Abstract

In this work, open or closed air cavity (air bubble) inclusion structures are 3D printed via direct ink writing and fused deposition modeling methods utilizing materials of polydimethylsiloxane silicone or thermoplastic polyurethane, respectively, and these structures are examined for their attenuation capacity concerning ultrasonic waves in underwater environment. It is found that several factors, such as interstitial fencing layer, air cavity fraction, material interface interaction, and material property, are fundamental elements governing the overall attenuation performance. Hence, via 3D printing technique, which could conveniently manipulate structure's cavity volume fraction, such as via filament size and filament density on surface, structures with tunable attenuation could be designed. In addition, considering directions where ultrasound would encounter interfaces, that is, if the geometry could induce more interface interactions, such as triangular shape compared with simple square, it is possible to obtain immense attenuation enhancement, which does pave an additional approach for attenuation optimization via convoluted structural interface design that is exclusively tailored by additive manufacturing.

Keywords: 3D printing, additive manufacturing, attenuation structure, cavity fraction, transmission direction

Introduction

Acoustically related pollutions, either audible noise or intangible ultrasound, have been posing chronical and tremendous impacts on human health,1–3 environment, and ecology.4 For instance, excessively high intensity of noise may arouse stress and potential hearing impairment. In addition, undiscernible exposure to ultrasound beyond safety standard may lead to unexpected internal body injuries such as lung or intestine hemorrhage and cell destruction.1–3 Besides, ultrasound sources, which are commonly utilized for Sound Operation Navigation And Range system and echolocation, have been reported to jeopardize ocean species and corresponding ecological maintenance.4 Hence, it would be critically important to curb such detriments via noise absorption or acoustic blocking, especially in underwater environment.

For conventional acoustic absorbers based on porous structures, especially structures with interconnected open pores, which could reduce acoustic energy via frictional and viscous thermal loss, has to obey a mass law that dictates the need for bulky and thick absorbers to achieve efficient absorption. In this case, the porous materials' thickness needs to be at least 10% in scale of related sound wavelength to obtain a relatively decent sound attenuation.5–7 Hence, it would be of immense significance to circumvent this bulky absorber requirement. To achieve so, aided by additive manufacturing techniques, researchers have been intensively conducting investigations and refinement on acoustic metamaterials, which are endowed with both high absorption coefficient and wide bandgap, via either convoluted structural design or localized resonance incorporation.

Among these enormous efforts, Fotsing et al.,8 Vasina et al.,9 and Aslan and Turan10 utilized additive manufacturing to fabricate acoustic metamaterials based on periodic lattice microstructures with variant layer orientations, structures, and pore interactivity (the degree of pore interconnection) and scrutinized their performances at relatively low acoustic frequencies. These works provided ingenious insights into elements dominating acoustic metamaterial performance, such as orientation-related air path tortuosity,8 combinational influence of structure, absorber thickness, and backing air gap with frequency dependency,9 and moderate level of pore interactivity for absorption enhancement.10

These aforementioned paradigms and examples, although highly effective in sound absorption, are highly dependent on sophisticated design of inner structures, which could somehow increase the difficulty in manufacturing. In addition, although open porous structures are widely used for acoustic absorption, especially with interconnected pores to allow wave transmission through the structures, in which wave and air have interactions to reduce acoustic energy, these open pore structures may not provide ultrasound attenuation in underwater environment as efficiently as closed pores, due to liquid penetration which may facilitate ultrasound transmission.11 Besides, these metamaterials still may not supersede their counterparts in nature, such as bubbles with Minnaert resonance in fluid, which could effectively absorb acoustic waves at wavelengths up to 500 times the bubble size.12

Hence, acoustic metamaterials that require relatively simple design and exhibit wide frequency compatibility for audible and ultrasonic acoustic waves have become a demanding challenge. To circumvent this issue, researchers have been riveted on bubble resonance, hoping to harness the featured advantage of Minnaert resonance with periodic lattice arrangement to attain high-performance multifrequency domain attenuation.13 However, although air bubbles could be trapped underwater, yet they would be rendered unstable in the presence of environmental influences such as vibration or flowing currents in liquids.

To obviate the major difficulty in efficiently maintaining bubbles in fluidic environment, Leroy and his team utilized sufficiently soft elastomeric materials with bubble inclusion to successfully mimic the natural bubble absorption phenomenon.14 The cornerstone to their success was that, when elastomeric matrix has exceedingly low shear modulus compared with air longitudinal modulus, the effect of replacing fluid with elastomer could be treated as almost negligible.14,15 Based on this low shear modulus material replacement trait, the group ingenuously obtained both bubble resonance and acoustic wave scattering in their bubble-inclusion phononic crystals, via stacking spin-coated polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) layers with cavities, which eventually achieved multi-peak wide bandgap acoustic absorption.12,16,17

Leroy's method, although an ingenious work, yet still has several aspects that could be addressed and explored. For instance, the bubbles were of identical sizes and the pore geometry was relatively simple. In addition, the stacked PDMS layers were not of identical thickness, which might not provide a sound and convincing solution as per the issue to enhance sound/ultrasound absorption within a limited material thickness. Besides, the normal stacking of disparate PDMS layers may not ensure the intact structure. This means that possible interference might also be introduced when adjacent layers contain undesired gaps in between, forming possible spots for unknown scattering, if any.

