Abstract

A stray cat, an intact female Japanese domestic shorthair cat of unknown age (suspected to be a young adult), was rescued. The cat was lethargic and thin and had marked skin fragility, delayed wound healing without skin hyperextensibility, and hind limb proprioceptive ataxia and paresis. Survey radiography, computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging revealed congenital vertebral anomalies, including thoracolumbar transitional vertebrae, scoliosis resulting from a thoracic lateral wedge-shaped vertebra, and a kinked tail, and a dilated spinal cord central canal. Through nutritional support, the cat’s general condition normalized, followed by a gradual and complete improvement of skin features. Whole-genome sequencing was completed; however, no pathogenic genetic variant was identified that could have caused this phenotype, including congenital scoliosis. A skin biopsy obtained 7 y after the rescue revealed no remarkable findings on histopathology or transmission electron microscopy. Based on clinical course and microscopic findings, malnutrition-induced reversible feline skin fragility syndrome (FSFS) was suspected, and nutritional support was considered to have improved the skin condition.

Key clinical message:

This is the second reported case of presumed malnutrition-induced reversible FSFS and was accompanied by long-term follow-up.

Résumé

Syndrome de fragilité cutanée réversible induit par la malnutrition soupçonné chez un chat avec des difformités axiales congénitales. Un chat errant, une femelle intacte de race japonaise à poil court et d’âge inconnu (suspecté être une jeune adulte), a été secourue. La chatte était léthargique et maigre, et avait une fragilité marquée de la peau, un retard dans la guérison de plaies sans hyperextensibilité de la peau, et une ataxie proprioceptive et parésie des membres postérieurs. Des radiographies, un examen par tomodensitométrie, et de l’imagerie par résonnance magnétique ont révélé des anomalies congénitales des vertèbres, incluant des vertèbres transitionnelles thoraco-lombaires, une scoliose résultant d’une vertèbre thoracique en forme de coin, une queue pliée, et un canal central de la moelle épinière dilaté. Grâce à un soutien nutritionnel, la condition générale du chat s’est stabilisée, suivi d’une amélioration graduelle et complète des caractéristiques de la peau. Le séquençage du génome complet a été effectué; toutefois, aucune variation génétique pathogénique n’a été identifiée qui aurait pu causer ce phénotype, incluant la scoliose congénitale. Une biopsie cutanée obtenue 7 j après le sauvetage n’a révélé aucune trouvaille spéciale à l’histopathologie ou par microscopie électronique à transmission. Basé sur le déroulement clinique et l’examen microscopique, le syndrome de fragilité cutanée réversible félin induit par la malnutrition (FSFS) était suspecté, et le soutien nutritionnel a été considéré comme ayant amélioré la condition cutanée.

Message clinique clé :

Ce cas est le deuxième cas rapporté de FSFS induit par la malnutrition soupçonné et a fait l’objet d’un suivi à long terme.

(Traduit par Dr Serge Messier)

Skin fragility is uncommon in cats (1); the skin may tear extensively and shed due to minimal trauma or handling for veterinary procedures. Differential diagnosis of skin fragility in cats is limited to a few uncommon or rare diseases, including feline skin fragility syndrome (FSFS; also known as acquired skin fragility) and Ehlers-Danlos syndromes (EDS; also known as feline cutaneous asthenia or dermatosparaxis) (1,2). Feline skin fragility syndrome has a multifactorial etiology (1,2). In contrast, EDS is a hereditary connective tissue disorder, and causative genetic variants have been reported in some cats (3,4). In humans, 14 subtypes of EDS have been recognized, and some have clinical signs such as skin fragility, easy bruising, kyphoscoliosis or scoliosis, or craniofacial features, with or without skin hyperextensibility (5).

Only a few cases of FSFS without an underlying disease have been reported (6,7). One FSFS case without concurrent diseases other than malnutrition was reported, with histopathological normalization of the skin after recovery (7).

This report presents a cat with skin fragility and congenital vertebral abnormalities, ultimately diagnosed as suspected acquired and reversible FSFS secondary to malnutrition. Long-term follow-up of the cat demonstrated improved clinical status with unremarkable histopathological and transmission electron microscopic findings.

