Abstract

Introduction:

Alcohol (ethanol) and cannabis are among the most widely used recreational drugs in the world. With increased efforts toward legalization of cannabis, there is an alarming trend toward the concomitant (including simultaneous) use of cannabis products with alcohol for recreational purpose. While each drug possesses a distinct effect on cerebral circulation, the consequences of their simultaneous use on cerebral artery diameter have never been studied. Thus, we set to address the effect of simultaneous application of alcohol and (-)-trans-Δ-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) on cerebral artery diameter.

Materials and Methods:

We used Sprague-Dawley rats because rat cerebral circulation closely mimics morphology, ultrastructure, and function of cerebral circulation of humans. We focused on the middle cerebral artery (MCA) because it supplies blood to the largest brain territory when compared to any other cerebral artery stemming from the circle of Willis. Experiments were performed on pressurized MCA ex vivo, and in cranial windows in vivo. Ethanol and THC were probed at physiologically relevant concentrations. Researchers were “blind” to experimental group identity during data analysis to avoid bias.

Results:

In males, ethanol mixed with THC resulted in greater constriction of ex vivo pressurized MCA when compared to the effects exerted by separate application of each drug. In females, THC, ethanol, or their mixture failed to elicit measurable effect. Vasoconstriction by ethanol/THC mixture was ablated by either endothelium removal or pharmacological block of calcium- and voltage-gated potassium channels of large conductance (BK type) and cannabinoid receptors. Block of prostaglandin production and of endothelin receptors also blunted constriction by ethanol/THC. In males, the in vivo constriction of MCA by ethanol/THC did not differ from ethanol alone. In females, the in vivo constriction of this artery by ethanol was significantly smaller than in males. However, artery constriction by ethanol/THC did not differ from the constriction in males.

Conclusions:

Our data point at the complex nature of the cerebrovascular effects elicited by simultaneous use of ethanol and THC. These effects include both local and systemic components.

Keywords: cerebral vasculature, substance co-abuse, myogenic tone, artery diameter trace, cranial window

Introduction

Ethanol and cannabis (either natural cannabis flower or synthetic cannabinoids) are among the most widely used recreational, psychoactive drugs in the world. An annual global drug survey that contains data from 18 countries worldwide reports a 98.3% prevalence of ethanol use and a 77.4% prevalence of cannabis (all forms) use within the past 12 months.1

Numerous epidemiological studies have described the deleterious effect of excessive episodic consumption of ethanol on cerebrovascular health.2–5 Episodic drinking with blood ethanol levels reaching 35–80 mM is associated with an increased risk for cerebrovascular ischemia,3 stroke, and death from ischemic stroke.4 Cerebrovascular ischemia may result from impaired vasodilation and/or enhanced constriction of cerebral arteries. Despite brain region variability, a decrease in cerebral perfusion following excessive ethanol consumption has been consistently reported in humans.6,7 Such decrease is consistent with cerebral artery constriction. In a rat model widely used to mimic the human cerebral artery,8 in vivo imaging and in vitro studies detected ethanol-induced cerebrovascular constriction that was caused by ethanol inhibition of calcium- and voltage-gated potassium channels of large conductance (BK) in the vascular smooth muscle.9,10

With regard to cannabis, studies in humans unveil various neurovascular deficits that are associated with the use of this substance.11 Epidemiological reports repeatedly documented that cannabinoids substantially increased risk for ischemic stroke.12,13 Onsets of acute ischemic stroke have been reported within hours of exposure to natural14 and synthetic cannabinoids.12 Remarkably, cannabinoid use is recognized as a trigger for cerebrovascular malfunction in the absence of other risk factors.12,13 Data obtained from human subjects in vivo documented increase in blood velocity15,16 and cerebrovascular resistance17 following cannabis use. Thus, similar to ethanol, cannabis itself has vasoactive properties in the cerebrovascular tree.

The concomitant (including simultaneous) use of cannabis with ethanol is widespread. In the United States, 23% of high school seniors report simultaneous use of ethanol and cannabis.18 This high prevalence tends to not wane, but continues during college freshmen year.19 Despite the epidemic proportion of the concomitant use of ethanol with cannabis, the consequences of such consumption on cerebrovascular function remain scarcely studied. In this work, we addressed the effects of the combined use of ethanol and the main psychoactive compound of cannabis, (-)-trans-Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), on cerebral artery function using a rat model that matches human cerebral arteries.8,9

Materials and Methods

Ethical aspects of research

The care of animals and experimental protocols were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Tennessee Health Science Center, which is an institution accredited by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care international (AAALACi).

Cranial window in vivo was obtained on adult Sprague-Dawley rats (10–12 weeks of age) as described in Supplementary Material and Methods. During surgery, animals did not experience substantial bleeding, cerebrospinal fluid leaks, eye bulging, or seizures, and we did not observe any swelling or shrinkage of the brain. Throughout surgery, rectal temperature averaged 96.6°F±0.8°F (ranging between 93.3°F and 99.6°F) as determined by readings every 15 min.

Artery pressurization ex vivo was performed as described in Supplementary Material and Methods. When required by experimental design, the lack of endothelium was verified by comparing the efficacy of endothelium-dependent versus endothelium-independent vasodilators.9,20 Arteries were pressurized at 60 mmHg.21 To avoid any possible receptor desensitization related to repeated/protracted exposure to the ligand,22,23 every artery segment was probed once with one drug/concentration.

Chemicals

Stock of THC at 1 mg/mL of methanol was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Before the experiment, methanol was evaporated under the stream of N2 gas in the hood, and THC was re-dissolved in either dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) or ethanol (ethyl alcohol) to render 30.18 mM THC stock. Ethanol (190 proof) and all other chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. THC stock solution and ethanol were diluted into saline (0.9% sodium chloride) to reach final concentrations immediately before experimental use.

Data analysis and statistics

Analysis was performed by investigators who were “blind” to experimental group identity. Artery diameter measurements from in vivo studies were obtained from cranial window images using ImageJ software.

Ex vivo diameter traces were analyzed using IonWizard 4.4 software (IonOptix). The value for basal artery diameter (i.e., diameter before drug application) was obtained by averaging diameter values from the same arterial segment during 3 min of recording immediately before drug application. Drug-induced effects in arterial diameter were determined at the maximal, steady drug concentration reached in the chamber before the perfusion was switched to a washout of drugs with drug-free physiological saline. The concentration–response curve data obtained from ex vivo experiments were fitted to a Boltzmann function and with a Levenberg-Marquardt iteration algorithm using built-in fitting routine in Origin 2020 software.

Statistical analysis was performed using InStat3.05 software (GraphPad). Distribution of data was checked using Kolmogorov-Smirnov approach. For non-normal distribution of data, and when mode of distribution could not be established with certainty (number of observations <10), statistical methods included Mann-Whitney test for two experimental groups and Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn's post-test for comparison of three and more experimental groups. For detection of possible interaction between THC and ethanol, two-way analysis of variance was performed using built-in function in Origin 2020. Significance was set at p<0.05, >80% power. Data are expressed as mean±standard deviation. In each experimental group, individual diameter recordings in vivo or artery segments ex vivo (sample size, n) were obtained from different animals. Final plotting and fitting of data were conducted using the Origin 2020.

