ABSTRACT

Nipah virus (NiV) and Hendra virus (HeV) are pathogenic paramyxoviruses that cause mild-to-severe disease in humans. As members of the Henipavirus genus, NiV and HeV use an attachment (G) glycoprotein and a class I fusion (F) glycoprotein to invade host cells. The F protein rearranges from a metastable prefusion form to an extended postfusion form to facilitate host cell entry. Prefusion NiV F elicits higher neutralizing antibody titers than postfusion NiV F, indicating that stabilization of prefusion F may aid vaccine development. A combination of amino acid substitutions (L104C/I114C, L172F, and S191P) is known to stabilize NiV F in its prefusion conformation, although the extent to which substitutions transfer to other henipavirus F proteins is not known. Here, we perform biophysical and structural studies to investigate the mechanism of prefusion stabilization in F proteins from three henipaviruses: NiV, HeV, and Langya virus (LayV). Three known stabilizing substitutions from NiV F transfer to HeV F and exert similar structural and functional effects. One engineered disulfide bond, located near the fusion peptide, is sufficient to stabilize the prefusion conformations of both HeV F and LayV F. Although LayV F shares low overall sequence identity with NiV F and HeV F, the region around the fusion peptide exhibits high sequence conservation across all henipaviruses. Our findings indicate that substitutions targeting this site of conformational change might be applicable to prefusion stabilization of other henipavirus F proteins and support the use of NiV as a prototypical pathogen for henipavirus vaccine antigen design.

IMPORTANCE

Pathogenic henipaviruses such as Nipah virus (NiV) and Hendra virus (HeV) cause respiratory symptoms, with severe cases resulting in encephalitis, seizures, and coma. The work described here shows that the NiV and HeV fusion (F) proteins share common structural features with the F protein from an emerging henipavirus, Langya virus (LayV). Sequence alignment alone was sufficient to predict which known prefusion-stabilizing amino acid substitutions from NiV F would stabilize the prefusion conformations of HeV F and LayV F. This work also reveals an unexpected oligomeric interface shared by prefusion HeV F and NiV F. Together, these advances lay a foundation for future antigen design targeting henipavirus F proteins. In this way, Nipah virus can serve as a prototypical pathogen for the development of protective vaccines and monoclonal antibodies to prepare for potential henipavirus outbreaks.

KEYWORDS: Nipah, Hendra, Langya, prefusion, structure-based vaccine design, electron microscopy, paramyxovirus

INTRODUCTION

Nipah virus (NiV) and Hendra virus (HeV) are enveloped, pathogenic paramyxoviruses in the Henipavirus genus. NiV first emerged in humans in Malaysia in 1998. Since then, outbreaks in humans have occurred nearly every year in India and Bangladesh (1–3). HeV was first isolated in 1994 in Australia after an outbreak of respiratory disease in horses and humans in Hendra, a suburb of Brisbane, Queensland. Infections by NiV and HeV in humans cause fever and respiratory illness, with severe cases progressing to encephalitis, seizures, and coma. The estimated mortality rates for NiV and HeV infection are high, approximately 60%–70% (4–16). HeV has undergone zoonotic spillover from bats to horses and horses to humans (17). Although no human-to-human transmission has been documented for HeV, NiV infections can spread between humans through direct contact with infectious bodily fluids and respiratory droplets (18). NiV exhibits broad tropism and pathogenesis in mammalian species, including porcine and equine livestock, with humans often becoming infected through exposure to bats of the Pteropus genus (1, 9, 19–28). New henipaviruses have been described within the past 2 years, including Langya virus (LayV), which was recently detected in feverish patients in the Shandong and Henan provinces of China (29, 30), underscoring the need for continued development of vaccines and therapeutics against henipaviruses.

NiV and HeV use two envelope proteins, the attachment (G) and fusion (F) glycoproteins, to facilitate host cell recognition and entry (31). G binds the host receptors ephrin B2 and ephrin B3 (32), which triggers refolding of F from its compact prefusion form to its extended postfusion form during host cell infection. Given their localization to the viral surface and key role in the viral life cycle, both F and G are targets of the host immune response. Indeed, neutralizing antibodies have been discovered targeting both proteins (33), supporting F and G as attractive candidates for vaccine development (34, 35). A protein subunit vaccine for HeV, composed of the soluble G protein ectodomain (HeV-sG) (36–39), is approved for use in horses in Australia and is being evaluated in a phase I human clinical trial as a NiV vaccine (NCT04199169). Viral-vector vaccines encoding NiV G or F confer protection from NiV challenge in hamsters, pigs, ferrets, and non-human primates (40–49). An mRNA vaccine candidate for preventing NiV infection, composed of a chimeric NiV F and NiV G antigen, elicited a strong neutralizing antibody response and favorable NiV-specific T cell responses and is being evaluated in a phase I human clinical trial (NCT05398796). Additionally, prophylactic administration of antibodies against either G or F provides protection from NiV and HeV challenge in animal models (50–56). Despite these advances, no therapy or vaccine against NiV or other henipaviruses is approved for use in humans.

As class I fusion proteins, NiV F and HeV F are translated as single polypeptide precursors (F0) that form homotrimers. The F0 precursor is proteolytically cleaved into two disulfide-linked subunits, F1 and F2, constituting the mature protein (31). Each protomer is classified into three domains comprising Domain 1 (D1) on the lateral side, D2 on the membrane-proximal base, and D3 on the membrane-distal apex. A heptad repeat connects D2 to a transmembrane domain and a short C-terminal tail that extends into the NiV or HeV virions. The prefusion form of NiV F elicits a greater neutralizing immune response than the postfusion form, suggesting that prefusion-stabilized NiV F may be a superior vaccine antigen (34). The same work identified several amino acid substitutions that stabilized NiV F in its prefusion conformation. A disulfide substitution near the fusion peptide, L104C/I114C, was found to stabilize prefusion NiV F on its own, which was combined with two other substitutions (S191P and L172F) that increased expression in a triple-combination variant (34).

Motivated by the prototype pathogen approach to pandemic preparedness (57), here, we investigated whether the known stabilizing substitutions from NiV F could be incorporated into the F proteins of HeV and the recently emerged LayV. All three substitutions (one pair of cysteines that forms a disulfide bond, one cavity-filling, and one proline) increase expression of HeV F and LayV F relative to wild type. One of the substitutions, a disulfide bond located near the fusion peptide, was sufficient to stabilize the prefusion conformations of both HeV F and LayV F. Although LayV F shares low overall sequence identity with NiV F and HeV F, a multiple sequence alignment of henipavirus F proteins reveals high sequence conservation at this site of conformational change. These results suggest a common strategy for prefusion stabilization of other henipavirus F proteins and may aid in preparedness for future outbreaks of henipavirus-associated disease.

RESULTS

Analysis of known stabilizing substitutions from NiV F

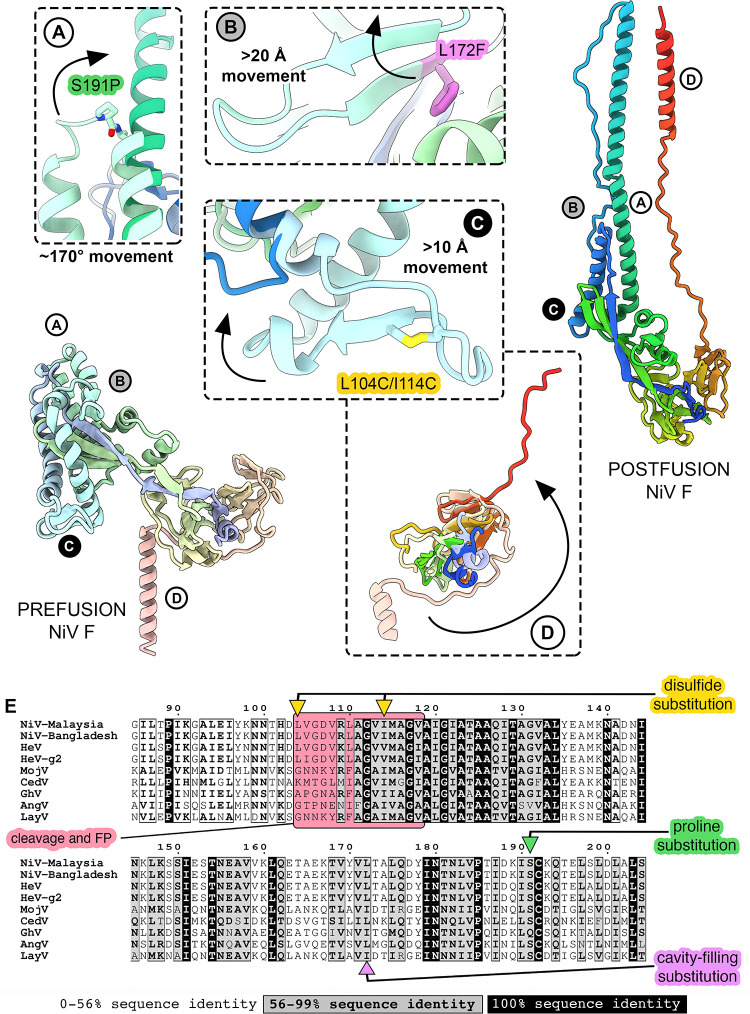

Previous work identified a combination of three substitutions that stabilize the prefusion conformation of NiV F: L104C/I114C, L172F, and S191P (34). Comparison of prefusion NiV F structures to a homology model of postfusion NiV F shows that the three stabilizing substitutions (disulfide bond, cavity-filling, and proline) are located at key sites of predicted conformational change (Fig. 1). The proline substitution S191P resides between two helices near the apex of D3 and disfavors a predicted ~170° rotation between the prefusion and postfusion states (Fig. 1A) (58). The cavity-filling substitution L172F is located in D3, within a β-hairpin that refolds into an α-helix in the postfusion state (Fig. 1B). The disulfide substitution L104C/I114C sits adjacent to the fusion peptide on a loop that rearranges during fusion: Leu104 and Ile114 are predicted to separate by ~20 Å between prefusion and postfusion NiV F (Fig. 1C). None of the substitutions directly target the movement of the heptad repeat B (Fig. 1D), although this construct does include a GCN4 trimerization motif that stabilizes the close association of the C-terminal heptad repeats. Indeed, a similar trimerization motif was used to stabilize the prefusion F protein of parainfluenza virus (PIV) 5, now called mammalian orthorubulavirus 5 (59).

