Abstract

Background

There have been documented racial and ethnic disparities in the care and clinical outcomes of patients with thyroid disease.

Context

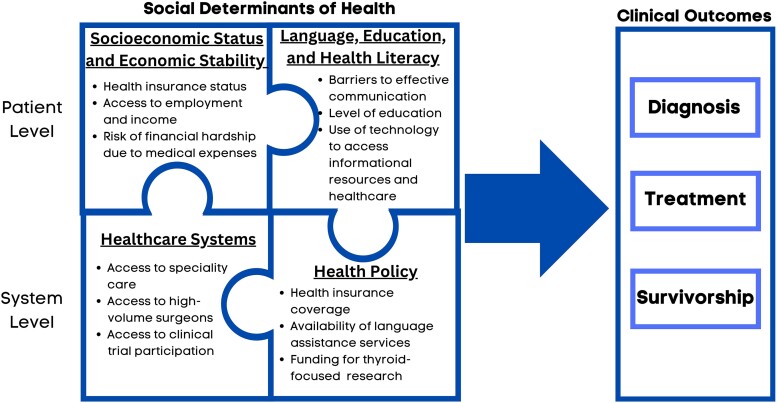

Key to improving disparities in thyroid care is understanding the context for racial and ethnic disparities, which includes acknowledging and addressing social determinants of health. Thyroid disease diagnosis, treatment, and survivorship care are impacted by patient- and system-level factors, including socioeconomic status and economic stability, language, education, health literacy, and health care systems and health policy. The relationship between these factors and downstream clinical outcomes is intricate and complex, underscoring the need for a multifaceted approach to mitigate these disparities.

Conclusion

Understanding the factors that contribute to disparities in thyroid disease is critically important. There is a need for future targeted and multilevel interventions to address these disparities, while considering societal, health care, clinician, and patient perspectives.

Keywords: disparities, race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, thyroid, thyroid cancer

Thyroid conditions, encompassing both benign and malignant diseases, are highly prevalent and affect individuals from diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds. Prior work has highlighted disparities in the care and clinical outcomes of patients with thyroid disease (1-3). These existing racial and ethnic disparities raise concerns about equitable access to quality health care and call for a closer examination of the driving factors (1-5).

Disparities in health care, including disparities in the care of patients with thyroid disease, are primarily rooted in societal and structural factors, rather than inherent biological differences (4-6). A deeper exploration of racial and ethnic disparities in thyroid disease care includes a better understanding of the critical roles of health equity, social determinants of health, and structural racism. Health equity defines a state in which every individual has a fair opportunity to achieve their full health potential and overall well-being (4-6). Key to recognizing the existing obstacles to health equity is considering social determinants of health, which encompass the living conditions, learning environments, workplaces, recreational opportunities, places of worship, and aging experiences that influence an individual’s health outcomes and risks (4-6). In this context, the concept of systemic and structural racism becomes particularly significant. It denotes the ways in which society fosters racial and ethnic inequity by differentially distributing social determinants of health and resources among various racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic groups (4-6).

To provide context for the well described disparities in the care of patients with thyroid disease, this perspective focuses on the critical role of social determinants of health. Figure 1 provides an overview and illustrates how social determinants of health, both at the patient and the system-level, impact thyroid disease diagnosis, treatment, and survivorship.

Figure 1.

Clinical outcomes for patients with thyroid disease are influenced by social determinants of health.

Patient-Level Factors

Patient-level factors that influence clinical outcomes include socioeconomic status and economic stability, language, education, and health literacy.

Socioeconomic Status and Economic Stability

Important factors associated with access to health care include economic stability, employment opportunities, and insurance coverage (7). Economic stability correlates with access to employment and income, subsequently influencing access to other crucial social determinants of health, including education, health insurance, and high-quality health care (4, 5). International studies suggest that the quality of care for patients with thyroid cancer is notably superior in countries with higher socioeconomic status, primarily owing to improved access to health care (8). Similarly, studies from the United States have emphasized the importance of patient's health insurance status, risk of financial hardship, and ability to take time off work (9, 10).

Collins et al, evaluated the relationship between social determinants of health, time to treatment, and mortality in patients with thyroid cancer, particularly across different racial and ethnic groups. In their analysis, encompassing 142 024 patients drawn from the National Cancer Database spanning the years 2004-2017, the cumulative presence of adverse social determinants of health, such as lack of insurance, low educational attainment, and low income, was associated with prolonged time to treatment, which, in turn, was associated with elevated mortality rates (7). When stratified by race, each adverse social determinant of health exerted a significant influence on extended time to treatment for Black and Hispanic patients (7).

