Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To compare cardiac computed tomography (CT) with invasive coronary angiography (ICA) as the initial strategy in patients with diabetes and stable chest pain.

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS

This prespecified analysis of the multicenter DISCHARGE trial (NCT02400229) in 16 European countries was performed in patients with stable chest pain and intermediate pretest probability of coronary artery disease. The primary end point was a major adverse cardiac event (MACE) (cardiovascular death, nonfatal myocardial infarction, or stroke), and the secondary end point was expanded MACE (including transient ischemic attacks and major procedure-related complications).

RESULTS

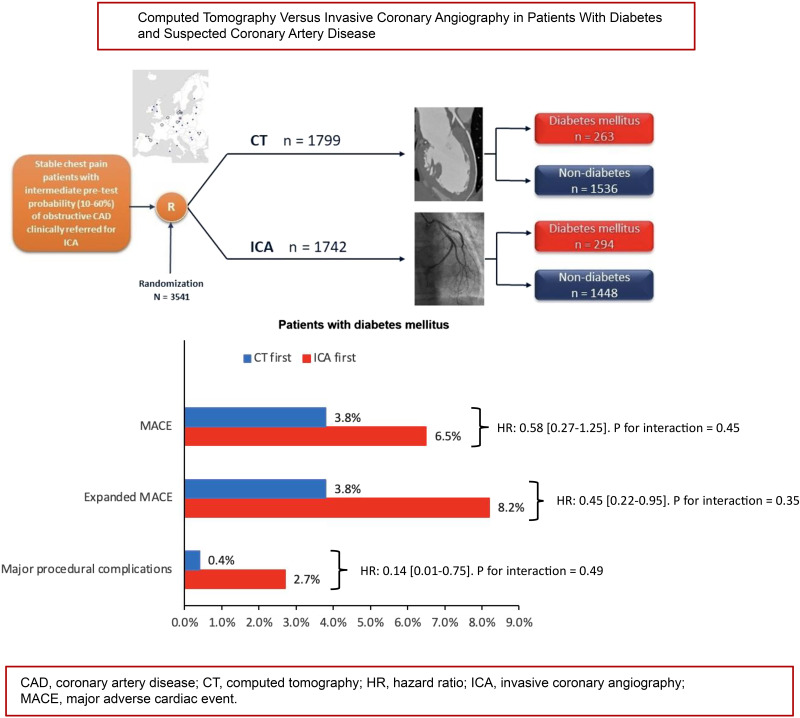

Follow-up at a median of 3.5 years was available in 3,541 patients of whom 557 (CT group n = 263 vs. ICA group n = 294) had diabetes and 2,984 (CT group n = 1,536 vs. ICA group n = 1,448) did not. No statistically significant diabetes interaction was found for MACE (P = 0.45), expanded MACE (P = 0.35), or major procedure-related complications (P = 0.49). In both patients with and without diabetes, the rate of MACE did not differ between CT and ICA groups. In patients with diabetes, the expanded MACE end point occurred less frequently in the CT group than in the ICA group (3.8% [10 of 263] vs. 8.2% [24 of 294], hazard ratio [HR] 0.45 [95% CI 0.22–0.95]), as did the major procedure-related complication rate (0.4% [1 of 263] vs. 2.7% [8 of 294], HR 0.30 [95% CI 0.13 – 0.63]).

CONCLUSIONS

In patients with diabetes referred for ICA for the investigation of stable chest pain, a CT-first strategy compared with an ICA-first strategy showed no difference in MACE and may potentially be associated with a lower rate of expanded MACE and major procedure-related complications.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

The incidence of diabetes is increasing worldwide, with cardiovascular disease representing the leading cause of morbidity and mortality (1). Patients with diabetes have up to two times as high a risk of developing cardiovascular disease than patients without diabetes (2,3). Moreover, diabetes is associated with a higher incidence of complex coronary artery disease (CAD), including left main or multivessel disease, calcified plaques, and high-risk anatomy (4,5). Diabetes is associated with progression of CAD, doubling cardiovascular risk and reducing average life expectancy by 4–6 years (6).

The reference standard for diagnosing obstructive CAD is invasive coronary angiography (ICA), which has the advantage of allowing coronary revascularization to be performed in the same session as the ICA. However, the International Study of Comparative Health Effectiveness With Medical and Invasive Approaches (ISCHEMIA) found that compared with noninvasive (conservative) management, invasive management did not improve clinical outcomes in patients with diabetes and CAD (7,8). Rare, but serious procedural complications during ICA include cardiovascular death and myocardial infarction (9). Computed tomography (CT) has emerged as an accurate and safe first-line imaging test compared with stress testing or ICA for the diagnosis of obstructive CAD in symptomatic patients with diabetes and chest pain (10,11). In the Prospective Multicenter Imaging Study for Evaluation of Chest Pain (PROMISE), a CT strategy reduced the risk of cardiovascular death and myocardial infarction in patients with diabetes (1.1% vs. 2.6%) but not in those without diabetes (1.4% vs. 1.3%) compared with a functional testing strategy at 3.5 years of follow-up (11). There is little randomized evidence comparing a CT-first with an ICA-first strategy for patients with diabetes referred for ICA for the investigation of stable chest pain. The recently published Diagnostic Imaging Strategies for Patients With Stable Chest Pain and Intermediate Risk of Coronary Artery Disease (DISCHARGE) trial compared CT and ICA and found that major adverse cardiac events (MACE) were similar in both strategies and that major procedure-related complications were lower with the CT-first strategy (12). The objective of the current analysis was to evaluate the comparative effectiveness and safety of CT versus ICA in the investigation of patients with diabetes with stable chest pain referred for ICA.

