Abstract

The HIS4 gene in Saccharomyces cerevisiae was put under the transcriptional control of RNA polymerase I to determine the in vivo consequences on mRNA processing and gene expression. This gene, referred to as rhis4, was substituted for the normal HIS4 gene on chromosome III. The rhis4 gene transcribes two mRNAs, of which each initiates at the polymerase (pol) I transcription initiation site. One transcript, rhis4s, is similar in size to the wild-type HIS4 mRNA. Its 3′ end maps to the HIS4 3′ noncoding region, and it is polyadenylated. The second transcript, rhis4l, is bicistronic. It encodes the HIS4 coding region and a second open reading frame, YCL184, that is located downstream of the HIS4 gene and is predicted to be transcribed in the same direction as HIS4 on chromosome III. The 3′ end of rhis4l maps to the predicted 3′ end of the YCL184 gene and is also polyadenylated. Based on in vivo labeling experiments, the rhis4 gene appears to be more actively transcribed than the wild-type HIS4 gene despite the near equivalence of the steady-state levels of mRNAs produced from each gene. This finding indicated that rhis4 mRNAs are rapidly degraded, presumably due to the lack of a cap structure at the 5′ end of the mRNA. Consistent with this interpretation, a mutant form of XRN1, which encodes a 5′-3′ exonuclease, was identified as an extragenic suppressor that increases the half-life of rhis4 mRNA, leading to a 10-fold increase in steady-state mRNA levels compared to the wild-type HIS4 mRNA level. This increase is dependent on pol I transcription. Immunoprecipitation by anticap antiserum suggests that the majority of rhis4 mRNA produced is capless. In addition, we quantitated the level of His4 protein in a rhis4 xrn1Δ genetic background. This analysis indicates that capless mRNA is translated at less than 10% of the level of translation of capped HIS4 mRNA. Our data indicate that polyadenylation of mRNA in yeast occurs despite HIS4 being transcribed by RNA polymerase I, and the 5′ cap confers stability to mRNA and affords the ability of mRNA to be translated efficiently in vivo.

RNA transcribed by RNA polymerase (pol) II undergoes a number of covalent modifications before being exported to the cytoplasm as mature mRNA and subsequently translated. Two such modifications, capping at the 5′ end and polyadenylation at the 3′ end of mRNA, are believed to be limited to the RNA pol II transcriptional machinery. The addition of the unique cap structure to the 5′ end of all mature eukaryotic mRNAs is tightly coupled to RNA pol II transcription as the cap can be detected when the 5′ end of mRNA emerges from the pol II transcriptional machinery (22, 32, 49). It has been shown that the cap structure is important for RNA transport, pre-RNA splicing, and mRNA stability (16, 23, 30, 40).

One of the best-understood functions of the cap structure is its role in translation initiation. According to the ribosomal scanning model (34), the eukaryotic initiation factor eIF-4F complex is required for the binding of the ribosomal preinitiation complex to mRNAs and for unwinding secondary structure in the 5′ leader region. This allows the preinitiation complex to scan for the first downstream AUG start codon in a 5′-to-3′ direction (for reviews, see references 25 and 54). The well-accepted ribosomal scanning model (cap-dependent initiation mechanism) accounts for most of eukaryotic translation initiation events. However, a number of mRNAs have been described to be translated by a cap-independent mechanism of translation. For example, upon poliovirus infection of mammalian cells, the eIF-4F initiation complex is rendered nonfunctional as a result of proteolytic cleavage of the p220 subunit. This results in the shutdown of cap-dependent protein synthesis in host cells and allows preferential translation of uncapped viral mRNAs, which occurs by a cap-independent mechanism (reviewed by Sonenberg [55]). Cap-independent translation initiation has also been described for cellular mRNAs (38, 45). Previous studies have used in vivo-expressed capless mRNAs in mammalian cells to investigate the relationship between the cap structure and the translation efficiency (19, 20). However, these studies differ in conclusion as to whether a cap is needed for translation in these cells.

The poly(A) tail at the 3′ end of eukaryotic mRNAs is another distinct feature of eukaryotic mRNAs. The polyadenylation step takes place in the nuclei posttranscriptionally. In short, the AAUAAA- and G/U-rich elements at the 3′ end of mRNA signal transcription termination and specific cleavage followed by consecutive addition of adenosine residues (8, 39, 58). McCracken et al. (39) have reported that the carboxy-terminal domain (CTD) of the pol II large subunit is required for efficient cleavage at the poly(A) site in vivo and that the CTD might associate with CPSF (cleavage and polyadenylation specificity factors) and CstF (cleavage stimulation factors) but not poly(A) polymerase (39), suggesting that the polyadenylation machinery, in part, associates with the pol II transcriptional apparatus. The synthesized tail is typically homogeneous in length, ranging from 75 nucleotides (nt) (40) in yeast cells to 200 nt (3) in mammalian cells. In the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae a general mechanism for mRNA decay whereby mRNA is first deadenylated down to approximately 10 A residues, which triggers the decapping of mRNA and subsequent 5′-to-3′ degradation of the message, has been proposed (2, 40). The 5′-to-3′ exonuclease that appears responsible for the bulk of mRNA degradation is encoded by the XRN1 gene.

In addition to degradation of mRNA, poly(A) tails have also been implicated to be involved in translation. For example, poly(A)-tailed mRNAs are translated more efficiently than their deadenylated counterparts in rabbit reticulocyte lysates (31). In addition, genetic studies of yeast have implicated a connection between the poly(A) tails and the poly(A) binding protein (PABP) with translation of mRNA. A mutation in the SPB4 gene encoding one of the 60S ribosomal proteins can suppress the lethality resulting from a deletion of the pab1 gene, which encodes the major PABP in budding yeast. This finding suggested that PABP might be involved in translation (50). PABP-poly(A) complex has also been shown to enhance translation efficiency in vitro by recruiting 40S subunits to mRNAs, and this enhancement was cap binding protein (eIF-4E) independent (56). Recent studies have established a functional relationship between the cap structure at the 5′ end of mRNA and the poly(A) tail of mRNA. The Pab1 protein can copurify and coimmunoprecipitate with the eIF-4γ subunit of the eIF-4F complex in yeast extracts (57), suggesting that the 3′ and 5′ ends of mRNA may be near each other when mRNA is actively translated. Thus, a complex interplay exists between the cap and the poly(A) tail in both mRNA stability and translation initiation (6, 56, 57).

In this study, we put the yeast HIS4 gene under the transcriptional control of the pol I ribosomal DNA (rDNA) promoter/enhancer region (referred to as the rhis4 gene) and extensively characterized the transcription of this gene, the 5′ and 3′ processing of transcripts, and the translational expression of rhis4 mRNA in yeast. Our analysis shows that RNA pol I promotion of HIS4 results in two mRNA species; one is the same size as the HIS4 mRNA, and the other is 1.3 kb longer than the HIS4 mRNA and is bicistronic. Surprisingly, both mRNAs appear to be polyadenylated despite transcription by RNA pol I. An xrn1Δ strain or a genetically isolated suppressor of rhis4, rhis1 (rhs stands for rhis4 suppressor) which encodes a defective xrn1 gene, results in a 9- to 10-fold increase in the combined levels of rhis4 mRNAs. This observation suggests that the majority of the rhis4 mRNAs are transcribed by pol I and degraded rapidly due to the absence of a cap structure. Despite a large increase in the level of rhis4 mRNAs in an rhs1 (xrn1) mutant strain, the level of His4 protein remains low relative to a HIS4+ strain. Our data suggest that in yeast cells, polyadenylation of rhis4 mRNAs is able to occur independently of RNA pol II transcription. In addition, our results point to the cap as being an essential element for efficient translation initiation in yeast cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Yeast strains and genetic methods.

Strains used in this work are listed in Table 1. Standard genetic methods and media have been previously described (52).

TABLE 1.

Strains used

| Strain | Genotype |

|---|---|

| 45-3B | MATα ura3-52 leu2-3,112 his4Δ-401 |

| 1566-18B | MATα his4-316 ura3-52 ino1-13 |

| 1567-5A | MATa his4-316 ura3-52 trp1 |

| 1567-32C | MATα his4-316 ura3-52 leu2-3,112 ade5 inol-13 |

| HH828 | MATα rhis4 ura3-52 leu2-3,112 XRN1::URA3 |

| HH879 | MATa ura3-52 ino1-13 p1254 (YEp24-URA3-HIS4) |

| HH880 | MATa ura3-52 ino1-13 upf1Δ::URA3 |

| HH881 | MATa ura3-52 ino1-13 rhis4 upf1Δ::URA3 |

| HH882 | MATa ura3-52 ino1-13 rhis4-AGG upf1Δ::URA3 |

| HJ35 | MATa ura3-52 ino1-13 rhis4 rhs1 (xrn1) |

| HJ224 | MATα rpa135::LEU2 ade2-1 ura3-1 his3-11 trp1-1 leu2-3,112 can1-100 pNOY102 (plasmid carrying GAL7-35S rDNA [44]) |

