Abstract

Transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) is a noninvasive brain stimulation technique for modulating neuronal excitability by sending a weak current through electrodes attached to the scalp. For decades, the conventional tDCS electrode for stimulating the superficial cortex has been widely reported. However, the investigation of the optimal electrode to effectively stimulate the nonsuperficial cortex is still lacking. In the current study, the optimal tDCS electrode montage that can deliver the maximum electric field to nonsuperficial cortical regions is investigated. Two finite element head models were used for computational simulation to determine the optimal montage for four different nonsuperficial regions: the left foot motor cortex, the left dorsomedial prefrontal cortex (dmPFC), the left medial orbitofrontal cortex (mOFC), and the primary visual cortex (V1). Our findings showed a good consistency in the optimal montage between two models, which led to the anode and cathode being attached to C4–C3 for the foot motor, F4–F3 for the dmPFC, Fp2–F7 for the mOFC, and Oz–Cz for V1. Our suggested montages are expected to enhance the overall effectiveness of stimulation of nonsuperficial cortical areas.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s13534-023-00335-2.

Keywords: Transcranial direct current stimulation, Nonsuperficial cortical region, Finite element method, Noninvasive brain stimulation, Optimal electrode montage

Introduction

Transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) is a non-invasive neuromodulation method that transmits weak electrical current to the brain through electrodes attached to the scalp [1]. Electric fields produced by the currents modulate neural excitability by shifting the membrane potential [2]. Generally, single channel tDCS with an anode and cathode is used for stimulation. Depending on the purpose of tDCS, either the anode or cathode is affixed to the scalp above the targeted cortex. The anodal tDCS, in which the anode is positioned above the target, is used to modulate the excitability of neurons in the targeted cortex, whereas the cathodal tDCS is used to suppress neural activity. The application of tDCS has shown effective in enhancing cognitive functions including working memory [3, 4] and decision-making [5]. Furthermore, it has also been applied in clinical studies for the treatment of mental and neurological disorders, such as depression [6], epilepsy [7], and recovery from Parkinson’s disease and stroke [8, 9].

The placement of tDCS electrodes plays a crucial role in determining the electric field distribution inside the brain. Nitsche and Paulus [1] presented evidence that motor-evoked potential (MEP) changes depending on the location of tDCS electrodes. Mahmoudi, Haghighi [10] revealed that the after-effects of tDCS exhibit variability depending on the placement of the electrodes. In addition, the influence of the electrode montage on the electric field distribution has been demonstrated through computational simulations [11]. Moreover, simulations have been used to investigate the optimal electrode montage for more effective stimulation of the target [12]. For instance, Seibt, Brunoni [13] suggested a new electrode montage for stimulating the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (dlPFC) that produces higher efficacy compared to the conventional one. Furthermore, a previous study confirmed that the effectiveness of the optimal electrode montage obtained from the simulation by assessing MEP, suggesting that tDCS with the optimal electrode montage resulted in a higher MEP compared to conventional tDCS [14].

So far, previous studies have mostly focused on the investigation of the optimal electrode montage for the stimulation of superficial cortical regions, such as the prefrontal cortex, hand motor cortex, and dlPFC. However, investigations of the optimal electrode montage for stimulating nonsuperficial cortical regions are still lacking. To address this, we investigated the optimal electrode montages for delivering the maximum electric field to four different targets located in nonsuperficial cortical regions using two finite element head models. In this study, the nonsuperficial cortex is referred to as the cortical regions that are not located over the neocortex but on the medial surface of the brain. Especially, we focused on the nonsuperficial cortical areas located at the medial cortex related to neurophysiological functions that can be enhanced by external electrical stimulation [15]. Four different regions that are crucial for brain functions were chosen as regions of interest (ROIs): (i) the left foot motor cortex (it can be referred to as the leg motor cortex), (ii) the left dorsomedial prefrontal cortex (dmPFC), (iii) the left medial orbitofrontal cortex (mOFC), and (iv) the primary visual cortex (V1). It has been shown that the motor cortex is involved in both the planning and execution of movement [16]. Both dmPFC and mOFC play a role in decision-making [17], and V1 is highly associated with visual functions [18]. For each target, an anode and cathode were selected from electrode candidates determined manually based on an international 10–20 EEG configuration. For all possible combinations of electrode montages, we calculated the electric field by solving a quasi-static Laplace equation using the finite element method (FEM). Subsequently, the optimal electrode montage that could deliver the maximum electric field to the target was determined for each ROI. The efficacy of the optimal electrode montage was validated through comparison with the conventional montage.

