ABSTRACT

Background

Previous studies have examined social media habits and utilization patterns among various groups of healthcare professionals. However, very few studies have evaluated the use of social media to support continuing professional development activities. The goal of the 2023 Clinical Education Alliance social media survey was to explore how HCPs interact professionally with social media, describe utilization trends, and identify barriers to using social media to disseminate CPD content.

Methods

We conducted an online anonymous, voluntary survey of healthcare professionals contained in the Clinical Education Alliance learner database from January to March 2023. The survey was distributed via email and all learners were invited to participate regardless of profession or specialty. This survey consisted of 16 questions and collected demographic information and social media utilization and habits of healthcare professionals.

Results

Of the 2,615 healthcare professionals who completed the survey, 71.2% use social media. Most respondents were physicians (50.6%) practicing in an urban setting (59.6%) and have been practicing for more than 15 years (70.5%). The most widely used platform was Facebook (70.7%), but there were no significant differences among the different professions. Of the respondents who use social media, 44.5% used social media to access continuing professional development-certified activities. Surveyed learners preferred passive participation with social media content. Participant-reported concerns include issues with legitimacy of the information, privacy, time constraints, and institutional barriers.

Discussion

As the continuing professional development community continues to evolve and seek new innovative strategies to reach healthcare professionals, the findings of this survey highlight the need to identify and enact social media-based strategies aimed to engage healthcare professionals and provide them with unbiased evidence-based education.

KEYWORDS: Healthcare education, continuing professional development, social media, HCP survey, accredited education

Introduction

In the ever-changing digital landscape, social media has evolved into a dynamic environment, empowering users to create, share, and engage with a wide range of content and interactions. These platforms encompass collaborative environments, social networks, microblogging sites, and content-centered hubs, offering diverse opportunities for meaningful online engagement [1,2]. Traditionally viewed as a platform by which one can share about their personal life, social media has become a powerful asset for today’s healthcare community [3]. Healthcare professionals (HCPs) routinely engage with social media for a myriad of activities, ranging from connecting with peers and participating in online discussions to accessing the latest medical information [4]. Numerous companies and organizations have shifted their focus to using social media to disseminate medical information, albeit to varying success [1,5,6]. Academic journals have begun to leverage social media to attract readers to their materials [7]. The communication capabilities provided by social media has led to its implementation in healthcare education curricula. Recent surveys show a growing number of pharmacy and nursing programs using social media to improve students’ education experience [8,9]. Multiple physician residency programs report using social media to increase engagement over journal articles [10]. Similarly, the use of social media by healthcare educators and learners is evolving. Individuals are no longer solely consumers of content; they also leverage social media to share medical education [8,11]. One potential area of HCP education that may benefit from the implementation of social media is continuing professional development. While continuing professional development (CPD) can be a broadly defined learning path, the American Council for Pharmacy Education defines as ‘a self-directed, ongoing, systematic and outcomes focused approach to lifelong learning that is applied into practice’ [12]. This shift creates opportunities for all facets the Continuing Professional Development (CPD) industry to engage with HCP audiences through social media.

The social media habits of HCPs vary significantly from individual to individual. Previous studies have examined social media habits and utilization patterns among various groups of healthcare professionals [4,13–16]. For example, a survey of 485 physicians found almost 58% of respondents positively viewed social media with the main factors influencing their use being usefulness and ease of use [17]. Pharmacists’ usage of social media has been low when compared to other HCPs and limited to personal and social intentions. When used professionally, pharmacists tend to use social media to access and share information among peers [18]. However, very few studies have evaluated the use of social media to support CPD activities. Recognizing the widespread presence of social media in the lives of HCPs, the importance of researching its incorporation into CPD activities is evermore emphasized. This research is crucial for identifying optimal approaches and assessing the impact of social media on the effectiveness of CPD activities. In light of this, the 2023 Clinical Education Alliance social media survey aims to discern how HCPs interact with social media, explore emerging utilization trends, and distinguish concerns unique to specific professions. The findings of this survey can be used to identify the value of using social media to enhance CPD programs.

Methods

Clinical Education Alliance (CEA) conducted an anonymous web-based survey designed to capture the various ways in which HCPs interact with social media content. The survey was created using SurveyMonkey and influenced by two prior surveys distributed in the past 10 years. The survey was reviewed by two of the authors (AP, SN) for clarity and ease of completion. The final survey was distributed via email to all learners within our database between January and March 2023. This database consists of all learners who have created a learner profile with CEA and have interacted with at least one CEA educational activity. All learners listed in the CEA database were eligible to participate.

