Abstract

Background:

Asian Americans are one of the fastest growing races in US. The objectives of this report were to assess self-reported hypertension prevalence and treatment among Asian Americans.

Methods:

Merging 2013, 2015, and 2017 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System data, we estimated self-reported hypertension and antihypertensive medication use among non-Hispanic Asian Americans (NHA) and compared estimates between NHA and non-Hispanic whites (NHW), and by NHA subgroup (Asian Indian, Chinese, Filipino, Japanese, Korean, and Vietnamese/Other).

Results:

The prevalence of hypertension was 20.8% and 33.5%, respectively, for NHAs and NHWs (p<0.001). Among those with hypertension, the prevalence of antihypertensive medication use was 71.6% and 78.2%, respectively, for NHAs and NHWs (p<0.001). Among NHA subgroups, wide range of hypertension prevalence and medication use was found.

Discussion:

Overall NHA had a lower reported prevalence of hypertension and use of antihypertensive medication than NHW. Certain NHA subgroups had a burden comparable to high-risk disparate populations.

Keywords: hypertension, antihypertensive medication use, non-Hispanic Asian Americans, surveillance

Introduction:

In the United States (US), Asian Americans are one of the fastest growing populations. In 2010, about 5% of total US population were Asian American,[1] and the population is projected to double from 18 million in 2016 to 37 million by 2060.[2] The increase will create additional demand to address the unique health factors associated with this population.[3] A recent study showed that Asian Americans had a higher risk of death related to hypertensive heart disease and cerebrovascular disease, especially intracerebral hemorrhage, compared to non-Hispanic whites (NHW).[4] Hypertension is a major risk factor for heart disease and stroke[5] and nearly half of all US adults have hypertension defined as a systolic blood pressure ≥ 130 mm Hg or a diastolic blood pressure ≥ 80 mm Hg or taking medication for hypertension.[6,7] Highlighting the importance of hypertension in this population, a prior report found lower hypertension awareness, prevalence, treatment and control in non-Hispanic Asians (NHA) compared to other race/ethnic groups.[8]

Improving the cardiovascular health of the US population, including the prevention and management of hypertension, is a national health priority (www.healthypeople.gov). In addition, national organizations have published reports identifying the need to target the NHA population in cardiovascular disease (CVD) prevention efforts. For example, the American Heart Association published an Advisory “Call to Action” which included the need to increase, improve, understand and study risk factors contributing to CVD among Asians.[9] To extend our understanding of cardiovascular health in NHA, we recently used a nationally representative sample to estimate overall cardiovascular health and profile differences in race/ethnic groups. Estimates of cardiovascular health among NHA were low, as anticipated, yet significantly higher than estimates of NHW. However, when using a lower threshold for body mass index (BMI) (i.e., overweight, BMI ≥23 and obesity, ≥ 27.5 kg/m2) among NHA, the significant difference between NHA and NHW was negated.[10] A primary limitation of that report was the inability to assess NHA ethnic subgroups in detail. The inclusion of NHA subgroup questions in a comparable national survey would allow us to address this gap in the literature. Beginning in 2013, the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) included detailed race/ethnicity questions assessing subcategories for those who selected “Asian” as their race (Asian Indian, Chinese, Filipino, Korean, Japanese and Vietnamese). Using data from the BRFSS 2013–2017, we examined the prevalence of self-reported hypertension and antihypertensive medication use among NHAs overall, among subgroups, and compared these with estimates for NHWs.

Methods:

Data Source:

The BRFSS is a state-based representative telephone (landline and cellular) survey of non-institutionalized, civilian residents. The survey has been conducted annually since 1984 by state and territorial health departments, with assistance from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The survey collects data on health behaviors, chronic health conditions, and use of preventive services.[11] The BRFSS includes core questions asked by all states and optional module questions selected by states for inclusion. Core questions assessing high blood pressure awareness and management were included in 2013, 2015 and 2017, but not in the intervening years. The three years of data were combined in this report to support the assessment of subgroup comparisons. The median state-specific response rates were 45.9% (range=29.0–59.2%), 47.2% (33.9–61.1%) and 45.9% (36.28–64.1%) for 2013, 2015 and 2017, respectively.

Several race/ethnic questions were used to categorize the sample as NHA or NHW. Respondents self-reported their race, ethnicity, and country of origin. Based on those responses, participants were categorized as NHA or NHW, and further categorized by their country of origin. As this study is focused on NHA, country of origin was limited to the subcategories “Asian Indian”, “Chinese”, “Filipino”, “Japanese”, “Korean”, “Vietnamese” and “Other Asian”. Recent US Census data indicate that 98.6% of the total Asian American population identifies as NHA.[12] Those identifying as Hispanic Asian were excluded to simplify analysis. BRFSS data about Asians subgroups were not publicly available due to potential privacy issues from small sample sizes. A data use agreement was submitted to access the restricted data.

Hypertension was determined with the question, “Have you ever been told by a doctor, nurse, or other health professional that you have high blood pressure?”. Women who had hypertension only during pregnancy, and those who were told they had borderline high or prehypertension were not categorized as having hypertension. Among those with hypertension, current use of antihypertensive medication was assessed with question, “Are you currently taking medicine for your high blood pressure?”.

