Abstract

Balamuthia mandrillaris is a free-living ameba and an opportunistic agent of granulomatous encephalitis in humans and other mammalian species. Other free-living amebas, such as Acanthamoeba and Hartmannella, can provide a niche for intracellular survival of bacteria, including the causative agent of Legionnaires' disease, Legionella pneumophila. Infection of amebas by L. pneumophila enhances the bacterial infectivity for mammalian cells and lung tissues. Likewise, the pathogenicity of amebas may be enhanced when they host bacteria. So far, the colonization of B. mandrillaris by bacteria has not been convincingly shown. In this study, we investigated whether this ameba could host L. pneumophila bacteria. Our experiments showed that L. pneumophila could initiate uptake by B. mandrillaris and could replicate within the ameba about 4 to 5 log cycles from 24 to 72 h after infection. On the other hand, a dotA mutant, known to be unable to propagate in Acanthamoeba castellanii, also did not replicate within B. mandrillaris. Approaching completion of the intracellular cycle, L. pneumophila wild-type bacteria were able to destroy their ameboid hosts. Observations by light microscopy paralleled our quantitative data and revealed the rounding, collapse, clumping, and complete destruction of the infected amebas. Electron microscopic studies unveiled the replication of the bacteria in a compartment surrounded by a structure resembling rough endoplasmic reticulum. The course of intracellular infection, the degree of bacterial multiplication, and the ultrastructural features of a L. pneumophila-infected B. mandrillaris ameba resembled those described for other amebas hosting Legionella bacteria. We hence speculate that B. mandrillaris might serve as a host for bacteria in its natural environment.

Balamuthia mandrillaris is a free-living ameba and an opportunistic agent of lethal granulomatous amebic encephalitis (GAE) in humans and other mammalian species (51). Although originally described as a leptomyxid ameba (50), molecular genetics data indicate that B. mandrillaris is more closely related to Acanthamoeba castellanii than to other members of the order Leptomyxida (3). Since B. mandrillaris amebas have now been found outside of infected individuals in soil material (45), it became necessary to assess their potential as a host for pathogenic bacteria. So far, only nonquantitative studies estimating the resistance of B. mandrillaris for the Chlamydia-like bacterium Waddlia chondrophila and the susceptibility for infection by a poorly characterized bacterial parasite of a Naegleria sp. (Schizopyrenida: Vahlkampfiidae) have been performed (30, 31).

Legionella pneumophila bacteria are facultative intracellular parasites of alveolar macrophages and epithelial cells causing Legionnaires' disease, a severe pneumonia, in humans (17). Ubiquitous to freshwater environments, legionellae infect and multiply within protozoa, such as free-living amebas (36). At least 14 different ameboid species, for example, members of the genera Acanthamoeba, Hartmannella, Naegleria, and Dictyostelium, have been found to support growth of these bacteria (15, 20, 46). Furthermore, legionellae have been coisolated with protozoa or have been found in typical habitats of free-living protozoa, such as freshwater environments and moist soil (4, 15, 16, 21, 28, 35, 40). Infection of amebas by legionellae enhances bacterial propagation in several ways. First, L. pneumophila derived from a coculture with amebas or coinoculated with amebas into experimental animal hosts display enhanced infectivity for mammalian cells and lung tissues in situ (8, 9, 11, 13). Secondly, as with other pathogenic bacteria, such as Mycobacterium spp., associating with protozoa in the environment, protozoa harboring legionellae may serve as transmission vectors (6, 12, 47). Thirdly, the bacteria inside an ameboid cyst can more easily survive unfavorable conditions, such as high temperature or treatment with disinfectants (5, 26, 37). On the other hand, the pathogenicity of ameba may be enhanced when hosting bacteria, as shown for Acanthamoeba spp. naturally or artificially infected with bacterial endosymbionts (18).

In this study, we investigated whether B. mandrillaris ameba can serve as a host for L. pneumophila bacteria. Our findings indicate that L. pneumophila may indeed infect B. mandrillaris organisms, thereby leading to rounding and detachment of the amebic host and, finally, to its disintegration. The bacteria remained and multiplied within large vacuoles studded with a rough endoplasmic reticulum in a manner similar to that described for infections with Hartmannella, Acanthamoeba, and Dictyostelium (2, 19, 20, 46).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ameboid and bacterial strains and growth conditions.

