Abstract

Background:

A traumatic birth experience can affect the breastfeeding process and make it ineffective. The aim of this study was to identify the factors associated with breastfeeding ineffectiveness after birth trauma, through the world literature. There are several factors responsible for a traumatic birth experience, such as obstetric violence, postpartum complications and complications induced by doctors, invasive vaginal deliveries, emergency caesarean sections, admission of a neonate to the Neonatal Intensive Unit, past traumatic life events and mental health problems.

Objective:

The aim of this study was to identify the factors associated with breastfeeding ineffectiveness after birth trauma, through the world literature.

Methods:

An extended search was conducted to identify relevant for breastfeeding and traumatic birth experiences manuscripts for this study. Databases including PubMed, PsycINFO and Google Scholar. The search was limited to articles published in English the last decade.

Results:

Factors that contribute to the ineffectiveness of breastfeeding after a traumatic birth are hormonal, medication, insufficient support from the partner, reliving the traumatic birth experience, past traumatic experiences in the woman’s life and her mental state.

Conclusion:

The mental trauma during childbirth is complex and multifactorial. Therefore, it is necessary to take measures on the one hand to prevent mental trauma during childbirth and on the other hand to make interventions to deal with the consequences of the trauma on the mental health of the mother and on breastfeeding which is directly affected.

Keywords: Traumatic birth experience, birth trauma, breastfeeding, breastfeeding ineffectiveness, mental health

1. BACKGROUND

The birth experience is an important factor for later impacts for the woman and her relationship with the newborn, but also for the newborn. The staff of the clinic aims to create the conditions for a birth experience as pleasant as possible (1). The pregnant woman feels more familiar and more comfortable when she is surrounded by her intimate persons, such as her husband, and of course, her midwife (2). Her training in perinatal education classes has a positive effect on her psychology and body as well, so that she is well prepared for the labor and thus terminate it more easily (3). Psychological support during childbirth and support during labor are also important factors in preventing postpartum depression and other psychological disorders of the perinatal period (4).

However, there are several times that even though everything has been properly prepared and goes smoothly, an unexpected factor occurs, and the birth ends up being a traumatic birth experience. A traumatic birth can be caused either by non-compliance with the birth plan, the mismatch between women’s expectations or preferences and the actual birth experience (women who wanted to give birth naturally and gave birth by caesarean and vice versa), complications during delivery, emergency cesarean section and the need to put the neonate in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU) (5), (6).

Traumatic Birth Experience

“Traumatic childbirth” is defined as childbirth characterized by unpleasant experiences that have negative psychological consequences for the mother. A physical trauma to the mother or neonate may be common but not necessary to define a birth as traumatic (7). Incidents of birth plan compliance problems are the hiding of techniques that may have been used by the doctor or midwife that were not included in the original birth plan. For example, rupture of membranes without the woman’s permission and without informing her is a form of non-compliance with the birth plan (5). Women’s lack of information about the practices that will be carried out during childbirth, as well as their absence of consent in any act that requires it, causes women to feel insecure and insult their dignity. Furthermore, indifference to the pain of childbirth and the relief of the pregnant woman creates even greater doubt about a good delivery outcome for her (8). As for the complications that may exist and are related to actions mainly by doctors, there should be better care and techniques to prevent them from occurring (5). Such problems are, for example, cutting in a cesarean section before the anesthesia has even taken effect, or ineffective suturing, or tearing of the perineum in normal delivery due to incorrect instructions to the woman and malpractice by the doctor (5), (9). Also, complications such as anal sphincter injury, postpartum hemorrhage, and infections are among those that establish a traumatic birth. Complications of prolonged labor and epidural anesthesia can cause post-traumatic symptoms and therefore need immediate treatment (8). A negative birth experience has also been shown to be associated with a history of abuse as well as fear of childbirth resulting in these women needing more support from the health system (10).

Another important issue related to birth trauma is the development of the mother-fetus bond (11). If not achieved, is an equally important problem that leads to traumatic birth (5). Skin-to-skin contact immediately after birth and promotion of breastfeeding in many cases are not carried out. As a result, the woman sees childbirth as an uninteresting and less pleasant process (12). So, the aim of this study was to identify the factors associated with breastfeeding ineffectiveness after birth trauma, through the world literature.

Experiencing a traumatic birth can have lifelong effects. According to Diagnostic and Statistical Manual – 5th Version (DSM-5) (13) which refers to the psychiatric model, a traumatic childbirth is related more to the self-evaluation of the event and the person’s reactions to the event than the event itself. However, the impact of birth trauma can be particularly significant in women, because it doesn’t go away easily. Birth trauma can affect emotion (relationship issues, anxiety, stress, low self-esteem, panic disorders), and behavior (overeating, spending money, drinking alcohol, lashing out) (14). In fact, recent studies have shown that trauma can be transmitted through DNA, affecting the next generations, which are explained by the science of epigenetic (15). However, even if there is no direct genetic evidence, the effects of trauma on the next generation can be significant without being inherited (16) , through dysfunctional dynamics between family members and the traumatized mother, such as maladaptive attachment styles, or through telling family stories of traumatic events and memories through photographs, letters, or heirlooms (16).

On the other hand, the obstetric definition of traumatic childbirth is more related to the kind of delivery, such as cesarean section. In fact, it is widely known from the literature, that a large percentage of women who will undergo a cesarean section or an invasive vaginal delivery will experience psychological trauma (Table 1) (17).

