Abstract

Background

Meningiomas account for ~25% of all primary brain tumors. These tumors have a relatively favorable prognosis with ~92% of meningioma patients surviving >5 years after diagnosis. Yet, patients can report high disease burden and survivorship issues even years after treatment, affecting health-related quality of life (HRQOL). We aimed to systematically review the literature and synthesize evidence on HRQOL in meningioma patients across long-term survival, defined as ≥2 years post-diagnosis.

Methods

Systematic literature searches were carried out using Medline, EMBASE, CINAHL, PsycINFO, and Web of Science Core Collection. Any published, peer-reviewed articles with primary quantitative, qualitative, or mixed-methods data covering the physical, mental, and/or social aspects of HRQOL of meningioma survivors were included. A narrative synthesis method was used to interpret the findings.

Results

Searches returned 2253 unique publications, of which 21 were included. Of these, N = 15 involved quantitative methodology, N = 4 mixed methods, and N = 2 were qualitative reports. Patient sample survival ranged from 2.75 to 13 years. HRQOL impairment was seen across all domains. Physical issues included persevering symptoms (eg, headaches, fatigue, vision problems); mental issues comprised emotional burden (eg, high prevalence of depressive symptoms and anxiety) and cognitive complaints; social issues included role limitations, social isolation, and affected work productivity. Due to study heterogeneity, the impact of treatment on long-term HRQOL remains unclear.

Conclusions

The findings from this review highlight the areas of HRQOL that can be impacted in long-term survivorship for patients with meningioma. These findings could help raise awareness among clinicians and patients, facilitating support provision.

Keywords: disease burden, health-related quality of life, meningioma, mixed-methods, survivorship

Key Points.

Long-term survivors of meningioma experience health-related quality-of-life impairment.

Physical, emotional, and social functioning are affected.

Further research is needed to determine the impact of treatment.

Importance of the Study.

Patients diagnosed with meningioma can experience a high disease burden, yet little is known about long-term health-related quality-of-life (HRQOL) outcomes. This systematic review of 21 publications on HRQOL of long-term survivors of meningioma (≥2 years post-diagnosis) highlights impairment across physical, mental, and social functioning. Study heterogeneity precluded conclusions on the impact of treatment, which requires further investigation. The findings suggest that despite the generally favorable prognosis, meningioma patients could benefit from supportive care into longer-term survivorship to limit the impact of diagnosis/treatment on everyday life.

Meningiomas make up approximately 25% of all primary brain tumors diagnosed in the UK.1 Symptoms can vary depending on size, location, and grade, and may include motor or sensory deficits, seizures, and/or other functional impairments.2,3 Meningiomas are often benign and removable through surgery,4 with some patients managed through “watch-and-wait” strategy until intervention may become necessary. However, despite high survival rates, patients may experience long-term impaired daily functioning such as problems with memory, executive function, or language processing,5 which can negatively influence their health-related quality of life (HRQOL).3

HRQOL is a multidimensional concept that covers the physical, mental, and social aspects of a patient’s life.6 Diagnosis and treatment can have significant implications on different domains of HRQOL. One systematic review has found when compared with glioma populations, meningioma patients have fewer cognitive and emotional complaints.2 Yet other studies have found that patients diagnosed with meningioma have more greatly impaired HRQOL than the general population.3 In the longer term, a study on neurocognitive functioning and HRQOL in patients with skull base meningioma (≥5 years since diagnosis) found that patients reported a clinically relevant impairment of emotional and physical role functioning compared to informal caregivers as controls.7 However, findings may not be generalizable to other meningioma subgroups. In general, the long-term impact of a meningioma diagnosis on HRQOL is not well represented in the literature. Obtaining a clearer picture of HRQOL in meningioma survivors will help inform both patients and clinicians of any long-term consequences of treatment, and could identify areas of unmet support needs. Therefore, the aim of this systematic review is to provide an overview of the literature depicting the HRQOL of meningioma patients across long-term survival, which we defined as ≥2 years since diagnosis.

Methods

Search Methods

This review was reported in line with PRISMA guidelines, where applicable.8 The following databases were searched: PubMed/Medline, Embase, PsycInfo, and Web of Science. These searches were completed on 17 November 2022. The search terms and strategies were created with advice from an information specialist (J.W., see Acknowledgments), specifically for the following concepts: meningioma, adult, HRQOL, and long-term survivorship. Search strategies were developed using a combination of free-text terms and subject headings. No limit was placed on time since publication. See Supplementary Material 1 for the complete search strategy. The protocol for this review was registered on PROSPERO (CRD42020207211). Literature titles found were exported to EndNote X9 software where the duplicate removal function was used followed by title/abstract screening.

Selection Criteria

Literature was included according to the following criteria:

Human, adult participants (≥18 years old): if samples included mixed age groups, then the proportion of adults (≥18 years old) had to be over 50%.

Patients with WHO grade I and II meningiomas (or imaging suggestive of this where a tissue diagnosis was not feasible, eg, small tumors undergoing a “wait and see” approach or optic nerve meningioma). Grade III meningiomas were excluded due to their more aggressive nature and, as such, relatively different disease trajectory.

Mean/median time since diagnosis (TSD) had to be ≥2 years. This cutoff allowed us to assess HRQOL after diagnosis, while providing the earliest indication of “long-term” survival.

Published in English language.

Studies must have included either quantitative or qualitative, self-reported measures of HRQOL (eg, questionnaires, interviews, etc.).

Exclusion criteria were as follows:

Reviews, case studies, and case reports.

Reporting on other primary or secondary brain tumors only.

Studies using nonself-reported measures of HRQOL, for example, clinician- or proxy-reported outcomes.

Articles were assessed for eligibility in 2 stages (title/abstract then full text), by the lead investigator (S.F.). Conference abstracts could be included if these contained sufficient detail. As prespecified in the protocol (PROSPERO CRD42020207211), a second reviewer (F.B.) independently screened a random sample (20%) at each stage. Of these original libraries, we found a discrepancy of 11% at title screening. The lead reviewer (S.F.) revisited the inclusion and exclusion criteria related to discrepancies to ensure consistency of study selection.

