Abstract

Over the last 50 years, there has been a plethora of research exploring sexual offending with a recent focus on online offending. However, little research has focused on voyeurism despite convictions and media awareness growing rapidly. Currently, there is sparse theoretical or empirical literature to guide research and practice for individuals engaging in voyeuristic behaviors. As such, 17 incarcerated men with a conviction of voyeurism in the UK were interviewed on the cognitive, affective, behavioral, and contextual factors leading up to and surrounding their offense(s). Grounded theory analyses were used to develop a temporal model from background factors to post-offense factors; the Descriptive Model of Voyeuristic Behavior (DMV). The model highlights vulnerability factors for men engaging in voyeuristic behaviors in this sample. Following this, the same 17 men were plotted through the model and three key pathways were identified: Sexual Gratification, Maladaptive Connection Seeking, and Access to Inappropriate Person(s). The characteristics of each pathway are discussed, and treatment implications considered.

Keywords: offense chain model, grounded theory, voyeurism, voyeuristic behavior, non-contact sexual offending, paraphilias

Introduction

Significant efforts have been made to understand sexual offending over the last four decades. Much of this research has focused on developing models for contact sexual offending, such as sexual abuse of children (e.g., Finklehor, 1984; Seto, 2019; Ward & Beech, 2016). In the last decade, however, there has been an increased examination of online sexual offending (Seto, 2013) with a primary focus on sexual harassment (see Henry & Powell, 2018) and online offenses against children (see Beech et al., 2008 for a review) in line with advances in technology. However, there has been little focus on other non-contact sexual offenses such as voyeurism (Mann et al., 2008; McAnulty et al., 2001).

Lack of research examining voyeurism and other non-contact sexual offenses is problematic given the stark differences between individuals engaging with contact and non-contact offenses (Babchishin et al., 2015; Elliott et al., 2009; 2013; MacPherson, 2003). In addition, whilst research has suggested that the general community may believe that non-contact offenses, such as voyeurism, do not cause harm (Blagden et al., 2014; Doyle, 2009), many victims report psychological distress and traumatizing effects (Cox & Maletzky, 1980; Duff, 2018; Simon, 1997; Thompson, 2019).

Voyeurism is defined as viewing an unsuspecting and non-consenting person(s) engaging in private activities such as undressing, using the bathroom, or engaging in sexual activity (Kaplan & Krueger, 1997; Långström & Seto, 2006) for sexual purposes (Duff, 2018). Voyeuristic behaviors can also include those which are facilitated by technology, such as recording over toilet cubicles, installing cameras in a private space, hacking webcams, or, more recently, ‘upskirting’. ‘Upskirting’ is where an image or recording is taken underneath someone’s clothing, and this behavior has recently come into public knowledge and since been included in legislation following multiple campaigns (Lewis & Anitha, 2022; Thompson, 2019). In addition, individuals who are sexually aroused by and engage with voyeuristic behaviors (among other symptoms) could be diagnosed with voyeuristic disorder under the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5; American Psychological Association, 2013) and the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems Manual (ICD-11; World Health Organization, 2019).

Voyeurism has been criminalized in a number of countries such as the UK, some states in the USA, China, Singapore, as well as others, with new laws being introduced in recent years. Thus, voyeurism is being recognized as a problem that needs attention from researchers, clinicians, and justice systems (Hocken & Thorne, 2012; Mann et al., 2008). However, legislation does not always specify that a victim has to be unsuspecting to be convicted of voyeurism. Under UK legislation, for example, a victim need not be unaware of the voyeuristic act. As a result, under this legislation, a conviction of voyeurism can be made if victims, during private activities, are aware they are being watched/recorded but do not consent (Sexual Offences Act, 2003). Thus, there is a discrepancy between the use of the term voyeurism amongst the general public, justice systems, researchers, and clinicians. Therefore, for the purpose of this study, voyeuristic behavior is what is discussed throughout.

Previous research conducted examining the prevalence of individuals engaging in voyeuristic behavior has focused on the general population, consistently producing high prevalence rates of between 12.00-34.50% across many different countries including Canada, Czechia, and Sweden (e.g., Bártová et al., 2021; Joyal & Carpentier, 2017; Långström & Seto, 2006). However, Rye and Meaney (2007) found that 79% (n = 318) of community participants in Canada self-reported that they would engage in voyeuristic behaviors provided there was assurance they would not be caught. In addition, the literature suggests that sexual interest and engagement in voyeuristic behaviors is consistently higher than any other paraphilia (Bártová et al., 2021; Joyal & Carpentier, 2017; Långström & Seto, 2006). Yet, the incarcerated population of individuals who have engaged in voyeuristic behaviors has remained largely uninvestigated (Mann et al., 2008).

Other than prevalence studies, to date, there has been minimal research examining voyeurism, particularly with regards to the role of technology. A few case study formulations (e.g., Duff, 2018) have been conducted as well as aging research primarily conducted in the 1970s (e.g., Gebhard et al., 1965; Smith, 1976) and literature reviews urging for more research (e.g., Mann et al., 2008). Recently, however, Wood (2019) investigated motivations for men engaging in voyeuristic behaviors. Using interpretative phenomenological analysis, Wood discovered themes to suggest that voyeuristic behaviors stemmed from a need for intimacy, escapism, or habit. However, Wood also emphasized the need for more research and validation of her findings.

The Motivation-Facilitation Model of Sexual Offending (MFM; Seto, 2008; Seto, 2019) is a comprehensive model of sexually offending. Within this model, it is suggested that all sexual offending is driven by one or a combination of three motivators: having a paraphilia, high sex drive, or intense mating effort. Offending is then hypothesized to be facilitated by state (e.g., alcohol use) and trait (e.g., antisociality) factors as well as situational factors (e.g., access to victims). Recently, Seto suggested that the MFM could be applicable to non-contact sexual offenses such as exhibitionism and voyeurism (Seto, 2019). However, as Seto states, this is difficult to test given the dearth of literature on voyeurism.

Over the last decade, professionals working with men engaging in voyeuristic behaviors have repeatedly requested that further research be conducted (e.g., Duff, 2018; Hocken & Thorne, 2012; Mann et al., 2008; Seto, 2019). Due to lack of research, it is difficult for professionals working with men who have engaged in voyeuristic behaviors to identify treatment targets to ensure treatment efficacy. Professionals describe this situation as “dangerous” (Mann et al., 2008, p. 326). This is concerning for risk management given the repetitive and compulsive nature of the offense (Abel et al., 1987; APA, 2013; Raymond & Grant, 2008; Wood, 2019), high prevalence rates (e.g., Kar & Koola, 2007), and the possibility that voyeurism engagement may be a gateway offense (Longo & Groth, 1983; Schlesinger & Revitch, 1999).

Grounded theory (Strauss & Corbin, 1998) is a useful approach for developing theory and models when existing research is sparse (Ward et al., 2006), such as the case with voyeuristic behavior. Grounded theory is exploratory in nature and requires techniques (such as line-by-line coding) to ensure that analysis is built from the ground up (Strauss & Corbin, 1998). In other words, Grounded theory relies on the interpretation of the data coming from participants’ experiences rather than researchers’ own interpretations (Strauss & Corbin, 1998). Grounded theory analysis has been used to generate offense-chain theories of varied criminal behaviors providing descriptive pathways of the behavioral, cognitive, and affective events preceding, during, and following an offense (Barnoux et al., 2015; Gannon et al., 2008; Tyler et al., 2014; Ward et al., 1995).

Offense-chain theories have been highly valuable for both research and risk management (Tyler et al., 2014). This is because they enable professionals to pinpoint the key features leading up to an offense and, as such, identify potential risk factors and treatment needs (Tyler et al., 2014). The aim of the current study is therefore to develop an offense-chain model for individuals engaging in voyeuristic behaviors and to examine the cognitive, behavioral, affective, and contextual factors relating to voyeuristic behaviors.

Method

Participants

Twenty-two men who had engaged in voyeuristic behaviors were recruited from five prison establishments in the UK. Participants were identified either by researchers on the prison database and/or by the Psychology department at the establishment screening for acts of voyeuristic behavior, thus purposive sampling methods were employed. Five of the participants in the initial screening process met the criteria of having engaged in voyeuristic behavior but were later excluded due to voyeurism being too interlinked with other offenses, such as inciting a child to engage in sexual activity or kidnapping. Consequently, a more stringent approach was taken whereby participants needed to have a conviction for voyeurism. Hence, the final sample consisted of 17 men with a conviction of voyeurism as their index offense.

For all remaining participants except three, voyeuristic offenses against adults met the DSM-5-TR (APA, 2022) criteria of voyeurism (i.e., the victim was unsuspecting and non-consenting). The exceptions, however, were participants who were convicted of voyeurism yet stated that their victims were aware. However, a close examination of their recorded offense details highlighted that the victims themselves reported being unaware of the voyeuristic behavior. These participants remained in the sample as it is expected that clinicians would come across individuals with similar demographics in the future, and therefore the authors wished to be inclusive of this for treatment purposes.