The survey consisted of 16 questions separated into three clusters. The first cluster of questions aimed to gather participant demographic details, such as profession, specialty, and experience The second cluster of questions explored aspects of social media usage, such as types of platforms used, the manner in which social media is used in a professional setting, and preferences regarding content formats. The last cluster of questions inquired about social media habits in terms of when they access content, their frequency of use per week, and their perception of the credibility of medical information found on social media.

Demographic information was collected from all participants who completed the survey. Answering all questions was not required to complete the survey. Unanswered questions were labeled as missing and were not included in the final analysis. Categorical variables are depicted using numbers and percentages. Group comparisons of categorical variables were performed using χ2 tests. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 29.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). p values < .05 were deemed to be statistically significant. This study was found to be exempt by an Institutional Research Review Board.

Results

Survey responses were collected between January 2023 and March 2023. Due to the nature of the survey methodology, we cannot calculate a response rate; however the total number of respondents is 2,615. A breakdown of the respondents’ demographics can be found in Table 1. The majority of respondents were physicians (50.6%) and have been practicing for more than 15 years (70.5%). Most respondents reported they practiced in an urban area (59.6%).

Table 1.

General participant demographics of the 2023 CEA survey.

| n | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Profession | Advanced practice providera | 335 | 12.8 |

| Nurse | 340 | 13.0 | |

| Pharmacist | 274 | 10.5 | |

| Physician | 1322 | 50.6 | |

| Otherb | 344 | 13.1 | |

| Specialtyc | Nonsurgical specialties | 2418 | 92.4 |

| Supporting specialties | 107 | 4 | |

| Surgical specialties | 90 | 3.4 | |

| Experience | 1–5 years | 226 | 8.6 |

| 6–15 years | 546 | 20.9 | |

| More than 15 years | 1843 | 70.5 | |

| Practice setting | Urban | 1559 | 59.6 |

| Suburban | 734 | 28.1 | |

| Rural | 322 | 12.3 | |

| Use social media | Yes | 1862 | 71.2 |

| No | 753 | 28.8 | |

aAdvanced practice providers include advanced practice nurses, advanced practice registered nurses, nurse practitioners, and physician associates.

b‘Other’ included respondents who had selected other, dieticians, pharmacy technicians, psychologists, and social workers.

cA breakdown of all specialties can be found in the supplemental materials.

In total, 71.2% of the survey population reported they use social media, with 11.5% using social media exclusively for professional purposes, 22.8% for personal purposes, and 65.7% for both professional and personal purposes. Learners preferred to access social media at home (59.5%) and only a small percentage of respondents accessed social media exclusively at work (2.3%). For those who use social media, 74% of respondents reported they spend ≤7 hours per week on social media platforms with half spending less than 3 hours each week.

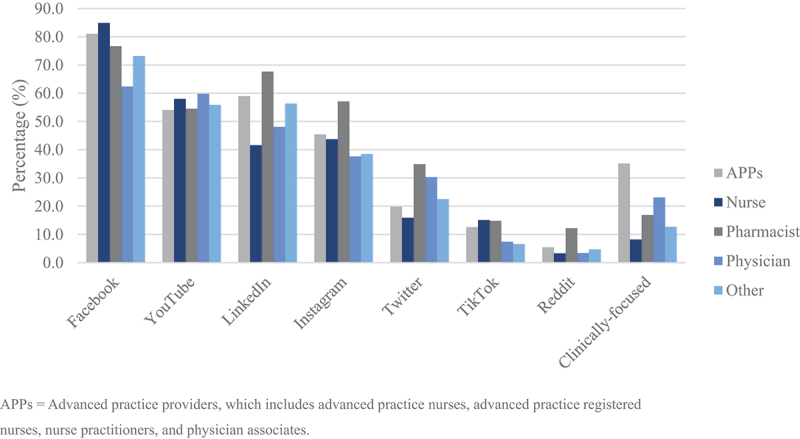

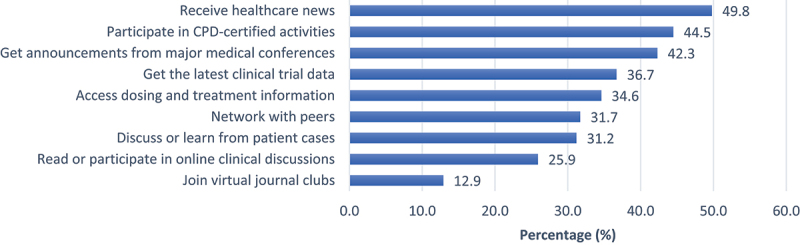

The most used social media platform among HCPs was Facebook (70.7%) followed by YouTube (57.9%), LinkedIn (52.2%), WhatsApp (50.6%), Instagram (41.7%), Twitter (26.6%), TikTok (9.9%), and Reddit (4.7%). Clinically focused social media platforms were used by 20.4% of the respondents (Figure 1). There were no significant differences among the various professions. Most respondents who use social media indicated they use social media for a variety of purposes that assist them in their current practice (Figure 2). Learners typically engaged with social media either by reading (79.7%), sharing content with their networks (38.6%), or create and post original content (16.4%)

Figure 1.