Fig 1.

Known prefusion-stabilizing substitutions from NiV F target three sites of predicted conformational change. Two ribbon diagrams of individual protomers of prefusion (far left, pale rainbow) and postfusion (far right, bright rainbow) NiV F. The N-terminal ends are colored blue, the C-terminal ends are colored red. (A–D) Circled letters indicate areas of interest and correspond to zoomed views in panels A, B, C, and D. Arrows in panels A–D indicate broad conformational movements from prefusion (pale colors) to postfusion (bright colors). In some panels, the movement to postfusion is out of frame and is indicated by a distance or angle estimate. (E) Multiple sequence alignment of F proteins from nine henipaviruses: Henipavirus nipahense (Malaysia strain, AAK29087.1), Henipavirus nipahense (Bangladesh strain, AAY43915.1), Henipavirus hendraense (NP_047111.2), Henipavirus hendraense (g2 strain, UCY33687.1), Henipavirus mòjiāngense (YP_009094094.1), Henipavirus cedarense (YP_009094085.1), Henipavirus ghanaense (YP_009091837.1), Langya virus (UUV47240.1), and Angavokely virus (UVG43988.1). The region near the fusion peptide and cleavage site is colored with a light red box. Sites of stabilizing substitutions in NiV F are indicated with colored arrows: disulfide (yellow), cavity-filling (purple), and proline (green). Sequence conservation is colored according to the legend at the bottom of (E).

Stabilizing substitutions from NiV F transfer to HeV F

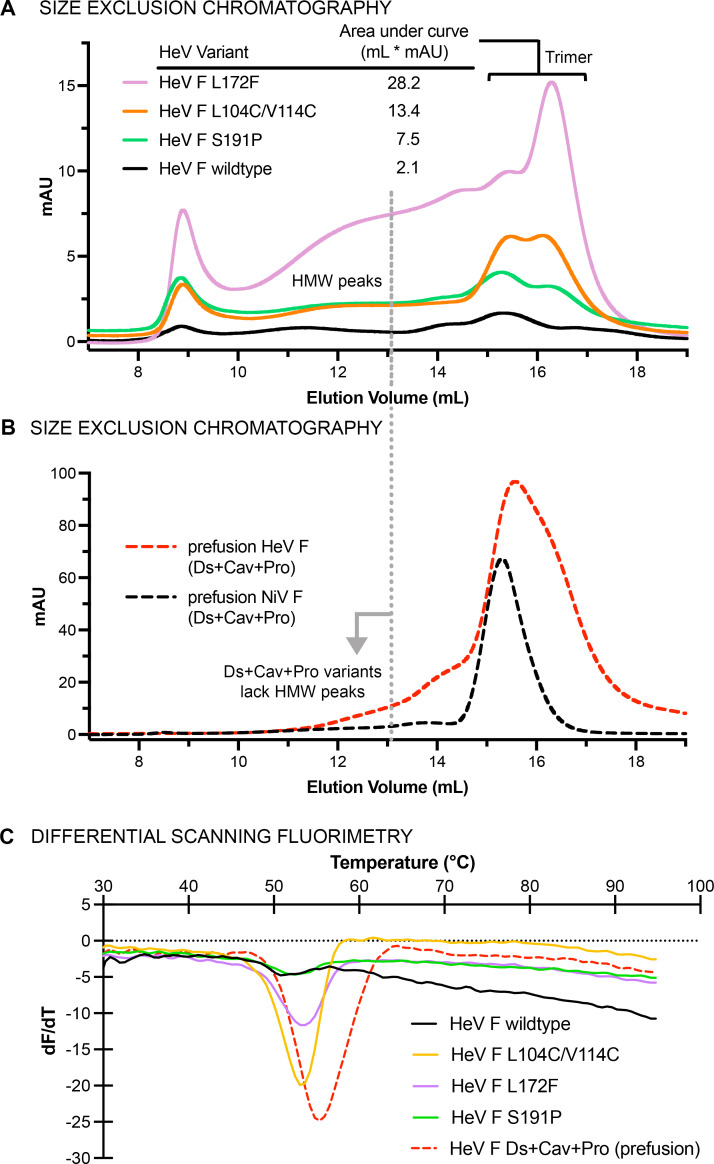

NiV F and HeV F share high amino acid sequence identity (~90%) and a high degree of tertiary structure similarity (<1 Å root mean square deviation [RMSD] over all Cα atoms), so we surmised that HeV F might accommodate all three substitutions from NiV F (Fig. 1E). To assess the effect of single substitutions from NiV F on the stability of HeV F, we expressed and purified wild-type HeV F ectodomain (Australia 1994 strain) containing either the proline, cavity-filling, or disulfide substitutions from NiV F (Fig. 2). All HeV F constructs contained a C-terminal tag composed of a GCN4 trimerization motif, a 6X-His tag, and a Twin-Strep-tag. Residues at two substitution sites (S191P and L172F) were identical between NiV F and HeV F, whereas residues at the third substitution site are similar (L104C/V114C in HeV F; L104C/I114C in NiV F; Fig. 1E). When separated by size-exclusion chromatography (SEC), all HeV F single variants exhibited high-molecular-weight peaks in addition to a trimer peak (Fig. 2A). Each of the three substitutions increased the purified protein yield compared to wild-type HeV F: ~10-fold for L172F, ~5-fold for L104C/V114C, and ~3-fold S191P. Inclusion of all three substitutions (L104C/V114C, L172F, and S191P) reduced the appearance of high-molecular-weight peaks, with the elution peak consistent with F protein trimers (Fig. 2B). Large-scale transient transfections of the HeV F triple variant yielded 1–2 mg of F protein from 1 L of FreeStyle 293-F cell culture. Thermal stability analysis by differential scanning fluorimetry (DSF) revealed melting temperatures (Tm) of 52°C–54°C for wild-type HeV F and the single variants, with the L104C/V114C variant having a Tm of 54°C (Fig. 2C). Combination of all three stabilizing substitutions increased the Tm to 56°C. Interestingly, the peak height for the wild-type HeV F variant was diminished relative to the substitution variants. The DSF traces for all variants showed almost linear changes in dF/dT over the range of 65°C–95°C, with wild-type HeV F displaying the greatest overall decrease in dF/dT within that range, which suggests the lack of a single unfolding temperature for this variant.

Fig 2.

Purification and characterization of prefusion-stabilized Hendra virus F protein. (A–B) SEC of wild-type HeV F, single variants and the triple variant. UV traces for disulfide, cavity-filling, and proline substitutions are colored orange, purple, and green, respectively. The dotted line extending from (A) into (B) shows the position of high-molecular-weight peaks for the single variants, which disappear when all three substitutions are combined. Trimeric HeV F and NiV F are shown as dashed red and black traces, respectively. (C) DSF of wild-type HeV F and variants, showing the change in fluorescence with respect to temperature (dF/dT) as a function of temperature (°C). The colors of the DSF traces are the same as in the SEC traces from panels A and B.

Structural analysis by negative-stain electron microscopy revealed that the wild-type HeV F ectodomain adopts the postfusion conformation (Fig. S1A). The cavity-filling L172F variant did not appear to adopt either the prefusion or postfusion conformation, and large soluble aggregates were visible in the electron micrographs (Fig. S1B). The proline substitution variant S191P formed mostly postfusion F with a minority (~25%) of prefusion F, whereas the L104C/V114C variant was all prefusion (Fig. S1C and D). Thus, the three stabilizing substitutions from NiV F all increased protein yield and overall stability, but only one (L104C/V114C) was sufficient to stabilize the prefusion conformation on its own.

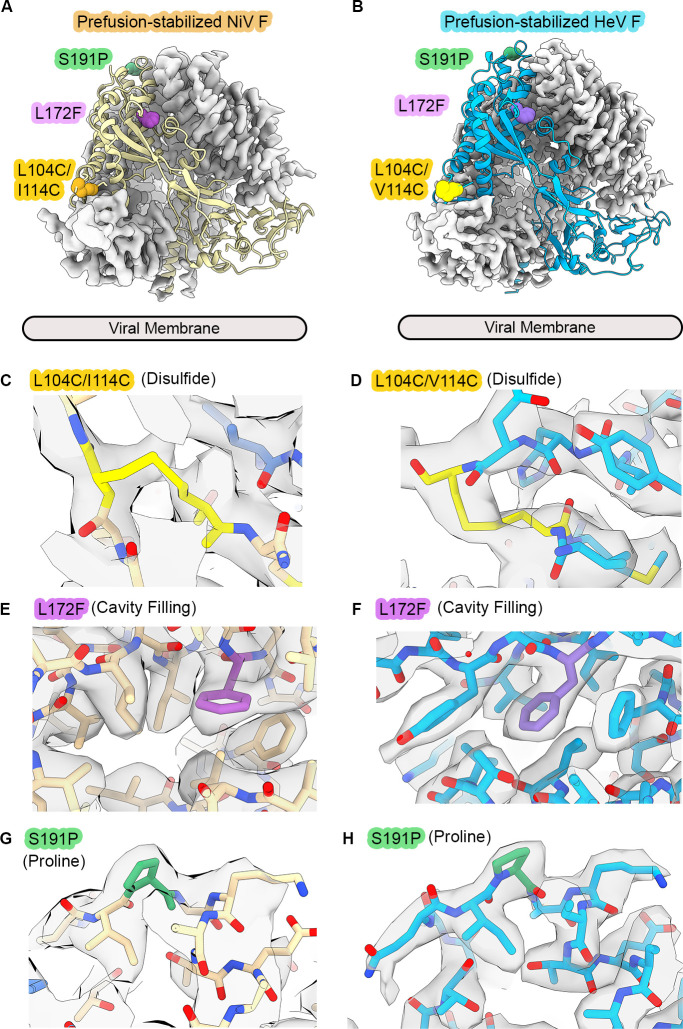

To visualize the combined effects of these substitutions, we determined the structures of prefusion-stabilized NiV F and HeV F by cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) (Fig. 3A and B; Table S1; Fig. S2 through S5). We used the apo form of NiV F, since previous structures of this variant were determined in complex with neutralizing antibodies (60). In the apo state, prefusion-stabilized NiV F and HeV F adopt conformations closely resembling previously determined structures (0.7 Å and 0.5 Å RMSD over all Cα atoms relative to Protein Data Bank [PDB] IDs 5EVM and 7KI6 for NiV F and HeV F, respectively) (56). We observed clear features for each stabilizing substitution in the Coulomb potential maps (hereafter, cryo-EM maps) (Fig. 3C through H). Visual inspection of the two structures indicates that stabilizing substitutions from NiV F exert similar structural effects when transferred to HeV F. Importantly, the substitutions do not alter the local conformations of the surrounding residues, with all-atom RMSDs of <1 Å over 15 amino acid windows surrounding the substitution sites (Fig. S6). Despite extensive effort, we could not find any two- or three-dimensional (2D or 3D) classes for postfusion NiV F or HeV F, suggesting that the three stabilizing substitutions are sufficient to preserve the prefusion conformation under these conditions.