Hence, in this work, we 3D printed silicone viscoelastic ink and thermoplastic polyurethane (TPU) filaments into various air cavity inclusion structures, with the objective to find and evaluate dominating factors, such as interstitial fencing layer, air cavity fraction, material interface interaction, and material property, which may govern these structures' acoustic performance. Since lattice arrangements of periodicity have already been shown to possibly obtain low-frequency absorption,8,9,18 as well as on account of convenience to portray ultrasonic wave behavior via oscilloscopes, the investigation was mainly focused on structures' corresponding underwater ultrasound attenuation capacity.

In addition, unlike mainstream research on 3D printed attenuation structures, which focuses generally on material, geometry, cavity fraction, and cell interconnection, this work also explored ultrasound transmission direction with regard to structural geometry of same relative density. Moreover, a general relationship about attenuation enhancement and pressure control in 3D printing technique was also projected, making it convenient to directly design 3D printed ultrasound attenuation devices via such control to cater to specific attenuation needs in application, which to the best of authors' knowledge is relatively rare in recent study of the field. This feature of the investigation may provide insights into underwater ultrasonic attenuation management via 3D printing technique manipulation.

Materials and Methods

Sample preparation

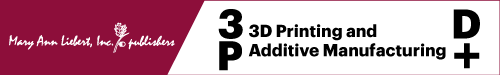

To prepare the direct ink writing (DIW) viscoelastic ink, the base and curing agent of silicone PDMS SE1700 were mixed with mass ratios of 10:1 in planetary stirrer (ZYE Technology Co., Ltd). After a homogeneous mixture was obtained, the silicone ink was loaded into a syringe with subsequent centrifugation to remove bubbles. When bubble removal was completed, the syringe was capped with extruder nozzle (0.34 mm diameter) and then placed onto a homemade DIW platform. The platform, equipped with a pressure adaptor (Performus X100; Nordson EFD), could be controlled by computer programs to execute x-, y-, and z-axis directional movement, during which ink extrusion due to appropriate pressure could yield filaments depositing on substrate, consequently forming 3D structures in an additive manner, as portrayed by photo in Figure 1a.

FIG. 1.

(a) Photo of direct ink writing platform. (b) The breached sample whose surface has bulges and distortion due to heat curing process. (c–f) The schematics of printed structure. (g) Photo of closed cell sample (1FC). (h) Photo of through-hole specimens, from left to right PDMS square, PDMS triangular, soft TPU square, soft TPU triangular, hard TPU square, and hard TPU triangular. PDMS, polydimethylsiloxane; TPU, thermoplastic polyurethane.

To characterize filament size with regard to print parameters of air pressure and nozzle translocation speed, single straight lines were printed with combination of various speeds and pressure settings for six layers on glass substrates and were then placed under 3D laser microscopes for filament width inspection. With this filament size control parameters determined, appropriate print parameters were selected for structure printing. The printed structures and geometry with air cavity inclusions are demonstrated by the schematics in Figure 1c–f, and they are labeled after nFC, in which n denotes the number of interstitial fencing layer within the structure, for example, 0FC for schematic in Figure 1c and 1FC for Figure 1d.

It should be noted that to keep the same sample total thickness (since total thickness could influence acoustic wave absorption) before and after adding interstitial fencing layer, one original layer involving air cavity would have to be replaced by solid sealing layer, which means 1FC would indeed have cavity layer one less than 0FC, that is, 14 layers versus 15 layers. Thus, to analyze structures concerning similar cavity fraction, an extra “1FC-7-8,” which means above and below the fencing interface are seven and eight layers of air cavity instead of equal seven layers in normal 1FC, was also printed for ultrasound property comparison. The reason and need for such supplementary sample preparation would be also further addressed in the Results and Discussion section.

These specimens were then placed under room temperature for 24 h for pre-curing and then 80°C for 2 h for complete thermal curing. This two-step curing process was adopted to prevent cavity shape distortion due to thermal expansion upon heat. Before the PDMS ink is completely cured, the printed structure is prone to distortion and disfigure caused by any external force or abrasion. Specifically, upon heat, inner pressure inside the enclosed cavity would brusquely increase, causing the inside air to expand, which would bulge or even breach the structure surface, as shown in Figure 1b. In this case, the specimen would lose intactness, with minor holes on cavity sealing layer, which are susceptible to water leakage during underwater testing. Figure 1g shows an example of intact closed-cell 1FC sample.

For supplementary samples (structures in Fig. 1e, f) requiring identical filament size with minimal variation for study concerning relative density, curing inhibitor 1–3 butanol was added in former ink recipe with mass ratio of 10% with respect to curing agent. These cure-inhibited specimens consequently underwent 80°C thermal curing. The reason for this direct 80°C thermal curing is that with 1–3 butanol added, under room temperature, PDMS would then take more than 1 week to cure, immensely lengthening expected sample preparation time. To study influence of material selection on ultrasound attenuation performance, samples of same dimension 36 × 36 × 15 mm and relative density but different materials (i.e., PDMS and TPU) were fabricated via DIW and fused deposition modeling (FDM), respectively, as shown in Figure 1h. In addition, TPU-based specimens with dimensions 36 × 36 × 30 mm were also printed for in-plane and out-of-plane measurements (for details concerning these two measurement modes, please refer to the Ultrasound Measurement section).

