Abstract

Eukaryotic protein kinases are key molecules mediating signal transduction that play a pivotal role in the regulation of various biological processes, including cell cycle progression, cellular morphogenesis, development, and cellular response to environmental changes. A total of 106 eukaryotic protein kinase catalytic-domain-containing proteins have been found in the entire fission yeast genome, 44% (or 64%) of which possess orthologues (or nearest homologues) in humans, based on sequence similarity within catalytic domains. Systematic deletion analysis of all putative protein kinase-encoding genes have revealed that 17 out of 106 were essential for viability, including three previously uncharacterized putative protein kinases. Although the remaining 89 protein kinase mutants were able to form colonies under optimal growth conditions, 46% of the mutants exhibited hypersensitivity to at least 1 of the 17 different stress factors tested. Phenotypic assessment of these mutants allowed us to arrange kinases into functional groups. Based on the results of this assay, we propose also the existence of four major signaling pathways that are involved in the response to 17 stresses tested. Microarray analysis demonstrated a significant correlation between the expression signature and growth phenotype of kinase mutants tested. Our complete microarray data sets are available at http://giscompute.gis.a-star.edu.sg/∼gisljh/kinome.

Eukaryotic cells employ signal transduction pathways to respond to various environmental stress factors and to adapt by reorganizing cellular metabolism, gene expression, cell cycle control, and morphogenesis. Protein kinases are major players in mediating signals to regulate a variety of biological processes in cellular response to environmental stresses. In fission yeast, a number of protein kinases have been shown to be involved in signal transduction, which is rapidly activated upon cells being subjected to various stress factors, for example, the oxidative stress factor H2O2 (44). The activation of the signaling pathway Wis4-Wis1-Sty1, reminiscent of the MAK-MKK3/MKK6-p38 mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase cascade in mammalian systems (44), leads to the induction of expression of a number of genes whose products are involved in the neutralization and repair of damage caused by H2O2 (11, 53). Cells defective for one of the wis4, wis1, and sty1 genes exhibit hypersensitivity to H2O2, because of failure in mediating signals to reorganize various cellular events, such as metabolism and gene expression (9, 11, 53).

A number of protein kinases involved in mediating signals during cellular response to various environmental changes have been previously characterized. At least three mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascades have been analyzed in fission yeast. While the Wis4-Wis1-Sty1 MAPK cascade is involved in the oxidative stress response, the Byr2-Byr1-Spk1 and Mhk1-Pek1-Pkm1 MAPK cascades have been shown to mediate signals in response to pheromones and ion homeostasis and cell wall integrity, respectively (40, 63). Cells containing loss-of-function mutations in these signaling molecules show either defective pheromone responses (40) or sensitivity to cell wall-degrading agents, such as β-glucanases (30, 63). Besides the involvement of MAPK cascades in response to environmental and/or cellular perturbations, a number of protein kinases implicated in response to a variety of stress factors, such as agents that block DNA replication, damage chromosomal DNA, destabilize microtubule structures, and disrupt cell wall structures, have been characterized. For example, Cds1 and Chk1 regulate cell cycle control in response to blocks to DNA replication and/or DNA damage (49). Hhp1 and Hhp2 are involved in DNA damage repair pathways (13, 19). Cells carrying mutations in these kinases display hypersensitivity to agents that block DNA replication and/or damage DNA. Bub1 and Mph1, on the other hand, regulate cell cycle control in response to defective kinetochore capture, and bub1 and mph1 mutants show hypersensitivity to microtubule poisons (7, 17). A number of protein kinases have also been reported to regulate cell wall integrity and/or ion homeostasis (Table 1), and these mutant cells exhibit sensitivities to a variety of cell wall degrading agents (see Table 1 for references).

TABLE 1.

All 106 protein kinases in the S. pombe genome

| Gene symbol | Systematic name | Viability | Process | Referencea |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ark1 | SPCC320.13c | Lethal | Mitosis and cytokinesis | 46 |

| bub1 | SPCC1322.12c | Viable | Spindle checkpoint | 7; this studyb |

| byr1 | SPAC1D4.13 | Viable | Response to pheromone | 40; this study |

| byr2 | SPBC1D7.05 | Viable | Response to pheromones | 40; this study |

| cdc2 | SPBC11B10.09 | Lethal | Cell cycle regulation | 5 |

| cdc7 | SPBC21.06c | Lethal | Mitosis and cytokinesis | 15 |

| cdk9 | SPBC32H8.10 | Lethal | Mitosis | 45; this study |

| cdr1 | SPAC644.06c | Viable | Cell cycle regulation | 78; this study |

| cdr2 | SPAC57A10.02 | Viable | Cell cycle regulation | 78; this study |

| cds1 | SPCC18B5.11c | Viable | DNA replication checkpoint | 38; this study |

| cek1 | SPCC1450.11c | Viable | Unknown | 55; this study |

| chk1 | SPCC1259.13 | Viable | DNA replication checkpoint | 71; this study |

| cka1 | SPAC23C11.11 | Lethal | Polarized growth | 62 |

| cki1 | SPBC1347.06c | Viable | Unknown | 72; this study |

| cki2 | SPBP35G2.05c | Viable | Unknown | 72; this study |

| cki3 | SPAC1805.05 | Viable | Unknown | 72; this study |

| cmk1 | SPACUNK12.02c | Viable | Regulation of cell shape | 48; this study |

| cmk2 | SPAC23A1.06c | Viable | Response to oxidative stress | 48; this study |

| crk1 | SPBC19F8.07 | Lethal | Regulation of transcription | 10 |

| csk1 | SPAC1D4.06c | Viable | Cell cycle regulation | 36; this study |

| dsk1 | SPBC530.14c | Viable | Regulation of pre-mRNA splicing | 64; this study |

| fin1 | SPAC19E9.02 | Viable | Mitosis and cellular morphogenesis | 27; this study |

| gad8 | SPCC24B10.07 | Viable | Unknown | 34; this study |

| gsk3 | SPAC1687.15 | Viable | Mitosis and cytokinesis | 47; this study |

| gsk31 | SPBC8D2.01 | Viable | Unknown | 77; this study |

| hhp1 | SPBC3H7.15 | Viable | DNA repair | 13; this study |

| hhp2 | SPAC23C4.12 | Viable | DNA repair | 19; this study |

| hri1 | SPAC20G4.03c | Viable | Negative regulator of translation initiation | 80; this study |

| hri2 | SPAC222.07c | Viable | Negative regulator of translation initiation | 80; this study |

| hsk1 | SPBC776.12c | Lethal | Chromosome organization | 33 |

| kin1 | SPBC4F6.06 | Viable | Cell wall organization | 29; this study |

| ksg1 | SPCC576.15c | Lethal | Cell wall organization | 41 |

| lkh1 | SPAC1D4.11c | Viable | Response to oxidative stress | 25; this study |

| lsk1 | SPAC2F3.15 | Viable | Mitosis and cytokinesis | 23a; this study |

| mde3 | SPBC8D2.19 | Viable | Sporulation | 1; this study |

| mek1 | SPAC14C4.03 | Viable | Meiotic recombination | 59; this study |

| mik1 | SPBC660.14 | Viable | DNA replication checkpoint | 28; this study |

| mkh1 | SPAC1F3.02c | Viable | Cell wall organization | 57; this study |

| mph1 | SPBC106.01 | Viable | Mitotic spindle checkpoint | 17; this study |

| nak1 | SPBC17F3.02 | Lethal | Polarized growth and maintenance | 20; this study |

| oca2 | SPCC1020.10 | Viable | Unknown | 65; this study |

| orb6 | SPAC821.12 | Lethal | Regulation of cell shape | 68 |

| pck1 | SPAC17G8.14c | Viable | Cell wall organization | 26; this study |

| pck2 | SPBC12D12.04c | Viable | Cell wall organization | 26; this study |

| pef1 | SPCC16C4.11 | Viable | Regulation of G1/S transition | 66; this study |

| pek1 | SPBC543.07 | Viable | Cell wall integrity | 63; this study |

| pit1 | SPAC3C7.06c | Viable | Sporulation | 1; this study |

| pka1 | SPBC106.10 | Viable | Regulation of glycolysis | 79; this study |

| plo1 | SPAC23C11.16 | Lethal | Mitosis and cytokinesis | 43 |

| pmk1 | SPBC119.08 | Viable | Cell wall integrity maintenance | 67; this study |

| pom1 | SPAC2F7.03c | Viable | Polarized growth and cytokinesis | 2; this study |

| ppk1 | SPAC110.01 | Viable | Unknown | This study |

| ppk2 | SPAC12B10.14c | Viable | Unknown | This study |

| ppk3 | SPAC15A10.13 | Viable | Unknown | This study |

| ppk4 | SPAC167.01 | Viable | Unknown | This study |

| ppk5 | SPAC16C9.07 | Viable | Unknown | This study |

| ppk6 | SPAC1805.01c | Viable | Unknown | This study |

| ppk8 | SPAC22G7.08 | Viable | Unknown | This study |

| ppk9 | SPAC23H4.02 | Viable | Unknown | This study |

| ppk10 | SPAC29A4.16 | Viable | Unknown | This study |

| ppk11 | SPAC2C4.14c | Viable | Unknown | This study |

| ppk13 | SPAC3H1.13 | Viable | Unknown | This study |

| ppk14 | SPAC4G8.05 | Viable | Unknown | This study |

| ppk15 | SPAC823.03 | Viable | Unknown | This study |

| ppk16 | SPAC890.03 | Viable | Unknown | This study |

| ppk18 | SPAPB18E9.02c | Viable | Unknown | This study |

| ppk19 | SPBC119.07 | Viable | Unknown | This study |

| ppk20 | SPBC16E9.13 | Viable | Unknown | This study |

| ppk21 | SPBC1778.10c | Viable | Cytokinesis | A.B., J.L., and M.K.B., unpublished data |