Sociodemographic characteristics included sex, age (18–64, ≥65 years), and level of education (up to high school graduate, some college or above). CVD risk factors included self-reported diabetes and obesity. The latter was calculated using self-reported weight and height (kg/m2), classifying those with the BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 as having obesity. Several prior studies have indicated that standard BMI cut-points for obesity may not be appropriate for Asian populations.[13] To address this potential limitation, additional analyses were conducted using a recommended Asian-specific BMI cut-points for overweight and obesity recommended by the World Health Organization (BMI ≥23 and ≥ 27.5 kg/m2).[14]

BRFSS was approved as exempt research by the CDC human subjects review board.

Statistical Analysis

Comparisons between NHA and NHW were assessed using t-tests. NHA subgroup (Asian Indian, Chinese, Filipino, Japanese, Korean, Vietnamese/Other) comparisons were assessed using χ2 tests. We examined the prevalence of hypertension and antihypertensive medication use among those with hypertension between NHA and NHW, as well as among NHA subgroup, by each characteristic. Using logistic regression analyses, we estimated the adjusted prevalence of hypertension and antihypertensive medication use among NHA and NHW, as well as by NHA subgroup. Using a multinomial logistic regression model, we estimated the prevalence ratio and 95% confidence intervals (CI) of hypertension and antihypertensive medication use among those with hypertension for NHA, using NHW as the referent. Among NHA subgroups, we estimated the prevalence ratios for each subgroup, using Japanese as the referent. Unadjusted and adjusted (by age, sex, level of education, diabetes and BMI) models were used. In addition, further adjustment was conducted for survey year (2013, 2015 and 2017).

To account for BRFSS data which are weighted to each state population estimate using a raking method,[15] SAS-callable SUDAAN (version 11.0.3, Research Triangle Institute, NC, USA) was used for the complex sampling design. All statistical tests were two-tailed, and we defined significance as a P-value of less than 0.05.

Results:

The total sample consisted of 993,187 NHW and 27,069 NHA. NHA subgroups included 5,301 Asian Indians, 4,418 Chinese, 4,413 Filipinos, 5,021 Japanese, 1,309 Korean, 884 Vietnamese, and 2,441 other Asians. Due to a relatively small sample of Vietnamese, they were combined with the “other Asian” group (n=3,325). A total of 3,282 (12%) NHA were missing information on country of origin and were not included in the NHA subgroup analyses.

A higher percentage of NHA were younger and had at least some college education compared to their NHW counterparts (Table 1). However, they were less likely to have diabetes and obesity compared to NHW, using either the standard BMI criteria or the Asian-specific BMI criteria. Among the NHA subgroups, the Japanese subgroup was notably older (34.3%, ≥65 years of age), followed by the Filipino subgroup (16.1%, ≥65 years of age). Asian Indians had the highest percentage of men. Filipino and Vietnamese/Other had a slightly lower percentage with more than high school education than other groups. Japanese, Filipino and Asian Indian had higher percentages with diabetes than other groups. Obesity rates were higher among Filipinos, Asian Indian and Japanese and lower among Chinese and Korean, regardless of criteria used (Table 1).

Table 1.

Population characteristics, non-Hispanic whites and non-Hispanic Asians overall and by subgroup, BRFSS 2013, 2015 and 2017

| Non-Hispanic white (NHW) | Non-Hispanic Asian (NHA) | χ2 p-value | Asian Indian (AI) | Chinese | Filipino | Japanese | Korean | Vietnamese & Other | p-value | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | (95%CI) | % | (95%CI) | % | (95%CI) | % | (95%CI) | % | (95%CI) | % | (95%CI) | % | (95%CI) | % | (95%CI) | |||

| Number | 993187 | 27069 | 5301 | 4418 | 4413 | 5021 | 1309 | 3325 | ||||||||||

| Age (years) | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||||||||||||

| 18–64 | 76.1 | 75.9–76.2 | 89.5 | 88.7–90.3 | 92.6 | 91.2–93.8 | 91.2 | 89.1–92.9 | 83.9 | 81.0–86.4 | 65.8 | 60.9–70.3 | 93.3 | 90.6–95.3 | 94.1 | 92.3–95.4 | ||

| ≥65 | 23.9 | 23.8–24.1 | 10.5 | 9.7–11.3 | 7.4 | 6.2–8.8 | 8.8 | 7.1–10.9 | 16.1 | 13.6–19.0 | 34.3 | 29.7–39.1 | 6.7 | 4.7–9.4 | 5.9 | 4.6–7.7 | ||

| Sex | 0.417 | <0.001 | ||||||||||||||||

| Men | 49.9 | 49.7–50.1 | 50.4 | 49.2–51.7 | 57.2 | 54.9–59.5 | 47.7 | 44.9–50.5 | 42.4 | 38.9–45.8 | 42.7 | 38.4–47.2 | 46.4 | 41.4–51.5 | 51.5 | 48.3–54.7 | ||

| Women | 50.1 | 49.9–50.3 | 49.6 | 48.3–50.8 | 42.8 | 40.5–45.1 | 52.3 | 49.5–55.1 | 57.7 | 54.2–61.1 | 57.3 | 52.8–61.6 | 53.6 | 48.5–58.7 | 48.5 | 45.3–51.7 | ||

