Abstract

Background:

Intimate partner violence (IPV) has negative health impacts for pregnant people and their infants. Although inpatient postpartum units offer an opportunity to provide support and resources for IPV survivors and their families, to our knowledge, such interventions exist. The goal of this study is to explore (1) how IPV is currently discussed with postpartum people in the postpartum unit; (2) what content should be included and how an IPV intervention should be delivered; (3) how best to support survivors who disclose IPV; and (4) implementation barriers and facilitators.

Materials and Methods:

We used individual, semistructured interviews with postpartum people and health care providers (HCPs). Interview transcripts were coded and analyzed using an inductive-deductive thematic analysis.

Results:

While HCPs reported using a variety of practices to support survivors, postpartum people reported that they did not recall receiving resources or education related to IPV while in the inpatient postpartum unit. While HCPs identified a need for screening and disclosure-driven resource provision, postpartum people identified a need for universal IPV resource provision in the postpartum unit to postpartum people and their partners. Participants identified several barriers (i.e., staff capacity, education already provided in the postpartum unit, and COVID-19 pandemic) and facilitators (i.e., continuity of care, various HCPs) to supporting survivors in the postpartum unit.

Conclusion:

The inpatient postpartum unit is a promising setting to implement an intervention to support IPV survivors and their infants. Future research and intervention development should focus on facilitating universal education and promoting resource provision to IPV survivors.

Keywords: intimate partner violence, postpartum, prevention, domestic violence

Introduction

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is a pervasive public health epidemic for pregnant and postpartum people.1,2 IPV is fundamentally rooted in power and control, with partners using an array of controlling and coercive behaviors and tactics to manipulate, harass, or control an intimate partner.3,4 Examples of IPV include psychological, physical, financial, sexual, or immigration-related abuse, sexual coercion, stalking, among others.3,5 The prevalence of IPV for pregnant and postpartum people is high, and varies depending on the group and type of IPV assessed. A systematic review conducted in the United States estimated that 8% of pregnant people experience physical or sexual IPV, with prevalence notably higher among cross-sectional samples of postpartum people who live in rural areas (20%) and use substances (19%).6–8

In addition, using data from the violent death reporting system, prior research found that nearly half of suicides and homicides of pregnant people involve IPV.9 Pediatric, family medicine, and women's health organizations describe the importance of supporting IPV survivors through education and resource provision during the perinatal period.3,10 One powerful framework for supporting IPV survivors is healing-centered engagement, which is a strengths-based approach where health care providers (HCPs) create safe and nonjudgmental spaces for IPV survivors.

Healing-centered engagement recognizes that IPV survivors are experts in their own experiences, and encourages HCPs to work with survivors on solutions that best reflect their own needs. The American Academy of Pediatrics updated IPV policy statement recommends use of a healing-centered approach in health care settings.3,11

Although the perinatal period may make people more vulnerable to IPV, it also offers a unique opportunity to support survivors.12 People are more likely to attend prenatal visits compared with yearly examinations, and prior research has identified perinatal visits as an opportunity to address IPV.13–16 The majority of research to date has focused on IPV screening in outpatient settings.15–18 However, these studies also identified barriers to addressing IPV in the outpatient setting, including lack of time, provider training, and provider knowledge of available resources.19

Fewer studies have focused on utilizing the immediate postpartum period as a time to assess for IPV, provide resources, and support survivors. Postpartum people spend 2–4 days in the postpartum unit, where they initiate breastfeeding, begin bonding with their infant, and have access to HCPs. While postpartum people are in the postpartum unit, they may receive education on a variety of topics, including safe sleep practices and postpartum depression.20,21 The postpartum unit may also be a safe place for survivors to talk about IPV and get needed support. It may also be easier to implement IPV-focused education and connection to resources compared with outpatient visits that are limited by time. However, to our knowledge, no IPV interventions have been developed within the postpartum unit. Further, there may be unique implementation barriers and facilitators in the postpartum unit as compared with other settings.

The goal of this study is to examine the perspectives of postpartum people and HCPs (i.e., postpartum nurses, physicians, lactation consultants, and social workers) in the United States regarding how to address IPV and support survivors in the postpartum unit. Our specific aims examine (1) how IPV is currently discussed in the postpartum unit; (2) what content should be included and how the intervention should be delivered; (3) how best to support survivors who disclose IPV; and (4) implementation barriers and facilitators.

Materials and Methods

We conducted individual, semistructured interviews with HCPs (physicians, nurse practitioners, registered nurses, social workers) and postpartum people who recently gave birth to explore their perspectives on how best to address IPV in the postpartum unit. The study took place at a large, academic hospital in a midsize city in the Northeast. The University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board approved the study. The virtual interviews took place from November 2021 to August 2022.

Materials

The study team members developed interview questions based on study aims. Interview questions addressed the following: (1) how IPV is currently discussed with postpartum people in the postpartum unit; (2) what content should be included and how education around IPV should be delivered; (3) how best to support postpartum people who disclose IPV; and (4) implementation barriers and facilitators. Separate interview guides were developed for HCPs and postpartum people.

Participants and recruitment

Eligibility criteria for postpartum people included the following: (1) age ≥18; (2) delivered at the participating hospital 0–4 months before the interview; and (3) speaks and understands English. We choose 0–4 months, so that postpartum people could remember and reflect on their birthing experience, but wanted to allow enough time so participants would not have to complete the interview immediately after giving birth. Eligibility criteria for HCPs included (1) age ≥18, (2) HCP at the participating hospital; and (3) speaks and understands English. As we were interested in hearing how IPV should be discussed in the postpartum setting more broadly, experiencing IPV was not part of the inclusion criteria.

Study team members (Erin Mickievicz and M.R.) recruited postpartum people from three locations: (1) at a large pediatric academic clinic during 0- to 4-month well-child visits; (2) immediately postpartum in the postpartum unit; and (3) through Pitt + Me, an online recruitment portal. Using convenience sampling, we recruited HCPs through email, discussing the study at team meetings, and word of mouth. Interested participants were contacted by the study team to provide verbal consent and schedule an interview.

Data analysis

Interviews were conducted via Zoom and lasted 45–60 minutes. Interviews were audio recorded and transcribed. Deidentified transcripts were coded and managed using Dedoose qualitative software. We chose a qualitative descriptive approach to perform thematic analysis.22,23 We created a preliminary codebook using general topics addressed by our interview guide. Two coders independently coded each transcript using this codebook and adding new codes in an inductive manner. They then met to review their coding and refine the codebook in an iterative fashion.

