Abstract

Small ubiquitin-like modifier (SUMO) modification of sequence-specific transcription factors has profound regulatory consequences. By providing an intrinsic inhibitory function, SUMO isoforms can suppress transcriptional activation, particularly at promoters harboring multiple response elements. Through a comprehensive structure-function analysis, we have identified a single critical sector along the second beta sheet and the following alpha helix of SUMO2. This distinct surface is defined by four basic residues (K33, K35, K42, R50) that surround a shallow pocket lined by aliphatic (V30, I34) and polar (T38) residues. Substitutions within this area specifically and dramatically affected the ability of both SUMO2 and SUMO1 to inhibit transcription and revealed that the positively charged nature of the key basic residues is the main feature responsible for their functional role. This highly conserved surface accounts for the inhibitory properties of SUMO on multiple transcription factors and promoter contexts and likely defines the interaction surface for the corepressors that mediate the inhibitory properties of SUMO.

Eukaryotic transcriptional control relies strongly on the power of combinatorial regulation (53). In a given cell, genes can draw unique sets of regulatory factors from a relatively small pool based on their specific arrangement of cis-acting elements. The often synergistic functional interactions between these factors give rise to the complex patterns of gene expression required for the appropriate physiological performance of cells (6, 9). The regulatory repertoire of each factor can be further expanded by structural alterations induced by binding of ligands or posttranslational modifications, as in the case of the glucocorticoid receptor (GR) and other steroid hormone receptors (53). Subtle mutations that disturb ligand binding or covalent attachment can lead to profound alterations in the outcome of functional interactions among factors. For example, we have identified a short regulatory motif embedded in GR and many other sequence-specific regulators that is both necessary and sufficient to limit their transcriptional synergy (23). Disruption of these conserved synergy control (SC) motifs selectively enhances synergistic activation at compound response elements without altering the activity driven from a single site. In order to exert their effects, SC motifs need to be recruited to multiple independent sites on the DNA, and this feature accounts for their selective effects at compound response elements (20). The function of SC motifs is not circumscribed to inhibit synergistic activation driven by the factor in which they are embedded (in-cis effects) but are also capable of affecting separate activators bound nearby (in-trans effects). Based on the convergence between SC motifs and the consensus sequence for posttranslational modification by members of the small ubiquitin-like (Ubl) modifier (SUMO) family, we (20, 47) and others (51) have shown that SC motifs function as SUMO acceptor sites and that this modification is responsible for the functional properties of SC motifs. An inhibitory role for SUMOylation in sequence-specific transcription factors is also supported by multiple studies showing that disruption of acceptor lysines results in enhanced activation (1, 4, 7, 19, 27, 37, 39).

The SUMO family is a member of a growing class of Ubl proteins that share a common structural fold and core enzymological pathway of conjugation but have distinct amino acid sequences and functions (24, 38, 42, 46). Preparation of SUMO for modification of proteins involves two steps carried out by specific E1-activating (SAE1/SAE2) (14) and E2 transfer (UBC9) (10) enzymes. UBC9 interacts directly with the core SUMOylation consensus sequence in the target protein and catalyzes the formation of an isopeptide bond between the C terminus of SUMO and the amino group of the target lysine. Although SUMOylation can be achieved without an E3 activity in vitro, proteins like RanBP2 (29, 35) and members of the PIAS family (7, 25, 29, 34, 41, 47) have E3-like activity and enhance SUMO conjugation. As with other Ubl proteins, SUMOylation is reversible and specific isopeptidases such as SUSP1 or SENP1 and -2 release the SUMO moiety (3, 17, 28). Both E3 and peptidase activities are likely to contribute to the specificity and regulation of SUMOylation. The mammalian SUMO family consists of at least four SUMO isoforms designated SUMO1 through -4. SUMO2 and -3 share approximately 95% identity, and SUMO1 is ∼48% identical to SUMO2 or -3. The recently described SUMO4 is closely related to SUMO2/3 and seems to have a more restricted pattern of expression. Mutations in SUMO4 are genetically linked to type 1 diabetes (5, 16). In contrast to SUMO1, the other isoforms harbor a consensus SUMOylation site at their N-terminal region and likely form chains, as demonstrated for SUMO2 (50).

As pioneered in the ubiquitin field (44), the analysis of SUMO function has been greatly aided by the use of colinear noncleavable fusions between SUMO and target proteins. This approach allows direct control over the SUMO isoform attached to the protein without directly interfering with the modification of endogenous proteins. Recruiting SUMO to promoters as fusions to heterologous DNA binding domains (20, 37, 54) or entire activators such as SP3 (37) or GR (20) revealed that SUMO possesses an intrinsic transcriptional inhibitory activity that accounts for the in-trans and in-cis inhibitory functions of SC motifs (20). Although it is likely that the exact context of modification within an activator is important in determining the full functional consequences of SUMOylation, these observations suggest that generating an internal branched structure is not essential for the expression of the inhibitory properties of SUMO. Comparison of the different SUMO isoforms revealed that irrespective of their ability to form chains, SUMO2 and -3 are more inhibitory than SUMO1 and deletion of the N-terminal tail of SUMO indicates that the core Ub fold region is sufficient for inhibition (20).

The molecular mechanism by which SUMO inhibits transcription is not fully understood. We have proposed that binding of SUMO-modified SC motifs at multiple DNA sites creates a multivalent recognition surface for one or more inhibitory factors that directly contact SUMO. The nature of such factors remains ill defined, but recent results indicate that histone deacetylases may be important components since they are recruited to promoters occupied by SUMOylated sequence-specific factors, such as Elk1, and interact with p300 in a SUMOylation-dependent manner (12, 54). In addition, disruption of SUMO acceptor sites can lead to detectable alterations in the subcellular and subnuclear localization of the target proteins (31, 37, 55). Whether such redistribution is mechanistically linked to transcriptional inhibition of sequence-specific factors has not been fully demonstrated but remains an attractive hypothesis.

In addition to mediating the effects of SC motifs, SUMOylation plays important roles at other steps of transcriptional regulation since both positive and negative coregulators (histone deacetylases, P300, GRIP1, SRC-1, CtBP), as well as histones, are SUMOylated (8, 12, 30, 31, 43). Moreover, SUMOylation extends beyond nuclear proteins and likely contributes to the regulation of multiple cellular processes (52). Structural characterization of ubiquitin and Ubl proteins alone or in complexes with multiple proteins is beginning to reveal the various ways by which a common structural fold is used to interact specifically with both the conjugation machinery and the mediators of their function. A direct transcriptional regulatory role for SUMO appears well established, but the structural basis and determinants of SUMO function are poorly understood.

In this study we have taken advantage of both the ability of SUMO fusions to inhibit transcription and existing structural information to probe the entire surface of SUMO and define the determinants essential for one of its functions: transcriptional inhibition. This analysis identified a single critical region along the second β sheet and the downstream α helix of SUMO2. The highly conserved residues that populate this region define a likely contact surface for the cellular factors that mediate the transcriptional inhibitory functions of SUMO. Variants of SUMO with specific functional defects will undoubtedly constitute invaluable tools to identify such factors and clarify the mechanism of action of this family of Ubl proteins.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Homology modeling and evolutionary analysis.