| Education | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||||||||||||

| ≤ HS | 37.4 | 37.2–37.6 | 21.5 | 20.4–22.6 | 15.8 | 14.0–17.8 | 17.3 | 15.1–19.8 | 27.5 | 24.3–31.0 | 20.5 | 17.2–24.3 | 17.2 | 13.8–21.1 | 29.7 | 26.8–32.8 | ||

| > HS | 62.6 | 62.5–62.8 | 78.6 | 77.5–79.6 | 84.2 | 82.2–86.0 | 82.7 | 80.2–84.9 | 72.5 | 69.0–75.7 | 79.5 | 75.7–82.8 | 82.9 | 78.9–86.2 | 70.3 | 67.2–73.2 | ||

| Obesity1 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||||||||||||

| Yes | 28.0 | 27.8–28.1 | 10.6 | 9.8–11.3 | 10.5 | 9.1–12.1 | 7.1 | 5.6–8.9 | 15.5 | 13.0–18.4 | 11.7 | 9.5–14.3 | 6.9 | 5.1–9.4 | 12.2 | 10.3–14.3 | ||

| No | 72.0 | 71.9–72.2 | 89.5 | 88.7–90.2 | 89.5 | 87.9–90.9 | 93.0 | 91.1–94.4 | 84.5 | 81.6–87.0 | 88.3 | 85.7–90.5 | 93.1 | 90.6–95.0 | 87.8 | 85.7–89.7 | ||

| Obesity2 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||||||||||||

| Yes | 28.0 | 27.8–28.1 | 19.7 | 18.7–20.7 | 21.3 | 19.5–23.2 | 12.6 | 10.7–14.8 | 26.6 | 23.6–29.8 | 22.8 | 19.3–26.9 | 15.4 | 12.4–18.9 | 20.6 | 18.1–23.3 | ||

| No | 72.0 | 71.9–72.2 | 80.3 | 79.3–81.3 | 78.7 | 76.8–80.5 | 87.4 | 85.2–89.3 | 73.5 | 70.2–76.4 | 77.2 | 73.1–80.7 | 84.6 | 81.1–87.6 | 79.4 | 76.7–81.9 | ||

| Diabetes | 0.002 | <0.001 | ||||||||||||||||

| Yes | 9.8 | 9.7–9.9 | 8.6 | 7.8–9.3 | 10.0 | 8.6–11.5 | 5. | 3.8–7.0 | 13.1 | 10.8–15.9 | 13.9 | 10.4–18.2 | 3.8 | 2.5–5.7 | 6.7 | 5.1–8.8 | ||

| No | 90.3 | 90.1–90.4 | 91.5 | 90.7–92.2 | 90.0 | 88.5–91.4 | 94.8 | 93.0–96.2 | 86.9 | 84.1–89.2 | 86.1 | 81.8–89.6 | 96.2 | 94.3–97.5 | 93.3 | 91.2–94.9 | ||

HS High school

Obesity 1: standard criteria (≥30 kg/m2) for both non-Hispanic white and non-Hispanic Asian

Obesity 2: standard criteria (≥30 kg/m2) for non-Hispanic white and Asian specific cut point (≥27.5 kg/m2) for non-Hispanic Asian