Once no new codes were added, the final codebook was then reapplied to all transcripts. Transcripts were coded independently, and coders met twice to discuss emerging codes and resolve discrepancies. The full team met twice throughout the data analysis process to consolidate codes into emerging themes and make iterative changes to the interview guide based on inductive guides (e.g., adding a question about how to include partners in IPV education). We continued with interviews until thematic saturation was reached, when we heard no new codes or themes, for both participant groups.24

Results

Thirty participants completed interviews including 14 HCPs and 16 postpartum people (Table 1). Postpartum participants were predominantly ages 30–34 (31%), and all identified as cis-gender female. Most HCPs identified as cis-gender female (93%) and white (79%). Two domains emerged: (1) need, content, and delivery of IPV resources in the postpartum unit; and (2) barriers and facilitators to implementation. In quotations in the subsequent sections, PP refers to a quotation from a postpartum person and HCP from a HCP.

Table 1.

Demographics

| Postpartum people | n = 16 |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| 20–24 | 3 (19%) |

| 25–29 | 2 (13%) |

| 30–34 | 5 (31%) |

| 35–39 | 4 (25%) |

| 40–44 | 1 (6%) |

| Did not respond | 1 (6%) |

| Racea | |

| Asian | 1 (6%) |

| Black, African American | 3 (19%) |

| Biracial | 1 (6%) |

| Hispanic | 1 (6%) |

| White | 9 (56%) |

| Did not respond | 1 (6%) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Hispanic/Latino | 1 (6%) |

| Non-Hispanic/Latino | 14 (88%) |

| Did not respond | 1 (6%) |

| Child age (at time of interview) | |

| <1 month | 5 (31%) |

| 1 month | 4 (25%) |

| 2 months | 2 (13%) |

| 3 months | 2 (13%) |

| 4 months | 2 (13%) |

| Did not respond | 1 (6%) |

| Number of children | |

| 1 | 7 (44%) |

| 2 | 7 (44%) |

| 3 | 1 (6%) |

| Did not respond | 1 (6%) |

| HCPs | n = 14 |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Female |

13 (93%) |

| Male |

1 (7%) |

| Race | |

| Asian |

1 (7%) |

| Black, African American |

1 (7%) |

| Biracial |

0 (0%) |

| Hispanic |

1 (7%) |

| White |

11 (79%) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Hispanic/Latino |

1 (7%) |

| Non-Hispanic/Latino |

13 (93%) |

| Profession/specialty | |

| Pediatrician |

3 (21%) |

| Lactation consultant |

2 (14%) |

| Nurse practitioner |

2 (14%) |

| Postpartum registered nurse |

7 (50%) |

| Years of experience | |

| <1 |

3 (21%) |

| 1–5 |

3 (21%) |

| 6–10 |

3 (21%) |

| 11–15 |

0 (0%) |

| 16–20 |

1 (7%) |

| 20+ |

4 (29%) |

| Years in postpartum unit | |

| <1 |

4 (29%) |

| 1–5 |

5 (36%) |

| 6–10 |

3 (21%) |

| 11–15 |

0 (0%) |

| 16–20 |

0 (0%) |

| 20+ |

1 (7%) |

| Did not respond | 2 (14%) |

Participants could select more than one option.

HCP, health care provider.

To be inclusive of all birthing experiences, the authors use gender-affirming language throughout this article. The authors specifically refer to birthing people as “postpartum people.” To honor the voices of our participants, the authors did not change any quotes; many participants use gendered language (i.e., “mom” or “mother”) when referring to postpartum people. Table 2 includes additional representative quotations.

Table 2.

Representative Quotes

| Domain 1: need, content, and delivery | |

|---|---|

| Theme 1. Postpartum people are often asked about their IPV experiences but are not universally provided education or resources around IPV | |

| Subtheme 1: Postpartum people were often asked about home situation during intake | That's what I would surmise, that it just needs to be part of intake of demographic information, and it's incorporated into the demographics such that the demographic information does give you background information that would potentially lead you to ask a second level, maybe, of questions or, at least, prompt the nurse, or whomever's gonna see them next on the patient side, to follow through with that demographic piece. (HCP04) |

| Subtheme 2: Resource provision only occurs when there are “red flags” or disclosures | Sometimes we will have moms who will get—usually it's because they have housing instability, that they'll sometimes be able to get into shelters from [hospital], that they go straight over there. Gosh. It's been maybe one in the last five years that actually disclosed, like, “I am not in a safe relationship,” and we actually got her taken from the hospital away from the dad, but I don't know what happened on follow up. (HCP02) |

| It's just basically reaching out to social work. I wish it didn't all fall on social work, but we try to reach out to social work and utilize them because they know a lot more of the extra resources. I wish we had more at our disposal that we could handle the moms while we're still there, but it basically falls on social work a lot. (HCP03) | |

| Theme 2. Desire for IPV information and resources that covered a variety of IPV types and manifestations | |

| Subtheme 1: Both HCPs and postpartum people identified a need to educate on all types of IPV | I have had a few moms reveal to me that, in the postpartum period, that, at the time where their doctors are telling them, “You should not be having sex because you need to heal,” a lot of dads are pushing, pushing, pushing, pushing, and there's a lot of pressure there. There's even an element of sexual violence as well. (HCP02) |

| I feel as if—of course, any person usually with common sense can think domestic violence is just violence. It's physical. But a lot of people, they don't take emotional, mental—you know, the controlling—those type abuse symptoms as serious, and they are. These patients are isolated. They don't have support. They feel hopeless. They don't know where to go, so I feel like it just being IPV in general, it shouldn't just be addressed as that. It should give those examples. Hurting someone is more than just with a fist. It's with words as well. It's with actions. It's not just being hurt physically. (HCP13) | |

| Just what it looks like and teaching them what gaslighting is, ‘cause that's a very common psychological thing that happens and makes you think you're not being abused. Just letting them know what's normal and what's not normal emotionally. (HCP09) | |

| I would say absolutely everyone just because a lot of people—like how you said, there's misconception with domestic violence because there's so many different types… Like someone that's in a financially abusive relationship might not look at that as domestic violence. (M07) | |

| You could put signs, like different forms of abuse, so they'll know ‘cause some people don't know, they think it's normal. Some people think that this is supposed to be happening, but it's really not, so that should be added in there as well. (M15) | |

| Theme 3: Considerations of partner involvement and presence | |

| Subtheme 1: Postpartum people identified a need to involve the partner in prevention strategies but HCPs saw safety concerns with including a support person in IPV discussions | It's already a heightened area of concern because of the nature of what it's talking about. There's just inherent risk to the patient of disclosing this information and their personal safety potentially. (HCP04) |

| I think it really depends on how you approach it. If you're just giving the family, here's a resource sheet that we give to all our new mothers. It has a variety of resources on there from information on food insecurity to housing and whatever. If the domestic violence stuff is embedded in there, it doesn't even have to be brought up in front of the partner. It's just there, and it's handed to the mother. I don't know that it would—I mean, to me, it would make me uncomfortable in a situation where I know that the partner was the perpetrator to be able to say, “Here's the resources” and include domestic violence resources when what's he gonna think? Is he gonna retaliate because she disclosed something that he didn't want her to disclose? (HCP05) | |

