Abstract

This study is focused on the importance of nanohydroxyapatite (nHA) particle morphology with the same particle size range on the rheological behavior of polycaprolactone (PCL) composite ink with nHA as a promising candidate for additive manufacturing technologies. Two different physiologic-like nHA morphologies, that is, plate and rod shape, with particles size less than 100 nm were used. nHA powders were well characterized and the printing inks were prepared by adding the different ratios of nHA powders to 50% w/v of PCL solution (nHA/PCL: 35/65, 45/55, 55/45, and 65/35 w/w%). Subsequently, the influence of nHA particle morphology and concentration on the printability and rheological properties of composite inks was investigated. HA nanopowder analysis revealed significant differences in their microstructural properties, which affected remarkably the composite ink printability in several ways. For instance, adding up to 65% w/w of plate-like nHA to the PCL solution was possible, while nanorod HA could not be added above 45% w/w. The printed constructs were successfully fabricated using the extrusion-based printing method and had a porous structure with interconnected pores. Total porosity and surface area increased with nHA content due to the improved fiber stability following deposition of material ink. Consequently, degradation rate and bioactivity increased, while compressive properties decreased. While nanorod HA particles had a more significant impact on the mechanical strength than plate-like morphology, the latter showed less crystalline order, which makes them more bioactive than nanorod HA. It is therefore important to note that the nHA microstructure broadly affects the printability of printing ink and should be considered according to the intended biomedical applications.

Keywords: extrusion 3D printing, rheology, nanocomposite, HA morphology, PCL/HA

Introduction

In recent years, bone tissue engineering has taken remarkable strides into developing functional substitutes for the regeneration of large irreparable bone injuries.1,2 An ideal scaffold for hard tissue replacement must account for some criteria, including bioactivity, mechanical stability along with appropriate degradation rate, and optimal porosity (pore size and interconnectivity).3 Thanks to advances in scaffold fabrication technologies, in particular, additive manufacturing (AM) or 3D printing, the possibility to devise a matrix with desired features has grown closer to reality more than ever.4,5 Extrusion-based printing (EBP), as one of the most widely explored AM techniques, revolves around the extrusion of a continuous filament of materials, known as printing ink, to form a three-dimensional structure from orderly deposited layers.5–7

Printing ink refers to a variety of biocompatible and biodegradable materials, including polymers [with natural origin such as collagen and chitosan or synthetic one such as polycaprolactone (PCL) and poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid)], ceramics such as calcium phosphates and bioactive glasses, or their combination as a composite that mimics extracellular matrix.8,9 The aim of producing composite formulations as printing ink is to improve ink features such as processability, printing performance (printability), and bioactivity. Printability is defined as precise and steady deposition of extruded filament to create a stable 3D construct. In principle, such a characteristic is related to rheological behavior of the ink that is influenced by viscosity, which itself is a function of the ratio and intrinsic properties of the used constituents.10,11

PCL/hydroxyapatite (HA) composite is one of the most promising and preferred compounds for application as a hard tissue scaffold.12,13 PCL is a biocompatible and bioresorbable semicrystalline synthetic polymer. While high mechanical stability, flexibility, and excellent combination capability are known as PCL advantages, its high hydrophobicity, lack of bioactivity, and low biodegradability are noticeable as its main weaknesses.14,15 To address these concerns, the use of a secondary ceramic phase is a highly practical approach.16,17

Since HA nanoparticles compose the major structural mineral phase of the natural bone matrix, synthetic HA has gained considerable applications in bone tissue engineering.18,19 This is due to its outstanding physicochemical and biological characteristics, including biocompatibility and osteoconductivity, which are derived from its analogous chemical composition.20,21

As a result, incorporation of HA powder, as a bioactive filler, into PCL matrix, can effectively improve its physiological performance. PCL/HA composite has been extensively used as an ink to be processed in AM method.12,22,23 However, when employed in AM, the maximum amount of ceramic phase in the composite is arbitrarily determined by the rheological behavior of the printing ink and the extrusion of the ink being feasible. In many cases, this limits the range of practical ink composition.12,24 At the same time, higher ceramic load in the composite in many cases is desirable due to overall positive effect of HA in promoting osteoconductivity and bone regeneration. Hence, overcoming such an arbitrary limit in the printing ink composition can be crucial.