Results

Ethanol/THC mixture ex vivo exacerbates cerebral artery constriction when compared to THC or ethanol alone

Marijuana (cannabis) smoking results in blood THC levels ranging between 1 and 143 nM.24,25 In our study, THC at 4.2, 21, 42, and 100 nM, that is, within the physiologically relevant range of THC concentrations, failed to change middle cerebral artery (MCA) diameter compared to concentration-matched DMSO vehicle (n=4–6 for each THC concentration and control groups) (Fig. 1A, B). Yet, simultaneous application of THC concentrations with 50 mM ethanol demonstrated that the constriction of the MCA is statistically larger at concentrations of 4, 20, and 42 nM THC (n=4–6 for each concentration) (Fig. 1A, B). Notably, simultaneous application of 100 nM THC with 50 mM ethanol (n=4) failed to change artery diameter, presumably, due to de-sensitization.

FIG. 1.

Simultaneous application of THC and alcohol (EtOH) ex vivo exacerbates constriction of rat MCA when compared to THC or alcohol alone. (A) Original traces of MCA diameter change in response to 42 nM THC in DMSO vehicle (top left), 42 nM THC in DMSO vehicle supplemented with 50 mM EtOH (bottom left), 50 mM EtOH (top right), and 42 nM THC with 50 mM EtOH (DMSO free, bottom right). Shaded areas highlight reduction in artery diameter upon drug application. (B) Concentration–response curve to a range of THC concentrations, their matching DMSO (vehicle), and simultaneous use of various THC concentrations with 50 mM EtOH. Each data point reflects an average of no less than four data points from different rats. Data were fitted with Boltzmann equation followed by Levenberg-Marquardt iteration algorithm in Origin 2021 software (OriginLab). For 4.1 nM THC with 50 mM EtOH, p=0.0079; 21 nM THC with 50 mM EtOH, p=0.0238; and 42 nM THC with 50 mM EtOH, p=0.0426, all analysis performed using two-tail Mann-Whitney test. Here, and in all other figures, data are expressed as mean±SD. (C) Concentration–response curve to a range of EtOH concentrations and simultaneous use of various EtOH concentrations with 42 nM THC. *p=0.04 by two-tail Mann-Whitney test. (D) Scattered data showing differences in rat MCA constriction ex vivo between 42 nM THC (in DMSO vehicle) when compared to 42 nM THC (in DMSO vehicle) supplemented with 50 mM EtOH (left set of bars). Similar difference exists between 50 mM EtOH and simultaneous application of 42 nM THC with 50 mM EtOH (DMSO-free, right set of bars). **p=0.02, *p=0.0364 by one-tail Mann-Whitney test. DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide; MCA, middle cerebral artery; SD, standard deviation.

For ethanol, physiologically relevant concentrations are in the mM range. For instance, 5 mM (25 mg/dL) blood ethanol is achieved in 18+ year-old humans after just one standard drink.26,27 Around 17 mM (80 mg/dL) in blood constitutes legal limit of intoxication for driving a motor vehicle in most of the United States,28 and is achievable after 3–4 standard drinks consumed within 2 h.27 Thirty-five to fifty millimolar ethanol (161–230 mg/dL) is achieved in the blood following moderate-to-heavy alcohol intake, usually in the form of 4 drinks for women and 5 drinks for men, depending on consumer's physical characteristics.27

Ethanol at 75–100 mM (345–461 mg/dL) results in severe intoxication and, possibly, death.29 Without DMSO, and consistent with previous reports,9,30 ethanol within the range of physiologically relevant concentrations rendered a concentration-dependent constriction (EC50 ≈ 24 mM; Fig. 1A, C). THC (42 nM) with 50 mM ethanol (n=4) constricted more than ethanol (n=4) (Fig. 1A, C). The potency of the ethanol/THC mixture EC50 reached 36 mM.

For further detailed studies, THC was probed at 42 nM because that level falls within the range of concentrations found in the blood of cannabis smokers.25 Ethanol was used at a concentration of 50 mM, which is achieved in the blood following moderate-to-heavy drinking.26 Compared to the matching amount of DMSO (n=6), 42 nM THC in DMSO (n=7) did not affect diameter (Fig. 1A, D). Ethanol/THC (50 mM/42 nM; n=3) application in DMSO vehicle constricted MCA up to 14.4%±7.6% (Fig. 1A, D). There was a statistically significant difference between constriction by 42 nM THC (in DMSO) and ethanol/THC mixture in DMSO (Fig. 1D).

Without DMSO, 50 mM ethanol constricted the MCA up to 5.1%±1.9% (n=9) (Fig. 1A, D). However, when 50 mM ethanol was used as a vehicle for 42 nM THC, the MCA constricted up to 18.5%±5.6% (n=5). While the effect of 42 nM THC on its own was not different from DMSO-containing control, the effect of ethanol/THC mixture was statistically larger compared to 50 mM ethanol alone (Fig. 1D).

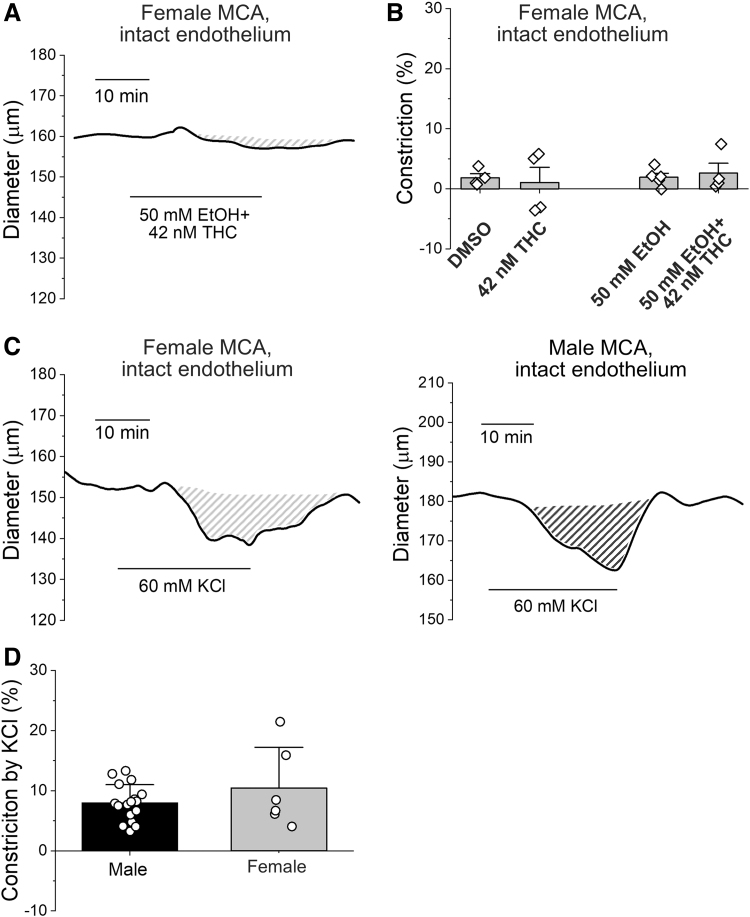

Sexual dimorphism of MCA responses

Ex vivo pressurized MCAs from females failed to constrict by 42 nM THC (n=4) when compared to DMSO vehicle (n=4). They also lacked responses to 50 mM ethanol (n=5) and ethanol/THC mixture (n=4) (Fig. 2A, B). To ensure contractile viability, arteries were probed with the nonselective vasoconstrictor KCl (60 mM). In females, KCl constriction of 10.5%±6.8% (n=6) did not differ from the 9.5%±3.3% in males (n=17) (Fig. 2C, D).

