Abstract

Tumours of the sternum can be either primary or secondary with malignancy being the most common etiology. Wide local excision of these tumours results in a midline defect which pose a unique challenge for reconstruction. As limited data on the management of these tumours exists in the literature, we hereby report 14 consecutive patients who were treated at our institute between January 2009 to December 2020. Most of them were malignant with majority of them, 11 (78%) patients, with manubrial involvement requiring partial sternectomy. Overall, the average defect size was 75 cm2. Reconstruction of the chest wall defect was done using a semi-rigid fixation: mesh and suture stabilization in 3 (21%) or suture stabilization in 7 (50%) and without mesh or suture stabilization in 3 (21%) patients. Rigid fixation with polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) was done for one patient (7%). Pectoralis major advancement flap was most commonly used for soft tissue reconstruction with flap necrosis noted in one patient (7%). There was no peri-operative mortality and one patient required prolonged post-operative ventilation. On a median follow-up of 37.5 months, one patient (7%) had a recurrence. Sternal defects after surgical resection reconstructed with semi-rigid fixation and suture stabilization render acceptable post-operative outcomes.

Keywords: Manubrium, Chondrosarcoma, Surgical mesh, Reconstruction, Plastic surgery

Introduction

Sternal tumours are quite rarely encountered in thoracic surgery practice. They can be either primary or secondary. The real incidence of sternal tumours had not been clearly established [1]. It was noted to be 22% of the chest wall tumours in a large series published by Pairolero et al. and all of them were malignant [2]. Chondrosarcoma is the most common malignant tumour of the sternum. Surgical resection of the tumour necessitates full-thickness excision of the sternum resulting in midline and anterolateral defects which can alter the respiratory mechanics of either of the hemi-thoraces. Sternectomy can be total or partial. Reconstruction involves providing skeletal fixation as well as soft tissue cover for the defect. Historically, autologous materials like fascia lata and rib grafts were used. Subsequently, polypropylene mesh, polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) mesh, and methyl methacrylate were the commonly used materials for fixation. Recently, titanium-based osteogenesis systems, bone grafts, and matrices are being advocated for large defects [3]. With advancements in intensive care, peri-operative mortality has been greatly reduced. However, surgical site infection requiring implant exit is a dreaded complication. In this study, we report the outcomes of a series of patients who underwent sternal tumour excision and reconstruction using predominantly semi-rigid fixation and soft tissue cover.

Methods

From January 2009 to December 2020, we retrospectively reviewed the electronic files of patients who underwent sternal tumour excision for primary or secondary neoplasm after getting the approval of the institutional review board (IRB Min No. 14730 dated 29.6.22). Informed consent for publication was obtained from all patients before the surgery.

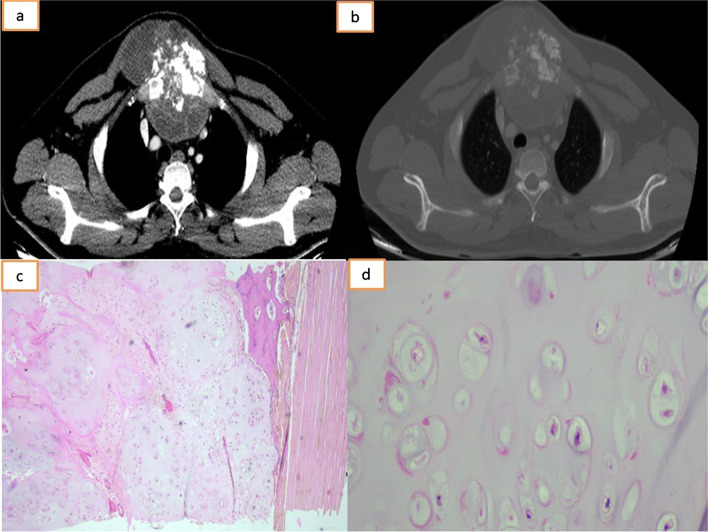

All patients were evaluated with a chest radiograph and a computed tomography (CT) (Fig. 1a, b). Metastatic workup was done either with positron emission tomography-CT (PET-CT) or bone scintigraphy. A pre-operative biopsy was obtained (Fig. 1c, d). All sarcomas were discussed in the multi-disciplinary meeting involving the medical oncologists and radiation therapists. Metastatic thyroid tumours were discussed with the endocrinologist and the nuclear medicine specialists before planning for excision. Adjuvant chemotherapy, radiation therapy and radioactive ablation were based on the final histopathological diagnosis. Excision and rigid or semi-rigid reconstruction of the sternal defect was performed by the thoracic surgical team while soft tissue reconstruction was performed by the plastic surgeons. The en bloc specimen was sent for histopathological examination. Post-operative complications were enumerated based on the Thoracic Morbidity and Mortality system of classification [4].