Methods

Head modeling

Finite element head models were constructed from two male subjects (ages 27 and 29) with no clinical history of neuropsychological disorders. The head models were identified as Hsub1 and Hsub2 in this study. A T1-weighted MRI was acquired from a 3T MAGNETOM Trio scanner (Siemens, Erlangen, Germany) with a resolution of 1 mm for Hsub1 and 0.8 mm for Hsub2. Both subjects were required to provide a written consent after they had been informed of the purpose of the experiment. They also agreed on the publication of their head images in an online open-access publication by signing the written consent. The experimental protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) Committee of Hanyang University (HYI-17-180-5). Four different tissues, including scalp, skull, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), and brain were segmented with a semi-automatic method using Curry 7 (Compumedics USA, El Paso, TX, USA). The manual segmentation was conducted for the segmentation of eyeballs. Own scripts of Matlab (Mathworks, Natick, MA, USA) were used to correct the segmentation errors and improve the quality of the surface triangle mesh [19]. The total numbers of nodes and elements are 129,103 nodes and 804,251 elements for Hsub1 and 140,496 nodes and 871,004 elements for Hsub2. The left foot motor cortex, left dmPFC, left mOFC, and V1 were designated as ROI in the consideration of an anatomical structure in each head model (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1.

A Illustration of finite element head models of Hsub1 and Hsub2 with segmented five different tissues: Scalp (red), skull (green), CSF (blue), brain (yellow), and eyeball (purple). Illustration of regions of interest (ROIs): left foot motor cortex, left dorsomedial prefrontal cortex (dmPFC), left medial orbitofrontal cortex (mOFC), and primary visual cortex (V1). B Illustration of electrode candidates based on an international 10–20 EEG configuration. The red and the blue represent the candidate for the anode and cathode, respectively. These positions were manually selected with consideration of the location of each ROI. (Color figure online)

Electrode placement

Electrodes were attached based on an international 10–20 EEG electrode system. Their locations were determined mathematically based on a previous method [20]. The electrode candidates for four different ROIs were manually chosen considering the location of each ROI (Fig. 1A). To deliver the normal-direction electric field inwardly to the cortical surface, the right hemisphere was chosen as the candidate for the anode. The cathode candidate was chosen in consideration of the target region, following the exclusion of several candidates that could hardly deliver the electric field to each target (see Fig. 1B). For V1, the anode was consistently located at Oz because V1 includes both the right and left hemispheres. In addition, we considered the additional electrode candidates for the foot motor cortex, dmPFC, and mOFC, specifically the anode placed over Cz, Fz, and Fpz, respectively. This additional investigation was informed by previous studies that aimed to stimulate the medial cortex by placing the electrode directly above the target regions [21–23]. The area and thickness of the square electrode were assumed to be 16 cm2 and 5 mm, respectively.

Optimization of electrode montages

A total of 206 finite element models that consist of 103 different electrode montages for two head models were created. The Fp2–Fpz montage for mOFC was excluded due to the overlap between two electrodes. For all finite element models, the electric field was evaluated using FEM by solving the Laplace equation given by , where σ and φ represent electrical conductivity and electrical potential, respectively. A Dirichlet boundary condition was applied to the upper side of the anode with 1 V and that of the cathode with 0 V. Then, the electric field in the entire domain was scaled by the ratio of the injection current to be 2 mA. All tissues were assumed to be homogeneous and isotropic, and the electrical conductivities of tissues and electrodes were set in line with values from the previous study [24]. The FEM solver to evaluate the electric field inside the human head was based on that used in the Comets toolbox (http://www.cometstool.com) developed by our group, which has been extensively employed by more than 40 research groups all around the world [25, 26]. Next, both the absolute and normal components of the electric field were calculated, denoted by and , respectively. To evaluate the amount of the electric field delivered to the target area, we computed the average electric field intensity (AE) of AEabsolute (V/m) and AEnormal (V/m), which can be calculated by dividing the summation of electric field of and that penetrate the target into the area of each ROI. Finally, the optimal electrode montages that maximize the AEnormal were determined for each ROI.