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

Data extraction was carried out using a standardized template. Data extracted included study design, study outcomes, sample size, and participant selection criteria, as well as the selected method used to report on HRQOL. Outcome data were extracted in line with the themes derived from Hays & Reeve’s definition of HRQOL—“how well a person functions in their life and his or her perceived wellbeing in physical, mental & social domains of health.”6 We used the Mixed-Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT)9 for the quality assessment of the included studies. Following quality assessment, no studies were removed; however, studies of lower quality should be interpreted with caution and in consideration of their limitations. See Supplementary Material 2 for MMAT scores.

Narrative Synthesis

Narrative synthesis methods were used to interpret findings10 due to the variety of HRQOL outcomes. Evidence was categorized based on the themes of our chosen definition of HRQOL.6 This included physical, mental, and social aspects affected by diagnosis or treatment, with added domains where appropriate based on themes emerging from included papers, for example, fatigue, coping, and positive changes. Associations between sociodemographic and/or clinical characteristics in relation to HRQOL impairment were also considered, where possible.

Results

Search Results

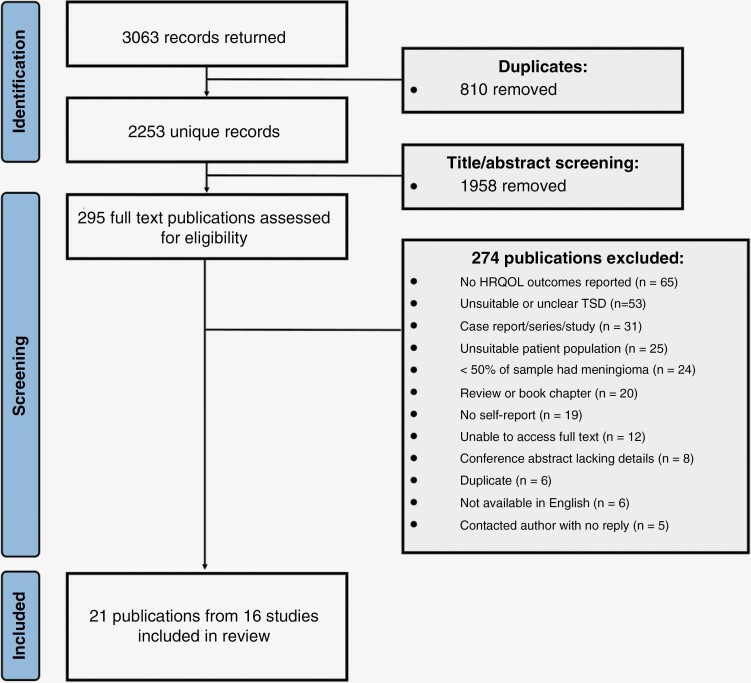

A total of 2657 hits were returned from initial searches with a further 406 added through an updated search. Removing duplicates using EndNote software left 2253 titles for screening. Following title/abstract screening, 295 publications remained for full-text screening. In total, 21 publications were included for data extraction and narrative synthesis. See Figure 1 for screening results and reasons for exclusion.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of screening process. HRQOL, health-related quality of life; TSD, time since diagnosis.

Study Characteristics

This review included 71% (N = 15) quantitative methodology articles, 19% (N = 4) mixed methods, and 10% (N = 2) qualitative articles, from 16 unique studies. Seventy-four percent of publications (N = 15) originated from Europe. Sample sizes within publications ranged from N = 1611 to N = 1852,12 and mean/median TSD ranged from 2.7513,14 to 1315 years. In total, 3864 unique study participants were represented (age range: 16–92), of whom 2709 (70%) were female. Seizure prevalence (reported in 6 publications12–14,16–18) ranged between 3.4%17 to 24.4%.18 There were various outcome measures for HRQOL used across these studies, with the Short Form-36 (38%; N = 8) and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (24%; N = 5) most commonly reported. Study characteristics can be found in Table 1.

Table 1.

Study characteristics

| Reference number | Author | Year | Title | TSD (years) | Methodology | Location | Sample style (n =) | Study design | Controls/comparison sample | Study aims | Instrument | Clinical significance cut off | Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 19 | Kangas, Williams and Smee | 2011 | Benefit finding in adults treated for benign meningioma brain tumour patients: relations with psychosocial wellbeing | 4.4 years | Quantitative | Australia | Benign meningioma patient sample (n = 70) | Cross-sectional observational | N/A | Investigate the association between BF and demographic and psychosocial variables | -Profile of Mood States Subscales: - -Impact of Event Scale |

->7 [S.R 11] -N/A |

Radiation -One course of radiation (“Early subgroup”: 85%; “Late” subgroup: 44%) -Multiple treatments (“Early subgroup”: 15%; “Late” subgroup: 56%) |

| 13 | Van der vossen, schepers, van der sprenkel, vissermeily, post | 2014 | Cognitive and emotional problems in patients after cerebral meningioma surgery | 32.6 months (postoperative) | Quantitative | The Netherlands | Patients operated on for a cerebral meningioma (n = 194) | Cross-sectional observational | N/A | Determine long-term cognitive complaints an symptoms of depression or anxiety in patients following surgery and related factors | -Cognitive Failures Questionnaire -HADS |

-N/A ->11 |

- Neurosurgery |

| 20 | Najafabadi; van der Meer, Boele, Taphoorn, Klein, Peerdman, van Furth, Dirven | 2020 | Determinants and predictors for the long-term disease burden of intracranial meningioma patients | 10 years since diagnosis | Quantitative | The Netherlands | WHO Grade I/II meningioma (n = 190) | Cross-sectional observational | N/A | Assess the determinants for long-term disease burden, defined as impaired HRQOL and neurocognitive functioning | -surveys- 36 | -N/A | -Mixed (surgery as initial treatment: 88%; radiotherapy as initial treatment: 5%) |

| 21 | Niewenhuizen, Klein, Stalpers, Leenstra, Heimans, Reijneveld | 2007 | Differential effect of surgery and radiotherapy on neurocognitive functioning and health-related quality of life in WHO grade I meningioma | Surgery only group: 3 years Surgery + RT: 7.6 years |