Case description

A stray cat, an intact female Japanese domestic shorthair cat of unknown age (suspected to be a young adult), was rescued by veterinarians at a local veterinary clinic (Miyamoto Animal Hospital, Yamaguchi, Japan). At the time of rescue, the cat was lethargic and thin (weight: 1.4 kg, body condition score: 1 out of 5). Hematology and plasma chemistry revealed moderate anemia (PCV: 16.9%) and increased aspartate aminotransferase (138 IU/L, reference range: 18 to 51 IU/L). Other laboratory end points, including liver and renal panels and electrolytes, were unremarkable. Serological screening tests for feline leukemia virus antigen and feline immunodeficiency virus antibody were both negative. However, hind limb proprioceptive ataxia and paresis were observed.

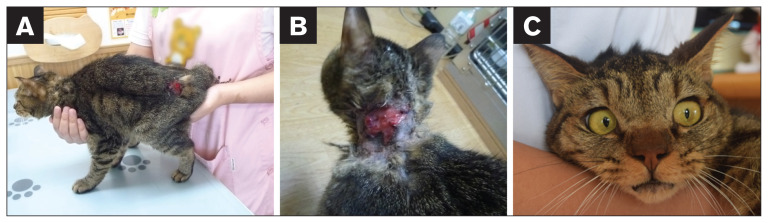

Radiographs indicated scoliosis of the thoracic vertebrae and thoracolumbar transitional vertebrae. Although the images had poor contrast of abdominal organs due to limited abdominal fat, no other abnormalities were apparent in thoracic or abdominal areas. While the cat was hospitalized, the skin was vulnerable and easily torn (Figure 1). Skin tears were closed using a medical stapler but sometimes tore again. The cat also had mild ocular hypertelorism (Figure 1). The cat’s short, kinked tail was also noted, although this phenotype is occasionally seen in Japanese domestic cats. Hyperextensibility of the skin and joint hypermobility were not observed. Palpation did not induce pain. Since this was a stray cat, pedigree information, history, and exact age were unavailable. The cat was maintained at the local veterinary clinic for ongoing care, including nutritional support.

Figure 1.

Appearance of the cat in this case. The skin was vulnerable and easily torn, as indicated by lesions at the rump (A) and neck (B). C — The cat also had mild ocular hypertelorism.