Different studies have manifested that some unique characteristics of HA are closely associated with the morphology, size, and crystallinity of ceramic particles.25,26 Hence, to formulate the PCL/HA printing ink, it should be considered that, in addition to polymer concentration and constitute ratio, microstructural properties of HA particles also play an undeniable role in processability of printing ink. Therefore, it is important to associate such characteristics with the rheological features and shear-thinning nature of the preprocessed materials. Many different methods for synthesizing HA crystals with different size and morphologies, including plate like, rod, sphere, and whisker are well described in the literatures.27,28 Among them, nano-HA (nHA), in the shape of plates or rods are similar to HA crystals existing in natural bones.29 Therefore, attention to the synthesis method and relevant intervening parameters, for the tunable synthesis of HA crystals, is important, especially where biomimicry is desired.

The aim of this study was to evaluate the effect of two different physiologic-like nHA (less than 100 nm), plate and rod shape, on the rheological behavior of composite ink and final scaffold structure. For this purpose, nHA powders were first well characterized and the printing inks were prepared by adding the different ratios of nHA powders into the 50% w/v of PCL solution (nHA/PCL: 35/65, 45/55, 55/45, and 65/35 w/w%). The impact of nHA particle morphology and concentration on printing ink viscosity and printed scaffold characteristics, including architecture, mechanical strength, biodegradation, and bioactivity, is evaluated.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Polycaprolactone (PCL, Mw = 60,000 Da) in the form of pellets with average size of 3 mm was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and the 99.8% chloroform (Merck) was used as solvent for PCL. HA with two different morphologies, rod and plate like, in the form of nanopowders (<100 nm particle size) were supplied by APATECH Co. (Pardis Pajouhesh Fanavaran Yazd Co.).

The morphology and particle size, crystallinity, as well as phase purity of nHA powders, were evaluated by the field emission scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEM; Hitachi S4160), transmission electron microscopy (TEM; JEOL 2000FX), and X-ray diffraction method (XRD, 40 kV/40 mA, Cu-K; Siemens-Brucker D5000 diffractometer). The average particle size was assessed by dynamic light scattering (DLS; NANO-flex Particle Sizer, Germany). Also, zeta potential measurement (Zetasizer 3600; Malvern Instrument Ltd., Worchestershire, United Kingdom) and Brunauer–Emmett–Teller/Barrett–Joyner–Halenda (BET/BJH; BELSORP MINI II) method were used to determine the surface charge and specific surface area (SSA)/pore size distribution (PSD) of plate-like and rod HA nanoparticles.

Preparation of the ink

The PCL pellets were dissolved in chloroform solvent at 45°C for an hour to prepare a 50% w/v polymeric viscous solution, which was subsequently applied as the binder phase for the HA nanoparticles in the ink formulation. The predetermined quantities of HA nanopowders with two different morphologies were then added to the PCL solution to make PCL/nHA composite ink with various ceramic contents (PCL/nHA: 65/35, 55/45, 45/55, and 35/65) under continuous stirring.

The inks were constantly stirred in an open environment to adjust the viscosity to an empirically determined viscosity ideal for 3D printing through solvent evaporation.30 Any sublime uneven dispersion of the HA particles would have detrimental impacts on print quality and will cause print termination by clogging the nozzle. Thus, to ensure the homogeneous dispersion of nanopowders in the viscous solution, an ultrasonic bath was also used for 15 min. Isfahan University of Medical Sciences ethic committee issued a IRB waiver for this study.

Rheological analysis

Capillary rheometry was simulated with a single printing extruder fitted with a Universal Testing Machine in the compression mode, to record the applied external pressure (ΔP) (stress) and flow (deformation), which is defined as shear strain. The needle inner diameter (d, 410 μm) and length (L, 6.35 mm) were kept constant. The viscosity (η) of the printing inks was measured according to Equation (1), based on the flow rate (Q) or the weight (m) of material extruded over time (Δt), apparent shear rate (γ), and shear stress (τ).31

| (1) |

Three-dimensional printing of nanocomposite scaffolds

Three-dimensional PCL-HA grid with periodical lattice structure was manufactured using a three-axis EBP platform equipped with a single-screw microextruder (Abtin II; Abtin Teb Co. Iran). The printing geometry, a 2 × 2 cm cubic-shaped block with strut spacing of 500 μm, was designed using Solidworks program (Version 2017; Dassault Systèmes, France) and printed using Repetier software interface. Slic3r slicing profile was used to slice the STL file into G-code. The porous 3D constructs were printed layer-by-layer through the continuous extrusion of the composite ink up to 20 layers.

