Abstract

Aim

To evaluate the outcomes of isolated liver chemo perfusion in patients with hepatic metastases from uveal melanoma.

Materials and methods

Cardiovascular surgeons are often involved in the treatment of oncological diseases. Isolated liver chemoperfusion requires the use a heart–lung machine. A little more than 300 operations of isolated liver chemoperfusion have been performed worldwide. From 2020 to 2023, 38 cases of isolated liver chemoperfusion were performed at the Kostroma Clinical Oncological Dispensary.

Results

There were 3 deaths, 2 due to liver failure. The remaining patient had hepatic artery thrombosis, who despite emergency thrombectomy and repair of common hepatic artery succumbed to multiorgan failure. Bleeding was diagnosed in 7 patients in the postoperative period. In all cases, relaparotomy was performed to stop bleeding. Subsequently, no special features were noted. The median disease-free survival was 5.4 months. The median overall survival was 20.3 months at the time of submission of this manuscript.

Conclusions

Isolated liver chemoperfusion is a safe method of regional chemotherapy and can be considered in patients with isolated hepatic metastases from uveal melanoma.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12055-023-01620-6.

Keywords: Uveal melanoma, Uveal melanoma metastases, Isolated liver chemoperfusion

Introduction

Cardiovascular surgeons are often involved in the treatment of oncological diseases. Isolated liver chemoperfusion requires the use a heart–lung machine. The technology is complex and is performed only by vascular surgeons, because it is necessary to cannulate large vessels and use of heart lung machine. A little more than 300 operations of isolated liver chemoperfusion have been performed worldwide. This article presents the experience of Russian vascular surgeons in performing isolated liver chemoperfusion in the presence of hepatic metastases from uveal melanoma (UM).

UM is a rare malignant tumor that develops from the uveal tract of the eyeball [1, 2]. In 90% of cases, it is noted that its metastases spread mainly to the liver. Average survival without surgical treatment in such a situation is only 2–3 months [1–3].

The risk factors for the development of UM include light skin and eye color, nevi of different localization, and a mutation in breast cancer type 1 susceptibility protein [4]. The most common method of treating patients with this pathology is radiation therapy (92%), while enucleation is less commonly used [4–6]. The most common treatments for UM liver metastases are immunotherapy, chemo-embolization, trans-arterial chemo-embolization, immune-embolization, radio-embolization, and thermal ablation. However, their limited effectiveness does not allow prolonging the life of patients by more than 6 months [2–6].

Nowadays, a surgical approach for the treatment of metastases of UM of the liver is gaining popularity in the world—isolated chemoperfusion (ICP), which uses a heart–lung machine to deliver chemo-therapeutic drug only to the liver without any systemic distribution [1–5]. According to the literature, there are just over 300 cases of ICP implementation worldwide. The response to treatment is achieved in 66% of cases, and life expectancy increases up to 2 years [1–5].

Purpose of research

To evaluate the outcomes of isolated liver chemo perfusion in patients with hepatic metastases from uveal melanoma.

Materials and methods

Type of research

Prospective, observational study.

For the period from 2020 to 2022, 38 ICP procedures were performed at the Kostroma Clinical Oncology Dispensary. Melphalan hydrochloride, India, was the main drug for the implementation of ICP. Identification of liver UM metastases was performed using computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and biopsy.

The choice of treatment tactics was carried out by a council headed by the director of the Medical Radiological Scientific Centre. Due to the need for ICP, the council also made a decision on the life-saving use of Melphalan hydrochloride, India, which is not registered in the Russian Federation. The decision of the council was consistent with Article 47 and Article 48 of the Federal Law of April 12, 2010, No. 61-FZ “Circulation of Medicines” and the Decree of the Government of the Russian Federation of September 29, 2010 No. 771 “Rules for the Import of Medicines for Medical Use in the Russian Federation.”

At the prehospital stage, all patients underwent echocardiography, color duplex scanning of the brachiocephalic arteries, magnetic resonance imaging of the brain, color duplex scanning of the veins, and arteries of the lower extremities.

We used the Stockert S5 heart–lung machine and Sorin Kids D101 Physio oxygenator for cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB). Autotransfusion of blood was performed via cell saver. In 6 cases, the intervention was combined with adrenalectomy, in 2 with hysterectomy.

