Abstract

Introduction

Treatment options for children younger than 6 years with severe atopic dermatitis (AD) are limited, as systemic immunosuppressants may present safety concerns in this young age group. Dupilumab is the first systemic treatment option approved for infants and young children with severe AD in the European Union. This study reports the efficacy and safety of dupilumab with concomitant low-potency corticosteroids in children aged 6 months to 5 years with severe AD.

Methods

This was a pre-specified subgroup analysis of data for patients aged 6 months to 5 years with severe AD at baseline (Investigator’s Global Assessment [IGA] = 4) from a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase III trial of dupilumab. Patients were randomised to either subcutaneously administered dupilumab (200/300 mg) or matched placebo every 4 weeks, plus low-potency topical corticosteroids for 16 weeks. Co-primary endpoints at week 16 were the proportion of patients with IGA ≤ 1 (clear or almost clear skin) and the proportion of patients with ≥ 75% improvement from baseline in Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI-75). Secondary endpoints at week 16 included mean changes in EASI, pruritus, skin pain, sleep loss and quality of life.

Results

The analysis included 125 patients (63 receiving dupilumab vs. 62 placebo). At week 16, significantly more patients receiving dupilumab vs. placebo had achieved IGA ≤ 1 (14.3% vs. 1.6%; P = 0.0085) and EASI-75 (46.0% vs. 6.6%; P < 0.0001). Significant improvements with dupilumab were observed in all secondary endpoints, including a least squares mean 44.9% reduction in pruritus. The overall incidence of adverse events (AEs) was similar between the dupilumab and placebo groups (66.7% vs. 73.8%). No dupilumab-related AEs were serious or led to treatment discontinuation.

Conclusion

Dupilumab significantly improved AD signs, symptoms and quality of life in children aged 6 months to 5 years with severe AD with acceptable safety.

Trial Registration

The trial was registered with ClinicalTrials.gov with ID number NCT03346434, part B.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12325-023-02753-1.

Keywords: Atopic dermatitis, Dupilumab, Eczema, Pediatric dermatology

Plain Language Summary

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic skin disease that is relatively common in infants and young children worldwide. Severe AD causes skin rashes and intense itch that strongly interfere with sleep quality and normal daily activities, thereby affecting the quality of life of patients and their families. When therapies for AD that are applied to the skin do not work, limited options are available to treat severe AD in children younger than 6 years. In this study, we evaluated the efficacy and safety of dupilumab in children aged 6 months to 5 years with severe AD, recruited from various sites in Europe and North America. Patients received 200 or 300 mg of dupilumab (based on the child’s weight) or placebo, together with mild steroids applied to the skin, every 4 weeks for 16 weeks. At the end of treatment, AD severity was greatly improved in patients receiving dupilumab, with 14% of patients achieving almost clear skin. Patients receiving dupilumab also experienced significant improvements in itch intensity, sleep quality, skin pain, and quality of life. Furthermore, dupilumab did not increase the risk of infections. This study demonstrates that dupilumab can be effective at treating severe AD in infants and young children, with important benefits for the quality of life of patients and their families.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12325-023-02753-1.

Key Summary Points

| Why carry out this study? | |

| Severe atopic dermatitis (AD) strongly affects the quality of life of infants and young children, as well as their family members. | |

| Until recently, there were no licensed systemic treatment options for infants and young children with severe atopic dermatitis. | |

| What was learned from the study? | |

| Dupilumab (200/300 mg via subcutaneous injections every 4 weeks for 16 weeks) rapidly and significantly improved AD signs and symptoms in infants and young children with severe AD. | |

| Dupilumab was well tolerated and demonstrated an acceptable safety profile. |

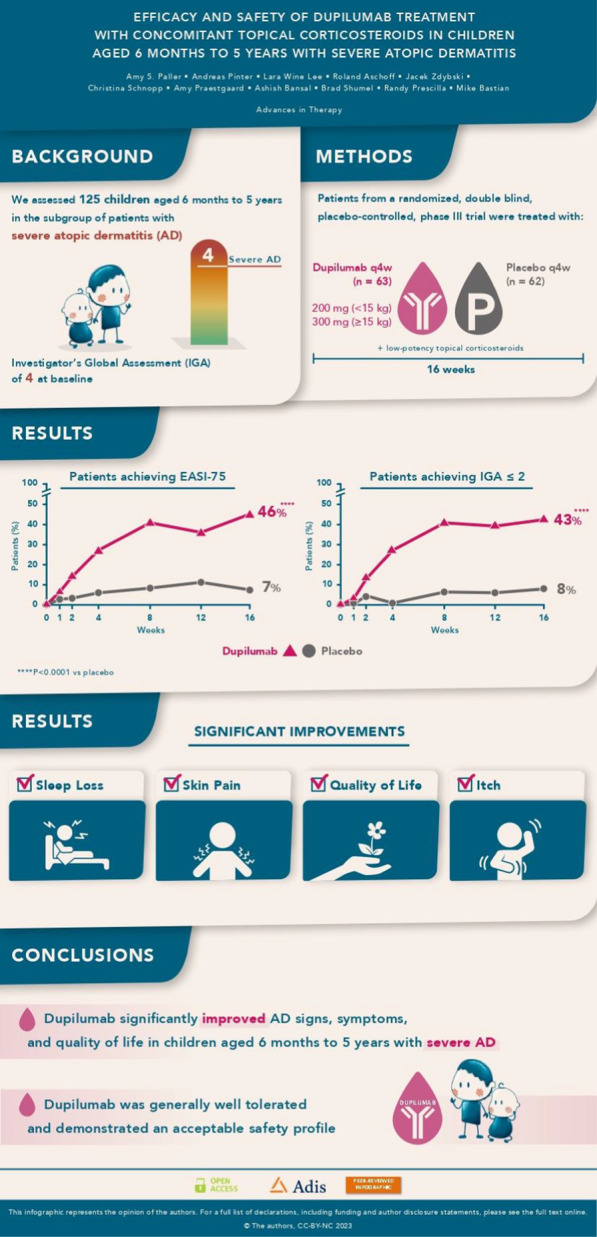

Infographic

Digital Features

This article is published with digital features, including a video abstract and infographic, to facilitate understanding of the article. To view digital features for this article, go to 10.6084/m9.figshare.24637974.

