Abstract

Goose down feather has become one of the most important economical products in the goose breeding industry and it provides several essential physiological roles in birds. Therefore, understanding and regulating the development of skin and feather follicles during embryogenesis is critical for avian biology and the poultry industry. MicroRNAs are known to play an important role in controlling gene expression during skin and feather follicle development. In this study, bioinformatics analysis was conducted to select miR-140-y as a potential miRNA involved in skin and feather follicle development and to predict TCF4 as its target gene. This gene was expressed at significant levels during embryonic feather follicle development, as identified by qPCR and Western blot. The targeting relationship was confirmed by a dual-luciferase assay in 293T cells. Then, the miR-140-y/TCF4 function in dermal fibroblast cells was explored. The results showed that miR-140-y could suppress the proliferation of goose embryonic dermal fibroblast cells (GEDFs) by suppressing the activity of some Wingless-types (Wnt) pathway related genes and proliferation marker genes, while miR-140-y inhibition led to the opposite effect. Similarly, the inhibition of the TCF4 gene results in blocking the proliferation of GEDFs by reducing the activity of some Wnt pathway-related genes. Finally, the co-transfection of miR-140-y inhibitor and siRNA-TCF4 results in a rescue of the TCF4 function and an increase of the Wnt signaling pathway and GEDFs proliferation. In conclusion, these results demonstrated that the miR-140-y-TCF4 axis influences the activity of the Wnt signaling pathway and works as a dynamic regulator during skin and feather follicle development.

Key words: feather follicle, miR-140-y, TCF4, Wnt/β-catenin signaling, dermal fibroblast cell

INTRODUCTION

China is widely recognized for its global prominence in goose farming, as a traditional Chinese agricultural practice. Currently, a diverse range of goose breeds is extensively raised for commercial purposes throughout the country (Yan et al., 2023). The Hungarian white goose is characterized by high down production, domesticated from Anser Anser and was introduced to China in 2010 (Song et al., 2022). Goose down feather is known for its important economic role in the goose industry as an essential material for clothing production. It has been widely reported that feather follicles are responsible for feather development during the embryonic stage through a complex interaction of signaling pathways and non-coding RNAs (Chen et al., 2012). First discovered by Lee in 1993, microRNAs (miRNAs) are small noncoding RNAs, single-stranded non-coding RNA molecules, 18 to 25 nt in length that typically exert unique activating or repressing effects by binding to the 3’UTR region of the target mRNAs (Peng et al., 2019; Mi et al., 2020). It is well known that miRNAs are widely distributed in animals, plants and microorganisms. Several studies have shown that miRNA plays a key role in skin wound healing, tissue and organ development, cell proliferation, apoptosis and death (Yi et al., 2006; Yi et al., 2008). So far, various miRNAs have been found in the development of skin tissue. However, there are relatively few studies on goose feather follicle development-related miRNAs.

The Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway plays an important regulatory role in many developmental and disease-related processes (Rim et al., 2022). Recent studies have confirmed that Wnt ligands, Frizzled and LRP5/6 receptors interact to activate β-catenin expression in dermal papilla (DP) cells and Axin2 and LEF1 transcription factors confirm the function of β-catenin in DP cells by activating important transcription factors related to hair growth (Rajendran et al., 2020). Also, several reports have confirmed the important role of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway in promoting hair growth (Choi, 2020). The transcription factor 4 gene (TCF4) is a core nuclear transcription factor of the Wnt signaling pathway. It belongs to the TCF gene family and has dual regulatory functions of activation and repression in transcriptional regulation (Salinas et al., 2008). In the absence of Wnt signal stimulation, TCF4 specifically binds to Wnt target gene promoters and inhibits the expression of target genes. When the Wnt pathway is stimulated, β-catenin accumulates in large amounts in the cell and reaches a certain concentration, enters the nucleus, forms a complex with TCF4, exerts its function and activates transcription (Shiina et al., 2003; Lee et al., 2020).

Based on preliminary studies conducted by our research team on feather follicles, 5 key developmental stages were selected for this study: Embryonic d 10 (E10), d 13 (E13), d 18 (E18), d 23 (E23) and d 28 (E28), to cover all the important moments of embryonic skin and feather follicles of goose (Mabrouk et al., 2022; Song et al., 2022).

In this study, Hungarian white goose was used as the research object. The development of goose embryonic skin and feather follicles was observed through HE staining, and high-throughput technology and deep sequencing analysis were utilized to select the differentially expressed microRNAs from 5 important embryonic developmental stages (E10, E13, E18, E23, and E28). Further, the miR-140-y and TCF4 gene were screened for functional analysis in goose embryonic dermal fibroblast cells and to verify the regulatory mechanism between the TCF4 and miR-140-y, focusing on the Wnt signaling pathway. In summary, our study provides a critical insight in the regulatory function of the miR-140-y/ TCF4 axis in GEDFs proliferation and reveals a basic for miR-140-y/ TCF4/ Wnt signaling pathway regulatory mechanism during the feather follicle development of Hungarian white goose.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ethics Statement

All experiments involving animals were authorized by the Animal Health Care Committee of the Animal Science and Technology College of Jilin Agricultural University (Approval No. GR (J) 18-003).

Experimental Animals and Sample Collection

A total of 200 Hungarian white goose eggs, obtained from the goose breeding base of Jilin Agricultural University, were selected as the research subjects, in which 60 eggs were used for staining experiments, 80 to collect cryopreserved samples from 5 important stage of feather follicle development (E10, E13, E18, E23, and E28) and 60 were used for the culture and isolation of goose embryonic dermal fibroblast cells. The dorsal skin of the goose embryo was used for the sampling. Some samples were stored at -80°C for further experiments and others were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (DEPC treatment), dehydrated and embedded after 48 h with common method for histological staining.

Hematoxylin and Eosin Staining

The paraffin embedding and sectioning of tissues were performed according to the standard method. For the Hematoxylin and Eosin (HE) staining, the sections were placed in xylene for dewaxing twice for 15 min each time. Then soak in 100, 90, 80, and 70% ethanol solutions for 5 min each. The staining was carried out according to the HE staining kit's instructions. Finally, the slides were sealed with neutral resin glue and observed under the Nicon-300 light microscope to detect the morphological changes in feather follicles development (Nicon, Tokyo, Japan).

