Summary

Background

Special considerations are warranted for incarcerated mothers and their children, as both experience substantial health and social disadvantage. Children residing in custodial settings are at risk of not having access to the equivalence of education, healthcare and socialisation commensurate to that of children living in the community. This systematic review describes the existing evidence regarding underpinning theories, accessibility, and the effectiveness of custody-based Mothers and children's units (M&Cs) globally.

Methods

A systematic database search was conducted on May 1, 2023, of PsycINFO, Scopus, Sociology Ultimate and Web of Science (January 1, 2010, and May 1, 2023).

Findings

Our systematic synthesis reveals evidence gaps related to best practice guidelines that align with a human right-based approach, and evaluations of the impact of the prison environment on mothers and their children.

Interpretation

These findings support re-design of M&Cs using co-design to develop units that are evidence-based, robustly evaluated, and underpinned by the ‘best interest of the child’.

Funding

This systematic review was conducted as part of a broader review into M&C programs commissioned and funded by Corrective Services NSW, Australia (CSNSW), a division of the Department of Communities and Justice, as part of the NSW Premier's Priority to Reduce Recidivism within the Women as Parents workstream. No funding was received for this review.

Keywords: Incarcerated mothers, Human rights, Evaluation, Effectiveness, Mothers and children's units

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

Recent increases in the number of women being incarcerated present significant challenges for correctional systems. There remains a lack of successful strategies/interventions to address concerns over the incarceration of mothers and the impact of maternal incarceration on child protection, and long-term developmental and psychosocial outcomes for children. The most recent systematic review of mothers and children's units (M&Cs) was published in 2019 and included evaluations between 1998 and 2013 that focused on their effectiveness in reducing recidivism. The review identified 7 evaluation studies and the authors concluded that due to weak methodological study design their effectiveness is unknown.

Added value of this study

The current study reviews a broader range of publications (n = 37) and study designs including evaluation studies to report the underpinning theories, accessibility, effectiveness and the alignment with a human rights-based approach for mothers and their children residing in M&Cs. Studies spanned between 2010 and 2023. While most studies referenced underpinning theories, there was an absence of best practice guidelines. M&C eligibility and accessibility were variable, hindered by low usage and not systematically implemented. The systematic synthesis of 37 publications revealed the absence of best practice guidelines that align with UNCRC and Bangkok Rules; a lack of evaluation of the impact of the prison environment on mothers and their children; and a lack of transparency of operations, consistency, advocacy, monitoring and evaluation. These findings provide foundation and support a collaborative co-design for the next generation of M&C units.

Implications of all the available evidence

It is essential that M&Cs be evidence-based, are robustly evaluated and meet the needs of mothers and their children. Outcome measures must extend beyond recidivism and include health, mother/child bond and long-term impacts for mother and child post-release. In the absence best practice guidelines, a human rights-based approach underpinned by the best interest of the child is a feasible way forward to ensure equivalence of care for children. Such an approach would suggest that M&Cs must be co-designed with stakeholders and encompass a wholistic approach for mothers and children across all development stages.

Introduction

When a person is incarcerated within a criminal justice system, it not only affects them as an individual, but has broader impacts upon their families, friends and communities. The life-long punitive effects of incarceration on these broader groups, especially on children of people in prison, can be considerable,1,2 but are under-researched.3, 4, 5

The global female prison population is currently estimated to be 740,000 individuals which represents a 50% increase since 2000.6 Many women in prison are mothers. For example, in Australia, it has been reported that over a half of women in prison have dependent children in the community.7 Incarcerated mothers are a marginalised group who routinely struggle to maintain relationships with their child/ren and families, and face the prospect of losing custody of their child/ren.8 In the context of criminal justice systems, research suggests that the incarceration of a mother places her children's social, educational, and emotional development at risk.3, 4, 5 More specifically, the arrest, conviction, imprisonment, and release of a parent inequitably exposes their children to potentially traumatizing experiences with life-long consequences.3,9

To partially mitigate the impact of maternal incarceration on children, a number of countries have implemented specific initiatives allowing children and babies to reside with their mothers who are in prison. These initiatives are often delivered within Mothers' and Children's units (M&Cs) or Prison Nurseries or Mother and Baby units. Van Hout and colleagues, report that ninety-seven jurisdictions globally permit children to reside with their incarcerated mothers10 and current estimates suggest that approximately 19,000 children are living in such circumstances.10,11 The commonly stated aims of these initiatives are to reduce recidivism, improve mother-child attachment, and to break cycles of disadvantage associated with offending behaviours.12,13

Article 25.2 of the United Nation's Universal Declaration of Human Rights states that “Motherhood and childhood are entitled to special care and assistance”.14 This statement seeks to preference and safeguard the human rights of mothers and their children and as these rights are inalienable, they must be protected irrespective of whether a mother is incarcerated.

The need to protect the mothering rights of women who are imprisoned is more explicitly expressed in the United Nations Rules for the Treatment of Women Prisoners and Non-custodial Measures for Women (Bangkok Rules).15 The Bangkok Rules acknowledge the urgent need to address the specific requirements and realities of all prisoners, including women in prison, pregnant women, mothers and their child/ren. Rule 49 states, “decisions to allow children to stay with their mothers in prison shall be based on the best interests of the children” and that “children in prison with their mothers shall never be treated as prisoners.15 Such instruments provide powerful impetus behind global initiatives to improve the access of incarcerated mothers to their babies and young children through units that facilitate co-residence.

In terms of the rights of children, the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) advocates the ‘best interest principle’ whereby the child's best interest must be the primary focus in all decisions made by adults affecting the child. In the absence of best practice guidelines for M&Cs, alignment with the UNCRC Articles could be foundational. Specifically, any M&C should be informed by UNCRC defined children's rights including to be supported to have a full life (Article 6), to socialise with other children (Article 15), to be provided with access to healthcare, nutritious food, clean water and environment (Article 24), to access education that will develop the child's potential (Article 29), and to have time to relax and play (Article 31).

The impacts and suitability of correctional environments for children remains under-researched.3,4,16,17 A correctional setting is primarily focused on the delivery of a custodial sentence for the offender and does not take into account trauma-informed design for women and their children.18 This setting may not provide a sense of safety and well-being for children or offer sufficient access to resources to meet the needs of the child, nor may it be comparable to the life they would be experiencing outside a prison. A gender responsive trauma-informed approach is one model to address the cycles of disadvantage for women and their children, many of whom have experienced family violence.19

Given the current global trajectory of increasing numbers of women being incarcerated, particularly those who are mothers, and the potential for more of these women and their children to have access to M&Cs, we aimed to undertake a systematic review to investigate the existing evidence regarding underpinning theories, accessibility, and the effectiveness of custody-based programs that support mothers and their children. We further explored the extent to which such initiatives align with a human rights-based approach to the administration of justice and assert that this review contributes to the evidence base for M&Cs globally.