Comparison with the conventional montages

For each ROI, the effectiveness of the suggested optimal electrode montages was compared to that of the conventional electrode montages. The conventional montage was determined according to either previous studies or the general electrode placement, placing the active electrode above the target. Especially, the polarities of the conventional electrodes were switched so that the electric field was delivered inwardly to the surface of the cortex in the ROI. The conventional montage for the foot motor cortex has not been reported; thus, the montage for stimulating the leg motor cortex was alternatively used. The Fp2–C1 montage was selected as the conventional montage for the foot motor cortex [27]. For the dmPFC, the F4–Fz montage for Hsub1 and Fp2–Fz montage for Hsub2 were selected for the conventional montage according to the general placement, which involves attaching the active electrode above the target [28]. Thus, we placed the cathode on Fz, which is the nearest location to the dmPFC, and location of the anode was decided based on the optimization results. The P4–Fp1 montage was selected as the conventional montage for mOFC by following the Fp1-P4 montage used in stimulation of the orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) which is a subdivision of OFC [29]. Lastly, for V1, Oz–Cz montage is selected for the conventional montage since it is widely used montage for V1 [30].

Results

For each ROI, the optimal electrode montage that maximizes AEnormal was determined and compared to the conventional montage. As the ROIs were in the left hemisphere, only the normal-direction electric field distributions in the left hemisphere were depicted. For V1, the electric field distributions in both occipital and medial cortical regions were shown to investigate the efficacy of the optimal electrode montage. In addition, the streamlines of electric fields generated from the anode were illustrated to identify the magnitude and direction of the electric field delivered to the target area. The color of the streamlines indicates the magnitude of the electric field. Note that AEnormal values of the optimal and conventional montages for both head models are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

The average electric field intensity of the normal component AEnormal when applying the conventional electrode montage and the optimal electrode montage for ROIs for each head model. ‘Con’ and ‘Opti’ represent the conventional electrode montage and the optimal electrode montage, respectively

| Head models | Foot motor cortex | dmPFC | mOFC | V1 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Con | Opti | Con | Opti | Con | Opti | Con | Opti | |

| Hsub1 | 0.17 | 0.92 | 0.28 | 1.03 | 0.43 | 0.77 | 0.45 | 0.45 |

| Hsub2 | 0.23 | 0.68 | 0.2 | 0.69 | 0.22 | 0.58 | 0.42 | 0.42 |

Left foot motor cortex

Figure 2 shows that the optimal electrode montage was determined as a C4–C3 montage for both head models. Relatively high AE was observed when the cathode was attached to C3, regardless of the location of the anode. On the contrary, attaching the anode to Cz did not deliver as strong electric fields to the foot motor cortex as the optimal electrode montage (see Fig. S1 in Supplementary materials). Figure 3 shows that the optimal electrode montage delivers a higher electric field to the target compared to the conventional one. Electric fields tend to flow through the foot motor cortex perpendicular to the cortical surface for optimal montage (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 2.

The average electric field intensity of AEabsolute (left column) and AEnormal (right column) among various electrode montages for the stimulation of the left foot motor cortex in both head models. The different colors of bar graphs correspond to different positions of the anode depending on the position of the cathode. (Color figure online)

Fig. 3.

A Distributions of electric fields with normal direction when applying the optimal and conventional electrode montage for stimulation of the left foot motor cortex in both head models. The placement of the anode (red) and cathode (blue) was shown beside the illustration of electric field distribution. B The streamlines of the electric field for the optimal electrode montage (left) and conventional electrode montage (right) for both head models. The location of the left foot motor cortex was shown with the black rectangle, and the color of the streamlines indicates the magnitude of electric fields. (Color figure online)

Left dmPFC

Figure 4 shows that the F4–F3 and Fp2–F3 montages were determined to be the optimal electrode montage for Hsub1 and Hsub2, respectively. It indicates that the cathode placed on F3 allows for good performance in delivering electric fields to dmPFC in both head models. Similar to the foot motor cortex, the anode placed on Fz produced a little effect on delivering the electric field to dmPFC compared to the optimal electrode montage (see Fig. S2). As demonstrated in Fig. 5, the optimal electrode montage allows for delivering a much larger electric field to dmPFC. This is due to the stronger electric field delivered perpendicularly to dmPFC (see Fig. 5B).

Fig. 4.

The average electric field intensity of AEabsolute (left column) and AEnormal (right column) among various electrode montages for the stimulation of the left dmPFC in both head models. The different colors of bar graphs correspond to different positions of the anode depending on the position of the cathode

Fig. 5.

