Summary

Fragmented care delivery is a barrier to improving health system performance worldwide. Investment in meso-level organisations is a potential strategy to improve health system integration, however, its effectiveness remains unclear. In this paper, we provide an overview of key international and Australian integrated care policies. We then describe Collaborative Commissioning - a novel health reform policy to integrate primary and hospital care sectors in New South Wales (NSW), Australia and provide a case study of a model focussed on older person's care. The policy is theorised to achieve greater integration through improved governance (local stakeholders identifying as part of one health system), service delivery (communities perceive new services as preferable to status quo) and incentives (efficiency gains are reinvested locally with progressively higher value care achieved). If effectively implemented at scale, Collaborative Commissioning has potential to improve health system performance in Australia and will be of relevance to similar reform initiatives in other countries.

Keywords: Care coordination, Health system reform, Integrated care

Background

In healthcare, the term ‘silos’ has been borrowed from agriculture to describe physical and non-physical boundaries arising between divisional units of a health system. They often evolve from complex governance structures and disparate financing models. Silo mentality refers to individual or group beliefs that may result in barriers to communication and the development of disjointed work processes.1 Silos are not necessarily accidental occurrences nor are they inherently destructive as they may reduce complexity and allow people to focus on a more constrained set of activities and goals. However, there is potential for silos to impede operational efficiency, staff morale, and consumer satisfaction, leading to failure to optimise productivity and workplace culture.2

National health systems (comprising all organisations, institutions and resources that produce actions whose primary purpose is to improve health)3 are prone to silos. They are governed at federal, regional, and local levels and are shaped by enduring public policies that play an important role in national identity. Examples include the United Kingdom's (UK) National Health Service established in 1948,4 the United States' (US) Medicare health insurance program enacted in 1965,5 and the Australian national public health insurance scheme (Medicare) established in 1975.6 Despite the presence of general taxation funded insurance schemes in these countries, a substantial proportion of their health care systems are governed and funded via other means, including private health insurance, state- or provincially-funded health services, social sector service providers, non-government and charity organisations, and out of pocket costs incurred directly by consumers. Such fragmentation can foster silos with one sector offloading care and costs to another, rather than collaborating to improve efficiency and outcomes across the continuum of care. Consequently, even if investments in one silo (such as the primary health care sector) lead to better coordination and reduced utilisation in another silo (the hospital system), the costs of implementation may not be supported if hospitals cannot directly receive the financial benefits from reduced acute care utilisation.

Overcoming silos through integrated care initiatives is a focus of many health care reforms globally. Valentijn's conceptual framework describes how integration plays complementary roles at the micro (clinical integration), meso (professional and organisational integration) and macro (system integration) levels. Functional elements (e.g. technical factors such as information systems) and normative elements (e.g. preferences and values of actors) influence connectivity between these levels.7 Especially in the US, UK, Europe and New Zealand, there have been multiple reform efforts to address fragmentation and align incentives across the system. Frequently they are supported by meso-level institutions, which are smaller-scale, lower-level social arrangements or units acting as intermediaries between public and private payers and frontline care providers.8 Drawing on a previous rapid evidence review that we conducted, three examples are highlighted in Panel 1.9

Panel 1. Integrated care reform initiatives.

-

•

Bundled payment programs directed at discrete episodes of care such as lower extremity joint replacement have achieved modest reductions in expenditure and improvements in health care quality, mainly in the US and some other countries (UK, Sweden, Portugal, Netherlands, Denmark, New Zealand and Taiwan).10, 11, 12 These programs incentivise organisations to assume responsibility for the cost of care episodes across the continuum (including the hospital, physicians, testing, and post-acute care).

-

•

Accountable Care Organisations (ACOs) and Integrated Care Systems (ICSs) can be thought of as global bundles incentivising provider organisations to care for a population of patients within a set budget with potential to share in both upside gains or losses for spending below or above the budget. In the US, they are associated with modest expenditure reductions, particularly when the ACO is led by independent physician groups rather than hospital-led systems (1.6%–4.9% expenditure reduction).13,14 In the UK, ICSs bring together NHS organisations, local authorities and others to take collective responsibility for planning services, improving health and reducing inequalities across geographical areas. There are currently 42 area-based ICSs, covering populations of around 500,000–3 million people. Similar models have been implemented in other countries, particularly in Germany, Spain, Netherlands and they have been associated with modest improvements in efficiency outcomes.9,15 In our review of 68 models around half of all models reported reductions in costs relative to expenditure benchmark and nine models reported benefits in mortality outcomes. Of 53 models reporting on quality of care improvements were noted in almost all care models, however the study designs were variable in quality.9

-

•

Patient Centred Medical Homes (PCMHs) are primary care models focussed on whole-person, high quality, coordinated care that is supported by a team of health professionals.16 Although funding models are highly varied, government-funded PCMH programs usually provide additional funding and incentives to the primary care system for care coordination and management. A recent systematic review of 78 randomised controlled trials of PCMH interventions (almost all from US, Europe and UK) for chronic disease care found modest improvements in chronic disease severity, health-related quality of life, self-management and hospitalisations.17 One US study found these programs have yielded little or no savings, though arguably they have led to improvements in primary care delivery.18

