Abstract

In voltage-gated Na+ and K+ channels, the hydrophobicity of noncharged residues in the S4 helix has been shown to regulate the S4 movement underlying the process of voltage-sensing domain (VSD) activation. In voltage-gated proton channel Hv1, there is a bulky noncharged tryptophan residue located at the S4 transmembrane segment. This tryptophan remains entirely conserved across all Hv1 members but is not seen in other voltage-gated ion channels, indicating that the tryptophan contributes different roles in VSD activation. The conserved tryptophan of human voltage-gated proton channel Hv1 is Trp207 (W207). Here, we showed that W207 modifies human Hv1 voltage-dependent activation, and small residues replacement at position 207 strongly perturbs Hv1 channel opening and closing, and the size of the side chain instead of the hydrophobic group of W207 regulates the transition between closed and open states of the channel. We conclude that the large side chain of tryptophan controls the energy barrier during the Hv1 VSD transition.

Keywords: Hv1, voltage-gated ion channel, proton channel, voltage-sensing domain, channel activation

The voltage-gated ion channels, including Nav, Kv, Cav, and Hv1 proton channels, all contain voltage-sensing domains (VSDs) that are responsible for detecting changes in membrane potential in the cells (1, 2, 3). The VSDs of voltage-gated ion channels are made of four transmembrane segments (S1 through S4). The S4 helix contains several positively charged residues located at every third position. To respond to the changes in membrane potential, the S4 helix undergoes transmembrane movement that is mediated by these charged residues (4, 5, 6). Moreover, other noncharged residues in the S4 helix have been shown to modify the S4 movement, and the hydrophobicity of noncharged residues regulates the process of voltage-dependent activation of the channels (7, 8, 9). In the Shaker Kv channel, replacements of hydrophilic residues at position 361 (L361K and L361R) in the S4 helix profoundly shifted the G-V curve toward negative voltages, and hydrophilic replacements at this position produced faster activation kinetics (8). In the Nav1.4 channel, substitution of hydrophobic residues in the S4 helix of domains I, II, and III has been shown to regulate the voltage sensor movement and alter steady-state activation and inactivation curves (7).

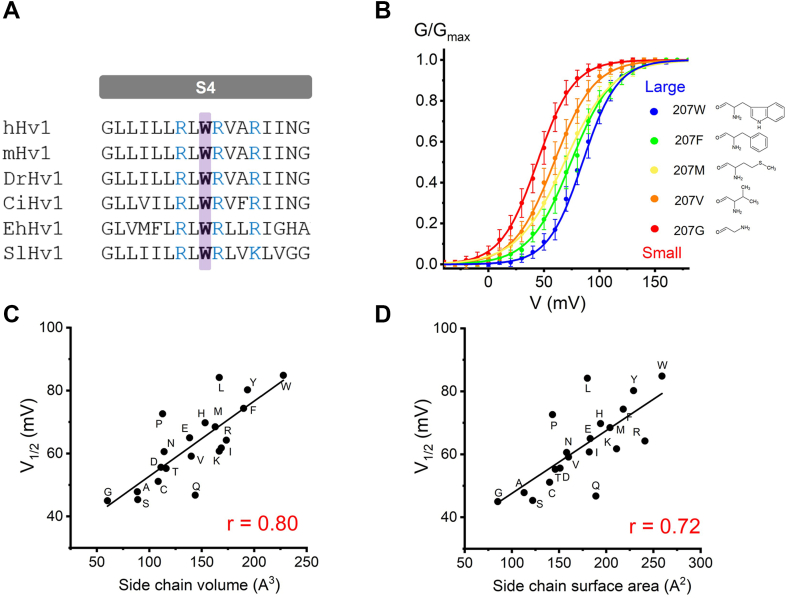

In the voltage-gated proton channel family, there is a bulky noncharged residue tryptophan located at the S4 helix, which remains highly conserved across all Hv1 channels (Fig. 1A) (10, 11). Despite progress in the functional characterization of noncharged residues in the S4 helix of Nav and Kv channels (7, 8, 9), the role of S4 noncharged residues in Hv1 channel voltage-dependent activation remains unclear. In addition, the bulky tryptophan is highly conserved in the Hv1 family (Fig. 1A) but is not seen in other voltage-gated ion channels (Fig. S1), indicating that it might contribute different roles in VSD activation.

Figure 1.

The bulky side chain at position 207 regulates Hv1 voltage-dependent activation.A, sequence alignment of the S4 transmembrane segment of Hv1 proton channels from human (hHv1), mouse (mHv1), zebrafish (DrHv1), Ciona intestinalis (CiHv1), Emiliana (EhHv1), and Suillus luteus (SlHv1). Highly conserved tryptophan (W) is highlighted in purple and bold font. W corresponds to Trp207 in hHv1. The positive S4 residues are highlighted in blue. B, G-V curves for the monomer hHv1 proton channel W207 mutations colored from blue to red when the side chain of the substituted side chain decreases, and structures of substituted residues are shown in inset. Only several W207 mutations are shown for clarity, and Table S1 summarized all W207 mutations, n = 4 to 8 for each mutation. C and D, the V1/2 values obtained from G-V curves are plotted with size of the substituted side chain at position W207, using either side chain volume (C) or side chain surface area (D). Black lines indicate fits of the data to a linear function in (C and D), and r values are presented in red in each panel.

The highly conserved tryptophan of the human Hv1 channel (hHv1) is W207. In Nav and Kv channels, the hydrophobic group of noncharged residues in S4 helix significantly influences the VSD activation (7, 8, 9). To assess whether the hydrophobic group of W207 regulates hHv1 VSD activation as well, we introduced mutations in the W207 by substituting the other 19 amino acids. In contrast to findings in other channels, we showed that the size of the side chain instead of the hydrophobic group at position W207 is essential for the Hv1 proton channel voltage-dependent activation. We further showed that small residues replacement at position 207 exhibited faster activation and deactivation kinetics, suggesting that the presence of the natively bulky tryptophan slows the gating process and controls the transition between closed and open states of the channel. We proposed a simple-state model of Hv1 VSD transition and discussed the conserved Trp regulation of Hv1 VSD activation.