FIG. 2.

Middle cerebral arteries from female rats fail to constrict when probed with THC, EtOH, or their combination. (A) Original record showing lack of changes in MCA diameter from female rat in response to simultaneous application of 42 nM THC with 50 mM EtOH. (B) Scattered data showing lack of artery diameter changes by THC, EtOH, or their combination in ex vivo pressurized arteries from female rates. (C) Original diameter traces showing similar degree of MCA constriction to 60 mM KCl in ex vivo pressurized arteries from female (left) and male (right) rats. Shaded areas highlight the vasoconstrictive effect of nonspecific vasoconstrictor KCl. (D) Scattered data showing lack of difference in MCA constriction to challenge by 60 mM KCl in arteries from male versus female rats.

Mechanism of ethanol/THC constriction

Constriction of male MCA by simultaneous use of 42 nM THC and 50 mM ethanol was fully reversed by 1 μM paxilline (n=4), 1 μM AM251 (n=4), or 1 μM AM630 (n=3) (Fig. 3). Paxilline is a rather selective blocker of BK channels31,32 which mediate ethanol effect on MCA diameter.9,33 AM251 and AM630 are inverse agonists of canonical cannabinoid receptors of type 1 (CB1) and type 2 (CB2), respectively.34,35

FIG. 3.

Vasoconstriction by simultaneous use of THC with EtOH is mediated by relevant targets of THC and EtOH. Scattered data show that MCA constriction by 42 nM THC combined with 50 mM EtOH is reversed by the blocker of BK channels 1 μM paxilline (Pax, *p=0.0159), inverse agonist of CB1 receptor 1 μM AM251 (*p=0.0159), or inverse agonist of CB2 receptor 1 μM AM630 (*p=0.0357). Statistical analysis was performed by two-tail Mann-Whitney test for each blocker compared to the constriction by simultaneous use of THC with EtOH. BK, calcium- and voltage-gated potassium channels of large conductance; CB1, cannabinoid receptor of type 1; CB2, cannabinoid receptor of type 2.

To determine possible involvement of endothelium, MCAs were subjected to passing an air bubble as described.9,36 Absence of endothelium was confirmed by the lack of vasodilatory response to endothelium-dependent vasodilator 10 μM carbachol (n=6) (Fig. 4A).37 In contrast, endothelium-independent vasodilator (nitric oxide donor) 10 μM 1-hydroxy-2-oxo-3-(3-aminopropyl)-3-isopropyl-1triazene (NOC5)38 remained effective in eliciting vasodilation in de-endothelialized MCAs (n=7) when compared to intact endothelium (n=5) (Fig. 4A). There were no differences in the effects of 42 nM THC (n=6 in de-endothelialized vessels), 50 mM ethanol (n=17 in de-endothelialized vessels), or 60 mM KCl (n=6 in de-endothelialized vessels) between arteries with intact and denuded endothelium.

FIG. 4.

Role of endothelium in cerebral artery constriction by simultaneous use of THC and EtOH. (A) Scattered graph showing lack significantly smaller dilation of de-endothelialized MCAs from male rat when pressurized ex vivo and probed with endothelium-dependent vasodilator 10 μM carbachol compared to MCAs with intact endothelium (*p=0.0303 by two-tail Mann-Whitney test). Dilation by endothelium-independent nitric oxide donor 10 μM NOC5 does not differ in arteries with intact or denuded endothelium. (B) Scattered data comparing vasoconstriction by various drugs between male MCAs with intact endothelium versus de-endothelialized counterparts. Arteries were pressurized ex vivo at 60 mmHg. *p=0.0159 by two-tail Mann-Whitney test; &statistically significant differences (p<0.05 by two-tail Mann-Whitney test) between contractile responses to 50 mM EtOH compared to simultaneous use of 42 nM THC with 50 mM EtOH in respective vessel preparation (intact, black bars vs. de-endothelialized, hollow bars). (C) Original trace of male MCA artery diameter obtained when artery was ex vivo de-endothelialized, pressurized at 60 mmHg, perfused with nitric oxide donor 10 μM NOC5, and probed by 42 nM THC mixed with 50 mM EtOH in the presence of 10 μM NOC5. (D) Scattered data of male MCA constriction show inability of NOC5 to rescue loss of constriction by THC mixed with EtOH in the presence of nitric oxide donor 10 μM NOC5. NOC5, 1-hydroxy-2-oxo-3-(3-aminopropyl)-3-isopropyl-1triazene.

However, de-endothelialized MCAs only constricted 3.3%±2.3% to ethanol/THC mixture (n=4), which was significantly less than MCA with intact endothelium (Fig. 4B). Moreover, while simultaneous use of THC with ethanol in MCAs with intact endothelium elicited larger constriction compared to ethanol alone, de-endothelialized MCA constriction by ethanol/THC was significantly less compared to ethanol alone (Fig. 4B).

Considering that endothelium releases vasodilatory nitric oxide,39 we probed whether NOC5 would rescue vasoconstriction by ethanol/THC. NOC5 dilated de-endothelialized MCAs by 20.9%±5.7% (n=4; Fig. 4C). However, NOC5 did not rescue the ethanol/THC effect (n=4; Fig. 4C, D).

