Abstract

Telomerase, a specialized cellular reverse transcriptase, compensates for chromosome shortening during the proliferation of most eucaryotic cells and contributes to cellular immortalization. The mechanism used by the single-celled protozoan malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum to complete the replication of its linear chromosomes is currently unknown. In this study, telomerase activity has for the first time been identified in cell extracts of P. falciparum. The de novo synthesis of highly variable telomere repeats to the 3′ end of DNA oligonucleotide primers by plasmodial telomerase is demonstrated. Permutated telomeric DNA primers are extended by the addition of the next correct base. In addition to elongating preexisting telomere sequences, P. falciparum telomerase can also add telomere repeats onto nontelomeric 3′ ends. The sequence GGGTT… was the predominant initial DNA sequence added to the nontelomeric 3′ ends in vitro. Poly(C) at the 3′ end of the oligonucleotide significantly alters the precision of the new telomerase added repeats. The efficiency of nontelomeric primer elongation was dependent on the presence of a G-rich cassette upstream of the 3′ terminus. Oligonucleotide primers based on natural P. falciparum chromosome breakpoints are efficiently used as telomerase substrates. These results imply that P. falciparum telomerase contributes to chromosome maintenance and to de novo telomere formation on broken chromosomes. Reverse transcriptase inhibitors such as dideoxy GTP efficiently inhibit P. falciparum telomerase activity in vitro. These data point to malaria telomerase as a new target for the development of drugs that could induce parasite cell senescence.

Recent advances in telomere biology have been exciting and have pointed to telomeres as important elements for cell survival. Telomeres, the essential genetic elements at the ends of eucaryotic chromosomes, consist of proteins and simple G-rich repeats which are highly conserved among widely diverged eucaryotes (for reviews, see references 2, 14, and 40). These ends of linear duplex DNA cannot be fully replicated by the conventional DNA polymerase complex, which requires an RNA primer to initiate DNA synthesis (25, 37). In normal human cells, short terminal deletions occur with each cell division probably due to the terminal sequence loss that accompanies DNA replication (11, 13). For example, the average loss of human somatic telomere DNA has been estimated to be 30 to 200 bp/cell doubling in vitro (10). Telomere shortening is especially a problem for rapidly dividing cells, and this shortening can lead to cellular senescence and death after a limited number of cell divisions, as has been demonstrated for the yeasts Kluyveromyces lactis, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, and Schizosaccharomyces pombe (17, 21, 24, 31). This sequence loss is usually balanced by the de novo addition of telomere repeats onto chromosome ends by a ribonucleoprotein enzyme called telomerase. This enzyme complex is a specialized reverse transcriptase which uses its RNA moiety to template the addition of new telomeric repeats to chromosomal DNA ends (for reviews, see references 5, 7, and 8). In a wide phylogenetic range of eucaryotic cells, telomerase compensates for potentially fatal telomere shortening and probably contributes to the cell immortalization (for a review, see reference 10).

Unicellular protozoan parasites such as Plasmodium species and trypanosomes represent a large group of human and animal pathogens with significant impact on the health and economies of many countries. More than 300 million people are infected by malaria parasites, and infections caused by Plasmodium falciparum, the most virulent human malaria species, are responsible for approximately 1 to 1.5 million deaths per year (38). Protozoan parasites are generally capable of very rapid replicative divisions, and in many cases the severity of the disease correlates with the high parasite load found in the vertebrate host. Given that protozoan cells can undergo an unlimited number of divisions, they must have a mechanism for overcoming the problem of incomplete chromosome replication. Thus, interfering with parasite telomere maintenance might limit growth of these parasites.

Telomerase activity has not previously been reported for this group of pathogens. However, molecular analysis of a number of randomly broken chromosomes occurring naturally in P. falciparum suggested that a plasmodial telomerase might be implicated in the reformation of a functional telomere by the addition of new telomere repeats to broken chromosomes (for a review, see reference 28). The 14 linear chromosomes of P. falciparum are bounded by closely related G-rich repeats, and the most frequent type, of telomere repeat motifs consists of GGGTTT/CA (4, 35). The average telomere length has been estimated to be approximately 1.3 kb (1, 29).

This study intend to uncover the mechanism implicated in malaria parasite chromosome length maintenance. Several attempts to demonstrate specific plasmodial telomerase activity failed due to the relatively low level of sensibility of the conventional telomerase assay (6). Here, we present, for the first time, evidence for a specific telomerase activity in cell extracts of P. falciparum. We developed a modification of the recently reported, highly sensitive PCR-based telomere repeat amplification protocol (TRAP) (15). The in vitro telomerase assay Pf-TRAP demonstrated that P. falciparum telomerase efficiently elongates, in an RNase A-sensitive manner, oligonucleotide primers with short telomere-like sequences at the 3′ end. Primers having nontelomeric sequences such as poly(C) or poly(A) at the 3′ end could be efficiently elongated when a telomere repeat cassette was placed close to the 3′ end. DNA sequence analysis of the telomerase products of various primers did not reveal any exonuclease activity of the plasmodial telomerase. Very importantly, the plasmodial telomerase can be efficiently inhibited in vitro by reverse transcriptase inhibitors. The potential induction of cellular senescence through inhibition of malaria telomerase will be discussed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Manufacturers of reagents.

Azidothymidine triphosphate (AZT-TP) was a gift of S. Sarfati, Institut Pasteur, Unité de Chimie Organique. RNase A was purchased from Boehringer Mannheim, and dideoxy GTP (ddGTP) was purchased from Pharmacia. Oligonucleotides were obtained from GENSET SA and were purified on polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) gels before use.