Results

Effects of W207 mutations on the voltage-dependent activation of human Hv1 channel

The Hv1 channel has been shown to form dimers in which two VSD subunits are held together by a C-terminal coiled-coil domain (12, 13, 14), and deletion of the coiled-coil domain results in a monomeric form of the channel (15, 16, 17). Hv1 VSD subunits were reported to be allosterically coupled and work cooperatively (18, 19). To eliminate the influence of cooperation between subunits, we generated monomeric hHv1 by deletion of coiled-coil domain.

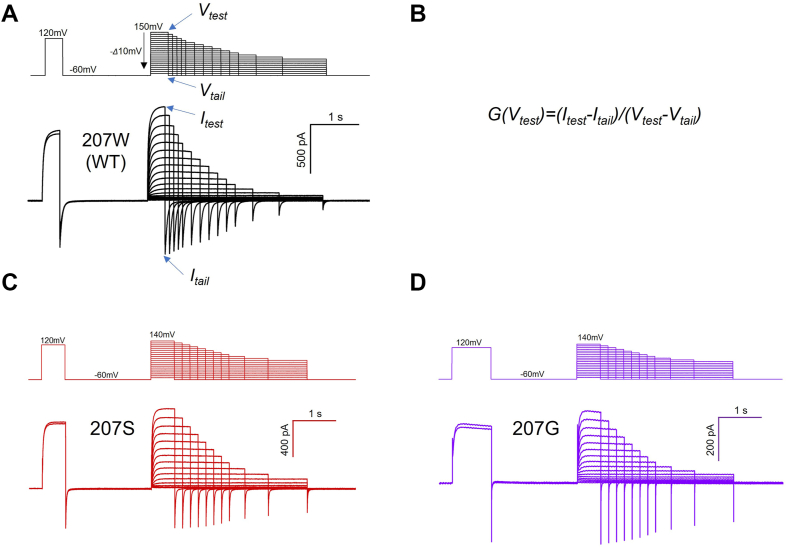

We introduced mutations at position 207 in monomeric Hv1 to investigate effects of the conserved tryptophan on the Hv1 voltage-dependent activation. The representative currents recorded in HEK293 cells expressing monomer human Hv1 (hHv1) 207W (wildtype) and 207 mutation channels are shown in Figure 2. In the recording, proton currents were measured from a holding potential of −60 mV to a first prestep and a second test-step with rest intervals at −60 mV. The proton channel conductance is determined by the equation: G(Vtest) = (Itest-Itail)/(Vtest-Vtail), where Itest is the current at Vtest, measured at the end of the depolarization step, and Itail is the current at Vtail, measured at the beginning of the repolarization step. Currents after depolarization in the prestep were used to correct for current rundown.

Figure 2.

G-V measurements from monomer Hv1 channel currents.A, representative currents were recorded in HEK293 cells expressing monomer WT (207W) Hv1 channel, pHi = pHo = 6.0. The corresponding pulse protocols are shown above the current traces. Currents were measured from a holding potential of −60 mV to a first prestep (+120 mV) and a second test-step (ranging between +150 and −50 mV in 10 mV steps) with rest intervals at −60 mV. Currents after depolarization in the prestep to +120 mV were used to correct for current rundown. For clarity, only the first and last traces elicited by the depolarization prestep are shown. The blue arrows indicate the parameters used for the channel conductance analysis. B, the channel conductance is determined by the equation: G(Vtest) = (Itest-Itail)/(Vtest-Vtail), where Itest is the current at Vtest, measured at the end of the depolarization step, and Itail is the current at Vtail, measured at the beginning of the repolarization step. C and D, representative currents were recorded in HEK293 cells expressing monomer Hv1 mutations 207S (C) and 207G (D), pHi = pHo = 6.0. The corresponding pulse protocols are shown above the current traces.

It was shown that all W207 mutations produced left-shifted G-V relationships (Fig. 1B, Table S1), suggesting that mutations at position 207 perturb the channel voltage-dependent gating and that the conserved tryptophan is essential for Hv1 VSD activation. To investigate the relationships between the Hv1 voltage dependence of activation and amino acid mutations' physicochemical properties, we conducted a linear correlation analysis. We determined the midpoint voltage (V1/2) from the fitted G-V curve to measure the voltage dependence of activation parameter. The physicochemical properties we considered for amino acids were side chain size and hydrophobicity (20, 21, 22).

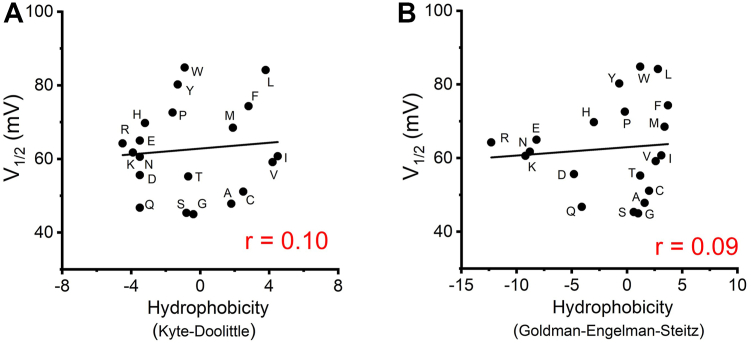

Our analysis revealed that the hydrophobicity of the side chain had no significant correlation with V1/2 (Fig. 3). However, we observed a robust linear relationship between the voltage dependence of Hv1 VSD and the side chain surface area or volume (Fig. 1, C and D). These results indicated that the size of the side chain at position 207 was closely associated with V1/2, with a bulky residue at position W207 being critical for channel function.