| HJ239 | MATa ura3-52 ino1-13 rhis4-AGG |

| HJ291 | MATa ura3-52 ino1-13 rhis4-AGG |

| HJ307 | MATa ura3-52 rhis4-AGG gal2 |

| HJ320 | MATα ura3-52 leu2-3,112 rhis4 gal2 |

| HJ322 | MATa ura3-52 leu2-3,112 trp1-1 rhis4 |

| HJ325 | MATa ura3-52 leu2-3,112 rhis4 |

| HJ332 | MATα ura3-52 inol-13 |

| HJ336 | MATa ura3-52 leu2-3,112 HIS4 |

| HJ337 | MATa ura3-52 leu2-3,112 rhis4 |

| HJ339 | MATα ura3-52 leu2-3,112 rhis4-AGG |

| HJ343 | MATα ura3-52 leu2-3,112 trp1-1 HIS4 rpa135Δ::LEU2 pNOY102 |

| HJ346 | MATa ura3-52 leu2-3,112 HIS4 rpa135Δ::LEU2 pNOY102 |

| HJ350 | MATa ura3-52 leu2-3,112 trp1-1 rhis4 rpa135Δ::LEU2 pNOY102 |

| HJ351 | MATa rhis4 ura3-52 trp1 rpa135Δ pNOY102 |

| HJ354 | MATa leu2-3,112 ino1-13 trp1 rhis4-AGG rpa135Δ pNOY102 |

| HJ355 | MATα ura3-52 leu2-3,112 rhis4 rpa135Δ::LEU2 pNOY102 |

| HJ363 | MATa rhis4 ura3-52 rhs1 (xrn1) |

| HJ364 | MATα ura3-52 trp1-1 rhis4 rhs1 (xrn1) |

| HJ399 | MATa leu2-3,112 ino1-13 rhis4-AGG |

| HJ442 | MATa ura3-52 leu2-3,112 rhis4 rpa135Δ::LEU2 rhs1 (xrn1) pNOY102 |

| HJ429 | MATα rhis4 leu2-3,112 ura3-52 |

| HJ549 | MATa ura3-52 ino1-13 leu2-3,112 rhis4 xrn1Δ::URA3 |

| HJ556 | MATa ura3-52 ino1-13 rhis4 xrn1Δ::URA3 |

| HJ569 | MATa ura3-52 ino1-13 leu2-3,112 rhis4-AGG xrn1Δ::URA3 |

| TD28 | MATa ura3-52 ino1-13 |

| TD237 | MATa ura3-52 ino1-13 rhis4 |

For construction of the rhis4 allele, a 2.5-kb EcoRI restriction fragment containing the enhancer/promoter region from plasmid pJ10-2 (14), which contains a unit repeat of the rDNA cistron, was introduced at a unique EcoRI restriction site at positions −51 to −50 (A of translational initiation codon; AUG is the +1 position) in the HIS4 leader region of the Ura3+ integrating plasmid p−51/−50 (7). Plasmid p1179 has the EcoRI rDNA fragment in the orientation that would allow pol I rDNA transcription to initiate toward the HIS4 coding region as determined by restriction analysis. This plasmid was used to transform yeast strain TD28 to Ura+. This plasmid when integrated into the HIS4 locus results in a leaky His+ phenotype as a result of an upstream and out-of-frame AUG codon now present in the HIS4 leader region (see Results). Transformants with a leaky His+ phenotype were purified by streaking and plated on 5′-fluoro-orotic acid plates to enrich for loss of the vector sequences (4). Ura3− strains having a leaky His+ phenotype represented cells containing the rhis4 allele.

For construction of the rhis4-AGG allele, a 2.2-kb PvuII-NheI DNA fragment from plasmid p1179 ligated into the phage vector Mp18. The oligonucleotide 5′-AACTGCTTTCGCCTGAAGTACCTCC-3′, containing an A-to-C base change (underlined), was used to perform site-directed mutagenesis. This base change results in the AUG codon, beginning at the +1 position of the pol I-promoted transcript, being changed to AGG. A 1.3-kb SphI DNA fragment containing the mutation was isolated and substituted for the wild-type SphI fragment of plasmid pJ10-2, which contains a unit repeat of rDNA (14), to yield plasmid p1679. The 2.5-kb EcoRI restriction fragment containing the rDNA enhancer/promoter region from plasmid p1679 was subcloned into an EcoRI restriction site of p−51/−50 (7), to yield plasmid p1696. This plasmid was used to construct a yeast strain containing the rhis4-AGG allele on chromosome III, identically to that described above for the construction of an rhis4 strain.

Isogenic HIS4 (TD28), rhis4 (TD237), and rhis4-AGG (HJ291) strains containing an xrn1Δ mutation were constructed by transformation using a SalI DNA fragment derived from plasmid pdst2-1 (13), which contains a dst2 (xrn1)::URA3 deletion/disruption mutation. Deletion or disruption of the XRN1 gene in these strains was confirmed by Southern blot analysis. The rhs1 (xrn1) suppressor mutant was identified as a strong His+ revertant of yeast strain TD237. Genetic analysis identified a suppressor mutant unlinked to the rhis4 locus that conferred a slow-growth phenotype. The RHS1 (XRN1) gene was cloned by transformation from a pCT3 wild-type genomic library (kindly provided by Craig Thompson) by complementation of the slow-growth phenotype. Restriction analysis of complementing plasmids showed the DNA insert to have the same restriction pattern as the XRN1 gene. The URA3 gene was integrated adjacent to the XRN1 locus of the rhis4 strain HJ429 to generate yeast strain HH828. Yeast strain HH828 was then crossed to the rhs1 yeast strain HJ35, and diploids were subjected to tetrad analysis. For each of the 15 four-spore tetrads analyzed, the two meiotic products with the rhs1 slow-growth phenotype were Ura−, whereas the other two meiotic products with a wild-type growth phenotype were Ura+, indicating rhs1 to be very tightly linked to XRN1. Finally, an rhs1 mutant does not complement the slow-growth phenotype associated with an xrn1 deletion/disruption strain. These studies taken together indicate that the rhs1 locus is a mutant allele of the XRN1 gene.

Isogenic HIS4 (TD28), rhis4 (TD237), and rhis4-AGG (HJ291) strains containing a upf1Δ mutation were constructed by transformation using an EcoRI-BamHI DNA fragment derived from plasmid pLB65 (kindly provided by Michael Culbertson), which contains a upf1::URA3 deletion/disruption mutation. Deletion/disruption of the UPF1 gene in these strains was confirmed by Southern blot analysis.

Relevant strains containing an rpa135Δ mutation were constructed in a two-step process. First, yeast strains TD28 (HIS4+), HJ320 (rhis4), HJ307 (rhis4-AGG), and HJ35 (rhis4 rhs1) were crossed to strains 1567-32C, 1567-5A, 1566-18B, and HJ322, respectively, to generate ascospores HJ336 (HIS4+), HJ325 (rhis4), HJ339 (rhis4-AGG), and HJ363 (rhis4 rhs1) that grow well on YEPGal medium. In the second step, HJ336 was crossed to yeast strain NOY408-1D. The other three strains were crossed to either HJ343 or HJ350, ascospore derivatives of NOY408-1A or NOY408-1D, both of which contain an rpa135::LEU2 mutation and transcribe rDNA from a GAL7 pol II promoter construct on a plasmid (44). Ascospores used for our analysis are HJ346 (HIS4+), which has a His+ phenotype on galactose-containing medium and shows no growth on YEPD medium; HJ350 (rhis4), which is His− on galactose-containing medium and shows no growth on YEPD medium; HJ354 (rhis4-AGG), which is His− on galactose-containing medium and shows no growth on YEPD medium; and HJ442 (rhis4 rhs1), which is His− on galactose-containing medium and shows no growth on YEPD medium. The His− phenotype observed in these latter three strains is a result of the rpa135Δ mutation abrogating the leaky His+ phenotype normally associated with rhis4 and rhis4-AGG strains as a result of these alleles no longer being transcribed by RNA pol I.

To test whether the first 50 nt of leader sequence derived from rhis4-AGG have any inhibitory effect on translation, two DNA oligonucleotides containing the complementary sequences of this 50-nt region were hybridized and subcloned into the EcoRI site located at positions −51 to −50 of a HIS4-lacZ fusion construct (7). Yeast total protein was isolated and β-galactosidase specific activity was assayed as previously described (10).

RNA methods.

The 5′ end of the rhis4 transcripts was mapped by primer extension as previously described (7). Northern blot analysis was performed as previously described (7), with minor modifications. Twenty micrograms of total RNA was resolved on a 1% agarose gel under denaturing conditions (6% formaldehyde) and then transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (51). The membrane was incubated with 20 ml of prehybridization buffer containing 50% deionized formamide, 5× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate), 10× Denhardt’s reagent, and 2 mg of denatured calf thymus DNA. Radioactive probes were generated by using a random prime kit (Boehringer Mannheim) according to the manufacturer’s protocol, using [α-32P]ATP (3,000 Ci/mmol; Amersham). HIS4 mRNA levels were quantitated with a PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics) using ACT1 mRNA (actin) levels as an internal control.

The sites of polyadenylation of HIS4 and rhis4 mRNAs were determined by reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) by the method of Frohman (17) and with some modification by using the Perkin-Elmer Cetus GeneAmp RNA PCR kit. In the first step, 100 ng of poly(A)+ RNA from a HIS4 or rhis4 strain was mixed with oligonucleotide QT [5′-Qo-QI-d(TTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTT)-3′], to generate a cDNA pool by reverse transcriptase. In the first PCR, oligonucleotides Qo [5′-d(CCAGTGAGCAGAGTGACG)-3′] and HIS2057 [5′-d(CGGTGACTATTCAAGTGG)-3′], corresponding to positions +2157 to +2174 in the HIS4 coding region, were used to amplify rhis4s, rhis4l, and HIS4 mRNAs. In the second-round PCR, oligonucleotides QI [5′-d(GAGGACTCGAGCTCAAGC)-3′] and HIS2199 [5′-d(GGTTACGCTAGGCAGTAC)-3′], corresponding to positions +2200 to +2217 in the HIS4 coding region, were used to amplify rhis4s and HIS4 mRNAs, and oligonucleotides QI and HIS3056 [5′-d(CGAGAAGAGATACACACC)-3′] were used to amplify rhis4l mRNA. Oligonucleotide HIS3056 corresponds to positions +318 to +335 in the YCL184 coding region. The PCR fragments from rhis4s and HIS4 mRNAs were digested with SacI within QI and XbaI corresponding to position +2328 in the HIS4 coding region, subcloned into the SacI and XbaI restriction sites in M13, and analyzed by DNA sequencing. The PCR fragment from rhis4l mRNA was digested with SacI within QI and SphI corresponding to position +421 in the YCL184 coding region, subcloned into the SacI and SphI sites of M13, and analyzed by DNA sequencing.