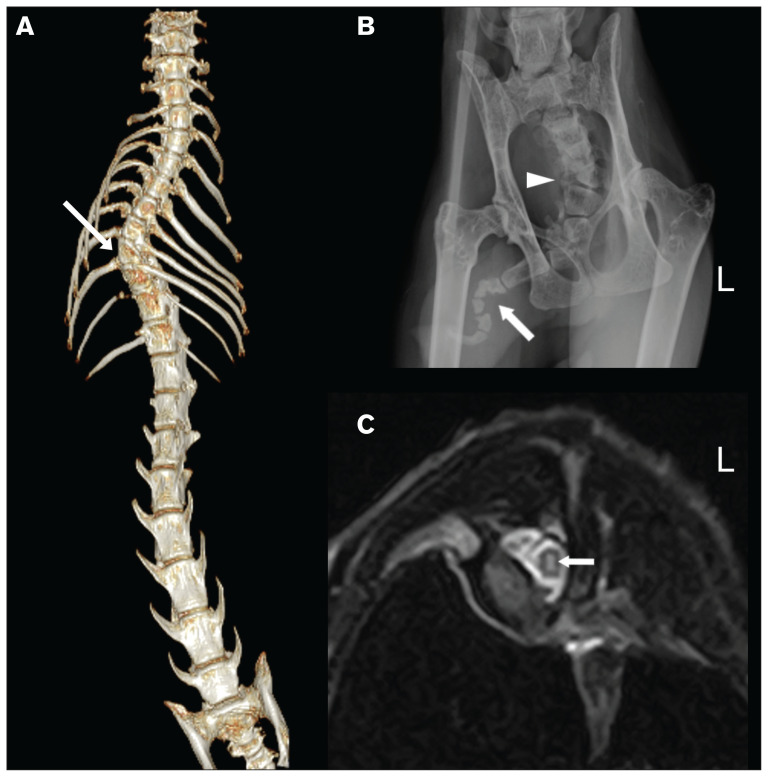

Two months after the rescue, detailed radiography, computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging were conducted under general anesthesia at a referral hospital (Yamaguchi University Animal Medical Center, Yamaguchi, Japan). Radiographs of the thorax, abdomen, skull, neck, thoracic limbs, and pelvic limbs were obtained. The abdominal organs had limited poor contrast due to minimal abdominal fat. Computed tomography imaging of the whole body was obtained with an 8-slice CT scanner (ECLOS 8; Hitachi Medical Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). Radiographs and CT imaging confirmed the 9th thoracic lateral wedge-shaped vertebra, causing scoliosis of the thoracic vertebrae and the thoracolumbar transitional vertebrae. The cat had 12 thoracic and 8 lumbar vertebrae, causing the thoracolumbar transitional vertebrae, whereas normal cats have 13 thoracic and 7 lumbar vertebrae. These abnormalities were well-visualized by CT 3-dimensional volume-rendering reconstruction (Figure 2). The short, kinked tail was also confirmed on radiographs and had abnormal-shaped coccygeal vertebrae that were outside the range of CT (Figure 2). Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain and spinal cord were obtained using a 0.4-T scanner (APERTO Inspire; Hitachi Medical Corporation), with sequences summarized in Appendix 1 (available online from: www.canadianveterinarians.net). No abnormalities were apparent in the brain parenchyma. Magnetic resonance imaging of the thoracic and lumbar spine revealed a longitudinal, T2-hyperintense lesion from T4 to T12 in the gray matter around the central canal of the spinal cord, whereas the longitudinal lesion had T1 iso- or hypointensity, implying a dilation of the central canal of the spinal cord (Figure 2) possibly associated with scoliosis. Hematology and plasma chemistry values were within normal limits.

Figure 2.

Imaging of the cat in this case. A — Ventral view of CT 3-dimensional volume rendering reconstruction of the thoracic and rostral lumbar spine of the cat. The arrow indicates a lateral wedge-shaped vertebra, causing scoliosis of the thoracic vertebrae. The numbers of thoracic and lumbar vertebrae are 12 and 8, respectively, causing thoracolumbar transitional vertebrae. B — Radiograph of the cat’s pelvic region. The arrow indicates a markedly kinked tail area where abnormally shaped coccygeal vertebrae are present. The arrowhead indicates the presence of coccygeal hemivertebrae. C — Transverse T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging at the level of C8 to C9, where scoliosis exists. A T2-hyperintense lesion is present in the middle of the spinal cord (arrow), suggesting dilation of the central canal of the spinal cord.

At this time, the differential diagnosis included EDS or FSFS because skin fragility is a well-known clinical sign of those disorders in cats (2). Most reported FSFS cases occurred concurrent with various diseases present in middle-aged or older cats (2). In contrast, the cat in this case had no underlying disease but presented with vertebral deformity, one of the comorbidities in human EDS (5). Therefore, the possibility of a rare type of EDS was considered, although hyperextensibility of the skin is a clinical feature of EDS in cats (2) that was not observed in this cat. Whole-genome sequencing (WGS) was completed to investigate the genetic variant(s) causing this phenotype in this cat. Histopathology was not available. Once the skin condition resolved, skin fragility was not observed, although caution was exercised during handling.

The WGS and subsequent data analysis were done as described in Appendix 1 (available online from: www.canadianveterinarians.net). Private homozygous and heterozygous genetic variants were filtered compared to data from 414 cats, including 362 cats with WGS and 52 cats with whole-exome sequencing data, for which the cat was privately homozygous; heterozygosity in up to 1 additional cat was permitted (see Tables S1, S2, S3, available online from: www.canadianveterinarians.net). In brief, a search for selected orthologous candidate genes (see Table S4, available online from: www.canadianveterinarians.net) in the data was conducted and included previously known causative genes of EDS, congenital scoliosis, or hereditary connective tissue disorders overlapping phenotype genes, based on literature for humans. A homozygous COL6A1 genetic variant (XM_011285711.3:c.1678_ 1680del), predicted to result in 1 amino acid residue deletion (XP_011284013.1:p.Asn560del), was identified uniquely in this cat, although a heterozygous variant was present in 1 other cat in the dataset. Furthermore, a heterozygous ZNF469 genetic variant (XM_023245050.1:c.4324G>A) was also detected as a unique variant to this case. No unique or (likely) pathogenic genetic variants were identified in any other candidate genes or known genes for the bobtailed or tailless phenotype in the Japanese bobtail (HES7) or in the Manx (T), respectively (8,9).