A Distributions of electric fields with normal direction when applying the optimal and conventional electrode montage for stimulation of the left dmPFC in both head models. The placement of the anode (red) and cathode (blue) was shown beside the illustration of electric field distribution. B The streamlines of the electric field for the optimal electrode montage (left) and conventional electrode montage (right) for both head models. The location of the left dmPFC was shown with the black rectangle, and the color of the streamlines indicates the magnitude of electric fields. (Color figure online)

Left mOFC

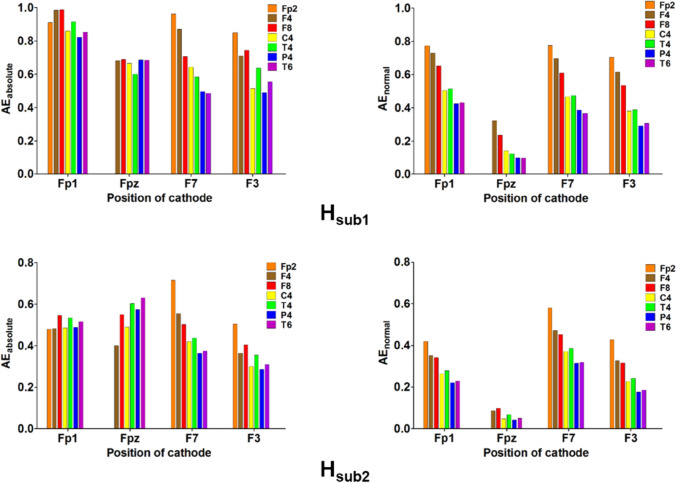

The Fp2–F7 montage was determined to be the optimal electrode montage for both head models (Fig. 6). The anode attached to Fpz did not send a strong electric field to the target compared to the optimal electrode montage (see Fig. S3). Our results demonstrate that a large amount of the electric field was delivered to the target area with the optimal electrode montage compared to the conventional one for both head models (Fig. 7A). The streamlines of electric fields are shown in Fig. 7B, demonstrating that electric fields were perpendicularly delivered to the cortical surface of target regions for the optimal electrode montage. Although the strong electric field flowed into the target areas with the conventional electrode montage as in the optimal one, the direction of the electric field was more parallel to the target surface compared to applying the optimal electrode montage.

Fig. 6.

The average electric field intensity of AEabsolute (left column) and AEnormal (right column) among various electrode montages for the stimulation of the left mOFC in both head models. The different colors of bar graphs correspond to different positions of the anode depending on the position of the cathode. (Color figure online)

Fig. 7.

A Distributions of electric fields with normal direction when applying the optimal and conventional electrode montage for stimulation of the left mOFC in both head models. The placement of the anode (red) and cathode (blue) was shown beside the illustration of electric field distribution. B The streamlines of the electric field for the optimal electrode montage (left) and conventional electrode montage (right) for both head models. The location of the left mOFC was shown with the black rectangle, and the color of the streamlines indicates the magnitude of electric fields. (Color figure online)

V1

Our findings shows that there was no big difference in AE among various electrode montages (see Fig. S4). Nevertheless, the Oz–Cz montage produces marginally higher currents in V1 than the other montages for both head models. This montage coincidentally matches the conventional electrode montage. To demonstrate the electric field distribution depending on the location of the cathode, the electric field distributions when applying three different electrode montages were shown: Oz–Cz, Oz–Fpz and Oz–left cheek montage (see Fig. 8). Electric fields were mainly delivered to the cortical regions right below the anode. However, as the distance between the two electrodes decreased, the more electric field was delivered to the cortical regions between the electrodes. In comparison to the occipital lobe, the medial cortex was hardly stimulated with all montages since the electric field was mostly delivered in the parallel direction.

Fig. 8.