Cell culture conditions.

P. falciparum strains were maintained in culture as described by Trager and Jensen (34). P. falciparum lines included Palo Alto Uganda (9) and FCR-3 (34). Schizont-infected erythrocytes were purified by the gel flotation method (26).

Preparation of cytoplasmic and nuclear cell extracts of P. falciparum.

P. falciparum-infected erythrocytes were enriched by the gel flotation technique, and the parasites were liberated from the erythrocytes by subsequent treatment with 0.15% saponine in 1.5 volumes of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 5 min at room temperature. Free parasites were diluted in 5 volumes of PBS and recovered by centrifugation for 10 min at 2,400 × g. The dark parasite pellet was washed twice in PBS. The 3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)-dimethyl-ammonio]-1-propanesulfonate (CHAPS) buffer used for the lysis of human cells in the TRAP assay (15) did not efficiently lyse P. falciparum membranes. A total of 109 parasites were lysed mechanically in a volume of 200 μl of buffer B (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EGTA, 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 10-μg/ml leupeptine, 10-μg/ml pepstatine, 10% glycerol) by using a homogenizer (Kontes; size 19, 60 to 80 strokes). These conditions lyse the parasite membrane but leave the nucleus intact. After centrifugation for 1 h at 4°C and 17,600 × g (Eppendorf centrifuge; Sigma), the supernatant, which was called the cytoplasmic fraction, was aliquoted and stored at −70°C. The pellet containing the nuclei was resuspended in 200 μl of buffer B, lysed by sonication, and centrifuged as described above. The supernatant was called the nuclear fraction. The cytoplasmic and the nuclear fraction contained telomerase activity. For practical reasons, all P. falciparum telomerase experiments presented in this work were performed with the cytoplasmic fraction. Cytoplasmic cell extracts of HeLa were prepared as previously described (15).

TRAP and Pf-TRAP assays.

Telomerase activity assays of HeLa cytoplasmic extracts were performed essentially as described by Kim and collaborators (15), with the following minor changes: we used the reverse primer CX with a gas chromatography (GC) clamp at the 5′ end (3), and, for the hot start PCR, AmpliTaq Gold DNA polymerase (Perkin-Elmer) was used according to the recommendation of the manufacturer.

The assay developed to measure plasmodial telomerase activity (called Pf-TRAP) was based on the protocol developed by Kim (15), with several important modifications. The TS primer PfTS-I (5′ AATCCGTCGAGCAGAGTTCA 3′) contained a P. falciparum-specific telomere sequence at its 3′ end, and the reverse primer PfCX (5′ GGCGCGTG/AAACCCTG/AAACCCTG/AAACCC 3′) had three repeats complementary to the two major plasmodial telomere repeats GGGTTT/CA and a GC clamp at the 5′ end. P. falciparum telomerase (corresponding to 106 parasites) was allowed to extend the PfTS-I primer (0.1 μg) for 1 h at 37°C in 48.2 μl of the buffer described by Kim (15). The PCR was performed in a 50-μl final volume by adding 1.8 μl of a mixture containing AmpliTaq Gold (2.5 U), PfCX primer (0.1 μg), and [α-32P]dTTP (3 μCi). The PCR was initiated with 10 min of incubation at 94°C (activation step of AmpliTaq Gold), followed by 31 cycles with a 10-s denaturation step at 94°C, 30 s of annealing at 55°C, and a 1-min extension step at 72°C. As a control for nontelomerase-mediated incorporation, we pretreated cell extracts for 30 min at 37°C with 10 μg of RNase A or for 10 min at 95°C. The specificities of the plasmodial primers PfTS-I and CX on cell extracts prepared from noninfected erythrocytes and HeLa cells were tested. No telomerase elongation products were detected in these extracts. Products were resolved by electrophoresis in nondenaturing 15% polyacrylamide gels (Mini-Protean II cells; Bio-Rad) for 150 min at 120 V in 1× Tris-borate-EDTA buffer. The gels were washed briefly for 5 min in distilled water and exposed without drying to Kodak film for 1 to 12 h.

Inhibition studies of telomerase activity in vitro were performed in the presence of increasing amounts of AZT-TP (final concentration, 1 μM to 1 mM) or ddGTP (final concentration, 1 to 50 μM) in the Pf-TRAP reaction mixture. Pf-TRAP products were quantified with a PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics). The gels were phosphorimaged for 1 to 3 h. The mean values of duplicate reactions were taken from a central region of each gel, and the standard deviations were calculated. The values from RNase A-treated reactions were subtracted as background. The 0 μM inhibitor reaction was used as 100% total telomerase activity. As control PCR, a synthetic 180-bp DNA fragment carrying DNA sequences at one end corresponding to PfTS-I and carrying DNA sequences on the other end corresponding to the PfCX primer was amplified by using the standard PCR conditions of the Pf-TRAP assay. The highest inhibitor concentration used in these studies did not interfere with PCR amplification of the synthetic PfTS-I–CX fragment.

Cloning and DNA sequence analysis of telomerase elongation products.

Telomerase elongation products corresponding to 5 volumes of the standard Pf-TRAP assay were concentrated by ethanol precipitation in the presence of 2 μg of glycogen (Appligene-Oncor) and were separated on one lane on a 15% polyacrylamide gel. After exposure, a region of the gel superior to six bands was cut out and cut into fine pieces by using a sterile razor blade. The pieces were resuspended in 1 volume of elution buffer (0.5 ammonium acetate and 1 mM EDTA [pH 8.0]), and the suspension was incubated at 37°C overnight on a rotating wheel. After centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 10 min, the supernatant was recovered and the DNA was precipitated with 2 volumes of EtOH in the presence of 2 μg of glycogen. The Pf-TRAP products were cloned into pCRII (Invitrogen). Plasmid DNA was purified through spin columns (Qiagen) as specified by the manufacturer. Double-stranded DNA sequencing reactions were performed with the AmpliCycle Taq polymerase sequencing kit (Perkin-Elmer). Two independent clones for each primer elongation were sequenced.

