Abstract

Tropic acid was synthesized in a good yield and with high enantioselectivity (81% ee) under non-biphasic conditions via the novel hydrolytic dynamic kinetic resolution of racemic 3-phenyl-2-oxetanone (tropic acid β-lactone) in the presence of a chiral quaternary ammonium phase-transfer catalyst and strongly basic anion exchange resin as the hydroxide ion donor.

The hydrolytic dynamic kinetic resolution of racemic 3-phenyl-2-oxetanone using a chiral PTC and water-free basic anion exchange resin as the hydroxide ion donor was achieved.

Solanaceous plant species, such as Atropa belladonna L., Datura stramonium L., and Hyoscyamus niger L. can produce hyoscyamine ((S)-1), a potent parasympathetic blocker belonging to the tropane alkaloid family. The achiral tropine (2) and chiral (S)-tropic acid ((S)-3) are the two major subcomponents of (S)-1. Although (S)-1 exhibits a potent activity, its enantiomer, (R)-1 is significantly less active. Consequently, the chirality of the tropic acid moiety plays a critical role in the parasympathetic blocking activity (Scheme 1).1,2

Scheme 1. Fast racemization of (S)-1 followed by slow hydrolysis to give (RS)-3 under basic methanolysis.

The saponification of (S)-1 is the most straightforward method to synthesize the enantioenriched (S)-3. However, the chiral center of (S)-1 is easily racemized under alkaline conditions to yield atropine ((RS)-1) with equimolar amounts of (S)-1 and (R)-1. Thereafter, hydrolysis proceeds slowly to yield the racemic tropic acid ((RS)-3) (Scheme 1).3 This process was proposed by Kitagawa et al. after carefully monitoring the reaction by 1H-NMR.4

Hanefeld et al. reported the excellent enzymatic kinetic resolution (KR) of racemic tropic acid esters.5 Initially, they attempted the enzymatic hydrolysis of the racemic 3-phenyl-2-oxetanone ((RS)-4), a tropic acid β-lactone. However, (RS)-4 was too labile in a phosphate buffer (pH 7), and their preliminary investigation resulted in a complete hydrolysis to racemic 3, even in the absence of an enzyme. Therefore, (RS)-4 was converted to more stable esters, such as butyl tropanoate ((RS)-5). Some studies reported an enzymatic KR with good selectivity using Candida antarctica lipase B on (RS)-5 (Scheme 2).6,7 The hydrolytic enzymatic KR of the tropic acid esters were successfully done, however, the chemical yields of the respective enantiomers do not exceed the barrier of theoretical yield of 50%. We planned to develop a new method to produce chiral tropic acid by hydrolytic dynamic kinetic resolution of racemic tropic acid esters by organocatalysis.

Scheme 2. Enzymatic hydrolytic kinetic resolution of the esters of (RS)-3.

Several studies investigated the application of quaternary ammonium salts as positively charged species in enantioselective ion-pair catalysis.8,9

In 2018, Tokunaga et al. reported the asymmetric hydrolysis of a racemic amino acid ester (6) with a high enantioselectivity using a chiral phase-transfer catalyst (PTC) 7 (Scheme 3).10,11 The reaction relied on an equilibrium-based racemization process between the two ester enantiomers prior to hydrolysis which enabled the hydrolytic dynamic kinetic resolution (DKR) of amino acid esters using a chiral phase-transfer catalyst under basic conditions. Inspired by this method, we attempted to obtain (S)-3via a PTC-mediated DKR hydrolysis.

Scheme 3. Enantioselective hydrolysis of racemic esters by chiral phase-transfer catalysts (PTC).

As a proof-of-concept study, the asymmetric hydrolysis of each of butyl tropanoate (RS)-5, methyl tropanoate (RS)-9, and 1,1,1,3,3,3-hexafluoro-2-propyl tropanoate (RS)-10 was attempted under alkaline biphasic conditions similar to those reported by Tokunaga et al. using a chiral PTC (11) derived from cinchona alkaloids (Scheme 3a–c); however, the optical purity of the obtained tropic acid was not as expected which can be attributed to the conformational fluidity of these esters. It was thus hypothesized that using the sterically and conformationally rigid (RS)-4 might improve the DKR reaction.

