Abstract

Hemochromatosis is a primary or secondary pathological condition characterized by the deposition of excess iron in the body tissues, which can eventually lead to cellular damage and organ dysfunction. Although excess iron deposition in the central nervous system is rare, involvement of the choroid plexus, pituitary gland, cortical surfaces, and basal ganglia has been reported to date. This case report describes 2 cases of transfusion-induced hemochromatosis involving the choroid plexus and pituitary gland, which were diagnosed by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). In both cases, gradient echo (GRE) sequences, such as T2 star-weighted image and susceptibility-weighted imaging demonstrated markedly low signal intensity in the choroid plexus. Furthermore, the pituitary gland showed low signal intensity on T2-weighted images in Patient 2. Because these low signal intensities were not seen prior to red blood cell transfusion, they were diagnosed with transfusion-induced hemochromatosis. Brain MRI with GRE sequences was useful in detecting iron deposition in the choroid plexus. Considering that iron deposition in the body tissues can lead to irreversible organ damage, MRI with GRE sequences should be considered for patients with suspected iron overload.

Keywords: Hemochromatosis, Iron overload, MRI, Gradient echo, T2 star-weighted image, Susceptibility-weighted image

Introduction

Hemochromatosis is a primary or secondary pathological condition characterized by the deposition of excess iron in the body tissues, which can eventually lead to cellular damage and organ dysfunction [1,2]. Excess iron deposition occurs primarily in parts of the reticuloendothelial system such as the liver, spleen, and bone marrow. However, when these tissues' capacity is saturated, the excess iron is deposited in the heart, endocrine glands, skin, and joints. Although excess iron deposition in the central nervous system (CNS) is rare, the involvement of the choroid plexus, pituitary gland, cortical surfaces, and basal ganglia has been reported [3], [4], [5], [6], [7]. We report 2 cases of transfusion-induced hemochromatosis involving the choroid plexus and pituitary gland.