Homology modeling was carried out using Swiss PDB viewer software (15) (SPDBV V3.7) using the crystal structure coordinates of SMT3 (residues 20 to 98) as template (33). Structure-based alignment with human SUMO2 (residues 20 to 98) indicated the presence of a one-amino-acid insertion in SUMO2 accommodated in the loop between the first and second β strands. This loop (residues 25 to 26) was built onto the initial output of the Expasy Swiss-Model server (15) using the loop database in SPDBV, followed by local energy minimization (GROMOS 89) using harmonic constraints. Residues making clear clashes or with unfavorable calculated force field energies, as well as their immediate neighbors, were identified and subjected to local energy minimization using harmonic constraints. Several independent runs of global energy minimization yielded nearly identical models with energies near −5,300 kJ/mol and main chain RMS deviations with the SMT3 structure of <0.45 Å. The final model was analyzed with Procheck v3.5 and WhatIf v4.99 and yielded favorable parameters. The region between strands 4 and 5, which in ubiquitin and some other Ubl proteins is composed by several turns of α helix, contains a single, distorted turn in the model and is represented as a coil region as in the case of SMT3 (33). A nearly equivalent model was obtained using the more recent SUMO1 X-ray structure data (36). Relative solvent-accessible surface area for each residue was calculated with the program GETAREA using a probe radius of 1.4 Å (11). Conservation scores were based on a structure-based alignment of 35 sequences spanning a wide spectrum of phyla and were obtained with the program ConSurf (13).

Mammalian expression plasmids.

Rous sarcoma virus-driven expression vectors for wild-type (WT) (p6R GR) and SC mutant (p6R GR K297R/K313R) rat GR, as well as for the cytomegalovirus (CMV)-driven (pCDNA3) expression vectors for noncleavable hemagglutinin (HA)-SUMO1, HA-SUMO2, and HA-NEDD8 fusions to the Gal4 DNA binding domain (DBD), have been described previously (20, 23). The expression vectors for HA-tagged versions of WT (p6R HA-GR) and SC mutant (p6R HA-GR K297R/K313R) GR, as well as noncleavable N-terminal fusions of HA-SUMO1 or HA-SUMO2 to SC mutant GR, have also been described previously (20). A PCR-based method (40) was used for mutagenesis of SUMO1 and -2 using the corresponding HA-SUMO Gal4 DBD fusion as templates. Mutations were transferred to the corresponding HA-SUMO GR fusion context as XbaI/BamHI fragments. The CMV-driven expression vector for the p42 form of mouse C/EBPα and SC mutant human androgen receptor (AR) are described in references 47 and 23, respectively. To generate the pG4(VP16)2 plasmid containing two copies of the VP16 activation domain downstream of the first 100 residues of the Gal4 DBD, pGal4(VP16)2 (23) was digested with EcoRI and BsrGI, completely filled in, and religated. For the construction of expression vectors for noncleavable HA-SUMO2 (WT or K33E/K42E) fusions to GAL4(VP16)2, HindIII/BsrGI fragments excised from the corresponding HA-SUMO2 Gal4 DBD vectors were ligated into the same sites of pG4(VP16)2. CMV-driven vectors for the expression of HA-SUMO2 (WT and point and deletion mutants), where the residues beyond the C-terminal Gly-Gly motif are deleted (GG stop) or for cleavable fusions to the Gal4 DBD, were constructed as follows. Selected HA-SUMO2 Gal4 vectors were PCR amplified using primers 5′-CAGGTACCATGGCCCTCGAGTACCCATACGA-3′ (forward) and either 5′-TAGCGAATTCAACCTCCCGTCTGCTGTTGG-3′ (GG stop reverse) or 5′-CATGGAATTCAGTAGACACCTCCCGTCTGCTGTTGGAACACATC-3′ (cleavable fusion reverse). The resulting fragments were digested with XbaI and EcoRI or XbaI and BamHI and ligated into the same sites of pCDNA3.1(+) HA-SUMO2 and pcDNA3.1(+) HA-SUMO2 GAL4 DBD, respectively (20).

Reporter plasmids.

The pΔODLO reporter plasmid, where a minimal Drosophila distal alcohol dehydrogenase promoter (−33 to +55) drives the luciferase gene, as well as its derivatives pΔTAT1-Luc and pΔTAT3-Luc that harbor one and three copies of a minimal glucocorticoid response element (GRE) from the tyrosine aminotransferase (TAT) gene, are described in reference 23. The reporters pΔ(Gal)2(TAT)1-Luc and pΔ(Gal)2(TAT)3-Luc harbor two Gal4 sites upstream of a single or three copies of the TAT GRE and are described in reference 20. The oligonucleotides 5′-GATCCGGAGGACTGTCCTCCA-3′ and 5′-GATCTGGAGGACAGTCCTCCG-3′, containing a single Gal4 binding site, were annealed and ligated into the BamHI and BglII sites of pΔODLO 02 (47) to yield pΔ(Gal4)1-Luc. Ligation of BseRI/BglII and BamHI/BseRI fragments of the same vector yielded pΔ(Gal4)2-Luc. Ligation of the BseRI/SalI fragment of pΔ(Gal4)2-Luc and XhoI/BseRI fragment of pΔ(CAAT)2-Luc (47) yielded pΔ(Gal4)2(CAAT)2-Luc. All manipulated regions in constructs were confirmed by automated sequencing.

Cell culture, transfections, and immunoblotting.

Green monkey CV-1 cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Gibco-BRL) supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum. Cells were transfected using Lipofectamine and plus reagent (Invitrogen) and received equimolar amounts of each type of expression plasmid to control for promoter effects. For functional assays, 3 × 104 cells were seeded onto 24-well plates and transfected 24 h later. For in-trans experiments, cells received 30 ng of either GR or AR expression vector (3 ng of C/EBPα in Fig. 7a) and 30 ng (or the indicated amounts) of Gal4-fusion expression vector. For in-cis experiments, cells received 30 ng (or the indicated amounts) of activator expression plasmid. All transfections included 50 ng (10 ng for Fig. 7a) of the indicated reporter plasmid and 50 ng of a CMV-driven β-galactosidase expression vector. The total amount of DNA was supplemented to 0.3 μg/well with pBSKS(+). For GR and AR experiments, cells were exchanged after 16 h into medium containing 10 nM dexamethasone, 100 nM dihydrotestosterone, or vehicle (0.1% ethanol). Cells were lysed 36 to 40 h posttransfection, and luciferase and β-galactosidase activities were determined as previously described (20). Average normalized activity values ± the standard error of the mean (SEM) for the reference activator are shown in the corresponding figure legends. For Western blotting, cells from duplicate wells transfected exactly as described above were lysed in 100 μl of 1× Laemmli sample buffer containing 300 mM NaCl. In experiments involving GR derivatives, cells were treated with agonist. Samples were resolved (10 or 7.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis [SDS-PAGE]) and processed for immunoblotting using monoclonal HA-11 (Covance) primary antibody as previously described (20). Experiments were performed at least thrice with similar results.

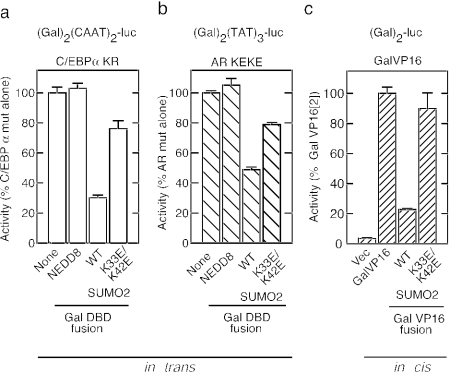

FIG. 7.

The inhibitory surface of SUMO2 influences multiple activators. The ability of the inhibitory surface of SUMO2 to act on multiple activators was tested in trans for SC mutant CEBPα (K159R) from pΔ(Gal)2(CAAT)2-Luc reporter (a) and SC mutant androgen receptor (K385E/K518E) from pΔ(Gal)2(TAT)3-Luc (b)using the indicated Gal4 DBD fusions. (c) In-cis fusions of WT or K33E/K42E SUMO2 to Gal4-VP16 were tested at pΔ(Gal)2-Luc. Cells in panel b were treated with 100 nM dihydrotestosterone. Data represent the average ± SEM of at least three independent experiments performed in triplicate and are expressed as a percentage of the activity of the corresponding activator alone as follows: pΔ(Gal)2(CAAT)2-Luc, 54 ± 2; pΔ(Gal2)2(TAT)3-Luc, 60 ± 5; pΔ(Gal)2-Luc, 300 ± 35. Vec, vector.