Figure 3.

The hydrophobic group at position 207 does not correlate with Hv1 voltage-dependent activation.A and B, the V1/2 values obtained from G-V curves are plotted as a function of hydrophobicity of the substituted side chain at position W207, using either Kyte-Doolittle hydrophobicity scale (A) or Goldman-Engelman-Steitz hydrophobicity scale (B). Black lines indicate fits of the data to a linear function, r values are presented in red in each panel.

W207 mutations have been shown to perturb ΔpH-dependent gating at lower pHo (23). Our results showed that, in monomer WT Hv1 channel, the G-V shifts between pHo = 7/pHi = 6 and pHo = 6/pHi = 6 is 38 ± 5 mV, whereas the shift is 21 ± 6 mV in W207A and 19 ± 5 mV in W207G (Fig. S3). The results are consistent with previous findings that W207 mutants compromise the ΔpH-dependent gating of the Hv1 channels (23).

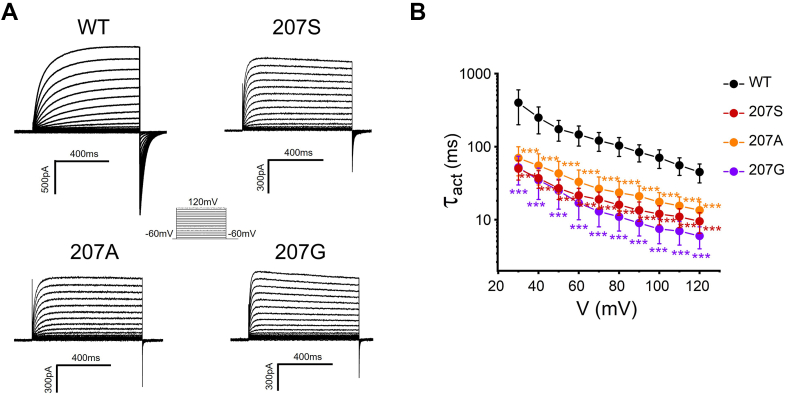

Effects of small side chain substitutions of W207 on the open and closed states of Hv1

To investigate how the large side chain of W207 affects the Hv1 voltage-dependent activation, we substituted the tryptophan with a small residue alanine at position 207 (207A). Mutation 207A exhibited significantly faster activation kinetics compared with wildtype channel (207W), suggesting that 207A mutation favors the open state of the channel (Fig. 4A). We then introduced two more small residues at position 207 (207G and 207S), and both were shown to facilitate channel opening with faster activation kinetics (Fig. 4B). These results indicated that small residue replacements at position 207 are likely to reduce an energy barrier for the channel activation and make the channel easier to open, accounting for faster activations in the mutated channels (207A, 207G, and 207S).

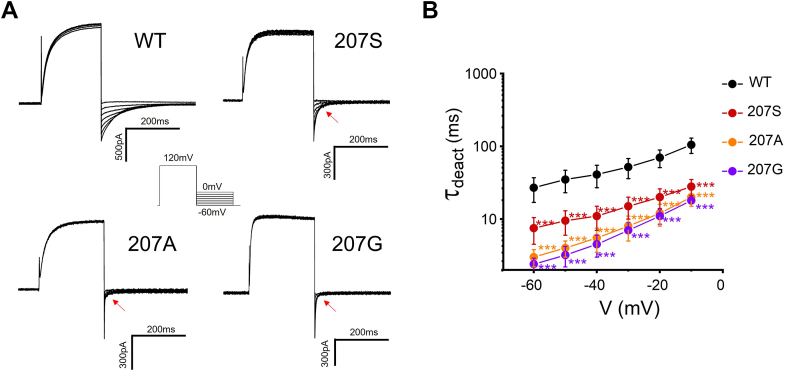

Figure 4.

Effects of small side chain substitutions of W207 on the open state of the monomer Hv1 channel.A, representative rising currents recorded from WT (207W), 207S, 207A, and 207G. Currents were measured from a holding potential of −60 mV to test potentials ranging between −60 and +120 mV in 10 mV steps. B, the channel opening time constant Ʈact in WT or W207 mutations. Ʈact was obtained from exponential fit to rising currents, n = 3 to 6 for each group. Ʈact between W207 mutation and WT were compared statistically using two-tailed test (∗∗∗p < 0.001).

The effects of a small side chain at position 207 on the closed state of the channel were further investigated. The 207A mutation showed faster deactivation kinetics (Fig. 5A). The channel closing time constant Ʈdeact values were determined, and 207A took less time to close compared with WT (Fig. 5B). Similar results have been observed in the other two small residues replacement at position 207 (207G, 207S), and both 207G and 207S altered the closing time constant Ʈdeact decreasing the values at given membrane potentials (Fig. 5B). This indicates that small residue replacements at position 207 also reduce an energy barrier for channel deactivation and facilitate channel closing.

Figure 5.

Effects of small side chain substitutions of W207 on the closed state of the channel.A, representative tail currents recorded from WT (207W), 207S, 207A, and 207G. The tail currents were elicited by a prepulse to 120 mV, in 10 mV decrements from 0 to −60 mV. Red arrows indicate faster deactivation of W207 mutations. B, the deactivation (channel closing) time constant Ʈdeact in WT or W207 mutations. Ʈdeact was obtained from exponential fit to the tail currents, n = 3 to 6 for each group. Ʈdeact between W207 mutation and WT were compared statistically using two-tailed test (∗∗∗p < 0.001).