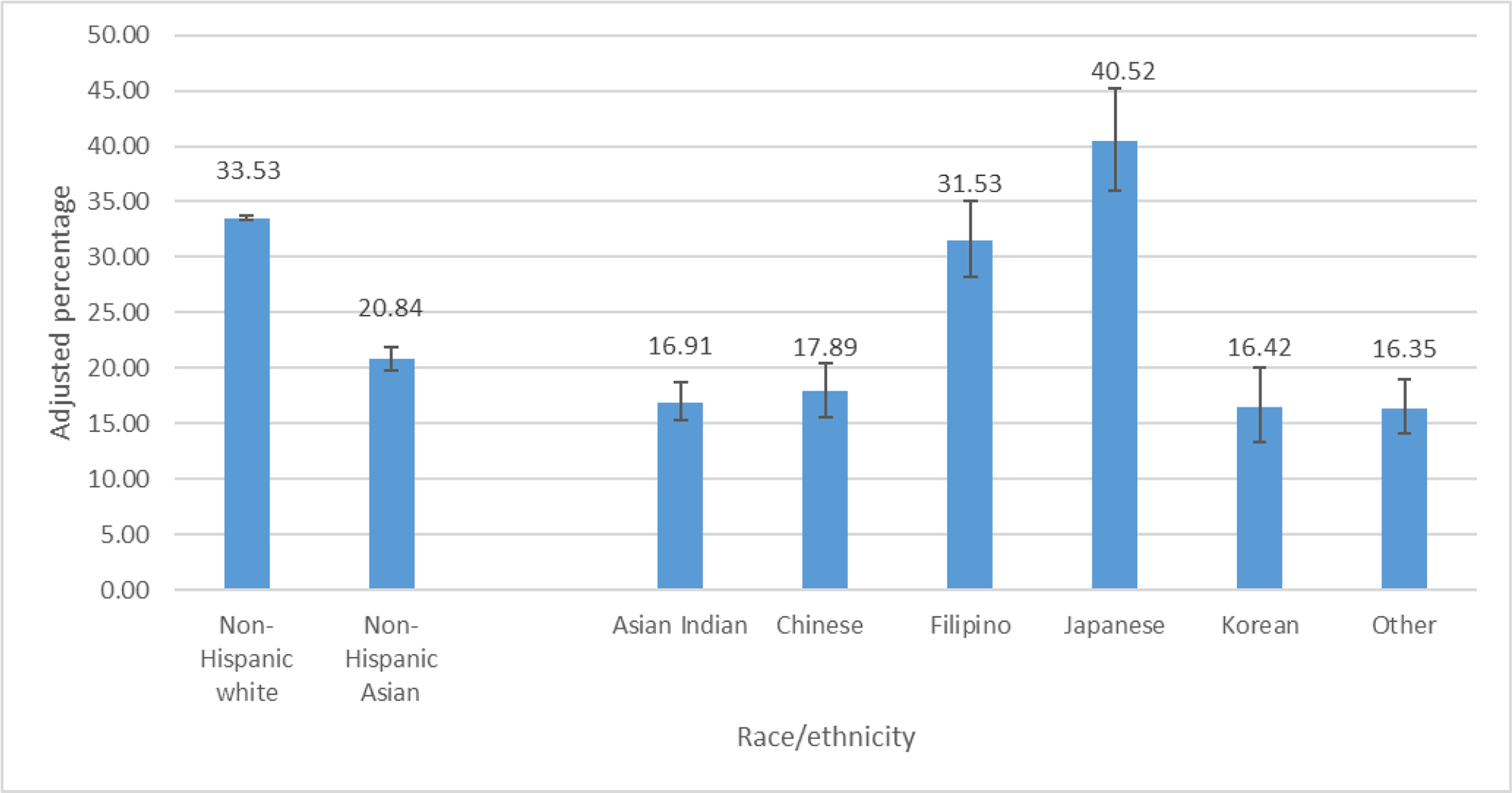

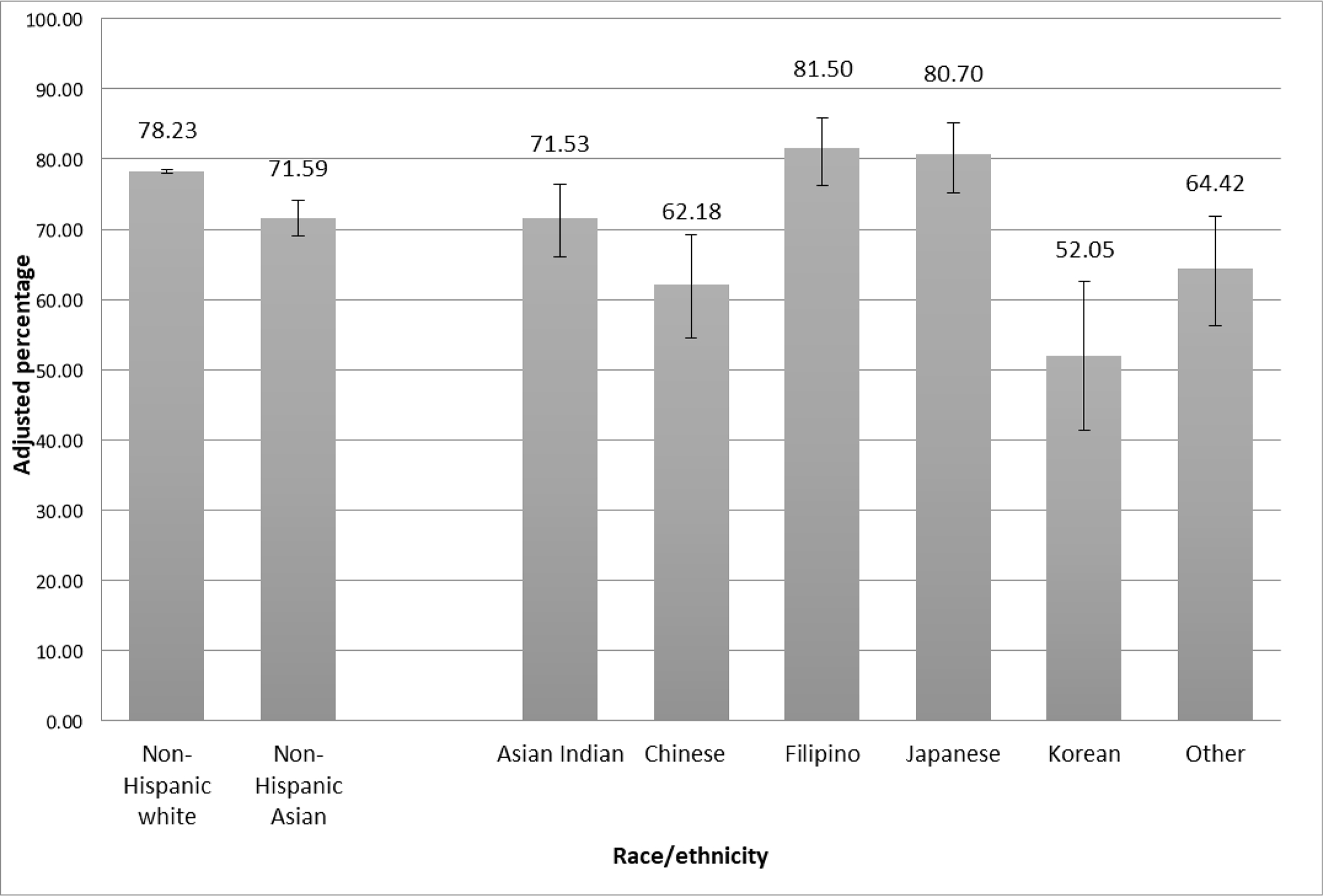

The adjusted prevalence of self-reported hypertension was significantly higher among NHW than NHA (Figure 1). Among NHA subgroups, Japanese had the highest adjusted hypertension prevalence, followed by Filipino. Of note, the adjusted prevalence of the Japanese subgroup was more than twice as high as Asian Indian, Chinese, Korean and Vietnamese/Other. Among those with hypertension, the adjusted prevalence of antihypertensive medication use was significantly higher among NHW than NHA (Figure 2). Among NHA subgroups, antihypertensive medication use was significantly higher among Japanese and Filipinos, and Chinese and Korean had a significantly lower prevalence.

Figure 1.

Adjusted*prevalence of hypertension among non-Hispanic white and non-Hispanic Asian overall and by subgroup, BRFSS 2013, 2015 and 2017

*Adjusted by age, sex, level of education

Figure 2.

Adjusted*prevalence of antihypertensive medication use among those with hypertension, non-Hispanic white and non-Hispanic Asian overall and by subgroup, BRFSS 2013, 2015 and 2017

*Adjusted by age, sex, level of education

Using NHW as the referent group, the prevalence ratio for hypertension among NHA ranged from 0.62–0.85, depending on the adjustment used (Table 2). Among NHA subgroups, using Japanese as the referent, Asian Indian, Chinese, Korean, and Vietnamese/Other had a consistently lower prevalence for hypertension. No significant difference between Filipinos and Japanese was noted after adjustment (Table 2). Among those with hypertension, using NHW as the referent, the prevalence ratio of antihypertensive medication use among NHAs was 0.97 (0.96–0.98), after adjusting for age, sex, level of education, diabetes and obesity, which was defined as ≥30 kg/m2 for NHWs and ≥27.5 kg/m2 for NHAs (Table 3). Among NHA subgroups, using Japanese as the referent, antihypertensive medication use among those with hypertension was consistently lower for Chinese and Korean (Table 3). No significant difference was noted for Asian Indian or Vietnamese/Other in unadjusted or adjusted models (Table 3). Additional adjustment with the year of survey did not modify the results.

Table 2.

Prevalence ratio of self-reported hypertension of non-Hispanic whites compared to non-Hispanic Asians, overall and by subgroup