Quantitative | The Netherlands | WHO Grade I meningioma (n = 18) | Cross-sectional observational | RT group vs. RT + surgery | Quantify the effects of conventional RT vs. RT + surgery | -SF-36 -EORTC BN20 |

-N/A -N/A |

- Neurosurgery - Radiotherapy |

| 16 | Combs, Adeberg, Dittmar, Welzel, Reiken, Habermehl, Huber, Debus | 2013 | Skull based meningiomas: long-term results and patient self-reported out come in 507 patients treated with fractioned stereotactic radiotherapy | 107 months | Quantitative | Germany | Skull-base meningioma patients (n = 340) | Cross-sectional observational | N/A | Evaluate long-term toxicity and QOL as a result of fractionated stereotactic radiotherapy or intensity modulated radiotherapy | -Un-validated questionnaire | -N/A | - Neurosurgery (54%) - Radiotherapy (74%) |

| 22 | Timmer, Seibi-Leven, Wittenstein, Grau, Stravrinou, Rohn, Krishek, Coldbrunner | 2019 | Long-term outcomes and HRQOL of elderly patients after meningioma surgery | 3.8 years | Mixed methods | Germany | Meningioma patients who had undergone surgical resection (n = 133) | Cross-sectional observational | N/A | Assess long-term impairments of HRQOL after meningioma resection in different ages | -SF-36 | -N/A | - Neurosurgery |

| 7 | Zamanipoor, Najafabadi et al | 2021 | Long-term disease burden survivorship issues after surgery and RT of intracranial meningioma patients | (median 9 years) | Quantitative | The Netherlands | Intracranial meningioma patients (n = 190) | Cross-sectional observational | N/A | Assess long-term disease burden in meningioma patients | -SF-36 -HADS -EORTC BN20 -SF-HLQ |

-N/A ->11 -N/A -N/A |

- Neurosurgery (surgery as initial treatment: 88%) - Radiotherapy (radiotherapy as initial treatment: 5%) |

| 23 | Nassiri, price, shehab, Au, Cusimano, Jenkinson, Jungk, Mansouri, Santarius, Suppiah, Teng, Toor, Zadeh, Walbert, Drummond, Internatgional consortium and meningiomas | 2019 | Life after surgical resection of a meningioma: a prospective, cross-sectional study evaluating health-related quality of life | 37 months (first assessment); 47.5 months (all assessments) | Quantitative | Australia | Grade I intracranial meningioma (n = 181) | Longitudinal observational | Normative population | Evaluate possible determinant of changes in global HRQOL | -EORTC QLQ C30 | -90 (functioning domains) -5–10 (symptom domains)24 |

- Neurosurgery |

| 12 | Nassiri, Suppiah, Wang, Badhivala, Juraschua, Meng, Nejad, Au, Willmarth, Cusimana & Zadeh | 2020 | How to live with a meningioma: experiences, symptoms and challenges reported by patients | 3 years (19.4%) 5 years (39.4%) |

Quantitative | Canada | Meningioma patients (83%) (n = 1852) | Cross-sectional observational | N/A | Explore the gaps in care of meningioma patients that would improve quality of care by better understanding | - 19-item self-report questionnaire from American Brain Tumour Association | -N/A | - Neurosurgery (65.5%) - Radiotherapy (28.3%) - Chemotherapy (3.8%) |

| 11 | Najafabadi et al., | 2019 | Unmet needs and recommendations to improve meningioma care through patient, partner and health care provider input: a mixed method study | (median) 66 months | Mixed methods | The Netherlands | Suspected or confirmed Grade I or II meningioma patients (n = 16) | Cross-sectional observational | N/A | Evaluate the current structure and issues faced by meningioma patients | - Semistructured interviews | -N/A | - Neurosurgery: (92%) - Radiotherapy: (25%) |

| 25 | Zamanipoor Najafabadi et al., | 2018 | The disease burden of meningioma patients: long-term results on work productivity and healthcare consumption | (median) 10 years | Quantitative | The Netherlands | Meningioma patients (n = 106) | Cross-sectional observational | N/A | Impact of short and long-term neurological sequalae and HRQOL impairments on work productivity | -SF-HLQ | -N/A | - Neurosurgery |

| 26 | Kangas, Williams, Snee | 2012 | The association between posttraumatic tress and health related quality of life in adults treated for benign meningioma | 4.4 years | Mixed methods | Australia | Meningioma patients previously treated with radiotherapy (n = 70) | Cross-sectional observational | N/A | Objective investigate the incidence of MGM-related PTSS in patients who had been diagnosed and treated for primary benign MGM | -Impact of Event Scale Revised -FACT -Profile of Mood States -Semistructured interviews |