Ultrasound measurement

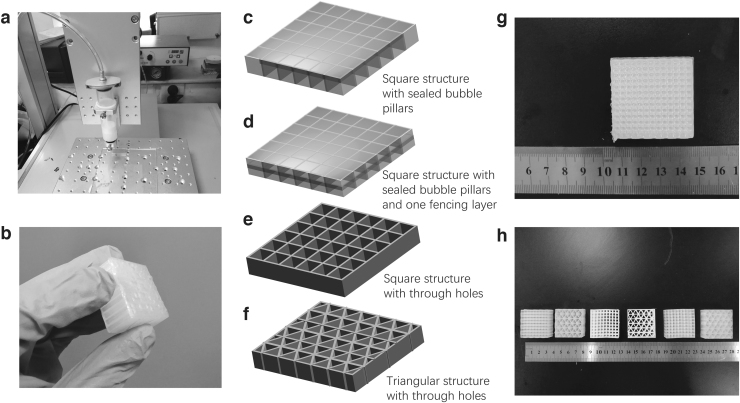

The samples' ultrasound attenuation capability was characterized via underwater acoustic transmission measurement, in which the sample was immersed in a tank filled with water and an ultrasound pulse generator/receiver (CTS 8077PR) was connected with a pair of transducers (1Z20SJ; SIUI, China), which would generate ultrasonic plane waves and also detect transmitted signal intensity, respectively. These two transducers, whose central frequency was at 1 MHz, were also immersed and aligned parallel to sample's z-axis, as shown by schematics and photo in Figure 2a and b, respectively. In this way, ultrasonic wave would transmit the sample and reach the reception detector.

FIG. 2.

(a, b) The schematic and photo of underwater ultrasound transmission test with transducers placed 4 cm apart. (c, d) The ultrasound transmission direction in-plane and out-of-plane. (e, f) Two directions of triangular structure in-plane test.

For transmission, as shown by Figure 2c and d, two transmission directions of out-of-plane and in-plane were employed. In addition, for triangular geometry in-plane mode, directions of Triangle 1 and Triangle 2 were involved, with which the former incorporated more interface interactions (i.e., wave encounters more PDMS interfaces), as shown in Figure 2e and f. During the measurement, an oscilloscope was employed to display the ultrasound intensity after wave transmission through samples and the ultrasound source was set at −10 dB for appropriate signals. This dB adaptation is an in-built element in ultrasound pulse generator/receiver to process received signal by either enhancing or reducing intensity.

After several measurement trials with various dB selection, it was found that −10 dB could eliminate majority of undesirable signal noise. In addition, to verify this underwater ultrasonic measurement accuracy, measurements concerning water and aluminum plates of different thickness were also performed, in which corresponding speed of wave and wave travel time consistency were verified (see Supplementary Data for details of calculation and consistency check). In addition, fast Fourier transformation (FFT) function was also applied in oscilloscopes, and by calculating the ratios between FFT signals of water and specimens, transmission coefficient spectrum could be obtained.12

Results and Discussion

Filament size and printed structures

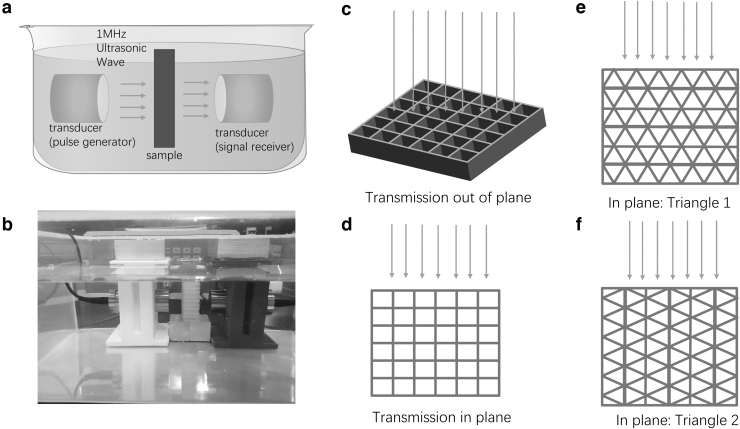

The relationships among filament size, pressure, and print speed for inks with or without curing inhibitor are portrayed in Figure 3, which in general shows a trend of filament width reduction related to increased speed and reduced pressure. Moreover, at the minimal pressure (15 psi for inhibitor ink and 30 psi for non-inhibitor ink), filaments could not be well formed when speed was set fast (7 or 8 mm/s) as the amount of ink deposited could not match the nozzle movement to yield uniform lines. Considering the need to print intact structures as well as to save ink material, print speeds neither too fast nor too slow would not be recommended, and hence, 6 mm/s was selected for all specimen fabrication.

FIG. 3.

The filament width in relation to print speed and print pressure for ink recipe with (a) and without (b) inhibitor (1–3 butanol).

