Abstract

Background

Pharmacological therapy for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is aimed at relieving symptoms, improving quality of life and preventing or treating exacerbations.

Treatment tends to begin with one inhaler, and additional therapies are introduced as necessary. For persistent or worsening symptoms, long‐acting inhaled therapies taken once or twice daily are preferred over short‐acting inhalers. Several Cochrane reviews have looked at the risks and benefits of specific long‐acting inhaled therapies compared with placebo or other treatments. However for patients and clinicians, it is important to understand the merits of these treatments relative to each other, and whether a particular class of inhaled therapies is more beneficial than the others.

Objectives

To assess the efficacy of treatment options for patients whose chronic obstructive pulmonary disease cannot be controlled by short‐acting therapies alone. The review will not look at combination therapies usually considered later in the course of the disease.

As part of this network meta‐analysis, we will address the following issues.

1. How does long‐term efficacy compare between different pharmacological treatments for COPD? 2. Are there limitations in the current evidence base that may compromise the conclusions drawn by this network meta‐analysis? If so, what are the implications for future research?

Search methods

We identified randomised controlled trials (RCTs) in existing Cochrane reviews by searching the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR). In addition, we ran a comprehensive citation search on the Cochrane Airways Group Register of trials (CAGR) and checked manufacturer websites and reference lists of other reviews. The most recent searches were conducted in September 2013.

Selection criteria

We included parallel‐group RCTs of at least 6 months' duration recruiting people with COPD. Studies were included if they compared any of the following treatments versus any other: long‐acting beta2‐agonists (LABAs; formoterol, indacaterol, salmeterol); long‐acting muscarinic antagonists (LAMAs; aclidinium, glycopyrronium, tiotropium); inhaled corticosteroids (ICSs; budesonide, fluticasone, mometasone); combination long‐acting beta2‐agonist (LABA) and inhaled corticosteroid (LABA/ICS) (formoterol/budesonide, formoterol/mometasone, salmeterol/fluticasone); and placebo.

Data collection and analysis

We conducted a network meta‐analysis using Markov chain Monte Carlo methods for two efficacy outcomes: St George's Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ) total score and trough forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1). We modelled the relative effectiveness of any two treatments as a function of each treatment relative to the reference treatment (placebo). We assumed that treatment effects were similar within treatment classes (LAMA, LABA, ICS, LABA/ICS). We present estimates of class effects, variability between treatments within each class and individual treatment effects compared with every other.

To justify the analyses, we assessed the trials for clinical and methodological transitivity across comparisons. We tested the robustness of our analyses by performing sensitivity analyses for lack of blinding and by considering six‐ and 12‐month data separately.

Main results

We identified 71 RCTs randomly assigning 73,062 people with COPD to 184 treatment arms of interest. Trials were similar with regards to methodology, inclusion and exclusion criteria and key baseline characteristics. Participants were more often male, aged in their mid sixties, with FEV1 predicted normal between 40% and 50% and with substantial smoking histories (40+ pack‐years). The risk of bias was generally low, although missing information made it hard to judge risk of selection bias and selective outcome reporting. Fixed effects were used for SGRQ analyses, and random effects for Trough FEV1 analyses, based on model fit statistics and deviance information criteria (DIC).

SGRQ SGRQ data were available in 42 studies (n = 54,613). At six months, 39 pairwise comparisons were made between 18 treatments in 25 studies (n = 27,024). Combination LABA/ICS was the highest ranked intervention, with a mean improvement over placebo of ‐3.89 units at six months (95% credible interval (CrI) ‐4.70 to ‐2.97) and ‐3.60 at 12 months (95% CrI ‐4.63 to ‐2.34). LAMAs and LABAs were ranked second and third at six months, with mean differences of ‐2.63 (95% CrI ‐3.53 to ‐1.97) and ‐2.29 (95% CrI ‐3.18 to ‐1.53), respectively. Inhaled corticosteroids were ranked fourth (MD ‐2.00, 95% CrI ‐3.06 to ‐0.87). Class differences between LABA, LAMA and ICS were less prominent at 12 months. Indacaterol and aclidinium were ranked somewhat higher than other members of their classes, and formoterol 12 mcg, budesonide 400 mcg and formoterol/mometasone combination were ranked lower within their classes. There was considerable overlap in credible intervals and rankings for both classes and individual treatments.

Trough FEV1 Trough FEV1 data were available in 46 studies (n = 47,409). At six months, 41 pairwise comparisons were made between 20 treatments in 31 studies (n = 29,271). As for SGRQ, combination LABA/ICS was the highest ranked class, with a mean improvement over placebo of 133.3 mL at six months (95% CrI 100.6 to 164.0) and slightly less at 12 months (mean difference (MD) 100, 95% CrI 55.5 to 140.1). LAMAs (MD 103.5, 95% CrI 81.8 to 124.9) and LABAs (MD 99.4, 95% CrI 72.0 to 127.8) showed roughly equivalent results at six months, and ICSs were the fourth ranked class (MD 65.4, 95% CrI 33.1 to 96.9). As with SGRQ, initial differences between classes were not so prominent at 12 months. Indacaterol and salmeterol/fluticasone were ranked slightly better than others in their class, and formoterol 12, aclidinium, budesonide and formoterol/budesonide combination were ranked lower within their classes. All credible intervals for individual rankings were wide.

Authors' conclusions

This network meta‐analysis compares four different classes of long‐acting inhalers for people with COPD who need more than short‐acting bronchodilators. Quality of life and lung function were improved most on combination inhalers (LABA and ICS) and least on ICS alone at 6 and at 12 months. Overall LAMA and LABA inhalers had similar effects, particularly at 12 months. The network has demonstrated the benefit of ICS when added to LABA for these outcomes in participants who largely had an FEV1 that was less than 50% predicted, but the additional expense of combination inhalers and any potential for increased adverse events (which has been established by other reviews) require consideration. Our findings are in keeping with current National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines.

Keywords: Female; Humans; Male; Middle Aged; Adrenal Cortex Hormones; Adrenal Cortex Hormones/therapeutic use; Adrenergic beta‐2 Receptor Agonists; Adrenergic beta‐2 Receptor Agonists/therapeutic use; Cholinergic Antagonists; Cholinergic Antagonists/therapeutic use; DNA‐Binding Proteins; Delayed‐Action Preparations; Delayed‐Action Preparations/administration & dosage; Muscarinic Antagonists; Muscarinic Antagonists/therapeutic use; Nuclear Proteins; Pulmonary Disease, Chronic Obstructive; Pulmonary Disease, Chronic Obstructive/drug therapy; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Transcription Factors

Plain language summary

Which long‐acting inhaled drugs, used alone or in combination, are the most effective for people with COPD?

Why is this question important?

Inhaled drugs for COPD have been shown to relieve symptoms, improve quality of life and prevent or treat flare‐ups. Treatment with these inhaled drugs tends to begin with one inhaler, and additional therapies are introduced as necessary. For persistent or worsening symptoms, long‐acting inhaled drugs taken once or twice daily are preferred over short‐acting ones. Several Cochrane reviews have looked at the risks and benefits of specific long‐acting inhaled therapies compared with placebo or other treatments. However for patients and clinicians, it is important to understand the benefits of these treatments relative to each other, and whether a particular type of inhaled therapy is more beneficial than the others.

How did we answer the question? We looked for studies in existing Cochrane reviews and performed detailed electronic searches up to September 2013. Studies were included if they lasted at least six months and compared any of the following treatments versus any other for people with COPD: long‐acting beta2‐agonists (LABAs—formoterol, indacaterol, salmeterol); long‐acting muscarinic antagonists (LAMAs—aclidinium, glycopyrronium, tiotropium); inhaled corticosteroids (ICSs—budesonide, fluticasone, mometasone); combination long‐acting beta2‐agonist and inhaled corticosteroid (LABA/ICS—formoterol/budesonide, formoterol/mometasone, salmeterol/fluticasone); and placebo.

We conducted a network meta‐analysis to assess the benefits of each type of treatment (e.g. long‐acting beta2‐agonists) relative to the others for quality of life and lung function. We also looked at how much individual treatments varied (e.g. How different were the three inhaled steroids from one other?) and whether particular treatments were more effective than others. We assessed the data for six months and 12 months separately and reported six months as the primary findings.

What did we find? We found 71 relevant studies, but not all measured the outcomes we were interested in. Forty‐two studies were included in the quality of life analyses (measured on St George's Respiratory Questionnaire), and 46 were included in the lung function analyses.

Evidence from good quality and similar trials supported LABA/ICS combinations as the most likely treatment strategy to bring the greatest improvement to quality of life and lung function. Combination therapy gave an average benefit of 3.9 units over placebo at six months. LAMAs and LABAs were ranked second and third at six months (‐2.63 and ‐2.29 units, respectively), especially when unreliable trials were not included, but a large degree of overlap in the estimates was noted.

Combination LABA/ICS was the highest ranked class for trough forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1), with mean improvement over placebo of 133 mL at six months (95% credible Interval (CrI) 101 to 164). As was the case for SGRQ, LAMAs (mean difference (MD) 104, 95% CrI 82 to 125) were ranked just ahead of LABAs (MD 99, 95% CrI 72 to 128) at six months, and ICSs were the lowest ranked class (MD 65, 95% CrI 33 to 97).

For both outcomes, the effects of LABA and ICS used alone appeared to increase when used together for six months, but initial differences between the treatment classes were less obvious after a year of treatment.

Conclusion Quality of life and lung function were improved most on combination inhalers (LABA and ICS) and least on ICS alone at 6 and 12 months. Overall LAMA and LABA inhalers had similar effects, particularly at 12 months. The network has demonstrated the benefit of ICS when added to LABA for these outcomes in participants who largely had an FEV1 that was less than 50% predicted, but the additional expense of combination inhalers and any potential for increased adverse events (which has been shown by other reviews) require consideration. Our findings are in keeping with current National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines.