Protein-protein interaction assays, in vivo SUMO conjugation, and processing.

SUMO proteins were translated in vitro (T7-TNT Quick; Promega) in the presence of [35S]methionine using pCDNA3.1+ HA-SUMO2Δ(1-16)-GG stop (WT or K33E/K42E) as the template. Binding reaction mixtures (50 μl) were prepared essentially as previously described (47) and contained 1.2 nmol of purified glutathione S-transferase (GST) or GST-hUBC9 fusion protein bound to 20 μl of glutathione-Sepharose 4B (Amersham Biosciences), as well as 10 μl of 35S-labeled proteins in a binding buffer containing 50 mM NaCl and 1 mg/ml of bovine serum albumin. The resin was washed four times with 1 ml of 0.1% Nonidet P-40 in phosphate-buffered saline. The beads and 1 μl of the corresponding load were boiled in a final volume of 40 μl of SDS-PAGE sample buffer, and 25% of the samples were resolved by 12% SDS-PAGE. Results were confirmed in at least two independent experiments. For in vivo SUMOylation and processing assays, 1.2 × 105 CV-1 cells were seeded into six-well plates and transfected with 0.1 μg of pCDNA3.1(+)-based plasmids expressing the indicated variants of HA-SUMO2 GG stop, HA-SUMO2-Gal4 fusions, or empty vector. The total amount of DNA was supplemented to 1.3 μg/well with pBSKS(+). Forty hours after transfection, cells were harvested and total cell extracts were resolved (10% SDS-PAGE) and immunoblotted as described above.

RESULTS

A small surface in SUMO2 is essential for transcriptional inhibition.

We have previously shown that colinear noncleavable fusions of SUMO isoforms to the Gal4 DBD are powerful inhibitors of transcription induced by nearby bound activators. At a promoter bearing two Gal4 sites upstream of a single GRE, a SUMO2-Gal4 fusion inhibits activity of a GR lacking its own functional SC/SUMOylation motifs to 20%, whereas the fusion to the related NEDD8 protein fails to do so (Fig. 1). This in-trans inhibition is a suitable context in which to examine systematically the consequences of mutations in SUMO since the effects of the mutation are circumscribed to the fusion protein, leaving the endogenous pool of SUMO intact. To guide our choice of mutations, we constructed a three-dimensional model of SUMO2 based on the crystal structure of SMT3, the yeast SUMO homolog (see Materials and Methods). Since a SUMO2 fusion lacking its N-terminal tail retains its inhibitory properties (20), we focused on residues within the ubiquitin fold domain and C-terminal tail. Initially, all the residues predicted to have more than 10% of their side chains exposed to solvent, as well as selected buried residues, were replaced with alanine and tested for function as Gal4 fusions (surface alanine scan mutagenesis). As shown in Fig. 1, the substitution of only a minor number of exposed side chains (7/54) had a significant effect on the inhibitory activity of SUMO2, and four of these residues are positively charged. These functionally important surface residues cluster in a contiguous section (amino acids 30 to 50) that corresponds to the second β sheet and the following α helix of the model. Substitution of Tyr 47, a completely buried core residue within this section, had the most dramatic effect, likely due to large structural alterations in the protein. In contrast, mutation of other downstream buried residues (F60, I67, T72, and M78) had only minor functional effects.

FIG. 1.

Identification of SUMO2 residues involved in repression of GR activity in trans. (a) Effects of single alanine substitutions in SUMO2 on the ability of SUMO2-Gal4 fusions to inhibit ligand-activated SC mutant GR in trans at the pΔ(Gal)2(TAT)1-Luc reporter. Shading of the bars is according to the predicted surface exposure of the corresponding residue. Immunoblot data confirming the expression of the Gal4 fusion proteins are shown below the graph. A schematic representation of GR highlights the two SC/SUMOylation motifs within the N-terminal activation domain (AF-1). The Lys-to-Arg mutations in the SC mutant form are shown below the WT sequence. The DBD and ligand binding domain (LBD) are also indicated. The Δ(Gal)2(TAT)1-Luc reporter is also schematized. Data represent the average ± SEM of at least three independent experiments performed in duplicate or triplicate and are expressed as a percentage of SC mutant GR activity alone (4.9 ± 0.4). (b) Sequence alignment of SUMO and related Ubl proteins. Only residues tested in panel a are shown. Coloring is based on residue type. The locations of secondary-structure elements are shown below the alignment.

To visualize the location of critical surface residues, we mapped the activity data onto the surface of the SUMO2 model and compared it to the calculated electrostatic potential and evolutionary conservation. As shown in Fig. 2, the functionally relevant residues cluster on a distinct sector of the front surface of SUMO2 that corresponds to a region of high conservation. The four important basic residues, two from the end of the second β sheet (K33 and K35) and two at the beginning and end of the α helix (K42 and R50) give this sector its positive electrostatic potential (Fig. 2a, middle right). These residues form the boundaries of a shallow rectangular cavity lined in part by the side chains of the other three functionally relevant residues (V30, I34, and T38), which are aligned diagonally across the floor. In contrast, the opposite or back face of SUMO is negatively charged due to a cluster of acidic residues (Fig. 2b, middle right) and is unaffected by alanine substitutions except for a mild effect at position 82 in the center of the acidic patch.

FIG. 2.

Functionally relevant residues cluster in a distinct region of the surface of SUMO2. Front (a) and back (b) views of ribbon and space-filling representations of the SUMO2 homology model are shown. Coloring of the two leftmost panels is according to the data of Fig. 1 and is normalized to the scale shown below the central panel, ranging from no effect (green) to most deleterious (red). Buried (B) residues predicted to be less than 10% exposed or not tested (NT) are shown in dark and light blue, respectively. In the two rightmost panels, coloring is according to the calculated electrostatic potential from red (negative) to blue (positive) and relative (Rel.) conservation across multiple species, respectively. Residues involved in Ubc9 and SENP2 binding, as well as specific relevant residues, are indicated by the arrows. term, terminus.

Role of positively charged residues in SUMO2.

The surface of SUMO2 is rich in charged residues, and the above experiments identified four basic residues (K33, K35, K42, and R50) as critical for transcriptional inhibition. To determine whether it is the basic character of these four residues or simply their charged nature that determines their functional role, we substituted them with either Lys or Arg to preserve their basic character or to Glu to reverse their polarity but preserve their charged nature (Fig. 3). The same substitutions were applied to K21, a nearby residue that is conserved but does not appear to be involved in transcriptional inhibition (Fig. 1). The effect of these mutations was analyzed in the context of fusions to Gal4 as in Fig. 1, as well as to GR itself to determine whether these residues play similar roles when SUMO inhibits GR-mediated activation in trans or in cis.