Fig 3.

Cryo-EM structures of prefusion-stabilized NiV F and HeV F. (A–B) Cryo-EM maps and models of prefusion-stabilized NiV F (A) and HeV F (B). Two protomers are represented as light gray cryo-EM maps, and the third protomer is shown as a ribbon (yellow for NiV F, blue for HeV F). Atoms corresponding to the three substitutions are shown as colored spheres (L104C/V114C are gold, S191P is green, L172F is purple). The viral membrane is shown as a gray tube. (C–G) Zoomed views of models and cryo-EM maps near the sites of disulfide (C–D), cavity-filling (E–F), and proline (G–H) substitutions. The cryo-EM maps are shown as a transparent gray surface.

The disulfide substitution near the fusion peptide stabilizes prefusion Langya virus F

Application of known stabilizing substitutions from one virus to another led to efficient development of an effective vaccine antigen for the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) (61). While we were beginning work on HeV F, the LayV F genome was published. We then decided to investigate the limits of stabilizing substitution transferability for henipaviruses, testing whether the prefusion-stabilizing substitutions from NiV F could be transferred into the LayV F protein, which shares much lower sequence identity (44%) with NiV F than does HeV F (90%).

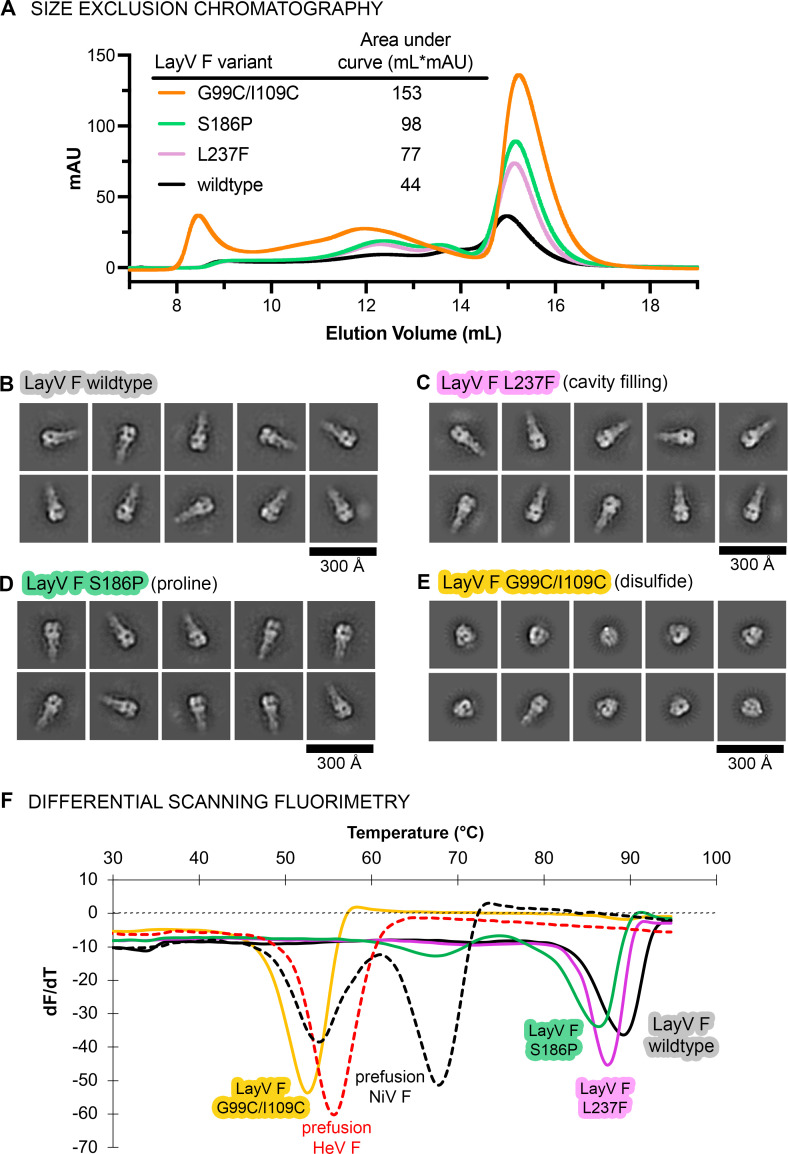

We designed four variants of the LayV F protein, using the multiple sequence alignment of all the henipavirus F proteins to guide the placement of substitutions (Fig. 1E): a wild-type ectodomain sequence truncated just before the predicted transmembrane domain (GenBank accession code: UUV47240.1, residues 1–474), a cavity-filling substitution variant (L237F), a proline substitution variant (S186P), and a disulfide substitution variant (G99C/I109C). The proline and disulfide substitutions in LayV F were made at sites homologous to NiV F (S191P and L104C/I114C). For the cavity-filling substitution, an analogous change at position Ile167 was discarded to account for a predicted steric clash in a homology model for LayV F. We chose the substitution L237F for LayV F, which aimed to fill a predicted internal cavity that was adjacent to Ile167. All LayV F constructs contained a C-terminal foldon trimerization motif from T4 fibritin, a human rhinovirus (HRV) 3C protease cut site, an 8X-His tag, and a Twin-Strep-tag.

We expressed, purified, and characterized the wild-type LayV F ectodomain and three substitution variants. All four proteins yielded monodisperse SEC peaks consistent with the formation of LayV F trimers (Fig. 4A). All three substitutions improved the protein yield: the cavity-filling, proline, and disulfide substitutions increased the area under the SEC curve by 1.8-fold, 2.2-fold, and 3.4-fold, respectively, relative to wild type (Fig. 4A). Purified proteins (fractions corresponding to ~12 mL–18 mL elution volume from SEC, both high molecular weight [HMW], and low molecular weight [LMW] peaks) were then analyzed by negative-stain EM to assess their conformations. Classification in 2D revealed that the wild-type, cavity-filling (L237F), and proline (S186P) variants adopted the postfusion conformation (Fig. 4B through D), whereas the disulfide (G99C/I109C) variant showed mostly (>90%) prefusion particles with a minority (<10%) of postfusion particles (Fig. 4E). We next performed DSF on the LayV F variants to assess their thermal stability (Fig. 4F). The wild-type LayV F, S186P, and L237F variants exhibited high Tms of 89, 86 and 88°C, respectively, indicative of the highly stable postfusion conformation. In contrast, the Tm for the LayV F disulfide variant G99C/I109C was 53°C, which falls close to the Tm values for prefusion-stabilized NiV F and HeV F, which were included as positive controls in this experiment (54°C and 56°C, respectively; Fig. 4F) (34).

Fig 4.

A disulfide substitution near the fusion peptide stabilizes prefusion LayV F. (A) SEC of LayV F wild-type (WT) and three variants. The UV traces are overlaid for wild-type (black), G99C/I109C (orange), S186P (green), and L237F (purple). (B–E) negative-stain EM analysis of LayV F, showing 2D class averages for (B) wild-type LayV F ectodomain and three variants: (C) L237F, (D) S186P, and (E) G99C/I109C. (F) DSF of LayV F showing the change in fluorescence with respect to temperature (dF/dT) as a function of temperature (°C). The LayV F WT, S186P, L237F, and G99C/I109C variants are shown as solid black, green, purple, and yellow traces, respectively. Controls for prefusion NiV F and prefusion HeV F are shown as dashed black and red traces, respectively.

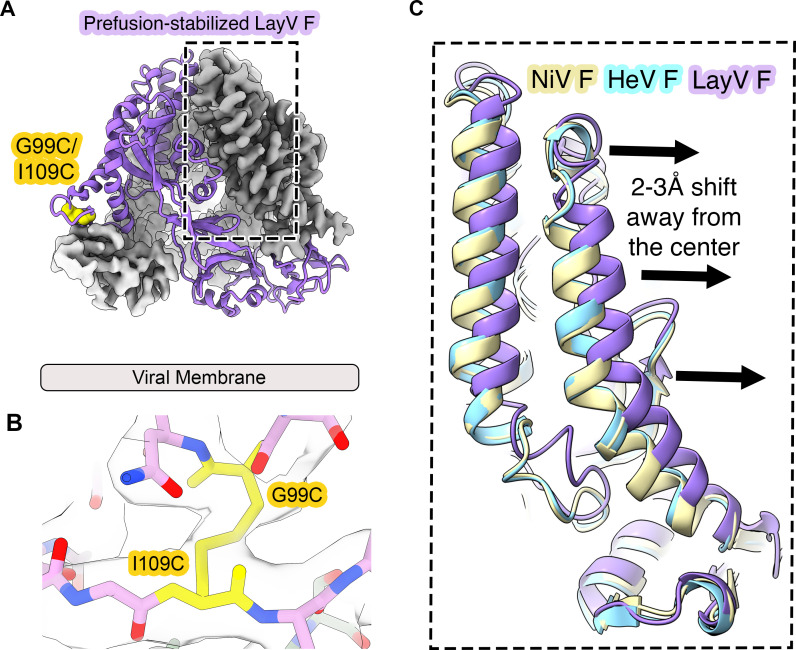

To further evaluate the LayV F G99C/I109C variant, we determined its structure by cryo-EM to a resolution of 3.6 Å (Fig. 5A; Table S1; Fig. S7 and S8). We observed clear features in the cryo-EM map for the disulfide bond at positions 99 and 109, indicating that this bond forms as predicted and stabilizes the prefusion conformation (Fig. 5B). The overall architecture of LayV F G99C/I109C closely resembles the recently published structure of wild-type prefusion LayV F (0.5 Å RMSD over all Cα atoms relative to PDB ID: 8FMX) as well as other prefusion henipavirus F proteins (~1.8 Å RMSD over all Cα atoms relative to NiV F and HeV F), although subtle differences do exist within D3 (62). Indeed, the prefusion LayV F trimer interface in the apex of D3 is noticeably open relative to NiV F and HeV F, with some helices exhibiting a ~3 Å shift away from the central threefold axis of symmetry (Fig. 5C). Collectively, these data demonstrate that the stabilizing disulfide substitution G99C/I109C does not alter the prefusion conformation of LayV F.

