Abstract

(2S)-Naringenin, a dihydro-flavonoid, serves as a crucial precursor for flavonoid synthesis due to its extensive medicinal values and physiological functions. A pathway for the synthesis of (2S)-naringenin from glucose has previously been constructed in Saccharomyces cerevisiae through metabolic engineering. However, this synthetic pathway of (2S)-naringenin is lengthy, and the genes involved in the competitive pathway remain unknown, posing challenges in significantly enhancing (2S)-naringenin production through metabolic modification. To address this issue, a novel high-throughput screening (HTS) method based on color reaction combined with a random mutagenesis method called atmospheric room temperature plasma (ARTP), was established in this study. Through this approach, a mutant (B7-D9) with a higher titer of (2S)-naringenin was obtained from 9600 mutants. Notably, the titer was enhanced by 52.3% and 19.8% in shake flask and 5 L bioreactor respectively. This study demonstrates the successful establishment of an efficient HTS method that can be applied to screen for high-titer producers of (2S)-naringenin, thereby greatly improving screening efficiency and providing new insights and solutions for similar product screenings.

Keywords: Saccharomyces cerevisiae, (2S)-Naringenin, Atmospheric room temperature plasma, High-throughput screening, Color reaction

Introduction

(2S)-Naringenin, also known as 5,7,4′-trihydroxy-dihydro-flavone, is a secondary metabolite of plant origin with a wide range of physiological functions. Some studies have shown that (2S)-naringenin has positive effects on certain diseases, including anti-cancer and anti-tumour effects, and can reduce the incidence of atherosclerosis and coronary heart disease (Frydman et al. 2013; Akhter et al. 2022). (2S)-Naringenin serves as a direct synthetic precursor for many valuable flavonoids through modifications such as glycosylation, hydroxylation, methylation, and prenylation (Pandey et al. 2016). For example, under the catalysis of dihydro-flavone-3’-hydroxylase (F3’H), the third carbon atom of (2S)-naringenin undergoes hydroxylation to form eriodictyol, which is then methylated to produce hesperetin. Subsequently, eriodictyol and hesperetin are glucosylated and rhamnosylated respectively to obtain the flavonoids eriocitrin and hesperidinin (Salehi et al. 2019; Juca et al. 2020; Kopustinskiene et al. 2020).

Traditionally, (2S)-naringenin is primarily extracted from plants through acid hydrolysis and enzymatic hydrolysis. Additionally, because (2S)-naringenin is insoluble in water but soluble in organic reagents such as methanol and ethanol, it can also be extracted using these solvents (Lu et al. 2023; Cai et al. 2023). However, due to limited plant availability, site and seasonal limitations, large-scale production of (2S)-naringenin is not feasible. Chemical total synthesis or semi-synthesis methods can be used for the preparation of (2S)-Naringenin. However, this option is also unfavorable due to the use of toxic reagents such as thallium nitrate and the difficulty in controlling reaction conditions. (Lee et al. 2003; Wang et al. 2015). Therefore, synthesis using microorganisms is a promising method with the advantages of safety, low cost, high product purity, and no pollution to the environment (Li et al. 2022a; Park et al. 2018).

The chassis cells typically used for (2S)-naringenin production are Escherichia coli (Zhou et al. 2020), Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Koopman et al. 2012), and Yarrowia lipolytica (Wei et al. 2020). Some researchers have also utilized Streptomyces venezuelensis (Park et al. 2009) as a host for (2S)-naringenin production. However, due to its simple genetic manipulation, mature gene editing technology, the presence of P450 enzymes required for flavonoid synthesis, as well as its robustness and harmlessness to the environment and humans (Siddiqui et al. 2012; Suastegui et al. 2016), S. cerevisiae has become the primary host for (2S)-naringenin synthesis. The main bottleneck in de novo synthesis of (2S)-naringenin in S. cerevisiae lies in the availability of malonyl-CoA and p-coumaric acid precursors. Current studies have focused on deregulating the feedback inhibition of Phenylalanine, Tyrosine, and Tryptophan by expressing Aro3K222L, Aro4K229L (Hartmann et al. 2003; Hassing et al. 2019), and Aro7G141S, respectively (Li et al. 2015). Simultaneously, the knockdown of the branching pathway genes PDC5 and ARO10 reduces carbon flow loss and enhances precursor utilization (Liu et al. 2019). To address malonyl-CoA availability issues, introducing a PDH bypass (including the L641P mutant of SeACS from S. cerevisiae and ALD6 from Salmonella enterica) (Liu et al. 2017), along with overexpression of the pantothenate kinase gene PanK increases acetyl-CoA metabolic flux.

Due to the complex genes required for synthesizing (2S)-naringenin in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, the substantial accumulation of by-products, and the limited metabolic modification methods, enhancing production proves challenging. The aim of this study is to obtain a high-titer (2S)-naringenin-producing strain through random mutagenesis, but random mutagenesis will result in a large number of mutants that need to be screened. However, traditional high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) detection methods are inadequate for efficiently screening numerous mutants in a short period of time. Therefore, it is imperative to develop a high-throughput screening (HTS) method. As a dihydro-flavonoid compound, (2S)-naringenin can react with strong alkali to produce color changes and the reaction solution has a specific absorption wavelength at 410 nm. Different concentrations of (2S)-naringenin react with strong alkali resulting in different shades of color, and the OD410 value will also change accordingly. Based on this principle, an HTS method was developed for screening S. cerevisiae strains that produce high-titer (2S)-naringenin efficiently. By combining this HTS method with multiple rounds of ARTP mutagenesis, excellent-performing strains can be selected from the extensive pool of mutants produced. In this study, mutant B7-D9 exhibited the highest titer increase by 52.3%. Compared with the traditional HPLC screening method, this screening strategy in the present study greatly improves screening efficiency while reducing screening costs and time.