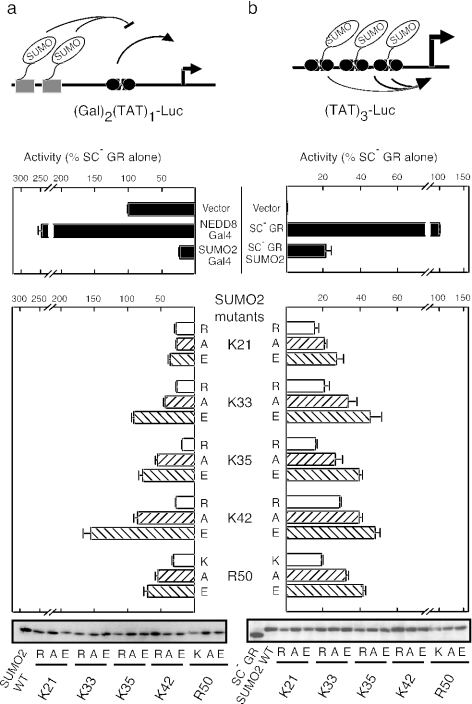

FIG. 3.

The positive charges of K33, K35, K42, and R50 are critical features for SUMO2-mediated inhibition of GR activity in trans and in cis. (a) Effects of substitutions at select basic residues of SUMO2 on the ability of SUMO2-Gal4 fusions to inhibit SC mutant GR in trans. (b) Effects of the same substitutions on the ability of SUMO2 to inhibit transcription in cis when fused at the N terminus of SC mutant GR. Cells were treated with 10 nM dexamethasone and processed as described in Materials and Methods. Diagrams of the reporter plasmids are shown above the corresponding panels, and expression levels (anti-HA immunoblot) of the fusion proteins are shown below. For both panels a and b, data represent the average ± SEM of at least three independent experiments performed in triplicate and are expressed as a percentage of SC mutant GR activity alone, which was 5.7 ± 0.57 and 190 ± 2 at pΔ(Gal)2(TAT)1-Luc and pΔ(TAT)3-Luc, respectively.

As shown in Fig. 3, conservative substitutions that preserve the basic character of the critical residues did not affect the ability of SUMO to inhibit GR in trans (Fig. 3a) or in cis (Fig. 3b). In the context of the GR fusions, alanine substitutions that remove the charged nature of the residues led to significant defects in SUMO-mediated inhibition. The extent of the effects is comparable to that observed in trans. However, when the substitution introduced a large charge perturbation (Lys or Arg to Glu) the inhibitory activity of SUMO is further reduced compared to the corresponding alanine variants both in trans and in cis. The most severe effects are observed for K42 and K33, followed by K35 and R50. The similar patterns of responses for both in-trans and in-cis effects suggest that these residues play similar roles in both contexts. Consistent with the lack of involvement of K21 in transcriptional inhibition, none of the substitutions at this position had a major impact. Taken together, the results indicate that the basic character of these four residues is the main determinant of their functional role.

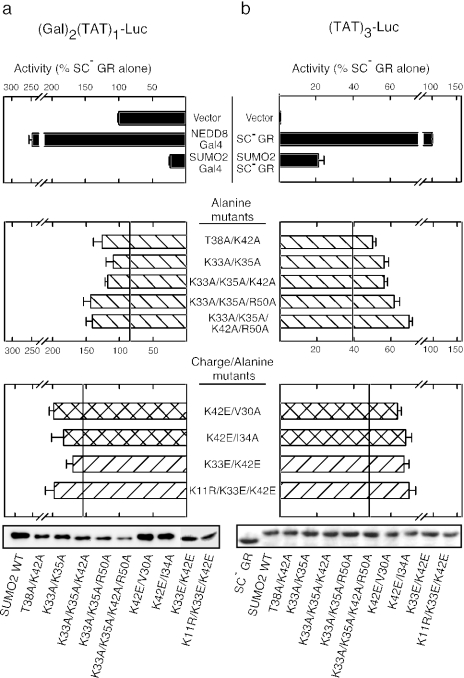

Compound mutations further impair SUMO2 transcriptional inhibition.

The above results indicate that multiple residues contribute to the function of the transcriptional inhibitory surface of SUMO2. If individual residues make different contributions, then combining multiple mutations should lead to more severe defects. We therefore compared the activities of select double, triple, or quadruple SUMO2 variants as noncleavable Gal4 DBD (in trans) or SC mutant GR fusions (in cis) using the same promoter contexts as in Fig. 3. As shown in the middle panel of Fig. 4, combining the T38A or K33A substitution with K42A led to a more severe defect than K42A alone (reference line) both in trans (Fig. 4a) and in cis (Fig. 4b). In the case of the positively charged residues, adding a third Ala substitution (K42A or R50A) to the K33/K35A double mutant or substitution of all four basic residues to Ala led to a modest further decrease in activity. This suggests that the progressive loss of the basic side chains leads to a cumulative defect. Interestingly, replacement of a single basic residue with an acidic one at position 42 (K42E) (reference line, bottom panels of Fig. 4) causes a comparable defect in the quadruple-Ala mutant. Combining this severe K42E variant with an alanine substitution at one of the nonbasic critical residues V30 or I34 leads to even further losses of inhibitory activity, comparable to the effect of Glu substitutions at both K42 and K33. Since SUMO2 has the potential to form polymeric chains through conjugation at a consensus SUMOylation site in its N-terminal tail (K11), the effect of the surface mutations might be partially masked by endogenous SUMOylation of the fusion proteins themselves. Disruption of the SUMOylation site (K11R) in the context of the K33/K42E double mutant, however, did not lead to substantial losses of activity either in trans or in cis (bottom bars in Fig. 4). This agrees with the lack of effect of this mutation on transcriptional inhibition by WT SUMO2 (20). Taken together, the results indicate that both the neutral and positively charged residues we have identified cooperate to mediate the in-cis and in-trans transcriptional inhibitory functions of SUMO2.

FIG. 4.

Compound mutations severely affect SUMO2 inhibition of GR-activated transcription in trans and in cis. (a) Effects of substitutions at multiple positions of SUMO2 on the ability of SUMO2-Gal4 fusions to inhibit SC mutant GR in trans at the pΔ(Gal)2(TAT)1-Luc reporter. (b) Effects of the same substitutions on the ability of SUMO2 to inhibit in cis when fused at the N terminus of SC mutant GR at the pΔTAT3-Luc reporter. Cells were treated with 10 nM dexamethasone and processed as described in Materials and Methods. The reference lines in the middle and bottom parts of each panel indicate the activities of the K42A and K42E mutations, respectively. The expression levels of the corresponding fusions were confirmed by Western blot detection of the HA epitope. In both panels a and b, the data represent the average ± SEM of at least three independent experiments performed in triplicate and are expressed as a percentage of SC mutant GR activity alone, which was 5.7 ± 0.57 and 222 ± 17 at pΔ(Gal)2(TAT)1-Luc and pΔ(TAT)3-Luc, respectively.

The functional defect is due to a loss of intrinsic transcriptional inhibition potential.