Fig 5.

Cryo-EM structure of prefusion-stabilized LayV F G99C/I109C. (A) Cryo-EM map and model of the disulfide-stabilized LayV F variant G99C/I109C. One protomer is shown as a purple ribbon diagram and the cryo-EM map is shown for the other two protomers. (B) Zoomed view of the LayV F model within a transparent gray cryo-EM map at the disulfide substitution site. The cysteines at positions 99 and 109 are colored yellow. (C) Overlay of the prefusion models of NiV F (pale yellow), HeV F (cyan), and LayV F G99C/I109C (purple). The direction of the outward shift of the LayV F helix relative to NiV F and HeV F is indicated with arrows.

Cryo-EM structures of prefusion HeV F and NiV F reveal dimers-of-trimers

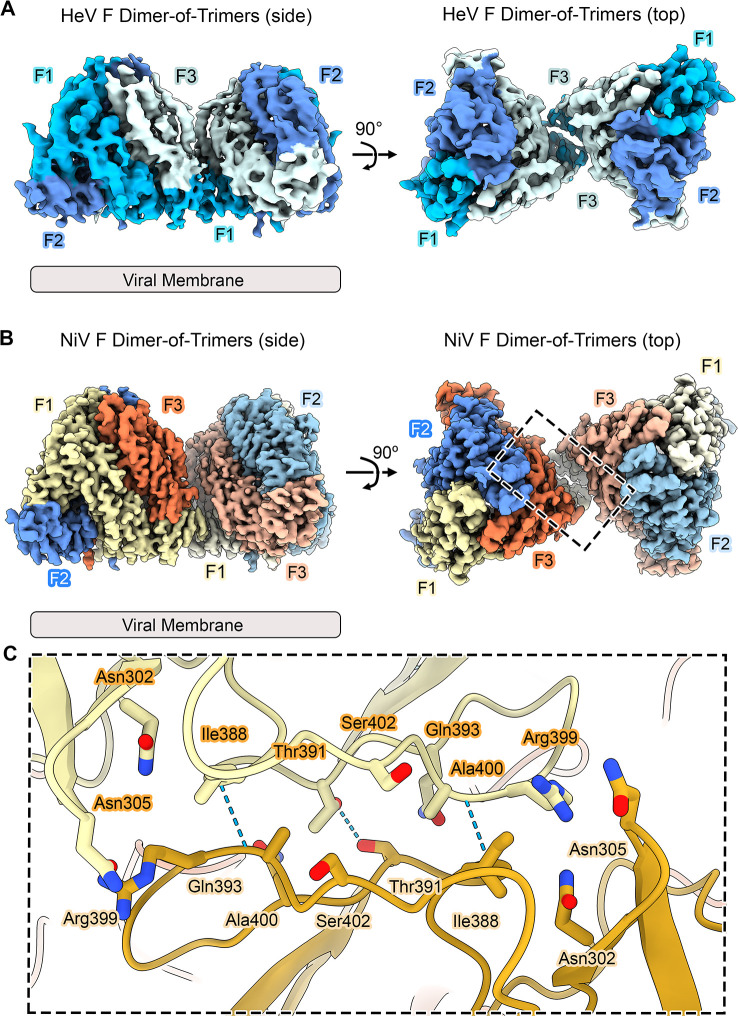

During particle classification of prefusion HeV F and NiV F, we observed 2D class averages that contained two sets of F trimers in close proximity (Fig. S2 and S4). Further classification and refinement resulted in a low-resolution (>4 Å) 3D reconstruction of a dimer of HeV F trimers (Fig. 6A; Table S1; Fig. S4). Analysis of the NiV F data set yielded a higher-resolution structure (gold standard Fourier Shell Correlation [GSFSC] resolution of 3.2 Å, 3D Fourier Shell Correlation [FSC] resolution of 3.8 Å, Fig. 6B; Table S1; Fig. S2 and S3). The quality of the NiV F cryo-EM map was sufficient to model a dimer of NiV F trimers. A dimer-of-trimers was also observed for LayV F (GSFSC resolution of 3.9 Å, 3D FSC resolution of 4.0 Å resolution, Table S1; Fig. S7 and S8). The map quality of the LayV F dimer-of-trimers was not sufficient to build a model for the whole protein complex, although a rigid body dock of the LayV F trimer showed a good fit to the map with clear side chain features at the dimer-of-trimers interface (Fig. S8).

Fig 6.

Cryo-EM structures of HeV F and NiV F dimers-of-trimers. (A) Side and top views of the cryo-EM map of a HeV F dimer-of trimers. Individual HeV F protomers (F1, F2, and F3) are colored in shades of blue. (B) Side and top views of a NiV F dimer-of-trimers. NiV F protomers are colored yellow, blue, and red. (C) Interface between two NiV F protomers on adjacent trimers. Side chains of residues at the dimer-of-trimers interface are shown as sticks. Hydrogen bonds are shown as light blue dashes.

The NiV F dimer-of-trimers forms inter-trimer contacts near the membrane-proximal base of prefusion NiV F, located within Domains 1 and 2, and additional contacts within the lateral face (Fig. 6B). Each trimer buries 1,004 Å2 of surface area on the other, with the interface composed of a mixture of electrostatic interactions and hydrogen bonds that flank a central hydrophobic strip (Fig. 6C). Importantly, the prefusion-stabilizing substitutions are located away from the interface and do not participate in any intermolecular contacts. Several neutralizing antibodies recognize epitopes that overlap directly with this interface, whereas other neutralizing antibodies do not bind this interface directly but would prevent dimerization of the trimers due to steric clashes (Fig. S9). The C-terminal ends of the NiV F homotrimers point in the same direction (<10° angle difference), suggesting that the native viral membrane environment would not preclude formation of this dimer-of-trimers and may in fact support it by restricting movement of the molecules to a 2D plane. The LayV F dimer-of-trimers uses a different interface and would require bending of the F protein by ~60° to accommodate formation in the membrane.

A previous structural study reported evidence that prefusion NiV F can form hexamers in a crystal, so we compared those interfaces with the dimer interface we observed by cryo-EM (63). Interestingly, the dimer interface reported here does not occur in the proposed hexamer-of-trimers from the crystal structure, although it does resemble an additional interface from the crystal lattice that bridges adjacent hexamers (Fig. S10). Larger assemblies (e.g., hexamers) that use combinations of the interfaces in the crystal lattice are also consistent with anchorage in the viral envelope. The physiological relevance of these oligomeric assemblies remains unknown but will be pursued in further studies.

We did not observe any dimers-of-trimers of NiV F or HeV F in solution by SEC, despite concentrating the proteins to ~90 µM. This suggests that the local concentration of NiV F and HeV F was increased within the EM grid itself. Indeed, we estimate a concentration of 200 µM–400 µM for NiV F and HeV F trimers within the vitreous ice of the grid, taking into account the observed particle densities and assuming an ice thickness of 20 nm–30 nm. Such concentrations are difficult to attain in solution, although increased local concentration within the native viral membrane might favor one or more of the proposed modes of NiV F and HeV F oligomerization (64, 65).

DISCUSSION

Our results show how stabilizing substitutions target conformational changes between prefusion and postfusion NiV F. Knowledge of this process informed our understanding of prefusion stabilization in two related henipavirus F proteins of both high and low sequence homology, HeV F and LayV F, respectively. One disulfide bond near the fusion peptide is sufficient to stabilize HeV F and LayV F, suggesting that disulfide substitutions at homologous regions could achieve prefusion stabilization in other henipavirus F proteins and allow rapid design and deployment of vaccine candidates if a henipavirus presents a public health emergency of regional or international concern. Our structural studies also revealed an unexpected oligomeric interface shared by HeV F and NiV F.

Prefusion stabilization in NiV F, HeV F, and LayV F bears similarity with other class I fusion proteins. Indeed, the three types of substitutions employed here (proline, cavity-filling, and disulfide bond) have been successfully applied to proteins in other virus families including Pneumoviridae, Arenaviridae, Coronaviridae, Filoviridae, and Retroviridae. The introduction of helix-capping prolines at similar sites of conformational change is a feature of prefusion-stabilized variants of influenza hemagglutinin (HA), respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) F protein, Lassa virus GP, coronavirus spike proteins, Ebola virus GP, and the HIV-1 envelope protein (61, 66–74). Each of these examples involves the formation of a coiled-coil in the postfusion state, consistent with the propensity for proline to destabilize helix formation (75). The NiV cavity-filling substitution L172F resides in a region of NiV F that is predicted to rearrange during the prefusion-to-postfusion transition. The L172F substitution resembles F488W in a prefusion-stabilized variant of the RSV F protein: each variant introduces a ring-stacking interaction while filling an internal cavity, thereby generating additional intramolecular interactions that may shift the conformational equilibrium in favor of the prefusion state. The cavity-filling substitutions here are not sufficient to stabilize the prefusion conformation, although they do increase expression alone and in combination with the prefusion-stabilizing substitution L104C/V114C for HeV F. Similar disulfides have been used to stabilize domain movements between prefusion and postfusion conformations, including for human metapneumovirus (hMPV) F, PIV3 F, RSV F and SARS-CoV-2 spike (76–78). Although the disulfide substitution here can be transferred from NiV F to LayV F, favorable sequence alignment does not necessarily predict transferability of a disulfide bond. Indeed, residues at positions Ala125 and Ile160 in hMPV F align well with an engineered disulfide for RSV F (S155C/S290C), but hMPV F cannot accommodate this disulfude due to a 1.4 Å shift in the Cα atoms relative to RSV F (69, 77, 79).