MicroRNA Library Creation and Sequencing

Total RNA was extracted from the sample by TRIzol reagent Kit (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) or CTAB method. The RNAs in a size range of 18 to 30 nt were selected by polyacrylamide gel (PAGE) electrophoresis to recover small RNA. The 3′ adapter and the 5′ adapter were ligated respectively, and then the small RNA connected to the 2 adapters was reverse transcribed and PCR amplified, and finally the band of about 140 bp was recovered and purified using PAGE gel, dissolved in EB solution, and the library construction was completed. The constructed libraries were tested for quality and yield and sequenced using Agilent 2100 and ABI StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR System (Life Technologies).

Quantification and Analysis of Differentially Expressed miRNAs

MiRNAs differential expression analysis was performed by the edgeR package (available online: http://www.r-project.org/) between 2 samples. MiRNAs with a false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.05 and a |Fold Change| ≥2 were considered as significantly differentially expressed miRNAs (DE miRNAs). DE miRNAs were then subjected to enrichment analysis of GO functions and KEGG pathways. The GO terms and KEGG pathways with P < 0.05 were defined as significantly enriched terms and pathways.

Functional Enrichment Analysis

The miRNA target genes were mapped to each term of the GO database (available online: http://www.geneontology.org/) and the number of miRNA target genes in each term was calculated, to determine the number of genes associated with each term so as to obtain the miRNA target gene list with a certain GO function. Hypergeometric tests were then applied to identify GO entries that were significantly enriched in the miRNA target genes compared to the background. Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) is the primary public database on the Pathway (available online: http://www.genome.jp/kegg). However, a hypergeometric test was applied to find the pathways that are significantly enriched in the miRNA target genes compared to the entire background. Pathway enrichment analysis can identify the most important biochemical metabolism pathways and signal transduction pathways involved in miRNA target genes. The criterion for statistical significance was FDR < 0.05.

Real-Time qPCR Validation

A total of 9 DEmiRNAs were selected for quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) validation. The samples of qRT-PCR validation came from the RNA remaining from sequencing. For miRNAs expression, RNA extraction from tissues and cells was performed by MiPure Cell/Tissue miRNA Kit (Cat# RC201) produced by Vazyme according to the instructions, miRNA 1st Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Cat# MR101-01) kit produced by Transgen was used for reverse transcription of miRNA by stem-loop method and miRNA Universal SYBR qPCR Master Mix (MQ101-01) produced by Vazyme was used for the RT-qPCR with U6 as the internal reference gene. For mRNA expression, DNA/RNA Extraction Kit (Cat# RM2020-01) produced by Vazyme was used to extract total RNA from tissues and cells according to the instructions, the RNA reverse transcription was performed using TransScript One-Step RT-PCR SuperMix (Cat# AT411-02) produced by Transgen and for the RT-qPCR, PerfectStart Green qPCR SuperMix (AQ601-02-V2) produced by Transgen was utilized, with GAPDH and β-actin were the internal controls. Primers are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

The primer information of qRT-PCR.

| Gene/miRNA | Species | Primer Sequence (5’–3’) |

|---|---|---|

| miR-140-y | Anser Anser | RT:GTCGTATCCAGTGCAGGGTCCGAGGTATTCGCACTGGATACGACGTCCGT |

| F:CGCGACCACAGGGAGAACC | ||

| miR-11987-z | Anser Anser | RT:GTCGTATCCAGTGCAGGGTCCGAGGTATTCGCACTGGATACGACTCCCCG |

| F:CGCGCGCGAGAGGAAAC | ||

| miR-499-x | Anser Anser | RT:GTCGTATCCAGTGCAGGGTCCGAGGTATTCGCACTGGATACGACCTCCTC |

| F: GCGCGCGCGCGAAGAC | ||

| miR-27-z | Anser Anser | RT:GTCGTATCCAGTGCAGGGTCCGAGGTATTCGCACTGGATACGACCGCGGC |

| F: CGCGCGCACAGGGCAA | ||

| miR-184-y | Anser Anser | RT:GTCGTATCCAGTGCAGGGTCCGAGGTATTCGCACTGGATACGACCCCTTT |

| F: CGCGGGACGGAGAACG | ||

| miR-455-x | Anser Anser | RT:GTCGTATCCAGTGCAGGGTCCGAGGTATTCGCACTGGATACGACCGTGTG |

| F: GCGCGCGAGGCCCGGA | ||

| miR-145-x | Anser Anser | RT:GTCGTATCCAGTGCAGGGTCCGAGGTATTCGCACTGGATACGACGGGTTC |

| F: CGCGCGGCCAGCCCAG | ||

| miR-143-y | Anser Anser | RT: GTCGTATCCAGTGCAGGGTCCGAGGTATTCGCACTGGATACGACGGCTCG |

| F: CGCGCGGAGAGAAGCA | ||

| miR-19-z | Anser Anser | RT:GTCGTATCCAGTGCAGGGTCCGAGGTATTCGCACTGGATACGACGTTTTG |

| F:GCGCGCGGGCAAACAG | ||

| U6 | Anser Anser | F:CTCGCTTCGGCAGCACATATACTA |

| R:CGAATTTGCGTGTCATCCTTGC | ||

| TCF4 | Anser Anser | F: ACCACTGTGCCTTCCAATGT |

| R: ACGCCTCACTGCACACTATT | ||

| Axin2 | Anser Anser | F:TGAGGGTTACAGCGAACGTC |

| R:GACATGGAGTCGTCCGTCAG | ||

| Cyclin D3 | Anser Anser | F:GACGGCGGCGAAACGA |

| R:TGAGGACAGGTAGCGATCCA | ||

| PCNA | Anser Anser | F:CAGCCATATTGGTGATGCAG |

| R:GGTCAGTTGGACTGGCTCAT | ||

| LEF1 | Anser Anser | F:CACAGAACCTGCGATTT |

| R:CCACTGGGAGTCCGTAA | ||

| GAPDH | Anser Anser | F:CGTGTGGTGGACTTGATGGT |

| R:AAGGGAACAGAACTGGCCTC |

Western Blotting

Total protein was extracted using RIPA lysis buffer containing protease inhibitors and phosphatase inhibitors and protein concentration was determined by the Omni-Easy Instant BCA Protein Assay Kit (Cat# ZJ102) produced by Epizyme. Protein samples were boiled in 5 × SDS protein loading buffer (Solarbio, Beijing, China) at 95°C for 10 min. A 5 µg/µL total protein concentration was electrophoresed on 8% SDS- PAGE, for separating the proteins in the fractions and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (PVDF). Blots were detected by incubating with anti-Axin2 (Cat# DF6978, Affinity, San Francisco, CA), anti-TCF4 (Cat# DF6275, Affinity, San Francisco, CA), anti-β-catenin (Cat# AF6266, Affinity, San Francisco, CA), anti-LEF1(Cat# DF7570, Affinity, San Francisco, CA), anti-Cyclin D3 (Cat# AF6251, Affinity, San Francisco, CA) and anti-PCNA (Cat# AF0239, Affinity, San Francisco, CA) at 4°C overnight, followed by GAPDH rabbit monoclonal antibody (Cat# AT003, ABP Biosciences, Wuhan, Hubei, China). Finally, immunoreactive bands were then incubated with the goat anti-rabbit IgG (H + L)/HRP antibody (Bioworld Technology, Inc., St. Louis Park, MN) for 2 h at room temperature and were detected with the ECL Test Kit (Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany) by chemiluminescence under a Bio-Rad imaging system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA).