The averaged self-reported number of instances that participants engaged in voyeuristic behaviors was 5.06 (SD = 6.12), with the average number of convictions being 3.29 (SD = 4.62). Targets of the voyeuristic behavior were either adults (n = 8), children (n = 3), or indiscriminate (n = 6) victims, where indiscriminate refers here to voyeuristic behavior with no specific target in mind, such as installing cameras in non-gendered public toilets. Children, here, were defined as being under the age of 16, as per the legal age of consent in the UK. In addition, two participants had previous convictions of voyeurism.

All participants except one had at least one additional index offense. For five, these were non-contact sexual offenses including creation and/or possession of indecent images of children and/or inciting a child to engage in sexual behavior. The remaining 11 participants held a conviction for a contact sexual offense: eight participants were convicted of sexual assault against a child and three for rape of an adult.

Of the 11 individuals who held a contact sexual offense, for two participants the voyeuristic behavior occurred in the same temporal period as the contact offense. For example, recording of victims occurred before and after the sexual assault, but the assault was not recorded or part of the voyeurism conviction. For one participant, the voyeuristic behavior occurred during an act of rape against an adult (where the victim was unsuspecting due to being unconscious). For the remaining nine participants who had committed a contact sexual offense, their engagement in voyeuristic behavior occurred at least a couple of weeks prior to their contact offense. Furthermore, for seven participants, their contact offense was against a different victim to their voyeuristic engagement, where the victim was constant for the remaining four participants. In addition, seven of the 11 also held additional offenses including non-contact sexual offenses (e.g., possession and/or creation offenses) or related offenses against a person (e.g., bigamy, forced marriage, intimidation of witnesses, and actual bodily harm).

The mean age of the sample was 42.53 (SD = 13.99) with a range of 22–72 years. Therefore, there was a wide range of ages included in the study. All participants were British citizens, with the majority of the sample identifying as White (n = 14, 82.35%), and the remaining identifying as Mixed Race (n = 2, 11.76%) and Bangladeshi (n = 1, 5.88%). A small percentage of individuals in the sample had a high-level of education (foundation degree and above; n = 4, 23.53%). The remaining sample (n = 13, 76.47%) had varying levels of secondary education (GCSE’s and A-levels in the UK). One participant had treatment targeted towards their voyeuristic behavior, seven had received general sexual offending treatment, and the remaining nine had received none.

Participants were also asked if they had a sexual interest in any of the DSM-5 paraphilias, other than voyeurism. There were seven participants who stated that they had a sexual interest in children or adolescents, and nine who had convictions for sexual assault of a child. There were no other sexual interests reported. However, three participants were convicted for possession of extreme pornography all of which involved animals.

Procedure

This study was approved by the authors’ University Ethics Committee (Ref: 201,815,447,004,445,248) and the National Research Committee for Her Majesty’s Prison Service (Ref: 2019-184).

Participants who were identified by the researcher as eligible for the study were approached by the researcher who explained the study and verbalized the Information Sheet. If participants wished to take part in the study, their interview was scheduled for at least 24 hours after the initial conversation to ensure that men were able to fully consider participating. Upon meeting for the interview, participants were given the opportunity to ask questions and the consent form was signed. This was followed by a demographic form and then the interview. Each interview was audio recorded by the researcher and this was securely stored and then destroyed after verbatim transcription.

Interviews were conducted primarily by the first author. However, the first interview was conducted by the second author (with the first author present) for training purposes. No participants had any prior knowledge of or relationship with the authors. The interview was semi-structured such that standardized interview questions and probes were used to guide the interview. However, the interviewer was permitted to follow up on participants’ comments to enhance the understanding of each unique narrative given. As a result, the length of interviews varied from 51.08 to 153.00 minutes (M = 84.09; SD = 30.05). The standardized interview questions were adapted from previous studies of this nature (e.g., Gannon et al., 2008; Tyler et al., 2013; Ward et al., 1995) and covered affective, cognitive, behavioral, and contextual factors from childhood through to the voyeuristic behavior and events post-offense. Individuals who engaged in voyeuristic behavior more than once were asked about the lead up to each event that they could remember in detail to investigate re-offending following periods without voyeuristic engagement. Following the interview, file checks were conducted to obtain any additional demographic information (e.g., sentence length).

Data Analysis

Grounded theory analysis (Strauss & Corbin, 1998) was used to analyze each interview (N = 22). This study employed a constructivist approach to the grounded theory analysis such that the model was built upon participants’ understandings of the world.

There were three main stages to the analysis, formed of: open coding, axial coding, and selective coding.

The first stage was open coding. Interviews were analyzed line-by-line and broken down into basic units of meaning termed by Strauss and Corbin (1998) as meaning units within the context of the research question. An example of this can be seen below, where the slashes indicate where the meaning unit begins and ends and each subscript indicates one separate unit of meaning.

It’s a council estate 1 /with my mum and dad, three brothers. 2 /And so, so I didn’t really have a relationship with my dad3/

Following this, these meaning units were abstracted, and given descriptive labels that capture the characteristics of the unit. For example, “He didn’t have a relationship with his father” was abstracted from the meaning unit3 sample above.

General meaning units were then allocated a minimum of one provisional low-level category based on similar occurrences or phenomena with other meaning units. This was completed multiple times with constant comparison between general meaning units and low-level categories as new concepts were discovered, due to grounded theory analysis being a cyclical process (Gordon-Finlayson, 2010).

Following this, low-level categories were compared and linked based on conceptual similarly. This led to the creation of categories (usually temporal in nature) and subcategories (referring to different phenomena e.g., attitudes or contextual factors), in a process termed axial coding. For example, the above example was provisionally allocated the category Background Factors, with the secondary category of Paternal Relationship (negative). During axial coding, refinements were made to the first- and second-order categories. Theoretical sampling was used where data were collected until theoretical saturation. There were 22 interviews in total. However, the final batch of interviews did not lead to the development of any new emergent categories. Thus, theoretical saturation was still met after the exclusion of the five participants who did not meet the stringent inclusion criteria, and removal of these individuals also did not change any of the latter analysis. Theoretical saturation is key in grounded theory analysis (Strauss & Corbin, 1998) for ensuring quality in the data collected (Given, 2016).

In the final stage of the grounded theory (selective coding), all categories, with their associated subcategories, were integrated into a temporal sequence for all participants. This chronological arrangement of categories described the events before, during, and immediately after engagement with voyeuristic behaviors.

Validity and Reliability

For data validity, where possible, confidential file checks were carried out. Psychological assessments, previous offense history, and sentencing information were sought and compared to accounts given by participants. Any information which varied significantly was excluded, so as not to assume either narrative to be correct. This ensured that accounts were as valid as possible. For reliability, scripts were spot checked by the second author who examined the general meaning units following analysis by the first author. Following this, 20% of all scripts and general meaning units were checked by a second independent coder (a postgraduate researcher in Psychology). There was 74.6% agreement between the researchers and the independent coder, with the discrepancy explained by the independent researcher having used a more fine-grained approach. Lastly, the entire analytic process, namely each stage of the grounded theory analysis, was spot checked by the second author and another independent researcher.