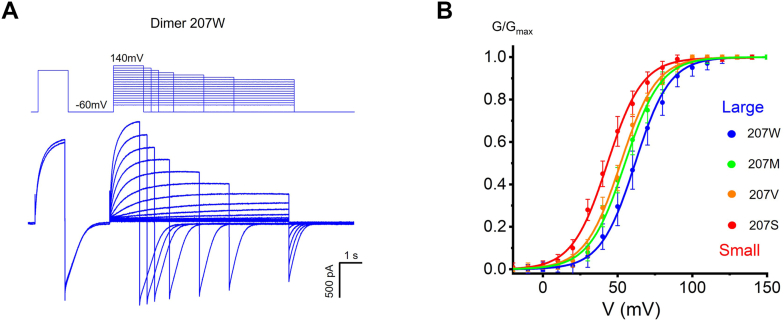

We further evaluated dimer hHv1 channels. It was shown that the bulky side chain at position 207 regulates dimer hHv1 voltage-dependent activation as well, and smaller side chain substitutions of Trp consistently produce left-shifted G-V relationships (Fig. 6). Moreover, dimer channel W207 mutations exhibited much faster activation and deactivation kinetics compared with dimer wildtype channel (Fig. 7), suggesting that small side chain substitutions of Trp favor the open and closed state of the dimer channel. In other words, small residue replacement reduces an energy barrier during the Hv1 channel voltage-dependent activation.

Figure 6.

Effects of side chain at position 207 on dimer Hv1 channel voltage-dependent activation.A, representative currents were recorded in HEK293 cells expressing dimer WT Hv1 (207W) channel, pHi = pHo = 6.0. For clarity, only the first and last traces elicited by the depolarization prestep are shown. The corresponding pulse protocols are shown above the current traces. B, G-V curves for the dimer Hv1 proton channel W207 mutations colored from blue to red when the side chain of the substituted side chain decreases, n = 4 to 7 for each group.

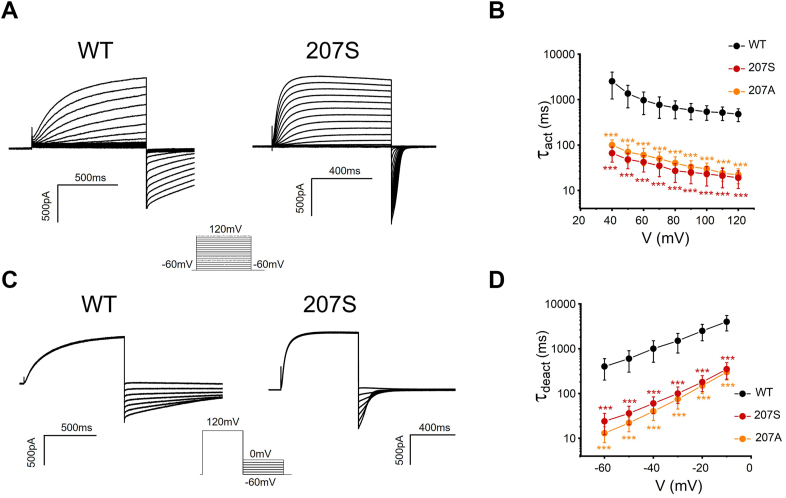

Figure 7.

Effects of small side chain substitutions of W207 on the open and closed state of the dimer Hv1 channel.A, representative rising currents recorded from dimer WT and 207S channels. Currents were measured from a holding potential of −60 mV to test potentials ranging between −60 and +120 mV in 10 mV steps. B, the channel opening time constant Ʈact in dimer Hv1 channels. Ʈact was obtained from exponential fit to rising currents. Ʈact between W207 mutation and WT were compared statistically using two-tailed test (∗∗∗p < 0.001). C, representative tail currents recorded from dimer WT and 207S channels. The tail currents were elicited by a prepulse to 120 mV, in 10 mV decrements from 0 to −60 mV. D, the deactivation (channel closing) time constant Ʈdeact in dimer Hv1 channels. Ʈdeact was obtained from exponential fit to the tail currents, n = 4 to 6 for each group. Ʈdeact between W207 mutation and WT were compared statistically using two-tailed test (∗∗∗p < 0.001).

Taken together, these results suggest that the endogenous residue tryptophan at position 207 increases the energy barrier that makes the channel neither easily open nor easily closed.