While both HeV F and LayV F can accommodate the known substitutions from NiV F, each substitution exerted subtle differences in the context of either HeV F or LayV F. The disulfide bond increased protein expression of both HeV F and LayV F to a similar degree and was critical for stabilizing their prefusion conformations. The proline substitution stabilized a minority of the HeV F particles in the prefusion conformation, but none of the LayV F particles. The cavity-filling substitution caused the greatest increase in protein expression for HeV F but only exerted a marginal effect on expression of LayV F. The effect of a given stabilizing substitution may thus depend on its local chemical environment. Indeed, similar substitutions exhibit different thermal stability profiles in either LayV F or HeV F, suggesting that the viral background plays a significant role in determining the extent to which a given substitution may be beneficial to thermal stability.

Additionally, amino acid substitutions are not the only way to stabilize prefusion henipavirus F proteins: inclusion of a trimerization tag (clamp2) on the C-terminus of LayV F enabled high-resolution structure determination of prefusion wild-type LayV F (80). The clamp2 motif forms a stable six-helix bundle, which may better stabilize HR2 than either the GCN4 or foldon tags used here and by others (62, 81). A comparison of C-terminal trimerization motifs (GCN4, foldon, and tandem GCN4/foldon) in chimeric prefusion NiV F and NiV G mRNA and protein subunit vaccines did not show significant differences in neutralizing titer, suggesting that the identity of the trimerization motif may have little impact on immunogenicity (35). Future combinations of amino acid substitutions and oligomerization scaffolds may be necessary to produce henipavirus F proteins with suitable biochemical properties for use as a vaccine antigen. We note that a limitation of this study is the lack of immunogenicity experiments, which will be performed during further investigation of LayV F stabilization.

The existence of dimers-of-trimers of prefusion NiV F, HeV F, and LayV F in our EM grids, as well as hexameric forms observed in a crystal lattice for NiV F (63), raises the possibility that such higher-order oligomeric structures may form on virions. The buried surface areas are consistent with the size expected for a biological interface, and the orientations of the membrane-proximal heptad repeats at the C-terminal end would be compatible with formation in the native viral membrane. Dimers of RSV F homotrimers have been observed on vitrified virions by cryo-electron tomography (82). Their overall architecture resembles the oligomers we report here in solution, suggesting that higher-order oligomerization may be a general property of paramyxovirus and pneumovirus fusion proteins. Indeed, electron micrographs of the related paramyxoviruses PIV3 and Sendai virus show closely packed proteins on the exterior of the viral envelope, although no high-resolution sub-tomogram averaging of paramyxovirus F protein oligomers has been performed to date (83, 84). At the present time, the physiological relevance of the dimers of homotrimers remains unknown. This is an important area of research that we hope is addressed in future papers, likely via the generation of recombinant viruses or pseudoviruses.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

NiV F, HeV F, and LayV F expression and purification

NiV F (residues 26–488) and HeV F (residues 1–488) containing prefusion-stabilizing substitutions, a GCN4 trimerization motif, and a C-terminal thrombin/6X-His/Strep tag were transiently transfected in HEK 293F cells. The NiV F plasmid had an N-terminal artificial signal peptide from mouse interleukin 2 (MYSMQLASCVTLTLVLLVNS). LayV F (residues 1–474) contained a C-terminal foldon trimerization motif from T4 fibritin, an HRV 3C protease cut site, an 8X-His tag, and a Twin-Strep tag. Full sequences are available in Table S2. Briefly, plasmid DNA was mixed with polyethyleneimine (PEI) at a ratio of 9:1 PEI:DNA (wt/wt) and added to HEK293-F cell cultures in suspension. Transfected cells were maintained in a shaking incubator (37°C, 8% CO2) in Freestyle 293 medium (ThermoFisher Scientific). Six days after transfection, the growth medium was harvested by centrifugation, concentrated, and buffer exchanged into 1× phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). This solution was passed over StrepTactin affinity resin (IBA Life Sciences), washed with 1× PBS and eluted with 100 mM Tris pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, and 2.5 mM desthiobiotin. Elution fractions containing purified F proteins were concentrated using centrifugal filters and separated by SEC (Superose 6, Cytiva). The SEC running buffer was 2 mM Tris pH 8.0, 200 mM NaCl, 0.02% (wt/vol) sodium azide. Fractions corresponding to NiV F, HeV F, and LayV F were concentrated in centrifugal filters, aliquoted, and flash frozen in liquid nitrogen. Full sequences are in Table S2.

Negative-stain EM sample preparation, data collection, and processing

Purified HeV F and LayV F samples were diluted to working concentrations of 0.05 mg/mL and immediately deposited onto a glow-discharged, supported carbon copper grids (Formvar, 400 mesh). For all variants of a given F protein (HeV F or LayV F), purification and negative staining were performed in parallel under identical conditions. Both HMW and LMW peaks were taken for analysis by negative-stain EM to assess the conformational heterogeneity and oligomeric state of the whole preparation. Grids were blotted on filter paper, then washed in a series of six 40 µL drops of 2% aqueous uranyl acetate (wt/vol) at pH 4.5. After the final wash, the grid was blotted on filter paper, air dried, and loaded into a transmission electron microscope. We used two microscopes for negative-stain EM: (i) a Japan Electron Optics Laboratory (JEOL) 2010F transmission electron microscope (TEM) operating at 200 kV with a nominal magnification of 60,000× (pixel size = 3.6 Å) and (ii) a JEOL NEOARM in TEM mode operating at 200 kV with a nominal magnification of 50,000× (pixel size = 2.7 Å). Both microscopes were equipped with OneView cameras (Gatan). Micrographs were acquired in 2k × 2k mode for the JEOL 2010F and 4k × 4k mode for the JEOL NEOARM. Contrast transfer function estimation (CTF), particle picking, and 2D classification were performed in cryoSPARC v4 (Structura Biotechnology) (85). For the disulfide variants of HeV F and LayV F, we processed extensively in 2D to look for postfusion-like classes but were only able to find compact, prefusion-like classes. At least two grids were examined under high magnification to ensure similar sample quality before imaging a single grid.

Cryo-EM sample preparation and data collection

For the cryo-EM structures of NiV F, HeV F, and LayV F, SEC-purified protein was used. The prefusion trimer peak from SEC (fractions corresponding to ~15 mL–18 mL elution volume) was concentrated, aliquoted, and frozen. Frozen aliquots were thawed in a room temperature water bath and centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 10 minutes to remove any insoluble aggregates. Purified NiV F, HeV F, and LayV F were concentrated to 3 mg/mL and prepared in 2 mM Tris pH 8, 200 mM NaCl, 0.01% (wt/vol) sodium azide with 0.1% (wt/vol) amphipol A8-35. About 3 µL of solution was added onto plasma cleaned AuFlat 1.2/1.3, 300 mesh grids (Protochips). Grids were blotted for 5–7 seconds, then plunge frozen in liquid ethane using a Vitrobot Mark IV (ThermoFisher). The chamber humidity was 100% and the temperature was 25°C. Grids were loaded onto a Talos Glacios TEM equipped with a Falcon 4 detector (ThermoFisher). Movies were recorded in EER format using SerialEM. The calibrated pixel size was 0.94 Å/pixel. Additional information about data collection parameters is included in Table S1; an overview of all the maps is shown in Fig. S11.

Cryo-EM data processing, refinement, and model building

Motion correction, CTF estimation, and particle picking were performed using cryoSPARC Live. Micrographs and picked particles were exported into cryoSPARC, then subjected to iterative rounds of 2D classification and template picking, followed by 3D ab initio reconstruction and heterogeneous/homogeneous/non-uniform refinement. For the structure of the prefusion NiV F trimer, we attempted 3D refinement as well as reclassification and refinement of several classes from the initial heterogeneous refinement. We chose the highest resolution reconstruction to guide model building. The initial models for prefusion NiV F and HeV F were PDB 6TYS and 5EJB, respectively (55, 86). The 5B3 antibody was removed from 6TYS prior to building. For the initial model for LayV F, we generated a homology model in SwissModel using a prefusion crystal structure of NiV F (5EVM) as a template (63). Models were first fit into the experimental cryo-EM maps in ChimeraX. Iterative rounds of manual building and automated refinement were performed in Coot, ISOLDE/ChimeraX, and Phenix (87–90). Additional information about data processing, refinement, and model building is shown in Table S1.

Differential scanning fluorimetry

Concentrated protein stock solutions were diluted to 0.6 mg/mL, then added to white wall, 96-well PCR plates. To 15 µL of 0.6 mg/mL protein solution was added 5 µL of dilute SYPRO Orange dye (~83-fold diluted, from 5,000× to 60×) and the two were mixed by pipetting. The dilution buffer was 2 mM Tris pH 8, 200 mM NaCl. The tray was sealed with clear tape, centrifuged, and loaded into a differential scanning fluorimeter (Roche LightCycler 480 II). SYPRO orange fluorescence was recorded as a function of increasing temperature (room temperature to 95°C). Raw fluorescence traces were analyzed in the manufacturer’s Roche LightCycler software. Apparent melting temperatures correspond to peaks in the plot of the first derivative of the fluorescence trace with respect to temperature (dF/dT) as a function of temperature.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Karalee Jarvis, Raluca Gearba, Michelle Mikesh, Xun Zhan, and Axel Brilot for technical assistance with negative-stain EM (K.J., R.G., M.M., and X.Z.) and cryo-EM (A.B.). We thank Kaci Erwin and James Guerra for technical assistance with mammalian cell culture. We thank Maria Cantelli for administrative support. We thank Gretel Torres and Ryan McCool for a careful reading of this manuscript.

