Abstract

Objective

To describe the findings, treatment, and outcome of small intestinal volvulus (SIV) in 47 cows.

Animals and procedure

Retrospective analysis of medical records. Comparison of the findings for 18 surviving and 29 non-surviving cows.

Results

The most common abnormal vital signs were tachycardia (68.0%), tachypnea (59.6%), and decreased rectal temperature (51.1%). Signs of colic occurred in 66.0% of cows in the study. Rumen motility was reduced or absent in 93.6% of cows, and intestinal motility in 76.6%. Clinical signs on ballottement and/or percussion and simultaneous auscultation were positive on the right side in 78.7% of cows. Transrectal examination showed dilated small intestines in 48.9% of cows. The rectum contained little or no feces in 93.6% of cows. The principal laboratory abnormalities were hypocalcemia (74.1%), hypokalemia (73.8%), azotemia (62.8%), hypermagnesemia (61.6%), and hemoconcentration (60.0%). The principal ultrasonographic findings were dilated small intestines (87.1%) and reduced or absent small intestinal motility (85.2%). Forty-one of the 47 cows underwent right flank laparotomy and the SIV was reduced in 21 cows. When comparing the clinical and laboratory findings of 18 surviving and 29 non-surviving cows, the groups differed significantly with respect to severely abnormal general condition (16.7 versus 37.9%), rumen stasis (22.2 versus 79.3%), intestinal atony (16.7 versus 48.3%), serum urea concentration (6.5 versus 9.8 mmol/L), and serum magnesium concentration (0.98 versus 1.30 mmol/L). In summary, 38.3% of the cows were discharged and 61.7% were euthanized before, during, or after surgery.

Conclusion and clinical relevance

An acute course of disease, little or no feces in the rectum, and dilated small intestines were characteristic of SIV in this study population.

Résumé

Volvulus de l’intestin grêle chez 47 vaches

Objectif

Décrire les données, le traitement et les résultats du volvulus de l’intestin grêle (SIV) chez 47 vaches.

Animaux et procédure

Analyse rétrospective des dossiers médicaux. Comparaison des résultats pour 18 vaches survivantes et 29 vaches non survivantes.

Résultats

Les signes vitaux anormaux les plus courants étaient la tachycardie (68,0 %), la tachypnée (59,6 %) et la diminution de la température rectale (51,1 %). Des signes de coliques sont apparus chez 66,0 % des vaches étudiées. La motilité du rumen était réduite ou absente chez 93,6 % des vaches et la motilité intestinale chez 76,6 %. Les signes cliniques de ballottement et/ou percussion et auscultation simultanée étaient positifs du côté droit chez 78,7 % des vaches. L’examen transrectal a montré une dilatation de l’intestin grêle chez 48,9 % des vaches. Le rectum contenait peu ou pas de matières fécales chez 93,6 % des vaches. Les principales anomalies des analyses de laboratoire étaient l’hypocalcémie (74,1 %), l’hypokaliémie (73,8 %), l’azotémie (62,8 %), l’hypermagnésémie (61,6 %) et l’hémoconcentration (60,0 %). Les principaux résultats échographiques étaient une dilatation de l’intestin grêle (87,1 %) et une motilité intestinale réduite ou absente (85,2 %). Quarante et une des 47 vaches ont subi une laparotomie du flanc droit et le SIV a été corrigé chez 21 vaches. En comparant les résultats cliniques et biologiques de 18 vaches survivantes et de 29 vaches non survivantes, les groupes différaient significativement en ce qui concerne l’état général sévèrement anormal (16,7 contre 37,9 %), la stase du rumen (22,2 contre 79,3 %), l’atonie intestinale (16,7 contre 48,3 %), la concentration sérique d’urée (6,5 contre 9,8 mmol/L) et la concentration sérique de magnésium (0,98 contre 1,30 mmol/L). En résumé, 38,3 % des vaches ont reçu leur congé et 61,7 % ont été euthanasiées avant, pendant ou après l’intervention chirurgicale.

Conclusion et pertinence clinique

Une évolution aiguë de la maladie, peu ou pas de selles dans le rectum et un intestin grêle dilaté étaient caractéristiques du SIV dans cette population étudiée.

(Traduit par Dr Serge Messier)

Introduction

Twisting of the small intestine can occur either as small intestinal volvulus (SIV) or mesenteric torsion (1–5). Volvulus of the sigmoid flexure of the duodenum is another intestinal disorder but was not considered in the present study (6,7). Small intestinal volvulus describes simple or multiple rotation(s) of a small intestinal segment around its mesenteric axis (1,4,5,8,9). The cecum and spiral colon may also be involved in the torsion (1). Mesenteric torsion is the most serious form of small intestinal rotation and involves twisting of the entire small intestinal tract and the spiral colon, including the relevant mesenteries around the mesenteric root. Small intestinal volvulus preferentially affects the caudal jejunum and the ileum because the associated mesentery is longer and thus, the intestinal section is more mobile compared with the cranial part of the jejunum (1). Furthermore, the caudal part of the jejunum is often located outside of the omental bursa, which favors twisting of this portion (10). Small intestinal volvulus has been described in textbooks (8,9,11,12) and various publications (4,5,13). In an older report, volvulus of the distal jejunum was diagnosed in 4 cows (10). Of 35 cattle with a tentative diagnosis of SIV, only 7 were definitively diagnosed with this disorder (1). Of 100 cattle suspected of having intestinal obstruction, only 4 had SIV (13); and of 27 cows with mechanical ileus, only 3 had SIV (14). To date, the most comprehensive study of SIV in cattle described 51 cases (3).