The printing paste was transferred into a 10 mL metallic syringe. To apply a constant rate to the plunger of the syringe, it was pressed at a constant speed (5 μm/s) to extrude the printing ink through a 22G stainless steel nozzle with internal diameter of 410 μm. This rate was chosen so that the ink is extruded at a line deposition rate of 10 mm/s.

Characterization of scaffolds

Morphology

Structural features, fiber morphology, HA nanoparticle distribution, and pore geometry of the printed scaffolds were evaluated by SEM imaging. The surface of specimens was coated with a thin layer of gold (Au) and examined using SEM (Philips XL30, The Netherlands) operated at an accelerating voltage of 19 kV.

The total pore volume of the 3D printed scaffolds (VP) was calculated according to Equation (2):

| (2) |

Here, VT is defined as the volume of the scaffold and determined using its nominal dimension (cm3), and Ms and are the weight and theoretical density of the composite scaffolds, respectively.

The total porosity (%) is calculated based on the following Equation (3):

| (3) |

Mechanical strength

Uniaxial mechanical test was carried out by a Universal Testing Machine (Walter+Bai AG, Loehningen. Schahausen, Switzerland) in compression mode. Cylindrical specimens (n = 5, D = 5 mm, and H = 10 mm) were compressed to 40% of their initial height at a crosshead rate of 0.5 mm/min. The compressive strength was defined by the maximum stress of the calculated stress–strain diagrams. The values are reported as the mean ± standard deviation.

Degradability evaluation

The degradation rate of the printed constructs was investigated by measuring the weight reduction ratio of the specimens immersed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The scaffolds (n = 3) were first weighed (W0), then soaked into PBS solution, and incubated at 37°C for 1, 2, 4, 6, and 8 weeks. At different time points, the samples were removed, rinsed thoroughly with deionized water, dried at 45°C for 24 h, and weighted (W1) again. Finally, the weight loss percentage was calculated according to Equation (4):

| (4) |

In vitro bioactivity

Evaluation of in vitro bioactivity was performed by immersing the printed nanocomposite scaffolds (n = 3, with equal shape and surface area) in simulated body fluid (SBF) prepared following Kokubo's protocol.32 Samples were soaked in SBF solution and incubated at 37°C for 7, 14, 21, and 28 days. During the incubation period, the solution was refreshed twice a week. At each time point, the scaffolds were taken out from the SBF and washed with deionized water. Finally, the scaffolds were lyophilized and observed using SEM. Energy-dispersive X-ray (EDX) analysis was performed to investigate the elemental distribution and composition of precipitated calcium phosphate (CaP).

Statistical analysis

All quantitative data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Statistical differences were calculated by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey's honestly significant difference test using IBM SPSS Statistic Version 22 and p < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Result and Discussion

Powder characterization

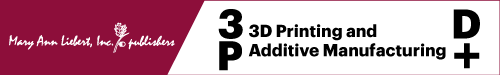

The morphological difference and size of HA nanoparticles were investigated by FE-SEM and the representative images are displayed in Figure 1a and b. As expected, nanoparticles appeared in agglomerated clusters of irregular round shape and bundles of rod forms with a size distribution of less than 100 nm. The nanorod particles show more uniformity in morphology and size. The morphology and structure of nHA clusters were further investigated by TEM observation (Fig. 1c, d). The individual crystallite exhibits a plate-like and rod shape with slight agglomeration and their size was shown to be less than 100 nm.

FIG. 1.

SEM images of (a) plate-like and (b) rod HA nanoparticles. TEM micrograph of (c) plate-like HA and (d) rod shape NPs. HA, hydroxyapatite; SEM, scanning electron microscopy; TEM, transmission electron microscopy.