Fig. 1.

Computed tomography of the thorax: mediastinal (a) and bone window (b) showing lytic lesion involving the manubrium with a large exophytic soft tissue component and areas of calcification. c Photomicrograph displaying lobules of mildly cellular cartilage with minimal to mild atypia, H&E, 4×. d Photomicrograph displaying chondrocytes with minimal to mild atypia, H&E, 20×

Surgical technique

Skin incision would include the tumour and the previous biopsy scar site (Fig. 2a). The aim was to give at least a 2-cm margin for primary malignant sternal tumours (Fig. 2b) with the removal of the adjunct costochondral junction and ribs if necessary. Rigid or non-rigid reconstruction of the chest wall was based on the location of the defect. Manubrial defects were closed with a polypropylene mesh (Fig. 2c) to provide some rigidity while defects involving the body of the sternum needed only soft tissue coverage. Soft tissue cover was usually done using a pectoralis major advancement flap. Larger defects were closed with latissimus dorsi flap. If the sternoclavicular junction was resected, stability of the anterior chest wall was maintained by an interclavicular stitch (ICS) using 0-polypropylene sutures. Two sets of 1.5-mm holes were drilled in the resected edges of the clavicle. A polypropylene suture was passed through the holes and fastened to ensure adequate tension (Fig. 2d). Post-operatively, patients were started on an opioid infusion (patient-controlled) supplemented by non-steroidal analgesics. All patients were advised bilateral shoulder sling for 3 weeks followed by graded physiotherapy.

Fig. 2.

a Clinical photograph of a patient with a sternal tumour involving the upper sternum. b Clinical photograph of the same patient, after partial resection of the sternum. c Clinical photograph of the same patient showing reconstruction of the defect with polypropylene mesh. d Pictorial depiction of the interclavicular stitch

Results

From January 2009 to December 2021, 14 patients (11 males, 78%) underwent surgical excision for primary (10 patients, 75%) or metastatic (4 patients, 25%) sternal tumours. Of the primary sternal tumours, 6 (60%) were malignant and 4 (40%) were benign. Overall, 10/14 (71%) of patients in our study were malignant tumours. The majority of the tumours involved the manubrium (11 patients, 78%). The body of the sternum and xiphoid was involved in 2 patients (14%) and the whole sternum was involved in one patient (7%). The patient demographics and pre-operative data are tabulated in Table 1. Of the sternectomies performed, one (7%) was a total sternectomy and 13 (93%) were partial sternectomies. Excision of the sternoclavicular joint and medial third of the clavicle was required in 10 (71%) patients. In one patient, the resection extended to the removal of the right pectoralis muscle. Bilateral internal mammary artery was preserved in 11 patients (78%).

Table 1.

Demographic and pre-operative data

| Demographic data | Number |

|---|---|

| Age in years (mean ± SD) | 37 ± 13.87 |

| Sex | |

| Male (n and %) | 11 (78%) |

| Comorbidities | |

| Diabetes mellitus (n, %) | 2 (14%) |

| Hypertension (n, %) | 1 (7%) |

| COPD (n, %) | 1 (7%) |

| Histological type of tumour (n, %) | |

| Primary malignant | 6 (42%) |

| Benign | 4 (28%) |

| Metastatic | 4 (28%) |

| Location of tumour (n, %) | |

| Manubrium | 11 (78%) |

| Body of the sternum | 2 (14%) |

| Whole sternum | 1 (7%) |

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

Skeletal and soft tissue reconstruction used in our series are tabulated in Table 2. Reconstruction with dual mesh and polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) was done in one patient who underwent a total sternectomy. Among the patients who underwent partial sternectomy, polypropylene mesh with ICS was used in 3 (21%), and ICS without mesh was used in 7 (50%) patients and without skeletal reconstruction in 3 (21%). Soft tissue reconstruction was achieved with a pectoralis major (PM) advancement flap in 12 (86%) patients, and 2 (14%) patients required a latissimus dorsi (LD) myocutaneous flap.