Table 1. Factors responsible for traumatic birth experience.

| Factors | |

|---|---|

| Obstetric violence (5), (8) | Non-compliance of staff with the women’s birth plan, membrane sweeps, episiotomies, fundal pressure, use of forceps and spatulas, without giving any explanation to the woman, threats of violence or violence from the staff, indifference from the staff to the pain of childbirth |

| Postpartum complications (8) | Postpartum hemorrhage, anal sphincter injury, infections, epidural anesthesia complications |

| Complications induced by doctors (5), (9) | Cutting a cesarean section before the anesthesia has even taken effect, ineffective suturing, tearing of the perineum in vaginal delivery due to incorrect instructions to the woman |

| Type of delivery (18), (19), (20) | Emergency cesarean section, induction of labor, forceps delivery |

| Neonate’s health (5), (6), (19) | Need for NICU |

| Birth expectations (21) | Mismatch between women’s expectations or preferences and the actual birth experience |

| Life events (10), (19) | History of abuse, domestic violence |

| Psychological factors (10), (19), (20) | Fear of childbirth, anxiety, depression |

2. OBJECTIVE

The aim of this study was to identify the factors associated with breastfeeding ineffectiveness after birth trauma, through the world literature.

3. MATERIAL AND METHODS

Search Strategy

An extended search was conducted to identify relevant for breastfeeding and traumatic birth experiences manuscripts for this study. Databases including PubMed, PsycINFO and Google Scholar, were searched using a combination of keywords (MeSH) related to “breastfeeding”, “birth trauma” postpartum period” traumatic birth experience” breastfeeding ineffectiveness”. The search was limited to articles published in English the last decade.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The criteria that studies had to meet to be included in the review were: a) focused on the breastfeeding after birth trauma, b) research papers, c) reported on outcomes related to traumatic birth experience, d) were published in English language in peer-reviewed journals.

Data synthesis

Initial screening of article titles and abstracts was performed by two authors. Then, the articles were examined for their appropriateness of the content, based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. There were no deviations from the search.

Data analysis

There was considerable heterogeneity in the composition of the data; therefore, a narrative approach to the data was used. The results were organized in tables and graphs.

Ethics approval of research: No ethical approval was required.

4. RESULTS

The Insidence of birth trauma

According to the global research, the percentage of women who have experienced a traumatic birth, range between 23% to 45% (22), (23), (24). Considering the negative consequences on the health of the mother, the child and society in general, these rates, as long as they remain high, intensify traumatic childbirth into a public health problem. The phenomenon of psychological trauma after birth appears the same in low- and high-income countries (25), (26). Traumatic birth experience is defined and measured in different ways, from the woman‘s subjective perception of her delivery to the measurement of mental trauma through specific diagnostic criteria (27). A birth can be considered traumatic by a mother and normal by a professional. However, the mother‘s subjective assessment of her experience is the one that must be taken into account. According to Beck, traumatic childbirth has ripple effects for mothers. Some of these ripples can affect breastfeeding and their mental health, as the traumatic experience can develop into post-traumatic symptomatology (28). One in 4 women who report a traumatic birth experience will develop Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) (29).

Postpartum Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

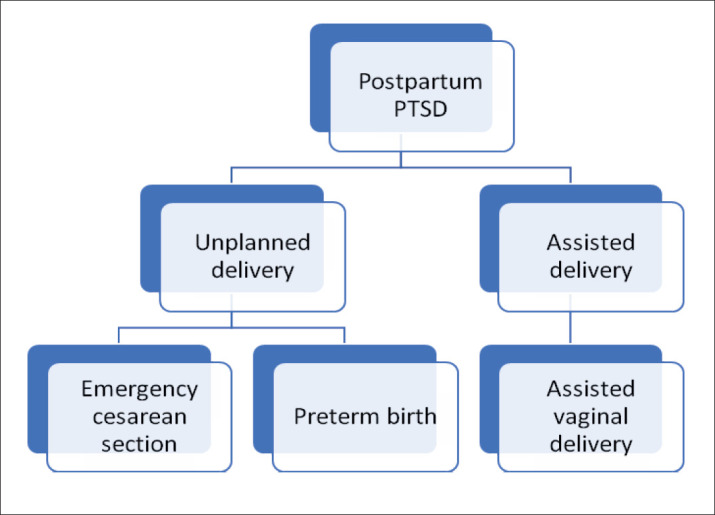

As described above, after a traumatic childbirth, postpartum woman may have been affected and at risk of psychological effects (18). However, it has been reported from women’s experiences that there were worse outcomes after assisted vaginal delivery or unplanned delivery compared to women who had a planned cesarean delivery rather than an assisted delivery (30). Women in the second case have reported better well-being after giving birth, while women in the first case reported traumatic mental health symptoms that required months after giving birth to overcome. Thus, women undergoing assisted vaginal delivery should be closely monitored for a period of time after delivery (31). According to a study carried out in Spain related to perinatal PTSD, factors affecting PTSD included changing the plan of delivery, emergency cesarean section or elective delivery with caesarean section, introduction of the neonate to the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit or Intermediate Care Unit, the type of feeding of the neonate when leaving the hospital and the various forms of obstetric violence, such as verbal or psycho-emotional violence of the woman (32).

Figure 1. Type of delivery and postpartum PTSD.