Methods

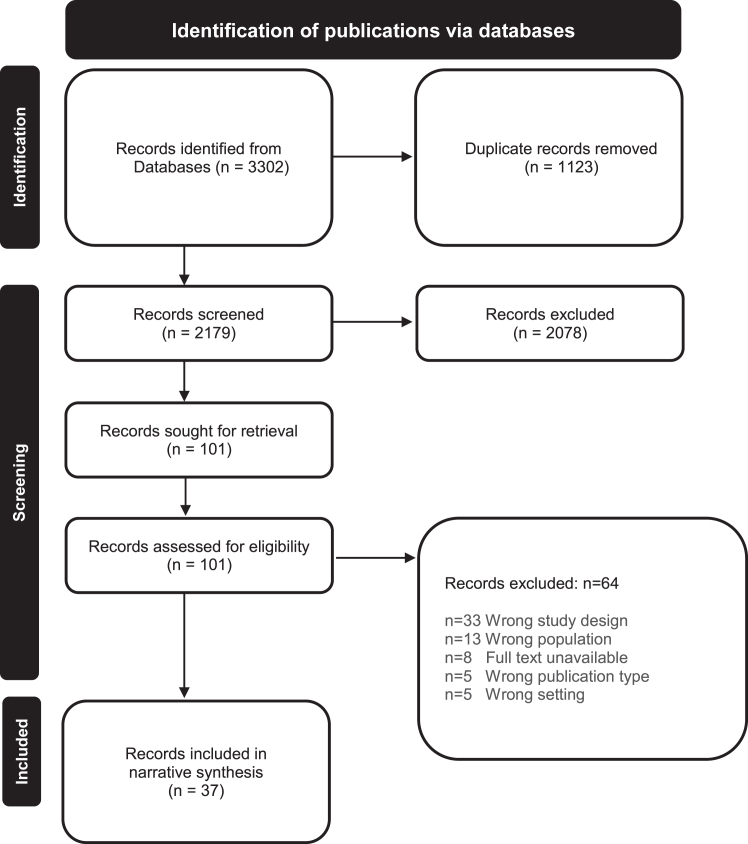

This systematic review comprised an evaluation of published qualitative and quantitative research focused on mothers in custody who reside with their children. We conducted this review according to The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA)20 and present a PRISMA Flow Diagram in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram20 [Fig. 1 reports the search and screening results, reasons for exclusion of retrieved publications, and number of publications included in the review].

Search strategy

As detailed in Supplementary Table S1, the research question was articulated with respect to Population, Context, Phenomena of Interest, Study Design and Time Frame.

Search method

In May 2023, we conducted a review of 4 electronic databases (Web of Science, PsycInfo, Scopus and Sociology Ultimate) to identify published literature relating to custody-based units that support mothers to reside with their children. The search strategy comprised four core concepts that were defined using a combination of words and truncations relating to “Mother”, “Children”, “Programs” and “Prison” (Supplementary Table S2). The following search string was used: ((mother∗) OR (mum∗ OR mom) OR (pregnan∗) AND (children∗) OR (bab∗) OR (child∗) OR (infant∗) OR (Nurser∗) AND (program∗) OR (intervention∗) OR (hous∗) OR (service∗) OR (Deliver∗) OR (Nurser∗) OR (unit) AND (prison) OR (gaol OR jail) OR (Incarcerat∗) OR (imprison∗) OR (custody) OR (detention) OR (inmate∗) OR (offend∗) OR (correction∗)). The search terms were also run in Google and Google Scholar. Additionally, we conducted a lateral search of reference lists contained in articles identified from the literature search. Predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria were used to screen articles identified via the database search (Supplementary Table S3). Articles published from 2010 onward that reported on women residing in prison with their child for any period of time were included. Articles reporting on women in prison who had contact but did not reside with them were excluded, as were grey literature, books, theses, reviews, and publications that did not include a methods section. No language restrictions were applied during our database searches. Our team used Google translate or their own language proficiency to assess the non-English publications.

Screening

All records retrieved from electronic databases, and Google and Google Scholar searches, were uploaded into Covidence,21 a Cochrane endorsed software package for conducting systematic reviews. Duplicate records were removed in Covidence and 3 reviewers (JT, TM, LE) screened the titles and abstracts of the remaining records. After screening titles and abstracts, the full texts of remaining records were obtained and screened by 2 reviewers (JT, TB). Records that met inclusion criteria progressed to data extraction. For those records that did not progress to data extraction, the reason for exclusion was recorded. Where a single study was reported in more than one publication, we extracted data and coded for each of the publications separately.

Data extraction

Data extraction was performed by four reviewers (JT, TM, LE, MR) using NVIVO 12 software.22 Following this, the research team analysed and grouped the emerging themes for narrative synthesis.

Data analysis and synthesis

Data analysis and synthesis was guided by Thomas and Harden's23 approach to thematic synthesis. This included line-by-line coding of the introduction, results and discussion sections of included publications. Summaries of the evidence were grouped into themes and narratively synthesised. Results tables are provided that present the characteristics of the included publications, the M&Cs and participants described in these publications. Each included publication was adjudged for its quality and validity using the standardized QualSyst tool for evaluating quantitative and qualitative primary research.24

Role of the funding source

This systematic review was conducted as part of a broader review into M&C programs commissioned and funded by Corrective Services NSW, Australia (CSNSW), a division of the Department of Communities and Justice, as part of the NSW Premier's Priority to Reduce Recidivism within the Women as Parents workstream. No funding was received for this review. JT, TM, MR, and LE have accessed and verified the data, and which all authors (JT, TM, MR, TB, LE and ES) were responsible for the decision to submit the manuscript.

Results

The search and selection processes to identify publication included in this review are summarised in PRISMA Flow Diagram presented in Fig. 1. Database and internet searches retrieved 3302 records (PsycINFO 872, Scopus 1188, Sociology Ultimate 204, Web of Science 978, Google 14 and Google Scholar 46) (see Fig. 1). After removal of 1123 duplicate records, the titles and abstracts of the remaining 2179 publications were screened against inclusion/exclusion criteria (Fig. 1). One hundred and one publications progressed to full-text screening from which 37 publications were retained for inclusion in the review. Of the 64 publications excluded during full-text screening (Appendix 2), 16 were excluded as they do not include a Methods section. To develop an evidence base for M&Cs, the authors contend that publications should only be included if they are valid and potentially reproducible. This can only be assessed if a Methods section is provided and, therefore, we excluded publications that did not meet this criterion.