| Crude | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Non-Hispanic white | referent | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 0.62 (0.59–0.65) | 0.77 (0.74–0.81) | 0.85 (0.82–0.89) | 0.80 (0.77–0.83) | 0.80 (0.77–0.83) | |||

| p-value | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |||

| Non-Hispanic Asian | Japanese | referent | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Asian Indian | 0.42 (0.36–0.49) | 0.56 (0.47–0.67) | 0.55 (0.46–0.65) | 0.54 (0.45–0.64) | 0.54 (0.45–0.64) | |||

| Chinese | 0.44 (0.37–0.53) | 0.60 (0.49–0.73) | 0.64 (0.53–0.77) | 0.68 (0.57–0.82) | 0.69 (0.58–0.82) | |||

| Filipino | 0.78 (0.67–0.91) | 0.94 (0.79–1.13) | 0.89 (0.74–1.06) | 0.86 (0.73–1.03) | 0.87 (0.73–1.03) | |||

| Korean | 0.41 (0.32–0.51) | 0.58 (0.46–0.73) | 0.64 (0.51–0.80) | 0.65 (0.53–0.81) | 0.66 (0.53–0.81) | |||

| Vietnamese & Other | 0.40 (0.33–0.49) | 0.56 (0.46–0.68) | 0.57 (0.47–0.69) | 0.58 (0.48–0.70) | 0.58 (0.48–0.71) | |||

| p-value | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |||

Model 1: adjusted by age, sex, education

Model 2: adjusted by variables from model 1 + diabetes, standard BMI cut point (≥25 kg/m2, ≥30 kg/m2) for both non-Hispanic white and non-Hispanic Asian

Model 3: adjusted by variables from model 1 + diabetes, standard BMI for non-Hispanic white and Asian specific BMI cut points (23 kg/m2and 27.5 kg/m2) for non-Hispanic Asian

Model 4: adjusted by variables from model 3 plus survey year

Table 3.

Prevalence ratio of antihypertensive medication use among those with hypertension comparing non-Hispanic White to non-Hispanic Asian overall and by subgroup

| Crude | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Non-Hispanic White | referent | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 0.92 (0.88–0.95) | 0.97 (0.94–1.00) | 0.98 (0.95–1.00) | 0.96 (0.94–0.99) | 0.96 (0.94–0.99) | ||

| p-value | <0.0001 | 0.0163 | 0.0943 | 0.0060 | 0.0062 | ||

| Non-Hispanic Asian | Japanese | referent | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Asian Indian | 0.89 (0.81–0.97) | 1.01 (0.91–1.12) | 0.98 (0.89–1.09) | 0.98 (0.89–1.08) | 0.98 (0.90–1.08) | ||

| Chinese | 0.77 (0.67–0.88) | 0.86 (0.75–0.99) | 0.86 (0.76–0.97) | 0.86 (0.76–0.97) | 0.86 (0.77–0.97) | ||