Case reports

Patient 1

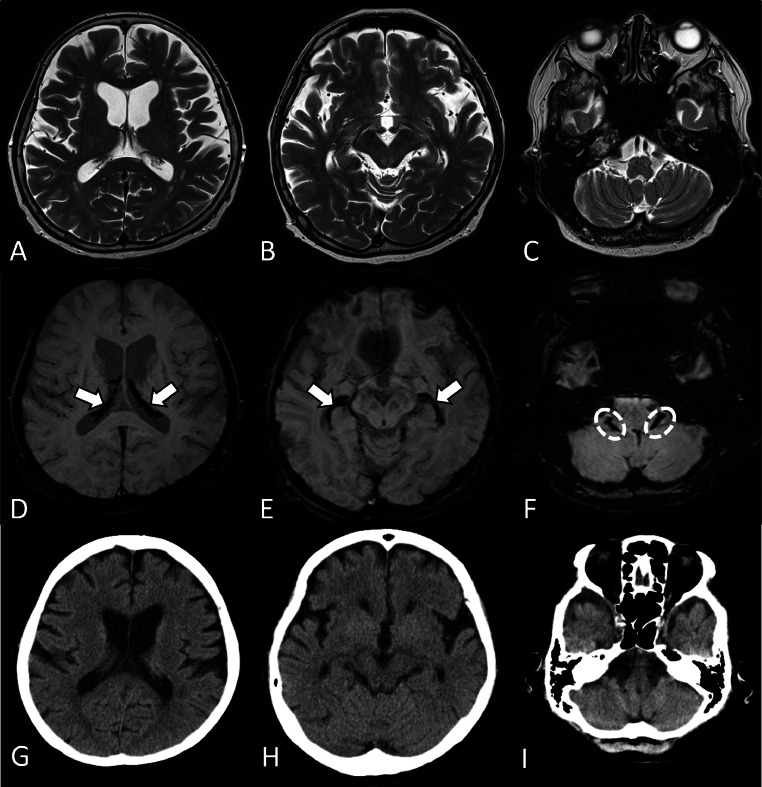

A 70-year-old Japanese woman showed abnormal findings on brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) conducted for the annual follow-up of an intracranial aneurysm. The patient had a history of double-expressor lymphoma and had received rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (R-CHOP), and she had undergone a peripheral-blood stem cell transplantation. Due to poor amelioration of the hematopoietic cells, she had been transfusion-dependent for 2 years. She had received red blood cell (RBC) transfusions every 2 weeks, and a total of 110 units of RBC had been transfused at the time of this MRI. The results of her physical and neurological examinations on admission were unremarkable, and her blood counts were normal. However, blood biochemistry showed an abnormally high ferritin level at 5609 ng/mL (reference range: 25-250). Brain MRI showed scattered nonspecific high signal intensities in the bilateral cerebral white matter on T2-weighted images (T2WI) and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) images. On susceptibility-weighted imaging (SWI), the choroid plexus of the lateral ventricles, the fourth ventricle, and the foramina of Luschka showed markedly low signal intensity that was undetectable on T2WI (Figs. 1A–F). On computed tomography (CT), no calcifications were observed in these low signal intensities (Figs. 1G–I). These low signal intensities were not seen on the patient's MRI examinations prior to the RBC transfusion, leading to the diagnosis of transfusion-induced hemochromatosis of the choroid plexus. The patient received iron chelation therapy, which was discontinued due to drug-induced liver injury; she died 2 years later due to a recurrence of the lymphoma.

Fig. 1.

Brain CT and MRI findings of Patient 1, a 70-year-old woman. Axial T2-weighted images (A–C) show no obvious abnormal signal intensity in the choroid plexus. In contrast, axial susceptibility-weighted images at the same slice levels (D–F) show marked hypointensity in the choroid plexus of the lateral ventricles (arrows) and in the foramina of Luschka (dashed ovals). Axial CT (G–I) demonstrates no calcification in these low signal intensities, indicating choroid plexus hemochromatosis.

Patient 2

A 37-year-old Japanese man was admitted to our hospital due to impaired consciousness. The patient had a history of alcoholic cirrhosis. Physical and neurological examinations revealed marked skin yellowing and hepatic halitosis. A laboratory examination revealed anemia, decreased platelets, and hyperammonemia: RBC count 1.06 × 10^6/μL, hemoglobin 4.8 g/dL, platelet count 7.3 × 10^4/μL, and ammonia 151 μmol/L (reference range: 30-80 μmol/L). Based on these findings, the patient was diagnosed with hepatic encephalopathy.

Brain MRI showed high signal intensity in the bilateral globus pallidus on T1-weighted images (T1WI), consistent with hepatic encephalopathy. A total of 32 units of RBCs were transfused to treat the patient's anemia. The patient's serum transferrin level after a transfusion of 4 units of RBC was 706 ng/mL (reference range: 25-250 ng/mL). After treatment for hepatic encephalopathy, the patient was discharged from the hospital but was readmitted to our hospital again due to impaired consciousness.

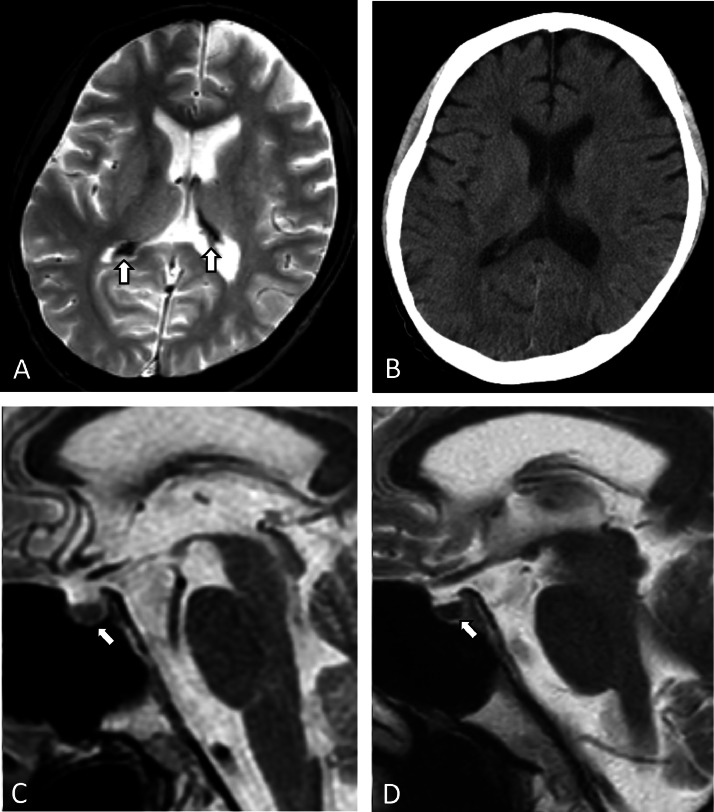

On readmission, the patient's blood ammonia level was elevated (149 μmol/L), and a worsening of hepatic encephalopathy was suspected. MRI was performed for the assessment of the cause of the patient's impaired consciousness. In addition to bilateral hyperintensity in the globus pallidus on T1WI, T2 star-weighted images (T2*WI) showed markedly low signal intensity in the choroid plexus of the lateral ventricles, the fourth ventricle, and the foramina of Luschka (Fig. 2A). On CT, no calcifications were observed in these hypointense lesions (Fig. 2B). The pituitary gland showed low signal intensity on T2WI (Figs. 2C and D); the signal ratio of the pituitary gland to the basilar pons decreased from 1.05 to 0.73 prior to and after a transfusion of 32 units of RBC. The patient was diagnosed with transfusion-induced hemochromatosis of the choroid plexus and pituitary gland. A pituitary function test showed no apparent pituitary dysfunction. The patient was treated for cirrhosis but died 1 month after the readmission.