B. mandrillaris strain CDC-V039 was cultured in Chang Special Medium (34). Virulent L. pneumophila strains 130b (ATCC BAA-74) and JR32 and the avirulent isogenic JR32 dotA mutant (LELA 3118) were routinely grown on buffered charcoal-yeast extract agar for 2 days at 37°C (14, 41). The JR32 wild type and JR32 dotA were kindly provided by Howard Shuman, Columbia University, New York, N.Y.

Cocultivation and light microscopy.

B. mandrillaris was infected with L. pneumophila in the following manner: 105 amebas/ml were seeded in B. mandrillaris infection medium (1:1 mix of Chang Special Medium and A. castellanii infection medium) (32) and 103 L. pneumophila bacteria/ml in B. mandrillaris infection medium were added. To assess intracellular growth, cocultures (6 ml in 6-cm-diameter petri dishes; Greiner, Nürtingen, Germany) were analyzed by phase-contrast microscopy without fixation. Microscopy was performed directly with an inverted microscope (Axiovert 25; Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) at the time points indicated in Results using a ×32 phase contrast objective. Photographs were taken with Kodak Ektachrome 64 T color-reversal film with a Contax 167 MT camera. For bisbenzimide-staining, amebas and bacteria were seeded at the concentrations given above into eight-well chamber slides (200 μl/well; Nunc, Naperville, Ill.). At the indicated time points, the wells were gently washed two times with warm phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.3) to remove remaining extracellular bacteria, air-dried, fixed with acetic acid-methanol (1:4), and stained with bisbenzimide H 33258 (Riedel-de Haën, Seelze, Germany) as described previously (29). Microscopy was performed with a Zeiss Axioskop 2 equipped with fluorescence optics, a 450-to-490-nm excitation filter and a 520-nm barrier filter (filter set 09; Zeiss) using a ×100 oil immersion objective. Photographs were obtained with an AxioCam digital camera and AxioVision V 2.05 software (Zeiss).

Determination of bacterial numbers.

To assess intracellular growth of L. pneumophila quantitatively, the amebas were seeded with or without bacteria in 24-well plates at the concentrations given above (2 ml/well; Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark). At the time points indicated in Results, the numbers of intracellular plus extracellular bacteria per ml were determined as follows. The remaining organisms were suspended by vigorous scraping before 1 ml/well was removed and further disrupted on a vortex shaker. Serial 1:10 dilutions in PBS were plated on buffered charcoal-yeast extract agar, and the colonies that appeared were counted after 72 to 96 h of incubation at 37°C.

Electron microscopy.

For transmission electron micrographs of uninfected and L. pneumophila-infected B. mandrillaris amebas, the culture medium was replaced by glutaraldehyde (2.5% [vol/vol]) buffered with HEPES (0.05 M; pH 7.2), fixed for 1 h at room temperature, and then stored for 5 to 7 days at 4°C in the same solution. The cells were first embedded in agarose by mixing equal volumes of cells and low-melting-point agarose (3% [wt/vol] in PBS), postfixed with OsO4 (1% in double-distilled H2O; Plano, Wetzlar, Germany) and block stained with uranyl acetate (2% [wt/vol] in double-distilled H2O; Merck, Darmstadt, Germany). The samples were then dehydrated stepwise in graded alcohol and embedded in LR White resin (Science Services, Munich, Germany) which was polymerized at 60°C overnight. Ultrathin sections were prepared with an ultramicrotome (Ultracut S; Leica, Germany) and placed on uncovered 400-mesh grids or on pioloform-covered 100-mesh grids. The sections were stained with lead citrate and stabilized with ca. 1.5 nm carbon (carbon evaporation, BAE 250; BalTec, Liechtenstein). Transmission electron microscopy was performed with an EM 902 (Zeiss), and the images were digitized using a slow-scan charge-coupled device camera (Proscan; Scheuring, Germany).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Though L. pneumophila bacteria are also found extracellularly in their natural aquatic environment (e.g., in biofilms), attention has focused on their intracellular habitats, as these are obligatory for multiplication. Legionellae are parasitic for a variety of amebic species, a strategy which is important for survival in the environment and which preadapts these bacteria for their disease-causing invasion of alveolar macrophages. B. mandrillaris, a free-living ameba and ubiquitous opportunistic agent of lethal granulomatous encephalitis, has been discovered only recently. Its potential as a host for pathogenic bacteria is still open for investigation.