This research was funded in part by a grant from The Welch Foundation (F-0003-19620604 to J.S.M.).

Conceptualization: R.J.L., P.O.B., J.S.M., and B.S.G.; Investigation: P.O.B., E.G.B., B.E.F., D.R.A., A.R.R., and R.J.L.; Visualization: P.O.B., E.G.B., and R.J.L.; Writing – Original draft: P.O.B. and R.J.L.; Writing – Reviewing and editing: P.O.B., J.S.M., and R.J.L.; Supervision: J.S.M., B.S.G., and R.J.L.

Contributor Information

Rebecca J. Loomis, Email: rebeccajo.x.loomis@gsk.com.

Jason S. McLellan, Email: jmclellan@austin.utexas.edu.

Christiane E. Wobus, University of Michigan Medical School, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA

DATA AVAILABILITY

EM maps and coordinate files are publicly available in the EMDB and PDB, respectively. The accession codes for each structure are: NiV F trimer (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/emdb/EMD-27566; https://www.rcsb.org/structure/8DNG); NiV F dimer-of-trimers (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/emdb/EMD-27590, https://www.rcsb.org/structure/8DO4); HeV trimer (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/emdb/EMD-27577, https://www.rcsb.org/structure/8DNR); HeV F dimer-of-trimers (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/emdb/EMD-42940); LayV F trimer (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/emdb/EMD-41825, https://www.rcsb.org/structure/8U1R); LayV F dimer-of-trimers (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/emdb/EMD-42942). Full amino acid sequences for NiV F, HeV F and LayV F can be found in Table S2.

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

The following material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1128/jvi.01372-23.

Figures S1 to S11; Tables S1 and S2.

ASM does not own the copyrights to Supplemental Material that may be linked to, or accessed through, an article. The authors have granted ASM a non-exclusive, world-wide license to publish the Supplemental Material files. Please contact the corresponding author directly for reuse.