Materials and methods

Strains and plasmids

S. cerevisiae HB52, a (2S)-naringenin-producing strain was obtained in our previous work and served as the starting strain for mutagenesis in this study (Li et al. 2022a, b). B7-D9-01 is a strain that integrates the Ura tag on the multicopy site (Ty2) of the B7-D9 strain. The strains, plasmids, and primers used in the study are shown in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strains | Genotype | Source |

|---|---|---|

| JM109 | E. coli used for gene cloning | This lab |

| HB52 | CENPK2-1D, Δpdc5::PGAL7-FjTAL, Δaro10::PGAL1, 10-ARO4G226S-ARO7G141S-G418, gal80::TRP1; rDNA:: PhCHS-PGAL10-PALD5-MsCHI-PARO7-Pc4CL-PTDH3-FjTAL-HIS; XI-1::PTEF2-AtATR2-TFBA1-TTDH2-PAL2-PGAL10-PGAL1-AtC4H-TGPM1-TADH1-CYB5-PPGK1; ΔTAT1::(TTDH3-ALD6-PADH2) + (PSSA1-SeACSL641D-TTAT1) | This lab |

| B7-D9-01 | HB52, Ty2:: PhCHS-PGAL10-PALD5-MsCHI-PARO7-Pc4CL-URA-LEU; | This study |

| PY26 | Shuttle plasmid with TEF1 and GPD1 promoters, Ampr,Δura3 | This lab |

| PY26-01 | Shuttle plasmid with gene PhCHS、MsCHI and Pc4CL, contains both labels URA and LEU | This study |

Table 2.

Primers used in this study

| Primer name | Primer sequence (5′–3′) |

|---|---|

| Ty2-1F | Cactctatgattaggtagccacactatgcagaacc |

| Ty2-1R | Cgtatgagtgttacttcggcaggtcgccgc |

| Ty2-2F | Gccgaagtaacactcatacgccatccttaaagacctg |

| Ty2-2R | Ggctacctaatcatagagtgcatatgtttgtcttgataggcaac |

| Ty2-F | Gtgtccgcgctgagggtttaatg |

| Ty2-R | Gtataggaacttcacttcaggtctgagtgcg |

Media and culture conditions

The 24-, 48-, and 96-deep-well plate media and shake flask cultures used YPD liquid medium (20 g/L tryptone, 10 g/L yeast extract, 20 g/L glucose), the solid culture medium includes an additional 2% agar. For well plate culture, single colonies are picked and transferred into separate wells, then incubated at 30 °C and 220 r/min for 120 h. For shake flask fermentation, a single colony is picked from the YPD solid medium and inoculated in 5 mL of YPD liquid medium. It is then incubated at 30 °C and 220 r/min for 14–16 h until logarithmic growth. After that, the seed solution was transfered to a 2% volume ratio to 25 mL of YPD liquid medium and cultivated for 120 h at 30 °C and 220 r/min.

Bioreactor Cultivation: a single colony of the mutant strain was inoculated into a 250 mL shake flask containing 25 mL YPD liquid medium and cultured at 30 °C and 220 r/min for 24 h. Then, transfer the seed solution in a 4% volume ratio to a 500 mL shake flask containing 100 mL YPD liquid medium and cultured at 30 °C and 200 r/min for 24 h. Then, a secondary seed solution was inoculated into a 5 L bioreactor containing 2.5 L YPD liquid medium at a volume ratio of 4%. A feed-type batch culture was established at a flow rate of 5 mL/min at 30 °C while using ammonia to maintain pH at 5.5. The feeding medium contained 600 g/L glucose, 0.56 g/L Na2SO3, 7 g/L K2SO4, 10.24 g/L MgSO4·7H2O, 18 g/L KH2PO4, 20 mL/L trace element A (including 5.75 g/L ZnSO4·7H2O, 2.9 g/L CaCl2·2H2O, 2.8 g/L FeSO4·7H2O, 0.48 g/L NaMoO4·2H2O, 0.47 g/L CoCl2·6H2O, 0.32 g/L MnCl2·4H2O, and 80 mL 0.5 M EDTA, adjusted to pH 8.0), and 24 mL/L trace element B (including 0.02 g/L p-aminobenzoic acid, 0.05 g/L biotin, 1 g/L calcium pantothenate, 1 g/L nicotinic acid, 1 g/L thiamine HCl, 1 g/L pyridoxal HCl and 25 g/L myo-inositol) (Li et al. 2022a, b). The aeration volume was set to 1 vvm, and the temperature was maintained at 30 °C. The stirring speed should be controlled between 200–600 r/min to maintain the dissolved oxygen level at approximately 30%. After about 12 h, when the initial glucose was depleted, supplementation began at an infusion rate of 10 mL/h until it was completed within 72 h.

ARTP mutagenesis

The strain was cultured to logarithmic growth phase with an OD600 of about 6. Then, 1 mL of culture broth was centrifuged and the supernatant was discarded. The cells were washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at pH 7.4 to remove the culture medium, then resuspended in PBS containing 5% glycerol and diluted to produce a suspension with concentration between 10–6 and 10–7. Subsequently, 10 µL of the suspension was aspirated and applied onto a fully cauterized sterile carrier before being irradiated in an ARTP machine for durations of 0, 20, 40, 60, 80, 85, 90, 95, and 100 s. After processing the samples, the EP tubes containing the carriers were shaken continuously for 3–5 min to ensure that the bacteria attached to them were fully suspended. The control group consisted of a bacteria solution irradiated for 0 s. Then, the bacterial solution was diluted into gradients up until 10–3 (strains without mutations included) and three YPD solid mediums were used per gradient. These YPD solid media were incubated in a constant temperature incubator at 30 °C for 4 days to calculate the number of single colonies and determine lethality (Yun et al. 2022).

A represents the single colony count of the control strain without ARTP treatment on the YPD solid culture medium, while B represents the single colony count of the mutated strain on the YPD solid culture medium, both of which are counted under the same dilution gradient.

Establishment of the high-throughput screening procedure

The (2S)-naringenin standard was dissolved in 100% ethanol to create a standard master batch with a concentration of 10 g/L. Solutions of (2S)-naringenin at nine different concentrations were then prepared in a YPD medium, and 100 µL of each (2S)-naringenin solution was pipetted into transparent 96-shallow-well plates. Then, 100 µL of 4 M KOH was added and allowed to react with (2S)-naringenin at room temperature for 5, 10, and 15 min. The OD410 values of different concentrations of (2S)-naringenin solution after reacting with KOH were determined using a microplate reader, and a correlation curve was plotted.

