831 datasets using other profiling platforms were excluded (a total of 1865). After carefully inspecting the contents of 51 GEO datasets, 47 were from different sources. Samples types (i.e., non-mRNA), the microarray data for four remaining GEO datasets (viz., GSE29265, GSE97001, GSE3678, and GSE138198 with a total of 34 healthy and 37 PTC samples) were downloaded for further analysis and quality check before the meta-analysis procedure.

Fig. 1.

The flow chart diagram for systematic search and determined eligible GEO datasets.

3.2. Meta-analysis outcomes

Before importing the GEO datasets in the ExAtlas website, the in-common genes between the GEO datasets and the genes associated with three signaling pathways separately will result in the identification of significant differentially expressed genes of 59 genes related to the Notch signaling pathway, 166 genes related to Wnt signaling pathway, and 294 genes associated with MAPK signaling pathway between two tissue types. The initial quality control of the samples showed that they passed the first assessment stage of GEO datasets; after performing the meta-analysis procedure on the two GEO datasets for three signaling pathways, various numbers of genes were differentially expressed, employing the p-value and FDR measurements.

3.3. Identification of DEGs in notch, MAPK, and Wnt signaling pathways

For the Notch signaling pathway, two upregulated genes deltex E3 ubiquitin ligase 4 (DTX4, p-value = 8.53E-10) and hes-related family bHLH transcription factor with YRPW motif 2 (HEY2, p-value = 0.000745) were identified. Furthermore, for the Wnt signaling pathway, two upregulated Cyclin D1 (CCND1, p-value = 0) and prickle homolog 1 (PRICKLE1, p-value = 3.91E-07) as well as one downregulated gene including transcription factor 7-like 1, (TCF7L1, p-value = 9.22E-07) was identified. Finally, for the MAPK signaling pathway, six upregulated and eight downregulated significant genes were found, and the details are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Differentially expressed genes were identified through a meta-analysis between the PTC and healthy samples for Notch, Wnt, and MAPK signaling pathways.

| No | Signaling pathway | Gene symbol | Fold Change | p-value | FDR | Current study | Literature evidence | Methods | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Notch | DTX4 | 3.886 | 8.53E-10 | 4.01E-08 | Up | Up | ●RT-qPCR | [34] |

| 2 | HEY2 | 5.767 | 0.000745 | 0.0175 | Up | Up | ●Immunocytochemistry ●Western blot |

[35] | |

| Up | ●In silico | [36] | |||||||

| 3 | Wnt | CCND1 | 2.672 | 0 | 0 | Up | Up | ●In silico | [37] |

| Up | ●RT-qPCR | [38] | |||||||

| 4 | PRICKLE1 | 2.349 | 3.91E-07 | 2.36E-05 | Up | Not stated | ●Immunocytochemistry ●qRT-PCR |

[39] | |

| Not stated | ●In silico | [40] | |||||||

| 5 | TCF7L1 | 2.305 | 2.305 | 2.305 | Down | Down | ●Immunocytochemistry ●Western blot |

[35] | |

| Down | ●In silico | [41] | |||||||

| 6 | MAPK | IL1RAP | 4.176 | 3.48e-12 | 1.68e-10 | Up | Up | ●RT-qPCR | [34] |

| Up | ●NanoString ●RNA-sequencing |

[42] | |||||||

| 7 | DUSP4 | 4.167 | 0 | 0 | Up | Up | ●RT-qPCR | [43] | |

| Up | ●PCR | [44] | |||||||

| Up | ●qRT-PCR | [45] | |||||||

| 8 | RAC2 | 2.466 | 0.000957 | 0.0163 | Up | Down | ●qRT-PCR ●In silico |

[46] | |

| Up | ●FISH and RT-PCR ●In silico |

[47] | |||||||

| 9 | ERBB3 | 3.192 | 4.92E-09 | 1.82E-07 | Up | Up | ●RT-qPCR | [48] | |

| 10 | MAPK13 | 2.044 | 2.19E-07 | 6.07E-06 | Up | Up | ●In silico | [49] | |

| 11 | DUSP5 | 2.659 | 2.95e-05 | 0.000536 | Up | Up | ●qRT-PCR | [45] | |

| 12 | KIT | 6.835 | 4.72E-08 | 1.50E-06 | Down | Down | ●Immunocytochemistry | [50] | |

| Up | ●Immunocytochemistry | [51] | |||||||

| Down | ●NanoString nCounter | [52] | |||||||

| 13 | PDGFRA | 3.459 | 1.65E-06 | 4.08E-05 | Down | Up | ●cDNA microarray analysis ●Western blot |

[53] | |

| Up | ●TaqMan qRT-PCR ●Microarray hybridization |

[54] | |||||||

| Up | ●Western blot | [55] | |||||||

| Down | ●miRNA microarray analysis | [56] | |||||||

| Up | ●Immunohistochemistry | [57] | |||||||

| 14 | IGF2 | 3.112 | 0.000101 | 0.001862 | Down | Down | ●Microarray analysis ●RT-PCR |

[58] | |

| 15 | RPS6KA5 | 2.074 | 6.99E-06 | 0.000155 | Down | Down | ●Western blot ●qRT-PCR |

[59] | |

| 16 | GADD45B | 2.47 | 3.75E-13 | 1.67E-11 | Down | Down | ●qRT-PCR | [60] | |

| 17 | HSPA1B | 2.308 | 1.71E-05 | 0.000345 | Down | Down/Up | ●Review of Cancers | [61] | |

| 18 | FGFR2 | 2.122 | 1.82E-14 | 1.01E-12 | Down | Down | ●qRT-PCR ●Western blot |

[62] | |

| 19 | FGF7 | 2.556 | 0.003146 | 0.0499 | Down | Down | ●miRNA microarray analysis | [56] |