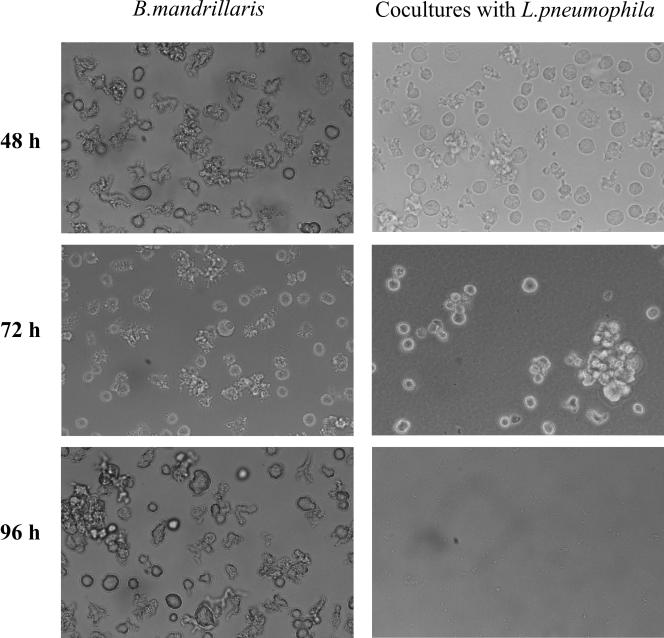

By using several microscopic approaches and quantitative determination of bacterial numbers, we investigated whether L. pneumophila bacteria are able to infect and multiply within B. mandrillaris amebas. Light microscopic observations of cocultures of B. mandrillaris and L. pneumophila 130b revealed within 48 h a rounding of the ameba compared to the majority of ameboid trophozoites seen with the noninfected control (Fig. 1). After 72 h, the infected amebas appeared spherical and larger than the uninfected cells and were filled with the highly motile L. pneumophila bacteria. The infected B. mandrillaris organisms also tended to collapse and thereby clump together (Fig. 1). The surrounding medium was by then filled with bacteria. By 96 h, the amebas were totally destroyed and only some cell debris could be seen in the coinfection cultures (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Native preparations of B. mandrillaris cultured without or with L. pneumophila strain 130b for 48 h, 72 h, and 96 h. Primary magnification, ×164.