| I would say it probably should become something like that where as part of the discharge package is that you need to have reviewed a short blip on this. I think that should be for the partner, spouse, for both, and then they should probably, I would say, should do it—because of technology, they can do it on their device so that it's a little bit more—it may be more stressful to watch something like that. The Shaken Baby, it's your baby. You probably wanna watch it together with your partner, spouse. This probably makes more sense to be done on a personal, individual, that all—and it could be anybody who's gonna be a partner or spouse or support who enters the room. Maybe that's something that's signed up to be the support person would have to answer. It may not be that—‘cause maybe another person who's there also may have—partner violence may not be the partner of the person that's sitting in the bed, but it might be at their home, right? (HCP04) | |

| It's hard because I think both the support person and the patient needs to hear it, but it might be almost easier to talk to the patient alone. I'm not sure. Maybe there's a component that can be shared with both of them there, and then if possible, whenever the patient is hopefully alone at some point, the nurse can continue and talk about just parts that apply only to her. (HCP09) | |

| I would say it could be for both because females can definitely be abusive as well. It's just typically a male abusing a female, but there are females that abuse males, and we never know that situation. It could just give “em somethin” for them to call, be like, “Listen, if you're feeling overwhelmed, or you come upon somethin’ that you're not sure of or don't know how to handle, here's the number for you to call to help,” or even take it as a support as like, “Listen, if you feel like she's bein’ any different or she's bein’ distant, call and ask how can I help her get through this part and help her deal with it,” ‘cause there can be many reasons why you call. You can call to get information how to deal with somebody or for yourself. (M03) | |

| I think just having a consultation with both partners and what they can do for each other and for the baby and financially to set themselves up for success once the baby gets here, I think, would be a proactive way of handling it. (M06) | |

| Just one more thought too which is, that I'm not also making the assumption that dealing—[extraneous noise] oh, okay, sorry—that the only options are to leave or not. Maybe part of it is their opportunity for change or to get treatment or for help as well for the partner who's—so that maybe there's—okay—so there's a middle ground as well. If it's at a point where somebody's like, “I've exhibited some of these signs and behaviors and words,” whatever it might be, maybe it's also like, “Hey, here's some treatment options for you,” or “Here are some ways—.” Maybe the answer is not just automatically somebody leaves or not. I think having all of those options available and certain resources just depending on what is being shared. That would be helpful. (M11) | |

| Theme 4. Desire for universally distributed IPV education | |

| Subtheme 1: HCPs expressed concern about knowing who to provide resources to without screening | I think that the challenge is you've got 20 things to do for the patient. If IPV took 90 percent of the time, then you wouldn't be able to do the other part. How do you find, I guess, the key elements that would be like the red flags? What are the things that help you quickly identify these situations, whether they're—and if they can be somewhat subtle, but powerful, right? (HCP04) |

| Well, I think screening would be really helpful, like making sure—and they might do that in triage, but just really making sure they're screening to make sure moms feel safe, and that they don't—if they want help, they have it. I feel like just right off the bat making sure that they know that this is a safe place and that we have the right resources available. Maybe like little pamphlets. (HCP14) | |

| If there are three questions you can ask that two of those answers give you a this is something you need to follow up on, that's easier than having to spend 15 minutes. [1] Part of it, you're building a relationship. There's a lot. Each of us walks in and is also received differently. Even though we all could get the information. We could ask the same questions. Me as a male coming in to ask the questions versus more like when it's a woman, totally—you're gonna get different answers to the same question, not for any other reason than that comfort level and wherever they are in that situation. I don't know what that—what the references are on that on who is coming in to ask the questions versus nurses or physicians, men versus women—how that plays out in extracting this having the conversation about this. (HCP11) | |

| I mean, I think that screening is a good place to start because there may be that person that's ready to talk about it that has hit a point where they're like, “I need to talk to somebody.” I think most people who should say yes aren't going to. I feel like it's a good place to start. Maybe a good place to start the conversation even. (HCP06) | |

| Subtheme 2: Postpartum people identified barriers to disclosure including shame and fear of CPS involvement | I would say probably go to every room because if there's—if it's a thing where somebody might be maybe scared to speak up or embarrassed. Plus now, there's a baby. They might have a lot of fears about if somehow it could maybe make them look bad as a mother, and then they're worried about, maybe, if they bring this up. I guess what I'm trying to say is it could—somebody might not reach out because they just had a baby, so they might have a lot of new fears and anxiety, so they might not—they might less likely to reach out on their own if they were not reaching out before, for whatever reason. I would say having someone stop in every room, it's giving that extra opportunity for someone to reach out if they need help with that. (M01) |

| I think it should be universal ‘cause you never know how—what someone goes through. Even if it's not physical abuse, there's also—what's it called? Even by words. If you have your partner that's disrespecting you verbally, there's verbal abuse as well. I feel like it should be a universal thing that should go around and be spoken about. (M13) | |

| I think the challenge is again our goal is not for a mother to disclose because she may not be ready to disclose what's happening. Really to be able to communicate to us that there is some stress. Sometimes they may be very vague about what the stresses are, but that may be a family that you wanna offer this universal resource list to. They may not be saying they're experiencing some domestic issue, but that by saying life has been really stressful at home lately, that may be their way of saying yes there is. (HCP05) | |

| You don't wanna be like—if you talk to a social worker, I think a lot of times people, either individuals who have dealt with them in the past for negative reasons or people who, like me, I'm just educated, and I'm—I overthink things. I'm like, “If I say the wrong thing, they're gonna take my kid away.” (M06) | |

| Subtheme 3: Postpartum people emphasized the need for universal resource provision even if there's no disclosure | Also thinking it doesn't have to be of lower-class families. Domestic violence and interpartner violence can happen in any single household. Even those that you think everything's perfect—they're living in the run-of-the-mill neighborhoods and they have the best resources. Things are occurring in their homes too, whether it's whatever stressors could be provoking it, it's occurring all around us. (HCP03) |

| I think it should be brought up with our normal teaching just so they feel like, “Are they just targeting me?” Like that, you know what I mean, like did they feel overwhelmed and over like, “Oh, are they attacking me type thing?” I think it should just be in the normal, “This is what's in our everyday teaching.” (HCP10) | |

| Sometimes we give the father something to do like go make the follow-up appointment out at the desk, and so we have a few minutes that we can talk to the mother in the room. We certainly can get a phone number for the mother and call her after the visit to review whether or not there's any further ongoing issues. [name] has given us a lot of instruction recently that it may not be as important to have a parent disclose whether that's happening or not. It may be better to just be a universal resource provision [coughs] so that all of our families have the resources in case it happens to them at any point in time. They know where to go for the women's shelter. They know where to go to locate some of those resources in the community. (HCP05) | |

| Just give the resources. That's the biggest thing. ‘Cause a lot of people, when those things are happening, they don't really have anybody. If they had people, they wouldn't be going through that, what they're going through. I just feel like—I wouldn't say it like that, but a lot of people that go through that, they don't have anyone to turn to. That's why they keep going through it, because or things happened in the past. Just the resources is the biggest thing for me. (M02) | |