| ppk22 | SPBC1861.09 | Viable | Unknown | This study |

| ppk23 | SPBC18H10.15 | Viable | Unknown | This study |

| ppk24 | SPBC21.07c | Viable | Unknown | This study |

| ppk25 | SPBC32C12.03c | Viable | Unknown | This study |

| ppk26 | SPBC336.14c | Viable | Unknown | This study |

| ppk27 | SPBC337.04 | Viable | Unknown | This study |

| ppk28 | SPBC36B7.09 | Viable | Unknown | This study |

| ppk29 | SPBC557.04 | Viable | Unknown | This study |

| ppk30 | SPBC6B1.02 | Viable | Unknown | This study |

| ppk31 | SPBC725.06c | Viable | Unknown | This study |

| ppk32 | SPBP23A10.10 | Viable | Unknown | This study |

| ppk33 | SPCC162.10 | Viable | Unknown | This study |

| ppk34 | SPCC1919.01 | Viable | Unknown | This study |

| ppk35 | SPCC417.06c | Viable | Unknown | This study |

| ppk36 | SPCC63.08c | Viable | Unknown | This study |

| ppk37 | SPCC70.05c | Lethal | Unknown | This study |

| ppk38 | SPCP1E11.02 | Viable | Unknown | This study |

| prp4 | SPCC777.14 | Lethal | Regulation of pre-mRNA splicing | 52 |

| psk1 | SPCC4G3.08 | Viable | Unknown | 37; this study |

| ran1 | SPBC19C2.05 | Lethal | Negative regulator of meiosis | 6 |

| sck1 | SPAC1B9.02c | Viable | Cell proliferation | 23; this study |

| sck2 | SPAC22E12.14c | Viable | Unknown | 15a; this study |

| shk1 | SPBC1604.14c | Lethal | Regulation of cell shape | 31 |

| shk2 | SPAC1F5.09c | Viable | Regulation of cell shape | 76; this study |

| sid1 | SPAC9G1.09 | Lethal | Mitosis and cytokinesis | 4 |

| sid2 | SPAC24B11.11c | Lethal | Mitosis and cytokinesis | 4 |

| spk1 | SPAC31G5.09c | Viable | Meiosis | 40; this study |

| spo4 | SPBC21C3.18 | Viable | Meiosis | 39; this study |

| srb10 | SPAC23H4.17c | Viable | Negative regulator of transcription | 73; this study |

| srk1 | SPCC1322.08 | Viable | Negative regulator of meiosis | 61; this study |

| ssp1 | SPCC297.03 | Viable | Cell wall organization | 35; this study |

| ssp2 | SPCC74.03c | Viable | Unknown | This study |

| sty1 | SPAC24B11.06c | Viable | Response to stress | 60; this study |

| wee1 | SPCC18B5.03 | Viable | Cell cycle regulation | 42; this study |

| win1 | SPAC1006.09 | Viable | Response to stress | 54; this study |

| wis1 | SPBC409.07c | Viable | Response to stress | 56; this study |

| wis4 | SPAC9G1.02 | Viable | Response to stress | 58; this study |

Only one reference for each previously characterized protein kinase was selected due to space limitations. Additional references can be found in the PomDB database (www.incyte.com).

A strain bearing a kinase deletion allele was constructed, and its phenotype was assessed in this study.

DNA microarray technology has aided analyses of gene expression in parallel on a genomic scale (12). It has been proposed that the genome-wide expression profile or signature of mutant cells could serve as a phenotypic characteristic for functional studies and/or for monitoring the signaling and circuitry of MAPK pathways (32, 50). Application of microarray technology to study signaling networks could permit dissection of pathways in great detail.

While a number of studies have focused on individual protein kinases that function in the regulation of numerous biological processes, including cellular responses to various stress factors, a systematic approach has not been applied to study the functions of all the protein kinase domain-containing proteins in response to different stresses in fission yeast. In this study, we report a systematic deletion analysis of genes encoding eukaryotic protein kinase catalytic-domain-containing proteins. The fission yeast genome (74) encodes a total of 106 eukaryotic protein kinase catalytic-domain-containing genes, about half of which have previously been characterized (Table 1). Three previously uncharacterized putative protein kinases were revealed, in this study, to be essential for vegetative growth. The addition of these 3 kinases to the 14 previously characterized kinases results in the classification of 17 protein kinases as being essential, out of a total of 106 kinases in the entire fission yeast genome. The remaining 89 dispensable genes have been individually deleted, and growth phenotypes of viable mutants assessed. This has revealed that half the total number of mutants exhibit hypersensitivity to at least one of the 17 stress factors tested. A comparison of the pattern of hypersensitivity to various stresses permitted the functional grouping of all putative protein kinases and suggested four major signaling pathways or networks that appear to be mediated by known and putative protein kinases in response to a variety of stress factors. Microarray analysis in a number of mutants has revealed a significant correlation of expression signatures in mutants with their growth phenotype, enabling a useful approach for a functional classification of protein kinases.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and media.

Strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. The genotypes of parental strains are as follows: for MBY 192, ura4-D18 leu1-32 h−; for MBY 1238, ade6-210 ura4-D18 leu1-32 h90; for MBY 1239, ade6-216 ura4-D18 leu1-32 h90; and for MBY1270, ade6-210/ade6-216 ura4-D18/ura4-D18 leu1-32/leu1-32 h90/h90. Standard media such as solid or liquid YES and EMM media (36a) were utilized with or without stress factors as indicated below. For sporulation, tests were performed using solid yeast extract-peptone-dextrose (YPD) medium.

Construction of deletion mutants.

A PCR-mediated deletion approach (3) was used to construct targeted open reading frame (ORF) deletion mutants (Fig. 1). In brief, each synthesized primer (Integrated DNA Technologies, Coralville, IA) contained 80 nucleotides complementary to a particular ORF's flanking regions, followed by a barcode (20 nucleotides in length) and finally 18 nucleotides homologous to a uracil selection marker cassette. About 10 μg of PCR fragment was transformed into haploid or diploid cells using the lithium acetate method (24). Subsequently ura4+ colonies were selected on EMM plates lacking uracil. Colonies were further examined using allele-specific primer pairs (see Table S1 in the supplemental material) to ensure deletion and replacement of the target gene by the ura4+ gene.

FIG. 1.

Strategy for deletion allele construction. (A) Cell containing a wild-type target gene. (B) Pair of primers containing flanking sequences of a target gene was used to synthesize a DNA fragment by PCR, using a template carrying a selective marker gene. The barcode embedded into the long PCR primers has not been discussed in this study. (C) Haploid cell containing a deletion allele. (D) Diploid cell containing a heterozygous deletion allele. The target gene is indicated in red, and the marker gene is in green (in this study, the marker gene is ura4+). wt, wild type; ups, upstream; dns, downstream; seq, sequence.

Growth assay for hypersensitivity to stress factors.

About 5 μl of log-phase cultures in a series of 10-fold dilutions was inoculated on solid YES media containing various stress factors using a multiblot replicator (V & P Scientific Inc., San Diego, CA). The growth of each mutant strain at various dilutions (factors of 0, 1, 2, 3, …) was monitored after 3 days of incubation at 28 to 30°C or as otherwise mentioned. Mutant phenotypes based on the ability of cells to grow at the highest dilution compared to that of wild-type cells was used to characterize cultures as not sensitive, sensitive, or hypersensitive. That is, mutants exhibiting growth comparable to that of wild-type cells at the same dilution were designated as “not sensitive” or “+”; mutants exhibiting growth similar to that of wild-type cells at approximately 1 dilution factor lower than that of wild-type cells were designated as sensitive or “-”; and mutants displaying growth comparable to that of wild-type cells at 2 (or greater) dilution factors lower than that of wild-type cells were designated as hypersensitive or “--” (or “---”). Except for temperature or minimal medium parameters, each stress factor was tested two to eight times at a range of concentrations (Table S2 in the supplemental material) that killed not more than 6% of the strains being tested or left more than 6% of the mutant strains unaffected. The average of sensitivities obtained from two to eight measurements was calculated and used as a phenotypic characteristic.

DNA damage responses.

A number of mutants were assayed for sensitivity to UV-C and ionizing radiation using survival curves as previously described (69, 70). For testing sensitivities to radiomimetic drugs, exponential cultures were grown in YES medium, and 5 μl of cultures at various concentrations ranging from 106 to 103 cells/ml were spotted onto duplicate YES plates and incubated at 30°C for 3 days. Sensitivity was assayed relative to that on YES plates lacking the drug as described above.

Microarray analysis.

Acid phenol was added to the frozen cell pellets, which were then incubated at 65°C for 15 min with occasional shaking using a thermomixer (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany). The aqueous phase was recovered by spinning at 5,000 rpm for 5 min at 4°C and reextracted by phenol-chloroform (1:1). RNA was precipitated by the addition of an equal volume of isopropanol and recovered by centrifugation at 10,000 rpm for 20 min at 4°C. Fluorescently labeled cDNA was synthesized using SuperScriptII (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions with oligo(dT)20 (Invitrogen) as primers in the presence of either Cy3- or Cy5-coupled dUTP (Invitrogen). The reaction was stopped by the addition of EDTA. The cDNA was subsequently hydrolyzed with NaOH and neutralized by HCl. Fluorescence-labeled cDNA was then washed and concentrated using microcon-YM30 spin columns (Millipore, Billerica, MA).