Integrated care reforms in Australia

Australia ranks highly in overall health system performance, however, successive reviews have found that its state-federal governance and funding structures are inefficient.19 Despite the national Medicare scheme, the health system comprises several other health subsystems managed and funded by different entities. Public hospitals are jointly funded by state, territory and federal governments, but managed by state and territory governments. The private health insurance system mostly supports procedural care delivered in private hospitals and some preventive care such as dental and allied health services.20 At the meso-tier, primary care services are supported by 31 federally funded but independently managed Primary Health Networks (PHNs) while hospital and community services are provided by over 135 Local Hospital Networks (LHNs) of varying size and capacity which are governed by each state and territory. In 2018–2019, 41% of total health system expenditure was spent by the federal government, 27% by state and territory governments, and 32% by non-government sources with around one half of this contributed by individuals as out of pocket costs.21

There have been numerous reform policies over the last 30 years to support integration of care between primary care and hospital systems. Key examples include the co-ordinated care trials in the late 1990s which included pooling of disparate funding sources, introduction of GP and non-GP care coordinators, and a defined client population (9 trials, 16,533 participants and over 2000 GPs). Despite concerted efforts, the national evaluation did not demonstrate improvements in health outcomes and they led to significantly higher health service use and costs, attributed to short time frames and implementation failure, blunt outcome measures to demonstrate change, and high levels of unmet need uncovered.22 Other reform attempts including pay for performance and other funding models, workforce reforms, accreditation interventions, quality improvement programs, and chronic disease self-management programs have similarly struggled to demonstrate sustainable implementation at scale and improvements in health, cost or quality outcomes.23 A key learning from these reforms is the need for meso-level organisational strategies to better align care coordination, fund pooling and commissioning.23

NSW is the most populous state in Australia (∼8 million residents) and has the lowest health expenditure per capita in the country ($7202 per person).21 Recognising the conflicting incentives in the dual funding streams of the primary care system and public hospitals, the NSW Government (NSW Health) has embarked on several iterations of integrated care reform policy (Table 1). Using the accountable care framework - a conceptual framework derived by expert consensus for characterising and assessing integrated care reforms worldwide (Supplementary Table S1)15–we assessed the level of maturity of these policies based on publicly available documents (0 or 1 = zero or low level of maturity and 5—high level of maturity) for each of the five domains (population, outcomes, metrics and learning, payment and incentives, coordinated delivery). Although clearly this assessment is subjective, over 10 years there has been a trend toward increased maturity across these domains for each policy, with population accountability seeing the greatest progress and metrics/learning and payment/incentive reforms the least.

Table 1.

Current NSW integrated care policies rated using the accountable care framework.

|

Notes: See Supplementary Table S1 for an explanation of each of the accountable care domains and ratings.

1. Population: 0 = no identified population, 5 = Population carefully planned and accounted for.

2. Outcomes: 0 = no target outcomes, 5 = Outcomes that matter to people; prioritised according to individual goals.

3. Metrics and learning: 0 = No metrics or learning 5 = Aggregated longitudinal data made public in format consistent across providers.

4. Payment and incentives: 0 = Payments for activities only 5 = Full capitation with minimum required quality standards.

5. Coordinated delivery: 0 = Uncoordinated provision of care, 5 = Clinical and data integration across full provider network; patients co-design care.

Collaborative commissioning

Despite the increased maturity of integrated care in NSW, prevailing policies have generally operated within existing funding structures and relied on informal rather than structural connections with the primary care sector. Collaborative Commissioning, the latest major integrated care reform policy in NSW, seeks to demonstrate proof-of-concept in changing the way health services are commissioned and funded. In this new way of working, Australian government funded PHNs and NSW state government funded Local Health Districts (LHDs) are forming regional alliances termed ‘patient centred co-commissioning groups’ (PCCGs). They assess existing service provisions and gaps for priority population cohorts, and collaborate across silos to jointly co-commission services as part of a comprehensive care pathway to address those gaps.24

NSW Health is supporting the policy through several enablers including supporting appropriate governance structures, provision of analytic and data support to assist in targeting and design of the care pathways, and initial stimulus funding for PCCGs to commission new services with the expectation that this funding will reduce over time. A linked data asset, comprising statewide hospital data and GP electronic medical records connects data silos to identify the target cohorts.25 GP and NSW administrative data are linked two times per year and reported back to program implementers on a 6-monthly basis as part of a monitoring and evaluation plan. PCCGs have also established a community of practice in which implementation learnings are shared. In addition, local program data from PCCGs are compiled and fed back to care providers on a more regular basis based on local requirements and integrated with new and existing quality improvement programs. At the time of writing, linked data were available for over 4 million people, almost 50% of the NSW population. Importantly, NSW Health and PCCGs have also agreed on a process to modify a-priori activity-based funding agreements to ensure that LHDs would not be penalised if they did not meet activity targets due to lower hospital use by the target cohort.