Nuclear run-on experiments were performed as described by Elion and Warner (14). Yeast cells were permeabilized and labeled with [α-32P]UTP for 15 min in the absence or presence of 10 or 100 μg of α-amanitin per ml. Total 32P-labeled RNA was then extracted from the cells and used as a probe for Southern hybridization. Immobilized DNA fragments derived from plasmids containing the coding regions of the HIS4 gene, the URA3 gene, and the yeast transposable element Ty served as a controls for pol II transcription. A plasmid containing the 28S transcribed region of rDNA served as a control for pol I transcription. The HIS4 plasmid (B115) was restricted with EcoRI, the Ty plasmid (B80) was restricted with BglII, and the plasmid (p1241) containing the 28S rDNA was restricted with EcoRI. The results of these experiments were quantitated with a PhosphorImager. For each experiment shown in Fig. 4A, the amount of radioactivity detected hybridizing with Ty, HIS4, or rhis4 DNA was normalized to the amount of radioactivity hybridizing to rDNA. Each of these values are expressed in Fig. 4B as a percentage of the respective mRNA/rRNA species ratio determined in the absence of α-amanitin treatment.

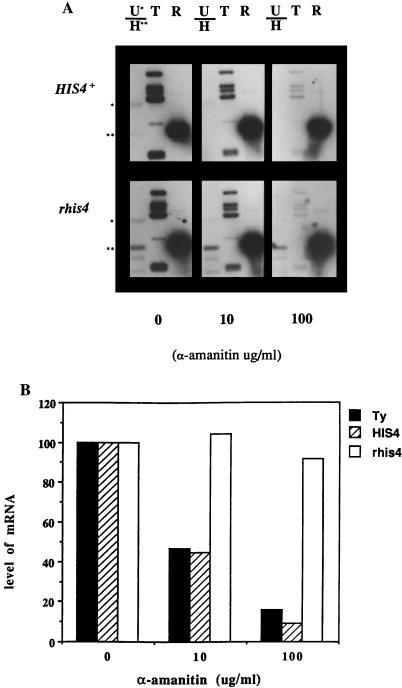

FIG. 4.

Nuclear run-on experiments using permeabilized cells in the absence or presence of α-amanitin. (A) Permeabilized yeast strains TD28 (HIS4+) and TD237 (rhis4) were incubated with [α-32P]UTP in the absence or presence of 10 or 100 μg of α-amanitin per ml. Total RNA was extracted and used as a probe for Southern hybridization. DNA fragments immobilized on nitrocellulose correspond to URA3 (top band of U/H), HIS4 (bottom band of U/H), Ty elements (T), and 28S rRNA (R). (B) The quantitation of the data in panel A. The levels of Ty, HIS4, and rhis4 mRNAs are normalized by the levels of hybridized rRNA. The relative level of mRNAs from cells incubated in the absence of α-amanitin is expressed as 100%.

Immunoprecipitations with polyclonal anti-m7G antibodies (42) (kindly provided by R. Parker and E. Lund) were performed as described by Muhlrad et al. (40). Prior to immunoprecipitation, total RNA isolated from a HIS4 or rhis4 rhs1 (xrn1) strain was hybridized to an oligonucleotide, 5′-d(GGAGAACTGGAGAATCTCTTC)-3′, that is complementary to positions +90 to +111 in the HIS4 coding region. RNA-DNA duplex was cleaved with RNase H, resulting in 157- and 197-nt fragment for HIS4 and rhis4 mRNAs, respectively. The supernatant and pellets were subjected to electrophoresis on a 10% polyacrylamide gel with 6 M urea. The cleavage products of rhis4 and HIS4 mRNAs were detected by Northern blot analysis using a 32P-labeled antisense RNA complementary to positions −50 to +97 in the HIS4 gene. The membrane was exposed in a PhosphorImager screen (Molecular Dynamics) for 3 days and visualized in a PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics). The cleaved and intact HIS4 and rhis4 were detected and recorded. As a control for immunoprecipitation, the same membrane was hybridized with a 32P-labeled DNA probe complementary to the MFA2 gene, and the intact MFA2 mRNA was visualized in a PhosphorImager after 1 day of exposure.

Western blot analysis.

Protein extracts were prepared from yeast and analyzed by Western blots as previously described (11, 29). Rabbit polyclonal antisera directed against either the His4 protein (1:10,000) or the eIF-2γ (1:25,000) were used as the primary probes in an overnight incubation. Peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (Sigma) was used as the secondary probe (1:25,000) in a 2-h incubation. The antibody-antigen complex was detected by the Amersham ECL system according to the manufacturer’s protocol. To quantitate the protein levels, the film was scanned by a densitometer (Molecular Dynamics). For each lane, the density of the His4 band was compared to the density of the eIF-2γ protein band, as an internal control.

RESULTS

Construction of rhis4 strains.

The main aim of this study was to elucidate the possible functions of the cap structure of mRNA in yeast by generating and characterizing an uncapped cellular mRNA in vivo. The rhis4 gene was constructed (Fig. 1; also see Fig. 3) such that the HIS4 gene could be transcribed by a pol I-specific promoter. The construct consists of the 2.5-kb EcoRI restriction fragment containing the rDNA enhancer/promoter region (14) that was introduced upstream at a unique EcoRI restriction site at positions −51 to −50 (A of translational initiation codon; AUG is the +1 position) in the HIS4 leader (7). This promoter fusion construct was then introduced at the HIS4 locus by the integration-excision method. Transcription from this construct is predicted to start at the 35S rDNA gene transcription initiation site, resulting in the rhis4 mRNA having a 5′ untranslated region (UTR) 100 nt in length. The first 50 nt of the leader region of the rhis4 mRNA will be derived from the 35S rRNA, and the downstream 50 nt of the 5′ UTR of rhis4 mRNA are predicted to be derived from the HIS4 mRNA leader.

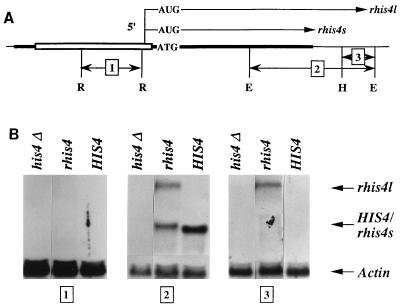

FIG. 1.

Northern blot analysis of the rhis4s and rhisl mRNAs. (A) Schematic representation of the rhis4 gene. The open bar represents the rDNA enhancer/promoter region, and the solid bar represents HIS4 sequences. (B) Twenty micrograms of total RNA was isolated from yeast strains 45-3B (his4Δ), TD237 (rhis4), and TD28 (HIS4+) and analyzed by Northern blotting using 32P-labeled probes complementary to different regions of the rhis4 construct. Location of the probes are shown in panel A. Probe 1 is a 1.5-kb RsaI DNA fragment derived from plasmid pJ10-2 (14) and is complementary to the region upstream of the predicted 35S transcription initiation site. Probe 2 is a 2.7-kb EcoRI DNA fragment from plasmid B115 (12) and is complementary to the HIS4 distal coding region, the 3′ UTR of the HIS4 gene, and the 5′ region of the YCL184 gene. The YCL184 gene is located downstream of the HIS4 gene and is predicted to be transcribed in the same direction as the HIS4 gene (48). Probe 3 is an approximately 0.5-kb HindIII-EcoRI fragment derived from plasmid B115 which is located downstream of the HIS4 3′ UTR. All filters were coprobed with a 3.0-kb EcoRI-BamHI DNA fragment containing the entire actin gene. R, RsaI; E, EcoRI; H, HindIII.

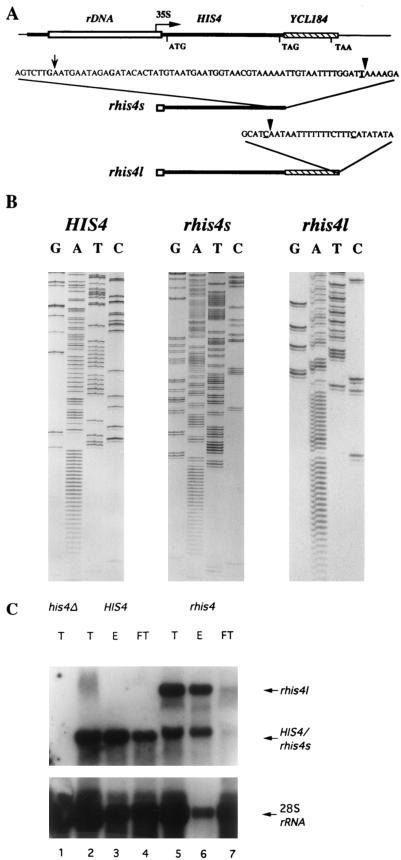

FIG. 3.

RT-PCR mapping of the site of polyadenylation of rhis4 mRNA species and analysis of their ability to bind oligo(dT) cellulose. (A) Schematic summary of RT-PCR mapping of the rhis4s and rhis4l mRNA polyadenylation sites relative to the 3′ UTR of the HIS4 and YCL184 genes, respectively. The complete sequence of the 3′ UTRs from the HIS4 and YCL184 genes relative to their respective translation stop codons is not shown. The relevant nucleotides corresponding to the sites of polyadenylation in different RT-PCR clones is described in the text. (B) Example of the DNA sequence of one RT-PCR clone obtained for each mRNA. The corresponding sites of polyadenylation are indicated by an arrow or arrowhead (left to right) in panel A. (C) Total RNA isolated from different yeast strains was passed over an oligo(dT) column. Total RNA (T; 20 μg), flowthrough fractions (FT; 20 μg), and RNA which bound and was eluted from the column (E; 5 μg) were then subjected to Northern blot analysis using a 32P-labeled HIS4 probe (top panel). Filters were washed and then reprobed with a 32P-labeled probe from 28S rDNA (bottom panel). Lanes: 1, total RNA from the his4Δ strain, 45-3B; 2 to 4, total, eluted, and flowthrough fractions from the HIS4+ strain, TD28; 5 to 7, total, eluted and flowthrough fractions from the rhis4 strain, TD237.