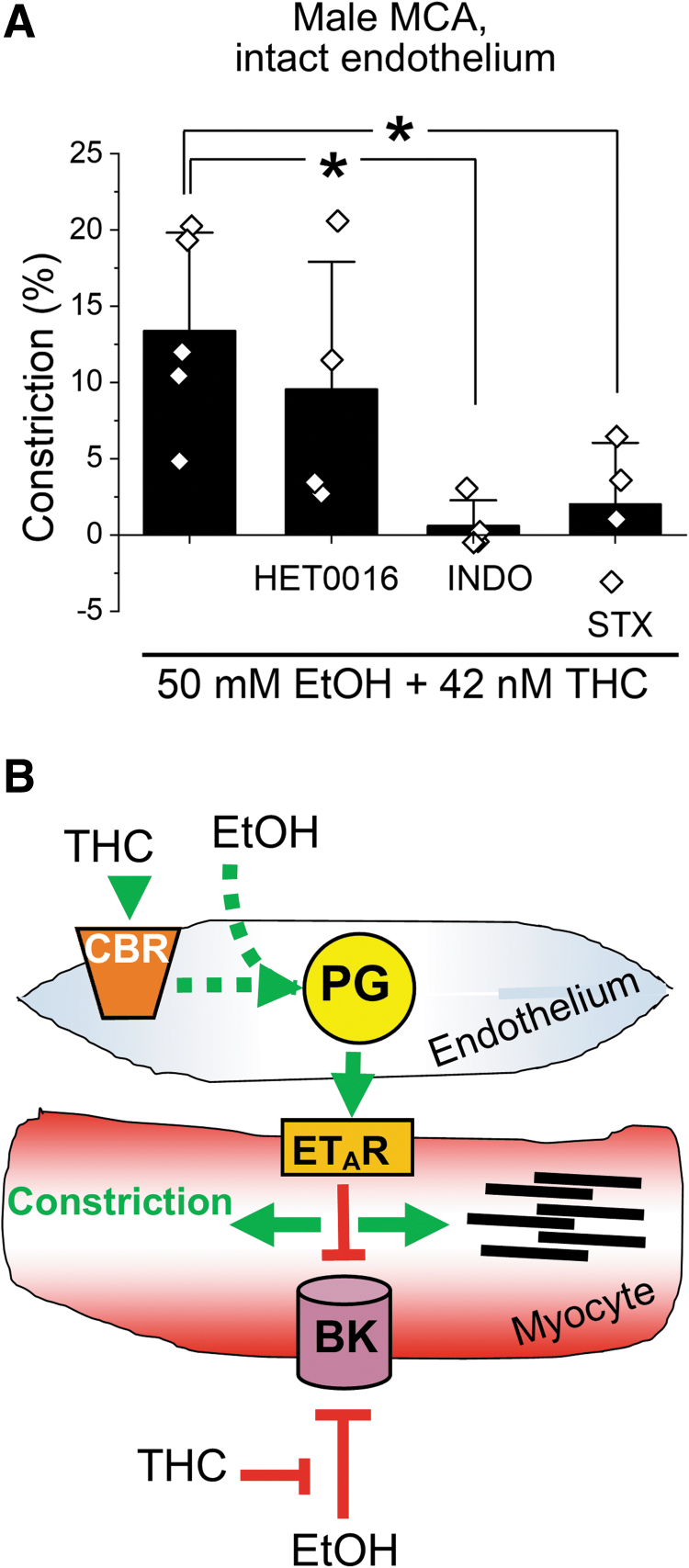

Vasoconstriction by ethanol/THC was blunted by blockers of prostaglandin production, 10 μM indomethacin (INDO;40 n=4) and endothelin receptor type A 10 nM sitaxentan (STX;41 n=4) (Fig. 5A). However, inhibition of arachidonic acid metabolic cascade by 100 nM N-hydroxy-N′-(4-butyl-2-methylphenyl)-formamidine (HET0016)42 did not alter the constrictive effect of THC mixed with ethanol (n=4).

FIG. 5.

Cerebral artery constriction by simultaneous use of THC and EtOH involves molecular targets likely located within as well as outside endothelium. (A) Scattered data showing ablation of vasoconstriction by simultaneous use of 42 nM THC and 50 mM EtOH in the presence of 10 μM INDO and 10 nM STX, but not 100 nM HET0016. *p=0.0159 for difference between the constriction by simultaneous use of 42 nM THC and 50 mM EtOH compared to the effect of this mixed in the presence of INDO; *p=0.0317 for difference between the constriction by simultaneous use of 42 nM THC and 50 mM EtOH compared to the effect of this mixed in the presence of STX. (B) Schematic representation of proposed mechanism and molecular players involved into cerebral artery constriction evoked by simultaneous use of THC and EtOH. CBR, cannabinoid receptors; ETAR, endothelin receptor type A; HET0016, N-hydroxy-N′-(4-butyl-2-methylphenyl)-formamidine; INDO, indomethacin; PG, prostaglandins; STX, sitaxentan.

In synthesis, the proposed mechanism of action for cerebral artery constriction by the ethanol/THC mixture involves multiple players. Considering that the majority of cellular content within cerebral artery wall comprised vascular smooth muscle,8 vasoconstriction by THC mixed with ethanol likely involves a cross talk between endothelium and vascular myocytes (Fig. 5B).

Ethanol/THC mixture constricts cerebral arterioles in vivo in males, but not females

THC did not have a statistically significant effect on cerebral arteriole diameter in males when compared to isovolumic infusion of matching DMSO vehicle in vivo under ketamine anesthesia (Fig. 6A). Ten minutes post-infusion, constrictions averaged 5.27±2.21 and 1.92%±26.9% of pre-perfusion values for DMSO and THC, respectively (p>0.05).

FIG. 6.

Effect of THC or EtOH on cerebral arteriole diameter in male and female rats in vivo. (A) Arteriole constriction as a function of time following infusion of 42 nM THC in DMSO vehicle into cerebral circulation through carotid artery catheter in male rats under ketamine anesthesia. Here and in similar plots of Figure 7, horizontal dashed line represents arteriole diameter at time point zero at the very beginning of observation. (B) Representative cranial window images and averaged constriction of cerebral arterioles as a function of time following infusion of 0.9% NaCl (saline) or 50 mM EtOH into cerebral circulation through carotid artery catheter in male rats under ketamine anesthesia. Asterisks (*) define statistically significant difference, 0.0119 ≤ p≤0.0333, two-tail Mann-Whitney test. (C) Arteriole constriction as a function of time following infusion of 42 nM THC in DMSO vehicle into cerebral circulation through carotid artery catheter in female rats under ketamine anesthesia. (D) Representative cranial window images and averaged constriction of cerebral arteriole as a function of time following infusion of 0.9% NaCl (saline) or 50 mM EtOH into cerebral circulation through carotid artery catheter in female rats under ketamine anesthesia.

Consistent with our earlier observations,10 ethanol constricted cerebral arterioles in males (Fig. 6B). Ten minutes post-infusion, 0.9% NaCl infusion caused mild dilation, which averaged 6.13%±13.89%, while ethanol caused constriction, which averaged 23.16%±12.06% (p=0.0008, one-tail Mann-Whitney test).

In females, THC did not exert significant effects apart from 13 min post-infusion (Fig. 6C). Here, constriction by DMSO averaged 12.05±8.48 compared to 0.43%±15.92% by THC (p=0.0159, two-tail Mann-Whitney test). Ethanol failed to constrict (Fig. 6D). Ten minutes post-infusion, constriction averaged 6.64±10.33 and 6.20%±12.03% for NaCl and ethanol, respectively (p>0.05).

Ethanol/THC mixture (50 mM/42 nM) in males and females resulted in constriction with percent values 10 min post-infusion averaging 15.09±16.52 and 14.06%±11.11%, respectively (Fig. 7A). Contrary to our findings ex vivo, the constriction by ethanol/THC did not differ from ethanol or THC alone in either sex (Fig. 7B).

FIG. 7.

Cerebral arteriole constriction by simultaneous use of THC and EtOH in vivo. (A) Representative cranial window images and averaged constriction of cerebral arteriole as a function of time following infusion of 0.9% NaCl (saline) or simultaneous infusion of 42 nM THC and 50 mM EtOH into cerebral circulation through carotid artery catheter in male rats under ketamine anesthesia. *0.0103 ≤ p≤0.0296, one-tail Mann-Whitney test. (B) Scattered data summarizing the effect of THC, EtOH, or their simultaneous use on cerebral arteriole diameter in vivo in male and female rats under ketamine anesthesia. **0.0008 ≤ p≤0.0076, one-tail Mann-Whitney test. #Different from constriction by 50 mM EtOH in males, p=0.0159 by two-tail Mann-Whitney test. (C) Representative cranial window images and averaged constriction of cerebral arterioles as a function of time following infusion of 0.9% NaCl (saline) or simultaneous infusion of 42 nM THC and 50 mM EtOH into cerebral circulation through carotid artery catheter in female rats under ketamine anesthesia. *0.0286 ≤ p≤0.0317, one-tail Mann-Whitney test. (D) Scattered data summarizing the effect of THC, EtOH, or their simultaneous use on cerebral arteriole diameter in vivo in male and female rats under isoflurane anesthesia. *p=0.0278, **p=0.0087, one-tail Mann-Whitney test.