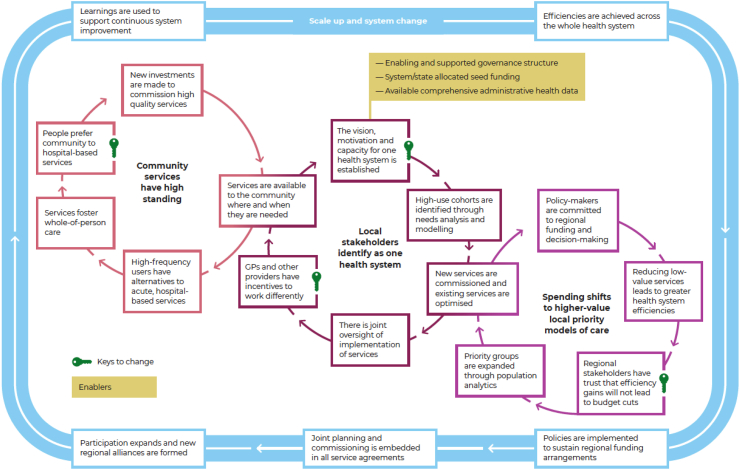

Fig. 1 outlines the theory of change for Collaborative Commissioning. The changes depend on four ‘virtuous cycles’ that potentiate the value of the policy (Fig. 1).

-

•

First cycle: local stakeholders identify as one health system (centre circle). They are sufficiently motivated to collaborate and provide joint oversight for the priority cohorts. Frontline care providers perceive the incentives (financial and non-financial) are sufficient to engage with the care pathway. This leads to addressing service gaps and reinforces the notion of a cohesive health system.

-

•

Second cycle: spending shifts towards higher-value, locally driven models of care (right circle). As PCCGs attenuate the rising rate of inappropriate hospital use, resources that would have been spent on hospital growth are directed toward additional services needed locally. Regional stakeholders require trust that efficiencies generated do not result in budget cuts and can be re-directed toward expanding the priority populations, leading to further investment in new or enhanced existing services and improved efficiency.

-

•

Third cycle: new investments in the care pathway (left circle) lead to an increased perception of the standing of community-based services in preference to hospitals and therefore an increased use. High frequency service users will consider the alternatives to hospital services are accessible and acceptable, addressing multiple needs to support whole person care rather than reactive care restricted to acute needs.

-

•

Fourth cycle (outside circle): focusses on the factors needed to support scale-up and whole system change. As efficiencies are achieved for target cohorts, policies become usual practice with joint planning and commissioning embedded into service agreements. This can lead to expansion of PCCGs, target cohorts and new pathways. As evaluation activity grows, the findings are continuously fed back to system planners to support a learning health system which is continuously adapting and improving. Of particular importance, sustainable change requires reform at all levels of the health system, particularly national health funding reform agreements.26

Fig. 1.

Collaborative commissioning theory of change.

In each virtuous cycle there are critical dependencies that are shown as keys for change in Fig. 1. These keys can be considered as rate limiting steps in stimulating engagement in each of the virtuous cycles and overcoming status quo inertia.

Case study – Northern Sydney PCCG

At the time of writing, six PCCGs have been established in NSW. Here, we discuss Northern Sydney PCCG, one of the earliest groups to be established. Northern Sydney encompasses an area of 900 km2 and provides services to around 939,000 people. Although it is one of the most socio-economically affluent regions in the country there are pockets of high disadvantage.27 The proportion of people aged over 75 years is projected to increase by 80% by 2041, compared to 19% for other age groups.28

The Northern Sydney PCCG is an alliance between the North Sydney Local Health District (NSLHD) and the Sydney North Health Network (SNHN) which manages the PHN for the region. The target patient cohort are people aged 75 years and older living in the community or in Residential Aged Care Facilities (RACFs). This cohort was prioritised following a detailed needs assessment, and informed by current national, state, and local policy priorities and consultations with clinicians and the community including patient journey modelling workshops. Older people are increasingly utilising the emergency department (ED) for care that could be safely treated in the community. From 2014 to 2019 ED presentations increased by 12.5% for the 75+ age group, far exceeding the population growth rate of 4.4%.29 A clinical audit found that of 1800 patients aged 75 years and older presenting to EDs, approximately 30% were determined by clinical teams to be suitable for management through existing community services. Further, the stakeholder consultation identified that hospitalisation poses many risks for older people, negatively impacts patient experience, and incurs greater costs than community-based services. Once the priority cohort was confirmed, further stakeholder consultations were conducted to inform the development of the pathway (Panel 2).

Panel 2. Stakeholder consultation for the rapid care pathway.