Early clinical signs of SIV are characterized by sudden colic (8,10). Dilated small intestines were palpated transrectally in 4 of 4 (10) and in 17 of 24 cows with SIV (1). In some of the cows, a taut band running dorsoventrally (1) or taut mesenteric tissue running from the left upper quadrant to the right (3) could be palpated. Congested intestinal loops were only evident in long-standing cases upon rectal examination (3). After the first 12 h, signs of colic begin to diminish with a concurrent deterioration in general condition (8). The rectum typically contains mainly thick mucus. The general condition continues to deteriorate; without treatment, affected cattle die 2 to 3 d later (8). Analogous to other forms of mechanical ileus, dilated small intestines with a diameter > 4 cm and reduced or absent intestinal motility are characteristic ultrasonographic findings for SIV (15). A tentative diagnosis of SIV is based on the history and clinical, transrectal, and ultrasonographic findings (14). In addition to the acuteness of the condition, a specific diagnosis of SIV is supported by dilated small intestines and tight bands palpated transrectally (3). The differential diagnosis should include other causes of ileus, such as mesenteric torsion and intestinal strangulation. A final diagnosis is often not possible without laparotomy 16) or postmortem examination. The only treatment option that offers a possibility of success is expeditious laparotomy and reduction of the volvulus (3,5). Severely compromised intestinal segments should be resected (4). Although SIV is discussed in most textbooks, only 1 study evaluated a large number of cattle with this condition (3). However, only 8 cattle were older than 6 mo and ultrasonography was not used. As the gastrointestinal tract differs fundamentally between adult cattle and calves, the goal of this study was to describe and analyze the clinical, laboratory, and ultrasonographic findings; treatment; and outcomes of 47 adult cattle with SIV.

Materials and methods

We analyzed the medical records of 47 cattle with SIV referred to the Department of Farm Animals, University of Zurich (Zurich, Switzerland), between January 1, 1986 and December 31, 2019. The present work is based on a dissertation (17).

Cattle and history

There were 41 cows and 6 heifers, all henceforth referred to as cows. These ranged in age from 1 to 13 y (median: 4.2 y). Numbers and breeds included 29 Brown Swiss, 13 Swiss Fleckvieh, 4 Holstein, and 1 crossbred cow. Fifteen cows were pregnant, 17 were open, and 15 did not have pregnancy status recorded in the medical history. The duration of pregnancy ranged from 4 to 38 wk (median: 12 wk). The last calving date was known in 20 cows and was between 1 and 25 wk (median: 10 wk) before admission. The duration of illness before admission ranged from 4 to 96 h (median: 12 h). Of 43 cows, 31 had anorexia and 12 had reduced feed intake. Signs of colic had occurred in 33 cows before admission.

Clinical examination

Each cow underwent a standard clinical examination (18–21). The general condition was evaluated by determining the demeanor, behavior, posture including recumbency, appetite, signs of abdominal pain, appearance of the hair coat and muzzle, skin elasticity, position of the eyes in the sockets, and skin surface temperature. General condition was classified as normal or mildly, moderately, or severely abnormal. Cows with a normal general condition were bright and alert and had normal behavior, posture, and appetite. The general condition was considered mildly abnormal when a mild decrease in alertness or mild signs of colic (defined below) were present. A moderate decrease in alertness and sometimes occasional grunting, or bruxism and marked signs of colic were observed in cattle with a moderately abnormal general condition. Cattle with a severely abnormal general condition showed marked apathy and were sometimes recumbent and unable to rise. The rumen was assessed for the degree of fill and the number and intensity of contractions. Tests for the presence of a foreign body included the pole test, back grip, and percussion of the abdominal wall over the region of the reticulum using a rubber hammer. Each test was carried out 4 times, and the reaction of the animal was observed each time. A test was considered positive when it elicited a short grunt at least 3 out of 4 times. Ballottement and simultaneous auscultation (BSA) and percussion and simultaneous auscultation (PSA) of the abdomen on both sides were also carried out. A BSA result was considered positive when splashing sounds were heard with a stethoscope while the abdominal wall was manually ballotted to produce a swinging motion. A PSA result was considered positive when a ringing sound or ping was heard on percussion of the abdominal wall with the handle of a hammer. Rectal examination was done in all cows. Feces were assessed for color, consistency, amount, fibre particle length, and any abnormal contents.

Each cow was observed for signs of pain (21,22). The number and severity of signs of colic/abdominal pain were determined. Signs of mild colic included mild restlessness, shifting of weight in the hind limbs, looking at the flank, lifting the tail, lifting of individual limbs, and tail swishing. Signs of moderate colic were moderate restlessness, brief periods of recumbency, kicking with the hind limbs, arching of the back, and marked tail swishing. Signs of severe colic were marked restlessness, frequent lying down and rising, sweating, grunting, and violent kicking at the abdomen. The cattle were divided into the colic, indolence (dullness), and intoxication phases. The colic phase was the initial phase accompanied by the described signs of pain. The indolence phase followed the colic phase and was characterized by apathy and a markedly abnormal general condition. In the last phase, intoxication, cattle had tachycardia, congested scleral blood vessels, pale mucous membranes, cool skin surface temperature, sunken eyes, and a dry muzzle.

Laboratory analyses

The collection and examination of blood, urine, and rumen fluid were done as described (20).

Ultrasonographic examination of the abdomen

In 31 cows, the abdomen was scanned from the right side as described (15).

Diagnosis

A tentative clinical diagnosis of ileus was made in cows with a history of colic or when signs of colic were recorded at the initial examination and the rectum contained little or no feces. A diagnosis of ileus was made when dilated small intestines and possibly tight bands were also palpated transrectally. A tentative diagnosis of ileus attributable to SIV was made in cows with grave transrectal findings that included congested, tubular small intestines and taut mesentery filling the abdominal cavity. An ultrasonographic diagnosis of ileus was made when dilated small intestines with a diameter ≥ 4.0 cm and no or subjectively decreased intestinal motility were observed. Involvement of the large intestine in SIV was suspected when gas- or fluid-filled sections of the large intestines were seen (23). The gold standard for diagnosis was based on laparotomy findings in cattle that underwent surgery and/or postmortem findings in cattle that were euthanized.

Laparotomy

A right-flank laparotomy was carried out in every cow. Before 2001, distal paravertebral anesthesia of the last thoracic and first 2 lumbar spinal nerves was done using lidocaine as described (24,25). Proximal paravertebral anesthesia of the same nerves was carried out starting in 2001. A vertical incision through all layers of the abdominal wall was made in the centre of the paralumbar fossa, starting 7 to 10 cm below the transverse processes and extending about 25 cm distally. After routine abdominal exploration, the small intestine was carefully examined to identify the site and extent of SIV. In cows with complete volvulus, reduction was attempted intra-abdominally, whereas in cows with segmental volvulus, reduction was attempted after the small intestine had been exteriorized on a Mayo table. After the surgical procedure, an antibiotic, most commonly amoxicillin, was infused into the abdomen in 1 L of isotonic saline solution or polyvinylpyrrolidone. The peritoneum, fascia, and transverse abdominal muscle and the internal and external oblique muscle layers were closed separately using a simple continuous suture pattern (Polysorb 2 USP atraumatic needle; Covidien-Medtronic, Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA). A continuous subcuticular suture (Polysorb 2.0 USP cutting needle; Covidien-Medtronic) and a modified mattress suture pattern was used to close the subcutaneous tissues, and metal clips (Appose, ULC 35W clips, 6.9 mm × 3.8 mm; Covidien-Medtronic) were used to close the skin.