Indeed, the type of delivery, non-direct contact between mother and neonate and obstetric violence are the most significant factors for PTSD in postpartum women (20). Nevertheless, supporting women during childbirth and breastfeeding may be able to help and cure any form of psychological disorder in postpartum women (20), (33). According to Türkmen’s study (34) , there was a significant association between distress during childbirth, perception of traumatic birth, post-traumatic stress disorder and failure to establish exclusive breastfeeding.

A significant protective role in the risk for postpartum PTSD appeared to be played by the partner (35) , as well as direct breastfeeding within the first hour (36). Regarding the support of the husband, it seems certain that it acts as a protective factor for the appearance of anxiety, stress, and depression. However, no studies have been found that analyze the degree of support and the influence it has on the woman‘s psychology (32). The help of staff plays an equally important role in preventing the risk of postpartum PTSD. Midwives should intervene, especially in cases where a woman is exhausted and without mental reserve, to prevent a possibly worse psychological situation (37). Actually, a supported woman has better psychology than a woman who is not, making her feel that whatever comes up will be dealt with immediately (32).

Birth trauma and breastfeeding

Breastfeeding provides several important short-term and long-term benefits for the health of the infant and the mother. It is now known that breastfed infants have a lower risk of obesity, type 1 diabetes, asthma and sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS). Breastfed infants are also less likely to get infections and stomach bugs. At the same time, breastfeeding can reduce a mother‘s risk of various types of cancer (breast, ovarian), type 2 diabetes and hypertension (38). Furthermore, it is now documented that breastfeeding can also protect the mother‘s mental health (39) , in various ways. More specifically, the breastfeeding mother‘s sleep improves (40), stress and fatigue are less (41) and increases self-confidence (42).

The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends the initiation of breastfeeding within the first hour after birth, as well as exclusive breastfeeding for the first six months. After the introduction of solids, WHO suggests that mothers should continue breastfeeding until the age of two and above (43). However, despite the numerous benefits of breastfeeding its rates at a global level remain low (43). One of the possible explanations for this phenomenon is the implication of birth trauma in the initiation and establishment of breastfeeding. According to the Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion (44) , analysis of narratives following a traumatic birth experience includes the embodiment of mental pain of childbirth in the ineffectiveness of breastfeeding (44). Preventing traumatic childbirth and improving maternal mental health are key public health priorities, given the results of research linking poor maternal mental health to childhood effects such as, schizophrenia, autism spectrum disorders and Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (45).

However, evidence regarding the association between breastfeeding efficacies after a traumatic birth experience is scarce. In this study an attempt is made to search for the factors related to the ineffectiveness of breastfeeding after a birth trauma, through global literature.

The involvement of hormones and pharmaceutical interventions

Interestingly, hormones are involved in the onset of depressive symptoms. The oxytocinergic system, the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, and the dopaminergic system interact with important effects on lactation and infant bonding, protection from life-threatening situations, and regulation of the stress response (46) , (Table 2). So far, existing research evidence suggests that the central release of oxytocin contributes to the proper regulation of cortisol levels that favor a rapid return of the body to its initial state before stress. Furthermore, ACTH and glucose responses are significantly reduced in breastfeeding women (Table 1), (39).

Table 2. Factors contributing to breastfeeding ineffectiveness.

| Factors | Actions | Effects |

|---|---|---|

| Hormones (39), (46), (48), | higher than normal cortisol levels, lower endogenous oxytocin levels, | Negative on lactation and infant bonding |

| Pharmaceutical interventions (48),(52), (53) | exogenous administration of oxytocin, epidural pain relief | Negative on lactation and infant bonding |

| Re-experiencing of birth trauma (55), (58) | Avoid mental pain, brings back traumatic memories, | Negative to disappointment and feelings of failure that can lead to further trauma. |

| Lack of partner’s support (62), (63) | Unperceived support, intimate partner violence | Quick frustration, sore nipples depression, low self-esteem |

| Mental health status (21), (39), (73), (74) | Depressive symptoms, anxiety, mood disorders, PTSD | Cessation of breastfeeding, ineffectiveness |

| Past traumatic life events (75), (76), (77), (78) | Physical assault, sexual abuse mainly during childhood, perinatal loss and previous traumatic birth experience | Difficulty in separating the sexual role from the maternal role of the breasts |

Several studies have supported the effect of hormones on women’s response to birth trauma. One study showed that lower maternal salivary cortisol levels after breastfeeding, absence of breast-related complications at first month postpartum, and higher breastfeeding self-efficacy, were potential predictors of exclusive breastfeeding (47). In addition, the study of Krol (48) showed that mothers with PTSD had higher than normal cortisol levels during the postpartum period raising the possibility that postpartum PTSD is related to cortisol dysregulation. These findings may partially explain the association between exclusive breastfeeding and postpartum PTSD. In some other studies, high levels of endogenous oxytocin before or after birth have been found to be associated with increased mother-infant bonding and attachment, particularly in women with more anxiety and stress (46). However, the association of endogenous peripartum oxytocin secretion and positive maternal psychological reactions was found to be disrupted in women with traumatic childhood experiences (49). Therefore, following exposure to a perinatal traumatic event, higher levels of endogenous oxytocin are secreted, suggesting a normal adaptive mechanism through which reduced perception of negative situations is sought to reduce distress and consolidate breastfeeding (46).

On the other hand, the exogenous administration of oxytocin to induce or reduce the time of labor, seems to have a negative effect on the above physiological mechanism, potentially affecting the establishment of breastfeeding (50). Synthetic oxytocin has also been linked to high rates of anxiety disorders and depression regardless of maternal history or type of delivery (46) , perhaps from desensitization of endogenous oxytocin production from the administration of high doses of synthetic oxytocin (51).