RESULTS

Telomerase activity in cell extracts of P. falciparum.

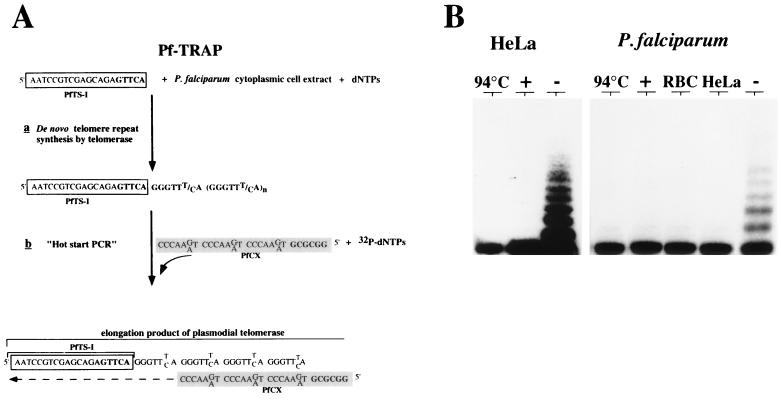

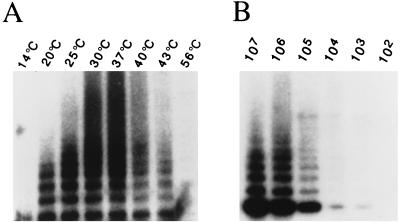

The fact that P. falciparum can repair broken chromosomes by the addition of telomere repeats, i.e., de novo telomere formation, suggested the presence of a plasmodial telomerase (28). However, the conventional telomerase activity assay developed by Greider and Blackburn (6) did not detect telomerase activity in cell extracts of P. falciparum (28a). Recently, a more sensitive PCR-based telomerase detection assay called TRAP has been reported (15). A modified version of the TRAP assay (termed Pf-TRAP) permitting in vitro detection of P. falciparum telomerase activity for the first time is shown diagramatically in Fig. 1A. Current data suggest that in most eucaryotic cells, the telomere forms a 3′ single-stranded overhang onto which telomerase synthesizes additional G-rich repeats. Therefore, a substrate primer containing a Plasmodium-specific telomere repeat sequence (PfTS-I; for DNA sequence, see Table 1) at its 3′ end was incubated with cellular extracts from blood stage parasites cultivated in vitro. A reverse primer (PfCX) was then added, and hot start PCR was carried out. PCR-amplified elongation products were then separated by 15% PAGE. As shown in Fig. 1B, a typical TRAP ladder of variable intensities was detected when Plasmodium cell extracts were assayed. This activity was sensitive to heat and RNase A treatment; these features are typical of telomerase (7). The same amounts of protein extracts from uninfected erythrocytes and HeLa cells did not show any activity by the standard Pf-TRAP assay. The spacing of the plasmodial ladder is slightly larger than the six-nucleotide ladder of the human telomerase in HeLa cells (Fig. 1B). This observation is consistent with the expected P. falciparum telomere repeat length of 7 bp. Enzymatic activity was detected in nuclear as well as in cytoplasmic extracts prepared from P. falciparum-infected erythrocytes (trophozoite-schizont stage). Subsequent telomerase experiments were performed with the cytoplasmic cell fraction. The plasmodial telomerase shows maximal activity in a temperature range of between 30 and 37°C (Fig. 2A). Enzymatic activity of cytoplasmic extracts corresponding to 105 to 107 parasite equivalents could be readily detected after autoradiography for 1 h, and 103 equivalents could be detected after overnight exposure. The protocol of the optimized Pf-TRAP assay is described in Material and Methods.

FIG. 1.

Detection of P. falciparum telomerase activity in cell extracts of blood stage parasites. (A) Recently, a highly sensitive PCR-based telomerase assay was developed (15). In the TRAP assay, telomerase first elongates a synthetic oligonucleotide that carries a telomeric sequence at the 3′ end (6), which then serves as a template for PCR amplification. This assay was modified to detect telomerase activity in plasmodial cell extracts by substituting P. falciparum-specific oligonucleotide primers and was called Pf-TRAP. (B) Fractionation of 32P-labeled elongation products on a nondenaturing 15% polyacrylamide gel. Elongation products of a control extract from human HeLa cells and P. falciparum cytoplasmic extracts from infected erythrocytes (RBC) are shown. Cell extracts were heated at 94°C or pretreated with (+) or without (−) RNase A prior to the telomerase assay as a control for nontelomerase-mediated incorporation of 32P label. Cell extracts from uninfected erythrocytes or HeLa cells did not have activity in the Pf-TRAP assay.

TABLE 1.