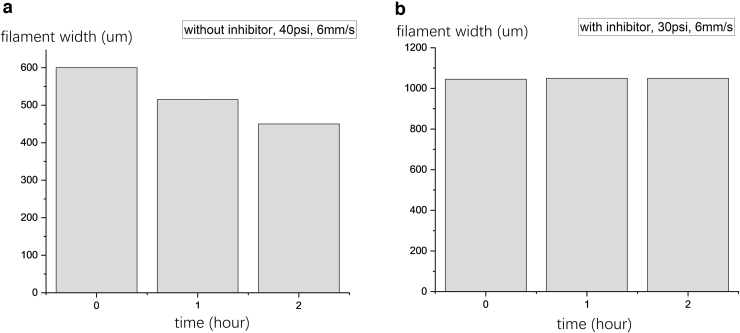

In addition, it could be clearly observed that at the same speed setting, it would require at least twice as large the pressure to obtain filament width of similar scale for the ink without inhibitor. This is likely because when inhibitor is added, it could relatively reduce ink viscosity, facilitating ink extrusion. Besides, inhibitor could prevent ink curing, making it possible to retain ink rheology condition, so that filament width production could be maintained with identical results without the need to re-adjust print pressure. This is further proved by results concerning both ink's filaments that are printed after every hour in Figure 4, which shows that unlike its counterpart, non-inhibitor ink filament would undergo evident size reduction of around 15% after each hour.

FIG. 4.

The filament width in relation to time prolonging for ink without (a) and with (b) inhibitor.

For the printed structures, filament sizes were examined and recorded in Table 1. Based on this filament size information and programmed filament spacing (3 mm), the volume fraction of air cavity, or porosity, in each specimen could be estimated. To do so, since specimens resemble a basic cubic contour, it is convenient to use the ratio between air volume and total sample bulk volume, which could both be obtained by product of relevant area and height. Considering that each printed layer was of same thickness, it could be simplified as in Equation (1):

Table 1.

The Summary and Grouping of Filament Sizes and the Attenuation of Ultrasound Signal for Solid Polydimethylsiloxane Layer, and Various Printed Samples, with dB Reference to Water

| Specimen | Solid | 0FC | 1FC | 1FC-7-8 | 2FC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample filament size | |||||

| Average size (μm) | NA | 486.32 | 479.51 | 464.08 | 426.99 |

| Size range (μm) | NA | 475 ± 11 | 426 ± 11 | ||

| No. of cavity layers | NA | 15 | 14 | 15 | 15 |

| Cavity fraction | NA | 0.62 | 0.58 | 0.60 | 0.58 |

| Attenuation of all samples (dB) | |||||

| Run 1 | 33.77 | 23.81 | |||

| Run 2 | 31.48 | 22.14 | |||

| Run 3 | 32.19 | 23.10 | |||

| Run 4 | 6.45 | 31.88 | 23.48 | ||

| Run 5 | 7.56 | 34.84 | 23.91 | 39.52 | 46.88 |

| Run 6 | 8.10 | 33.60 | 23.37 | 37.82 | 43.84 |

| Run 7 | 3.06 | 32.96 | 22.96 | 37.82 | 43.84 |

| Average | 6.29 | 32.96 | 23.25 | 38.39 | 44.85 |

NA, not applicable.

| (1) |

in which fsp stands for filament spacing, fw means filament width, A denotes sample base area, n represents number of cells in each layer, and L and H refers to the number of layers for cavity layer and sample total layer, respectively. These samples' cavity fractions are also shown in Table 1. Due to minor variation in filament sizes, these cavity fractions would contain fluctuations within 1% difference. This filament size variation is likely due to the inhibitor absence in ink recipe, as already discussed earlier. Although such cavity fraction fluctuation exists, it is still possible to obtain trends concerning ultrasonic attenuation among these specimens in the section Intensity Data Analysis of Measurement Runs.

Intensity data analysis of measurement runs

Attenuation concerning interstitial fencing layer

By directly referring to the oscilloscope's user interface front panel, values of transmitted ultrasound signal intensity could be retrieved from the screen. After the data acquisition, the ultrasound intensity attenuation could be calculated according to Equation (2):5

| (2) |

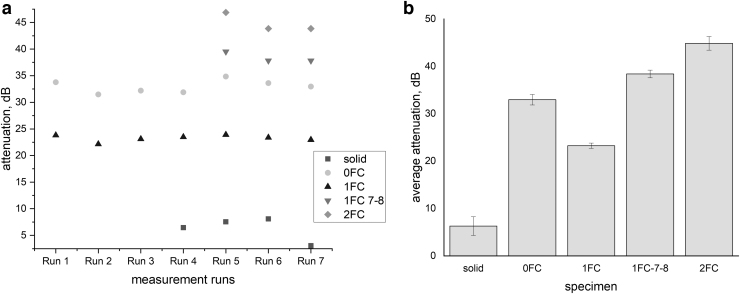

where Ps denotes the signal with sample insertion, Pw denotes just water without samples, and atten dB denotes attenuation in unit of decibel. Table 1 lists all calculated attenuation results based on retrieved signal intensity. For all these calculated attenuations (dB), concerning each individual sample, data stay consistent, featuring minor fluctuations around a constant value, as portrayed in Figure 5. By checking the average of attenuations in Figure 5b, first and foremost, it can be obtained that air cavity embedment could enhance attenuation in PDMS, as corroborated by attenuations in samples pure solid and 0FC, in which on average, the latter supersedes the former by at least five times. This significant increase is due to increased acoustic impedance mismatch between air and solid materials, enabling abundant acoustic reflection.11,19,20 Such acoustic wave reflection, in details, arises at boundaries of media in different materials, which would usually follow a pattern of more impedance mismatch, greater reflection, as described in Equation (3):20,21

FIG. 5.