Cell Culture and Transfection

Goose embryonic dermal fibroblast cells (GEDFs) were isolated from the dorsal skin of the Hungarian white goose embryos at E15 and cultured in a complete culture medium (DMEM medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum). Cells were then incubated in a 37°C, 5% CO2 incubator and the medium was changed each 3 d. For further transfection experiments, the cells were inoculated in 6-well plates. MiRNA mimics, mimics NC, inhibitor, inhibitor NC and siRNA were designed by ComateBio. Synthetic sequence information is shown in Table. 2. The transfection was performed when the cells reached 70% confluence using the GenMute siRNA transfection reagent (SignaGen Laboratories) following the manufacture instructions.

Table 2.

RNA oligonucleotide sequence information.

| Name | Sequences (5’-3’) |

|---|---|

| miR-140-y mimics | UCAGGCACCAAGAUGGGACACCA (Sense) |

| UGGUGUCCCAUCUUGGUGCCUGA (antisense) | |

| miR-140-y mimics NC | UUCUCCGAACGAGUCACGUTT |

| miR-140-y inhibitor | UGGUGUCCCAUCUUGGUGCCUGA |

| miR-140-y inhibitor NC | ACGUGACUCGUUCGGAGAATT |

| siRNA-TCF4 | GACCCUGACGUUGCUUCUCAUTT (sense) |

| AUGAGAAGCAACGUCAGGGUCTT (antisense) | |

| siRNA-NC | ACGUGACUCGUUCGGAGAATT |

Dual Luciferase Reporter Assay

The design and synthesis of the dual-luciferase reporter gene vectors design and synthesis were carried out GenePharma (Shanghai, China). The TCF4-wild-type (TCF4-WT) and TCF4-mutation (TCF4-MT) were synthesized to show the 3’UTR mutation and wild-type of the TCF4 gene. The vectors and the miRNA mimics were co-transfected into human embryonic kidney 293 cells (HEK293T) prepared in advance for transfection into 96-well plates, with Lipofectamine 2,000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and 4 assay groups were obtained by combining NC mimics, miR-140-y, TCF4-MT, and TCF4-WT vectors, with 3 biological replicates in each group. The TCF4-WT plasmid concentration was 0.3861 μg/μl, and the TCF4-MT plasmid concentration was 0.4214 μg/μL. After 48 h of incubation, firefly and Renilla luciferase activities were measured using a Dual Luciferase Reporter Assay Kit (Promega, Madison, WI).

EdU Cell Proliferation

Cells were seeded in 6-well plates at a density of 1 × 106, with a total of 8 groups with 3 replicates. The experiment was performed according to the instructions of EdU Imaging Kits (Cy3) (Cat# K075, APExBIO), the prepared EDU reagent was added to the cell culture medium and incubated for 9 h at 37°C and 5% CO2, after that, the medium was removed, and fixation solution was added for 10 min in the dark, followed by permeabilization solution for 10 min, after staining the nuclei. A fluorescence microscope was used for observation.

Data Analysis

The cq value generated by the RT-qPCR experiment was used to calculate the relative expression of the gene using the 2−ΔΔCT method. The protein bands generated by the western blotting experiment were analyzed using ImageJ software. ANOVA single-factor analysis of variance was used to analyze the qPCR and western blotting results for the analysis performed on the skin tissues and 2-tailed student's test was used to compare the differences between 2 groups. The results are expressed as average Mean ± SEM. Differences between data were considered significant for p < 0.05 and extremely significant for p < 0.01.

RESULTS

Morphological Observations of Skin and Feather Follicles at Different Embryonic Stages

To further investigate the morphological changes in skin and feather follicles in Hungarian white goose at 5 key developmental stages (E10, E13, E18, E23, and E28), Hematoxylin and Eosin staining method was used. As shown in Figure 1, the epidermis of the dorsal skin descends and forms tiny protrusions at E10. By E13, punctate plumage structures and skin ridge were emerged on the dorsal surface and at E18, which is related to the primary stage of feather follicle formation, feather buds were clearly seen in some place of the skin. At E23, secondary feather follicles begin to develop, primary and secondary feather follicles were observed simultaneously. As the embryo continues to develop, the size of primary feather follicles continues to change and secondary feather follicles were develop with an incensement with time of skin thickness at E28.

Figure 1.

The pattern of feather follicle development in the Hungarian white goose at various embryonic stages. The vertical sections depict time magnification, while the horizontal lines represent time gradient. The first column: Skin and feather follicle development under 40 times magnification, bar = 200 μm; the second column: Skin and feather follicle development under 100 times magnification, bar = 100 μm. Red triangle: tiny bumps, yellow triangle: bulbous protuberance, green triangle: initial feather follicle structure, blue triangle: secondary feather follicle, FBR: feather barb ridges, DP: dermal papilla, BL: basal layer, IRS: inner root sheath, ORS: outer root sheath.