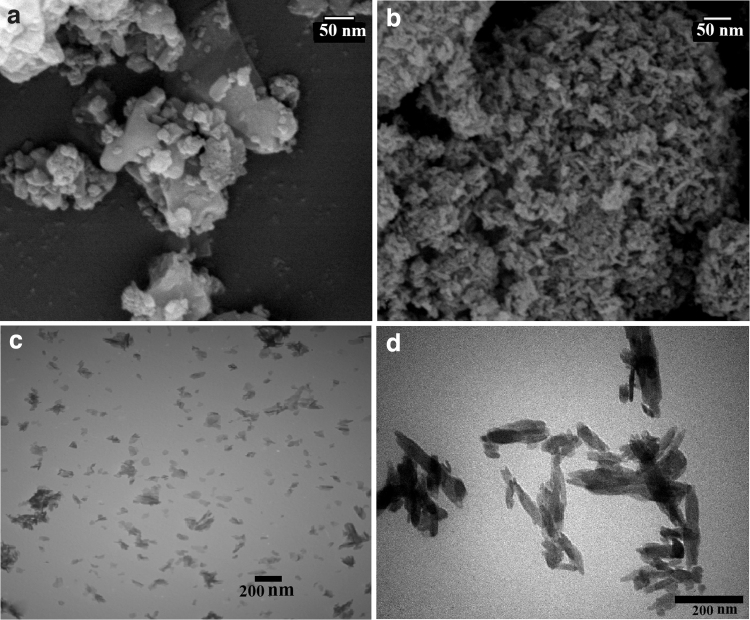

The phase purity and crystallinity of nHA powders were assessed by XRD analysis (Fig. 2). The diffraction pattern of samples demonstrated well crystallized and pure powders (JCPDS#09-0432) without the formation of intermediate or impurity phases. In nanorod morphology, the main growth planes (002 and 211) are in the direction of c axis and are correlated with strong peaks at 2θ = 25.9° and 31.85°. A comparison of the XRD patterns indicates a difference in the intensity of diffraction peaks, which can be assumed as a function of different orientation growth of the HA crystals in two distinct plate-like and rod morphologies. The values of the crystallite size, estimated by Scherrer's equation, were 22.3 nm for plate-like nHA and 31.8 nm for rod nHA.

FIG. 2.

XRD patterns of (a) rod and (b) plate-like HA nanopowders. XRD, X-ray diffraction method.

DLS analysis was performed to measure the hydrodynamic diameter of HA nanoparticles. As summarized in Table 1, the plate-like and rod nanoparticles demonstrated an average diameter of 88 and 185 nm, respectively. The discrepancy in size distribution, especially in nanorod sample, can be related to the agglomeration of nanoparticles. Despite the high dilution of the colloidal suspension, due to the high tendency of nanoparticles to aggregate, erroneous measurement is somehow inevitable. Also, it is noteworthy that measured particle size by DLS is the hydrodynamic diameter and thus is typically greater than the particle's exact size, especially in large asymmetrical agglomerated ones.33 Thus, it can be argued that in this particular case, TEM analysis can be a more accurate representation of the HA particle dimension.

Table 1.

Dynamic Light Scattering, Brunauer–Emmett–Teller Specific Surface Area, Total Pore Volume, Average Pore Diameter, and Zeta Potential of Plate-Like and Rod Hydroxyapatite Nanoparticles

| Sample | DLS, nm | BET specific surface area, m2/g | Total pore volume, cm3/g | Average pore diameter, nm | ζ-Potential, mV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plate like | 88.5 | 24.3502 | 0.020284 | 53.24 | −38.4 |

| Rod | 185 | 52.509 | 0.3303 | 34.113 | −42.5 |

BET, Brunauer–Emmett–Teller; DLS, dynamic light scattering.

The SSA measurement of the HA nanopowders was carried out using BET analysis, and BJH test was conducted to evaluate the PSD. The isotherm data and obtained parameters are displayed in Figure 3a and b and Table 1, respectively. According to IUPAC classification, the N2 adsorption-desorption analysis reveals type IV (a) isotherm and H3 hysteresis loop, which is usually assigned to the mesoporous structure with slip-shaped pores.34 The SSA and total pore volume of rod morphology powder are significantly higher than plate-like HA nanoparticles.

FIG. 3.

Nitrogen adsorption-desorption isotherms of (a) plate-like and (b) rod HA nanopowders. ADS, adsorption, DES, desorption.

These results can be supported by referring to the FE-SEM observations, which reveal a strong tendency of nanorod particles to self-agglomeration that leads to the formation of interparticle porosity and consequently higher SSA. The PSD was calculated by the BJH method from the analysis of the adsorption branch for nHA powders. The plate-like and rod nanoparticles show a broad PSD around 53 and 34 nm, respectively. It is notable that larger diameter particles have a lower SSA and possess less activity.29

Zeta potential is considered the effective surface charge of HA nanoparticles and its resulting electrostatic repulsion force, which alleviates the agglomeration probability of solid particles in polymeric solution and causes more colloidal stability.35 According to the obtained results (Table 1), there was no difference in the surface charge density of the particles. Both samples had a negative zeta potential, 38.3 and 42.3 mV for plate-like and rod morphology nanoparticles, respectively, in water at pH 7.4.