To account for a possible interaction between EtOH, THC, and the particular anesthetic used (ketamine), the entire experimental series in vivo was repeated on rats subjected to isoflurane anesthesia throughout cranial window experiment. Although absolute values of cerebral arteriole constriction appeared smaller when compared to data obtained under ketamine (Fig. 7D vs. C), the qualitative outcomes remained. Specifically, THC did not have a statistically significant effect on cerebral arteriole diameter in males when compared to isovolumic infusion of matching DMSO vehicle in vivo under isoflurane anesthesia (Fig. 7D). Ten minutes post-infusion, small dilation from the pre-infusion value averaged 4.69±2.81 and 3.43%±1.46% for DMSO and THC, respectively (p>0.05).

Consistent with our earlier observations,10 ethanol constricted cerebral arterioles in males (Fig. 7D). Ten minutes post-infusion, 0.9% NaCl infusion caused robust dilation that averaged 19.02%±6.10%, while ethanol caused constriction averaging 1.48%±5.02% (p=0.0278, one-tail Mann-Whitney test).

In females, DMSO dilated on average 7.03±10.63 compared to mild constriction of 8.39%±7.12% by THC (Fig. 7D). Ethanol failed to constrict (Fig. 7D). Ten minutes post-infusion, mild dilation averaged 9.65±4.75 and 6.01%±7.11% for NaCl and ethanol, respectively (p>0.05).

Ethanol/THC mixture (50 mM/42 nM) infusion evoked constriction in males, but not females, with percent values 10 min post-infusion averaging 4.24±5.18 and 0.56%±3.28%, respectively (Fig. 7D). Like our in vivo findings under ketamine anesthesia, the constriction by ethanol/THC did not differ from ethanol or THC alone in either sex (Fig. 7B vs. D).

Discussion

The driving force for our work stems from the increasing use of cannabis and synthetic cannabinoids for recreational purposes, this use often coinciding with ethanol consumption.43,44 Moreover, cannabis and related products have been increasingly used or been considered for use as therapeutic substances for numerous medical conditions, including treatment of pain,45 as an anticancer therapy,46,47 and as means to alleviate side effects of chemotherapy.48–50 In general, simultaneous use of THC and ethanol has effects that are distinct from separate use of these drugs. In humans, driving the motor vehicle under the influence of both drugs leads to a greater performance impairment than driving under the influence of either one of the illicit substances.51 In male laboratory rats, simultaneous use of ethanol and THC triggered distinct pattern of alterations in glucose handling and insulin homeostasis.52

With regard to cerebral perfusion, moderate-to excessive ethanol consumption has been consistently recognized as a risk factor for cerebrovascular dysfunction.2–4 The reports on cannabis's effect on cerebrovascular health are somewhat contradictory to each other. On one hand, in several experimental animal models, cannabinoid-like compounds improved outcomes of cerebral infarction.53–56 On the other hand, however, epidemiological studies point to cannabis use as a risk factor for cerebrovascular disease and stroke.12,13,57

Several mechanisms have been proposed to contribute into cannabis-related strokes, including conditions associated with cerebral artery constriction (such as vasospasm and reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome).57–60 Moreover, alcohol consumption concomitant with cannabis use has been reported as a trigger of cannabis-related strokes.57 Our present findings ex vivo are in line with these observations and show that physiologically attainable levels of THC significantly exacerbate MCA constriction by ethanol (Fig. 1).

In vivo data (Fig. 7), however, failed to detect exacerbation of MCA constriction by simultaneous use of ethanol with THC. Some possible explanations could be that there were compensatory mechanisms preventing THC mixture with ethanol from affecting MCA diameter, these compensatory mechanisms being related to hemodynamics outside cerebral circulation. For instance, alcohol has been consistently shown to provide mild systemic hypertension,61 while THC either led to decreased mean arterial pressure62 or did not have measurable effect.63 We could not find reports of changes in systemic blood pressure by concomitant use of ethanol with THC.

However, considering that these drugs individually have opposite effects on blood pressure, it is likely that their combination fails to evoke measurable changes. Even if there is an effect on systemic blood pressure, cerebral vessels are able to maintain constant blood flow to the brain. This autoregulation of cerebral circulation allows for constant perfusion within a wide range of systemic blood pressures (between 50 and 150 mmHg) through constant adaptation of diameter.64,65 Regarding vessels (namely, brain capillaries) that are downstream of cerebral arteries, we cannot rule out that alcohol and THC trigger retrograde signaling that negates the effect on cerebral artery diameter in our in vivo studies.

Another possible explanation for the discrepancy between ex vivo and in vivo observations could be that the difference in the route of administration results in differential ability of THC to reach its molecular targets within cerebral arteries. Indeed, differential pharmacokinetics of THC based on route of administration is widely described in humans and laboratory animals.66 However, due to ability to cross cellular membranes, THC reaches the brain, disregarding the route of administration.67 Therefore, differential outcomes of ex vivo and in vivo experiments are likely to have additional explanation(s).

One of these additional explanations is the possible contribution of systemic metabolism into the differential effect of ethanol/THC mixture on cerebral artery diameter ex vivo versus in vivo. Indeed, simultaneous use of alcohol drink with THC vapor resulted in significantly higher blood concentration of THC in human volunteers.51 While blood ethanol levels were not reported to be affected by THC vaping, likely elevated THC concentrations in our animal model might have contributed to the lack of exacerbated MCA constriction in vivo when compared to ethanol co-application with THC in the study of cerebral artery diameter ex vivo.

Another variable under consideration is the importance of central nervous system integrity in response of cerebral artery to ethanol mixed with THC. Importance of central nervous system is not that surprising, as cannabinoid receptors for THC has been mapped in multiple neuronal and glial populations, including brain territories that are irrigated by MCA under study.68 We cannot rule out that the use of ketamine anesthesia during our experiments interfered with the effect of THC and ethanol.69,70 Indeed, while ethanol-induced constriction of female arterioles was significantly smaller compared to males under ketamine anesthesia (Fig. 7B), experiments under isoflurane anesthesia did not render statistically significant differences in ethanol-induced constriction between sexes (Fig. 7D).

Despite this sexual dimorphism in anesthetic interaction with ethanol, however, our data with isoflurane anesthesia rendered qualitatively similar results for ethanol mixture with THC. This suggests that there may be sexual dimorphism in THC interaction with anesthesia; this dimorphism is compensating for the interaction of ethanol with anesthetics.

Besides interactions with anesthesia, sexual dimorphism exists in ethanol and THC action on cerebral artery itself, in ex vivo setting. Indeed, MCAs from female rats largely failed to constrict in response to ethanol, THC, or their mixture (Fig. 2B). Although we did not find relevant reports on sexual dimorphism of ethanol and THC effects within cerebral arteries, precedents from other organs make this dimorphism somewhat expected. There is vast literature on sexually dimorphic effects of either drug in epidemiological data, various models, and experimental settings.71,72

Our results of sexual dimorphism in MCA response to ethanol and THC suggest that mechanisms governing MCA constriction are sexually distinct. Alternatively, those can be the same mechanisms, yet having differential sensitivity to illicit drugs in males versus females. This lack of sensitivity may arise from a differential expression/function of relevant molecular targets in male versus female MCA. Our quick screen of CB1 receptor and BK channel beta1 subunit, which are major functional targets for THC and alcohol, respectively, rendered sexually dimorphic Western blot readings (Supplementary Fig. S1). As cerebral arteries are composed of several cell types,8 exact cellular location of dimorphic protein presence and perhaps, function, remains to be established.