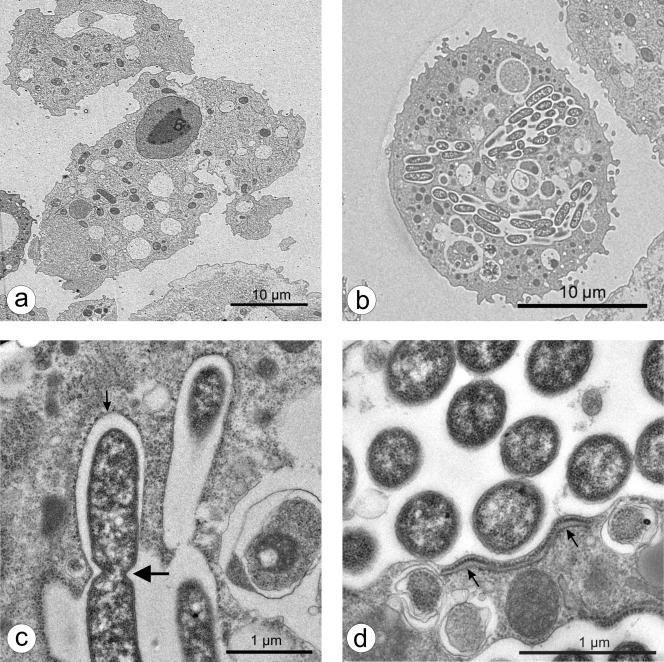

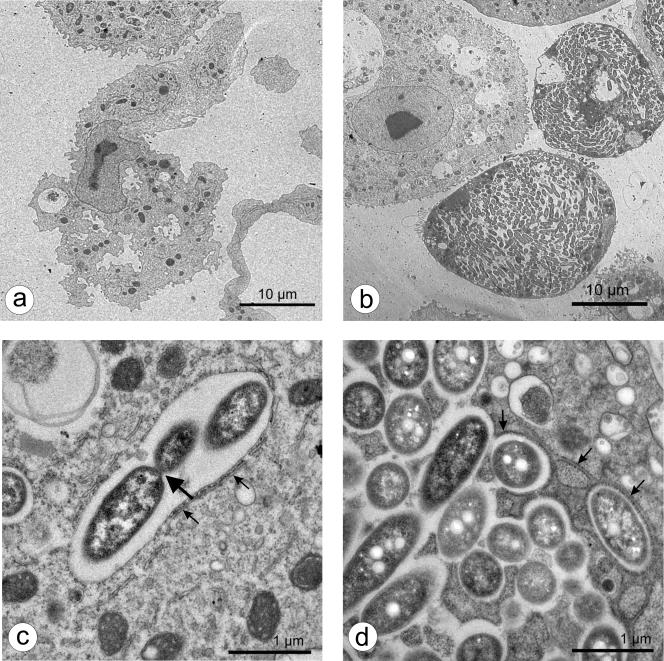

Furthermore, fixed preparations were stained with bisbenzimide, a DNA-specific stain binding to AT-rich regions, in order to envisage intracellular events in the ameba more clearly. Whereas fluorescent nuclei were the prominent feature of noninfected ameba, B. mandrillaris, which had been cocultured with L. pneumophila 130b for 72 h, also contained a number (usually one to three) of distinct, large, fluorescent cytoplasmic bodies (data not shown). Transmission electron micrographs (Fig. 2 and 3) revealed these cytoplasmic bodies to be large phagosomes containing abundant bacteria, ultimately filling the host cell (Fig. 2b and 3b). Some bacteria were clearly replicating by binary fission (Fig. 2c and 3c). No bacteria were found in the cytoplasm of intact, infected amebas. A host rough endoplasmic reticulum (rER) was regularly seen in close conjunction with the bacteria-loaded nascent phagosomes (Fig. 2c and d and Fig. 3c and d). This unique replicative phagosome, termed the ER-phagosome by some authors, has been described repeatedly (1, 2, 19, 24, 46, 48) and is suggested to be an essential cellular response in amebas as well as in macrophages hosting legionellae. It has been shown that shortly after uptake of the bacterium, the phagosome membrane associates with early secretory vesicles that are derived from the ER (25, 49). Subsequently, the phagosome becomes completely surrounded by rER and even acquires characteristics of the ER itself (33, 48, 49). Whether the rER supplies the bacteria with nutrients or possesses other functions remains to be clarified. “Coiling” during phagocytosis as described for macrophages and amebas when incorporating L. pneumophila (10, 23) was not observed but might have been missed at the chosen time points.

FIG. 2.

Transmission electron micrographs of B. mandrillaris cultured for 24 h without (a) or with (b to d) L. pneumophila 130b. Small arrows designate rough endoplasmic reticulum adjoined to the L. pneumophila-containing vacuole; the large arrow designates dividing bacteria.

FIG. 3.

Transmission electron micrographs of B. mandrillaris cultured for 72 h without (a) or with (b to d) L. pneumophila 130b. Small arrows designate rough endoplasmic reticulum adjoined to the L. pneumophila-containing vacuole; the large arrow designates dividing bacteria.

During the disruption of the infected ameba at different times postinfection and the counting of the number of bacterial CFU, it became evident that, after an initial lag phase, L. pneumophila strain 130b as well as the JR32 wild type had replicated in B. mandrillaris organisms about 1 to 2 log cycles from 24 to 48 h and a further 1 to 3 log cycles from 48 to 72 of cocultivation (Fig. 4). Hence, 4 to 5 log cycles of replication could be observed for L. pneumophila strain 130b and 2 log cycles could be observed for strain JR32 wild type over the entire infection period before the infected ameba were completely destroyed. Bacterial replication depended on the presence of amebas, as clearly shown by the continuous drop in CFU to below detection levels by 72 h in cultures of L. pneumophila 130b alone (Fig. 4, top). This rate of intracellular replication is comparable to those observed in other host amebas, such as A. castellanii (32), Dictyostelium discoideum (20), and Hartmannella vermiformis (27). Furthermore, an apathogenic L. pneumophila dotA mutant which multiplies neither in A. castellanii amebas nor in mammalian macrophages and which is deficient in all virulence features that require the Dot/Icm type IV protein secretion machinery (7, 22, 38, 39, 41, 42, 43, 52) was tested in the B. mandrillaris infection model. Compared to the L. pneumophila JR32 wild type, the dotA mutant did not show any increase in bacterial numbers within 72 h of coculture. Instead, JR32 dotA CFU dropped continuously from the start (Fig. 4, bottom), additionally corroborating the similarity of the infection process in B. mandrillaris with other free-living amebas and mammalian macrophages.