Differentially Expressed miRNAs at Different Developmental Stages

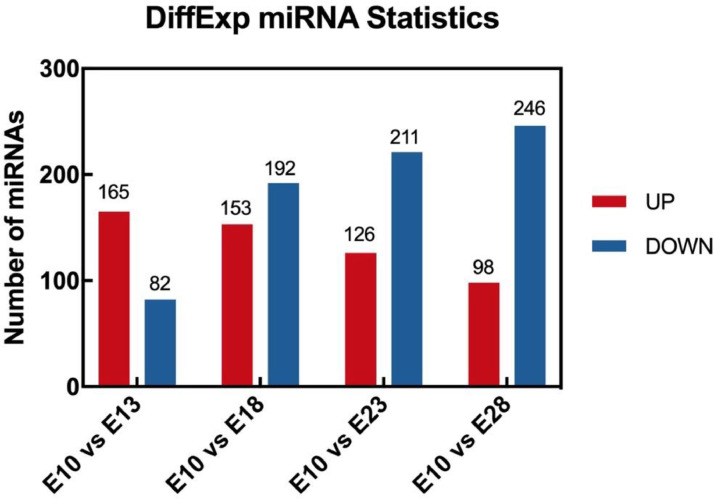

The data sequence was established at 5 embryonic developmental stages (E10, E13, E18, E23, and E28) and these stages were chosen to cover the whole initiation and development process of feather follicles. In total, 4 sets of data were obtained (E10 vs. E13, E10 vs. E18, E10 vs. E23, and E10 vs. E28). The results of the miRNA expression (Figure 2) showed that the number of miRNA expressed was different among the groups. In total, 247 differentially expressed miRNAs in the E10 vs. E13 group of which 165 were up regulated and 82 were down regulated. For the E10 vs. E18, 345 DE miRNAs were observed (153 upregulated and 192 down regulated). Also, 337 DE miRNAs were identified in E10 vs. E23 (126 upregulated and 211 down regulated), 344 in E10 vs. E28 (98 upregulated and 246 down regulated). As it can be noticed the E10 vs. E18 group has the highest number of the DE miRNAs. It is speculated that the occurrence and development of goose feather follicle will start in the first 10 to 18 d and that miRNA is involved in the regulation of the morphogenesis and development of goose feather follicles.

Figure 2.

Differentially expression miRNAs in different groups. The red column represents unregulated miRNA and the blue column represents down-regulated.

GO Enrichment and KEGG Pathway Analysis of the Differentially Expressed miRNAs

GO and KEGG enrichment analyses were performed to further elucidate the roles and pathways in which the DE miRNAs were involved. In the GO analysis, the DE miRNAs were categorized into 3 principal GO groups based on the GO annotation: Biological process (metabolic process, cell process, single organism process and cellular compartment organization), Cellular component (cell, intracellular part, organelle, cytoplasm and cytosol) and Molecular function (binding, RNA binding, protein binding and structural molecule activity) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

GO analysis of differentially expressed miRNAs in skin and feather follicles development of the Hungarian white goose. (A–D) shows the comparisons groups of E13, E18, E23, and E28 vs. E10. The results are regrouped in 3 groups: Biological process, cellular component and molecular function. The Y-axis illustrates the percentage of miRNAs, while the X-axis shows the second level term of the gene ontology.

The KEGG annotation serves to understand the alterations in signaling pathways (Figure 4). We concentrated on the top twenty differential pathways that were enriched for each group of differential genes and, similar to the GO analysis, we observed some pathways that were found in all sets of results, particularly the metabolic pathway, the p53 signaling pathway and the mRNA surveillance pathway, while the cell cycle pathway was found in all groups except for the E10 vs. E13 comparison group, suggesting that some genes in this pathway were modified in the skin that developed in the late embryonic stages (E18, E23 and E28) compared to E18, which could be associated with larger modifications in the biological characteristics that occur in the latest embryonic development stages as the skin develop.

Figure 4.

KEGG analysis of differentially expressed miRNAs in skin and feather follicle development in Hungarian white goose. (A–D) represents the comparison group of E13, E18, E23, and E28 with E10. The abscissa shows the number of enriched miRNAs and the ordinates illustrate signal pathways.

Validation of DE miRNAs Expression Trend

To validate the miRNA-seq results, 9 miRNAs (miR-140-y, miR-11987-z, miR-19-z, miR-143-y, miR-145-x, miR-184-y, miR-499-x, miR-27-z, and miR-455-x) were selected and their relative expression in the embryonic skin and feather follicles was performed by RT-qPCR. These qPCR results were strongly correlated with the sequencing results, as shown in Figure 5, demonstrating the dependability and the reliability of our miRNA-seq data.

Figure 5.

RT–qPCR verification of the miRNA-seq data using 9 selected miRNAs. The x-axis represents embryonic developmental stages; the y-axis represents the relative expression. The results are presented as the means ± SEM of 3 replicates.

TCF4 Gene a Potential Target of miR-140-y

The TCF4 gene was selected among the potential target genes of miR-140-y following the miRNA-seq data results. So, to further confirm the targeting relationship, dual-luciferase reporter gene assay was performed to detect the luciferase activity after transfection for 12 h in 293T cells. A wild type or mutant-TCF4-3′UTR plasmids were co-transfected with miR-140-y oligos into 293T cells. The relative luciferase activity showed that no significant difference between the MT group (miR-140-y + TCF4-3′UTR mutation type) and the control group (p > 0.05), indicating that the mutation was successful. While a significantly lower luciferase activity was observed in the WT group (miR-140-y + TCF4-3′UTR wild type) compared with the control group (p < 0.001), suggesting that miR-140-y significantly reduced luciferase expression of TCF4-3′UTR-WT relative to the NC group, indicating a binding interaction between the 2 in this experiment and establishing the targeting relationship (Figures 6A–C). Further, to confirm the relationship between miR-140-y and TCF4, we overexpressed and knockdown miR-140-y in GEDF cells. First, the efficiency of the miR-140-y mimic and inhibitor was tested using qPCR and the mimic and inhibitor groups were shown to be significantly different compared with the NC groups (p < 0.01) (Figure 6D). Then, the TCF4 mRNA and protein expressions were also determined by qPCR and western blot. The results demonstrated that miR-140-y mimic resulted in a highly significant reduce in TCF4 mRNA and protein expression (p < 0.01), while miR-140-y inhibitor resulted in a highly significant increase in TCF4 mRNA and protein expression (p < 0.01) in GEDFs, suggesting that the miR-140-y mimic can suppress the expression of TCF4 and that the miR-140-y inhibitor could elevate its expression (Figures 6E–6G).