Efficacy and safety of dupilumab in infants and young children with severe atopic dermatitis – Video abstract

Introduction

Atopic dermatitis (AD) can strongly impair the quality of life of affected children and their caregivers, with higher AD severity causing a greater impact [1–5]. An international cross-sectional study found a prevalence of diagnosed AD of 12.1% in children aged 6 months to 5 years, with the proportion of severe AD ranging from 0.9% to 14.9% across countries [6].

In Europe and most countries around the world, no systemic treatment options were licensed for children aged under 6 years with an inadequate response to topical therapies until 2023. Only off-label systemic immunosuppressants (e.g. cyclosporin A, methotrexate, azathioprine or mycophenolate mofetil) were recommended in this young age group with severe disease by the European Task Force on Atopic Dermatitis/European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (ETFAD/EADV) eczema task force [7]. However, there are safety concerns surrounding the long-term use of systemic immunosuppressants in young children, as they may increase the risk of infection and other side effects [8–10].

Dupilumab is a fully human VelocImmune®-derived [11, 12] monoclonal antibody that inhibits the signalling of interleukin (IL)-4 and IL-13 [13, 14], which are key drivers of type 2-mediated inflammation in multiple diseases [13, 15, 16]. Dupilumab was approved in the USA for children aged 6 months to 5 years with moderate-to-severe AD [17] following the results of the phase III LIBERTY AD PRESCHOOL Part B study [18] and is currently the only systemic therapy approved for AD in this age cohort. In Europe, dupilumab has been approved by the European Medicines Agency in 2023 for children aged 6 months to 5 years with severe AD only; this is the labelled population in most countries outside the USA.

Findings from the primary analysis demonstrated that dupilumab significantly improved AD signs, symptoms and quality of life in infants and young children with moderate-to-severe AD and an acceptable safety profile [18]. Here, we present a pre-specified subgroup analysis from the same trial assessing the efficacy and safety of dupilumab in children aged 6 months to 5 years with severe AD (Investigator’s Global Assessment [IGA] = 4 at baseline).

Methods

Study Design and Participants

LIBERTY AD PRESCHOOL Part B was a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group phase III clinical trial. The full study design, all inclusion and exclusion criteria and the protocol and statistical analysis plan have been previously reported [18]. Briefly, patients aged 6 months to 5 years with moderate-to-severe AD (defined as Investigator’s Global Assessment [IGA] score = 3–4 at screening and baseline visits) inadequately controlled by topical corticosteroids were enrolled at 31 study sites in Europe and North America. This pre-specified analysis includes only data for the subgroup of patients with severe AD (IGA = 4) at baseline.

LIBERTY AD PRESCHOOL Part B was conducted in accordance with the provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki, the International Conference on Harmonisation Good Clinical Practice guideline, and applicable regulatory requirements. Masked monitoring of patient safety data was conducted by an independent data and safety monitoring committee. Local institutional review boards or ethics committees at each trial centre oversaw trial conduct and documentation, and reviewed and approved the study protocol. Written informed consent was obtained from a parent or legal guardian for each patient. The trial was registered with ClinicalTrials.gov with ID number NCT03346434 on November 17, 2017.

Randomisation and Procedures

The full details of randomisation and all other procedures employed in LIBERTY AD PRESCHOOL Part B have been previously reported [18]. Patients were randomised (1:1) to receive either dupilumab or matched placebo. Randomisation was stratified according to baseline disease severity (IGA = 3 vs. 4), baseline body weight (≥ 5 kg to < 15 kg vs. ≥ 15 kg to < 30 kg) and region (North America vs. Europe). Only data for the subgroup of patients with severe AD (IGA = 4) at baseline were included in this analysis.

Randomised patients received either dupilumab subcutaneously (200 mg for baseline body weight ≥ 5 kg to < 15 kg; 300 mg for baseline body weight ≥ 15 kg to 30 kg) or matched placebo every 4 weeks (q4w) for the 16-week treatment period. Patients also received a standardised once-daily regimen of low-potency topical corticosteroids (TCS; hydrocortisone acetate 1% cream) beginning 14 days before randomisation and continuing through the 16-week treatment period. For patients who achieved IGA ≤ 2, TCS use was tapered to three times per week and stopped for patients with IGA = 0. Moisturiser use was required twice daily from 7 days before randomisation and was continued throughout the treatment period. During the study period, systemic immunomodulating therapies (e.g. cyclosporine, methotrexate, mycophenolate mofetil, and azathioprine), medium- or higher-potency topical corticosteroids, crisaborole and topical calcineurin inhibitors were prohibited. However, they could be used as rescue treatment for worsening disease at the investigator’s discretion after day 14. Patients who received systemic therapy as rescue treatment were permanently discontinued.

Endpoints

The study endpoints were pre-specified in the study protocol and statistical analysis plan. The co-primary efficacy endpoints were proportion of patients achieving clear or almost clear skin (IGA score ≤ 1) at week 16 and proportion of patients with ≥ 75% improvement from baseline in EASI (EASI-75) at week 16. Additional secondary endpoints included mean percent change in EASI from baseline to week 16; percent change in weekly mean Worst Scratch/Itch numerical rating score (NRS); proportion of patients with ≥ 50%/≥ 90% improvement from baseline in EASI (EASI-50/EASI-90) at week 16; mean change from baseline to week 16 in percent of body surface area (BSA) affected by AD; mean change from baseline to week 16 in Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure (POEM); mean percent change from baseline to week 16 in SCORing Atopic Dermatitis (SCORAD) score; mean change from baseline to week 16 in skin pain NRS; mean change from baseline to week 16 in sleep quality NRS; mean change from baseline to week 16 in Dermatitis Family Impact (DFI); mean change from baseline to week 16 in health-related quality of life as measured by Children’s Dermatology Life Quality Index (CDLQI) for patients ≥ 4 years of age or Infants’ Dermatitis Quality of Life Index (IDQoL) for patients < 4 years of age; and proportion of patients achieving IGA ≤ 2 at week 16.