Our previous work clearly pointed out at vascular smooth muscle BK channels being major effectors of ethanol-induced constriction in cerebral arteries.9 Conceivably, in this study, ethanol itself retained vasoconstrictive properties when probed on MCA after endothelium removal (Fig. 4B). Although de-endothelialization did not modify the lack of THC effect on cerebral artery diameter, and did not reduce constriction by ethanol alone, endothelium removal totally blunted constriction by simultaneous application of ethanol and THC when compared to MCAs with intact endothelium (Fig. 4B).

Thus, in absence of functional endothelium, THC antagonizes BK channel-mediated constriction by ethanol. The fact that endothelial removal is protective against cerebral artery constriction by ethanol mixed with THC is relevant from clinical standpoint. Indeed, deterioration of endothelial function is observed during normal aging73 and several pathological conditions, such as hypertension74 and artery calcification (atherosclerosis).75 Notably, sex differences in human endothelial function have been reported.76 Thus, at least part of sexual dimorphism in vascular responses to ethanol and THC observed in our studies ex vivo may arise from distinct endothelial components between males and females.

Detailed investigation of possible effectors for ethanol and THC in cerebral artery paints a rather complex picture. Concentration-response curves (Fig. 1B, C) reflect a noncompetitive interaction between ethanol and THC. As a result, constriction values obtained for physiologically relevant range of drug concentrations do not reach the same maximal effect in the presence of the other.77 The noncompetitive nature of ethanol/THC mixture targeting CB receptor-BK channel pathway may arise from both these drugs acting at the same pathway in a noncompetitive manner or involving additional contractile mechanisms. Our search for the latter rendered prostaglandin production and endothelin receptor type A (Fig. 5A), both effectors are known for their vasoconstrictive properties in cerebral arteries.78,79 Cellular location of these effectors in our experiments remains under discussion as follows, from reductionist system to a more integrative one.

Considering that (1) THC antagonizes ethanol effect in the absence of functional endothelium and (2) the majority of cellular content in de-endothelialized cerebral arteries is composed of smooth muscle cells,8 and (3) the fact that effectors of ethanol-induced constriction—BK channels—are located within vascular smooth muscle,80 the THC antagonism of ethanol observed in de-endothelialized arteries (Fig. 4B) likely takes place within cerebral artery myocytes (Fig. 5B). In this study, endothelin receptors of A type are also located,81 and therefore may serve as mediators of endothelium-dependent constriction by simultaneous application of ethanol with THC requiring trigger(s) from endothelial cells (Fig. 5B).

Our data from pharmacological blockers (Figs. 3 and 5A) point at involvement of prostaglandin production and CB1 and CB2 receptors (Fig. 5B). While prostaglandin production occurs in multiple cell types, it includes vascular endothelium.82 Endothelial location was also documented for functional CB183 and CB2 receptors.84 Thus, we hypothesize that these molecular effectors of exacerbated vasoconstriction by ethanol mixed with THC are of endothelial location (Fig. 5B). The complexity of mechanisms that govern cerebrovascular responses to THC and ethanol is not surprising, considering that both ligands have multiple molecular targets.

For ethanol, BK channels, transient receptor potential cation channel subfamily V member 1 (TRPV1 channel), and ryanodine receptors of type 2 contribute in a varied degree to ethanol effect on cerebral arteries.85–87 For cannabinoids (THC included), molecular targets include both CB1 and CB2 receptors that are capable of triggering a multitude of intracellular cascades.88 Moreover, THC modulates the activities of TRPV2–4, transient receptor potential ankyrin 1 (TRPA1), transient receptor potential cation channel subfamily M member 8 (TRPM8),89 and G protein-coupled receptor 55 (GPR55).90 Whether these targets or any additional entity are involved, such as messengers from central nervous system (either neurons or glia), remains to be established.

Conclusions

Our data point at the complex nature of cerebrovascular effects elicited by the simultaneous use of ethanol with THC. These effects include both local endothelial and systemic components. Our findings contribute to the further evaluation of advantages versus disadvantages of cannabis use. Possible worsening of adverse consequences on cerebral artery function when cannabinoids are consumed with ethanol should serve as a major warning for cannabis consumers.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

Authors deeply thank Dr. Maria Simakova for performing pilot probing of the effect of ethanol with THC on cerebral artery diameter.

Abbreviations Used

- BK

calcium- and voltage-gated potassium channels of large conductance

- CB1

cannabinoid type 1 (receptor)

- CB2

cannabinoid type 2 (receptor)

- DMSO

dimethyl sulfoxide

- ETAR

endothelin receptor type A

- HET0016

N-hydroxy-N′-(4-butyl-2-methylphenyl)-formamidine

- INDO

indomethacin

- MCA

middle cerebral artery

- NOC5

1-hydroxy-2-oxo-3-(3-aminopropyl)-3-isopropyl-1triazene

- PG

prostaglandins

- SD

standard deviation

- STX

sitaxentan

- THC

(-)-trans-Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol

Authors' Contributions

Conceived research: A.B. Designed the experiments: A.S., K.N., and A.B. Performed experiments: A.S., S.M., K.N., and A.B. Analyzed data: A.S., S.M., K.N., and A.B. Participated in data discussion and article writing: A.S., S.M., K.N., A.D., and A.B. Provided key resources: A.D. All authors approved the final version of the article.

Author Disclosure Statement

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests.

Funding Information

This work was supported by the University of Tennessee Health Science Center start-up funds and R01 AA028468 to A.B.

Supplementary Material

Cite this article as: Slayden A, Mysiewicz S, North K, Dopico A, Bukiya A (2024) Cerebrovascular effects of alcohol combined with tetrahydrocannabinol, Cannabis and Cannabinoid Research 9:1, 252–266, DOI: 10.1089/can.2021.0234.