-≥33 -N/A -≥7 -N/A |

-One course of radiation: 60% -Multiple treatments: 40% |

| 27 | Baba, McCradden, Rabski, Cusimano | 2019 | Determining the unmet needs of patients with intracranial meningioma—a qualitative assessment | 10 years | Qualitative | Canada | Patients with intracranial meningioma (n = 50) | Cross-sectional observational | N/A | Determine the unmet needs of patient with intracranial meningioma | -Semistructured interviews | -N/A | - Neurosurgery (96.6%) - Radiotherapy [before surgery: (3.3%); after surgery (20%)] |

| 28 | Pintea, Kandenwein, Lorenzen, Bostrom, Daker, Velazquez, Kristof | 2018 | Factors of influence upon the SF-36 based HRQOL of patients following surgery for petroclival and lateral posterior surface of pyramid meningiomas | 59 months (postoperative) | Quantitative | Germany | Patients operated on for petroclival meningioma or lateral posterior surface of pyramid meningiomas (n = 78) | Cross-sectional observational | “Normal” population means | To describe the patient’s self-assessed HRQOL | -SF-36 | -N/A | - Neurosurgery - Radiotherapy (15%) |

| 29 | Kalascuskas, Kerc, Ajaj van Cube, Ringel, Renovanz | 2020 | Psychological burden in meningioma patients under a wait-and-watch strategy and after complete resection is high results of a prospective single centre study | 39 months | Quantitative | Germany | Meningioma patients under a wait-and-watch strategy or no neurologic deficits after complete resection (n = 62) | Cross-sectional experimental | N/A | Compare the psychosocial situation of meningioma under a wait and watch strategy to those who had undergone complete resections | -Distress Thermometer -HADS -BFI -SF-36 |

-> 3 ->11 -1-3 (mild); 4-7 (moderate) 8-10 (severe) -N/A |

- “Wait-and-watch” strategy - Neurosurgery |

| 18 | Tanti, Marsch, Jenkinson | 2017 | Epilepsy and adverse quality of life in surgically resected meningioma | 3.9 years (median, time since surgery) | Quantitative | United Kingdom | Patients who had undergone surgical resection for supratentorial WHO grade I meningioma (n = 229) | Cross-sectional observational | N/A | Comparing HRQOL between MGM patients with and without epilepsy and between epilepsy patients with/without | -FACT-BR -LAEP |

->7 ->45 of total LAEP score or > 8 of the number of severe LAEP items |

- Neurosurgery |

| 14 | Kalkanis, Quinones-Hinojosa, Buzney, Ribaudo, Blac | 2000 | Quality of life following surgery for intracranial meningiomas at Brigham and Women’s Hospital: a study of 164 patients using a modification of the functional assessment of cancer therapy-brain questionnaire | 33 months (mean), 28 months (median) | Qualitative | United States | Patients who had undergone craniotomy for resection of an intracranial meningioma (n = 155) | Cross-sectional observational | N/A | Determine the reported QOL of patient with meningioma that had been surgically treated | Standardized QOL questions modified from the FACT-BR | ->7 | - Neurosurgery |

| 30 | Zamanipoor Najafabadi, van der Meer, Boele, Reijneveld, Taphoorn, Klein, van Furth, Dirven, Peerdema | 2018 | The long-term disease burden of meningioma patients: results on health-related quality of life, cognitive function, anxiety and depression | 9.9 years (median) | Quantitative | The Netherlands | Intracranial meningioma patients after antitumor therapy (n = 164) | Multicenter cross-sectional observational | Newly diagnosed glioblastoma patients | Assess the long-term disease burden of meningioma patients | -SF-36 -EORTC QLQ BN20 -HADS |

-N/A -N/A ->11 |

- Neurosurgery: 89.2%, radiotherapy: 14.6% |

| 15 | Pettersson-Segerlind, Fletcher-Sandersjoo, von Vogelsang, Peresson, Kihlstrom, Linder, Forander, Mathiesen, Edstrom, Elmi-Terander | 2022 | Long-Term Follow-Up, Treatment Strategies, Functional Outcome, and Health-Related Quality of Life after Surgery for WHO Grade 2 and 3 Intracranial Meningiomas | 13 years (grade II) 1.4 years (grade III) |

Mixed methods | Sweden | WHO Grade 2 and 3 meningioma patients surgically treated (n = 51 [12–13 patients for the HRQOL measures]; 43 Grade 2, 8, Grade 3) | Population-based, observational, cross-sectional cohort study | N/A | Determine the HRQOL of long-term progression-free survival and overall survival for WHO Grade 2 and 3 intracranial meningiomas | -EQ-5D-3L -FACT-BR -HADS, structured interviews |

• GAD-2: >3 • PHQ-9: > 10 (mild); >15 (moderate to severe) -> 7 -> 11 |

- Neurosurgery |

| 31 | Pettersson-Segerlind, von Vogelsang, Fletcher Sandersjoo, Tatter, Mathiesen, Edstrom, Elmi Terander | 2021 | Health-Related Quality of Life and Return to Work after Surgery for Spinal Meningioma: A Population-Based Cohort Study | 8.7 years (mean) | Quantitative | Sweden | Spinal meningioma surgically treated (n = 84) | Population-based observational cohort study | General population | Assess the HRQOL and the frequency of return to work in patients surgically treated for spinal meningiomas compared to the general population | -EQ-5D-3DL | -GAD-2: >3 -PHQ-9: > 10 (mild); >15 (moderate to severe) |

- Neurosurgery |

| 17 | Fisher, Najafabadi, van der Meer, Boele, Peerdeman, Peul, Taphoorn, Dirven, van Furth | 2022 | Long-term health-related quality of life and neurocognitive functioning after treatment in skull base meningioma patients | 9 years (median) | Quantitative | The Netherlands | Skull base meningioma (n = 89) | Cross-sectional | Convexity meningioma patients and informal caregivers of skull base meningioma patients | Assess the long-term HRQOL and neurocognitive functioning after treatment in the long term | -SF-36, -EORTC QLQ-BN20 |

-N/A -N/A |

- Radiotherapy vs. neurosurgery |

Abbreviations: BFI, Brief Fatigue Inventory; EORTC QLQ-C30, European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality-of-Life Questionnaire Core 30; EORTC BN20, European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer BN20 Brain Tumour module; EQ-5D-3L, 3-level version of EQ-5D; FACT, Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy; FACT-BR, Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Brain; GAD-2, Generalized Anxiety Disorder-2; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression scale; HRQOL, health-related quality of life; LAEP, Liverpool Adverse Events Profile; N/A, not applicable; PHQ, Patient Health Questionnaire; SF-36, Short Form-36; SF-HLQ,Short Form—Health and Labour Questionnaire; WHO, World Health Organization.