FIG. 4.

Intracellular infection by different L. pneumophila strains. (Top) CFU of L. pneumophila 130b (L.p.) in cultures of bacteria alone or in coculture with B. mandrillaris amebas. By 72 h, bacterial numbers in cultures without amebas had dropped below the detection level. (Bottom) The L. pneumophila JR32 wild type and L. pneumophila JR32 dotA mutant in coculture with B. mandrillaris amebas. Results are the means of CFU ± standard deviations for triplicate samples and are representative of results of three independent experiments.

Finding that L. pneumophila bacteria were able to infect and multiply within B. mandrillaris was astonishing, as it had been shown clearly that B. mandrillaris, in contrast to most free-living ameba (e.g., Acanthamoeba, Naegleria, Hartmannella, Vahlkampfia), cannot be grown on Escherichia coli-coated nonnutrient agar plates (50). Instead, B. mandrillaris ameba readily thrive on a large variety of eukaryotic cells (including murine macrophages and Acanthamoeba trophozoites) (44, 51; A. F. Kiderlen, unpublished results). Our findings confirm that L. pneumophila has singular means of invading and transforming potential host cells to its needs. The typical development of an ER endosome enclosing intracellular L. pneumophila may support this idea.

Thus, the provided data show that B. mandrillaris amebas can indeed harbor viable L. pneumophila and indicate that free-living Balamuthia amebas may serve as hosts for other pathogenic bacteria as well. Whether this renders B. mandrillaris more pathogenic or whether these amebas may also contribute to the distribution of L. pneumophila remains to be elucidated.

Acknowledgments

We thank Elke Radam, Sangeeta Banerji, and Markus Broich for expert assistance.

W.S.S. was supported by the Research Fund of the Robert Koch Institute (grant FKZ 1362-524).