Direct recruitment of SUMO to promoters as Gal4 fusions leads to a dose-dependent inhibition of transcription driven by GR bound to either a single GRE or multiple GREs, but this inhibition requires multiple Gal4 sites (20). We therefore examined the effects of the severe K33E/K42E SUMO mutant on the ability of SUMO2-Gal4 DBD fusions to inhibit in two different promoter contexts. At the (Gal)2(TAT)1 reporter (Fig. 5a left), GR activity is relatively modest and unaffected by disruption of its SC/SUMOylation sites (open versus closed symbols). Expression of the WT SUMO2 fusion results in a profound, dose-dependent inhibition of GR activity. In contrast, the fusion to the mutant SUMO2 not only failed to inhibit but rather enhanced transcription. As in the case of a NEDD8-Gal4 fusion or the Gal4 DBD alone (20), this effect is likely due to the residual activation potential of these constructs and cooperation between the two Gal4 sites and the single GRE. Interestingly, the half-maximal dose of expression plasmid was the same for both inhibition (WT) and activation (mutant), implying that the effect of the mutations is not due to a simple loss of promoter occupancy. In addition, the dose of 30 ng used in previous experiments is clearly maximal since a 10-fold lower dose still produces nearly maximal functional effects despite dramatic reductions in expression levels by Western blotting (not shown). Thus, the slight variations in expression of the SUMO-Gal4 fusions observed in our experiments are unlikely to account for the functional differences observed. At the (Gal)2(TAT)3 promoter, GR activity is substantially greater than from a single site and disruption of its SC/SUMOylation motifs leads to a more-than-threefold enhancement of activity (Fig. 5a, right). Recruitment of WT SUMO2 leads to a dose-dependent reduction in transcription reaching 57% for both SC-deficient (open symbols) and WT (closed symbols) forms of GR. Titration of the K33E/K42E mutant, however, led to only a minor inhibition of GR activity. The stronger effects of the SUMO fusions at the (Gal)2(TAT)1 compared to the (Gal)2(TAT)3 promoter likely reflects the relative ratio of SUMO versus GR molecules recruited to the promoter. We also extended this analysis to the in-cis SUMO-GR fusion context and tested the activity of SC mutant GR alone or its fusions to noncleavable forms of WT or K33E/K42E SUMO2 at promoters harboring a single GRE or three GREs. As shown in Fig. 5b, left, all GR-SUMO fusions, as well as intact WT and SC mutant GR, showed nearly comparable activities from a single GR binding site. This is consistent with our previous results that indicate a strong requirement for multiple DNA binding sites to observe SUMO-dependent inhibition (20). In contrast, at a promoter harboring three GREs, disruption of the SC/SUMOylation motifs in GR leads to a substantial enhancement of activity (Fig. 5b, right, open squares) and this effect is essentially reversed by fusing WT SUMO2 to the SC-deficient GR (open triangles). In contrast, fusion of the K33E/K42E mutant is much less effective (open diamonds). Taken together, these results indicate that disruption of the SUMO surface we have identified leads to a loss in its intrinsic repressive power.

FIG. 5.

Disruption of the transcriptional regulatory surface of SUMO2 affects inhibition at multiple doses and promoter contexts. (a) Cells were transfected with expression vectors for WT (shaded symbols) or SC mutant (open symbols) GR and the indicated amounts of expression vectors for a Gal4 DBD fusion to either HA-tagged NEDD8 (squares), WT SUMO2 (triangles), or a SUMO2 K33E/K42E mutant (diamonds). The reporter plasmids were pΔ(Gal)2(TAT)1-Luc (left) and pΔ(Gal)2(TAT)3-Luc (right). (b) Cells were transfected with the indicated amounts of p6R-based vectors for the expression of WT GR (shaded circles), SC mutant GR (open squares), or SC mutant GR fused to WT SUMO2 (open triangles) or a SUMO2 K33E/K42E mutant (open diamonds). The reporter plasmids used were pΔTAT1-Luc (left) and pΔTAT3-Luc (right). In both panels a and b, the data represent the average ± SEM of at least three independent experiments performed in triplicate and are expressed as a percentage of SC mutant GR activity alone as follows: pΔ(Gal)2(TAT)1-Luc, 10.8 ± 1.4; pΔ(Gal)2(TAT)3-Luc, 799 ± 100; pΔ(TAT)1-Luc, 3.3 ± 0.2; pΔ(TAT)3-Luc, 471 ± 24.

The key regulatory surface is conserved in SUMO1 and is required for inhibition of multiple activators.

Although SUMO1 shares only 48% identity with SUMO2 and lacks an N-terminal SUMOylation site, both paralogues appear to play overlapping roles in various cellular functions, including transcriptional repression. Of the seven functional residues in SUMO2, all four basic residues and T38 are identical in SUMO1 and V30 and I34 are Ile and Val residues, respectively, in SUMO1 (Fig. 1). Alanine substitutions at the conserved residues in SUMO1 led to losses of inhibitory activity in both the in-trans and in-cis contexts that parallel the effects on SUMO2 (Fig. 6). The comparatively more severe effect of the mutations on SUMO1 function may be a reflection of the weaker overall inhibition by SUMO1 compared to SUMO2 (20). These data indicate that both SUMO isoforms utilize a structurally similar surface to mediate their transcriptional inhibitory properties. SUMO modification plays a crucial role in attenuating the transcriptional activity of many different sequence-specific factors and could act through multiple mechanisms. We therefore tested whether the functional surface that we have identified by examining effects on GR is also essential for inhibition in other contexts. To this end, we analyzed the abilities of Gal4 DBD fusions to WT and K33E/K42E SUMO2 to inhibit C/EBPα or the AR in trans, as well as the chimeric activator Gal4(VP16)2 in cis. As shown in Fig. 7, recruitment of WT SUMO2 inhibited C/EBPα- and AR-activated transcription in trans to 30 and 50% of the control, respectively, whereas activity remained at 80% for the K33E/K42E mutant and was unaffected by the fusion to NEDD8. In the in-cis context, fusing WT SUMO2 to Gal4-VP16 effectively reduced its activity to 20% whereas inhibition by the mutant SUMO is negligible. Thus, the surface we have identified plays a central role in SUMO-mediated transcriptional inhibition in multiple contexts.

FIG. 6.

Residues implicated in SUMO2-mediated transcriptional repression are functionally conserved in SUMO1. (a) Comparison of the effects of mutations at homologous positions of SUMO1 and SUMO2 on the ability of the corresponding HA-SUMO Gal4 fusions to inhibit SC mutant GR in trans at the pΔ(Gal)2(TAT)1-Luc reporter. (b) Effects of the same mutations on the ability of SUMO1 or -2 to inhibit transcription in cis when fused at the N terminus of SC mutant GR at the pΔTAT3-Luc reporter. In each panel, the data represent the average ± SEM of at least three independent experiments performed in triplicate and are expressed as a percentage of SC mutant GR activity alone either at pΔ(Gal)2(TAT)1-Luc (8.4 ± 1.9) or pΔ(TAT)3-Luc (326 ± 37), respectively.

Mutations that disrupt transcriptional inhibition preserve other functions of SUMO.

SUMO is a small protein, yet it interacts with multiple proteins during its processing and multiple rounds of activation, conjugation to target proteins, and release. In addition, SUMO is likely to regulate modified proteins by interacting with additional effector molecules. Given its size, some of the same structural features may be used for multiple interactions or be required for structural integrity. We therefore examined whether disruption of the transcriptional inhibitory surface of SUMO altered other steps of the SUMOylation pathway. SUMO is deconjugated from target proteins through the action of a set of specific isopeptidases. The same enzymes can also act as endopeptidases during the initial processing of newly translated SUMO and cleave residues downstream of the conserved Gly-Gly motif to generate the mature C terminus of SUMO. A fusion protein bearing the Gal4 DBD at the C terminus of SUMO2 lacking this motif is resistant to cleavage in vivo, whereas fusions that retain this Gly-Gly motif are efficiently processed (Fig. 8a). This reaction is unaffected in the case of single or double SUMO2 mutants that severely impair transcriptional inhibition. In contrast, an Arg-to-Ala substitution at position 59 which does not affect transcription (Fig. 1) impairs processing significantly (Fig. 8a). This conserved residue is in the opposite or back face of SUMO relative to the transcriptional inhibitory surface within a region predicted to form part of the protease interface (Fig. 2) based on the X-ray structure of the SENP2 protease with SUMO1 (36). In addition, disruption of the transcriptional inhibitory surface of SUMO does not impair its noncovalent binding to the SUMO-specific E2 UBC9 in vitro (Fig. 8b). Residues in SUMO involved in this interaction are highly conserved and also map to the back face of SUMO (Fig. 2). In order to examine the conjugation ability of these SUMO2 mutants downstream from the processing maturation event, a mature form (GG stop) was expressed in vivo. The pattern of SUMO-modified proteins in cells expressing WT or transcriptionally defective mutants is very similar (Fig. 8c). Only the K33E/K42E double mutant shows a minor reduction in conjugation levels. Taken together, these results indicate that the mutations we have identified specifically disrupt the transcriptional inhibitory properties of SUMO but largely preserve other basic functions. This implies that the transcriptional defect is not simply due to a disruption of the overall structural integrity of SUMO.