The inclusion and exclusions criteria

Inclusion criteria

Presence of UM metastases in the liver.

Exclusion criteria

Contraindications to the use of the drug Melphalan hydrochloride, end-stage cancer, the presence of a pathology that limited the patient’s life expectancy (severe chronic heart failure, acute coronary syndrome, acute cerebrovascular accident, multiple metastases in various organs).

Complication risk stratification

To stratify the risk of complications, the following were used:

Charlson index. When calculating the Charlson comorbidity index, scores for age and somatic diseases were summed up. The more points a patient scored, the higher the risk of complications and the lower the 10-year survival rate [5, 6].

Karnovsky index. The lower the index, the higher the risk of death [5, 6].

Asessment of the physical status of patients according to the classification of the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA). There are 6 classes. Class 1 indicates a normal healthy patient, class 6—a dying patient [5, 6].

Primary and the secondary endpoints

Primary endpoints: death, bleeding.

Secondary endpoints: tumor tissue decay syndrome, abscess formation of the left lobe of the liver, peritonitis, deep vein thrombosis of the lower extremities, hydrothorax, acute liver failure, anasarca, polyserositis, ischemic cholangiopathy, thrombosis of the common hepatic artery, detachment of the intima of the common hepatic artery. A composite endpoint (the sum of all complications) was also calculated. In the presence of several complications in one patient, they were not summed up and were regarded as “1.”

Operation technique

Schematically, the ICP operation is shown in the supplementary file.

Under endotracheal anesthesia, cannulas were inserted into the right jugular vein and right femoral vein. A J-shaped laparotomy, ligation and transection of the round ligament of the liver, dissection of the falciform ligament of the liver, and installation of a Tomson retractor were performed. Further, cholecystectomy was performed by the classical method. Then, the right sections of the colon and duodenum were mobilized according to Kocher using a monopolar coagulator. The inferior vena cava was exposed from its subhepatic section to the bifurcation, a tourniquet was placed on the latter in the subhepatic Section 1 cm above the renal veins. After that, the retrohepatic segment of the inferior vena cava was mobilized with separate isolation, ligation, and transection of all extrahepatic venous collaterals. Next, the elements of the hepatoduodenal ligament were mobilized—the portal vein, own hepatic artery (Latin version a. hepatica propria), then the common hepatic artery and gastroduodenal artery were visualized. The common hepatic artery and portal vein were taken on handles. The caval gates of the liver were distinguished with the establishment of a holder above the confluence of the hepatic veins. After that, unfractionated heparin was administered intravenously at the rate of 100 U/kg. The portal vein was then cannulated with the end of the cannula directed caudally.

The lines were connected, and blood from the portal vein and the subhepatic inferior vena cava was supplied to the right jugular vein with the launch of parallel circulation along this circuit at a speed of 1.5 l per minute using a roller pump. Next, the portal vein was cannulated in the cranial direction with an arterial cannula and the inferior vena cava was cannulated in its retro-hepatic segment above the renal veins, while its end was directed in the cranial direction. A bulldog-type vascular clamp was applied to the common hepatic artery, and the anterior wall of the gastroduodenal artery was dissected. A cannula was placed at its proximal end. The clamp was removed. Then, the right gastric artery was isolated, tied up, and crossed. Then the liver was preconditioned by clamping its own hepatic artery three times for 5 min, followed by the resumption of blood flow. After that, vascular isolation of the liver was carried out by clamping the common hepatic artery, the portal vein between the “supply” and “receiving cannula,” clamping the inferior vena cava in the sub- and supra-hepatic region with vascular clamps.