Postoperative treatment

Cows that were discharged after a successful surgery were fasted for at least 24 h after surgery before feeding was gradually resumed. They received fluid therapy, antibiotics, analgesics, prokinetic drugs, and electrolyte replacement.

Euthanasia/slaughter

Cattle were euthanized using pentobarbital, or in earlier study years were sent to the slaughter facility of the veterinary hospital, during or after the initial examination when they were in the intoxication phase or when the owner did not consent to surgery (21). Cattle were euthanized intraoperatively when catastrophic lesions (e.g., ruptured intestines, fibrinous peritonitis, hemorrhagic infarction) were seen or complications (e.g., becoming recumbent on the right side during surgery with exteriorization and subsequent contamination of the intestines) occurred, or after surgery when the clinical condition deteriorated.

Postmortem examination

All cows that died or were euthanized underwent postmortem examination. For slaughtered cows, only the internal organs were inspected.

Statistics

The software SPSS Statistics 26.0 (IBM Corp, New York, New York, USA) was used for analysis. Frequencies were determined for all variables, and the Shapiro-Wilk test was used to test the data for normality. Means ± SD were calculated for normally distributed data and medians (with ranges) were calculated for non-normal data. In addition, the 95% CIs were calculated for the means and medians, respectively. Differences in non-normal data between surviving (from admission to hospital discharge) and non-surviving cows were analyzed using the Mann-Whitney U test, and differences in nominal data were analyzed using the X2 test. A value of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

General condition, abdominal contour, and signs of pain

The general condition was mildly abnormal in 23.4% (11/47) of the cows, moderately abnormal in 46.8% (22/47), and severely abnormal in 29.8% (14/47). One cow was recumbent upon initial examination and 3 others became recumbent during the examination. Twelve (25.5%) cows had uni- or bilateral abdominal distension.

Twelve of the 47 cows (25.5%) had nonspecific signs of pain, which included piloerection (5/47), bruxism (3/47), muscle fasciculations (2/47), and spontaneous grunting (2/47). Thirty-one cows (66.0%) were in the colic phase but the clinical signs were described in detail in only 24. These included restlessness (13/47), lordosis (12/47), treading (9/47), lying down and rising (6/47), kicking (6/47), and sweating (4/47). Of the cows with SIV, 23.4% (11/47) had 1 sign of visceral pain, 14.9% (7/47) had 2, 6.4% (3/47) had 3, and 6.4% (3/47) had 4 to 5 signs. These were assessed as mild (15/47), moderate (8/47), or severe (8/47). Fifteen (31.9%) cows were in the indolence phase (dullness phase) and 1 was in the intoxication phase. In addition, 53.2% (25/47) of cows had a tense abdominal wall (21/47) and/or an arched back (4/47).

Heart and respiratory rates and rectal temperatures (vital signs)

The most common vital sign abnormalities on initial examination were tachycardia (68.0%, 35/47), tachypnea (59.6%, 28/47), and lower-than-normal rectal temperature (51.1%, 24/47) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Clinical findings in cows with intestinal volvulus.

| Variable | Finding | Number of cattle | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heart rate (n = 47, median = 96 bpm, 95% CI = 88 to 104 bpm) |

Normal (60 to 80 bpm) | 13 | 27.7 |

| Decreased (54 bpm) | 2 | 4.3 | |

| Mildly increased (81 to 100 bpm) | 17 | 36.1 | |

| Moderately increased (101 to 120 bpm) | 9 | 19.1 | |

| Severely increased (121 to 160 bpm) | 6 | 12.8 | |

| Rectal temperature (n = 47, median = 38.4°C, 95% CI = 38.0 to 38.6°C) |

Normal (38.5 to 39.0°C) | 16 | 34.0 |

| Decreased (35.6 to 38.4°C) | 24 | 51.1 | |

| Increased (39.1 to 40.0°C) | 7 | 14.9 | |

| Respiratory rate (n = 47, median = 28 breaths/min, 95% CI = 24 to 32 breaths/min) |