Stakeholder consultation included 74 primary care staff at 31 practices, 11 LHD services, NSW Ambulance, and 10 aged care and commissioned support services. Consumer focus groups, individual interviews, and a large group workshop were also conducted. A survey of 253 people aged 75 years and older and 92 carers was conducted with the support of 34 community organisations. Key findings include:

-

•

Frail and older people vary considerably in terms of mobility, social support, cognition, income, ability to use technology, and cultural background, underscoring the need for a flexible and adaptable model of care to meet the unique needs of consumers.

-

•

Navigation and access to health and aged care services were considered too complex and time consuming. Health services are a challenge to access, have cumbersome referral processes and long waiting times. A lack of care coordination to support consumers compounds these issues.

-

•

Private healthcare services partially address gaps in public services; however, they are not affordable to everyone.

-

•

Half of consumer survey respondents prefer to see their general practitioner (GP) in a time of crisis rather than go to ED, around one third felt they would likely use ED because their GP would not be available at short notice.

-

•

Some GPs considered referral to ED the most expedient way to access the required hospital/non-GP specialist services for their patients, particularly when they have complex and chronic health issues.

-

•

Service providers have widely varied practices both within and across professions, particularly in the areas of referral, use of technology and awareness of services in their area.

-

•

Several stakeholders also described systemic barriers that need to be addressed to reduce fragmentation and complexity. This would require a whole-of-government and nationally coordinated long-term plan.

Care pathway overview

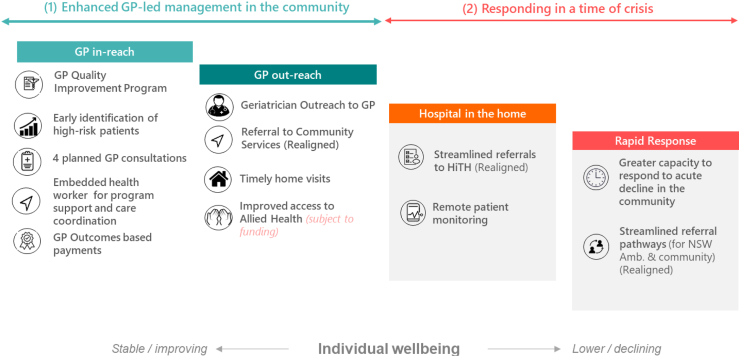

Northern Sydney's Rapid Care pathway is a regionally led initiative to provide integrated, timely, and proactive care in the community with the aim of reducing avoidable ED presentations for older people. It builds on previous smaller scale initiatives, including novel palliative care and dementia care models.30,31 The pathway involves close collaboration between primary care and hospital sectors to foster improved transition and communication across settings in response to individual needs (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Overview of the rapid care pathway services.

Building on recommendations from the stakeholder consultation, previous similar care delivery models and rapid evidence reviews of specific pathway components, four sub-components to the pathway were developed which are either new or realigned, existing services. These components are closely aligned with other NSW Health policy initiatives in urgent care and integrated care.

GP in-reach

GPs and their general practice teams are participating in a new quality improvement program focussed on the target cohort. They are using two tools to assess risk of hospitalisation and emergency department presentation—one based on NSLHD acute care data and another based on the Johns Hopkins ACG System that is integrated with primary care practice software systems.32 GPs are also encouraged to use clinical judgement in determining people suitable for the program. Patients at high risk are invited to a baseline assessment including a medical review and a quality of life and frailty screening assessment. They are then enrolled in the pathway and receive at least four proactively planned encounters with their general practice team. Practices have access to a performance dashboard to monitor care for their enrolled patients. They also have access to a health pathways portal to assist with awareness of local services to support care for frail elderly people.

To support the quality improvement program, a new care coordination service is planned to provide practices with staff to support identification of the target cohort, conduct care coordination and navigation activities, undertake home visits, and promote better utilisation of existing services. Practices can use a registered nurse employed by the NSLHD or use existing nursing staff within their practice team. General practices will receive a sign on payment of USD $670 to cover set-up costs, a payment of USD $400 per patient enrolled into the pathway to support more proactive and timely access to care; and an outcomes-based payment of USD $165 per patient for achievement of quality measures. GPs will continue to be remunerated for services currently reimbursed through the Australian government's fee-for-service Medicare scheme.

GP-outreach

The second component encourages GPs to refer to and utilise a geriatrician to GP service. Through this service, geriatricians work collaboratively with GPs to manage patients with complex needs and/or multiple chronic conditions and identify those who may be at potential risk of deterioration. Referral to existing navigation and care coordination services and other relevant community services is also being actively promoted. Timely home visits will be available through the newly commissioned care coordination service described above. Improved access to federally funded allied health services is also being considered to enhance access to specialised exercise programs, falls prevention programs, home modifications and equipment, mental health services and nutrition guidance.

Hospital in the home

Hospital in the Home (HiTH) is an existing NSLHD service where GP referral processes are being enhanced for easier access. Senior HiTH clinicians triage referrals and a management plan is confirmed with the primary care provider. Remote patient monitoring is being embedded in outpatient heart failure services. Enrolled patients use Bluetooth™ enabled devices to measure vital signs and complete frequent survey assessments to better identify a deterioration in health status and the need for early intervention. Over time, remote monitoring services will be expanded to other patient groups.