Another factor that affects the breastfeeding process is epidural pain relief. It has been proven that the release of beta-endorphin dramatically after epidural pain relief, inhibiting oxytocin levels. According to Buckley (52) , the more epidural analgesia a mother receives during labor, the lower the oxytocin release. Also, due to the pharmaceutical intervention, it seems that the mental alertness of the mother and the baby is affected, which means that they are not ready for a direct breastfeeding relationship. According to research results (52), (53) , women take longer to recover from general anesthesia than men, despite reacting faster, experiencing more side effects and having a worse overall recovery. Medicines given in labor may also have an effect on the infant, including reduced early sucking. This can potentially affect the initiation of breastfeeding as the baby’s ability to latch effectively, express milk and stimulate the breast is affected (53).

Re-experiencing of birth trauma

The negative association between trauma and breastfeeding has been recognized for many years (54) , yet few studies have been conducted to understand the effect of the re-experiencing of birth trauma on breastfeeding (Table 2). It is a fact that a traumatic birth experience can create difficulties in breastfeeding from the beginning, and even undermine it completely (Table 1). For example, in a 2010 study in England, mothers who had a complicated vaginal delivery or an emergency cesarean section, were more likely to suffer from PTSD symptomatology and breastfeeding difficulties (31). An explanation for this phenomenon is that breastfeeding after a traumatic birth experience can cause flashbacks to the traumatic birth and finally, for the mother who is trying to avoid mental pain, breastfeeding can act as a repellant (55). On the contrary, breastfeeding can be an extremely healing process after a birth trauma. Breastfeeding can offer some mothers the opportunity to overcome the traumatic experience of birth by increasing their confidence and empowerment in their maternal role (56).

However, breastfeeding can provide maternal satisfaction after a traumatic birth experience by reducing stress (57) , according to some qualitative studies. Some mothers reported that breastfeeding helped them cope with their birth trauma memories (28) while, others reported that breastfeeding brought them back to reality when their thoughts relived the trauma (57). As we can see, the relationship of failure or lack of breastfeeding to birth trauma and PTSD is complex and bidirectional.

Breastfeeding for some mothers is an extension of birth. Therefore, failure to breastfeed can lead to frustration and thus exacerbate feelings of failure that follow a traumatic birth experience. So, for some women breastfeeding is part of the healing process of mental trauma, while for some others it is an unbearable process and further mental trauma (58).

Support from the partner

In addition to breastfeeding, partner support is considered an important protective factor against a traumatic birth experience (59), (32). By partner support, we mean women’s perception of partner support, especially during breastfeeding (Table 1). Partner support is an important factor in initiating and maintaining breastfeeding and in developing the mother’s self-confidence. Latching and positioning skills early in the postpartum period are key to establishing breastfeeding and providing breast milk. The challenges women face in terms of latching difficulties, breast engorgement, perceived insufficient milk production and fatigue, without support can lead them to stop breastfeeding (60). For example, if the mother feels that the father’s attitude towards breastfeeding is positive and supportive, there is a greater likelihood that she will continue to breastfeed (60). However, there are several studies that have shown that even simple interventions by partners, such as verbal encouragement to mothers or help with housework, are associated with exclusiveness and long duration of breastfeeding (61). But what really happens when the partner is abusive? Several studies have linked intimate partner violence with adverse maternal outcomes in pregnancy and with effects on the mother’s mental health (62). In addition, intimate partner violence can directly affect breastfeeding with symptoms e.g. sore nipples and quick frustration. Indirect symptoms include lack of support, depression, low self-esteem, increased dysphonic symptoms (63) , and postpartum women are more likely to have low social functioning and suicidal ideation (64).

On the other hand, birth trauma itself can cause problems in the balance of the couple’s relationship. According to Bailham (65) , even a year after the traumatic birth, some women did not want to have sex with their partners while Ayres’ study showed a high rate of disagreements and guilt between partners after the traumatic birth (66).

The impact of birth trauma on the couple’s relationship is significant, as healthy partner relationships are associated with improved maternal health. Of course, the quality of the couple’s relationship, in addition to breastfeeding, can also affect the well-being of the infant, and for this reason birth trauma must be prevented, recognized and treated (67).

Mental Health Status and Past Traumatic Life Events

There are several possible explanations for the difference in mood between breastfeeding and non-breastfeeding mothers after a traumatic birth. One of the possible explanations for this phenomenon is the poor mental state of postpartum women (39) , such as anxiety and mood disorders, as a result of a traumatic birth experience (Table 1). Indeed, several studies have reported that breastfeeding mothers have lower rates of depressive and anxiety symptoms (68), (69), (70), (71) , especially mothers who exclusively breastfed for a long time (72). Negative perceptions of breastfeeding have been documented as key factors in the depression-breastfeeding relationship. As a result, depressed mothers report lower breastfeeding rates (73). Furthermore, postpartum depression symptoms inversely increase mothers’ anxiety about breastfeeding and its ineffectiveness (74). More specifically, in a large study of 1480 women with data from the 8th week to the first 2 years postpartum, postpartum PTSD was significantly associated with cessation of breastfeeding (21).

In addition, the role of past traumatic life events, such as physical assault, sexual assault, perinatal loss and previous traumatic birth experience, affect the mother’s mental health and consequently the breastfeeding process (75). In some qualitative studies it has been reported as an explanation that women who have experienced sexual abuse during childhood may have trouble initiating and continuing exclusive breastfeeding due to difficulty in separating the sexual role from the maternal role of the breasts (76). In this case, the breast is the portal through which the old unhealed trauma is revived (77) through awareness (78).