Elongation of telomeric and nontelomeric oligonucleotides by P. falciparum telomerase

| Oligonucleotide | Sequencea | Extension of telomeraseb |

|---|---|---|

| With telomeric 3′ end | ||

| PfTS-I | 5′AATCCGTCGAGCAGAGTTCA 3′ | +++ |

| PfTS-II | AATCCGTCGAGCAGAGTT | ++ |

| PfTS-III | AATCCGTCGAGCAGAGGG | + |

| With nontelomeric 3′ end | ||

| PfTS-IV | 5′AATCCGTCGAGCAGACCC 3′ | − |

| PfTS-V | AATCCGTCGAGCAGGTTCACCC | +++ |

| PfTS-VI | AATCCGTCGAGCAGAAAAA | − |

| PfTS-VII | AATCCGTCGAGCAGGTTCAAAAA | +++ |

| Derived from healed chromosome breakpoints | ||

| PfTS-VIII | 5′CACCAAGCACCACAGGTTCA 3′ | +++ |

| PfTS-IX | AGGCAATGTGTGGCGGCTTC | +++ |

| PfTS-X | AACTAGAAACATTTGTGCAAG | + |

DNA sequences of oligonucleotides used as telomerase substrates in this study. Primers PfTS-I to PfTS-VII have the core sequence published in the TRAP assay results (15) but differ at the 3′ terminus. Oligonucleotides PfTS-VIII to PfTS-X are based on naturally occurring break sites in the P. falciparum genes HRPI, HRPII, and Pf11-1, and their 3′ ends correspond to the breakpoint origins which have been healed by the addition of telomere repeats.

Relative efficiencies of telomerase elongation after 1 h of gel exposure are indicated.

FIG. 2.

P. falciparum telomerase elongation activity in vitro. (A) Temperature profile of telomerase activity of cytoplasmic cell extract; (B) detection limits of telomerase activity in diluted cell extracts of parasitized erythrocytes (P-RBC) by the Pf-TRAP assay. The values given are the parasite equivalents used in the assay deduced from the dilution.

Permutated telomeric sequence primers are elongated by the addition of the next correct base.

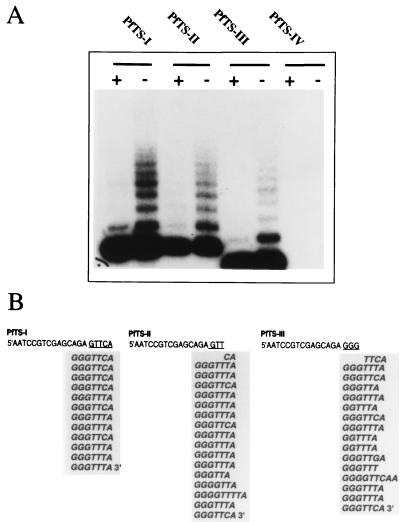

To analyze the interactions of the P. falciparum telomerase with different substrates, primers with permutated telomeric sequences at the 3′ terminus were used. The DNA sequences of primers PfTS-I, PfTS-II, PfTS-III, and PfTS-IV are shown in Table 1. The first three primers terminate in partial GGGTTCA repeats (-GTTCA, -GTT, and -GGG). PfTS-IV has a nontelomeric motif (-CCC) at the 3′ end. The Pf-TRAP assay reveals that oligonucleotides with short telomere-like motifs at the 3′ end can efficiently recruit plasmodial telomerase. The -GTTCA terminus gives a stronger signal than -GTT or -GGG (Fig. 3A). No telomerase activity was detected with primer PfTS-IV under these conditions.

FIG. 3.

Telomerase activity with telomeric primers. (A) Pf-TRAP assay with oligonucleotide primers PfTS-I, PfTS-II, and PfTS-III that contain short P. falciparum telomere repeat motifs of 5 and 3 bases. Pf-IV contains nontelomeric bases (-CCC) at the 3′ end. Only oligonucleotides with telomeric 3′ ends are efficiently used as substrates. Cell extracts were treated with (+) or without (−) RNase A. (B) De novo synthesis of DNA at the 3′ end of the primers PfTS-I to PfTS-III. The elongation reaction of one long extension product is shown for each input primer. The partial telomere repeat sequence at the 3′ end is underlined. Newly synthesized repeats are aligned and shown without the sequence of the Pf-CX primer. The initial sequence added to the primer depends on the telomeric DNA sequence at the 3′ terminus of the primer. The telomerase first completes a repeat before adding new telomere repetitions.

Molecular cloning and DNA sequence analysis of Pf-TRAP products of the primers PfTS-I to PfTS-III demonstrated that the initial extension of the primer depends on the 3′ end of the substrate. As shown in Fig. 3B, PfTS-I to PfTS-III are elongated by the addition of the correct nucleotide base in the classic telomere repeat sequence GGGTTT/CA. These results suggest that once the 3′ end of the primer is base paired with the putative P. falciparum RNA template, telomerase synthesizes de novo telomere repeats in phase with the aligned telomere repeat sequence. These findings are in agreement with the proposed telomerase elongation model (8). According to this model, the terminal telomere repeat is base paired with the complementary template sequence of the RNA component, the RNA is copied to the end of the template region, and translocation repositions the terminal repeat sequence to the 5′ template region.

Telomerase processing of nontelomeric 3′ ends.