In a study of 125 827 patients affiliated with the National Cancer Database and diagnosed with differentiated thyroid cancer from 2016 to 2019, the influence of insurance status (private, Medicare, Medicaid) on timeliness and adherence to the 2015 American Thyroid Association thyroid cancer guidelines was evaluated. The study revealed that 72% of the participants received appropriate surgical and radioactive iodine therapy. However, patients with Medicaid coverage exhibited lower likelihoods of undergoing appropriate surgical treatment and surgery within 90 days of diagnosis, while also showing a higher probability of undertreatment with radioactive iodine (9).

Additionally, in a study of patients with hypothyroidism, using the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey data from 2012 to 2017, authors found that access to care was associated with higher likelihood of receiving thyroid hormone treatment, with Hispanic patients more likely to have inadequate treatment for hypothyroidism, after adjusting for gender, age, education level, income, and access to care (11). In the context of thyrotoxicosis, an analysis of 374 patients in a safety net hospital revealed significant disparities associated with the risk for admission. Patients without health insurance had a significantly higher risk of hospital admission due to complicated thyrotoxicosis (12 times higher odds), while those with higher median income had a lower risk (63% lower) (12).

A crucial aspect of economic stability and health care is the significant financial burden linked to medical expenses (13). This financial strain can affect how well patients with thyroid disease adhere to treatment, the results of their treatment, and their overall quality of life (13). Considerable variability exists in estimating out of pocket medical costs for patients diagnosed with thyroid cancer, with figures ranging from $1425 to as high as $17 000 (13). This variability appears to be particularly pronounced among individuals of younger age, those necessitating more extensive surgical interventions, and those lacking health insurance coverage (13). Patients from various racial and ethnic backgrounds, as well as those with varying social determinants of health, may encounter distinct financial burdens in their health care experiences. For instance, in a group of 273 Hispanic women diagnosed with thyroid cancer, 47% reported experiencing some degree of financial hardship (10). Among these individuals, 38% had to utilize their savings, 25% resorted to reducing food expenses, and 18% found themselves unable to meet their monthly financial obligations (10). Notably, this study identified annual household income and younger age as significant factors associated with financial hardship.

Language, Education, and Health Literacy

In addition to socioeconomic status, patients’ preferred language, level of education, and health literacy impact the care that they receive. It is well documented that language discordance between patients and the health care team negatively impacts the quality of patient care (14). However, even with the use of language interpreters, there may still be limitations to effective communication. In an analysis of audio recordings from 34 nonthyroid cancer clinic visits, Bregio et al concluded that ad hoc language interpreters (ie, bilingual family members or staff not formally trained in interpretation) were ineffective mediators of communication, and consistently conveyed fewer statements than professional interpreters (15). Disappointingly, in a different study that analyzed recordings from 55 primary care visits in which professional interpretation services were used, Roter et al found that patients and clinicians expressed 1.7 and 2.3 times more statements, respectively, than were conveyed by the professional interpreter (16). It is likely that linguistic barriers contribute, in part, to the disparities in thyroid care experienced by Hispanic and Asian patients (1, 3), two racial/ethnic groups with the highest rates of limited English proficiency in the United States (35%) (17).

Patients’ level of education also has potential to impact their perceptions and treatment of their thyroid disease. Among patients with low-risk thyroid cancer, studies have found that lower education was associated with more thyroid cancer–related worry (18), and was also associated with patients overestimating their risk of thyroid cancer recurrence and mortality (19).

In today's digital world, patients’ level of education and health literacy impacts patients’ experience seeking thyroid-related information and accessing thyroid care. Studies examining the quality of online patient information focused on hypothyroidism, hyperthyroidism, thyroid nodules, and thyroid cancer found that most of these online resources are written above the eighth grade reading level, which is the recommended reading level for health-related information (20-22). In a national survey of health literacy in the United States, Hispanic adults and older adults were found to have lower health literacy relative to other racial/ethnic groups and younger adults, respectively (23). Thus, it is likely that both patient populations are at a disadvantage when seeking thyroid information resources. Similarly, in a survey of information needs among Hispanic women with thyroid cancer, Chen et al found that low-acculturated Hispanic women and older patients were more likely to report no internet access (24). In the context of patients’ increasing use of the electronic patient portal to communicate with their physician (25), limited English proficiency, lower health literacy, and lack of internet access among vulnerable patient populations exacerbate existing disparities in thyroid care delivery (26, 27).