3.4. Post-processing outcomes

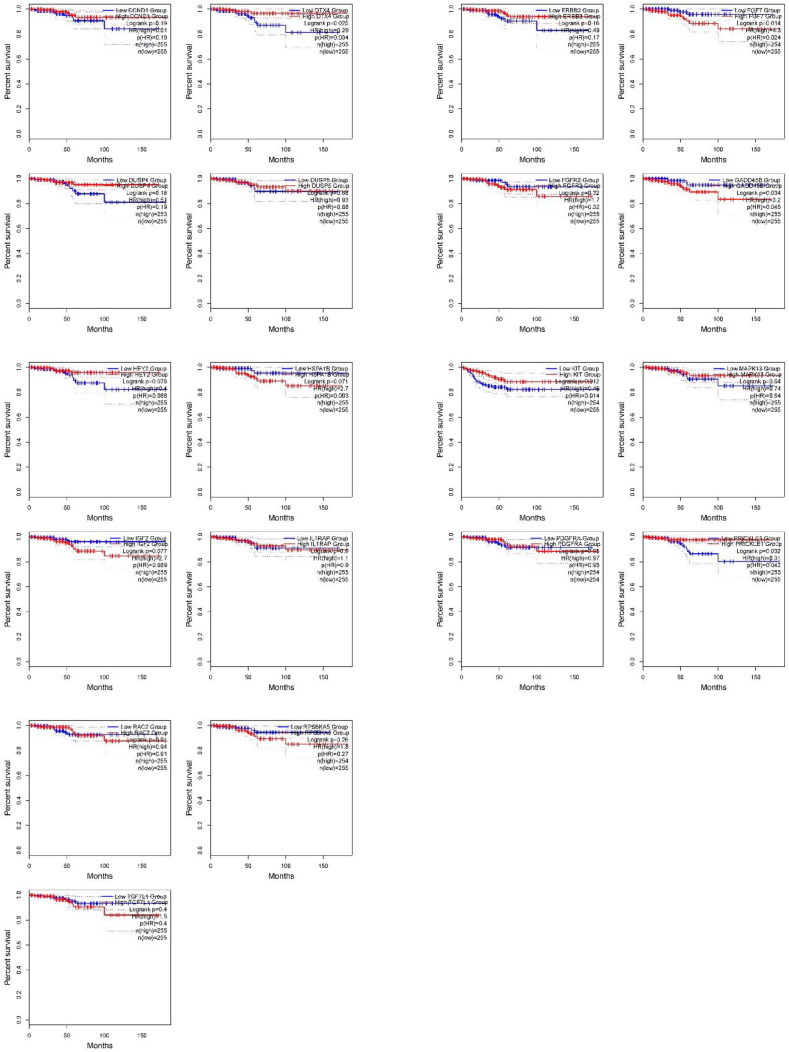

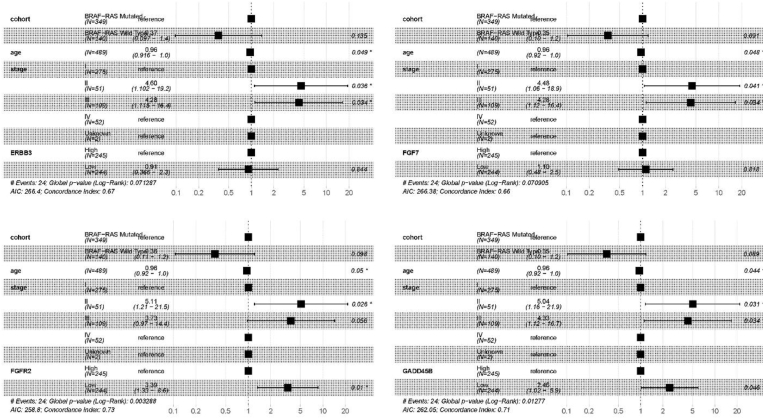

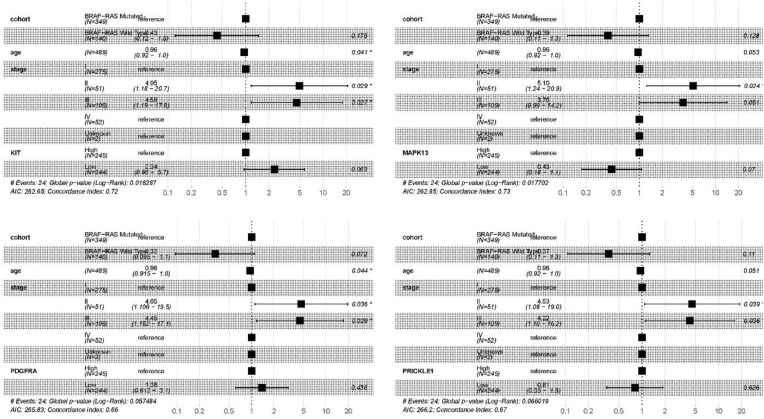

The OS and RFS analyses identified two upregulated and five downregulated genes, as illustrated in Fig. 2, Fig. 3. Among upregulated genes, PRICKLE1 and DTX4 were differentially expressed in OS rate with p-values 0.032 and 0.025, respectively. Moreover, by considering the downregulated genes, three genes growth arrest and DNA damage-inducible beta, protein kinase C alpha, and fibroblast growth factor 7 (i.e., GADD45B, p-value = 0.034; KIT, p-value = 0.012; FGF7, p-value = 0.014) were found to be significant in terms of OS rate; however, four genes c-KIT (KIT, p-value = 0.012), ribosomal protein S6 kinase A5 (RPS6KA5, p-value = 0.026), GADD45B (p-value = 0.025), and fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 (FGFR2, p-value = 0.029) were significant in terms of RFS rate.

Fig. 2.

KM plots of the OS results obtained from the identified genes involved in the PTC.

Fig. 3.

KM plots of the RFS results obtained from the identified genes involved in the PTC.

V-RAF murine sarcoma viral oncogene homolog B1 (BRAF) and rat sarcoma (RAS), specifically KRAS, NRAS, and HRAS, are essential for DNA repair or damage mutations in BRAF-like or RAS-like mutations across various cancers. The oncoplot tool of CVCDAP identified that thyroid cancer (THCA) has the mutation frequency for BRAF (59 %) and RAS (12 %), with patients harboring BRAF/RAS mutations (Fig. 4). Hence, the clinical implications of BRAF and the clinical significance of RAS mutations are important. Thus, we utilized CVCDAP to perform a multivariate Cox analysis of THCA patients using a union cohort of BRAF, HRAS, KRAS, and NRAS mutations. The results demonstrated a significant association with disease-free interval (DFI), as shown in Fig. 5. After adjusting for age and stages II and III, the association analyses were also carried out, and p-values less than 0.05 were statistically significant. The outcomes indicate almost substantial correlations among the cohort of BRAF/RAS mutations and age and stages without considering the obtained DEGs. Besides, the downregulation of GADD45B and FGFR2 directly correlates with the united cohort of BRAF/RAS mutations (p-value = 0.046 and 0.01, respectively). However, the correlation between age and BRAF/RAS mutations is insignificant for IGF2, IL1RAP, and PRICKLE1.

Fig. 4.

Frequency of BRAF-like and RAS-like mutations in TCGA-THCA using CVCDAP oncoplot tool.

Fig. 5.

Forest presentation of the 19 identified genes involved in the PTC correlated with clinical attributes (i.e., age and cancer stage) regarding the hazard ratio.

According to Table 2, fifteen out of nineteen DEGs were significant in extrathyroidal extension. Moreover, considering the pathological TNM stages of tumors, three, four, and none of the DEGs were identified as statistically significant for T, N, and M tumor stages.

Table 2.

Associations of identified DEGs with extrathyroidal extension and tumor pathological TNM stages with significant Q values less than 0.3 (in green color).

| Gene Symbol | PATHOLOGY_T_STAGE (Q) | PATHOLOGY_N_STAGE (Q) | PATHOLOGY_M_STAGE (Q) | EXTRATHYROIDAL_EXTENSION (Q) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| KIT | 0.000901 | 3.08E-05 | 0.876 | 0.000897 |

| PDGFRA | 0.461 | 6.48E-05 | 0.879 | 0.000433 |

| IGF2 | 0.224 | 0.00716 | 1 | 0.00329 |

| FGF7 | 0.424 | 0.688 | 0.501 | 0.523 |

| GADD45B | 0.219 | 0.895 | 0.761 | 0.681 |

| HSPA1B | 0.139 | 0.108 | 0.769 | 0.0102 |

| FGFR2 | 0.00104 | 0.00383 | 0.692 | 0.000726 |

| RPS6KA5 | 0.00969 | 0.392 | 0.559 | 0.0794 |

| IL1RAP | 0.0365 | 3.30E-09 | 0.905 | 0.000471 |

| DUSP5 | 0.00111 | 5.79E-10 | 0.886 | 5.59E-06 |

| ERBB3 | 3.66E-05 | 1.47E-11 | 0.927 | 4.29E-07 |

| DUSP4 | 0.00885 | 4.31E-06 | 0.777 | 0.00287 |

| RAC2 | 0.256 | 4.17E-07 | 0.695 | 0.00791 |

| MAPK13 | 0.00367 | 0.000264 | 0.607 | 5.04E-06 |

| TCF7L1 | 0.00014 | 4.27E-08 | 0.996 | 1.36E-06 |

| CCND1 | 0.346 | 0.549 | 0.992 | 0.351 |

| PRICKLE1 | 0.0953 | 1.31E-07 | 0.9 | 0.00273 |

| HEY2 | 0.671 | 0.0063 | 0.663 | 0.623 |

| DTX4 | 0.163 | 2.68E-06 | 0.925 | 0.000507 |

The findings indicate that these biomarkers (19 differentially expressed genes among four datasets) can distinguish between groups of people at risk due to variations in their gene expression levels. Despite this, the p-value of the risk group separation and the concordance index were all statistically significant and higher (CI > 0.5) for these biomarkers (i.e., CI = 0.781, p-value = 0.0169554). The risk model formula (1) based on high and low-risk categories for nineteen DEGs is shown below:

| (1) |

4. Discussion

The detailed information on the Notch, Wnt, and MAPK signaling pathways involved in the PTC at the cellular level and their corresponding identified genes are displayed in Fig. 6. Additionally, 19 significant gene biomarkers are comprehensively discussed regarding their critical roles, and gene crosstalks according to the three signaling pathways are provided in the following subsections. The required practical information and data are gathered to further validate these genes by quantitatively measuring the target gene expression levels (see Table 1 for more details).