Social media use among HCP participants.

Figure 2.

Professional uses of social media among HCPs.

Learners who used social media to participate in CPD activities were associated with urban and suburban practice settings (p = .001), had moderate weekly usage of social media (8–14 hours, p = .004), and consumed medical information only if it originated from a clinically focused source (p = <.001) (Table 2). Respondents specializing in addiction medicine, family medicine, pediatrics, and psychiatry were more likely to participate in CPD activities via social media whereas specialties such as gastroenterology, hematology, and infectious disease showed a lower likelihood (p = <.001). There were no statistically significant associations between CPD participation via social media and experience level, profession type, and all other specialties. Participants expressed several concerns with accessing medical information via social media. These concerns included the legitimacy of the information (58.3%), privacy issues (57%), time constraints (29.7%), and institutional barriers (14.9%). Only a small portion of respondents indicated no concerns with using social media as a tool to access medical information (7.1%).

Table 2.

Associations between respondent characteristics and the use of social media for CPD activities.

| No. (%) of Yes | No. (%) of No | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experience (n=1602) | 1–5 years | 67 (4.2) | 82 (5.1) | 0.164 |

| 6–15 years | 183 (11.4) | 179 (11.2) | ||

| More than 15 years | 578 (36.1) | 513 (32.0) | ||

| Setting (n=1602) | Urban* | 475 (29.7) | 513 (32.0) | .001 |

| Suburban* | 233 (14.5) | 171 (10.7) | ||

| Rural* | 120 (7.5) | 90 (5.6) | ||

| Social media use per week (n=1602) | Less than 3 hours* | 260 (16.2) | 300 (18.7) | .004 |

| 3–7 hours | 322 (20.1) | 297 (18.5) | ||

| 8–14 hours* | 172 (10.7) | 123 (7.7) | ||

| More than 14 hours | 74 (4.6) | 54 (3.4) | ||

| Reason for use (n=1602) | Professional* | 83 (5.2) | 115 (7.2) | <.001 |

| Personal* | 137 (8.6) | 181 (11.3) | ||

| Both* | 608 (38.0 | 478 (29.8) | ||

| When do you use social media? (n=1602) | Home | 466 (29.1) | 467 (29.2) | .015 |

| Work* | 13 (0.8) | 24 (1.5) | ||

| Both* | 349 (21.8) | 283 (17.7) | ||

| Believe medical information from social media is credible (n=1602) | Yes | 233 (14.5) | 227 (14.2) | <.001 |

| No* | 116 (7.2) | 178 (11.1) | ||

| Only if the information was from a clinically focused platform* | 479 (30.0) | 369 (23.0) | ||

| How likely are you to use social media in your practice in the next 5 years? (n=1573) | More likely to use | 432 (27.5) | 395 (25.1) | <.001 |

| Less likely to use* | 73 (4.6) | 117 (7.4) | ||

| Same amount of usage | 310 (19.7) | 246 (15.6) | ||

*Indicates a statistically significant relationship between categories.

Discussion

The 2023 CEA HCP survey investigated the utilization habits and professional uses of social media among HCPs. The findings echoed trends seen in previous HCP social media surveys, highlighting that most HCPs were active on social media, using it both for personal and professional purposes [4,13–16]. Social media was used primarily to stay informed about medical news, participate with CPD activities, and access treatment information. Social purposes, especially virtual journal clubs and online clinical discussions, emerged as the least common professional uses of social media among the respondents. Social media platforms allow users to interact with one another over different content formats. While social purposes were used to a lesser extent in our study, these activities may be best utilized on the lesser used platforms. For example, platforms such as Instagram and X/Twitter can allow creators to show brief videos of mock patient cases which leads to an extensive clinical conversation in the comment section. On average, HCPs were active on three social media platforms. Future efforts should evaluate how current social media platforms could be integrated into the development and dissemination of CPD activities to help HCPs stay abreast of current best practices in their fields.