(a) The attenuation measurements with reference to water for PDMS specimens. (b) The average attenuations with reference to water for PDMS specimens.

| (3) |

In this equation, R denotes reflectivity, whereas Z1 and Z2 stands for acoustic impedances of original and newly entered media, respectively. To calculate a material's impedance, one could use the relationship between sound velocity (c), material density (ρ), and impedance (Z), as described in Equation (4):20,21

| (4) |

Based on calculations of corresponding wave impedance and reflectivity in Tables 2 and 3, it can be shown that reflection at air/PDMS boundary is higher than that at PDMS/water interface by approximately eightfolds.

Table 2.

Numerical Value for Speed of Sound, Density, and Impedance Concerning Polydimethylsiloxane, Water, and Air

Table 3.

Reflectivity for Interface Boundary Involving Water, Polydimethylsiloxane, and Air

| Water-PDMS | PDMS-air | Air-PDMS | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reflectivity | 13.346% | 99.927% | 99.927% |

In addition, concerning the effect of interstitial fencing layer, among relevant specimens, 0FC outperforms 1FC by around 9 dB. However, it should be noticed that 0FC has one more air layer than 1FC (total of 15 layers vs. 14 layers), and these samples have cavity fraction difference up to 4%. To ensure the comparison within the same scope of 15 layers, 0FC and 1FC-7-8 were then compared, showing attenuations in the same order of scale above 30 dB. In addition, 1FC-7-8 attenuation is generally larger than its counterpart by at least 5 dB (around 20% increase), indicating that adding interfaces would contribute to attenuation enhancement.

This indication is further supported by attenuation comparisons among specimens 1FC, 1FC-7-8, and 2FC, in which the latter outnumbers the former two by at least 11 dB (47%) and 6 dB (16%), respectively. As for the relatively large 47% increase in attenuation from 1FC to 2FC, it is highly suspected that the 4% difference in cavity fraction promotes much more attenuation. In addition, although it is true that cavity fractions were not exactly the same in 1FC-7-8 and 2FC, due to the filament change phenomenon discussed in prior section, this minor difference of 2% still may not render the conclusion concerning interstitial fencing layer as fallacious or dubitable. This is because 2FC has less cavity fraction but yet higher attenuation, indicating the contribution by its extra fencing layer. Nonetheless, it is still necessary to inspect the influence of cavity fraction by measuring specimens with same or different cavity fraction, which would be discussed in the section Concerning Relative Density.

Concerning relative density

To further study the effect regarding air volume fraction, or in other words, porosity or relative density, PDMS structures with same relative density of 0.37, whose pores are periodic through holes with square and triangular structures, as well as one 0.49 relative density square structure, were also tested under water. As already stated in the Materials and Methods section, due to the need for filaments of same size to keep identical relative density in all specimens, a different PDMS ink recipe and corresponding thermal curing process were utilized, which made it impossible to fabricate the same cavity enclosed structure. Hence, these specimens would not have sealing layers at top and bottom to enclose fixed air cavities and upon submersion in water, air in the pores would be replaced by water, forming bicomponents of PDMS and water.

Although this causes change of underwater components, the results could still provide indications concerning effects posed by volume fraction of pores and PDMS. In addition, testing with this structure could also offer a sole focus on volume fraction, excluding any impacts of reflection caused by water/air impedance mismatch interface. These through-hole PDMS samples with ultrasound wave traveling in out-of-plane direction show similar attenuation results around −11 dB for specimens with same 0.37 cavity fraction, and an increased 13.74 dB for the remaining high relative density specimen. First and foremost, for low relative density samples with different lattice cell geometry, although in different medium composition, that is, PDMS/water other than prior PDMS/air, and although in this case, PDMS becomes a major source of attenuation based on ultrasonic absorption instead, the attainment of same attenuation capacity with respect to same relative density, indicates that relative density is also a highly dominating factor in tailoring ultrasound attenuation.

Moreover, the denser triangle structure with 12% relative density increase shows increased attenuation by 25%, which seems to contradict prior discussion about attenuation increase enabled by cavity fraction increase. However, it should be noticed that in this case where air cavity is filled with water to facilitate ultrasound transmission, PDMS is indeed the source of attenuation based on its ultrasonic absorption. This means that when fraction of components impeding ultrasonic wave is increased (prior case, air cavity, and this case, PDMS material weight percentage), attenuation could be enhanced. In addition, to further justify these results based on alternative use of PDMS/water composition, additional out-of-plane test involving PDMS/air composition was also performed on 0.37 relative density samples.

