Abstract

Introduction

Bone cancer metastasis may produce severe and refractory pain. It is often difficult to manage with systemic analgesics. Chemical neurolysis may be an effective alternative in terminally ill patients.

Case report

Female terminally ill patient with hip metastasis of gastric cancer in severe pain. Neurolytic ultrasound-guided blocks of the pericapsular nerve group and obturator nerve were performed with 5% phenol. This led to satisfactory pain relief for 10 days, until the patient's death.

Discussion

This approach may be effective and safe as an analgesic option for refractory hip pain due to metastasis or pathologic fracture in terminally ill patients.

Keywords: Regional anesthesia, Pain management, Chemical neurolysis, Hip, Metastasis

Introduction

Hip pain is a common and disabling condition in adults. Its incidence is 12...15% among adults over 60 years of age.1 The most frequent causes are osteoarthritis, labral tears, synovitis, osteonecrosis, and greater trochanteric pain syndrome. Other conditions, such as septic arthritis, aortoiliac insufficiency, and bone tumors (primary or metastasis), are less common but raise concern. Bones are the third most frequent site of cancer metastasis, following the lungs and liver. Bone metastasis usually indicate advanced stage disease and poor prognosis. They are major causes of morbidity causing severe and refractory pain, pathologic fractures, impaired mobility, and spinal cord injuries. The treatment of bone cancer pain involves multiple approaches, including pharmacotherapy, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, bisphosphonates, calcitonin, and neural blockades.2 Interventional procedures may be an alternative in refractory cases. Neurolytic block may be a potential option.

We present a case report of a gastric cancer patient who presented bone metastasis in the right femoral head, leading to severe refractory pain, with serious functionality and quality of life impairment. The patient was treated using a neurolytic block of the right pericapsular nerve group and the obturator nerve, resulting in satisfactory analgesia until her death 10 days later. Written informed consent to publication was obtained from the patient.

Case report

This article adheres to the applicable Enhancing the Quality and Transparency of Health Research checklist (Case Report Guidelines, CARE). The patient was female, 49 years of age, weighed 68 kg, and had a height of 159 cm. She had recently been diagnosed with a signet ring cell carcinoma of the stomach with bone metastasis, one of which was situated in the right femoral head. She had no other comorbidities, but her tumor was already untreatable and she was on palliative care. At the time, her symptoms were related to uncontrolled pain due to the osteolytic lesions, mainly in the right hip.

The patient had severe pain with a Numeric Verbal Scale (NVS) score of 10 (the NVS varies from 0 to 10, in which 0 indicates the absence of pain and 10 means unbearable pain) in the first evaluation. She was unable to sit or stand up because of the pain. She felt a slight relief with morphine rescue analgesia. Her prescription included the following medications: intravenous (IV) dipyrone 2 g 6/6 h, transdermal (TD) fentanyl patch 50 mcg.h...1, IV morphine 4 mg 4/4 h when necessary (pro re nata, PRN) (mean daily dose of 8 mg.day...1), IV ketamine 0.15 mg.kg...1.h...1 in continuous infusion, and per os (PO) cyclobenzaprine 5 mg 8/8 h. After explaining the therapy options, possible adverse effects, and possible benefits to the patient, and after receiving her informed consent, a neurolytic block with 5% phenol was performed on the articular branches of the right femoral nerve and of the right obturator nerve in an attempt to control the pain.

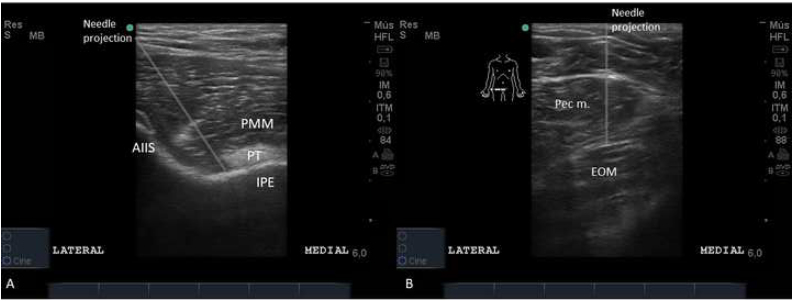

The procedure was performed in the operating room with the patient in the supine position. The right hip region was cleaned with antiseptic solution and covered with sterile drapes. A high-frequency linear ultrasound probe was placed over the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS), then slid caudally until the anterior inferior iliac spine (AIIS) was visualized. Then, the probe was positioned aligning the AIIS to iliopubic eminence.3 A 20G 90-mm Quincke needle was inserted in-plane lateral to medial until the tip made contact with the bone, right beneath the iliopsoas muscle tendon. After negative aspiration, 4 mL of 5% phenol was injected (Fig. 1A). Then, the probe was slid medially over the superior pubic ramus towards the pubic tubercle. At that point, the transducer was slid caudally until an image of the pectineus and external obturator muscles formed.4 The needle was introduced in an out-of-plane approach until its tip was located in the plane between the pectineus and external obturator muscles. Then, 3 mL of the 5% phenol was injected after negative aspiration.

Figure 1.

A, Pericapsular nerve group neurolytic block; B, Obturator nerve neurolytic block. AIIS, anterior inferior iliac spine; EOM, external obturator muscle; IPE, iliopubic eminence; Pec m., pectineus muscle; PMM, psoas major muscle; PT, psoas tendon.