Interestingly, although most HCPs were on social media, they tend not to dedicate a significant amount of time to these platforms each week. While this survey did not delve into the specific use patterns explaining this observation, several factors may contribute. It could be caused by time restraints imposed by the demanding nature of the respondent’s professions or be due to personal boundaries such time limits and restrictions on what content with which they interact. Additionally, this survey indicates that HCPs prefer passive engagement with social media-based content. The preferred content formats were short articles (70.9%), videos (63.4%), and slide sets (57.9%). Most respondents reported that they typically read the material or share it within their networks. Only a small percentage of respondents used social media to create and post original content (16.4%). This suggests that HCPs may be very selective in how they use their limited time. Recognizing the preferences for content formats among HCPs can guide the CPD industry in designing programs to accommodate for the busy schedules of HCPs. With numerous active online communities across a variety of specialties, it may be worthwhile for CPD entities to identify connected HCPs and leverage these networks to not only ensure information is available in suitable formats but also to facilitate the sharing of valuable content among a broader HCP audience.

In a previous CEA survey conducted in 2017, 54% of surveyed physicians were using social media for professional and occupational purposes. Notably, physicians aged 25 to 44 years were more likely to engage in such professional social media usage [19]. In this study, 77% of participants used social media in a professional capacity with 11% using social media exclusively for professional purposes. Unlike the 2017 analysis, the current research notes no differences in the professional use of social media across the different experience levels. This survey did not collect information on the age of the respondent. Future research may be necessary and worthwhile to explore the generational differences in how HCPs use social media in their practice. With many of the surveyed learners active on social media, it is reasonable to assume that HCPs, regardless of their level of experience, have become increasingly adept at using social media to find trusted outlets of medical information and educational content.

Despite the numerous advantages of using social media for HCPs, many of the survey respondents expressed concerns, highlighting potential barriers that might hinder learners from accessing CPD activities through social media. In our study, we found that participants who questioned the credibility of medical information found on social media were less likely to access CPD content. Conversely, those who had identified trusted online sources of medical information were more likely to participate in CPD activities via social media. To further promote the use of social media for connecting HCPs, efforts should take into account current perceptions among HCPs and prioritize the safety and credibility of the information shared. The CPD industry is well-equipped to address this issue as accredited CPD providers are responsible for this in any content creation. Specifically, Standard 1 of the 2020 Standards for Integrity and Independence in Accredited Continuing Education requires all scientific content discussed in a CPD-certified activity to conform to accepted standards of research design, and all patient recommendations must be based on current evidence and utilize sound clinical reasoning [20]. As internet-based education grows, the Accredited Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME) is evaluating existing policies and creating new guidance on the delivery of accredited education via online and social media platforms. Based on the evident support for social media-based content among HCPs, it would be appropriate for CPD entities to extend the same rigorous standards to their certified activities to social media initiatives. Additional measures may be necessary to ensure the validity and compliance of social media-based educational content with ACCME standards thus inspiring future research on the CPD community’s implementation of social media-based accredited education.

Overall, our research findings suggest that leveraging social media to support CPD activities can be a valuable strategy for engaging HCPs. As such, it becomes critical for the CPD industry to identify HCPs who are more open to using social media to participate in CPD programs and to develop strategies to connect these learners with content they need. One potential use of social media in the CPD space is to raise awareness for current CPD programs. A recent study found that more professional marketing firms are using social media networking as a preferred method over email marketing [21]. Based on industry shifts, it seems appropriate for CPD entities to take advantage of social media to promote their current and upcoming CPD activities to a broader audience of HCPs.

The results of this survey should be considered within the context of the following limitations. Firstly, this survey was only available to CEA learners, which could introduce sampling bias and make the results less representative of the broader HCP population. Our respondent pool skewed senior, with most HCPs having more than 15 years of experience. This could affect the relevance of certain findings, such as the significant reported usage of Facebook, which may not capture the social media habits of junior HCPs. Secondly, voluntary participation could result in opportunistic sampling and response bias. A large portion of the respondents reporting social media use, while consistent with other surveys, might also suggest some selection bias as those who received and responded to the survey invitation may be more active on social media. Additionally, respondents were not required to answer all questions in the survey, which could lead to incomplete or selective responses that may have skewed the results seen in this analysis. Lastly, the respondent population was predominantly composed of physicians working in urban areas, with other professions being underrepresented. As a result, it is difficult to generalize these findings across all HCPs, given the potential professional and location bias.

Ultimately, the results of this survey offer valuable insights into the ways HCPs engage on social media. These insights provide a foundation for designing future CPD activities that align with the preferences of HCPs. By leveraging these insights, CPD providers can create more effective programs that cater to the needs of HCPs in the digital age.