Background

Description of the condition

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a respiratory disease characterised by chronic and progressive breathlessness, cough, sputum production and airflow obstruction, all of which lead to restricted activity and poor quality of life (GOLD). The World Health Organization (WHO) has estimated that COPD is the fourth or fifth most common single cause of death worldwide, and the treatment and management costs present a significant burden to public health. In the UK, the annual cost of COPD to the National Health Service (NHS) is estimated to be £1.3 million per 100,000 people (NICE 2011). Furthermore, because of slow onset and under‐recognition of the disease, it is heavily under‐diagnosed (GOLD). COPD comprises a combination of bronchitis and emphysema and involves chronic inflammation and structural changes in the lung. Cigarette smoking is the most important risk factor; however, air pollution and occupational dust and chemicals can also increase the risk of developing the disease. COPD is a progressive disease that leads to decreased lung function over time, even with the best available care. Currently no cure for COPD is known, although it is both preventable and treatable. Management of the disease is multifaceted and includes interventions for smoking cessation (van der Meer 2001), pharmacological treatments (GOLD), education (Effing 2007) and pulmonary rehabilitation (Lacasse 2006; Puhan 2011). Pharmacological therapy is aimed at relieving symptoms, improving exercise tolerance and quality of life, slowing decline and even improving lung function and preventing and treating exacerbations. COPD exacerbations impair patients' quality of life (GOLD), and a large part of the economic burden of COPD is attributed to the cost of managing exacerbations, particularly those resulting in use of acute care services or hospitalisation (Hutchinson 2010). In the UK, one in eight emergency admissions to hospital is for COPD, and it is one of the most costly conditions treated by the NHS (NICE 2011). Appropriate pharmacological management of the disease is therefore important, particularly for reducing and preventing exacerbations.

Description of the interventions

Pharmacological management of COPD tends to begin with one treatment, and additional therapies are introduced as necessary to control symptoms and reduce the frequency and severity of exacerbations (GOLD). The first step is often a short‐acting bronchodilator for control of breathlessness when needed: either a short‐acting beta2‐agonist (SABA; e.g. salbutamol) or the short‐acting muscarinic antagonist (SAMA) ipratropium. Both bronchodilators have a duration of action of four to six hours (Beeh 2010), and they improve lung function and breathlessness (Appleton 2006; Sestini 2009). For persistent or worsening breathlessness associated with lung function decline, long‐acting bronchodilators may be introduced (GOLD). These comprise long‐acting beta2‐agonists, such as salmeterol or formoterol (LABAs; duration of action 12 hours) and indacaterol (duration of action 24 hours), and long‐acting anticholinergic agents, such as tiotropium (duration of action 24 hours) and more recently aclidinium bromide and glycopyrronium bromide. Regular treatment with long‐acting bronchodilators is preferred over treatment with regular short‐acting bronchodilators on the basis of efficacy and adverse effects (Beeh 2010; GOLD). An alternative when bronchodilators are not available or affordable is theophylline, an oral phosphodiesterase (PDE) inhibitor. However, theophylline is less effective and is less well tolerated than inhaled long‐acting bronchodilators. For patients with severe or very severe COPD (forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) < 50% predicted) with repeated exacerbations, GOLD recommends the addition of inhaled corticosteroids (ICSs) to bronchodilator treatment. ICSs are anti‐inflammatory drugs that are licensed as combination inhalers with LABAs. The most common combinations of ICS and LABA in combination inhalers are fluticasone and salmeterol, and budesonide and formoterol. The most severely ill group of patients with advanced COPD may also benefit from treatment with the PDE4 inhibitor roflumilast, which may reduce the risk of exacerbations (GOLD), alongside other beta2‐agonists or anticholinergic agents and ICS, but these combinations are not considered in this review.

How the interventions might work

Long‐acting beta2‐agonists

Inhaled long‐acting beta2‐agonists (LABAs) activate beta2‐receptors in the smooth muscle of the airway, leading to a cascade of reactions that result in bronchodilation. Commonly used LABAs include salmeterol, formoterol and indacaterol. The duration of action for salmeterol and formoterol is approximately 12 hours; therefore they are usually taken twice daily. Indacaterol has a duration of action of 24 hours and therefore can be taken once daily. As with long‐acting muscarinic antagonists (LAMAs), LABAs are commonly used to control symptoms and reduce exacerbations in stable COPD (Moen 2010; Rodrigo 2008). Possible side effects of LABAs include cardiac effects such as arrhythmia and palpitations, muscle tremors, headache and dry mouth (Berger 2008).

Inhaled corticosteroids

Inhaled corticosteroids (ICSs) are anti‐inflammatory drugs. ICSs are licensed as combination inhalers with LABA. The most common combinations of ICS and LABA in combination inhalers are fluticasone and salmeterol, and budesonide and formoterol. Combination inhalers have similar effects to LABA alone, reducing exacerbation rates and improving patients' quality of life. However, some have argued that the difference is small (Rodrigo 2009), and ICS therapy, alone or in combination with beta2‐agonists, is associated with increased risk of pneumonia and osteoporotic fracture (GOLD; Loke 2011; Singh 2010).

Long‐acting muscarinic antagonists

Long‐acting muscarinic antagonists (LAMAs) are anticholinergic agents that block the action of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine. The LAMA tiotropium has gained widespread acceptance as once‐daily maintenance therapy in stable COPD for its effects on symptoms and exacerbations (Barr 2005; GOLD). Two newer LAMAs that can be taken once daily—aclidinium bromide and glycopyrronium bromide—have recently been licensed for the maintenance treatment of people with COPD. Anticholinergic adverse effects that may occur include dry mouth, constipation and tachycardia (Tashkin 2008).

Why it is important to do this review

Several systematic reviews have looked at the risks and benefits of specific inhaled therapies compared with placebo or other inhaled therapies. However for patients or for clinicians facing patients, the question is often this: Which of the long‐acting therapy options is the most beneficial treatment option for patients no longer obtaining symptom relief from short‐acting therapies, but for whom PDE4 inhibitors or other additional therapies are not yet necessary? Two recent network meta‐analyses have focused primarily on safety outcomes (Decramer 2013; Dong 2013).

Objectives

To assess the efficacy of treatment options for patients whose chronic obstructive pulmonary disease cannot be controlled by short‐acting therapies alone. The review will not look at combination therapies usually considered later in the course of the disease.

As part of this network meta‐analysis, we will address the following issues:

How does long‐term efficacy compare between different pharmacological treatments for COPD?

Are there limitations in the current evidence base that may compromise the conclusions drawn by this network meta‐analysis? If so, what are the implications for future research?

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomised control trials (RCTs) with a parallel‐group design of at least 24 weeks' duration. Cross‐over trials were not included, as the pharmaceutical treatments under study can have long‐acting effects.

Types of participants

We included RCTs that recruited participants with a clinical diagnosis of COPD, such as ATS/ERS 2004. We looked for the following inclusion criteria.

Forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1)/forced vital capacity (FVC) ratio < 0.7, which confirms the presence of persistent airflow limitation.

-

One or more of the following key indicators.

Progressive and/or persistent dyspnoea.

Chronic cough.

Chronic sputum production.

History of exposure to risk factors (tobacco smoke, smoke from home cooking and heating fuels, occupational dusts and chemicals).

Types of interventions

We included studies that compared any of the following therapies versus any other.

LABA (formoterol, salmeterol, indacaterol).

LAMA (tiotropium, aclidinium bromide, glycopyrronium bromide).

ICS (budesonide, fluticasone, mometasone).

LABA/ICS combination (formoterol/budesonide, formoterol/mometasone, salmeterol/fluticasone).

Placebo.

Treatment classes and individual treatments were compared versus every other using a class‐model network meta‐analysis. The list of included treatments comprised commonly used agents within each class.

Participants were allowed other concomitant COPD medications as prescribed by their healthcare practitioner, provided these medications were not part of the trial treatment under study.

Types of outcome measures

For studies of six months' duration, we used end of study as time of analysis for all outcomes. For longer studies, we extracted data reported at six‐month and 12‐month intervals when available. Two measures of efficacy were chosen as outcomes because previous network meta‐analyses have primarily assessed safety outcomes (mortality, Dong 2013; exacerbations and adverse events, Decramer 2013).

Primary outcomes

Quality of life (measured as change from baseline assessed with St George's Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ)).

Trough FEV1 (change in mL from baseline).

Cost‐effectiveness

We did not carry out a formal cost‐effectiveness analysis, but we sought to identify economic evaluations that have compared the included interventions to supplement the main systematic review of effects. These are summarised in a short commentary in the discussion.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

To avoid duplication of effort, we first identified RCTs for inclusion by searching for relevant Cochrane systematic reviews. Cochrane systematic reviews use extensive search strategies that include several databases, manufacturers' websites and handsearching of conference abstracts. We searched the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR) in The Cochrane Library (2013, Issue 7) to look for all Cochrane systematic reviews on COPD, using the search strategy provided in Appendix 1, and from those, we handpicked the reviews that included relevant comparisons. From these reviews, we identified individual RCTs that met our inclusion criteria.

In addition, we ran a search on the Cochrane Airways Group Register (CAGR) of trials (see Appendix 2 for details of the Register) to find studies that may have been missed in the review search (e.g. because of discrepancies in inclusion criteria between individual reviews and this network, as a result of review searches more than 12 months out of date or when no reviews existed for a particular comparison). The search was done according to guidance provided in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011) and in consultation with an information specialist (see Appendix 3 for the search strategy). No date or language restrictions were applied. We searched NHS Economic Evaluation Database (EED) and Health Economic Evaluations Database (HEED) for economic evaluations using the strategy provided in Appendix 1, adapted as appropriate.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

One review author assessed for inclusion all potentially eligible reviews retrieved through the search and assessed all potentially eligible RCTs within these reviews (KMK). The CAGR database search was sifted by the same review author, and uncertainties were resolved by discussion with a second review author (CJC).

Data extraction and management

For the following characteristics, one review author extracted information for all included RCTs from their published reports (KMK) if they were already included in a Cochrane review.

Individual trial study characteristics (design, duration, location, participant inclusion/exclusion criteria, funding).

Trial arms of interest (drug, dose, inhaler type, allowed co‐medications).

Individual trial population details: mean baseline lung function, pack‐years, age and % male.

Individual trial outcome data.

Information from studies identified in other reviews was subsequently cross‐checked (data in each of the existing reviews were extracted and verified by at least two review authors). Inconsistencies and uncertainties were resolved by consultation with a second review author (CJC).

Assessing transitivity (similarity of participants, interventions and trial methodology)

The sets of trials for each treatment must be similar in their distribution of effect modifiers to permit conclusions based on a network meta‐analysis combining direct and indirect evidence (Cipriani 2013). We constructed summary tables organised by class pair‐wise comparisons (e.g. LABA vs ICS, LAMA vs placebo) to assess clinical and methodological similarities of the trials and their populations.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Although existing reviews were used to identify RCTs, data and methodological quality were dealt with at an individual trial level. One review author extracted information related to risk of bias for all trials and subsequently cross‐checked judgements from existing reviews, standardising ratings across them for consistency. Judgements were made for the following domains in each study in accordance with recommendations provided in Chapter 8 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2012).

Random sequence generation (selection bias).

Allocation concealment (selection bias).

Blinding (performance bias and detection bias).

Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias).

Selective reporting.

We did not exclude trials on the basis of risk of bias but conducted sensitivity analyses to explore the effects of including unblinded study comparisons.