FIG. 8.

SUMO2 mutants compromised for inhibition are still active for processing and conjugation. (a) The indicated HA-SUMO2 fusions to the Gal4 DBD harboring (+) or lacking (−) the Gly-Gly (GG) motif in the junction between the SUMO2 C terminus (term) and the Gal4 DBD were expressed by transfection into CV-1 cells and tested for processing. Total cell lysates were resolved by SDS-PAGE, and the parental and processed forms were detected by immunoblotting for the HA epitope. (b) In vitro-translated and 35S-labeled SUMO2 proteins lacking the N-terminal SUMOylation site (Δ1-16) alone or in conjunction with the K33E/K42E mutations were tested for interactions with immobilized Ubc9 in a GST pulldown assay as described in Materials and Methods. (c) Pattern of SUMO conjugates in cells expressing HA-tagged and preprocessed (GG stop) WT or mutant (K33E/K42E) SUMO2. Total cell lysates were resolved by SDS-PAGE, and SUMO conjugates were detected by immunoblotting for the HA epitope. Schematic representations of the various SUMO forms used for each experiment are shown. The positions and molecular masses (in kilodaltons) of standards are shown.

DISCUSSION

A distinct surface in SUMO is essential for transcriptional inhibition.

Through a detailed functional characterization, we have examined the role of surface residues in SUMO during transcriptional inhibition and identified a conserved cluster of amino acids along the end of the second β sheet and the following α helix of SUMO. Mutations within this region lead to loss of inhibition without major effects on other functions. As demonstrated for ubiquitin (48), these essential residues are likely to be part of an interaction surface with the corepressors that mediate the inhibitory properties of SUMO, such as the synergy control factor(s) that we have proposed (23). This inhibitory surface is located in the upper sector of the front face of SUMO. In contrast, residues important for E1, E2, and protease binding in SUMO and other Ubl proteins emerge from secondary-structure elements in the back face and C-terminal tail (21, 32, 33, 36) (Fig. 2). This arrangement of the critical residues for inhibition is consistent with a surface serving a more derived, class-specific function acquired after the ancestral conjugation and deconjugation functions of the Ubl family had been established. Our data support this segregation of functional surfaces, as mutants defective for inhibition still preserve processing, Ubc9 binding, and overall conjugation capability. The mildly reduced conjugation observed in the severe K33E/K42E double mutant could be due to alterations in the interaction with other components of the SUMOylation pathway, and this issue remains to be fully explored. Consistent with our functional data, the critical region is unique to SUMO and its character is quite different in other Ubl proteins (NEDD8, ubiquitin) that do not display the transcriptional inhibitory effects of SUMO (Fig. 1). In contrast to other surface residues, the critical amino acids are highly conserved across a wide spectrum of eukaryotic groups, including plants, invertebrates, protists, and fungi (Fig. 2). In fact, a fusion of SMT3, the Saccharomyces cerevisiae homolog, to Gal4 is the most effective SUMO isoform we have tested for transcriptional inhibition (data not shown). Thus, it is likely that effects that rely on this conserved surface, such as transcriptional inhibition, are important functions of SUMO across eukaryotes.

Structural basis for SUMO-dependent interactions.

Our mutagenesis efforts were guided by a homology model of SUMO2. Fortunately, during the preparation of this report, the X-ray crystallographic structure of SUMO2 became available (22), allowing a direct structural interpretation of our functional data and comparison of the inhibitory surface in three different crystal structures corresponding to SUMO2, SUMO1, and SMT3 (Fig. 9). In the SUMO2 crystal structure, the combined solvent-accessible surface delineated by the critical residues is relatively small, approximately 720 square angstroms. The four important basic residues (K33, K35, K42, and R50) extend into the solvent and form four parallel, positively capped prongs arranged in a rectangular shape and separated by approximately 4.5 Å. This spacing would accommodate an extended peptide loop or β sheet but is unlikely to accept an α helix without substantial reorientation. The other three functionally relevant residues (V30, I34, and T38) form the textured base of the cavity. Notably, the conserved T38 (yellow in Fig. 9) caps one of the ends of the cavity with the hydroxyl group facing inward, suggesting that this residue may hydrogen bond with SUMO targets. The functional importance of the four highly exposed basic residues clearly suggests that electrostatic interactions with acidic or hydrogen bond partners in the interacting protein are likely to play an important role in the binding of corepressors. The severity of the K33E/K42E mutant may be due to the disruption of such interactions or, alternatively, could arise from the formation of intramolecular salt bridges with the remaining basic residues and closure of the surface. The fact that Lys or Arg residues are essentially equivalent at these positions argues against a role for posttranslational modification as in the case of K48 and K33 poly-ubiquitin chain formation. In the recently described SUMO4, a proline occupies the position of R50 of SUMO2. This tissue-restricted isoform may therefore be a weaker transcriptional inhibitor. Conversely, it is also possible that the local structure is altered and that the basic function is provided by the arginine residue immediately downstream of the Pro in this isoform.

FIG. 9.

Structural comparison of the repression surface in SUMO1, SUMO2, and SMT3. Front (a) and side (b) views of the transcriptional repression surface in the crystal structures of SUMO2 (left), SUMO1 (center), and SMT3 (right) are shown. The solvent-accessible surface defined by critical functional residues is shown superimposed on the ribbon diagram of each protein. The calculated electrostatic potential is mapped onto each surface, the region occupied by the critical threonine residue (T38 in SUMO2) is shown in yellow, and the position of the hydrophobic hole is outlined with dashed lines. In the side view, the threonine residue is absent to highlight the similar parallel spacing but differing orientation of the critical basic residues in SUMO1 and -2.

The general architecture of this inhibitory surface is conserved in the other crystal structures (Fig. 9). In SUMO1, the side chains of the basic residues are parallel and although their orientation is shifted substantially, they are separated by the same distance as in SUMO2. In the case of yeast SMT3, the cavity between the basic residues is more open due to a substantial reorientation of the first two critical basic residues (Fig. 9B, right), leading to a splayed orientation of the basic residues. This region may thus be dynamic and could alternate between closed and open configurations in order to capture the cognate target.

In SUMO2, The hydrophobic character of the aliphatic portions of the basic residues, as well as that of V30 and I34, also suggests an important role for Van der Waals contacts with SUMO targets. The orientation of I34 creates a shallow hydrophobic hole in the center of the cavity. Interestingly, in SUMO1, the side chains at these two critical positions are reversed (I34, V38). This alteration creates a substantially deeper hole and shifts its position away from the center and toward the conserved threonine residue (yellow in Fig. 9). Since other critical residues are conserved between SUMO isoforms, differences in the shape of the cavity and hole lined by these branched aliphatic residues may contribute to the lower intrinsic repression potential of SUMO1 compared to SUMO2/3 (20).