The HTS method was used to screen high titer (2S)-naringenin strains. The mutagenic bacterial suspension was diluted gradiently and applied onto a YPD solid medium. When single colonies grew out, they were picked into 96-deep-well plates containing 1 mL of YPD liquid medium using a QPix 420 analyzer (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) and incubated for 120 h at 30 °C and 220 r/min. After centrifugation using a well plate centrifuge (Beckman, Brea, CA, USA), 100 µL of supernatant was aspirated using a fully automated pipetting station (CANTUS SCREEN High Throughput Liquid Handling System, Shanghai Hanzandi Life Sciences Co, Chinese) and the absorbance at 410 nm was determined with a microplate reader (Biotek Synergy H1, USA). The absorbance at 410 nm was determined using a microplate reader again after adding an equal volume (100 µL) of potassium hydroxide, and the two absorbance values were subtracted to eliminate background interference. Higher absorbance values indicated higher production (2S)-naringenin; the strain with the highest 1% absorbance value was selected for secondary screening. Strains with higher OD410 differences in the 96-deep-well plates were streaked on a YPD solid medium and incubated at 30 °C for 4 days. A single colony of the screened mutagenic strains was picked and incubated in a conical flask containing 5 mL YPD medium for approximately 14 to 16 h. It was then transferred to shake flasks with an inoculum ratio of 1% (v/v) in 25 mL YPD liquid medium and incubated for 120 h at 30 °C and 220 r/min. Fermentation continued for 120 h before samples were taken for analysis of (2S)-naringenin production by HPLC (LC-20 AT High Performance Liquid Chromatography, Shimadzu Corporation, Japan).

Analysis methods

The titer of (2S)-naringenin in the fermentation broth was determined using HPLC. Initially, the fermentation broth was mixed with an equal volume of methanol and vigorously shaken for sufficient extraction. It was then centrifuged at 12,000 r/min for 2 min, and the resulting supernatant was passed through a 0.22 μm nylon filter membrane. To determine intracellular levels of (2S)-naringenin, 1 mL of fermentation broth was centrifuged at 12,000 r/min for 1 min. The supernatant was removed and the bacteria precipitation was washed twice with distilled water. Then, an equal volume of glass beads (0.22 μm) and 1 mL of methanol were added to it. This mixture underwent fragmentation with FastPrep-24 5G (MP Biomedicals Co., Ltd., Illkirch Graffenstaden, France). Subsequently, the samples were centrifuged at 12,000 r/min for 2 min and the resulting supernatant was filtered through a 0.22 μm nylon membrane (Gao et al. 2020; Li et al. 2021). The sample was detected using a Shimadzu LC-20A with an InertSustain ODS-3 C18 (4.6 × 250 mm, 5 μm) column and aSPD-20A UV detector. (2S)-Naringenin was detected in liquid phase by gradient elution with mobile phase A (water-1‰ trifluoroacetic acid) and phase B (acetonitrile-1‰ trifluoroacetic acid), with phase B at 10–40% for 0–10 min, phase B at 40–60% for 10–20 min and held for 3 min, phase B at 60–10% for 23–25 min and held for 2 min. The gradient elution was carried out at a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min, with an injection volume of 10 μL and a column temperature of 40 °C. The detection wavelength for (2S)-naringenin was set as 290 nm (Chengcheng et al. 2021).

Results and discussion

Strain mutagenesis and lethality assays

In recent years, physical mutagenesis technologies have been developing rapidly, and atmospheric and room temperature plasma (ARTP) mutagenesis is widely used in the field of mutation breeding due to its advantages of a high mutation rate, simple instrument operation, safety, and harmlessness (Zhang et al. 2015). The principle of ARTP is that under room temperature and pressure conditions, a large number of plasma streams generated by high-purity helium (He) alter the permeability of microbial cell membranes leading to DNA damage. This forces the cells to initiate a highly fault-tolerant SOS repair process, which generates various mismatches during the repair process and results in numerous mutant strains (Zhang et al. 2014). Currently, there are several mature ARTP mutation-breeding apparatuses available that are easy to operate and provide a powerful tool for mutating microorganisms (Ottenheim et al. 2018).

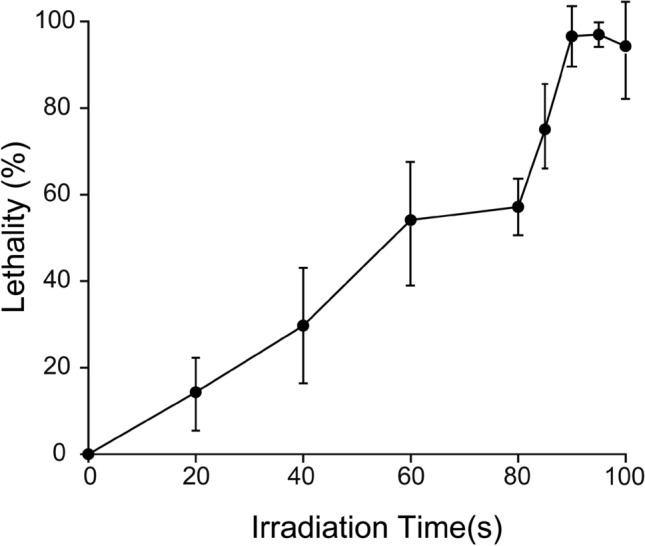

Exposure to ARTP irradiation for a certain period of time can lead to DNA damage in microbial cells, resulting in an increased number of mutants. ARTP mutagenesis was performed on strain HB52, which produces (2S)-naringenin. The mutagenized bacterial solution was diluted in a gradient and applied onto a YPD solid medium, which was then incubated at a constant temperature of 30 °C for 4 days. After growing single colonies, the lethality of the strains was calculated under different mutagenic treatment times using the plate counting method. As shown in Fig. 1, the lethality rate exceeded 50% after an irradiation time of 80 s. After increasing the irradiation time from 80 to 90 s, the lethality rate sharply rose to 96.57% and reached 96.97% at 95 s. Generally, a lethality rate of over 90% indicates a higher likelihood of strain damage and mutation; therefore, the time for subsequent treatment was set at 90 s and then 95 s.

Fig. 1.