Figure 6.

miR-140-y directly regulates target gene TCF4. (A) RNAhybrid analysis demonstrates the putative target site between miR-140-y and TCF4 mRNA 3′-UTR. (B) Binding site and mutation site of miR-140-y and TCF4. (C) Luciferase assay in GEDFs cells co-transfected with pMir-TCF4 -3′-UTR-WT and miR-140-y mimics and pMir-TCF4 3′-UTR MT and miR-140-y mimics. (D) Changes in the expression level of miR-140-y in GEDFs after transfection with miR-140-y mimics and inhibitors. (E) Overexpression of miR-140-y can reduce the mRNA expression level of TCF4 in GEDFs cells; knockdown of miR-140-y increases the mRNA expression level of TCF4 in GEDFs cells. (F) Western blot of TCF4 in GEDFs after transfection with miR-140-y mimics and inhibitors. (G) Overexpression of miR-140-y can reduce the protein expression level of TCF4 in GEDFs cells; knockdown of miR-140-y Low increases the protein expression level of TCF4 in GEDFs cells. The data were shown as mean ± SEM, n = 3, ** p < 0.01.

TCF4 Gene Expression Trend in Dorsal Skin and Feather Follicles of Hungarian White Goose During Embryonic Stages

RT-qPCR and Western Blot were used to measure the expression of TCF4 at 5 important embryonic developmental stages of feather follicles of Hungarian white goose. The results showed that the expression trends of TCF4 gene mRNA levels and protein levels were similar, showing an increase-decrease-increase-decreasing trend, TCF4 has the highest expression level at E13 and the lowest at E28. Among them, the TCF4 gene mRNA expression levels at E10, E13, and E23 are significantly different from those at E18 and E28 (p < 0.01) (Figure 7B) and TCF4 protein expression levels were extremely significantly different at the 5 time points (p < 0.01) (Figures 7A and 7C).

Figure 7.

The expression trend of TCF4 gene in skin and feather follicles of Hungarian white goose at 5 key developmental stages. (A) Western blot band diagram of TCF4 and the internal reference GAPDH. (B) Expression of TCF4 gene mRNA in feather follicles of the dorsal skin of Hungarian white goose embryos. (C) The expression level of TCF4 protein in the feather follicle of the dorsal skin of the Hungarian white goose.

Overexpression of miR-140-y Suppress the Expression of Wnt Signaling Pathway Related Genes and Inhibits the Proliferation of Dermal Fibroblast Cells

To further explore the function of miR-140-y overexpression in the proliferation of dermal fibroblasts cells and in the expression of Wnt signaling pathway related genes, the cells were transfected with the mimics NC and miR-140-y mimics. RNA extraction for qPCR was performed 24 h after transfection and the protein extraction for Western blot was done 72h after transfection. We noticed that miR-140-y overexpression significantly reduce the mRNA expression of Axin 2, β-catenin and LEF1, but in contrast the expression of Cyclin D3 was increased (Figure 8A). Further, the overexpression significantly increases the protein expression of Axin 2 and cyclin D3 but significantly repressed β-catenin and LEF1 expression (Figures 8B and 8C). Next, the EdU cell proliferation assays were further utilized to investigate the role of miR-140-y overexpression in dermal fibroblasts cells proliferation. The percentage of EdU-positive stem cells significantly decreased with miR-140-y overexpression (in the group transfected with miR-140-y mimics compared with NC group) (Figures 8D and 8E). Additionally, the mRNA and protein expression of PCNA (a proliferation marker gene) was significantly decreased by miR-140-y overexpression (Figures 8F–8H). In general, these findings suggested that miR-140-y overexpression could inhibit dermal fibroblasts cells proliferation through suppressing the activity of some Wnt pathway related genes and proliferation marker genes.

Figure 8.

miR-140-y overexpression suppresses the expression of Wnt pathway related genes and inhibits the proliferation of dermal fibroblast cells. (A) Relative mRNA expression of Wnt pathway related genes was measured in dermal fibroblast cells 24 h after transfection with NC or miR-140-y mimics by qPCR. (B–C) Relative protein expression of Wnt pathway related genes was measured in dermal fibroblast cells 72 h after transfection with NC or miR-140-y mimics by Western blot. (D–E) Representative observations of the EdU assay of dermal fibroblast cells after transfection with NC and miR-140-y mimics (Bars: 100 µm). Red illustrate the EdU staining and blue display the cell nuclei stained with Hoechst 33342. (F) The mRNA expression of proliferation related gene (PCNA). (G-H) Protein expression level of proliferation related gene (PCNA). The data were shown as mean ± SEM, n = 3, * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01.

miR-140-y Inhibition Promotes the Expression of Wnt Signaling Pathway Related Genes and Facilitates Dermal Fibroblast Cells Proliferation

Similar to miR-140-y overexpression, dermal fibroblast cells were transfected with Inhibitor-NC and miR-140-y inhibitor, RNA extraction for qPCR and protein extraction for Western blot were performed 24h and 72h after transfection, respectively. We noticed that miR-140-y knockdown significantly increased the mRNA expression of Axin 2, β-catenin and LEF1, but suppressed the cyclin D3 expression (Figure 9A). Western blot assay strengthened that miR-140-y inhibition significantly increased the protein expression of Axin 2 and cyclin D3 and decreased β-catenin and LEF1 expression (Figures 9B and 9C). Furthermore, the percentage of EdU-positive stem cells significantly increased with the miR-140-y reducing, in the EdU cell proliferation assays, indicating that the absence of miR-140-y promotes the cells proliferation (in the group transfected with miR-140-y inhibitor compared with Inhibitor-NC group) (Figures 9D and 9E). To further confirm this result, the mRNA and protein expression of PCNA gene (a proliferation marker gene) were tested in the transfected cells and the results showed that miR-140-y inhibition significantly increase mRNA and protein expression of this gene (Figures 9F–H). In conclusion, these results indicated that miR-140-y knockdown may promote dermal fibroblast cells proliferation by activating the expression of some Wnt pathway related genes.

Figure 9.

Knockdown of miR-140-y promotes the expression of Wnt pathway related genes and facilitates the proliferation of dermal fibroblast cells. (A) Relative mRNA expression of Wnt pathway related genes was measured in dermal fibroblast cells 24h after transfection with Inhibitor-NC or miR-140-y inhibitor by qPCR. (B-C) Relative protein expression of Wnt pathway related genes was measured in dermal fibroblast cells 72h after transfection with Inhibitor-NC or miR-140-y inhibitor by Western blot. (D-E) Representative observations of the EdU assay of dermal fibroblast cells after transfection with Inhibitor-NC and miR-140-y inhibitor (Bars: 100 µm). Red illustrate the EdU staining and blue display the cell nuclei stained with Hoechst 33342. (F) The mRNA expression of proliferation related gene (PCNA). (G-H) Protein expression level of proliferation related gene (PCNA). The data were shown as mean ± SEM, n = 3, ** P < 0.01.