The results from our structural and functional characterization of SUMO also agree with very recent nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) data from several proteins defining the sequence V/I-X-V/I-V/I as a SUMO interaction motif (45), especially since the NMR perturbation analysis also implicates a region in SUMO similar to the one described here. The branched aliphatic residues in this motif are likely to interact with the aliphatic portions of the basic residues, as well as the texture and hole created by the critical Val 30 and Ile 34 residues we have identified. Moreover, in the SUMO-interacting peptides characterized by Song et al., the hydrophobic residues are flanked by multiple negatively charged residues (45). One or more of these residues most likely are involved in interactions with the important basic residues we have identified, especially K42. Although Song et al. argue for a dominant role for the hydrophobic residues in the SUMO-interacting peptides, it is likely that the electrostatic interactions are critical as well. The somewhat less dramatic effects of the individual alanine substitutions of acidic residues detected by Song et al. may be due to redundancy between multiple electrostatic interactions. Conversely, this could be due to the fact that the mutations tested by Song et al. at the hydrophobic residues (introduction of charge) are much more disruptive than the ones examined at the acidic residues (alanine substitutions) (45).

Implications for SUMO-dependent transcriptional inhibition.

Promoter recruitment of SUMO can directly inhibit transcription emanating from the modified factors themselves, as well as from nearby bound activators as long as multiple SUMO moieties are independently bound to the DNA (20). We have proposed that the requirement for multiple independent contacts with the DNA for SUMO-mediated inhibition may be due to a weak interaction between SUMO and its corepressor(s). The low micromolar affinities for SUMO-interacting peptides reported by Song et al. (45) or between ubiquitin and ubiquitin binding motifs (18), together with the small area of the surface we identified, are consistent with this proposal. The ability to inhibit many different activators also suggests that inhibition may target a common step in promoter activation or clearing. It remains unclear, however, whether the influence of this inhibitory surface in SUMO is long range or only limited to the local DNA environment of the modified factor. Certain histone deacetylase family members and other proteins have been implicated in SUMO-dependent repression (12, 24, 54), and the direct mediators of this inhibition are likely to vary in different contexts. Nevertheless, the consistent effect of the disrupting mutations indicates that they utilize the same or very similar determinants in SUMO. As a first step, a comparative analysis of histone deacetylase interactions with WT and mutant SUMO2 is currently under way in our laboratory. The critical region that we have identified on the basis of its transcriptional effects is also likely to participate in other functions of SUMO, as in the case of ubiquitin, where overlapping surfaces centered around I44 engage in contacts with multiple ubiquitin binding domains (2, 26, 48, 49). The recent SUMO interaction studies by NMR (45) showing that this region can bind peptides derived from multiple proteins, including SUMO E3 enzymes, also support this view. Some of these proteins may thus be involved in SUMO-dependent transcriptional inhibition, as well as in enhancing conjugation. Given that SUMO binding proteins possess many different activities, defining the structural and functional rules that determine their specificity of interaction with the multiple SUMO isoforms will be essential to understanding the role they play both in transcriptional inhibition and in the other cellular processes regulated by SUMOylation. The definition of an effector surface in SUMO is an important step in this direction.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by U.S. Public Health Service grants DK61656-01 and NIH P60 DK20572. L. Subramanian acknowledges support from the American Heart Association (0225755Z).