Rheological analysis

A deep understanding of the ink rheological characteristics, including its apparent viscosity and shear thinning behavior, can help maximize the printing efficiency. During the EBP process, biomaterial ink flows through a fine nozzle by applying mechanical force on the ink surface.36 PCL, due to its superior viscoelastic behavior, is applied and manipulated for a wide range of biomedical implants. However, PCL has negligible bone bioactivity and cellular interaction, which can be improved by the incorporation of HA nanoparticles.37

In this study, the concentration of PCL solution was fixed at 50 w/v% and HA nanoparticles with plate-like and rod morphologies were added to the solution with different PCL/HA ratios, including 65/35, 55/45, 45/55, and 35/65 w/v%. The effects of nHA morphology and content on the viscosity of the PCL/nHA blends were studied before the printing process (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

(a) Volumetric flow rate as a function of the applied pressure, (b) shear-thinning behavior, and (c) a general comparison of the viscosity of different composite printing materials.

According to the powder analysis data, two different HA morphologies present distinctive structural properties, which effectively influence the efficient dispersion of filler within the viscous polymeric solutions. Interestingly, in the case of plate-like morphology samples, 3D printing ink with a high percentage of HA could be prepared and printed, while the same EBP system that was used in this study could not process composite ink with nanorod HA content higher than 45 w/v%. Figure 4a indicates the volumetric flow rate of different composite inks as a function of applied pressure. As expected, the flow rate increased with the applied pressure in all experimental groups, although, under the identical pressure, it was decreased as the HA content increased.

According to particle geometry, nanorod HA has a higher aspect ratio than plate-like nanoparticles, which consequently results in its increased effective volume fraction as well as decreased maximum packing density, and finally a reduction in percolation threshold and a drastic increase in the solution viscosity.38 Furthermore, HA incorporation affects the shear thinning flow behavior of printing mixtures, which is required for EBP applications. All composite mixtures displayed shear-thinning flow behavior, which is exhibited by a reduction trend in apparent viscosity in parallel with the increase in shear rate (Fig. 4b). The viscoelastic and shear-thinning behaviors are required features for appropriate process ability and shape fidelity during EBP.

Scaffold characterizations

Three-dimensional nanocomposite morphology

The morphology and microstructure of the printed composite scaffolds were observed by SEM. Figure 5 shows that all composite material inks could create a predesigned interconnected porous structure with approximate rectangular-shaped pores. The distribution of HA nanoparticles within the scaffold substrates can be clearly seen. All printed constructs possessed well-defined filaments structure with an adequate level of shape fidelity and stability.

FIG. 5.

SEM images of composite scaffolds containing different amounts of plate-like and rod nanopowders. Scale bare: (A, a) 1 mm, (B, b) 500 μm, and (C, c) 200 μm. P, plate like; R, rod.

The calculated scaffolds porosity is summarized in Table 2. Filament diameter acts as a function of nHA concentration regardless of its morphology. In fact, the greater content nHA composite formulations indicated a smaller filament diameter and less smooth surface in comparison with the formulations with a lower percentage of nHA. These variations are related to the dispersion of particles and increased surface tension associated with higher concentration of nHA, which results in more filament stability and reduced ink spreading. Therefore, filament stability prevents printed construct collapse, which is accompanied by larger pore size and higher porosity percentages in the final product.

Table 2.

Calculated Porosity of Three-Dimensional Printed Composite Scaffolds.

| Sample | 35% P | 45% P | 55% P | 65% P | 35% R | 45% R |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Porosity, % | 67 ± 1.06 | 71 ± 0.95 | 74 ± 0.78 | 76 ± 0.4 | 70 ± 1.4 | 62 ± 0.57 |

P, plate like; R, rod.

According to previous studies, bone scaffolds with porosity more than 50% and an average pore size in the range of 200–500 μm are desirable for angiogenesis, immigration of osteoblasts, and new bone growth.39,40

Mechanical examinations

The mechanical properties of PCL/nHA composite scaffolds were investigated in a compressive mode. The calculated stress–strain curves are displayed in Figure 6a. All curves show a typical response of highly porous polymeric-based scaffolds with a linear region evident at low strain associated with the initial mechanical resistance, a collapse plateau region with a drop in the slope of the curve, and a rise of stress corresponding to the final densification.

FIG. 6.

Mechanical assessment of 3D printed composite scaffolds. (a) Stress–strain diagram, (b) compressive strength (∼40% strain), (c) and Young's modulus values.