Rapid response service

NSLHD currently has three Geriatric Rapid Response teams providing acute assessment and treatment plans predominantly for people in RACFs. The focus of these teams is being expanded beyond RACFs to include people living independently in the community. Referring providers including Ambulance NSW, community services, and GPs, are being encouraged to use the Geriatric Rapid Response team for conditions that could potentially be managed outside of the ED, particularly people experiencing an acute or functional decline which could result in an ED presentation if not seen within 48 hours. Referrals from NSW Ambulance have been streamlined through the development and implementation of referral pathways for both ‘000’ and extended care paramedics as well as the NSW Ambulance Virtual Care Contact Centre.

Evaluation of the care pathway outcomes

We will focus on care utilisation, quality, and patient and provider experience to evaluate the impact of the pathway. A detailed statistical analysis plan is currently being developed which will articulate pre-specified analyses to be undertaken prior to commencing the summative evaluation. This will include making comparisons between the target cohort and propensity score matched populations in the other six Sydney metropolitan LHD/PHN regions and sub-group analyses. Within the Northern Sydney region, we will also make comparisons between those enrolled into the care pathway and those not participating in the program to understand the representativeness of the enrolled population and of the general practices that actively engage in the pathway. Specific outcomes are outlined in Panel 3. In addition, we will conduct a formative evaluation to assess enablers and constraints to delivery, impact, sustainability, and generalisability of the care pathway drawing on program data, provider and patient experience surveys and in-depth interviews with a variety of stakeholders.

Panel 3. Impact evaluation outcomes for the rapid care pathway.

The primary outcome of the pathway will be the rate of emergency department presentations per 100 people in the target age range at 12, 24 and 36 months of program implementation.

Secondary outcomes will apply to the same target population and include:

-

•

All cause hospitalisations per 100 persons.

-

•

Avoidable (or “potentially preventable”) hospital admissions per 100 persons

-

•

Unplanned hospital admissions, defined as emergency hospital admissions per 100 persons

-

•

Average length of stay

-

•

Emergency department presentations per 100 persons by triage category

-

•

Quality of care measures—including a mix of preventive health measures, disease management measures, and service measures, subject to data availability constraints.

-

•

Patient reported outcomes—using the PROMIS-29 and EQ-5D-5L survey questions33,34

-

•

Health care provider experience related to the change event

Outcomes will be disaggregated by age, gender, socioeconomic status, comorbid chronic conditions and other measures of equity subject to data availability.

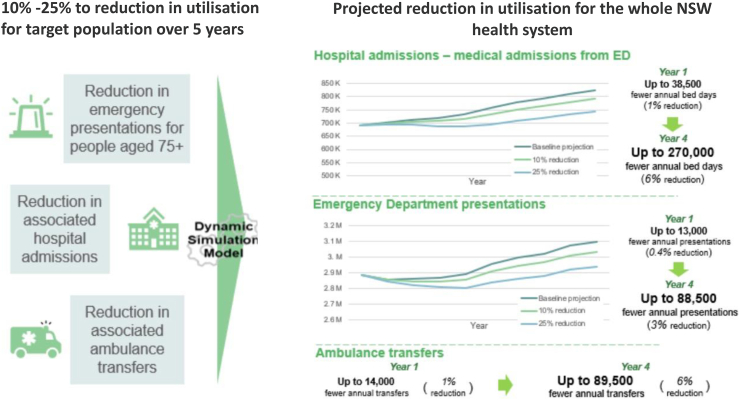

Sustainability and scale up considerations—a modelling study of Northern Sydney's care pathway

Given the longer-term goal is to implement regionally designed care pathways statewide, we conducted a modelling study to analyse the sustainability and assess the potential benefits and costs of large-scale implementation of the Rapid Care pathway across all ten PHN regions in NSW. We built a dynamic simulation model to determine the projected activity benefit for the NSW health system, assuming a 10% or 25% reduction in emergency department utilisation, hospital admissions, and ambulance transfers for the target population.

The benefits for avoided ED and hospital activity are based on current activity figures for each PHN region. ED demand avoidance rates are assumed to be the same in metropolitan, regional and rural regions. It also assumes that the Rapid Care pathway will take five years to implement in all regions, with the reductions increasing in a linear manner with the same adoption rates across all geographic regions. Under these assumptions Fig. 3 outlines the potential avoided activity for the whole NSW health system with a projected 6%, 3% and 6% reduction at 4 years in ED, admissions, and ambulance transfers respectively. Although such outcomes may vary greatly under alternative assumptions, such modelling work is an important decision-making tool for understanding the potential efficiency gains in the system. Of critical importance will be re-appraisal of these assumptions as real-world implementation data become available and actual rates of adoption, hidden or unexpected costs, and influence of external factors such as changes in federal level policies come to light.

Fig. 3.