The characteristics of the included publications are detailed in Table 1. Briefly, they reported on M&Cs operating within seventeen countries and comprised a total sample size of 2376 women and children. The date of publication ranged from 2010 to 2022 with the majority (n = 23) of publications occurring within the last 5 years.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included publications.

| Study characteristics | Number of publications | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Publication date (2010–2022) | 37 | 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59 |

| Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development Country (OECD) | 22 | 27, 28, 29,33,36,38,41, 42, 43,48, 49, 50, 51,53, 54, 55,57, 58, 59 |

| United States of America | 10 | 28, 29, 30,33,38,41,43,55,58,59 |

| France | 5 | 27,48, 49, 50,53 |

| United Kingdom | 2 | 36,54 |

| Australia | 2 | 57,60 |

| Canada | 1 | 61 |

| Chile | 1 | 42 |

| Finland | 1 | 51 |

| Non-Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development Country (OECD) | 15 | 25,26,31,32,34,35,37,39,40,44, 45, 46, 47,52,56 |

| Brazil | 5 | 31,32,35,37,44 |

| Argentina | 2 | 34,45 |

| Cameroon | 1 | 46 |

| Ethiopia | 1 | 40 |

| India | 1 | 52 |

| Iran | 1 | 25 |

| Malawi | 1 | 39 |

| Mozambique | 1 | 26 |

| South Africa | 1 | 56 |

| Zimbabwe | 1 | 47 |

| Language | ||

| English | 30 | 25,28, 29, 30, 31,33,34,36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41,43,44,46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52,54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61 |

| French | 2 | 27,53 |

| Portuguese | 3 | 26,32,35 |

| Spanish | 2 | 42,45 |

| Study design | ||

| Qualitative | 17 | 25,26,33,35,37, 38, 39, 40,46, 47, 48, 49, 50,55,56,59,60 |

| Quantitative | 17 | 27, 28, 29, 30, 31,34,36,41, 42, 43, 44, 45,52, 53, 54,58,61 |

| Mixed Methods | 3 | 32,51,57 |

| Study population | ||

| Mothers with children living in custody | 19 | 25,28,29,31,33,39, 40, 41,44, 45, 46, 47,51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56,59 |

| Mothers with children, and pregnant women living in custody | 12 | 26,30,32,34,37,38,42,43,48, 49, 50,57 |

| Children living in custody | 1 | 27 |

| Senior correctional stakeholders (commissioner of prison farms, senior correctional management staff, senior health officials, prison health staff, officers in charge) | 2 | 39,58 |

| Correctional staff directly involved in the female section of the prison | 4 | 39,46,47,51 |

| Representatives from a non-governmental organisation involved in prisons | 2 | 46,47 |

| Participants | ||

| Total participants | N = 2376 | 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61 |

| Total mothers | N = 1309 | 25,26,28,29,31, 32, 33,36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51,53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61 |

| Total pregnant women | N = 229 | 26,30,32,37,42,48,50 |

| Mothers and children (data not separated) | N = 47 | 32,35 |

| Total children | N = 699 | 25, 26, 27,29,31,33,40, 41, 42,45,48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55,58 |

| Other (correctional staff) | N = 122 | 35,39,46,47,51,57 |

| Participants' age (years) | ||

| Women's age range | 17–46 | 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33,36, 37, 38,40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46,48, 49, 50,53, 54, 55, 56,58,59 |

| Women's age not reported | 35,39,50, 51, 52,57,60,61 | |

| Children's age range | 0–17 | 25, 26, 27,29,31, 32, 33,40, 41, 42, 43,45,48, 49, 50,52,54,56,58 |

| Children's age not reported | 28,30,35, 36, 37, 38, 39,44,46,47,51,55,57,59, 60, 61 | |

| Setting | ||

| Women and children housed in separate units within a correctional centre | 23 | 25,27,29,32,33,35,37,38,40,43,45,48, 49, 50, 51,54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61 |

| Women and children housed units outside the correctional centre | 1 | 44 |

| Women and children housed with the general prison population | 5 | 26,39,46,47,52 |

| Not reported | 7 | 28,30,31,36,41,42,53 |

Note: Database searches were conducted for publications between January 1, 2010, and May 1, 2023. However, retrieved publications only ranged in publication dates between 2010 and 2022 (no relevant publications were returned for 2023).

[Table 1 reports the characteristics of the included publications].

Three key themes that emerged from thematic analysis of the included publications were: legal frameworks for best practice for M&Cs, underpinning theories cited as justification for the establishment of M&Cs, and access to M&Cs.

Guiding conventions, legislation and policies to inform best practice and principles for M&Cs

The included publications referred to a wide variety of legal instruments as providing a rationale for the introduction of M&Cs (Table 2). These included international conventions and guidelines as well as national constitutions, laws and policies. These legal instruments referenced a broad range of subject matter including human rights, alternatives to incarceration, avoiding the separation of mother and child, gender-responsiveness, prenatal and post-partum care, rights of children, and public health (e.g., HIV). The most commonly cited instrument relevant to children in a prison setting were the UNCRC25,46,51,57,62 while for women and children, the most commonly cited instrument was the Bangkok Rules.39,40,47,57,63 Both instruments stress that the individual rights of the child are separate from the rights of their mother and advocate from the perspective of the child.

Table 2.

Target population and policies.

| Target | Policy focus | Cited convention, policy, legislation, instrument | OECD | non-OECD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child | Children in corrections facilities25,35,40,46,51,56,57,60,61 |

|

4 | 5 |

| Best interest principle of the child46,51,56,57,60,61 |

|

4 | 2 | |

| Rights of the child25,35,46,51,57 |

|

2 | 3 | |

| Access to health services35 |

|

1 | ||

| Mother and child | Pregnancy and birthing25,32,38 |

|

1 | 2 |

| Breastfeeding26,31,39,47,60 |

|

1 | 4 | |

| Newborns32,44,47,62 | 4 | |||

| Fundamental human rights26,40,48 |

|

1 | 2 | |

| Alternatives to incarceration32,39,45,46,60 |

|

1 | 4 | |

| Mother and child separation policies25,27,57 |

|

2 | 1 | |

| Policies supporting M&Cs31,46,54 |

|

1 | 2 | |

| Right to health31,32,35,39 |

|

4 | ||

| Women with children | Gender-responsiveness35,55,57 |

|

2 | 1 |

| Access to health services31,32 |

|

2 | ||

| Right to express your religion, culture or spiritual preference48 |

|

1 | ||

| Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) related healthcare and prevention39,47 |

|

2 |

Note: OECD, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

[Table 2 reports all conventions, policies, legislation or legal instruments cited in included publications as relevant to the to M&Cs described in those publications and which indicate to what extent these M&Cs potentially align with a human rights-based approach].

Underpinning theories

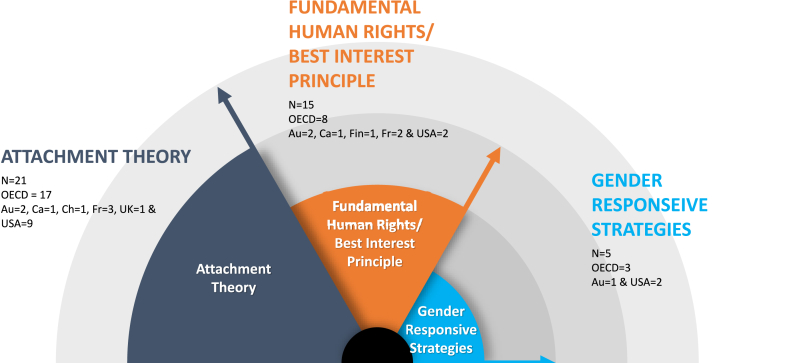

There was no consistent set of best practice principles for M&Cs referred to in the included publications. However, the majority (n = 28) described underpinning theories that formed the primary rationales for the establishment of M&Cs (Fig. 2). Three specific theories were most commonly referenced: attachment theory,25,28, 29, 30,33,38,41, 42, 43,46,48,49,51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60 fundamental human rights and the best interest principle,26,27,30, 31, 32,35,40,46, 47, 48,51,56, 57, 58,60,61 and gender responsive strategies.25,46,55,57,59

Fig. 2.