Results

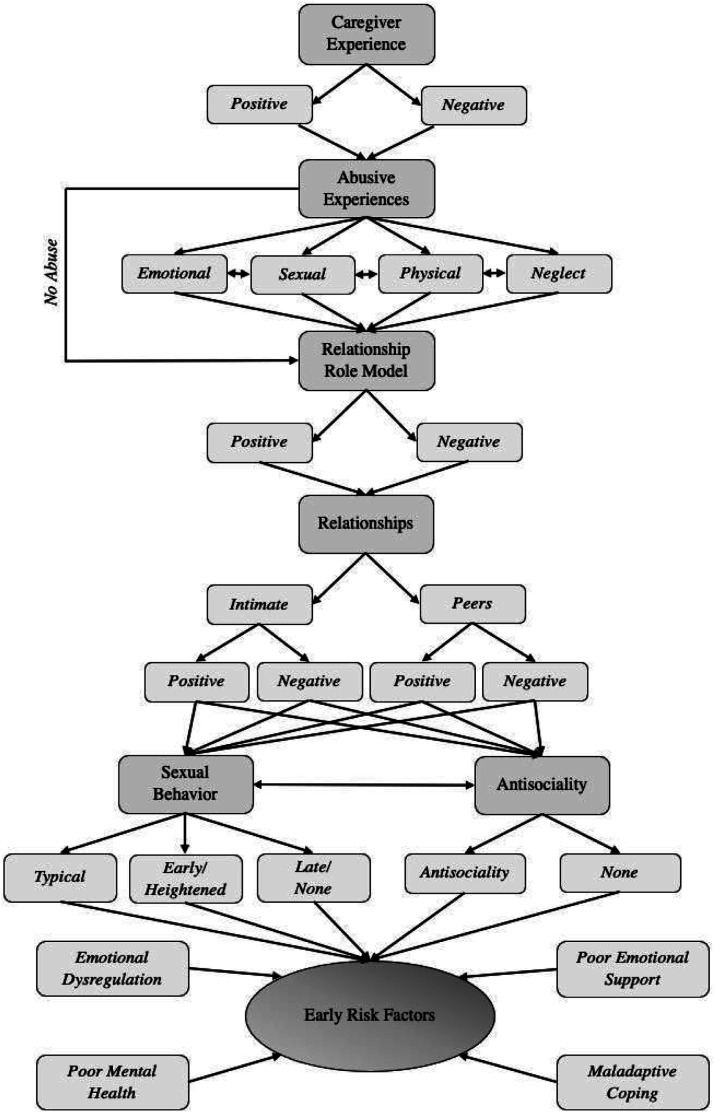

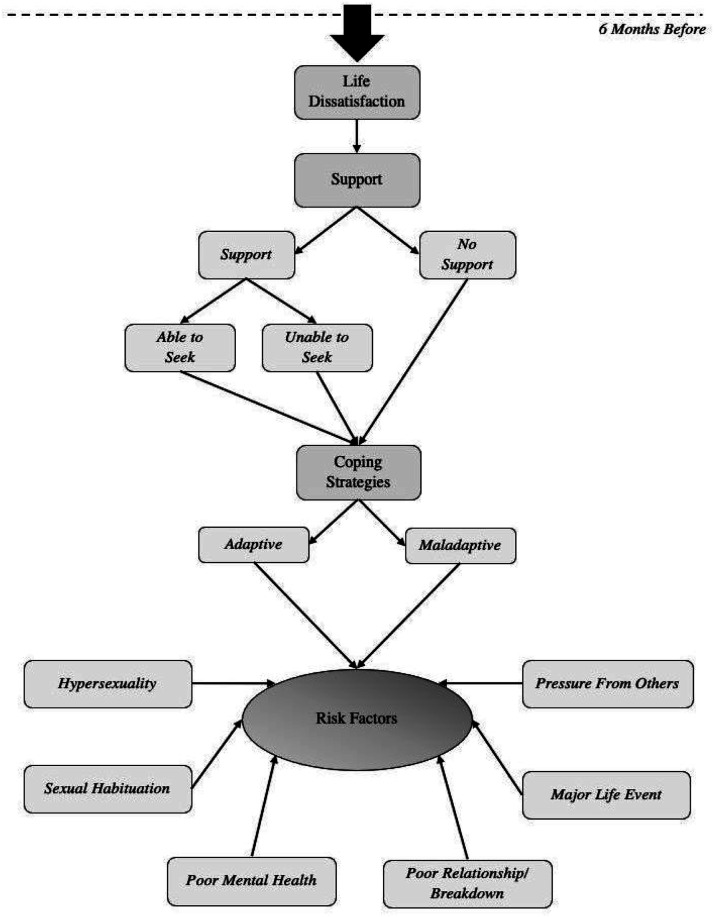

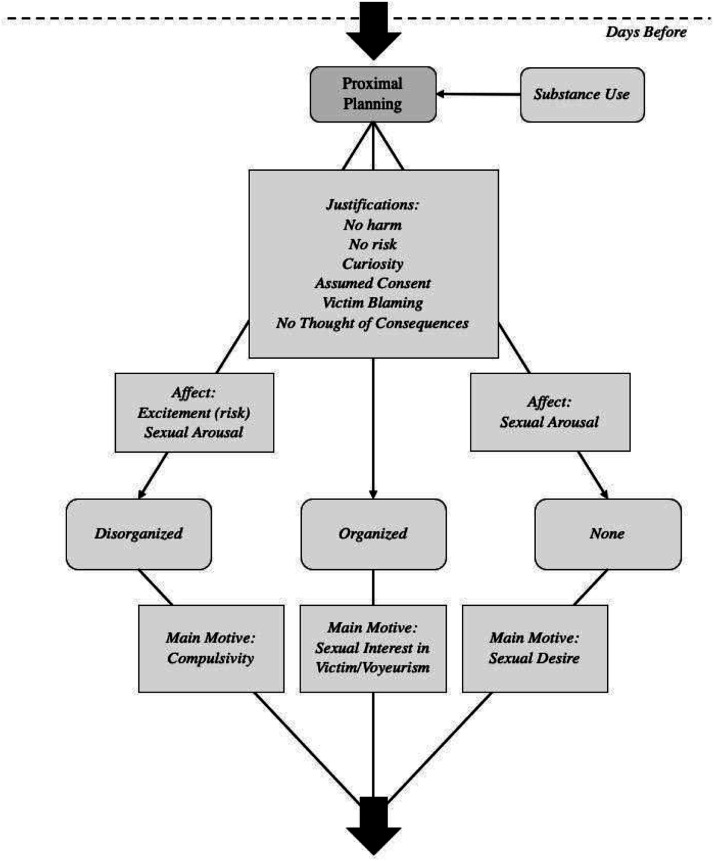

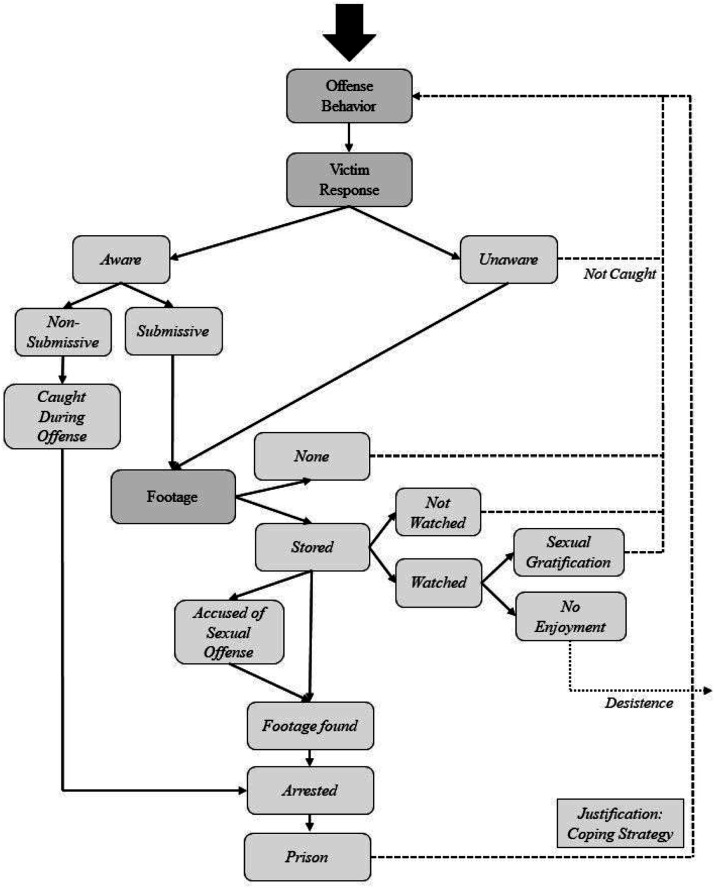

The model developed represents the temporal sequence of events that occurred leading up to and following voyeuristic behavior. This included cognitive, affective, behavioral, and contextual factors. The model can be divided into three main sections: (a) background factors – childhood, adolescent, and early adulthood factors, (b) distal factors—events 6 months to a few days prior to the offense, (c) proximal factors—events days before up to immediately prior to the offense, and (d) offense and post-offense factors—events at the time of, immediately following, and after the offense. This is represented in Figures 1–4 respectively.

Figure 1.

Background factors.

Figure 2.

Distal factors.

Figure 3.

Proximal factors.

Figure 4.

Offense and post-offense factors.

It is important to note here that participants were asked to discuss their voyeuristic behavior and relationship with voyeurism, where voyeurism was defined to each participant at the beginning of the interview. Most participants had multiple instances of engaging with voyeuristic behaviors in their history (convicted or not) and so they spoke about the lead up to their first instance of engaging in voyeuristic behavior and any other instances of engagement following this. This was important as the justifications and motivation for engaging in voyeuristic behaviors changed during this process. As a result, when discussing the number of participants in the distal, proximal, offense and post-offense factors, numbers may exceed the full sample size total of N = 17.

Background Factors

Factors relating to participants’ background are discussed at length in this model because it was felt that this would aid professionals in identifying treatment needs for voyeuristic behaviors. There was one participant unwilling to talk about their background, however, and therefore the number of participants at each stage may not total the full sample (N = 17). There were six main categories identified for background factors with each category divided into subcategories.