| Subtheme 4: Postpartum people and HCPs identified a variety of resources to be distributed in the postpartum unit | I do know that [community resource] is another resource too, that mom could drop off the kids if she needed to, but what to do after that, other than get social work involved, I don't have a great wheelhouse. (HCP02) |

| Domain 2: barriers and facilitators | |

|---|---|

| Theme 1. Need for standardized HCP training and care procedures |

Not that much time to—and I have to teach, and we have to discharge, and so I would say time is absolutely a burden. Then, sort of lack of knowledge of what to do if they told us something's going wrong. I can tell ‘em, like, “Oh, that really sucks. I'm so sorry. You should always feel safe in your relationship. You're worth it.” I can do that part, but what do I do about the practicality of it? I do know that [community resource] is another resource too, that mom could drop off the kids if she needed to, but what to do after that, other than get social work involved, I don't have a great wheelhouse. (HCP02) |

| For the most part if Mom is—it's a tricky question. In some cases, there's no problem, I think, especially now with access to medical records. In the case that I told you, that would be very tricky [laughter] because of probably the partner might have access to that. They might have access to the personal, medical information of the mother, so it can be tricky. I don't know if there's a 100 percent, direct answer to that. I think, unfortunately, for now, I would go case-by-case, depending on the risk that that documentation might impose to the mother. The fact that I don't document anything doesn't mean that I'm not moving up and down 30 resources for her if I'm really concerned. You know what I mean? I think, as of now, I will be more strategic on a case-by-case basis. (HCP01) | |

| It's just you're burning through all these people, and younger generations and things may not know as much about domestic violence. You know, you can only learn so much in nursing school versus doing a little bit of research in it or being provided the opportunity of education, like I said, in training. Having someone from a domestic violence shelter or doing a presentation for them so they know exactly what it is. (HCP13) | |

| It's just more like more education for us, I guess. ‘Cause I feel like we just gloss over the subject. Though it's very important, I just feel like it's also very difficult to exactly know what to say or how to train people to do it. I can't recall getting—I know about it, but it's like how do we really help them? It's hard to explain. It's more like a—I just feel like I just need more training on how to talk with them, like with the hardest thing for me. (HCP14) | |

| I'm kinda iffy on that ‘cause I feel like everything should be separated. You know what I mean? Even though that happened to the mom, nothing has happened to the child. It doesn't mean that the dad's going to abuse the child or anything like that. I don't know about—I think it's best just to keep it separate, but unless it give—the child is in immediate danger or anything like that, then I really don't think they should be in the baby chart. I'm not expert or anything like that, so. I just feel like also making sure that you're giving people a chance as well. Even though they are abusing that person, it doesn't mean that they're gonna abuse their child. I don't know. That's a hard thing to do, but it's just—I don't know. That's just how I feel. (HCP14) | |

| Theme 2. Limited staff capacity |

I think that most of those, we have social workers at the hospital that typically become involved in that situation. Then they tend to be the resource point person for mothers as far as the resources that are in the community. If they're already hooked up, pre-delivery, through the OB offices, and then they, I think—then if they are coming back to us, specifically, I guess just ensuring that they are connected and getting the necessary follow-through on any of those sort of things. Yeah. I think they're just trying to—our touch points are a short time. We're there for 10 or 15 minutes with the family. Then just, maybe, coordinating and talking to the nurses that may be caring for mother and baby. Then it's interfacing with the social services. Sometimes, there might be psychiatry or somebody else may be consulted if there is a higher need of that, or they're on any medications. (HCP11) |

| Again, this is where the lacking comes into play where we don't have—and I hate to say this—the time to bring up these conversations because this is a long conversation. It's not like, hey, let me address this, and it's gonna be a five-second conversation. It's just impossible. That's when we bring in other members of the team such as social work and expect them to basically do their part to interview the patient and things along that nature. We as nurses can't really do as much, so it's definitely kind of disappointing for us. We're not able to address the things that we need to due to ratios. (HCP13) | |

| Theme 3. Information exchange throughout the perinatal period |

I think that's a hard question because, even if they would get like more paperwork—because they get a lot of papers while they're there in the hospital. They get a lot of brochures; they develop a lot of papers. I don't know if there's going to be something put on a bulletin board so they can see it while they're in the room, but they need to have it at their disposal because I think if it's something that's just discussed or talked about, they're gonna feel too ashamed or they're gonna feel too embarrassed to bring it up themselves unless they're in a very harmful situation and, at that point, they're not thinking of themselves, they're thinking of their new baby. Because, if it's just themselves, I think they're willing to continue going through the pain that they've endured. (HCP03) |

| I think posters and bulletin boards in common spaces is probably a good touch point because if somebody walks down to the mini-kitchen to get a juice or somethin’, then they see that. It might just be that while they're in the room, they're just so overwhelmed with everything else, but then it's like, “Oh boy. Yeah.” Then that's just a reminder or identifies something that they can say, “Yeah. I need to talk to somebody about that.” It can give a reference or whatever or call this number or an 800 number of whatever it would be. I think in the common points, and probably part of the discharge packet, some sort of paper, flyer type of thing, or having it—we now have at Magee, these newborn, postpartum, 50-page, glossy books that are printed. (HCP04) | |

| If they are going through something like this, they should already know all these things before starting the mother and baby unit, especially in the mother and baby unit. Yeah, it's a good idea to share these things with the mother in the mother and baby unit, but they should have access to all these things anyway. (M16) | |

| Theme 4. Logistical challenges speaking to the postpartum person |

Certainly, on the adult side, it's still dealing with those things, but it's a little bit different dynamic when you're a pediatrician with a parent coming in, and you've got kids in the room. If they're infants, you can have a conversation ‘cause they may hear it, but they're not really discerning anything, but even a three-year-old hears something that can be challenging because how they understand what you might have talked about. Not that it's misinterpreted, but it just gets repeated in a way that's out of context. I think that's our other challenge. The space and time is a little bit challenging sometimes. (HCP04) |

| That's sometimes, also, the other problem is just identifying who's in the room so that when you have these conversations, that can certainly sway where the conversations might go so that there's confidentiality sort of stuff. I'm pretty comfortable with it if the partner's not in the room. I think that's the hardest part, is that most of the time the partner is there in the room. Especially if they are a controlling person, they don't wanna leave the room because they know that they'd be out of control in that moment. (HCP04) | |

| It's hard. Lots of times, it's not that you feel rushed with patients, but lots of times they're not willing to disclose a lot of their personal matters. They will sometimes—and oftentimes they're not alone in the rooms by themselves. Having them or trying to get a certain moment where you're able to talk to them about that and to kind of delve deeper into their personal life—it's hard. It can be very challenging. (HCP03) | |

| Theme 5. COVID-19 pandemic | I think that it should be targeted more towards when you go home just because with COVID as well. We used to keep our vaginal deliveries for two days and our postpartum deliveries for three days, but with COVID they've been letting people go home. Sometimes after 24 hours of delivery they're going home already. I feel like we're not having them in the hospital that long anymore. (HCP08) |

| We have huge turnover. That's gonna become an issue because now, these are inexperienced nurses mainly that come onto the unit, and so, we're starting over from ground one. They're gonna have to learn the signs. That's the only bad thing is the turnover is pretty high right now. With COVID, nobody wants to deal with it’ cause we're always exposed. They'll be like, “Oh, yeah, the dad in the room that yesterday, yeah, he tested positive for COVID,” and you're like, “Great.” (HCP07) | |

CPS, Child Protective Services; IPV, intimate partner violence.