Table 2.

Details of histopathology, resection, reconstruction, margins, and recurrences

| No. | Age/sex | Histopathology | Site of the tumour | Type of resection | Size of the defect (cm2) | Reconstruction | Margin status | Local recurrence (Y/N) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Skeletal | Soft tissue | ||||||||

| 1 | 27/f | Fibromatosis | Body of sternum | Partial | 110 | - | PM flap | Negative | N |

| 2 | 39/m | Spindle cell sarcoma | Whole sternum | Total | 96 | Rigid fixation | PM flap | Negative | N |

| 3 | 26/m | Chondrosarcoma | Manubrium | Partial | 42 | Mesh + ICS | PM flap | Negative | N |

| 4 | 23/m | Benign angiomatous lesion | Manubrium | Partial | 68 | Mesh + ICS | PM flap | Negative | N |

| 5 | 15/f | Enchondroma | Manubrium | Partial | 27.5 | Mesh + ICS | PM flap | Negative | N |

| 6 | 57/m | Metastatic renal cell carcinoma | Manubrium | Partial | 45 | ICS | PM flap | Negative | N |

| 7 | 49/m | Sarcomatoid carcinoma | Manubrium | Partial | 72 | ICS | LD flap | Negative | N |

| 8 | 47/m | Metastatic thyroid carcinoma | Manubrium | Partial | 81 | - | PM flap | Negative | N |

| 9 | 42/m | Dermatofibrosarcoma | Body of sternum | Partial | 165 | - | LD flap | Negative | N |

| 10 | 50/m | Metastatic thyroid carcinoma | Manubrium | Partial | 90 | ICS | PM flap | Positive | Y* |

| 11 | 35/f | Chondrosarcoma | Manubrium | Partial | 50 | ICS | PM flap | Negative | N |

| 12 | 21/m | Chondroblastoma | Manubrium | Partial | 56 | ICS | PM flap | Negative | N |

| 13 | 27/m | Chondrosarcoma | Manubrium | Partial | 110 | ICS | PM flap | Negative | N |

| 14 | 57/m | Metastatic thyroid carcinoma | Manubrium | Partial | 42 | ICS | PM flap | Negative | N |

ICS, interclavicular stitch; PM, pectoralis major; LD, latissimus dorsi

Rigid fixation—methyl methacrylate sandwich with Prolene mesh

*The only recurrence in a patient with positive margins

One patient with a LD flap was noted to have flap necrosis and he was re-operated, and the defect was reconstructed with PM myocutaneous flap. One patient had superficial skin necrosis with infection, which was managed conservatively. The average defect size was 75 cm2. The average operation time was 177 ± 74 min. The average blood loss was 264 mL.

Margins were positive in one patient (7%) who underwent resection for a metastatic thyroid carcinoma, who subsequently presented with recurrence after 4 years. The median follow-up was 37.5 months with no recurrence for primary sternal tumours. The operative and post-operative data are tabulated in Table 3.

Table 3.