Potential activity benefits from a statewide scale-up of the rapid care pathway—findings from a dynamic simulation model.

Discussion

In this paper, we describe a new NSW government health care reform policy, Collaborative Commissioning, which is investing in regional health alliances (PCCGs) to overcome health system silos, particularly between the hospital and primary care sectors. Based on consultation with the architects of this policy, Collaborative Commissioning is theorised to achieve greater integration through a combination of interventions related to governance (where local stakeholders identify as being part of one health system), service delivery (where communities perceive new and transformed services as preferable to status quo) and incentives (where efficiency gains are reinvested according to local priorities with progressive shifts to higher value care). The case study of Northern Sydney's PCCG pathway for older person's care highlights how these changes are being implemented and the associated modelling study projects the potential improvements from reduced hospital activity if scaled across the state.

Both the overall theory of change and the case study of older person's care align with Valentijn's conceptual framework of integrated care, particularly in relation to meso-level professional and organisational integration.7 It also aligns closely with many health system reform policies internationally which are delivered through meso-tier organisations.9,35 A key enabler to successful implementation of such models is leadership commitment and development of trusting relationship and open communication across all partner organisations.36 Jackson and colleagues argue the importance of a “value co-creation process” where “stakeholders and end users share, combine and leverage each other's resources and abilities from design to implementation” to bring about health care reforms.37 Australia has historically been cautious in implementing reforms to address health system fragmentation. The most recent large-scale initiative was the 2017–2021 Health Care Homes (HCH) Trial.38 This included risk stratification tools to identify patients at high risk of hospitalisation; funding reforms with bundled payments available for a patient population that voluntarily enrolled with a general practice to encourage a shift away from fee for service payments; training resources and support from PHNs; and use of electronic shared care planning tools. Of the 227 general practices initially participating in the trial, only 106 (47%) remained in the trial at the end. Compared with matched controls, patients enrolled in the trial had more encounters with GPs and allied health services, and improvements in process measures of chronic disease management, but no measurable changes in clinical risk factors for chronic disease or use of hospital services. There was little change in measures of care coordination or patient experience. The limited impact likely reflected low fidelity to the original components of the HCH model, driven by low levels of patient enrolment and provider engagement. This meant that general practices did not achieve a critical mass of patient enrolments to drive substantive changes in the way they delivered care.

While HCH was focussed on one part of the system (via general practices), Collaborative Commissioning is taking a different strategic approach by enabling collaboration and integration of meso-level organisations across care settings with the expectation that these organisations can galvanise the support of frontline service providers working in different parts of the health system. This is a pragmatic approach to achieving greater health system integration in Australia and offers the opportunity to test new service delivery models that foster greater federal-state integration, without the need for wholesale reform of the federated system. The theory of change, presented in this paper highlights the need for multi-faceted reform in governance, service delivery and incentives to support patient, provider and organisational engagement. Robust evaluation is critical to assess the extent to which it can effectively engage providers and patients to adopt new ways of providing and receiving care.

Investment in care coordination activities appears to be a particularly important enabler to achieving integration and is demonstrated as a key feature of the Northern Sydney older persons care model case study. Hersey and colleagues studied expense reports from ACOs participating in the Medicare Shared Savings Program and found that 53% of related ACO expenses were toward care coordination and management.39 A review of 16 systematic reviews on care coordination found considerable variation in the type and intensity of care coordination, and mixed outcomes in reducing hospitalisations and ED visits or improving patient experience.40 Overall, observational and qualitative studies tend to report more favourable outcomes than randomised controlled trials. Key determinants of positive outcomes include careful patient selection criteria based on specific risk factors and/or needs, high-intensity support services and use of multidisciplinary plans, and patient-provider communication tools including patient coaching. Collaborative Commissioning will be implementing a variety of care coordination activities in diverse settings, populations and care pathways and this provides an important opportunity to better understand both the impact and optimal implementation model for such activities.

Another important enabler is the initial investments made by the government to support joint planning and initial start–up activities. This is intended to foster the institutional conditions necessary for joint regional planning. Factors such as building integrated health information systems, embedding quality improvement processes within health services, and robust financial and performance monitoring systems are likely to be key drivers of success.41,42 Further, trust from government that PCCGs will make judicious use of stimulus funds to support system transformation is needed. This trust fosters PCCG confidence that funding will not be withdrawn in the absence of short-term improvements and provides PCCGs with discretion on which areas to prioritise in the reform journey. In turn, PCCGs need to manage dual accountabilities both to payers and the communities and service providers they support. The modelling study conducted suggests that reductions in hospital activity take some time to accrue, but over several years the potential benefits can become large. This ability to take a ‘long-haul’ approach again emphasises the importance of invested collaboration and committed leadership.