Research Design and Methods

Trial Design and Patients

Patients with stable chest pain and at least 30 years of age who were clinically referred for ICA were included in this investigator-led, prospective, pragmatic, multicenter, randomized controlled trial and were available for this prespecified subgroup analysis (12). Details of enrollment, randomization, overall trial design methods and main results have been previously published (12,13). Briefly, symptomatic patients referred for ICA with an intermediate pretest probability (10–60%) of CAD were randomized to either CT or ICA as the first-line test for diagnostic investigation. Clinical referral for ICA followed European Society of Cardiology guidelines during the trial (14,15). Exclusion criteria were hemodialysis treatment, no sinus rhythm, pregnancy, or other relevant medical conditions that represented concern for study inclusion. The study was conducted at 26 sites in 16 European countries, and patients were recruited from October 2015 to April 2019. Written informed consent was provided by all patients, and ethical approval was obtained from the ethics committee at Charité–Universitätsmedizin Berlin as the coordinating center, the German Federal Office for Radiation Protection, and the local or national ethics committees for each site participating in the trial. The trial was prospectively registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT02400229) on 15 January 2015. Patients were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to undergo either CT or ICA with the use of a web-based system to ensure concealment of group assignments after eligibility criteria had been checked. Block randomization used computer-generated and randomly permuted blocks of 4, 6, or 8 stratified according to center and the patient’s sex with central assignment. A patient flowchart is presented in Supplementary Fig. 1.

Obstructive CAD was defined as ≥50% coronary artery luminal diameter stenosis. High-risk anatomy CAD was defined as three-vessel CAD, left main coronary artery stenosis, proximal left anterior descending coronary artery stenosis, or any combination of these. As per the pragmatic trial design, while clinical sites were provided with management recommendations for contemporary treatment of cardiovascular disease (15), management decisions were made by local heart team members and referring physicians at each study site. For both randomization strategies, patients without obstructive CAD were discharged back to the referring physician, and patients with obstructive CAD were managed according to guidelines (16,17). The physical component summary of the 12-Item Short Form Health Survey (version 2) was recorded at the time of randomization.

Outcomes

The primary study end point of effectiveness, MACE, was prespecified and defined as cardiovascular death, nonfatal myocardial infarction, or nonfatal stroke. Patients were followed up using a predefined structured questionnaire 48 h following the last study-related test, after 1 year, and finally for a maximum of up to 5 years for assessment of the primary study end point as well as detailed clinical information. Possible adverse cardiovascular events were adjudicated by independent assessors blinded to study group assignment.

Key secondary end points of effectiveness were an expanded MACE composite, including cardiovascular death, nonfatal myocardial infarction, nonfatal stroke, transient ischemic attack (TIA), and major procedure-related complications, and major procedure-related complications alone. Major procedure-related complications were defined as complications occurring during or within 48 h after a procedure (CT or ICA or related tests) and included death, nonfatal myocardial infarction, nonfatal stroke, further complications prolonging hospital admission by at least 24 h, dissection (coronary, aortic), cardiogenic shock, cardiac tamponade, retroperitoneal bleeding, cardiac arrhythmia (ventricular tachycardia, ventricular fibrillation), and cardiac arrest. Complications were classified according to the NCDR CathPCI Registry v4.4 Coder’s Data Dictionary. We did not differentiate patients with type 1 and type 2 diabetes in statistical analysis because of the low number of participants with type 1 disease in the trial cohort, precluding statistical comparisons. MACE and extended MACE were the effectiveness outcomes, and major procedure-related complications were the safety outcome.

Statistical Analysis

All analyses were performed as an intention-to-treat population. Categorical variables were reported as numbers and percentages. Continuous variables were reported as mean ± SD or median with interquartile range (IQR), as appropriate. Independent sample Student t test was used to compare continuous variables that satisfied normality, while nonnormally distributed continuous variables were analyzed using the Mann-Whitney U test. Categorical variables were compared using χ2 test (or Fisher exact test as appropriate), and ordinal variables were compared using linear-by-linear association testing. Cumulative curves of MACE and expanded MACE were calculated using Kaplan-Meier estimates.

Primary and secondary outcomes were analyzed using subdistribution Cox proportional hazards models with Fine and Gray adjustment for competing risks. Noncardiovascular death and unknown causes of death were considered as competing-risk events (as was cardiovascular death for nonfatal outcomes). A multivariable model was used to evaluate the heterogeneity of CT and ICA effects across patients with and without diabetes. The model included the following variables: diabetes/no diabetes, randomization groups (CT vs. ICA), and the interaction term CT/ICA ∗ diabetes. A P value for interaction <0.05 was considered significant. If a significant interaction was observed, further evaluation across the two predefined subgroups (patients with and without diabetes) was performed, adjusting for multiplicity to avoid type I error (Bonferroni factor 2 for two groups). Results were reported as hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% CIs. The Schoenfeld test was used to confirm the proportionality assumption required for Cox proportional hazards modeling. Follow-up was defined as the period from randomization until the occurrence of an outcome or otherwise censored at death (noncardiovascular events and unknown causes of death), loss to follow-up, or end of study. Although a patient could experience more than one MACE component, each patient was assessed until the occurrence of the first event. Binary logistic regression analysis was performed to evaluate the secondary end point of major procedure-related complications. A multivariable model was used to evaluate whether the odds ratio (OR) differed between the CT and ICA groups among patients with diabetes. Interaction and intervention between diabetes groups was also included. ORs and 95% CIs were estimated.