| Filipino | 1.01 (0.93–1.10) | 1.09 (0.98–1.22) | 1.07 (0.95–1.19) | 1.06 (0.95–1.18) | 1.06 (0.95–1.18) | ||

| Korean | 0.65 (0.52–0.80) | 0.77 (0.65–0.92) | 0.79 (0.68–0.93) | 0.79 (0.68–0.92) | 0.79 (0.68–0.91) | ||

| Vietnamese & Other | 0.80 (0.70–0.91) | 0.94 (0.83–1.06) | 0.93 (0.82–1.04) | 0.93 (0.82–1.05) | 0.93 (0.82–1.04) | ||

| p-value | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 |

Model 1: adjusted by age, sex, education

Model 2: adjusted by variables from model 1 + diabetes, standard BMI cut point (≥25 kg/m2, ≥30 kg/m2) for both non-Hispanic white and non-Hispanic Asian

Model 3: adjusted by variables from model 1 + diabetes, standard BMI for non-Hispanic white and Asian specific BMI cut points (≥23 kg/m2 and ≥27.5 kg/m2) for non-Hispanic Asian

Model 4: adjusted by variables from model 3 plus survey year

Detailed percentages of self-reported hypertension and using antihypertensive medications between NHW and NHA, as well as among NHA subgroups by participant characteristic are presented in supplemental Tables 1 and 2.

Discussion

In this study, NHA had an overall lower prevalence of self-reported hypertension and antihypertension medication use than NHW. However, significant heterogeneity was found among NHA subgroups. Japanese adults had a high prevalence of self-reported hypertension, followed by Filipino adults. Estimates of hypertension among Japanese adults were equal to other high-priority populations.[6] Other subgroups, including Asian Indian, Korean, Chinese and Vietnamese/Other, had notably lower estimates of self-reported hypertension. Antihypertension medication use among NHW with hypertension was significantly higher than NHA, with both groups estimates exceeding 70%. Antihypertensive medication use among NHA subgroup varied, with estimates exceeding 80% among some subgroups (Filipino and Japanese), while about half of Koreans reported use.

The difference in hypertension prevalence between NHW and NHA has been previously reported. A prior report using data from the 2015–2016 National Health and Nutritional Examination Survey (NHANES) found the age-adjusted prevalence of hypertension among adults aged 18 and over was 27.8% and 25.6% among NHW and NHA, respectively.[16] However, the age-adjusted prevalence of hypertension control (i.e., blood pressure <140/90 mmHg) among adults with hypertension was 50.8% and 37.4% for NHW and NHA, respectively,[16] While estimates of hypertension control cannot be produced using BRFSS data, the age-adjusted prevalences of self-reported hypertension among NHW and NHA were similar in this report when compared to prior NHANES analyses.[16] In a previous study, using BRFSS data from 2011, 2013 and 2015, we found that age-standardized self-reported hypertension was consistently higher among NHW than those of NHA in each survey year.[17] However, unlike in this study, the previous study noted no statistically significant differences in antihypertensive medication use between NHW and NHA in any year.[17]

National data on the burden of hypertension among NHA subgroups in the US are limited. Studies conducted with subnational data have found differences in cardiovascular disease risk factors among NHA subgroups. For example, a study in Los Angeles County found that Filipinos had a higher burden of hypertension and pre-diabetes than Chinese adults.[18,19] Similar findings have been recorded in an ambulatory care setting in northern California, where the age-adjusted prevalence of hypertension was lowest in Chinese women and highest in Filipino men.[20] Treatment estimates have also varied among NHA subgroups. For example, prior studies found only 41% of Chinese Americans[21] and 40% Korean Americans with hypertension reported taking antihypertensive medications.[22] NHANES data from 2011–2012 showed that among hypertension, NHA had a lower prevalence of hypertension awareness (72.8% vs 82.7%),treatment (65.2% vs 76.7%), and control (46.0% vs 53.9%) than NHW.[23] Furthermore, NHANES data from 2015–2016 also showed that NHA had lower prevalence of hypertension (25.0% vs 27.8%) and controlled hypertension (37.4% vs 50.8%) than NHW.[16]

Differences in mortality overall, and types of CVD mortality by NHA subgroup, have been reported.[24] While the overall mortality rate was higher among NHW compared to NHA, mortality related to ischemic heart disease has been found to be higher among Asian Indian and Filipinos. Furthermore, compared to NHW, hypertension-related mortality rates (including hypertensive heart disease and stroke, especially hemorrhagic stroke) have been found to be higher among NHA overall, as well as among NHA subgroups.[24] Differences in subtype of CVD mortality may provide insight into targeted interventions among NHA subgroups. Prioritizing efforts to reduce hypertension prevalence and improve hypertension control among NHA may have significant intermediate and long-term impacts. Health care systems may want to consider an initial step of assuring adequate utilization of antihypertensive medications among NHA requiring it for control.