Safety outcomes included incidence of treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs), serious TEAEs, severe TEAEs, TEAEs of special interest and TEAEs leading to study withdrawal. Pre-specified biomarker analyses included mean and median changes in haematologic and serum chemistry parameters from baseline, as well as median percent changes in serum levels of CC chemokine ligand 17 (CCL17) and total immunoglobulin E (IgE).

Statistical Analysis

The efficacy analyses were performed using the full analysis set of randomised patients with IGA = 4 at baseline based on treatment allocation as randomly assigned. Safety analyses were performed in the safety analysis set, which consisted of all randomised patients with IGA = 4 at baseline who received any study drug as treated.

For categorical or ordinal data, frequencies and percentages are displayed for each category. Categorical endpoints were analysed using a Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel test after adjustment for randomisation strata. Patients with missing values at week 16 were considered non-responders.

For continuous variables, descriptive statistics included the number of patients reflected in the calculation (n), mean, standard deviation (SD) and standard error (SE). Continuous endpoints were analysed using analysis of covariance, with treatment group, stratification factors, and relevant baseline measurements included in the model. Patients with missing values at week 16 were imputed by worst observation carried forward.

All P values were nominal at the two-sided 0.05 significance level. Sensitivity analyses were performed for the primary and secondary endpoints using all observed values regardless of the use of rescue treatment. All statistics for safety were descriptive. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 or higher.

Results

Between 30 June 2020 and 8 July 2021, 197 participants were screened and 162 were randomly assigned to treatment groups. Data from 125 patients with severe AD at baseline were available for this analysis (dupilumab + TCS: n = 63 [6 patients aged < 2 years, 57 patients aged 2–5 years], mean age 3.9 years, 58.7% male; placebo + TCS: n = 62 [3 patients aged < 2 years, 59 patients aged 2–5 years], mean age 3.9 years, 67.7% male). Baseline demographics and clinical characteristics were generally well balanced between the groups with a high disease burden at baseline (Table 1). As a result of a randomisation error, one patient in the placebo group was randomly assigned but not treated; this patient was included in the efficacy analyses, with data being imputed using multiple imputation.

Table 1.

Baseline demographics and clinical characteristics

| Placebo + TCS (N = 62) | Dupilumab 200/300 mg q4w + TCS (N = 63) | |

|---|---|---|

| Baseline demographics | ||

| Age, mean (SD), years | 3.9 (1.2) | 3.9 (1.3) |

| Age group (years), n (%) | ||

| 6 months to < 2 years | 3 (4.8) | 6 (9.5) |

| ≥ 2 years to 5 years | 59 (95.2) | 57 (90.5) |

| Sex, male (%) | 42 (67.7) | 37 (58.7) |

| Race, n (%) | ||

| White | 38 (61.3) | 43 (68.3) |

| Black/African American | 15 (24.2) | 12 (19.0) |

| Other | 9 (14.5) | 8 (12.7) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | ||

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 56 (90.3) | 52 (82.5) |

| Hispanic or Latino | 6 (9.7) | 11 (17.5) |

| Height (cm), mean (SD)a | 101.2 (10.2) | 99.8 (12.7) |

| Weight (kg), mean (SD) | 17.0 (3.7) | 17.2 (4.5) |

| Weight group (kg), n (%) | ||

| 5 to < 15 | 18 (29.0) | 18 (28.6) |

| 15 to < 30 | 44 (71.0) | 45 (71.4) |

| BMI, mean (SD)b | 16.3 (2.0) | 17.2 (6.3) |

| Country, n (%) | ||

| Germany | 2 (3.2) | 4 (6.3) |

| Poland | 15 (24.2) | 15 (23.8) |

| UK | 5 (8.1) | 4 (6.3) |

| USA | 40 (64.5) | 40 (63.5) |

| Clinical characteristics | ||

| Age at disease onset, n (%) | ||

| < 6 months | 44 (71.0) | 36 (57.1) |

| ≥ 6 months | 18 (29.0) | 27 (42.9) |

| Duration of AD, mean (SD; range), years | 3.5 (1.3; 0–6) | 3.3 (1.4; 0–6) |

| Duration of AD, n (%) | ||

| < 3 years | 22 (35.5) | 23 (36.5) |

| ≥ 3 years | 40 (64.5) | 40 (63.5) |

| EASI, mean (SD; range) | 35.4 (12.0; 12–72) | 38.8 (13.7; 18–72) |

| SCORAD, mean (SD; range) | 74.8 (10.8; 50–98) | 76.7 (11.5; 50–98) |

| BSA of AD, mean (SD; range) | 58.9 (21.4; 14–100) | 63.1 (21.1; 19–100) |

| Weekly average of daily worst scratch/itch score, mean (SD; range) | 7.6 (1.6; 2–10) | 7.6 (1.4; 4–10) |

| Caregiver Global Impression of Disease, n (%) | ||

| Moderate | 9 (14.5) | 7 (11.1) |

| Severe | 31 (50.0) | 31 (49.2) |

| Very severe | 22 (35.5) | 25 (39.7) |

| POEM, mean (SD; range) | 23.4 (4.0; 9–28) | 23.7 (3.9; 14–28) |

| CDLQI, mean (SD; range)*c | 17.8 (6.4; 5–28) | 17.5 (5.5; 7–29) |

| IDQOL, mean (SD; range)*d | 17.4 (5.4; 5–28) | 18.4 (5.1; 10–29) |

| GISS, mean (SD; range) | 10.1 (1.5; 7–12) | 10.3 (1.5; 7–12) |

| DFI, mean (SD; range) | 17.4 (7.5; 3–29) | 17.6 (6.0; 5–30) |

| Weekly average of daily skin pain NRS score, mean (SD; range)e | 7.1 (1.9; 2–10) | 6.9 (1.9; 1–10) |