The start of isolated liver perfusion was performed by directing blood sampling from the retro-hepatic segment of the inferior vena cava to the reservoir (cardiotome), then to the oxygenator with a heat exchanger (39 °C) and then to the arterial cannula installed in the own hepatic artery and the cannula installed in the portal vein at a speed of 1.2 l per minute along the formed time contour with a solution consisting of 700 ml of physiological sodium chloride solution. Then, the tightness of the temporary circuit was checked by introducing 20 mg of Indocyanin green into it. Using the Karl Storz ISG module, visual control of the distribution of the fluorescent preparation was carried out with the installation of signs of leakage into the systemic circulation and thus the assessment of the adequacy of hepatic perfusion. One hundred milligrams of melphalan was injected into the formed temporary circuit. Perfusion was carried out for 60 min. Next, the liver was washed from the perfusate with an isotonic sodium chloride solution of 1500 ml and 500 ml of gelofusine + 300 ml of erythrocyte mass. Then the perfusion was stopped and the vascular isolation of the liver was removed. Decannulation and suturing of the vessel cannulation site was performed, and heparin was neutralized with a solution of 1.5 mg of protamine sulfate for every 100 IU of heparin. Drains were inserted to drain the subhepatic space, lesser sac, and pelvis. After heamostasis, the abdomen was closed in layers and a sterile dressing applied.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using STATISTICA (data analysis software system) version 8.0 (StatSoft, Inc. URL: www.statsoft.com). Data were presented as integer (n) and %. Long-term survival was assessed using Kaplan–Meier analysis.

Sample characteristic

The vast majority of patients were female and middle aged. Twelve patients (31.58%) had varicose veins of the lower extremities. Twelve patients (31.58%) had functional class 2 of chronic heart failure according to New York Heart Association (NYHA). Five patients (13.16%) had coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) more than 6 months ago. In isolated cases, such chronic pathologies (compensated) as type 2 diabetes mellitus, chronic bronchitis, coronary heart disease, chronic pancreatitis, chronic calculous cholecystitis, etc. were noted. In 2 (5.26%) of patients before ICP, atypical liver resection was performed, in another 2 (5.26%), radiofrequency ablation of liver metastases, and in 4 (10.53%), chemoembolization of liver metastases was performed (Table 1). Left ventricular ejection fraction in all patients was normal, while thickening of the interventricular septum was detected in 17 (44.7%), and every tenth had an atherosclerotic change in the aortic wall. In 5 (13.16%) of cases, hemodynamically insignificant stenoses of the internal carotid arteries were visualized (refer to supplementary file).

Table 1.

Clinical and demographic indicators

| Index | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Male | 14 | 36.84 |

| Young age (up to 44 years old) | 9 | 23.68 |

| Average age (45–59 years) | 18 | 47.37 |

| Old age (60–74 years) | 11 | 28.95 |

| Varicose veins | 12 | 31.58 |

| Hypertonic disease | 15 | 39.47 |

| Chronic bronchitis, remission | 2 | 5.26 |

| Renal cancer with a history of resection (chromophobic renal cell carcinoma) | 1 | 2.63 |

| Type 2 diabetes | 3 | 7.89 |

| Chronic heart failure | 8 | 21.05 |

| NYHA functional class 2 chronic heart failure | 12 | 31.58 |

| Cardiac ischemia | 4 | 10.53 |

| Symptomatic, focal epilepsy | 1 | 2.63 |

| Duodenal ulcer, remission | 2 | 5.26 |

| Uterine leukomyoma | 1 | 2.63 |

| Uterine fibroids | 4 | 10.3 |

| Endometriosis | 1 | 2.63 |

| Maxillary sinus cyst | 1 | 2.63 |

| Lipomatosis of the pancreas | 1 | 2.63 |

| Hepatitis C | 1 | 2.63 |

| Chronic pancreatitis, remission | 2 | 5.26 |

| Chronic calculous cholecystitis, remission | 3 | 7.89 |

| Autoimmune thyroiditis | 3 | 7.89 |

| Nodular goiter | 1 | 2.63 |

| Euthyroidism | 3 | 7.89 |

| History of hysterectomy | 2 | 5.26 |

| Anemia of moderate severity | 2 | 5.26 |

| Covid-19 more than 6 months ago | 5 | 13.16 |

| Stenosis of the lower third of the esophagus | 1 | 2.63 |

| Adrenal adenoma | 1 | 2.63 |

| Chronic colitis, remission | 1 | 2.63 |

| Diverticulosis of the sigmoid colon | 2 | 5.26 |

| History of chemoembolization of liver metastases | 4 | 10.53 |

| Atypical liver resection in history | 2 | 5.26 |

| Radiofrequency ablation of liver metastases in anamnesis | 2 | 5.26 |

| Small hydrothorax | 1 | 2.63 |

| Body surface area greater than 1.73 m2 | 23 | 60.53 |

| Body mass index 25–29.9 kg/m2 (overweight) | 9 | 23.68 |

| Body mass index 30–34.9 kg/m2 (obesity 1 degree) | 6 | 15.79 |

NYHA New York Heart Association

According to CT scan of the abdominal organs, most often liver metastases were localized in 6, 7, and 8 segments or the lesion was metachromic in nature (refer to supplementary file). Seventeen (44.74%) patients underwent eye brachytherapy and in 17 (44.74%) patients enucleation was carried out (refer to supplementary file).