Frequency of references to underpinning theories in included publications. Au, Australia; Ca, Canada; Ch, Chile; Fin, Finland; Fr, France; UK, United Kingdom; USA, United States of America. Note: Some of the included publications referenced multiple theories and therefore the total number of references to underlying theories in this figure exceeds the number of publications included in this review [Fig. 2 details the underpinning theories reported to support M&Cs operation and the number of times each of these theories was references in the included publications].

Attachment theory

Attachment theory, first introduced by John Bowlby,25,59,64 proposes that babies and children have an inherent need to form bonds with caregivers and that these bonds influence their future attachments. Attachment theory provides a framework for M&Cs that are built upon the mother's role as the primary caregiver of her children and focuses on preserving the mother–child bond. Of the 21 publications referencing attachment theory, 20 suggested that M&Cs were beneficial to both incarcerated mothers and their children, while only one publication30 presented the counter-argument that a prison environment is not suitable for healthy parent-child attachment or bonding. The reported benefits of M&Cs in terms of attachment theory can be grouped into 3 categories:

-

a.

M&Cs enable sustained contact between mothers and their offspring and enhance the mother–infant or mother–child bond25,28,29,33,38,42,48,52,54, 55, 56,58, 59, 60, 61

-

b.

Children involved in M&Cs have improved early social, psychological, and emotional development and later life outcomes25,28,29,33,38,43,46,49,52, 53, 54,56, 57, 58, 59

-

c.

M&Cs provide mothers with a motivation to be rehabilitated and to shift away from criminal behaviour25,29,38,55,60

Fundamental human rights and the best interest principle

A number of M&Cs described in the included publications were reported to have been designed to address the fundamental human right of health needs and to support the ‘best interest principle’ under which the best interests of children take priority in all decisions relating to their care. Eight publications from OECD countries and seven from non-OECD countries discuss the importance of these principles and their link with national and international laws and Sustainable Development Goals (3, 5 and 16). Three main themes relating to fundamental human rights and the best interest principle underpinning M&Cs were identified in the included publications:

-

a.

Children have the right to have their mother act as their primary carer while mothers have the right to protect and care for their children30,32,35,48,51,57,60,61

-

b.

A child should only reside with their mother in prison if this decision is in the child's best interest, as residing in a prison setting has the potential to compromise that child's needs and rights40,46,51,56,57,60,61

-

c.

It is in the child's best interest to reside with their mother unless there is evidence to the contrary (e.g., evidence that residing with their mother may cause harm to the child)27,51

Not all included publications supported the suggestion that allowing children to reside with their mothers who were in prison was in accord with fundamental human rights and the best interest principle. The authors of six publications30,40,46,47,60,61 argued that M&Cs are a violation of human rights and that children who resided with their mothers in a prison setting were in reality ‘hidden victims’. Furthermore, the authors of two publications argued that it is crucial to ensure that children residing in M&Cs are not treated like inmates, and that all their individual social, emotional, physical, educational and healthcare needs are adequately met.40,47

Gender responsive corrective strategies

In order for criminal justice systems to be gender responsive, they must acknowledge the realities of women's lives, including the pathways they travel on their way to crime, the relationships that shape them, and the role of gender in shaping criminality.46 Five included publications discussed the importance of M&Cs as a gender responsive corrective strategy that:

Accessibility to M&C units and service provision

The published literature suggests that even in jurisdictions where M&Cs are available, accessibility for mothers is limited resulting in low rates of usage. Partial reporting of numbers were available in Australia and Canada, with yearly averages ranging between 1 and 6 mothers in Canada and in Australia, 69 children were reported to be living with their mothers in a M&C in 2017.60,61 Barriers to access for First Nations women were reported in three publications57,60,61 and given the overrepresentation of First Nations women in the prison population, this is alarming. Moreover, the impact of colonialism and racism are ever-present in many jurisdictions globally and likely to be a contributing factor to the underrepresentation of First Nations women in M&Cs. Access to healthcare, education and childcare was not consistent across M&Cs and, in most instances, did not align with Bangkok Rules or UNCRC.

Healthcare

Healthcare services were not always reported to be adequate for children in M&Cs.32,39,45,52 For mothers, two of the included publications reported suboptimal access to mental health care services.33,36 Specifically, delayed access to appropriate medications and treatment which subsequently increased the risk of the mother being separated from her child due to unit policies.33,36 Pregnancy and the post-partum period were acknowledged to be particularly vulnerable periods for women,31,38,60,61 and it was reported in one publication that women experienced inconsistent and broken communication between the hospital where prenatal visits occurred and the M&C, as well as delayed access to appropriate prenatal and postnatal care.38

Education and childcare

Access to education facilities for children such as pre-schools or creches was not commonplace25,26,45,52,56 and the provision of age-appropriate play equipment, accessible toys, and outdoor space were reported to be inadequate.25,56 Education for mothers was dependent upon the provision of childcare, however, childcare was not reported to be commonly available in M&Cs, with some prisons supporting the ‘stay at home’ mother model of care for the child,50 while other units offered childcare for mothers to attend classes.33,38 Four publications noted that mothers in M&Cs were excluded from much needed drug and alcohol rehabilitation programs, educational and vocational training, or work assignments due to having sole responsibility for caregiving.35,39,40,50

A number of publications reported that childcare support may be provided by other inmates.29,38,57 However, this was reported to have raised issues of trust for some mothers who were reluctant to allow other inmates to care for their child.57

One publication focused on an M&C operating in France reported that trained prison nannies were engaged to provide some care to children residing with their incarcerated mothers. These nannies were permitted to take the child outside the prison, including, for example, to parks and public events.48

Alignment with the ‘Best interest principle’

The incarceration of mothers may be more impactful for children due to the potential for greater instability with housing, finances, family and community connectivity.60 However, greater understanding is hindered by the lack of routinely collected data on the characteristics of children residing in M&Cs.60,61 Paytner et al. reported on the absence of reference to the ‘Best Interests of the Child’ in sentencing decisions in Canada during 2016. Such gaps give way to siloed approaches addressing the needs of children and their mothers. One example of incongruence is where the length of the mother's sentence was such that her child would exceed the age limit restriction for the unit during her incarceration, the mother and child could be separated at that time with the mother being sent back to the general prison population and the child having to return to care in the community.32,54 Another example is the impact of a mother bearing sole responsibility for their child and the challenge of having a child spend prolonged periods of time isolated in confined spaces at night with only their mother.27