Operative and post-operative details

| Operative and post-operative data | Number |

|---|---|

| Type of resection (n, %) | |

| Total sternectomy | 1 (7%) |

| Partial sternectomy | 13 (93%) |

| Defect size (mean ± SD) | 75 ± 20 cm2 |

| Status of Internal mammary artery (n, %) | |

| Bilateral preserved | 11 (78%) |

| None | 3 (21%) |

| Type of reconstruction | |

| Skeletal | |

| Sandwich | 1 (7%) |

| Mesh + suture stabilization | 3 (21%) |

| Suture stabilization | 7 (50%) |

| None | 3 (21%) |

| Soft tissue | |

| PM advancement flap | 12 (86%) |

| LD flap | 2 (14%) |

| Operation time (min) | 177 ± 74 min |

| Blood loss | 264 mL |

| ICU stay in days (mean ± SD) (range) | 1.2 ± 1.1 days (1 to 5 days) |

| Hospital stay in days (mean ± SD) (range) | 12 ± 9.5 days (4 to 40 days) |

| 30-day mortality | Nil |

| Post op complication | |

| Pneumonia | 0 |

| Fibrillation | 0 |

| Wound infection | 1 (7%) |

| Re-exploration | 1 (7%) |

| Respiratory failure | 1 (7%) |

| Flap failure | 1 (7%) |

| Duration of follow-up (median) | 37.5 months |

| Local recurrence | 1 (7%) |

Discussion

Tumours of the sternum represent about 1% of all primary bone tumours. They are to be considered malignant until proven otherwise [5]. In our series, 71% of the tumours were malignant. The majority of the primary malignant tumours were chondrosarcoma which are not chemo-sensitive and necessitated surgical excision with a bone margin of 2 to 5 cm and soft tissue margin of 2 to 5 cm [6–8]. Local recurrence can be as high as 73% (vs 4% if margins are negative) in patients with intralesional excision [9]. Despite best efforts, incomplete resection can result in recurrences. Margin positivity can be as high as 27% as reported in the literature [9]. In our series, all patients who underwent resection for primary sternal tumour had negative margins and no recurrence at a median follow-up of 37.5 months. One patient who underwent resection for a secondary sternal tumour (metastatic thyroid carcinoma) had positive margins. He received adjuvant radiation therapy. He had a local recurrence on follow-up at 4 years.

Aggressive resection of the sternum to attain negative margin results in midline defects which are challenging for reconstruction. Adequate reconstruction should adhere to the concept of bio-mimesis and chest wall stability to prevent paradoxical motion and soft tissue cover protecting the mediastinal structures [8, 10]. It has been a subject of debate as regards to which wounds require reconstruction. Most surgeons would agree with reconstruction if the lesser dimension of the defect is more than 5 cm in the anterolateral chest wall to prevent lung herniation and respiratory compromise. Chest wall stability can be re-established by rigid or semi-rigid or non-rigid fixation. Rigid fixation involves using the ‘sandwich’ technique where methyl methacrylate is sandwiched between two layers of polypropylene mesh. Other options like titanium plate and homograft iliac bone are usually reserved for defects after recurrent excision or radiation therapy. In semi-rigid fixation, polypropylene mesh or PTFE mesh is spread across the defect anchored to the surrounding sternum and ribs. The choice of skeletal fixation depends on the location of the tumour and the size of the defect; however, the extent of resection which necessitates a rigid vs semi-rigid fixation is not available in the literature.

Traditionally, it was believed that rigid fixation restores chest wall integrity with preserved lung functions, thereby reducing pulmonary complications. The data in the existing body of literature on this subject is quite heterogenous, making it challenging to draw definitive conclusions. A study conducted on the effect of sternal resection and reconstruction (30%—with mesh vs 60%—without mesh) on pulmonary function revealed no significant difference in the total lung capacity and functional residual capacity [11]. Hanna et al. assessed patients in two groups based on the size of the defect (< 60 cm2 vs > 60 cm2) and the type of reconstruction. There was no difference in pulmonary complications in the group with defect size less than 60 cm2 irrespective of the type of reconstruction (with or without mesh). Among those with more than 60 cm2, decreased risk of prolonged post-operative ventilation was seen in patients reconstructed with mesh; however, there was no difference in activities of daily living or oxygen requirement at home [12]. Deschamps et al. did not find any difference in the post-operative outcomes in their study comparing PTFE vs polypropylene mesh for reconstruction [13].

Rigid reconstruction of large anterolateral defects with the Mersilene-methyl methacrylate-Mersilene sandwich resulted in preserved forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) and shoulder girdle function as reported by Lardinois et al. [14]. Resection of more than 4 ribs was considered to be large defects with no specific dimension of size taken into account. As all the patients underwent rigid reconstruction in their study, they could not make any comparison with semi-rigid reconstruction. In another study comparing rigid and semi-rigid reconstruction, respiratory complications were comparable. On multivariate analysis, they reported age, size of the defect, and associated lung resection to be risk factors for complications [15]. In a study by MD Anderson Cancer Centre, prosthetic material was used in 82% of their cases with similar outcomes between rigid and semi-rigid fixation (rigid—37%; semi-rigid—5%) [16]. A disadvantage of fixation with prosthetic material is the wound complications which were significantly higher with rigid fixation [15]. Tsukushi et al. have published a series of patients undergoing chest wall resection managed with semi-rigid fixation using suture stabilization irrespective of the extent of sternal resection or the number of ribs resected with good post-operative outcomes and fewer complications [17].