Normal (15 to 25 breaths/min) | 16 | 34.0 |

| Decreased (8 to 14 breaths/min) | 3 | 6.4 | |

| Increased (26 to 80 breaths/min) | 28 | 59.6 | |

| Rumen motility (n = 47) |

Normal | 3 | 6.4 |

| Decreased | 17 | 36.2 | |

| Absent | 27 | 57.4 | |

| Foreign body tests (n = 41) |

All negative | 31 | 75.6 |

| At least one test positivea | 10 | 24.4 | |

| BSA and PSA on the left side (n = 47) |

Both tests negative (normal) | 44 | 93.7 |

| Only BSA positive | 1 | 2.1 | |

| Only PSA positive | 1 | 2.1 | |

| Both tests positive | 1 | 2.1 | |

| BSA and PSA on the right side (n = 47) |

Both tests negative (normal) | 10 | 21.3 |

| Only BSA positive | 21 | 44.7 | |

| Both tests positive | 16 | 34.0 | |

| Intestinal motility (n = 47) |

Normal | 11 | 23.4 |

| Decreased | 19 | 40.4 | |

| Absent | 17 | 36.2 | |

| Transrectal findingsb (n = 47) |

Normal findings | 18 | 38.3 |

| Rumen dilated | 13 | 27.7 | |

| Dilated loops of small intestines | 23 | 48.9 | |

| Colon and/or cecum dilated | 3 | 6.4 | |

| Findings inconclusive | 3 | 6.4 | |

| Feces, amount (n = 47) |

Normal | 3 | 6.4 |

| Fecal output reduced | 31 | 65.9 | |

| Rectum empty | 13 | 27.7 | |

| Feces, degree of comminution (n = 47) |

Normal (well-digested) | 26 | 55.3 |

| Moderately digested | 5 | 10.6 | |

| Poorly digested | 3 | 6.4 | |

| Rectum empty | 13 | 27.7 | |

| Feces, consistency (n = 47) |

Normal | 16 | 34.1 |

| Thick, pulpy | 9 | 19.1 | |

| Thin, pulpy | 4 | 8.5 | |

| Pasty | 4 | 8.5 | |

| Liquid | 1 | 2.1 | |

| Rectum empty | 13 | 27.7 | |

| Feces, color and abnormal contents in the rectum (n = 47) |

Normal (olive) | 21 | 44.7 |

| Dark | 9 | 19.1 | |

| Mucus | 9 | 19.1 | |

| Blood | 7 | 14.9 | |

| Fibrin | 1 | 2.1 | |

| Several abnormal contents | 5 | 10.6 |

BSA — Ballottement and simultaneous auscultation; PSA — Percussion and simultaneous auscultation.

Positive: At least 3 of 4 attempts elicited a grunt.

The total number of findings was 60 (127.7%) because 13 cattle had > 1 abnormal transrectal finding.

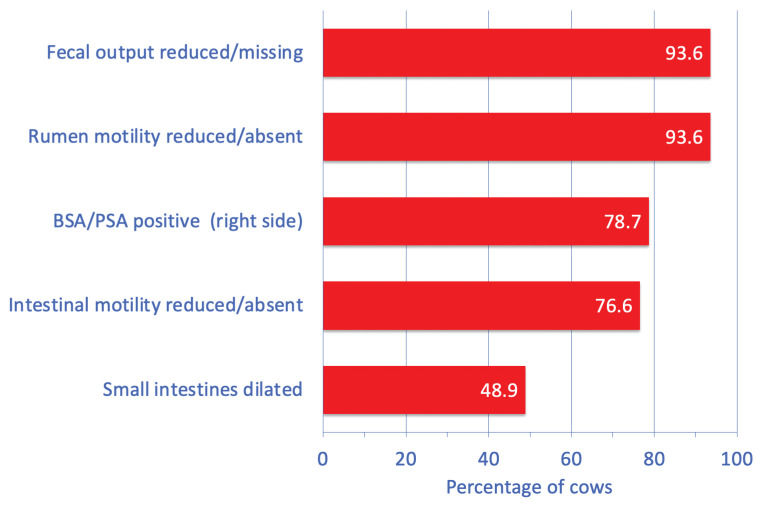

Digestive tract findings

The most common abnormal findings were minimal or no fecal material in the rectum (93.6%, 44/47), reduced or absent rumen motility (93.6%, 44/47), positive BSA and/or PSA on the right side (78.7%, 37/47), reduced or absent intestinal motility (76.6%, 36/47), and dilated small intestines palpated transrectally (48.9%, 23/47) (Figure 1; Table 1). At least 1 foreign body test was positive in 24.4% (10/41) of the cows, and 8.5% (4/47) of the cows had rumen tympany. A dilated rumen was diagnosed transrectally in 27.7% (13/47) of the cows. The feces were dark or black in 19.1% (9/47) of the cows, and the consistency ranged from liquid to pulpy (normal finding) to thick pulpy. Abnormal fecal contents included mucus, blood, and fibrin.

Figure 1.

The most common digestive tract abnormalities in 47 cows with small intestinal volvulus.

BSA — Ballottement and simultaneous auscultation; PSA — Percussion and simultaneous auscultation.

Other abnormal clinical findings

Other abnormal clinical findings included reduced skin elasticity (tenting of pinched skin lasted > 2 s) (67.4%, 31/46), reduced skin surface temperature (59.6%, 28/47), delayed capillary refill time (55.3%, 26/47), sunken eyes (51.1%, 24/47), moderately-to-severely hyperemic scleral vessels (45.7%, 21/46), a dry and cool muzzle (27.7%, 13/47), pale oral mucous membranes (19.1%, 9/47), and foul or ammonia-like breath (14.9%, 7/47).

Urinalysis

In 41 tested urine samples, pH ranged from 5.0 to 9.0 (median: 8.0); this was lower than normal (5.0 to 6.9) in 26.8% (11/41) and higher than normal (8.1 to 9.0) in 19.5% (8/41) of the cows. In 37 urine samples, specific gravity ranged from 1.003 to 1.058 (mean ± SD: 1.028 ± 14) and was decreased (< 1.020) in 27.0% (10/37) and increased (> 1.040) in 13.5% (5/37). Examination of 41 samples using Combur 9 test strips yielded hemoglobinuria/hematuria in 29.3% (n = 12), glucosuria in 26.8% (n = 11), ketonuria in 9.8% (n = 4) and proteinuria in 7.3% (n = 3) of the cows.

Laboratory findings

The principal abnormalities were hypocalcemia (74.1%, 20/27), hypokalemia (73.8%, 31/42), azotemia (62.8%, 27/43), hypermagnesemia (61.6%, 16/26), hemoconcentration (60.0%, 27/45), base excess (55.9%, 19/34), increased activity of aspartate aminotransferase (53.5%, 23/43), and acidosis (based on blood pH; 52.9%, 18/34) (Figure 2; Table 2).

Figure 2.

The most common abnormal blood variables in 47 cows with small intestinal volvulus.

Table 2.

Laboratory findings in cows with intestinal volvulus.

| Variable (mean ± SD, median, 95% CI) |

Finding | Number of cattle | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hematocrit (n = 45) (mean ± SD = 37.1 ± 6.7%, 95% CI = 35.1 to 39.1%) |

Decreased (17 to 29%) | 4 | 8.9 |

| Increased (36 to 52%) | 27 | 60.0 | |

| WBC count (n = 42) (median = 9850/μL, 95% CI = 8500 to 11 700/μL) |

Decreased (3600 to 4999/μL) | 3 | 7.1 |

| Increased (10 001 to 29 300/μL) | 20 | 47.6 | |

| Total protein (n = 44) (mean ± SD = 76.1 ± 12.4 g/L, 95% CI = 72.3 to 79.8 g/L) |