The first category, Caregiver Experience, describes participants’ experience with their caregivers. Caregivers included a range of individuals (e.g., birth parents, step-parents, foster parents, and grandparents). Experiences here were either predominately positive (n = 5) or predominately negative (n = 12). Negative experiences were those described by participants as challenging, such as stating an explicit dislike for a step-parent or that they “didn’t really have a relationship” with at least one parent.

Next, Abusive Experiences described whether participants had experienced abuse during their childhood or early adolescence. This category was comprised of emotional abuse (n = 6), sexual abuse (n = 4), physical abuse (n = 7), neglect (n = 7), or no abuse (n = 2). Participants could experience one or more of these indicated by the double headed arrows. This abuse was perpetrated by a range of individuals (e.g., caregivers, siblings, peers, and neighbors). Emotional abuse typically took place in the household and usually took the form of negative comments from caregivers such as being called “a disappointment” which participants experienced negatively. Sexual abuse was perpetrated by a range of individuals such as peers, neighbors, or caregivers. Physical abuse was typically perpetrated either in the household or through bullying by peers. Neglect was unanimously perpetrated by caregivers. This mostly took form as parentization where participants were having to provide significant care for another member of the family (such as younger siblings or parents), yet were not receiving this care themselves. This was regarded as neglect where participants documented finding this challenging. A very small number of participants did not report experiencing any abusive experiences.

Following this, Relationship Role Model describes the relationship between participants’ main caregivers. For example, a relationship between mother and stepfather. This was either largely positive (n = 8) or negative (n = 9). Just over half of the sample had a negative relationship role model which typically included witnessing frequent arguments between caregivers and relationship breakdowns, such that participants described this as troubling. A positive relationship role model, comparatively, was categorized as participants witnessing stable long-term relationships, typically between birth parents.

Next, Relationships described participants’ experience of both intimate and peer relationships (typically around mid-adolescence). Intimate relationships were further divided into positive (n = 6) and negative (n = 11) experiences. Positive experiences included reporting early intimate relationships as satisfactory. Negative intimate relationships, as experienced by the majority of the sample, included dissatisfaction with these relationships such as feeling regretful or frequent conflict, but also emotional abuse and infidelity. Peer relationships were also divided into positive (n = 3) and negative (n = 14) experiences. For the minority of participants, positive experiences included ease of developing friendships and building connections, and satisfaction within these friendships. Negative peer relationships, however, included difficulties making friendships, dissatisfaction with friendships, and peer bullying. This period, around mid-adolescence, was often emphasized by participants as being a particularly challenging time. All the subcategories for both Intimate and Peer Relationships fed into the next two categories.

It is important here to note that there was not one participant who reported a solely positive experience through each of these stages. All participants who had a positive caregiver experience, except one, had at least one abusive experience.

Following this were the categories Sexual Behavior and Antisociality. These are in the same temporal location in the model as these started to occur in participants’ lives around the same time. Sexual Behavior was comprised of Typical (n = 4), Early/Heightened (n = 10), and Late/None (n = 3). Typical sexual behavior related to those experiences which were deemed to be within typical sexual development, generally around the legal age of consent. This subcategory was predominately made up of individuals who had positive intimate relationship experiences, though this was not exclusively the case. Early/Heightened sexual behavior related to interest or engagement in sexual activity being in early adolescence or younger and/or promiscuous sexual behavior, and the most frequented category. This subcategory also included individuals who sexually offended or engaged in voyeuristic behaviors during their childhood. The majority (n = 8), although not all, of participants in this subcategory had previously experienced at least one negative intimate relationship. The Late/None subcategory related to individuals who reported no interest or engagement with sexual behavior during their mid-to-late adolescence. Typically, these individuals engaged with sexual activity much later in their lives.

The Antisociality category was comprised of two subcategories: Antisociality (n = 12) and None (n = 5). The majority of participants engaged with antisocial behavior such as using drugs, theft, or truancy, with few who showed no antisociality in their childhood. All those who had engaged in antisocial behavior, except one, had experienced negative peer relationships. Participants stated that their peer experiences led to them feeling adverse towards attending school. Furthermore, the single individual who did have positive peer relationships, had experienced at least one negative intimate relationship.

At this stage in the model, there was one individual who fitted into the typical sexual behavior subcategory and did not engage in antisocial behavior. However, this individual had been in all negative subcategories prior to this and had experienced abuse. As such, there was no one participant who had a solely positive experience throughout this period in the model.

Both the Sexual Behavior and Antisociality categories then fed into the final category, Early Risk Factors. There were four factors which fed into this category: Emotional Dysregulation (n = 7), Poor Mental Health (n = 5), Poor Emotional Support (n = 13), and Maladaptive Coping (n = 7). Individuals could have one or more of these factors and they typically occurred mid-to-late adolescence. Emotional Dysregulation comprised difficulties managing emotions such as fighting peers or assaulting others resulting from heightened anger, high compulsivity and impulsivity, and sexual urges. No Emotional Support referred to impoverished emotional support from friends and family. Poor Mental Health related to participants who experienced difficulties in mental functioning resulting from depression or anxiety whether formally diagnosed or not. Lastly, Maladaptive Coping described maladaptive psychological and behavioral methods used to cope with adversity such as excessive alcohol use (typically before the legal age), drug use, and using engagement in voyeuristic behavior or sexual activity to cope.

Distal Factors

All 17 participants contributed to Distal factors where there were four key categories with subcategories. These were Life Dissatisfaction, Support, Coping Strategies, and Risk Factors. This temporal sequence spanned 6 months to a few days prior to the offense.

The first category, Life Dissatisfaction, represented poor life satisfaction mainly relating to high pressure and lack of enjoyment with work (including full-time caring responsibilities), financial difficulties and/or debt, and general unhappiness with life. All participants reported experiencing this.

Following this, was the Support category made up of Support (n = 12) or No Support (n = 6). Support was further subdivided into Able to Seek (n = 3) and Unable to Seek (n = 9). Here, support refers largely to emotional support, but it could also include physical support. Able to Seek support represented individuals who felt they had individuals (usually friends or family) in their life that they could reach out to if they needed support, but only a small number of participants had this experience, nor did this mean that participants chose to access this when needed. On the other hand, for the majority of participants, in the Unable to Seek subcategory, participants had a support network but felt unable to utilize it. The No Support subcategory described individuals who felt they had no one they could seek support from, usually as a result of self-isolation. As a result, for the large majority of individuals, they were not able to access support where needed.

Next, Coping Strategies, divided into Adaptive and Maladaptive, described the methods used to manage difficulties. Two participants were in the Adaptive subcategory and this was described as non-problematic ways in which participants managed stress and adversity. Example strategies here included seeking support from prosocial peers and reading. Maladaptive coping strategies were used by 15 participants, and therefore a great majority of the sample. This was described as strategies which were problematic, ineffective, or illegal such as sexual addiction, drug abuse, and overreliance on alcohol.

The last category, Risk Factors, was made up of six elements: Hypersexuality (n = 13), Sexual Habituation (n = 2), Poor Mental Health (n = 9), Poor Relationship/Breakdown (n = 9), Major Life Event (n = 9), and Pressure From Others (n = 2). All participants were characterized by one or more of each of these risk factors. Hypersexuality referred to individuals who were engaging in excessive sexual activity, both online and/or in-person (e.g., persistent and/or unrestrained pornography use such as watching it in public, and experiencing multiple sexual partners in a very short period of time). Participants also self-identified that their relationship with sexual activity/material was “bad” or becoming a problem. This was the case for the majority of individuals in this sample. Sexual Habituation described diminished or habituated emotional or physical response to sexual stimuli such as pornography; participants stated explicitly that sexual stimuli was “not enough” and noted a marked decline in physiological and emotional response. Poor Mental Health included individuals who were struggling with mental health issues, such as psychosis, depression, and anxiety, with over half the sample experiencing this. Poor Relationship/Breakdown categorized many participants who were in a negative or abusive relationship, or had a relationship breakdown. Major Life Event represented those who had a large change in their life such as a bereavement or significant relocation, and as such, were under greater strain than usual. This was experienced by a large number of individuals in the sample. Finally, for two individuals, Pressure From Others referred to those who felt pressured and encouraged to engage with voyeuristic behaviors from another individual.

There was only one participant who felt able to seek support and had adaptive coping strategies. However, this individual held four risk factors.

Proximal Factors

All 17 participants contributed to the Proximal factors section of the model which refers to the events days before through to minutes before the offense. All participants passed through the Proximal Planning factor where participants were either in the situation where the voyeuristic behavior occurred or began to think and plan the voyeuristic behavior. Here, five participants engaged with Substance Use at this stage (i.e., drugs or alcohol). In addition, all participants justified their voyeuristic behavior before engaging, with some more conscious justification than others.