We adopted a similar approach to skeletal reconstruction in our series with 11 (77%) patients having suture or mesh stabilization after partial sternectomy except for one patient where we did rigid reconstruction in view of a total sternal resection. Among patients with partial sternal resection involving excision of the manubrium, we prefer to reconstruct using a polypropylene mesh with ICS for larger defects and only ICS for smaller defects. Polypropylene mesh is our preferred choice due to its ease of handling and effective integration, alongside its radiolucent properties. Notably, it mitigates the occurrence of chronic pain which is observed in patients undergoing rigid reconstruction. Only soft tissue reconstruction with muscle flaps were used for reconstructing defects involving the body of the sternum in 2 (14%) patients. In one patient with a metastatic thyroid malignancy where the manubrium was excised with clavicular heads, fixation with mesh or ICS was not done. This was a breach in protocol. The patient was managed with only soft tissue cover and did well in the post-operative period with shoulder slings alone which corroborated with the study by Hanna et al. [12]. Although the patient did well, we did not follow this approach of non-skeletal fixation in other patients, as not fixing the clavicle did not make sense. Suture stabilization of the medial ends of the clavicle prevents outward movement of the clavicle and thereby provides an adequate framework to support accessory muscles of respiration such as sternocleidomastoid and PM. As the clavicle also plays a role in supporting the pectoral girdle, stabilization of the clavicle facilitates movement at the shoulder joint. Mesh implantation results in inflammatory response with accumulation of fibroblasts promoting tissue ingrowth and collagen synthesis, eventually leading to the formation of a scar plate which aids in chest wall stability. In a study reported by Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Centre, the average size of defects closed with rigid fixation was 123 cm2 [15], whereas Mayo Clinic has reported closure with a semi-rigid fixation for defect size of 148 cm2 [18] with comparable results. In our study, the average defect size was 75 cm2 which was lower probably due to the small built of Indian patients. One patient required prolonged ventilation due to paradoxical breathing which was comparable to other studies [15, 16].

PM advancement flap was the most common flap used in our series. PM not only provides soft tissue cover but is also functional, providing intrinsic resilience and preventing paradoxical motion of the chest wall. This resilience is accentuated in the immediate post-operative period due to oedema of the muscle thereby facilitating early recovery [19]. PM has two distinct parts: the clavicular portion, which constitutes the later 1/3rd, and the sternocostal portion, the medial 2/3rd of the muscle. The sternal portion has a dual blood supply, receiving branches from the thoraco-acromial artery and the perforator branches of the internal mammary artery [20, 21]. Internal mammary artery (IMA) preservation has been of considerable interest as it influences the outcomes. In our series, IMA was preserved bilaterally in 11 patients (78%) compared to 37% in another large study [18]. PM advance flap was used in 12 patients (86%) of the cases providing adequate soft tissue cover with no evidence of flap necrosis or wound infection. One (7%) patient with an LD flap had flap necrosis requiring reoperation which was comparable to other studies in the literature [13, 15, 16]. Overall, surgical site complication was noted to be 21% similar to 23% in a large single-centre study with comparable re-exploration rates [16, 18]. We had one re-exploration due to bleeding (grade IIIb) and one patient requiring prolonged ventilation (grade IV) based on the Thoracic Morbidity and Mortality system of classification [4] with intensive care unit (ICU) stay comparable to a previous report [6].

Limitations

The sample size is relatively small and the retrospective nature of the data prevents concluding statistical significance. Post-operative pulmonary function tests are not available.

Conclusion

Surgical resection of the sternum with the reconstruction of the chest wall with suture or mesh stabilization technique with appropriate soft tissue cover renders good post-operative outcomes and good freedom from recurrence.

Authors contribution

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. The manuscript was written by Raj Kumar Joel and Santhosh Regini Benjamin. Data collection was done by Aamir Mohammad, Mallampati Sameer, and Nishok David. The surgeries were done by Birla Roy Gnanamuthu, Santhosh Regini Benjamin, and Vinay Murahari Rao. The histopathology reporting was done by Thomas Alex Kodiatte. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

None.

Declarations

Ethics approval

The approval of the institutional review board was obtained.

Informed consent

Written consent for studies and publication were obtained from the patients prior to the surgery.

Human and animal rights

The study has been performed in accordance with the ethical standards as laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Conflict of interest

There was no conflict of interest in this study.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Kozak K, Łochowski MP, Białas A, Rusinek M, Kozak J. Surgical treatment of tumours of the sternum - 10 years’ experience. Kardiochir Torakochirurgia Pol. 2016;13:213–216. doi: 10.5114/kitp.2016.62608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pairolero PC, Arnold PG. Chest wall tumors. Experience with 100 consecutive patients. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1985;90:367–372. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5223(19)38591-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Novoa NM, Alcaide JLA, Hernández MTG, Fuentes MG, Goñi E, Lopez MFJ. Chest wall—reconstruction: yesterday, today and the future. Shanghai. Chest. 2019;3:15.