A number of included publications from non-OECD countries reported that M&Cs did not have adequate resources to meet the basic needs of the children residing in the units (e.g., inadequate provision of healthcare, sleeping resources, food, clothing, physical activity options, education, and socialisation opportunities).26,31,32,34,39,47 Three publications mentioned that M&Cs did not adequately address the breastfeeding needs of mothers (e.g., inadequate nutrition, lack of breast pumps, and unavailability of safe storage for expressed breast milk).31,39,47

Performance and evaluation

Our findings suggest that evaluations for M&Cs are scarce with only eight of the thirty-seven included publications having conducted any evaluation. Where evaluations were conducted, there was a lack of data collected, particularly for children. Reporting outcomes were limited and did not consistently include both the mother and child.27,28,30,58

Of the eight publications that described evaluations of M&Cs27,28,30,36,42,45,54,65 only one study was from a non-OECD country.45 In general, reported findings indicate that there were positive outcomes for mothers involved in the programs particularly with respect to decreased depressive symptomatology and improved behaviour for mothers,36,42,54 and significant reductions in rates of recidivism.27,30 However, despite reduced recidivism, one study in France reported that post-release 42.9% of the infants were placed in foster care.27 Conversely, one study in the UK reported 70% of children who had resided in an M&C were still living with their mother at follow-up.36 While M&Cs may provide an environment that improves attachment and reduces recidivism, our findings from the included publications did not provide consensus as to their long-term benefits. These differences need to be explored further to understand where the most efficacious role of M&Cs lies. A summary of the reported findings of these evaluations is provided in Table 3.

Table 3.

Reported outcomes from evaluation studies of M&Cs.

| Evaluation |

Outcomes |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author/country | Program | Evaluation description | Outcomes for children | Outcomes for mothers |

| Huber42 (Chile) 2020 | “I feel good, my baby too” Intervention Program | Evaluated a group intervention in a ‘before and after’ study to reduce maternal depression and promote a positive bond between mother and baby, from pregnancy until the first years of the child's life.42 | Significant improvement in the post-intervention socioemotional wellbeing of children involved in the program. A decrease in children's socioemotional problems were reported across seven subscales that assess self-regulation, obedience, communication skills, adaptive functioning, autonomy, affection, and interaction with others | The participating women showed a significant decrease in depressive symptomatology in the evaluation carried out after the intervention |

| Blanchard27 (France) 2018 | Mother-child follow up program | Evaluated a mother-child follow up program in a Women's Penitentiary Centre.27 | Not reported | Mothers who lived with their infants while in prison had a lower risk of recidivism at 10 years than women in prison who did not reside with their children. |

| Carlson30 (United States of America) 2018 | Nebraska Correctional Centre for Women Nursery Program | Examined the second oldest United States of America's prison nursery program to evaluate its success with respect to recidivism within 3 years of initial offense, and the percentage of women returning to prison custody over a 20-year period.30 | Not reported | For women who completed in the nursery program, there was a 28% reduction in recidivism and a 39% reduction in return to prison custody. |

| Goshin65 (United States of America) 2014 | Preschool outcomes for children | Longitudinal study examining the long-term preschool outcomes of children who spent their first 1–18 months in a prison nursery and compared these to preschool children who were separated from their mothers because of incarceration.65 | Separation of children from their imprisoned mothers was associated with significantly worse anxiety/depression scores, even after controlling for risks in the caregiving environment. Prison nursery co-residence with developmental support confers some resilience in children who experience early maternal incarceration. | Not reported |

| Dolan36 (United Kingdom) 2013 | Mental health of mothers in 5 M&Cs | Follow-up comparative study of 5 prison M&Cs, assessed the mental health, social outcomes and needs of mothers who had been in prison with their children as infants.36 | Seventy-seven percent of children who were in prison M&Cs were being cared for by their mother at follow-up compared to 20% of those who had been separated from their mothers while she was in prison. | Women not caring for the index child at follow-up were more likely to have an interview diagnosis of personality disorder or psychotic disorder and to have been reconvicted than those who were caring for the index child at follow-up. The prevalence of depression and hazardous drinking were higher at follow-up in the former group. |

| Sleed54 (United Kingdom) 2013 | New Beginnings attachment based program | Conducted a randomized control trial to evaluate the “New Beginnings” attachment-based group intervention designed for mothers and babies in prison. Reported on parental reflective functioning, the quality of parent–infant interaction, maternal depression, and maternal representations.54 | Children of mothers in the control group who were not receiving the intervention were reported to have insecure/disorganized attachment relationships and poor outcomes. | Compared to mothers receiving the intervention, mothers in the control group (not receiving intervention) deteriorated in their level of reflective functioning and behavioural interaction with their babies over time and had a relatively poor quality of parent–infant interactions. Almost 50% of mothers in this subgroup reported clinically significant levels of depression |

| Lejarraga45 (Argentina) 2011 | Evaluation of co-habiting mothers and children of Ezeiza | Conducted a cross-sectional, comparative study in a women's prison unit to evaluate the parenting practices of mothers, physical growth, nutritional status, and social and emotional development of their cohabiting children.45 | Children cohabiting with their mothers in prison were reported to be slightly shorter and to have much higher body mass index than national reference values and to be at risk of developing emotional problems. | Mothers in prison were reported to have limited knowledge of parenting practices compared to mothers outside prison. |

| Borelli28 (United States of America) 2010 | New York State Department of Correctional Services Prison Nursery Program | Examined the association between attachment and a history of substance use, depressive symptoms, perceptions of parenting competency, and social support at the completion of the prison nursery.28 | Not reported | Incarcerated mothers had higher rates of insecure attachment compared to samples comprising low-risk mothers in the community. Compared with dismissing and secure mothers, preoccupied mothers (with unresolved state of mind such as trauma) reported higher levels of depressive symptoms, lower parenting competency, and lower satisfaction with social support and history of substance use following participation in the nursery program. |

[Table 3 details which publications included in this review described an evaluation of an M&C, how these M&Cs were evaluated, and all reported outcomes for children and mothers].