In 1985, Vederas et al. reported the nucleophilic ring-opening reaction of serine-derived chiral β-lactones with various nucleophiles.12 They investigated the basic methanolysis of chiral β-lactone to produce the corresponding methyl ester. Although the original chirality on the β-lactone was completely lost, this result demonstrated that fast racemization took place prior to methanolysis. This study led us to attempt the hydrolytic DKR of racemic β-lactones.

To achieve an enantioselective DKR hydrolysis, an equilibrium must exist between the enantiomers of 4. To confirm the racemization equilibrium prior to lactone hydrolysis, the hydrolysis of (RS)-4 in a KOD solution was performed and the 1H-NMR analysis results revealed that 24% of the hydrolyzed product was deuterated at the α-carbon of the carboxyl group. In contrast, upon exposure of (RS)-3 to the KOD solution, 3 was recovered without any deuteration and with an optical purity of 0% ee. These results demonstrated that the DKR of 4 can be achieved via a chiral PTC-catalyzed hydrolysis (Scheme 4).

Scheme 4. Confirmation of the racemic equilibrium between both enantiomers of (RS)-3 and (RS)-4.

As predicted, the asymmetric hydrolysis of (RS)-4 using 11 afforded (S)-3 in a good yield and with improved enantioselectivity (52% ee, Scheme 3d). Although the reaction of acyclic esters was quite sluggish, the hydrolysis of lactone (RS)-4 was completed within 10 min. Based on these results, we decided to further investigate the hydrolysis of DKR using (RS)-4 as a promising substrate.

Initially, the effect of the solvent was investigated, and the results revealed that the optical purity of 3 was low in hexane, toluene, diethyl ether, THF, and CCl4 (Table 1, entries 1–5). Notably, a relatively high enantioselectivity was obtained in each of CHCl3 and CH2Cl2 (entries 6, 7). In these two halogenated solvents, the physicochemical properties, such as the dipole moment (μ), dielectric constant (εr), and acceptor number (AN), were significantly greater than those in the other solvents, thus indicating that solvents with a larger AN solvate the hydroxide ion to form a favored derivative of the lactone carbonyl.13 On the other hand, the low deuteration rate indicated that hydrolysis occurred before attaining a sufficient enolate equilibrium, which is necessary to improve enantioselective DKR.

Table 1. Solvent effects and physical properties of the solvents.

| ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Solvent | μ a | ε r b | DNc | ANd | (S)-3 : (S)-3d | Yield (%) | % eee |

| 1 | Hexane | 0.0 | 1.9 | 0.00 | 0.0 | 36 : 64 | 99 | 0 |

| 2 | Toluene | 1.0 | 2.4 | <0.01 | 8.2f | 60 : 40 | 96 | 8 |

| 3 | (C2H5)2O | 3.8 | 4.2 | 0.49 | 3.9 | 52 : 48 | 96 | 2 |

| 4 | THF | 5.8 | 7.6 | 0.52 | 8.0 | 14 : 86 | 98 | 18 |

| 5 | CCl4 | 0.0 | 2.2 | 0.00 | 8.6 | 59 : 41 | 97 | 0 |

| 6 | CHCl3 | 3.8 | 4.8 | 0.10 | 23.1 | 74 : 26 | 93 | 48 |

| 7 | CH2Cl2 | 5.2 | 8.9 | 0.03 | 20.4 | 56 : 44 | 98 | 52 |

Dipole moments (μ, 10–30 Cm).

Dielectric constants (εr).

Donor numbers (DN).

Acceptor numbers (AN).

Optical purity was determined by Chiral HPLC (Daicel IC, t-butyl methyl ether : TFA = 100 : 0.1).

The value of benzene is shown.

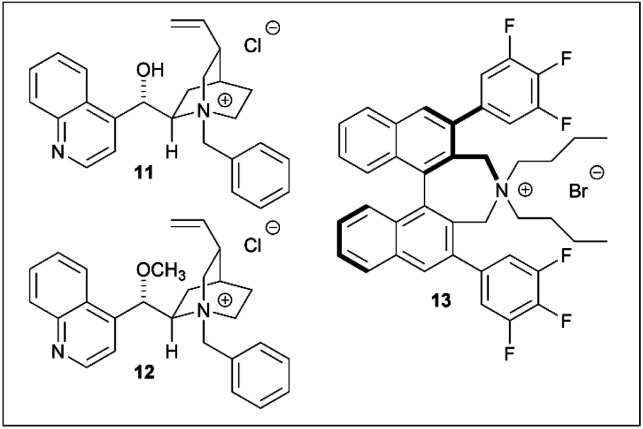

The contribution of the hydroxyl group on the catalyst was then investigated. Since enantioselectivity was completely lost in the presence of the O-methyl and Maruoka catalysts (12 (ref. 14) and 13 (ref. 15) respectively) (Table 2, entries 4–6), it was thus concluded that the free hydroxyl group on the catalyst was essential for enantioselectivity.11

Table 2. Effect of the free hydroxyl group on the catalyst.