Spotted microarray slides were prehybridized using digoxigenin hybridization buffer (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) with a raised coverslip (Erie Scientific, Portsmouth, NH) in a slide hybridization chamber (GeneMachines) for 1 h at 42°C. Slides were washed first in distilled H2O for 2 min and then in isopropanol for 2 min and spin dried. Microarray slides were hybridized using digoxigenin hybridization buffer containing Cy3- and Cy5-labeled cDNA overnight at 42°C. Hybridized slides were washed in 2× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate)-0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate for 1 min, in 1× SSC for 4 min, in 0.2× SSC for 4 min, and in 0.05× SSC for 1 min and spin dried. Microarray slides were scanned using a GenePix scanner (Axon Instruments, Union City, CA) at 635-nm and 532-nm wavelengths at a resolution of 10 μm using GenePix Pro3 or Pro4 software (Axon Instruments). Data from each GenePix result file were normalized based on a median of ratios. The ratios of each spot were collected only if the intensity of the spots in either channel was ≥2-fold greater than the background.

Phylogenic analysis of protein kinases.

Primary amino acid sequences of 106 known and putative protein kinases were obtained from databases (www.genedb.org and www.incyte.com). The catalytic-domain sequences of each protein kinase were extracted based on the Pfam definition for eukaryotic protein kinase catalytic domain (www.pfam.org). Alignment of catalytic-domain sequences and phylogenetic tree construction were carried out using Clustal W (18). The length of the dendrogram was unified for visualization.

Analyses of putative orthologs.

Mutual best hit (MBH) analysis (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Homology/ComMapDoc.html) using BLAST (version 2.2.6) was utilized for identification of Schizosaccharomyces pombe protein kinase orthologs in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and human systems. A total of 106 eukaryotic protein kinase catalytic-domain sequences in S. pombe were compared to 119 sequences in S. cerevisiae and 491 sequences in humans as documented in the KinBase database (http://198.202.68.14/kinbase). Furthermore, a relaxed mutual best hit (repeated application of mutual best hit or RMBH) protocol was applied for identification of non-MBH orthologs in S. cerevisiae and human. In each iteration, a set of orthologs were identified using MBH analysis and removed from both genomes. In the next iteration, the updated genomes were submitted to MBH analysis for another set of orthologs and the procedure continued till either of the genomes was empty or no more mutual best hits were found. The minimum BLAST score threshold of 206 was set on the orthologs obtained from the second iteration of RMBH analysis. This threshold value was obtained as the score that covered 80% of all the orthologs obtained using MBH analysis only.

RESULTS

Evolutionary analysis of fission yeast protein kinases.

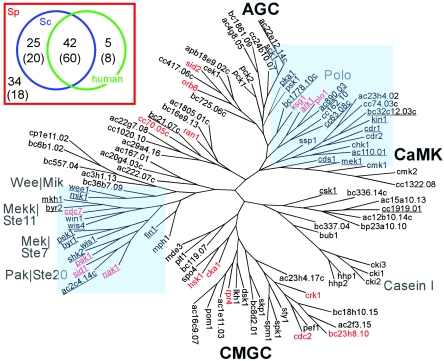

A total of 106 genes encoding eukaryotic protein kinase catalytic-domain-containing proteins were found in the entire S. pombe genome based on the GeneDB (www.genedb.org) and the pombeDB (www.incyte.com/proteome) databases, of which approximately 45 were uncharacterized putative protein kinase (ppk) genes (Table 1). During the course of this project, some putative protein kinases were reported and have therefore been renamed accordingly. Phylogenic analysis of the protein kinases based on the catalytic-domain sequences (16, 22) revealed that no known or putative protein kinases in fission yeast belong to the PTK group, which consists of conventional protein tyrosine kinases (Fig. 2). Members of the PTK group are therefore likely to be specific to multicellular organisms, where they function in cell-cell communication (51). Although no PTK protein kinases could be detected in the S. pombe genome, 31 protein kinases possess a tyrosine kinase signature (www.ebi.ac.uk/interpro) suggesting a potential tyrosine kinase activity as shown in Fig. 2. Two previously well-characterized protein kinases, Rad3p and Tel1p, have been shown to possess a lipid-kinase domain instead of a protein-kinase domain, and therefore they are not discussed in this study.

FIG. 2.

Unrooted phylogenic tree of the 106 protein kinases in S. pombe. Seventeen essential protein kinases are marked in red, and 31 kinases containing tyrosine phosphorylation signatures are underlined. Two regions of the phylogenic tree shaded blue indicate that the region is enriched with tyrosine kinase signatures. AGC, CaMK, and CMGC indicate protein kinase groups, and Polo, Casein I, Wee/Mik, Mekk/Ste11, Mek/Ste7, and Pak/Ste20 indicate protein kinase families that do not belong to the AGC, CaMK, and CMGC groups. The inset shows a schematic representation of protein kinase orthologs in S. pombe (Sp), S. cerevisiae (Sc), and human. One hundred six eukaryotic protein kinase catalytic-domain-containing proteins were selected in S. pombe, 119 in S. cerevisiae, and 491 in human. Analysis of orthologs showed that of 106 S. pombe protein kinases, 67 (25 plus 42) have orthologs in S. cerevisiae and 47 (42 plus 5) in human. Among these, 42 appeared to have orthologs in both S. cerevisiae and human. Numbers in parentheses indicate the numbers of nearest homologs.

Of the 106 known and putative protein kinases, 67 were found to have orthologs in a distant relative of S. cerevisiae and 47 in human, which increased to 80 in S. cerevisiae and 68 in human upon inclusion of the nearest homologs based on 106 protein kinase catalytic domain-containing proteins in S. pombe, 119 in S. cerevisiae, and 419 in human (Fig. 2, inset). According to MBH analysis, only 34 (or 18 based on RMBH analysis) out of 106 known and putative protein kinases were revealed to be unique to S. pombe. Forty-four percent (or 64%) of kinases in the entire genome appeared to have orthologs (or nearest homologs) in humans, indicating that studies on biological functions of fission yeast protein kinases would facilitate our understanding of protein kinase-mediated signaling pathways in human.

Putative protein kinases essential for viability.

We investigated the functions of all putative protein kinases found in the S. pombe genome through a systematic deletion analysis. At the time we started this study, 14 protein kinases were known to be essential for viability. We therefore selected the remaining 92 genes encoding known and putative protein kinases for the construction of deletion mutants (Table 1).

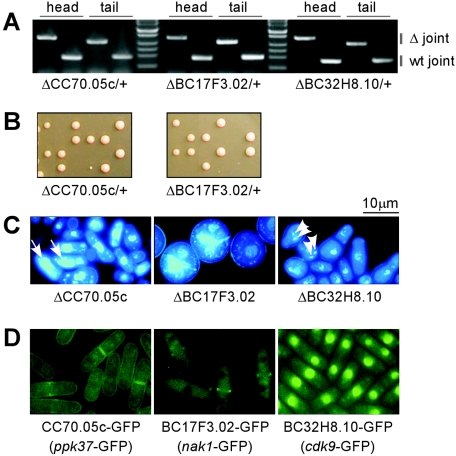

Individual deletion of three genes out of 92, namely, SPCC70.05c, SPBC17F3.02, and SPBC32H8.10, was not accomplished when haploid strains were transformed, suggesting that these gene products might be essential for cell viability. To further examine the essentiality of these putative protein kinases, we constructed deletion alleles in diploid cells. Verification of diploid mutants with a heterozygous deletion allele was performed via a PCR-based assay using two primer pairs, which were specific either for the wild-type allele or the deletion allele (Fig. 3A). The diploid mutant cells were subsequently grown on YPD plates for sporulation to segregate heterozygous alleles. Tetrad dissection of spores from asci generated from the heterozygous diploid mutants displayed a 2:2 segregation pattern, indicating that spores bearing a deletion allele were unable to form colonies (Fig. 3B). This was subsequently confirmed by replication of tetrad colonies onto a uracil drop-out plate. Spores carrying a deletion allele failed to form colonies, confirming that these three putative protein kinases were essential for viability.

FIG. 3.

Essential putative protein kinases. (A) Heterozygous deletion alleles in diploid mutant cells were verified by PCR using allele-specific primers as explained in the legend to Fig. 1. Wild-type (wt) alleles were confirmed by PCR using the target-specific primer pairs pA-pB for the 5′-end (head) joint and pC/pD for the 3′-end (tail) joint; deletion alleles were confirmed by PCR using primer pairs of target-specific pA-marker-specific pB-ura (head) and marker-specific pC-ura-target-specifc pD (tail). (B) Tetrad analysis confirmed that the putative protein kinases were essential for vegetative growth. (C) Free-spore assay of the mutants. DNA was stained using the fluorescent dye DAPI. Arrows and arrowheads indicate horse tail-like and condensed chromosomes, respectively. (D) Subcellular localization of GFP-tagged kinases in wild-type haploid cells. See the text for details.

Free-spore germination analysis of the three mutants revealed the following phenotypes. SPCC70.05c (ppk37) mutant cells showed an abnormal nuclear DNA morphology in that the DAPI (4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole)-stained nuclear material was more diffuse and spread over a larger region of the cell (Fig. 3C), than that of a wild-type control. In some instances, these DNA structures appeared to resemble meiotic horse tail chromosomes. However, more work with conditional alleles will be required to establish the basis of this nuclear morphology phenotype. SPBC17F3.02 (allelic with nak1) mutants have a round cell morphology, indicating a defect in polarity establishment and/or maintenance; and SPBC32H8.10 mutants exhibit small-dot-like DNA staining, suggesting a compaction of chromosomal DNA in interphase cells (Fig. 3C).

We then further investigated the subcellular localization of these three essential putative protein kinases by tagging them with a green fluorescent protein (GFP) in wild-type cells. Haploid cells bearing a putative protein kinase with GFP fused at its C terminus as a sole copy in the genome were viable, indicating that the tagged proteins were functional. Fluorescence microscopy analysis revealed distinct subcellular localization of these protein kinases: SPCC70.05c-GFP was predominantly distributed at cortical membranes, SPBC17F3.02-GFP was localized in the cytoplasm and at the division septum, and SPBC32H8.10-GFP showed a nuclear localization (Fig. 3D). During the process of this study, two S. pombe protein kinases, SPBC17F3.02/nak1 and SPBC32H8.10/cdk9, were reported by Huang et al. (20) and Pei and Shuman (45). Both kinases have orthologs in S. cerevisiae: YHR102W/KIC1 and YPR161C/SGV1.