Upon follow-up at 7 y after the cat was rescued, body weight had increased to 3.9 kg, with no apparent progression of clinical signs, such as neurological deficits, although care was exercised to avoid trauma and skin tearing. A skin biopsy of the caudal cervical area was performed under general anesthesia to evaluate the skin, obtain a definitive diagnosis, and obtain skin samples for fibroblast cell culture and transcriptional analysis.

Reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction and Sanger sequencing were performed, and a homozygous COL6A1 genetic variant (c.1678_1680del) was confirmed to cause a 3-bp in-frame deletion in the COL6A1 transcript of the affected cat when compared to a normal cat. It was predicted to delete 1 amino acid residue (p.Asn560del; see Appendix 1 and Table S5, available online from: www.canadianveterinarians.net). Homozygous or compound heterozygous ZNF469 genetic variants cause brittle cornea syndrome, a subtype of EDS in humans, when homozygous; however, this is clinically characterized by thin and fragile corneas (5,10). Thus, the heterozygous ZNF469 genetic variant detected in this case was not further analyzed.

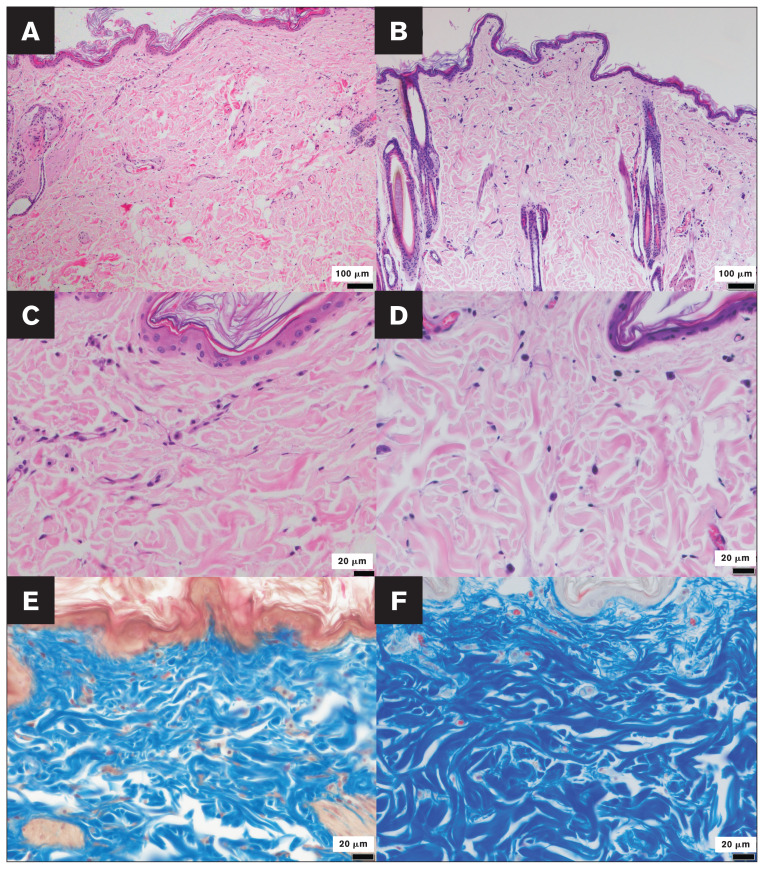

Findings from histopathological and transmission electron microscopic analyses, completed as described in Appendix 1 (available online from: www.canadianveterinarians.net), were unremarkable (Figures 3, 4). The biopsy wound-healing process was normal, along with prior evidence of skin fragility without skin hyperextensibility. This suggested a diagnosis of reversible FSFS, likely due to malnutrition before the rescue and similar to a previous single case (7), rather than a subtype of EDS seen in humans (5). Therefore, no further genetic analyses were done.

Figure 3.

Histologic sections of the affected cat’s cervical dorsal skin and those of a normal cat’s caudal cervical skin, for comparison. The control cat used for comparative histopathology of the skin was an intact female aged 8 y and 10 mo. A to D — Hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections of skin biopsy samples from the affected cat (A, C) and a control cat (B, D), with magnifications of 100× (A, B) and 400× (C, D), appear unremarkable. E and F — Masson’s trichrome staining of skin sections from the affected cat and a control cat, respectively (magnification: 400×). No abnormalities were apparent in histologic sections from the affected cat compared to those from a control cat. In panel E, note that the presence of larger space within the dermis is an artifact.