Measures of treatment effect

Direct pairwise meta‐analysis

We analysed data for the two continuous outcomes as fixed‐effect mean differences (MDs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and a fixed‐effect model. The fixed‐effect model assumes that each study is estimating exactly the same intervention effect, and the random‐effects model assumes that estimated intervention effects are not all the same but follow a normal distribution across studies.

Data were extracted and analysed as change from baseline in all studies, and this was extracted from text or tables or was calculated from figures when necessary. Associated variance for change per arm was not always available (or could not be derived from the presented information), and in these cases we used available data from other trials to estimate a population variance. For SGRQ and trough FEV1, we calculated the mean of available standard deviations (SDs) for change scores, which was weighted by sample size.

Network meta‐analysis

We conducted a network meta‐analysis (NMA) to estimate the effect for each class and for each individual intervention using Markov chain Monte Carlo methods implemented in WinBUGS 1.4.3. Analyses were based on a class model, which assumes that effects of individual treatments within a class are exchangeable and are distributed around a class mean (Cooper 2009). Correlations in multiarm trials were accounted for in the model, which was adapted from Dias 2013. Non‐informative normal priors were used for class effects, and Uniform (0,5) and (0,100) prior distributions were used for between‐trials and between‐classes heterogeneity SDs for SGRQ and FEV1, respectively. Three chains with different initial values were run simultaneously to assess convergence using Brooks‐Gelman–Rubin diagnostic plots. The first 20,000 (fixed‐effect models) or 40,000 iterations (random‐effects models) were discarded, and 50,000 further iterations were run, on which all estimates are based. We decided whether to use a fixed‐effect or a random‐effects approach on the basis of model fit statistics and deviance information criteria (DIC) (Dias 2013; Spiegelhalter 2002), as well as the amount of heterogeneity present in the pair‐wise meta‐analyses. The model with lower values on the DIC was preferred, with differences of three or more units considered meaningful. If two models had similar DIC, the simplest model (i.e. fixed‐effect) was preferred.

Unit of analysis issues

No unit of analysis issues were noted, as we did not analyse any dichotomous data.

Dealing with missing data

When data or study characteristics were not reported in the primary publication, we searched clinical trial reports, trial registries and drug company websites to look for additional data. When possible, we used data from intention‐to‐treat (ITT) analyses from all randomly assigned participants.

Assessment of heterogeneity

In the presence of statistical heterogeneity (I2 > 30%) in the direct pair‐wise meta‐analysis, we analysed data using a random‐effects model and investigated possible sources. They could be of a clinical and methodological nature (i.e. differences between individual studies) in study design (inclusion/exclusion criteria, study duration), participants' baseline characteristics (disease severity, co‐morbidities, age, gender), risk of bias (open vs blinded studies) or study sponsorship. The extent of heterogeneity observed informed our decision of whether to use fixed‐effect or random‐effects models for the network meta‐analysis.

For the network meta‐analysis, we assessed the extent to which direct evidence and indirect evidence were consistent both qualitatively and statistically (Dias 2013a; Lu 2006). Consistency refers to the agreement between direct and one or more indirect sources of evidence in a “closed loop” of trials (i.e. a path by which three or more trials are connected, starting and ending with the same node) (Lu 2006). We assessed consistency by comparing model fit from a consistency and 'independent mean effects' model and by informally comparing output from the NMA versus estimates from the pair‐wise meta‐analyses. We used this global test to determine the presence of inconsistency and to locate areas in the network at which large inconsistencies were present. The output from the network meta‐analysis was informally compared with estimates from the pair‐wise meta‐analyses to check for broad agreement. When evidence of inconsistency was found, we further investigated potential sources of inconsistency using the node‐split approach (Dias 2010), as this was most appropriate given the structure of the networks. In cases in which substantial inconsistency was identified, we explored factors, including participant and design characteristics, that might contribute to inconsistency, and we restricted our analysis to a subset of trials for which the evidence might be more comparable.

Assessment of reporting biases

We tried to minimise reporting bias from non‐publication of studies or selective outcome reporting by using a broad search strategy, and by checking references of included studies and relevant systematic reviews. For each outcome, we commented on the proportion of studies contributing data to the analysis.

Data synthesis

Using a class‐model network meta‐analysis, we modelled the relative effectiveness of any two classes as a function of each class relative to a reference treatment (placebo). We prespecified five unique classes of interventions (or nodes) in the network: LABA (salmeterol, formoterol and indacaterol), LAMA (tiotropium, aclidinium bromide and glycopyrronium bromide), ICS (fluticasone, budesonide and mometasone), LABA/ICS (salmeterol/fluticasone, formoterol/budesonide and formoterol/mometasone) and placebo. We estimated the probability that each class ranks at one of the five possible positions (e.g. the best, second best, third best). We obtained estimates of each overall class effect, as well as of the effects of each treatment within the class compared with every other. Estimates for within‐class variability in treatment effects, as well as for between‐class variability in treatment effects, are presented, as are ranking probabilities, in tables and figures as appropriate.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We planned to perform subgroup analyses based on baseline disease severity and dose, provided that treatments could be compared indirectly with other trial comparisons through one or more common comparators (i.e. the networks remained 'connected'). However, differences in individual doses were built into the network structure, and baseline disease severity was assessed across nodes as part of the transitivity assessment.

For the network meta‐analysis, available data were insufficient to include baseline severity as a co‐variate as a way of exploring subgroup effects. We extracted key severity criteria for each trial individually, and we summarised the data across pair‐wise comparisons to investigate potential differences.

Sensitivity analysis

We assessed the robustness of our analyses by performing sensitivity analyses, excluding studies from the overall analysis of high risk of bias due to lack of blinding (participants and personnel and/or outcome assessors), and by considering separately studies of different duration.

Results

Description of studies

Basic study characteristics, including duration, intervention details and population characteristics, are summarised in Table 1, and full details of each included study can be found in Characteristics of included studies.

1. All included studies—summary characteristics.

| Study ID | Weeks | Arms includeda | N | Ageb | % male | % pred FEV1b | Pack‐yearsb |

| Abrahams 2013 | 24 | tiotropium, placebo | 856 | 64.2 | 64.9 | 43.3 | 46.9 |

| ACCLAIM 2009 | 52 | aclidinium, placebo | 843 | 62.4 | 78.6 | 53.9 | 39.9 |

| ACCLAIM II 2009 | 52 | aclidinium, placebo | 804 | 65.1 | 63.0 | 50.3 | 57.9 |

| Anzueto 2009 | 52 | salmeterol, salmeterol/fluticasone | 797 | 65.4 | 54 | 34.0 | 57.2 |

| ATTAIN 2011 | 24 | aclidinium (2), placebo | 828 | 62.4 | 67.4 | 52.5 | 40.2 |

| Bateman 2010a | 48 | tiotropium, placebo | 3991 | 64.8 | 77.6 | 39.9 | 46 |

| Bateman 2010b | 48 | tiotropium (2), placebo | 1990 | 65.0 | 74.2 | 37.7 | nr |

| Bateman 2013 [SHINE] | 26 | indacaterol, tiotropium, glycopyrronium, placebo | 1667 | 64.0 | 74.9 | 55.0 | nr |

| Bourbeau 1998 | 26 | budesonide, placebo | 79 | 66 | 78.6 | 36.5 | 51 |

| Brusasco 2003 | 26 | salmeterol, tiotropium, placebo | 1207 | 64.2 | 76.3 | 38.5 | 43.8 |

| Burge 2000 [ISOLDE] | 156 | fluticasone, placebo | 751 | 63.8 | 74.6 | 50.2 | 44 |

| Calverley 2003a | 52 | formoterol, budesonide, formoterol/budesonide, placebo | 1122 | 64 | 76 | 36 | 39 |

| Calverley 2003 [TRISTAN] | 52 | salmeterol, fluticasone, salmeterol/fluticasone, placebo | 1466 | 63.2 | 72.5 | 44.7 | 42.3 |

| Calverley 2003b | 52 | mometasone, placebo | 631 | nr | nr | 47 | nr |

| Calverley 2007 [TORCH] | 156 | salmeterol, fluticasone, salmeterol/fluticasone, placebo | 6185 | 65.0 | 75.8 | 44.0 | 48.5 |

| Calverley 2008 | 52 | mometasone (2), placebo | 911 | 65.1 | 68.3 | 42.3 | nr |

| Calverley 2010 | 48 | formoterol, formoterol/budesonide | 718 | 63.9 | 81.3 | 42.4 | 38.8 |

| Campbell 2005 | 26 | formoterol, placebo | 432 | 55 | 67 | 53.6 | 37 |

| Casaburi 2002 | 52 | tiotropium, placebo | 921 | 65 | 65.0 | 38.7 | 61.4 |

| Chan 2007 | 48 | tiotropium, placebo | 913 | 66.8 | 59.7 | 39.4 | 50.6 |

| Cooper 2010 | 104 | tiotropium, placebo | 519 | 64.6 | 77.3 | 38.2 | 51.7 |

| Dahl 2010 | 52 | formoterol, placebo | 867 | 63.5 | 31.9 | 51.7 | 40.8 |

| Dal Negro 2003 | 52 | salmeterol, salmeterol/fluticasone, placebo | 18 | nr | 83.3 | 50.0 | 41.4 |

| Doherty 2012 | 26 | formoterol, mometasone, formoterol/mometasone (2), placebo | 1196 | 59.7 | 75.2 | 38.6 | 45.1 |

| Donohue 2010 [INHANCE] | 26 | indacaterol (2), tiotropium, placebo | 1683 | 63.6 | 62.8 | 55.6 | 49.7 |

| Dusser 2006 | 48 | tiotropium, placebo | 1010 | 64.7 | 88 | 47.9 | nr |

| Fang 2008 | 52 | tiotropium, salmeterol/fluticasone | 126 | 62.5 | 73.8 | nr | nr |

| Ferguson 2008 | 52 | salmeterol, salmeterol/fluticasone | 782 | 64.9 | 55 | 32.8 | 56.5 |

| FLTA3025 | 26 | fluticasone (2), placebo | 640 | 64.4 | 68.8 | nr | nr |

| Gelb 2012 | 52 | aclidinium (2) | 605 | nr | nr | 46.5 | nr |

| GLOW1 2011 | 26 | glycopyrronium, placebo | 822 | 63.9 | 81.8 | 54.6 | 44.8 |

| GLOW2 2012 | 52 | glycopyrronium, tiotropium, placebo | 1066 | 63.6 | 64.2 | 56.0 | 49.1 |

| Hanania 2003 | 26 | salmeterol, fluticasone, salmeterol/fluticasone, placebo | 723 | 63.9 | 63.1 | 42 | 56.5 |