Fig. 6.

Schematic illustration of the main signaling pathways and the associated significant genes involved in the PTC at the cellular level. The downregulated and upregulated genes are presented in red and green colors. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

4.1. Notch signaling pathway

Only one gene (DTX4) was important in the Notch signaling pathway. It is described that five Dx-related proteins containing highly conserved C-terminal E3 ubiquitin ligase and interacting with the Notch signaling pathway in mammalians include DTX1, DTX2, DTX3, DTX3L, DTX4, among which, DTX3 and DTX3L don't have the N terminus region [63,64]. The DTX4, a membrane-associated positive regulator of Notch signaling, involves early Notch activation and ubiquitylation [63]. Zhang, Liu, Li, Peng, Li and Li [34] considered the critical role of DTX4 upregulation. A computational approach was conducted on microarray datasets of PTC samples, and finally, the significant genes were validated through experimental tests.

Researchers utilized the PockDrug-Server in conjunction with the PPI network to find genes that may target thyroid cancer therapy. They searched TCGA thyroid cancer mRNA profiles and DNA methylation levels. Three genes, HEY2, TNIK, and LRP4, were selected for further analysis, considering the interactions with significant hub genes. This mechanism, when engaged, slows the spread of medullary thyroid carcinoma by targeting HEY2. To conclude, HEY2, TNIK, and LRP4 may have a role in developing thyroid cancer [36]. Thyroid tumors had an increased level of the NOTCH downstream effectors HEY2, identified as PROX1 negative regulators [65], with HEY2 showing combined statistical significance. Previous investigations have shown that the NOTCH pathway is active in thyroid malignancies [[66], [67], [68], [69]], supporting our result. Earlier experiments using thyroid gene expression profiling have shown a valid increase in HEY2 expression. Also, the qRT-PCR has confirmed that the HEY2 gene was overexpressed in the clinical samples.

4.2. Wnt signaling pathway

We identified four critical genes for the Wnt signaling pathway, including CCND1, TCF7L1, SFRP1, and SERPINF1. Among various proteins involved in the cell cycle process, the cyclin family is a highly conserved protein whose levels fluctuate rapidly in the four phases: G1, S, G2, and M. In these family members, the overexpression of CCND1 plays a functional role in the initiation and development of various human cancers and tumorigenesis via encoding the CCND1 protein [[70], [71], [72]], and the Involvement of oncogenes including CCND1 and catenin beta 1 (CTNNB1) has been well evidenced in the PTC [37,71]. Lymphoid enhancer factor/T cell factor (LEF/TCF), as a group of transcription factor proteins, binds specifically and highly to conserved regions of DNA. TCF7L1, a well-known member of the LEF/TCF family interacting with the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway, is associated with poor prognosis by overexpression in some high-grade cancers such as breast and colorectal [73]. In the case of PTC, Ray et al. [41] and Choi et al. [35] concluded that TCF7L1 had been strongly downregulated in tumor tissues.

PRICKLE1, a candidate gene expected to regulate PTC pathogenesis, was active in a recent study. Two genes, CCND1 and PRICKLE1, have been linked to PTC via strong correlation coefficients [40]. A key molecule in the Wnt signaling pathway is PRICKLE1, which regulates the proliferation and migration of tumor cells [[74], [75], [76], [77]]. Additionally, qRT-PCR and immunohistochemistry (IHC) showed that PRICKLE1 was overexpressed in PTC samples.

4.3. MAPK signaling pathway

The 19 genes have been determined to be critical in the MAPK signaling pathway. Interleukin 1 receptor accessory protein (IL1RAP) or IL1R3, as a co-receptor of IL1R1, plays a vital role in the transmission function of IL-1 signaling and is accounted as a biomarker for chronic myeloid leukemia stem cells [78]. Although IL1RAP has not been labeled for the biomarkers list in the TC, its involvement in acute myelogenous leukemia stem cells is reported elsewhere [78]. However, the significant upregulation of IL1RAP gene expression level in PTC disease has been identified in several reports [34,42,79].

It has been reported that dual-specificity phosphatase (DUSP) proteins mitigate the extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) pathway with a slow growth rate in the PTC. In this way, DUSP4, known as MAPK phosphatase two, induces a nuclear phosphatase in regulating cell proliferation and differentiation by suppressing ERK1/2, P38, and c-Jun N-terminal kinases (JNK). In other types of cancers, such as breast, glioma, and lung, the dysregulation of DUSP4 is associated with carcinogenesis [80]. In the case of PTC disease, elevated expression of DUSP4 has been previously studied. For example, Delys et al. [45], Lee et al. [44], and Ma et al. [43] concluded that DUSP4, a PTC biomarker, is an upregulated gene. DUSP5 is also the target of interest among DUSP proteins for the scientific cancer community. DUSP5 is one of the most critical genes with a high rate prognosis in patients with paclitaxel resistance to basal-like breast cancer (BLBC). Only Delys et al. [45] reported that the expression level of DUSP5 has been significantly increased among other differentially expressed genes.

Erb-b2 receptor tyrosine kinase 3 (ERBB3), sometimes referred to as the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), is one of the four members in the ERBB family, and its role has not been well studied in human-related cancers [81]. Several reports have evidenced overexpression of ERBB3 in PTC that has also been confirmed independently by the TCGA database [48,82,83]. Moreover, the Involvement of ERBB3 overexpression in thyroid cancer in those significantly mutated by BRAFV600E showed treatment resistance with its corresponding inhibitors (for example, RAF/MEK) [84]. Previous studies investigated the role of c-KIT (KIT) or CD117 as a transmembrane tyrosine kinase receptor in the PTC [[50], [51], [52]]. It has been shown that downregulation of the c-KIT receptor is related to developing malignant tumors through activation of the signal transduction cascades using immunocytochemical tests [50].

For over two decades, the platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGF) family consisting of four polypeptide ligands, i.e., PDGFA, B, C, and D, has been frequently investigated [54]. In a publication reported by Chen et al. [53], the authors concluded that PDGFA and PDGFRA are upregulated in both FTC and PTC cell lines, suggesting a crucial role of PDGFA in thyroid cell carcinogenesis. In another study, the authors have proposed clinical evidence for the downregulation of PDGFA in more than 500 patients with the possible capability of being regarded as PTC biomarkers. Insulin-like growth factor 2 (IGF2), with therapeutic potential in wound healing and epigenetically similar expression patterns in different body tissues, also plays a pivotal role in developing various cancer types. IGF2 activity can regulate its binding to receptors associated with varying expression levels, frequently disrupted in cancer [85]. There is only one study showing the Involvement of IGF2 in the pathogenesis of PTC where the same IGF2 downregulation was observed for using cortisol, resulting in the decline of bone mass [58,86]. RPS6KA5, also known as MSK1/MSPK, is an essential substrate of the MAPK-activated protein kinase family, which regulates protein synthesis, cell cycle, and migration in response to hormones [87]. In colorectal cancer, RPS6KA5 upregulation may not be accounted for in the accurate diagnosis of the disease [88]. A recent study on PTC revealed that the downregulation of RPS6KA5 may be an important biomarker in developing this type of TC [59]. GADD45B is a member of the GADD45 family involved in cell proliferation induced against stress signals, including inflammatory cytokines and mitogen stimulation [89]. Dysregulation of the GADD45B gene have been reported in some cancer types related to Homo sapiens organism in which the tissues of lymphoma, thyroid, breast, cervical, lung, and esophageal are get involved [[90], [91], [92], [93], [94]]; moreover, the same situation can be imagined for PTC as well [60].