Domain 1: need, content, and delivery

Theme 1. Postpartum people are often asked about their IPV experiences but are not universally provided education or resources around IPV

HCPs shared a variety of practices around addressing IPV in the postpartum unit, including asking about the patient's home situation and looking at the patient's chart to see if safety concerns arose during prenatal visits. Postpartum people reported that they were asked about IPV during prenatal visits and upon initial intake (usually asked about feeling safe at home), but not provided additional information around IPV while in the postpartum unit: “Basically the standard conversation. Do you feel safe at home? Are you experiencing any domestic violence?” (PP07). Another postpartum person discussed her experience with screening during her prenatal appointment:

Even though I was with my husband, they asked him to stay outside… The reason why they did that, I suppose, because they wanted to ask those domestic violence questions, making sure that I felt safe. (PP06)

Both postpartum people and HCPs shared that provision of education or resources around IPV was limited to those who disclosed or who were deemed to be “high risk”: “It's just basically reaching out to social work. I wish it didn't all fall on social work, but we try to reach out to social work and utilize them because they know… the extra resources” (HCP03). Speaking about resource provision after disclosure, one HCP said, “It's been maybe one in the last five years that actually disclosed, like, ‘I am not in a safe relationship’, and we actually got her taken from the hospital away from the dad, but I don't know what happened on follow up” (HCP02). Likewise, patient participants indicated that they did not recall receiving any general IPV information: “nobody talked to me about my relationship” (PP16).

Theme 2. Desire for IPV information and resources that covered a variety of IPV types and manifestations

HCPs and postpartum people identified a need to educate and provide resources on multiple types of IPV. Participants spoke about how postpartum people might not recognize IPV that is not physical or might not feel comfortable seeking help. One HCP said, “But a lot of people, they don't take emotional, mental—you know, the controlling—those type abuse symptoms as serious, and they are” (HCP13). One HCP spoke about the importance of including sexual coercion in education:

I have had a few moms reveal to me that, in the postpartum period, that, at the time where their doctors are telling them, “You should not be having sex because you need to heal,” a lot of dads are pushing, pushing, pushing, pushing, and there's a lot of pressure there. (HCP02)

Theme 3. Considerations of partner involvement and presence

Postpartum people identified a need for partners to be involved in IPV prevention and education, but HCPs worried about the safety if the partner is included. An HCP said,

It would make me uncomfortable in a situation where I know that the partner was the perpetrator to be able to say, “Here's the resources” and include domestic violence resources. Is he gonna retaliate because she disclosed something that he didn't want her to disclose? (HCP05)

Postpartum people thought the potential benefits of intervention including partners outweighed safety risk. Postpartum people also thought it was necessary to have resources available for partners who use violence. One postpartum person said,

…that I'm not also making the assumption that the only options are to leave or not. Maybe part of it is their opportunity for change or to get treatment or for help …If it's at a point where somebody's like, “I've exhibited some of these signs and behaviors and words,”…, maybe it's also like, “Hey, here's some treatment options for you.” (PP11)

Theme 4. Desire for universally distributed IPV education

Most HCPs advocated for screening, as they expressed uncertainty around how to prioritize resource provision with knowing who is at risk:

Well, I think screening would be really helpful… just really making sure they're screening to make sure moms feel safe, and that they don't—if they want help, they have it. (HCP14)

HCPs had several hesitations to implement IPV screening in the postpartum unit, including safety and potential lack of comfort with the setting and individual conducting the screen:

I noticed in labor and delivery whenever we admit the patients in the admission assessment there's a question of like, “Do you feel safe at home?” … most people don't ask in private. I feel like there isn't really an opportunity for people to safely say no. (HCP08)

Postpartum people identified a need for resources to be provided to all parents, regardless of disclosure or screening results, and that some postpartum people may need resources in the future or to give to someone they know: “Just give the resources. That's the biggest thing. ‘Cause a lot of people, when those things are happening, they don't really have anybody… Just the resources is the biggest thing for me.” (PP02)

HCPs did not bring up universal education or resource distribution, but several answered affirmatively when asked if resources and education should be universally distributed. Several resources were shared to be universally distributed to postpartum people and partners, including food pantries, shelters, housing resources, counseling services, financial resources, IPV hotlines and text lines, and relevant support groups.

When asked about the best method for distributing these resources, participants mentioned the online health portal, videos, and links in discharge instructions. Participants noted that if a disclosure occurs, patients should be referred to the wrap-around services, and HCPs in the postpartum unit should facilitate follow-up with the postpartum provider.

Domain 2: barriers and facilitators

HCPs and postpartum people identified several barriers to addressing IPV in the postpartum unit, including institutional barriers such as understaffing and lack of training, knowledge barriers, and barriers related to the realities of the postpartum unit. Several facilitators were also noted, including staff training, continuity of care during the perinatal period, and opportunities to speak to the patient alone.

Theme 1. Need for standardized HCP training and care procedures

HCPs noted variation in provider practice and not understanding how to best support postpartum people experiencing IPV. HCPs suggested that having a standardized resource pamphlet to give to patients or instruction in EHR may help standardize care. HCPs also noted that staff may forget to discuss IPV or provide resources or may not know what to do if someone discloses IPV:

Then, sort of lack of knowledge of what to do if they told us something's going wrong. … I do know that [community resource] is another resource too… but what to do after that, other than get social work involved, I don't have a great wheelhouse. (HCP02)

HCPs expressed uncertainty around best practices when documenting IPV in the postpartum person's and baby's charts. They identified possible improved coordination of care between HCPs in obstetrics, the postpartum unit, and pediatrics if IPV was documented in the EHR. However, HCPs noted safety concerns of documenting IPV in charts if they did not document in a secure note.

Theme 2. Limited staff capacity

HCPs spoke about the institutional barriers to supporting postpartum people experiencing IPV, including lack of time per patient and understaffing: “Again, it's the time situation and the ratios for postpartum care that just makes it impossible” (HCP13). Postpartum people and HCPs spoke about certain HCPs like lactation consultants who may have additional time with each patient, and it may be more feasible for them to deliver interventions.