Health-Related Quality of Life

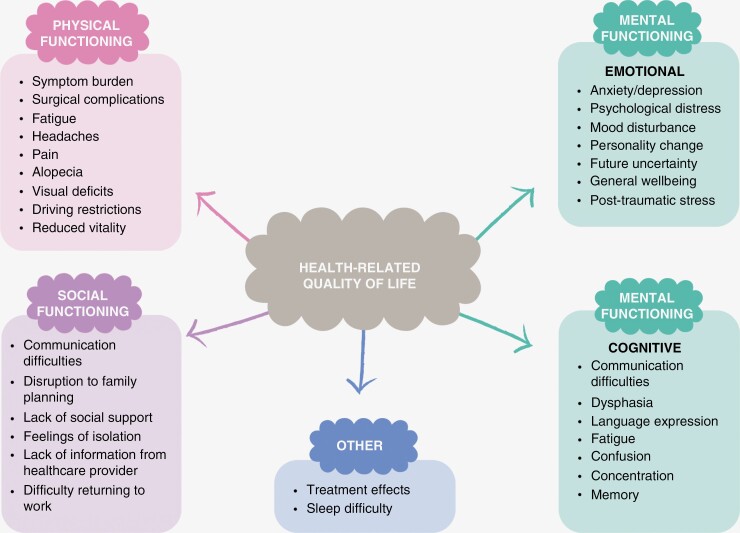

Figure 2 shows key findings related to the physical, emotional, and social domains of HRQOL, with results covered in more detail below.

Figure 2.

Narrative synthesis, domains, and key findings.

Physical functioning.—

Meningioma patients reported negative impacts on their physical capability and increased symptom burden.7,11,16,17,20–23,26,30 A variety of symptoms were reported,7,11,17,23 for example, headaches,26 fatigue,12,17,18,23 increased levels of pain,22 epilepsy,7,12–14,16–18 and alopecia.16,17 Grade I meningioma patients with epilepsy (N = 56) had worse HRQOL as measured with the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Brain (FACT-BR) summary score compared to meningioma patients without seizures (N = 109).18 A cross-sectional observational study found that patients with grade I meningioma (N = 181) scored worse than general population controls on overall measures of physical functioning, yet 86% of patients did return to presurgery levels of physical functioning, independence, and ability to drive.23 Reduced physical functioning appeared associated with radiotherapy treatment in 1 study comparing 18 patients who were irradiated to 18 patients who were not.21 Yet, in a study of 507 skull base meningioma patients treated with high-precision photon radiotherapy, 56% had validly completed patient-reported outcomes data which showed no major detriment of radiotherapy treatment, with only 4.2% rating their HRQOL as worse following radiotherapy.16 Furthermore, 47.7% of patients in this study reported stable HRQOL after radiotherapy, and 37.5% reported improvement during follow-up.16 Other determinants for worse physical functioning outcomes found in a large meningioma patient cohort (N = 190) were female sex, comorbidities, larger tumor size, lower level of education, and lower Karnofsky Performance Score at the time of the study.20 In a secondary analysis that compared subgroups of 89 skull base meningioma patients to 84 convexity meningioma patients and 65 caregiver controls, no statistically significant differences in physical functioning were found between groups.17

Mental functioning

Psychological/Emotional Functioning

Psychological and emotional experiences of meningioma patients were reported in many studies, using a variety of outcome measures (see Table 1).7,13,18,19,23,29 Elevated psychological distress,7,13,15,30 anxiety, and depression,7,13,15,29–31 as well as a number of general “emotional problems” including low scores on emotional (role) functioning scales of HRQOL outcomes were reported.13,14,22,23,30,31 Estimates of the prevalence of anxiety varied between 14%–50%, and between 7%–87% for depression, depending on the timing of assessment and outcome measure used.7,13,15,29–31 There were also reports of more specific psychological difficulties, with a cross-sectional observational study showing 11 out of 70 participants (16%) experienced elevated meningioma-related post-traumatic distress. In this small sample, higher post-traumatic stress symptoms were related to mood disturbances and higher support needs, as well as reduced scores on physical, emotional, and functional well-being aspects of HRQOL (as measured with the FACT) compared to patients with low post-traumatic stress symptoms.26 Cognitive complaints and epilepsy have also been linked to worse emotional well-being.13 Benefit finding, a psychological change that can arise in response to a traumatic event, was found to be associated to higher levels of depressive symptoms in meningioma patients <2 years after diagnosis (N = 27), whereas higher benefit finding was associated with intrusions and avoidance symptoms in longer-term survivors (N = 43).19 The study authors explain this as an evolving strategy meningioma patients may use to cope with the future uncertainty of tumor recurrence as time goes on.19

Treatment strategies might contribute to mental difficulties. In a study of 62 meningioma patients, those who were followed with a wait-and-watch strategy (N = 31) had a 4.26-fold higher risk of depression than those who received surgical resection (N = 31); yet a worse score on the observer-completed Neurologic Assessment in Neuro-Oncology scale was associated with a lower risk of depressive symptoms, underscoring the importance of patient self-report.29 Yet, in an investigation comparing 18 surgery-only patients at 3 years post-treatment to 18 patients treated with surgery and radiotherapy at 7.6 years post-treatment, no differences in emotional functioning between treatment groups were found.21

Self-Reported Cognitive Functioning

Several studies made mention of subjective cognitive complaints.7,11–13,18,29 In a study of 136 meningioma patients on average 32 months after surgery, 23% reported subjective cognitive complaints using the cognitive failures questionnaire—however, patients scored better than would be expected of the general population.13 Higher degrees of cognitive complaints have also been reported—in another investigation of 1542 meningioma patients of whom 58.8% were long-term survivors (>3 years post-diagnosis), 42.3% of patients reported cognitive issues. Cognitive complaints covered in included studies were vision and communication impairments7,17 concentration issues,26,29 changes in personality,26 difficulties with language expression,13 and confusion.18 Cognitive issues such as impaired concentration, being slower, and difficulty making decisions have been linked to patients’ difficulties in everyday life including work.7,13