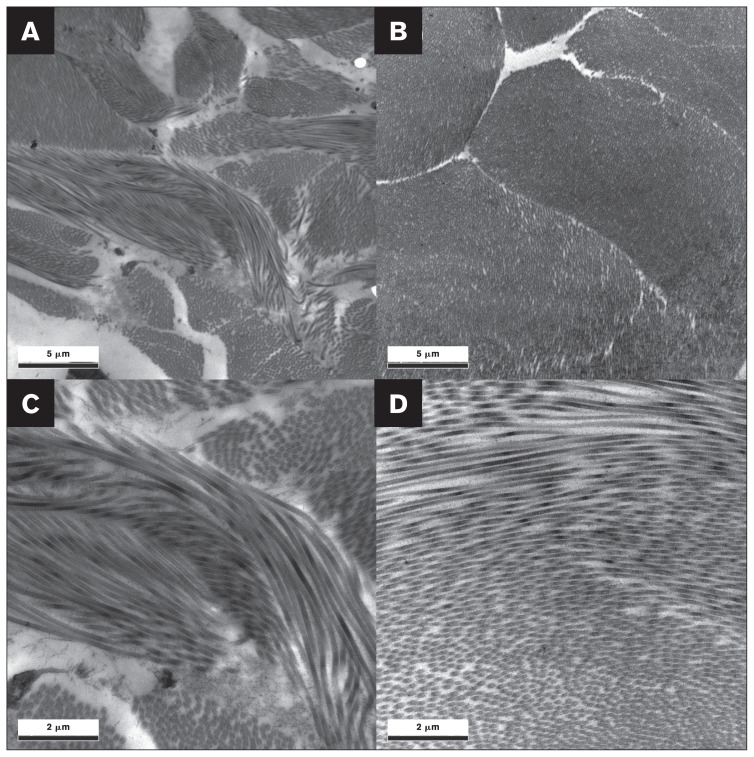

Figure 4.

Transmission electron micrographs of the affected cat’s cervical dorsal skin (A, C) and those of a normal cat’s caudal cervical skin (B, D), for comparison. The control cat used for comparative transmission electron micrographs of the skin was an intact female aged 8 y and 10 mo. Magnifications are 6000× (A, B) and 15 000× (C, D). Collagen fibrils are well-organized and have uniform diameters and circular profiles in both the affected cat and a control cat. No abnormalities were apparent in transmission electron micrographs from the affected cat compared to those from a control cat.

Discussion

This report describes a feline case characterized mainly by skin fragility, delayed wound healing, and congenital vertebral abnormalities. Although a rare subtype of EDS was initially suspected because of its unique phenotype, including skin fragility and vertebral deformity, the cat’s skin condition improved clinically, and histopathology of a skin biopsy sample 7 y after the rescue was normal. In contrast to our case, cats with EDS reportedly have abnormalities in Masson’s trichrome staining, with or without hematoxylin and eosin staining (6).

Unlike FSFS, the clinical hallmark of feline EDS is skin hyperextensibility and skin fragility recognized at a younger age (2). An accurate age and histopathology of the affected skin were not available in this case; however, because 7 y had passed, the cat was likely a young adult or juvenile at the time of the skin fragility and delayed wound healing. Epidermolysis bullosa is also a hereditary disease causing skin fragility in humans and animals; however, this disease was not considered likely as a differential diagnosis as skin sloughing is often limited to foot pads and integument lesions are unlikely in cats. Moreover, symptoms do not resolve (11).

There are various underlying causes of FSFS, including naturally occurring or iatrogenic hyperadrenocorticism, infectious diseases, neoplastic disease, non-neoplastic hepatopathies, hyperprogesteronism, cachexia, and a history of drug administration (1,2). However, only 1 reversible FSFS case has been reported that involved not a progressive disease condition but malnutrition (7). That case had histopathological normalization after 6 mo of recovery.

At the time of rescue, the cat in the current case had moderate anemia, likely due to starvation (12). Increased aspartate aminotransferase may have been caused by muscle wasting or hemolysis, although creatine kinase was not measured to support this possibility.

The body condition score was 1 out of 5 when the cat was rescued, and abdominal radiography had poor contrast of organs due to limited fat. Since a worsening of clinical signs and symptoms was not observed during the 7-year follow-up, and the cat had FSFS without underlying diseases, we suspect the FSFS was caused by malnutrition.