REFERENCES

- 1.Abu Kwaik, Y., L. Y. Gao, B. J. Stone, C. Venkataraman, and O. S. Harb. 1998. Invasion of protozoa by Legionella pneumophila and its role in bacterial ecology and pathogenesis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:3127-3133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abu Kwaik, Y. 1996. The phagosome containing Legionella pneumophila within the protozoan Hartmannella vermiformis is surrounded by rough endoplasmic reticulum. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62:2022-2028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amaral Zettler, L. A., T. A. Nerad, C. J. O'Kelly, M. T. Peglar, P. M. Gillevet, J. D. Silberman, and M. L. Sogin. 2000. A molecular reassessment of the leptomyxid amoebae. Protist 151:275-282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barbaree, J. M., B. S. Fields, J. C. Feeley, G. W. Gorman, and W. T. Martin. 1986. Isolation of protozoa from water associated with a legionellosis outbreak and demonstration of intracellular multiplication of Legionella pneumophila. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 51:422-424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barker, J., M. R. Brown, P. J. Collier, I. Farrell, and P. Gilbert. 1992. Relationship between Legionella pneumophila and Acanthamoeba polyphaga: physiological status and susceptibility to chemical inactivation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 58:2420-2425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barker, J., and M. R. Brown. 1994. Trojan horses of the microbial world: protozoa and the survival of bacterial pathogens in the environment. Microbiology 140:1253-1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berger, K. H., J. J. Merriam, and R. R. Isberg. 1994. Altered intracellular targeting properties associated with mutations in the Legionella pneumophila dotA gene. Mol. Microbiol. 14:809-822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brieland, J. K., M. McClain, L. Heath, C. Chrisp, G. Huffnagle, M. LeGendre, M. Hurley, J. Fantone, and C. Engleberg. 1996. Coinoculation with Hartmannella vermiformis enhances replicative Legionella pneumophila lung infection in a murine model of Legionnaires' disease. Infect. Immun. 64:2449-2456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brieland, J. K., J. C. Fantone, D. G. Remick, M. LeGendre, M. McClain, and N. C. Engleberg. 1997. The role of Legionella pneumophila-infected Hartmannella vermiformis as an infectious particle in a murine model of Legionnaires' disease. Infect. Immun. 65:5330-5333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cianciotto, N. P. 2001. Pathogenicity of Legionella pneumophila. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 291:331-343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cirillo, J. D., S. Falkow, and L. S. Tompkins. 1994. Growth of Legionella pneumophila in Acanthamoeba castellanii enhances invasion. Infect. Immun. 62:3254-3261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cirillo, J. D., S. Falkow, L. S. Tompkins, and L. E. Bermudez. 1997. Interaction of Mycobacterium avium with environmental amoebae enhances virulence. Infect. Immun. 65:3759-3767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cirillo, J. D., S. L. G. Cirillo, L. Yan, L. E. Bermudez, S. Falkow, and L. S. Tompkins. 1999. Intracellular growth in Acanthamoeba castellanii affects monocyte entry mechanisms and enhances virulence of Legionella pneumophila. Infect. Immun. 67:4427-4434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Edelstein, P. H. 1981. Improved semiselective medium for isolation of Legionella pneumophila from contaminated clinical and environmental specimens. J. Clin. Microbiol. 14:298-303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fields, B. S. 1996. The molecular ecology of legionellae. Trends Microbiol. 4:286-290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fliermans, C. B., W. B. Cherry, L. H. Orrison, S. J. Smith, D. L. Tison, and D. H. Pope. 1981. Ecological distribution of Legionella pneumophila. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 41:9-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fraser, D. W., T. R. Tsai, W. Orenstein, et al. 1977. Legionnaires' disease: description of an epidemic of pneumonia. N. Engl. J. Med. 297:1189-1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fritsche, T. R., D. Sobek, and R. K. Gautom. 1998. Enhancement of in vitro cytopathogenicity by Acanthamoeba spp. following acquisition of bacterial endosymbionts. FEBS Microbiol. Lett. 166:231-236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gao, L. Y., O. S. Harb, and Y. Abu Kwaik. 1997. Utilization of similar mechanisms by Legionella pneumophila to parasitize two evolutionary distinct hosts, mammalian and protozoan cells. Infect. Immun. 65:4738-4746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hägele, S., R. Köhler, H. Merkert, M. Schleicher, J. Hacker, and M. Steinert. 2000. Dictyostelium discoideum: a new host model system for intracellular pathogens of the genus Legionella. Cell. Microbiol. 2:165-171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Henke, M., and K. M. Seidel. 1986. Association between Legionella pneumophila and amoebae in water. Isr. J. Med. Sci. 22:690-695. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hilbi, H., G. Segal, and H. A. Shuman. 2001. Icm/Dot-dependent upregulation of phagocytosis by Legionella pneumophila. Mol. Microbiol. 42:603-617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Horwitz, M. A. 1984. Phagocytosis of the Legionnaires' disease bacterium (Legionella pneumophila) occurs by a novel mechanism: engulfment with a pseudopod coil. Cell 36:27-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Horwitz, M. A. 1983. Formation of a novel phagosome by the Legionnaires' disease bacterium (Legionella pneumophila) in human monocytes. J. Exp. Med. 158:1319-1331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kagan, J. C., and C. R. Roy. 2000. Legionella phagosomes intercept vesicular traffic from endoplasmic reticulum exit sites. Nat. Cell Biol. 4:945-954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kilvington, S., and J. Price. 1990. Survival of Legionella pneumophila within cysts of Acanthamoeba polyphaga following chlorine exposure. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 68:519-525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.King, C. H., B. S. Fields, E. B. Shotts, and E. H. White. 