Assessment of quality

The QualSyst score range and mean for the quantitative studies was 0.6–1.0 and 0.87 and for the qualitative studies 0.5–1.0 and 0.84 (Supplementary Tables S4 and S5). Three of the 37 studies used mixed methods and hence our appraisal of study quality examined 20 quantitative and 20 qualitative components. Seventeen quantitative studies were rated ‘strong’ (overall score of ≥0.80) while 3 rated ‘adequate’ (overall score of 0.50–0.70). Fifteen qualitative studies were rated ‘strong’ (overall score of ≥0.80), 4 rated ‘good’ (overall score of 0.71–0.79), and 1 rated ‘adequate’ (overall score of 0.50–0.70).66 A subsample was appraised by a second reviewer for rigor with comparable range and means. The assessment needs to be interpreted with the knowledge that comparison groups were only reported in ten publications.27,29,30,36,38,41,43,45,54,65 Furthermore, the comparator was not consistent and included mothers separated from their children36,65 and mothers ineligible for a M&C.38

Discussion

This global review found a lack of high-quality evidence about the effectiveness of M&C in improving outcomes (child bonding, health and education and criminogenic) for mothers and their children. Of concern was the lack of policy, trauma informed design and or program logic/framing of M&Cs. The limited published research of M&Cs showed they have been setup in approximately 100 different jurisdictions10 with substantial variability across units. In the absence of international standards and or evidence-based guidelines for M&Cs, there should always be a human rights-based framing whereby the best interests of the child are preeminent and access to healthcare and education is prioritised.14,15,62

Our findings support the need for a standardised approach to M&Cs that enshrines Bangkok Rules (33.3, 42.2, 42.3, 47, 49, 51.1, 51.2) into unit design.15 These Rules are strengthened by the UNCRC (Articles 6, 15, 24, 29, 31) and both require that the best interests of the child are held paramount and that children residing in a prison setting are provided commensurate access to health, education, development and social opportunities, physical environment and safety as children living in the community.15,62

Recent increases in the number of women being incarcerated present significant challenges for correctional systems, particularly as they have historically focused on male prisoners. There remains a lack of successful strategies/interventions to address concerns over the incarceration of mothers and the impact of maternal incarceration on child protection, and long-term developmental and psychosocial outcomes for children. Correctional centres (CC) are not equipped to provide comprehensive and equivalent postpartum care,31,38 bringing forth the question of the appropriateness of pregnant women in custodial settings.67 Diversionary programs and alternatives to incarceration for pregnant women and primary caregivers of young children aligns with Bangkok Rules and warrants piloting to assess its feasibility. Similar approaches are reported in the literature and offer potential in minimising risk and harm to children of sentenced mothers.10,68

There is an intersection between trauma, health, and criminal justice systems. CC environments are traumatising, and appropriately trained staff are necessary in order to minimise potential triggers that may further traumatise women who are incarcerated. A trauma-informed approach should facilitate learning, provide empowering interactions with healthcare providers, foster relationship building, and acknowledge the historical trauma of First Nations women.19,69,70 M&Cs have an opportunity to provide a supportive space for women who have suffered trauma to heal and recover. A trauma informed care71 approach may address challenges in CC such as inadequate resourcing and restrictive operational procedures.14,26,31,32,34,39,47 These constraints may compromise timely access to healthcare for mothers and or implementation of policies and regulatory processes may impede mothers to act in accordance with advice from health professionals about their children.59 This discord between the best interest of the child and the limitation of a custodial setting presents unique challenges to mothering not seen in other settings. It provides an opportunity for CC to innovate in this area investigating the utility of co-design and trauma informed design18,71,72 to ensure the best interests of the child are met.

Such a response demands us to look beyond the custodial sentence and expand our scope to preparation for life in the community for both the mother and child. M&Cs present opportunities to provide a suite of programs related to education, parenting, employment, healthcare, and the social and emotional wellbeing of women and their children. Strategies and interventions that are holistic warrant consideration in reducing recidivism.

Currently, there is a substantial evidence gap in M&C documentation and evaluations. Reporting for M&Cs is largely absent, including the collection of baseline demographics of children who have resided in an M&C.60,61 The literature suggests that the number of places utilised in M&Cs is consistently low, with First Nation women underrepresented despite their overrepresentation in the female prison population. Such a shift acknowledges that access is essential in reducing cycles of disadvantage resultant from the criminalisation of poverty for women.

Our findings suggest there is a dearth of evidence in evaluation and assessment of the performance for M&Cs. Evaluations were often aligned with M&C key performance measure of reducing recidivism.27,30 Dodson et al. reports that reducing recidivism was the outcome measure used when evaluating M&Cs effectiveness.73 However, other findings suggest that many evaluations and previous reviews have centred on the effectiveness of parenting programs.19,74 Collectively, this suggests a broad and inclusive approach to evaluation is needed in assessing the long term feasibility of M&Cs for mothers, children and CC. To attenuate unexpected impacts of M&Cs, this review recommends a multi-stakeholder that uses a co-design approach to develop study designs that can capture the effectiveness of M&Cs and the long-term impacts post-release for mother and child. Moreover, systems with capacity to capture information on the child's development and wellbeing while residing in an M&C and into the future and appropriate resource allocation is essential.

Our thematic synthesis of the data is based on 37 publications and therefore may not cover all M&Cs in operation globally. We acknowledge the experiences may be different among mothers from OECD, non-OECD and First Nations mothers, requiring culturally-specific/appropriate/sensitive policies and approaches to reflect a difference in parenting practices among different populations. It should be noted that although our systematic search strategy provided a relatively thorough review of the available published literature since 2010, the synthesis of the findings was limited by the relatively small number of studies that were reported in peer review publications.

A human rights approach to M&Cs should be supported internationally to enshrine the best interests of the child. It should strictly adhere and align with the UNCRC and Bangkok Rules. This is a pivotal step towards improving consistency, advocacy, and transparency of M&Cs globally. The adherence and alignment with the UNCRC and Bangkok Rules should cover development of guidelines regarding design principles, eligibility criteria, admission processes, operations and monitoring and evaluation. There is a lack of baseline data of the long-term impacts of M&Cs on mothers and their children and addressing this gap in knowledge is a priority. A first step would be the development of standards to ensure all M&Cs have policies, resources and tools to monitor and evaluate existing M&Cs and their impact on the long-term social, emotional and physical health and well-being of mothers and their children. Implementing systems with capacity for such evaluations will make an important contribution towards our understanding of whether such units offer a net benefit to both mothers and their children and align with the ‘best interest principle’ of the child.

Contributors

ES conceived the study, JT and MR drafted the initial protocol. JT, TM, LE, and MR were responsible for identifying the eligible studies. JT, LE, MR, TB, and TM worked on screening, data extraction and synthesis. All authors reviewed the themes. JT and TM conducted the quality assessment. JT prepared the first draft of the manuscript, and TM, MR, TB, LE reviewed it, TM and MR continued to provide comments on revisions, with ES, providing expert review. The manuscript was critically reviewed by JT and all co-authors (TM, MR, TB, LE and ES), who read and approved the final manuscript.

Data sharing statement

There was no data generated and therefore no data available.

Declaration of interests

Nil to declare.

Acknowledgements

Corrective Services NSW, Australia.