Distributions of electric fields in the normal direction for stimulating V1. The optimal montage (Oz–Cz), the montage determined by the highest AEabsolute (Oz–Fpz) and the electrode montage with placing cathode over extra-cephalic region (Oz-left cheek) were shown for both head models. The placement of the anode (red) and cathode (blue) were shown beside the illustrations of electric field distribution. Black squares in figures represent the location of the anode at Oz. (Color figure online)

Discussion

In this study, we identified optimal electrode montages for stimulating four different ROIs located in nonsuperficial cortical regions. Compared to the conventional montage, the optimal electrode montage delivers a stronger electric field to ROIs for both head models. The normal direction of electric fields was considered in the optimization because pyramidal cells are aligned perpendicular to the cortical surface [31]. The optimal electrode montages for stimulating the ROIs in both head models coincided except for dmPFC. In detail, attaching the optimal electrode montage (F4–F3) showed superior performance in delivering the electric field to dmPFC compared to the other montages for Hsub1. However, there was no big difference between AEnormal of 0.69 with the optimal electrode montage (Fp2–F3) and 0.68 with the second-best montage (F4–F3) for Hsub2. It indicates that the F4–F3 montage might be suitable for effective modulation of dmPFC for both head models. Based on these results, we carefully suggest the optimal electrode montage for effective modulation of four ROIs: C4–C3 for foot motor cortex, F4–F3 for dmPFC, Fp2–F7 for mOFC, and Oz–Cz for V1.

For the foot motor cortex, the location close to Cz where the largest motor response was produced in the tibialis anterior muscle by TMS was selected as the location of the active electrode for stimulating the foot motor cortex [32]. However, this TMS-aided montage not only struggles to effectively deliver the electric field to the foot motor cortex but also results in parallel directional electric fields to the cortical surface causing a poor outcome of tDCS. On the other hand, our findings suggest that the C4–C3 montage can deliver a larger electric field to the foot motor cortex compared to the conventional one (see Fig. 3 and S1). As the intensity of the electric field generated by tDCS plays a critical role in inducing the effects of tDCS [21], our suggested montage can be more effective in stimulating the foot motor cortex to treat a foot paralysis caused by a head injury, stroke, or other neurological disorders.

For dmPFC, there is no specific conventional montage for stimulating dmPFC. However, a previous study demonstrated that attaching the anode close to Fz allows for effective stimulation of dmPFC [33]. Although the previous study demonstrated the effectiveness of transcranial electrical stimulation on dmPFC, our results showed that more electric field was delivered to dmPFC when applying the optimal electrode montage compared to the montage attaching the anode on the mid-frontal line (e.g., Fz) (see Fig. 5 and S2). It implies that our optimal electrode montage might improve the efficacy of tDCS for dmPFC on various cognitive processes, such as decision-making and social cognition.

For mOFC, which is a subdivision of OFC, also referred to as ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC), a previous study showed the enhancement of facial expression recognition by right OFC-tDCS with attaching the active electrode to Fp2 [29]. The montage used in this study was selected as the conventional one in our study. Another study reported that emotional scene processing was modulated using vmPFC-tDCS by attaching the electrode on the mid-frontal line (close to Fpz) [22]. From our findings, the suggested montage Fp2–F7 can deliver stronger currents to mOFC compared to the montages used in the previous studies. Thus, we believe that the optimal montage for mOFC would allow for enhancing the efficacy of tDCS.

Contrary to other ROIs, the optimal electrode montage for V1 appears to be the same as the conventional one. Our results showed that the difference in the amount of the electric field in V1 among different electrode montages was quite small. This supports the fact that a similar electric field flows into V1 with the anode placed on Oz regardless of the location of the cathode used in the previous studies [30, 34, 35]. It seems obvious that the difference in electric fields in V1 would be little regardless of the location of the cathode due to the anode being fixed at Oz. However, our simulation study demonstrated the electric field distribution in V1 according to various montage used in the previous study for the first time.

Our findings indicated that a higher AEabsolute results in a higher AEnormal for most cases. However, in other cases, it appears that AEnormal differs from the pattern observed in AEabsolute. For instance, AEnormal decreased considerably in comparison to AEabsolute when the cathode was positioned above the midline (e.g., Cz, Fz, and Fpz). This indicates that the electric field flowed mainly in a parallel direction. In other words, the orientation of electric fields for the simulation can influence the determination of the electrode montage. A previous study demonstrated that normal directional tDCS has a higher performance in stimulating the motor cortex than parallel directional tDCS [36]. Despite this, it should be noted that the parallel direction of electric fields can also affect stimuli in other neurons (e.g., interneurons) arranged parallel to the cortical surface [37]. Thus, it might be prudent to consider both normal and parallel directions of electric fields, which is the absolute intensity, to determine the optimal electrode montage that can maximize the effectiveness of tDCS.