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | PTC (10 mol%) | Base | Solvent | Time | Yield (%) | % ee |

| 1 | 11 | 1 M KOH | CHCl3 | 10 min | 77 | 48 (S) |

| 2 | 11 | 1 M KOH | CH2Cl2 | 10 min | 76 | 52 (S) |

| 3 | 11 | 1 M NaOH | CH2Cl2 | 10 min | 88 | 54 (S) |

| 4 | 12 | 1 M NaOH | CH2Cl2 | 24 h | 74 | 0 |

| 5 | 13 | 1 M KOH | CHCl3 | 24 h | 66 | 0 |

| 6 | 13 | 1 M KOH | Toluene | 10 min | 45 | 0 |

| ||||||

However, we were concerned that the exposure of 4 to excess hydroxide ions dispersed in the organic phase can result in a non-specific hydrolysis and poor enantioselectivity due to the high instability of the β-lactone under aqueous alkaline conditions. Therefore, we employed a strongly basic anion-exchange resin (R4N·OH−, 8% cross-linked) as the hydroxide ion (OH−) donor under water-free conditions instead of the basic biphasic conditions relying an aqueous hydroxide solution. The hydrolysis was thus performed using R4N·OH− in CH2Cl2 with catalyst 11. The asymmetric yield dramatically improved to 72% ee while the yield was acceptable (Table 3, entry 5). Notably, the asymmetric hydrolysis of both (S)- and (R)-4 yielded (S)-3 predominantly (entries 6, 7).

Table 3. Hydrolysis of racemic and chiral β-lactones.

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | β-lactone | 11 (mol%) | Temp. (°C) | Yield (%) | % ee |

| 1 | (RS)-4 | 10 | −10 | 28 | 80 (S) |

| 2 | (RS)-4 | 10 | −20 | 18 | 78 (S) |

| 3 | (RS)-4 | 20 | 0 | 90 | 74 (S) |

| 4 | (RS)-4 | 5 | 0 | 84 | 68 (S) |

| 5 | (RS)-4 | 10 | 0 | 71 | 72 (S) |

| 6 | (S)-4 | 10 | 0 | 71 | 76 (S) |

| 7 | (R)-4 | 10 | 0 | 67 | 66 (S) |

As our next task, we thought we should consider two possibilities for the reaction mechanism whether the enantioselective DKR was the result of chiral PTC catalyzed enantio-enrichment of (S)-4 through deprotonation-protonation process followed by non-enantioselective hydrolysis, or enantioselective hydrolysis of (S)-4 catalyzed by chiral PTC.

In the former case, we assumed that the major enantiomer presented in the reaction solution would be (S)-4. In order to confirm this working hypothesis, the time course HPLC analysis of the reaction solution was performed to see the time dependent change of the ratio of (S)-4 and (R)-4 (Table 4).

Table 4. Time course analyses of the ratio of β-lactone enantiomers under PTC catalyzed hydrolysis condition.

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time | Substrate | (S)-4 : (R)-4 | Substrate | (S)-4 : (R)-4 | Substrate | (S)-4 : (R)-4 |

| 0 h | (R)-4a | 0 : 100 | (S)-4a | 98 : 2 | (RS)-4 | 50 : 50 |

| 1 h | 45 : 55 | 56 : 44 | 44 : 56 | |||

| 2 h | 45 : 55 | 49 : 51 | 47 : 53 | |||

| 4 h | 45 : 55 | 46 : 54 | 46 : 54 | |||

The optical purities of (R)-4 and (S)-4 were 100% ee and 96% ee, respectively.

As the results, it turned out that the major enantiomer presented in the reaction solution was (R)-4. These results indicated that enantiodifferentiation took place during the hydrolysis process of (S)-4, rather than the enantioenrichment of (S)-4 by deprotonation–protonation prior to hydrolysis (Scheme 5).