Conclusion

Most health systems worldwide are grappling with cost containment while at the same time driving a quality and safety agenda and attempting to enhance the patient and provider experience of care. In varying forms, many systems are investing in meso-tier organisations and support structures to foster higher performance. However, the evidence base for understanding factors driving successful implementation remains mixed and difficult to interpret. In the Australian context, working collaboratively across acute and primary care sectors at the meso-tier level offers the potential to achieve greater integration and improve performance, without the need for major reforms to the country's federated system of government. NSW Health has been embarking on several integrated care reforms over the last decade. Collaborative Commissioning is the first policy initiative investing in meso-tier organisations (PHNs and LHDs) across care silos to form alliances to support improved patient care for locally determined priority populations. Built with scale in mind, they have potential to make a substantial impact on health system performance both in NSW and other jurisdictions and will be followed carefully to document their implementation and outcomes over the coming years.

Contributors

DP and AMF conceptualised the article and BL provided critical input in the early stages of writing. DP wrote the first draft of the manuscript with input from CHS, GS, PP, AdS, JM, TB, BF on the theory of change; JB, HH, JI, CS, LH and DW on the case study; and AS on the dynamic simulation study. DP and DC are Co-Chairs of the Collaborative Commissioning Steering Committee. DW is the senior author for the paper and provided final approval from NSW Health. AC, AE, SAP, SJ, LB, LD, LJ, SL, BHK provided critical input to the manuscript on multiple drafts. All authors reviewed and approved the final submitted version.

Declaration of interests

This work is funded by a NHMRC partnership grant (ID 1198416). This grant includes funding from the NSW Ministry of Health. The NSW Ministry of Health are co-authors on the publication.

Footnotes

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lanwpc.2024.101013.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

References

- 1.Fenwick T., Seville E., Brunsdon D. 2009. Reducing the impact of organisational silos on resilience: a report on the impact of silos on resilience and how the impacts might be reduced.https://ir.canterbury.ac.nz/handle/10092/9468 Accessed 9 Nov 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 2.de Waal A., Weaver M., Day T., van der Heijden B. Silo-busting: overcoming the greatest threat to organizational performance. Sustainability. 2019;11(23):6860. [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization . World Health Organization; Geneva: 2000. The world health report: 2000: health systems: improving performance. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rivette G. 2021. The history of the NHS.https://www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/health-and-social-care-explained/the-history-of-the-nhs Accessed 9 Nov 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services . 2021. CMS’ program history.https://www.cms.gov/About-CMS/Agency-Information/History Accessed 9 Nov 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boxall A.M., Gillespie J. UNSW Press; Sydney: 2013. Making Medicare: the politics of universal health care in Australia. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Valentijn P.P., Schepman M.S., Opheij W., Bruijnzeels M.A. Understanding integrated care: a comprehensive conceptual framework based on the integrative functions of primary care. Int J Integrated Care. 2013;13:e010–e. doi: 10.5334/ijic.886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Richter M., Dragano N. Micro, macro, but what about meso? The institutional context of health inequalities. Int J Public Health. 2018;63(2):163–164. doi: 10.1007/s00038-017-1064-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peiris D., News M., Nallaiah K. 2018. Evidence check: accountable care organisations.https://www.saxinstitute.org.au/wp-content/uploads/Accountable-care-organisations.pdf Accessed 9 Nov 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Struijs J., deVried E.F., Baan C.A., Van Gils P.F., Rosenthal M.B. 2020. Bundled-payment models around the world: how they work and what their impact has been. Accessed 9 Nov 2023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barnett M.L., Wilcock A., McWilliams J.M., et al. Two-year evaluation of mandatory bundled payments for joint replacement. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(3):252–262. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1809010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Navathe A.S., Emanuel E.J., Venkataramani S.A., et al. Spending and quality after three years of medicare's voluntary bundled payment for joint replacement surgery. Health Aff (Millwood) 2020;39(1):58–66. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2019.00466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McWilliams J.M., Hatfield L.A., Landon B.E., Hamed P., Chernew M.E. Medicare spending after 3 years of the medicare shared savings program. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(12):1139–1149. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1803388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McWilliams J.M., Hatfield L.A., Landon B.E., Chernew M.E. Savings or selection? Initial spending reductions in the medicare shared savings program and considerations for reform. Milbank Q. 2020;98(3):847–907. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.12468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McClellan M., Kent J., Beales S.J., et al. Accountable care around the world: a framework to guide reform strategies. Health Aff (Millwood) 2014;33(9):1507–1515. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stange K.C., Nutting P.A., Miller W.L., et al. Defining and measuring the patient-centered medical home. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(6):601–612. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1291-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.John J.R., Jani H., Peters K., Agho K., Tannous K.W. The effectiveness of patient-centred medical home-based models of care versus standard primary care in chronic disease management: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised and non-randomised controlled trials. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(18):6886. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17186886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sinaiko A.D., Landrum M.B., Meyers D.J., et al. Synthesis of research on patient-centered medical homes brings systematic differences into relief. Health Aff (Millwood) 2017;36(3):500–508. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.1235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schneider E.C., Shah A., Doty M.M., Tikkanen R., Fields K., Williams R.D. 2021. MIRROR, MIRROR 2021 reflecting poorly: health care in the U.S. Compared to other high-income countries.https://www.commonwealthfund.org/sites/default/files/2021-08/Schneider_Mirror_Mirror_2021.pdf Accessed 9 Nov 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Glover L., Woods M. 2020. International health care system profiles- Australia.https://www.commonwealthfund.org/international-health-policy-center/countries/australia Accessed 9 Nov 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Australian Institute for Health and Welfare . 2020. Health expenditure Australia 2018–19. Health and welfare expenditure series no.66.https://www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/a5cfb53c-a22f-407b-8c6f-3820544cb900/aihw-hwe-80.pdf.aspx?inline=true Cat. no. HWE 80. Accessed 9 Nov 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Esterman A.J., Ben-Tovim D.I. The Australian coordinated care trials: success or failure? The second round of trials may provide more answers. Med J Aust. 2002;177(9):469–470. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2002.tb04911.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gardner K., Yen L., Banfield M., Gillespie J., Mcrae I., Wells R. From coordinated care trials to medicare locals: what difference does changing the policy driver from efficiency to quality make for coordinating care? Int J Qual Health Care. 2012;25(1):50–57. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzs069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koff E., Pearce S., Peiris D.P. Collaborative commissioning: regional funding models to support value-based care in New South Wales. Med J Aust. 2021;215(7):297–301.e1. doi: 10.5694/mja2.51243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Correll P., Feyer A., Phan P.T., et al. Lumos: a statewide linkage programme in Australia integrating general practice data to guide system redesign. Int J Integrated Care. 2021;3(1) doi: 10.1136/ihj-2021-000074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care 2020–25 National Health Reform Agreement (NHRA) 2020. https://www.health.gov.au/our-work/2020-25-national-health-reform-agreement-nhra Accessed 9 Nov 2023.