5. CONCLUSION

From all the above, the mental trauma during childbirth is complex and multifactorial and therefore, should be considered as a special problem during the postpartum period. The process of recovering from birth trauma is a difficult and demanding journey for mothers and their families because the trauma brings out past traumas, partner relationship problems and mental health issues.

However, given the great impact of birth trauma on breastfeeding, it is vital to take measures to detect symptoms of psychological trauma early after a difficult birth, to educate women to seek help early and finally, to educate all perinatal care professionals about the factors responsible for birth trauma, but also the factors that aggravate an existing traumatic experience. Further research is needed to elucidate the factors associated with breastfeeding ineffectiveness after birth trauma, from the perspective of the mother as well as the perception of health professionals. Finally, the birth trauma-breastfeeding relationship is expected to continue to be explored in order to update and further advance knowledge on this topic.

Patient Consent Form:

Not applicable.

Author's contribution:

Conceptualization, M.T.C and E.O; methodology, R.S.; validation, P.E and M.D.; investigation, E.A.; writing—original draft preparation, M.T.C.; writing—review and editing, M.I., E.P., and E.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest:

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Financial support and sponsorship:

This research received no external funding.

REFERENCES

- 1.Karlström A, Nystedt A, Hildingsson I. The meaning of a very positive birth experience: focus groups discussions with women. [2023 Apr 10];BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth Internet. 2015 Oct 9;15(1):251. doi: 10.1186/s12884-015-0683-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lunda P, Minnie CS, Benadé P. Women’s experiences of continuous support during childbirth: a meta-synthesis. [2023 Apr 10];BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth Internet. 2018 May 15;18(1):167. doi: 10.1186/s12884-018-1755-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mueller CG, Webb PJ, Morgan S. The Effects of Childbirth Education on Maternity Outcomes and Maternal Satisfaction. [2023 Apr 10];J Perinat Educ Internet. 2020 Jan 1;29(1):16–22. doi: 10.1891/1058-1243.29.1.16. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6984379/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Taheri M, Takian A, Taghizadeh Z, Jafari N, Sarafraz N. Creating a positive perception of childbirth experience: systematic review and meta-analysis of prenatal and intrapartum interventions. [2023 Apr 10];Reproductive Health Internet. 2018 May 2;15(1):73. doi: 10.1186/s12978-018-0511-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rodríguez-Almagro J, Hernández-Martínez A, Rodríguez-Almagro D, Quirós-García JM, Martínez-Galiano JM, Gómez-Salgado J. Women’s Perceptions of Living a Traumatic Childbirth Experience and Factors Related to a Birth Experience. [2020 Dec 29];Int J Environ Res Public Health Internet. 2019 May;16(9) doi: 10.3390/ijerph16091654. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6539242/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang K, Dai L, Wu M, Zeng T, Yuan M, Chen Y. Women’s experience of psychological birth trauma in China: a qualitative study. [2023 Apr 10];BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth Internet. 2020 Oct 27;20(1):651. doi: 10.1186/s12884-020-03342-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Greenfield M, Jomeen J, Glover L. What is traumatic birth? A concept analysis and literature review. [2023 Apr 10];British Journal of Midwifery Internet. 2016 Apr 2;24(4):254–267. Available from: https://www.magonlinelibrary.com/doi/abs/10.12968/bjom.2016.24.4.254 . [Google Scholar]

- 8.Annborn A, Finnbogadóttir HR. Obstetric violence a qualitative interview study. Midwifery. 2022 Feb;105:103212. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2021.103212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rusavy Z, Francova E, Paymova L, Ismail KM, Kalis V. Timing of cesarean and its impact on labor duration and genital tract trauma at the first subsequent vaginal birth: a retrospective cohort study. [2023 Apr 10];BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth Internet. 2019 Jun 20;19(1):207. doi: 10.1186/s12884-019-2359-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smarandache A, Kim THM, Bohr Y, Tamim H. Predictors of a negative labour and birth experience based on a national survey of Canadian women. [2023 Apr 10];BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth Internet. 2016 May 18;16(1):114. doi: 10.1186/s12884-016-0903-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Researchers Explore the Science Behind the Maternal-Fetal Bond Internet. 2020. [2023 Apr 10]. Available from: https://pew.org/2GWXla0 .

- 12.Research on skin-to-skin contact–Baby Friendly Initiative Internet. [2023 Apr 10]. Available from: https://www.unicef.org.uk/babyfriendly/news-and-research/baby-friendly-research/research-supporting-breastfeeding/skin-to-skin-contact/

- 13.American Psychiatric Association, American Psychiatric Association. 5th. Washington, D.C: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5; p. 947. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brunson E, Thierry A, Ligier F, Vulliez-Coady L, Novo A, Rolland AC, et al. Prevalences and predictive factors of maternal trauma through 18 months after premature birth: A longitudinal, observational and descriptive study. [2021 Dec 30];PLOS ONE Internet. 2021 Feb 24;16(2):e0246758. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0246758. Available from: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0246758 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Psych Central Internet. Genetic Trauma: Can Trauma Be Passed Down to Future Generations? 2022. [2023 Jul 29]. Available from: https://psychcentral.com/health/genetic-trauma .