The statistical analysis was performed using SAS 9.4 software (SAS Institute Inc.), SPSS for Windows version 26 (IBM Corporation), and the statistical programming language R version 4.0.3. Statistical significance was assumed for a two-sided P < 0.05.

Data and Resource Availability

A data sharing statement provided by the authors is available in the Supplementary Material.

Results

Baseline Patient Characteristics

Among 3,561 eligible patients from the main analysis cohort, 3,541 with complete data on diabetes were included in this prospectively defined subgroup analysis. Baseline characteristics of the study population stratified by presence of diabetes and initial test strategy (CT vs. ICA) are presented in Table 1 (additional patient characteristics can be found in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2). Diabetes was reported in 557 of 3,541 (15.7%) patients (CT group n = 263 vs. ICA group n = 294), and no diabetes in 2,984 of 3,541 (84.3%) patients (CT group n = 1,536 vs. ICA group n = 1,448). The subgroup analysis included 1,990 women (56.2%), with the distribution among women being nonsignificant between those with diabetes versus without diabetes and for the CT strategy versus ICA strategy. Mean age was higher in patients with diabetes (62.9 ± 8.9 years) versus without diabetes (59.6 ± 10.2 years, P < 0.001), which also held true for subgroups with initial CT- versus ICA-first strategies. Arterial hypertension (diabetes 81.7% vs. without diabetes 55.8%), hyperlipidemia (diabetes 63.7% vs. without diabetes 45.1%), peripheral artery disease (diabetes 2.9% vs. without diabetes 1.1%), and TIAs (diabetes 3.8% vs. without diabetes 1.5%) were more frequent in patients with diabetes. Patients with diabetes had a higher mean BMI than patients without diabetes (31.1 ± 5.8 vs. 28.4 ± 4.92 kg/m2, P < 0.001) and a lower physical component score (42.0 ± 9.35 vs. 44.1 ± 9.12, P < 0.001).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics by diabetes group and initial test strategy

| Diabetes | No diabetes | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Diabetes (n = 557) | No diabetes (n = 2,984) | P | CT (n = 263) | ICA (n = 294) | P | CT (n = 1,536) | ICA (n = 1,448) | P |

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 62.9 (9.0) | 59.6 (10.2) | <0.001 (TT) | 62.5 (9.0) | 63.3 (8.9) | 0.27 (TT) | 59.8 (10.4) | 59.4 (10.1) | 0.28 (TT) |

| Sex, n (%) | 0.74 (χ) | 0.62 (χ) | 0.78 (χ) | ||||||

| Female | 309 (55.5) | 1,681 (56.3) | 143 (54.4) | 166 (56.5) | 869 (56.6) | 812 (56.1) | |||

| Male | 248 (44.5) | 1,303 (43.7) | 120 (45.6) | 128 (43.5) | 667 (43.4) | 636 (43.9) | |||

| Pretest probability, mean ± SD‡ | 39.6 ± 10.4 | 37.3 ± 10.8 | <0.001 (TT) | 39.2 ± 10.6 | 40.0 ± 10.2 | 0.36 (TT) | 37.1 ± 10.9 | 37.5 ± 10.7 | 0.26 (TT) |

| Type of chest pain, n (%) | 0.91 (χ) | 0.25 (χ) | 0.06 (χ) | ||||||

| Typical angina | 76 (13.6) | 426 (14.3) | 33 (12.5) | 43 (14.6) | 198 (12.9) | 228 (15.7) | |||

| Atypical angina | 264 (47.4) | 1,377 (46.1) | 122 (46.4) | 142 (48.3) | 716 (46.6) | 661 (45.6) | |||

| Nonanginal chest pain | 204 (36.6) | 1,100 (36.9) | 100 (38.0) | 104 (35.4) | 575 (37.4) | 525 (36.3) | |||

| Other chest pain | 13 (2.3) | 81 (2.7) | 8 (3.0) | 5 (1.7) | 47 (3.1) | 34 (2.3) | |||

| Cardiovascular risk factors, n (%) | |||||||||

| Arterial hypertension | 455 (81.7) | 1,665 (55.8) | <0.001 (χ) | 212 (80.6) | 243 (82.7) | 0.53 (χ) | 890 (57.9) | 775 (53.5) | 0.01 (χ) |

| Hyperlipidemia | 355 (63.7) | 1,346 (45.1) | <0.001 (χ) | 164 (62.4) | 191 (65.0) | 0.52 (χ) | 707 (46.0) | 639 (44.1) | 0.30 (χ) |

| Peripheral artery disease | 16 (2.9) | 32 (1.1) | 0.002 (χ) | 5 (1.9) | 11 (3.7) | 0.19 (χ) | 19 (1.2) | 13 (0.9) | 0.37 (χ) |

| Valve disease | 23 (4.1) | 166 (5.6) | 0.19 (χ) | 11 (4.2) | 12 (4.1) | 0.95 (χ) | 83 (5.4) | 83 (5.7) | 0.67 (χ) |

| Stroke | 20 (3.6) | 71 (2.4) | 0.13 (χ) | 10 (3.8) | 10 (3.4) | 0.8 (χ) | 37 (2.4) | 34 (2.3) | 0.91 (χ) |

| TIA | 21 (3.8) | 46 (1.5) | <0.001 (χ) | 9 (3.4) | 12 (4.1) | 0.68 (χ) | 23 (1.5) | 23 (1.6) | 0.84 (χ) |