REFERENCES

- 1. Chua KB, Bellini WJ, Rota PA, Harcourt BH, Tamin A, Lam SK, Ksiazek TG, Rollin PE, Zaki SR, Shieh W, Goldsmith CS, Gubler DJ, Roehrig JT, Eaton B, Gould AR, Olson J, Field H, Daniels P, Ling AE, Peters CJ, Anderson LJ, Mahy BW. 2000. Nipah virus: a recently emergent deadly paramyxovirus. Science 288:1432–1435. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5470.1432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chua KB, Goh KJ, Wong KT, Kamarulzaman A, Tan PS, Ksiazek TG, Zaki SR, Paul G, Lam SK, Tan CT. 1999. Fatal encephalitis due to Nipah virus among pig-farmers in Malaysia. Lancet 354:1257–1259. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)04299-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mohd Nor MN, Gan CH, Ong BL. 2000. Nipah virus infection of pigs in peninsular Malaysia. Rev Sci Tech 19:160–165. doi: 10.20506/rst.19.1.1202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Arankalle VA, Bandyopadhyay BT, Ramdasi AY, Jadi R, Patil DR, Rahman M, Majumdar M, Banerjee PS, Hati AK, Goswami RP, Neogi DK, Mishra AC. 2011. Genomic characterization of Nipah virus, West Bengal, India. Emerg Infect Dis 17:907–909. doi: 10.3201/eid1705.100968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Goh KJ, Tan CT, Chew NK, Tan PS, Kamarulzaman A, Sarji SA, Wong KT, Abdullah BJ, Chua KB, Lam SK. 2000. Clinical features of Nipah virus encephalitis among pig farmers in Malaysia. N Engl J Med 342:1229–1235. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200004273421701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Arunkumar G, Chandni R, Mourya DT, Singh SK, Sadanandan R, Sudan P, Bhargava B, Nipah Investigators People and Health Study Group . 2019. Outbreak investigation of Nipah virus disease in Kerala, India, 2018. J Infect Dis 219:1867–1878. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiy612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Banerjee S, Gupta N, Kodan P, Mittal A, Ray Y, Nischal N, Soneja M, Biswas A, Wig N. 2019. Nipah virus disease: a rare and intractable disease. Intractable Rare Dis Res 8:1–8. doi: 10.5582/irdr.2018.01130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chadha MS, Comer JA, Lowe L, Rota PA, Rollin PE, Bellini WJ, Ksiazek TG, Mishra A. 2006. Nipah virus-associated encephalitis outbreak, Siliguri, India. Emerg Infect Dis 12:235–240. doi: 10.3201/eid1202.051247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ching PKG, de los Reyes VC, Sucaldito MN, Tayag E, Columna-Vingno AB, Malbas FF, Bolo GC, Sejvar JJ, Eagles D, Playford G, Dueger E, Kaku Y, Morikawa S, Kuroda M, Marsh GA, McCullough S, Foxwell AR. 2015. Outbreak of henipavirus infection, Philippines, 2014. Emerg Infect Dis 21:328–331. doi: 10.3201/eid2102.141433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gurley ES, Montgomery JM, Hossain MJ, Bell M, Azad AK, Islam MR, Molla MAR, Carroll DS, Ksiazek TG, Rota PA, Lowe L, Comer JA, Rollin P, Czub M, Grolla A, Feldmann H, Luby SP, Woodward JL, Breiman RF. 2007. Person-to-person transmission of Nipah virus in a Bangladeshi community. Emerg Infect Dis 13:1031–1037. doi: 10.3201/eid1307.061128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Harcourt BH, Lowe L, Tamin A, Liu X, Bankamp B, Bowden N, Rollin PE, Comer JA, Ksiazek TG, Hossain MJ, Gurley ES, Breiman RF, Bellini WJ, Rota PA. 2005. Genetic characterization of Nipah virus. Emerg Infect Dis 11:1594–1597. doi: 10.3201/eid1110.050513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hsu VP, Hossain MJ, Parashar UD, Ali MM, Ksiazek TG, Kuzmin I, Niezgoda M, Rupprecht C, Bresee J, Breiman RF. 2004. Nipah virus encephalitis reemergence, Bangladesh. Emerg Infect Dis 10:2082–2087. doi: 10.3201/eid1012.040701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Luby S.P., Gurley ES, Hossain MJ. 2009. Transmission of human infection with Nipah virus. Clin Infect Dis 49:1743–1748. doi: 10.1086/647951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Luby SP, Hossain MJ, Gurley ES, Ahmed BN, Banu S, Khan SU, Homaira N, Rota PA, Rollin PE, Comer JA, Kenah E, Ksiazek TG, Rahman M. 2009. Recurrent zoonotic transmission of Nipah virus into humans, Bangladesh, 2001-2007. Emerg Infect Dis 15:1229–1235. doi: 10.3201/eid1508.081237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ochani RK, Batra S, Shaikh A, Asad A. 2019. Nipah virus - the rising epidemic: a review. Infez Med 27:117–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sweileh WM. 2017. Global research trends of world health organization’s top eight emerging pathogens. Global Health 13:9. doi: 10.1186/s12992-017-0233-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Field H, Schaaf K, Kung N, Simon C, Waltisbuhl D, Hobert H, Moore F, Middleton D, Crook A, Smith G, Daniels P, Glanville R, Lovell D. 2010. Hendra virus outbreak with novel clinical features, Australia. Emerg Infect Dis 16:338–340. doi: 10.3201/eid1602.090780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Luby SP. 2013. The pandemic potential of Nipah virus. Antiviral Res 100:38–43. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2013.07.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Clayton BA. 2017. Nipah virus: transmission of a zoonotic paramyxovirus. Curr Opin Virol 22:97–104. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2016.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Clayton BA, Wang LF, Marsh GA. 2013. Henipaviruses: an updated review focusing on the pteropid reservoir and features of transmission. Zoonoses Public Health 60:69–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1863-2378.2012.01501.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gurley ES, Hegde ST, Hossain K, Sazzad HMS, Hossain MJ, Rahman M, Sharker MAY, Salje H, Islam MS, Epstein JH, Khan SU, Kilpatrick AM, Daszak P, Luby SP. 2017. Convergence of humans, bats, trees, and culture in Nipah virus transmission, Bangladesh. Emerg Infect Dis 23:1446–1453. doi: 10.3201/eid2309.161922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. AbuBakar S, Chang L-Y, Ali ARM, Sharifah SH, Yusoff K, Zamrod Z. 2004. Isolation and molecular identification of Nipah virus from pigs. Emerg Infect Dis 10:2228–2230. doi: 10.3201/eid1012.040452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ang BSP, Lim TCC, Wang L. 2018. Nipah virus infection. J Clin Microbiol 56:e01875-17. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01875-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chua KB. 2003. Nipah virus outbreak in Malaysia. J Clin Virol 26:265–275. doi: 10.1016/s1386-6532(02)00268-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Field H, Young P, Yob JM, Mills J, Hall L, Mackenzie J. 2001. The natural history of Hendra and Nipah viruses. Microbes Infect 3:307–314. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(01)01384-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Geisbert TW, Feldmann H, Broder CC. 2012. Animal challenge models of henipavirus infection and pathogenesis. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 359:153–177. doi: 10.1007/82_2012_208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Glennon EE, Restif O, Sbarbaro SR, Garnier R, Cunningham AA, Suu-Ire RD, Osei-Amponsah R, Wood JLN, Peel AJ. 2018. Domesticated animals as hosts of henipaviruses and filoviruses: a systematic review. Vet J 233:25–34. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2017.12.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Yob JM, Field H, Rashdi AM, Morrissy C, van der Heide B, Rota P, bin Adzhar A, White J, Daniels P, Jamaluddin A, Ksiazek T. 2001. Nipah virus infection in bats (order chiroptera) in peninsular Malaysia. Emerg Infect Dis 7:439–441. doi: 10.3201/eid0703.010312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Zhang X-A, Li H, Jiang F-C, Zhu F, Zhang Y-F, Chen J-J, Tan C-W, Anderson DE, Fan H, Dong L-Y, Li C, Zhang P-H, Li Y, Ding H, Fang L-Q, Wang L-F, Liu W. 2022. A zoonotic henipavirus in febrile patients in China. N Engl J Med 387:470–472. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2202705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Haas GD, Lee B. 2023. Paramyxoviruses from bats: changes in receptor specificity and their role in host adaptation. Curr Opin Virol 58:101292. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2022.101292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lamb RA, Kolakofsky D. 1996. Paramyxoviridae: the viruses and their replication, p 1340. In Fields BN, Knipe DM, Howley PM (ed), Fundamental Virology, 3rd ed. Lippincott-Raven. xv, Philadelphia. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bonaparte MI, Dimitrov AS, Bossart KN, Crameri G, Mungall BA, Bishop KA, Choudhry V, Dimitrov DS, Wang L-F, Eaton BT, Broder CC. 2005. Ephrin-B2 ligand is a functional receptor for Hendra virus and Nipah virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102:10652–10657. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504887102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Tamin A, Harcourt BH, Lo MK, Roth JA, Wolf MC, Lee B, Weingartl H, Audonnet J-C, Bellini WJ, Rota PA. 2009. Development of a neutralization assay for Nipah virus using pseudotype particles. J Virol Methods 160:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2009.02.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Loomis RJ, Stewart-Jones GBE, Tsybovsky Y, Caringal RT, Morabito KM, McLellan JS, Chamberlain AL, Nugent ST, Hutchinson GB, Kueltzo LA, Mascola JR, Graham BS. 2020. Structure-based design of Nipah virus vaccines: a generalizable approach to paramyxovirus immunogen development. Front Immunol 11:842. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.00842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Loomis RJ, DiPiazza AT, Falcone S, Ruckwardt TJ, Morabito KM, Abiona OM, Chang LA, Caringal RT, Presnyak V, Narayanan E, Tsybovsky Y, Nair D, Hutchinson GB, Stewart-Jones GBE, Kueltzo LA, Himansu S, Mascola JR, Carfi A, Graham BS. 2021. Chimeric fusion (F) and attachment (G) glycoprotein antigen delivery by mRNA as a candidate Nipah vaccine. Front Immunol 12:772864. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.772864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Pallister J, Middleton D, Wang L-F, Klein R, Haining J, Robinson R, Yamada M, White J, Payne J, Feng Y-R, Chan Y-P, Broder CC. 2011. A recombinant Hendra virus G glycoprotein-based subunit vaccine protects ferrets from lethal Hendra virus challenge. Vaccine 29:5623–5630. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.06.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Middleton D, Pallister J, Klein R, Feng Y-R, Haining J, Arkinstall R, Frazer L, Huang J-A, Edwards N, Wareing M, Elhay M, Hashmi Z, Bingham J, Yamada M, Johnson D, White J, Foord A, Heine HG, Marsh GA, Broder CC, Wang L-F. 2014. Hendra virus vaccine, a one health approach to protecting horse, human, and environmental health. Emerg Infect Dis 20:372–379. doi: 10.3201/eid2003.131159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Steffen DL, Xu K, Nikolov DB, Broder CC. 2012. Henipavirus mediated membrane fusion, virus entry and targeted therapeutics. Viruses 4:280–308. doi: 10.3390/v4020280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Tan R, Hodge A, Klein R, Edwards N, Huang JA, Middleton D, Watts SP. 2018. Virus-neutralising antibody responses in horses following vaccination with Equivac(R) HeV: a field study. Aust Vet J 96:161–166. doi: 10.1111/avj.12694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Guillaume V, Contamin H, Loth P, Georges-Courbot M-C, Lefeuvre A, Marianneau P, Chua KB, Lam SK, Buckland R, Deubel V, Wild TF. 2004. Nipah virus: vaccination and passive protection studies in a hamster model. J Virol 78:834–840. doi: 10.1128/jvi.78.2.834-840.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Keshwara R, Shiels T, Postnikova E, Kurup D, Wirblich C, Johnson RF, Schnell MJ. 2019. Erratum: publisher correction: rabies-based vaccine induces potent immune responses against Nipah virus. NPJ Vaccines 4:18. doi: 10.1038/s41541-019-0112-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Keshwara R, Shiels T, Postnikova E, Kurup D, Wirblich C, Johnson RF, Schnell MJ. 2019. Rabies-based vaccine induces potent immune responses against Nipah virus. NPJ Vaccines 4:15. doi: 10.1038/s41541-019-0112-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kurup D, Wirblich C, Feldmann H, Marzi A, Schnell MJ. 2015. Rhabdovirus-based vaccine platforms against henipaviruses. J Virol 89:144–154. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02308-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lo MK, Bird BH, Chattopadhyay A, Drew CP, Martin BE, Coleman JD, Rose JK, Nichol ST, Spiropoulou CF. 2014. Single-dose replication-defective VSV-based Nipah virus vaccines provide protection from lethal challenge in syrian hamsters. Antiviral Res 101:26–29. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2013.10.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Mire CE, Geisbert JB, Agans KN, Versteeg KM, Deer DJ, Satterfield BA, Fenton KA, Geisbert TW. 2019. Use of single-injection recombinant vesicular stomatitis virus vaccine to protect nonhuman primates against lethal Nipah virus disease. Emerg Infect Dis 25:1144–1152. doi: 10.3201/eid2506.181620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Mire CE, Versteeg KM, Cross RW, Agans KN, Fenton KA, Whitt MA, Geisbert TW. 2013. Single injection recombinant vesicular Stomatitis virus vaccines protect ferrets against lethal Nipah virus disease. Virol J 10:353. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-10-353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ploquin A, Szécsi J, Mathieu C, Guillaume V, Barateau V, Ong KC, Wong KT, Cosset F-L, Horvat B, Salvetti A. 2013. Protection against henipavirus infection by use of recombinant adeno-associated virus-vector vaccines. J Infect Dis 207:469–478. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Weingartl HM, Berhane Y, Caswell JL, Loosmore S, Audonnet J-C, Roth JA, Czub M. 2006. Recombinant Nipah virus vaccines protect pigs against challenge. J Virol 80:7929–7938. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00263-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Yoneda M, Georges-Courbot M-C, Ikeda F, Ishii M, Nagata N, Jacquot F, Raoul H, Sato H, Kai C. 2013. Recombinant measles virus vaccine expressing the Nipah virus glycoprotein protects against lethal Nipah virus challenge. PLoS One 8:e58414. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0058414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Bossart KN, Geisbert TW, Feldmann H, Zhu Z, Feldmann F, Geisbert JB, Yan L, Feng Y-R, Brining D, Scott D, Wang Y, Dimitrov AS, Callison J, Chan Y-P, Hickey AC, Dimitrov DS, Broder CC, Rockx B. 2011. A neutralizing human monoclonal antibody protects African green monkeys from Hendra virus challenge. Sci Transl Med 3:105ra103. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Bossart KN, Zhu Z, Middleton D, Klippel J, Crameri G, Bingham J, McEachern JA, Green D, Hancock TJ, Chan Y-P, Hickey AC, Dimitrov DS, Wang L-F, Broder CC. 2009. A neutralizing human monoclonal antibody protects against lethal disease in a new ferret model of acute Nipah virus infection. PLoS Pathog 5:e1000642. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Zhu Z, Bossart KN, Bishop KA, Crameri G, Dimitrov AS, McEachern JA, Feng Y, Middleton D, Wang L-F, Broder CC, Dimitrov DS. 2008. Exceptionally potent cross-reactive neutralization of Nipah and Hendra viruses by a human monoclonal antibody. J Infect Dis 197:846–853. doi: 10.1086/528801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Zhu Z, Dimitrov AS, Bossart KN, Crameri G, Bishop KA, Choudhry V, Mungall BA, Feng Y-R, Choudhary A, Zhang M-Y, Feng Y, Wang L-F, Xiao X, Eaton BT, Broder CC, Dimitrov DS. 2006. Potent neutralization of Hendra and Nipah viruses by human monoclonal antibodies. J Virol 80:891–899. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.2.891-899.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Chan Y-P, Lu M, Dutta S, Yan L, Barr J, Flora M, Feng Y-R, Xu K, Nikolov DB, Wang L-F, Skiniotis G, Broder CC. 2012. Biochemical, conformational, and immunogenic analysis of soluble trimeric forms of henipavirus fusion glycoproteins. J Virol 86:11457–11471. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01318-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Dang HV, Chan Y-P, Park Y-J, Snijder J, Da Silva SC, Vu B, Yan L, Feng Y-R, Rockx B, Geisbert TW, Mire CE, Broder CC, Veesler D. 2019. An antibody against the F glycoprotein inhibits Nipah and Hendra virus infections. Nat Struct Mol Biol 26:980–987. doi: 10.1038/s41594-019-0308-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Dang HV, Cross RW, Borisevich V, Bornholdt ZA, West BR, Chan Y-P, Mire CE, Da Silva SC, Dimitrov AS, Yan L, Amaya M, Navaratnarajah CK, Zeitlin L, Geisbert TW, Broder CC, Veesler D. 2021. Broadly neutralizing antibody cocktails targeting Nipah virus and Hendra virus fusion glycoproteins. Nat Struct Mol Biol 28:426–434. doi: 10.1038/s41594-021-00584-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Cassetti MC, Pierson TC, Patterson LJ, Bok K, DeRocco AJ, Deschamps AM, Graham BS, Erbelding EJ, Fauci AS. 2023. Prototype pathogen approach for vaccine and monoclonal antibody development: a critical component of the NIAID plan for pandemic preparedness. J Infect Dis 227:1433–1441. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiac296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Ramachandran GN, Ramakrishnan C, Sasisekharan V. 1963. Stereochemistry of polypeptide chain configurations. J Mol Biol 7:95–99. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(63)80023-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Yin H-S, Wen X, Paterson RG, Lamb RA, Jardetzky TS. 2006. Structure of the parainfluenza virus 5 F protein in its metastable, prefusion conformation. Nature 439:38–44. doi: 10.1038/nature04322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Byrne PO, Fisher BE, Ambrozak DR, Blade EG, Tsybovsky Y, Graham BS, McLellan JS, Loomis RJ. 2023. Structural basis for antibody recognition of vulnerable epitopes on Nipah virus F protein. Nature Communications. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-36995-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 61. Corbett KS, Edwards DK, Leist SR, Abiona OM, Boyoglu-Barnum S, Gillespie RA, Himansu S, Schäfer A, Ziwawo CT, DiPiazza AT, et al. 2020. SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine design enabled by prototype pathogen preparedness. Nature 586:567–571. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2622-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Watterson D, Wijesundara DK, Modhiran N, Mordant FL, Li Z, Avumegah MS, McMillan CL, Lackenby J, Guilfoyle K, van Amerongen G, et al. 2021. Preclinical development of a molecular clamp-stabilised subunit vaccine for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2. Clin Transl Immunology 10:e1269. doi: 10.1002/cti2.1269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Xu K, Chan Y-P, Bradel-Tretheway B, Akyol-Ataman Z, Zhu Y, Dutta S, Yan L, Feng Y, Wang L-F, Skiniotis G, Lee B, Zhou ZH, Broder CC, Aguilar HC, Nikolov DB. 2015. Crystal structure of the pre-fusion Nipah virus fusion glycoprotein reveals a novel hexamer-of-trimers assembly. PLoS Pathog 11:e1005322. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Grasberger B, Minton AP, DeLisi C, Metzger H. 1986. Interaction between proteins localized in membranes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 83:6258–6262. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.17.6258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Saxton MJ, Jacobson K. 1997. Single-particle tracking: applications to membrane dynamics. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct 26:373–399. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.26.1.373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Kirchdoerfer RN, Cottrell CA, Wang N, Pallesen J, Yassine HM, Turner HL, Corbett KS, Graham BS, McLellan JS, Ward AB. 2016. Pre-fusion structure of a human coronavirus spike protein. Nature 531:118–121. doi: 10.1038/nature17200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Qiao H, Pelletier SL, Hoffman L, Hacker J, Armstrong RT, White JM. 1998. Specific single or double proline substitutions in the "spring-loaded" coiled-coil region of the influenza hemagglutinin impair or abolish membrane fusion activity. J Cell Biol 141:1335–1347. doi: 10.1083/jcb.141.6.1335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Krarup A, Truan D, Furmanova-Hollenstein P, Bogaert L, Bouchier P, Bisschop IJM, Widjojoatmodjo MN, Zahn R, Schuitemaker H, McLellan JS, Langedijk JPM. 2015. A highly stable prefusion RSV F vaccine derived from structural analysis of the fusion mechanism. Nat Commun 6:8143. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Battles MB, Más V, Olmedillas E, Cano O, Vázquez M, Rodríguez L, Melero JA, McLellan JS. 2017. Structure and immunogenicity of pre-fusion-stabilized human metapneumovirus F glycoprotein. Nat Commun 8:1528. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01708-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Hastie KM, Zandonatti MA, Kleinfelter LM, Heinrich ML, Rowland MM, Chandran K, Branco LM, Robinson JE, Garry RF, Saphire EO. 2017. Structural basis for antibody-mediated neutralization of Lassa virus. Science 356:923–928. doi: 10.1126/science.aam7260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Pallesen J, Wang N, Corbett KS, Wrapp D, Kirchdoerfer RN, Turner HL, Cottrell CA, Becker MM, Wang L, Shi W, Kong W-P, Andres EL, Kettenbach AN, Denison MR, Chappell JD, Graham BS, Ward AB, McLellan JS. 2017. Immunogenicity and structures of a rationally designed prefusion MERS-CoV spike antigen. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 114:E7348–E7357. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1707304114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Rutten L, Gilman MSA, Blokland S, Juraszek J, McLellan JS, Langedijk JPM. 2020. Structure-based design of prefusion-stabilized filovirus glycoprotein trimers. Cell Rep 30:4540–4550. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.03.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Sanders RW, Vesanen M, Schuelke N, Master A, Schiffner L, Kalyanaraman R, Paluch M, Berkhout B, Maddon PJ, Olson WC, Lu M, Moore JP. 2002. Stabilization of the soluble, cleaved, trimeric form of the envelope glycoprotein complex of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol 76:8875–8889. doi: 10.1128/jvi.76.17.8875-8889.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Wrapp D, Mu Z, Thakur B, Janowska K, Ajayi O, Barr M, Parks R, Hahn BH, Acharya P, Saunders KO, Haynes BF. 2023. Structure-based stabilization of SOSIP Env enhances recombinant ectodomain durability and yield. Journal of Virology. doi: 10.1128/jvi.01673-22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 75. O’Neil KT, DeGrado WF. 1990. A thermodynamic scale for the Helix-forming tendencies of the commonly occurring amino acids. Science 250:646–651. doi: 10.1126/science.2237415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Stewart-Jones GBE, Chuang G-Y, Xu K, Zhou T, Acharya P, Tsybovsky Y, Ou L, Zhang B, Fernandez-Rodriguez B, Gilardi V, et al. 2018. Structure-based design of a quadrivalent fusion glycoprotein vaccine for human parainfluenza virus types 1-4. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 115:12265–12270. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1811980115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. McLellan JS, Chen M, Joyce MG, Sastry M, Stewart-Jones GBE, Yang Y, Zhang B, Chen L, Srivatsan S, Zheng A, et al. 2013. Structure-based design of a fusion glycoprotein vaccine for respiratory syncytial virus. Science 342:592–598. doi: 10.1126/science.1243283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Hsieh C-L, Goldsmith JA, Schaub JM, DiVenere AM, Kuo H-C, Javanmardi K, Le KC, Wrapp D, Lee AG, Liu Y, Chou C-W, Byrne PO, Hjorth CK, Johnson NV, Ludes-Meyers J, Nguyen AW, Park J, Wang N, Amengor D, Lavinder JJ, Ippolito GC, Maynard JA, Finkelstein IJ, McLellan JS. 2020. Structure-based design of prefusion-stabilized SARS-CoV-2 spikes. Science 369:1501–1505. doi: 10.1126/science.abd0826 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Kwong P, Joyce M, Zhang B, Yang Y, Collins P, Buchholz U, Corti D, Lanzavecchia A, Stewart Jones G. 2019, issued . https://patents.google.com/patent/US11027007B2.