References

- 1. Winstock AR, Barratt MJ, Maier LI, et al. Global drug survey 2019 key findings report. 2019. Retrieved from https://issuu.com/globaldrugsurvey/docs/gds2019_key_findings_report_may_16_

- 2. Altura BM, Altura BT. Alcohol, the cerebral circulation and strokes. Alcohol. 1984;1:325–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Puddey IB, Rakic V, Dimmitt SB, et al. Influence of pattern of drinking on cardiovascular disease and cardiovascular risk factors—a review. Addiction. 1999;94:649–663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Reynolds K, Lewis B, Nolen JD, et al. Alcohol consumption and risk of stroke: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2003;289:579–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Patra J, Taylor B, Irving H, et al. Alcohol consumption and the risk of morbidity and mortality for different stroke types—a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Volkow ND, Mullani N, Gould L, et al. Effects of acute alcohol intoxication on cerebral blood flow measured with PET. Psychiatry Res. 1988;24:201–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ingvar M, Ghatan PH, Wirsén-Meurling A, et al. Alcohol activates the cerebral reward system in man. J Stud Alcohol. 1998;59:258–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lee RM. Morphology of cerebral arteries. Pharmacol Ther. 1995;66:149–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Liu P, Ahmed A, Jaggar J, et al. Essential role for smooth muscle BK channels in alcohol-induced cerebrovascular constriction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:18217–18222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bukiya A, Dopico AM, Leffler CW, et al. Dietary cholesterol protects against alcohol-induced cerebral artery constriction. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2014;38:1216–1226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cadet JL, Bolla K, Herning RI. Neurological assessments of marijuana users. Methods Mol Med. 2006;123:255–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bernson-Leung ME, Leung LY, Kumar S. Synthetic cannabis and acute ischemic stroke. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2014;23:1239–1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wolff V, Armspach JP, Beaujeux R, et al. High frequency of intracranial arterial stenosis and cannabis use in ischaemic stroke in the young. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2014;37:438–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Oyinloye O, Nzeh D, Yusuf A, et al. Ischemic stroke following abuse of Marijuana in a Nigerian adult male. J Neurosci Rural Pract. 2014;5:417–419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mathew RJ, Wilson WH, Humphreys DF, et al. Changes in middle cerebral artery velocity after marijuana. Biol Psychiatry. 1992;32:164–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Herning RI, Better WE, Tate K, et al. Marijuana abusers are at increased risk for stroke. Preliminary evidence from cerebrovascular perfusion data. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2001;939:413–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Herning RI, Better WE, Tate K, et al. Cerebrovascular perfusion in marijuana users during a month of monitored abstinence. Neurology. 2005;64:488–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Terry-McElrath YM, O'Malley PM, Johnston LD. Simultaneous alcohol and marijuana use among U.S. high school seniors from 1976 to 2011: trends, reasons, and situations. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;133:71–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Haas AL, Wickham R, Macia K, et al. Identifying classes of conjoint alcohol and marijuana use in entering freshmen. Psychol Addict Behav. 2015;29:620–626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bukiya AN, Vaithianathan T, Kuntamallappanavar G, et al. Smooth muscle cholesterol enables BK β1 subunit-mediated channel inhibition and subsequent vasoconstriction evoked by alcohol. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011;31:2410–2423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Adebiyi A, Zhao G, Cheranov SY, et al. Caveolin-1 abolishment attenuates the myogenic response in murine cerebral arteries. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;292:H1584–H1592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Dopico AM, Lovinger DM. Acute alcohol action and desensitization of ligand-gated ion channels. Pharmacol Rev. 2009;61:98–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Dopico AM, Bukiya AN, Jaggar JH. Calcium- and voltage-gated BK channels in vascular smooth muscle. Pflugers Arch. 2018;470:1271–1289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Khiabani HZ, Bramness JG, Bjørneboe A, et al. Relationship between THC concentration in blood and impairment in apprehended drivers. Traffic Inj Prev. 2006;7:111–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Huestis MA, Henningfield JE, Cone EJ. Blood cannabinoids. I. Absorption of THC and formation of 11-OH-THC and THCCOOH during and after smoking marijuana. J Anal Toxicol. 1992;16:276–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Diamond I. Cecil textbook of medicine. W. B. Saunders Co., Philadelphia, USA. 1992;44–47. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Donovan JE. Estimated blood alcohol concentrations for child and adolescent drinking and their implications for screening instruments. Pediatrics. 2009;123:e975–e981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Tung GJ, Vernick JS, Stuart EA, et al. Federal actions to incentivise state adoption of 0.08 g/dL blood alcohol concentration laws. Inj Prev. 2017;23:309–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Heatley MK, Crane J. The blood alcohol concentration at post-mortem in 175 fatal cases of alcohol intoxication. Med Sci Law. 1990;30:101–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Chang J, Fedinec AL, Kuntamallappanavar G, et al. Endothelial nitric oxide mediates caffeine antagonism of alcohol-induced cerebral artery constriction. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2016;356:106–115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sanchez M, McManus OB. Paxilline inhibition of the alpha-subunit of the high-conductance calcium-activated potassium channel. Neuropharmacology. 1996;35:963–968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Niday Z, Bean BP. BK channel regulation of afterpotentials and burst firing in cerebellar purkinje neurons. J Neurosci. 2021;41:2854–2869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bukiya AN, Liu J, Dopico AM. The BK channel accessory beta1 subunit determines alcohol-induced cerebrovascular constriction. FEBS Lett. 2009;583:2779–2784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ross RA, Brockie HC, Stevenson LA, et al. Agonist-inverse agonist characterization at CB1 and CB2 cannabinoid receptors of L759633, L759656 and AM630. Br J Pharmacol. 1999;126:665–672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Shearman LP, Rosko KM, Fleischer R, et al. Antidepressant-like and anorectic effects of the cannabinoid CB1 receptor inverse agonist AM251 in mice. Behav Pharmacol. 2003;14:573–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. North K, Bisen S, Dopico AM, et al. Tyrosine 450 in the voltage- and calcium-gated potassium channel of large conductance channel pore-forming (slo1) subunit mediates cholesterol protection against alcohol-induced constriction of cerebral arteries. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2018;367:234–244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Khurana S, Chacon I, Xie G, et al. Vasodilatory effects of cholinergic agonists are greatly diminished in aorta from M3R-/- mice. Eur J Pharmacol. 2004;493:127–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Taka T, Ohta Y, Seki J, et al. Impaired flow-mediated vasodilation in vivo and reduced shear-induced platelet reactivity in vitro in response to nitric oxide in prothrombotic, stroke-prone spontaneously hypertensive rats. Pathophysiol Haemost Thromb. 2002;32:184–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Cyr AR, Huckaby LV, Shiva SS, et al. Nitric oxide and endothelial dysfunction. Crit Care Clin. 2020;36:307–321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Nalamachu S, Wortmann R. Role of indomethacin in acute pain and inflammation management: a review of the literature. Postgrad Med. 2014;126:92–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Scott LJ. Sitaxentan: in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Drugs. 2007;67:761–770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Miyata N, Taniguchi K, Seki T, et al. HET0016, a potent and selective inhibitor of 20-HETE synthesizing enzyme. Br J Pharmacol. 2001;133:325–329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Crawford KA, Gardner JA, Meyer EA, et al. Current marijuana use and alcohol consumption among adults following the legalization of nonmedical retail marijuana sales—Colorado, 2015–2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:1505–1508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lira MC, Heeren TC, Buczek M, et al. Trends in cannabis involvement and risk of alcohol involvement in motor vehicle crash fatalities in the United States, 2000–2018. Am J Public Health. 2021;111:1976–1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Brunt TM, van Genugten M, Höner-Snoeken K, et al. Therapeutic satisfaction and subjective effects of different strains of pharmaceutical-grade cannabis. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2014;34:344–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Pokrywka M, Góralska J, Solnica B. Cannabinoids—a new weapon against cancer? Postepy Hig Med Dosw (Online). 