Effect of irradiation time on strain HB52 lethality. The lethality rate of S. cerevisiae under different treatment times was compared with untreated strains. Each experiment was repeated three times. After treatment for 90 s and 95 s, the lethality rate reached 96.57% and 96.97%, respectively. Few single colonies survived after treatment for 100 s

Establishment of high-throughput screening procedure

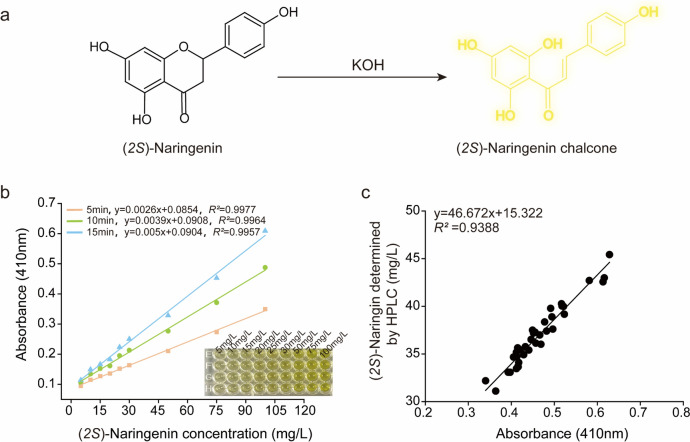

As a dihydro-flavonoid, (2S)-naringenin is easily ring-opened and hydrogenated in strong alkaline solutions (KOH), converting to the corresponding isomer (2S)-naringenin chalcone (Tang et al. 2011), which exhibits a yellow-orange color (Fig. 2a). Therefore, when a strong alkali is added to a solution containing (2S)-naringenin (usually a fermentation solution), the color of the solution turns yellow. The higher the concentration of (2S)-naringenin, the darker the color becomes. The visual method can be used for screening according to the color development results, but it may lead to inaccurate screening results. Therefore, a microplate reader is still needed for more accurate detection.

Fig. 2.

Establishment of high-throughput screening procedure. a (2S)-Naringenin chalcone is generated by the reaction of (2S)-naringenin with strong alkali (KOH). b Correlation curve between (2S)-naringenin concentration and OD410 (Different concentrations of (2S)-naringenin were diluted using YPD liquid medium). c Correlation between OD410 and (2S)-naringenin titer (Detected by HPLC) in the same strain. S. cerevisiae strains were randomly selected to detect OD410 using a microplate reader and (2S)-naringenin titer using HPLC; the distribution range of OD410 was 0.3–0.7, and the distribution range of (2S)-naringenin titer was 30–50 mg/L

The correlation between the concentration of (2S)-naringenin and OD410 at different reaction times was verified to ensure that the accuracy of the HTS method was not affected by different treatment times. As shown in Fig. 2b, the OD410 of the reaction solution increased with increasing (2S)-naringenin concentration and exhibited a good correlation between the concentration of (2S)-naringenin and OD410 values from 5 to 15 min. It demonstrates good sensitivity in the range of 0–100 mg/L (2S)-naringenin concentration. Therefore, it is feasible to use a microplate reader to directly detect the absorbance value of (2S)-naringenin after its reaction with KOH as a preliminary screening assay for determining the titer of (2S)-naringenin.

To validate the reliability of this high-throughput screening method, it is essential to establish a correlation between the titer of (2S)-naringenin and strain OD410 values at different positions in 96-deep-well plates. The mutagenized monoclonal strains were inoculated into 96-deep-well plates and incubated for 5 days. Subsequently, the OD410 of the fermentation broth was determined using a microplate reader, while the titer of (2S)-naringenin was determined through HPLC analysis. As shown in Fig. 2c, a strong positive correlation was observed between the quantified titer of (2S)-naringenin determined by HPLC and the OD410 obtained after the color development reaction. This confirms that this method demonstrates efficiency, simplicity, and accuracy, and can be effectively used for high-throughput screening of excellent strains producing (2S)-naringenin.

Selection of well plate carriers and high-throughput preliminary screening

Usually, high-throughput analysis is performed in 96-well microtiter plates, while cultivation is performed in 24, 48, or higher-throughput 96-deep-well plates. Generally, the volume of liquid used in 24-deep-well plates is 3 mL (Zhou et al. 2019), in 48-deep-well plates, is 1.5 mL (Meng et al. 2021), and in 96-deep-well plates is 1 mL (Luo et al. 2017). Insufficient culture medium can impede growth and hinder subsequent testing, while excessive liquid may disrupt oxygen transfer in the fermentation broth and cause overflow, leading to potential cross-contamination. Different engineered S. cerevisiae strains grow at different rates and require different volumes of culture media and oxygen. More importantly, the accumulation of (2S)-naringenin varies across different well plates, with excessively high titers exceeding the upper detection limit of the color reaction, while insufficient titers lead to a decrease in screening sensitivity. Therefore, it is imperative to assess the accumulation of (2S)-naringenin in different well plates and select an appropriate deep-well plate for subsequent screening.