In this test, since original setup with 4 cm apart transducers could not detect signal due to air's impeding effect on ultrasound, transducers were coated with ultrasound coupling agent and then placed in direct contact with sample surface. For reference material, pure PDMS block was utilized. This test's results also exhibited similar dB attenuation, namely −19.39 dB for square structure and −18.96 dB for triangular structure. This corroborates that cavity fraction could serve as a dominating factor in attenuation, and it could be speculated that for out-of-plane direction ultrasonic attenuation, when relative density is kept identical and impedance mismatch reflection is excluded, attenuation could also be identical regardless of porous structure geometry.

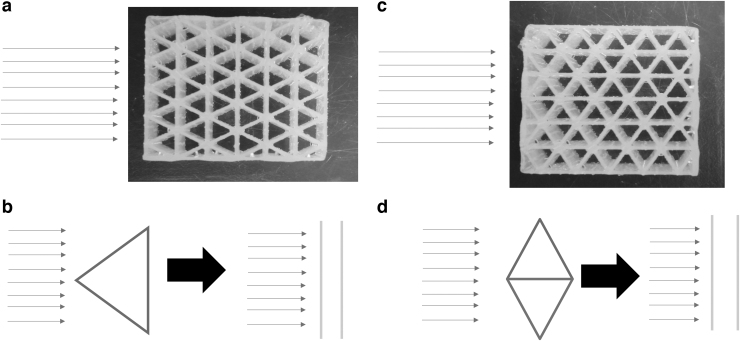

Concerning ultrasonic wave propagation direction

Furthermore, to implement prior finding, in-plane direction measurements were also performed involving FDM-printed 3 cm-thick TPU samples with same relative density. For these TPU samples, both out-of-plane and in-plane mode ultrasound transmission tests were performed. In these measurements, the out-of-plane test obtained similar attenuation for both square and triangular structures, around −10 dB, further reconfirming the prior argument concerning relative density. However, in the other measurement direction, heterostructure shows prominent influence, in which triangular outperforms square by at least 10 dB, as shown in Table 4. In addition, the Triangular 1 direction, which holds one more equivalent wave interaction interface layers than Triangular 2 (shown in Fig. 6), gives attenuation nearly 20% more than the latter. This means more complex structures with more interfaces would induce more attenuation. The major mechanism for this enhancement lies in the interaction with these impedance mismatch interfaces that promote ultrasonic wave reflection.

Table 4.

The Thermoplastic Polyurethane Sample Attenuation of 1 MHz Ultrasound with Reference to Water, Measured In-Plane Direction

| Attenuation of all samples (dB) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Square | Triangle 1 | Triangle 2 | |

| Run 1 | −20.75 | −35.59 | NA |

| Run 2 | −21.21 | −35.69 | −31.05 |

| Run 3 | −23.10 | −37.72 | −30.44 |

| Run 4 | −27.12 | −40.27 | −33.87 |

| Average | −23.05 | −37.32 | −31.79 |

FIG. 6.

The photo images of ultrasonic wave transmission directions and their corresponding interactive interface schematic: (a) photo of direction Triangle 1; (b) schematic of equivalent projected interactive interface (parallel vertical lines) for direction Triangle 1; (c) photo of direction Triangle 2; (d) schematic of equivalent projected interactive interface (parallel vertical lines) for direction Triangle 2. In total, direction Triangle 1 would enable ultrasonic wave to encounter 13 equivalent interfaces, which is one more than direction Triangle 2.

Concerning different materials

To investigate the influence of material property on attenuation performance, 1.5 cm-thick through-hole specimens of PDMS (elastic modulus 0.42 MPa, density 1.1 g/cm3) and two types of TPU (density 1.2 g/cm3, yet one harder with modulus around 5 MPa and the other softer with 2 MPa) but of same structural relative density (0.37) were also tested in underwater environment, and attenuation results are listed in Table 5. It is shown in the table that PDMS-printed samples have attenuations at least 50% higher than those in their TPU counterparts. In addition, for the two different types of TPU utilized in specimen fabrication, their attenuations do not show prominent variation.

Table 5.

Attenuations of 1 MHz Ultrasound in Samples with Same Relative Density (0.37), Thickness (1.5 cm) but Different Materials (Polydimethylsiloxane and Thermoplastic Polyurethane)

| Attenuation of samples (dB) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PDMS square | PDMS triangle | Soft TPU square | Soft TPU triangle | Hard TPU square | Hard TPU triangle | |

| Run 1 | −11.52 | −10.66 | −5.96 | −6.97 | −6.97 | −7.59 |

| Run 2 | −11.43 | −11.01 | −7.32 | −6.55 | −7.94 | −6.80 |

| Run 3 | −11.08 | −11.08 | −8.19 | −7.24 | −7.24 | −6.97 |

| Average | −11.34 | −10.92 | −7.16 | −6.92 | −7.38 | −7.12 |

PDMS, polydimethylsiloxane; TPU, thermoplastic polyurethane.

This might be because although moduli in these two materials are different, this difference is not relatively large (86%) when compared with the two cases involving PDMS and TPU, with percent differences of 169% and 131%, respectively. This variation in attenuation performance is likely due to the viscoelastic nature of PDMS, such that its lower stiffness could provide more acoustic energy loss as more structure oscillation or vibration is involved. In addition, the TPU samples of different lattice cell geometry also show similar attenuation, further supporting the prior finding in regard to cavity volume fraction.