Decreased (48 to 59 g/L) | 4 | 9.1 |

| Increased (81 to 100 g/L) | 15 | 34.1 | |

| Fibrinogen (n = 42) (median = 4.5 g/L, 95% CI = 4.0 to 6.0 g/L) |

Decreased (1 to 3.9 g/L) | 10 | 23.8 |

| Increased (7.1 to 12 g/L) | 8 | 19.0 | |

| Urea (n = 43) (median = 7.1 mmol/L, 95% CI = 6.5 to 9.8 mmol/L) |

Increased (6.6 to 27.3 mmol/L) | 27 | 62.8 |

| Bilirubin (n = 43) (median = 4.0 μmol/L, 95% CI = 3.6 to 5.2 μmol/L) |

Increased (6.6 to 36.2 μmol/L) | 11 | 25.6 |

| Calcium (n = 27) (median = 2.03 mmol/L, 95% CI = 1.73 to 2.17 mmol/L) |

Decreased (1.24 to 2.29 mmol/L) | 20 | 74.1 |

| Increased (2.61 to 4.34 mmol/L) | 1 | 3.7 | |

| Magnesium (n = 26) (median = 1.16 mmol/L, 95% CI = 0.91 to 1.40 mmol/L) |

Decreased (0.73 to 0.79 mmol/L) | 1 | 3.8 |

| Increased (1.01 to 1.82 mmol/L) | 16 | 61.5 | |

| Inorganic phosphate (n = 27) (median = 1.60 mmol/L, 95% CI = 1.16 to 2.42 mmol/L) |

Decreased (0.39 to 1.29 mmol/L) | 9 | 33.3 |

| Increased (2.41 to 4.41 mmol/L) | 6 | 22.2 | |

| Chloride (n = 43) (median = 97 mmol/L, 95% CI = 93 to 100 mmol/L) |

Decreased (66 to 95 mmol/L) | 16 | 37.2 |

| Increased (106 to 125 mmol/L) | 9 | 20.9 | |

| Potassium (n = 42) (median = 3.30 mmol/L, 95% CI = 3.10 to 3.90 mmol/L) |

Decreased (2.5 to 3.9 mmol/L) | 31 | 73.8 |

| Increased (5.1 to 6.1 mmol/L) | 2 | 4.8 | |

| AST (n = 43) (median = 104 U/L, 95% CI = 89 to 114 U/L) |

Increased (104 to 5810 U/L) | 23 | 53.5 |

| γ-GT (n = 43) (median = 21.0 U/L, 95% CI = 17.0 to 24.0 U/L) |

Increased (31 to 262 U/L) | 5 | 11.6 |

| pH (n = 34) (median = 7.40, 95% CI = 7.36 to 7.43) |

Decreased (7.17 to 7.40) | 18 | 52.9 |

| Increased (7.41 to 7.50) | 4 | 11.8 | |

| pCO2 (n = 34) (median = 45.0 mmHg, 95% CI = 42.9 to 49.6 mmHg) |

Decreased (33.5 to 34.9 mmHg) | 2 | 5.9 |

| Increased (45.1 to 64.3 mmHg) | 17 | 50.0 | |

| Bicarbonate (n = 34) (mean ± SD = 26.6 ± 6.6 mmol/L, 95% CI = 24.3 to 28.9 mmol/L) |

Decreased (14.5 to 19.9 mmol/L) | 5 | 14.7 |

| Increased (30.1 to 43.1 mmol/L) | 8 | 23.5 | |

| Base excess (n = 34) (mean ± SD = 2.5 ± 6.9 mmol/L, 95% CI = 0.8 to 4.9 mmol/L) |

Decreased (−11.5 to −2.1 mmol/L) | 9 | 26.5 |

| Increased (2.1 to 18.0 mmol/L) | 19 | 55.9 | |

| Rumen chloride (n = 37) (median = 20.0 mmol/L, 95% CI = 17.0 to 24.0 mmol/L) |

Increased (31 to 63 mmol/L) | 9 | 24.3 |

Ultrasonographic findings

The principal ultrasonographic findings were dilated small intestines (87.1%, 27/31) with a diameter ranging from 4.0 to 10.0 cm, reduced or absent small intestinal motility (85.2%, 23/27), and free fluid in the abdomen (48.4%, 15/31). Subjectively, empty small intestines were seen in 7 cows and 1 cow had a dilated spiral colon. The actual site of the volvulus could not be visualized in any of the cows.

Comorbidities

Comorbidities unrelated to SIV were diagnosed in 34.0% (16/47) of the cows and included respiratory problems, ketonuria, gastrointestinal nematodes, dicrocoeliosis, and mastitis.

Diagnoses

Based on the clinical findings, a tentative diagnosis of ileus was made in 21.3% (10/47), a diagnosis of ileus was made in 55.3% (26/47), and a diagnosis of ileus attributable to SIV was made in 2.1% (1/47) of the cows. Based on the ultrasonographic examination of 32 cows, a diagnosis of ileus was made in 90.6% (29/32). Among those 29 cows, a diagnosis of ileus was also made clinically in 25 cows, whereas in the remaining 4, no clinical diagnosis was made.

Treatments and outcomes

Six cows died or were euthanized during or shortly after the initial examination (Figure 3), and 41 cows underwent right-flank laparotomy. Of those, 20 were euthanized intraoperatively; in the remaining 21, the surgery was completed. Of these latter, 3 died or were euthanized postoperatively and 18 were discharged. Thus, 61.7% (29/47) of the cows died spontaneously or were euthanized and 38.3% (18/47) were discharged.

Figure 3.

Treatment flowchart for 47 cows with small intestinal volvulus.

op. — Operation.

Surgical findings and complications

All cows that underwent surgery had a right-flank laparotomy; 34 cows were standing, 3 were sedated and recumbent, and 1 was under general anesthesia during surgery. Three other cows were standing at the start of surgery but became recumbent. All cows had SIV that was segmental in 9 cows and complete in 38 (these numbers include the 6 cows that did not undergo surgery, in which the diagnosis was confirmed during postmortem examination). In addition to the pathological changes seen in the small intestine in 97.6% (40/41) of cows, 2 cows also had lesions in the cecum identified as fibrin deposits on, and edema of, the cecal wall. The changes, which were not associated with the examination, were mild to moderate in 18/41 and severe in 13/41. Eleven of 41 cows had increased amounts of abdominal fluid. Seven cows had fibrin or fibrinous adhesions in the abdomen, 6 had tears in the mesentery or greater omentum, and 2 had a ruptured bowel. Of the 44.7% (21/47) of cows in which the surgery was completed, a segmental SIV was reduced in 9 and a complete SIV was reduced in 12. Two cows underwent additional intestinal resection, and in 5 others the cecum was evacuated. The remaining 42.6% (20/47) were euthanized during surgery because of severe intestinal lesions or because reduction of the volvulus was not possible. Intraoperative complications occurred in 7 cows; these manifested as recumbency with subsequent intestinal contamination in 2 cows, recumbency without contamination in 5 cows, spontaneous death in 1 cow, and bowel rupture in 1 other cow.