For example, some participants stated that there was no harm in engaging in voyeuristic behavior, as depicted below:

“I get what I need from it, they haven’t got a clue, doesn’t affect them… it’s not like I actually sexually assaulted someone”

Participants felt there was no or very minimal risk of being caught:

“I think I felt invincible and I felt like I could do what I want”

“Cause I thought nobody would know… pretty much convinced myself that even if somebody was to see it, they wouldn’t say nothing ‘cause they’d think it was okay”

Participants justified their engagement in voyeuristic behaviors by stating that it was mere curiosity:

“I spose I was quite curious… ‘cause we always had a great connection. Erm, I spose led me to do that”

There was assumed consent from the victim:

“This kind of no, it’s like, it’s no mean yes kind of no.”

Participants engaged in victim blaming:

“I mean, you know, if you don’t want me to see you, close your curtains!”

Participants stated that there was no thought of consequences:

“It just ‘appened. It wasn’t a plan… Just on the spur of the moment”

Proximal Planning was also subdivided into Disorganized (n = 10), Organized (n = 8) or None (n = 3) depicting how participants planned to engage in voyeuristic behavior, if at all. The Disorganized category describes participants who engaged in voyeuristic behaviors in a way which was not planned at length. Typically, this involved no more than 24 hours planning and no equipment was purchased or created initially to facilitate the offense. This category is very broad due to a range of different behaviors. For example, individuals may have installed cameras for a purpose other than voyeurism (e.g., security) and used them to engage in voyeuristic behavior later. Another example is participants using their mobile phones or cameras (whether temporarily installed or held by the participant during the voyeuristic behavior) to record individuals albeit in a public place or in their home. Distinctively, participants in this category were often either driven by sexual arousal or more commonly, excitement about the risk of engagement and the adrenaline rush that this gave, like maladaptive thrill-seeking. These drivers occurred before planning the offense. As such, the main motive for the offense was often compulsivity, leading to the offense behavior.

The Organized category describes participants who showed a degree of conscious planning before engaging in voyeuristic behavior. This typically looked like individuals who bought or built cameras and installed these with the intention to view another individual(s), in the family home, the victims’ home, or a public place. The main motive for this category was usually sexual interest in the victim or in voyeurism more generally. Lastly, participants fell into the No Planning category if their engagement in voyeuristic behaviors had no clear planning and seemed spontaneous. Often it was a single incident in isolation following significant substance use and sexual arousal. The main motive for this category was sexual desire as the incidence of engaging in voyeuristic behavior typically followed sexual activity or perceived sexual contact. Notably, participants in this category typically described being intoxicated at this stage.

Offense and Post-Offense Factors

All 17 participants contributed to this section of the model, Offense and Post-Offense Factors. It is important here to note that in this section of the model, participant contributions fluctuated significantly at each stage due to repeat offending. In addition, although at many points during this stage, participants could go straight back to the offense behavior, indicating that the voyeuristic behaviors occurred in a close temporal timeframe, this was not always the case. On some occasions, this was directly following the voyeuristic behavior, whilst others this was days later. In addition, it may be that participants’ life satisfaction significantly improved after the offense and there was a long break before the next incidence of engagement in voyeuristic behavior and as a result, participants re-entered the model at the Distal or Proximal Factors stage of the model. As such, this section should be considered when thinking about the maintenance of the voyeuristic behavior.

Following the Offense Behavior, there was a Victim Response. Either the victim was Aware or Unaware that the voyeuristic behavior had taken place (note that this is the participant’s perception and does not necessarily match with the victim’s account). If the participant felt that the victim was unaware of the offense, and the participant had not yet been caught (as a result of footage), participants typically engaged in voyeuristic behaviors again. This is depicted by the solid dashed arrow back to Offense Behavior. Alternatively, where the participant reported that the victims could have been aware, either the victim was Submissive or Non-Submissive. If the victim was Non-Submissive, participants were caught during the offense, arrested, and imprisoned. However, if the victim was Submissive (usually the result of silencing the victim), what followed was contingent on whether participants recorded footage as part of their voyeuristic behavior.

Some participants did not take footage and these individuals typically engaged in voyeuristic behaviors again (indicated by the dashed line). These individuals generally continued to engage in voyeuristic behaviors until something changed e.g., victim becoming aware and non-submissive or recording footage. If participants took footage and stored this, the subsequent outcome was dependent on whether or not they viewed the footage. If they did not watch the footage, they engaged in voyeuristic behaviors again. Often, participants who stored but did not watch footage described this similarly to keeping a trophy. However, if they did watch the footage and they got sexual gratification, they also engaged in voyeuristic behaviors again. If they did not get any enjoyment from watching the footage, participants desisted from further voyeuristic behaviors and left the model at this point. This is indicated by the dotted line exiting the model on the right-hand side.

If participants stored the footage, this was usually the means by which the participant became apprehended for the offense. Either the footage was found in isolation by another party (e.g., partner or victims’ caregivers) or participants were accused of a sexual offense which led to their home being searched and the footage was found by police. Then, participants were arrested and imprisoned. It is important to note here, that Accused of Sexual Offense refers only to accusations being made; there were a number of participants who were acquitted of some of their charges, and some maintained their innocence despite a conviction. In addition, there was one participant who stated explicitly that had they not been caught for their voyeuristic behavior, they would have committed a contact offense.

Of the participants who had been released from prison following a previous sentence for voyeurism (n = 2), both of them engaged in voyeuristic behavior again and were caught for the offense. Participants either consciously justified this further engagement as voyeurism being a coping strategy or it was clear to the researcher that engagement in voyeuristic behaviors were used in this way.

Lastly, it is of importance to note that there was no notable difference or pattern in technique used to engage in voyeuristic behavior (i.e., capturing footage or not) with any demographic within the sample. This included, for example, date of the offense, offense type, or any factor in the DMV.

Pathways

The same 17 participants were carefully plotted through the model to identify any patterns. The route or ‘pathway’ that each individual took through the model was subject to preliminary examination to identify any commonalities. This led to three main pathways in the model: ‘Sexual Gratification’ (n = 6), ‘Maladaptive Connection-Seeking’ (n = 5), and ‘Access to Inappropriate Person(s)’ (n = 7). It is important to note here that the total number of participants in each pathway exceeds the number of participants that took part in the study. However, as this study asked participants to discuss each instance of voyeuristic behavior in detail, one participant fitted two pathways as a result of two different periods of engagement in voyeuristic behavior in their life which were more than 6 months apart.

Participants who followed the ‘Sexual Gratification’ pathway generally engaged in voyeuristic behavior as means for sexual satisfaction. This was either resulting from sexual interest in voyeurism or general hypersexuality (occasionally due to sexual addiction). Some individuals on this pathway also used engagement in voyeuristic behaviors as a coping strategy as indicated by the quotes below:

“I felt completely numb and the voyeurism is what popped into my mind… it was that escapism for me, from my life… a safety net for me”

“it felt natural as if I’d been doing it for years… my kind of escape from reality”

Participants on this ‘Sexual Gratification’ pathway were mostly Disorganized Planners in the model (n = 5) and many fitted into the ‘Poor Mental Health’ early risk factor (n = 4). In addition, men on this pathway were much more likely to engage in voyeuristic behaviors frequently and go onto commit a contact offense. As such, men on this pathway could be considered at greater risk to the community.

Participants who followed the ‘Maladaptive Connection-Seeking’ pathway engaged in voyeuristic behaviors as means to connect with others. This was typically through long-term sexual relationships with adolescents, or individuals were searching for opportunities to engage in voyeuristic behaviors when feeling isolated. This pathway also included individuals who later used footage from their voyeuristic behavior to blackmail victims. In this pathway, voyeuristic behaviors were typically part of another offense or in addition to this offense, and there was no main type of Proximal Planning definitive to this path. However, all men on this pathway fitted the ‘No Emotional Support’ early risk factor (n = 5) and most also held the ‘Poor Relationship/Breakdown’ factor (n = 4).

Participants who followed the ‘Access to Inappropriate Person(s)’ pathway engaged with voyeuristic behaviors as means to gain access to intimate parts of another person’s life that they ordinarily would not be able to access. This was either to gain access to sexual images of children or a person that they could not have a relationship with. For example, this could be a stepchild or stepsibling, or a married neighbor. Typically, men on these pathways were Organized Planners in the model (n = 5) and ‘Maladaptive Coping’ was a salient early risk factor (n = 5).