Conclusion

Social media is a powerful digital tool available to HCPs. It has evolved beyond entertainment and is now being used increasingly for professional purposes including staying updated on clinical trials, accessing treatment and dosing information, connecting with peers, and engaging with CPD activities. As the CPD industry continues to evolve, the findings of this survey underscore the importance of recognizing and enacting social media-based strategies to engage with HCPs. These strategies will be vital for ensuring safe and credible dissemination of medical information in the digital age.

Supplementary Material

Funding Statement

The author(s) reported there is no funding associated with the work featured in this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/10872981.2024.2316489

References

- [1].Flynn S, Hebert P, Korenstein D, et al. Leveraging social media to promote evidence-based continuing medical education. PLoS One. 2017;12(1):e0168962. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0168962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Moorhead SA, Hazlett DE, Harrison L, et al. A new dimension of health care: systematic review of the uses, benefits, and limitations of social media for health communication. J Med Internet Res. 2013;15(4):e85. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Hazzam J, Lahrech A.. Health care professionals’ social media behavior and the underlying factors of social media adoption and use: quantitative study. J Med Internet Res. 2018;20(11):e12035. doi: 10.2196/12035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].von Muhlen M, Ohno-Machado L. Reviewing social media use by clinicians. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2012;19(5):777–6. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2012-000990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Topf JM. Introduction: social media and medical education come of age. Semin Nephrol. 2020;40(3):247–248. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2020.04.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].D’souza F, Shah S, Oki O, et al. Social media: medical education’s double-edged sword. Future Heal J. 2021;8(2):e307–e310. doi: 10.7861/fhj.2020-0164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Lopez M, Chan TM, Thoma B, et al. The social media Editor at medical journals: responsibilities, goals, barriers, and facilitators. Acad Med J Assoc Am Med Coll. 2019;94(5):701–707. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Ventola CL. Social media and health care professionals: benefits, risks, and best practices. Pharm Ther. 2014;39(7):491–520. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Peck JL. Social media in nursing education: responsible integration for meaningful use. J Nurs Educ. 2014;53(3):164–169. doi: 10.3928/01484834-20140219-03 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Chan TM, Dzara K, Dimeo SP, et al. Social media in knowledge translation and education for physicians and trainees: a scoping review. Perspect Med Educ. 2019;9(1):20. doi: 10.1007/S40037-019-00542-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Regmi K, Jones L. A systematic review of the factors – enablers and barriers – affecting e-learning in health sciences education. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20(1):91. doi: 10.1186/s12909-020-02007-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Janis S. Continuing professional development. Accreditation council for pharmacy education. [cited 2024 Jan 2]. Availabe from: https://www.acpe-accredit.org/continuing-professional-development/

- [13].Yoon S, Wee S, Lee VSY, et al. Patterns of use and perceived value of social media for population health among population health stakeholders: a cross-sectional web-based survey. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):1312. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-11370-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Surani Z, Hirani R, Elias A, et al. Social media usage among health care providers. BMC Res Notes. 2017;10(1):654. doi: 10.1186/s13104-017-2993-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Guerra F, Linz D, Garcia R, et al. The use of social media for professional purposes by healthcare professionals: the #intEHRAct survey. EP Eur. 2022;24(4):691–696. doi: 10.1093/europace/euab244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Wang AT, Sandhu NP, Wittich CM, et al. Using social media to improve continuing medical education: a survey of course participants. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87(12):1162–1170. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2012.07.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].McGowan BS, Wasko M, Vartabedian BS, et al. Understanding the factors that influence the adoption and meaningful use of social media by physicians to share medical information. J Med Internet Res. 2012;14(5):e2138. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Benetoli A, Chen TF, Schaefer M, et al. Professional use of social media by pharmacists: a qualitative study. J Med Internet Res. 2016;18(9):e258. doi: 10.2196/jmir.5702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Bowser A. Social media behavior and attitudes of US physicians: implications for continuing education providers. Clin Care Options;2017:289–296. [cited 2023 Aug 17]. Availabe from: https://clinicaloptions.com/CE-CME/general-preventive-medicine/2022-publication-and-abstract-book/22989 [Google Scholar]

- [20].Standards for integrity and independence in accredited continuing education | ACCME. [cited 2023 Aug 16]. Availabe from: https://accme.org/accreditation-rules/standards-for-integrity-independence-accredited-ce

- [21].Frederiksen L. Using social media for marketing professional services. Hinge Marketing. Published August 19, 2021. [cited 2023 Aug 14]. Availabe from: https://hingemarketing.com/blog/story/using-social-media-for-marketing-professional-services

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.