- 80. Isaacs A, Low YS, Macauslane KL, Seitanidou J, Pegg CL, Cheung STM, Liang B, Scott CAP, Landsberg MJ, Schulz BL, Chappell KJ, Modhiran N, Watterson D. 2023. Structure and antigenicity of divergent henipavirus fusion glycoproteins. Nat Commun 14:3577. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-39278-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. May AJ, Pothula KR, Janowska K, Acharya P. 2023. Structures of Langya virus fusion protein ectodomain in pre- and postfusion conformation. J Virol 97:e0043323. doi: 10.1128/jvi.00433-23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Sibert BS, Kim JY, Yang JE, Ke Z, Stobart CC, Moore MM, Wright ER. 2021. Respiratory syncytial virus matrix protein assembles as a lattice with local and extended order that coordinates the position of the fusion glycoprotein. bioRxiv. doi: 10.1101/2021.10.13.464285 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Gui L, Jurgens EM, Ebner JL, Porotto M, Moscona A, Lee KK. 2015. Electron tomography imaging of surface glycoproteins on human parainfluenza virus 3: association of receptor binding and fusion proteins before receptor engagement. mBio 6:e02393-14. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02393-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Loney C, Mottet-Osman G, Roux L, Bhella D. 2009. Paramyxovirus ultrastructure and genome packaging: cryo-electron tomography of sendai virus. J Virol 83:8191–8197. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00693-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Punjani A, Rubinstein JL, Fleet DJ, Brubaker MA. 2017. cryoSPARC: algorithms for rapid unsupervised cryo-EM structure determination. Nat Methods 14:290–296. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Wong JJW, Paterson RG, Lamb RA, Jardetzky TS. 2016. Structure and stabilization of the Hendra virus F glycoprotein in its prefusion form. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113:1056–1061. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1523303113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Emsley P, Cowtan K. 2004. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Croll TI. 2018. ISOLDE: a physically realistic environment for model building into low-resolution electron-density maps. Acta Crystallogr D Struct Biol 74:519–530. doi: 10.1107/S2059798318002425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Liebschner D, Afonine PV, Baker ML, Bunkóczi G, Chen VB, Croll TI, Hintze B, Hung L-W, Jain S, McCoy AJ, Moriarty NW, Oeffner RD, Poon BK, Prisant MG, Read RJ, Richardson JS, Richardson DC, Sammito MD, Sobolev OV, Stockwell DH, Terwilliger TC, Urzhumtsev AG, Videau LL, Williams CJ, Adams PD. 2019. Macromolecular structure determination using X-rays, neutrons and electrons: recent developments in Phenix. Acta Crystallogr D Struct Biol 75:861–877. doi: 10.1107/S2059798319011471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Goddard TD, Huang CC, Meng EC, Pettersen EF, Couch GS, Morris JH, Ferrin TE. 2018. UCSF chimerax: meeting modern challenges in visualization and analysis. Protein Sci 27:14–25. doi: 10.1002/pro.3235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figures S1 to S11; Tables S1 and S2.

Data Availability Statement

EM maps and coordinate files are publicly available in the EMDB and PDB, respectively. The accession codes for each structure are: NiV F trimer (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/emdb/EMD-27566; https://www.rcsb.org/structure/8DNG); NiV F dimer-of-trimers (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/emdb/EMD-27590, https://www.rcsb.org/structure/8DO4); HeV trimer (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/emdb/EMD-27577, https://www.rcsb.org/structure/8DNR); HeV F dimer-of-trimers (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/emdb/EMD-42940); LayV F trimer (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/emdb/EMD-41825, https://www.rcsb.org/structure/8U1R); LayV F dimer-of-trimers (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/emdb/EMD-42942). Full amino acid sequences for NiV F, HeV F and LayV F can be found in Table S2.