Footnotes

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2024.102496.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

References

- 1.Moore T.G., McDonald M., Carlon L., et al. Early childhood development and the social determinants of health inequities. Health Promot Int. 2015;30:ii102–ii115. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dav031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Condry R., Smith P.S. Oxford University Press; 2018. Prisons, punishment, and the family: towards a new sociology of punishment? [Google Scholar]

- 3.Comfort M. Punishment beyond the legal offender. Ann Rev Law Soc Sci. 2007;3:271–296. doi: 10.1146/annurev.lawsocsci.3.081806.112829. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murray J., Farrington D.P. The effects of parental imprisonment on children. Crime Justice. 2008;37:133–206. doi: 10.1086/520070. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Remond M., Zeki R., Austin K., et al. Trends and issues in crime and criminal justice. 2023. Intergenerational incarceration in New South Wales: characteristics of people in prison experiencing parental imprisonment. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fair H., Walmsley R. International Centre for Prison Studies; 2021. World prison population list, 13th ed. (Oct 2021 Data) - World prison Brief. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare . Canberra AIHW; 2019. The health of Australia's prisoners 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Breuer E., Remond M., Lighton S., et al. The needs and experiences of mothers while in prison and post-release: a rapid review and thematic synthesis. Health Justice. 2021;9:31. doi: 10.1186/s40352-021-00153-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arditti J.A. Child trauma within the context of parental incarceration: a family process perspective. J Fam Theor Rev. 2012;4:181–219. doi: 10.1111/j.1756-2589.2012.00128.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van Hout M.C., Fleißner S., Klankwarth U.-B., et al. “Children in the prison nursery”: global progress in adopting the Convention on the Rights of the Child in alignment with United Nations minimum standards of care in prisons. Child Abuse Negl. 2022;134 doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2022.105829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Penal Reform International Children of incarcerated parents. https://www.penalreform.org/issues/children/what-were-doing/children-incarcerated-parents/ 2022b, accessed 16/02/23 2023.

- 12.Shlonsky A., Rose D., Harris J., et al. Corrections Victoria; 2016. Literature review of prison-based mothers and children programs: final Report. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnson J. 2022. Mothering within a prison nursery–a review of the literature; pp. 401–412. [Google Scholar]

- 14.United Nations General Assembly . United Nations General Assembly.; New York: 1948. The universal declaration of human rights (UDHR) [Google Scholar]

- 15.United Nations General Assembly . 2010. United Nations Rules for the treatment of women prisoners and non-custodial measures for women offenders (the Bangkok Rules) [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brennan S. Canada's mother-child program: examining its emergence, usage, and current state. Canadian Graduate J Sociol Criminol. 2014;3:11–33. doi: 10.15353/cgjsc.v3i1.3757. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kanaboshi N., Anderson J.F., Sira N. Constitutional rights of infants and toddlers to have opportunities to form secure attachment with incarcerated mothers: importance of prison nurseries. Int J Soc Sci Stud. 2017;5:55. doi: 10.11114/ijsss.v5i2.2160. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jewkes Y., Jordan M., Wright S., et al. Designing ‘healthy’prisons for women: incorporating trauma-informed care and practice (TICP) into prison planning and design. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16:3818. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16203818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lovell B.J., Steen M.P., Brown A.E., et al. The voices of incarcerated women at the forefront of parenting program development: a trauma-informed approach to education. Health Justice. 2022;10:1–16. doi: 10.1186/s40352-022-00185-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Page M.J., McKenzie J.E., Bossuyt P.M., et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Int J Surg. 2021;88 doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2021.105906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Veritas Health Innovation . 2023. Covidence systematic review software.www.covidence.org Melbourne, Australia. [Google Scholar]