1991. Effects of cytochalasin D and methylamine on intracellular growth of Legionella pneumophila and human monocyte-like cells. Infect. Immun. 59:758-763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kingston, M., and A. Padwell. 1994. Fatal legionellosis from gardening. N. Z. Med. J. 107:111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Laube, U., and A. F. Kiderlen. 1998. Detection of parasites with DNA-binding bisbenzimide H33258 in Pneumocystis carinii- and Leishmania-containing materials. Parasitol. Res. 84:559-564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Michel, R., M. Steinert, L. Zöller, B. Hauröder, and K. Hennig. 2004. Free-living amoebae may serve as hosts for the Chlamydia-like bacterium Waddlia chondrophila isolated from aborted bovine foetus. Acta Protozool. 43:37-42. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Michel, R., K.-D. Müller, B. Hauröder, and L. Zöller. 2000. A coccoid bacterial parasite of Naegleria sp. (Schizopyrenida: Vahlkampfiidae) inhibits cyst formation of its host but not transformation to the flagellate stage. Acta Protozool. 39:199-207. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moffat, J. F., and L. S. Tompkins. 1992. A quantitative model of intracellular growth of Legionella pneumophila in Acanthamoeba castellanii. Infect. Immun. 60:296-301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Molmeret, M., D. M. Bitar, L. Han, and Y. Abu Kwaik. 2004. Cell biology of the intracellular infection by Legionella pneumophila. Microbes Infect. 6:129-139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nerad, T. A., G. Visvesvara, and P. M. Daggett. 1983. Chemically defined media for the cultivation of Naegleria: pathogenic and high temperature tolerant species. J. Protozool. 30:383-387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Newsome, A. L., T. M. Scott, R. F. Benson, and B. S. Fields. 1998. Isolation of an amoeba naturally harbouring a distinctive Legionella species. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:1688-1693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rowbotham, T. J. 1980. Preliminary report on the pathogenicity of Legionella pneumophila for freshwater and soil amoebae. J. Clin. Pathol. 33:1179-1183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rowbotham, T. J. 1986. Current views on the relationship between amoebae, legionellae and man. Isr. J. Med. Sci. 22:678-689. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Roy, C. R., K. H. Berger, and R. R. Isberg. 1998. Legionella pneumophila DotA protein is required for early phagosome trafficking decisions that occur within minutes of bacterial uptake. Mol. Microbiol. 28:663-674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Roy, C. R., and R. R. Isberg. 1997. Topology of Legionella pneumophila DotA: an inner membrane protein required for replication in macrophages. Infect. Immun. 65:571-578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ruehlemann, S. A., and G. R. Crawford. 1996. Panic in the potting shed. The association between Legionella longbeachae serogroup 1 and potting soils in Australia. Med. J. Aust. 164:36-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sadosky, A. B., L. A. Wiater, and H. A. Shuman. 1993. Identification of Legionella pneumophila genes required for growth within and killing of human macrophages. Infect. Immun. 61:5361-5373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Segal, G., and H. A. Shuman. 1999. Legionella pneumophila utilizes the same genes to multiply within Acanthamoeba castellanii and human macrophages. Infect. Immun. 67:2117-2124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Segal, G., M. Purcell, and H. A. Shuman. 1998. Host cell killing and bacterial conjugation require overlapping sets of genes within a 22-kb region of the Legionella pneumophila genome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:1669-1674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schuster, F. L., and G. S. Visvesvara. 1996. Axenic growth and drug sensitivity studies of Balamuthia mandrillaris, an agent of amebic meningoencephalitis in humans and other animals. J. Clin. Microbiol. 34:385-388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schuster, F. L., T. H. Dunnebacke, G. C. Booton, S. Yagi, C. K. Kohlmeier, C. Glaser, A. Bakardjiev, P. Azimi, M. Maddux-Gonzalez, A. J. Martínez, and G. S. Visvesvara. 2003. Environmental isolation of Balamuthia mandrillaris associated with a case of amebic encephalitis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:3175-3180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Solomon, J. M., A. Rupper, J. A. Cardelli, and R. R. Isberg. 2000. Intracellular growth of Legionella pneumophila in Dictyostelium discoideum, a system for genetic analysis of host-pathogen interactions. Infect. Immun. 68:2939-2947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Steinert, M., K. Birkness, E. White, B. Fields, and F. Quinn. 1998. Mycobacterium avium bacilli grow saprozoically in coculture with Acanthamoeba polyphaga and survive within cyst walls. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:2256-2261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Swanson, M. S., and R. R. Isberg. 1995. Association of Legionella pneumophila with the macrophage endoplasmic reticulum. Infect. Immun. 63:3609-3620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tilney, L. G., O. S. Harb, P. S. Conelly, C. G. Robinson, and C. R. Roy. 2001. How the parasitic bacterium Legionella pneumophila modifies its phagosome and transforms it into rough ER: implications for conversion of plasma membrane to the ER membrane. J. Cell Sci. 114:4637-4650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Visvesvara, G. S., A. J. Martínez, F. L. Schuster, G. J. Leitsch, S. V. Wallace, T. K. Sawyer, and M. Anderson, M. 1990. Leptomyxid ameba, a new agent of amebic meningoencephalitis in humans and other animals. J. Clin. Microbiol. 28:2750-2756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Visvesvara, G. S., F. L. Schuster, and A. J. Martínez. 1993. Balamuthia mandrillaris, N. G., N. Sp., agent of amebic meningoencephalitis in humans and other animals. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 40:504-514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vogel, J. P., H. L. Andrews, S. K. Wong, and R. R. Isberg. 1998. Conjugative transfer by the virulence system of Legionella pneumophila. Science 279:873-876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]