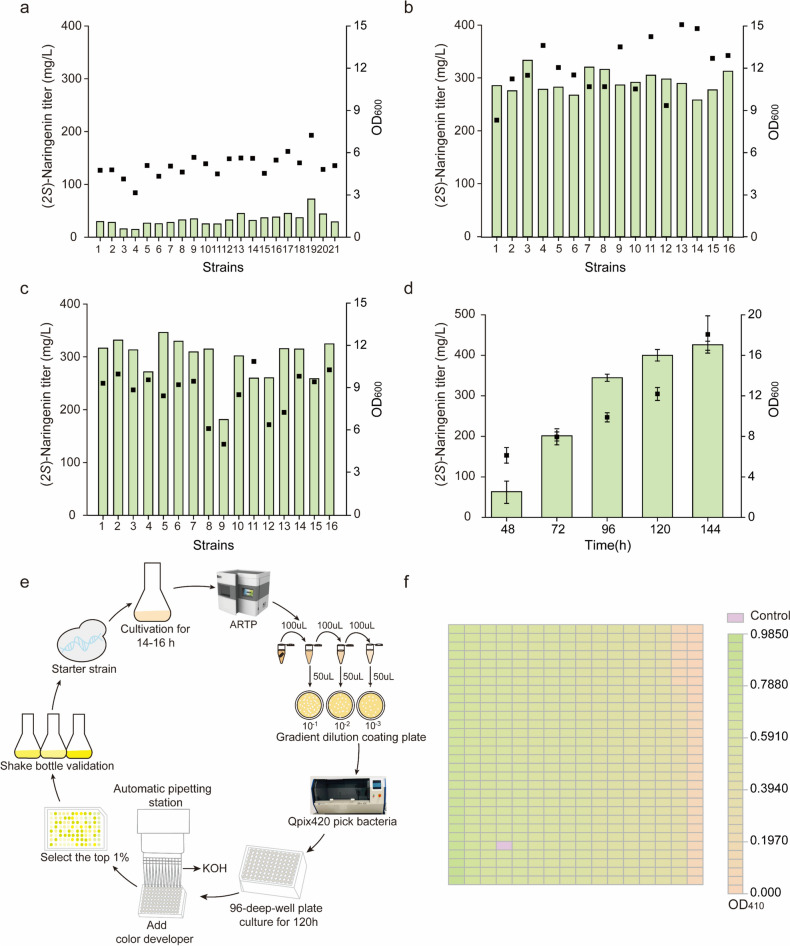

The results showed that the titer of (2S)-naringenin did not significantly differ between 24- and 48-deep-well plates and shake flasks, while the titer of 96-deep-well plates decreased significantly due to the small volume but still remained within the sensitive linear range of the colorimetric reaction (Fig. 3a–c). Considering the screening throughput, the 96-deep-well plates were selected. In this study, the strains irradiated with ARTP for 90 s and 95 s were inoculated onto a YPD solid medium. Consequently, the mutagenized strains were screened using a high-throughput screening program method outlined in Sect. “Establishment of the high-throughput screening procedure”, resulting in the identification of a total of 72 mutants with OD410 values surpassing starting strains from a pool containing approximately 9600 mutants (Fig. 4a–e).

Fig. 3.

Selection of well plate and schematic diagram of high-throughput primary screening. a Titer of (2S)-naringenin in 96-well-plates of the starting strain HB52. 21 strains of S. cerevisiae were randomly selected from 96-well plates to prepare samples, and the titer of (2S)-naringenin was detected by HPLC. b Titer of (2S)-naringenin in 48-well -plates of the starting strain HB52. 16 strains of S. cerevisiae were randomly selected from 48-well plates to prepare samples, and the titer of (2S)-naringenin was detected by HPLC. c Titer of (2S)-naringenin in 24-well plates of the starting strain HB52. 16 strains of S. cerevisiae were randomly selected from 24-well plates to prepare samples, and the titer of (2S)-naringenin was detected by HPLC. d (2S) -Naringenin titer of the starting strain HB52 in a 250 mL shake flask. The (2S)-naringenin titer of the starting strain HB52 increased with time, reaching 430.26 mg/L (extracellular concentration) at 144 h. The black squares represent OD600. e Schematic diagram of the high-throughput screening process. f Results of the first round of ARTP mutagenesis screening (OD410 value). Different colors represent different OD410, gradually increasing from pink to green, with purple representing the control OD410 (0.75)

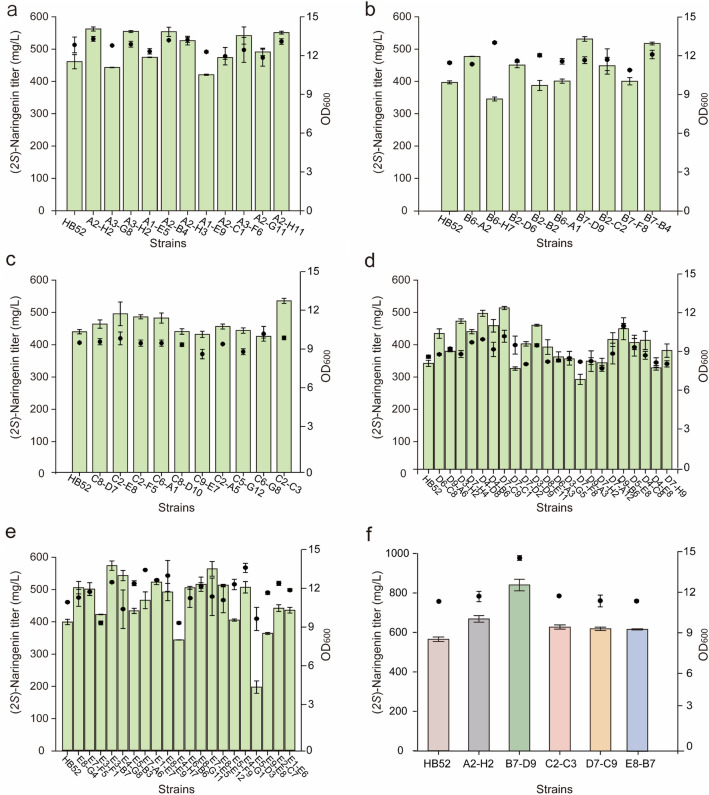

Fig. 4.

96-well plate high-throughput primary screening. a–e Results of the first (a), second (b), third (c), fourth (d), and fifth (e) rounds of secondary screening. The strains obtained from the preliminary screening were subjected to 250 mL shake flask secondary screening and the (2S)-naringenin titer (extracellular) obtained were detected using HPLC. f The high-yield strains obtained from the secondary screening were verified by shaking flask fermentation. The optimal strains obtained by secondary screening were cultured in a shake flask, and the intracellular and extracellular (2S)-naringenin concentration was detected; from left to right, they were 565.06 mg/L, 669.52 mg/L, 841.5 mg/L, 628.2 mg/L, 619.53 mg/L, and 617.77 mg/L. The black squares represent OD600

Traditional screening methods for high-titer strains of flavonoids mainly rely on HPLC detection, which is time-consuming and challenging for large-scale screening. Currently, high-throughput screening methods are widely utilized in the screening of a large amount of mutants generated by random mutagenesis (Luwen et al. 2023; Meng and Peng 2023). The high-throughput method used in this study utilized inexpensive and easy-to-prepare KOH as a chromogenic agent, which exhibited evident color changes when mixed with the fermentation broth. The combination of automatic bacterial collection and pipetting station can rapidly detect a large number of samples. Additionally, the treatment of different flavonoids with KOH resulted in distinct color changes, making this high-throughput screening method applicable to other flavonoids as well (Gao et al. 2020).

Identifying the mutant with the highest production in shake flasks

After several rounds of shake flask rescreening, five mutants (A2-H2, B7-D9, C2-C3, D7-B9, and E8-B7) were selected, and their titers of (2S)-naringenin were more than 20% higher than that of the starting strain HB52 (Fig. 4a–e). These five mutants were fermented in 250 mL shake flasks containing 25 mL of YPD liquid medium for 5 days. The starting strain was used as a control and experiments were performed in triplicate. Interestingly, mutant B7-D9 had the highest titer of (2S)-naringenin both extracellularly and intracellularly (intracellular and extracellular (2S)-naringenin titers are not shown separately; the total titer was 841.5 mg/L), which increased by 52.3% compared to the starting strain (Fig. 4f). This indicates the accuracy of the screening results. The production stability of the strains was verified through successive generation passages of these five mutants, and the results showed that the stability of the mutant strain was still better than that of the starting strain (data not shown). The experimental results indicate that the strain obtained through random mutagenesis using ARTP exhibits good stability and reproducibility.