Characterization of the rhis4 mRNAs.

To characterize rhis4 expression, we first measured the steady-state level of the rhis4 transcript by Northern blot analysis using a 32P-labeled probe which contains sequences complementary to the downstream coding region of the HIS4 gene. As shown in panel 2 of Fig. 1B, two different-size rhis4 mRNAs are detected (middle lane); one transcript, rhis4s, is approximate the same size as the wild-type HIS4 mRNA, while the other transcript, rhis4l, is approximately 1.3 kb longer than the HIS4 and rhis4s mRNAs. The combined steady-state level of the rhis4s and rhis4l mRNAs was quantitated to be in the range of 50 to 100% of the HIS4 mRNA level, using actin mRNA levels as an internal control.

To map the 5′ and 3′ boundaries of the rhis4s and rhis4l mRNAs, we used 32P-labeled probes from different regions of the rhis4 gene. Probe 1 (Fig. 1A) was a 1.5-kb RsaI fragment complementary to the region upstream of the 35S rDNA transcription initiation site. Probe 3 (Fig. 1A) was derived from the region downstream of the HIS4 locus and excludes sequences that are complementary to the 3′ UTR of HIS4. As shown in panel 1 of Fig. 1B, neither the rhis4s nor the rhis4l mRNA is detected with probe 1, suggesting that the transcription initiation site of both species of rhis4 mRNA is located downstream of probe 1. Probe 3 does not detect the HIS4 mRNA as expected, nor does it detect the rhis4s mRNA. Thus, rhis4s mRNA appears to have 5′ and 3′ boundaries similar to those of the HIS4 mRNA. In contrast, probe 3 detects the rhis4l mRNA. Thus, rhis4l mRNA appears to have a 5′ boundary similar to that of rhis4s mRNA, but rhis4l is longer at the 3′ end than the rhis4s and HIS4 mRNAs.

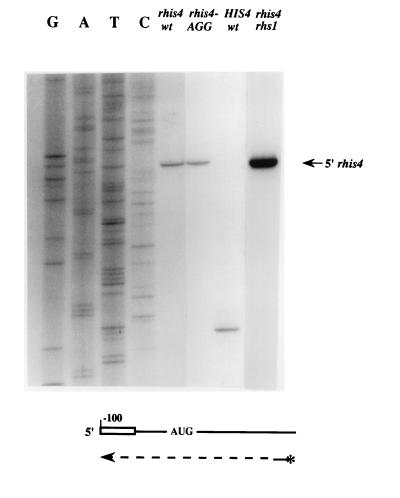

To determine whether the two species of rhis4 mRNAs have the same transcription initiation site, the 5′ ends of the rhis4 transcripts and the HIS4 mRNA were analyzed by primer extension analysis using an oligonucleotide complementary to positions +10 to +31 in the HIS4 coding region. Figure 2 shows that the transcription initiation site of the HIS4 gene maps to position −60 relative to the translation initiation codon, as previously described (second lane from right) (12, 43). In contrast, the transcription start site of the rhis4 gene is located at position −100 (Fig. 2, fourth lane from right, indicated by an arrow), which corresponds to the predicted 35S rDNA transcription initiation site (1, 33). No primer extension product was detected either upstream or downstream of the pol I transcription start site. This analysis in combination with the Northern analysis indicates that both species of rhis4 mRNAs are initiated at the pol I transcription initiation site.

FIG. 2.

Primer extension analysis of the rhis4 and rhis4-AGG mRNAs. A 50-μg sample of total RNA isolated from yeast strains TD28 (HIS4+), TD237 (rhis4), HJ291 (rhis4-AGG), and HJ35 (rhis4 rhs1 [xrn1]) was characterized by primer extension analysis. Five picomoles of the 32P-labeled oligonucleotide 38, 5′d(CATCAATTAACGGTAGAATCGG)3′, which is complementary to positions +10 to +31 in the HIS4 coding region, was used as a primer. The transcription initiation site of the rhis4 and rhis4-AGG mRNAs is indicated by an arrow. A DNA sequencing ladder, GATC, from rhis4 DNA, is presented. wt, wild type.

To map the 3′ ends of both rhis4 mRNAs, RT-PCRs were performed and the products were subcloned to an M13 vector for DNA sequencing. In total, four clones from the HIS4 PCR pool, four clones from the rhis4s PCR pool, and five clones from the rhis4l PCR pool were sequenced. Figure 3A summarizes the results, and Fig. 3B shows one of the sequences from each of the mRNA PCR pools. Three different polyadenylation sites were identified among the four clones from the HIS4 pool. Two clones mapped the polyadenylation site to be 137 nt downstream of the HIS4 translational stop codon (Fig. 3A, underlined T next to top arrowhead), and the other two clones mapped polyadenylation sites to be either 80 or 84 nt downstream of the HIS4 translational stop codon, respectively (Fig. 3A, two G’s flanking leftmost arrow). All four clones from the rhis4s pool mapped the polyadenylation site to be 137 nt downstream of the translational stop codon at HIS4, identical to what was observed for two of the HIS4 clones. Four clones from the rhis4l pool mapped the polyadenylation site to be 102 nt downstream of the translational stop codon of the YCL184 gene (Fig. 3A, underlined C next to bottom arrowhead), and the remaining clone from the rhis4l pool mapped a site to be 119 nt downstream of the YCL184 stop codon (Fig. 3A, underlined C to the right). As for other yeast genes, polyadenylation starts right before or after an adenosine residue (24). In addition, there is more than one polyadenylation site for HIS4 or rhis4l as observed for other yeast genes. The YCL184 gene was identified as part of the chromosome III sequencing project and represents the first gene downstream of HIS4 that is predicted to be transcribed in the same direction (48). Interestingly, the rhis4l mRNA appears to be a bicistronic mRNA.

To determine whether the majority of rhis4 mRNAs are polyadenylated, poly(A)+ RNA was separated from poly(A)− RNAs by oligo(dT)-cellulose chromatography. Total RNA, RNAs bound to the oligo(dT) column (eluted from column), and RNAs that did not bind to the oligo(dT) column (flowthrough) were analyzed by Northern blotting using a probe complementary to the coding region of the HIS4 gene. Blots were then reprobed with a 32P-labeled probe from the 28S transcribed region of rDNA (Fig. 3C, bottom panel) to determine the efficiency of separation of poly(A)+ RNA from poly(A)− RNA. As shown in Fig. 3C, the amount of HIS4 mRNA that bound to oligo(dT) was more than that detected in the flowthrough fraction (lanes 4 and 5). rhis4 mRNAs also bound to the oligo(dT) column (lanes 6 and 7), suggesting that the majority of rhis4s and rhis4l mRNAs are polyadenylated.

rhis4 is transcribed by pol I.

One way to distinguish pol I and pol II transcription is to determine whether transcription is sensitive to the specific pol II inhibitor α-amanitin. Detergent-permeabilized yeast cells were used to determine the effects of α-amanitin on rhis4 transcription. As shown by Elion and Warner (14), permeabilized cells provide a convenient means to examine run-on transcription in vivo. Permeabilized cells were labeled with [α-32P]UTP for 15 min in the absence or presence of 10 or 100 μg of α-amanitin per ml. Total 32P-labeled RNA was then extracted from these cells and used as a probe for Southern hybridization. Immobilized DNA fragments were derived from plasmids containing the coding region of the HIS4 gene, the URA3 gene, the yeast transposable Ty element, and the 28S transcribed region of rDNA. These plasmids allowed us to detect rhis4 transcripts as well as detect other pol II and pol I transcripts which served as controls. The HIS4 plasmid was restricted with EcoRI, which yields a fragment expected to hybridize with the 32P-labeled HIS4 or rhis4 mRNA as well as a larger, vector fragment that contains the intact URA3 gene. The Ty plasmid was restricted with BglII. Several BglII sites are contained in the DNA of the Ty element and should hybridize to the Ty transcript. The plasmid containing the 28S rDNA was restricted with EcoRI, which generates one fragment that will hybridize with rRNA.

As shown in Fig. 4A, cells labeled with [α-32P]UTP in the presence of α-amanitin generate less HIS4, URA3, and Ty mRNAs than cells labeled with [α-32P]UTP in the absence of α-amanitin. This result indicates that these genes are transcribed by pol II, as expected. In contrast, cells labeled with [α-32P]UTP in the absence or presence of α-amanitin produce similar amounts of the rhis4 mRNA and similar amounts of rRNA. Figure 4B shows the quantitation of these data whereby the amounts of the HIS4, rhis4, and Ty mRNAs are normalized to the level of hybridized rRNA. The relative levels of mRNAs isolated from the cells incubated in the absence of α-amanitin are expressed as 100%. Approximately 90% of HIS4 and 85% of Ty transcription is inhibited by 100 μg of α-amanitin per ml. In contrast, rhis4 transcription is not affected by α-amanitin. This results suggests that at least a significant portion of rhis4 transcription is resistant to α-amanitin and therefore is under the control of the pol I promoter.