Discussion

A Descriptive Model of Voyeuristic Behavior (DMV) has been developed using offense chain interviews from individuals who had engaged in voyeuristic behavior. The DMV provides a detailed overview of the contributory affective, cognitive, behavioral, and contextual factors that lead an individual towards engaging in voyeuristic behaviors. Namely, during the Background Factors stage, all participants had at least one negative experience and an early risk factor. The majority of the sample experienced negative peer and/or intimate relationships which, for most, led to antisociality and non-typical sexual behavior. Early risk factors included: emotional dysregulation, poor mental health, poor emotional support, and maladaptive coping. The 6 months before voyeuristic engagement was characterized by all participants experiencing life dissatisfaction and, for the majority of the sample, either no support or difficulties seeking available support. This was followed by the majority of the sample holding maladaptive coping strategies, and as a result, each participant holding one or more proposed risk factors: hypersexuality, sexual habituation, poor mental health, poor relationship/breakdown, major life event, and pressure from others. At the Proximal Factors stage, participants were categorized into three types of planners, each with their own motives for engaging in voyeuristic behavior: Disorganized planners, motivated by sexual compulsivity and driven by thrill-seeking, Organized planners, motivated by sexual interest in voyeurism or a specific victim, and None, motivated by sexual desire and driven by sexual arousal. Following an offense, maintenance of voyeuristic behaviors was dependent on the participant’s interpretation of the victim’s knowledge of the offense and whether footage was recorded and watched by the participant.

This model also provides three possible pathways to engagement in voyeuristic behaviors, capturing commonalities between individuals engaging in voyeuristic behaviors, yet also highlighting heterogeneity and associated treatment targets. Those pathways were: ‘Sexual Gratification’, ‘Maladaptive Coping Strategies’, and ‘Access to Inappropriate Person(s)’. The salient features of the DMV will be discussed with reference to the existing literature. Suggestions for future research will also be provided and model limitations considered.

One particularly salient feature of this model is that it not only provides a comprehensive overview of what leads an individual to engage in voyeuristic behaviors, but also what leads them to maintain their voyeuristic engagement through different time periods in their lives. Many of the participants in this sample engaged in more than one voyeuristic behavior, with an average number of 4.5 offenses. This mirrors the existing literature suggesting that engagement in voyeuristic behavior rarely occurs as a single incident (Abel et al., 1987) and indicates the need for an intervention to equip individuals with the skills to desist.

The DMV also indicates how individuals come to be caught for the offense. This may be useful with regards to policing voyeurism. The DMV shows that victims of voyeurism do not always report this behavior. This indicates a possible target for education, particularly given the uncertainty around non-contact offenses and how to report these (Gold, 2017). Future research could examine victims’ perceptions of voyeurism and the reasons underpinning reporting or non-reporting of this offense type. Wood (2019) suggests that failure to report voyeuristic acts may stem from such behavior being viewed as a nuisance crime that is not associated with conviction (Hocken & Thorne, 2012). In addition, the DMV also highlights that there may be an association with voyeuristic behavior and contact sexual offending, as this is often how individuals were caught. As such, whether voyeurism serves as a gateway into further offending requires significant investigation.

Another salient feature of the DVM is that individuals’ conscious justifications towards the offense or the victim hold a critical temporal position with regards to the offense. Such cognitions might be identified by clinicians in treatment and modified in an attempt to reduce recidivism. Future research could investigate pro-offending cognition held by individuals who engage in voyeuristic behaviors relative to individuals who engage in other offense types (e.g., Polaschek & Ward, 2002). This is particularly important given research indicating that attitudes supportive of sexual offending predict sexual recidivism (Helmus et al., 2013).

Furthermore, the DMV highlights that engagement in voyeuristic behavior may not always be sexually motivated. Amongst many participants, namely those who were ‘Disorganized’ planners, the driving factor to engaging with voyeuristic behavior was the risk of being caught and the excitement and thrill associated with this. Participants stated that sexual arousal was usually post-event and explained that during the thrill-seeking period there was no physiological response. Further, there were some participants who did not watch footage during or after the act of voyeurism and so did not experience any sexual arousal. Therefore, while it is often stated that voyeuristic behavior is driven by sexual gratification, this may not be the case for all individuals. This is a particularly important point when considering those ‘Organized’ planners in the model whose motivations to engage in voyeuristic behavior were thrill-seeking and/or gain (albeit emotional closeness to a friend or partner, or financial, for example) due to the result of pressure from another individual. Further, these individuals who are pressuring individuals to engage in voyeuristic behaviors (usually by installing cameras) are not being identified or reprimanded by the judicial system, and consequently are not receiving support for their own voyeuristic interest. These are important factors to consider when planning interventions for men engaging in voyeuristic behaviors, as well as for the judicial system, and for developing appropriate definitions of voyeurism.

The definition of voyeurism is brought into question when considering non-sexual motivations for engagement in voyeuristic behavior, as above. However, further to this is the discrepancy between definitions of voyeurism throughout the literature and current legislation. Legislation, at least in the UK, states that voyeurism must be for sexual gratification but a victim does not have to be unsuspecting, though many convicted participants deny any sexual motivation. On the other hand, voyeurism itself is defined as a sexual interest in voyeuristic behavior. Neither of these definitions fit the breath of individuals who are engaging in voyeuristic behaviors, and who may, in turn, be convicted of voyeurism. Yet, excluding any one of these individuals based on current definitions leaves clinicians with incomplete or partial empirical evidence for their important work. Clinicians have been, and will continue to be, presented with individuals with different motivations and relationships to voyeurism. As such, the definition of voyeurism is certainly something that needs further investigation and clarity.

Fourth, the DMV demonstrates the importance of positive adolescent relationships; there were a significant proportion of individuals who experienced either a negative peer (n = 16) and/or intimate (n = 14) relationship(s). Furthermore, most of the individuals who experienced negative peer or intimate relationships also engaged with antisocial behavior and/or had early or heightened sexual behavior. Thus, it may be indicative of early maladaptive coping and support-seeking behaviors. This may, in part, explain why a considerable number of individuals either had no support or felt they could not access the support available to them in the period before their offense (n = 18). As such, developing and maintaining prosocial support would be an important target in treatment for individuals who have engaged in voyeuristic behaviors. This is particularly important as research indicates that social support is an important factor for desistence (Chouhy et al., 2020; De Vries Robbé et al., 2015).

There are a number of both static and dynamic risk factors well-established in the literature used to assess the risk levels of individuals who have sexually offended (see de Vries Robbé, 2015 for a review). Similar factors to those found in this study include dysfunctional coping, impulsivity, hypersexuality, and negative social influences. However, in the DMV, there are additional factors such as sexual habituation and poor mental health which may represent factors specific to engaging in voyeuristic behavior. There has also been a focus on identification of risk factors for sexual offenses against children (see Whitaker et al., 2008). For example, Paquette and Cortoni (2021) found that offense-supportive cognition, sexual coping, and sexual interest in children predicted sexual offenses against children both online and offline. Each of these are represented in the DMV which is to be expected given that there were numerous individuals in the sample whose offenses targeted children. Comparatively, there are several developmental risk factors identified for paraphilias such as pedophilia and exhibitionism. These include childhood emotional and sexual abuse, behavioral problems, and family dysfunction (Lee et al., 2002). This mirrors some of those identified in the background factors of the DMV. However, the DMV provides further factors which may represent important treatment targets for men who have engaged in voyeuristic behavior. In addition, the model becomes more specific to voyeuristic behavior in the latter factors approaching the offense behavior. Though, it is important to note that it was not the purpose of the model to differentiate voyeurism from other offenses. Rather, it describes the patterns associated with voyeuristic behavior for this sample.

In addition to this, 88.24% (n = 15) of participants in the sample experienced at least one type of abuse. It is not uncommon to find high levels of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) among individuals in prison (Dallaire, 2007; Farringdon, 2000). However, this figure stands at around 29% for individuals in prison in the UK (Williams et al., 2012). Though, this is likely to be an underestimation due to the case file review technique used to obtain this data. Comparatively, one or more ACEs are reported for between 84.4% and 95.0% of individuals who have engaged with a sexual offense more widely (Khan et al., 2021; Levenson et al., 2016). This sample therefore mirrors that of individuals who have sexually offended, despite some participants stating non-sexual motivations for voyeuristic behavior.

As previously discussed, the MFM (Seto, 2008, 2019) posits that high sex drive, paraphilic interest, and intense mating effort may motivate an individual to engage with illegal sexual behaviors, such as voyeurism. The pathways indicated by the DMV both support the MFM and raises additional questions. The first pathway, Sexual Gratification, relates directly as individuals appeared to be driven by the sexual satisfaction from engaging in voyeuristic behavior. The second and third pathways, Maladaptive Connection-Seeking and Access to Inappropriate Person(s), could relate to what Seto terms intense mating effort or paraphilic interest if the victim was under the legal age of consent. However, the link is less convincing for instances outside of this. For example, there were many individuals largely driven by the adrenaline rush from the risk of doing something without being caught, emphasizing that there was no sexual gratification or that this was secondary to the thrill-seeking (i.e., Disorganized planners). Non-sexual motivations for sexual offenses, such as these, are a limitation to the MFM that Seto (2019) has discussed in-depth and one that requires exploration, particularly for voyeurism.