| Prolonged ischemic neurological deficit | 0 (0) | 5 (0.2) | 0.99 (Fis) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | NA | 2 (0.1) | 3 (0.2) | 0.37 (Fis) |

| Carotid artery disease | 20 (3.6) | 62 (2.1) | 0.04 (χ) | 9 (3.4) | 11 (3.7) | 0.84 (χ) | 29 (1.9) | 33 (2.3) | 0.45 (χ) |

| Family history of premature CAD (female) | 100 of 309 (32.4) | 558 of 1,681 (33.2) | 0.78 (χ) | 43 of 143 (30.1) | 57 of 166 (34.3) | 0.42 (χ) | 278 of 869 (32.0) | 280 of 812 (34.5) | 0.29 (χ) |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 31 (5.6) | 122 (4.1) | 0.14 (χ) | 15 (5.7) | 16 (5.4) | 0.89 (χ) | 57 (3.7) | 65 (4.5) | 0.28 (χ) |

| Cigarette smoking, n (%) | 0.10 (χ) | 0.18 | 0.40 | ||||||

| Current | 84 (15.1) | 558 (18.7) | 51 (19.4) | 33 (11.2) | 291 (18.9) | 267 (18.4) | |||

| Former | 189 (33.9) | 929 (31.1) | 80 (30.4) | 109 (37.1) | 457 (29.8) | 472 (32.6) | |||

| Never | 268 (48.1) | 1,401 (47.0) | 123 (46.8) | 145 (49.3) | 738 (48.0) | 663 (45.8) | |||

| Missing data | 16 (2.9) | 96 (3.2) | NA | 9 (3.4) | 7 (2.4) | 50 (3.3) | 46 (3.2) | ||

| BMI, kg/m2, mean ± SD | 31.1 ± 5.8 | 28.4 ± 4.9 | <0.001 (TT) | 31.2 ± 6.2 | 31.0 ± 5.5 | 0.68 (TT) | 28.5 ± 4.9 | 28.3 ± 4.9 | 0.29 (TT) |

| Missing data, n (%) | 16 (2.9) | 77 (2.6) | NA | 11 (4.2) | 5 (1.7) | 48 (3.1) | 29 (2.0) | ||

χ, χ2 test; Fis, Fisher exact test; LL, linear-by-linear association test; NA, not applicable; TT, independent sample t test.

Calculated pretest probability of CAD obtained using an automated calculation tool, integrated into a web-based system of the electronic case report forms, which applied an updated model of the Diamond and Forrester method using patient age, sex, and the type of stable chest pain.

Initial Strategy Findings and Subsequent Management

Supplementary Table 3 shows initial test findings by CT or ICA, frequency of CT and ICA performed during initial management, procedural details, and revascularization in patients with and without diabetes. In both patient groups, CT was associated with a significantly shorter time from enrollment to initial test (3 vs. 8 days for patients with diabetes [P < 0.001] and 4 vs. 12 days for patients without diabetes [P < 0.001]). In the ICA group, a higher proportion of patients with diabetes had angiographic evidence of obstructive CAD (112 [38.1%] vs. 94 [35.7%], P < 0.001). The proportion of patients who had a percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) during initial management was similar in the CT and ICA groups. In contrast, in patients without diabetes, the proportion of patients treated by PCI was higher in the ICA strategy, although obstructive CAD was more frequent in patients examined by CT.