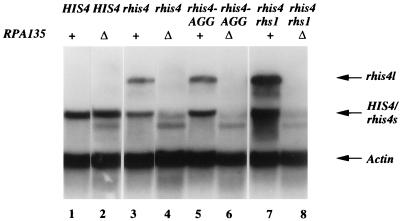

The RPA135 gene, which encodes the second-largest subunit of pol I (60), is essential for the transcription of rDNA. A deletion of the RPA135 gene causes cell death. However, an RPA135 deletion strain can be rescued by having an rDNA cistron transcribed from a pol II promoter which is provided by a unit repeat of 35S rDNA fused to the GAL7 promoter. Thus, the rpa135Δ strain can grow in medium containing galactose, which activates the GAL7 promoter to transcribe rDNA (44). We used an rpa135Δ rhis4 GAL7-rDNA strain to obtain evidence whether pol I is responsible for the transcription of the majority of rhis4 mRNA. The rationale was that if some of rhis4 mRNA is transcribed by pol II, this amount of rhis4 mRNA should not be altered by the rpa135Δ mutation. In contrast, if transcription of rhis4 is under the control of pol I, rhis4 mRNA should be absent in an rpa135Δ strain. Total RNA was isolated from strains containing the rpa135Δ mutation or the wild-type RPA135 gene and was analyzed by Northern blot analysis. Figure 5 shows that HIS4 transcription is not affected by a deletion of the RPA135 gene (lanes 1 and 2). In contrast, there is no rhis4l mRNA detected in the rpa135Δ strain (lanes 3 and 4), indicating that rhis4l is promoted by pol I. There is a significant reduction of rhis4s mRNA detected in the rpa135Δ strain (lanes 3 and 4), suggesting that at least the majority of rhis4s transcription is promoted by pol I. The remaining rhis4s transcript is most likely a result of transcription from an overlapping pol II promoter in the rDNA pol I promoter region as previously reported (9).

FIG. 5.

Northern blot analysis of rhis4 transcripts in an rpa135Δ genetic background. RPA135+ and rpa135Δ strains were cultured in YEPG (galactose) medium, and then total RNA was isolated and analyzed by Northern blotting as described in Materials and Methods. Lanes: 1, HIS4 (HJ332); 2, HIS4 rpa135Δ (HJ346); 3, rhis4 (HJ322); 4, rhis4 rpa135Δ (HJ350); 5, rhis4-AGG (HJ399); 6, rhis4-AGG rpa135Δ (HJ354); 7, rhis4 rhs1 (HJ364); 8, rhis4 rhs1 rpa135Δ (HJ442). The band observed in the rpa135Δ strains that migrates faster than the HIS4 and rhis4s mRNA is a result of nonspecific cross-hybridization between an unknown RNA species derived from plasmid pNOY102 and the actin probe.

The rate of rhis4 transcription is higher than that of HIS4.

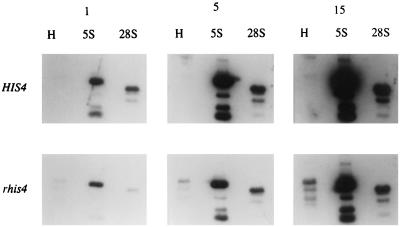

Pol I transcription of rhis4 is expected to generate uncapped mRNA. Thus, rhis4 mRNA should represent the decapped intermediate form of mRNA in the yeast mRNA degradation process and should be degraded more quickly than pol II-promoted, capped HIS4 mRNA. Nevertheless, the combined steady-state level of rhis4s and rhis4l is nearly comparable to that of HIS4 mRNA. We therefore determined whether the steady-state level of rhis4 mRNA is an underrepresentation of the rate of transcription at rhis4 by comparing it to the rate of HIS4 transcription (Fig. 6). Total 32P-labeled RNAs were isolated from permeabilized cells after being labeled with [α-32P]UTP for 1, 5, or 15 min. For these experiments, total RNA isolated from the HIS4 strain or the rhis4 strain was used as a probe in Southern hybridization to immobilized DNA fragments corresponding to the coding region of the HIS4 gene, the transcribed region of 5S rDNA (as a pol III transcription control), and the transcribed region of 28S rDNA (as a pol I transcription control). The restricted, immobilized DNA used for the HIS4/rhis4 and 28S analysis is the same as described for Fig. 4. For the 5S analysis in Fig. 6, a plasmid containing the 2.5-kb EcoRI rDNA enhancer/promoter region was restricted with EcoRI and NdeI. The slower-migrating fragment (approximately 2.0 kb) contains the 5S gene free of other encoded rRNA sequences.

FIG. 6.

Time course of HIS4 and rhis4 mRNA synthesis by nuclear run-on transcription assay. Yeast strains TD28 (HIS4) and TD237 (rhis4) were permeabilized, and aliquots of cells were labeled with [α-32P]UTP for 1, 5, or 15 min. 32P-labeled total RNA was isolated and used as probes for Southern hybridization to immobilized HIS4 (H), 5S, and 28S DNA fragments.

As shown in Fig. 6, the synthesis rates of both 5S rRNA and 28S rRNA appear quite high, probably as a result of multiple copies of these genes in the yeast genome. HIS4 mRNA is barely detectable even after 15 min of labeling with [α-32P]UTP. In contrast, rhis4 mRNAs can be easily detected after 5 min of labeling with [α-32P]UTP. This result suggests that the synthesis rate of the rhis4 mRNA is higher than that of the HIS4 mRNA despite the near equivalence of the steady-state levels. These data indicate that the lower level of the rhis4 mRNA detected on Northern blots does not reflect the higher transcriptional level, presumably due to rapid decay of uncapped mRNAs.

Mutations in the XRN1 gene increases the abundance of rhis4 mRNAs.

It has been reported that XRN1 plays a critical role in mRNA decay after decapping (21, 27, 40). Thus, we reasoned that if the pol I-promoted rhis4 mRNA is uncapped and rapidly degraded, rhis4 mRNA would be predicted to accumulate in an xrn1Δ strain. Total RNA was isolated from strains containing either an xrn1Δ mutation or the wild-type XRN1 gene and analyzed by Northern blots analysis. Figure 7 shows that the relative amount of the HIS4 mRNA is approximately 50% higher in an xrn1Δ strain (lane 6) than in an XRN1 strain (lane 2). In contrast, the combined levels of the rhis4s and rhis4l mRNAs are approximately ninefold higher in the xrn1Δ strain (8.4-fold for rhis4s mRNA and 9.6-fold for rhis4l mRNA) than in an XRN1+ strain (compare lanes 3 and 7).

FIG. 7.

Effects of mutations in XRN1 and UPF1 on HIS4 and rhis4 mRNA levels. (A) Total RNA was isolated from different yeast strains and subjected to Northern blot analysis as described in Materials and Methods. Total RNA was isolated from the following yeast strains: HH879 (which contains the HIS4+ gene on a high-copy-number YEp24 vector; lane 1); TD28 (HIS4+; lane 2); TD237 (rhis4; lane 3); HJ291 (rhis4-AGG; lane 4); HJ35 (rhis4 rhs1 [xrn1], lane 5); HJ556 (HIS4+ xrn1Δ; lane 6); HJ549 (rhis4 xrn1Δ; lane 7); HJ569 (rhis4-AGG xrn1Δ; lane 8); HH880 (HIS4+ upf1Δ; lane 9); HH881 (rhis4 upf1Δ; lane 10); and HH882 (rhis4-AGG upf1Δ; lane 11). wt, wild type. (B) Bar graph illustrating the quantitation of HIS4 or rhis4 mRNA to actin mRNA levels for each lane in panel A as described in Materials and Methods. The ratio of HIS4+ mRNA to actin mRNA in lane 2 represents the standard 100% level.

Several suppressor mutations that enhance the expression of the rhis4 gene at the level of transcription have been isolated (28). As expected, rhs1 corresponds to a mutation in the XRN1 gene. Figure 2 shows that the transcription initiation sites of the rhis4 mRNA in the parent strain and the rhs1 strain are identical and correspond to the predicted pol I start site. In addition, an approximate 10-fold increase in the combined level of rhis4 mRNAs (7.2-fold for rhis4s mRNA and 12.8-fold for rhis4l mRNA) is observed in the rhs1 (xrn1) mutant genetic background (Fig. 7; compare lanes 3 and 5), consistent with that observed in the xrn1Δ strain. This increase in rhis4 mRNA levels is also RPA135 dependent (Fig. 5, lanes 7 and 8). The fact that a mutation in xrn1 has such a specific and large effect on the level of rhis4 mRNAs suggests that the pol I promotion of rhis4 transcription leads to production of uncapped mRNA which is rapidly degraded. The effect of an xrn1 mutation is then to reduce the cellular levels of 5′-to-3′ exonuclease activity that results in stabilization of the uncapped rhis4 mRNAs.

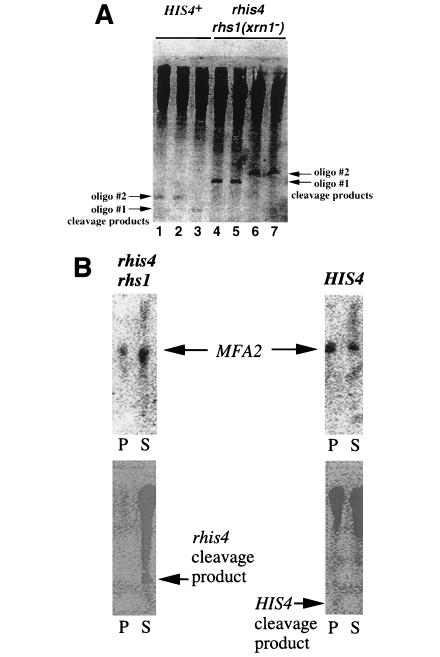

rhis4 mRNA that accumulates in an xrn1 strain is not immunoprecipitated with anticap antiserum.

To directly determine if the rhis4 mRNA that accumulates in the rhs1 (xrn1) strain is uncapped, we immunoprecipitated the rhis4 mRNA with antiserum directed against the cap structure (42). For these experiments, total RNA was isolated from cells, hybridized to an oligonucleotide that is complementary to the HIS4 and rhis4 mRNAs, and digested with RNase H. After immunoprecipitation, RNA was recovered from the pellets and supernatants and analyzed by Northern blot analysis using a 32P-labeled probe that is complementary to positions −50 to +97 in the HIS4 and rhis4 mRNAs. This procedure was used as an attempt to maximize the efficiency of immunoprecipitation (41). As an internal control for immunoprecipitation, we also probed for the MFA2 gene.