It is important to highlight that in order to generate the pathways, the same participants were plotted back through the model. The purpose of this was to examine the patterns occurring in the sample rather than to analyze and validate the model. It is therefore important for the model to be cross validated with additional samples that hold different demographics (e.g., non-incarcerated individuals, cross cultural samples). Nevertheless, the ability to validate offense-chain pathways is a core strength of grounded theory methodology as each model can be adapted, modified, and refined in response to new data (Gannon et al., 2010). It is recommended that the DMV follows suit.

As with all qualitative research, there is always an element of possible implicit researcher bias. This may have rooted from knowledge surrounding the sexual offending literature in addition to the researcher’s own experiences of the world. However, to minimize the impact, reliability checks were carried out by a researcher with no prior knowledge of this topic area. In addition, the analysis was overseen and spot checked from low-level category creation through to developing the temporal model. This, in conjunction with strict use of grounded theory principles is believed to have reduced these biases.

Methodologically, a limitation of this study is that it samples individuals convicted of (or could be convicted of) voyeurism and therefore may not be representative of all those engaging with this behavior. To illustrate, many of the participants were caught for voyeurism because of a further offense. Thus, this sample may be skewed towards individuals at the more serious end of the spectrum who are more likely to engage in contact offenses. This is a particularly important point to consider given the prevalence rates of voyeurism (of between 12.00-34.50%, e.g., Bártová et al., 2021; Joyal & Carpentier, 2017; Långström & Seto, 2006). However, (Seto et al., 2011) found that 55% of men who committed an online sexual offense also committed a contact offense, and Longo and Groth (1983) found that amongst a prison sample of individuals convicted of rape, 54% showed a history of voyeuristic behavior. Thus, it is likely that the people in our sample are similar to those who will be encountered by clinicians and as such this model is likely to be beneficial for identifying treatment targets and reducing recidivism. Further, the use of grounded theory allows for continuous modifications and adaptations following additional samples (noted by Gannon et al., 2008 and Polaschek et al., 2002), such as a community sample. Further research could also seek to validate the model with existing case studies in the literature such as those documented in Duff (2018).

In addition to this point, it is important also to consider the impact of the use of a legal definition in this study. This was of great strength for this model as it allowed all individuals whom a clinician may come across in a legal setting to be included, notwithstanding the utility for the logistics of recruitment from an incarcerated population. However, although the majority would, it is not certain that all participants would meet the clinical criteria for voyeurism under the DSM-5-TR (APA, 2022) due to the inclusive UK legal criteria (where individuals do not have to be suspecting). This was the reason for the use of the terminology ‘voyeuristic behavior’ rather than ‘voyeurism’ throughout, and therefore the implication of the findings should not be applied stringently to this population without further validation with additional samples.

Treatment Considerations

The pathways in the model allow clinicians to identify potentially key treatment targets to address with men engaging in voyeuristic behavior. These can be used to guide individual case formulation where engagement in voyeuristic behavior is an individuals’ primary offense or is their most serious offense pattern. This can then be used in addition to standardized, empirically supported sexual offending programs, if participants meet the criteria to attend these. It should be noted here, though, that the following are suggestions, based on the findings from the DMV, but are without empirical validation, and therefore should be treated as such.

For men on the ‘Sexual Gratification’ pathway, there were a number of potential treatment targets identified. The first, and specific to this pathway, is managing sexual urges. Individuals on this pathway were often driven by compulsive urges to engage in voyeuristic behaviors (primarily during challenging time periods) and as such, managing those would be of great use. The second, with overlap with individuals on the ‘Access to Inappropriate Person(s) pathway, is support with understanding and engaging in healthy sexual behaviors, as many individuals on this pathway were engaging in risky sexual behaviors.

For those on the ‘Maladaptive Coping Strategies’ pathway, specific to this pathway, was seeking emotional support. Many of the individuals on this pathway showed difficulties accessing the social support network they had available to them, if at all. This may be reflected by difficulties with mental health, developing and maintaining friendships, or emotional closeness with others. As such, support with accessing social support from pro-social individuals would be of use. Furthermore, developing maladaptive coping strategies was a strong theme among these individuals (and all participants to some degree) and should be reflected upon accordingly.

Lastly, for individuals on the ‘Access to Inappropriate Person(s)’ pathway, the most integral treatment target for these individuals was managing sexual thoughts. Often, individuals on this pathway had sexual thoughts about individuals with whom they could not enter a sexual relationship with which, in combination with other factors, led to engagement in voyeuristic behavior. As such, managing these thoughts so that they do not formulate an offense-related script, would be of use for these individuals. Similarly, for many individuals on this pathway, there was an associated inappropriate sexual interest. Support through meeting their sexual desires in a healthy and consensual way would be beneficial.

For all three pathways, it was clear that support with developing and maintaining healthy intimate relationships was needed. All participants in the sample showed some deficit in this area. For example, those seeking intimate relationships from adolescents demonstrated difficulties with intimacy with adults and understanding consent when developing these into sexual relationships due to their age. On the other hand, many of those in intimate relationship with adults had difficulties understanding consent within an adult relationship or felt dissatisfied in those relationships albeit emotionally or sexually. Furthermore, although transpiring differently in each pathway, all participants showed difficulties with developing adaptive coping strategies and seeking social support (even if they had it available to them) and as a result, used unhealthy sexual behaviors to cope (which later led to voyeuristic engagement). As such, addressing this would be of use for these individuals.

It is essential to reiterate here that these treatment targets, in addition to the risk factors identified in the DMV, need empirical validation prior to widespread clinical usage.

Conclusion

In conclusion, to our knowledge, the DMV is the first offense-chain model developed to describe voyeuristic behavior. Utilizing grounded theory methodology, this preliminary model has been created based on information and knowledge from men who have engaged in voyeuristic behaviors. The DMV shows considerable scope to begin the important work needed on voyeurism, amid the paucity of theoretical and empirical research. This model provides detailed information on the affective, cognitive, behavioral, and contextual factors as well as post-offense factors on what leads to individuals to engage in voyeuristic behavior. Further, it is sensitive enough to provide suggested treatment targets for individual case formulation use by clinicians. However, further research should seek to validate this model, providing adaptations where needed, in addition to other proposed suggestions to ensure evidence-based practice for clinicians working with men engaging in voyeuristic behaviors.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank Rachel Tisi and Sarah Kelleher for their comments on the analytic process conducted as part of this project, staff at the participating prisons, and all our participants for sharing their experiences with us. We would also like to express our gratitude to Caoilte Ó Ciardha for his comments on an earlier draft of this manuscript. Views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of HMPPS.

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The work was supported by University of Kent; Studentship and studentship granted to the corresponding author.

ORCID iDs

Victoria P. M. Lister https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1314-7901

Theresa A. Gannon https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5810-4158

References

- Abel G. G., Becker J. V., Mittelman M., Cunningham-Rathner J., Rouleau J. L., Murphy W. D. (1987). Self-reported sex crimes of nonincarcerated paraphiliacs. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 2(1), 3–25. 10.1177/088626087002001001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Author. [Google Scholar]