Interestingly, protein deficiency was suggested to affect synthesis and degradation of Types-I and -III collagen in rats (13). Although histopathology was not available when the skin fragility was present in our case, histopathology of the only previous case reported as suspected malnutrition-induced FSFS showed an atrophic dermis and the Masson’s trichrome abnormality (7). Furthermore, a low-protein diet was reported to induce thinning of the skin epidermis, decrease cell proliferative activity in epidermal cells, and decrease stratum corneum hydration in mice (14). Although epidermal atrophy was not mentioned in the only case report to-date on suspected malnutrition-induced FSFS (7), epidermal atrophy is another histological sign in FSFS (15,16). Lack of protein intake might also contribute to malnutrition-induced FSFS.

The cat in this case had congenital vertebral abnormalities, and magnetic resonance imaging revealed dilation of the central canal of the spinal cord (Figure 2). Although it remains inconclusive whether this was secondary to scoliosis or congenital and independent of scoliosis, syringomyelia is the second-most common anomaly in human patients with congenital scoliosis (17). Hind limb proprioceptive ataxia and paresis was likely caused by scoliosis and a dilated spinal cord central canal.

An HES7 genetic variant (c.5A>G; p.Val2Ala) reportedly causes a kinked-tail phenotype in Japanese bobtail cats (8). Japanese bobtail cats are also known to have variations in the normal feline vertebral formula (including transitional vertebra and abnormal vertebral formula), similar to the cat in our case (18). However, the HES7 genetic variant was not detected in this case, even though the cat was a Japanese domestic cat, suggesting that other factors were involved in the phenotype.

Unique genetic variants in protein-coding regions detected by WGS included homozygous COL6A1 genetic variant (c.1678_1680del; p.Asn560del), although 1 heterozygous variant was detected in 1 of 414 cats. Interestingly, a human patient with severe scoliosis and congenital vertebral deformity alone was reportedly diagnosed histopathologically with collagen VI-related myopathy, which had a heterozygous missense COLA6A2 genetic variant and 2 splicing variants in COL6A1 and COL6A2 (19). Both COL6A1 and COL6A2 encode a collagen alpha-1 (VI) chain and collagen alpha-2 (VI) chain, respectively, which partially composes collagen VI. Although the presence of the COL6A1 genetic variant might have been involved in the congenital vertebral deformity in our case, including scoliosis, the COL6A1 genetic variant currently has uncertain significance.

This report has some limitations. First, histopathological and transmission electron microscopic analyses for the skin biopsy sample were conducted 7 y after the rescue, when the cat appeared healthy. Although those analyses were not available when skin fragility was observed, skin fragility without skin hyperextensibility supported the FSFS diagnosis. Second, the cat was originally a stray, and medical information was available only after the rescue. Therefore, the possibility that some factors causing skin fragility were present cannot be completely excluded. In addition, the circumstances that led to the cat’s malnutrition are unknown, and the possibility that an underlying disease may have existed when it was rescued cannot be excluded. Finally, genetic variants present in regions other than the candidate genes we targeted may have influenced the phenotype of this case. This shortcoming also reflects the fact that this was a single case. Structural variants were also not evaluated. Nevertheless, the cat had skin fragility and delayed wound healing when rescued, and a favorable long-term outcome for 7 y was achieved through nutritional support, including a clinically and histopathologically normal skin condition.

In this report, we described a cat with FSFS presumably caused by malnutrition (only the second reported case supporting this connection) and accumulated evidence for 1 aspect of the etiology of FSFS. Further, a favorable long-term outcome with improved clinical status was achieved.

Acknowledgments

This study was partially supported by the MU Gilbreath McLorn Endowment for Comparative Medicine and EveryCat Health Foundation (formerly the Winn Feline Foundation) (L.A.L.). The authors thank the 99 Lives Cat Genome Consortium (felinegenetics.missouri.edu) for sharing domestic cat variant frequency information; its members are listed in Appendix 1 (available online from: www.canadianveterinarians.net). CVJ

Footnotes

Unpublished supplementary material (Appendix 1; Tables S1, S2, S3, S4, S5) is available online from: www.canadianveterinarians.net

Use of this article is limited to a single copy for personal study. Anyone interested in obtaining reprints should contact the CVMA office (kgray@cvma-acmv.org) for additional copies or permission to use this material elsewhere.