| Weekly average of daily patient's sleep quality score, mean (SD; range)f | 4.7 (2.0; 0–9) | 4.9 (2.0; 0–9) |

| Weekly average of daily caregiver's sleep quality score, mean (SD; range)g | 4.8 (2.0; 0–9) | 5.1 (2.0; 0–9) |

| Patients with ≥ 1 concurrent allergic condition, n (%) | ||

| Food allergy (self-reported) | 46 (74.2) | 42 (66.7) |

| Allergic rhinitis | 31 (50.0) | 25 (39.7) |

| Asthma | 18 (29.0) | 14 (22.2) |

| Hives | 16 (25.8) | 15 (23.8) |

| Allergic conjunctivitis | 4 (6.5) | 4 (6.4) |

| Chronic rhinosinusitis | 2 (3.2) | 0 |

| Eosinophilic esophagitis | 2 (3.2) | 2 (3.2) |

| Nasal polyps | 0 | 0 |

| Other allergies | 35 (56.5) | 34 (54.0) |

| Prior systemic medications for AD, n (%) | 17 (27.4) | 20 (31.8) |

| Prior systemic corticosteroids | 10 (16.1) | 13 (20.6) |

| Prior systemic non-steroidal immunosuppressants | 10 (16.1) | 12 (19.1) |

| Cyclosporine | 7 (11.3) | 9 (14.3) |

| Methotrexate | 5 (8.1) | 5 (7.9) |

| Mycophenolate | 2 (3.2) | 2 (3.2) |

| Azathioprine | 1 (1.6) | 1 (1.6) |

AD atopic dermatitis, BMI body mass index, BSA body surface area, CDLQI Child Dermatology Life Quality Index, DFI Dermatitis Family Impact, EASI Eczema Area and Severity Index, EASI-75 75% decrease in EASI, GISS Global Individual Signs Score, IDQOL Infants' Dermatitis Quality of Life Index, IGA Investigator’s Global Assessment, LS least squares, NRS Numerical Rating Scale, POEM Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure, q4w every 4 weeks, SCORAD SCORing Atopic Dermatitis, SD standard deviation, TEAE treatment-emergent adverse event, TCS topical corticosteroids

*IDQOL for patients aged < 4 years; CDLQI for patients aged ≥ 4 years, aPlacebo group n = 61, dupilumab group n = 63. bPlacebo group n = 61, dupilumab group n = 63. cPlacebo group n = 32, dupilumab group n = 38. dPlacebo group n = 30, dupilumab group n = 25. ePlacebo group n = 61, dupilumab group n = 62. fPlacebo group n = 62, dupilumab group n = 62. gPlacebo group n = 62, dupilumab group n = 62

Efficacy Outcomes

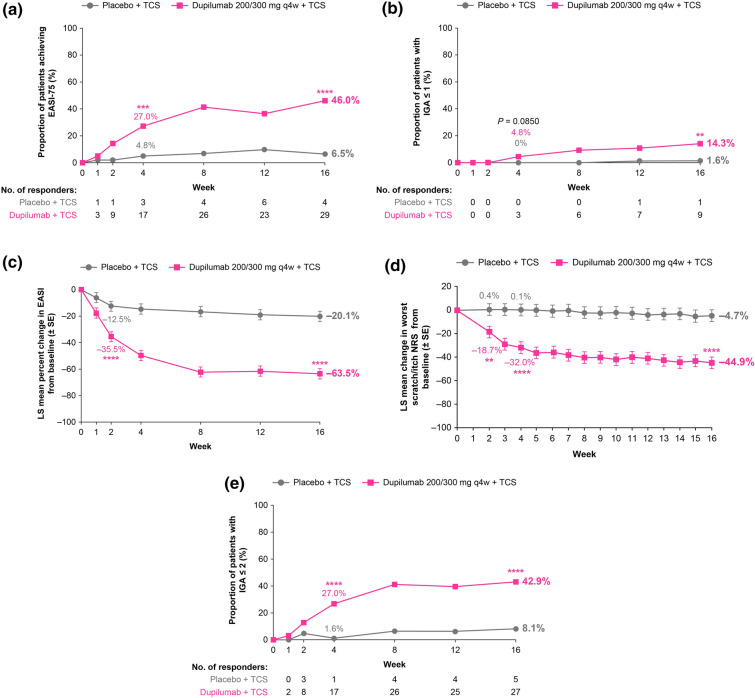

Treatment with dupilumab vs. placebo resulted in significant improvements in both co-primary and all secondary efficacy endpoints at week 16 (Table 2, Fig. 1). A significantly greater proportion of patients in the dupilumab group than in the placebo group achieved EASI-75 by week 4 of treatment, with improvements sustained through week 16 (Fig. 1a, Table S1 in the supplementary material). Significantly more patients in the dupilumab group achieved IGA ≤ 1 at week 16 compared with the placebo group (Fig. 1b).

Table 2.

Efficacy outcomes at week 16

| Placebo + TCS (N = 62) | Dupilumab 200/300 mg q4w + TCS (N = 63) | ∆ vs. placebo (95% CI) | P value vs. placebo | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients with IGA ≤ 1 (score range 0–4), n (%) | 1 (1.6) | 9 (14.3) | 12.7 (3.4, 21.9) | 0.0085 |

| Patients with IGA ≤ 2 (score range 0–4), n (%) | 5 (8.2) | 27 (42.9) | 34.7 (20.6, 48.7) | < 0.0001 |

| Patients with EASI-75 (score range 0–72), n (%) | 4 (6.6) | 29 (46.0) | 39.5 (25.7, 53.3) | < 0.0001 |

| Percent change from baseline in EASI, LS mean (SE) | − 20.1 (3.84) | − 63.5 (3.81) | − 43.5 (− 53.66, − 33.32) | < 0.0001 |

| Percent change from baseline in Worst Scratch/Itch NRS (score range 0–10), LS mean (SE) | − 4.7 (5.07) | − 44.9 (4.99) | − 40.2 (− 53.41, − 27.00) | < 0.0001 |