REFERENCES

- 1.Abdel-Hafiz, H., G. S. Takimoto, L. Tung, and K. B. Horwitz. 2002. The inhibitory function in human progesterone receptor N termini binds SUMO-1 protein to regulate autoinhibition and transrepression. J. Biol. Chem. 277:33950-33956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alam, S. L., J. Sun, M. Payne, B. D. Welch, B. K. Blake, D. R. Davis, H. H. Meyer, S. D. Emr, and W. I. Sundquist. 2004. Ubiquitin interactions of NZF zinc fingers. EMBO J. 23:1411-1421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bailey, D., and P. O'Hare. 2004. Characterization of the localization and proteolytic activity of the SUMO-specific protease, SENP1. J. Biol. Chem. 279:692-703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bies, J., J. Markus, and L. Wolff. 2002. Covalent attachment of the SUMO-1 protein to the negative regulatory domain of the c-Myb transcription factor modifies its stability and transactivation capacity. J. Biol. Chem. 277:8999-9009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bohren, K. M., V. Nadkarni, J. H. Song, K. H. Gabbay, and D. Owerbach. 2004. A M55V Polymorphism in a novel SUMO gene (SUMO-4) differentially activates heat shock transcription factors and is associated with susceptibility to type I diabetes mellitus. J. Biol. Chem. 279:27233-27238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carey, M. 1998. The enhanceosome and transcriptional synergy. Cell 92:5-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chun, T. H., H. Itoh, L. Subramanian, J. A. Iñiguez-Lluhí, and K. Nakao. 2003. Modification of GATA-2 transcriptional activity in endothelial cells by the SUMO E3 ligase PIASy. Circ. Res. 92:1201-1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.David, G., M. A. Neptune, and R. A. DePinho. 2002. SUMO-1 modification of histone deacetylase 1 (HDAC1) modulates its biological activities. J. Biol. Chem. 277:23658-23663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davidson, E. H., D. R. McClay, and L. Hood. 2003. Regulatory gene networks and the properties of the developmental process. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:1475-1480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Desterro, J. M., J. Thomson, and R. T. Hay. 1997. Ubch9 conjugates SUMO but not ubiquitin. FEBS Lett. 417:297-300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fraczkiewicz, R., and W. Braun. 1998. Exact and efficient analytical calculation of the accessible surface areas and their gradients for macromolecules. J. Comp. Chem. 19:319-333. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Girdwood, D., D. Bumpass, O. A. Vaughan, A. Thain, L. A. Anderson, A. W. Snowden, E. Garcia-Wilson, N. D. Perkins, and R. T. Hay. 2003. P300 transcriptional repression is mediated by SUMO modification. Mol. Cell 11:1043-1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Glaser, F., T. Pupko, I. Paz, R. E. Bell, D. Bechor-Shental, E. Martz, and N. Ben-Tal. 2003. ConSurf: identification of functional regions in proteins by surface-mapping of phylogenetic information. Bioinformatics 19:163-164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gong, L., B. Li, S. Millas, and E. T. Yeh. 1999. Molecular cloning and characterization of human AOS1 and UBA2, components of the sentrin-activating enzyme complex. FEBS Lett. 448:185-189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guex, N., and M. C. Peitsch. 1997. SWISS-MODEL and the Swiss-PdbViewer: an environment for comparative protein modeling. Electrophoresis 18:2714-2723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guo, D., M. Li, Y. Zhang, P. Yang, S. Eckenrode, D. Hopkins, W. Zheng, S. Purohit, R. H. Podolsky, A. Muir, J. Wang, Z. Dong, T. Brusko, M. Atkinson, P. Pozzilli, A. Zeidler, L. J. Raffel, C. O. Jacob, Y. Park, M. Serrano-Rios, M. T. Larrad, Z. Zhang, H. J. Garchon, J. F. Bach, J. I. Rotter, J. X. She, and C. Y. Wang. 2004. A functional variant of SUMO4, a new IκBα modifier, is associated with type 1 diabetes. Nat. Genet. 36:837-841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hang, J., and M. Dasso. 2002. Association of the human SUMO-1 protease SENP2 with the nuclear pore. J. Biol. Chem. 277:19961-19966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hicke, L., and R. Dunn. 2003. Regulation of membrane protein transport by ubiquitin and ubiquitin binding proteins. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 19:141-172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hirano, Y., S. Murata, K. Tanaka, M. Shimizu, and R. Sato. 2003. Sterol regulatory element-binding proteins are negatively regulated through SUMO-1 modification independent of the ubiquitin/26S proteasome pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 278:16809-16819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Holmstrom, S., M. E. Van Antwerp, and J. A. Iñiguez-Lluhí. 2003. Direct and distinguishable inhibitory roles for SUMO isoforms in the control of transcriptional synergy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:15758-15763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang, D. T., D. W. Miller, R. Mathew, R. Cassell, J. M. Holton, M. F. Roussel, and B. A. Schulman. 2004. A unique E1-E2 interaction required for optimal conjugation of the ubiquitin-like protein NEDD8. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 10:927-935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang, W. C., T. P. Ko, S. S. Li, and A. H. Wang. 2004. Crystal structures of the human SUMO-2 protein at 1.6 A and 1.2 A resolution: implication on the functional differences of SUMO proteins. Eur. J. Biochem. 271:4114-4122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Iñiguez-Lluhí, J. A., and D. Pearce. 2000. A common motif within the negative regulatory regions of multiple factors inhibits their transcriptional synergy. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:6040-6050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Johnson, E. S. 2004. Protein modification by SUMO. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 73:355-382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kahyo, T., T. Nishida, and H. Yasuda. 2001. Involvement of PIAS1 in the sumoylation of tumor suppressor p53. Mol. Cell 8:713-718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kang, R. S., C. M. Daniels, S. A. Francis, S. C. Shih, W. J. Salerno, L. Hicke, and I. Radhakrishnan. 2003. Solution structure of a CUE-ubiquitin complex reveals a conserved mode of ubiquitin binding. Cell 113:621-630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim, J., C. A. Cantwell, P. F. Johnson, C. M. Pfarr, and S. C. Williams. 2002. Transcriptional activity of CCAAT/enhancer-binding proteins is controlled by a conserved inhibitory domain that is a target for sumoylation. J. Biol. Chem. 277:38037-38044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim, K. I., S. H. Baek, Y. J. Jeon, S. Nishimori, T. Suzuki, S. Uchida, N. Shimbara, H. Saitoh, K. Tanaka, and C. H. Chung. 2000. A new SUMO-1-specific protease, SUSP1, that is highly expressed in reproductive organs. J. Biol. Chem. 275:14102-14106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kirsh, O., J. S. Seeler, A. Pichler, A. Gast, S. Muller, E. Miska, M. Mathieu, A. Harel-Bellan, T. Kouzarides, F. Melchior, and A. Dejean. 2002. The SUMO E3 ligase RanBP2 promotes modification of the HDAC4 deacetylase. EMBO J. 21:2682-2691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kotaja, N., U. Karvonen, O. A. Janne, and J. J. Palvimo. 2002. The nuclear receptor interaction domain of GRIP1 is modulated by covalent attachment of SUMO-1. J. Biol. Chem. 277:30283-30288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lin, X., B. Sun, M. Liang, Y. Y. Liang, A. Gast, J. Hildebrand, F. C. Brunicardi, F. Melchior, and X. H. Feng. 2003. Opposed regulation of corepressor CtBP by SUMOylation and PDZ binding. Mol. Cell 11:1389-1396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu, Q., C. Jin, X. Liao, Z. Shen, D. J. Chen, and Y. Chen. 1999. The binding interface between an E2 (UBC9) and a ubiquitin homologue (UBL1). J. Biol. Chem. 274:16979-16987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mossessova, E., and C. D. Lima. 2000. Ulp1-SUMO crystal structure and genetic analysis reveal conserved interactions and a regulatory element essential for cell growth in yeast. Mol. Cell 5:865-876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nishida, T., and H. Yasuda. 2002. PIAS1 and PIASxalpha function as SUMO-E3 ligases toward androgen receptor and repress androgen receptor-dependent transcription. J. Biol. Chem. 277:41311-41317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pichler, A., A. Gast, J. S. Seeler, A. Dejean, and F. Melchior. 2002. The nucleoporin RanBP2 has SUMO1 E3 ligase activity. Cell 108:109-120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reverter, D., and C. D. Lima. 2004. A basis for SUMO protease specificity provided by analysis of human Senp2 and a Senp2-SUMO complex. Structure 12:1519-1531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ross, S., J. L. Best, L. I. Zon, and G. Gill. 2002. SUMO-1 modification represses Sp3 transcriptional activation and modulates its subnuclear localization. Mol. Cell 10:831-842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Saitoh, H., and J. Hinchey. 2000. Functional heterogeneity of small ubiquitin-related protein modifiers SUMO-1 versus SUMO-2/3. J. Biol. Chem. 275:6252-6258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sapetschnig, A., G. Rischitor, H. Braun, A. Doll, M. Schergaut, F. Melchior, and G. Suske. 2002. Transcription factor Sp3 is silenced through SUMO modification by PIAS1. EMBO J. 21:5206-5215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sawano, A., and A. Miyawaki. 2000. Directed evolution of green fluorescent protein by a new versatile PCR strategy for site-directed and semi-random mutagenesis. Nucleic Acids Res. 28:E78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schmidt, D., and S. Muller. 2002. Members of the PIAS family act as SUMO ligases for c-Jun and p53 and repress p53 activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:2872-2877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Seeler, J. S., and A. Dejean. 2003. Nuclear and unclear functions of SUMO. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 4:690-699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shiio, Y., and R. N. Eisenman. 2003. Histone sumoylation is associated with transcriptional repression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:13225-13230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sloper-Mould, K. E., J. C. Jemc, C. M. Pickart, and L. Hicke. 2001. Distinct functional surface regions on ubiquitin. J. Biol. Chem. 276:30483-30489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Song, J., L. K. Durrin, T. A. Wilkinson, T. G. Krontiris, and Y. Chen. 2004. Identification of a SUMO-binding motif that recognizes SUMO-modified proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101:14373-14378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Su, H. L., and S. S. Li. 2002. Molecular features of human ubiquitin-like SUMO genes and their encoded proteins. Gene 296:65-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Subramanian, L., M. D. Benson, and J. A. Iñiguez-Lluhí. 2003. A synergy control motif within the attenuator domain of CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein alpha inhibits transcriptional synergy through its PIASy-enhanced modification by SUMO-1 or SUMO-3. J. Biol. Chem. 278:9134-9141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sundquist, W. I., H. L. Schubert, B. N. Kelly, G. C. Hill, J. M. Holton, and C. P. Hill. 2004. Ubiquitin recognition by the human TSG101 protein. Mol. Cell 13:783-789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Swanson, K. A., R. S. Kang, S. D. Stamenova, L. Hicke, and I. Radhakrishnan. 2003. Solution structure of Vps27 UIM-ubiquitin complex important for endosomal sorting and receptor downregulation. EMBO J. 22:4597-4606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tatham, M. H., E. Jaffray, O. A. Vaughan, J. M. Desterro, C. H. Botting, J. H. Naismith, and R. T. Hay. 2001. Polymeric chains of SUMO-2 and SUMO-3 are conjugated to protein substrates by SAE1/SAE2 and Ubc9. J. Biol. Chem. 276:35368-35374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tian, S., H. Poukka, J. J. Palvimo, and O. A. Janne. 2002. Small ubiquitin-related modifier-1 (SUMO-1) modification of the glucocorticoid receptor. Biochem. J. 367:907-911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Watts, F. Z. 2004. SUMO modification of proteins other than transcription factors. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 15:211-220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yamamoto, K. R., B. D. Darimont, R. L. Wagner, and J. A. Iñiguez-Lluhí. 1998. Building transcriptional regulatory complexes: signals and surfaces. Cold Spring Harbor Symp. Quant. Biol. 63:587-598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yang, S. H., and A. D. Sharrocks. 2004. SUMO promotes HDAC-mediated transcriptional repression. Mol. Cell 13:611-617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhong, S., S. Muller, S. Ronchetti, P. S. Freemont, A. Dejean, and P. P. Pandolfi. 2000. Role of SUMO-1-modified PML in nuclear body formation. Blood 95:2748-2752. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]