Theme 3. Information exchange throughout the perinatal period

HCPs discussed the overwhelming amount of information shared, including feeling like there are too many papers and information shared with new parents: “I think that's a hard question because, even if they would get like more paperwork—because they get a lot of papers while they're there in the hospital.” (HCP03)

HCPs and postpartum people spoke about the importance of multiple points of resource delivery including on bulletin boards, television screens, and discharge paperwork: “I think posters and bulletin boards in common spaces is probably a good touch point …I think in the common points, and probably part of the discharge packet, some sort of paper, flyer.” (HCP04)

Both postpartum people and HCPs also spoke about the importance of continuity of care in providing support for postpartum people experiencing IPV. HCPs noted that if done with attention to confidentiality, the EHR has potential to improve coordination of care between providers in obstetrics, social work, pediatrics, and on the postpartum unit:

If they're already hooked up, pre-delivery, through the OB offices… then if they are coming back to us, specifically, I guess just ensuring that they are connected and getting the necessary follow-through …Occasionally, they [social work] will maybe call us, but they'll typically just put their note in the chart that there is something more significant as far as the conversation that we need to help follow-through for the baby. (HCP04)

Postpartum people shared that this continuity of care aided in building trust and safety with HCPs: “I just wish that there would've been more time to talk to her [postpartum unit HCP], because I started building—when we were talking, I felt safe talking to her.” (PP02)

Theme 4. Logistical challenges speaking to the postpartum person

HCPs also spoke about a variety of barriers related to the realities of the postpartum unit, particularly speaking to patients alone without their partners, family members, or children. As an example, an HCP spoke about the lack of a safe space for older children to go to during private conversations with the postpartum person, which inhibits HCPs from discussing IPV confidentially:

If they're infants, you can have a conversation ‘cause they may hear it, but they're not really discerning anything, but even a three-year-old hears something that can be challenging because how they understand what you might have talked about… The space and time is a little bit challenging sometimes. (HCP04)

HCPs spoke about social workers as a facilitator to speaking to postpartum people alone by giving the partner or other family members a task that required them to leave the room.

Postpartum people identified several barriers to disclosure, including shame, fear of Child Protective Services involvement, safety concerns for themselves or their children, and pervasiveness of trauma: “I think a lot of times people, either individuals who have dealt with them [social workers] in the past for negative reasons or people who, like me, I'm just educated, and I'm—I overthink things.” I'm like, “If I say the wrong thing, they're gonna take my kid away” (PP06). Another postpartum person spoke about shame and embarrassment as barriers to disclosure:

I would say probably go to every room because if there's—if it's a thing where somebody might be maybe scared to speak up or embarrassed. Plus now, there's a baby. They might have a lot of fears about if somehow it could maybe make them look bad as a mother. (PP01)

Another postpartum person spoke about how a survivor might not disclose because they would be afraid that their only option would be to leave their partner:

Just one more thought too which is, that I'm not also making the assumption that the only options are to leave or not. Maybe part of it is their opportunity for change or to get treatment or for help … Maybe the answer is not just automatically somebody leaves or not. I think having all of those options available and certain resources just depending on what is being shared. (PP11)

Theme 5. COVID-19 pandemic

HCPs also noted several barriers related to the COVID-19 pandemic, including decreased time from delivery to discharge, difficulty speaking with patients alone, and increased staff turnover. HCPs explained that with the COVID-19 pandemic time to discharge is often 24 hours, and expressed concern that there would be enough time to “fit another thing in.” One HCP explained,

I think that it should be targeted more towards when you go home just because with COVID as well. We used to keep our vaginal deliveries for two days and our c-section deliveries for three days, but with COVID they've been letting people go home. Sometimes after 24 hours of delivery they're going home already. I feel like we're not having them in the hospital that long anymore. (HCP08)

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to explore the perspectives of postpartum people and HCPs on how IPV should be addressed in the postpartum unit. The perinatal period is a particularly important time for IPV-related interventions as prenatal and postpartum people are at increased risk of violence and are often in more frequent contact with health care.25,26 Although interventions exist to support IPV survivors during the prenatal and postpartum period,27,28 including at prenatal appointments, no interventions exist within postpartum units. Results from our study demonstrate a need to address IPV within postpartum units, and provide guidance on intervention content and delivery.

While HCPs noted the importance of screening, postpartum people reported that resource provision should be universal as survivors may not disclose IPV due to sigma, fear of Child Protective Services (CPS) involvement, or safety concerns. This finding is aligned with previous qualitative work from postpartum units of two delivery hospitals, which showed that survivors may not disclose to HCPs due to fear of violence escalation or criminalization of their partner.25 It also reflects studies noting that positive IPV screening rates in health care settings are often <10%, in contrast to nationally representative data showing that ∼50% of women have experienced IPV.29

Our study extends this work to note unique concerns in the pediatric health care settings, particularly around CPS involvement. Among IPV survivors using the National Domestic Violence hotline, one in three survivors did not report their experiences due to fear of mandated reporting, and 50% noted that mandated reporter involvement made their situation much worse.30 Fear of CPS involvement may be compounded during the perinatal period, during which people are often surveilled for risk factors, interact frequently with health care, and may be more likely to have a report filed against them.31

Postpartum people also highlighted a desire to include partners in IPV-related education and interventions. Standard of care as dictated by multiple professional organizations is to provide any IPV screening or intervention to women alone, without the partner, verbal children, or other family members. Such practices are necessary to ensure survivors can comfortably and confidentially talk about their experiences.

Compared with adult health care settings, the issue of partner presence may be more commonly encountered in pediatric health care settings because other caregivers may be involved and present during their child's hospitalizations and outpatient visits. Use of universal resource provision, rather than screening, may be a strategy to provide support and services to more families in pediatric care settings, and offer opportunity to focus on relational health and bolster survivor's social supports. Future work is needed to determine how to safely provide partners education around IPV.

The impact of COVID-19 on health care delivery systems was discussed as a potential barrier to supporting survivors. COVID-19 rapidly shifted health care delivery, catalyzed a move to virtual service provision, decreased in-person interactions with health care systems, and created staffing shortages.32,33 Past work demonstrated how COVID-19 served as a mechanism for abusive partners to control survivors (e.g., limiting access to nonhousehold supports under the guise of mitigating COVID-19 risk).34,35 COVID-19 also radically shifted victim service agency service delivery to provide more virtual and flexible services.36 As systems re-equilibrate during the current stage of the pandemic, there may be opportunity to reimage healthcare delivery especially by making institutional-level changes to better prepare for emergencies.

Both HCPs and postpartum people identified several institutional- or hospital-level changes that will be required to effectively support patients experiencing IPV. These findings extend previous qualitative work examining barriers to disclosure among postpartum survivors, which found that participants recommended creating a shift in the health care system's approach toward IPV (i.e., building continuity of care during perinatal period, eliminating time constraints and understaffing), and providing support for survivors and care providers (i.e., providing HCPs training on IPV).37

Previous work in a pediatric hospital also identified several institutional barriers such as increasing emphasis on clinical efficiency (as opposed to the time required to address IPV), lack of staff training, insufficient attention to staff vicarious trauma, and lack of social work capacity.38 Taken together, these findings show that multilevel strategies are needed and provider education without systems-level change is not sufficient to support survivors.