Scheme 5. Proposed mechanism of the hydrolytic dynamic kinetic resolution of 4.

Several phase-transfer catalysts were then screened under the optimal reaction conditions (Table 5). The best result was obtained using catalyst 14, which afforded (S)-3 in an 85% yield and 81% ee. Replacing the quinoline moiety with naphthalene (entry 5) resulted in a significant decrease in the asymmetric yield. The electron deficiency of the quinoline ring may contribute to a favorable approach for hydroxyl ions, while the introduction of a trifluoromethyl group at the quinoline 2-position did not have any significant effect (entries 4, 8).16 In this hydrolysis, the contribution of the methoxy group on the quinoline moiety was minor, while the stereogenic center adjacent to the vinyl group affected the enantioselectivity.

Table 5. Screening of the hydrolysis catalysts.

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | PTC | Time (h) | Yield (%) | % ee |

| 1 | 11 | 22 | 71 | 72 (S) |

| 2 | 14 | 30 | 85 | 81 (S) |

| 3 | 15 | 27 | 74 | 78 (S) |

| 4 | 16 | 20 | 52 | 74 (S) |

| 5 | 17 | 21 | 64 | 56 (S) |

| 6 | 18 | 22 | 85 | 66 (R) |

| 7 | 19 | 30 | 86 | 64 (R) |

| 8 | 20 | 40 | 77 | 62 (R) |

| ||||

The spatial proximity of the vinyl group and the quinoline moiety in the structures of 11/14 and 18/19, provided a more favorable reaction field, thus resulting in a higher enantioselectivity. Although the enantioselectivities of 11/14 and 18/19 were not identical with respect to the stereochemistries of the products, they were treated as pseudoenantiomers.

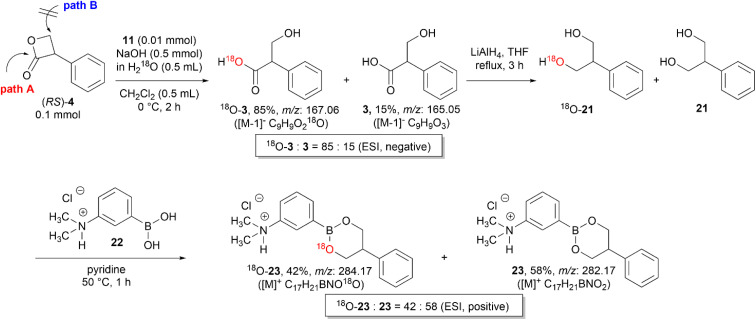

Vederas et al. investigated various nucleophiles in the ring-opening reaction of serine-derived β-lactones. The results revealed that depending on the class of the nucleophiles, the hydrolysis reaction can occur through a substitution reaction either in an addition–elimination fashion at the carbonyl carbon or in an SN2-fashion at the β-carbon.12,17 Therefore, to identify whether the hydroxide ions attack the carbonyl carbon (path A) or the β-carbon center (path B) of 4 (Scheme 6), an isotope labeling experiment with H218O was performed.

Scheme 6. Determination of the reaction pathway by nucleophilic attack of hydroxide ion.

A mixture of 18O-incorporated tropic acid (18O-3) and 3 was obtained by the hydrolysis of (RS)-4 with KOH (1 M) in H218O under general biphasic conditions using 11. The negative ESI mass spectrum revealed that the 18O content of the hydrolyzed mixture was 85%. Then, the mixture of 18O-3 and 3 was reduced to 2-phenyl-1,3-propanediol (18O-21 and 21) by LiAlH4 and then converted to the corresponding cyclic boronates (18O-23 and 23) of 3-dimethylaminophenylboronic acid (22) because the detection sensitivity of 18O-21 and 21 in mass spectrometry was extremely poor.18 The positive ESI mass spectra of the mixture of 18O-23 and 23 revealed that after the LiAlH4 reduction of the carboxyl group the 18O content decreased from 85% to 42%, thus demonstrating the nucleophilic attack of the hydroxide ion at the carbonyl carbon (Scheme 6).