- 16.Yehuda R, Lehrner A. Intergenerational transmission of trauma effects: putative role of epigenetic mechanisms. [2023 Jul 29];World Psychiatry Internet. 2018 Oct;17(3):243–257. doi: 10.1002/wps.20568. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6127768/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Murphy DJ, Pope C, Frost J, Liebling RE. Women’s views on the impact of operative delivery in the second stage of labour: qualitative interview study. BMJ. 2003 Nov 15;327(7424):1132. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7424.1132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Australia H. Birth trauma (emotional) Internet. Healthdirect Australia. 2022. [2023 Apr 10]. Available from: https://www.pregnancybirthbaby.org.au/birth-trauma-emotional .

- 19.What is Birth Trauma?–Birth Trauma Association Internet. [2021 Jan 3]. Available from: https://www.birthtraumaassociation.org.uk/for-parents/what-is-birth-trauma# .

- 20.El Founti Khsim I, Martínez Rodríguez M, Riquelme Gallego B, Caparros-Gonzalez RA, Amezcua-Prieto C. Risk Factors for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder after Childbirth: A Systematic Review. [2023 Apr 10];Diagnostics Internet. 2022 Nov;12(11):2598. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics12112598. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2075-4418/12/11/2598 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Garthus-Niegel S, von Soest T, Knoph C, Simonsen TB, Torgersen L, Eberhard-Gran M. The influence of women’s preferences and actual mode of delivery on post-traumatic stress symptoms following childbirth: a population-based, longitudinal study. [2021 Jan 3];BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth Internet. 2014 Jun 5;14(1):191. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-14-191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sawyer A, Ayers S, Young D, Bradley R, Smith H. Posttraumatic growth after childbirth: a prospective study. Psychol Health. 2012;27(3):362–377. doi: 10.1080/08870446.2011.578745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alcorn KL, O’Donovan A, Patrick JC, Creedy D, Devilly GJ. A prospective longitudinal study of the prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder resulting from childbirth events. Psychol Med. 2010 Nov;40(11):1849–1859. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709992224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bay F, Sayiner FD. Perception of traumatic childbirth of women and its relationship with postpartum depression. Women Health. 2021;61(5):479–489. doi: 10.1080/03630242.2021.1927287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Akuamoah-Boateng J, Spencer R. Woman-ce ntered care: Women’s experiences and perceptions of induction of labor for uncomplicated post-term pregnancy: A systematic review of qualitative evidence. [2023 Jun 4];Midwifery Internet. 2018 Dec 1;67:46–56. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2018.08.018. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S026661381730013X . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nagle U, Naughton S, Ayers S, Cooley S, Duffy RM, Dikmen-Yildiz P. A survey of perceived traumatic birth experiences in an Irish maternity sample – prevalence, risk factors and follow up. [2023 Jun 4];Midwifery Internet. 2022 Oct 1;113:103419. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2022.103419. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0266613822001693 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sun X, Fan X, Cong S, Wang R, Sha L, Xie H, et al. Psychological birth trauma: A concept analysis. [2023 Jun 4];Front Psychol Internet. 2023 Jan 13;13:1065612. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1065612. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9880163/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Beck CT, Watson S. Impact of birth trauma on breast-feeding: a tale of two pathways. Nurs Res. 2008 Aug;57(4):228–236. doi: 10.1097/01.NNR.0000313494.87282.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Orovou E, Dagla M, Iatrakis G, Lykeridou A, Tzavara C, Antoniou E. Correlation between Kind of Cesarean Section and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in Greek Women. [2020 Mar 6];International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health Internet. 2020 Jan;17(5):1592. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17051592. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/17/5/1592 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Karlström A. Women’s self-reported experience of unplanned caesarean section: Results of a Swedish study. Midwifery. 2017 Jul;50:253–258. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2017.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rowlands IJ, Redshaw M. Mode of birth and women’s psychological and physical wellbeing in the postnatal period. [2021 Aug 31];BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth Internet. 2012 Nov 28;12(1):138. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-12-138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Martinez-Vázquez S, Rodríguez-Almagro J, Hernández-Martínez A, Martínez-Galiano JM. Factors Associated with Postpartum Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) Following Obstetric Violence: A Cross-Sectional Study. [2021 Oct 15];Journal of Personalized Medicine Internet. 2021 May;11(5):338. doi: 10.3390/jpm11050338. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2075-4426/11/5/338 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rivi V, Petrilli G, Blom JMC. Mind the Mother When Considering Breastfeeding. [2023 Apr 10];Front Glob Womens Health Internet. 2020 Sep 15;1:3. doi: 10.3389/fgwh.2020.00003. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8593947/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Türkmen H, Yalniz Dilcen H, Akin B. The Effect of Labor Comfort on Traumatic Childbirth Perception, Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, and Breastfeeding. [2021 Oct 20];Breastfeeding Medicine Internet. 2020 Dec 1;15(12):779–788. doi: 10.1089/bfm.2020.0138. Available from: https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/abs/10.1089/bfm.2020.0138 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fathers & Partners – Birth Trauma Internet. [2023 Apr 23]. Available from: https://birthtrauma.org.au/fathers-and-partners/

- 36.Chen J, Lai X, Zhou L, Retnakaran R, Wen SW, Krewski D, et al. Association between exclusive breastfeeding and postpartum post-traumatic stress disorder. [2023 Apr 23];International Breastfeeding Journal Internet. 2022 Nov 23;17(1):78. doi: 10.1186/s13006-022-00519-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aydın R, Aktaş S. Midwives’ experiences of traumatic births: A systematic review and meta-synthesis. [2023 Apr 23];Eur J Midwifery Internet. 2021 Jul 26;5:31. doi: 10.18332/ejm/138197. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8312097/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Internet. Five Great Benefits of Breastfeeding. 2021. [2023 May 6]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/dnpao/features/breastfeeding-benefits/index.html .