Assessment of the physical status of patients according to the classification of the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) revealed 29 (76.32%) patients to be in class 3 status. At the same time, the Charlson index in 13 (34.21%) was greater than or equal to 10, and the Karnovsky index in 36 (94.74%) reached 100 (refer to supplementary file).

Results

The average duration of the operation was 478.9 ± 23.5 min. The average volume of blood loss was 1390.0 ± 342.4 ml. The amount of blood autotransfusion through cell saver reached 601.0 ± 236.9 ml. Four patients showed variant anatomy of the liver arteries (Mithels III) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Intraoperative characteristics

| Index | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Adrenalectomy (with fusion of the adrenal gland and metastasis of the visceral surface of the liver, to maintain ablation and reduce the risk of bleeding) | 6 | 15.79 |

| Appendectomy | 1 | 2.63 |

| Hysterectomy with fallopian tubes, suturing of the bladder wall | 1 | 2.63 |

| Extirpation of the uterus with left appendages with Transposition of the right ovary | 1 | 2.63 |

| The duration of the operation more than 500 min | 10 | 26.32 |

| Operation duration less than 401 min | 4 | 10.53 |

| The duration of cardiopulmonary bypass more than 80 min | 13 | 34.21 |

| IVC clamping time more than 65 min | 17 | 44.74 |

| The duration of chemoperfusion with a chemotherapy drug more than 60 min | 2 | 5.26 |

| Spontaneous decannulation intraoperatively | 2 | 5.26 |

| Jugular vein perforation | 2 | 5.26 |

| Splenectomy as a result of decapsulation in the area of the gate | 2 | 5.26 |

| Cholecystectomy | 33 | 86.84 |

| Variant structure of the arteries of the liver | 5 | 13.16 |

| Rupture of the mouth of the right phrenic vein | 1 | 2.63 |

| The amount of autotransfusion through cell saver more than 1000 ml | 6 | 15.79 |

| Blood loss over 1000 ml | 20 | 52.63 |

| The volume of plasma hemotransfusion more than 1500 ml | 6 | 15.79 |

| The volume of blood transfusion of erythrocyte mass more than 1500 ml | 6 | 15.79 |

IVC inferior vena cava

In two cases, spontaneous decannulation of the cannula in the proper hepatic artery occurred at 30 min of chemoperfusion (Table 2). Taking into account unstable hemodynamics, a decision was made to terminate the procedure. The perioperative blood parameters that we monitored are presented in the supplementary file.

At the start of the operation, the vast majority of pCO2 and lactate values were normal, and pO2 was above normal. At the time of the onset of ICP (after activation of cardiopulmonary bypass), we aimed for pO2 values above the normal with normal pCO2. At the same time, lactate increased above the normal in 31 (81.58%) patients. By the end of the operation, lactate and glucose levels were above the normal in all patients. Also, by the end of the operation, potassium was below normal in 15 (39.47%), and hemoglobin was below normal in 36 (94.74%) patients. A day after the operation, pCO2 and pO2 were normal, lactate remained above the normal in 33 (86.84%) patients (refer to supplementary file).

Bleeding was encountered in 9 (23.68%) patients in the postoperative period. In all cases, relaparotomy was performed to stop bleeding. Subsequent course was uneventful. The combined end points occurred in 16 (42.11%) patients (Table 3). Complications, while not largely preventable, can be reduced by use of risk stratification tables to select appropriate patients.

Table 3.