Postoperative treatments

All cows (18/18) that were discharged received 10 L of a solution containing 50 g glucose and 9 g sodium chloride/L, daily for 1 to 7 d (median: 3 d), administered as a slow IV drip via an indwelling jugular vein catheter. Antibiotic treatment was administered for 4 or 5 d and included penicillin G procaine (12 000 IU/kg) given IM (15/18), amoxicillin (7 mg/kg) given IM (1/8), and danofloxacin (1.2 mg/kg) given IV (1/18; a cow with a respiratory problem). With one exception, all cows (17/18) received flunixin meglumine (1 mg/kg), ketoprofen (3 mg/kg), or metamizole (35 mg/kg) administered IV for 2 to 3 d. Prokinetic drugs were used for 1 to 7 d (median: 3 d) in 14 cows. Five cows received neostigmine (Konstigmin; Vetoquinol, Bern, Switzerland), 40 to 45 mg, administered via a continuous drip infusion; and 9 received IM metoclopramide (30 mg), usually 7 to 9 times at 8 h intervals (metoclopramide was only used in the first few study years). Five cows with hypocalcemia (calcium < 2.0 mmol/L) received 500 mL of 40% calcium borogluconate administered IV. In 7 cows, hypokalemia (potassium < 4.0 mmol/L) was treated with daily oral doses of 60 to 100 g of potassium chloride until normokalemia occurred.

Short-term outcomes of 21 cows in which the surgery was completed

Three cows died or were euthanized within 3 d of surgery because of progressive deterioration. With 1 exception, the general condition of the surviving cows improved and returned to normal within 1 to 10 d (median: 3.0 d) of surgery. The appetite returned to normal in all remaining 18 cows within 2 to 10 d (median: 3.0 d) and fecal output became normal within 1 to 7 d (median: 3.0 d). In the first 7 d after surgery, the median rectal temperature ranged from 38.5 to 38.9°C. The median heart rate, which was elevated at 96 bpm on admission, returned to the normal range, from 72 to 76 bpm, in 1 to 7 d following surgery. Thirteen cows were discharged and in good health within 5 d after surgery, and the remaining 5 cows within 6 to 14 d after surgery.

Comparison of 18 surviving and 29 non-surviving cows

The median duration of illness on admission was 12 h in both groups. Furthermore, the median heart rate (88 versus 100 bpm), rectal temperature (38.5 versus 38.4°C), and respiratory rate (28 versus 28 breaths per min) did not differ significantly between the groups. In contrast, the groups differed significantly with respect to the following variables assessed on admission: severely abnormal general condition (16.7 versus 37.9%, P < 0.05), rumen stasis (22.2 versus 79.3%, P < 0.01), and intestinal atony on auscultation (16.7 versus 48.3%, P < 0.05) (Figure 4). Of the laboratory variables, concentrations of urea (6.5 versus 9.8 mmol/L, P < 0.01) and magnesium (0.98 versus 1.30 mmol/L, P < 0.05) differed significantly between surviving and non-surviving cows.

Figure 4.

Differences in poor general condition (P < 0.05), rumen stasis (P < 0.01), and intestinal atony (P < 0.05) in cows with small intestinal volvulus that survived (n = 29) and those that did not survive (n = 18).

Long-term outcomes of the 18 discharged cows

The long-term outcome was determined 2 y after discharge via a telephone interview. Eleven (61.1%) cows had remained productive in their respective herds, 4 had been slaughtered for economic reasons, and the outcome was not known for the remaining 3 cows.

Postmortem findings

The principal findings for the 29 cows that died or were euthanized were SIV and hemorrhagic infarction of the involved intestines (Figure 5). Blood clots in the intestinal lumen were seen in 4 cows, bleeding intestinal ulcers were seen in 1, and an intussusception in the twisted area of intestines was seen in 1 other. Five other cows had acute fibrinous peritonitis and 2 had ruptured intestines.

Figure 5.

Photograph showing segmental small intestinal volvulus in a 5-year-old Brown Swiss cow. The cow was normal when put on pasture in the morning but had severe colic a few hours later. The cow was referred to our clinic immediately and operated on, but could not be saved. The proximal 2/3 of the jejunum were twisted and severely dilated and the intestinal wall had a dark red to purplish-blue discoloration.

Discussion

Compared with SIV, intestinal changes are less severe in cattle with intussusception (19) and more severe in those with mesenteric torsion (21). This is reflected by the spectrum of clinical findings, which in cattle with SIV often lie between those of intussusception (19) and mesenteric torsion (21). A good example to illustrate this is colic. When combined with reduced or absent fecal output, colic is a primary sign of mechanical ileus in cattle (26). In the present study, 66.0% (31/47) of the cows had signs of colic, compared with 46.8% (59/126) of cattle with intussusception (19). The frequency of colic in cattle with mesenteric torsion was 65.6% (40/61) (21), similar to that in cows with SIV. The colic phase lasts only about 12 h (22), which likely explains why 34.0% (16/47) of cows with SIV did not have signs of colic. It can be assumed that, at the time of admission, the cows without colic had already progressed to the indolence or even the intoxication phase. It is likely that these cows had colic before admission, because 70.2% (33/47) had a history of colic and similar observations have been reported by others (3,26). Of 51 cattle with SIV, 64.7% (33/51) had a history of colic; but at the time of admission, only 39.2% (20/51) had signs of colic. Therefore, it is important to remember that, although colic is a cardinal sign of SIV, its absence does not rule out the condition.