Fig. 2.

Brain CT and MRI findings of Patient 2, a 37-year-old man. The choroid plexus shows marked hypointensity on T2 star-weighted images (A, arrows). Axial CT demonstrates no calcification in the choroid plexus (B). A sagittal T2-weighted image prior to the transfusion of red blood cells (RBC) shows no abnormalities in the pituitary gland (C, arrow). A sagittal T2-weighted image after the RBC transfusion shows decreased signal intensity of the pituitary gland (D, arrow). These findings are consistent with choroid plexus and pituitary hemochromatosis.

Discussion

Hemochromatosis is a systemic disease characterized by excess iron deposition in parenchymal cells that can eventually lead to cellular damage and organ dysfunction [1]. This disorder can be classified into primary and secondary hemochromatosis [2]. Primary hemochromatosis is a genetic disorder that alters a protein involved in the regulation of iron absorption. Secondary hemochromatosis is a nongenetic cause of iron accumulation in the organs, including (1) increased iron absorption, such as cirrhosis, (2) myelodysplastic syndrome, (3) anemias associated with ineffective erythropoiesis (e.g., thalassemia), and (4) an exogenous increase in iron due to ingestion, parenteral infusion, or repeated blood transfusions [8].

Iron is an essential element for proper cellular function and is involved in many important physiological activities including hemoglobin synthesis, oxygen transport, and ATP production [9]. Excess iron can produce numerous harmful reactive oxygen species that can damage cellular membranes, proteins, and DNA [10]. Because humans have no physiologic pathway for iron excretion, the body's systemic or cellular iron homeostasis is maintained by finely regulating iron absorption, circulation, utilization, and storage [1]. Maintaining a homeostatic iron balance requires only 1 to 2 mg of iron per day; each unit of packed RBC contains approx. 100 mg of iron. Thus, after receiving only 10 to 20 units of RBC transfusions, patients can begin to accumulate a significant amount of iron [11]. A total of 110 units of RBC were transfused in the present Patient 1 and a total of 32 units of RBC were transfused in Patient 2.

As noted in the Introduction, hemosiderin initially accumulates in the reticuloendothelial system, including the spleen, bone marrow, and liver [1], and if these become saturated, excess iron is deposited in other tissues. Although iron deposition can occur anywhere in the body, CNS involvement is rare. Because brain cells are normally well shielded from iron deposition by the blood-brain-barrier (BBB), CNS hemochromatosis has been reported mainly outside the BBB, including the choroid plexus and the pituitary gland [7]. CNS hemochromatosis tends to be asymptomatic unless the pituitary gland is affected, which can result in hypopituitarism [6,12,13]. The choroid plexus has been shown to be an important interface for brain iron homeostasis and is hypothesized to protect the brain from iron deposition through a buffering mechanism [3,4]. Considering that iron deposition in the body tissues can lead to irreversible organ damage, the early detection of iron deposition in the choroid plexus could provide valuable information for the diagnosis and assessment of the severity of iron deposition in the CNS, even if the patient is asymptomatic.

MRI has been established as the most useful imaging modality for the assessment of iron deposition. Excess iron ions cause local distortions in the magnetic fields and relaxation of the spins, resulting in shortening of the T2 relaxation time and especially the T2* relaxation time [8]. Brain MRI with a gradient echo (GRE) sequence demonstrated increased sensitivity in detecting CNS hemochromatosis. T2*WI has been shown to be superior to T2WI in detecting pituitary hemochromatosis, and the degree of signal intensity on T2*WI correlates with the severity of pituitary dysfunction [14,15]. SWI is a high-spatial-resolution 3D-GRE MRI sequence with phase post-processing that enhances the paramagnetic properties, and it is more sensitive for detecting hemosiderin than conventional 2D-GRE MRI [16]. In Patient 1, SWI clearly demonstrated hemosiderin deposition in the choroid plexus with high spatial resolution. However, the pituitary gland could not be evaluated due to susceptibility artifact due to the air of the sphenoid sinus. There have been 2 case reports describing iron deposition in the choroid plexus with the application of SWI, but neither report mentioned imaging findings of the pituitary gland [[6], [17]]. Considering that the sella turcica is surrounded by the air of the sphenoid sinus, SWI may not be suitable for evaluations of the pituitary gland. Quantitative susceptibility mapping (QSM) is an MR imaging technique that measures the magnetic susceptibility of tissues such as blood or the iron content. An earlier study using QSM showed that the choroid plexus in patients with thalassemia had significantly higher susceptibility values compared to healthy control subjects [18]. These GRE MRI sequences can be used to noninvasively diagnose and assess the severity of iron deposition in the CNS.