Social functioning.—

Patients can face disruptions to their social functioning,7,11,12,23 impacting on their overall HRQOL.23 Social functioning may be linked to cognitive complaints such as communication difficulties,7,17 impacting the relationship with peers and loved ones. In conjunction with concentration issues and personality changes, meningioma patients with higher post-traumatic stress symptoms (N = 11) were more bothered by a decline in what they could contribute to family, compared to meningioma patients who had lower post-traumatic stress symptoms (N = 59).26 In a small cross-sectional study, while social functioning scores did not differ between groups, those meningioma patients who received radiotherapy (N = 18) had worse role limitations due to physical problems than those who did not receive radiotherapy (N = 18), although differences did not hold after correction for duration of disease.21 In a qualitative investigation of 30 patients, seizure-related driving restrictions were found to impact on psychological as well as social well-being, with the ability to drive strongly linked to a sense of independence and freedom.27

Patients described receiving support from family, partner/caregivers, and friends, as well as through the internet or message boards designed for brain tumor patients.12,26 However, a lack of support is also described, with a mixed-methods cross-sectional study reporting that meningioma patients and their family caregivers have missed support with reintegration into society, psychosocial aftercare, and care for partners.11 In 11 meningioma patients with elevated post-traumatic stress symptoms, many reported unmet support needs related to distress (82%) and fear of tumor recurrence (91%).26 Feelings of isolation, occurring in 22% of a large sample of long-term meningioma survivors (N = 190, ≥5 years after intervention), were identified as impacting on work productivity.7 Meningioma patients of working age were less likely to have a paid job (48%) compared to the general population (72%).7

Treatment impact on HRQOL.—

Studies included patients who had undergone active treatment for meningioma, as well as those who remained under surveillance post-diagnosis. Surgical complications, radiotherapy, and re-operation notably contributed to long-term disease burden,7 although not consistently.17 Long-term HRQOL outcomes did not seem related to multiple surgical treatments or presence/absence of postoperative complications in a sample of N = 89 patients with skull base meningioma.17

There are indications that those receiving multimodal treatment (surgery and radiotherapy) suffer worse HRQOL outcomes than those who only receive surgery.21 However, this difference may be explained by other sociodemographic and clinical factors: a study found negative HRQOL scores to be associated with younger age at surgery14; another found worse effects of meningioma patients who received radiotherapy (N = 18) compared to those who did not receive radiotherapy (N = 18), which disappeared after correction for TSD.21 A median of 9 years after treatment, HRQOL scores (pain, vitality) were lower in skull-base meningioma patients who received radiotherapy as the primary treatment (N = 6), compared to those whose primary treatment was surgery (N = 63).17 The impact of radiotherapy on HRQOL is also unclear in a study of 340 meningioma patients who completed a study-specific HRQOL measure (67% of the total sample), with 47% reporting stable HRQOL and 37% reporting improvement in HRQOL following radiotherapy.16

Discussion

In this systematic review of 21 publications from 16 studies, we organized issues faced by long-term survivors of meningioma in line with the physical, mental, and social domains of HRQOL.6 We found that impaired physical functioning was commonly reported, with symptom burden impacting on functioning into long-term survival. This is in line with a previous systematic review, which did not specifically focus on long-term survivorship, and found that meningioma patients reported worse physical functioning compared to healthy controls, but better compared to glioma populations.2 Yet, in our previous systematic review of long-term HRQOL outcomes in patients with WHO grade II or III glioma, we found similar symptom complaints and physical impairments.32

Our review highlights the numerous reports of mental impairments of HRQOL. Despite the good prognosis, the emotional burden placed on patients at diagnosis is life changing and persists across long-term survival. Prevalence of anxiety and depressive symptoms ranged between 14%–50% and 7%–87%, respectively7,13,15,29–31—depending on timing of assessment, outcome measure used, and cutoff employed. Previous studies highlight that prior to formal diagnosis of meningioma, mental health seems to be affected—and may in fact be a presenting neurologic sign.33,34 Prescription of antiepileptic drugs, antidepressants, and sedatives was comparable to controls 2 years before surgery for meningioma (N = 2070), yet is higher in meningioma patients from the point of diagnosis up to 2 years post-surgery.35 Our review highlights that mental health issues do not seem to resolve over time, with emotional well-being impacted even years after diagnosis.

As this review focused on patient self-report measures, we reported on subjective cognitive complaints rather than results from objective cognitive assessment—which is known to be impaired with approximately 80% of studies finding evidence of cognitive impairment in meningioma patients up to a year after treatment.36 Cognitive complaints as reported by patients may reflect better the impact of cognitive impairment on everyday life in longer-term survivorship, as experienced by patients, as over time patients may adopt compensatory strategies and/or undergo neurorehabilitation. Importantly, in this review, we did not focus on family caregiver reports, which can substantially differ from patient self-reports, especially when cognitive impairment results in reduced self-awareness of functioning.37 Still, patients self-reported that changes in personality/behavior, difficulties with communication, concentration, processing speed, and decision-making abilities impact their everyday life. This appeared linked to social functioning, including feelings of isolation and employment issues. This is in keeping with the results of our review in long-term survivors of WHO grade II/III glioma patients,32 suggesting that despite the relatively favorable prognosis, meningioma patients still feel a substantial disease burden affecting their ability to function in social settings.