Hypersensitivity of deletion mutant strains.

Besides the three putative protein kinases that were found to be essential for viability, SPAC29A4.16 (ppk10) was initially unable to form colonies when deleted in haploid cells. Tetrad dissection analysis of a diploid knockout strain showed that all spores from tetrads, containing either a wild-type allele or a deletion allele, were viable and formed colonies on a YES plate. Examination of colonies replicated onto EMM plates lacking uracil revealed that ura4+ colonies were very sensitive to minimal medium, which explained why the haploid deletion mutants failed to grow on the selective medium, suggesting a role for ppk10 in some aspects of cellular metabolism.

Next we assessed the growth phenotype of all viable deletion mutants. At least two independent isolates were examined to ascertain that there was no random mutation in the background which could potentially alter the mutant phenotype. We also constructed deletion alleles of all the previously characterized dispensable protein kinases as a control for assessment of possible phenotypic alterations. The growth assay performed in this study (Table 2) indicated that the phenotypes of deletion mutants lacking a known protein kinase were identical to what was previously reported. Hence, we are confident that our putative protein kinase mutant strains constructed in haploid cells are unlikely to harbor any random mutations or suppressors.

TABLE 2.

Summary of growth phenotypes of the deletion mutants lacking one of the nonessential known and putative protein kinases indicated

| Gene symbol | Systematic name | Growth with indicated stressa

|

||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 19°C | 36°C | MM | TBZ | MBC | LatA | BFA | cHex | H2O2 | HU | EMS | Bleo | SDS | EGTA | KCl | Sorb | Calc | ||

| bub1 | SPCC1322.12c | ND | + | ND | --- | --- | + | ND | ND | ND | - | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| byr1 | SPAC1D4.13 | + | + | - | - | - | + | + | - | + | + | + | - | + | + | + | + | + |

| byr2 | SPBC1D7.05 | + | + | + | - | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | - | - | + | + | + | - |

| cdr1 | SPAC644.06c | + | + | + | - | - | - | - | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| cdr2 | SPAC57A10.02 | + | + | + | - | - | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | - | + | + | + |

| cds1 | SPCC18B5.11c | + | + | - | - | + | - | + | - | - | --- | + | + | - | + | - | + | + |

| cek1 | SPCC1450.11c | - | + | - | - | - | - | + | + | + | + | + | + | -- | + | - | + | - |

| chk1 | SPCC1259.13 | + | + | + | - | - | + | - | + | + | --- | - | - | + | + | + | + | + |

| cki1 | SPBC1347.06c | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| cki2 | SPBP35G2.05c | + | + | + | - | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| cki3 | SPAC1805.05 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | - | + | + | + | + |

| cmk1 | SPACUNK12.02c | + | - | - | - | + | + | + | - | + | - | + | - | + | + | + | + | + |

| cmk2 | SPAC23A1.06c | + | + | - | + | + | + | + | - | + | - | + | - | - | + | + | + | + |

| csk1 | SPAC1D4.06c | --- | + | --- | -- | -- | - | -- | - | - | - | + | -- | -- | + | - | - | - |

| dsk1 | SPBC530.14c | + | + | - | - | - | + | + | - | + | - | - | - | + | - | + | + | + |

| fin1 | SPAC19E9.02 | + | + | + | --- | --- | + | + | + | + | - | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| gad8 | SPCC24B10.07 | - | + | + | --- | - | - | + | + | - | + | + | -- | -- | + | -- | + | + |

| gsk3 | SPAC1687.15 | - | + | + | - | - | - | + | + | + | + | + | + | - | + | - | + | + |

| gsk31 | SPBC8D2.01 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | - | + | + | + | + | + | - | + | + | + |

| hhp1 | SPBC3H7.15 | -- | - | - | - | - | + | - | + | - | --- | --- | -- | -- | + | - | - | + |

| hhp2 | SPAC23C4.12 | + | + | + | - | + | + | + | + | + | -- | - | + | + | + | - | + | + |

| hri1 | SPAC20G4.03c | + | + | + | - | - | - | - | + | + | + | - | - | - | + | + | + | + |

| hri2 | SPAC222.07c | + | + | + | - | + | + | + | + | - | + | - | - | - | + | - | + | - |

| kin1 | SPBC4F6.06 | + | - | - | --- | -- | + | - | --- | + | - | - | --- | -- | --- | -- | + | + |

| lkh1 | SPAC1D4.11c | - | - | - | - | - | - | + | - | - | - | + | - | -- | + | - | - | - |

| lsk1 | SPAC2F3.15 | - | + | + | -- | - | + | + | + | - | + | - | - | + | + | + | + | + |

| mde3 | SPBC8D2.19 | + | + | + | - | + | - | + | + | + | - | + | + | - | + | - | - | - |

| mek1 | SPAC14C4.03 | - | + | + | - | - | + | - | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| mik1 | SPBC660.14 | - | + | + | - | - | + | + | + | + | --- | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| mkh1 | SPAC1F3.02c | + | - | - | -- | - | + | + | + | + | - | - | + | + | - | - | + | + |

| mph1 | SPBC106.01 | + | + | -- | --- | --- | + | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | + | + |

| oca2 | SPCC1020.10 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| pck1 | SPAC17G8.14c | -- | - | + | - | + | - | + | + | + | + | + | + | - | + | - | + | + |

| pck2 | SPBC12D12.04c | --- | -- | + | - | - | + | + | + | - | - | + | + | - | + | - | - | + |

| pef1 | SPCC16C4.11 | - | - | --- | - | + | - | - | + | -- | - | - | -- | - | - | - | + | - |

| pek1 | SPBC543.07 | + | + | - | -- | - | - | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| pit1 | SPAC3C7.06c | + | + | - | - | - | + | + | + | + | + | - | + | + | + | - | + | + |

| pka1 | SPBC106.10 | + | + | + | -- | -- | --- | + | - | - | -- | + | -- | - | + | --- | - | + |

| pmk1 | SPBC119.08 | - | - | - | -- | - | -- | - | + | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | + |

| pom1 | SPAC2F7.03c | -- | + | + | - | - | -- | - | - | + | - | - | - | -- | - | - | - | - |

| ppk1 | SPAC110.01 | + | + | + | - | + | + | + | + | + | - | + | + | - | + | + | + | + |

| ppk2 | SPAC12B10.14c | ND | + | - | - | + | + | + | + | + | + | - | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| ppk3 | SPAC15A10.13 | - | + | + | -- | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | + | - | + | - |

| ppk4 | SPAC167.01 | + | - | -- | - | - | - | - | + | + | - | - | - | - | + | - | - | - |

| ppk5 | SPAC16C9.07 | + | + | + | - | + | + | - | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| ppk6 | SPAC1805.01c | + | + | - | + | + | + | + | - | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| ppk7 | SPAC22E12.14c | + | + | + | - | - | + | - | - | + | + | - | + | + | + | - | + | + |

| ppk8 | SPAC22G7.08 | + | + | + | - | + | + | + | - | + | - | - | - | + | - | + | + | + |

| ppk9 | SPAC23H4.02 | + | + | + | - | - | - | + | + | + | - | + | - | + | + | + | + | + |

| ppk10 | SPAC29A4.16 | - | + | --- | --- | - | -- | - | -- | - | --- | - | --- | -- | + | + | - | - |

| ppk11 | SPAC2C4.14c | + | - | + | - | - | + | + | + | - | + | - | - | + | + | + | + | + |

| ppk13 | SPAC3H1.13 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| ppk14 | SPAC4G8.05 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | - | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| ppk15 | SPAC823.03 | - | + | + | - | + | - | - | + | - | - | + | -- | -- | + | + | + | - |

| ppk16 | SPAC890.03 | + | + | + | - | + | + | + | + | + | - | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| ppk18 | SPAPB18E9.02c | -- | + | -- | -- | + | -- | + | + | + | + | + | - | - | + | - | + | - |

| ppk19 | SPBC119.07 | -- | --- | - | --- | - | + | + | -- | - | + | + | --- | + | --- | -- | + | + |

| ppk20 | SPBC16E9.13 | - | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | - | + | + | + |

| ppk21 | SPBC1778.10c | + | + | + | - | + | + | - | + | + | + | + | - | + | + | + | + | + |

| ppk22 | SPBC1861.09 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | - | + | - | + | + | - | - |

| ppk23 | SPBC18H10.15 | -- | + | + | - | + | - | + | + | - | - | + | - | - | + | - | - | - |

| ppk24 | SPBC21.07c | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | - | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| ppk25 | SPBC32C12.03c | - | + | + | - | - | - | - | + | + | - | - | + | + | + | - | + | + |

| ppk26 | SPBC336.14c | + | - | -- | -- | - | + | + | + | + | + | - | + | - | - | + | - | + |

| ppk27 | SPBC337.04 | --- | + | + | - | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | - | + | + | + | + |

| ppk28 | SPBC36B7.09 | + | + | + | - | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | - | + | + |

| ppk29 | SPBC557.04 | - | + | + | - | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | - | + | + | - | - |

| ppk30 | SPBC6B1.02 | - | + | ND | - | - | - | + | + | - | + | + | - | - | - | + | - | + |

| ppk31 | SPBC725.06c | + | + | + | - | - | + | + | + | + | + | -- | + | + | - | + | + | + |

| ppk32 | SPBP23A10.10 | - | + | + | -- | - | + | + | + | + | + | - | + | - | + | - | - | + |

| ppk33 | SPCC162.10 | + | + | - | - | - | - | + | - | + | - | - | + | + | + | + | + | - |

| ppk34 | SPCC1919.01 | - | + | - | - | + | + | - | + | + | + | + | -- | - | + | + | + | - |