State model of W207 mutation regulation of Hv1 VSD transitions

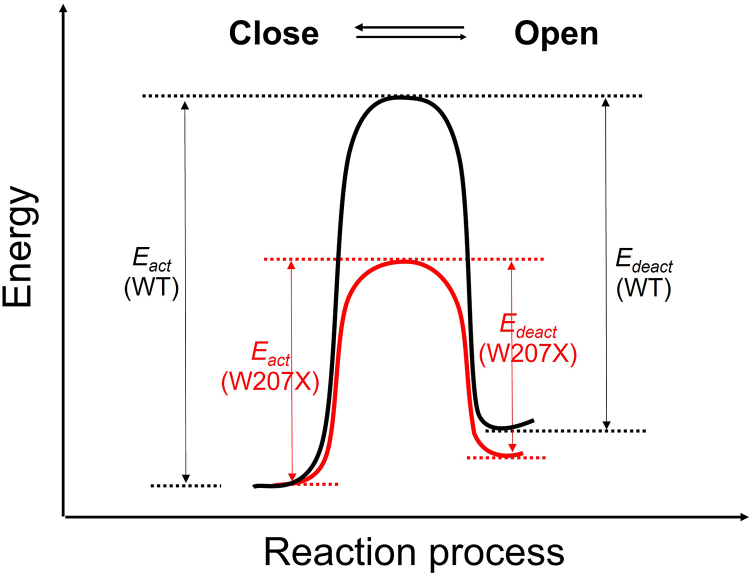

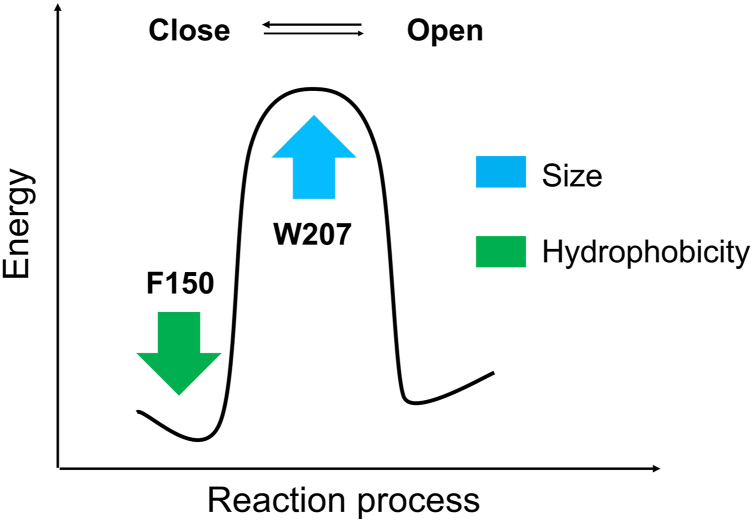

To describe the effects of small residue replacements at position 207 on the Hv1 VSD voltage-dependent activation, we proposed a simple-state model of Hv1 VSD transitions. In the model, the small residue replacements (W207X) decreased the energy barrier underlying the transition between closed and open states of the channel (Fig. 8).

Figure 8.

State model of W207 mutation regulation of Hv1 VSD transitions. The black lines represent the voltage-dependent activation for bulky side chain Trp (W) at position 207 (i.e., wildtype Hv1 channel), and red lines are changes mediated by the small side chain (X) substitutions at position 207 (W207X). The reduced energy barrier caused by W207X is satisfied by decreased activation kinetic Eact(W207X) and decreased deactivation kinetic Edeact(W207X).

The effects of W207X mutations on the closed state were satisfied by decreasing the relative depth of the energy well for the “Close” state and decreasing the energy barrier for the Close - > Open transition to allow for the faster deactivation (Figs. 5A and 8). W207X mutations’ influences on the open state could also be satisfied by decreasing the relative depth of the energy well for the “Open” state, which is achieved by the reduced energy barrier for the Open - > Close transition to interpret the faster activation kinetics (Figs. 4A and 8). A smaller ΔG0 (which is a free energy difference between the closed and open states of the activation, Table S1) for W207X was consistent with decreased activation Eact(W207X) (Fig. 4B) and reduced deactivation kinetics Edeact(W207X) (Fig. 5B).

Discussion

In the Hv1 family, there is a bulky residue tryptophan located at the S4 segment, which remains entirely conserved across all Hv1 members. This highly conserved Trp has been shown to play important roles in regulating dimer coupling and pH gradient-dependent gating (18, 23, 24). Here, we showed that the Trp strongly modifies the process of Hv1 voltage-dependent activation. The large side chain of the Trp controls the transition between closed and open states of the Hv1 channel and regulates the energy barrier during the Hv1 VSD transition.

To determine the effects of Trp on Hv1 VSD voltage-dependent activation, we introduced other 19 residues at position 207 in monomer hHv1 channel. We determined the G-V curves of W207 mutations and analyzed the effects of physicochemical properties of W207 mutations on the voltage-dependent activation. In contrast to the findings that the hydrophobicity of noncharged residues in the S4 helix of Nav and Kv channels play roles in regulation of VSD activation (7, 8), there were no significant correlations between the hydrophobicity of side chain and the V1/2 in Hv1. However, replacement of smaller residues at position 207 consistently shifts the G-V curve toward more negative voltages, indicating that large size of side chain at position 207 is crucial for the Hv1 channel voltage-dependent activation. Additionally, we notice that some amino acids containing rigid rings (e.g., 207P, 207W, 207F, and 207Y) generate relatively higher V1/2 (Table S1). Although the leucine (L), which does not have rigid rings, also generates a greater V1/2, we cannot exclude the possible contributions of rigid rings to the channel activation, which might increase the energy cost.

We replaced the tryptophan (W) with the three smallest residues (A, S, G) to determine how the largest residue (W) at position 207 affects hHv1 VSD activation, and all small residues exhibited faster activation and deactivation kinetics, indicating that small residues replacement facilitate channel opening and closing. These results suggest that the endogenous residue tryptophan increases the energy barrier that makes the channel neither easily open nor easily closed. We observed that the whole cell currents carried by W207 mutations are less than wildtype monomer channel (Fig. 4). We considered an explanation that W207-mutated channel might produce either relatively smaller single channel conductance and/or lower expression of the cell membrane that overcomes the advantage of open probability to influence the whole cell current amplitude.

Hv1 is mainly expressed in nonexcitable cells such as epithelial cells, sperm cells, and white blood cells, in which Hv1 is implicated in pH regulation in airway epithelium and sperm cells and reactive oxygen species production in phagocytes (2, 3). The pH is determined by the H+ concentration, and an alteration of H+ concentration causes abnormal local pH that influences cell physiology. Overactivity of the Hv1 channel can result in low concentration of intracellular H+ and lead to cellular acid–base imbalances (2). The presence of large tryptophan in the Hv1 channel can prevent frequent transitions between closed and open states of the channel and protect against the overactivity of Hv1, and this function might manipulate Hv1 activity to coordinate the regulation of pH homeostasis in white blood cells, sperm cells, epithelial cells, and other cells where Hv1 expressed and maintain normal physiological functions in these cells.

The Hv1 channel function is regulated by pH gradient (ΔpH). It was reported that the G-V of Hv1 channel shifts around 40 mV/unit change in ΔpH, regardless of whether pHo or pHi is changed (25). W207 mutations have been shown to influence ΔpH-dependent gating at lower pHo, supporting the existence of distinct internal and external pH sensors (23). In the present study, W207 mutations exhibited less G-V shifts compared with wildtype channel in the same pH gradient, which is consistent with previous findings that W207 mutations compromise the ΔpH-dependent gating of the Hv1 channels (23). W207 mutations might generate allosterically conformational effects on the pH sensors to perturb the ΔpH-dependent gating of the channel.