Prior to immunoprecipitation, we characterized the RNase H cleavage reaction and cleavage product, using two different oligonucleotides that hybridize to two different region of the HIS4 coding region. Oligonucleotide 1 is complementary to nt +47 to +66 in the HIS4 coding region, whereas oligonucleotide 2 is complementary to nt +90 to +111. As shown in Fig. 8A, oligonucleotide 1 generates a smaller RNase H cleavage product than oligonucleotide 2 when hybridized with total RNA from either a HIS4+ or an rhis4 xrn1Δ strain. This is expected, as the former oligonucleotide is complementary to sequences that are located further upstream in the HIS4 coding region. The RNase H cleavage products generated from the rhis4 xrn1Δ strain are also larger than the corresponding RNase H cleavage products which were generated from the HIS4+ strain. This is consistent with the rhis4 leader region being 40 nt longer than the HIS4 leader (Fig. 2). The slower-migrating material observed in Fig. 8A presumably represents either the reciprocal HIS4 or rhis4 mRNA, RNase H cleavage product, or full-length mRNA that did not hybridize with an oligonucleotide.

FIG. 8.

(A) Total RNA from a HIS4 strain and an rhis4 rhs1 (xrn1) strain were hybridized with oligonucleotide (oligo) 1 or 2, complementary to the HIS4 coding region from nt +47 to +66 or +90 to +111, respectively. RNA-DNA hybrids were treated with RNase H followed by electrophoresis in 6% acrylamide gels containing 8 M urea. Gels were then subjected to Northern blot analysis using an antisense RNA probe complementary to positions −50 to +97 in the HIS4 gene. Lanes: 1 and 2, total RNA from a HIS4+ strain hybridized with oligonucleotide 2 and cleaved with RNase H; 3, total RNA from a HIS4+ strain hybridized with oligonucleotide 1 and cleaved with RNase H; 4 and 5, total RNA from an rhis4 rhs1 (xrn1) strain hybridized with oligonucleotide 1 and cleaved with RNase H; 6 and 7, total RNA from an rhis4 rhs1 (xrn1) strain hybridized with oligonucleotide 2 and cleaved with RNase H. (B) Immunoprecipitation of HIS4 and rhis4 mRNAs with anticap antiserum. Total RNA isolated from different strains was hybridized with oligonucleotide 2 (complementary to the HIS4 coding region between positions +90 and +111), digested with RNase H, and immunoprecipitated with anticap antiserum as described in Materials and Methods. RNAs recovered from pellets (P) and supernatants (S) were analyzed by Northern blot analysis using two different probes, an antisense RNA complementary to positions −50 to +97 in the HIS4 gene (bottom panels) and a random-primed probe complementary to the MFA2 gene (top panels). The first two lanes represent precipitated and unprecipitated RNAs, respectively, from an rhis4 rhs1 (xrn1) strain (HJ35). The last two lanes represent precipitated and unprecipitated RNAs from the HIS4+ wild-type strain, TD28. The arrows in the bottom panels point to rhis4 and HIS4 mRNA RNase H cleavage products and correspond to the cleavage products characterized in panel A.

For the immunoprecipitation reactions presented in Fig. 8B, we used oligonucleotide 2. The HIS4 cleavage product, which is presumably capped, could be detected in the immunoprecipitate and was not observed in the supernatant, albeit the detection resolution is quite low (Fig. 8B). In contrast, the rhis4 cleavage product is not observed in the immunoprecipitate; rather, the rhis4 cleavage product remained in the supernatant. As a control for these reactions, we found that the majority of the MFA2 mRNA isolated from an XRN1+ strain was immunoprecipitated with the anticap antiserum, whereas more MFA2 mRNA from an rhs1 (xrn1) strain remained in the supernatant, suggesting that rhs1 (xrn1) stabilizes the decapped form of the MFA2 mRNA, which does not immunoprecipitate. These results are consistent with the notion that the rhis4 mRNA which accumulates in the rhs1 (xrn1) strain is uncapped.

Construction of rhis4-AGG allele.

The first three nucleotides from the pol I start position in rDNA are predicted to introduce an upstream and out-of-frame AUG codon at the immediate 5′ end of the rhis4 mRNA (33). Thus, rhis4 mRNA may be degraded by the nonsense-mediated decay pathway, and the rhs1 or xrn1Δ mutation may stabilize the nonsense-mediated decay of rhis4 mRNA (21). Therefore, we mutated the upstream and out-of-frame AUG to AGG by site-directed mutagenesis (for details, see Materials and Methods). The reason for choosing to mutate the AUG to AGG is that AGG has been identified as the first three nucleotides in precursor rRNA from Drosophila and Xenopus cells (15, 37). Therefore, we reasoned that an AUG-to-AGG change might not alter the start site for pol I transcription. The presence of this mutation was confirmed by DNA sequencing (data not shown), and the corresponding rhis4 allele (rhis4-AGG) was inserted and replaced for the wild-type HIS4 gene on chromosome III.

Figure 2 shows that the AGG mutation does not affect the transcription initiation site of rhis4-AGG mRNAs, as determined by primer extension analysis. rhis4-AGG also generates two mRNA species (Fig. 5, lane 5), rhis4-AGGs and rhis4-AGGl, with the same mobilities as the rhis4s and rhis4l mRNAs, respectively. In addition, the amounts of the rhis4-AGG transcripts are similar to those of the rhis4 messages and are also sensitive to an rpa135Δ mutation (Fig. 5). The xrn1Δ mutation also results in a comparable increase in the combined level of the rhis4-AGGs and rhis4-AGGl transcripts (Fig. 7; compare lanes 4 and 8). Finally, to rule out nonsense-mediated decay as a mechanism for destabilizing rhis4 mRNA, we measured the levels of rhis4 and rhis4-AGG transcripts in a upf1Δ strain. Figure 7 shows that a upf1Δ mutation does not result in an increase in rhis4s or rhis4-AGGs mRNA or rhis4l and rhis4-AGGl transcripts, which are bicistronic (compare lanes 3 and 4 to lanes 10 and 11, respectively). These data suggest that a large majority of rhis4 transcription products are unstable, not as a result of nonsense-mediated decay but due to the absence of a cap structure at the 5′ end of this pol I-promoted message.

Translational expression of rhis4 and rhis4-AGG strains.

Our analysis indicates that an rhs1 (xrn1) mutant strain accumulates significant levels of intact and uncapped rhis4 transcripts. It has been reported that in a number of eukaryotic organisms, certain mRNAs can be translated by a cap-independent mechanism of translation initiation (38, 45). Therefore, an important question to address is whether yeast cells also have a cap-independent mechanism of translating mRNA.

We measured the in vivo translational expression of the rhis4 and rhis4-AGG transcripts in different genetic backgrounds. The level of His4 protein was quantitated relative to the level of eIF-2γ by Western blot analysis using antibodies directed against each protein. As shown in Fig. 9, the His4 protein level of the rhis4 strain is approximately 3% that of a HIS4+ strain (compare lanes 2 and 3). The amount of His4 protein in the rhis4-AGG strain is approximately 2.5-fold higher than that in the rhis4 strain (compares 3 and 4) but only approximately 7.5% of wild-type levels (compare lanes 2 and 4). When we insert the 50-nt leader sequence derived from the rRNA portion of rhis4-AGG at positions −51 to −50 of the HIS4+ leader region, we observe near wild-type levels of His4 protein (approximately 80 to 90% of wild-type levels), indicating that this sequence is not inhibitory to translation (data not shown). The finding that the level of rhis4-AGG mRNAs represents between 50 and 100% of wild-type HIS4 mRNAs (Fig. 7) but the level of translation is a fraction of the wild-type protein level (7 to 8% [Fig. 9]) suggests that rhis4-AGG mRNAs are not translated efficiently.

FIG. 9.

Western blot analysis of the His4 protein produced in HIS4 and rhis4 strains. (A) Yeast crude extracts were isolated and analyzed by Western blot analysis using antibodies directed against His4 protein and antibodies directed against eIF-2γ. Crude extracts were prepared from the following yeast strains: HH879 (which contains the HIS4+ gene on a high-copy-number YEp24 vector; lane 1); TD28 (HIS4+; lane 2); TD237 (rhis4; lane 3); HJ291 (rhis4-AGG; lane 4); HJ35 (rhis4 rhs1 [xrn1]; lane 5); HJ556 (HIS4+ xrn1Δ; lane 6); HJ569 (rhis4-AGG xrn1Δ; lane 7); and HJ549 (rhis4 xrn1Δ; lane 8). (B) Bar graph illustrating the quantitation of His4 protein levels to eIF-2γ protein levels for each lane in panel A as described in Materials and Methods. The ratio of His4 protein to eIF-2γ protein levels in lane 2 represents the standard 100% level. wt, wild type.

This latter point is established further in Fig. 9. The amount of His4 protein measured from an rhis4-AGG xrn1Δ strain is approximately fourfold higher than that in the rhis4-AGG parent strain (compare lanes 4 and 7). However, the level of His4 protein in the rhis4-AGG xrn1Δ strain is only approximately 32% of that detected in a HIS4 wild-type strain (Fig. 9; compare lanes 2 and 7) despite the level of rhis4-AGG mRNA being approximately 10-fold higher than that of wild-type HIS4 mRNA (Fig. 7). This is not a result of the inability of overexpressed HIS4 mRNA to be translated to high levels. As a control, we expressed the HIS4 wild-type gene on a high-copy-number vector. The level of HIS4 mRNA in this strain is approximately eightfold higher than the level of HIS4 mRNA in the wild-type parent strain (Fig. 7; compare lanes 1 and 2). This increase is comparable to the total level of rhis4-AGG transcripts in an rhs1 (xrn1) mutant strain. This eightfold increase in HIS4 transcript levels results in a threefold increase in the level of intact His4 protein and an assortment of abundant, cross-reactive, and presumed proteolyzed fragments of His4 protein. Thus, the level of intact His4 protein in an rhis4-AGG xrn1Δ strain is only 10% of the level of intact His4 protein level (330 versus 32%) when we control for mRNA levels (Fig. 9; compare lanes 1 and 7). Judging from the abundance of proteolyzed fragments in lane 1, this 10-fold difference would appear to be grossly underestimated. Thus, the simplest explanation for the inability to see abundant His4 protein levels in an rhis4-AGG xrn1Δ strain is that these pol I-promoted and capless mRNAs are not efficiently translated in yeast.