Primary Outcomes

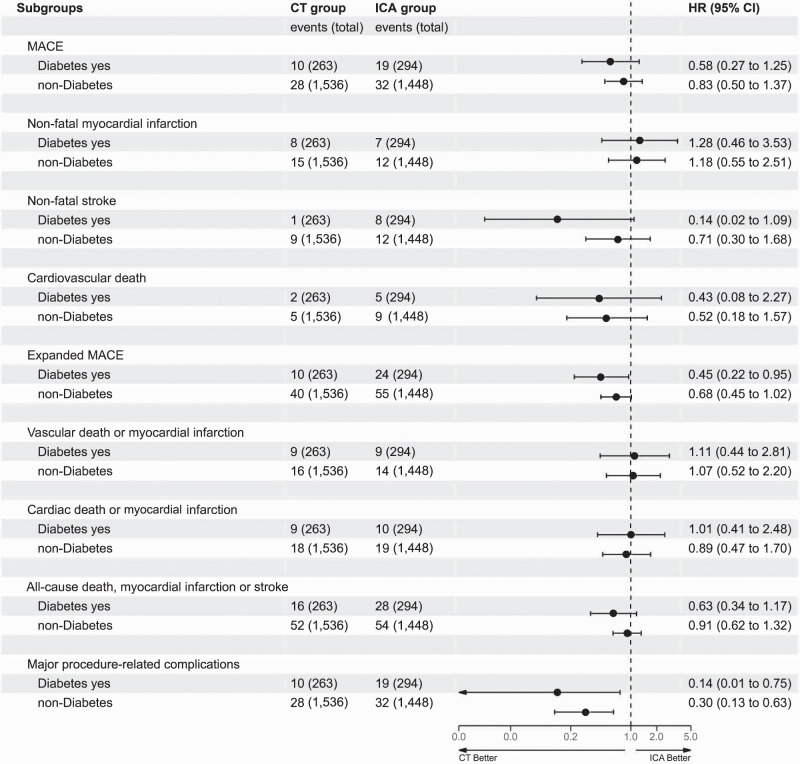

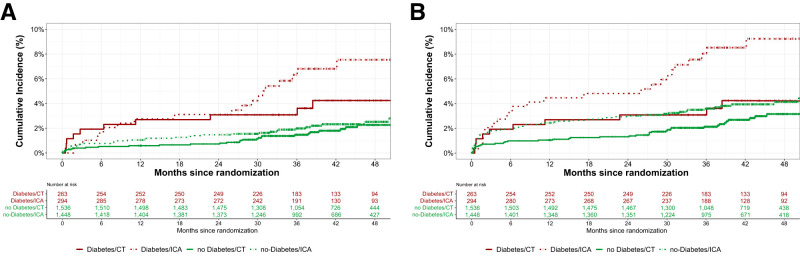

At a median follow-up of 3.5 years (IQR 2.9–4.2), the primary end point MACE occurred in 29 patients (5.2%) with diabetes and 60 (2.0%) without diabetes (HR 2.47 [95% CI 1.56–3.91]) (Table 2 and Supplementary Table 4), with no significant interaction between diabetes groups and initial CT versus initial ICA strategy on MACE (P for interaction = 0.45). The HR for MACE with the CT strategy compared with the ICA strategy was 0.58 (95% CI 0.27–1.25) for patients with diabetes and 0.83 (95% CI 0.50–1.37) for patients without diabetes (Fig. 1). Figure 2 presents the time-to-event curves for MACE (Fig. 2A) and expanded MACE (Fig. 2B), and cumulative incidence of MACE and expanded MACE during follow-up is presented in Supplementary Tables 3 and 4. The results for the individual components of the primary end point MACE are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Primary and secondary end points adjusted for diabetes and initial testing strategy (CT vs. ICA)

| Diabetes (n = 557) | No diabetes (n = 2,984) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| End point | CT (n = 263) | ICA (n = 294) | Effect size* (95% CI) | CT (n = 1,536) | ICA (n = 1,448) | Effect size* (95% CI) | P for interaction† |

| MACE | 10 (3.8) | 19 (6.5) | 0.58 (0.27–1.25) | 28 (1.8) | 32 (2.2) | 0.83 (0.50–1.37) | 0.45 |

| Nonfatal myocardial infarction | 8 (3.0) | 7 (2.4) | 1.28 (0.46–3.53) | 15 (1.0) | 12 (0.8) | 1.18 (0.55–2.51) | 0.89 |

| Nonfatal stroke | 1 (0.4) | 8 (2.7) | 0.14 (0.02–1.09) | 9 (0.6) | 12 (0.8) | 0.71 (0.30–1.68) | 0.15 |

| Cardiovascular death | 2 (0.8) | 5 (1.7) | 0.43 (0.08–2.27) | 5 (0.3) | 9 (0.6) | 0.52 (0.18–1.57) | 0.86 |

| Expanded MACE | 10 (3.8) | 24 (8.2) | 0.45 (0.22–0.95) | 40 (2.6) | 55 (3.8) | 0.68 (0.45–1.02) | 0.35 |

| Vascular death or myocardial infarction | 9 (3.4) | 9 (3.1) | 1.11 (0.44–2.81) | 16 (1.0) | 14 (1.0) | 1.07 (0.52–2.20) | 0.94 |

| Cardiac death or myocardial infarction | 9 (3.4) | 10 (3.4) | 1.01 (0.41–2.48) | 18 (1.2) | 19 (1.3) | 0.89 (0.47–1.70) | 0.83 |

| All-cause death, myocardial infarction, or stroke | 16 (6.1) | 28 (9.5) | 0.63 (0.34–1.17) | 52 (3.4) | 54 (3.7) | 0.91 (0.62–1.32) | 0.33 |

| Major procedure-related complications during initial management, OR (95% CI)‡ | 1 (0.4) | 8 (2.7) | 0.14 (0.01–0.75) | 8 (0.5) | 25 (1.7) | 0.30 (0.13–0.63) | 0.49 |

Data are n (%) unless otherwise indicated.

Effect sizes are HRs unless otherwise indicated.

P value for group ∗ center interaction.

A complete list of all major procedure-related complications and their relationships is provided in Supplementary Tables 3 and 4. MACE included cardiovascular death, nonfatal myocardial infarction, or nonfatal stroke, and expanded MACE included cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, stroke, TIA, or major procedure-related complication.

Figure 1.

Forest plot of interactions between patients with and without diabetes and initial testing strategy (CT vs. ICA) for MACE and expanded MACE calculated using subdistribution Cox proportional hazards models with Fine and Gray adjustment for competing risks. Nonfatal stroke and major procedure-related complications occurred less frequently in patients with diabetes in the CT group.

Figure 2.

Time-to-event curves for MACE and expanded MACE end points. A: At a median follow-up of 3.5 years, no interactions were found between patients with and without diabetes and initial testing strategy (CT vs. ICA) for MACE (P for interaction = 0.45). B: At a median follow-up of 3.5 years, no interactions were found between patients with and without diabetes and initial testing strategy (CT vs. ICA) for expanded MACE. However, the HRs for expanded MACE occurred less frequently in patients with diabetes in the CT group compared with the ICA group (0.45 [95% CI 0.22–0.95]) compared with patients without diabetes (0.68 [95% CI 0.45–1.02]).