FGFR2 is crucial in different cellular processes through ligand binding, like cell division, growth, differentiation, embryonic development, tissue repair, and angiogenesis. According to the current research findings, we speculated that the downregulation of FGFR2, also known as CD332, is potentially a significantly differentially expressed gene between PTC and normal tissues. Its role in the PTC has not been well understood. However, the high expression of FGFR2 in different human cancers, such as lung and breast cancers, has been reported elsewhere. Finally, Fu et al. confirmed the FGFR2 as a downregulated target of miR-1266 using quantitative reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) and Western blot procedures [62]. FGF7, as a source of mitogen mesenchyme, acts on FGFR2 and induces the proliferation, differentiation, and migration of epithelial cells. It occurs upon FGFS binding through the MAPK signaling pathway activated during wound and mucosal healing [95]. In other cases of human cancers, such as colorectal cancer, the contribution of FGF7 and FGFR2 signaling remains unclear [96]. Among the list of genes Cong et al. [56] identified in PTC, FGF7 downregulation was evidenced as a confirmation of the outcomes in our study.

As an example, it has been shown that the small GTPase, RAC2, has a role in integrin and immune receptor signaling, polarization to M2 macrophages, and ROS production during host defense [[97], [98], [99]]. It was discovered that animals like mice lacking the RAC2 gene had significantly reduced tumor development, angiogenesis, and metastasis. RAC2 was shown to be downregulated in a PTC with/without HT RNA-seq data set study, indicating that the genes encoding these proteins are affected by ROS. Moreover, It was discovered that the tumor tissues had a reduced level of RAC2 expression [47].

MAPK13 is one distinct gene of the four encoded p38 MAPKs, attracting fewer research studies [100,101]. They also included genes such as MAPK13 and DUSP5 from the MAPK pathway in the case of BRAF-related PTC [102].

In some cancer types, including melanoma, pancreatic cancer, and papillary thyroid cancer, HSPA1B, a member of the HSP70 network (Heat shock proteins), was one of the genes expressed in predominantly plasma and serum samples using the ultracentrifugation (UC) isolation method [[103], [104], [105]]. Considering the HSPA1B target gene, several micro-RNAs such as miR-495–3p, miR-615–3p, miR-326, miR-331–3p, miR-130b-5p, miR-15a-5p and miR-125b-5p were involved in samples of plasma extracellular vesicles derived from cancer patients (e.g., lung cancer, clear cell renal cell carcinoma, prostate cancer, and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma) [[106], [107], [108], [109]].

4.4. BRAF-like and RAS-like mutations

Generally speaking, the association between BRAF mutation and age was found in the literature without any significant relationship among the other clinical features. Also, no clinical attributes were reported in PTC patients regarding RAS mutation [110]. In another study, three out of twenty-four PTC patients harbored the BRAF mutation H/K-RAS mutations, whereas the others lacked somatic mutation [111]. This study shows that the union cohort of BRAF/RAS-like mutations is almost related to age and clinical attributes based on the identified DEGs, which aligns with the literature findings.

4.5. Clinical features associated with ETE

Although ETE has been recognized as a significant pathogenic characteristic indicating negative consequences, very little research has focused on its molecular basis. The combined analysis of genomic and clinical data revealed substantial genetic components of PTC associated with ETE in this research. In a study, the downregulation of the WNT4 gene was directly correlated with ETE [112]; however, in this research, except for four genes (i.e., FGF7, GADD45B, CCND1, and HEY2) from Wnt, MAPK, and Notch signaling pathways, the other remaining fifteen significant DEGs were significantly associated with ETE.

4.6. Target therapy, resistance, and dynamic changes of mutation status

Integrating current targeted therapy and resistance mechanisms in PTC involving MAPK, Notch, and Wnt signaling pathways is crucial for improving clinical outcomes. The BRAFV600E mutation, found in a significant percentage of PTCs, presents an opportunity for targeted drug therapy [113]. However, resistance mechanisms against BRAF-targeted treatments have been identified, emphasizing the need for a comprehensive understanding of resistance mechanisms [114]. Additionally, the stimulation of the MAPK pathway, particularly the activation of MAPK signaling, is actively explored as a therapeutic target for thyroid cancer [115]. The importance of targeting the MAPK signaling pathway, which includes mutations in RET, RAS, and BRAF, is further emphasized because these genetic changes are often seen in PTC [116]. Thyroid cancer is not the only kind of cancer in which Notch signaling has been shown to have a role; papillary carcinomas have also been linked to this pathway [117]. Furthermore, a correlation exists between the methylation of DACT2 and the stimulation of the Wnt signaling pathway, which facilitates the spread of PTC [118]. To overcome resistance and maximize the effectiveness of targeted treatment, new studies have shown that combined targeting of MAPK and PI3K pathways may enable the re-differentiation of Braf-mutated thyroid cancer organoids [119]. Furthermore, adenyl cyclase activators have shown growth suppression of thyroid cancer cells, indicating the potential for alternative targeted therapeutic approaches [120]. These findings underscore the importance of exploring diverse targeted therapy options to overcome resistance and improve treatment efficacy. Clinical progress in PTC requires more investigation of the interplay between the MAPK, Notch, and Wnt signaling pathways and the integration of current targeted therapies. To improve the efficacy of treatment options and address resistance mechanisms in PTC, targeting the revealed genetic abnormalities and signaling networks may be fruitful, while also investigating innovative therapeutic approaches.

On the other hand, the dynamic changes in the mutational status and consequences of the signal transmission chain in PTC are critical considerations in understanding the disease progression and developing effective therapeutic strategies. The activation of MEK and ERK is a key contributor to the oncogenic phenotype, and mutations in RAS and Raf, which are upstream pathway components, are common and include the BRAFV600E mutant [121]. These mutations, along with genetic alterations like BRAF and RET/PTC rearrangement, are responsible for PTC's onset, progression, and dedifferentiation, primarily through the activation of the MAPK and PI3K signaling cascades [122]. Moreover, an essential research subject is the impact of MAPK activation on additional signaling pathways implicated in oncogenic transformation, including Notch. It is vital for comprehending the dynamic alterations in the mutational status of PTC and the repercussions of the signal transmission chain [123]. Also, many types of cancer have genetic mutations that change signaling pathways. For example, mutated BRAF is common in thyroid cancer. It shows how important it is to understand how mutational status changes and how those changes affect signaling pathways [113]. Also, knowing how the BRAFV600E mutation affects the disease's signaling cascade is crucial since it is the most common genetic change in PTC [124]. Therefore, integrating the knowledge of dynamic changes in mutational status and the consequences of the signal transmission chain is essential for advancing the understanding and management of PTC.

4.7. Limitations and projections of a meta-analysis on GEO datasets in PTC disease

Meta-analyses utilizing Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) datasets have provided valuable insights into the molecular landscape of PTC. However, several limitations and future projections should be considered to enhance the utility and reliability of such analyses.

Limitations.

-

1.

Data Heterogeneity: Heterogeneity may be introduced into the meta-analysis due to including several GEO datasets with varying sample sizes, platforms, and experimental procedures.

-

2.

Data Quality: The reliability and repeatability of the meta-analysis findings may be affected by differences in data quality between GEO datasets, such as batch effects and technological biases.

-

3.

Sample Size and Power: Statistical power and generalizability of results may be compromised due to small sample numbers in certain GEO datasets.

-

4.

Publication Bias: Publication bias is a potential issue for meta-analyses that depend on published papers within GEO databases since non-significant or negative findings may be underestimated.

-

5.

Data Integration Challenges: Data consistency and comparability are difficult to guarantee due to the difficulties in integrating and harmonizing data from disparate GEO databases.

Projections.

1.Standardized Protocols: To improve data harmonization and reduce technical heterogeneity, future meta-analyses should emphasize the implementation of standardized techniques for data preparation, standardization, and quality control.

-

2.

Advanced Statistical Methods: More refined insights into the molecular landscape of PTC may be gained by using sophisticated statistical approaches like meta-regression and network meta-analysis to overcome data heterogeneity.

-

3.

External Validation: To increase the robustness and trustworthiness of discovered molecular markers, future meta-analyses are anticipated to use external validation cohorts to validate results from GEO datasets.

-

4.

Longitudinal Studies: Dynamic variations in gene expression patterns are related to PTC development and recurrence and may be better understood by longitudinal analysis using longitudinal GEO datasets.

-

5.

Multi-Omics Integration: By combining GEO gene expression data with other omics information (such as proteomics and epigenomics), we may get a more complete picture of PTC etiology and better pinpoint possible treatment targets.