Tachycardia occurred in 68% (32/47) of cows with SIV. The frequency of tachycardia in cows with SIV was higher than that in cattle with intussusception (38.1%, 48/126) (19) and lower than that in cattle with mesenteric torsion (80.3%, 49/61) (21). Mesenteric torsion and SIV have more severe hemodynamic effects and a more rapid onset of toxemia than intussusception and strangulation (12). Of all clinical signs, rumen atony had the highest predictive value for survival; 79.3% (23/29) of the non-surviving cows had no rumen motility, compared with only 22.2% (4/18) of cows that survived. Thus, rumen atony in cows with SIV is a prognostic sign of poor outcome. Likewise, intestinal atony is a cardinal sign of ileus but was seen in only 36.2% (17/47) of cows with SIV. Tests by BSA or PSA were frequently positive on the right side. However, positive BSA and/or PSA also occurs with other conditions, including right abomasal displacement, abomasal torsion, cecal dilatation, and severe diarrhea. This finding is always serious and pointed to a disorder on the right side of the abdomen in our study population. Dilated small intestine is typical of small intestinal ileus (26) and could be palpated transrectally in 48.9% (23/47) of cows with SIV. Thus, the likelihood of transrectal findings without dilated small intestines in cows with SIV is relatively high, at more than 50%. Dilated large intestines could be palpated in only 6.4% (3/47) of cows with SIV, compared with 44.1% (26/59) of cows with mesenteric torsion (21), 13.6% (3/22) of cows with ileal impaction (27), and no cows with intussusception (19). Dilated small intestines could be palpated transrectally in 4 of 4 cows with SIV (10), whereas in 8 adult cattle with SIV, dilated intestinal loops could only be palpated after the disorder had progressed (3).

In addition to tachycardia and hypothermia, 51.1 to 66.0% of cows with SIV had sunken eyes, prolonged capillary refill time, reduced skin surface temperature, and reduced skin elasticity. This was similar to findings in cows with internal herniation (28), intussusception (19), and mesenteric torsion (21), and reflected shock-associated changes. Of 12 cows with ileal impaction, 10 of which had only mild changes in general condition, < 50% had vital signs typical of shock (27). In summary, comparing clinical signs of cows with different forms of ileus shows that the frequency and severity of clinical signs of cows with SIV fall between those of cows with intussusception and mesenteric torsion. The most serious clinical signs are almost always seen in cows with mesenteric torsion because of the grave tissue changes associated with this condition.

The principal laboratory changes in cows with SIV were hypocalcemia (74.1%, 20/27), hypokalemia (73.8%, 31/42), azotemia (62.8%, 27/43), hypermagnesemia (61.5%, 16/26), and hemoconcentration (60.0%, 27/45); the latter 2 results also reflect shock. By comparison, hemoconcentration was seen in 61.1% (77/126) and 71.7% (43/60) and azotemia was seen in 62.1% (77/124) and 52.5% (31/59) of cows with intussusception and mesenteric torsion, respectively (19,21). The cause of hypermagnesemia is thought to be reduced glomerular filtration because of dehydration (29); this is supported by the observation that the surviving and non-surviving cows differed significantly with respect to median magnesium (0.98 versus 1.30 mmol/L) and urea (6.5 versus 9.8 mmol/L) concentrations. Hypochloremic metabolic alkalosis was a rare finding because SIV is an acute disease and the ileus was primarily located in the jejunum (hypochloremia, 37.2%, 16/43; increased blood pH, 11.8%, 4/34; increased rumen chloride concentration, 24.3%, 9/37) in the present study. It is therefore possible that the time from the occurrence of the volvulus to clinical examination was too short for the electrolyte and blood-gas changes to become manifest, which has been suggested by other authors (16,30). Another possibility for the frequent occurrence of acidosis in the present study (52.9%, 18/34) is the secondary development of metabolic acidosis caused by an increase in L-lactate in addition to the underlying alkalosis. The increase in L-lactate results from ischemia of the intestinal wall and subsequent necrosis (1,26,31).

Almost 25% of the cows underwent surgery in lateral or sternal recumbency; some intentionally from the start of surgery and others because they became recumbent during the procedure. The risk of unintentional recumbency and possible contamination during surgery in cows with suspected SIV should be considered carefully when planning the surgery. It may be prudent to conduct the surgery of compromised and fractious cows under sedation and in sternal or lateral recumbency.

Concerning outcome, the percentage of cows discharged was 38.3% (18/47) of those with SIV, which was higher than that of cows with mesenteric torsion (23%, 14/61) (21) and lower than that of cows with intussusception (44.4%, 56/126) (19), internal herniation (55.6%, 10/18) (28), and ileal impaction (100%, 22/22) (27). In previous reports, 100% (4/4) (10) and 27.5% (14/51) of cattle with SIV (3) were discharged. Early diagnosis and immediate surgical treatment were considered crucial for a successful outcome. The success rate was 66.7% (10/15) when the duration of illness was up to 12 h, but was only 15.8% (3/19) in cattle that had been ill for 13 to 48 h. Cattle that had been ill for longer than 2 d did not survive (3).

In conclusion, intestinal ileus must be ruled out in cattle with acute onset of severe illness accompanied by reduced or absent fecal output, even in the absence of colic. However, identifying the type of ileus is difficult based on clinical findings. Laboratory examinations are critical for determining the degree of dehydration and assessing electrolyte and acid-base imbalances to optimize supportive treatment. Ultrasonography aids in the diagnosis of ileus, but the actual volvulus in this study could not be visualized. Immediate surgical treatment is essential for a favorable outcome.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the technicians of the medical laboratory for the hematological and biochemical analyses, the veterinary students for monitoring the cows during the night, and the agricultural assistants for their help with the clinical examinations. Thanks also to the many veterinarians who examined and treated the patients and assisted in the surgeries. CVJ

Footnotes

Use of this article is limited to a single copy for personal study. Anyone interested in obtaining reprints should contact the CVMA office (kgray@cvma-acmv.org) for additional copies or permission to use this material elsewhere.