The compressive strength (∼40% strain) and Young's modulus values are showed in Figure 6b and c. There is not a general trend between mechanical strength and nHA percentage or particle morphology. For the same nHA values, nanorod HA particles had a more significant impact on the mechanical strength than plate-like morphology. As it can be seen, samples containing 35% nanorod HA show the highest compressive strength. This result may be attributed to the higher surface contact between the PCL matrix and HA nanorod particles. In comparison with blank PCL, the good alignment of nanorod HA particles and mechanical interlocking across the ceramic-polymer surface can enhance the stress transmission among the HA ceramic phase and elastic polymeric matrix.41,42

Nevertheless, the increase of the HA content results in the attenuation of mechanical properties of printed scaffolds. As mentioned earlier, increasing the amount of nHA in the composite structure was correlated with increasing the porosity and the size of the pores, which are accompanied with reduced mechanical properties. Moreover, high nHA loading decreases the effect of polymeric substrate cohesive forces and makes the brittleness nature of the ceramic phase dominant.

Degradability evaluation

The degradation behavior of 3D nanocomposite scaffolds was monitored for up to 8 weeks to evaluate the weight loss trend of the printed porous structures. The weight changes of all examined samples (Fig. 7) over 8 weeks of incubation in PBS solution reveal a steady weight loss as a function of incubation time. In general, the degradation rate of ceramic-polymer scaffolds depends on the microstructure, porosity, and hydrophilicity of their components.43

FIG. 7.

Weight loss of printed scaffolds during 8 weeks of incubation in PBS. PBS, phosphate-buffered saline.

PCL as a hydrophobic polyester undergoes random hydrolytic cleavage, and as a result, its mechanical stability decreased and gradually the surface area increases, which in return facilitates greater degradation of the scaffold in a self-incremental manner.44 So, as it is observed, scaffolds with high PCL content showed a lower degradation rate. In this experiment, plate-like HA nanoparticles showed less crystalline order, which makes them more reactive than rod-like HA nanoparticles. Furthermore, an increase in nHA content led to higher porosity and consequently higher surface area and diminished mechanical properties, which all result in increased degradation rate.

In vitro bioactivity

The bioactivity of 3D printed composites, which is defined as the ability of nucleation and deposition of CaP minerals on their surface, was evaluated by immersing scaffolds in SBF solution for 7, 14, 21, and 28 days (Fig. 8a). The bioactivity behavior of composite scaffolds based on the PCL and HA is related to the degradation of PCL and dissolution of HA nanoparticles during immersion. At physiological pH, the negative carboxylate ions released following acidic degradation of PCL and negatively charged HA nanoparticles simultaneously absorb Ca2+ ions and accelerate phosphate group accumulation, which triggers CaP mineralization.45 After 7 days of incubation, small and sporadic calcium phosphate crystals were observed on the printed scaffold surfaces.

FIG. 8.

(a) SEM images of surface morphology of printed scaffolds after immersion in SBF for 1, 2, 3, and 4 weeks. Scale bare; 1 week: 10 μm, 2 weeks: 50 μm, 3 weeks: 50 μm, 4 weeks: 200 μm. (b) An EDX spectrum of precipitated HA particles on the surface of scaffolds containing 65% plate-like HA following 4 weeks of incubation in SBF solution. EDX, energy-dispersive X-ray; SBF, simulated body fluid.

By increasing incubation time to 28 days, the amount of CaP deposited on the surface of different scaffold compositions has also increased. Scaffold surface containing 65 w/v% plate-like nHA appears to have more precipitated crystals, which is expected according to the previously described results (see Powder Characterization section). EDX results (Fig. 8b) verified the gradual growth of the apatite layer on the surfaces of the scaffolds following incubation in SBF solution for different time points. Moreover, EDX analysis revealed that after 4 weeks of immersion in SBF, the Ca/P ratios were in accordance with nonstoichiometric biological apatite, which was nearly 1.67.

Conclusion

During printing process of ceramic composite, attention to the morphology and microstructure of inorganic particles, especially in cases where a high content of ceramic will be incorporated in the ink, can be critical.

In this study, HA particles, as one of the most ubiquitous bioceramics, were used to investigate the impact of ceramic particle morphology on general aspect of printing process. While both nHA morphologies had the same particle size, plate-like sample, unlike rod shape structure, enables loading high amount of ceramic phase into polymeric solution/printing ink, which is favorable for bioactivity, biodegradation, and biological performance of the final construct. Although scaffolds containing 35% w/w nanorod HA show the highest compressive strength, increasing the HA composition above 45% w/w for the rod morphology was associated with large agglomerate formation. Thus, nanocomposite printing ink containing 55% or above of the plate-like nHA can be formulated according to the intended biomedical applications.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Funding Information

This work was financially supported by the Isfahan University of Medical Sciences (MUI) through project 198250.