The extent to which treatment contributes to HRQOL outcomes in meningioma patients in the long term remains uncertain. While a more aggressive treatment strategy, including the use of multimodal treatment, seems linked to worse HRQOL outcomes, it is important to consider that treatment strategies align with expected tumor behavior and feasibility of antitumor treatment depending on, for example, tumor location. In the interpretation of long-term survivorship studies, it is crucial to take into account that treatments do evolve over time, with potentially, fewer or less severe late effects associated with newer treatment regimens. Regardless of treatment, it is reasonable to expect that more aggressive meningiomas and/or those associated with genetic syndromes might lead to higher symptom burden and worse HRQOL. Of note, studies included in this review did not consistently report on seizures or use of antiepileptic drugs, which tends to be associated with HRQOL.2 The relationship between treatment and HRQOL remains complex and requires further investigation—ideally from prospective, longitudinal studies, such as the ROAM trial (Radiation versus Observation following surgical resection of Atypical Meningioma; EORTC1308-ROG-BTG).38

This systematic review holds strengths in its focus on long-term survival and HRQOL outcomes as assessed through patient self-report—ensuring findings reflect direct perspectives of meningioma patients. Including mixed-methodology studies allowed us to identify themes across the quantitative and qualitative findings. Limitations include that evidence to date largely stems from cross-sectional studies; large differences in sample sizes within studies; overrepresentation of some unique study participants due to multiple reports from 16 unique studies; the difficulty in linking clinical/treatment factors to HRQOL aspects; and limited opportunities for cross-study comparisons due to the variety of outcome measures and cutoff scores reported on. Furthermore, patients may have experienced other substantial life stressors contributing to HRQOL impairment throughout the extended period of survivorship, outside of tumor and treatment-related factors. Finally, meningioma is not always accompanied by a major symptom burden and can go undetected until cerebral imaging is performed for other reasons; hence, patients who take part in research studies may not be representative of the population of patients with meningioma per se. To some extent, these limitations impact on drawing of clinically relevant conclusions. Yet, this investigation clearly highlights that even years after diagnosis and treatment, meningioma patients can experience substantial physical, mental, and social HRQOL impacts. Greater recognition of long-term HRQOL and disease burden associated with meningioma could aid access to, or development of, support services.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The literature searches for this project were designed with expert input from Judy Wright, Senior Information Specialist, University of Leeds.

Contributor Information

Sé Maria Frances, Patient-Centred Outcomes Research, Leeds Institute of Medical Research at St James’s, St James’s University Hospital, University of Leeds, Leeds, UK.

Louise Murray, Department of Clinical Oncology, Leeds Cancer Centre, Leeds Institute of Medical Research at St James’s, University of Leeds, Leeds, UK.

Emma Nicklin, Patient-Centred Outcomes Research, Leeds Institute of Medical Research at St James’s, St James’s University Hospital, University of Leeds, Leeds, UK.

Galina Velikova, Patient-Centred Outcomes Research, Leeds Institute of Medical Research at St James’s, St James’s University Hospital, University of Leeds, Leeds, UK; Department of Clinical Oncology, Leeds Cancer Centre, Leeds Institute of Medical Research at St James’s, University of Leeds, Leeds, UK.

Florien Boele, Patient-Centred Outcomes Research, Leeds Institute of Medical Research at St James’s, St James’s University Hospital, University of Leeds, Leeds, UK; Academic Unit of Health Economics, Leeds Institute of Health Sciences, University of Leeds, Leeds, UK.

Funding

None declared.

Conflict of interest statement

Galina Velikova—Personal fees from Roche, Eisai, Novartis, Seattle Genetics. Grants from: Breast Cancer Now, EORTC, YCR, Pfizer, IQVIA. Remaining authors had no conflicts of interest.

Authorship statement

Conceptualization: S.M.F., L.M., G.V., and F.B. Methodology: S.M.F., E.N., and F.B. Investigation: S.M.F., E.N., and F.B. Writing (original draft): S.M.F. Writing (review & editing): S.M.F., L.M., E.N., G.V., and F.B. Resources: F.B.

References

- 1. Macmillan Cancer Support. 2023. Meningioma. Available at: https://www.macmillan.org.uk/cancer-information-and-support/brain-tumour/meningioma