Inhibition of TCF4 influences Wnt signaling pathway and inhibits the proliferation of dermal fibroblast cells

In order to explore the function of TCF4 inhibition in the proliferation of GEDFs and the expression of genes related to the Wnt signaling pathway, siRNA-TCF4 or si-NC was transfected. RNA extraction for qPCR and protein extraction for Western blot were performed 24 h and 72 h after transfection. We noticed that TCF4 mRNA and protein expression were significantly reduced after inhibiting with TCF4 (Figure 10). In our study, we determined the mechanism of Wnt signaling pathway in goose embryonic dermal fibroblasts by inhibiting TCF4, including regulating the expression of skin development-related genes (Axin2, β-catenin, LEF1) and its downstream gene (cyclin D3). Results showed that siRNA-TCF4 significantly reduced the mRNA expression of Axin2 and β-catenin, but the expression of LEF1 and cyclin D3 increased (Figure 11A). In addition, siRNA-TCF4 significantly increased the protein expression of cyclin D3, but significantly inhibited the protein expression of Axin2, β-catenin and LEF1 (Figures 11B and 11C). Afterwards, EdU cell proliferation assay was used to study the effect of siRNA-TCF4 on the proliferation of goose embryo dermal fibroblasts. Compared with the NC group, the percentage of EdU-positive stem cells in the siRNA-TCF4 group decreased significantly (Figures 11D and 11E). In addition, siRNA-TCF4 significantly reduced the mRNA and protein expression of PCNA (proliferation marker gene) (Figures 11F–11H). These findings indicate that siRNA-TCF4 can inhibit goose dermal fibroblasts by inhibiting the activity of some Wnt pathway-related genes and proliferation marker genes.

Figure 10.

Effect of TCF4 inhibition on TCF expression in dermal fibroblast cells. (A) Relative mRNA expression of the TCF4 gene was detected 24 h after transfection with siRNA-TCF4 or si-NC. (B–C) Relative protein expression of TCF4 measured by western blot 72 h after transfection with siRNA-TCF4 or si-NC. The data were shown as mean ± SEM, n = 3, ** P < 0.01.

Figure 11.

siRNA-TCF4 restrain the expression of Wnt pathway related genes and inhibits the proliferation of dermal fibroblast cells. (A) Relative mRNA expression of Wnt pathway related genes was measured in goose dermal fibroblast cells 24 h after transfection with siRNA-TCF4 or si-NC by qPCR. (B–C) Relative protein expression of Wnt pathway related genes was measured in goose dermal fibroblast cells 72h after transfection with siRNA-TCF4 or si-NC by Western blot. (D–E) Representative observations of the EdU assay of dermal fibroblast cells after transfection with siRNA-TCF4 or si-NC (Bars: 100 µm). Red illustrate the EdU staining and blue display the cell nuclei stained with Hoechst 33342. (F) The mRNA expression of proliferation related gene (PCNA). (G–H) Protein expression level of proliferation related gene (PCNA). The results were shown as mean ± SEM, n = 3, * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01.

Adding miR-140-y Inhibitor can Rescue the Expression of Wnt Pathway Related Genes and the Proliferation of Goose Embryo Dermal Fibroblasts Caused by siRNA-TCF4

SiRNA-TCF4 and miR-140-y inhibitor were co-transfected into goose embryonic dermal fibroblasts. No significant difference was found between the NC group and the miR-140-y inhibitor + siRNA-TCF4 group for the target TCF4, Wnt pathway relation genes (Axin2, β-catenin and LEF1), downstream gene cyclin D3, and proliferation marker gene PCNA (Figures 12A–C). In addition, in the EdU cell proliferation assay, there was no significant difference in the percentage of positive stem cells between the NC group and the miR-140-y inhibitor+siRNA-TCF4 group (Figures 12D and 12E). These results showed that adding miR-140-y inhibitor can rescue the decrease in TCF4 expression, inhibition of Wnt signaling pathway and proliferation of goose embryonic dermal fibroblasts caused by the addition of siRNA-TCF4.

Figure 12.

Effect of miR-140-y inhibitor and siRNA-TCF4 co-transfection on TCF4 expression, Wnt signaling pathway related genes and cell proliferation. (A) Relative mRNA expression of Wnt pathway related genes was measured in goose embryonic dermal fibroblast cells 24h after co-transfection with miR-140-y inhibitor and siRNA-TCF4 by qPCR. (B–C) Relative protein expression of Wnt pathway related genes was measured in goose embryonic dermal fibroblast cells 72h after co-transfection with miR-140-y inhibitor and siRNA-TCF4 by Western blot. (D–E) Representative observations of the EdU assay of goose embryonic dermal fibroblast cells after co-transfection with miR-140-y inhibitor and siRNA-TCF4 (Bars: 100 µm). Red illustrate the EdU staining and blue display the cell nuclei stained with Hoechst 33342. The results were shown as mean ± SEM, n=3, ns: no significant difference, P > 0.05.