Our results showed that self-reported hypertension was heterogeneous among NHA subgroups, with the highest prevalence in the Japanese subgroup and the lowest in the Asian Indian, Korean, Chinese and Vietnamese/Other subgroups. No differences were noted between Filipino and Japanese subgroups. While the higher prevalence of hypertension among Filipino Americans has been previously reported,[18] limited data on the high prevalence among the Japanese subgroup found in this study has been reported. The Japanese subgroup notably had a higher proportion of older adults, likely contributing to the higher proportion of those with hypertension. In addition, according to the US Census Bureau, among Asian subgroups, Japanese have the highest proportion being US-born.[25] This suggests that Japanese have resided in the US longer than over NHA subgroups and may have fewer barriers to health care, potentially allowing for increased awareness of hypertension in this population.[26]

Differences in antihypertensive medication use observed in this study among NHA subgroups are likely attributed to multiple factors, including access to health care, awareness, and cultural and language barriers.[27–30] Prior public health activities among communities with large immigrant populations have employed the use of interpreter services, language-specific public health education, and community health fairs in the areas with prominent immigrant populations to target at-risk groups.[31,32] The relatively low prevalence of antihypertensive medication use among several NHA subgroups (e.g., Chinese, Korean and Vietnamese/Other) indicates that enhanced primary care for hypertension in certain subgroups within Asian communities may be needed.

Because obesity is an important risk factor for hypertension and cardiovascular disease,[33] and prior studies have shown Asian populations to be at increased risk for cardiovascular disease, hypertension and type 2 diabetes at lower BMI thresholds than the standard cut-off point used for overweight (≥25 kg/m2) and obesity (≥30 kg/m2),[14] we applied both a standard BMI cut-point and WHO recommended Asian-specific BMI cut-point (23.5 kg/m2 and 27 kg/m2).[14,34] Regardless of the BMI cut-point applied, we found that NHW had a significantly higher prevalence of obesity than NHA. Among NHA subgroups, Filipinos had a higher burden of obesity than any other NHA subgroup. The different BMI cut points for obesity did not change the observed disparities in either self-reported hypertension or antihypertensive medication use between NHW and NHA, as well as among the NHA subgroups.

Several limitations were noted in this study. First, the BRFSS data are self-reported and subject to social desirability and recall bias. The BRFSS question assessed awareness of high blood pressure, which would require prior interaction with the health care system. While awareness of hypertension among US adults is generally high (83.3%),[35] awareness among NHA subgroups may be lower due to health care access barriers.[26] With self-reported hypertension, we don’t know if those reporting hypertension in 2017 were using the new definition.[7]7 Second, multiple years of BRFSS data were pooled to increase sample sizes. However, sample sizes were still limited for a few NHA subgroups. Third, the BRFSS data within each state was not weighed to be representative of the NHA subcategories. Also, there are some states that do not have enough NHA to be weighted without being merged with other race/ethnicities. Therefore, the BRFSS survey weights may not necessarily reflect the NHA population sizes within states, and results may differ slightly if more precise population-specific survey weights were used.

General comparisons among NHW and NHA mask disparities in the burden of self-reported hypertension and antihypertension medication use among specific NHA subgroups. Because Asian Americans are one of the fastest growing minority population in the US, culturally appropriate and targeted risk factor mitigation and intervention strategies could prove effective in reducing disparities. This could include utilizing available evidence-based interventions to improve hypertension awareness and management, along with additional research assessing the most appropriate interventions among NHA.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

CDC Disclaimer: The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

References

- 1.Hoeffel EM, Rastogi S, Kim MO, Shahid H. The Asian population: 2010. Census 2010 Brief. Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vespa J, Medina L, Armstrong DM. Demographic turning points for the United States: population projections for 2020 to 2060. P25–1144. U.S. Census Bureau. Washington, DC, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bloom B, Black LI. Health of non-Hispanic Asian adults: United States, 2010–2014.NCHS data brief, no 247. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jose PO, Frank AT, Kapphahn KI, Goldstein BA, Eggleston K, Hastings KG, Cullen MR, Palaniappan LP. Cardiovascular disease mortality in Asian Americans. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64:2486–2494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, Izzo JL Jr, Jones DW, Materson BJ, Oparil S, Wright JT Jr, Roccella EJ; Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; National High Blood Pressure Education Program Coordinating Committee. Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Hypertension. 2003; 42:1206–1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Virani SS, Alonso A, Benjamin EJ, Bittencourt MS, Callaway CW, Carson AP, Chamberlain AM, Chang AR, Cheng S, Delling FN, Djousse L, Elkind MSV, Ferguson JF, Fornage M, Khan SS, Kissela BM, Knutson KL, Kwan TW, Lackland DT, Lewis TT, Lichtman JH, Longenecker CT, Loop MS, Lutsey PL, Martin SS, Matsushita K, Moran AE, Mussolino ME, Perak AM, Rosamond WD, Roth GA, Sampson UKA, Satou GM, Schroeder EB, Shah SH, Shay CM, Spartano NL, Stokes A, Tirschwell DL, VanWagner LB, Tsao CW, American Heart Association Council on Epidemiology and Prevention Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2020 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2020;141(9):e139–e596. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.CDC. Estimated Hypertension Prevalence, Treatment, and Control Among U.S. Adults. https://millionhearts.hhs.gov/data-reports/hypertension-prevalence.html

- 8.Nwankwo T, Yoon SS, Burt V, Gu Q. Hypertension among adults in the United States: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2011–2012. NCHS data brief, no 133. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Palaniappan LP, Araneta MRG, Assimes L, et al. Call to Action: Cardiovascular Disease in Asian Americans A Science Advisory From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2010;122(12):1242–1252. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3181f22af4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fang J, Zhang Z, Ayala C, Thompson-Paul AM, Loustalot F. Cardiovascular Health Among Non-Hispanic Asian Americans: NHANES, 2011–2016. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8(13):e011324. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.118.011324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/.