- 39.Tucker Z, O’Malley C. Mental Health Benefits of Breastfeeding: A Literature Review. [2023 May 6];Cureus Internet. 14(9):e29199. doi: 10.7759/cureus.29199. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9572809/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wayback Machine Internet. 2015. [2023 Aug 4]. Available from: http://web.archive.org/web/20150425015326/http://www.kathleenkendall-tackett.com/kendall-tackett_CL_2-2.pdf .

- 41.Main Internet. [2023 Aug 4]. Available from: https://www.kathleenkendall-tackett.com/

- 42.Hoyt-Austin A, Hazrati S, Berlin S, Hourigan S, Bodnar K. Association of Maternal Confidence and Breastfeeding Practices in Hispanic Women Compared to Non-Hispanic White Women. [2023 Aug 4];Glob Pediatr Health Internet. 2021 Dec 22;8:2333794X211062439. doi: 10.1177/2333794X211062439. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8725025/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.WHO Internet. World Health Organization. WHO | Breastfeeding. [2022 Dec 20]. Available from: http://www.who.int/nutrition/topics/exclusive_breastfeeding/en/

- 44.Health promoting strategies for breastfeeding | Journal of Nursing Science and Health Internet. [2023 Jun 1]. Available from: https://he01.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/nah/article/view/143710 .

- 45.Chan JC, Nugent BM, Bale TL. Parental advisory: maternal and paternal stress can impact offspring neurodevelopment. [2023 Aug 4];Biol Psychiatry Internet. 2018 May 15;83(10):886–894. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2017.10.005. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5899063/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Witteveen AB, Stramrood CAI, Henrichs J, Flanagan JC, van Pampus MG, Olff M. The oxytocinergic system in PTSD following traumatic childbirth: endogenous and exogenous oxytocin in the peripartum period. [2023 May 31];Arch Womens Ment Health Internet. 2020 Jun 1;23(3):317–329. doi: 10.1007/s00737-019-00994-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shiraishi M, Matsuzaki M, Kurihara S, Iwamoto M, Shimada M. Post-breastfeeding stress response and breastfeeding self-efficacy as modifiable predictors of exclusive breastfeeding at 3 months postpartum: a prospective cohort study. [2023 May 31];BMC Pregnancy Childbirth Internet. 2020 Nov 25;20:730. doi: 10.1186/s12884-020-03431-8. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7687691/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Krol KM, Kamboj SK, Curran HV, Grossmann T. Breastfeeding experience differentially impacts recognition of happiness and anger in mothers. [2023 May 31];Sci Rep Internet. 2014 Nov 12;4:7006. doi: 10.1038/srep07006. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4228331/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Julian MM, Rosenblum KL, Doom JR, Leung CYY, Lumeng JC, Cruz MG, et al. Oxytocin and parenting behavior among impoverished mothers with low vs. high early life stress. [2023 Jun 3];Arch Womens Ment Health Internet. 2018 Jun 1;21(3):375–382. doi: 10.1007/s00737-017-0798-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gu V, Feeley N, Gold I, Hayton B, Robins S, Mackinnon A, et al. Intrapartum Synthetic Oxytocin and Its Effects on Maternal Well-Being at 2 Months Postpartum. [2023 Jun 3];Birth Internet . 2016 43(1):28–35. doi: 10.1111/birt.12198. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/birt.12198 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kroll-Desrosiers AR, Nephew BC, Babb JA, Guilarte-Walker Y, Moore Simas TA, Deligiannidis KM. Association of peripartum synthetic oxytocin administration and depressive and anxiety disorders within the first postpartum year. [2023 Jun 3];Depression and Anxiety Internet. 2017 34(2):137–146. doi: 10.1002/da.22599. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/da.22599 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Anaesthetic’s effect on women. 2001. Mar 22, [2023 Aug 4]. Available from: http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/health/1236380.stm .