The Hv1 channel has been shown to form dimers in which two VSD subunits are held together by a C-terminal coiled-coil domain (12, 13, 14). Studies have found that the two Hv1 subunits gate cooperatively, and it was shown that the opening of one subunit substantially increases the probability of the other subunit to open (19). Okuda et al. discovered a molecular mechanism by which two Hv1 subunits cooperate with each other (18). It was shown that the two Hv1 S4 helices within the dimer directly cooperate via a π-stacking interaction between Trp residues at the middle of each segment. To delineate the interaction between two Hv1 subunits, Okuda et al. performed a scanning mutagenesis in the S4 transmembrane helices of the Hv1 channel and showed that the aromatic-aromatic interaction mediated by two Trps plays a role in regulation of the dimer’s cooperativity. Okuda et al. showed that replacement of Trp in some positions of the S4 helix (e.g., 250W, 253W, 257W in Ciona Hv1) produced stronger effects for deactivation. The analysis of interaction energies for the positions 250, 253, and 257 in the S4 helix showed strong interaction of the two Trp residues in two subunits during the deactivation phase, suggesting that positions 250, 253, and 257 play crucial roles in regulating two Hv1 subunits interaction during gating cooperativity (18).

In the present study, we focus on the role of Trp in regulating Hv1 voltage sensor transition in each VSD subunit. Our results showed that Trp modifies the process of Hv1 voltage-dependent activation (i.e., a process by which the channel transitions between its closed and open states). We performed mutagenesis at position Trp207 in human Hv1 channel and found that replacement of small residues at position 207 exhibited faster gating kinetics, in other words, the endogenous Trp at the position 207 presented much slower deactivation and activation compared to the ones of small residues substitution, indicating that the Trp at position 207 plays a role in the regulation of Hv1 channel gating. To date, although several models of voltage sensing, including transporter model, helical screw model, and paddle model, were proposed to describe the movement of VSD S4 helix in voltage-gated Na+, Ca+, and K+ channels (26), so far, the way of the movement of S4 helix in Hv1 VSD subunit is not yet clear. Our results indicated that the bulky side chain of Trp mediates the movement of Hv1 VSD S4 helix that might undergo rotating and translate along its axis to move across the transmembrane electric field, similar with helical screw model in other ion channels. The small side chain at position 207 reduces the barrier during the process of Hv1 S4 helix rotation and translation in Hv1 VSD, accounting for fast activation and deactivation of the channel when W207 mutated to small residues.

We previously found that a highly conserved residue F150 is important for the hHv1 channel function and that the hydrophobic group of F150 stabilizes the resting Hv1 VSD (27). Here, we showed that another highly conserved residue W207 regulates the energy barrier during the Hv1 VSD transition. In contrast to the contributions of hydrophobicity of F150 to the channel function, the large size of side chain of W207 is essential for the Hv1 VSD activation, in which it controls the transition between closed and open states of the channel (Fig. 9). The Hv1 proton channel is known to play a role in reactive oxygen species generation and the regulation of pH homeostasis (25, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32). Exploring how the conserved residues including W207 regulates the process of Hv1 voltage-dependent activation will provide insights into the development of targeted reagents modulating Hv1 activity (33).

Figure 9.

Contributions of conserved residues to the Hv1 VSD energy landscape. Previous study showed that increasing the hydrophobicity of residue at position F150 (green arrow) stabilizes the resting state relative to active state. Present study indicates that increasing the size of the side chain at position W207 (blue arrow) is essential to control Hv1 VSD energy barrier. VSD, voltage-sensing domain.

Experimental procedures

Mutagenesis

Recombinant human Hv1 channels were subcloned in the pNICE vector. Monomeric hHv1 was achieved by introducing a stop codon at position 224 (S224stop), which deletes coiled-coil domains essential for Hv1 dimer formation (15). Single-point mutations were introduced with standard PCR techniques (34, 35). PCR primers were purchased from IDT DNA Technologies. Custom-designed primers for mutagenesis of hHv1 constructs were included in Table S2. Hv1 mutation was introduced to the template plasmid using primers in a PCR protocol. The PCR cycles were initiated at 98 °C for 1.5 min, followed by 25 amplification cycles. Each amplification cycle consisted of 98 °C (20 s), 60 °C (30 s), and 72 °C (5 min). The cycles were finished with an extension step at 72 °C for 15 min, followed by 4 °C for 30 min. After template plasmid was removed by DpnI (NEB, R0176S), the Stbl2 competent cells (Invitrogen,10268019) were transformed with the PCR product. Plasmids were isolated from Stbl2 cells with resulting colonies using QIAprep Spin Miniprep Kit (Qiagen, 27106). Mutation confirmed by the DNA sequencing was used for subsequent transfection.

Cell culture and Hv1 transfection

HEK293 cells (Sigma-Aldrich) were reseeded on coverslips containing Dulbecco modified Eagle’s medium supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin at 37 °C under 5% CO2. Cells were transiently transfected with human Hv1 and GFP cDNA plasmids after growth to ∼70% confluence. The HEK-293 cells were transiently transfected with 2 μg of the cDNA encoding Hv1 construct and 0.25 μg of a plasmid encoding GFP using Lipofectamine 3000 reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The mixture was then added to the culture dish, and the cells were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h before the electrophysiology studies were conducted. A coverslip with HEK293 cells was placed in a recording chamber containing bath solution on the stage of a fluorescence microscope (Olympus), and the transfected cells detected by the fluorescent signal emitted from GFP were applied for electrophysiological measurements. Patch clamp experiments were conducted 1∼3 days after transfection.