Hospital postoperative outcomes

| Index | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Tumor tissue collapse syndrome | 1 | 2.63 |

| Abscess of the left lobe of the liver | 1 | 2.63 |

| Peritonitis | 1 | 2.63 |

| Deep vein thrombosis of the lower extremities | 1 | 2.63 |

| Right-sided hydrothorax | 1 | 2.63 |

| Bilateral hydrothorax | 1 | 2.63 |

| Acute liver failure | 1 | 2.63 |

| Anasarca | 1 | 2.63 |

| Polyserositis | 1 | 2.63 |

| Ischemic cholangiopathy | 1 | 2.63 |

| Thrombosis of the common hepatic artery | 1 | 2.63 |

| Intimal detachment of the common hepatic artery | 2 | 5.26 |

| Bleeding | 9 | 23.68 |

| Biliary peritonitis | 1 | 2.63 |

| Revision, hemostasis | 9 | 23.68 |

| Death | 3 | 7.89 |

| Combined endpoints (sum of all complications) | 16 | 42.11 |

There were 3 (7.89%) deaths due to liver failure. The first patient had hepatic artery thrombosis, who despite emergency thrombectomy and vein patch repair of common hepatic artery succumbed to multi organ failure. In the second patient, leucopenia and thrombocytopenia occurred with deep vein thrombosis. Liver function worsened with increasing pleural effusion and ultimately multiorgan failure ensued, leading to death. The last patient developed right lower lobe pneumonia leading to septic shock and liver failure. This caused death of the patient on the 34th post operative day.

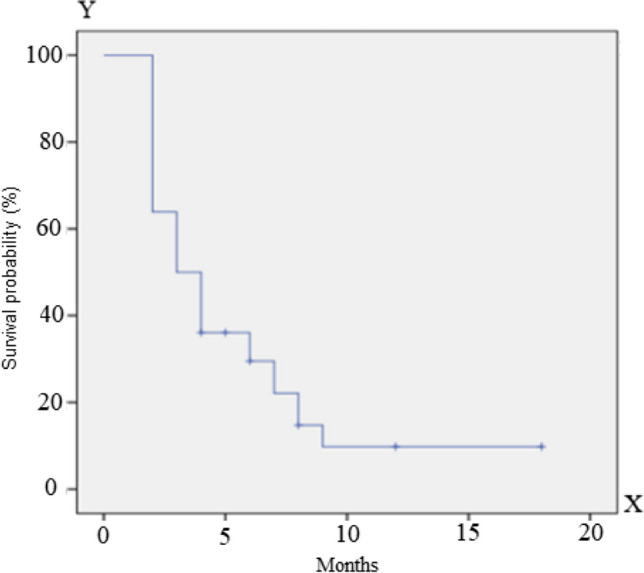

The median disease-free survival was 5.4 months; the median overall survival was 20.3 months at the time of submission of this manuscript (Figs. 1, 2).

Fig. 1.

Progression-free survival

Fig. 2.

Overall survival

Discussion

In our study, death occurred in 3 cases (7.89%). According to the literature, mortality in the hospital period after ICP can reach 27%. The main cause of death is the development of liver failure. Several studies reported significant morbidity and mortality as a result of the implementation of isolated liver chemoperfusion [7–9]. The largest cohort of 61 patients reported a 30-day mortality rate of 7% [10]. The average operation time was more than 8 h, and the average estimated blood loss was 2–3.5 l.

Another fairly common complication was bleeding requiring re-exploration and control. In all 9 cases, diffuse bleeding of tissues was noted during re-laparotomy, and coagulation hemostasis was performed with a satisfactory effect. The level of this complication did not exceed those established according to other studies [9–13].

It should be added that in two cases, during intraoperative decannulation, thrombosis of the common hepatic artery was noted as a result of intimal detachment. A longitudinal arteriotomy was performed with resection of the intima and plasty of the artery with a patch from the autogenous great saphenous vein. According to the results of color duplex scanning after the operation, the artery is functioning, and there is no thrombosis. This type of complication has not been described in the literature.

Study limitation

Small sample size.

Conclusion

ICP is a safe method of regional chemotherapy and can be considered in patients with isolated hepatic metastasis from uveal melanoma.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author contribution

Unguryan Vladimir Mikhailovich—performing operations, writing articles.

Kazantsev Anton Nikolaevich—performing operations, writing an article, creating a database, statistical analysis.

Korotkikh Alexander Vladimirovich—article writing, stylistic editing.

Ivanov Sergey Anatolyevich—performing operations, writing articles.

Belov Yury Vladimirovich—article writing, stylistic editing.

Kaprin Andrey Dmitrievich—article writing, stylistic editing.

Funding

None.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from the patients.