DISCUSSION

Pol I-promoted uncapped rhis4 mRNA is degraded rapidly.

We have put the HIS4 gene under the transcriptional control of pol I to generate a species of mRNA that is predominately capless in yeast. We have shown that the majority of rhis4 transcripts is transcribed by pol I and mutations in the XRN1 gene increases the abundance of the pol I-promoted rhis4 mRNAs. Our analysis indicates that the rhis4 gene produces capless mRNA that is rapidly degraded by the Xrn1, 5′-to-3′ exonuclease. Elegant studies in the Parker laboratory have mapped out the deadenylation-dependent pathway for mRNA degradation in the cytoplasm (6). The first step in degradation is deadenylation which leads to decapping and subsequent 5′-to-3′ exonucleolytic degradation of mRNA. Furthermore, it has been shown that mutations in XRN1 lead to an increase in mRNA degradation intermediates (27). Our observations that mutations in the xrn1 gene lead to a 9- to 10-fold increase in the combined steady-state level of rhis4 mRNAs indicates that at least 90% of the mRNA transcribed at rhis4 is rapidly degraded by Xrn1.

A second pathway for mRNA degradation exists in yeast commonly referred to as the nonsense-mediated decay pathway that appears to be conserved in other eukaryotic organisms (21, 46, 59). This pathway is deadenylation independent and is believed to trigger mRNA degradation as a result of a premature nonsense codon in the coding region. The fact that the level of the rhis4-AGG mRNA is similar to that of the rhis4 mRNA and the amount of bicistronic rhis4l and rhis4-AGGl mRNA is not increased in a upf1Δ mutant argues against the rhis4 mRNA being degraded by a nonsense-codon mediated decay pathway. The instability of the rhis4 transcript must be due to the mRNA lacking a cap structure. This is confirmed by our immunoprecipitation analysis using anticap antibodies. Thus, our analysis confirms and extends other studies on mRNA decay in yeast which suggest that removal of the cap is the crucial step for mRNA decay and that Xrn1 is the major 5′-to-3′ exonuclease involved in decay.

3′-end formation of a pol I-promoted rhis4 mRNA.

Our analysis brings out some interesting observations on the nature of 3′-end formation of mRNA in yeast. Surprisingly, pol I-promoted HIS4 expression produces mRNA species that terminate at the 3′ noncoding region of pol II genes. This would suggest that termination of transcription at these regions is independent of the RNA polymerase transcribing the DNA. In addition, the mRNAs produced appear to be polyadenylated based on oligo(dT) binding and PCR methodology for mapping the 3′ end of the transcript. These observations further support the notion that transcription termination at the 3′ ends of pol II genes in yeast is dictated not by a polymerase termination sequence but by polyadenylation signals (5), as the termination signals for pol I transcription are predicted to be different and presumably not present in the 3′ noncoding regions of pol II genes (35). Interestingly, the polyadenylation site for the rhis4s mRNA is the same as one of those for the HIS4 mRNA (137 nt downstream of translation stop codon of HIS4). The polyadenylation sites for the rhis4l mRNA are located at the 3′ UTR of the YCL184 gene, suggesting that it is also possible that the rhis4l and YCL184 transcripts have the same polyadenylation site(s).

Considerable controversy surrounds the requirement of pol II transcription for polyadenylation. Grummt and Skinner (19) reported that pol I-promoted chloramphenicol acetyltransferase mRNAs were polyadenylated in mouse 3T6 cells. In contrast, it has been shown that pol I-promoted herpes simplex virus tk mRNAs were not polyadenylated in monkey COS-7 cells (53). This latter observation is more consistent with recent studies which demonstrated that the CTD of the pol II large subunit is required for efficient cleavage at the poly(A) site in vivo (39). It was also shown that the CTD might associate with CPSF and CstF but not poly(A) polymerase (39). However, our data indicate that at least in yeast, the polyadenylation machinery is able to function independently of pol II transcription. Instead, our data indicate that sequences in the 3′ noncoding region of genes, such as HIS4 and YCL184, support the polyadenylation process regardless of the RNA polymerase transcribing the DNA.

Another interesting observation made in our analysis is that two transcripts accumulate as a result of pol I transcription of HIS4: rhis4s and rhis4l. rhis4l is bicistronic and presumably is a result of the inability of pol I to terminate efficiently at the 3′ end of the HIS4 gene. One model for termination of pol II transcription in yeast is that it is an indirect consequence of nascent transcripts being polyadenylated through signals located in the 3′ noncoding region (5). Alternatively, as suggested for mammalian RNA polymerase II termination, a strong termination signal would be the combination of an efficient polyadenylation site and a strong pause site (36, 47). There are a number of possibilities as to why we observe bicistronic rhisl mRNA as a result of pol I transcription. One possibility is that the polyadenylation signals present at HIS4 are not designed to promote a rate of polyadenylation coincident with the apparent higher rate of transcription associated with pol I transcription at HIS4 (Fig. 6). Alternatively, pol I does not pause effectively in this region, and thus the mRNA structure may not always be conducive to efficient polyadenylation/termination. Either way, the rhis4l transcript is produced by default, at the 3′ end of YCL184.

The 5′ cap is required for efficient translation initiation in vivo.

One of the major goals of our analysis was to determine if yeast has a cap-independent mechanism of translation initiation. The requirement for a cap in translation initiation is strongly supported by in vitro studies. Studies which have addressed the requirement for a cap in in vivo translation initiation have led to conflicting results. For example, it has been shown that the 5′ cap structure, m7Gppp, of mature eukaryotic mRNA is required for efficient translation in microinjected oocytes (54). However, the mRNA injected lacked a poly(A) tail, which has recently been suggested to be important for translation initiation (reference 56 and references within). Grummt and Skinner (19) have shown that in mouse (3T6) cells, pol I-promoted chloramphenicol acetyltransferase mRNAs contained a poly(A) tail and were poorly expressed. However, it was not established if the mRNA lacked a 5′ cap structure. Studies of HeLa cells have shown that pol III-promoted transcripts are associated with polysomes and translated even though these transcripts were neither capped nor polyadenylated (20), which is at odds with recent models for eukaryotic translation initiation that suggest synergy between the 5′ and 3′ ends of mRNA (18, 57). Our analysis of pol I-promoted HIS4 expression, especially in an rhs1 (xrn1) or xrn1Δ genetic background, afforded the ability to produce a substantial level of predominantly capless mRNA that was polyadenylated. The ability of a mutation in XRN1 to stabilize this rhis4 mRNA strongly suggests that the mRNA is degraded in the cytoplasm, as Xrn1 is believed to be cytoplasmically located (26). Thus, rhis4 mRNAs presumably are available to the translational machinery that is cytoplasmically located. Our analysis indicates that rhis4-AGG mRNA is translated at approximately 7 to 10% of the level of capped HIS4 mRNA (Fig. 9; compare lanes 4 to 2 and lanes 7 to 1). This level may even be lower as approximately one-third of this His4 protein is still detected in an rpa135Δ strain (data not shown) and presumably results from translation of pol II promoted rhis4 transcripts that are present at low level (Fig. 5). Nevertheless, quantitation of the level of His4 protein as presented here (Fig. 9) strongly indicates that pol I-promoted, capless mRNAs lack the ability to be efficiently translated in yeast and therefore suggests that a cap-dependent mechanism is preferred in yeast for efficient translation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The first two authors contributed equally to this work.

We thank T. Blumenthal, P. Cherbas, J. Jaehning, and N. Pace for helpful discussions during the course of this work. We thank J. Warner for the rDNA promoter/enhancer plasmid, M. Culbertson for the upf1::URA3 plasmid, C. Dykstra for the dst2 (xrn1)::URA3 plasmid, C. Thompson for the pCT3 yeast genomic library, M. Nomura for the rpa-135Δ strains, E. Lund and R. Parker for the anticap antiserum, and R. Parker and C. Decker for advice on immunoprecipitation of mRNA with the anticap antibody.