Although meta-analyses of GEO datasets have made important contributions to our molecular knowledge of PTC, it will be crucial to advance such studies' reliability and translational value if the aforementioned constraints are overcome and future forecasts are embraced.

5. Conclusion

We have compiled four gene expression profiles of PTC and normal tissues. We performed a meta-analysis, ultimately yielding the list of essential genes within this disease's three MAPK, Wnt, and Notch signaling pathways. All 19 significant genes may engage in all stages of the development and genesis, advancement, and spread of PTC. The research results are proposed as a list of molecular markers and pathways for further investigation. Moreover, the correlations between DEGs and clinical features were demonstrated. Possible associations among BRAF/RAS-like mutations in PTC and the significant DEGs were investigated. In addition to the present meta-analysis study, other corroborative experimental research is required to ensure the correct functions of the current computational and statistical findings; however, all nineteen panels of identified significant genes were evidenced through experimental literature studies and a robust model with a reasonably good concordance index.

Ethical Approval and Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of supporting data

The datasets used for the current study are publicly available in the NCBI-GEO repository, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE29265 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE97001

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE138198

Funding

No financial supports were available for this research.

Authors' information

Biotechnology Research Center, and Kidney Research Center, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Elham Amjad: Data curation, Formal analysis, Resources, Writing – original draft, Investigation, Validation, Visualization. Solmaz Asnaashari: Methodology, Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Validation. Ali Jahanban-Esfahlan: Formal analysis, Investigation, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Supervision. Babak Sokouti: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Contributor Information

Ali Jahanban-Esfahlan, Email: a.jahanban@gmail.com.