Human and animal rights statement

The study was performed in compliance with the ethical principles of scientific medical research involving humans. The work was performed in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, and did not contradict the Federal Law of the Russian Federation of November 21, 2011 No. April 1, 2016 N 200n “On approval of the rules of good clinical practice.”

Ethics committee approval

The study was approved by the decision of the local ethics committee of the A.F. Tsyba-National Medical Research Center for Radiology, extract from protocol No. 518 dated November 2, 2020.

Footnotes

The database on which the article is written has open access, official registration in the Russian Federation as intellectual property: DATABASE OF 38 PATIENTS WHO UNDERGOED ISOLATED LIVER CHEMOPERFUSION IN THE PRESENCE OF UVEAL MELANOMA METASTASES FOR THE PERIOD FROM 2020 — 2022. Unguryan V.M., Kazantsev A.N., Kravchuk V.N., Ermakov V.S., Belov Yu.V. Database registration certificate 2023621867, 06/07/2023. Application No. 2023621431 dated 05/22/2023. Link: https://www.elibrary.ru/item.asp?id=54047071.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Amaro A, Gangemi R, Piaggio F, Angelini G, Barisione G, Ferrini S, et al. The biology of uveal melanoma. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2017;36:109–140. doi: 10.1007/s10555-017-9663-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aronow ME, Topham AK, Singh AD. Uveal melanoma: 5-year update on incidence, treatment, and survival (SEER 1973–2013) Ocul Oncol Pathol. 2018;4:145–151. doi: 10.1159/000480640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaprin AD, Ivanov SA, Unguryan VM, Petrov LO, Pobedintseva YuA, Falaleeva NA, et al. Current possibilities of using isolated liver chemoperfusion in the treatment of metastatic uveal melanoma. Palliat Med Rehabil. 2021;4:5–10. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaliki S, Shields CL. Uveal melanoma: relatively rare but deadly cancer. Eye (Lond) 2017;31:241–257. doi: 10.1038/eye.2016.275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Unguryan VM, Kazantsev AN, Belov YuV. The choice of vascular access for isolated liver chemoperfusion in liver metastases. place of artificial circulation. Lit Rev. Russian J Cardiol. 2023;28:101–107. doi: 10.15829/1560-4071-2023-5393. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Unguryan VM, Kazantsev AN, Korotkikh AV, Ivanov SA, Belov YuV, Kaprin AD. Personalized choice of vascular access for isolated liver chemoperfusion: analysis of stratification programs the risk of complications. Russian J Cardiol. 2023;28:5486. doi: 10.15829/1560-4071-2023-5486. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ulmer A, Beutel J, Süsskind D, Hilgers RD, Ziemssen F, Lüke M, et al. Visualization of circulating melanoma cells in peripheral blood of patients with primary uveal melanoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:4469–4474. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saakyan SV, Panteleeva OG, Shirin TV. Features of metastatic lesions and survival of patients with uveal melanoma depending on the method of treatment. Russ Ophthalmol J. 2012;5:55–8.

- 9.Rowcroft A, Loveday BPT, Thomson BNJ, Banting S, Knowles B. Systematic review of liver directed therapy for uveal melanoma hepatic metastases. HPB (Oxford) 2020;22:497–505. doi: 10.1016/j.hpb.2019.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ben-Shabat I, Belgrano V, Ny L, Nilsson J, Lindnér P, Olofsson BR. Long-term follow-up evaluation of 68 patients with uveal melanoma liver metastases treated with isolated hepatic perfusion. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23:1327–1334. doi: 10.1245/s10434-015-4982-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang XY, Xie F, Tao R, Li AJ, Wu MC. Treatment of liver metastases from uveal melanoma: a retrospective single-center analysis. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2013;12:602–606. doi: 10.1016/s1499-3872(13)60095-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ben-Shabat I, Belgrano V, Hansson C, Olofsson Bagge R. The effect of perfusate buffering on toxicity and response in isolated hepatic perfusion for uveal melanoma liver metastases. Int J Hyperth. 2017;1–17. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Kaprin AD, Ivanov SA, Unguryan VM, Kazantsev AN, Belov YuV. A method for isolated liver perfusion with melphalan followed by pembrolizumab therapy in the treatment of unresectable metastases of uveal melanoma limited to the liver. Surgery Journal them. N.I. Pirogov. 2023;7:94–99. doi: 10.17116/hirurgia202307194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.