This study has several limitations. HCPs were recruited from one academic medical center, and postpartum people from a single hospital and university-run recruitment repository in the Northeast. This study was conducted in the United States; due to differing clinical practices in countries outside the United States, these findings may not reflect the experiences of HCPs and postpartum people. The perspectives of these participants may not be generalizable to other clinical settings. This study did not include perspectives from transgender and nonbinary birthing people, adolescent parents, partners, or non-English–speaking communities.

Future work should include their voices in research on IPV interventions. Particularly, transgender and nonbinary people may be more likely to experience IPV, and may have different experiences than cisgender women in the postpartum unit.39 It is critical that their voices are included in future studies concerning supporting IPV survivors in the postpartum unit. This study did not include the perspectives of obstetricians; future studies should explore their current practices and desired resources. Finally, postpartum people were not required to have experienced IPV to participate. While important to explore the perspectives of all postpartum people, there may be safety concerns related to some of the recommendations proposed by participants, including proving universal education to partners.

This study has several implications for further research and clinical innovation. Larger survey-based and longitudinal studies should explore these findings to generalize to other settings and HCPs. Given the conflicting opinions on screening, future work should elucidate the opinions of perinatal people and HCPs of screening during the perinatal period. In addition, more research is needed to triangulate these findings with postpartum people who identify as IPV survivors, particularly around inclusion of partners in IPV-focused education.

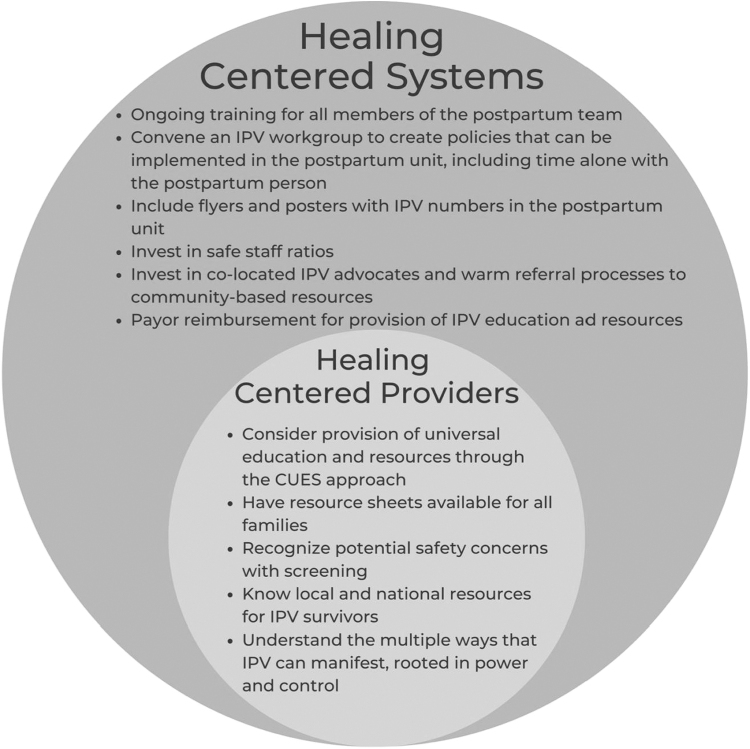

Results also have practice and policy implications. Healing-centered engagement is a powerful framework for health care systems to provide strength-based, survivor-centered care.11,40 A potential healing-centered approach is confidentiality, universal education, and resource provision (CUES), which advocates for provision of education and resources to all patients rather than just to those who disclose IPV.41,42 CUES also recognizes that some patients may disclose IPV, and recommends connecting them with hospital and community-based resources. This approach, which is an alternative to IPV screening and is recommended by the AAP, is aligned with participants' interest in giving resources universally.3 Further work is needed to develop and test a CUES process that can be safely implemented and sustained in the postpartum unit.

Given considerable implementation barriers, healing-centered engagement must extend beyond the provider level to also involve a systems-level approach. Health care systems can advocate for colocated IPV advocates in postpartum units (e.g., the AWAKE program), system-wide processes to connect survivors to local resources, flyers and posters with IPV helpline numbers in the postpartum unit, training for all members of the health care team on supporting survivors, and formation of IPV workgroups to guide postpartum unit protocols around supporting IPV survivors.

Vital to creating a survivor-centered health care response to IPV is ensuring that while standard procedures for supporting IPV survivors exist within the postpartum unit, there is enough flexibility in protocols to tailor to the unique needs of each survivor. Finally, health care systems must provide financial resources to ensure sustainability of systems-level approaches. As part of this, payors must reimburse supporting survivors rather than just identifying IPV. Figure 1 shows changes that can be implemented to promote healing-centered care within the postpartum unit.

FIG. 1.

Recommendations for supporting healing-centered systems and providers. CUES, confidentiality, universal education, empowerment, and support intervention; IPV, intimate partner violence.

Conclusions

This study is one of the first, to our knowledge, to examine the perspective of postpartum people and HCPs on IPV interventions in the postpartum unit. We found that while participants identified a need for IPV intervention in the postpartum unit, HCPs require additional training and institutional support to better connect survivors with resources. IPV has lifelong health impacts for postpartum people and their infants; developing interventions for the postpartum unit will help provide the support needed to promote the well-being of postpartum people and infants.

Authors' Contributions

S.S. contributed to writing—original draft; writing—review and editing. G.J. assisted with writing—review and editing. Er.M. performed analysis; writing—review and editing. J.S., A.-M.R., R.L., J.C., and K.R. designed conceptualization; methodology; writing—review and editing. M.R. contributed to conceptualization; methodology; writing—original draft; writing—review and editing.

Author Disclosure Statement

El.M. receives royalties for writing content for UptoDate, Wolter Kluwers, Inc. The other authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to this article to disclose.