Our study has some limitations. First, we did not differentiate between gray matter (GM) and white matter (WM), instead segmenting the brain as one whole brain with the electrical conductivity of the GM. This approach might cause discrepancies in the electric field distribution when compared to an actual human brain. However, a previous study reported that the difference in current density between GM and WM was negligible compared to that between other tissues, such as the scalp and skull, CSF, and GM [38]. Thus, the segmentation of WM might not strongly influence to change in the electric field distribution in a way that affects the determination of the optimal electrode montage. Second, anisotropic conductivities of the skull and white matter were not considered in this study. Based on the previous study, the difference in electric field between isotropic and anisotropic head models was not considerably large [39, 40]. Nevertheless, WM and anisotropic tissue conductivity will be considered in our future studies to enhance the accuracy of the optimization of electrode montages. Last, only two FE head models were used for the optimization. There may be inter-subject variability in the optimal electrode montage due to anatomical structure differences, such as skull thickness, CSF thickness, and cortical folding pattern [41, 42]. While the same montage was determined to be optimal in most cases, it would be beneficial to use multiple head models to determine the optimal montage that can generally apply to individuals.

We expect that more effective electrode montage may be investigated by employing new approaches in future studies. Firstly, we only considered 19 electrode candidates based on an international 10–20 EEG electrode system. We believe that the use of more electrode candidates might enhance the overall efficacy of stimulating the nonsuperficial cortex. However, it should be considered that a small difference in the position of electrodes when applying dense electrode candidates may not markedly affect electric fields since the electrodes are relatively large. Nevertheless, the use of more electrode candidates is necessary in future studies. Secondly, the use of single channel tDCS for stimulating nonsuperficial cortex presents challenges in avoiding unwanted stimulation of the superficial cortex. One potential solution is to apply multiple electrodes with an optimization that maximizes the electric field delivered to the target while minimizing the electric field delivered to the non-targeted region may solve this issue [43]. Although the effectiveness of multi-channel tDCS has been demonstrated [44, 45], single-channel tDCS has been continuously used for therapeutic purposes (e.g., treatment of mental disorders, rehabilitation) [46–48] due to its ease of use. Given this, several studies have attempted to stimulate the medial surface of the brain using single-channel tDCS [49–51]. We thus expect that our findings can provide the electrode montage that can effectively stimulate nonsuperficial cortical regions, which would improve the behavior outcomes of tDCS in clinical applications. Nonetheless, the optimization of electrode locations is crucial to enhance the efficacy of tDCS. We believe that our suggested electrode montages could be practically applied for more effective stimulation of the nonsuperficial cortex.

Conclusion

We investigated the optimal electrode montages for stimulating nonsuperficial regions using two head models and validated the effectiveness of the optimal electrode montage through comparison with the conventional montage. Our findings showed that the optimal montage delivers the electric field more perpendicular to the cortical surface of the ROI. Importantly, the optimal montage for both head models was consistent. Based on these findings, we carefully suggest the electrode montage for stimulation of nonsuperficial cortical regions and expect the efficacy of the suggested montages to be validated through human trials in the future.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Original Technology Research Program for Brain Science through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (NRF- 339-20150006).