System-Level Factors

System-level factors that influence clinical outcomes include the health care system itself, in addition to health policy.

Health Care Systems

Health care systems are pivotal settings for prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of diseases (4). Disparities in health care, more specifically, health care inequities, pertain to disparities that are both formed and sustained within these health care systems (4). Health care systems influence access to specialty care, high-volume physicians, and clinical trials.

In the context of caring for patients with thyroid disease, it is critically important to ensure access to health care professionals who possess the necessary expertise for accurate diagnosis and treatment, and who approach patients with cultural sensitivity and actively involve them in decision-making (1, 2). However, health care access is complex and is influenced by the patient's perceptions and their ability to seek, reach, afford and actively engage with health care services. Health inequities can result from various factors, both internal (eg, patient–clinician relationship) and external (eg, access to reliable transportation) to the health care setting (4).

A substantial body of evidence has examined the impact of surgical expertise on the outcome of patients with benign and malignant disease (1, 2). Access to high-volume surgeons and specialized surgical centers is associated with reduced risk of postoperative complications and enhanced clinical outcomes among patients with benign and malignant thyroid diseases (1, 2). Notably, the majority of thyroid surgeries are carried out by low-volume surgeons and insurance status, lower income, race/ethnicity (specifically Hispanic ethnicity and Black race), and geographical location significantly affects the likelihood of patients being treated by these low-volume surgeons (1, 2, 28). However, further highlighting the complex interactions of social determinants of health on surgical care disparities, in a study of 106 314 patients who underwent thyroid and parathyroid surgeries, clinical outcomes for Black patients remained suboptimal even when under the care of high-volume surgeons (29).

In addition to access to specialty care and high-volume surgeons, equal opportunity to participate in clinical trials is an important consideration for health care systems focused on health equity (30). Despite the high incidence and substantial impact of thyroid cancer on non-White populations, the inclusion of participants from these groups in clinical trials is noticeably limited (1, 2, 30). For instance, in a review of clinical trials focused on systemic therapies for advanced thyroid cancer, the proportion of subgroups aside from non-Hispanic White were limited, with 4% to 44% for Asian patients, 0% to 3% for Black patients, and 0% to 1% for Hispanic patients (30). The underrepresentation of certain populations in clinical trials can be attributed to several factors, including financial constraints, the absence of research infrastructure and collaborative efforts between academic centers and community practices, as well as language barriers (30).

Health Policy

Health policy and federal funding significantly influence patients’ access to and health care systems’ delivery of thyroid care in the United States. This was prominently observed with the implementation of the Affordable Care Act in 2014, which expanded health insurance coverage for more than 35 million Americans (31). Using Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results and United States Census data, Ullmann et al illustrated a significant inverse correlation between the percentage of 18-64 years old who were uninsured in each state and the state by state incidence of all thyroid cancers (32). A few years later, a retrospective study of 241 448 adults diagnosed with thyroid cancer between 2010 and 2016 found that Medicaid expansion under the Affordable Care Act was associated with a significant increase in the percentage of Medicaid patients undergoing surgery for thyroid cancer, and an increase in Medicaid patients undergoing surgery at the highest-volume hospitals in expansion state hospitals (33).

Conversely, inconsistent implementation of Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 has led to significant system-level barriers that reduce the ability of limited English proficient patients with thyroid disease from accessing and fully participating in their care (34). In the context of the more than 25 million individuals with limited English proficiency in the United States, Title VI has been interpreted to be a requirement that federally funded health care systems and hospitals provide limited English–proficient patients with meaningful access to language assistance services (35). Unfortunately, the availability and use of language services for clinical services in hospitals nationwide have been variable, with 31% of hospitals not offering language services in 2013 (36). Moreover, the inconsistent availability of language services in hospitals likely contributed to the lack of diverse representation in thyroid cancer clinical trials. In a systematic analysis of 14 367 interventional studies registered to ClinicalTrials.gov with at least 1 site in the United States, Muthukumar et al found that 19.0% explicitly included the ability to read, speak, and/or understand English as an eligibility criterion, and only 2.7% specifically mentioned accommodation of translation to another language (37). The inconsistent availability of language services in hospitals disproportionately impacts access to thyroid care, including to thyroid clinical trials.