References

- 1. Koons GL, Diba M, Mikos AG. Materials design for bone-tissue engineering. Nat Rev Mater 2020;5:584–603. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Zhu G, Zhang T, Chen M, et al. Bone physiological microenvironment and healing mechanism: Basis for future bone-tissue engineering scaffolds. Bioact Mater 2021;6:4110–4140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Christy PN, Basha SK, Kumari VS, et al. Biopolymeric nanocomposite scaffolds for bone tissue engineering applications–A review. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol 2020;55:101452. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ji K, Wang Y, Wei Q, et al. Application of 3D printing technology in bone tissue engineering. Bio-Des Manuf 2018;1:203–210. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Collins MN, Ren G, Young K, et al. Scaffold fabrication technologies and structure/function properties in bone tissue engineering. Adv Funct Mater 2021;31:2010609. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zhong G, Vaezi M, Liu P, et al. Characterization approach on the extrusion process of bioceramics for the 3D printing of bone tissue engineering scaffolds. Ceram Int 2017;43:13860–13868. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Decante G, Costa JB, Silva-Correia J, et al. Engineering bioinks for 3D bioprinting. Biofabrication 2021;13:032001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ma H, Feng C, Chang J, et al. 3D-printed bioceramic scaffolds: From bone tissue engineering to tumor therapy. Acta Biomater 2018;79:37–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jammalamadaka U, Tappa K. Recent advances in biomaterials for 3D printing and tissue engineering. J Funct Biomater 2018;9:22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Schwab A, Levato R, D'Este M, et al. Printability and shape fidelity of bioinks in 3D bioprinting. Chem Rev 2020;120:11028–11055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Theus AS, Ning L, Hwang B, et al. Bioprintability: Physiomechanical and biological requirements of materials for 3D bioprinting processes. Polymers 2020;12:2262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jiao Z, Luo B, Xiang S, et al. 3D printing of HA/PCL composite tissue engineering scaffolds. Adv Ind Eng Polym Res 2019;2:196–202. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rajzer I. Fabrication of bioactive polycaprolactone/hydroxyapatite scaffolds with final bilayer nano-/micro-fibrous structures for tissue engineering application. J Mater Sci 2014;49:5799–5807. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Huang B, Caetano G, Vyas C, et al. Polymer-ceramic composite scaffolds: The effect of hydroxyapatite and β-tri-calcium phosphate. Materials 2018;11:129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ghorbani F, Ghalandari B, Sahranavard M, et al. Tuning the biomimetic behavior of hybrid scaffolds for bone tissue engineering through surface modifications and drug immobilization. Mater Sci Eng C 2021;130:112434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Singh S, Ramakrishna S, Berto F. 3D Printing of polymer composites: A short review. Mater Des Process Commun 2020;2:e97. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kazemi M, Nazari B, Ai J, et al. Preparation and characterization of highly porous ceramic-based nanocomposite scaffolds with improved mechanical properties using the liquid phase-assisted sintering method. Proc Inst Mech Eng Part L J Mater Des Appl 2019;233:1854–1865. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Shi H, Zhou Z, Li W, et al. Hydroxyapatite based materials for bone tissue engineering: A brief and comprehensive introduction. Crystals 2021;11:149. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kumar A, Kargozar S, Baino F, et al. Additive manufacturing methods for producing hydroxyapatite and hydroxyapatite-based composite scaffolds: A review. Front Mater 2019;6:313. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Han Y, Wei Q, Chang P, et al. Three-dimensional printing of hydroxyapatite composites for biomedical application. Crystals 2021;11:353. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Poursamar S, Orang F, Bonakdar S, et al. Preparation and characterisation of poly vinyl alcohol/hydroxyapatite nanocomposite via in situ synthesis: A potential material as bone tissue engineering scaffolds. Int J Nanomanuf 2010;5:330–334. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Totaro A, Salerno A, Imparato G, et al. PCL–HA microscaffolds for in vitro modular bone tissue engineering. J Tissue Eng Regen Med 2017;11:1865–1875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Murugan S, Parcha SR. Fabrication techniques involved in developing the composite scaffolds PCL/HA nanoparticles for bone tissue engineering applications. J Mater Sci Mater Med 2021;32:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wüst S, Godla ME, Müller R, et al. Tunable hydrogel composite with two-step processing in combination with innovative hardware upgrade for cell-based three-dimensional bioprinting. Acta Biomater 2014;10:630–640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mujahid M, Sarfraz S, Amin S. On the formation of hydroxyapatite nano crystals prepared using cationic surfactant. Mater Res 2015;18:468–472. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ma X, Chen Y, Qian J, et al. Controllable synthesis of spherical hydroxyapatite nanoparticles using inverse microemulsion method. Mater Chem Phys 2016;183:220–229. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lin K, Wu C, Chang J. Advances in synthesis of calcium phosphate crystals with controlled size and shape. Acta Biomater 2014;10:4071–4102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gomes D, Santos A, Neves G, et al. A brief review on hydroxyapatite production and use in biomedicine. Cerâmica 2019;65:282–302. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Molino G, Palmieri MC, Montalbano G, et al. Biomimetic and mesoporous nano-hydroxyapatite for bone tissue application: A short review. Biomed Mater 2020;15:022001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Jakus AE, Rutz AL, Jordan SW, et al. Hyperelastic “bone”: A highly versatile, growth factor–free, osteoregenerative, scalable, and surgically friendly biomaterial. Sci Transl Med 2016;8:358ra127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Trachtenberg JE, Placone JK, Smith BT, et al. Extrusion-based 3D printing of poly (propylene fumarate) scaffolds with hydroxyapatite gradients. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed 2017;28:532–554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kokubo T, Takadama H. How useful is SBF in predicting in vivo bone bioactivity? Biomaterials 2006;27:2907–2915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Maji K, Dasgupta S, Pramanik K, et al. Preparation and evaluation of gelatin-chitosan-nanobioglass 3D porous scaffold for bone tissue engineering. Int J Biomater 2016;2016:9825659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Foroughi F, Hassanzadeh-Tabrizi S, Bigham A. In situ microemulsion synthesis of hydroxyapatite-MgFe2O4 nanocomposite as a magnetic drug delivery system. Mater Sci Eng C 2016;68:774–779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Dizaj SM, Mokhtarpour M, Shekaari H, et al. Hydroxyapatite-gelatin nanocomposite films; production and evaluation of the physicochemical properties. J Adv Chem Pharm Mater 2019;2:111–115. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Cooke ME, Rosenzweig DH. The rheology of direct and suspended extrusion bioprinting. APL Bioeng 2021;5:011502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Zhang W, Ullah I, Shi L, et al. Fabrication and characterization of porous polycaprolactone scaffold via extrusion-based cryogenic 3D printing for tissue engineering. Mater Des 2019;180:107946. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Rueda MM, Auscher M-C, Fulchiron R, et al. Rheology and applications of highly filled polymers: A review of current understanding. Prog Polym Sci 2017;66:22–53. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Chen H, Han Q, Wang C, et al. Porous scaffold design for additive manufacturing in orthopedics: A review. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 2020;8:609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Zaharin HA, Abdul Rani AM, Azam FI, et al. Effect of unit cell type and pore size on porosity and mechanical behavior of additively manufactured Ti6Al4V scaffolds. Materials 2018;11:2402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ahmad M, Wahit MU, Abdul Kadir MR, et al. Mechanical, rheological, and bioactivity properties of ultra high-molecular-weight polyethylene bioactive composites containing polyethylene glycol and hydroxyapatite. ScientificWorldJournal 2012;2012:474851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Dos Santos G, Barbosa A, de Oliveira L, et al. Production of polyhydroxybutyrate and hydroxyapatite (PHB/HA) composites for use as biomaterial. Cerâmica 2017;63:557–561. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Zhang S, Vijayavenkataraman S, Lu WF, et al. A review on the use of computational methods to characterize, design, and optimize tissue engineering scaffolds, with a potential in 3D printing fabrication. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater 2019;107:1329–1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Dwivedi R, Kumar S, Pandey R, et al. Polycaprolactone as biomaterial for bone scaffolds: Review of literature. J Oral Biol Craniofac Res 2020;10:381–388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Naga S, Mahmoud E, El-Maghraby H, et al. Porous scaffolds based on biogenic poly (ɛ-caprolactone)/hydroxyapatite composites: In vivo study. Adv Nat Sci Nanosci Nanotechnol 2018;9:045004. [Google Scholar]