| Kardos 2007 | 43 | salmeterol, salmeterol/fluticasone | 994 | 63.9 | 75.8 | 40.4 | 36.9 |

| Kornmann 2011 | 26 | salmeterol, placebo | 339 | 63.3 | 74.7 | 53.3 | 40.3 |

| Lapperre 2009 | 130 | fluticasone (2), salmeterol/fluticasone, placebo | 114 | 61 | 86.6 | 55.3 | 44.3 |

| Laptseva 2002 | 26 | budesonide, placebo | 49 | nr | nr | nr | nr |

| Mahler 2002 | 26 | salmeterol, fluticasone, salmeterol/fluticasone, placebo | 674 | 63.5 | 65.8 | 41 | 40.8 |

| Mahmud 2007 | 26 | salmeterol, tiotropium | 90 | nr | 91 | nr | nr |

| Niewoehner 2005 | 26 | tiotropium, placebo | 1829 | 67.9 | 98.5 | 35.6 | 68.4 |

| Ohar 2013 | 26 | salmeterol, salmeterol/fluticasone | 639 | nr | nr | nr | nr |

| Ozol 2005 | 26 | budesonide, placebo | 26 | 65.4 | 69.2 | 59.2 | 45.0 |

| Paggiaro 1998 | 26 | fluticasone, placebo | 281 | 63 | 74 | 57 | nr |

| Pauwels 1999 | 156 | budesonide, placebo | 1277 | 52.5 | 72.9 | 76.9 | 39.3 |

| Powrie 2007 | 52 | tiotropium, placebo | 142 | 66.4 | 62.9 | 50.0 | 55.2 |

| Renkema 1996 | 104 | budesonide, placebo | 39 | 55 | 100 | 63.5 | nr |

| Rennard 2009 | 52 | formoterol, budesonide, formoterol/budesonide, placebo | 1964 | 63.2 | 63.9 | 39.6 | 40 (med) |

| Rossi 2002 | 52 | formoterol (2), placebo | 645 | 62.7 | 83.3 | nr | nr |

| Schermer 2009 | 156 | fluticasone, placebo | 190 | 59.0 | 70.5 | 64.5 | 28.3 |

| SCO100470 | 26 | salmeterol, salmeterol/fluticasone | 1050 | 63.6 | 77.8 | nr | nr |

| SCO30002 | 52 | salmeterol/fluticasone, fluticasone, placebo | 387 | 64.8 | 82 | nr | nr |

| SCO40041 | 156 | salmeterol, salmeterol/fluticasone | 186 | 65.7 | 61.3 | nr | nr |

| Senderovitz 1999 | 26 | budesonide, placebo | 26 | 60.5 | 53.5 | nr | nr |

| Shaker 2009 | 104+ | budesonide, placebo | 254 | 63.6 | 58.3 | 52 | 56 |

| Sharafkhaneh 2012 | 52 | formoterol, budesonide/formoterol (2) | 1219 | 63.0 | 62.0 | 37.7 | 44.3 |

| SLMF4010 | 26 | salmeterol, placebo | 34 | 63.8 | 88.3 | nr | nr |

| SPARK 2013 | 64 | tiotropium (OL), glycopyrronium | 1483 | 63.4 | 74.1 | nr | nr |

| Szafranski 2003 | 52 | formoterol, budesonide, formoterol/budesonide, placebo | 812 | 64 | 78.8 | 36.2 | 44.5 |

| Tashkin 2008 [SHINE] | 26 | formoterol, budesonide, formoterol/budesonide (3), placebo | 1704 | 63.4 | 66.9 | 39.9 | 40 (med) |

| Tashkin 2008a [UPLIFT] | 208 | tiotropium, placebo | 5993 | 64.5 | 74.7 | 39.4 | 48.7 |

| Tashkin 2012 | 26 | formoterol, mometasone, formoterol/mometasone (2), placebo | 1055 | 59.8 | 77.5 | nr | 40.4 |

| To 2011 | 52 | salmeterol, indacaterol | 186 | 69.1 | nr | 53 | nr |

| Tonnel 2008 [TIPHON] | 39 | tiotropium, placebo | 554 | 64.2 | 86.1 | 46.9 | 43.7 |

| Trooster 2011 | 24 | tiotropium, placebo | 457 | 61.8 | 68.4 | nr | nr |

| Verhoeven 2002 | 26 | fluticasone, placebo | 23 | 55 | 82.3 | 63.5 | 25.5 |

| Vestbo 1999 | 156 | budesonide, placebo | 290 | 59.1 | 87.5 | 86.6 | nr |

| Vogelmeier 2008 | 26 | formoterol, tiotropium, placebo | 640 | 62.6 | 77.5 | 51.4 | 38.0 |

| Vogelmeier 2011 [POET] | 52 | salmeterol, tiotropium | 7384 | 62.9 | 74.7 | 49.3 | 38.3 |

| Wedzicha 2008 [INSPIRE] | 104 | tiotropium, salmeterol/fluticasone | 1323 | 64.5 | 82.5 | 39.3 | 40.4 |

| Zheng 2006 | 24 | salmeterol/fluticasone, placebo | 448 | 66.3 | 88.6 | nr | nr |

| Zhong 2012 | 24 | budesonide, formoterol/budesonide | 308 | 65.2 | 95.1 | 32.7 | nr |

aNumbers in parentheses indicate multiple doses of the same treatment.

bAge, % predicted FEV1 and pack‐years smoked are reported as means unless otherwise stated.

bid = twice daily.

FEV1 = forced expiratory volume in one second.

ICS = inhaled corticosteroid.

LABA = long‐acting beta2‐agonist.

LABA/ICS = long‐acting beta2‐agonist/inhaled corticosteroid combination therapy.

LAMA = long‐acting muscarinic antagonist.

nr = not reported.

PBO = placebo inhaler.

qd = once daily.

Results of the search

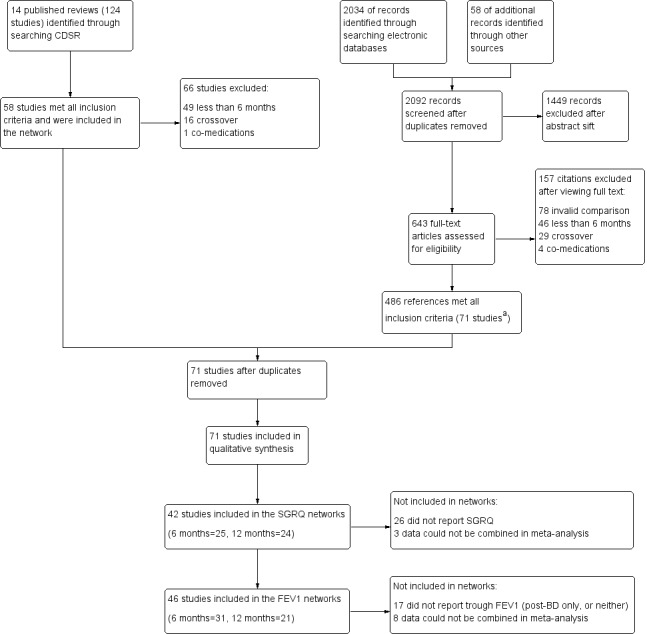

Results of the search are presented in Figure 1, broken down by the search for Cochrane reviews on the left and the electronic database search on the right.

1.

Study flow diagram. aAll 58 studies identified in the review search were also identified in the electronic database search. Abbreviations: CDSR = Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews.

Fourteen relevant Cochrane reviews were identified (Chong 2012; Geake 2012; Karner 2011; Karner 2011a; Karner 2012; Karner 2012a; Kew 2013; Kew 2014; Nannini 2012; Nannini 2013; Nannini 2013a; Spencer 2011; Welsh 2013; Yang 2012a), including a total of 124 studies. Sixty‐six studies were excluded because of differences in the reviews' inclusion criteria, most commonly, 'duration less than six months' (n = 49), and 'cross‐over design' (n = 16). The remaining 58 studies were included in the review.

Searching the CAGR of trials returned 2034 references, and 58 additional references were identified by searching reference lists and drug company websites. We excluded 1449 references after sifting titles and abstracts, and we reviewed full texts after studification for the remaining 643. Four hundred eighty‐six references met all inclusion criteria, most of which related to the 58 studies identified from the review search. The remaining references were collated into 13 additional studies that met the inclusion criteria. The most common reasons for excluding citations after viewing full texts were 'invalid comparison for this review' (n = 78), 'duration less than six months' (n = 46) and 'cross‐over design' (n = 29).

Included studies

Seventy‐one studies met the inclusion criteria, randomly assigning 73,062 people with a diagnosis of COPD to 184 treatment arms of interest (including placebo). The number of participants included in the trials ranged from 18 (Dal Negro 2003) to 7384 (Vogelmeier 2011 [POET]); the mean number per arm of a trial was 397. Table 1 lists all 71 studies that met the inclusion criteria, along with their total duration, treatment arms relevant to the network and summary characteristics for each study population. Table 2 and Table 3 present pooled characteristics for each class and for individual nodes within them for studies contributing data to the SGRQ and trough FEV1 data sets, respectively.

2. SGRQ network composition and transitivity assessmenta.

| Comparison | Comparisons | N | Ageb | % male | % FEV1c | Packsd |

| LABA vs placebo | 16 | 13,808 | 62.9 | 74.7 | 46.2 | 42.5 |

| LAMA vs placebo | 15 | 22,406 | 64.2 | 71.3 | 47.1 | 47.5 |

| ICS vs placebo | 10 | 8153 | 63.4 | 74.9 | 41.7 | 42.7 |

| LABA/ICS vs placebo | 10 | 9097 | 63.1 | 75.3 | 39.7 | 42.4 |

| LABA vs LAMA | 2 | 2680 | 63.7 | 69.5 | 55.2 | 49.7 |

| LABA vs ICS | 7 | 6226 | 62.7 | 73.8 | 40.0 | 42.7 |

| LABA vs LABA/ICS | 13 | 12,505 | 63.1 | 71.0 | 38.8 | 43.9 |

| LAMA vs ICS | 0 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| LAMA vs LABA/ICS | 1 | 1323 | 64.5 | 82.5 | 39.3 | 40.4 |

| ICS vs LABA/ICS | 10 | 8721 | 62.9 | 75.3 | 38.8 | 42.9 |

aSummary population data are for all study comparisons excluding those made in the 29 studies that could not be included in either the six‐month or the 12‐month SGRQ network.

bAge = mean years.

c% FEV1 = mean percentage predicted FEV1.

dPacks = mean pack‐years.

FEV1 = forced expiratory volume in one second.

ICS = inhaled corticosteroid.