- Babchishin K. M., Hanson R. K., Vanzuylen H. (2015). Online child pornography offenders are different: A meta-analysis of the characteristics of online and offline sex offenders against children. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 44(1), 45–66. 10.1007/s10508-014-0270-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnoux M., Gannon T. A., Ó Ciardha C. (2014). A descriptive model of the offence chain for imprisoned adult male firesetters (descriptive model of adult male firesetting). Legal and Criminological Psychology, 20(1), 48–67. 10.1111/lcrp.12071 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bártová K., Androvičová R., Krejčová L., Weiss P., Klapilová K. (2021). The prevalence of paraphilic interests in the Czech population: Preference, arousal, the use of pornography, fantasy, and behavior. Journal of Sex Research, 58(1), 86–96. 10.1080/00224499.2019.1707468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beech A. R., Elliott I. A., Birgden A., Findlater D. (2008). The internet and child sexual offending: A criminological review. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 13(3), 216–228. 10.1016/j.avb.2008.03.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blagden N., Winder B., Gregson M., Thorne K. (2014). Making sense of denial in sexual offenders: A qualitative phenomenological and repertory grid analysis. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 29(9), 1698–1731. 10.1177/0886260513511530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chouhy C., Cullen F. T., Lee H. (2020). A social support theory of desistance. Journal of Developmental and Life-Course Criminology, 6(2), 204–223. 10.1007/s40865-020-00146-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cox D. J., Maletzky B. M. (1980). Victims of exhibitionism. In Cox D. J., Daitzman R. J. (Eds.), Exhibitionism: Description, assessment, and treatment (pp. 289–293). Garland STM Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dallaire D. H. (2007). Incarcerated mothers and fathers: A comparison of risks for children and families. Family Relations, 56(5), 440–453. 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2007.00472.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- de Vries Robbé M., Mann R. E., Maruna S., Thornton D. (2015). An exploration of protective factors supporting desistance from sexual offending. Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment, 27(1), 16–33. 10.1177/1079063214547582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle T. (2009). Privacy and perfect voyeurism. Ethics and Information Technology, 11(3), 181–189. 10.1007/s10676-009-9195-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Duff S. (2018). Voyeurism: A case study. Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott I. A., Beech A. R., Mandeville-Norden R. (2013). The psychological profiles of internet, contact, and mixed internet/contact sex offenders. Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment, 25(1), 3–20. 10.1177/1079063212439426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott I. A., Beech A. R., Mandeville-Norden R., Hayes E. (2009). Psychological profiles of internet sexual offenders: Comparisons with contact sexual offenders. Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment, 21(1), 76–92. 10.1177/1079063208326929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrington D. P. (2000). Psychosocial predictors of adult antisocial personality and adult convictions. Behavioral Sciences & the Law, 18(5), 605–622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D. (1984). Child sexual abuse: New theory and research. The Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gannon T. A., Rose M. R., Ward T. (2008). A descriptive model of the offense process for female sexual offenders. Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment, 20(3), 352–374. 10.1177/1079063208322495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gannon T. A., Rose M. R., Ward t. (2010). Pathways to female sexual offending: Approach or avoidance? Psychology, Crime & Law, 16(5), 359–380. 10.1080/10683160902754956 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gebhard P. H., Gagnon J. H., Pomeroy W. B., Christenson C. V. (1965). Sex offenders. Harper & Row. [Google Scholar]

- Given L. M. (2015). 100 questions (and answers) about qualitative research. SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Gold C. (2017). Non-Contact Sex Offenders and Public Perception The Importance of Victim Type and Crime Location. [Master’s thesis, City University of New York], CUNY Academic Works. https://academicworks.cuny.edu/jj_etds/40 [Google Scholar]

- Gordon-Finlayson A. (2010). Grounded theory. In Forrester M. A. (Ed.), Doing qualitative research in Psychology: A practical guide (pp. 154–176): SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Helmus L., Hanson R. K., Babchishin K. M., Mann R. E. (2013). Attitudes supportive of sexual offending predict recidivism: A meta-analysis. Trauma, Violence & Abuse, 14(1), 34–53. 10.1177/1524838012462244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry N., Powell A. (2018). Technology-facilitated sexual violence: A literature review of empirical research. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 19(2), 195–208. 10.1177/1524838016650189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hocken K., Thorne K. (2012). Voyeurism, exhibitionism and other non-contact sexual offences. In Winder B. E., Banyard P. E. (Eds.), A psychologist’s casebook of crime: From arson to voyeurism (pp. 243–263): Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Joyal C. C., Carpentier J. (2017). The prevalence of paraphilic interests and behaviors in the general population: A provincial survey. Journal of Sex Research, 54(2), 161–171. 10.1080/00224499.2016.1139034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn R. E., Jackson K., Keiser K., Ambroziak G., Levenson J. S. (2021). Adverse childhood experiences among sexual offenders: Associations with sexual recidivism risk and psychopathology. Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment, 33(7), 839–866. 10.1177/1079063220970031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan M. S., Krueger R. B. (1997). Voyeurism: Psychopathology and theory. In Laws R. D., O’Donohue W. (Eds.), Sexual deviance: Theory, assessment and treatment (pp. 297–310): Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kar N., Koola M. M. (2007). A pilot survey of sexual functioning and preferences in a sample of English-speaking adults from a small South Indian town. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 4(5), 1254–1261. 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2007.00543.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Långström N., Seto M. C. (2006). Exhibitionistic and voyeuristic behavior in a Swedish national population survey. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 35(4), 427–435. 10.1007/s10508-006-9042-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. K. P., Jackson H. J., Pattison P., Ward T. (2002). Developmental risk factors for sexual offending. Child Abuse & Neglect, 26(1), 73–92. 10.1016/S0145-2134(01)00304-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levenson J. S., Willis G. M., Prescott D. S. (2016). Adverse childhood experiences in the lives of male sex offenders: Implications for trauma-informed care. Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment, 28(4), 340–359. 10.1177/1079063214535819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis R., Anitha S. (2022). Upskirting: A systematic literature review. Trauma, Violence and Abuse, Advance Online Publication. 10.1177/15248380221082091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longo R. E., Groth A. N. (1983). Juvenile sexual offenses in the histories of adult rapists and child molesters. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 27(2), 150–155. 10.1177/0306624x8302700207 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- MacPherson G. J. (2003). Predicting escalation in sexually violent recidivism: Use of the SVR-20 and PCL: SV to predict outcome with non-contact recidivists and contact recidivists. Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology, 14(3), 615–627. 10.1080/14789940310001615470 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mann R. E., Ainsworth F., Al-Attar Z., Davies M. (2008). Voyeurism: Assessment and treatment (p 320–335). In Laws D. R., O’Donohue W. T. (Eds.), Sexual deviance: Theory, assessment and treatment (2nd ed., pp. 320–335): Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- McAnulty R. D., Adams H. E., Dillon J. (2001). Sexual deviation: Paraphilias. In Sutker P. B., Adams H. E. (Eds.), Comprehensive handbook of psychopathology (3rd ed., pp. 749–773): Kluwer Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Paquette S., Cortoni F. (2021). Offence-supportive cognitions, atypical sexuality, problematic self-regulation, and perceived anonymity among online and contact sexual offenders against children. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 50(5), 2173–2187. 10.1007/s10508-020-01863-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polaschek D. L., Ward T. (2002). The implicit theories of potential rapists: What our questionnaires tell us. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 7(4), 385–406. 10.1016/s1359-1789(01)00063-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Polaschek D. L. L., Hudson S. M., Ward T., Siegert R. J. (2001). Rapists’ offense processes: A preliminary descriptive model. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 16(6), 523–544. 10.1177/088626001016006003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Raymond N. C., Grant J. E. (2008). Sexual disorders: Dysfunction, gender identity, and paraphilias. In Fatemi S. H., Clayton P. J. (Eds.), The medical basis of psychiatry (pp. 267–283). Humana Press. 10.1007/978-1-59745-252-6_16 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rye B. J., Meaney G. J. (2007). Voyeurism: It is good as long as we do not get caught. International Journal of Sexual Health, 19(1), 47–56. 10.1300/J514v19n01_06 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schlesinger L. B., Revitch E. (1999). Sexual burglaries and sexual homicide: Clinical, forensic, and investigative considerations. The Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law, 27(2), 227–238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seto M. C. (2008). Pedophilia and sexual offending against children: Theory, assessment, and intervention: American Psychological Association. 10.1037/11639-000 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Seto M. C. (2013). Internet sex offenders: American Psychological Association. 10.1037/14191-000 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Seto M. C. (2019). The motivation-facilitation model of sexual offending. Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment, 31(1), 3–24. 10.1177/1079063217720919 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seto M. C., Hanson R. K., Babchishin K. M. (2011). Contact sexual offending by men with online sexual offenses. Sexual Abuse, 23(1), 124–145. 10.1177/1079063210369013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sexual Offences Act (2003). c. 42. https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2003/42 [Google Scholar]

- Simon R. I. (1997). Video voyeurs and the covert videotaping of unsuspecting victims: Psychological and legal consequences. Journal of Forensic Sciences, 42(5), 14224J–14889J. 10.1520/jfs14224j [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith R. S. (1976). Voyeurism: A review of literature. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 5(6), 585–608. 10.1007/bf01541221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss A., Corbin J. (1998). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (2nd ed.): Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson C. (2019). Everyday misogyny: On ‘upskirting’ as image-based sexual abuse [Doctoral thesis]. University of Melbourne. http://hdl.handle.net/11343/224155 [Google Scholar]

- Tyler N., Gannon T. A., Lockerbie L., King T., Dickens G. L., De Burca C. (2014). A firesetting offense chain for mentally disordered offenders. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 41(4), 512–530. 10.1177/0093854813510911 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ward T., Beech A. R. (2017). The integrated theory of sexual offending—revised: A multifield perspective. In Boer D. P. (Ed.), The Wiley handbook on the theories, assessment and treatment of sexual offending (pp. 123–137). John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Ward T., Louden K., Hudson S. M., Marshall W. L. (1995). A descriptive model of the offense chain for child molesters. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 10(4), 452–472. 10.1177/088626095010004005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ward T., Polaschek D. L. L., Beech A. R. (2006). Theories of sexual offending. Wiley. [Google Scholar]