Compared with ARTP mutation, traditional mutation breeding methods are complicated to operate and have low mutation rates. ARTP produces diverse mechanisms of damage to the genetic material, leading to the acquisition of a large number of multiple mutant phenotypes, which is beneficial for mutation breeding microorganisms with complex metabolic networks (Cao et al. 2017). However, detection using traditional high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) involves complex sample processing, which is laborious and time-consuming (Lim et al. 2018). Therefore, it is imperative to establish an efficient high-throughput screening method by combining well plate culture. Nevertheless, the limited volume and unstable titer of well plate cultures make it unsuitable as a basis for final screening. Consequently, the strains obtained from the preliminary screening need to be transferred to a shake flask amplification culture to obtain a stable yield (Cai et al. 2021).

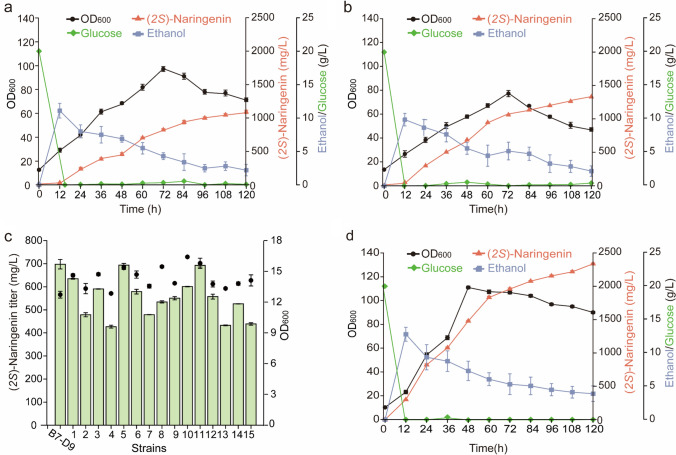

Comparison of B7-D9 and mutagenic starting strains in a 5 L bioreactor

The high titer strain B7-D9 obtained through mutagenesis and high-throughput screening was compared with the starting strain in a 5 L bioreactor. Compared with the starting strain, B7-D9 consumed all the basal glucose at 12 h (Fig. 5a and b). (2S)-Naringenin began to accumulate at 24 h, and its titer in the fermentation broth reached 1309.13 mg/L at 120 h, which was 19.8% higher than that of the starting strain. The OD600 reached 78.4 at 72 h, which was 18.25% lower than that of the starting strain. It then started to decline due to a lack of uracil (Ura), an essential substance for the growth of the strain. To address this issue, uracil synthesis genes were integrated into the multi-copy locus Ty2, and strain 5 was selected and cultured in a 5 L bioreactor (Fig. 5c). As shown in Fig. 5d, strain 5 with integrated uracil synthesis genes grew faster and better with an OD600 up to 111 at 60 h. Meanwhile, the titer of (2S)-naringenin reached 2336.85 mg/L at 120 h, which was 2.14 and 1.79 times higher than those of HB 52 and B7-D9, respectively.

Fig. 5.

Comparison of wild-type and B7-D9 mutant strains in a 5 L bioreactor. a Culturing of the starting strain HB52 in a 5 L bioreactor. b Changes of mutant strain B7-D9 in a 5 L bioreactor. c The (2S)-naringenin titer and OD600 of the strains with integrated uracil synthesis genes were measured in 250 mL shake flasks. Fifteen strains were randomly integrated with uracil synthesis genes and were incubated at 30 °C and 220 rpm for 5 days, and the (2S)-naringenin titer was detected by HPLC. d Changes of strain 5 with integrated uracil synthesis genes in a 5 L bioreactor. The starting strain, mutagenic high-yielding strain and the strain with integrated uracil synthesis genes were cultured in a 5 L bioreactor at 30 °C for 120 h, and the changes of glucose, ethanol, OD600 and the titer of (2S)-naringenin were determined with time

Although (2S)-naringenin production of strain B7-D9 was improved through mutagenesis and screening in this study, the specific genetic changes remain unclear and require further elucidation through genome annotation and transcriptomics (Pais et al. 2021; Kalra et al. 2023). At the same time, because natural flavonoids are secondary metabolites produced by plants to resist exogenous stimulation and microbial infection, they have certain toxicity to microbial host cells, resulting in limited improvement in titer. Adaptive laboratory evolution is another effective method for microbial mutagenesis breeding, which can be combined with iterative ARTP to screen for the best mutant strains (Jiang et al. 2020; Zhou et al. 2023). By comparing the genomics and transcriptomics of the original and mutated high-titer strains, it is possible to identify new gene targets and regulatory mechanisms involved in the evolution of cellular adaptations associated with (2S)-naringenin production (Kawai et al. 2019). Furthermore, these targets and mechanisms can also provide a new direction for synthesizing other flavonoids through metabolic modification.

Conclusion

The high-throughput screening method for screening high-titer (2S)-naringenin strains was established based on the KOH color reaction in this study. The high-titer mutant strain B7-D9 was successfully obtained using this method coupled with ARTP random mutation technology. The (2S)-naringenin titer of B7-D9 was 1.2-fold higher than that of the starting strain in a 5 L bioreactor. Through integrating uracil synthesis genes into strain B7-D9, the (2S)-naringenin titer was further increased to 2336.85 mg/L, which is 2.14 times higher than that of the starting strain. This HTS method combines automated high-throughput screening equipment, greatly improving screening efficiency and accuracy compared to traditional methods. The feasibility of this HTS method provides ideas for screening strains that produce similar substances. In the future, it could be combined with biosensors to link the titer with fluorescence intensity and scale up screening to 10 million scale using flow cytometry and microfluidics. However, due to the fact that most biosensors originate from prokaryotes, there are currently few biosensors successfully expressed and used for screening in S. cerevisiae, highlighting the necessity of optimizing and improving their performance, which is a challenging issue.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Foundation for Innovative Research Groups of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32021005), and the Starry Night Science Fund of Zhejiang University Shanghai Institute for Advanced Study (Grant No. SN-ZJU-SIAS-0013).