LABA = long‐acting beta2‐agonist.

LABA/ICS = long‐acting beta2‐agonist/inhaled corticosteroid combination therapy.

LAMA = long‐acting muscarinic antagonist.

SGRQ = St George's Respiratory Questionnaire.

3. FEV1 network composition and transitivity assessmenta.

| Comparison | Comparisons | N | Ageb | % male | %FEV1c | Packsd |

| LABA vs Placebo | 13 | 8680 | 63.3 | 73.2 | 47.7 | 43.9 |

| LAMA vs Placebo | 16 | 23,111 | 64.3 | 72.2 | 47.6 | 48.9 |

| ICS vs Placebo | 12 | 4574 | 63.6 | 71.9 | 46.2 | 45.2 |

| LABA/ICS vs Placebo | 9 | 4978 | 63.9 | 73.5 | 41.6 | 44.4 |

| LABA vs LAMA | 2 | 2680 | 63.7 | 69.5 | 55.2 | 49.7 |

| LABA vs ICS | 5 | 2506 | 63.6 | 67.1 | 40.6 | 46.7 |

| LABA vs LABA/ICS | 12 | 8005 | 63.7 | 68.8 | 39.9 | 45.8 |

| LAMA vs ICS | 0 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| LAMA vs LABA/ICS | 0 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| ICS vs LABA/ICS | 8 | 4560 | 63.6 | 71.7 | 39.0 | 45.5 |

aSummary population data are for all study comparisons excluding those made in the 23 studies that could not be included in either the six‐month or the 12‐month FEV1 network; all doses are given in micrograms.

bAge = mean years.

c% FEV1 = mean percentage predicted FEV1.

dPacks = mean pack‐years.

FEV1 = forced expiratory volume in one second.

ICS = inhaled corticosteroid.

LABA = long‐acting beta2‐agonist.

LABA/ICS = long‐acting beta2‐agonist/inhaled corticosteroid combination therapy.

LAMA = long‐acting muscarinic antagonist.

Design and duration

All of the studies were parallel‐group, randomised controlled trials, and most were conducted at multiple centres in several countries. A vast majority were double‐blind; five included one open‐label treatment (see sensitivity analyses), a subset were double‐blind and double‐dummy and blinding was unclear in four others.

All studies had a randomly assigned treatment period of at least 24 weeks. Similar numbers of six‐month and 12‐month studies were identified (n = 30 and n = 29, respectively), but six‐month data were available in a number of the longer trials. Twelve studies lasted between two and four years (Burge 2000 [ISOLDE]; Calverley 2007 [TORCH]; Cooper 2010; Lapperre 2009; Pauwels 1999; Renkema 1996; Schermer 2009; SCO40041; Shaker 2009; Tashkin 2008a [UPLIFT]; Vestbo 1999; Wedzicha 2008 [INSPIRE]). For these studies, we used data measured and reported for six and 12 months in the NMA, rather than endpoint. Data entered in the six‐month analysis were reported between 24 and 32 weeks, and data included in the 12‐month networks were measured between 44 and 56 weeks in the individual studies.

Participant inclusion and exclusion criteria

The trials were relatively consistent in their key inclusion and exclusion criteria. All studies required a clinical diagnosis of COPD, and most specified that this was in accordance with recent guidelines (usually ATS/ERS 2004 or GOLD). The cutoff for forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) expressed as the percentage predicted normal value ranged from 50% to 80%. Additional inclusion criteria that were common across trials were these: smokers or ex‐smokers with a smoking history of at least 10 pack‐years, 40 years of age or older and FEV1/FVC ratio less than 70%.

Exclusion criteria that were common across most trials were these: history of asthma or other respiratory disease, any significant disease other than COPD and the need for supplemental oxygen. Patients who had a COPD exacerbation or upper respiratory tract infection in the run up to screening (usually within four to six weeks) were usually excluded. Trials often listed additional exclusion criteria specific to the drugs under study, such as sensitivities to active ingredients, or medical conditions that might be affected by known adverse effects.

Baseline characteristics of participants in the trials

Baseline characteristics are presented for all included studies in Table 1, and for the subsets of studies contributing data to the SGRQ and FEV1 analyses in Table 2 and Table 3, respectively.

In the SGRQ data set, the overall mean age per class was very similar, ranging from 62.9 to 64.5 years. In the FEV1 data set, the overall mean age for each comparison was also very similar, ranging from 63.3 to 64.3. Both data sets consistently included more men than women, and the means of trial percentages were similar between and within comparisons (SGRQ range 69.5% to 82.5%, FEV1 range 67.1% to 73.2%). As might be expected from variation in inclusion criteria, greater variability was noted in the summary statistics for percentage predicted FEV1, with the LABA versus LAMA comparison having somewhat higher scores in both data sets than the other classes (both means around 55% compared with 39% to 47% in the other comparisons). Overall, most population means for percentage predicted FEV1 were less than 50% predicted. Mean pack‐years were between 40 and 50 for all comparisons in both data sets. In general, the data indicated a fairly consistent moderate to severe population across both outcome data sets and across direct between‐class comparisons, which satisfied the transitivity assumption.

Characteristics of the interventions

Table 4 shows the distribution of treatment arms across all 71 included studies, organised by the five prespecified treatment classes. The text below summarises information about all 71 included studies. Table 2 and Table 3 show the number of studies making each class comparison represented in the SGRQ or FEV1 analyses, respectively.

4. Distribution of studies by individual treatment node.

aStudies not contributing data to either outcome.

bid = twice daily.

ICS = inhaled corticosteroid.

LABA = long‐acting beta2‐agonist.

LABA/ICS = long‐acting beta2‐agonist/inhaled corticosteroid combination therapy.

LAMA = long‐acting muscarinic antagonist.

PBO = placebo inhaler.

qd = once daily.

Lists of allowed co‐medications varied between studies, but participants were always allowed a short‐acting beta‐agonist reliever inhaler and short‐term treatment for exacerbations during the randomised period (course of oral corticosteroids or antibiotics).

1. Long‐acting beta2‐agonists (LABAs)

Thirty‐seven LABA treatment arms were identified across 30 studies (n = 15,266). Twelve studies included a formoterol arm with treatment given at 12 mcg twice daily, and Rossi 2002 also randomly assigned participants to a higher dose of twice‐daily 24 mcg. Formoterol was most commonly given via a dry powder inhaler but sometimes via a metered‐dose inhaler (to retain blinding in the newer multiarm mometasone studies). Salmeterol was given at 50 mcg twice daily in 17 studies (n = 9019), primarily via the Diskus device. Indacaterol, a once‐daily preparation, was given as 150 mcg in three studies (Bateman 2013 [SHINE]; Donohue 2010 [INHANCE]; Kornmann 2011) and as 300 mcg in three studies (Dahl 2010; Donohue 2010 [INHANCE]; To 2011), one of which also used a higher dose of 600 mcg. Donohue 2010 [INHANCE] was conducted in two stages, and the data derived are for the four randomly assigned groups from stage 2.

2. Long‐acting muscarinic antagonists (LAMAs)

Thirty‐four LAMA treatment arms were included across 28 studies (n = 21,805). Most studies used tiotropium 18 mcg daily, delivered most often via the HandiHaler. Six studies included two arms that met criteria for inclusion in the LAMA category: Bateman 2010b used two tiotropium doses (5 and 10 mcg daily via Respimat), ATTAIN 2011 and Gelb 2012 used two aclidinium doses (200 and 400 mcg daily) and Bateman 2013 [SHINE], GLOW2 2012 and SPARK 2013 included both glycopyrronium 50 mcg and open‐label tiotropium. Two additional glycopyrronium studies used 50 mcg via the Breezhaler, and two other aclidinium studies used the lower of the two doses via the Genuair device. Two other tiotropium studies used the Respimat device to deliver 5 mcg daily (Abrahams 2013 and Bateman 2010a).

3. Inhaled corticosteroids (ICSs)

Twenty‐seven studies included an ICS arm (n = 6788), with two including two doses of the same drug that were relevant to the review (Calverley 2008; FLTA3025). Twelve studies (n = 3491) reported a fluticasone arm: two studies used 250 mcg twice daily, and the rest 500 mcg, delivered most often via the Diskus device. Twelve studies with around half as many people used budesonide (n = 1900): two at the higher dose of 800 mcg twice daily, and the rest at 400 mcg, with both doses delivered via dry powder inhalers. Mometasone was used in four studies (n = 1397) and was given as 400 mcg twice daily or 800 mcg once daily.

4. Long‐acting beta2‐agonist/inhaled corticosteroid combinations (LABA/ICS)

Thirty LABA/ICS treatment arms were identified in 25 studies (n = 9727). Three studies used two budesonide doses (160 mcg and 320 mcg; Rennard 2009; Sharafkhaneh 2012; Tashkin 2008 [SHINE]), and seven additional studies used only the higher dose (total N = 3221). Two identically designed studies included two formoterol/mometasone doses each, 200 and 400 mcg (n = 888). Sixteen studies had a salmeterol/fluticasone arm (n = 5618), six at the lower ICS dose of 50/250 mcg and 11 at the higher dose of 50/500 mcg. All LABA/ICS inhalers were prescribed for twice‐daily use and drugs were delivered by dry powder or pressurised metered‐dose inhalers.

5. Placebo

Most studies included a placebo control arm (n = 55), which consisted of a total of 19,476 people. Inhalers varied across studies depending on the device used to deliver the study drugs. Once‐daily and twice‐daily placebos were combined in the same node as the reference treatment to increase the number of comparisons that could be made.

Transitivity (similarity of participants, interventions and trial methodology)

Inclusion and exclusion criteria, as described above, did not vary systematically across classes; although variation in the allowed co‐medications and in the maximum allowed percentage predicted FEV1 was noted, these did not translate to systematic differences in the characteristics of the recruited population.

Baseline characteristics were varied between individual trials, but summary baseline characteristics were comparable across pair‐wise comparisons between classes for both outcome data sets (see above and Table 2; Table 3). Mean percentage predicted FEV1 was somewhat higher in the LABA versus LAMA comparisons conducted in two studies (55% vs 39% to 47% in the other comparisons).

Intervention characteristics introduced some potential sources of systematic variation between trials, notably as a result of the devices used and the dosing schedule. However, as all nodes showed variation in the delivery device used and in once‐daily and twice‐daily regimens, we did not consider these factors to violate assumptions needed for indirect comparisons. The placebo‐controlled trials used matching inhalers to control for bias at a trial level, and variation within classes was similar, so we considered a combined placebo class valid as the reference treatment (regardless of device or dosing regimen).