- 27.Sydney North Health Network Sydney north health network health profile. 2021. https://sydneynorthhealthnetwork.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/SNHN-LGA-fact-sheet-SNHN.pdf Accessed 9 Nov 2023.

- 28.NSW Government - Department of Planning Industry and Environment 2019 population projections. 2021. https://www.planning.nsw.gov.au/Research-and-Demography/Population-projections Accessed 9 Nov 2023.

- 29.Northern Sydney Local Hospital District . North Sydney Local Hospital District; Sydney: 2020. NSLHD emergency department activity data collection 2018-2019. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Robinson S., Varhol R., Bell C., Quirk F., Durrington L. HealthPathways: creating a pathway for health systems reform. Aust Health Rev. 2015;39(1):9–11. doi: 10.1071/AH14155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Canterbury District Health Board . 2022. Health pathways community.https://www.healthpathwayscommunity.org/ Accessed 9 Nov 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 32.University J.H., Hospital T.J.H., System J.H.H. Johns hopkins ACG® system. 2023. https://www.hopkinsacg.org/ accessed 9 Nov 2023.

- 33.Hays R.D., Spritzer K.L., Schalet B.D., Cella D. PROMIS(®)-29 v2.0 profile physical and mental health summary scores. Qual Life Res. 2018;27(7):1885–1891. doi: 10.1007/s11136-018-1842-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.EuroQol Group . 2021. EQ-5D-5L.https://euroqol.org/eq-5d-instruments/eq-5d-5l-about/ Accessed 9 Nov 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gauld R. What should governance for integrated care look like? New Zealand's alliances provide some pointers. Med J Aust. 2014;201(3):S67–S68. doi: 10.5694/mja14.00658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gurung G., Jaye C., Gauld R., Stokes T. Lessons learnt from the implementation of new models of care delivery through alliance governance in the Southern health region of New Zealand: a qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2022;12(10) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2022-065635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jackson C.L., Hambleton S.J. Value co-creation driving Australian primary care reform. Med J Aust. 2016;204(7):S45–S46. doi: 10.5694/mja16.00128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care Health Care Homes trial – evaluation reports collection. 2022. https://www.health.gov.au/resources/collections/health-care-homes-trial-evaluation-reports-collection Accessed 9 Nov 2023.

- 39.Hersey C., McWilliams J., Fout B., Trombley M.J., Scarpati L. An analysis of medicare accountable care organization expense reports. Am J Manag Care. 2021;27(12):569–572. doi: 10.37765/ajmc.2021.88795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Duan-Porter W., Ullman K., Majeski B., Miake-Lye I., Diem S., Wilt T.J. Care coordination models and tools: a systematic review and key informant interviews. 2020. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK566158/ Accessed 9 Nov 2023. [PubMed]

- 41.Peiris D. Can ‘meso-tier’ healthcare organizations enhance health system performance? - lessons from US Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs) and a discussion of the implications for Australia. Int J Integrated Care. 2017;17(5):A13. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Peiris D., Phipps-Taylor M.C., Stachowski C.A., et al. ACOs holding commercial contracts are larger and more efficient than noncommercial ACOs. Health Aff (Millwood) 2016;35(10):1849–1856. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.0387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.