Data availability

Please contact the corresponding author (sangjunlee35@gmail.com) for data requests.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Nitsche MA, Paulus W. Excitability changes induced in the human motor cortex by weak transcranial direct current stimulation. J Physiol. 2000;527(3):633–639. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.t01-1-00633.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liebetanz D, et al. Pharmacological approach to the mechanisms of transcranial DC-stimulation‐induced after‐effects of human motor cortex excitability. Brain. 2002;125(10):2238–2247. doi: 10.1093/brain/awf238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hill AT, Fitzgerald PB, Hoy KE. Effects of anodal transcranial direct current stimulation on working memory: a systematic review and meta-analysis of findings from healthy and neuropsychiatric populations. Brain Stimul. 2016;9(2):197–208. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2015.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nissim NR, et al. Effects of transcranial direct current stimulation paired with cognitive training on functional connectivity of the working memory network in older adults. Front Aging Neurosci. 2019;11:340. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2019.00340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ouellet J, et al. Enhancing decision-making and cognitive impulse control with transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) applied over the orbitofrontal cortex (OFC): a randomized and sham-controlled exploratory study. J Psychiatr Res. 2015;69:27–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2015.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Razza LB, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis on the effects of transcranial direct current stimulation in depressive episodes. Depress Anxiety. 2020;37(7):594–608. doi: 10.1002/da.23004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang D, et al. Transcranial direct current stimulation reduces seizure frequency in patients with refractory focal epilepsy: a randomized, double-blind, sham-controlled, and three-arm parallel multicenter study. Brain Stimul. 2020;13(1):109–116. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2019.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beretta VS, et al. Transcranial direct current stimulation combined with physical or cognitive training in people with Parkinson’s disease: a systematic review. J Neuroeng Rehabil. 2020;17(1):1–15. doi: 10.1186/s12984-020-00701-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chhatbar PY, et al. Transcranial direct current stimulation post-stroke upper extremity motor recovery studies exhibit a dose–response relationship. Brain Stimul. 2016;9(1):16–26. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2015.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mahmoudi H, et al. Transcranial direct current stimulation: electrode montage in stroke. Disabil Rehabil. 2011;33(15–16):1383–1388. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2010.532283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Caulfield KA, George MS. Optimized APPS-tDCS electrode position, size, and distance doubles the on-target stimulation magnitude in 3000 electric field models. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):20116. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-24618-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Galletta EE, et al. Use of computational modeling to inform tDCS electrode montages for the promotion of language recovery in post-stroke aphasia. Brain Stimul. 2015;8(6):1108–1115. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2015.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Seibt O, et al. The pursuit of DLPFC: non-neuronavigated methods to target the left dorsolateral pre-frontal cortex with symmetric bicephalic transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) Brain Stimul. 2015;8(3):590–602. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2015.01.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee M, et al. What is the optimal anodal electrode position for inducing corticomotor excitability changes in transcranial direct current stimulation? Neurosci Lett. 2015;584:347–350. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2014.10.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xu P, et al. Medial prefrontal cortex in neurological diseases. Physiol Genom. 2019;51(9):432–442. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00006.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Svoboda K, Li N. Neural mechanisms of movement planning: motor cortex and beyond. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2018;49:33–41. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2017.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hasz BM, Redish AD. Dorsomedial prefrontal cortex and hippocampus represent strategic context even while simultaneously changing representation throughout a task session. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2020;171:107215. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2020.107215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhaoping L. A new framework for understanding vision from the perspective of the primary visual cortex. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2019;58:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2019.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Windhoff M, Opitz A, Thielscher A. Electric field calculations in brain stimulation based on finite elements: an optimized processing pipeline for the generation and usage of accurate individual head models. Hum Brain Mapp. 2013;34(4):923–935. doi: 10.1002/hbm.21479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jurcak V, Tsuzuki D, Dan I. 10/20, 10/10, and 10/5 systems revisited: their validity as relative head-surface-based positioning systems. Neuroimage. 2007;34(4):1600–1611. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Angulo-Sherman IN, et al. Effect of tDCS stimulation of motor cortex and cerebellum on EEG classification of motor imagery and sensorimotor band power. J Neuroeng Rehabil. 2017;14(1):31. doi: 10.1186/s12984-017-0242-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Junghofer M, et al. Noninvasive stimulation of the ventromedial prefrontal cortex enhances pleasant scene processing. Cereb Cortex. 2017;27(6):3449–3456. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhx073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martin A, et al. Dissociable roles within the social brain for self–other processing: a HD-tDCS study. Cerebral Cortex. 2018;29:3642. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhy238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Opitz A, et al. Determinants of the electric field during transcranial direct current stimulation. Neuroimage. 2015;109:140–150. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2015.