The reaction mechanism of this asymmetric hydrolysis is considered as follows. Since the free OH group on the catalyst was not essential for the hydrolysis reaction itself but was needed to achieve high enantioselectivity, it was indicated that the free OH group acts as a general acid catalyst to activate the carbonyl group and control the lactone orientation. The hydroxide ion solvated by dichloromethane approached the less hindered face of the β-lactone carbonyl and interacted with the electron-deficient quinoline ring to produce tropic acid carboxylate via a tetrahedral intermediate. The geometry optimized structures of TS-1 (11·(S)-4·OH−) and TS-2 (11·(R)-4·OH−) obtained by density functional theory (DFT) calculations are shown in Fig. 1. The preferred orientation TS-1, which produced (S)-3 as the major enantiomer, showed better aromatic π–π interaction than TS-2. The value of energy difference (1.83 kcal mol−1) between TS-1 and TS-2 was reasonably in good accordance with the enantioselectivity.

Fig. 1. The geometry optimized structures of TS-1 (11·(S)-4·OH−) and TS-2 (11·(R)-4·OH−) by density functional theory (DFT) calculations (ωB97X-D/6-31G*) in CH2Cl2.

This study reported a successful DKR with high enantioselectivity under non-aqueous bi-phasic conditions where the asymmetric hydrolysis of racemic 3-phenyl-2-oxetanone (tropic acid β-lactone) was achieved using a chiral PTC and water-free basic anion exchange resin as the hydroxide ion donor. These findings open the potential for the PTC-catalyzed asymmetric transformations of water-labile substrates.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts to declare.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the financial support provided to M. K. through the Nagai Memorial Research Scholarship from the Pharmaceutical Society of Japan. We would also like to express our gratitude to Ms. Narumi Heishima for technical assistance.

Electronic supplementary information (ESI) available. See DOI: https://doi.org/10.1039/d3ra08594e

Notes and references

- Dei S. Bellucci C. Ghelardini C. Romanelli M. N. Spampinato S. Life Sci. 1996;58:2147–2153. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(96)00208-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dei S. Bartolini A. Bellucci C. Ghelardini C. Gualtieri F. Manetti D. Romanelli M. Scapecchi S. Teodori E. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 1997;32:595–605. doi: 10.1016/S0223-5234(97)83285-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenblum E. I. Taylor W. S. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 1955;7:328–333. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1955.tb12044.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitagawa I. Ishizu T. Ohashi K. Shibuya H. Yakugaku Zasshi. 2000;120:1017–1023. doi: 10.1248/yakushi1947.120.10_1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klomp D. Peters J. A. Hanefeld U. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 2005;16:3892–3896. doi: 10.1016/j.tetasy.2005.10.032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Atuu M. R. Mahmood S. J. Laib F. Hossain M. M. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 2004;15:3091–3101. doi: 10.1016/j.tetasy.2004.08.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang P.-Y. Tsai S.-W. J. Mol. Catal. B: Enzym. 2009;57:158–163. doi: 10.1016/j.molcatb.2008.08.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ooi T. Maruoka K. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2007;46:4222–4266. doi: 10.1002/anie.200601737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian D. Sun J. Chem.–Eur. J. 2019;25:3740–3751. doi: 10.1002/chem.201803752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakafuji K. Iwasa S. Ouchida K. N. Cho H. Dohi H. Yamamoto E. Kamachi T. Tokunaga M. ACS Catal. 2021;11:14067–14075. doi: 10.1021/acscatal.1c03076. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto E. Wakafuji K. Furutachi Y. Kobayashi K. Kamachi T. Tokunaga M. ACS Catal. 2018;8:5708–5713. doi: 10.1021/acscatal.8b00693. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold L. D. Kalantar T. H. Vederas J. C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1985;107:7105–7109. doi: 10.1021/ja00310a058. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Adams D. J., Dyson P. J. and Tavener S. J., Chemistry in Alternative Reaction Media, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, Chichester, 2003, pp. 1–31 [Google Scholar]

- Tanzer E. M. Schweizer W. B. Ebert M. O. Gilmour R. Chem.–Eur. J. 2012;18:2006–2013. doi: 10.1002/chem.201102859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirakawa S. Maruoka K. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013;52:4312–4348. doi: 10.1002/anie.201206835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirai T. Kanai M. Kuninobu Y. Org. Lett. 2018;20:1593–1596. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.8b00339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramer S. E. Moore R. N. Vederas J. C. Can. J. Chem. 1986;64:706–713. doi: 10.1139/v86-113. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Higashi T. Kawasaki K. Matsumoto N. Ogawa S. Mitamura K. Ikegawa S. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2013;61:326–332. doi: 10.1248/cpb.c12-00979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.