Methodology was similar across trials, and no issues with the comparability of trial duration arose, as we included only data relevant to the time points specified. Funding sources varied across classes, depending on the drug manufacturers, but this variability did not translate into systematic differences in the way that trials were conducted, nor in the populations recruited (i.e. similar inclusion criteria, baseline characteristics and study designs). Average sample size per class was higher in the LAMA trials (659 and 633 for SGRQ and FEV1, respectively) than in the four other classes (range 189 to 471 across both outcome data sets), but variation within the classes was comparable.

Outcomes and analysis structure

For both outcomes, the overall fit of the network meta‐analysis class model was compared with the fit of a class model without the consistency assumption (broadly equivalent to a pair‐wise meta‐analysis with random class effects), using the total residual deviance. Statistical inconsistency was not significant on SGRQ at 12 months nor on the FEV1 analyses (six and 12 months). However some evidence of inconsistency was noted in the network for SGRQ at six months. This was investigated further using the node‐split approach (Dias 2010), which found some evidence of inconsistency (P value 0.01, although multiple comparisons were made) in the direct evidence comparing indacaterol 150 mcg and tiotropium 18 mcg. We investigated the possible clinical explanation for this inconsistency and found that studies directly comparing these two treatments delivered tiotropium open‐label, which affected comparability with other tiotropium studies, and increased risk of bias (see sensitivity analyses). The dose was misclassified in one study comparing salmeterol versus salmeterol/fluticasone combination (salmeterol/fluticasone as 50/500 bid instead of 50/250). Because the study did not appear in the main six‐month results nor change the class comparisons, we did not rerun the analyses.

St George's Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ)

The SGRQ is a well‐validated and widely used measure of health status in patients with chronic airflow limitation; the total score ranges from zero (perfect health) to 100 (most severe status) and includes the three components of symptoms, activity and impacts.

In the main network of effects at six months, 18 of 25 possible treatments were represented across 72 treatment arms in 25 studies (n = 27,024). The fixed‐effect model was preferred, as statistical heterogeneity was not significant. We extracted and analysed data as change from baseline per arm and estimated population variance on the basis of data from studies reporting variance for change per arm (see Measures of treatment effect). The mean of SDs, weighted by sample size, was imputed as 14 when variance for change could not be obtained.

The 12‐month analysis contained slightly fewer data and had a broadly similar structure (containing data for 19 treatment comparisons in 24 studies). The fixed‐effect model was preferred, as with the six‐month analysis, but Calverley 2003 [TRISTAN] showed some lack of fit. Data from four studies were removed from the six‐month network in the blinding sensitivity analysis (Bateman 2013 [SHINE]; Donohue 2010 [INHANCE]; GLOW2 2012; SPARK 2013), and data from two studies were removed from the 12‐month network (GLOW2 2012; SPARK 2013).

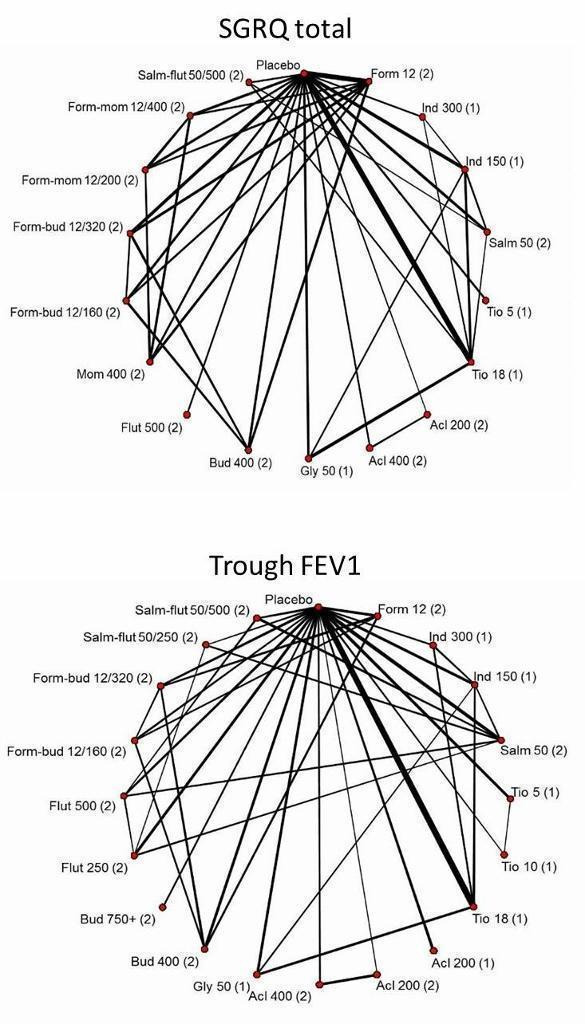

The network structure for SGRQ at six months is shown in Figure 2.

2.

Network structures for both outcomes at six months.

Trough forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1)

In the main network of effects at six months, 20 of 25 possible treatments were represented across 82 treatment arms in 31 studies (n = 29,271). A random‐effects model was preferred, as the fixed‐effect model has very poor fit. Data for eight studies were available only as treatment contrasts, and the rest were entered as change from baseline per arm, along with the associated variance. For trials reporting treatment contrasts, we included co‐variance, which was calculated as the variance of the mean in the control arm (placebo for all trials). For the rest of the trials, missing variance for change from baseline was imputed as 283 (mL) from the mean of available SDs weighted by sample size.

One very small trial was excluded from the six‐month analysis (SLMF4010, n = 34) because of the unusually high dropout from already very small groups (seven of 17 dropped out in both groups). The study showed very poor fit, even in random‐effects models, because the results contradicted all other trials.

The 12‐month analysis contained fewer data (19 treatments compared in 21 studies) but again had a structure broadly similar to the main six‐month analysis. As with the six‐month analysis, the random‐effects model was preferred, as the fixed‐effect model had very poor fit. Data from the same four studies were removed from the six‐month and 12‐month networks, as for the SGRQ sensitivity analyses (see Table 5).

5. Sensitivity analysis—blinding.

| Study ID | Arm removed | Analyses affected |

| Bateman 2013 [SHINE] | Tiotropium 18 mcg | SGRQ6m, FEV6m |

| Donohue 2010 [INHANCE] | Tiotropium 18 mcg | SGRQ6m, FEV6m |

| GLOW2 2012 | Tiotropium 18 mcg | SGRQ6m, FEV6m, SGRQ12m, FEV12m |

| SPARK 2013 | Whole study (2 arms) | SGRQ6m, FEV6m, SGRQ12m, FEV12m |

| Vogelmeier 2008 | Tiotropium 18 mcg | Did not appear in analyses |

FEV = forced expiratory volume in one second

SGRQ = St George's Respiratory Questionnaire

6m = six month analysis

12m = 12 month analysis

The network structure for trough FEV1 at six months is shown in Figure 2.

Sensitivity analyses

Five studies included a randomly assigned group that received tiotropium as an open‐label treatment (Bateman 2013 [SHINE]; Donohue 2010 [INHANCE]; GLOW2 2012; SPARK 2013; Vogelmeier 2008). As this introduced the potential for performance and assessment bias, we removed these arms from the affected networks in a risk of bias sensitivity analysis, as detailed in Table 5. Blinding led to unclear or high risk of bias in four additional studies, mainly as the result of insufficient reporting, but none of the studies reported data that could be included in the networks (Fang 2008; Mahmud 2007; Ohar 2013; To 2011).

As stated in the protocol, we analysed separately data collected at six months and at 12 months.

Excluded studies

Sixty‐six studies were excluded from the 14 relevant Cochrane reviews, and five others that came up in the electronic database search are recorded in Characteristics of excluded studies. We did not record every reference excluded after the full‐text sift (n = 157), as review of the full paper revealed that most trials were apparently of less than six months' duration, or they compared treatments that were not within the scope of the study.

Risk of bias in included studies

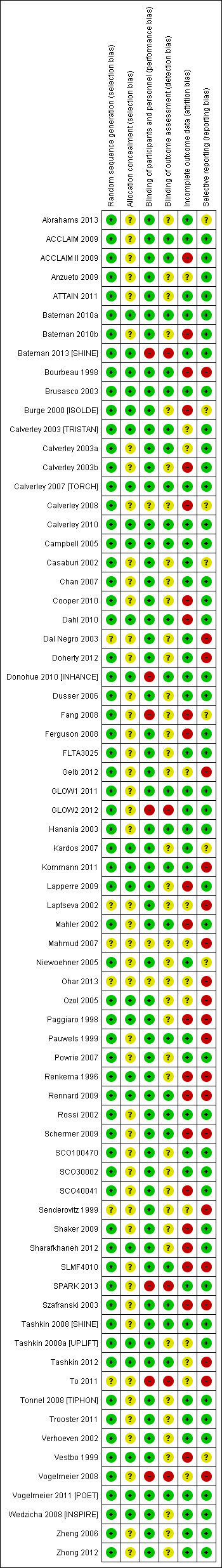

Methodological quality of the included studies was generally good. Across all six domains, around 60% of judgements were 'low risk', and 13% were 'high' risk. It is unlikely that the evidence presented in this review is affected by biases associated with unacceptable sequence generation, and most trials were double‐blinded. The most common reasons for probable bias were attrition and selective reporting in the individual trials. A degree of uncertainly regarding the risk of bias associated with allocation concealment and blinding of outcome assessors was due mostly to insufficient reporting. Risk of bias judgements for all of the included studies are summarised in Figure 3

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Random sequence generation

All studies were randomised trials, and none were given high risk ratings for either of the selection bias domains. Most were funded by drug manufacturers with whom the authors had had previous contact to confirm methods of sequence generation. As such, all studies were considered to be at low risk of bias for this domain, with the exception of six studies for which only a conference abstract was available (rated unclear). Of these, none appeared in the SGRQ data set, and only two contributed FEV1 data.

Allocation concealment

A third of studies described methods of allocation concealment (interactive voice response system or sealed envelopes) and were rated as having low risk of bias (n = 24). The remaining studies did not explicitly describe their methods and were rated as unclear. This information is likely to be conservative given the high proportion of industry‐funded trials, which generally have rigorous controls for selection bias.

Blinding

Blinding of participants and personnel

A large majority of trials stated that they were double‐blind, which, unless otherwise stated, was understood to pertain to at least participants and personnel. For this reason, more than 85% of the trials were rated at low risk for performance bias. Seven trials (10%) were given a high risk of bias rating, which was due mostly to the fact that one arm of the trial was delivered open‐label. In these instances, treatment comparisons that did not involve the open‐label arm were not affected, and sensitivity analyses removing these arms assessed the effects of removing these high‐risk comparisons from the networks.