- 53.Lind JN, Perrine CG, Li R. Relationship between Use of Labor Pain Medications and Delayed Onset of Lactation. [2023 Aug 4];J Hum Lact Internet. 2014 May;30(2):167–173. doi: 10.1177/0890334413520189. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4684175/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Grajeda R, Pérez-Escamilla R. Stress during labor and delivery is associated with delayed onset of lactation among urban Guatemalan women. J Nutr. 2002 Oct;132(10):3055–3060. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.10.3055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Beck CT. A metaethnography of traumatic childbirth and its aftermath: amplifying causal looping. Qual Health Res. 2011 Mar;21(3):301–311. doi: 10.1177/1049732310390698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Elmir R, Schmied V, Wilkes L, Jackson D. Women’s perceptions and experiences of a traumatic birth: a meta-ethnography. J Adv Nurs. 2010 Oct;66(10):2142–2153. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05391.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.>Birth Experiences, Breastfeeding, and the Mother-Child Relationship: Evidence from a Large Sample of Mothers–Abi M. B. Davis, Valentina Sclafani, 2022 Internet. [2023 May 31]. Available from: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/08445621221089475 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 58.Klein M, Vanderbilt D, Kendall-Tackett K. PTSD and Breastfeeding: Let It Flow. [2021 Jan 19];ICAN: Infant, Child, & Adolescent Nutrition Internet. 2014 Aug 1;6(4):211–215. doi: 10.1177/1941406414541665. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Durmazoğlu G, Çiçek Ö, Okumuş H. The effect of spousal support perceived by mothers on breastfeeding in the postpartum period. [2023 Jun 3];Turk Arch Pediatr Internet. 2021 Jan 1;56(1):57–61. doi: 10.14744/TurkPediatriArs.2020.09076. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8114611/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mannion CA, Hobbs AJ, McDonald SW, Tough SC. Maternal perceptions of partner support during breastfeeding. [2023 Jun 4];Int Breastfeed J Internet. 2013 May 8;8:4. doi: 10.1186/1746-4358-8-4. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3653816/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Srisopa P, Lucas R. Maternal perception of paternal breastfeeding support: A secondary qualitative analysis. [2023 Jun 4];Midwifery Internet. 2021 Nov 1;102:103067. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2021.103067. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0266613821001467 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Paulson JL. Intimate Partner Violence and Perinatal Post-Traumatic Stress and Depression Symptoms: A Systematic Review of Findings in Longitudinal Studies. [2021 Nov 1];Trauma, Violence, & Abuse Internet. 2020 Nov 28;1524838020976098 doi: 10.1177/1524838020976098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Normann AK, Bakiewicz A, Madsen FK, Khan KS, Rasch V, Linde DS. Intimate partner violence and breastfeeding: a systematic review. [2023 Jun 9];BMJ Open Internet . 2020 Oct 1;10(10):e034153. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-034153. Available from: https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/10/10/e034153 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tran LM, Nguyen PH, Naved RT, Menon P. Intimate partner violence is associated with poorer maternal mental health and breastfeeding practices in Bangladesh. [2023 Aug 5];Health Policy and Planning Internet. 2020 Nov 1;35(Supplement_1):i19–29. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czaa106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bailham D, Joseph S. Post-traumatic stress following childbirth: A review of the emerging literature and directions for research and practice. [2023 Jun 4];Psychology, Health & Medicine Internet. 2003 May 1;8(2):159–168. doi: 10.1080/1354850031000087537. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ayers S, Eagle A, Waring H. The effects of childbirth-related post-traumatic stress disorder on women and their relationships: a qualitative study. Psychol Health Med. 2006 Nov;11(4):389–398. doi: 10.1080/13548500600708409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Delicate A, Ayers S. The impact of birth trauma on the couple relationship and related support requirements; a framework analysis of parents’ perspectives. [2023 Aug 5];Midwifery Internet. 2023 Aug 1;123:103732. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2023.103732. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0266613823001353 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Figueiredo B, Canário C, Field T. Breastfeeding is negatively affected by prenatal depression and reduces postpartum depression. [2023 May 6];Psychological Medicine Internet . 2014 Apr;44(5):927–936. doi: 10.1017/S0033291713001530. Available from: https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/psychological-medicine/article/abs/breastfeeding-is-negatively-affected-by-prenatal-depression-and-reduces-postpartum-depression/EA17120DDFCA7FE1D4A5645D9A4E2DD3 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Figueiredo B, Pinto TM, Costa R. Exclusive Breastfeeding Moderates the Association Between Prenatal and Postpartum Depression. J Hum Lact. 2021 Nov;37(4):784–794. doi: 10.1177/0890334421991051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.The significance of breastfeeding practices on postpartum depression risk. [2023 May 6]. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/phn.12969 . [DOI] [PubMed]

- 71.Mikšić Š, Uglešić B, Jakab J, Holik D, Milostić Srb A, Degmečić D. Positive Effect of Breastfeeding on Child Development, Anxiety, and Postpartum Depression. [2023 May 6];International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health Internet. 2020 Jan;17(8):2725. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17082725. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/17/8/2725 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Xia M, Luo J, Wang J, Liang Y. Association between breastfeeding and postpartum depression: A meta-analysis. [2023 May 6];Journal of Affective Disorders Internet. 2022 Jul 1;308:512–519. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2022.04.091. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S016503272200430X . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Dennis CL, McQueen K. Does maternal postpartum depressive symptomatology influence infant feeding outcomes? Acta Paediatr. 2007 Apr;96(4):590–594. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2007.00184.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Pope CJ, Mazmanian D. Breastfeeding and Postpartum Depression: An Overview and Methodological Recommendations for Future Research. [2023 May 31];Depress Res Treat Internet. 2016 2016:4765310. doi: 10.1155/2016/4765310. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4842365/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Suarez A, Yakupova V. Past Traumatic Life Events, Postpartum PTSD, and the Role of Labor Support. [2023 Jun 9];International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health Internet. 2023 Jan;20(11):6048. doi: 10.3390/ijerph20116048. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/20/11/6048 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wood K, Van Esterik P. Infant feeding experiences of women who were sexually abused in childhood. Can Fam Physician. 2010 Apr;56(4):e136–141. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Coles J. Qualitative study of breastfeeding after childhood sexual assault. J Hum Lact. 2009 Aug;25(3):317–324. doi: 10.1177/0890334409334926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Huhtala M, Korja R, Lehtonen L, Haataja L, Lapinleimu H, Rautava P, et al. Associations between parental psychological well-being and socio-emotional development in 5-year-old preterm children. Early Hum Dev. 2014 Mar;90(3):119–124. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2013.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]