Secondary Outcomes

The expanded MACE composite of cardiovascular death, nonfatal myocardial infarction, nonfatal stroke, TIA, or major procedure-related complication occurred with similar frequency in patients with and without diabetes (Table 2 and Supplementary Table 5). The interaction between diabetes and study group for the expanded MACE composite was not significant (P for interaction = 0.35). We performed a further subgroup analysis stratified by diabetes. In patients with diabetes, the expanded MACE composite end point occurred less frequently in the CT group than in the ICA group (3.8% [10 of 263] vs. 8.2% [24 of 294], HR 0.45 [95% CI 0.22–0.95]) (Table 2). In patients without diabetes, the expanded MACE composite was similar in the CT and ICA groups (Table 2). Rates of secondary additional composite end points, such as vascular death or myocardial infarction and cardiac death or myocardial infarction, were similar for the two test strategies in patients with and without diabetes (Table 2).

Major procedure-related complications occurred with similar frequency in patients with and without diabetes (Table 2 and Supplementary Table 6). We found no significant interaction between diabetes and study group for major procedure-related complications (P for interaction = 0.49). In patients with diabetes and without diabetes, the risk of having a major procedure-related complication was lower in the CT group than in the ICA group (0.4% [1 of 263] vs. 2.7% [8 of 294], HR 0.14 [95% CI 0.01–0.75] and 0.5% [8 of 1,536] vs. 1.7% [25 of 1448], HR 0.30 [95% CI 0.13–0.63]). Most major procedure-related complications were observed in relation to ICA procedures, and the frequency was highest in patients with diabetes undergoing ICA with PCI (Supplementary Table 7).

Conclusions

This prespecified subgroup analysis of the DISCHARGE trial, a prospective, multicenter, European study, aimed to assess the efficacy and safety of a CT-first strategy compared with an ICA-first strategy in patients with stable chest pain and diabetes who were referred for ICA because of suspected obstructive CAD. The analysis, which included 3,541 patients, yielded several noteworthy findings. First, there was no statistically significant difference in the occurrence of MACE at a median follow-up of 3.5 years between the CT-first and ICA-first strategies in patients with diabetes. This finding suggests that initiating the diagnostic pathway with CT is not inferior to proceeding directly to ICA in terms of MACE rates for symptomatic patients with diabetes referred for ICA. Second, the analysis demonstrated that the expanded MACE composite, which included MACE plus major procedure-related complications and TIAs, occurred less frequently in patients with diabetes who underwent the CT-first strategy. Using CT as the initial diagnostic modality may be associated with a reduced risk of adverse cardiovascular events in this specific patient population. Third, the analysis revealed a lower rate of major procedure-related complications in both patients with and without diabetes who underwent the CT-first strategy compared with those in the ICA-first group.

The strengths of the DISCHARGE trial lie in its pragmatic design, which reflects real-world clinical practice, and the high completeness of follow-up, ensuring robust data collection. Also of note, we did not find higher nondiagnostic CT scan rates in patients with diabetes compared with those without diabetes. Additionally, the trial aimed to achieve equal representation of both men and women, a crucial aspect for contemporary cardiac trials that enhances the generalizability and comprehensiveness of the findings across sexes (18). Although current chest pain guidelines assign cardiac CT as a class 1 indication for patients with stable chest pain, patients with diabetes are not explicitly addressed (19), and there is little randomized controlled trial evidence of the comparative effectiveness and safety of cardiac CT in patients with diabetes referred for ICA.

CAD is a major cause of mortality in patients with diabetes, and most adult patients are at a high or very high risk for future cardiovascular events (20). According to cardiovascular prevention clinical practice guidelines of the European Society of Cardiology, patients with at least a 10-year history of diabetes are at very high risk for future cardiovascular events if they have target organ damage and at a high risk for future cardiovascular events if they have no target organ damage (4,6). Young patients with diabetes duration of <10 years and no other risk factors are considered at moderate risk of developing future cardiovascular events. The influence of diabetes on MACE rates in patients initially referred for ICA has not yet been widely investigated in large multicenter populations. The PROMISE trial investigators compared CT with functional testing and demonstrated that in patients with diabetes and low pretest probability of obstructive CAD, a CT strategy results in fewer adverse cardiovascular outcomes compared with a functional test strategy, and they suggested that CT be considered as the initial diagnostic modality in patients with diabetes and chest pain (11). The Scottish Computed Tomography of the Heart Trial (SCOT-HEART) investigators compared CT with standard care, randomizing 4,146 patients with stable chest pain, 11% of whom had diabetes, to standard care with or without CT (21). Patients with diabetes (n = 444) had a significantly lower risk of myocardial infarction and cardiac mortality with CT-guided management compared with standard of care (3.1% vs. 7.7%, HR 0.36 [95% CI 0.15–0.87]). Our findings add to this existing evidence by suggesting that cardiac CT may become the primary imaging modality for the investigation of patients with diabetes and stable chest pain while improving patient outcomes and safety relative to other strategies.

We acknowledge some limitations of the DISCHARGE trial. The awareness of group assignments among patients and investigators may have introduced bias into the reporting of outcomes, potentially favoring the CT-first strategy. Moreover, the trial allowed for variations in management decisions based on European guidelines, which may have led to heterogeneity in individual approaches but also increased external validity. The low event rate observed in the trial suggests that further research with extended follow-up periods might provide additional insights into a CT-first strategy in stable, symptomatic patients with diabetes.

In conclusion, this subgroup analysis of the DISCHARGE trial provides valuable insights into the use of cardiac CT as the initial diagnostic modality in patients with diabetes and stable chest pain referred for ICA. The results suggest that a CT-first strategy is noninferior to an ICA-first strategy in terms of MACE rates but may offer potential benefits in terms of reduced expanded MACE and major procedure-related complications. These findings contribute to the growing evidence supporting the application of CT in patients with diabetes suspected of having obstructive CAD. However, additional research with longer follow-up periods is warranted to confirm and expand these observations.