Blinding of outcome assessors

A third of trials gave enough detail to warrant a low risk of bias rating, which was usually obtained from the clinicaltrials.gov registration. Most trials did not describe how outcomes were assessed in sufficient detail to rule out bias associated with unblinded outcome assessors and hence were rated as unclear. As with allocation concealment, an unclear rating for studies not explicitly describing outcome assessor blinding is likely to be conservative. Five studies were rated as high risk for the same reasons outlined for the participant and personnel domain.

Incomplete outcome data

Around half the trials were judged to be at low risk of bias because the level of dropout was acceptable and balanced between groups, or because sufficient efforts were made to impute missing data. Twenty‐two trials were given a high risk rating, indicating a significant risk that unbalanced or especially high attrition may have compromised the validity of the results, and 13 were rated as unclear. However, several of the high risk ratings were given to the longer trials (two years or longer), in which a significant proportion of participants had dropped out by the end of the trial. By including data at the six‐month and 12‐month time points rather than at endpoint in these unusual trials, the risk from attrition may be reduced, as higher percentages of the randomly assigned populations were generally included in the earlier analyses.

Selective reporting

Most trials could be linked to a prospectively registered protocol for cross‐checking of reported outcomes (on clinicaltrials.gov or manufacturers' websites). Most reported the named outcomes well in published reports, and a subset had additionally posted results summaries on clinicaltrials.gov, warranting a low risk rating (n = 43). A third were judged to be at high risk of bias, usually because outcomes stated in the protocol or important study methods were missing from published reports, regardless of whether this directly affected our analyses. Some trials were rated at high risk of bias because SGRQ or FEV1 data were reported but not in an acceptable format to be combined in meta‐analysis. Although some early trials did not use the SGRQ or used a different FEV1 measurement for legitimate reasons, this fact and selective outcome reporting resulted in omission of a significant proportion of relevant trials from the SGRQ and FEV1 analyses. Eight were rated as unclear, usually because a protocol could not be located to confirm that all planned outcomes had been reported.

Effects of interventions

For each outcome, we presented six‐month data for the main analyses, along with the number of treatments included, the number of pair‐wise comparisons made and estimates of model fit and heterogeneity. Results are presented first as class effects and second for individual treatments. As the class analysis assumes that treatments within the same class are exchangeable and are distributed around a class mean, we have also outlined the effects of fitting the class model on individual treatment effects.

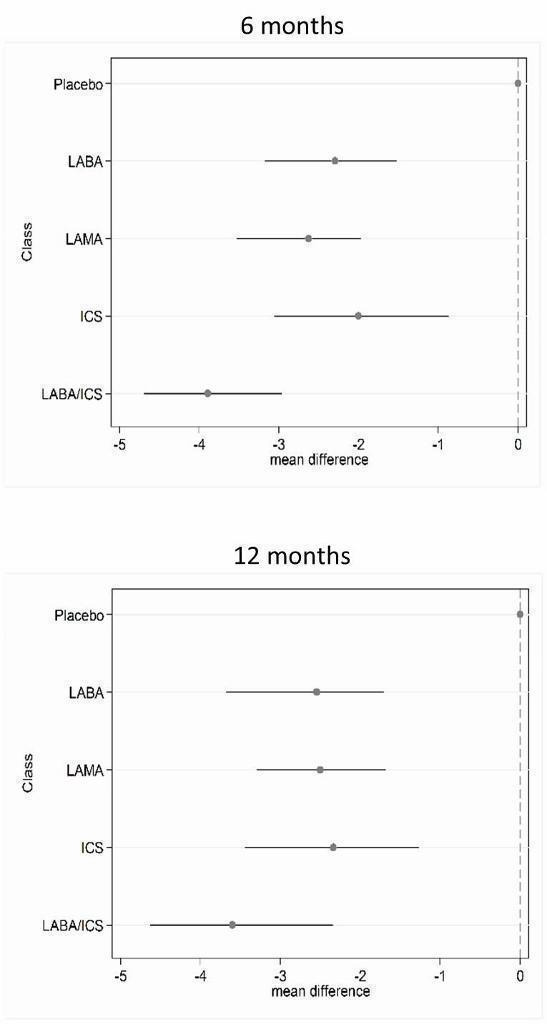

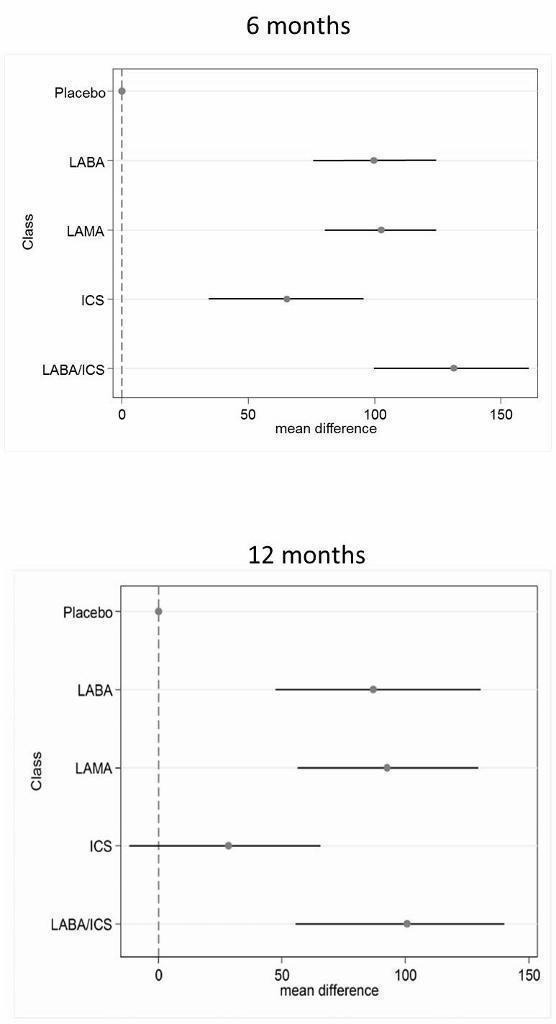

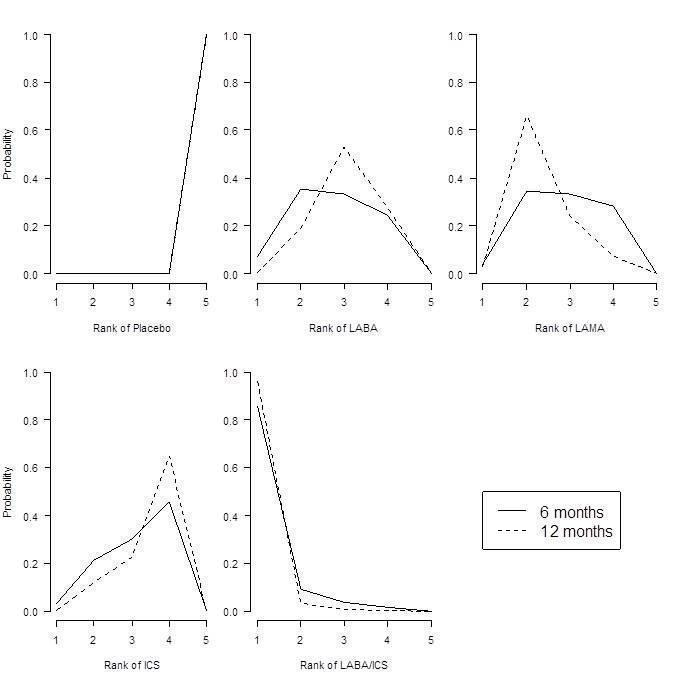

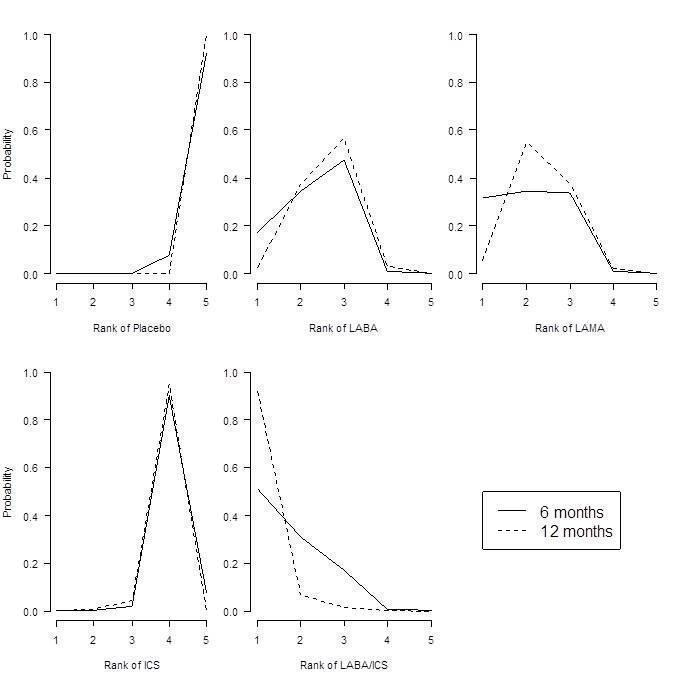

Results from the 12‐month networks for each outcome are also presented (shown graphically alongside the six‐month class results in Figure 4 and Figure 5), and sensitivity analyses for risk of bias (open‐label delivery) are presented for the six‐month class analyses.

4.

St George's Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ) change from baseline—six‐month and 12‐month class results.

5.

Trough forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) change from baseline—six‐month and 12‐month class results.

St George's Respiratory Questionnaire

Across six months and 12 months, 42 studies with 118 individual treatment nodes were included in the networks (n = 54,613).

Main analysis—six months

Eighteen treatments were compared over a total of 72 treatment arms in 25 studies (n = 27,024). Thirty‐nine pair‐wise comparisons were made, and the fixed‐effect model was preferred because statistical heterogeneity was not significant (DIC random = 214.9, fixed = 214.5).

Class effects

Table 6 shows each class effect relative to placebo (i.e. the combined treatment benefit over placebo), expressed as change from baseline. The classes are also ranked (mean and median) and are presented with estimates of the probability that each is the best class. Figure 4 displays class effects against the reference treatment (placebo), shown by the vertical dashed line on the right‐hand side of the graph.

6. SGRQ class effects versus placebo (six months)a.

| Effect vs placebo Class NWMA | Effect vs placebo Sensitivity analysis | Rank | ||||||

| Class | Median | 95% CrI | Median | 95% CrI | Mean | Median | 95% CrI | Pr (best) |

| LABA/ICS | ‐3.89 | (‐4.70 to ‐2.97) | ‐3.89 | (‐4.66 to ‐3.05) | 1.0 | 1 | (1 to 2) | 0.96 |

| LAMA | ‐2.63 | (‐3.53 to ‐1.97) | ‐2.78 | (‐3.58 to ‐2.13) | 2.4 | 2 | (1 to 4) | 0.03 |

| LABA | ‐2.29 | (‐3.18 to ‐1.53) | ‐2.09 | (‐2.93 to ‐1.36) | 3.1 | 3 | (2 to 4) | 0.01 |

| ICS | ‐2.00 | (‐3.06 to ‐0.87) | ‐1.96 | (‐2.99 to ‐0.91) | 3.5 | 4 | (2 to 4) | 0.00 |

aFor effects versus placebo, smaller values indicate larger benefits of the active treatment; all doses are given in micrograms.