- 22.QSR international NVivo qualitative data analysis software. 13 ed. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thomas J., Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8:1–10. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-8-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kmet L.M., Cook L.S., Lee R.C. 2004. Standard quality assessment criteria for evaluating primary research papers from a variety of fields. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Anaraki N.R., Boostani D. Mother-child interaction: a qualitative investigation of imprisoned mothers. Qual Quantity. 2014;48:2447–2461. doi: 10.1007/s11135-013-9900-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Arinde E.L., Mendonça M.H. Política prisional e garantia de atenção integral à saúde da criança que coabita com mãe privada de liberdade, Moçambique. Saúde Debate. 2019;43:43–53. doi: 10.1590/0103-1104201912003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blanchard A., Bebin L., Leroux S., et al. Infants living with their mothers in the Rennes, France, prison for women between 1998 and 2013. Facts and perspectives. Arch Pediatr. 2018;25:28–34. doi: 10.1016/j.arcped.2017.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Borelli J.L., Goshin L., Joestl S., et al. Attachment organization in a sample of incarcerated mothers: distribution of classifications and associations with substance abuse history, depressive symptoms, perceptions of parenting competency and social support. Attach Hum Dev. 2010;12:355–374. doi: 10.1080/14616730903416971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Byrne M.W., Goshin L.S., Joestl S.S. Intergenerational transmission of attachment for infants raised in a prison nursery. Attach Hum Dev. 2010;12:375–393. doi: 10.1080/14616730903417011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carlson J.R. Prison nurseries: a way to reduce recidivism. Prison J. 2018;98:760–775. doi: 10.1177/0032885518812694. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cavalcanti A.L., Cavalcanti Costa G.M., de Matos Celino S.D., et al. Born in chains: perceptions of Brazilian mothers deprived of freedom about breastfeeding. Pesqui Bras Odontopediatria Clin Integr. 2018;18(1):1–11. doi: 10.4034/pboci.2018.181.69. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chaves L.H., de Araújo I.C.A. Pregnancy and maternity in prison: healthcare from the perspective of women imprisoned in a maternal and child unit. Physis. 2020;30:1–22. doi: 10.1590/S0103-73312020300112. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Condon M.-C. Early relational health: infants' experiences living with their incarcerated mothers. Smith Coll Stud Soc Work. 2017;87:5–25. doi: 10.1080/00377317.2017.1246218. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Di Iorio S., Ortale M., Querejeta M., et al. Growth and development of children living in incarceration environments of the province of Buenos Aires, Argentina. Rev Esp Sanid Penit. 2019;21:118–125. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Diuana V., Corrêa M.C.D.V., Ventura M. Mulheres nas prisões brasileiras: tensões entre a ordem disciplinar punitiva e as prescrições da maternidade. Physis Rev Saúde Coletiva. 2017;27:727–747. doi: 10.1590/s0103-73312017000300018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dolan R.M., Birmingham L., Mullee M., et al. The mental health of imprisoned mothers of young children: a follow-up study. J Forensic Psychiatr Psychol. 2013;24:421–439. doi: 10.1080/14789949.2013.818161. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ferreira A.C.R., Rouberte E.S.C., Nogueira D.M.C., et al. Maternal care in a prison environment: representation by story drawing. Rev Enferm. 2021;29(1):e51211. doi: 10.12957/reuerj.2021.51211. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fritz S., Whiteacre K. Prison nurseries: experiences of incarcerated women during pregnancy. J Offender Rehabil. 2016;55:1–20. doi: 10.1080/10509674.2015.1107001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gadama L., Thakwalakwa C., Mula C., et al. 'Prison facilities were not built with a woman in mind': an exploratory multi-stakeholder study on women's situation in Malawi prisons. Int J Prison Health. 2020;16:303–318. doi: 10.1108/ijph-12-2019-0069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gobena E.B., Hean S.C.P.D. The experience of incarcerated mothers living in a correctional institution with their children in Ethiopia. J Comp Soc Work. 2019;14:30–54. doi: 10.31265/jcsw.v14.i2.247. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Goshin L.S., Byrne M.W. Predictors of post-release research retention and subsequent reenrollment for women recruited while incarcerated. Res Nurs Health. 2012;35:94–104. doi: 10.1002/nur.21451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Huber M.O., Venegas M.E., Contreras C.M. Group intervention for imprisoned mother-infant dyads: effects on mother's depression and on children's development. Revista Ces Psicologia. 2020;13:222–238. doi: 10.21615/CESP.13.3.13. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kearney J.A., Byrne M.W. Reflective functioning in criminal justice involved women enrolled in a mother/baby co-residence prison intervention program. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2018;32:517–523. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2018.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Leal M.C., Ayres B.V.S., Esteves-Pereira A.P., et al. Birth in prison: pregnancy and birth behind bars in Brazil. Cien Saude Colet. 2016;21:2061–2070. doi: 10.1590/1413-81232015217.02592016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lejarraga H., Berardi C., Ortale S., et al. Growth, development, social integration and parenting practices on children living with their mothers in prison. Arch Argent Pediatr. 2011;109:485–491. doi: 10.5546/aap.2011.485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Linonge-Fontebo H.N., Rabe M. Mothers in Cameroonian prisons: pregnancy, childbearing and caring for young children. Afr Stud. 2015;74:290–309. doi: 10.1080/00020184.2015.1068000. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mhlanga-Gunda R., Kewley S., Chivandikwa N., et al. Prison conditions and standards of health care for women and their children incarcerated in Zimbabwean prisons. Int J Prisoner Health. 2020;16:319–336. doi: 10.1108/IJPH-11-2019-0063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ogrizek A., Lachal J., Moro M.R. The process of becoming a mother in French prison nurseries: a qualitative study. Matern Child Health J. 2022;26:367–380. doi: 10.1007/s10995-021-03254-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ogrizek A., Moro M.R., Lachal J. Incarcerated mothers' views of their children's experience: a qualitative study in French nurseries. Child Care Health Dev. 2021;47:851–858. doi: 10.1111/cch.12896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ogrizek A., Radjack R., Moro M.R., et al. The cultural hybridization of mothering in French prison nurseries: a qualitative study. Cult Med Psychiatry. 2022;47(2):422–442. doi: 10.1007/s11013-022-09782-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pösö T., Enroos R., Vierula T. Children residing in prison with their parents: an example of institutional invisibility. Prison J. 2010;90:516–533. doi: 10.1177/0032885510382227. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sarkar S., Gupta S. Life of children in prison: the innocent victims of mothers’ imprisonment. J Nurs Health Sci. 2015;4(5 Ver. I):86–89. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Signori A., Sadoun-Haillard C., Bailly L., et al. Impact de la médiation animale sur le caregiving de mères détenues avec leur bébé Une étude pilote = the impact of animal-assisted therapy on the caregiving of mothers incarcerated with their infant. Devenir. 2020;32:163–179. doi: 10.3917/dev.203.0163. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sleed M., Baradon T., Fonagy P. New Beginnings for mothers and babies in prison: a cluster randomized controlled trial. Attach Hum Dev. 2013;15:349–367. doi: 10.1080/14616734.2013.782651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tuxhorn R. Critical Criminology; 2021. "I've got something to live for now": a study of prison nursery mothers. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.van Schalkwyk M., Cronje C., Thompson K., et al. An occupational perspective on infants behind bars. J Occup Sci. 2019;26:426–441. doi: 10.1080/14427591.2019.1617926. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Walker J.R., Baldry E., Sullivan E.A. Residential programmes for mothers and children in prison: key themes and concepts. Criminol Crim Justice. 2021;21:21–39. doi: 10.1177/1748895819848814. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Goshin L.S., Byrne M.W., Blanchard-Lewis B. Preschool outcomes of children who lived as infants in a prison nursery. Prison J. 2014;94:139–158. doi: 10.1177/0032885514524692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Luther Kate G.J. Restricted motherhood: parenting in a prison nursery. Int J Sociol Fam. 2011;37:85–103. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sapkota D., Dennison S., Allen J., et al. Navigating pregnancy and early motherhood in prison: a thematic analysis of mothers' experiences. Health Justice. 2022;10:32. doi: 10.1186/s40352-022-00196-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Paynter M., Martin-Misener R., Iftene A., et al. The correctional services Canada institutional mother child program: a look at the numbers. Prison J. 2022;102:610–625. doi: 10.1177/00328855221121272. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.United Nations Treaty Collection . 1989. Convention on the rights of the child [UNCRC] [Google Scholar]

- 63.United Nations General Assembly . In: Nations U., editor. 2010. United Nations Rules for the treatment of women prisoners and non-custodial measures for women offenders (the Bangkok Rules) [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bowlby J., May D.S., Solomon M. Lifespan Learning Institute; Los Angeles, CA: 1989. Attachment theory. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Goshin L.S., Byrne M.W., Henninger A.M. Recidivism after release from a prison nursery program. Public Health Nurs. 2014;31:109–117. doi: 10.1111/phn.12072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Papatzikis E., Agapaki M., Selvan R.N., et al. Quality standards and recommendations for research in music and neuroplasticity. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2023;1520:20–33. doi: 10.1111/nyas.14944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bard E., Knight M., Plugge E. Perinatal health care services for imprisoned pregnant women and associated outcomes: a systematic review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016;16:1–19. doi: 10.1186/s12884-016-1080-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lai C., Rossi L.E., Scicchitano F., et al. Motherhood in alternative detention conditions: a preliminary case-control study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19:6000. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19106000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mollard E., Brage Hudson D. Nurse-led trauma-informed correctional care for women. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2016;52:224–230. doi: 10.1111/ppc.12122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Poehlmann-Tynan J., Turney K. A developmental perspective on children with incarcerated parents. Child Dev Perspect. 2021;15:3–11. doi: 10.1111/cdep.12392. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Owen C., Crane J. Trauma-informed design of supported housing: a scoping review through the lens of neuroscience. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19 doi: 10.3390/ijerph192114279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Petrillo M. ‘We've all got a big story’: experiences of a trauma-informed intervention in prison. Howard J Crime Justice. 2021;60:232–250. doi: 10.1111/hojo.12408. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Dodson K.D., Cabage L.N., McMillan S.M. Mothering behind bars: evaluating the effectiveness of prison nursery programs on recidivism reduction. Prison J. 2019;99:572–592. doi: 10.1177/0032885519875037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Troy V., McPherson K.E., Emslie C., et al. The feasibility, appropriateness, meaningfulness, and effectiveness of parenting and family support programs delivered in the criminal justice system: a systematic review. J Child Fam Stud. 2018;27:1732–1747. doi: 10.1007/s10826-018-1034-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.