- 2. Zamanipoor Najafabadi AH, Peeters MC, Dirven L, et al. Impaired health-related quality of life in meningioma patients—a systematic review. Neuro-Oncol. 2017;19(7):897–907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Haider S, Taphoorn MJB, Drummond KJ, Walbert T.. Health-related quality of life in meningioma. Neuro-Oncol Adv. 2021;3(1):vdab089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Li JT, Bian K, Zhang AL, et al. Targeting different types of human meningioma and glioma cells using a novel adenoviral vector expressing GFP-TRAIL fusion protein from hTERT promoter. Cancer Cell Int. 2011;11(1):1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dijkstra M, Van Nieuwenhuizen D, Stalpers LJA, et al. Late neurocognitive sequelae in patients with WHO grade I meningioma. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2009;80(8):910–915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Stenman U, Hakama M, Knekt P, et al. Measurement and modeling of health-related quality of life. Epidem Demog Public Health. 2010;195(1):130–135. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zamanipoor Najafabadi AH, van der Meer PB, Boele FW, et al. Long-term disease burden and survivorship issues after surgery and radiotherapy of intracranial meningioma patients. Neurosurgery. 2021;89(1):S69–S69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Int Surg J. 2021;88:105906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hong QN, Fàbregues S, Bartlett G, et al. The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. Educ Inf. 2018;34(4):285–291. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A, et al. Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews. A product from the ESRC methods programme Version. 2006;1(1):b92. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zamanipoor Najafabadi AH, van de Mortel JP, Lobatto DJ, et al. Unmet needs and recommendations to improve meningioma care through patient, partner, and health care provider input: a mixed-method study. Neuro-Oncol Pract. 2020;7(2):239–248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nassiri F, Suppiah S, Wang JZ, et al. How to live with a meningioma: experiences, symptoms, and challenges reported by patients. Neuro-Oncol Adv. 2020;2(1):vdaa086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. van der Vossen S, Schepers VP, van der Sprenkel JWB, Visser-Meily JM, Post MW.. Cognitive and emotional problems in patients after cerebral meningioma surgery. J Rehabil Med. 2014;46(5):430–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kalkanis SN, Quiñones-Hinojosa A, Buzney E, Ribaudo HJ, Black PM.. Quality of life following surgery for intracranial meningiomas at Brigham and Women’s Hospital: a study of 164 patients using a modification of the functional assessment of cancer therapy–brain questionnaire. J Neurooncol. 2000;48(3):233–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pettersson-Segerlind J, Fletcher-Sandersjöö A, von Vogelsang A-C, et al. Long-term follow-up, treatment strategies, functional outcome, and health-related quality of life after surgery for WHO grade 2 and 3 intracranial meningiomas. Cancers. 2022;14(20):5038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Combs SE, Adeberg S, Dittmar J-O, et al. Skull base meningiomas: long-term results and patient self-reported outcome in 507 patients treated with fractionated stereotactic radiotherapy (FSRT) or intensity modulated radiotherapy (IMRT). Radiother Oncol. 2013;106(2):186–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Fisher FL, Najafabadi AHZ, van der Meer PB, et al. Long-term health-related quality of life and neurocognitive functioning after treatment in skull base meningioma patients. J Neurosurg. 2021;136(4):1077–1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tanti MJ, Marson AG, Jenkinson MD.. Epilepsy and adverse quality of life in surgically resected meningioma. Acta Neurol Scand. 2017;136(3):246–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kangas M, Williams JR, Smee RI.. Benefit finding in adults treated for benign meningioma brain tumours: relations with psychosocial wellbeing. Brain Impairment. 2011;12(2):105–116. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zamanipoor Najafabadi AH, van der Meer PB, Boele FW, et al. ; Dutch Meningioma Consortium. Determinants and predictors for the long-term disease burden of intracranial meningioma patients. J Neurooncol. 2021;151:201–210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. van Nieuwenhuizen D, Klein M, Stalpers LJ, et al. Differential effect of surgery and radiotherapy on neurocognitive functioning and health-related quality of life in WHO grade I meningioma patients. J Neurooncol. 2007;84(3):271–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Timmer M, Seibl-Leven M, Wittenstein K, et al. Long-term outcome and health-related quality of life of elderly patients after meningioma surgery. World Neurosurg. 2019;125:e697–e710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Nassiri F, Price B, Shehab A, et al. ; International Consortium on Meningiomas. Life after surgical resection of a meningioma: a prospective cross-sectional study evaluating health-related quality of life. Neuro-Oncol. 2019;21(suppl. 1):i32–i43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jansen F, Snyder CF, Leemans CR, Verdonck-de Leeuw IM.. Identifying cutoff scores for the EORTC QLQ-C30 and the head and neck cancer-specific module EORTC QLQ-H&N35 representing unmet supportive care needs in patients with head and neck cancer. Head Neck. 2016;38(Suppl. 1):E1493–E1500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zamanipoor Najafabadi AZ, van der Meer P, Boele F, et al. P05. 64 The disease burden of meningioma patients: long-term results on work productivity and healthcare consumption [abstract]. Neuro-Oncol. 2018;20(Suppl. 6):vi154. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kangas M, Williams JR, Smee RI.. The association between post-traumatic stress and health-related quality of life in adults treated for a benign meningioma. Appl Res Qual Life. 2012;7:163–182. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Baba A, McCradden MD, Rabski J, Cusimano MD.. Determining the unmet needs of patients with intracranial meningioma—a qualitative assessment. Neuro-Oncol Pract. 2020;7(2):228–238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Pintea B, Kandenwein J, Lorenzen H, et al. Factors of influence upon the SF-36-based health related quality of life of patients following surgery for petroclival and lateral posterior surface of pyramid meningiomas. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2018;166:36–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kalasauskas D, Keric N, Abu Ajaj S, et al. Psychological burden in meningioma patients under a wait-and-watch strategy and after complete resection is high—results of a prospective single center study. Cancers. 2020;12(12):3503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zamanipoor Najafabadi A, van der Meer P, Boele F, et al. MNGI-27. The long-term disease burden of meningioma patients: results on health-related quality of life, cognitive function, anxiety and depression [abstract]. Neuro-Oncol. 2018;20(suppl. 3):vi154–vi155. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Pettersson-Segerlind J, von Vogelsang A-C, Fletcher-Sandersjöö A, et al. Health-Related quality of life and return to work after surgery for spinal meningioma: a population-based cohort study. Cancers. 2021;13(24):6371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Frances SM, Velikova G, Klein M, et al. Long-term impact of adult WHO grade II or III gliomas on health-related quality of life: a systematic review. Neuro-Oncol. Pract. 2022;9(1):3–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kessler RA, Loewenstern J, Kohli K, Shrivastava RK.. Is psychiatric depression a presenting neurologic sign of meningioma? A critical review of the literature with causative etiology. World Neurosurg. 2018;112:64–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Maurer R, Daggubati L, Ba DM, et al. Mental health disorders in patients with untreated meningiomas: an observational cohort study using the nationwide MarketScan database. Neuro-Oncol Pract. 2020;7(5):507–513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Thurin E, Rydén I, Skoglund T, et al. Impact of meningioma surgery on use of antiepileptic, antidepressant, and sedative drugs: a Swedish nationwide matched cohort study. Cancer Med. 2021;10(9):2967–2977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gondar R, Patet G, Schaller K, Meling TR.. Meningiomas and cognitive impairment after treatment: a systematic and narrative review. Cancers. 2021;13(8):1846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Oort Q, Dirven L, Sikkes SA, et al. Do neurocognitive impairments explain the differences between brain tumor patients and their proxies when assessing the patient’s IADL? Neuro-Oncol Pract. 2022;9(4):271–283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Jenkinson MD, Javadpour M, Haylock BJ, et al. The ROAM/EORTC-1308 trial: radiation versus observation following surgical resection of atypical meningioma: study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2015;16(1):1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.