Electrophysiological measurements and analysis

Hv1 proton currents were recorded with whole-cell configuration using an Axopatch 200B amplifier controlled by pClamp11 software through an Axon Digidata 1550B system (Molecular Devices) (36). The bath solution contained 75 mM N-methyl-D-glucamine, 110 mM 2-(N-morpholino)-ethanesulphonic acid, 80 mM glucose, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM CaCl2, adjusted to pHo 6.0 with methanesulfonic acid. The pipette solution contained 75 mM N-methyl-D-glucamine, 110 mM 2-(N-morpholino)-ethanesulphonic acid, 80 mM glucose, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EGTA, adjusted to pHi 6.0 with methanesulfonic acid. We performed recording in constant perfusion of the bath compartment to increase buffer turnover by convection, and the solution (pHi = pHo = 6.0) is used to minimize the effects of H+ accumulation on the local H+ concentration during the recording, and the Vrev of Hv1 channels are closed to theoretical equilibrium Nernst potential (0 mV) for reversal potential (Vrev) (Fig. S2 and Table S1). All measurements were performed at 22 ± 3 °C. Pipettes had 2 to 5 MΩ access resistance. Current traces were filtered at 1 kHz and analyzed with Clampfit11 (Molecular Devices) and Origin 2019 (OriginLab).

In the recording, proton currents were measured from a holding potential of −60 mV to a first prestep and a second test-step with rest intervals at −60 mV (37, 38). The proton channel conductance is determined by the equation: G(Vtest) = (Itest-Itail)/(Vtest-Vtail), where Itest is the current at Vtest, measured at the end of the depolarization step, and Itail is the current at Vtail, measured at the beginning of the repolarization step. Currents after depolarization in the prestep were used to correct for current rundown. Steady-state activation G-V curves were fitted by the Boltzmann equation (39): G/Gmax = 1/(1 + exp(V1/2-V)/k), where G/Gmax is the relative conductance normalized by the maximal conductance, V1/2 is the potential of half activation, V is the test pulse, and k is the slope factor. k is equal to RT/ɀF, where ɀ is the equivalent charge, R is the gas constant, F is Faraday’s constant, and T is temperature in Kelvin. Reported V1/2 and k values derived from the Boltzmann fits to data from multiple cells were used to assess the free energy difference at 0 mV (ΔG0) between the closed and open states of the activation, the ΔG0 was calculated according to the following: ΔG0 = ɀFV1/2. The channel opening time constant Ʈact and closing time constant Ʈdeact values were calculated by fitting current traces with the single-exponential equation according to the following: I(t) = I0 + A(1-exp(-t/Ʈ)), where I(t) represents the current at time point t, I0 is the initial current amplitude, Ʈ is the time constant.

Data and statistical analysis

All data were presented as mean ± standard deviation. Significance between means was determined by Student’s t test. Electrophysiological parameters (V1/2, Ʈdeact, Ʈdeact, etc) were determined from each individual cell and used for comparison with two-tailed t test. p < 0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference and were indicated by ∗. p < 0.01 and p < 0.001 are signified by ∗∗ and ∗∗∗, respectively.

Data availability

All data are contained within the article.

Supporting information

This article contains supporting information.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

Acknowledgments

Author contributions

L. Z. and L. H. writing–original draft; L. Z., X. W., X. C., and L. H. writing–review & editing; L. Z. data curation; L. Z. and L. H. formal analysis; L. Z., X. W., X. C., and K. R. investigation; L. H. conceptualization; L. H. resources; L. H. supervision; L. H. project administration; L. H. funding acquisition.

Funding and additional information

This work was supported in part by the National Institute of Health Grant R01GM139991 (L. H.), American Heart Association Grant 19CDA34630041 (L. H.), and University of Illinois Chicago Center for Clinical and Translational Science Grant UL1TR002003 (L. H.). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Reviewed by members of the JBC Editorial Board. Edited by Mike Shipston