This work was supported by Public Health Service grant GM32263 from the National Institutes of Health awarded to T.F.D.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bayev A A, Georgiev O I, Hadjiolov A A, Kermekchiev M B, Nikolaev N, Skryabin K G, Zakharyev V M. The structure of the yeast ribosomal genes. 2. The nucleotide sequence of the initiation site for ribosomal RNA transcription. Nucleic Acids Res. 1980;8:4919–4926. doi: 10.1093/nar/8.21.4919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beelman C A, Parker R. Degradation of mRNA in eukaryotes. Cell. 1995;81:179–183. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90326-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bernstein P, Ross J. Poly(A), poly(A) binding protein and the regulation of mRNA stability. Trends Biochem Sci. 1989;14:373–377. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(89)90011-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boeke J D, Lacroute F, Fink G R. A positive selection of mutants lacking orotidine-5′-phosphate decarboxylase activity in yeast: 5-fluoro-orotic acid resistance. Mol Gen Genet. 1984;197:345–346. doi: 10.1007/BF00330984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Butler S J, Platt T. RNA processing generates the mature 3′ end of yeast CYC1 messenger RNA in vitro. Science. 1988;242:1270–1274. doi: 10.1126/science.2848317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Caponigro G, Parker R. Multiple functions for the poly(A)-binding protein in mRNA decapping and deadenylation in yeast. Genes Dev. 1995;9:2421–2432. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.19.2421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cigan A M, Pabich E K, Donahue T F. Mutational analysis of the HIS4 translational initiator region in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1988;8:2964–2975. doi: 10.1128/mcb.8.7.2964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Connelly S, Manley J L. A functional mRNA polyadenylation signal is required for transcription termination by RNA polymerase II. Genes Dev. 1988;2:440–452. doi: 10.1101/gad.2.4.440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Conrad-Webb H, Butow R A. A polymerase switch in the synthesis of rRNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:2420–2428. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.5.2420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Donahue T F, Cigan A M. Genetic selection for mutations that reduce or abolish ribosomal recognition of the HIS4 translational initiator region. Mol Cell Biol. 1988;8:2955–2963. doi: 10.1128/mcb.8.7.2955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Donahue T F, Cigan A M, Pabich E K, Castilho-Valavicius B. Mutations at a Zn(II) finger motif in the yeast eIF-2b gene alter ribosomal start-site selection during the scanning process. Cell. 1988;54:621–632. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(88)80006-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Donahue T F, Farabaugh P J, Fink G R. The nucleotide sequence of the HIS4 region of yeast. Gene. 1982;18:47–59. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(82)90055-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dykstra C C, Kitada K, Clark A B, Hamatake R K, Sugino A. Cloning and characterization of DST2, the gene for DNA strand transfer protein b from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:2583–2592. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.5.2583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elion E A, Warner J R. An RNA polymerase I enhancer in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1986;6:2089–2097. doi: 10.1128/mcb.6.6.2089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Financsek I, Mizumoto K, Mishima Y, Muramatsu M. Human ribosomal RNA gene: nucleotide sequence of the transcription initiation region and comparison of three mammalian genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1982;79:3092–3096. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.10.3092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fresco L D, Buratowski S. Conditional mutants of the yeast mRNA capping enzyme show that the cap enhances, but is not required for, mRNA splicing. RNA. 1997;2:584–596. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Frohman M A. Rapid amplification of complementary DNA ends for generation of full-length complementary DNAs: thermal RACE. Methods Enzymol. 1993;218:340–356. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(93)18026-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gallie D R. The cap and poly(A) tail function synergistically to regulate mRNA translational efficiency. Genes Dev. 1991;5:2108–2116. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.11.2108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grummt I, Skinner J A. Efficient transcription of a protein-coding gene from the RNA polymerase I promoter in transfected cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:722–726. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.3.722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gunnery S, Mathews M B. Functional mRNA can be generated by RNA polymerase III. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:3597–3607. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.7.3597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hagan K W, Ruiz-Echevarria M J, Quan Y, Peltz A W. Characterization of cis-acting sequences and decay intermediates involved in nonsense-mediated mRNA turnover. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:809–823. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.2.809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hagler J, Shuman S. A freeze-frameview of eukaryotic transcription during elongation and capping of nascent mRNA. Science. 1992;255:983–986. doi: 10.1126/science.1546295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hamm J, Mattaj I W. Monomethylated cap structures facilitate RNA export from the nucleus. Cell. 1990;63:109–118. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90292-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Heidmann S, Obermaier B, Vogel K, Domdey H. Identification of pre-mRNA polyadenylation sites in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:4215–4229. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.9.4215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hershey J W B. Translational control in mammalian cells. Annu Rev Biochem. 1991;60:717–755. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.60.070191.003441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heyer W-D, Johnson A W, Reinhart U, Kolodner R D. Regulation and intracellular localization of Saccharomyces cerevisiae strand exchange protein (Sep1/Xrn1/Kem1), a multifunctional exonuclease. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:2728–2736. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.5.2728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hsu C L, Stevens A. Yeast cells lacking 5′→3′ exoribonuclease 1 contain mRNA species that are poly(A) deficient and partially lack the 5′ cap structure. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:4826–4835. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.8.4826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huang, H-K., H.-J. Lo, and T. F. Donahue. Unpublished data.

- 29.Huang H-K, Yoon H, Hannig E M, Donahue T F. GTP hydrolysis controls stringent selection of the AUG start codon during translation initiation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genes Dev. 1997;11:2396–2413. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.18.2396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Izaurralde E, Lewis J, McGuigan C, Jankowska M, Darzynkiewicz E, Mattaj I W. A nuclear cap binding protein complex involved in pre-mRNA splicing. Cell. 1994;78:657–668. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90530-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jacobson A, Favreau M. Possible involvement of poly(A) in protein synthesis. Nucleic Acids Res. 1983;18:6353–6368. doi: 10.1093/nar/11.18.6353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jove R, Manley J L. Transcription initiation by RNA polymerase II is inhibited by S-adenosylhomocysteine. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1982;79:5842–5846. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.19.5842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Klemenz R, Geiduschek E P. The 5′ terminus of the precursor ribosomal RNA of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nucleic Acids Res. 1980;8:2679–2689. doi: 10.1093/nar/8.12.2679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kozak M. The scanning model for translation: an update. J Cell Biol. 1989;108:229–241. doi: 10.1083/jcb.108.2.229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lang W, Reeder R H. The REB1 site is an essential component of a terminator for RNA polymerase I in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:649–658. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.1.649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lanoix J, Acheson N H. A rabbit β-globin polyadenylation signal directs efficient termination of transcription of polyomavirus DNA. EMBO J. 1988;7:2515–2522. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb03099.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Long E O, Rebbert M L, Dawid I B. Nucleotide sequence of the initiation site for ribosomal RNA transcription in Drosophila melanogaster: comparison of genes with and without insertions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1981;78:1513–1517. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.3.1513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Macejak D G, Sarnow P. Internal initiation of translation mediated by the 5′ leader of a cellular mRNA. Nature. 1991;353:90–94. doi: 10.1038/353090a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McCracken S, Fong N, Yankulov K, Ballantyne S, Pan G, Greenblatt J, Patterson S D, Wickens M, Bentley D L. The C-terminal domain of RNA polymerase II couples mRNA processing to transcription. Nature. 1997;385:357–361. doi: 10.1038/385357a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Muhlrad D, Decker C J, Parker R. Deadenylation of the unstable mRNA encoded by the yeast MFA2 gene leads to decapping followed by 5′ to 3′ digestion of the transcript. Genes Dev. 1994;8:855–866. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.7.855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Muhlrad D, Decker C J, Parker R. Turnover mechanisms of the stable yeast PGK1 mRNA. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:2145–2156. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.4.2145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Munns T W, Liszewski M K, Tellam J T, Sims H F, Rhoads R E. Antibody-nucleic acid complexes. Immunospecific retention of globin messenger ribonucleic acid with antibodies specific for 7-methyl guanosine. Biochemistry. 1982;21:2922–2928. doi: 10.1021/bi00541a018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nagawa F, Fink G R. The relationship between the “TATA” sequence and transcription initiation sites at the HIS4 gene of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:8557–8561. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.24.8557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nogi Y, Yano R, Nomura M. Synthesis of large rRNAs by RNA polymerase II in mutants of Saccharomyces cerevisiae defective in RNA polymerase I. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:3962–3966. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.9.3962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Oh S K, Scott M P, Sarnow P. Homeotic gene Antennapedia mRNA contains 5′ noncoding sequences that confer translational initiation by internal ribosome binding. Genes Dev. 1992;6:1643–1653. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.9.1643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Peltz S W, Donahue J L, Jacobson A. A mutation in the tRNA nucleotidyltransferase gene promotes stabilization of mRNAs in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:5778–5784. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.12.5778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Proudfoot N J. How RNA polymerase II terminates transcription in higher eukaryotes. Trends Biol Sci. 1989;14:105–110. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(89)90132-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rad M R, Lutzenkirchen K, Xu G, Kleinhans U, Hollenberg C P. The complete sequence of a 11,953 bp fragment from C1G on chromosome III encompasses four new open reading frames. Yeast. 1991;7:533–538. doi: 10.1002/yea.320070513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rasmussen E B, Lis J T. In vivo transcriptional pausing and cap formation on three Drosophila heat shock genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:7923–7927. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.17.7923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sachs A B, Davis R W. Translation initiation and ribosomal biogenesis: involvement of a putitive RNA helicase and RPL46. Science. 1990;247:1077–1079. doi: 10.1126/science.2408148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sherman F, Fink G R, Lawrance C W. Methods in yeast genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Smale S T, Tjian R. Transcription of herpes simplex virus tk sequences under the control of wild-type and mutant human RNA polymerase I promoters. Mol Cell Biol. 1985;5:352–362. doi: 10.1128/mcb.5.2.352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sonenberg N. Cap-binding proteins of eukaryotic messenger RNA: functions in initiation and control of translation. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol. 1988;35:173–207. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(08)60614-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sonenberg N. Poliovirus translation. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1990;161:23–47. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-75602-3_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tarun S Z, Jr, Sachs A B. A common function for mRNA 5′ and 3′ ends in translation initiation in yeast. Genes Dev. 1995;9:2997–3007. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.23.2997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tarun S Z, Jr, Sachs A B. Association of the yeast poly(A) binding protein with translation initiation factor eIF-4G. EMBO J. 1996;15:7168–7177. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wickens M. How the messenger got its tail: addition of poly(A) in the nucleus. Trends Biochem Sci. 1990;15:277–281. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(90)90054-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wisdom R, Lee W. Translation of c-myc mRNA is required for its post-transcriptional regulation during myogenesis. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:19015–19021. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yano R, Nomura M. Suppressor analysis of temperature-sensitive mutations of the largest subunit of RNA polymerase I in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: a suppressor gene encodes the second-largest subunit of RNA polymerase I. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:754–764. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.2.754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]