Despite the high prevalence of benign and malignant thyroid disease on the United States population, disparities exist in federal grant funding for thyroid research, including research focused on examining disparities in thyroid care. In 2023, thyroid cancer is estimated to be the 13th most commonly diagnosed cancer in the United States (38). However, funding for thyroid cancer from the National Cancer Institute has been relatively low compared with other cancer types. In 2018, the National Cancer Institute allocated 13 million dollars to research related to thyroid cancer. These funds were significantly less than that allocated to prostate cancer (239 million dollars; the 12th most common cancer in 2023), lung cancer (350 million dollars; the eighth most common cancer in 2023), and breast cancer (574 million dollars; the second most common cancer in 2023) (39). In the setting of renewed interest in understanding disparities in thyroid care and new developments in thyroid cancer management, it is critically important that more federal funds be allocated to support research focused on thyroid care to inform best practices and to optimize thyroid care delivery, including mitigating thyroid cancer disparities.

Conclusion

Disparities in the care of patients with thyroid disease occur because of societal and structural factors. Social determinants of health, which includes socioeconomic status and economic stability, language, education, and health literacy, as well as health care systems and health policy, impact clinical outcomes from thyroid disease. The proposed framework (Fig. 1) and the currently available data support the need for multilevel interventions to address known drivers of disparities from the societal, health care system, clinician, and patient perspective.

Contributor Information

Debbie W Chen, Division of Metabolism, Endocrinology & Diabetes, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI 48109, USA.

Naykky Singh Ospina, Division of Endocrinology, Department of Medicine, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL 32610, USA.

Megan R Haymart, Division of Metabolism, Endocrinology & Diabetes, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI 48109, USA.

Funding

Dr. Debbie Chen was supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number K08CA273047. Dr. Naykky Singh Ospina was supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number K08CA248972. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Disclosures

Authors have nothing to disclose.

Data Availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article because no datasets were generated or analyzed for this perspective.

References

- 1. Gillis A, Chen H, Wang TS, Dream S. Racial and ethnic disparities in the diagnosis and treatment of thyroid disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2023:dgad519. Doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgad519 [Online ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Davis S, Ullmann TM, Roman S. Disparities in treatment for differentiated thyroid cancer. Thyroid. 2023;33(3):287‐293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chen DW, Lang BHH, McLeod DSA, Newbold K, Haymart MR. Thyroid cancer. Lancet. 2023;401(10387):1531‐1544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. National Academies of Sciences Engineering and Medicine . Federal Policy to Advance Racial, Ethnic, and Tribal Health Equity. The National Academies Press; 2023. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Agarwal S, Wade AN, Mbanya JC, et al. The role of structural racism and geographical inequity in diabetes outcomes. Lancet. 2023;402(10397):235‐249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dhaliwal R, Pereira RI, Diaz-Thomas AM, Powe CE, Yanes Cardozo LL, Joseph JJ. Eradicating racism: an endocrine society policy perspective. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2022;107(5):1205‐1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Collins RA, McManus C, Kuo EJ, Liou R, Lee JA, Kuo JH. The impact of social determinants of health on thyroid cancer mortality and time to treatment. Surgery. 2024;175(1):57‐64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Azadnajafabad S, Saeedi Moghaddam S, Mohammadi E, et al. Global, regional, and national burden and quality of care index (QCI) of thyroid cancer: a systematic analysis of the global burden of disease study 1990-2017. Cancer Med. 2021;10(7):2496‐2508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ginzberg SP, Soegaard Ballester JM, Wirtalla CJ, et al. Insurance-based disparities in guideline-concordant thyroid cancer care in the era of de-escalation. J Surg Res. 2023;289:211‐219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chen DW, Reyes-Gastelum D, Veenstra CM, Hamilton AS, Banerjee M, Haymart MR. Financial hardship among hispanic women with thyroid cancer. Thyroid. 2021;31(5):752‐759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ettleson MD, Bianco AC, Zhu M, Laiteerapong N. Sociodemographic disparities in the treatment of hypothyroidism: NHANES 2007-2012. J Endocr Soc. 2021;5(7):bvab041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rivas AM, Larumbe E, Thavaraputta S, Juarez E, Adiga A, Lado-Abeal J. Unfavorable socioeconomic factors underlie high rates of hospitalization for complicated thyrotoxicosis in some regions of the United States. Thyroid. 2019;29(1):27‐35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Uppal N, Nee Lubitz CC, James B. The cost and financial burden of thyroid cancer on patients in the US: a review and directions for future research. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2022;148(6):568‐575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Betancourt JR, Renfrew MR, Green AR, Lopez L, Wasserman M. Improving Patient Safety Systems for Patients with Limited English Proficiency: a Guide for Hospitals. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bregio C, Finik J, Baird M, et al. Exploring the impact of language concordance on cancer communication. JCO Oncol Pract. 2022;18(11):e1885‐e1898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Roter DL, Gregorich SE, Diamond L, et al. Loss of patient centeredness in interpreter-mediated primary care visits. Patient Educ Couns. 2020;103(11):2244‐2251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ramakrishnan K, Ahmad FZ. State of Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders Series: A Multifaceted Portrait of a Growing Population. Center for American Progress; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Papaleontiou M, Reyes-Gastelum D, Gay BL, et al. Worry in thyroid cancer survivors with a favorable prognosis. Thyroid. 2019;29(8):1080‐1088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chen DW, Reyes-Gastelum D, Wallner LP, et al. Disparities in risk perception of thyroid cancer recurrence and death. Cancer. 2020;126(7):1512‐1521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Doubleday AR, Novin S, Long KL, Schneider DF, Sippel RS, Pitt SC. Online information for treatment for low-risk thyroid cancer: assessment of timeliness, content, quality, and readability. J Cancer Educ. 2021;36(4):850‐857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Parikh C, Ostrovsky AM. Analysis of trustworthiness and readability of English and Spanish hypo- and hyperthyroid-related online patient education information. J Patient Exp. 2023;10:23743735231179063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cimbek EA, Cimbek A. Online health information on thyroid nodules: do patients understand them? Minerva Endocrinol (Torino). 2023. [Online ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. US Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics: Institue of Education Sciences . The health literacy of America's adults. Results from the 2003 National Assessment of Adult Literacy; 2006: https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2006/2006483.pdf.