Babak Sokouti, Email: b.sokouti@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Nettore I.C., Colao A., Macchia P.E. Nutritional and environmental factors in thyroid carcinogenesis. Int J Env Res Public Health. 2018;15:1735. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15081735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Antonelli A., Ferrari S.M., Fallahi P. Current and future immunotherapies for thyroid cancer. Expert Rev. Anticancer Ther. 2018;18:149–159. doi: 10.1080/14737140.2018.1417845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sung H., Ferlay J., Siegel R.L., Laversanne M., Soerjomataram I., Jemal A., Bray F. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:209–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.La Vecchia C., Malvezzi M., Bosetti C., Garavello W., Bertuccio P., Levi F., Negri E. Thyroid cancer mortality and incidence: a global overview. Int. J. Cancer. 2015;136:2187–2195. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li X., Abdel-Mageed A.B., Mondal D., Kandil E. The nuclear factor kappa-B signaling pathway as a therapeutic target against thyroid cancers. Thyroid. 2013;23:209–218. doi: 10.1089/thy.2012.0237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chmielik E., Rusinek D., Oczko-Wojciechowska M., Jarzab M., Krajewska J., Czarniecka A., Jarzab B. Heterogeneity of thyroid cancer. Pathobiology. 2018;85:117–129. doi: 10.1159/000486422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu T.R., Su X., Qiu W.S., Chen W.C., Men Q.Q., Zou L., Li Z.Q., Fu X.Y., Yang A.K. Thyroid-stimulating hormone receptor affects metastasis and prognosis in papillary thyroid carcinoma. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2016;20:3582–3591. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miftari R., Topçiu V., Nura A., Haxhibeqiri V. Management of the patient with aggressive and resistant papillary thyroid carcinoma. Med. Arch. 2016;70:314–317. doi: 10.5455/medarh.2016.70.314-317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li H., Han Q., Chen Y., Chen X., Ma R., Chang Q., Yin D. Upregulation of the long non-coding RNA FOXD2-AS1 is correlated with tumor progression and metastasis in papillary thyroid cancer. American Journal of Translational Research. 2019;11:5457–5471. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhuang X., Tong H., Ding Y., Wu L., Cai J., Si Y., Zhang H., Shen M. Long noncoding RNA ABHD11-AS1 functions as a competing endogenous RNA to regulate papillary thyroid cancer progression by miR-199a-5p/SLC1A5 axis. Cell Death Dis. 2019;10:620. doi: 10.1038/s41419-019-1850-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Amjad E., Asnaashari S., Sokouti B. Induction of mTOR signaling pathway in the progression of papillary thyroid cancer. Meta Gene. 2020;24 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Amjad E., Asnaashari S., Sokouti B. The role of PI3K signaling pathway and its associated genes in papillary thyroid cancer. J Egypt Natl Canc Inst. 2021;33:11. doi: 10.1186/s43046-021-00068-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Duan P., Bonewald L. The role of the wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway in formation and maintenance of bone and teeth. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2016;77:23–29. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2016.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ma B., Hottiger M.O. Crosstalk between Wnt/β-catenin and NF-κB signaling pathway during inflammation. Front. Immunol. 2016;7:378. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2016.00378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krishnamurthy N., Kurzrock R. Targeting the Wnt/beta-catenin pathway in cancer: Update on effectors and inhibitors. Cancer Treat Rev. 2018;62:50–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2017.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nusse R., Clevers H. Wnt/β-catenin signaling, disease, and emerging therapeutic modalities. Cell. 2017;169:985–999. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vilchez V., Turcios L., Marti F., Gedaly R. Targeting Wnt/β-catenin pathway in hepatocellular carcinoma treatment. World J. Gastroenterol. 2016;22:823. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i2.823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ring A., Kim Y.M., Kahn M. Wnt/catenin signaling in adult stem cell physiology and disease. Stem Cell Reviews and Reports. 2014;10:512–525. doi: 10.1007/s12015-014-9515-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Santoro M., Melillo R.M., Carlomagno F., Vecchio G., Fusco A. Minireview: RET: normal and abnormal functions. Endocrinology. 2004;145:5448–5451. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-0922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kimura E.T., Nikiforova M.N., Zhu Z., Knauf J.A., Nikiforov Y.E., Fagin J.A. High prevalence of BRAF mutations in thyroid cancer: genetic evidence for constitutive activation of the RET/PTC-RAS-BRAF signaling pathway in papillary thyroid carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2003;63:1454–1457. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nikiforova M.N., Nikiforov Y.E. Molecular diagnostics and predictors in thyroid cancer. Thyroid. 2009;19:1351–1361. doi: 10.1089/thy.2009.0240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Namba H., Rubin S.A., Fagin J.A. Point mutations of ras oncogenes are an early event in thyroid tumorigenesis. Mol. Endocrinol. 1990;4:1474–1479. doi: 10.1210/mend-4-10-1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jhiang S.M. The RET proto-oncogene in human cancers. Oncogene. 2000;19:5590–5597. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chakravarty D., Santos E., Ryder M., Knauf J.A., Liao X.-H., West B.L., Bollag G., Kolesnick R., Thin T.H., Rosen N. Small-molecule MAPK inhibitors restore radioiodine incorporation in mouse thyroid cancers with conditional BRAF activation. J. Clin. Investig. 2011;121:4700–4711. doi: 10.1172/JCI46382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kopan R., Ilagan M.X.G. The canonical Notch signaling pathway: unfolding the activation mechanism. Cell. 2009;137:216–233. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.03.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vasko V., Espinosa A.V., Scouten W., He H., Auer H., Liyanarachchi S., Larin A., Savchenko V., Francis G.L., De La Chapelle A. Gene expression and functional evidence of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in papillary thyroid carcinoma invasion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:2803–2808. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610733104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sharov A.A., Schlessinger D., Ko M.S. ExAtlas: an interactive online tool for meta-analysis of gene expression data. J. Bioinf. Comput. Biol. 2015;13 doi: 10.1142/S0219720015500195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tang Z., Kang B., Li C., Chen T., Zhang Z. GEPIA2: an enhanced web server for large-scale expression profiling and interactive analysis. NAR. 2019;47:556–560. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tang Z., Li C., Kang B., Gao G., Li C., Zhang Z. GEPIA: a web server for cancer and normal gene expression profiling and interactive analyses. NAR. 2017;45:W98–w102. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guan X., Cai M., Du Y., Yang E., Ji J., Wu J. CVCDAP: an integrated platform for molecular and clinical analysis of cancer virtual cohorts. NAR. 2020;48:W463–W471. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkaa423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aguirre-Gamboa R., Gomez-Rueda H., Martínez-Ledesma E., Martínez-Torteya A., Chacolla-Huaringa R., Rodriguez-Barrientos A., Tamez-Peña J.G., Treviño V. SurvExpress: an online biomarker validation tool and database for cancer gene expression data using survival analysis. PLoS One. 2013;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0074250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Deng M., Brägelmann J., Kryukov I., Saraiva-Agostinho N., Perner S. FirebrowseR: an R client to the Broad Institute's Firehose Pipeline. Database : the journal of biological databases and curation. 2017;2017:baw160. doi: 10.1093/database/baw160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Benjamini Y., Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. Roy. Stat. Soc. B. 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang K., Liu J., Li C., Peng X., Li H., Li Z. Identification and validation of potential target genes in papillary thyroid cancer. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2019;843:217–225. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2018.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Choi D., Ramu S., Park E., Jung E., Yang S., Jung W., Choi I., Lee S., Kim K.E., Seong Y.J., Hong M., Daghlian G., Kim D., Shin E., Seo J.I., Khatchadourian V., Zou M., Li W., De Filippo R., Kokorowski P., Chang A., Kim S., Bertoni A., Furlanetto T.W., Shin S., Li M., Chen Y., Wong A., Koh C., Geliebter J., Hong Y.K. Aberrant activation of notch signaling Inhibits PROX1 activity to enhance the malignant behavior of thyroid cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2016;76:582–593. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-1199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yang Y.F., Yu B., Zhang X.X., Zhu Y.H. Identification of TNIK as a novel potential drug target in thyroid cancer based on protein druggability prediction. Medicine (Baltim.) 2021;100 doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000025541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lou W., Ding B., Wang J., Xu Y. The involvement of the hsa_circ_0088494-miR-876-3p-CTNNB1/CCND1 Axis in carcinogenesis and progression of papillary thyroid carcinoma. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020;8 doi: 10.3389/fcell.2020.605940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jeon S., Kim Y., Jeong Y.M., Bae J.S., Jung C.K. CCND1 Splice variant as A novel diagnostic and Predictive biomarker for thyroid cancer. Cancers. 2018;10:437. doi: 10.3390/cancers10110437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vasko V., Espinosa A.V., Scouten W., He H., Auer H., Liyanarachchi S., Larin A., Savchenko V., Francis G.L., de la Chapelle A., Saji M., Ringel M.D. Gene expression and functional evidence of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in papillary thyroid carcinoma invasion. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2007;104:2803–2808. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610733104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ao Z.X., Chen Y.C., Lu J.M., Shen J., Peng L.P., Lin X., Peng C., Zeng C.P., Wang X.F., Zhou R., Chen Z., Xiao H.M., Deng H.W. Identification of potential functional genes in papillary thyroid cancer by co-expression network analysis. Oncol. Lett. 2018;16:4871–4878. doi: 10.3892/ol.2018.9306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ray M., Sarkar S. Exploration of differential gene expression with functional characterization and pathways enrichment from microarray profile of papillary thyroid cancer: an in silico genomic approach. Gene Reports. 2020;18 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Smallridge R.C., Chindris A.M., Asmann Y.W., Casler J.D., Serie D.J., Reddi H.V., Cradic K.W., Rivera M., Grebe S.K., Necela B.M., Eberhardt N.L., Carr J.M., McIver B., Copland J.A., Thompson E.A. RNA sequencing identifies multiple fusion transcripts, differentially expressed genes, and reduced expression of immune function genes in BRAF (V600E) mutant vs BRAF wild-type papillary thyroid carcinoma. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2014;99:E338–E347. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-2792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ma B., Shi R., Yang S., Zhou L., Qu N., Liao T., Wang Y., Wang Y., Ji Q. DUSP4/MKP2 overexpression is associated with BRAF(V600E) mutation and aggressive behavior of papillary thyroid cancer. OncoTargets Ther. 2016;9:2255–2263. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S103554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lee E.K., Chung K.W., Yang S.K., Park M.J., Min H.S., Kim S.W., Kang H.S. DNA methylation of MAPK signal-inhibiting genes in papillary thyroid carcinoma. Anticancer Res. 2013;33:4833–4839. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Delys L., Detours V., Franc B., Thomas G., Bogdanova T., Tronko M., Libert F., Dumont J.E., Maenhaut C. Gene expression and the biological phenotype of papillary thyroid carcinomas. Oncogene. 2007;26:7894–7903. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Han J., Chen M., Wang Y., Gong B., Zhuang T., Liang L., Qiao H. Identification of biomarkers based on differentially expressed genes in papillary thyroid carcinoma. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:9912. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-28299-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Subhi O., Schulten H.J., Bagatian N., Al-Dayini R., Karim S., Bakhashab S., Alotibi R., Al-Ahmadi A., Ata M., Elaimi A., Al-Muhayawi S., Mansouri M., Al-Ghamdi K., Hamour O.A., Jamal A., Al-Maghrabi J., Al-Qahtani M.H. Genetic relationship between Hashimoto's thyroiditis and papillary thyroid carcinoma with coexisting Hashimoto's thyroiditis. PLoS One. 2020;15 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0234566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Beltrami C.M., Dos Reis M.B., Barros-Filho M.C., Marchi F.A., Kuasne H., Pinto C.A.L., Ambatipudi S., Herceg Z., Kowalski L.P., Rogatto S.R. Integrated data analysis reveals potential drivers and pathways disrupted by DNA methylation in papillary thyroid carcinomas. Clin Epigenetics. 2017;9:45. doi: 10.1186/s13148-017-0346-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vastrad B., Vastrad C., Kotturshetti I. Identification of potential core genes in hepatoblastoma via bioinformatics analysis. medRxiv. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pusztaszeri M.P., Sadow P.M., Faquin W.C. CD117: a novel ancillary marker for papillary thyroid carcinoma in fine‐needle aspiration biopsies. Cancer Cytopathol. 2014;122:596–603. doi: 10.1002/cncy.21437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Franceschi S., Lessi F., Panebianco F., Tantillo E., La Ferla M., Menicagli M., Aretini P., Apollo A., Naccarato A.G., Marchetti I. Loss of c-KIT expression in thyroid cancer cells. PLoS One. 2017;12 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0173913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chitikova Z., Pusztaszeri M., Makhlouf A.M., Berczy M., Delucinge-Vivier C., Triponez F., Meyer P., Philippe J., Dibner C. Identification of new biomarkers for human papillary thyroid carcinoma employing NanoString analysis. Oncotarget. 2015;6:10978–10993. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chen K.-T., Lin J.