| Patients with improvement of weekly average of daily Worst Scratch/Itch NRS ≥ 4, n (%) | 5 (8.8) | 27 (42.3) | 33.5 (19.0, 48.0) | 0.0002 |

| Patients with improvement of weekly average of daily Worst Scratch/Itch NRS ≥ 3, n (%) | 6 (9.5) | 29 (45.4) | 35.9 (21.0, 50.8) | < 0.0001 |

| Patients with EASI-50, n (%) | 12 (19.2) | 38 (60.3) | 41.1 (25.3, 56.9) | < 0.0001 |

| Patients with EASI-90, n (%) | 0 (0) | 10 (15.9) | 15.5 (6.2, 24.8) | 0.0043 |

| Change from baseline in percent BSA affected by AD, LS mean (SE) | − 7.6 (3.0) | − 29.4 (2.9) | − 21.8 (− 30.0, − 13.6) | < 0.0001 |

| Change from baseline in POEM (scale range 0–28), LS mean (SE) | − 2.5 (1.0) | − 10.6 (0.9) | − 8.1 (− 10.7, − 5.5) | < 0.0001 |

| Percent change from baseline in SCORAD (score range 0 − 103), LS mean (SE) | − 11.1 (3.5) | − 44.6 (3.4) | − 33.4 (− 43.0, − 23.9) | < 0.0001 |

| Change from baseline in patient’s sleep quality NRS* (0–10), LS mean (SE) | 0.2 (0.2) | 1.7 (0.3) | 1.5 (0.8, 2.2) | < 0.0001 |

| Change from baseline in patient’s skin pain NRS (range 0–10), LS mean (SE) | − 0.3 (0.3) | − 3.4 (0.3) | − 3.1 (− 3.9, − 2.3) | < 0.0001 |

| Change from baseline in DFI (0–30), LS mean (SE) | − 2.1 (0.8) | − 9.1 (0.8) | − 7.1 (− 9.4, − 4.8) | < 0.0001 |

| Change from baseline in CDLQI (0–30), LS mean (SE)a | − 2.6 (1.2) | − 9.1 (1.1) | − 6.6 (− 9.7, − 3.4) | < 0.0001 |

| Change from baseline in IDQOL (0–30), LS mean (SE)b | − 0.6 (1.1) | − 9.1(1.3) | − 8.5 (− 11.8, − 5.1) | < 0.0001 |

BSA body surface area, CDLQI Children’s Dermatology Life Quality Index, DFI Dermatitis Family Impact, EASI Eczema Area and Severity Index, EASI-75 75% decrease in EASI, IDQOL Infants’ Dermatitis Quality of Life Index, IGA Investigator’s Global Assessment, LS least squares, NRS Numerical Rating Scale, POEM Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure, q4w every 4 weeks, SCORAD SCORing Atopic Dermatitis, SE standard error, TEAE treatment-emergent adverse event, TCS topical corticosteroids

*Increase in score means improvement. aPlacebo group n = 32, dupilumab group n = 37. bPlacebo group n = 30, dupilumab group n = 26

Fig. 1.

Primary and key secondary endpoints. a Proportion of patients with EASI-75 through week 16. b Proportion of patients with IGA ≤ 1 through to week 16. c LS mean percentage change in EASI from baseline through week 16. d LS mean percentage change in weekly mean of daily Worst Scratch and Itch NRS score from baseline through week 16. e Proportion of patients with IGA ≤ 2 through week 16. **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001, all vs. corresponding placebo + TCS. EASI Eczema Area and Severity Index, EASI-75 75% decrease in EASI, IGA Investigator’s Global Assessment, LS least squares, NRS Numerical Rating Scale, q4w every 4 weeks, TCS topical corticosteroid

LS mean percent change from baseline in EASI score and Worst Scratch/Itch NRS score was significantly greater in the dupilumab group than in the placebo group by week 2 of treatment, with improvements sustained through week 16 (Fig. 1c, d). Significant improvements in percent BSA affected by AD, POEM, SCORAD, sleep quality, skin pain, CDLQI, IDQoL and DFI scores were observed for patients in the dupilumab group compared to the placebo group by week 4 of treatment (Table S1 in the supplementary material) and were maintained through week 16 (Table 2). Moreover, a significantly greater proportion of patients in the dupilumab group than in the placebo group achieved IGA ≤ 2 by week 4 of treatment with improvements sustained through week 16 (Fig. 1e, Table S1 in the supplementary material).

A subgroup analysis of data stratified according to patient body weight (≥ 5 kg to < 15 kg vs. ≥ 15 kg to < 30 kg) showed a consistent benefit for dupilumab vs. placebo in both body weight categories for most endpoints evaluated (Table S2 in the supplementary material). Sensitivity analyses using all observed values regardless of rescue treatment use showed little effect of rescue treatment on the primary or secondary outcomes (Fig. S1 in the supplementary material). Use of rescue treatment was substantially higher in the placebo group compared to the dupilumab group (Fig. S2 in the supplementary material). Rescue treatment was predominantly topical; only one patient in each group received systemic corticosteroids for rescue of AD exacerbation.

Safety Outcomes

The overall incidence of TEAEs during the 16-week treatment period was similar between the dupilumab and placebo groups (Table 3). TEAEs that occurred at a higher rate in the dupilumab group than in the placebo group were dental caries, molluscum contagiosum, nasopharyngitis and conjunctivitis (Table 3). No patients reported serious TEAEs in the dupilumab group, compared with 3 patients (4.9%) in the placebo group (Table 3, Table S3 in the supplementary material). The incidence of severe TEAEs was also higher in the placebo group (7 patients; 11.5%) than in the dupilumab group (2 patients; 3.2%) (Table S4 in the supplementary material). In the dupilumab group, 8 patients (12.7%) had ≥ 1 TEAE deemed related to the study drug, compared with 5 (8.2%) in the placebo group (Table S5 in the supplementary material). The incidence of conjunctivitis was higher in the dupilumab group than in the placebo group (4 vs. 0 patients; Table 3, Table S6 in the supplementary material); however, all cases of conjunctivitis were mild, and no cases led to treatment discontinuation. The incidence of injection-site reactions was low in both groups (Table 3).