- 12.Humes KR, Jones NA, Ramirez RR. Overview of Race and Hispanic Origin: 2010. https://www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/briefs/c2010br-02.pdf.

- 13.Jih J, Mukherjea A, Vittinghoff E, et al. Using appropriate body mass index cut points for overweight and obesity among Asian Americans. Prev Med. 2014;65:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.04.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.WHO Expert Consultation. Appropriate body-mass index for Asian populations and its implications for policy and intervention strategies. Lancet. 2004. Jan 10;363(9403):157–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.CDC. The BRFSS Data User Guide. https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/data_documentation/pdf/UserguideJune2013.pdf.

- 16.Fryar CD, Ostchega Y, Hales CM, Zhang G, Kruszon-Moran D. Hypertension prevalence and control among adults: United States, 2015–2016. NCHS data brief, no 289. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fang J, Gillespie C, Ayala C, Loustalot F. Prevalence of Self-Reported Hypertension and Antihypertensive Medication Use Among Adults Aged ≥18 Years — United States, 2011–2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2018;67:219–224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zheng G, Family L, Hsu S, Rivera J, Mondy C, Cloud J, Frye D, Smith LV, Kuo T. Prediabetes, diabetes, and other CVD-related conditions among Asian populations in Los Angeles County, 2014. Ethn Health. 2019;24:779–789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Du Y, Shih M, Lightstone AS, Baldwin S. Hypertension among Asians in Los Angeles County: Findings from a multiyear survey. Prev Med Rep. 2017;6:302–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhao B, Jose PO, Pu J, Chung S, Ancheta IB, Fortmann SP, Palaniappan LP. Racial/ethnic differences in hypertension prevalence, treatment, and control for outpatients in northern California 2010–2012. Am J Hypertens. 2015;28:631–639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lau DS, Lee G, Wong CC, Fung GL, Cooper BA, Mason DT. Characterization of systemic hypertension in the San Francisco Chinese community. Am J Cardiol. 2005;96:570–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim MT, Kim KB, Juon HS, Hill MN. Prevalence and factors associated with high blood pressure in Korean Americans. Ethn Dis.2000;10(3):364–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nwankwo T, Yoon SS, Burt V, Gu Q. Hypertension among adults in the United States: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2011–2012. NCHS Data Brief. 2013. Oct;(133):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jose PO, Frank AT, Kapphahn KI, Goldstein BA, Eggleston K, Hastings KG, Cullen MR, Palaniappan LP. Cardiovascular disease mortality in Asian Americans. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64:2486–2494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pew Research Center. The Rise of Asian Americans. https://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2012/06/19/the-rise-of-asian-americans/#native-born-and-foreign-born.

- 26.Clough J, Lee S, Chae DH. Barriers to Health Care among Asian Immigrants in the United States: A Traditional Review. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2013;24:384–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fang J, Yang Q, Ayala C, Loustalot F. Disparities in access to care among US adults with self-reported hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 2014;27:1377–1386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kjellgren KI, Ahlner J, Säljö R. Taking antihypertensive medication--controlling or co-operating with patients? Int J Cardiol. 1995;47:257–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee JE, Han HR, Song H, Kim J, Kim KB, Ryu JP, Kim MT. Correlates of self-care behaviors for managing hypertension among Korean Americans: a questionnaire survey. Int J Nurs Stud. 2010;47:411–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tran H, Do V, Baccaglini L. Health care access, utilization, and management in adult Chinese, Koreans, and Vietnamese with cardiovascular disease and hypertension. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities.2016;3:340–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ferdinand KC. Hypertension in minority populations. J Clin Hypertens. 2006;8:365–368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Duong DA, Bohannon AS, Ross MC. A descriptive study of hypertension in Vietnamese Americans. J Community Health Nurs. 2001;18:1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jensen MD, Ryan DH, Apovian CM, Ard JD, Comuzzie AG, Donato KA, Hu FB, Hubbard VS, Jakicic JM, Kushner RF, Loria CM, Millen BE, Nonas CA, Pi-Sunyer FX, Stevens J, Stevens VJ, Wadden TA, Wolfe BM, Yanovski SZ, Jordan HS, Kendall KA, Lux LJ, Mentor-Marcel R, Morgan LC, Trisolini MG, Wnek J, Anderson JL, Halperin JL, Albert NM, Bozkurt B, Brindis RG, Curtis LH, DeMets D, Hochman JS, Kovacs RJ, Ohman EM, Pressler SJ, Sellke FW, Shen WK, Smith SC Jr, Tomaselli GF. 2013 AHA/ACC/TOS guideline for the management of overweight and obesity in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and The Obesity Society. Circulation. 2014;129:S102–S138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yang JJ, Shiwaku K, Nabika T, Masuda J, Kobayashi S. High frequency of cardiovascular risk factors in overweight adult Japanese subjects. Arch Med Res 2007;38:337–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yoon SS, Gu Q, Nwankwo T, Wright JD, Hong Y, Burt V. Trends in blood pressure among adults with hypertension: United States, 2003 to 2012. Hypertension. 2015;65:54–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.