Author contributions

Q. G. and S. G. designed the study and wrote the manuscript. Q. G., W. Z., and J. Z. critically revised the manuscript. Q. G. performed the experiments and analyzed the results. J. Z. designed and supervised the project. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Data Availability

All data presented in this study is available from the correspoding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethical standards

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Contributor Information

Jianghua Li, Email: lijianghua@jiangnan.edu.cn.

Jingwen Zhou, Email: zhoujw1982@jiangnan.edu.cn.

References

- Akhter S, Arman MSI, Tayab MA, Islam MN, Xiao J. Recent advances in the biosynthesis, bioavailability, toxicology, pharmacology, and controlled release of citrus neohesperidin. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2022;23:1–20. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2022.2149466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai M, Wu Y, Qi H, He J, Wu Z, Xu H, Qiao M. Improving the level of the tyrosine biosynthesis pathway in Saccharomyces cerevisiae through HTZ1 Knockout and Atmospheric and Room Temperature Plasma (ARTP) Mutagenesis. ACS Synth Biol. 2021;10(1):49–62. doi: 10.1021/acssynbio.0c00448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai J, Wen H, Zhou H, Zhang D, Lan D, Liu S, Li C, Dai X, Song T, Wang X, He Y, He Z, Tan J, Zhang J. Naringenin: a flavanone with anti-inflammatory and anti-infective properties. Biomed Pharmacother. 2023;164:114990–115006. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2023.114990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao S, Zhou X, Jin W, Wang F, Tu R, Han S, Chen H, Chen C, Xie G-J, Ma F. Improving of lipid productivity of the oleaginous microalgae Chlorella pyrenoidosa via atmospheric and room temperature plasma (ARTP) Bioresour Technol. 2017;244(2):1400–1406. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2017.05.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chengcheng S, Guangjian L, Hongbiao L, Yunbin L, Shiqin Y, Jingwen Z. Enhancing flavan-3-ol biosynthesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Agric Food Chem. 2021;69(43):12763–12772. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.1c04489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frydman A, Liberman R, Huhman DV, Carmeli-Weissberg M, Sapir-Mir M, Ophir R, Sumner LW, Eyal Y. The molecular and enzymatic basis of bitter/non-bitter flavor of citrus fruit: evolution of branch-forming rhamnosyl-transferases under domestication. Plant J. 2013;73(1):166–178. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao S, Zhou H, Zhou J, Chen J. Promoter-Library-Based Pathway Optimization for Efficient (2S)-Naringenin [roduction from p-Coumaric Acid in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Agric Food Chem. 2020;68(25):6884–6891. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.0c01130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann M, Schneider TR, Pfeil A, Heinrich G, Lipscomb WN, Braus GH. Evolution of feedback-inhibited beta/alpha barrel isoenzymes by gene duplication and a single mutation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100(3):862–867. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0337566100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassing E-J, de Groot PA, Marquenie VR, Pronk JT, Daran J-MG. Connecting central carbon and aromatic amino acid metabolisms to improve de novo 2-phenylethanol production in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Metab Eng. 2019;56:165–180. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2019.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang G, Yang Z, Wang Y, Yao M, Chen Y, Xiao W, Yuan Y. Enhanced astaxanthin production in yeast via combined mutagenesis and evolution. Biochem Eng J. 2020;156:107519–107528. doi: 10.1016/j.bej.2020.107519. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Juca MM, Sales Cysne Filho FM, de Almeida JC, Mesquita DdS, de Moraes Barriga JR, Cilene Ferreira DK, Barbosa TM, Vasconcelos LC, Almeida Moreira Leal LK, Ribeiro Honorio Junior JE, Mendes Vasconcelos SM. Flavonoids: biological activities and therapeutic potential. Biochem Eng J. 2020;34(5):692–705. doi: 10.1080/14786419.2018.1493588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalra S, Peyser R, Ho J, Babbin C, Bohan N, Cortes A, Erley J, Fatima M, Flinn J, Horwitz E, Hsu R, Lee W, Lu V, Narch A, Navas D, Kalu I, Ouanemalay E, Ross S, Sowole F, Specht E, Woo J, Yu K, Coolon JD. Genome-wide gene expression responses to experimental manipulation of Saccharomyces cerevisiae repressor activator protein 1 (Rap1) expression level. Genomics. 2023;115(3):110625–110635. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2023.110625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawai K, Kanesaki Y, Yoshikawa H, Hirasawa T. Identification of metabolic engineering targets for improving glycerol assimilation ability of Saccharomyces cerevisiae based on adaptive laboratory evolution and transcriptome analysis. J Biosci Bioeng. 2019;128(2):162–169. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiosc.2019.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koopman F, Beekwilder J, Crimi B, van Houwelingen A, Hall RD, Bosch D, van Maris AJA, Pronk JT, Daran J-M. De novo production of the flavonoid naringenin in engineered Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microb Cell Fact. 2012;11:155–169. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-11-155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopustinskiene DM, Jakstas V, Savickas A, Bernatoniene J. Flavonoids as anticancer agents. Nutrients. 2020;12(2):457–457. doi: 10.3390/nu12020457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee DYW, Zhang W-Y, Karnati VVR. Total synthesis of puerarin, an isoflavone C-glycoside. Tetrahedron Lett. 2003;44(36):6857–6859. doi: 10.1016/S0040-4039(03)01715-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li M, Kildegaard KR, Chen Y, Rodriguez A, Borodina I, Nielsen J. De novo production of resveratrol from glucose or ethanol by engineered Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Metab Eng. 2015;32:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2015.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Gao S, Zhang S, Zeng W, Zhou J. Effects of metabolic pathway gene copy numbers on the biosynthesis of (2S)-naringenin in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biotechnol. 2021;325:119–127. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2020.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Lyv Y, Zhou S, Yu S, Zhou J. Microbial cell factories for the production of flavonoids–barriers and opportunities. Bioresour Technol. 2022;360:127538–127549. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2022.127538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Ma W, Lyv Y, Gao S, Zhou J. Glycosylation modification enhances (2S)-Naringenin Production in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. ACS Synth Biol. 2022;11(7):2339–2347. doi: 10.1021/acssynbio.2c00065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim HG, Jang S, Jang S, Seo SW, Jung GY. Design and optimization of genetically encoded biosensors for high-throughput screening of chemicals. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2018;54:18–25. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2018.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W, Zhang B, Jiang R. Improving acetyl-CoA biosynthesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae via the overexpression of pantothenate kinase and PDH bypass. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2017;10:41–50. doi: 10.1186/s13068-017-0726-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q, Yu T, Li X, Chen Y, Campbell K, Nielsen J, Chen Y. Rewiring carbon metabolism in yeast for high level production of aromatic chemicals. Nat Commun. 2019 doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-12961-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu M, Liu S, Zhao L, Pei J. Screening β-glucosidase and α-rhamnosidase for biotransformation of naringin to naringenin by the one-pot enzymatic cascade. Enzyme Microb Technol. 2023;167:110239–110248. doi: 10.1016/j.enzmictec.2023.110239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Z, Zeng W, Du G, Liu S, Fang F, Zhou J, Chen J. A high-throughput screening procedure for enhancing pyruvate production in Candida glabrata by random mutagenesis. Bioprocess Biosyst Eng. 2017;40(5):693–701. doi: 10.1007/s00449-017-1734-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luwen Z, Jiawei T, Meiqing F, Shaoxin C. Engineering methyltransferase and sulfoxide synthase for high-yield production of ergothioneine. J Agric Food Chem. 2023;71(1):671–679. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.2c07859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng C, Peng B. Establishment of a high-throughput screening platform to screen Schizochytrium sp. with a high yield of DHA. Algal Res. 2023;74:103201–103212. doi: 10.1016/j.algal.2023.103201. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meng L, Gao X, Liu X, Sun M, Yan H, Li A, Yang Y, Bai Z. Enhancement of heterologous protein production in Corynebacterium glutamicum via atmospheric and room temperature plasma mutagenesis and high-throughput screening. J Biotechnol. 2021;339:22–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2021.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ottenheim C, Nawrath M, Wu JC. Microbial mutagenesis by atmospheric and room-temperature plasma (ARTP): the latest development. Bioresour Bioprocess. 2018;5:12–26. doi: 10.1186/s40643-018-0200-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pais P, Oliveira J, Almeida V, Yilmaz M, Monteiro PT, Teixeira MC. Transcriptome-wide differences between Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Saccharomyces cerevisiae var. boulardii: clues on host survival and probiotic activity based on promoter sequence variability. Genomics. 2021;113(2):530–539. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2020.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandey RP, Parajuli P, Koffas MAG, Sohng JK. Microbial production of natural and non-natural flavonoids: pathway engineering, directed evolution and systems/synthetic biology. Biotechnol Adv. 2016;34(5):634–662. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2016.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park SR, Yoon JA, Paik JH, Park JW, Jung WS, Ban Y-H, Kim EJ, Yoo YJ, Han AR, Yoon YJ. Engineering of plant-specific phenylpropanoids biosynthesis in Streptomyces venezuelae. J Biotechnol. 2009;141(3–4):181–188. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2009.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park SY, Yang D, Ha SH, Lee SY. Metabolic engineering of microorganisms for the production of natural compounds. Adv Biosyst. 2018;8(1):589069–589084. doi: 10.1002/adbi.201700190. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Salehi B, Fokou PVT, Sharifi-Rad M, Zucca P, Pezzani R, Martins N, Sharifi-Rad J. The therapeutic potential of naringenin: a review of clinical trials. Pharmaceuticals. 2019;12(1):11–29. doi: 10.3390/ph12010011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siddiqui MS, Thodey K, Trenchard I, Smolke CD. Advancing secondary metabolite biosynthesis in yeast with synthetic biology tools. FEMS Yeast Res. 2012;12(2):144–170. doi: 10.1111/j.1567-1364.2011.00774.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suastegui M, Guo W, Feng X, Shao Z. Investigating strain dependency in the production of aromatic compounds in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2016;113(12):2676–2685. doi: 10.1002/bit.26037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang D-M, Zhu C-F, Zhong S-A, Zhou M-D. Extraction of naringin from pomelo peels as dihydrochalcone’s precursor. J Sep Sci. 2011;34(1):113–117. doi: 10.1002/jssc.201000475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, Yang J, Zhang X-m, Zhou L, Liao X-L, Yang B. Practical synthesis of naringenin. J Chem Res. 2015;8:455–457. doi: 10.3184/174751915x14379994045537. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wei W, Zhang P, Shang Y, Zhou Y, Ye B-C. Metabolically engineering of Yarrowia lipolytica for the biosynthesis of naringenin from a mixture of glucose and xylose. Bioresour Technol. 2020;314:123726–123735. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2020.123726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yun J, Zabed HM, Zhang Y, Zhang G, Zhao M, Qi X. Improving tolerance and 1,3-propanediol production of Clostridium butyricum using physical mutagenesis, adaptive evolution and genome shuffling. Bioresour Technol. 2022;363:127967–127974. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2022.127967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Zhang X-F, Li H-P, Wang L-Y, Zhang C, Xing X-H, Bao C-Y. Atmospheric and room temperature plasma (ARTP) as a new powerful mutagenesis tool. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2014;98(12):5387–5396. doi: 10.1007/s00253-014-5755-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Zhang C, Zhou Q-Q, Zhang X-F, Wang L-Y, Chang H-B, Li H-P, Oda Y, Xing X-H. Quantitative evaluation of DNA damage and mutation rate by atmospheric and room-temperature plasma (ARTP) and conventional mutagenesis. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2015;99(13):5639–5646. doi: 10.1007/s00253-015-6678-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou G, Tian X, Lin Y, Zhang S, Chu J. Rational high-throughput system for screening of high sophorolipids-producing strains of Candida bombicola. Bioprocess Biosyst Eng. 2019;42(4):575–582. doi: 10.1007/s00449-018-02062-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou S, Hao T, Zhou J. Fermentation and metabolic pathway optimization to De Novo synthesize (2S)-naringenin in Escherichia coli. J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2020;30(10):1574–1582. doi: 10.4014/jmb.2008.08005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou K, Yu C, Liang N, Xiao W, Wang Y, Yao M, Yuan Y. Adaptive evolution and metabolic engineering boost lycopene production in Saccharomyces cerevisiae via enhanced precursors supply and utilization. J Agric Food Chem. 2023;71(8):3821–3831. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.2c08579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data presented in this study is available from the correspoding author upon reasonable request.