Supporting information

References

- 1.Okamura Y. Biodiversity of voltage sensor domain proteins. Pflugers Arch. 2007;454:361–371. doi: 10.1007/s00424-007-0222-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Okamura Y., Okochi Y. Molecular mechanisms of coupling to voltage sensors in voltage-evoked cellular signals. Proc. Jpn. Acad. Ser. B Phys. Biol. Sci. 2019;95:111–135. doi: 10.2183/pjab.95.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Swartz K.J. Sensing voltage across lipid membranes. Nature. 2008;456:891–897. doi: 10.1038/nature07620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jiang Y., Ruta V., Chen J., Lee A., MacKinnon R. The principle of gating charge movement in a voltage-dependent K+ channel. Nature. 2003;423:42–48. doi: 10.1038/nature01581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chanda B., Asamoah O.K., Blunck R., Roux B., Bezanilla F. Gating charge displacement in voltage-gated ion channels involves limited transmembrane movement. Nature. 2005;436:852–856. doi: 10.1038/nature03888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cha A., Snyder G.E., Selvin P.R., Bezanilla F. Atomic scale movement of the voltage-sensing region in a potassium channel measured via spectroscopy. Nature. 1999;402:809–813. doi: 10.1038/45552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bendahhou S., O'Reilly A.O., Duclohier H. Role of hydrophobic residues in the voltage sensors of the voltage-gated sodium channel. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2007;1768:1440–1447. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang Y.C., Own C.J., Kuo C.C. A hydrophobic element secures S4 voltage sensor in position in resting Shaker K+ channels. J. Physiol. 2007;582:1059–1072. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.131490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McCormack K., Tanouye M.A., Iverson L.E., Lin J.W., Ramaswami M., McCormack T., et al. A role for hydrophobic residues in the voltage-dependent gating of Shaker K+ channels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1991;88:2931–2935. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.7.2931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ramsey I.S., Moran M.M., Chong J.A., Clapham D.E. A voltage-gated proton-selective channel lacking the pore domain. Nature. 2006;440:1213–1216. doi: 10.1038/nature04700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sasaki M., Takagi M., Okamura Y. A voltage sensor-domain protein is a voltage-gated proton channel. Science. 2006;312:589–592. doi: 10.1126/science.1122352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tombola F., Ulbrich M.H., Isacoff E.Y. The voltage-gated proton channel Hv1 has two pores, each controlled by one voltage sensor. Neuron. 2008;58:546–556. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.03.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee S.Y., Letts J.A., Mackinnon R. Dimeric subunit stoichiometry of the human voltage-dependent proton channel Hv1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2008;105:7692–7695. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803277105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koch H.P., Kurokawa T., Okochi Y., Sasaki M., Okamura Y., Larsson H.P. Multimeric nature of voltage-gated proton channels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2008;105:9111–9116. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801553105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fujiwara Y., Kurokawa T., Takeshita K., Kobayashi M., Okochi Y., Nakagawa A., et al. The cytoplasmic coiled-coil mediates cooperative gating temperature sensitivity in the voltage-gated H(+) channel Hv1. Nat. Commun. 2012;3:816. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sakata S., Kurokawa T., Norholm M.H., Takagi M., Okochi Y., von Heijne G., et al. Functionality of the voltage-gated proton channel truncated in S4. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2010;107:2313–2318. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911868107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carmona E.M., Larsson H.P., Neely A., Alvarez O., Latorre R., Gonzalez C. Gating charge displacement in a monomeric voltage-gated proton (Hv1) channel. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2018;115:9240–9245. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1809705115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Okuda H., Yonezawa Y., Takano Y., Okamura Y., Fujiwara Y. Direct interaction between the voltage sensors produces cooperative Sustained deactivation in voltage-gated H+ channel dimers. J. Biol. Chem. 2016;291:5935–5947. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.666834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tombola F., Ulbrich M.H., Kohout S.C., Isacoff E.Y. The opening of the two pores of the Hv1 voltage-gated proton channel is tuned by cooperativity. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2010;17:44–50. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zamyatnin A.A. Protein volume in solution. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 1972;24:107–123. doi: 10.1016/0079-6107(72)90005-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kyte J., Doolittle R.F. A simple method for displaying the hydropathic character of a protein. J. Mol. Biol. 1982;157:105–132. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(82)90515-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Engelman D.M., Steitz T.A., Goldman A. Identifying nonpolar transbilayer helices in amino acid sequences of membrane proteins. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biophys. Chem. 1986;15:321–353. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bb.15.060186.001541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cherny V.V., Morgan D., Musset B., Chaves G., Smith S.M., DeCoursey T.E. Tryptophan 207 is crucial to the unique properties of the human voltage-gated proton channel, hHv1. J. Gen. Physiol. 2015;146:343–356. doi: 10.1085/jgp.201511456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.De La Rosa V., Ramsey I.S. Gating currents in the Hv1 proton channel. Biophys. J. 2018;114:2844–2854. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2018.04.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.DeCoursey T.E. Voltage-gated proton channels: molecular biology, physiology, and pathophysiology of the H(V) family. Physiol. Rev. 2013;93:599–652. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00011.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tombola F., Pathak M.M., Isacoff E.Y. How does voltage open an ion channel? Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2006;22:23–52. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.21.020404.145837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu X., Zhang L., Hong L. The role of Phe150 in human voltage-gated proton channel. iScience. 2022;25:105420. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2022.105420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu X., Li Y., Maienschein-Cline M., Feferman L., Wu L., Hong L. RNA-seq Analyses reveal roles of the HVCN1 proton channel in Cardiac pH homeostasis. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022;10 doi: 10.3389/fcell.2022.860502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ma J., Gao X., Li Y., DeCoursey T.E., Shull G.E., Wang H.S. The HVCN1 voltage-gated proton channel contributes to pH regulation in canine ventricular myocytes. J. Physiol. 2022;600:2089–2103. doi: 10.1113/JP282126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.El Chemaly A., Nunes P., Jimaja W., Castelbou C., Demaurex N. Hv1 proton channels differentially regulate the pH of neutrophil and macrophage phagosomes by sustaining the production of phagosomal ROS that inhibit the delivery of vacuolar ATPases. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2014;95:827–839. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0513251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morgan D., Capasso M., Musset B., Cherny V.V., Rios E., Dyer M.J., et al. Voltage-gated proton channels maintain pH in human neutrophils during phagocytosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2009;106:18022–18027. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905565106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wu X., Singla S., Liu J.J., Hong L. The role of macrophage ion channels in the progression of atherosclerosis. Front. Immunol. 2023;14 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1225178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pupo A., Gonzalez Leon C. In pursuit of an inhibitory drug for the proton channel. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2014;111:9673–9674. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1408808111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wu X., Li Y., Hong L. Effects of Mexiletine on a Race-specific mutation in Nav1.5 associated with Long QT Syndrome. Front. Physiol. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fphys.2022.904664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hong L., Zhang M., Sridhar A., Darbar D. Pathogenic mutations perturb calmodulin regulation of Nav1.8 channel. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2020;533:168–174. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2020.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhao C., Hong L., Riahi S., Lim V.T., Tobias D.J., Tombola F. A novel Hv1 inhibitor reveals a new mechanism of inhibition of a voltage-sensing domain. J. Gen. Physiol. 2021;153 doi: 10.1085/jgp.202012833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhao C., Tombola F. Voltage-gated proton channels from fungi highlight role of peripheral regions in channel activation. Commun. Biol. 2021;4:261. doi: 10.1038/s42003-021-01792-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhao C., Webster P.D., De Angeli A., Tombola F. Mechanically-primed voltage-gated proton channels from angiosperm plants. Nat. Commun. 2023;14:7515. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-43280-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhao C., Hong L., Galpin J.D., Riahi S., Lim V.T., Webster P.D., et al. HIFs: new arginine mimic inhibitors of the Hv1 channel with improved VSD-ligand interactions. J. Gen. Physiol. 2021;153 doi: 10.1085/jgp.202012832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data are contained within the article.