This article contains supplementary material online at https://doi.org/10.2337/figshare.24025761.

Article Information

Funding. This study was funded by the European Union FP7 Health Framework Program 2007–2013 grant EC-GA 603266 to M.D.; Berlin Institute of Health (from Digital Health Accelerator); British Heart Foundation (Centre of Research Excellence) grant RE/18/6/34217; Rigshospitalet, University of Copenhagen; Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft Radiomics Priority Program grants DE 1361/19-1 [428222922] and 20-1 [428223139] in SPP2177/1); and graduate program BIOQIC grant GRK 2260/1 [289347353]. The DISCHARGE trial is associated with and endorsed by DZHK (German Centre for Cardiovascular Research) and we greatly acknowledge this collaborative network.

Duality of Interest. T.B. received grants from the Romanian Ministry of European Funds, the Romanian Government, and the European Union. K.F.K. received grants from AP Møller og hustru; Chastine McKinney Møllers Fond; Danish Heart Foundation; the Danish Agency for Science, Technology and Innovation by The Danish Council for Strategic Research; and the Health Insurance Company Denmark and an unrestricted research grant from Canon Medical Corporation and GE Healthcare. E.Z. received grants from Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft. J.K. received personal fees from AstraZeneca and GE Healthcare. C.B. received grants to his institution from AstraZeneca, Abbott Vascular, GlaxoSmithKline, HeartFlow, Menarini, Novartis, and Siemens and other financial or nonfinancial interests from the British Heart Foundation. N.R. is a principal investigator for a grant from the German Ministry of Education and Research. B.M. received personal fees from Biotronik, Medtronic, and Abbott and a grant from Boston Scientific. I.B. receive grants from the Romanian Ministry of European Funds, Romanian Government, and European Union. M.Kr. received grants to his institution from the National Science Center (Poland) and reports patents EP3157444B1 (granted), WO2015193847A1 (pending), and WO2013060883A4 (pending). M.R. received a grant from Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft. M.D. received grant support from the German Research Foundation; received funding from the Berlin University Alliance and the Digital Health Accelerator of the Berlin Institute of Health; is an editor for Springer Nature; receives other from Hands-on Cardiac CT Course (https://www.ct-kurs.de); receives funding through institutional research agreements with Siemens, General Electric, Philips, and Canon; holds a patent on fractal analysis of perfusion imaging (jointly with Florian Michallek, PCT/EP2016/071551 and USPTO 2021 10,991,109 approved); was a European Society of Radiology research chair (2019–2022); and is publications chair (2022–2025) for the European Society of Radiology. P.E.S. received consulting fees from Novo Nordisk outside the submitted work. G.Š. received payment or honoraria for lectures from Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer (Sanofi Aventis), Berlin Chemie Menarini, Baltic (Servier Pharma), and IQVIA; travel support from Servier and Novartis; participated on a data safety monitoring committee for Boehringer Ingelheim; and is a member of the Lithuanian Society of Cardiology, Lithuanian Heart Association, and Lithuanian Hypertension Society. M.G. received payment or honoraria to his institution for lectures from Bayer, Siemens, Bracco, and the German Roentgen Society and reported unpaid membership on a scientific committee for European Society for Cardiovascular Radiology and working group for the German Roentgen Society. J.K. received payment or honoraria for lectures from GE Healthcare, Merck, Lundbeck, and Boehringer Ingelheim; speaker’s fees from Bayer, Boehringer-Ingelheim, and Pfizer; and other financial and nonfinancial interests from the European Society of Cardiology. J.D.D. is an associate editor for Radiology, a member for the editorial board for Radiology and Cardiothoracic Imaging, and an associate editor for the Quarterly Journal of Medicine, all nonpaid, and is a coauthor of book chapters published by Elsevier.

The opinions expressed in this article are the authors’ own and do not represent the views of the European Society of Radiology Research.

Author Contributions. T.B., V.W., B.S., K.F.K., P.D., J.R.-P., A.E., J.V., G.Š., N.Č.A., M.G., I.D., G.D., E.Z., C.Kę., R.V., M.Fr., M.I.-S., F.P., J.K., R.F., S.S., C.B., L.S., B.R., N.R., C.Ku., K.S.H., J.M.-N., B.M., P.E.S., I.B., C.O., F.X.V., L.Z., M.H., A.J., F.A., M.W., N.M., I.L., E.T., M.L., M.Kr., M.S., M.Ma., D.K., G.F., M.P., V.G.R., T.D., C.D., M.Me., M.Fi., M.Bou., C.Kr., R.A., S.K., B.G.d.B., A.R., M.Ká., J.D.H., I.R., S.R., H.C.C., L.G., L.L., R.Ho., A.E.N., R.Ha., S.F., M.Mo., L.M.S.-H., K.N., H.D., M.R., J.D., M.E., M.Bos., P.M., J.D.D., and M.D. contributed to the data collection and review and interpretation of the findings, provided critical revisions of the manuscript for important intellectual content, and gave final approval of the final version of the manuscript to be published. T.B., V.W., K.F.K., M.Bos., and M.D. contributed to the analysis and interpretation of the data. T.B., V.W., J.D.D., and M.D. drafted the manuscript. L.M.S.-H. and P.M. contributed statistical expertise. R.Ha., J.D.D., and M.D. contributed to the study concept and design. M.D. is the guarantor of this work and, as such, had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Funding Statement

This study was funded by the European Union FP7 Health Framework Program 2007–2013 grant EC-GA 603266 to M.D.; Berlin Institute of Health (from Digital Health Accelerator); British Heart Foundation (Centre of Research Excellence) grant RE/18/6/34217; Rigshospitalet, University of Copenhagen; Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft Radiomics Priority Program grants DE 1361/19-1 [428222922] and 20-1 [428223139] in SPP2177/1); and graduate program BIOQIC grant GRK 2260/1 [289347353]. The DISCHARGE trial is associated with and endorsed by DZHK (German Centre for Cardiovascular Research) and we greatly acknowledge this collaborative network.