DISCUSSION

Hungarian white goose is a unique goose breed with white gray plumage, known for its high-quality feathers. Despites its down importance in goose industry economy, the molecular mechanisms underlying feather follicles formation and development of this breed remains unclear. Recently, several studies have found that miRNAs are mainly involved in hair/feather development, especially at the embryonic stages (Zhang et al., 2013; Ding et al., 2020; Feng et al., 2021). In this study, high-throughput sequencing of skin and feather follicles from the Hungarian white goose at 5 important embryonic developmental stages (E10, E13, E18, E13 and E28) was conducted. Form the sequencing results, we screened a total of 1,273 differentially expressed miRNAs and we choose 9 of them for qPCR verification. We speculated that these miRNAs may have a crucial role in the development and formation of feather follicles and influence the regulation of genes and pathways involved in this process. Several previous reports have found that some of these miRNAs have been involved in the regulation of skin and hair/feather growth in animals. Numerous studies screened various miRNAs in duck and Pekin duck skin and feather follicles, including miR-140, miR-145, miR-19, miR-499 and miR-27 (Chen et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2013). Also, Gao et al. (2017) reported a total of 14 miRNAs involved in the regulation of Hu sheep wool development among which miR-143 family were highly expressed. Moreover, several studies on mice, chicken, duck, goat and sheep screened various miRNAs related to skin and hair/feather follicle development counting miR-184, miR-455 families (Nagosa et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2007; Quan et al., 2017). In our research, we also detected some new differentially expressed miRNAs that were not reported with their involvement in hair or feather follicle development, such as miR-11987. The RT-qPCR results showed that the expression of miR-140-y was higher compared to other miRNAs. As a result, we selected miR-140-y to further investigate its function and impact on the embryonic dermal fibroblast cells proliferation and the Wnt pathway activity. MiR-140-y is known to play a critical function in skin and hair follicle formation, growth and cycling in mammals (Andl et al., 2006; Li et al., 2013). Furthermore, Chen et al. (2017) also found that miR-140 was highly expressed in skin and feather follicles of the Pekin duck (Anas Anas), especially at the early embryonic stages, conforming its role in controlling feather morphogenesis during the embryonic periods. To date, there has been a significant progress in comprehending the molecular process underpinning hair follicle control in humans and model animals such as mice and rats and miRNAs properties are greatly convenient to better understand the associated molecular mechanisms in animals. In our research, the overexpression of miR-140-y inhibits the proliferation dermal fibroblast cells and suppresses the activity of Wnt signaling pathway, while its inhibition led to the opposite effect. Additionally, miR-140-y overexpression or inhibition led to change in the expression of its target gene, the TCF4. Together, these results speculate that miR-140-y negatively influences the development of feather follicles via blocking the activity of Wnt signaling pathway by targeting the TCF4 gene. Few studies have reported the function of miR-140-y in skin and hair/feather follicle development, but it is widely known that miR-140 family enhance the proliferation in neural stem cells (Tseng et al., 2019), dental pulp stem cells (Sun et al., 2017) and chondrocytes (Tao et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2018). Moreover, a study by Chen at al. (2020) showed that the overexpression of miR-140-5p in human hair follicles (HFs) promoted the proliferation of outer root sheath cell (ORSC) and hair matrix cell (MxCs), which significantly promotes the growth of hair follicles. These findings were in contrast with our results while investigating the role of miR-140-y in dermal fibroblast cells.

It has been widely reported that miRNAs generally accomplish their biological roles by interacting with their target genes. So functional and pathways enrichment analysis for the target genes of the DE miRNAs could further aids to conclude miRNAs roles. In the current research, KEGG annotation suggested that most of the target genes of the DE miRNAs were significantly enhanced in the p53 signaling pathway, metabolic pathways and Wnt pathway and these pathways are recognized to play a vital role in controlling the growth of hair/feather follicles and in cell growth mechanisms. To examine the regulatory connection between miRNAs and mRNAs in the feather follicle formation process, we choose the TCF4 gene as a potential target gene of miR-140-y and the Dual luciferase reporter assay results confirmed their targeting relationship. The TCF4 is a transcription factor, which regulates other genes expression, influencing several cell development events, including cell differentiation and proliferation and plays a vital role in numerous biological processes, involving hair and feather development. Feather follicle formation is promoted by the interaction of several signaling pathways, including Wnt, Bmp, Shh, and Notch (Yu et al., 2004; Hu et al., 2020). However, the Wingless-types/beta-catenin (Wnt/β-catenin) signaling was reported to be the most important pathway in hair and feather follicle development and it's known to regulate the number, size, growth and regeneration of hair follicles (Ma et al., 2016). Also, this pathway is involved in hair/feather follicle induction mostly through the binding of β-catenin to members of the lymphoid enhancer factor (LEF) or the T cell factor (TCF) family and modulate the downstream target genes expression (Clevers et al., 2012; Yu et al., 2017). It's known that TCF4 gene is associated with the Wnt signaling pathway. Several studies have shown that the TCF4, as a key gene of the canonical Wnt signaling pathway, interfered with β-catenin and contribute to hair follicle development and regulation. A study by Xiong et al. (2014) demonstrated that TCF4 is closely related to dermal papilla cells proliferation, as the overexpression of this gene promote the dermal papilla cells proliferation and the secretory activity of DPC. Similarly, we noticed that the inhibition of this gene by siRNA transfection results in the inhibition of goose embryonic dermal fibroblast cells proliferation and TCF4 acts to inhibit the mRNA and protein expression levels of the Wnt signaling pathway related genes, like Axin2, β-catenin and promotes these of cyclin D3 gene. These results speculate that TCF4 could activate the Wnt/β-catenin signal pathway in The GEDF cells and promotes their proliferation. Furthermore, the co-transfection of miR-140-y inhibitor and siRNA-TCF4 in GEDF cells results in the rescue of TCF4 expression and the activation of Wnt signaling pathway leading to the increase of cell proliferation. This suggest that miR-140-y could regulates skin and feather follicle development by target the TCF4 and activating the Wnt/ β-catenin signaling pathway.

In summary, miR-140-y works as a dynamic factor to regulate, control and maintain skin and feather follicles growth by targeting TCF4 gene and interfering with the Wnt signaling pathway. Moreover, our findings speculate that miR-140-y may suppress the transcription of β-catenin/TCF, leading to the inhibition of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway and influencing the growth and proliferation of key cells of feather development, especially, the dermal fibroblast cells (Figure 13).

Figure 13.

miR-140-y control skin and feather follicle development via the Wnt/β‐catenin signaling pathway by targeting TCF4 gene in dermal fibroblast cells.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to express our acknowledgment to Jilin Agricultural University for their important role in the daily management and operation of the incubation system of the goose seed source base. This work was supported by the Key Research and Development Project of Jilin Provincial Department of Science and Technology (20230202064NC), Innovation and Entrepreneurship Talent Funding Project of the Human Resources and Social Security Department of Jilin Province (2022ZY16) and the Livestock and Poultry Genetic Resources Development and Utilization Project of the Animal Husbandry Administration of Jilin Province (2023).

Data Availability: The raw data of the miRNA-seq used in this research is available on the CNGB database (available online: https://db.cngb.org) under accession number CNP0004239.

DISCLOSURES

The authors state that they have no known competing financial interests or personal ties that could have influenced the work reported in this study.