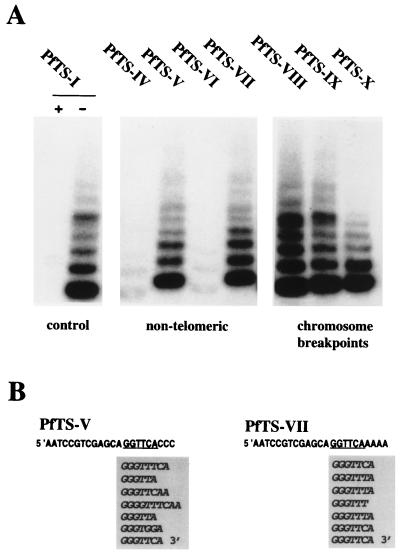

Spontaneous chromosome healing in P. falciparum results in the formation of new telomeres at the broken ends (28). Break sites with short telomere repeat motifs ranging from 2 to 5 bp are most frequently observed (16, 18, 27, 29, 30). Here, we analyzed whether telomerase can elongate DNA oligonucleotide sequences derived from natural chromosome breakpoints. The following break site sequences were used: PfTS-VIII from the histidine rich protein I (HRPI) gene (27), PfTS-IX from the histidine rich protein II (HRPII) gene (30), and PfTS-X from the Pf11-1 gene (29) (Table 1). All three oligonucleotides are elongated in the standard Pf-TRAP assay with an efficiency comparable to that of the control primer PfTS-I (Fig. 4A). These results demonstrate that the P. falciparum telomerase can use a variety of DNA sequences as a substrate if the 3′ end carries a few bases homologous to a plasmodial telomere repeat.

FIG. 4.

Telomerase activity with nontelomeric primers and oligonucleotides based on naturally occurring healed P. falciparum chromosome break sites. (A) Pf-TRAP assay with different substrates. The nontelomeric primers PfTS-IV and PfTS-VI are elongated with very low efficiency compared to primers PfTS-V and PfTS-VII, which carry a telomeric sequence motif GGTTCA (shown underlined) positioned upstream to the nontelomeric 3′ end. Chromosome breakpoint sequences which have been healed by the addition of telomere repeats in vivo (16, 29, 30) efficiently recruit plasmodial telomerase in vitro. (B) DNA sequence analysis of one Pf-TRAP elongation product on input primers PfTS-V and PfTS-VII. Note the extreme degeneracy of the telomere repeats added to the -CCC 3′ terminus of PfTS-V.

Previous work demonstrated that P. falciparum chromosome break sites with no evident similarity to 3′ ends have been healed in vivo by the addition of telomere repeats (18). In order to study the potential implication of plasmodial telomerase in the elongation of nontelomeric 3′ ends, oligonucleotide primers that carry either -CCC or -AAAA at the 3′ termini (Table 1) were examined. These nontelomeric primers (PfTS-IV and PfTS-VI) did not efficiently recruit telomerase in the Pf-TRAP assay (Fig. 4A). Upstream telomere repeat motifs have been previously shown to enhance telomere elongation of nontelomeric 3′ ends by human, Euplotes, and Tetrahymena telomerases (12, 22, 23). When a telomeric repeat motif was positioned upstream to the poly(C)/poly(A) tract, the assay yielded Pf-TRAP ladder intensities comparable to those of the telomeric primer PfTS-I (Fig. 4A). Cloning and DNA sequence analysis of the elongation products of primers PfTS-V and PfTS-VII revealed several important features of P. falciparum telomerase (Fig. 4B). First, nontelomeric primers can serve directly as substrates for the addition of new telomere repeats without endonucleolytic modification of the 3′ terminus. Second, elongation of the different nontelomeric primers PfTS-V and PfTS-VII is initiated with the same sequence motif -GGGTT. Third, the synthesis of new telomere repeats onto the poly(C) tract is significantly less precise than on telomeric or poly(A) substrate ends (Fig. 3B and 4B). Two independent clones of telomerase elongated PfTS-V have been sequenced, and each clone shows a distinct pattern of highly degenerated G-rich repeats (data not shown).

De novo telomere repeat synthesis in vitro.

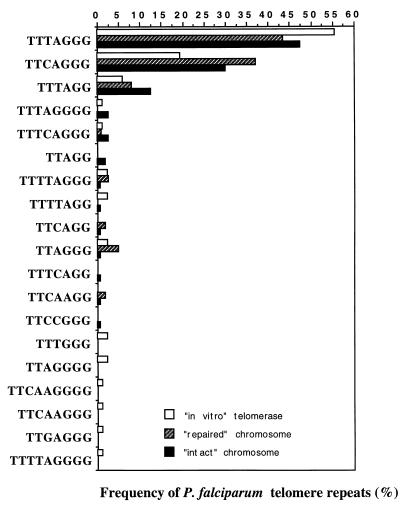

P. falciparum telomeres are composed of a mixture of G-rich heptanucleotide repeats. GGGTTTA and GGGTTCA are the most frequently found (approximately 80%); however, a number of degenerated repeats are interspersed in these motifs (Fig. 5). A comparable frequency of repeats has also been shown to exist on healed chromosome ends (28). DNA sequence analysis of in vitro-synthesized telomere repeats on various primers yielded a similar overall distribution of the two main repeats (Fig. 5). Surprisingly, several types of G-rich repeats synthesized de novo by the Pf-TRAP assay have been detected neither on intact nor on repaired chromosome ends. This result suggests that P. falciparum telomerase activity monitored in vitro might display reduced precision of initial telomere repeat synthesis due to low anchoring forces of the single-stranded primer to the enzyme protein subunit. Alternatively, a telomerase component important for the precision of the telomerase might be absent in the cytoplasmic cell extract.

FIG. 5.

Comparison of motif frequencies in the sequences of P. falciparum telomere repeats generated by telomerase activity in vitro (this work) and on healed (18, 29, 30) and intact (35) chromosome ends. In all cases, comparable motifs of the two main repeats GGGTTT/CA are found with similar frequencies. These results support the idea that the in vitro telomerase reaction reflects de novo telomeric addition in vivo. It is noteworthy that some degenerated repeats are found only in the in vitro telomerase products.