Crl = credible interval.

SGRQ = St George's Respiratory Questionnaire.

ICS = inhaled corticosteroid.

LABA = long‐acting beta2‐agonist.

LABA/ICS = long‐acting beta2‐agonist/inhaled corticosteroid.

LAMA = long‐acting antimuscarinic antagonist.

NWMA = network meta‐analysis.

Pr = probability.

Combination LABA/ICS was the highest ranked treatment, with a mean improvement over placebo of 3.89 units (95% credible interval (CrI) ‐4.70 to ‐2.97). LAMAs and LABAs were ranked second and third, with mean differences of ‐2.63 (95% CrI ‐3.53 to ‐1.97) and ‐2.29 (95% CrI ‐3.18 to ‐1.53), respectively, but a large degree of overlap was noted between their credible intervals. Inhaled corticosteroids were the fourth ranked class but still showed a mean two‐unit benefit over placebo at six months (95% CrI ‐3.06 to ‐0.87). Figure 6 shows graphs of the probabilities that each class ranks in any one of the five possible positions. The median within‐class variance was 0.44 units (95% CrI 0.03 to 1.09).

6.

St George's Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ) probability ranking diagrams—six months and 12 months.

Individual treatment effects

Effects relative to placebo are presented separately for each treatment in Table 7, along with ranks and estimates with and without the class model for comparison. The credible intervals for each treatment were wide and largely overlapping (for both ranks and mean differences from placebo).

7. SGRQ individual treatment effects versus placebo (six months)a.

| Rank (from class NWMA) | Effect vs placebo Class NWMA | Effect vs placebo NWMA no class | Rank (from class NWMA) | ||||||

| Class | Treatment (number daily doses) | Median | 95% CrI | Median | 95% CrI | Mean | Median | 95% CrI | Pr (best) |

| LABA | Form 12 (2) | ‐1.84 | (‐2.60 to ‐0.94) | ‐1.20 | (‐2.10 to ‐0.30) | 14.9 | 15 | (10 to 17) | 0.00 |

| Ind 300 (1) | ‐2.38 | (‐3.63 to ‐1.44) | ‐3.10 | (‐4.86 to ‐1.36) | 11.3 | 12 | (5 to 17) | 0.00 | |

| Ind 150 (1) | ‐2.75 | (‐3.95 to ‐1.85) | ‐3.67 | (‐4.76 to ‐2.58) | 8.7 | 8 | (3 to 16) | 0.01 | |

| Salm 50 (2) | ‐2.20 | (‐2.98 to ‐1.43) | ‐2.27 | (‐3.27 to ‐1.27) | 12.9 | 13 | (7 to 17) | 0.00 | |

| LAMA | Tio 5 (1) | ‐2.50 | (‐3.16 to ‐1.86) | ‐2.42 | (‐3.20 to ‐1.63) | 10.5 | 10 | (6 to 16) | 0.00 |

| Tio 18 (1) | ‐2.53 | (‐3.12 to ‐1.97) | ‐2.66 | (‐3.33 to ‐1.99) | 10.3 | 10 | (6 to 15) | 0.00 | |

| Acl 200 (2) | ‐2.66 | (‐4.04 to ‐1.70) | ‐3.79 | (‐6.14 to ‐1.45) | 9.1 | 9 | (2 to 16) | 0.01 | |

| Acl 400 (2) | ‐2.81 | (‐4.40 to ‐1.90) | ‐4.59 | (‐6.94 to ‐2.23) | 7.9 | 7 | (1 to 15) | 0.03 | |

| Gly 50 (1) | ‐2.63 | (‐3.42 to ‐1.94) | ‐2.83 | (‐3.74 to ‐1.91) | 9.5 | 9 | (5 to 15) | 0.00 | |

| ICS | Bud 400 (2) | ‐1.76 | (‐2.82 to ‐0.55) | ‐0.97 | (‐2.32 to 0.38) | 14.9 | 16 | (7 to 17) | 0.00 |

| Flut 500 (2) | ‐1.95 | (‐3.07 to ‐0.74) | ‐1.71 | (‐3.40 to ‐0.01) | 13.9 | 15 | (6 to 17) | 0.00 | |

| Mom 400 (2) | ‐2.28 | (‐3.51 to ‐1.19) | ‐2.77 | (‐4.47 to ‐1.09) | 11.9 | 13 | (5 to 17) | 0.00 | |

| LABA/ICS | Form‐bud 12/160 (2) | ‐4.04 | (‐4.91 to ‐3.15) | ‐3.85 | (‐4.99 to ‐2.70) | 2.6 | 2 | (1 to 6) | 0.29 |

| Form‐bud 12/320 (2) | ‐3.80 | (‐4.63 to ‐2.84) | ‐3.31 | (‐4.39 to ‐2.22) | 3.9 | 4 | (1 to 9) | 0.10 | |

| Form‐mom 12/200 (2) | ‐3.85 | (‐4.82 to ‐2.66) | ‐3.45 | (‐5.17 to ‐1.74) | 3.7 | 4 | (1 to 10) | 0.15 | |

| Form‐mom 12/400 (2) | ‐3.75 | (‐4.72 to ‐2.48) | ‐3.09 | (‐4.81 to ‐1.37) | 4.3 | 4 | (1 to 11) | 0.10 | |

| Salm‐flut 50/500 (2) | ‐4.05 | (‐4.97 to ‐3.18) | ‐4.36 | (‐5.60 to ‐3.12) | 2.6 | 2 | (1 to 6) | 0.31 | |

aFor effects versus placebo, smaller values indicate larger benefits of the active treatment; all doses are given in micrograms.

Crl = credible interval.

SGRQ = St George's Respiratory Questionnaire.

ICS = inhaled corticosteroid.

LABA = long‐acting beta2‐agonist.

LABA/ICS = long‐acting beta2‐agonist/inhaled corticosteroid.

LAMA = long‐acting antimuscarinic antagonist.

NWMA = network meta‐analysis.

Pr = probability.

Individual treatment effects of particular note within a class were associated with indacaterol and aclidinium for LABA and LAMA, respectively. Effects for both doses of each of these drugs were dampened by the class model in the six‐month SGRQ network (indacaterol by 0.72 and 0.92 for 300 mcg and 150 mcg, respectively, and aclidinium by 1.13 and 1.78 for 200 mcg and 400 mcg, respectively). Treatments of note for which estimates were inflated by fitting the class model were formoterol 12 mcg (by 0.64), budesonide 400 mcg (by 0.79) and formoterol/mometasone combination 2/400 mcg (by 0.66).

Additional analyses

12 months

Nineteen treatments were compared in 24 studies, but a dose comparison of aclidinium made in Gelb 2012 was disconnected from the rest of the network. These treatments can be used in class analysis, as they “borrow” the class effect. The fixed‐effect model was preferred.

In the class analysis (Appendix 4 and Figure 4), LABA/ICS combinations remained the highest ranked at 12 months, with only a slightly smaller mean effect over placebo than at six months (‐3.60, 95% CrI ‐4.63 to ‐2.34). Compared with the six‐month analysis, LABA, LAMA and ICS showed more similar benefits over placebo at 12 months, ranging between ‐2.34 and ‐2.55, with similar credible intervals. Within‐class variance was slightly larger than in the six‐month analysis (median 0.53, 95% CrI 0.04 to 1.27).

Individual treatment effects for the 12‐month analysis are presented in Appendix 5.

Sensitivity analysis—blinding

Table 6 shows how the six‐month effects were affected by removal of data at high risk of bias for blinding (see 'Effect vs placebo sensitivity analysis'). The difference between point estimates of LAMA over LABA was larger with less overlap in the credible intervals, and within‐class variance was smaller than in the main analysis (median 0.35, 95% CrI 0.02 to 0.98). Inconsistency associated with Donohue 2010 [INHANCE] was resolved by removing the open‐label tiotropium arm, but unexplained poor fit of three further trials remained (Kornmann 2011; Rennard 2009; Tashkin 2012). As all open‐label arms removed were given tiotropium, it is possible that the expected treatment benefit over placebo in these studies was reduced by lack of blinding for these comparisons, which dampened the overall treatment effect within the LAMA class.

Trough FEV1

Across six months and 12 months, 46 studies with 120 individual treatment nodes were included in the networks (n = 47,409).

Main analysis—six months

Twenty treatments were compared over a total of 82 treatment arms in 31 studies (n = 29,271). Forty‐one pair‐wise comparisons were made. The random‐effects model was preferred (DIC = 691), as the fixed‐effect model has very poor fit (DIC = 719.1).

Class effects

Table 8 shows each class effect relative to placebo. As for SGRQ, the classes are also ranked (mean and median) and are presented with estimates of the probability that each is the best. Figure 6 displays trough FEV1 class effects (mL) compared with placebo.

8. FEV1 class effects versus placebo (six months)a.

| Effect vs placebo Class NWMA | Effect vs placebo Sensitivity analysis | Rank | ||||||

| Class | Median | 95% CrI | Median | 95% CrI | Mean | Median | 95% CrI | Pr (best) |

| LABA/ICS | 133.30 | (100.60 to 164.00) | 132.80 | (98.93 to 165.60) | 1.1 | 1 | (1 to 2) | 0.9 |

| LAMA | 103.50 | (81.78,124.90) | 103.60 | (79.01 to 126.60) | 2.4 | 2 | (1 to 3) | 0.1 |

| LABA | 99.44 | (71.98,127.80) | 99.86 | (70.41 to 130.50) | 2.6 | 3 | (1 to 4) | 0.0 |

| ICS | 65.36 | (33.06,96.91) | 65.52 | (31.23 to 97.16) | 3.9 | 4 | (3 to 4) | 0.0 |

aFor effects versus placebo, smaller values indicate larger benefits of the active treatment; all doses are given in micrograms.

Crl = credible interval.

FEV1 = forced expiratory volume in one second.

ICS = inhaled corticosteroid.

LABA = long‐acting beta2‐agonist.

LABA/ICS = long‐acting beta2‐agonist/inhaled corticosteroid.

LAMA = long‐acting antimuscarinic antagonist.

NWMA = network meta‐analysis.

Pr = probability.