-D., Liou M.-J., Weng H.-F., Chang C.A., Chan E.-C. An aberrant autocrine activation of the platelet-derived growth factor α-receptor in follicular and papillary thyroid carcinoma cell lines. Cancer Lett. 2006;231:192–205. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2005.01.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bruland O., Fluge Ø., Akslen L.A., Eiken H.G., Lillehaug J.R., Varhaug J.E., Knappskog P.M. Inverse correlation between PDGFC expression and lymphocyte infiltration in human papillary thyroid carcinomas. BMC Cancer. 2009;9:1–15. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-9-425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhang J., Wang P., Dykstra M., Gelebart P., Williams D., Ingham R., Adewuyi E.E., Lai R., McMullen T. Platelet‐derived growth factor receptor‐α promotes lymphatic metastases in papillary thyroid cancer. J. Pathol. 2012;228:241–250. doi: 10.1002/path.4069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cong D., He M., Chen S., Liu X., Liu X., Sun H. Expression profiles of pivotal microRNAs and targets in thyroid papillary carcinoma: an analysis of the Cancer Genome Atlas. OncoTargets Ther. 2015;8:2271–2277. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S85753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shi L., Chen H., Qin Y.-Y., Gan T.-Q., Wei K.-L. Clinical and biologic roles of PDGFRA in papillary thyroid cancer: a study based on immunohistochemical and in vitro analyses. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2020;13:1094. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Delys L., Detours V., Franc B., Thomas G., Bogdanova T., Tronko M., Libert F., Dumont J.E., Maenhaut C. Gene expression and the biological phenotype of papillary thyroid carcinomas. Oncogene. 2007;26:7894–7903. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Liu C., Feng Z., Chen T., Lv J., Liu P., Jia L., Zhu J., Chen F., Yang C., Deng Z. Downregulation of NEAT1 reverses the radioactive iodine resistance of papillary thyroid carcinoma cell via miR-101-3p/FN1/PI3K-AKT signaling pathway. Cell Cycle. 2019;18:167–203. doi: 10.1080/15384101.2018.1560203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 60.Barros-Filho M.C., de Mello J.B., Marchi F.A., Pinto C.A., da Silva I.C., Damasceno P.K., Soares M.B., Kowalski L.P., Rogatto S.R. GADD45B transcript is a prognostic marker in papillary thyroid carcinoma patients treated with total thyroidectomy and radioiodine therapy. Front. Endocrinol. 2020;11:269. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2020.00269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Albakova Z., Siam M.K.S., Sacitharan P.K., Ziganshin R.H., Ryazantsev D.Y., Sapozhnikov A.M. Extracellular heat shock proteins and cancer: new perspectives. Transl Oncol. 2021;14 doi: 10.1016/j.tranon.2020.100995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Fu Y.T., Zheng H.B., Zhang D.Q., Zhou L., Sun H. MicroRNA-1266 suppresses papillary thyroid carcinoma cell metastasis and growth via targeting FGFR2. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2018;22:3430–3438. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_201806_15166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chastagner P., Rubinstein E., Brou C. Ligand-activated Notch undergoes DTX4-mediated ubiquitylation and bilateral endocytosis before ADAM10 processing. Sci. Signal. 2017;10 doi: 10.1126/scisignal.aag2989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zweifel M.E., Leahy D.J., Barrick D. Structure and Notch receptor binding of the tandem WWE domain of Deltex. Structure. 2005;13:1599–1611. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2005.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tesfazghi S., Eide J., Dammalapati A., Korlesky C., Wyche T.P., Bugni T.S., Chen H., Jaskula-Sztul R. Thiocoraline alters neuroendocrine phenotype and activates the Notch pathway in MTC-TT cell line. Cancer Med. 2013;2:734–743. doi: 10.1002/cam4.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kang J., Yoo J., Lee S., Tang W., Aguilar B., Ramu S., Choi I., Otu H.H., Shin J.W., Dotto G.P., Koh C.J., Detmar M., Hong Y.K. An exquisite cross-control mechanism among endothelial cell fate regulators directs the plasticity and heterogeneity of lymphatic endothelial cells. Blood. 2010;116:140–150. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-11-252270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Park H.S., Jung C.K., Lee S.H., Chae B.J., Lim D.J., Park W.C., Song B.J., Kim J.S., Jung S.S., Bae J.S. Notch1 receptor as a marker of lymph node metastases in papillary thyroid cancer. Cancer Sci. 2012;103:305–309. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2011.02161.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yamashita A.S., Geraldo M.V., Fuziwara C.S., Kulcsar M.A., Friguglietti C.U., da Costa R.B., Baia G.S., Kimura E.T. Notch pathway is activated by MAPK signaling and influences papillary thyroid cancer proliferation. Transl Oncol. 2013;6:197–205. doi: 10.1593/tlo.12442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Geers C., Colin I.M., Gérard A.C. Delta-like 4/Notch pathway is differentially regulated in benign and malignant thyroid tissues. Thyroid. 2011;21:1323–1330. doi: 10.1089/thy.2010.0444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yang T., Li M., Li H., Shi P., Liu J., Chen M. Downregulation of circEPSTI1 represses the proliferation and invasion of non-small cell lung cancer by inhibiting TRIM24 via miR-1248 upregulation. BBRC (Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun.) 2020;530:348–354. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2020.06.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yang Y., Lu T., Li Z., Lu S. FGFR1 regulates proliferation and metastasis by targeting CCND1 in FGFR1 amplified lung cancer. Cell Adhes. Migrat. 2020;14:82–95. doi: 10.1080/19336918.2020.1766308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Alao J.P. The regulation of cyclin D1 degradation: roles in cancer development and the potential for therapeutic invention. Mol. Cancer. 2007;6:24. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-6-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Morrison G., Scognamiglio R., Trumpp A., Smith A. Convergence of cMyc and β-catenin on TCF7L1 enables endoderm specification. EMBO (Eur. Mol. Biol. Organ.) J. 2016;35:356–368. doi: 10.15252/embj.201592116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Katoh M. WNT/PCP signaling pathway and human cancer. Oncol. Rep. 2005;14:1583–1588. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.VanderVorst K., Hatakeyama J., Berg A., Lee H., Carraway K.L., 3rd Cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying planar cell polarity pathway contributions to cancer malignancy. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2018;81:78–87. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2017.09.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Dyberg C., Papachristou P., Haug B.H., Lagercrantz H., Kogner P., Ringstedt T., Wickström M., Johnsen J.I. Planar cell polarity gene expression correlates with tumor cell viability and prognostic outcome in neuroblastoma. BMC Cancer. 2016;16:259. doi: 10.1186/s12885-016-2293-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Guo D., Yuan Z., Ru J., Gu X., Zhang W., Mao F., Ouyang H., Wu K., Liu Y., Liu C. A Spatiotemporal requirement for prickle 1-mediated PCP signaling in Eyelid Morphogenesis and homeostasis. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2018;59:952–966. doi: 10.1167/iovs.17-22947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ågerstam H., Karlsson C., Hansen N., Sandén C., Askmyr M., von Palffy S., Högberg C., Rissler M., Wunderlich M., Juliusson G., Richter J., Sjöström K., Bhatia R., Mulloy J.C., Järås M., Fioretos T. Antibodies targeting human IL1RAP (IL1R3) show therapeutic effects in xenograft models of acute myeloid leukemia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2015;112 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1422749112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Cha Y.J., Koo J.S. Next-generation sequencing in thyroid cancer. J. Transl. Med. 2016;14:322. doi: 10.1186/s12967-016-1074-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zhang Z., Kobayashi S., Borczuk A.C., Leidner R.S., Laframboise T., Levine A.D., Halmos B. Dual specificity phosphatase 6 (DUSP6) is an ETS-regulated negative feedback mediator of oncogenic ERK signaling in lung cancer cells. Carcinogenesis. 2010;31:577–586. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgq020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Black L.E., Longo J.F., Carroll S.L. Mechanisms of receptor tyrosine-protein kinase ErbB-3 (ERBB3) action in human Neoplasia. Am. J. Pathol. 2019;189:1898–1912. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2019.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Schulten H.J., Alotibi R., Al-Ahmadi A., Ata M., Karim S., Huwait E., Gari M., Al-Ghamdi K., Al-Mashat F., Al-Hamour O., Al-Qahtani M.H., Al-Maghrabi J. Effect of BRAF mutational status on expression profiles in conventional papillary thyroid carcinomas. BMC Genom. 2015;16:S6. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-16-S1-S6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Lin J.D., Fu S.S., Chen J.Y., Lee C.H., Chau W.K., Cheng C.W., Wang Y.H., Lin Y.F., Fang W.F., Tang K.T. Clinical Manifestations and gene expression in patients with conventional papillary thyroid carcinoma Carrying the BRAF(V600E) mutation and BRAF Pseudogene. Thyroid. 2016;26:691–704. doi: 10.1089/thy.2015.0044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Abel E.V., Basile K.J., Kugel C.H., 3rd, Witkiewicz A.K., Le K., Amaravadi R.K., Karakousis G.C., Xu X., Xu W., Schuchter L.M., Lee J.B., Ertel A., Fortina P., Aplin A.E. Melanoma adapts to RAF/MEK inhibitors through FOXD3-mediated upregulation of ERBB3. J. Clin. Invest. 2013;123:2155–2168. doi: 10.1172/JCI65780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Chao W., D'Amore P.A. IGF2: epigenetic regulation and role in development and disease. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2008;19:111–120. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2008.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Minuto F., Palermo C., Arvigo M., Barreca A.M. The IGF system and bone. Journal of Endocrinology Investigation. 2005;28:8–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Pei L., Liu H., Ouyang S., Zhao C., Liu M., Wang T., Wang P., Ye H., Wang K., Song C., Zhang J., Dai L. Discovering novel lung cancer associated antigens and the utilization of their autoantibodies in detection of lung cancer. Immunobiology. 2020;225 doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2019.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Fu X., Fan X., Hu J., Zou H., Chen Z., Liu Q., Ni B., Tan X., Su Q., Wang J., Wang L., Wang J. Overexpression of MSK1 is associated with tumor aggressiveness and poor prognosis in colorectal cancer. Dig. Liver Dis. 2017;49:683–691. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2017.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Moskalev A.A., Smit-McBride Z., Shaposhnikov M.V., Plyusnina E.N., Zhavoronkov A., Budovsky A., Tacutu R., Fraifeld V.E. Gadd45 proteins: relevance to aging, longevity and age-related pathologies. Ageing Res. Rev. 2012;11:51–66. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2011.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ying J., Srivastava G., Hsieh W.S., Gao Z., Murray P., Liao S.K., Ambinder R., Tao Q. The stress-responsive gene GADD45G is a functional tumor suppressor, with its response to environmental stresses frequently disrupted epigenetically in multiple tumors. Clin. Cancer Res. 2005;11:6442–6449. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Zerbini L.F., Libermann T.A. GADD45 deregulation in cancer: frequently methylated tumor suppressors and potential therapeutic targets. Clin. Cancer Res. 2005;11:6409–6413. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Guo W., Dong Z., Guo Y., Chen Z., Kuang G., Yang Z. Methylation-mediated repression of GADD45A and GADD45G expression in gastric cardia adenocarcinoma. Int. J. Cancer. 2013;133:2043–2053. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Iacobas D.A., Tuli N.Y., Iacobas S., Rasamny J.K., Moscatello A., Geliebter J., Tiwari R.K. Gene master regulators of papillary and anaplastic thyroid cancers. Oncotarget. 2018;9:2410–2424. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.23417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Do H., Kim D., Kang J., Son B., Seo D., Youn H., Youn B., Kim W. TFAP2C increases cell proliferation by downregulating GADD45B and PMAIP1 in non-small cell lung cancer cells. Biol. Res. 2019;52:35. doi: 10.1186/s40659-019-0244-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Eswarakumar V.P., Lax I., Schlessinger J. Cellular signaling by fibroblast growth factor receptors. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2005;16:139–149. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2005.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Patel A., Tripathi G., McTernan P., Gopalakrishnan K., Ali O., Spector E., Williams N., Arasaradnam R.P. Fibroblast growth factor 7 signalling is disrupted in colorectal cancer and is a potential marker of field cancerisation. J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 2019;10:429–436. doi: 10.21037/jgo.2019.02.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Thomas D.C. The phagocyte respiratory burst: Historical perspectives and recent advances. Immunol. Lett. 2017;192:88–96. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2017.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Joshi S., Singh A.R., Zulcic M., Bao L., Messer K., Ideker T., Dutkowski J., Durden D.L. Rac2 controls tumor growth, metastasis and M1-M2 macrophage differentiation in vivo. PLoS One. 2014;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0095893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Lim M.B., Kuiper J.W., Katchky A., Goldberg H., Glogauer M. Rac2 is required for the formation of neutrophil extracellular traps. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2011;90:771–776. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1010549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Cuenda A., Sanz-Ezquerro J.J. p38γ and p38δ: from Spectators to key Physiological Players. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2017;42:431–442. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2017.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Cuenda A., Rousseau S. p38 MAP-kinases pathway regulation, function and role in human diseases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2007;1773:1358–1375. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2007.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Mancikova V. 2015. Genomic and Genetic Dissection of Thyroid Cancer. [Google Scholar]