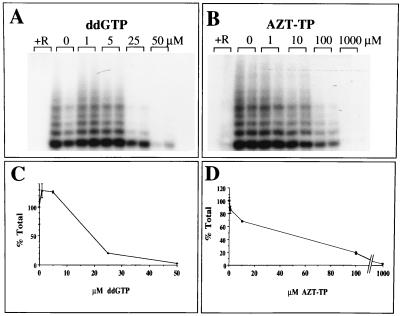

Inhibition of in vitro P. falciparum telomerase activity by chain-terminating nucleoside triphosphate analogs.

Human and Tetrahymena telomerase activities have been shown to be sensitive to reverse transcriptase inhibitors (32, 33). Given that Plasmodium telomerase shares many features with telomerases of other organisms, the abilities of known reverse transcriptase inhibitors such as AZT-TP or ddGTP to inhibit the Pf-TRAP assay were measured. Increasing amounts of AZT-TP and ddGTP were added to the Pf-TRAP assay mix primed with oligonucleotide PfTS-I. Both nucleoside analogs decreased Pf-TRAP product intensities in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 6A and B). Quantification of Pf-TRAP elongation products from duplicate reactions with a PhosphorImager showed that ddGTP is a more potent inhibitor than AZT-TP. Approximately 50% inhibition of the plasmodial telomerase activity is achieved at concentrations of approximately 20 μM ddGTP, whereas approximately two to three times higher AZT-TP concentrations were necessary to obtain comparable inhibition in the presence of 50 μM deoxynucleoside triphosphate (dNTP) (Fig. 6C and D). A similar degree of inhibition has been reported recently for the human telomerase by a comparable assay (33). The observed inhibition of plasmodial telomerase is presumably due to chain termination, but these experiments do not rule out the possibility that the inhibition is due to competition with dNTPs without analog incorporation into the product.

FIG. 6.

Effects of triphosphate analogs on P. falciparum telomerase activity in vitro. PAGE on 15% polyacrylamide gels showing duplicate reaction products of Pf-TRAP telomerase assays was performed with increasing concentrations of ddGTP (A) and AZT-TP (B). The indicated concentrations of ddGTP and AZT-TP were added to the telomerase reaction mixtures. RNase A (lanes +R) was added to the Pf-TRAP assay and used as a control for nontelomerase-mediated incorporation of 32P label. (C and D) Quantification of a central region of the gels with a PhosphorImager. The mean values of the corresponding duplicate lanes are shown.

DISCUSSION

Malaria parasites carry G-rich tandem repeats at their chromosome ends; thus, it has been assumed that these parasites have chromosome maintenance machinery similar to that of ciliated protozoa and higher eucaryotes (28). The recently developed PCR-based telomerase assay (15) has enabled us for the first time to identify telomerase activity in this human pathogen. Our results show that P. falciparum telomerase shares a number of features with telomerases of evolutionary distinct organisms: the de novo addition of species-specific telomere repeats onto the 3′ terminus of G-rich single-stranded DNA and the sensitivity of the enzymatic activity to treatment with RNase A. Characterization of the enzymatic properties in vitro suggests that de novo telomere addition follows two pathways. First, 3′ ends which can form a few base pairs with the putative plasmodial RNA template are elongated by the addition of the next base in the telomere repeat. This observation is fully in agreement with the telomerase elongation-translocation model established based on data obtained with Tetrahymena telomerase (7). Second, 3′ termini with no apparent sequence complementary to the RNA template acquire new telomere repeats starting invariably with GGGTT. The efficiency of repeat addition to nontelomeric sequences depends essentially on the presence of G-rich motifs in the primer sequence. This suggests that the internal telomeric sequence attaches the 3′ terminus of the oligonucleotide close to the active site of the RNA template. In this case, extension by telomerase might occur via a default mechanism which initially adds the same sequence to a nontelomeric 3′ end. A default mechanism of de novo telomere formation to nontelomeric sequences has been extensively documented for the Euplotes and Tetrahymena enzyme (22, 36) and suggests that this mechanism might be a general enzymatic property of telomerase. However, a recent report demonstrated that de novo telomere formation, at least in Euplotes, is mediated by a transacting factor (1a). Therefore, we cannot exclude that in P. falciparum the formation of a new telomere is developmentally regulated during the complex life cycle.

How do the in vitro P. falciparum telomerase data relate to findings observed in the malaria parasite? The mean lengths of telomeres on P. falciparum chromosomes appear to be constant during the highly replicative blood stage phase (2a). Thus, it is likely that telomerase compensates for telomere shortening by the addition of new telomere repeats to chromosome ends. Molecular characterization of a number of chromosome breakpoints which had been repaired by the addition of new telomere repeats revealed preferential healing of ends that can form base pairing with the putative RNA template (18). Our in vitro telomerase data obtained with various substrates clearly indicate a role for this enzyme in the healing process of truncated chromosomes. Three different primers derived from natural break sites within different genes were very efficient telomerase substrates in the Pf-TRAP assay. In almost all cases studied, plasmodial chromosome breaks have been observed in coding regions and they either terminate with telomere-like motifs at the 3′ end or have a G-rich sequences nearby. Noncoding regions of P. falciparum genomic DNA are generally extremely AT rich (>80%) and, thus, are probably not efficiently used by telomerase. This observation correlates with the in vitro finding that a primer ending in poly(A) in the absence of G-rich internal sequences was barely elongated by telomerase. In conclusion, the telomerase data gained from in vitro studies generally correlate well with the biological data obtained from Plasmodium parasites. However, the precision of telomere repeat synthesis by telomerase in vitro seems to be altered (Fig. 5). This observation could be explained by the use of short oligonucleotide primers in the Pf-TRAP assay which might have a looser association with the ribonucleoprotein complex compared to natural chromosome ends. Unlike in vitro telomere synthesis, the addition of telomere repeats to truncated chromosomes has a normal frequency of variable telomere repeats at the break site. Precision of de novo synthesis might improve once a critical number of repeats has been added to the input primer. Thus, it is possible that the altered in vitro precision described in Fig. 5 is biased by the fact that only telomerase elongation products with relatively few repeats (7 to 16 repeats) have been cloned and sequenced. It will be interesting to study whether telomerase activity is regulated in the P. falciparum life cycle, which consists of different phases of highly replicative activities and long phases of cell differentiation in which several days can pass without apparent cell division.