Tailoring 3D printed structures for specific attenuations

Basically, one critical advantage in 3D printing is the flexibility of structure forming via additive layer-by-layer built-up manner, which would endow structure design with specific tailoring to meet the needs in various applicational expectations. Based on prior assessment of structures' attenuations in scope of relative density (cavity fraction), impedance mismatch interface interaction, and material selection, several regular patterns of attenuation tuning could be then projected from the perspective of parameter setup in printing technique, which could provide insights into direct tuning of structures' attenuation via facile print parameter control.

First and foremost, since relative density and cavity fraction could effectively influence attenuation performance, it is possible to precisely control filament width through printing process to achieve the targeted range of attenuation. For two 3FC samples with different filament widths (one 501.53 μm and the other, 403.46 μm), the underwater attenuations are 32.32 and 39.61 dB, respectively. This means by reducing filament width by 20%, it is possible to obtain attenuation increase by 26.5%. In addition, considering the filament control such that for each pressure decrement of 5 psi (around 10%) at the chosen print speed of 6 mm/s, filament width would in general reduce by 20%, it is possible to correlate each 5 psi decrement with each 26.5% attenuation enhancement.

Ideally, based on this filament tuning, it is possible to design structures with exceptionally high attenuation enhancement via cavity fraction enlargement. However, it should also be considered that filaments should not be minimized excessively so that structures could still retain support to avoid collapsing. Hence, as a supplement to further enhancing attenuation, it is possible to design structures with geometry that could exhibit more interactive interfaces serving as impedance mismatch layers for ultrasound reflection.

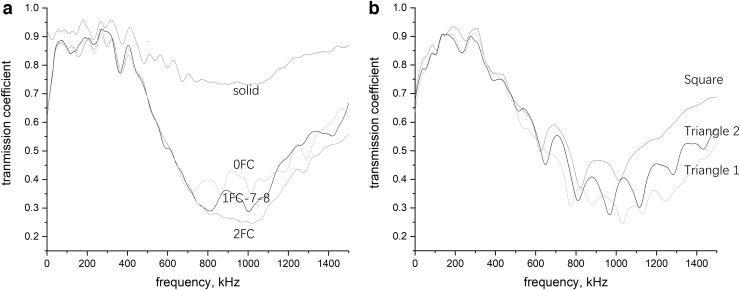

Wave transmission spectrum

For the transmission spectrum at various frequencies as a supplement to prior results, as indicated by Figure 7a, solid PDMS specimen possesses low transmission loss (with minimum transmission of around 75% in frequency domain of 0.75–1.0 MHz), whereas all closed cell air cavity specimens exhibit further reduced wave transmission and the corresponding degrees of reduction are in good agreement with dB attenuation results in the Attenuation Concerning Interstitial Fencing Layer section, with 0FC of lowest transmission loss and 2FC the highest. It should also be noted that in frequency domain of low transmission, 0FC still shows several obvious fluctuations and as number of fencing layers gradually increases from 0 to 2, such fluctuations become diminished and eventually a broadened transmission trough can be formed.

FIG. 7.

(a) The transmission spectrum for PDMS specimens of solid bulk, 0FC, 1FC-7-8, and 2FC. (b) The transmission spectrum for hard TPU specimens, measured with in-plane direction.

This indicates that fencing layer would not only increase peak transmission loss but also facilitate broadband attenuation. Such fencing layer effect can be further supported by transmission spectrum of in-plane measurements for TPU through-hole samples, as depicted in Figure 7b, in which Triangle 1 direction (with most interfaces) shows minimum wave transmission. In the low-frequency region below 0.5 MHz, wave transmissions are generally above 70%. However, since the purpose of this work is focused on the relationship between attenuation and structural design parameters, the general pattern of more transmission reduction via adding interface fencing layer can still be drawn. It is speculated that by adding additional interface layers and reducing lattice size, low transmission can also be achieved in the low frequency region, which could be investigated in the future study.

Conclusions

Air cavity inclusion structures for ultrasonic wave attenuation in underwater environment were 3D printed and their attenuation capacity was characterized. In addition, specific parameters concerning 3D print techniques, such as filament width relationship with print speed and pressure, were also explored. For these structures, interstitial fencing layer, cavity volume fraction, ultrasound transmission direction, and material selection factors would govern ultrasound attenuation. Specifically, interstitial fencing layer, which provides abundant reflection due to impedance mismatch between air and PDMS, could enhance structure's attenuation capacity, such that the specimen with one fencing layer shows attenuation 20% higher than its counterparts.

Furthermore, comparison among specimens with same material, relative density but different lattice cell geometry shows no conspicuous difference in attenuation, when measured in out-of-plane direction. In contrast, considerable influence of geometry on attenuation was found for in-plane direction measurement, in which triangular cell supersedes square cell by at least 10 dB. This attenuation enhancement is attributed to more cell walls (material interfaces) interacting with ultrasonic wave along the in-plane direction. It should also be noticed that concerning two-wave transmission directions for triangular specimen, attenuation differs such that the one with an additional equivalent interaction interface exhibits 20% more attenuation than its counterpart, further corroborating prior conclusion about structure's fencing layer.