| ppk35 | SPCC417.06c | + | + | + | + | + | - | + | + | + | + | - | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| ppk36 | SPCC63.08c | + | + | + | - | + | - | + | + | + | - | - | + | + | + | + | + | - |

| ppk38 | SPCP1E11.02 | + | - | + | - | + | + | - | + | + | + | - | - | - | - | + | + | + |

| psk1 | SPCC4G3.08 | + | + | + | - | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | - | + | + | + |

| sck1 | SPAC1B9.02c | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| shk2 | SPAC1F5.09c | + | + | -- | - | + | - | + | + | + | - | + | - | + | + | + | + | - |

| spk1 | SPAC31G5.09c | - | + | - | - | - | + | + | - | + | - | - | - | + | + | - | + | + |

| spo4 | SPBC21C3.18 | + | + | - | - | - | -- | - | + | + | - | + | - | - | + | - | - | -- |

| srb10 | SPAC23H4.17c | + | + | + | - | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | - | - | + | + | + |

| srk1 | SPCC1322.08 | + | + | - | - | - | - | - | + | + | - | + | - | + | - | - | + | - |

| ssp1 | SPCC297.03 | + | - | - | - | - | + | + | + | + | + | - | + | + | + | - | - | + |

| ssp2 | SPCC74.03c | - | - | + | - | + | - | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| sty1 | SPAC24B11.06c | + | --- | -- | -- | - | + | - | - | --- | - | - | -- | - | - | --- | -- | + |

| wee1 | SPCC18B5.03 | --- | -- | - | --- | -- | -- | - | -- | - | -- | + | --- | -- | + | - | - | - |

| win1 | SPAC1006.09 | + | --- | + | -- | - | + | + | + | - | + | - | + | - | + | -- | - | - |

| wis1 | SPBC409.07c | --- | --- | - | - | - | -- | - | - | --- | + | + | -- | --- | + | --- | -- | - |

| wis4 | SPAC9G1.02 | + | −− | + | - | + | - | - | - | -- | - | - | - | - | - | -- | + | - |

Abbreviations for stress factors: MM, minimum medium; TBZ, thiabendazole; MBC, methyl 2-benzimidazole carbamate; LatA, latrunculin A; BFA, brefeldin A; cHex, cyclohexmide; HU, hydroxyurea; EMS, ethyl methanesulfonate; Bleo, bleomycin; SDS, sodium dodecyl sulfate; Sorb, sorbitol; Calc, calcofluor. Description of phenotypes: ND, no data; +, wild-type growth; -, growth at 1 dilution factor less than that of wild-type cells; --, 2 dilution factors less; ---, 3 (or >3) dilution factors less than that of the wild-type cells.

The vast majority of nonessential kinase deletion mutants resembled wild-type cells in morphology, although a subset of previously characterized mutants (such as pom1, pck1, and pck2) exhibited abnormal morphology. In addition, several previously characterized mutants (wee1, cdr1, cdr2, wis1, spk1, and sty1) exhibited altered size at division. One kinase mutant (pdk1Δ; ppk21) was moderately defective in cytokinesis and will be published separately (A.B., J.L., and M.K.B., unpublished data).

The growth of all viable protein kinase deletion mutants was investigated under various stress conditions. Their temperature sensitivity was tested on YES plates incubated at 19°C (low temperature) and 36°C (high temperature). In order to determine the sensitivity of deletion mutant strains to various stress factors, we supplemented YES medium with common stress factors, such as salt (KCl), an osmolyte (sorbitol), an oxidant (hydrogen peroxide), agents that inhibit DNA replication (hydroxyurea [HU]) or damage DNA (ethyl methanesulfonate [EMS]), cytoskeleton poisons (methyl 2-benzimidazole carbamate [MBC], thiobendazole [TBZ], and latrunculin A [LatA]), chemicals that disrupt cell wall/membrane structures (calcofluor, sodium dodecyl sulfate), and agents that block the secretory pathway (brefeldin A), protein biosynthesis (cycloheximide), and chelate Ca2+ (EGTA).

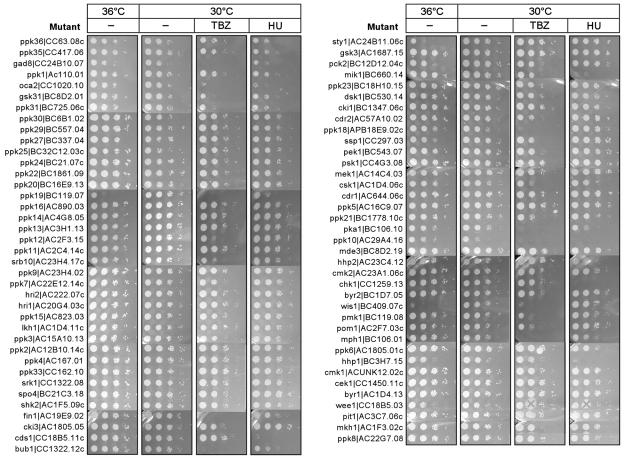

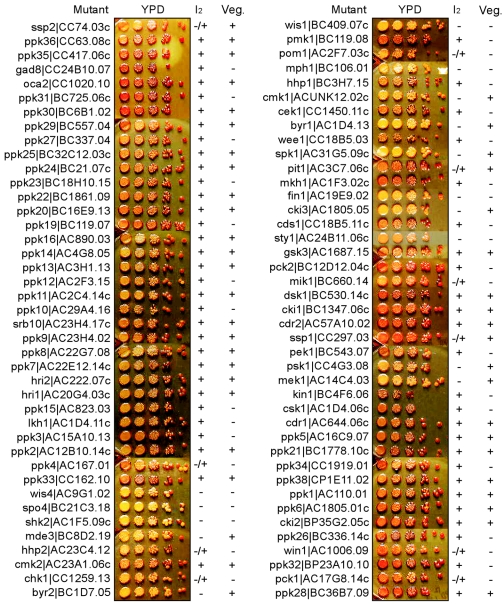

For each stress factor, ranges of dosages were applied. For further analysis we chose only those concentrations at which no more than 6% of mutants displayed wild-type growth dynamics and at least 6% of mutants were able to grow. The ability of kinase deletion strains to grow at 36°C and on plates supplemented with TBZ or HU as an example is shown in Fig. 4, while Table 2 contains a summary of all data obtained from the sensitivity assays.

FIG. 4.

Phenotypic assessment of nonessential protein kinase mutants. Approximately 5 μl of 10-fold serial dilutions of the 88 viable haploid h− mutant cells (sck1− mutant was not available) were spotted and grown under 17 different stress conditions with various dosages. Examples of cell growth under stress conditions such as high temperature (36°C), a microtubule poison (TBZ), and an agent that blocks DNA replication (HU) are shown. A mutant was described as hypersensitive to a stress condition when its growth was similar to that of wild-type cells at 2 (or >2) dilution factors lower. Mutant growth phenotypes under various conditions are individually summarized in Table 2.

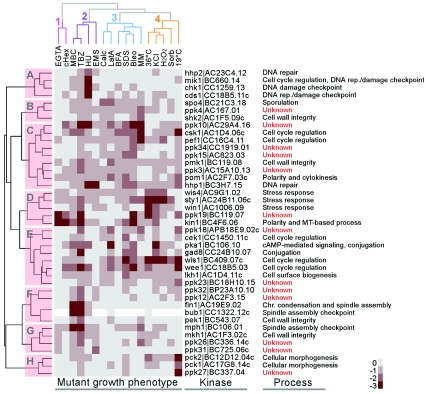

Functional grouping of putative protein kinases.

To classify mutants based on similar growth defects under various stress conditions, we selected 41 mutants that exhibited hypersensitivity to at least one of the 17 different stress conditions tested and investigated the growth patterns of these strains under various stress conditions based on semiquantitative values of the mutant growth (Table 2). Two-dimensional cluster analysis using the Pearson correlation (14) with complete linkage groups based on a minimal similarity of 50% of the growth pattern under various stress conditions resulted in eight groups (Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

Phenotypic clustering of hypersensitive mutants. Pearson correlation clustering of the growth pattern of the protein kinase mutants was performed to analyze 41 known and putative protein kinase mutants that exhibited hypersensitivity to at least one of the 17 stress conditions tested (see the text). Upon comparison of growth phenotypes under various conditions, 41 mutants were divided into eight groups with a minimal similarity of 50%. The 17 conditions used in the phenotypic assessment were separated into four clusters. rep., repair; MT, microtubule; Calc, calcofluor; BFA, brefeldin A; SDS, sodium dodecyl sulfate; Bleo, bleomycin; MM, minimum medium; Sorb, sorbitol.

Mutants in group A showed hypersensitivity to hydroxyurea, a drug that blocks DNA replication, and to the mutagens methyl methanesulfonate and 4-nitroquinoline-N-oxide (4NQ) (Table 3). This is consistent with previous reports indicating that cds1−, chk1−, hhp2−, and mik1− mutants are defective in DNA repair and/or DNA damage/replication checkpoint control (13, 28, 38, 71).

TABLE 3.

Hypersensitivities of known and putative protein kinase mutants to DNA damage agents

| Gene symbol | Systematic name | Growtha on:

|

Cell cycle arrest phenotypeb on:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MMS | 4NQ | MMS | 4NQ | ||

| bub1 | SPCC1322.12c | -- | - | EI | EV |

| cds1 | SPCC18B5.11c | --- | --- | EI | EI |

| chk1 | SPCC1259.13 | --- | --- | EI | EI |

| gad8 | SPCC24B10.07 | --- | --- | EI | EI |

| hhp1 | SPBC3H7.15 | --- | --- | EI | EI |

| kin1 | SPBC4F6.06 | -- | - | EI | EV |

| mik1 | SPBC660.14 | --- | --- | EI | EI |

| oca2 | SPCC1020.10 | --- | - | EI | EV |

| ppk19 | SPBC119.07 | --- | -- | EI | EV |

| ppk26 | SPBC336.14c | -- | + | EI | EV |

| wis1 | SPBC409.07c | --- | --- | EI | EI |

| wee1 | SPCC18B5.03 | --- | --- | EI | EI |

+ and - stand for growth as defined in Table 2, footnote a.