References

- 1.Anderson DE, Constable PD, St Jean G, Hull BL. Small-intestinal volvulus in cattle: 35 cases (1967–1992) J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1993;203:1178–1183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith DF. Surgery of the bovine small intestine. Vet Clin North Am Food Anim Pract. 1990;6:449–460. doi: 10.1016/s0749-0720(15)30869-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rademacher G, Lorenz I. Diagnose, therapie und prognose des volvulus intestini beim rind [article in German] Tierärztl Umschau. 1998;53:93–105. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anderson DE, Ewoldt JMI. Intestinal surgery of adult cattle. Vet Clin North Am Food Anim Pract. 2005;21:133–154. doi: 10.1016/j.cvfa.2004.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Desrochers A, Anderson DE. Intestinal surgery. Vet Clin North Am Food Anim Pract. 2016;32:645–671. doi: 10.1016/j.cvfa.2016.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vogel SR, Nichols S, Buczinski S, et al. Duodenal obstruction caused by duodenal sigmoid flexure volvulus in dairy cattle: 29 cases (2006–2010) J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2012;241:621–625. doi: 10.2460/javma.241.5.621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Russell S. Duodenal sigmoid flexure volvulus and gall bladder displacements in dairy cows. Vet Rec. 2013;173:121–122. doi: 10.1136/vr.f4807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dirksen G, Doll K. Dünndarmverschlingung. In: Dirksen G, Gründer HD, Stöber M, editors. Innere Medizin und Chirurgie des Rindes. Berlin, Germany: Parey Buchverlag; 2002. pp. 525–527. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Radcliffe RM. Small-intestine surgery in cattle. In: Fubini SL, Ducharme NG, editors. Farm Animal Surgery. St. Louis, Missouri: Elsevier; 2017. pp. 309–317. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fubini SL, Smith DF, Tithof PK, Perdrizet JA, Rebhun WC. Volvulus of the distal part of the jejunoileum in four cows. Vet Surg. 1986;15:150–152. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Constable PD, Hinchcliff KW, Done SH, Grünberg W. Diseases of the intestines of ruminants Veterinary Medicine A Textbook of the Diseases of Cattle, Horses, Sheep, Pigs, and Goats. St. Louis, Missouri: Elsevier; 2017. pp. 523–530. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Francoz D, Guard CL. Volvulus of the large and small intestine around the mesenteric root. In: Smith BP, Van Metre DC, Pusterla N, editors. Large Animal Internal Medicine. St. Louis, Missouri: Elsevier; 2020. p. 896. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pearson H, Pinsent PJN. Intestinal obstruction in cattle. Vet Rec. 1977;101:162–166. doi: 10.1136/vr.101.9.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Steiner S, Krametter-Frötscher R, Baumgartner W. Mechanischer ileus beim erwachsenen rind, eine retrospektive studie [article in German] Wien Tierärztl Mschr. 2008;96:166–176. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Braun U. Ultrasonography of the gastrointestinal tract in cattle. Vet Clin North Am Food Anim Pract. 2009;25:567–590. doi: 10.1016/j.cvfa.2009.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anderson DE. Intestinal volvulus of cattle. In: Anderson DE, Rings DM, editors. Current Veterinary Therapy Food Animal Practice. St Louis, Missouri: Saunders Elsevier; 2009. pp. 120–121. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Volz C. Klinische, labordiagnostische und sonographische Befunde sowie Therapie und Verlauf bei 168 Rindern mit Volvulus jejunalis, Torsio mesenterialis und Colonscheibentorsion [Dr. med. vet. dissertation] Zurich, Switzerland: University of Zurich; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rosenberger G. Clinical Examination of Cattle. Berlin, Hamburg, Germany: Paul Parey; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Braun U, Gerspach C, Volz C, Boesiger M, Hilbe M, Nuss K. A retrospective review of small intestinal intussusception in 126 cattle in Switzerland. Vet Rec Open. 2023;10:e58. doi: 10.1002/vro2.58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Braun U, Nuss K, Reif S, Hilbe M, Gerspach C. Left and right displaced abomasum and abomasal volvulus: Comparison of clinical, laboratory and ultrasonographic findings in 1982 dairy cows. Acta Vet Scand. 2022;64:40. doi: 10.1186/s13028-022-00656-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Braun U, Gerspach C, Volz C, Hilbe M, Nuss K. Dilated small and large intestines combined with a severely abnormal demeanor are characteristic of mesenteric torsion in cattle. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2023;261:1531–1538. doi: 10.2460/javma.23.05.0243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gründer HD. Kolik beim rind [article in German] Prakt Tierarzt. 1984;66:84–86. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Braun U, Amrein E, Koller U, Lischer C. Ultrasonographic findings in cows with dilatation, torsion and retroflexion of the caecum. Vet Rec. 2002;150:75–79. doi: 10.1136/vr.150.3.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nuss K, Schwarz A, Ringer S. Lokalanästhesien beim wiederkäuer [article in German] Tierärztl Prax. 2017;45(G):159–173. doi: 10.15653/TPG-161061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.D’Anselme O, Hartnack A, Andrade JSS, Alfaro Rojas C, Ringer SK, de Carvalho Papa P. Description of an ultrasound-guided erector spinae plane block and comparison to a blind proximal paravertebral nerve block in cows: A cadaveric study. Animals. 2022;12:2191. doi: 10.3390/ani12172191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dirksen G. Ileus beim Rind. In: Dirksen G, Gründer HD, Stöber M, editors. Innere Medizin und Chirurgie des Rindes. Berlin, Germany: Parey Buchverlag; 2002. pp. 514–517. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nuss K, Lejeune B, Lischer C, Braun U. Ileal impaction in 22 cows. Vet J. 2006;171:456–461. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2005.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ruf-Ritz J, Braun U, Hilbe M, Muggli E, Trösch L, Nuss K. Internal herniation of the small and large intestines in 18 cattle. Vet J. 2013;197:374–377. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2013.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grünberg W, Constable P, Schröder U, Staufenbiel R, Morin D, Rohn M. Phosphorus homeostasis in dairy cows with abomasal displacement or abomasal volvulus. J Vet Intern Med. 2005;19:894–898. doi: 10.1892/0891-6640(2005)19[894:phidcw]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Doll K. Hämatologische und klinisch-chemische untersuchungsbefunde bei kälbern und jungrindern mit Ileus [article in German] Tierärztl Prax. 1991;19:44–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fubini SL, Yeager AE, Divers TJ. Noninfectious diseases of the gastrointestinal tract. In: Peek SF, Divers TJ, editors. Rebhun’s Diseases of Dairy Cattle. St. Louis, Missouri: Elsevier; 2018. pp. 168–248. [Google Scholar]