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jung Y-J, Kim J-H, Im C-H. COMETS: a MATLAB toolbox for simulating local electric fields generated by transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) Biomed Eng Lett. 2013;3(1):39–46. doi: 10.1007/s13534-013-0087-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee C, et al. COMETS2: an advanced MATLAB toolbox for the numerical analysis of electric fields generated by transcranial direct current stimulation. J Neurosci Methods. 2017;277:56–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2016.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Madhavan S, Stinear JW. Focal and bidirectional modulation of lower limb motor cortex using anodal transcranial direct current stimulation. Brain Stimul. 2010;3(1):42–50. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nitsche MA, et al. Transcranial direct current stimulation: state of the art 2008. Brain Stimul. 2008;1(3):206–223. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2008.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Willis ML, et al. Anodal tDCS targeting the right orbitofrontal cortex enhances facial expression recognition. Soc Cognit Affect Neurosci. 2015;10(12):1677–1683. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsv057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Antal A, et al. Excitability changes induced in the human primary visual cortex by transcranial direct current stimulation: direct electrophysiological evidence. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45(2):702–707. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-0688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bindman LJ, Lippold O, Redfearn J. The action of brief polarizing currents on the cerebral cortex of the rat (1) during current flow and (2) in the production of long-lasting after-effects. J Physiol. 1964;172(3):369. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1964.sp007425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Koganemaru S, et al. Anodal transcranial patterned stimulation of the motor cortex during gait can induce activity-dependent corticospinal plasticity to alter human gait. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(12):e0208691. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0208691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Martin AK, et al. Causal evidence for task-specific involvement of the dorsomedial prefrontal cortex in human social cognition. Soc Cognit Affect Neurosci. 2017;12(8):1209–1218. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsx063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Accornero N, et al. Visual evoked potentials modulation during direct current cortical polarization. Exp Brain Res. 2007;178(2):261–266. doi: 10.1007/s00221-006-0733-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Viganò A, et al. Transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) of the visual cortex: a proof-of-concept study based on interictal electrophysiological abnormalities in migraine. J Headache Pain. 2013;14(1):23. doi: 10.1186/1129-2377-14-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rawji V, et al. tDCS changes in motor excitability are specific to orientation of current flow. Brain Stimul. 2018;11(2):289–298. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2017.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fox PT, et al. Column-based model of electric field excitation of cerebral cortex. Hum Brain Mapp. 2004;22(1):1–14. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wagner T, et al. Transcranial direct current stimulation: a computer-based human model study. Neuroimage. 2007;35(3):1113–1124. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Suh HS, Lee WH, Kim T-S. Influence of anisotropic conductivity in the skull and white matter on transcranial direct current stimulation via an anatomically realistic finite element head model. Phys Med Biol. 2012;57(21):6961. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/57/21/6961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shahid SS, et al. The value and cost of complexity in predictive modelling: role of tissue anisotropic conductivity and fibre tracts in neuromodulation. J Neural Eng. 2014;11(3):036002. doi: 10.1088/1741-2560/11/3/036002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bai S, et al. A computational modelling study of transcranial direct current stimulation montages used in depression. Neuroimage. 2014;87:332–344. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Laakso I, et al. Inter-subject variability in electric fields of motor cortical tDCS. Brain Stimul. 2015;8(5):906–913. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2015.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Guler S, et al. Optimization of focality and direction in dense electrode array transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) J Neural Eng. 2016;13(3):036020. doi: 10.1088/1741-2560/13/3/036020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fischer D, et al. Multifocal tDCS targeting the resting state motor network increases cortical excitability beyond traditional tDCS targeting unilateral motor cortex. NeuroImage. 2017;157:34–44. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2017.05.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ruffini G, et al. Targeting brain networks with multichannel transcranial current stimulation (tCS) Curr Opin Biomed Eng. 2018;8:70–77. doi: 10.1016/j.cobme.2018.11.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Loo CK, et al. International randomized-controlled trial of transcranial direct current stimulation in depression. Brain Stimul. 2018;11(1):125–133. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2017.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Adenzato M, et al. Transcranial direct current stimulation enhances theory of mind in Parkinson’s disease patients with mild cognitive impairment: a randomized, double-blind, sham-controlled study. Translational Neurodegener. 2019;8(1):1. doi: 10.1186/s40035-018-0141-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mazzoleni S, et al. Effects of transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) combined with wrist robot-assisted rehabilitation on motor recovery in subacute stroke patients: a randomized controlled trial. IEEE Trans Neural Syst Rehabil Eng. 2019;27:1458. doi: 10.1109/TNSRE.2019.2920576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li J, et al. Transcranial stimulation over the medial prefrontal cortex increases money illusion. J Econ Psychol. 2023;99:102665. doi: 10.1016/j.joep.2023.102665. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.van Asseldonk EH, Boonstra TA. Transcranial direct current stimulation of the leg motor cortex enhances coordinated motor output during walking with a large inter-individual variability. Brain Stimul. 2016;9(2):182–190. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2015.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Adams TG, et al. Transcranial direct current stimulation targeting the medial prefrontal cortex modulates functional connectivity and enhances safety learning in obsessive-compulsive disorder: results from two pilot studies. Depress Anxiety. 2022;39(1):37–48. doi: 10.1002/da.23212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Please contact the corresponding author (sangjunlee35@gmail.com) for data requests.