REFERENCES

- Andl T., Murchison E.P., Liu F. The miRNA-processing enzyme dicer is essential for the morphogenesis and maintenance of hair follicles. Curr. Biol. 2006;16:1041–1049. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Ge K., Wang M. Integrative analysis of the Pekin duck (Anas anas) MicroRNAome during feather follicle development. BMC Dev. Biol. 2017;17:12. doi: 10.1186/s12861-017-0153-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Haichen B., Li L. Follicle characteristics and follicle developmental related Wnt6 polymorphism in Chinese indigenous Wanxi-white goose. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2012;39:9843–9848. doi: 10.1007/s11033-012-1850-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y., Huang J., Liu Z. miR-140-5p in small extracellular vesicles from human papilla cells stimulates hair growth by promoting proliferation of outer root sheath and hair matrix cells. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020;8 doi: 10.3389/fcell.2020.593638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi B.Y. Targeting Wnt/β-catenin pathway for developing therapies for hair loss. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020;21:4915. doi: 10.3390/ijms21144915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clevers H., Nusse R. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling and disease. Cell. 2012;149:1192–1205. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding Y., Xue X., Liu Z. Expression profiling and functional characterization of miR-26a and miR-130a in regulating Zhongwei goat hair development via the TGF-β/SMAD pathway. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020;21:5076. doi: 10.3390/ijms21145076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Y., Wang J., Ma J. miR-31-5p promotes proliferation and inhibits apoptosis of goat hair follicle stem cells by targeting RASA1/MAP3K1 pathway. Exp Cell Res. 2021;398 doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2020.112441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao W., Sun W., Yin J. Screening candidate microRNAs (miRNAs) in different lambskin hair follicles in Hu sheep. PLoS ONE. 2017;12 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0176532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu X., Zhang X., Liu Z. Exploration of key regulators driving primary feather follicle induction in goose skin. 2020;731 doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2020.144338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y.J., Swencki B. A possible role for the high mobility group box transcription factor Tcf-4 in vertebrate gut epithelial cell differentiation. J. Biol. Chem. 2020;274:1566–1572. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.3.1566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li A., Chen M., Jiang T.X. Shaping organs by a wingless-int/notch/nonmuscle myosin module which orients feather bud elongation. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2013;110:E1452–E1461. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1219813110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y., You Y., Shen H. Effect of Noggin silencing on the BMP and Wnt signaling pathways. Acta Lab. Anim. Sci. Sin. 2016;24:475–480. [Google Scholar]

- Mabrouk I., Zhou Y., Wang S. Transcriptional characteristics showed that miR-144-y/FOXO3 participates in embryonic skin and feather follicle development in Zhedong white goose. Animals (Basel) 2022;12:2099. doi: 10.3390/ani12162099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mi B., Qiushi L., Tong L. High miR-31-5p expression promotes colon adenocarcinoma progression by targeting TNS1. Aging. 2020;12:7480–7490. doi: 10.18632/aging.103096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagosa S., Leesch F., Putin D. microRNA-184 induces a commitment switch to epidermal differentiation. Stem Cell Rep. 2017;12:1991–2004. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2017.10.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng H., Longfei W., Qiang Su. MiR-31-5p promotes the cell growth, migration and invasion of colorectal cancer cells by targeting NUMB. Biomed Pharmacotherap. 2019;109:208–216. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.10.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quan Z., Shanshan L., Bingwang D. High-throughput sequencing reveals miRNAs affecting follicle development in chicken. Int. J. Genet. Genom. 2017;5(6):76–84. [Google Scholar]

- Rajendran R.L., Prakash G., Chang H.S. Macrophage-derived extracellular vesicle promotes hair growth. Cells. 2020;9:856. doi: 10.3390/cells9040856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rim E.Y., Hans C.N. The Wnt pathway: from signaling mechanisms to synthetic modulators. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2022;91:571–598. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-040320-103615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salinas P.C., Yimin Z. Wnt signaling in neural circuit assembly. Annu. Rev. Neuro. 2008;31:339–358. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.31.060407.125649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiina H., Mikio I., Julia B. The human T-cell factor-4 gene splicing isoforms, Wnt signal pathway, and apoptosis in renal cell carcinoma. Clin. Canc. Res. 2003;9:2121–2132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song Y., Liu C., Zhou Y. Regulation of feather follicle development and Msx2 gene SNP degradation in Hungarian white goose. BMC Genom. 2022;23:821. doi: 10.1186/s12864-022-09060-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun D.G., Xin B.C., Wu D. miR-140-5p-mediated regulation of the proliferation and differentiation of human dental pulp stem cells occurs through the lipopolysaccharide/toll-like receptor 4 signaling pathway. Eur. J. Oral Sci. 2017;125:419–425. doi: 10.1111/eos.12384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao S.C., Yuan T., Zhang Y.L. Exosomes derived from miR-140-5p-overexpressing human synovial mesenchymal stem cells enhance cartilage tissue regeneration and prevent osteoarthritis of the knee in a rat model. Theranostics. 2017;7:180–195. doi: 10.7150/thno.17133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tseng A.M., Chung D.D., Pinson M.R. thanol exposure increases miR-140 in extracellular vesicles: implications for fetal neural stem cell proliferation and maturation. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2019;43:1414–1426. doi: 10.1111/acer.14066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z., Hu J., Pan Y. miR-140-5p/miR-149 affects chondrocyte proliferation, apoptosis, and autophagy by targeting FUT1 in osteoarthritis. Inflammation. 2018;41:959–971. doi: 10.1007/s10753-018-0750-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong Y., Liu Y., Song Z. Identification of Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway in dermal papilla cells of human scalp hair follicles: TCF4 regulates the proliferation and secretory activity of dermal papilla cell. J Dermatol. 2014;41:84–91. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.12313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan X., Yaguang X., Zongyuan Z. Slaughter performance of the main goose breeds raised commercially in China and nutritional value of the meats of the goose breeds: a systematic review. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2023;103:3748–3760. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.12244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi R., Dónal O'Carroll H.A., Pasolli Z.Z. Morphogenesis in skin is governed by discrete sets of differentially expressed microRNAs. Nat. Genet. 2006;38:356–362. doi: 10.1038/ng1744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi R., Matthew N.P., Markus S.F. A skin microRNA promotes differentiation by repressing ‘stemness’. Nature. 2008;452:225–229. doi: 10.1038/nature06642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu M., Yue Z., Wu P. The biology of feather follicles. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 2004;48:181–191. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.031776my. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu N., Song Z., Zhang K. MAD2B acts as a negative regulatory partner of TCF4 on proliferation in human dermal papilla cells. Sci. Rep. 2017;7(1):11687. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-10350-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L., Nie Q., Su Y. MicroRNA profile analysis on duck feather follicle and skin with high-throughput sequencing technology. Gene. 2013;519:77–81. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2013.01.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W., Wu J., Li J. A subset of skin-expressed microRNAs with possible roles in goat and sheep hair growth based on expression profiling of mammalian microRNAs. Omics. 2007;11:385–396. doi: 10.1089/omi.2006.0031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]