Footnotes

Clinical trial reg. no. NCT02400229, clinicaltrials.gov

T.B. and V.W. contributed equally as first authors.

J.D.D. and M.D. contributed equally as last authors.

References

- 1. Cheng YJ, Imperatore G, Geiss LS, et al. Trends and disparities in cardiovascular mortality among U.S. adults with and without self-reported diabetes, 1988–2015. Diabetes Care 2018;41:2306–2315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Nanayakkara N, Curtis AJ, Heritier S, et al. Impact of age at type 2 diabetes mellitus diagnosis on mortality and vascular complications: systematic review and meta-analyses. Diabetologia 2021;64:275–287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cowie CC, Casagrande SS, Geiss LS, et al., Eds. Diabetes in America. 3rd ed. Bethesda, MD, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, 2018 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cosentino F, Grant PJ, Aboyans V, et al.; ESC Scientific Document Group . 2019 ESC guidelines on diabetes, pre-diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases developed in collaboration with the EASD. Eur Heart J 2020;41:255–323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rana JS, Dunning A, Achenbach S, et al. Differences in prevalence, extent, severity, and prognosis of coronary artery disease among patients with and without diabetes undergoing coronary computed tomography angiography: results from 10,110 individuals from the CONFIRM (COronary CT Angiography EvaluatioN For Clinical Outcomes): an InteRnational Multicenter Registry. Diabetes Care 2012;35:1787–1794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Visseren FLJ, Mach F, Smulders YM, et al.; ESC National Cardiac Societies; ESC Scientific Document Group . 2021 ESC guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice. Eur Heart J 2021;42:3227–3337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Maron DJ, Hochman JS, Reynolds HR, et al.; ISCHEMIA Research Group . Initial invasive or conservative strategy for stable coronary disease. N Engl J Med 2020;382:1395–1407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Newman JD, Anthopolos R, Mancini GBJ, et al. Outcomes of participants with diabetes in the ISCHEMIA trials. Circulation 2021;144:1380–1395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Knuuti J, Wijns W, Saraste A, et al.; ESC Scientific Document Group . 2019 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and management of chronic coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J 2020;41:407–477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kammerlander AA, Mayrhofer T, Ferencik M, et al.; PROMISE Investigators . Association of metabolic phenotypes with coronary artery disease and cardiovascular events in patients with stable chest pain. Diabetes Care 2021;44:1038–1045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sharma A, Coles A, Sekaran NK, et al. Stress testing versus CT angiography in patients with diabetes and suspected coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2019;73:893–902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Maurovich-Horvat P, Bosserdt M, Kofoed KF, et al.; DISCHARGE Trial Group . CT or invasive coronary angiography in stable chest pain. N Engl J Med 2022;386:1591–1602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Napp AE, Haase R, Laule M, et al.; DISCHARGE Trial Group . Computed tomography versus invasive coronary angiography: design and methods of the pragmatic randomised multicentre DISCHARGE trial. Eur Radiol 2017;27:2957–2968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Perk J, De Backer G, Gohlke H, et al.; European Association for Cardiovascular Prevention & Rehabilitation (EACPR); ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines (CPG) . European guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice (version 2012). The Fifth Joint Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and Other Societies on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Clinical Practice (constituted by representatives of nine societies and by invited experts). Eur Heart J 2012;33:1635–1701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Montalescot G, Sechtem U, Achenbach S, et al.; Task Force Members; ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines; Document Reviewers . 2013 ESC guidelines on the management of stable coronary artery disease: the Task Force on the Management of Stable Coronary Artery Disease of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J 2013;34:2949–3003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Scanlon PJ, Faxon DP, Audet AM, et al. ACC/AHA guidelines for coronary angiography. A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Committee on Coronary Angiography). Developed in collaboration with the Society for Cardiac Angiography and Interventions. J Am Coll Cardiol 1999;33:1756–1824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Windecker S, Kolh P, Alfonso F, et al.; Authors/Task Force Members . 2014 ESC/EACTS guidelines on myocardial revascularization: the Task Force on Myocardial Revascularization of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Developed with the special contribution of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (EAPCI). Eur Heart J 2014;35:2541–2619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cho L, Vest AR, O’Donoghue ML, et al.; Cardiovascular Disease in Women Committee Leadership Council . Increasing participation of women in cardiovascular trials: JACC council perspectives. J Am Coll Cardiol 2021;78:737–751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gulati M, Levy PD, Mukherjee D, et al.; Writing Committee Members . 2021 AHA/ACC/ASE/CHEST/SAEM/SCCT/SCMR guideline for the evaluation and diagnosis of chest pain: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2021;78:2218–2261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Nauta ST, Deckers JW, Akkerhuis KM, van Domburg RT. Short- and long-term mortality after myocardial infarction in patients with and without diabetes: changes from 1985 to 2008. Diabetes Care 2012;35:2043–2047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Newby DE, Adamson PD, Berry C, et al.; SCOT-HEART Investigators . Coronary CT angiography and 5-year risk of myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 2018;379:924–933 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]