Besides, attenuation results of PDMS specimens with different relative density also prove that increased volume fraction of attenuating materials would play a vital role in attenuation enhancement, that is, cavity fraction in closed-cell specimen and material fraction in open-cell specimen. As per material selection for ultrasound-attenuating structures, it is recommended to utilize viscoelastic materials with decent softness and relatively low elastic modulus, as indicated by 50% more attenuation attained by PDMS-based structure than by TPU-based counterpart. Finally, by correlating 3D printing technique's specific pressure parameter adaptation and structure's relative density, a general trend between pressure decrement and attenuation increment could be speculated. Based on all these elements affecting ultrasound attenuation as well as tunability via 3D printing technique, it could be possible to design structures with optimized or specially tailored device for ultrasound attenuation in underwater environment.

Authors' Contributions

J.Z.: Conceptualization, supervision, resources, funding acquisition, writing–reviewing and editing. W.G.: Conceptualization, methodology, investigation, visualization, original draft preparation, writing–reviewing and editing. Y.H. and F.S.: Investigation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

Gratitude and appreciation are given to Jiangnan University for platform of laboratory facilities at School of Mechanical Engineering and funding provision.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Funding Information

This work was supported by Fundamental Research Funds for Central Universities provided by Jiangnan University.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Shankar H, Pagel PS. Potential adverse ultrasound-related biological effects: A critical review. Anesthesiology 2011;115:1109–1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dalecki D, Raeman CH, Child SZ, et al. Intestinal hemorrhage from exposure to pulsed ultrasound. Ultrasound Med Biol 1995;21:1067–1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Stanton MT, Ettarh R, Arango D, et al. Diagnostic ultrasound induces change within numbers of cryptal mitotic and apoptotic cells in small intestine. Life Sci 2001;68:1471–1475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Forney K, Southall BL, Slooten E, et al. Nowhere to go: Noise impact assessments for marine mammal populations with high site fidelity. Endanger Species Res 2017;32:391–413. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Yang Z, Dai H, Chan NH, et al. Acoustic metamaterial panels for sound attenuation in the 50–1000 Hz regime. Appl Phys Lett 2010;96:041906. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zhang H, Xiao Y, Wen J, et al. Ultra-thin smart acoustic metasurface for low-frequency sound insulation. Appl Phys Lett 2016;108:141902. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cox TJ, D'Antonio P.. Acoustic Absorbers and Diffusers: Theory, Design and Application, 3rd Edition. CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fotsing ER, Dubourg A, Ross A, et al. Acoustic properties of periodic micro-structures obtained by additive manufacturing. Appl Acoust 2019;148:322–331. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Vasina M, Monkova K, Monka PP, et al. Study of the sound absorption properties of 3D-printed open-porous ABS material structures. Polymers 2020;12:1062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Aslan R, Turan O. Gypsum-based sound absorber produced by 3D printing technology. Appl Acoust 2020;161:107162. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Waldner C, Hirn U. Ultrasonic liquid penetration measurement in thin sheets—Physical mechanisms and interpretation. Materials 2020;13:2754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Leroy V, Bretagne A, Lanoy M, et al. Band gaps in bubble phononic crystals. AIP Adv 2016;6:121604. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Huang Z, Zhao S, Su M, et al. Bioinspired patterned bubbles for broad and low-frequency acoustic blocking. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2019;12:1757–1764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Leroy V, Strybulevych A, Scanlon M, et al. Transmission of ultrasound through a single layer of bubbles. Eur Phys J E 2009;29:123–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Calvo DC, Thangawng AL, Layman CN, et al. Underwater sound transmission through arrays of disk cavities in a soft elastic medium. J Acoust Soc Am 2015;138:2537–2547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Leroy V, Bretagne A, Fink M, et al. Design and characterization of bubble phononic crystals. Appl Phys Lett 2009;95:171904. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Leroy V, Strybulevych A, Lanoy M, et al. Superabsorption of acoustic waves with bubble metascreens. Phys Rev B 2015;91:020301. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Akiwate DC, Date MD, Venkatesham B, et al. Acoustic properties of additive manufactured narrow tube periodic structures. Appl Acoust 2018;136:123–131. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Liu J, Lan L, Zhou J, et al. Influence of cancellous bone microstructure on ultrasonic attenuation: A theoretical prediction. Biomed Eng Online 2019;18:103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ensminger D, Bond LJ. Ultrasonics: Fundamentals, Technologies, and Applications. CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 21. McClements DJ. Ultrasonic characterisation of emulsions and suspensions. Adv Colloid Interface Sci 1991;37:33–72. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Xia N, Zhao P, Zhao Y, et al. Integrated measurement of ultrasonic parameters for polymeric materials via full spectrum analysis. Polym Test 2018;70:426–433. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Greenspan M, Tschiegg CE. Speed of sound in water by a direct method. J Res Natl Bur Standards 1957;59:249–254. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Engineers Edge. Speed of sound table chart. Available from: https://www.engineersedge.com/physics/speed_of_sound_13241.htm [Last accessed: June 5, 2022].

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.