Table 3.

Summary of treatment-emergent adverse events

| Placebo + TCS (N = 61) | Dupilumab 200/300 mg q4w + TCS (N = 63) | |

|---|---|---|

| Overall summary | ||

| Patients with ≥ 1 TEAE | 45 (73.8%) | 42 (66.7%) |

| Patients with ≥ 1 serious TEAE | 3 (4.9%) | 0 |

| Patients with ≥ 1 TEAE leading to treatment discontinuation | 1 (1.6%) | 1 (1.6%) |

| Patients with ≥ 1 severe TEAE | 7 (11.5%) | 2 (3.2%) |

| Patients with ≥ 1 TEAE leading to death | 0 | 0 |

| Patients with ≥ 1 TEAE deemed related to study drug | 5 (8.2%) | 8 (12.7%) |

| Most frequent AEs by PT (≥ 5%) | ||

| Asthma | 5 (8.2%) | 3 (4.8%) |

| Cough | 4 (6.6%) | 0 |

| Dental caries | 0 | 4 (6.4%) |

| Dermatitis atopic | 16 (26.2%) | 10 (15.9%) |

| Impetigo | 5 (8.2%) | 2 (3.2%) |

| Lymphadenopathy | 5 (8.2%) | 3 (4.8%) |

| Molluscum contagiosum | 2 (3.3%) | 4 (6.4%) |

| Nasopharyngitis | 2 (3.3%) | 6 (9.5%) |

| Pyrexia | 7 (11.5%) | 1 (1.6%) |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 5 (8.2%) | 5 (7.9%) |

| TEAEs of special interest | ||

| Conjunctivitis (narrow)a | 0 | 4 (6.3%) |

| Conjunctivitis allergic (PT) | 0 | 1 (1.6%) |

| Conjunctivitis (PT) | 0 | 3 (4.8%) |

| Adjudicated non-herpetic skin infections | 16 (26.2%) | 9 (14.3%) |

| Skin structures and soft tissue infections excluding herpetic infections (HLT) | 8 (13.1%) | 5 (7.9%) |

| Herpes viral infections (HLT) | 4 (6.6%) | 3 (4.8%) |

| Injection-site reactions (HLT) | 2 (3.3%) | 1 (1.6%) |

HLT MedDRA High Level Term, MedDRA Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities, PT MedDRA Preferred Term, q4w every 4 weeks, TEAE treatment-emergent adverse event, TCS topical corticosteroids

aNarrow conjunctivitis group includes the following MedDRA PTs: atopic keratoconjunctivitis, conjunctivitis, conjunctivitis allergic, conjunctivitis bacterial, and conjunctivitis viral

Dupilumab-treated patients had a lower incidence of adjudicated skin infections (excluding herpes viral infections) compared with the placebo group (14.3% vs. 26.2%, respectively) (Table 3, Table S7 in the supplementary material). The incidence of herpes viral infections was similar between the groups (Table 3, Table S8 in the supplementary material). One patient in the placebo group (1.6%) had eczema herpeticum, whereas two patients in the dupilumab group (3.2%) had varicella (Table S8 in the supplementary material).

Biomarker Analyses

No significant differences were observed between the placebo and dupilumab group in haematology laboratory parameters (Fig. S3 in the supplementary material) or serum chemistry analyses (Fig. S4 in the supplementary material) throughout the treatment. A transient increase in mean eosinophil count was observed in the dupilumab group at week 4; however, it decreased again towards baseline values by week 16 (Fig. S3a in the supplementary material) and had no associated adverse events. A greater reduction in serum CCL17 was seen as early as week 4 in the dupilumab group (− 80.4 median percent change from baseline) vs. placebo (− 26.0 median percent change from baseline) and was maintained through week 16 (− 87.3 dupilumab vs. − 52.0 placebo) (Fig. S5 in the supplementary material). By week 16, serum total IgE decreased from baseline in the dupilumab group (− 72.2 median percent change), while it increased in the placebo group (8.9 median percent change) (Fig. S5 in the supplementary material).

Discussion

In this pre-specified subgroup analysis of patients aged 6 months to 5 years with severe AD at baseline from a randomised, placebo-controlled, phase III trial, treatment with dupilumab and low-potency TCS led to rapid and significant improvements vs. placebo in AD signs, symptoms and quality of life. Despite a very high disease burden at baseline, 46% of dupilumab-treated patients achieved a 75% reduction in EASI by week 16 (compared with 6.6% in the placebo group), together with significant improvements in pruritus, skin pain and sleep loss. In particular, dupilumab-treated patients achieved a LS mean 44.9% reduction in pruritus as assessed by Worst Scratch/Itch NRS, compared with 4.7% in the placebo group. Sensitivity analyses were consistent with the main analyses, and fewer patients in the dupilumab group required topical rescue treatment compared with the placebo group. Although only 14.3% of patients in the dupilumab group achieved IGA ≤ 1 (clear or almost clear skin) by week 16, this proportion was still significantly higher than in the placebo group (1.6%). Achievement of IGA ≤ 1 is a stringent outcome for patients with baseline IGA = 4, particularly in a short, 16-week treatment period. In addition, 42.9% of patients in the dupilumab group achieved IGA ≤ 2, corresponding to mild disease, compared with 8.2% in the placebo group by week 16.

Consistent with the study in infants and young children with moderate-to-severe AD [18] and similar to findings in older age groups [19–23], dupilumab demonstrated an acceptable safety profile with a lower incidence of severe TEAEs compared with placebo. No serious TEAEs or AEs leading to treatment discontinuation related to dupilumab were reported. Although cases of conjunctivitis and molluscum contagiosum were more frequent in the dupilumab group than in the placebo group, they were mild and resolved by the end of treatment. Interestingly, the incidence of conjunctivitis with dupilumab in this age group (6.3%) was lower than that reported in older age groups (14% in adults [20], 9.8% in adolescents [21], and 6.7% in children aged 6–11 years [23] with in-label doses). Furthermore, laboratory analyses showed no meaningful changes in haematologic or serum chemistry parameters associated with dupilumab treatment, consistent with older age groups [24–26].