One of the most intriguing aspects of the plasmodial telomerase is the variant repeat sequences that are synthesized in vitro and in vivo. Telomeric DNA of the mouse malaria parasite Plasmodium berghei consists of a random mixture of the two type of repeats GGGTTT/CA, whereas the telomere repeats of P. falciparum are composed mainly of GGGTTT/CA repeats (<80%) and at a lower frequency of degenerated telomere repeats (Fig. 5). The underlying mechanism of variable repeat synthesis remains unknown, since the sequence and number of the telomerase RNA genes of P. falciparum are not yet known. Thus, molecular cloning of the plasmodial telomerase components will be crucial to analyze functional aspects. Telomere repeat organization of Paramecium species resembles more closely the Plasmodium situation, where one telomerase RNA can give rise to primarily one repeat and another one to two different repeats probably by stuttering (19, 20). Transfection of malaria parasites with mutated telomerase RNA template would also allow functional in vivo studies on Plasmodium telomeres.

Previous work has shown that mutations that lead to loss of telomeric DNA in different single-cell organisms induce a cell senescence phenotype (17, 21, 31, 39), and in certain mammalian cells, telomere shrinkage has been correlated with cellular senescence (10). Malaria parasites are haploid unicellular protozoa whose rapid growth should be dependent on complete chromosome replication in order to avoid fatal chromosome shortening and to ensure immortalization. P. falciparum alternates between two hosts during its complex life cycle, the mosquito vector Anopheles and humans. During this life cycle, the parasites run through different phases of intense mitotic division (schizogeny) within human hepatocytes and erythrocytes. For example, approximately 20,000 merozoites are released from a single infected hepatocyte. These merozoites invade erythrocytes and undergo multiple mitotic divisions (four to five) each 48 h before releasing 16 to 32 merozoites into the blood. This blood stage is responsible for the symptoms of the disease, and high parasite loads of 109 to 1010 infected erythrocytes are frequently observed in infected patients. Thus, it is tempting to speculate that parasite blood stage cell proliferation could be controlled at the level of chromosomal replication. A first step to test this hypothesis would be to identify efficient inhibitors of P. falciparum telomerase. The Pf-TRAP assay allows one to rapidly screen in vitro for potential telomerase inhibitors. In this work, we have identified two reverse transcriptase inhibitors (ddGTP and AZT-TP) which significantly inhibit plasmodial telomerase in vitro in a dose-dependent manner and at micromolar concentrations. The correlation between telomerase activity and unlimited cell proliferation in unicellular eucaryotes suggests that telomerase inhibitors might be valuable anti-malarial therapeutics. This possibility is under investigation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank L. Pereira da Silva for his support, T. de Lange and N. W. Kim for helpful discussions on the Pf-TRAP assay, S. Sarfati for the kind gift of AZT-TP, and C. Roth for critically reading the manuscript and helpful comments.

This work has been supported by a grant from the Commission of the European Communities for research and technical development (contract no. CT96-0071).

REFERENCES

- 1.Bakhsis, N., and A. Scherf. Unpublished data.

- 1a.Bednenko J, Melek M, Greene E C, Shippen D E. Developmentally regulated initiation of DNA synthesis by telomerase: evidence for factor-assisted de novo telomere formation. EMBO J. 1997;16:2507–2518. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.9.2507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blackburn E H. Telomeres: no end in sight. Cell. 1994;77:621–3. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90046-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2a.Bottius, E., and A. Scherf. Unpublished data.