Funding Information

This work was supported by Amy Roberts Health Promotion Research Award. Maya Ragavan is supported by a K23 (HD104925) from the National Institute on Child Health and Human Development. Dr. Kimberly A. Randell is supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development of the National Institutes of Health under award number K23HD098299. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1. Breiding M, Basile K, Smith S, et al. Intimate Partner Violence Surveillance: Uniform Definitions and Recommended Data Elements. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Atlanta, GA; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Smith SG, Zhang X, Basile KC, et al. National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey: 2015 Data Brief—Updated Release. National Center for Injury Prevention of Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Atlanta, GA; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Thackeray J, Livingston N, Ragavan MI, et al. Intimate partner violence: Role of the pediatrician. Pediatrics 2023;152(1):e2023062509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ragavan MI, Query LA, Bair-Merritt M, et al. Expert perspectives on intimate partner violence power and control in pediatric healthcare settings. Acad Pediatr 2021;21(3):548–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Randell KA, Ragavan MI. Intimate partner violence: Identification and response in pediatric health care settings. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2020;59(2):109–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bailey BA, Daugherty RA. Intimate partner violence during pregnancy: Incidence and associated health behaviors in a rural population. Matern Child Health J 2007;11(5):495–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Alhusen JL, Lucea MB, Bullock L, et al. Intimate partner violence, substance use, and adverse neonatal outcomes among urban women. J Pediatr 2013;163(2):471–476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Román-Gálvez RM, Martín-Peláez S, Fernández-Félix BM, et al. Worldwide prevalence of intimate partner violence in pregnancy. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Public Health 2021;9:738459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Adu A, Brown SV, Asaolu I, et al. Understanding suicide in pregnant and postpartum women, using the national violent death reporting system data: Are there differences in rural and urban status? Open J Obstet Gynecol 2019;9(5):547–565. [Google Scholar]

- 10. The American College of Obsteticians & Gynocologists. Intimate Partner Violence. The American College of Obsteticians & Gynocologists; 2022 [cited March 23, 2023]. Available from: https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/committee-opinion/articles/2012/02/intimate-partner-violence [Last accessed: October 20, 2023].

- 11. Ragavan MI, Miller E. Healing-centered care for intimate partner violence survivors and their children. Pediatrics 2022;149(6):e2022056980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bagherzadeh R, Gharibi T, Safavi B, et al. Pregnancy; an opportunity to return to a healthy lifestyle: A qualitative study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2021;21(1):751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Declercq E. Broadening the focus during pregnancy to total women's health, not just healthy babies. Health Affairs Forefront 2020;42(9):398; doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2023.00398 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hostetter M, Klein S.. In Focus: Improving Health for Women by Better Supporting Them Through Pregnancy and Beyond. Commonwealth Fund: New York, NY; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chaves K, Eastwood J, Ogbo FA, et al. Intimate partner violence identified through routine antenatal screening and maternal and perinatal health outcomes. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2019;19(1):357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Daoud N, Kraun L, Sergienko R, et al. Patterns of healthcare services utilization associated with intimate partner violence (IPV): Effects of IPV screening and receiving information on support services in a cohort of perinatal women. PLoS One 2020;15:e0228088; doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0228088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Deshpande NA, Lewis-O'Connor A. Screening for intimate partner violence during pregnancy. Rev Obstet Gynecol 2013;6(3–4):141–148. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Minns A, Peahl AF, Kusunoki Y, et al. Prevalence and screening perinatal intimate partner violence pregnancy risk assessment monitoring system 2012–15 [12N]. Obstet Gynecol 2019;133(1):153S–153S. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Beynon CE, Gutmanis IA, Tutty LM, et al. Why physicians and nurses ask (or don't) about partner violence: A qualitative analysis. BMC Public Health 2012;12:473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Buchko BL, Gutshall CH, Jordan ET. Improving quality and efficiency of postpartum hospital education. J Perinat Educ 2012;21(4):238–247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pavuluri H, Grant A, Hartman A, et al. Implementation of iPads to increase compliance with delivery of new parent education in the mother-baby unit: Retrospective study. JMIR Pediatr Parent 2021;4(2):e18830; doi: 10.2196/18830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2006;3(2):77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sandelowski M. Whatever happened to qualitative description? Res Nurs Health 2000;23(4):334–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Guest G, Namey E, Chen M. A simple method to assess and report thematic saturation in qualitative research. PLoS One 2020;15:e0232076; doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0232076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wadsworth P, Degesie K, Kothari C, et al. Intimate partner violence during the perinatal period. J Nurse Pract 2018;14(10):753–759. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hahn CK, Gilmore AK, Aguayo RO, Rheingold AA. Perinatal intimate partner violence. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am 2018;45(3):535–547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sharps PW, Campbell J, Baty ML, et al. Current evidence on perinatal home visiting and intimate partner violence. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 2008;37(4):480–490; quiz 490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Taft AJ, Small R, Hegarty KL, et al. Mothers' AdvocateS In the Community (MOSAIC)—Non-professional mentor support to reduce intimate partner violence and depression in mothers: A cluster randomised trial in primary care. BMC Public Health 2011;11:178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Perone HR, Dietz NA, Belkowitz J, et al. Intimate partner violence: Analysis of current screening practices in the primary care setting. Fam Pract 2022;39(1):6–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lippy C, Jumarali SN, Nnawulezi NA, et al. The impact of mandatory reporting laws on survivors of intimate partner violence: Intersectionality, help-seeking and the need for change. J Fam Violence 2020;35(3):255–267. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Harp KLH, Bunting AM. The racialized nature of child welfare policies and the social control of black bodies. Soc Polit 2020;27(2):258–281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mann DM, Chen J, Chunara R, et al. COVID-19 transforms health care through telemedicine: Evidence from the field. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2020;27(7):1132–1135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Begun J, Jiang J.. Health care management during Covid-19: Insights from complexity science. NEJM Catalyst 2020. [Epub ahead of print]; doi: 10.1056/CAT.20.0541 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lyons M, Brewer G. Experiences of intimate partner violence during lockdown and the COVID-19 pandemic. J Fam Violence 2022;37(6):969–977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. van Gelder N, Peterman A, Potts A, et al. COVID-19: Reducing the risk of infection might increase the risk of intimate partner violence. EClinicalMedicine 2020;21:100348; doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Garcia R, Henderson C, Randell K, et al. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on intimate partner violence advocates and agencies. J Fam Violence 2022;37(6):893–906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Pederson A, Mirlashari J, Lyons J, et al. How to facilitate disclosure of violence while delivering perinatal care: The experience of survivors and healthcare providers. J Fam Violence 2023;38(3):571–583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Randell KA, Evans SE, O'Malley D, et al. Intimate partner violence programs in a children's hospital: Comprehensive assessment utilizing a Delphi instrument. Hosp Pediatr 2015;5(3):141–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Peitzmeier SM, Malik M, Kattari SK, et al. Intimate partner violence in transgender populations: Systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence and correlates. Am J Public Health 2020;110(9):e1–e14; doi: 10.2105/ajph.2020.305774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ginwright S. The Future of Healing: Shifting From Trauma Informed Care to Healing Centered Engagement. 2018. Available from: https://ginwright.medium.com/the-future-of-healing-shifting-from-trauma-informed-care-to-healing-centered-engagement-634f557ce69c [Last accessed: April 23, 2021].

- 41. Miller E, Jones KA, McCauley HL, et al. Cluster randomized trial of a college health center sexual violence intervention. Am J Prev Med 2020;59(1):98–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Miller E, Tancredi DJ, Decker MR, et al. A family planning clinic-based intervention to address reproductive coercion: A cluster randomized controlled trial. Contraception 2016;94(1):58–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]