Before the procedure, the patient noted a NVS pain score of 5 at rest and a NVS pain score of 10 during movement. Immediately after the procedure, a NVS score of 1 and 90% pain relief was reported by the patient. The day after the procedure, the patient had no pain at all. On subsequent days, the patient had no pain and reduced her opioid consumption, as summarized in Table 1. The patient died on the 10th post-neurolysis day. Until her death, she had no complaints of any decrease in muscle strength of the right lower limb.

Table 1.

Summary of post-procedure pain management evolution of the patient.

| Opioid consumption in oral morphine equivalent (mg) | NVS at rest | NVS at movement | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-procedure | 144 | 5 | 10 |

| 1st post-procedure day | 132 | 0 | 1 |

| 2nd post-procedure day | 132 | 0 | 0 |

| 3rd post-procedure day | 120 | 0 | 0 |

| 4th post-procedure day | 132 | 0 | 0 |

| 5th post-procedure day | 120 | 0 | 0 |

| 6th post-procedure day | 120 | 0 | 0 |

| 7th post-procedure day | 41 | 0 | 0 |

| 8th post-procedure day | 138 | 0 | 0 |

| 9th post-procedure day | 78 | 0 | 0 |

Discussion

Pericapsular nerve group and obturator nerve phenol neurolysis in this patient led to a remarkable decrease in her pain scores. The intensity of the hip pain was drastically reduced, with no apparent side effects (motor weakness). As she was under palliative care, pain control was a priority, and the procedure gave her comfort until her death 10 days later.

Hip pain is frequent among adults above the age of 65 years due to a variety of causes and has been shown to be a relevant area in which improved pain treatment is needed. Bone metastasis can cause chronic and disabling pain. Its management can be challenging due to a patient's critical condition and the adverse effects of opioids and other analgesic medications. Once comfort is imperative in patients under palliative care, pain control is usually a high priority.

Hip denervation can be used as an alternative for refractory pain. It can be performed by percutaneous radiofrequency denervation or chemical neurolysis.5, 6 These procedures may provide satisfactory analgesia, but information about the long-term effects or possible complications is still lacking. Although articular branches are sensory nerves, it is important to bear in mind that obturator and femoral nerves are mixed nerves, and great care to avoid motor injury has to be taken while performing both blocks. Considering the terminal conditions of the patient in our case, it was decided that 5% phenol neurolysis of the articular branches of femoral and obturator nerves could benefit her and reduce her disabilities. To our knowledge, this approach is relatively innovative, and it had successful individual results in this case, allowing the patient to sit or stand, leading to improved quality of life during the patient's final days. Phenol was the agent of choice because its injection is less painful than 99% ethanol, and larger volumes were not necessary for the proposed procedure. The concentration of 5% was used because it is the highest phenol formulation available in our institution.

This case report, although describes a relatively good result, has several limitations. First of all, one single case description cannot be taken as a general and appliable method to other patients. This patient was in a severe condition, with very low status performance, and limited to bed most of the time. As she was not considerably mobilizing, it was not 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 possible to adequately evaluate any motor blocks to her lower limb. The follow-up time can also put some limitation on the long-term assessment. As the patient passed away after 10 days, it was not possible to check for how long the chemical neurolysis kept the analgesic effect.

This case report may suggest that the articular branches of the femoral and obturator nerves may be good targets for chemical neurolysis (with phenol or ethanol injection) for hip pain management when intending long-term analgesic effect. Chemical neurolysis may be an easier and low-cost modality of hip pain treatment compared to hip denervation by radiofrequency ablation. Of course, this is a case report about a patient under palliative care. Larger studies with long-term follow-up, including randomized controlled trials assessing this technique in end-of-life patients, or even in non-cancer patients (hip osteoarthritis, for example), may be of interest to certify chemical neurolysis of the hip articular branches as a therapeutic option in hip pain treatment.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank the colleagues of the Oncology and Palliative Care teams, who trusted and accepted the Pain Management Team suggestions and treatment options.

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.bjane.2021.02.037.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

References

- 1.Christmas C., Crespo C.J., Franckowiak S.C., et al. How common is hip pain among older adults? results from the third national health and nutrition examination survey. J Fam Pract. 2002;51:345–348. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mantyh P.W. Bone cancer pain: from mechanism to therapy. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2014;8:83–90. doi: 10.1097/SPC.0000000000000048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Giron-Arango L., Peng P.W.H., Chin K.J., et al. Pericapsular Nerve Group (PENG) block for hip fracture. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2018;43:859–863. doi: 10.1097/AAP.0000000000000847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nielsen T.D., Moriggl B., Soballe K., et al. A cadaveric study of ultrasound-guided subpectineal injectate spread around the obturator nerve and its hip articular branches. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2017;42:357–361. doi: 10.1097/AAP.0000000000000587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kwun-Tung Ng T., Chan W.S., Peng P.W.H., et al. Chemical hip denervation for inoperable hip fracture. Anesth Analg. 2020;130:498–504. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000004172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rocha Romero A., Carvajal Valdy G., Lemus A.J. Ultrasound-guided pericapsular nerve group (PENG) hip joint phenol neurolysis for palliative pain. Can J Anaesth. 2019;66:1270–1271. doi: 10.1007/s12630-019-01448-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.