- 24. Chen DW, Reyes-Gastelum D, Hawley ST, Wallner LP, Hamilton AS, Haymart MR. Unmet information needs among hispanic women with thyroid cancer. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2021;106(7):e2680‐e2687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Nath B, Williams B, Jeffery MM, et al. Trends in electronic health record inbox messaging during the COVID-19 pandemic in an ambulatory practice network in New England. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(10):e2131490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Nishii A, Campos-Castillo C, Anthony D. Disparities in patient portal access by US adults before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMIA Open. 2022;5(4):ooac104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hsueh L, Huang J, Millman AK, et al. Disparities in use of video telemedicine among patients with limited English proficiency during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(11):e2133129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hauch A, Al-Qurayshi Z, Friedlander P, Kandil E. Association of socioeconomic status, race, and ethnicity with outcomes of patients undergoing thyroid surgery. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2014;140(12):1173‐1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Noureldine SI, Abbas A, Tufano RP, et al. The impact of surgical volume on racial disparity in thyroid and parathyroid surgery. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21(8):2733‐2739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Chen DW, Worden FP, Haymart MR. Access denied: disparities in thyroid cancer clinical trials. J Endocr Soc. 2023;7(6):bvad064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services . New reports show record 35 million people enrolled in coverage related to the affordable care act, with historic 21 million people enrolled in medicaid expansion coverage. 2022; Accessed November 3, 2023. https://www.hhs.gov/about/news/2022/04/29/new-reports-show-record-35-million-people-enrolled-in-coverage-related-to-the-affordable-care-act.html. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32. Ullmann TM, Gray KD, Limberg J, et al. Insurance status is associated with extent of treatment for patients with papillary thyroid carcinoma. Thyroid. 2019;29(12):1784‐1791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Greenberg JA, Thiesmeyer JW, Ullmann TM, et al. Association of the affordable care act with access to highest-volume centers for patients with thyroid cancer. Surgery 2022; 171(1):132‐139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Chen DW, Banerjee M, He X, et al. Hidden disparities: how language influences patients’ access to cancer care. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2023;21(9):951‐959.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Equal Employment Opportunity Program. Title VI, Prohibition against national origin discrimination affecting limited english proficient persons. Guidance to federal financial assistance recipients regarding Title VI, Prohibition against national origin discrimination affecting limited English proficient persons 2004; 69(7):1763-1768. https://www.archives.gov/eeo/laws/title-vi.html.

- 36. Schiaffino MK, Nara A, Mao L. Language services in hospitals vary by ownership and location. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(8):1399‐1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Muthukumar AV, Morrell W, Bierer BE. Evaluating the frequency of English language requirements in clinical trial eligibility criteria: a systematic analysis using ClinicalTrials.gov. PLoS Med. 2021;18(9):e1003758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health . Common Cancer Types. Accessed October 24, 2023. http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/types/commoncancers.

- 39. NIH National Cancer Institute . NCI Funded Research Portfolio; 2018. Accessed Novemeber 3, 2023. https://fundedresearch.cancer.gov/nciportfolio/.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article because no datasets were generated or analyzed for this perspective.