2016;70:1309–1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Velasco G, Hernández-Tiedra S, Dávila D, et al. The use of cannabinoids as anticancer agents. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2016;4:259–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Voth EA, Schwartz RH. Medicinal applications of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol and marijuana. Ann Intern Med. 1997;126:791–798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Todaro B. Cannabinoids in the treatment of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2012;10:487–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Smith LA, Azariah F, Lavender VT, et al. Cannabinoids for nausea and vomiting in adults with cancer receiving chemotherapy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;12:CD009464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Hartman RL, Huestis MA. Cannabis effects on driving skills. Clin Chem. 2013;59:478–492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Nelson NG, Weingarten MJ, Law WX, et al. Joint and separate exposure to alcohol and (9)-tetrahydrocannabinol produced distinct effects on glucose and insulin homeostasis in male rats. Sci Rep. 2019;9:12025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Nagayama T, Sinor AD, Simon RP, et al. Cannabinoids and neuroprotection in global and focal cerebral ischemia and in neuronal cultures. J Neurosci. 1999;19:2987–2995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Hayakawa K, Mishima K, Abe K, et al. Cannabidiol prevents infarction via the non-CB1 cannabinoid receptor mechanism. Neuroreport. 2004;15:2381–2385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Hayakawa K, Mishima K, Nozako M, et al. Delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol (Delta9-THC) prevents cerebral infarction via hypothalamic-independent hypothermia. Life Sci. 2007;80:1466–1471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Khaksar S, Bigdeli MR. Anti-excitotoxic effects of cannabidiol are partly mediated by enhancement of NCX2 and NCX3 expression in animal model of cerebral ischemia. Eur J Pharmacol. 2017;794:270–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Wolff V, Armspach J-P, Lauer V, et al. Cannabis-related stroke myth or reality? Stroke. 2013;44:558–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Zacchariah SB. Stroke after heavy marijuana smoking. Stroke. 1991;22:406–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Barnes D, Palace J, O'Brien MD. Stroke following marijuana smoking. Stroke. 1992;23:1381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Thanvi BR, Treadwell SD. Cannabis and stroke: is there a link? Postgrad Med J. 2009;85:80–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Keil U, Chambless L, Filipiak B, et al. Alcohol and blood pressure and its interaction with smoking and other behavioural variables: results from the MONICA Augsburg Survey 1984–1985. J Hypertens. 1991;9:491–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Crawford WJ, Merritt JC. Effects of tetrahydrocannabinol on arterial and intraocular hypertension. Int J Clin Pharmacol Biopharm. 1979;17:191–196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Uhegwu N, Bashir A, Hussain M, et al. Marijuana induced reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome. J Vasc Interv Neurol. 2015;8:36–38. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Paulson OB, Strandgaard S, Edvinsson L. Cerebral autoregulation. Cerebrovasc Brain Metab Rev. 1990;2:161–192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Lang EW, Yip K, Griffith J, et al. Hemispheric asymmetry and temporal profiles of cerebral pressure autoregulation in head injury. J Clin Neurosci. 2003;10:670–673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Calapai F, Cardia L, Sorbara EE, et al. Cannabinoids, blood-brain barrier, and brain disposition. Pharmaceutics. 2020;12:265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Hložek T, Uttl L, Kadeřábek L, et al. Pharmacokinetic and behavioural profile of THC, CBD, and THC+CBD combination after pulmonary, oral, and subcutaneous administration in rats and confirmation of conversion in vivo of CBD to THC. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2017;27:1223–1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Mackie K. Cannabinoid receptors: where they are and what they do. J Neuroendocrinol. 2008;20:10–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Kleinloog D, Rombouts S, Zoethout R, et al. Subjective effects of ethanol, morphine, Δ(9)-tetrahydrocannabinol, and ketamine following a pharmacological challenge are related to functional brain connectivity. Brain Connect. 2015;5:641–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Zuo D, Sun F, Cui J, et al. Alcohol amplifies ketamine-induced apoptosis in primary cultured cortical neurons and PC12 cells through down-regulating CREB-related signaling pathways. Sci Rep. 2017;7:10523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Erol A, Karpyak VM. Sex and gender-related differences in alcohol use and its consequences: contemporary knowledge and future research considerations. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;156:1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Ketcherside A, Baine J, Filbey F. Sex effects of marijuana on brain structure and function. Curr Addict Rep. 2016;3:323–331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Ungvari Z, Tarantini S, Kiss T, et al. Endothelial dysfunction and angiogenesis impairment in the ageing vasculature. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2018;15:555–565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Cipolla MJ, Liebeskind DS, Chan SL. The importance of comorbidities in ischemic stroke: impact of hypertension on the cerebral circulation. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2018;38:2129–2149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Tesauro M, Mauriello A, Rovella V, et al. Arterial ageing: from endothelial dysfunction to vascular calcification. J Intern Med. 2017;281:471–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Green DJ, Hopkins ND, Jones H, et al. Sex differences in vascular endothelial function and health in humans: impacts of exercise. Exp Physiol. 2016;101:230–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Litman T, Zeuthen T, Skovsgaard T, et al. Competitive, non-competitive and cooperative interactions between substrates of P-glycoprotein as measured by its ATPase activity. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1997;1361:169–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Wanebo JE, Arthur AS, Louis HG, et al. Systemic administration of the endothelin-A receptor antagonist TBC 11251 attenuates cerebral vasospasm after experimental subarachnoid hemorrhage: dose study and review of endothelin-based therapies in the literature on cerebral vasospasm. Neurosurgery. 1998;43:1409–1417. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Koide M, Bonev AD, Nelson MT, et al. Inversion of neurovascular coupling by subarachnoid blood depends on large-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ (BK) channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:E1387–E1395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Orio P, Rojas P, Ferreira G, et al. New disguises for an old channel: MaxiK channel beta-subunits. News Physiol Sci. 2002;17:156–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Kallakuri S, Kreipke CW, Schafer PC, et al. Brain cellular localization of endothelin receptors A and B in a rodent model of diffuse traumatic brain injury. Neuroscience. 2010;168:820–830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Jaiswal N, Diz DI, Chappell MC, et al. Stimulation of endothelial cell prostaglandin production by angiotensin peptides. Characterization of receptors. Hypertension. 1992;19:II49–II55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Liu J, Gao B, Mirshahi F, et al. Functional CB1 cannabinoid receptors in human vascular endothelial cells. Biochem J. 2000;346:835–840. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Ramirez SH, Haskó J, Skuba A, et al. Activation of cannabinoid receptor 2 attenuates leukocyte-endothelial cell interactions and blood-brain barrier dysfunction under inflammatory conditions. J Neurosci. 2012;32:4004–4016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Liu P, Xi Q, Ahmed A, et al. Essential role for smooth muscle BK channels in alcohol-induced cerebrovascular constriction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:18217–18222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Ye Y, Jian K, Jaggar JH, et al. Type 2 ryanodine receptors are highly sensitive to alcohol. FEBS Lett. 2014;588:1659–1665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. North KC, Chang J, Bukiya AN, et al. Extra-endothelial TRPV1 channels participate in alcohol and caffeine actions on cerebral artery diameter. Alcohol. 2018;73:45–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Haspula D, Clark MA. Cannabinoid receptors: an update on cell signaling, pathophysiological roles and therapeutic opportunities in neurological, cardiovascular, and inflammatory diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:7693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Muller C, Morales P, Reggio PH. Cannabinoid ligands targeting TRP channels. Front Mol Neurosci. 2018;11:487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Lauckner JE, Jensen JB, Chen H-Y, et al. GPR55 is a cannabinoid receptor that increases intracellular calcium and inhibits M current. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:2699–2704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.