These results demonstrate that dupilumab can significantly reduce AD severity in infants and young children with severe disease, as well as provide important benefits for the quality of life of both patients and caregivers. The reported safety outcomes indicate an acceptable safety profile in this population. Strengths of this study include the randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled design, stratification by disease severity, and background use of topical therapy. Limitations of the study are the low number of patients under 2 years of age, short treatment duration, and the limited geographic footprint of the trial, with sites only in North America and Europe.

Conclusion

Dupilumab with concomitant low-potency topical corticosteroids significantly improved AD signs, symptoms and quality of life among children aged 6 months to 5 years with severe AD, a population with a high unmet medical need. Improvements were seen as early as week 4 and sustained throughout 16 weeks of treatment. Dupilumab was generally well tolerated and demonstrated an acceptable safety profile consistent with that previously seen in adults, adolescents and children aged 6–11 years.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the patients and their caregivers for their participation, and publications managers Adriana Mello of Sanofi and Linda Williams of Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc., who provided support and input.

Medical Writing and Editorial Assistance.

Medical writing and editorial assistance were provided by Alessandra Iannino, PhD, and Carolyn Ellenberger, PhD, of Excerpta Medica, and were funded by Sanofi and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc., according to the Good Publication Practice guidelines.

Author Contributions

Amy S. Paller, Andreas Pinter, Lara Wine Lee, Roland Aschoff, Jacek Zdybski, and Christina Schnopp acquired data. Amy Praestgaard conducted the statistical analyses on the data. Amy S. Paller, Andreas Pinter, Lara Wine Lee, Roland Aschoff, Jacek Zdybski, Christina Schnopp, Amy Praestgaard, Ashish Bansal, Brad Shumel, Randy Prescilla, and Mike Bastian interpreted the data, provided critical feedback on the manuscript, approved the final manuscript for submission, and are accountable for the accuracy and integrity of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was sponsored by Sanofi and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc. ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier NCT03346434, part B. The study sponsors participated in the study design, collection, analysis and interpretation of the data, writing of the report, the decision to submit the article for publication, preparation of digital features, and the funding of the journal’s Rapid Service and Open Access Fees.

Data Availability

Qualified researchers may request access to study documents (including the clinical study report, study protocol with any amendments, blank case report form and statistical analysis plan) that support the methods and findings reported in this manuscript. Individual anonymised participant data will be considered for sharing once the product and indication have been approved by a regulatory body, if there is legal authority to share the data and there is not a reasonable likelihood of participant re-identification. Submit requests to https://vivli.org/.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

Amy S. Paller reports serving as an investigator, consultant and/or data and safety monitoring board member for AbbVie, Abeona Therapeutics, Amryt Pharma, Azitra, BioCryst, BMS, Boehringer Ingelheim, Castle Creek Biosciences, Catawba Research, Dermavant, Eli Lilly, Galderma, InMed Pharmaceuticals, Incyte, Janssen, Krystal Biotech, LEO Pharma, Novartis, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc., Sanofi, Seanergy, TWi Biotechnology and UCB. Andreas Pinter reports working for AbbVie, Almirall Hermal, Amgen, Biogen Idec, BioNTech, Boehringer Ingelheim, Celgene, Celltrion, Eli Lilly, Galderma, GSK, Hexal, Janssen, Klinge Pharma, LEO Pharma, MC2 Pharma, Medac, Merck-Serono, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, MSD, Novartis, Pascoe, Pfizer, Tigercat Pharma, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc., Roche, Sandoz, Sanofi, Schering-Plough and UCB Pharma. Lara Wine Lee reports acting as an advisory board member consultant, investigator and/or speaker for AbbVie, Amgen, Amryt Pharma, Arcutis Biotherapeutics, Avita, Castle Creek Biosciences, Celgene, Eli Lilly, Galderma, Incyte, Janssen, Kimberly Clark, Kiniksa Pharmaceuticals, Krystal Biotech, Mayne Pharma, MoonLake Immunotherapeutics, Novartis, Pfizer, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc., Sanofi, Target Pharma, Timber Pharmaceuticals, Trevi Therapeutics and UCB. Roland Aschoff reports working for AbbVie, Almirall Hermal, Biofrontera, Boehringer Ingelheim, BMS, BSN medical, Galderma, Janssen-Cilag, LEO Pharma, Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, Sanofi and UCB. Jacek Zdybski reports serving as an investigator for Almirall, Amgen, BMS, Galderma, Incyte, Innovaderm, Pfizer, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc. and Syneos Health. Christina Schnopp reports serving as lecturer and/or consultant for AbbVie, Amgen, Beiersdorf, Benevi, Celgene, Fortbildungskolleg GmbH, GSK, Galderma, HiPP Organic, InfectoPharm, La Roche-Posay, LEO Pharma, Leti Pharma, Lilly, MSD, Nestlé, Novartis, Nutricia, Pierre Fabre, Sanofi and Unna-Akademie. Amy Praestgaard, Randy Prescilla, and Mike Bastian are employees of and may hold stock and/or stock options in Sanofi. Ashish Bansal and Brad Shumel are employees and shareholders of Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc.

Ethical Approval

The study (trial registration number NCT03346434) was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, the International Conference on Harmonisation Good Clinical Practice guideline and applicable regulatory requirements. An independent data and safety monitoring committee conducted blinded monitoring of patient safety data. The local institutional review board or ethics committee at each study centre oversaw trial conduct and documentation. The study was approved by the Copernicus Group ethics committee. All patients, or their parents/guardians, provided written informed consent before participating in the trial. Pediatric patients provided assent according to the ethics committee (institutional review board/independent ethics committee)-approved standard practice for pediatric patients at each participating centre.

Footnotes

Prior Presentation: Some of the results from this study were presented at the Revolutionizing Atopic Dermatitis (RAD) Congress in December 2022.