- 103.An M., Lohse I., Tan Z., Zhu J., Wu J., Kurapati H., Morgan M.A., Lawrence T.S., Cuneo K.C., Lubman D.M. Quantitative proteomic analysis of serum exosomes from patients with locally advanced pancreatic cancer Undergoing Chemoradiotherapy. J. Proteome Res. 2017;16:1763–1772. doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.7b00024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Luo D., Zhan S., Xia W., Huang L., Ge W., Wang T. Proteomics study of serum exosomes from papillary thyroid cancer patients. Endocr. Relat. Cancer. 2018;25:879–891. doi: 10.1530/ERC-17-0547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.García-Silva S., Benito-Martín A., Sánchez-Redondo S., Hernández-Barranco A., Ximénez-Embún P., Nogués L., Mazariegos M.S., Brinkmann K., Amor López A., Meyer L., Rodríguez C., García-Martín C., Boskovic J., Letón R., Montero C., Robledo M., Santambrogio L., Sue Brady M., Szumera-Ciećkiewicz A., Kalinowska I., Skog J., Noerholm M., Muñoz J., Ortiz-Romero P.L., Ruano Y., Rodríguez-Peralto J.L., Rutkowski P., Peinado H. Use of extracellular vesicles from lymphatic drainage as surrogate markers of melanoma progression and BRAFV600E mutation. J. Exp. Med. 2019;216:1061–1070. doi: 10.1084/jem.20181522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Fang C., Zhu D.X., Dong H.J., Zhou Z.J., Wang Y.H., Liu L., Fan L., Miao K.R., Liu P., Xu W., Li J.Y. Serum microRNAs are promising novel biomarkers for diffuse large B cell lymphoma. Ann. Hematol. 2012;91:553–559. doi: 10.1007/s00277-011-1350-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Bryant R.J., Pawlowski T., Catto J.W., Marsden G., Vessella R.L., Rhees B., Kuslich C., Visakorpi T., Hamdy F.C. Changes in circulating microRNA levels associated with prostate cancer. Br. J. Cancer. 2012;106:768–774. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Du M., Giridhar K.V., Tian Y., Tschannen M.R., Zhu J., Huang C.C., Kilari D., Kohli M., Wang L. Plasma exosomal miRNAs-based prognosis in metastatic kidney cancer. Oncotarget. 2017;8:63703–63714. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.19476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Yao B., Qu S., Hu R., Gao W., Jin S., Liu M., Zhao Q. A panel of miRNAs derived from plasma extracellular vesicles as novel diagnostic biomarkers of lung adenocarcinoma. FEBS Open Bio. 2019;9:2149–2158. doi: 10.1002/2211-5463.12753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Ming J., Liu Z., Zeng W., Maimaiti Y., Guo Y., Nie X., Chen C., Zhao X., Shi L., Liu C., Huang T. Association between BRAF and RAS mutations, and RET rearrangements and the clinical features of papillary thyroid cancer. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2015;8:15155–15162. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Ciampi R., Romei C., Pieruzzi L., Tacito A., Molinaro E., Agate L., Bottici V., Casella F., Ugolini C., Materazzi G., Basolo F., Elisei R. Classical point mutations of RET, BRAF and RAS oncogenes are not shared in papillary and medullary thyroid cancer occurring simultaneously in the same gland. J. Endocrinol. Invest. 2017;40:55–62. doi: 10.1007/s40618-016-0526-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Park J.Y., Yi J.W., Park C.H., Lim Y., Lee K.H., Lee K.E., Kim J.H. Role of BRAF and RAS mutations in extrathyroidal extension in papillary thyroid cancer. Cancer Genomics Proteomics. 2016;13:171–181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Hanly E.K., Rajoria S., Darzynkiewicz Z., Zhao H., Suriano R., Tuli N., George A.L., Bednarczyk R., Shin E.J., Geliebter J., Tiwari R.K. Disruption of mutated BRAF signaling Modulates thyroid cancer phenotype. BMC Res. Notes. 2014 doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-7-187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Zaman A., Wu W., Bivona T.G. Targeting oncogenic BRAF: Past, present, and future. Cancers. 2019 doi: 10.3390/cancers11081197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Nikiforov Y.E. Thyroid carcinoma: molecular pathways and therapeutic targets. Mod. Pathol. 2008 doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2008.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Fuziwara C.S., Saito K.C., Leoni S., Waitzberg A.F.L., Kimura E.T. The highly expressed FAM83F protein in papillary thyroid cancer Exerts a Pro-oncogenic role in thyroid follicular cells. Front. Endocrinol. 2019 doi: 10.3389/fendo.2019.00134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]