Cell cycle arrest phenotypes were assessed after several generations on the stress indicated. EI and EV stand for elongated inviable and viable cells, respectively.

Most mutants in groups B and C exhibited multiple sensitivities to a number of stress factors, such as the microtubule poison TBZ, the actin-depolymerizing agent LatA, the replication inhibitor HU, the detergent SDS, and the antibiotic bleomycin. These protein kinases and putative protein kinases are likely to be involved in multiple biological processes, including cell cycle regulation, cell wall biogenesis, and polarized growth (see Table 1 for references).

Group D contained mutants such as the wis4−, win1−, and sty1− mutants, which exhibited hypersensitivity to a number of common stress factors, such as high temperature, high salt concentration, and oxidative stress, consistent with previous reports (54, 58, 60). Besides the wis4−, win1− and sty1− mutants, two other kinases, the kin1− mutant and the previously uncharacterized ppk19− (BC119.07) mutant, could be clustered into the same group. Interestingly both the kin1− and ppk19− mutants in addition to the above-mentioned stress factors displayed hypersensitivity to a number of other conditions, i.e., EGTA and cycloheximide.

Mutants in group E showed diverse phenotypes and likely function in cell cycle regulation and cell growth, similar to those in groups B and C, and in response to common stresses, such as temperature and the presence of salt, an oxidant, and an osmolyte.

Mutants in group F exhibited hypersensitivity limited to microtubule poisons such as MBC and TBZ, implicating their involvement in noncytoplasmic microtubule-associated processes. This group includes molecules such as Fin1 and Bub1, which are known to regulate mitotic spindle assembly or spindle checkpoint control (7, 27). Many mutants in groups B, C, and E showed hypersensitivity to both microtubule poisons and to the actin inhibitor LatA. It is conceivable that mutations affecting the function of protein kinases involved in cytoplasmic microtubule-mediated cellular growth would result in hypersensitivity to both microtubule poisons and polarized growth inhibitors.

Group G kinases appear to be involved in the assembly of the mitotic spindle, and in this respect they are similar to the members of group F described above. However, they have an additional role in maintaining cell wall integrity.

The last group, group H, is comprised of three members, individual deletions in which resulted in very poor growth at 19°C. Pck1 and Pck2 are known to be involved in cellular morphogenesis. The comparison of growth phenotypes thus allowed us to assign functions to putative protein kinases based on established information of previously characterized protein kinases classified in the same group (see references in Table 1).

We applied each of the stresses at an intermediate dosage range that resulted in comparable effects on mutant cell growth; that is, the dose was neither too strong to inhibit the growth of a majority of mutants (e.g., >6%) nor too weak to display any effect on many mutants (>6%). Given the fact that all available protein kinase mutants were tested under identical conditions, the different effects of stress factors could thus be compared. Following two-dimensional cluster analysis, 17 stress factors were separated into four categories (Fig. 5). Category 1 had only two factors, EGTA (Ca2+ chelate) and cycloheximide (protein biosynthesis inhibitor), and only two mutants, the ppk19− and kin1− mutants, exhibited hypersensitivity to these factors. Category 2 consisted of the microtubule poisons TBZ and MBC, and agents affecting DNA replication and integrity viz., HU and EMS, respectively. In this study, we found that EMS was less potent than methyl methanesulfonate (MMS); therefore, we tested a number of mutants using the stress factors MMS and 4NQ (Table 3). Those deletion mutants that showed hypersensitivity to HU exhibited hypersensitivity to both MMS and 4NQ. It is not clear why microtubule poisons and DNA damage (or replication block) agents grouped together. It may reflect a group of stress factors that could potentially destabilize genome integrity since both chromosomal DNA and mitotic spindles are nuclear and required for this process. Category 3 contains a number of factors that affect general cellular growth: calcofluor disrupts cell wall structures, latrunculin A prevents polymerization of the actin cytoskeleton, and brefeldin A interferes with secretory pathways. Category 4 contains those stress factors that are commonly present in the environment, such as high or low temperatures, high salt, a high osmolyte concentration, and the oxidant H2O2. Each category may reflect a major signaling pathway that is involved in the response to the stress factors within the category. Consistent with this, it is likely that Wis4-Wis1-Sty1 is the major signaling pathway in response to a number of common stress factors, such as temperature and the presence of salt, an osmolyte, and an oxidant (9).

Conjugation, meiosis, and sporulation.

Fission yeast cells undergo meiosis upon nutritional starvation, leading to the formation of ascospores (75). A number of regulators, including protein kinases that are required for conjugation (e.g., Byr2, Byr1, and Spk1), meiosis (e.g., Mde3 and Mek1), and sporulation (e.g., Spo4 and Pit1) have been previously characterized (see references in Table 1 and www.genedb.org/ and www.incyte.com/proteome/). Mutations in some of them (e.g., the byr2, byr1, med3, mek1, and pit1 genes) were found to have no obvious vegetative growth phenotype under various stress conditions tested (Fig. 6) (see references in Table 1) but failed to conjugate or undergo meiosis or sporulation (Fig. 6). In order to identify protein kinases which are involved in any of these three processes, we constructed 84 individual kinase deletion alleles in a haploid homothallic (h90) strain that could undergo mating and sporulation upon nitrogen starvation (75). Aliquots from a set of serially diluted cultures were spotted onto YPD plates for induction of sporulation. Wild-type cells formed spores after 3 to 4 days at 24°C as indicated by a dark-brown staining of spores upon a brief exposure to iodine vapor (data not shown) due to amyloid-rich spore walls (8). Of 84 protein kinase and putative protein kinase mutants tested, 15 showed major defects in spore formation based on iodine vapor staining and 10 showed partial defects (Fig. 6). Thus, about 30% of protein kinases found in the entire fission yeast genome were required for conjugation, meiosis, or sporulation.

FIG. 6.

Sporulation assay. Iodine staining of mutants under conditions promoting sporulation was performed. About 5 μl of 10-fold serial dilutions of 84 haploid h90 mutant cells (5 h90 mutants were not available) were tested for conjugation, meiosis, or sporulation. Mutants defective in conjugation, meiosis, or sporulation display negative staining with iodine vapor (I2) and are indicated with “-.” Partially negative stainings are marked with “-/+.” Mutant cells which displayed the vegetative growth phenotype (Veg.) under at least one of the 17 conditions tested are indicated with “-” (see Fig. 5). A white crossed spot was a bacterial contaminant.

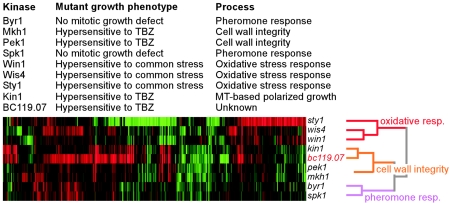

Mapping signaling pathways using genome-wide expression signatures of protein kinase mutants.

In this study, we found that 15 known and putative protein kinase mutants were hypersensitive to at least one of the stress factors tested and were also defective in conjugation, meiosis, or sporulation, while 12 mutants displayed only meiotic defects (Fig. 6). We therefore sought to ascertain whether protein kinase-mediated signaling pathways that play multiple roles in processes such as vegetative growth, conjugation, meiosis, and sporulation exist. It has been demonstrated that expression signatures are uniquely characteristic of various mutants (21). Using an oligonucleotide-based DNA microarray covering all predicted genes, we obtained genome-wide expression profiles or expression signatures from a number of protein kinase mutants (see Table S3 in the supplemental material) whose phenotypes upon deletion were well defined except for one putative kinase (ppk19). Pearson correlation analysis with complete linkage (14) demonstrated that single expression signatures of various protein kinase mutants could be clearly correlated with their growth phenotype during both vegetative growth and sporulation (Fig. 7).

FIG. 7.

Expression signatures identify mutant phenotypes. Pearson correlation clustering of the expression signatures of the protein kinase mutants was performed. An expression profile of each mutant under optimal growth conditions was attained using oligonucleotide-based whole-genome DNA microarrays with a wild-type strain (ura4+) as a common reference. Eight hundred forty-five genes whose expression levels changed 1.6-fold or greater in at least one of the nine mutant profiles were selected for cluster analysis. Eight protein kinases are known to be involved in oxidative-stress responses (in red), cell wall integrity or polarized growth (in orange), and pheromone responses (in purple). A putative protein kinase, SPBC119.07, which showed growth defects in drug sensitivity assays similar to those of the kin1 mutant (Fig. 5) displayed an expression signature similar to that of the kin1 mutant. MT, microtubule.

As shown in Fig. 7, the expression signatures of mutant sty1−, wis4−, and win1− strains (mutants that are defective in the oxidative-stress response) clustered together, consistent with results obtained from phenotypic assessment (Fig. 5). Intriguingly, the expression signatures of the protein kinase byr1− and spk1− mutants (defective in conjugation) clustered together but could be distinguished from cell wall integrity mkh1− and pek1− mutants and oxidation stress-sensitive sty1−, wis4−, and win1− mutants. A simple expression signature could therefore identify the mutant phenotype of a strain. Furthermore, the cluster of byr1− and spk1− signatures was closer to that of mkh1− and pek1− signatures (Fig. 7) than to the location of the sty1−, wis1−, and win1− cluster. This was consistent with a common function for the byr1-spk1 and the mkh1-pek1 clusters in cellular morphogenesis. In addition, mutant kin1 was known to be involved in microtubule-mediated polarized growth (29). In a phenotypic assessment, the kin1− mutant was grouped with the sty1−, wis4−, and win1− mutants (Fig. 5). However, based on the expression signature, the kin1− mutant was grouped with the SPBC119.07− mutant and closely related to the pek1 and mkh1 mutants (Fig. 7). SPBC119.07 is likely to have a function similar to that of kin1 since both phenotypic assay and expression profiling indicated that they are closely related. The expression signature of a mutant is based on transcriptional changes at a whole-genome level (21), whereas a phenotypic assay includes a limited set of selected conditions. The expression signature could therefore be extrapolated to predict the mutant phenotype (i.e., the cellular response to different stress factors) and finally could be utilized for the functional classification of all known and putative protein kinases.