The original article was revised due to update in Table 1.

Change history

5/2/2024

A Correction to this paper has been published: 10.1007/s12325-024-02866-1

References

- 1.Lewis-Jones S. Quality of life and childhood atopic dermatitis: the misery of living with childhood eczema. Int J Clin Pract. 2006;60:984–992. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2006.01047.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chamlin SL, Chren MM. Quality-of-life outcomes and measurement in childhood atopic dermatitis. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2010;30:281–288. doi: 10.1016/j.iac.2010.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barbarot S, Silverberg JI, Gadkari A, et al. The family impact of atopic dermatitis in the pediatric population: results from an international cross-sectional study. J Pediatr. 2022;246:220–226.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2022.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ben-Gashir MA, Seed PT, Hay RJ. Quality of life and disease severity are correlated in children with atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 2004;150:284–290. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2004.05776.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.El Achkar Mello ME, Simoni AG, Rupp ML, et al. Quality of life of pediatric patients with atopic dermatitis and their caregivers. Arch Dermatol Res. 2023 doi: 10.1007/s00403-023-02544-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Silverberg JI, Barbarot S, Gadkari A, et al. Atopic dermatitis in the pediatric population: a cross-sectional, international epidemiologic study. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2021;126:417–28.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2020.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wollenberg A, Christen-Zäch S, Taieb A, et al. ETFAD/EADV Eczema task force 2020 position paper on diagnosis and treatment of atopic dermatitis in adults and children. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:2717–2744. doi: 10.1111/jdv.16892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ricci G, Dondi A, Patrizi A, Masi M. Systemic therapy of atopic dermatitis in children. Drugs. 2009;69:297–306. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200969030-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sidbury R, Davis DM, Cohen DE, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: section 3. Management and treatment with phototherapy and systemic agents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:327–349. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2014.03.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wollenberg A, Barbarot S, Bieber T, et al. Consensus-based European guidelines for treatment of atopic eczema (atopic dermatitis) in adults and children: part II. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:850–878. doi: 10.1111/jdv.14888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Macdonald LE, Karow M, Stevens S, et al. Precise and in situ genetic humanization of 6 Mb of mouse immunoglobulin genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:5147–5152. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1323896111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Murphy AJ, Macdonald LE, Stevens S, et al. Mice with megabase humanization of their immunoglobulin genes generate antibodies as efficiently as normal mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:5153–5158. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1324022111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gandhi NA, Bennett BL, Graham NMH, et al. Targeting key proximal drivers of type 2 inflammation in disease. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2016;15:35–50. doi: 10.1038/nrd4624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Le Floc’h A, Allinne J, Nagashima K, et al. Dual blockade of IL-14 and IL-13 with dupilumab, an IL-4Rα antibody, is required to broadly inhibit type 2 inflammation. Allergy. 2020;75:1188–1204. doi: 10.1111/all.14151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gandhi NA, Pirozzi G, Graham NMH. Commonality of the IL-4/IL-13 pathway in atopic diseases. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2017;13:425–437. doi: 10.1080/1744666X.2017.1298443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haddad EB, Cyr SL, Arima K, et al. Current and emerging strategies to inhibit type 2 inflammation in atopic dermatitis. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) 2022;12:1501–1533. doi: 10.1007/s13555-022-00737-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.US Food and Drug Administration. Highlights of Prescribing Information: DUPIXENT® (dupilumab). https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2020/761055s020lbl.pdf. Accessed 15 May 2023.

- 18.Paller AS, Simpson EL, Siegfried EC, et al. Dupilumab in children ages 6 months to younger than 6 years with uncontrolled atopic dermatitis: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2022;400:908–919. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01539-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Simpson EL, Bieber T, Guttman-Yassky E, et al. Two phase 3 trials of dupilumab versus placebo in atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:2335–2348. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1610020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Blauvelt A, de Bruin-Weller M, Gooderham M, et al. Long-term management of moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis with dupilumab and concomitant topical corticosteroids (LIBERTY AD CHRONOS): a 1-year, randomised, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2017;389:2287–2303. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31191-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Simpson EL, Paller AS, Siegfried EC, et al. Efficacy and safety of dupilumab in adolescents with uncontrolled moderate to severe atopic dermatitis: a phase 3 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:44–56. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.3336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cork MJ, Thaci D, Eichenfield LF, et al. Dupilumab in adolescents with uncontrolled moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: results from a phase IIa open-label trial and subsequent phase III open-label extension. Br J Dermatol. 2020;182:85–96. doi: 10.1111/bjd.18476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Paller AS, Siegfried EC, Thaci D, et al. Efficacy and safety of dupilumab with concomitant topical corticosteroids in children 6 to 11 years old with severe atopic dermatitis: a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1282–1293. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.06.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wollenberg A, Beck LA, Blauvelt A, et al. Laboratory safety of dupilumab in moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: results from three phase III trials (LIBERTY AD SOLO 1, LIBERTY AD SOLO 2, LIBERTY AD CHRONOS) Br J Dermatol. 2020;182:1120–1135. doi: 10.1111/bjd.18434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Paller AS, Wollenberg A, Siegfried E, et al. Laboratory safety of dupilumab in patients aged 6–11 years with severe atopic dermatitis: results from a phase III clinical trial. Pediatr Drugs. 2021;23:515–527. doi: 10.1007/s40272-021-00459-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Siegfried EC, Bieber T, Simpson EL, et al. Effect of dupilumab on laboratory parameters in adolescents with atopic dermatitis: results from a randomized, placebo-controlled, phase 3 clinical trial. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2021;22:243–255. doi: 10.1007/s40257-020-00583-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Qualified researchers may request access to study documents (including the clinical study report, study protocol with any amendments, blank case report form and statistical analysis plan) that support the methods and findings reported in this manuscript. Individual anonymised participant data will be considered for sharing once the product and indication have been approved by a regulatory body, if there is legal authority to share the data and there is not a reasonable likelihood of participant re-identification. Submit requests to https://vivli.org/.