Conclusion

Two cases of transfusion-induced hemochromatosis involving the choroid plexus and pituitary gland were presented. Although rare, excess iron can be deposited in the CNS, particularly outside of the BBB at sites such as the choroid plexus and pituitary gland. Brain MRI with GRE sequences was useful in detecting iron deposition in the choroid plexus. Considering that iron deposition in body tissues can lead to irreversible organ damage, MRI with GRE sequences should be considered for patients with a suspected iron overload.

Patient consent

Written informed consent was obtained from both patients for publication of this case report.

Footnotes

Competing Interests: The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- 1.Fleming RE, Ponka P. Iron overload in human disease. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:348–359. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1004967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hollán SR. Transfusion-associated iron overload. Curr Opin Hematol. 1997;4:436–441. doi: 10.1097/00062752-199704060-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morris CM, Keith AB, Edwardson JA, Pullen RG. Uptake and distribution of iron and transferrin in the adult rat brain. J Neurochem. 1992;59:300–306. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1992.tb08904.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rouault TA, Zhang DL, Jeong SY. Brain iron homeostasis, the choroid plexus, and localization of iron transport proteins. Metab Brain Dis. 2009;24:673–684. doi: 10.1007/s11011-009-9169-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Duprez T, Maiter D, Cosnard G. Transfusional hemochromatosis of the choroid plexus in beta-thalassemia major. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2001;25:487–488. doi: 10.1097/00004728-200105000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Verberckmoes B, Dekeyzer S, Decaestecker K. The dark pituitary: hemochromatosis as a lesser-known cause of pituitary dysfunction. J Belg Soc Radiol. 2022;106:63. doi: 10.5334/jbsr.2771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim MS, Lee HY, Lim MK, Kang YH, Kim JH, Lee KH. Transfusional iron overload and choroid plexus hemosiderosis in a pediatric patient: brain magnetic resonance imaging findings. Investig Magn Reson Imaging. 2019;23:390–394. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Queiroz-Andrade M, Blasbalg R, Ortega CD, Rodstein MA, Baroni RH, Rocha MS, et al. MR imaging findings of iron overload. Radiographics. 2009;29:1575–1589. doi: 10.1148/rg.296095511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sun K, Guo Z, Hou L, Xu J, Du T, Xu T, et al. Iron homeostasis in arthropathies: from pathogenesis to therapeutic potential. Ageing Res Rev. 2021;72:101481. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2021.101481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Andrews NC. Disorders of iron metabolism. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1986–1995. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199912233412607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Olivieri NF, Brittenham GM. Iron-chelating therapy and the treatment of thalassemia. Blood. 1997;89:739–761. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gurung B, Maheshwari S, Grewal DS, Regmi P, Khadka A. Transfusion-related hemochromatosis involving pituitary gland in a patient of beta-thalassemia major. Hospital Pract Res. 2022;7:37–40. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ippolito S, Sabatino J, Tanda ML. Pituitary in black-hypopituitarism secondary to hemosiderosis. Endocrine. 2018;61:545–546. doi: 10.1007/s12020-018-1568-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sparacia G, Iaia A, Banco A, D’Angelo P, Lagalla R. Transfusional hemochromatosis: quantitative relation of MR imaging pituitary signal intensity reduction to hypogonadotropic hypogonadism. Radiology. 2000;215:818–823. doi: 10.1148/radiology.215.3.r00jn10818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sparacia G, Banco A, Midiri M, Iaia A. MR imaging technique for the diagnosis of pituitary iron overload in patients with transfusion-dependent beta-thalassemia major. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1998;19:1905–1907. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tong KA, Ashwal S, Obenaus A, Nickerson JP, Kido D, Haacke EM. Susceptibility-weighted MR imaging: a review of clinical applications in children. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2008;29:9–17. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A0786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sossa DE, Chiang F, Verde AR, Sossa DG, Castillo M. Transfusional iron overload presenting as choroid plexus hemosiderosis. Jbr-btr. 2013;96:39118. doi: 10.5334/jbr-btr.474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Qiu D, Chan GC, Chu J, Chan Q, Ha SY, Moseley ME, et al. MR quantitative susceptibility imaging for the evaluation of iron loading in the brains of patients with β-thalassemia major. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2014;35:1085–1090. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A3849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]