DISCUSSION

Determining the effect of gene deletions is a fundamental approach to understanding gene function. We have carried out a systematic deletion analysis for all the putative protein kinases and known dispensable protein kinases in the fission yeast S. pombe. We identified three genes whose function is essential for cell viability (Fig. 3 and Table 1). Thus, the total number of fission yeast protein kinases indispensable for vegetative growth is 17 (16%). A phenotypic assessment of viable deletion mutants revealed that the function of 46% of these kinases is required for growth under the stress conditions tested in this study.

Various stress factors could disrupt different cellular metabolic pathways and/or cellular components. Defective growth observed under a particular stress condition implies that the deletion kinase is potentially involved in mediating signals during the cellular response given to that stress factor. In addition, dosage ranges of stress factors exhibit different degrees of disruption to cellular growth. By assaying a large number of deletion mutants with a range of dosages, we have shown that the stress factors may be divided into four groups. This raises the possibility of the existence of four major signaling pathways or networks organized in fission yeast in response to the stress factors tested. This is consistent with the proposition by Chen et al. (9) that wis4-wis1-sty1 is the major signaling pathway mediating signals in response to a number of stress factors in category 4.

Of 89 dispensable protein kinases, 15 are found to function both in vegetative growth under stress conditions and in sporulation, and 12 appear to function specifically in sporulation. Thirty-six out of 89 dispensable kinase mutants displayed no obvious phenotype in both the vegetative-growth assay and the sporulation assay, suggesting redundant functions for these protein kinases. Alternatively, they may be required for growth under conditions not examined in this study.

We have shown that single genome-wide expression signatures of individual mutants can be utilized to classify the protein kinases involved in oxidative stress and pheromone responses. Furthermore, it can effectively differentiate kinases that are involved in morphogenesis from those that do not play roles in this process. It is likely that the expression signature will reveal information about those kinases whose deletion mutants do not exhibit any detectable phenotype. The determination of expression signatures is potentially a very important approach for functional analysis of various protein kinase-mediated signaling pathways.

Eukaryotic protein kinase catalytic-domain-containing proteins are conserved from yeast to human. We have extracted 106 known and putative protein kinases from the entire S. pombe genome. Comparative analyses using mutual best-hit analysis and nearest-homolog analysis demonstrated that 44% and 64% of S. pombe protein kinases could be paired with their orthologues or nearest homologues in human, respectively (Fig. 2). Therefore, the study of protein kinase functions in fission yeast could promote our understanding of the biological functions of protein kinase-mediated signaling pathways in mammalian systems. We hope that our mutants and the results presented in this study will be useful to our colleagues in further elucidating protein kinase-mediated signaling pathways or networks in yeast as well as in higher eukaryotic systems. Our microarray data sets for expression signature of protein kinase mutants tested are available at http://giscompute.gis.a-star.edu.sg/∼gisljh/kinome.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Y. Kuang for her assistance in phylogenic analysis and J. Li for maintenance of database. We appreciate V. M. D'souza, P. Robson, and T. Lufkin for critical reading and helpful discussion of the manuscript.

N.D.E. is a Doherty Fellow of the NHMRC. M.O. is a scholar of the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society. This work was supported by a NHMRC grant (114229) to M.O. The kinase gene deletions were constructed in the laboratory of M.K.B., with funds from the Temasek Life Sciences Laboratory, and the S. pombe microarray was generated in the laboratory of J.L. with funds from the Genome Institute of Singapore/the Agency for Science, Technology and Research, Singapore (GIS/03-113402).