References

- 1.Englar RE. Skin Fragility. In: Englar RE, editor. Common Clinical Presentations in Dogs and Cats. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons; 2019. pp. 125–133. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gross TL, Ihrke PJ, Walder EJ, Affolter VK, editors. Skin Diseases of the Dog and Cat. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Science; 2005. Degenerative, Dysplastic and Depositional Diseases of Dermal Connective Tissue; pp. 373–403. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spycher M, Bauer A, Jagannathan V, Frizzi M, De Lucia M, Leeb T. A frameshift variant in the COL5A1 gene in a cat with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. Anim Genet. 2018;9:641–644. doi: 10.1111/age.12727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kiener S, Apostolopoulos N, Schissler J, et al. Independent COL5A1 variants in cats with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. Genes. 2022;13:797. doi: 10.3390/genes13050797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Malfait F, Castori M, Francomano CA, Giunta C, Kosho T, Byers PH. The Ehlers–Danlos syndromes. Nat Rev Dis Primer. 2020;6:64. doi: 10.1038/s41572-020-0194-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fernandez CJ, Scott DW, Erb HN, Minor RR. Staining abnormalities of dermal collagen in cats with cutaneous asthenia or acquired skin fragility as demonstrated with Masson’s trichrome stain. Vet Dermatol. 1998;9:49–54. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3164.1998.00074.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Furiani N, Porcellato I, Brachelente C. Reversible and cachexia-associated feline skin fragility syndrome in three cats. Vet Dermatol. 2017;28:508–e121. doi: 10.1111/vde.12457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lyons LA, Creighton EK, Alhaddad H, et al. Whole genome sequencing in cats, identifies new models for blindness in AIPL1 and somite segmentation in HES7. BMC Genomics. 2016;17:265. doi: 10.1186/s12864-016-2595-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buckingham KJ, McMillin MJ, Brassil MM, et al. Multiple mutant T alleles cause haploinsufficiency of brachyury and short tails in Manx cats. Mamm Genome. 2013;24:400–408. doi: 10.1007/s00335-013-9471-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rohrbach M, Spencer HL, Porter LF, et al. ZNF469 frequently mutated in the brittle cornea syndrome (BCS) is a single exon gene possibly regulating the expression of several extracellular matrix components. Mol Genet Metab. 2013;109:289–295. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2013.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Medeiros GX, Riet-Correa F. Epidermolysis bullosa in animals: A review. Vet Dermatol. 2015;26:3–13. doi: 10.1111/vde.12176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weiss DJ. Aplastic anemia in cats: Clinicopathological features and associated disease conditions 1996–2004. J Feline Med Surg. 2006;8:203–206. doi: 10.1016/j.jfms.2005.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oishi Y, Fu Z, Ohnuki Y, Kato H, Noguchi T. Effects of protein deprivation on α1(I) and α1(III) collagen and its degrading system in rat skin. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2002;66:117–126. doi: 10.1271/bbb.66.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sugiyama A, Fujita Y, Kobayashi T, et al. Effect of protein malnutrition on the skin epidermis of hairless mice. J Vet Med Sci. 2011;73:831–835. doi: 10.1292/jvms.10-0399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McKnight CN, Lew LJ, Gamble DA. Management and closure of multiple large cutaneous lesions in a juvenile cat with severe acquired skin fragility syndrome secondary to iatrogenic hyperadrenocorticism. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2018;52:210–214. doi: 10.2460/javma.252.2.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tamulevicus AM, Harkin K, Janardhan K, Debey BM. Disseminated histoplasmosis accompanied by cutaneous fragility in a cat. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 2011;47:e36–e41. doi: 10.5326/JAAHA-MS-5517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ghandhari H, Tari HV, Ameri E, Safari MB, Fouladi DF. Vertebral, rib, and intraspinal anomalies in congenital scoliosis: A study on 202 Caucasians. Eur Spine J. 2015;24:1510–1521. doi: 10.1007/s00586-015-3833-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pollard RE, Koehne AL, Peterson CB, Lyons LA. Japanese bobtail: Vertebral morphology and genetic characterization of an established cat breed. J Feline Med Surg. 2015;17:719–726. doi: 10.1177/1098612X14558147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li JY, Liu SZ, Zheng DF, Zhang YS, Yu M. Collagen VI-related myopathy with scoliosis alone: A case report and literature review. World J Clin Cases. 2021;9:5302–5312. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i19.5302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]