- 4.Seely AJE, Ivanovic J, Threader J, Al-Hussaini A, Al-Shehab D, Ramsay T, et al. Systematic classification of morbidity and mortality after thoracic surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2010;90:936–942. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2010.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martini N, Huvos AG, Burt ME, Heelan RT, Bains MS, McCormack PM, et al. Predictors of survival in malignant tumors of the sternum. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1996;111:96–105. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5223(96)70405-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bongiolatti S, Voltolini L, Borgianni S, Borrelli R, Innocenti M, Menichini G, et al. Short and long-term results of sternectomy for sternal tumours. J Thorac Dis. 2017;9:4336–4346. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2017.10.94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.David EA, Marshall MB. Review of chest wall tumors: a diagnostic, therapeutic, and reconstructive challenge. Semin Plast Surg. 2011;25:16–24. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1275167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rocco G. Chest wall resection and reconstruction according to the principles of biomimesis. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2011;23:307–313. doi: 10.1053/j.semtcvs.2012.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Widhe B, Bauer HCF, Scandinavian Sarcoma Group Surgical treatment is decisive for outcome in chondrosarcoma of the chest wall: a population-based Scandinavian Sarcoma Group study of 106 patients. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2009;137:610–614. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2008.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rocco G. Anterior chest wall resection and reconstruction. Oper Tech Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2013;18:32–41. doi: 10.1053/j.optechstcvs.2013.02.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meadows JA, Staats BA, Pairolero PC, Rodarte JR, Arnold PG. Effect of resection of the sternum and manubrium in conjunction with muscle transposition on pulmonary function. Mayo Clin Proc. 1985;60:604–609. doi: 10.1016/s0025-6196(12)60984-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hanna WC, Ferri LE, McKendy KM, Turcotte R, Sirois C, Mulder DS. Reconstruction after major chest wall resection: can rigid fixation be avoided? Surgery. 2011;150:590–597. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2011.07.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deschamps C, Tirnaksiz BM, Darbandi R, Trastek VF, Allen MS, Miller DL, et al. Early and long-term results of prosthetic chest wall reconstruction. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1999;117:588–591. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5223(99)70339-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lardinois D, Müller M, Furrer M, Banic A, Gugger M, Krueger T, et al. Functional assessment of chest wall integrity after methylmethacrylate reconstruction. Ann Thorac Surg. 2000;69:919–923. doi: 10.1016/S0003-4975(99)01422-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weyant MJ, Bains MS, Venkatraman E, Downey RJ, Park BJ, Flores RM, et al. Results of chest wall resection and reconstruction with and without rigid prosthesis. Ann Thorac Surg. 2006;81:279–285. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2005.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Butterworth JA, Garvey PB, Baumann DP, Zhang H, Rice DC, Butler CE. Optimizing reconstruction of oncologic sternectomy defects based on surgical outcomes. J Am Coll Surg. 2013;217:306–316. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2013.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tsukushi S, Nishida Y, Sugiura H, Yamada Y, Kamei Y, Toriyama K, et al. Non-rigid reconstruction of chest wall defects after resection of musculoskeletal tumors. Surg Today. 2015;45:150–155. doi: 10.1007/s00595-014-0871-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Banuelos J, Abu-Ghname A, Bite U, Moran SL, Bakri K, Blackmon SH, et al. Reconstruction of oncologic sternectomy defects: lessons learned from 60 cases at a single institution. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2019;7:e2351. doi: 10.1097/GOX.0000000000002351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Graeber GM. Chest wall resection and reconstruction. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1999;11:251–263. doi: 10.1016/s1043-0679(99)70066-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Attinger CE, Picken CA, Troost TR, Sessions RB. Minimizing pectoralis myocutaneous flap loss with the delay principle. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1996;114:148–157. doi: 10.1016/S0194-59989670303-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rochester SN, Lorenz W, Bolton W, Stephenson J, Ben-Or S. Pectoralis muscle flaps for mediastinal reconstruction. Oper Tech Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2020;25:42–56. doi: 10.1053/j.optechstcvs.2019.11.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]