Please address strain requests to M.K.B. and queries relating to microarray to J.L.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://ec.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abe, H., and C. Shimoda. 2000. Autoregulated expression of Schizosaccharomyces pombe meiosis-specific transcription factor Mei4 and a genome-wide search for its target genes. Genetics 154:1497-1508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bahler, J., and J. R. Pringle. 1998. Pom1p, a fission yeast protein kinase that provides positional information for both polarized growth and cytokinesis. Genes Dev. 12:1356-1370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bahler, J., J. Q. Wu, M. S. Longtine, N. G. Shah, A. McKenzie III, A. B. Steever, A. Wach, P. Philippsen, and J. R. Pringle. 1998. Heterologous modules for efficient and versatile PCR-based gene targeting in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Yeast 14:943-951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Balasubramanian, M. K., D. McCollum, L. Chang, K. C. Wong, N. I. Naqvi, X. He, S. Sazer, and K. L. Gould. 1998. Isolation and characterization of new fission yeast cytokinesis mutants. Genetics 149:1265-1275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beach, D., B. Durkacz, and P. Nurse. 1982. Functionally homologous cell cycle control genes in budding and fission yeast. Nature 300:706-709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beach, D., L. Rodgers, and J. Gould. 1985. ran1+ controls the transition from mitotic division to meiosis in fission yeast. Curr. Genet. 10:297-311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bernard, P., K. Hardwick, and J. P. Javerzat. 1998. Fission yeast bub1 is a mitotic centromere protein essential for the spindle checkpoint and the preservation of correct ploidy through mitosis. J. Cell Biol. 143:1775-1787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bresch, C., G. Muller, and R. Egel. 1968. Genes involved in meiosis and sporulation of a yeast. Mol. Gen. Genet. 102:301-306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen, D., W. M. Toone, J. Mata, R. Lyne, G. Burns, K. Kivinen, A. Brazma, N. Jones, and J. Bahler. 2003. Global transcriptional responses of fission yeast to environmental stress. Mol. Biol. Cell 14:214-229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Damagnez, V., T. P. Makela, and G. Cottarel. 1995. Schizosaccharomyces pombe Mop1-Mcs2 is related to mammalian CAK. EMBO J. 14:6164-6172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Degols, G., K. Shiozaki, and P. Russell. 1996. Activation and regulation of the Spc1 stress-activated protein kinase in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16:2870-2877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DeRisi, J. L., V. R. Iyer, and P. O. Brown. 1997. Exploring the metabolic and genetic control of gene expression on a genomic scale. Science 278:680-686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dhillon, N., and M. F. Hoekstra. 1994. Characterization of two protein kinases from Schizosaccharomyces pombe involved in the regulation of DNA repair. EMBO J. 13:2777-2788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eisen, M. B., P. T. Spellman, P. O. Brown, and D. Botstein. 1998. Cluster analysis and display of genome-wide expression patterns. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:14863-14868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fankhauser, C., and V. Simanis. 1994. The cdc7 protein kinase is a dosage dependent regulator of septum formation in fission yeast. EMBO J. 13:3011-3019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15a.Fujita, M., and M. Yamamoto. 1998. S. pombe sck2+, a second homologue of S. cerevisiae SCH9 in fission yeast, encodes a putative protein kinase closely related to PKA in function. Curr. Genet. 33:248-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hanks, S. K., and T. Hunter. 1995. Protein kinases 6. The eukaryotic protein kinase superfamily: kinase (catalytic) domain structure and classification. FASEB J. 9:576-596. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.He, X., M. H. Jones, M. Winey, and S. Sazer. 1998. Mph1, a member of the Mps1-like family of dual specificity protein kinases, is required for the spindle checkpoint in S. pombe. J. Cell Sci. 111:1635-1647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Higgins, D. G. 1994. CLUSTAL V: multiple alignment of DNA and protein sequences. Methods Mol. Biol. 25:307-318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoekstra, M. F., N. Dhillon, G. Carmel, A. J. DeMaggio, R. A. Lindberg, T. Hunter, and J. Kuret. 1994. Budding and fission yeast casein kinase I isoforms have dual-specificity protein kinase activity. Mol. Biol. Cell 5:877-886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang, T. Y., N. A. Markley, and D. Young. 2003. Nak1, an essential germinal center (GC) kinase regulates cell morphology and growth in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. J. Biol. Chem. 278:991-997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hughes, T. R., M. J. Marton, A. R. Jones, C. J. Roberts, R. Stoughton, C. D. Armour, H. A. Bennett, E. Coffey, H. Dai, Y. D. He, M. J. Kidd, A. M. King, M. R. Meyer, D. Slade, P. Y. Lum, S. B. Stepaniants, D. D. Shoemaker, D. Gachotte, K. Chakraburtty, J. Simon, M. Bard, and S. H. Friend. 2000. Functional discovery via a compendium of expression profiles. Cell 102:109-126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hunter, T. 1991. Protein kinase classification. Methods Enzymol. 200:3-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jin, M., M. Fujita, B. M. Culley, E. Apolinario, M. Yamamoto, K. Maundrell, and C. S. Hoffman. 1995. sck1, a high copy number suppressor of defects in the cAMP-dependent protein kinase pathway in fission yeast, encodes a protein homologous to the Saccharomyces cerevisiae SCH9 kinase. Genetics 140:457-467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23a.Karagiannis, J., A. Bimbo, S. Rajagopalan, J. Liu, and M. K. Balasubramanian. 2005. The nuclear kinase Lsk1p positively regulates the septation initiation network and promotes the successful completion of cytokinesis in response to perturbation of the actomyosin ring in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Mol. Biol. Cell 16:358-371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Keeney, J. B., and J. D. Boeke. 1994. Efficient targeted integration at leu1-32 and ura4-294 in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Genetics 136:849-856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim, K. H., Y. M. Cho, W. H. Kang, J. H. Kim, K. H. Byun, Y. D. Park, K. S. Bae, and H. M. Park. 2001. Negative regulation of filamentous growth and flocculation by Lkh1, a fission yeast LAMMER kinase homolog. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 289:1237-1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kobori, H., T. Toda, H. Yaguchi, M. Toya, M. Yanagida, and M. Osumi. 1994. Fission yeast protein kinase C gene homologues are required for protoplast regeneration: a functional link between cell wall formation and cell shape control. J. Cell Sci. 107:1131-1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Krien, M. J., S. J. Bugg, M. Palatsides, G. Asouline, M. Morimyo, and M. J. O'Connell. 1998. A NIMA homologue promotes chromatin condensation in fission yeast. J. Cell Sci. 111:967-976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee, M. S., T. Enoch, and H. Piwnica-Worms. 1994. mik1+ encodes a tyrosine kinase that phosphorylates p34cdc2 on tyrosine 15. J. Biol. Chem. 269:30530-30537. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Levin, D. E., and J. M. Bishop. 1990. A putative protein kinase gene (kin1+) is important for growth polarity in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87:8272-8276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Loewith, R., A. Hubberstey, and D. Young. 2000. Skh1, the MEK component of the mkh1 signaling pathway in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. J. Cell Sci. 113:153-160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marcus, S., A. Polverino, E. Chang, D. Robbins, M. H. Cobb, and M. H. Wigler. 1995. Shk1, a homolog of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae Ste20 and mammalian p65PAK protein kinases, is a component of a Ras/Cdc42 signaling module in the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:6180-6184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marton, M. J., J. L. DeRisi, H. A. Bennett, V. R. Iyer, M. R. Meyer, C. J. Roberts, R. Stoughton, J. Burchard, D. Slade, H. Dai, D. E. Bassett, Jr., L. H. Hartwell, P. O. Brown, and S. H. Friend. 1998. Drug target validation and identification of secondary drug target effects using DNA microarrays. Nat. Med. 4:1293-1301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Masai, H., T. Miyake, and K. Arai. 1995. hsk1+, a Schizosaccharomyces pombe gene related to Saccharomyces cerevisiae CDC7, is required for chromosomal replication. EMBO J. 14:3094-3104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Matsuo, T., Y. Kubo, Y. Watanabe, and M. Yamamoto. 2003. Schizosaccharomyces pombe AGC family kinase Gad8p forms a conserved signaling module with TOR and PDK1-like kinases. EMBO J. 22:3073-3083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Matsusaka, T., D. Hirata, M. Yanagida, and T. Toda. 1995. A novel protein kinase gene ssp1+ is required for alteration of growth polarity and actin localization in fission yeast. EMBO J. 14:3325-3338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Molz, L., and D. Beach. 1993. Characterization of the fission yeast mcs2 cyclin and its associated protein kinase activity. EMBO J. 12:1723-1732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36a.Moreno, S., A. Klar, and P. Nurse. 1991. Molecular genetic analysis of fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Methods Enzymol. 194:795-823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mukai, H., M. Miyahara, H. Takanaga, M. Kitagawa, H. Shibata, M. Shimakawa, and Y. Ono. 1995. Identification of Schizosaccharomyces pombe gene psk1+, encoding a novel putative serine/threonine protein kinase, whose mutation conferred resistance to phenylarsine oxide. Gene 166:155-159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Murakami, H., and H. Okayama. 1995. A kinase from fission yeast responsible for blocking mitosis in S phase. Nature 374:817-819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nakamura, T., M. Nakamura-Kubo, and C. Shimoda. 2002. Novel fission yeast Cdc7-Dbf4-like kinase complex required for the initiation and progression of meiotic second division. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22:309-320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Neiman, A. M., B. J. Stevenson, H. P. Xu, G. F. Sprague, Jr., I. Herskowitz, M. Wigler, and S. Marcus. 1993. Functional homology of protein kinases required for sexual differentiation in Schizosaccharomyces pombe and Saccharomyces cerevisiae suggests a conserved signal transduction module in eukaryotic organisms. Mol. Biol. Cell 4:107-120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Niederberger, C., and M. E. Schweingruber. 1999. A Schizosaccharomyces pombe gene, ksg1, that shows structural homology to the human phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase PDK1, is essential for growth, mating and sporulation. Mol. Gen. Genet. 261:177-183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nurse, P., and P. Thuriaux. 1980. Regulatory genes controlling mitosis in the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Genetics 96:627-637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ohkura, H., I. M. Hagan, and D. M. Glover. 1995. The conserved Schizosaccharomyces pombe kinase plo1, required to form a bipolar spindle, the actin ring, and septum, can drive septum formation in G1 and G2 cells. Genes Dev. 9:1059-1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pearce, A. K., and T. C. Humphrey. 2001. Integrating stress-response and cell-cycle checkpoint pathways. Trends Cell Biol. 11:426-433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pei, Y., and S. Shuman. 2003. Characterization of the Schizosaccharomyces pombe Cdk9/Pch1 protein kinase: Spt5 phosphorylation, autophosphorylation, and mutational analysis. J. Biol. Chem. 278:43346-43356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Petersen, J., J. Paris, M. Willer, M. Philippe, and I. M. Hagan. 2001. The S. pombe aurora-related kinase Ark1 associates with mitotic structures in a stage dependent manner and is required for chromosome segregation. J. Cell Sci. 114:4371-4384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Plyte, S. E., A. Feoktistova, J. D. Burke, J. R. Woodgett, and K. L. Gould. 1996. Schizosaccharomyces pombe skp1+ encodes a protein kinase related to mammalian glycogen synthase kinase 3 and complements a cdc14 cytokinesis mutant. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16:179-191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rasmussen, C., and G. Rasmussen. 1994. Inhibition of G2/M progression in Schizosaccharomyces pombe by a mutant calmodulin kinase II with constitutive activity. Mol. Biol. Cell 5:785-795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rhind, N., and P. Russell. 2000. Chk1 and Cds1: linchpins of the DNA damage and replication checkpoint pathways. J. Cell Sci. 113:3889-3896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Roberts, C. J., B. Nelson, M. J. Marton, R. Stoughton, M. R. Meyer, H. A. Bennett, Y. D. He, H. Dai, W. L. Walker, T. R. Hughes, M. Tyers, C. Boone, and S. H. Friend. 2000. Signaling and circuitry of multiple MAPK pathways revealed by a matrix of global gene expression profiles. Science 287:873-880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Robinson, D. R., Y. M. Wu, and S. F. Lin. 2000. The protein tyrosine kinase family of the human genome. Oncogene 19:5548-5557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rosenberg, G. H., S. K. Alahari, and N. F. Kaufer. 1991. prp4 from Schizosaccharomyces pombe, a mutant deficient in pre-mRNA splicing isolated using genes containing artificial introns. Mol. Gen. Genet. 226:305-309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Samejima, I., S. Mackie, and P. A. Fantes. 1997. Multiple modes of activation of the stress-responsive MAP kinase pathway in fission yeast. EMBO J. 16:6162-6170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Samejima, I., S. Mackie, E. Warbrick, R. Weisman, and P. A. Fantes. 1998. The fission yeast mitotic regulator win1+ encodes an MAP kinase kinase kinase that phosphorylates and activates Wis1 MAP kinase kinase in response to high osmolarity. Mol. Biol. Cell 9:2325-2335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Samejima, I., and M. Yanagida. 1994. Identification of cut8+ and cek1+, a novel protein kinase gene, which complement a fission yeast mutation that blocks anaphase. Mol. Cell. Biol. 14:6361-6371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Seger, R., D. Seger, F. J. Lozeman, N. G. Ahn, L. M. Graves, J. S. Campbell, L. Ericsson, M. Harrylock, A. M. Jensen, and E. G. Krebs. 1992. Human T-cell mitogen-activated protein kinase kinases are related to yeast signal transduction kinases. J. Biol. Chem. 267:25628-25631. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sengar, A. S., N. A. Markley, N. J. Marini, and D. Young. 1997. Mkh1, a MEK kinase required for cell wall integrity and proper response to osmotic and temperature stress in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17:3508-3519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shieh, J. C., M. G. Wilkinson, V. Buck, B. A. Morgan, K. Makino, and J. B. Millar. 1997. The Mcs4 response regulator coordinately controls the stress-activated Wak1-Wis1-Sty1 MAP kinase pathway and fission yeast cell cycle. Genes Dev. 11:1008-1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shimada, M., K. Nabeshima, T. Tougan, and H. Nojima. 2002. The meiotic recombination checkpoint is regulated by checkpoint rad+ genes in fission yeast. EMBO J. 21:2807-2818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shiozaki, K., and P. Russell. 1996. Conjugation, meiosis, and the osmotic stress response are regulated by Spc1 kinase through Atf1 transcription factor in fission yeast. Genes Dev. 10:2276-2288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Smith, D. A., W. M. Toone, D. Chen, J. Bahler, N. Jones, B. A. Morgan, and J. Quinn. 2002. The Srk1 protein kinase is a target for the Sty1 stress-activated MAPK in fission yeast. J. Biol. Chem. 277:33411-33421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Snell, V., and P. Nurse. 1994. Genetic analysis of cell morphogenesis in fission yeast-a role for casein kinase II in the establishment of polarized growth. EMBO J. 13:2066-2074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sugiura, R., T. Toda, S. Dhut, H. Shuntoh, and T. Kuno. 1999. The MAPK kinase Pek1 acts as a phosphorylation-dependent molecular switch. Nature 399:479-483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Takeuchi, M., and M. Yanagida. 1993. A mitotic role for a novel fission yeast protein kinase dsk1 with cell cycle stage dependent phosphorylation and localization. Mol. Biol. Cell 4:247-260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tallada, V. A., R. R. Daga, C. Palomeque, A. Garzon, and J. Jimenez. 2002. Genome-wide search of Schizosaccharomyces pombe genes causing overexpression-mediated cell cycle defects. Yeast 19:1139-1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]