- 3.Broccoli D, Young J W, de Lange T. Telomerase activity in normal and malignant hematopoietic cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:9082–9086. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.20.9082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dore E, Pace T, Ponzi M, Scotti R, Frontali C. Homologous telomeric sequences are present in different species of the genus Plasmodium. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1986;21:121–127. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(86)90015-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Greider C. Telomerase biochemistry and regulation. In: Blackburn E, Greider C, editors. Telomeres. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Press; 1995. pp. 35–68. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Greider C W, Blackburn E H. Identification of a specific telomere terminal transferase activity in Tetrahymena extracts. Cell. 1985;43:405–413. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90170-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Greider C W, Blackburn E H. The telomere terminal transferase of Tetrahymena is a ribonucleoprotein enzyme with two kinds of primer specificity. Cell. 1987;51:887–898. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90576-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Greider C W, Blackburn E H. A telomeric sequence in the RNA of Tetrahymena telomerase required for telomere repeat synthesis. Nature. 1989;337:331–337. doi: 10.1038/337331a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gysin J, Dubois P, Pereira da Silva L. Protective antibodies against erythrocytic stages of Plasmodium falciparum in experimental infection of the squirrel monkey, Saimiri sciureus. Parasite Immunol. 1982;4:421–430. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3024.1982.tb00453.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harley C. Telomeres and aging. In: Blackburn E, Greider C, editors. Telomeres. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1995. pp. 247–264. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harley C B, Futcher A B, Greider C W. Telomeres shorten during ageing of human fibroblasts. Nature. 1990;345:458–460. doi: 10.1038/345458a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harrington L, Greider C. Telomerase primer specificity and chromosome healing. Nature. 1991;353:451–453. doi: 10.1038/353451a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hastie N D, Dempster M, Dunlop M G, Thompson A M, Green D K, Allshire R C. Telomere reduction in human colorectal carcinoma and with ageing. Nature. 1990;346:866–868. doi: 10.1038/346866a0. . (Comments.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Henderson E. Telomere DNA structure. In: Blackburn E, Greider C, editors. Telomeres. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Press; 1995. pp. 11–34. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim N W, Piatyszek M A, Prowse K R, Harley C B, West M D, Ho P L, Coviello G M, Wright W E, Weinrich S L, Shay J W. Specific association of human telomerase activity with immortal cells and cancer. Science. 1994;266:2011–2015. doi: 10.1126/science.7605428. . (Comments.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lanzer M, Wertheimer S P, de Bruin D, Ravetch J V. Chromatin structure determines the sites of chromosome breakages in Plasmodium falciparum. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:3099–3103. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.15.3099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lundblad V, Szostak J W. A mutant with a defect in telomere elongation leads to senescence in yeast. Cell. 1989;57:633–643. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90132-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mattei D, Scherf A. Subtelomeric chromosome instability in Plasmodium falciparum: short telomere-like sequence motifs found frequently at healed chromosome breakpoints. Mutat Res. 1994;324:115–120. doi: 10.1016/0165-7992(94)90055-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McCormick-Graham M, Haynes W J, Romero D P. Variable telomeric repeat synthesis in Paramecium tetraurelia is consistent with misincorporation by telomerase. EMBO J. 1997;16:3233–3242. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.11.3233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McCormick-Graham M, Romero D P. A single telomerase RNA is sufficient for the synthesis of variable telomeric DNA repeats in ciliates of the genus Paramecium. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:1871–1879. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.4.1871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McEachern M J, Blackburn E H. Runaway telomere elongation caused by telomerase RNA gene mutations. Nature. 1995;376:403–409. doi: 10.1038/376403a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Melek M, Greene E C, Shippen D E. Processing of nontelomeric 3′ ends by telomerase: default template alignment and endonucleolytic cleavage. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:3437–3445. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.7.3437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morin G B. Recognition of a chromosome truncation site associated with alpha-thalassaemia by human telomerase. Nature. 1991;353:454–456. doi: 10.1038/353454a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nakamura T M, Morin G B, Chapman K B, Weinrich S L, Andrews W H, Lingner J, Harley C B, Cech T R. Telomerase catalytic subunit homologs from fission yeast and human. Science. 1997;277:955–959. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5328.955. . (Comments.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Olovnikov A M. A theory of marginotomy. The incomplete copying of template margin in enzymic synthesis of polynucleotides and biological significance of the phenomenon. J Theor Biol. 1973;41:181–190. doi: 10.1016/0022-5193(73)90198-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pasvol G, Wilson R J, Smalley M E, Brown J. Separation of viable schizont-infected red cells of Plasmodium falciparum from human blood. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1978;72:87–88. doi: 10.1080/00034983.1978.11719283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pologe L G, Ravetch J V. Large deletions result from breakage and healing of P. falciparum chromosomes. Cell. 1988;55:869–874. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90142-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Scherf A. Plasmodium telomeres and telomere proximal gene expression. Semin Cell Biol. 1996;7:49–57. [Google Scholar]

- 28a.Scherf, A. Unpublished data.

- 29.Scherf A, Carter R, Petersen C, Alano P, Nelson R, Aikawa M, Mattei D, Pereira da Silva L, Leech J. Gene inactivation of Pf11-1 of Plasmodium falciparum by chromosome breakage and healing: identification of a gametocyte-specific protein with a potential role in gametogenesis. EMBO J. 1992;11:2293–2301. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05288.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Scherf A, Mattei D. Cloning and characterization of chromosome breakpoints of Plasmodium falciparum: breakage and new telomere formation occurs frequently and randomly in subtelomeric genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:1491–1496. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.7.1491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Singer M S, Gottschling D E. TLC1: template RNA component of Saccharomyces cerevisiae telomerase. Science. 1994;266:404–409. doi: 10.1126/science.7545955. . (Comments.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Strahl C, Blackburn E H. The effects of nucleoside analogs on telomerase and telomerase in Tetrahymena. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:893–900. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.6.893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Strahl C, Blackburn E H. Effects of reverse transcriptase inhibitors on telomere length and telomerase activity in two immortalized human cell lines. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:53–65. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.1.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Trager W, Jensen J B. Human malaria parasites in continuous culture. Science. 1976;193:673–675. doi: 10.1126/science.781840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vernick K D, McCutchan T F. Sequence and structure of a Plasmodium falciparum telomere. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1988;28:85–94. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(88)90055-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang H, Blackburn E H. De novo telomere addition by Tetrahymena telomerase in vitro. EMBO J. 1997;16:866–879. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.4.866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Watson J D. Origin of concatemeric T7 DNA. Nature—New Biol. 1972;239:197–201. doi: 10.1038/newbio239197a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.World Health Organization. Global malaria control. WHO malaria unit. Bull W H O. 1993;71:281–284. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yu G L, Bradley J D, Attardi L D, Blackburn E H. In vivo alteration of telomere sequences and senescence caused by mutated Tetrahymena telomerase RNAs. Nature. 1990;344:126–132. doi: 10.1038/344126a0. . (Comments.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zakian V A. Telomeres: beginning to understand the end. Science. 1995;270:1601–1607. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5242.1601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]